Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: an Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2020

ISSN 1837-5391 | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/mcs

REFEREED PAPER

‘Multi-culti’ vs. ‘another cell phone store’: – Changing ethnic, social, and commercial diversities in Berlin-Neukölln

Anna Steigemann

Technische Universität, Berlin, Germany

Corresponding author: Anna Steigemann, Habitat Unit, Institute for Architecture, Technische Universität, Strasse des 17 Juni 152, 10623 Berlin, Germany. A.Steigemann@tu-berlin.de

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v12i1.6872

Article History: Received 09/11/2019; Revised 09/04/2020; Accepted 09/04/2020 Published 29/06//2020

Citation: Steigemann, A. 2020. ‘Multi-culti’ vs. ‘another cell phone store’: – Changing ethnic, social, and commercial diversities in Berlin-Neukölln . Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: an Interdisciplinary Journal, 12:1, 83-105. http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v12i1.6872

© 2020 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

Based on an extensive ethnography of the economic and social life in Berlin-Neukölln, the paper asks how a changing demographic and social structure affects the social life but also the urban renewal on two iconic but contested streets - ‘the Arab street’ Sonnenallee and adjacent Karl-Marx-Straße. The effects of migration - and particularly of the more recent refugee migration - to Berlin are explored through the reshaping and diversification processes of the physical and social spaces of the two streets and their businesses.

Keywords

Migration, businesses, shopping, diversity, community, belonging

Introduction: social and commercial diversification through migration

Walking down Karl-Marx-Straße in the Neukölln district of Berlin, every passerby is immediately thrown right into the middle of the vibrant street life. At the busy crossing of Rathaus Neukölln, one can see shoppers, residents, local employees, and commuters on their way to work or nearby schools squeezing out of the subway exits. The sidewalks are heavily crowded with what appears as a highly diverse crowd of people. At second sight, one might also notice that the liveliest and most diverse sidewalks host a variety of smaller and medium-sized , individually and franchise owned stores of many kinds: bakeries, flower stores, hair and nail salons, grocery stores, butchers, several Turkish, Lebanese, Syrian, Palestinian and Vietnamese food takeaways, diners and restaurants, cafés, textile and shoe stores, cell phone stores, as well as chain stores, bank branches, and supermarkets. Taking a third look, one might discover that many passersby greet, wave, and nod to people inside of the stores, waving their hands through the stores’ front windows, while others focus more on the products in the displays rushing by the stores. A look through the stores’ front windows into the salesrooms and gastronomic spaces presents an even more nuanced picture of not only who uses the street and its public and semi-public spaces, but also in what ways and for what purposes: supply and social exchange.

With this short observation of Karl-Marx-Straße’s sidewalk life, I’d like to introduce you to the economic and social life of Sonnenallee and Karl-Marx-Straße in Berlin-Neukölln, giving first hints of the high social, ethnic, cultural and commercial diversity. Main thoroughfares and commercial streets are more than just places for provision and consumption. Streets like Neukölln’s Sonnenallee and Karl-Marx-Straße often also represent the key spaces for identification with and perception of a neighborhood. They are the places where rather abstract concepts, such as globalization, migration and diversity, take a concrete and local form. Such shopping streets are also places of important everyday encounter, where the practice of shopping allows strangers to meet and face one another in (often) routine, familiar, and thus safe environments (Shamsuddin & Ujang 2008; Steigemann 2017).

In this context, this paper thus addresses local store owners’ and urban renewal actors1’ framing and perception of ethnic diversity in Berlin-Neukölln – as an inquiry of everyday social life and the often neglected, ordinary, and diverse places where socio-economically, ethnically, and demographically diverse urban dwellers come in contact with each other. Following Sharon Zukin’s idea of urban cultural ecosystems as ‘shared cultural networks and relationships that facilitate cultural, social and economic interaction between members of a group’, I consider this local social life as being

formed by ordinary city dwellers interacting in vernacular spaces […] Today, they are often public spaces where men and women engage in social practices of prolonged and habitual consumption: the ‘‘third space’ of local pubs, cafés, and barber shops (Duneier, 1992; Oldenburg 1989), and the casual ‘‘sidewalk ballet’ of local merchants, shoppers, and passers-by (Jacobs, 1961) Zukin (2012, p.2).

In line with Sharon Zukin, and based on my dissertation work from 2012 to 2016 about the social ‘more’ that store owners and their businesses contribute to neighborhood social life, this paper argues that everyday street-life on ordinary shopping streets, their markets, cafés, and stores, is the mainspring of a shared public social life. They are the key urban spaces where highly diverse strangers mingle and meet, assuming that this local level of everyday social practices produces ‘more’ than just exchanging money for goods or services – it fosters processes of socialization, negotiation, and eventual mutual understanding (cf. Amin & Graham 1997; Amin 2010; Steigemann 2017, 2018). However, this paper extends the previous work on the social life to questions of diversity and criticality of the spaces where both unacquainted and acquainted urban dwellers interact with each other. The retail and gastronomic businesses located on Sonnenallee and adjacent Karl-Marx-Straße as the places where community is practiced become all the more important in the 21st century, where migration is the defining norm and where increasingly more people are on the move (forcibly or voluntarily) and constantly generate and affect contemporary and future urban diversities. Hence, this paper pays attention to how shopping streets are affected by migration, diversity, urban ‘multi-culture’, and urban regeneration, while contributing to neighborhood social life and new diversities practiced through the micro-interactions in the diverse local businesses, which thereby often also include the more recent newcomers. In a second step, I argue that regardless of the place- and community-making of the local store owners and their employees, the local urban renewal and regeneration actors have a very different understanding of these spaces and that their operators aim for a different kind of ‘diversity’. They often frame and depict the increasingly ethnically diverse businesses on the two streets in the course of urban renewal in ways that threaten the livelihood of many of the existing businesses. The paper concludes by contrasting the two sets of actors’ perceptions and concrete practices on the two streets that make the place and its diversity, as indicated by the quotes in the title of the paper, the ‘multi-culti’ of store owner contrasted with the repeated derogatory statements of urban planners about the migrant-owned ‘cell phone stores’.

Ordinary streets matter: Conceptual thoughts and methodological approach for the study of Sonnenallee’s and Karl-Marx-Straße’s diverse social life

The two streets have been selected as case study sites, because they have experienced drastic changes due to global and local economic development, increased mobility, globalization, migration, and different phases of urban renewal in the past. These processes have fundamentally altered the basis for social interaction there, not only because they have affected the local cultural and ethnic diversity, but also generated heightened disparities in income, education, and training (e.g. Häußermann & Siebel 1987; Dangschat & Fasenfest 1995). As a result, (not only) for the people working and living in the area, the experience of ethnic or lifestyle diversity has become an everyday phenomenon – just as the coming question of the 21st century is generally about ‘the capacity to live with difference’ (Hall 1993, p. 361).

Sonnenallee and Karl-Marx-Straße in northern Neukölln are two of Berlin’s more socio-economically, ethnically, and architecturally diverse and in that regard ‘ordinary’ 21st century shopping streets2. Suzanne Hall (2012, 2015a) claims that scholars of ethnic diversity, belonging, and home-making in diverse metropoles often overlook the importance of routine practices of forms of difference. Following her, my exploratory research revealed that the two streets’ businesses can act as sites for the practice of local community and inclusion, but my further research revealed that they also reflect the ways in which larger socio-spatial changes such as migration and urban regeneration are reorganizing the ways that commercial activities influence neighborhood residential and social patterns. However, so far, only a small number of scholars have considered the wide range of functions these spaces and their employees serve in their respective neighborhoods, for example providing local services and employment, and more indirectly, social well-being (cf. Everts 2010, 2015; Hillmann 2011, 2018).

In the following, I thus look closely at the patterns of how people who live or work or shop in Neukölln run (intentionally or not) into each other in local businesses and how the respective merchants’ social practices shape these interactions (deliberate or not). In other words, I explore the consequences of social interaction during consumption. While the dissertation research from 2012 to 2016 revealed that shopping is not just an interaction between customers and staff, but also generates social externalities that have important consequences for neighborhood life, such as offering a place where community3 can be practiced (for more details see Steigemann 2017, 2018). In this paper, I further argue that within the city as an interactional context for community, Karl-Marx-Straße and Sonnenallee are two important contact zones, in as much as their businesses are the concrete contact spaces for face-to-face interaction that enacts some kind of community – both for the long-standing users but also for newcomers. In other words, much of the face-to-face interaction that builds community in the course of routine life takes place in the most used and frequented local spaces and places, namely the local shopping streets and their amenities. This means that the new urban mixes might generate more social and spatial exclusion and fragmentation on the one hand but shops and shopping/consumption in diverse districts still hold the potential to bring diverse people in the context of everyday routines.

As a truly diverse district and streets, Neukölln, Karl-Marx-Straße and Sonnenallee also become urban sites that work as ‘a magnet attracting further immigration, further diversity and difference, for creative classes and creative milieus’ (Mayer 2012). This is also why these two streets were selected for the study of diversity and its commodifications in the context of urban renewal. Their local ‘diverse’ character, through its local people and businesses, also has become an asset for promoting not only single blocks or streets, but the entire neighborhood (northern Neukölln) and city (Berlin) in the competition for investment, tourists, and so-called human capital:

Diversity has become the new orthodoxy of city planning. The term has several meanings: a varied physical design, mixes of uses, an expanded public realm, and multiple social groupings exercising their ‘right to the city’ (Fainstein 2005, p. 3).

Hence, with its long-term diversities but also more recent increased (refugee) migration and new attention from investors and policy-makers to this diverse urban landscape with its distinct local character, the two streets represent a fruitful site to study the social and spatial changes resulting from an increasingly diverse local social and economic life. The question remains, in which concrete spaces do socially and ethnically diverse people interact with strangers or partial acquaintances and why? And what are the social and spatial changes resulting from these encounters and interactions? And if businesses represent the places that bring diverse people together, how do local shopkeepers supply and deal with an increasingly diverse and dynamically changing customer base?

Sonnenallee and Karl-Marx-Straße in Berlin-Neukölln

On the basis of ethnographic fieldwork of the dissertation project and ongoing postdoctoral research on what I call urban arrival infrastructures, conducted between November 2012 and March 2018, I argue that even in their most superficial and ephemeral form, physical and verbal interactions in local businesses form a crucial ingredient in the development of community and a sense of belonging for some customers and staff, and particularly those, who spend most time in the neighborhood. With this, I consider in-business social interactions as building the smallest block of any type of community, as the social component, whereas the businesses themselves represent a significant micro-sociological community place – the spatial component of community (the buildings) on Sonnenallee and Karl-Marx-Straße.

More precisely, I focus on local economies, shopping patterns and urban migration and diversity, and through a theoretical sampling procedure, I selected the two streets and the 20 concrete business spaces where ethnically, demographically, and socially diverse customers and staff intermingle (Glaser & Strauss 1967). As mentioned, until today, very little has been written on interactions between differently stratified urban dwellers in the (semi-) public spaces of businesses. While the existing literature mostly focuses on the mapping of so-called ethnic or migrant-owned businesses, almost nothing has been said about the social and cultural dynamics and contributions of multi-ethnic neighborhoods, shopping streets, businesses, and their ‘remarkable, yet often invisible and unrecognized contributions to urban cultures and economies’ (Kuppinger 2014, p. 141). This literature also does not focus on their social life and the management and negotiation of the arrival of newcomers on a more specific level. The studied businesses on Sonnenallee and Karl-Marx-Straße operated by owners with a so-called migration background are thus not defined as ‘ethnic businesses’. Rather, working with a praxeological approach (Reckwitz 2002, 2016; Schatzki 1996, 2001; Shove and Trentmann 2018), focusing on the social and spatial practices of business people and customers and urban renewal actors I do not differentiate the business sample with an ethnic lens. Ethnizing business ownership and operations is also misleading because the owners’ and staff’s entanglement with family and community networks is no different from their ‘ethnic German’ counterparts. In addition, I avoid the term ethnic/migrant entrepreneur/business, since with the exception of the urban renewal program actors, none of the interview partners described themselves, or their own and anyone else’s businesses in that way, even though many of the newer Arabic speaking businesses on Sonnenallee consider themselves as ‘typical for Arabic countries’, as one owner said. So-called ethnic entrepreneurship is rooted in a structural context or state regulatory regime, as well as in resources and support mechanisms derived from the entrepreneur’s social networks, which, at least in this case, are not ethnically specific, but rather mediated by class relations. In the vein of Kloostermann et al. (1999) and Yildiz (2017, 114), who consider migrant owned businesses as in a ‘mixed embeddedness’, I also rail against the reduction of ‘immigrant entrepreneurship to an ethnic phenomenon within an economic and institutional vacuum’. Just as all business people do, immigrant entrepreneurs rely on social networks and draw on family support if needed, particularly in situations of heightened capitalistic competition or other economic issues.

The business sample for this paper includes small, individually owned and ‘ordinary’ (Hall 2012) businesses, most often offering services and products of everyday supply and accommodating ‘minute cross cultural encounters which are crucial for the creation of inclusive urban cultures’ (Kuppinger 2014, p 141) as in contrast to their more expensive, lifestyle-oriented, and branded chain store counterparts. For Sonnenallee, a first inventory was made between March and August 2017 as a reference point for any further commercial changes, since simultaneous gentrification and migration processes were evident from 2016. From this inventory, 20 businesses were ethnographically explored, most of which had owners from Lebanon, Turkey and Syria. While most store owners on Sonnenallee are ethnic Germans and first-generation migrants from Lebanon and the Palestinian regions and increasingly from Syria, Karl-Marx-Straße’s business owners are ethnically more diverse and operated by first, second and third generation migrants from mostly Turkey and the European Union. Business inventories for Karl-Marx-Straße were made in 2012 and early 2017 to track and map changes. In contrast to the Neukölln’s first-generation of business-owners, who often import and sell so-called ethnic products (particularly foodstuffs, religious goods and clothing) for an immigrant market and fill not only a commercial niche but also the previously vacant business spaces along the two streets, particularly on Sonnenallee, these second (and third) generation immigrant owners have a keen understanding of their surrounding socio-spatial environment, the respective residential and customer composition, and the neighborhood’s consumption dynamics (cf. Hillmann 2018). On Sonnenallee, more products and services are sold that staff and ‘customers know from their homes’, as one bakery owner puts it, whereas Karl-Marx-Straße’s offerings are much more diverse, in the sense that shopkeepers expand their offers and services to the biggest possible population group and thus serve a multi-ethnic and highly diverse clientele, including tourists. I worked with a multi-method and highly ethnographic approach, involving in-depth interviews with owners, more conversational interviews with customers and staff, participant observation in selected businesses and interviews with employees of the ongoing local urban development programs – on top of the more quantitative inventories of the two streets to reveal commercial changes. I also analyzed secondary information, such as media coverage and development programs. This mix of methods attempts to generate a more attentive, dynamic, and reflexive practice that privileges the interviewees’ and other co-present participants’ voices and social practices, rather than my preconceptions of the local diversities, social life, and urban regeneration.

Retail or ‘political’ challenges for migrant owned businesses?

In general, retail and trade are constantly undergoing structural changes as a result of intensified competition as well as demographic and socio-cultural changes. In the 20th century, individually-owned specialty stores, such as those offering groceries, clothing, shoes, repair services and other daily goods prevailed on Sonnenallee and Karl-Marx-Straße, making the latter a particularly attractive shopping location for West Berlin’s southern and eastern districts. As commercial locations, both streets have changed significantly after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. While Sonnenallee was cut into two parts by the Berlin Wall and then unified as a major automobile thoroughfare and re-connected to the revived S-Bahn traffic, Karl-Marx-Straße initially received more shoppers from the East, but then saw a significant downturn in the mid-1990s. This was caused by unemployment due to the loss of industrial jobs, the out-migration of the employed working-class and middle-class families, and competition from nearby new shopping malls both in the eastern and western parts of Berlin (Hangebruch & Krüger 2014). This loss of potential and regular customers challenged many longstanding businesses, many of which had to close down. The independently owned specialized retailers in particular faced significant closures. Until the mid-2000s, the new businesses that opened in their place on Karl-Marx-Straße were predominantly franchise and chain stores as well as discount shops. Sonnenallee still struggles from high vacancy rates and low purchase power and, on the southern strip, a lack of walk-in customers (Hüge 2010, pp.23 ff.; Steigemann 2019).

The local district authorities designed several urban renewal programs to tackle the two streets’ decline since the early 2000s. The programs, which focus mostly on physical improvements, aimed to reverse the buildings’ and sidewalks’ dilapidation as well as improve the negative reputation of the whole district as a place of vandalism, decay, and crime. The streets’ situation in the late 1990s and early 2000s was often framed as a ‘not economically and consumption friendly atmosphere. It should surprise nobody, if one or the other internally departs from Neukölln’ (Engeln 2001 in Hüge 2010, p. 42). In public reports and policy papers, as well as local media, Sonnenallee in particular, is often depicted in an even more deprived and negative way than Karl-Marx-Straße, often with a racist tone in regard to the longer-standing cluster of businesses operated by people from Arabic countries – as ‘Gaza strip’ ‘Little Beirut’, a place controlled by ‘the Arabic Mafia’ until very recently4. The interviewed owners also criticized the decline of the formerly thriving Karl-Marx-Straße and Sonnenallee and were scared that they would have to move their businesses to another district because of the negative media depiction and low purchase power. An interviewed butcher who owns one of the businesses that barely managed to survive this low point, describes the neighborhood situation in the mid-2000s in the following way:

[T]he bottom point of the development in Neukölln was in 2004, 20055, when it really was on the rocks, because too many regular customers died out or moved away, [they] were scared of the other nationalities or were worrying and said no, I won’t send my kid to a kindergarten or in a school where 90% of the school mates have foreign roots […]. Also, the negative media coverage, many just moved then and said, no we need to move to better city districts […], we can’t stand this anymore, this is too noisy, this is too dirty, this is too too too foreign […]

So particularly in Neukölln, you realize immediately social cuts, … because many people that live here are affected by it. This is still a working-class district, the people who live here work in simple activities, are low wage workers, and they kept their savings back and that just made life for us difficult […] but starting with 2006 it [sales] surged. 2005, we really hit rock-bottom, that was the very first time that I had to dismiss two employees because of a lack of revenues.

Other store owners on Sonnenallee and international media describe the past in a similar manner:

There used to be another key service shop a bit down the street. There was also a shoe repair shop. He’s gone as well. So, these crafts and manufacturing services, they disappeared more and more (Jeweler).

Not long ago, even the gentrifying parts of Neukölln were too gritty for most tourists, but these days, even less adventuresome travelers will be charmed by the ships and cafés popping up along [Sonnenallee and its side] streets (New York Times 2013).

Many other interviewees similarly described late 2005 and 2006 as a bad period for the area and a time they seriously considered leaving the neighborhood. Some of the owners of Turkish and German descent also blamed the growing presence of businesses owned by people from ‘Arabic countries’ for the decreasing sales and as new competitors. As one owner puts it, ‘Sonnenallee is shitty. Back when only the Germans and Turkish were influencing the street’s image, everything was better.’ However, the longer-standing owners obviously stayed, either hoping for better times, or because they felt rooted in their community, or simply due to lack of resources. Other named problems that the streets faced were the closure of local major warehouses, a terrible traffic situation, high vacancy rates, and a lack of parking, or as Sonnenallee’s owners still describe for today’s street: ‘...very unorganized, especially while walking on the sidewalks’, ‘...chaotic atmosphere. It is very lively, people are talking loud in the street’ but ‘I have to worry about my kids, worry about my car’. The local officials also described the sidewalks as unwalkable, narrow, and overfilled with merchandise and signage from stores looking to drum up business. This downturn, with increased unemployment, poverty, and vacancy rates continued until the late-2000s (cf. Hüge 2010, p. 38).

Yet, present everyday life on the two streets has been affected not only by past migration and the current comparatively rapid migration mostly from Syria, wider demographic changes and urban renewal, but also by shifting global and local investment strategies and changing shopping patterns. Just as with many inner-city shopping streets, both streets are also affected by a decline in economic activity due to disinvestment and the low local purchasing power, after middle and higher income residents moved out of these neighborhoods before the mid-2000s (Häußermann 2011, p. 274, Häußermann & Kapphan 2002; Hillmann et al. 2017). Furthermore, the urban renewal program along with new and higher competition, rising commercial rents, shifting consumer preferences and shopping behaviors, affected the decline of many of the longer-standing ‘traditional’ and small-scale specialty stores and attracted more chain stores and discounters particularly to Karl-Marx-Straße. In this context, the interviewed business people named rising commercial rents, demographic changes and the respectively shopping preferences, the local shopping mall, and chain stores as well as the far-reaching construction sites as their main business threats. By contrast, the local officials stated shifting consumer preferences and increase in sales spaces along with the unwillingness to upgrade their businesses as the main reasons for the smaller businesses’ struggle. Put together, today, many of the longer-standing individually owned businesses on Sonnenallee and Karl-Marx-Straße were challenged by the loss of their customers due to the disinvestment of the past years and the subsequent out-migration of many previous customers. Since the mid-2000s, they now have to cope with the recent re-investment, shifting demographics, new corporate competitors and rising commercial rents, particularly because of increased gentrification .While these structural changes put an additional burden on many of the longer-standing businesses, other – often the newer – store owners and particularly those that cater to the area’s new demographics welcome the changes while being aware of the increased competition and often blaming specific ethnic groups for these processes, as underlined by the following owners’ quotes:

[there will] be more restaurants and it will be more popular. What I would like to see is something different. Something other than markets and restaurants.

So, my customers increasingly come from the whole world...and increasingly, there are more young people living in this building. There’s one, she comes from Iceland and others they come from all over Europe.

60% of the customers are German. Others are now mixed: Arabic, including Syrian or other countries. Every day it’s busy now.

I believe it will change a lot. It is gonna have more cafés. Pannierstraße is not so gentrified, but Sonnenallee will be like Kreuzberg, full of English people and Australians.

Urban renewal affecting the business owners’ agency

Despite the local ethnic diversities and the current growing of a cluster of Arabic speaking businesses on Sonnenallee, the urban renewal agencies also ‘look for a different ethnic mix’ (urban planner) in terms of the area’s businesses. Hence, in order to survive economically with these changes and the ongoing urban renewal of northern Neukölln, owners try to keep up with the renewal agents’ demanded ‘experience-oriented’ shopping spaces for customers who pursue shopping as a leisure activity6. One would imagine that events such as street festivals would be valuable for boosting local business; however, the interviewed retailers abstain from participating because they either disagree with the format of these events, and with the overall measures taken by the city to improve the street’s ‘shopping experience,’ or they do not know at all about planned events or a potential participation. The interviews revealed that this is firstly, because many of these comparatively bigger and ‘official’ events are aimed at target groups incongruous with the existing businesses’ own clientele, e.g., late night shopping events or cultural events such as 48h Neukölln or Nacht und Nebel Neukölln [Night and Fog Festival] that draw primarily younger, lifestyle-oriented visitors, and tourists that look for entertainment and arts rather than supplying themselves with everyday goods during these events. Secondly, the urban renewal agents don’t approach all business owners. Thirdly, participating in the beautification and event measures, and other more experience-oriented shopping events are often too costly for owners of small businesses:

[For the late-night-shopping,] they ask us to keep [the store] open for a longer time. Firstly, nobody asked me in advance if I’m able to do this, no artist would come to us anyway, so why should I keep the business open? Because the people won’t burden themselves with carrying a flower bouquet through the streets at 10 pm […]. [The planners] are not paying attention the small businesses […] We can’t afford to pay 500 or 1500 or 5000 Euro for such a weird light installation (flower store owner).

Most other businesspeople agree with the flower store owner, preferring to rely on their own experience and knowledge and exclusive relationships with regular customers, repeating measures that have previously proven successful. For instance, the flower store owner threw a backyard party, to which the owner also invited the local officials, neighboring business colleagues, and interested customers. It seems that it is these conflicting motives and agendas of owners and urban renewal agents that result in a situation where the urban renewal programs challenge rather than support those businesses that made the place and character of Karl-Marx-Straße and Sonnenallee:

Some details about the development plans of the district provide a context. In 1999, the Berlin Senate Administration for Urban Development and Neukölln’s district authorities began implementing different urban renewal schemes (including the Neighborhood Management programs in several Kieze (neighborhoods) across Sonnenallee and Karl-Marx-Straße. Local, federal, and national authorities further implemented programs responding to the area’s physical decay; two of the most notable are Urban Restructuring West and the implementation of Rehabilitation Zones aimed at the consolidation of the urban socio-spatial structures7. In 2011, Karl-Marx-Straße along with Sonnenallee, both running in a southeast direction from Hermannplatz, have been designated as one such rehabilitation zone. In addition, the senate administration along with the district administrations also implemented a so-called Active Centers Program in order to grow urban centers (aka shopping streets and zones) into an ‘attractive economic city or district centers’ in 2008. One part of this program are the local City Management teams, who are in charge of the area’s redesign and the development of the Active Centers’ commercial structures. Karl-Marx-Straße’s particular program is called Aktion! Karl-Marx-Straße (Aktion KMS) and is in charge of the street’s economic and commercial development. Sonnenallee is not part of this program, partly because of its lower number of businesses. The urban planners work closely with the urban renewal commissioner and planning departments responsible for organizing the local rehabilitation zone and other urban restructuring programs (Huning &Schuster 2015, pp. 744 ff; Steigemann 2018).

Hence, following decades of what the planners frame as decline and with the onset of these programs, the district of Neukölln suddenly ‘became an option for young starter households and middle-income groups who could no longer afford to live in areas such as Kreuzberg, Mitte, and Prenzlauer Berg, where rents had already been rising from a much higher level’ (Huning & Schuster 2015, p. 745). In 2012, the physical renovations began on Karl-Marx-Straße: they began at the southeastern end and will continue to the northwest in the direction of Hermannplatz; the final reconstruction phase is scheduled to beginning in 2020. Right in the middle of the planned reconstruction zone, urban planners began, simultaneously in 2012, to redesign the Alfred-Scholz-Platz. The staff of these programs work under a shared motto that summarizes their vision of Karl-Marx-Straße: ‘Young, colorful, successful – trade, encounter, experience (Jung, bunt, erfolgreich –handeln, begegnen, erleben).’ It remains unclear what ‘colors’ this ‘colorful’ attribute for the street’s future encompasses. This motto indicates a vision that is clearly designed towards different demographics and businesses than its current commercial and residential diversity. In addition, and despite their different foci, measures, budgets, and target groups, all planners and municipal employees share this common vision and goal to ‘upgrade’ (urban planner) the street8.

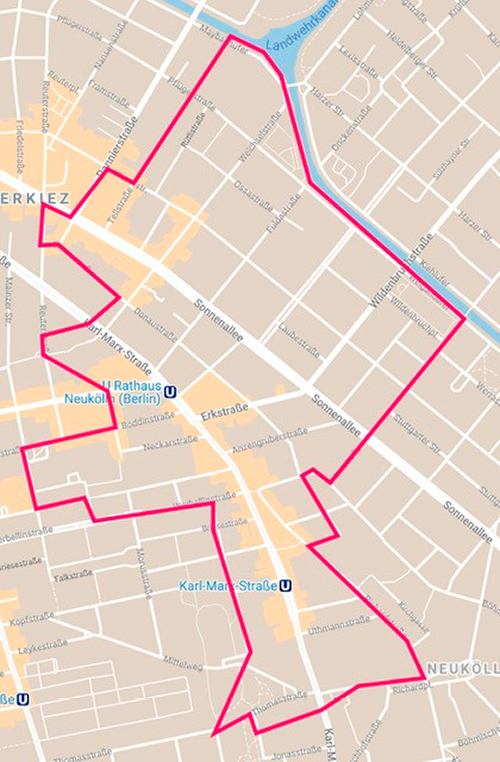

Urban Renewal Program area around Karl-Marx-Straße and Sonnenallee, separated by Donaustraße

These conflicting versions of improvements and future development of the streets can also be discussed through the genealogy of the urban renewal programs. In the late 2000s, in the exploratory analysis for the urban renewal program Active Urban Centers9 (Aktive Stadtzentren), the authors argue that the street suffers primarily from heightened competition with nearby shopping locations and from a negative retail development characterized by high vacancy rates, low residential purchasing power, a disproportionate presence of discount stores, and a lack of so-called anchor businesses, upscale gastronomic facilities and independently owned businesses. This negative view from above, neglecting ideas for the street from below, i.e. the business people and customers’ perception of the streets ‘from below’, affects the vision’s inherent logic of upgrading the commercial structure and the physical design of the area. Simultaneously, in this document, the planners also celebrate northern Neukölln’s ethnic diversity and its ‘success as both a place of trade and residence’. However, for most of the program, they predict a further downturn and bemoan the population’s low social status and the lack of acceptance and interaction between the local ethnic Germans and migrants. Finally, the planners conclude that in spite of the first signs of (apparently welcomed) gentrification, the area still suffers from a negative image and a lack of networking among the business owners and landlords (see renewal area on the map).

With these concerns in mind, the planners developed their concepts and plans for the street’s upgrading, which began in 2008 and continues until today10. The renewal project’s head planner confirmed that the program’s plans may present certain ‘challenges’ for many of the smaller businesses, but firmly rejects the idea that their measures also threat them: ‘This is the free market. We set only the political framework’. This can be interpreted as avoiding any responsibility for the rising rents or struggles the businesses face, due to the reconstruction shaping the street towards purely economic values. In 2011, the Berlin government and the Senate extended the funding phase by fifteen additional years. To date, the Active City Center with its Aktion KMS is the current main urban renewal program for Karl-Marx-Straße, while Sonnenallee has experienced, including t very recently in 2020 more media and political attention but no physical measures yet. In general, the Active City Center program focuses on ‘improving’ the street’s public space (such as the aforementioned Alfred-Scholz-Platz) and to ‘beautify and extend’ the local sidewalks and places. Further, the project hopes to improve the commercial offers, the traffic situation, and in particular, the cooperation with house owners and selected business people11.

Since 200612, Karl-Marx-Straße, but even more so Sonnenallee and their adjacent areas to the north have caught the attention of comparatively young entrepreneurs, who have opened their first businesses there, most often bars, cafés and other gastronomic spots. This has set in motion new waves of investment and media coverage, which in turn steered ever more residents to move to the area and even more new businesses to take root in the area. As a result of this influx, the area has seen a rise in commercial and residential rents. The media coverage along with the district’s self-promotion attracted further investment, residents and business people as well as tourists.

For instance, the local administration’s magazine for the renewal area around Karl-Marx-Straße, called Broadway Neukölln, reports and advertises mostly the new businesses, galleries, and arts events. In an interview with the future district mayor Franziska Giffey (2015), both the mayor as well as the journalist argue in this vein that the current construction sites are necessary to develop Karl-Marx-Straße into a new ‘Broadway’: ‘Karl-Marx-Straße should become Neukölln’s Broadway, more space for pedestrians and bikers will be created’. In addition, the mayor, showing the high number of interested journalists around Karl-Marx-Straße, only visited the back then new businesses, such as the café pavilion (opened 2014) on the central and new designed plaza of Alfred-Scholz-Platz13. However, in contrast to the six kilometer long Karl-Marx-Straße, New York City’s Broadway runs 25 km long from the South of Manhattan up to the Bronx (and then an additional 29 km beyond the city borders) and targets mainly tourists and other city visitors with its main shopping parts hosting almost exclusively big chain stores. This (incongruent) comparison of Karl-Marx-Straße with Broadway reveals the exaggerated and unrealistic expectations of the journalists and their vision.

As the district’s urban planner and the urban renewal commissioner argue:

Well, I consider the current store owners as those actors that are now here and occupy this space right now. But we plan strongly focused on the future, to around 15 years from now and we develop the coulisse or a space for activities. We explicitly don’t serve the local actors but we have a development vision.

The development task is to generate a new vision of a space that takes over totally different functions [than now] and now […] we become aware […] which measures will be implemented and within a circle of indeed planners and experts […] trading, experiencing, encountering, this means something different than in the past, where the street primarily had a shopping focus.

Well, we want distinct commercial structures or we want them to change […] what we want is to change something in the sectoral mix, if we can, but this doesn’t work via the traders but this works first of all via the land owner.

In the framing of their jobs and the programs’ working goals, the two urban renewal agents underline their support for the increase in wealthier residents and new - more lifestyle and differently ethnically connotated – businesses. They also make clear that their vision of the future streets may have to be developed without the cooperation of the current retailers. It seems that for them, it is up to landowners and landlords to have priority over ‘community’ through the rents and leasing practices. However, surrounded by talk of gentrification and an increase in anti-gentrification events, only a few commercial establishments considered to be typical markers for gentrification have actually opened a shop on Karl-Marx-Straße, while there are increasingly more upscale businesses opening up on Sonnenallee. Among them are a few cafés and upscale restaurants and bars, galleries and two organic supermarkets but no retailers yet (as of March 2018).

Most of these newcomers to Neukölln have indeed higher educational backgrounds and incomes than the area’s long-standing population and business people. New residents mostly come from Germany or Western Europe as opposed to many of the current residents who have often Turkish, Palestinian, Lebanese, or Polish roots. This shift in demographics is reflected by the new construction sites and partly in the types of new businesses opening up in the area: organic stores, lifestyle cafés, upscale restaurants, galleries, and designer boutiques. The local business people also remark on these changes:

Many young people are coming, well students, now! I already realize that there is so much movement. Which is beautiful, of course, they will in some time, yes, eventually they will stay, when they earn money later in the future […] [the neighborhood] has changed, but when you’re here every day, then you don’t necessarily see that [change] anymore. Sure, it was better in the old days, but everything was better in the old days […], right, these were different times and we can’t regret bygone times, we need to cope with it. Sure, when I started here 17 years ago, there were banks around my business and the [long standing renowned] luggage businesses and the book store, yes these long-standing businesses, and they aren’t here anymore, of course…. It’s also because of the loss of the customer clientele, of course. Oh well, we have to stick it out (Flower store owner).

The second group of new businesses opening up in the area are less lifestyle oriented but more everyday supply oriented businesses that cater to another new customer group that frequents northern Neukölln: refugees from Syria who look for Sonnenallee as the ‘Arabic street’ – a street where they can provide themselves with goods and services known from their places of origin14. Since 2015, increasingly more businesses that offer products and services known from Arabic countries open on and around Sonnenallee. What has been a cluster of businesses offering Lebanese and Palestinian food for an ethnic German and Arabic customer base, often depicted as ‘Gaza strip,’ changed to an ‘Arabic street’ recently. Most interviewed owners on Sonnenallee arrived as refugees in Berlin mainly in the past five years, whereas the second biggest group of owners came to Germany and Berlin between 1990s-2000s, mainly from Palestine, Lebanon and Egypt. Media coverage from Al Jazeera to Deutsche Welle, The Guardian and The New York Times (among numerous lifestyle magazine, newspaper, blog and TV coverage) has helped the street to gain an international reputation as a street where products and services known from Arabic-speaking countries are sold. Owners on Sonnenallee described their customers as ‘Lebanese, Syrian, Palestinian. People come from all parts of Berlin. Lots of refugees’ and ‘my customers are a mix. Tourists. Turkish, Spanish’. Aside from attracting tourists and ‘foodies’ in their ‘search for authentic Arabic food’ (as one customer describes his motive for coming to Sonnenallee), this is against the wishes of the urban renewal agents, as it goes against their vision.

This means that recent refugee migration and ongoing and enhanced gentrification affect northern Neukölln – socially and physically. However, it is first and foremost the increased competition with the new and more upscale or chain store businesses, rising commercial rents and the displacement of many regular customers that challenge and frame the longer-standing business people’ everyday life and daily work operations on Sonnenallee and Karl-Marx-Straße. But within this gentrification, the new customers who fled Syria help the Arabic speaking businesses to stay put. While the district administration’s main urban planner admits that his and his colleagues’ ‘main focus is on the site’s development,’ the independently owned businesses, gastronomic facilities, retailers, and other service providers are trying to align with the long-standing motto ‘trade is change’ in the face of this state-supported gentrification. Interviewed store owners often frame change as something ‘natural’ for cities and something that they must adapt to, or at least, that they have to ‘stick out’ (flower store owner). But the urban renewal actors use the term ‘trade is change’ to further discriminate against some of the smaller businesses, by downplaying the challenges that they face and neglecting the new ethnically more diverse realities around Sonnenallee: ‘I don’t know and I don’t want to know how they make the money is this business’ (urban planner). They often criminalize many of the newer Arabic speaking businesses, also blaming them for mafia clan structures involved in protection rackets along the street (cf. Sundermeyer 2018). This also affects the longer standing owners and increases racism and mutual blaming. Because of the media coverage that often include statements from local authorities and politicians, one of the longer-standing owners thinks that in the new Arabic speaking businesses, there is ‘a lot of illegal business going on there. They are offensive towards us Turkish people… if somebody offered me a shop there for free - I would not take it! I hate the Arabic people, it’s like another world there’. Other owners (with migration background) on Sonnenallee also adopted the discriminatory behavior of media and local authorities:

So many more Arabs arrived. They do not have any respect; security has only become an issue in the last ten years.

I want a positive change, I feel so uncomfortable here, it’s almost like Little Arabia.

I don’t feel comfortable, I’ve been here since 1995 and back then there were only two Arabic shops, the others were German. It was more safe back then.

Nevertheless, my interviews revealed how – against this backdrop of ongoing business threats and neighborhood change – all local owners work for – and sometimes cooperate for – the development of the street as their common business site and as the ‘centers of their lives’ (e.g. flower store owner) through their everyday social practices (cf. Steigemann 2017, 2018). But the businesses are not the only social centers and hearts for those who work in or own them, they are also the places that foster neighborly interaction among the diverse neighborhood residents. They are the places where friendly and caring conversations take place and a social group is formed for the time spent in the businesses. Neighborhood and community are not synonymous, but are implicitly connected with each other. Despite the fact that community has a longstanding prominent status and is a widely research topic in urban studies, it remains unclear what community actually means. Margrethe Kusenbach (2006, pp. 280 ff.) writes that

Despite the legendary ambiguity of the concept of community, previous overviews largely agree on three basic components that have dominated definitions of community in the past: first, the presence of a shared territory; second the presence of significant social ties; and third, the presence of meaningful social interaction.

This underlines the linkage between the two concepts of neighborhood and community but also their differentiation. Hence, I argue that a local communjty needs a shared space and mutual relationships, but is first and foremost something that is practiced on the level of everyday life. This argument follows Kusenbach’s critique that most community studies have prioritized the territorial and geographical notion of community – neighborhood, town or city – and the ‘relational which was concerned with the ‘quality of character of human relationship, without reference to location’ (Gusfield 1975, p. xvi), over the third element, namely social interaction. However, regardless of whether the definition of community is based on a shared geographical location, social networks, or interaction, community is not necessarily an all-inclusive concept15. Therefore, I left it mostly to my interview partners to define social life and eventually community in their own words.

Furthermore, following Eraydin & Taşan-Kok (2013), I understand commercial streets as crucial places to enable encounters and promote social interactions, thereby settling and integrating customers to their (in this case often new) places of residence. In this context, I found that the interviewed customers and business people that had to leave their countries of origin more recently (just as all interviewed customers and business people) strive not only for work and fight for independence from the welfare system and provisioning regime, but also that they develop close relations with the longer-standing local community around Sonnenallee, often sharing the same ethnicity or place of origin. Both longer-standing and newer business people most often speak Arabic, which enables them to access information and resources to open new shops, creating new jobs and offering special products. As two interviewed store owners framed it,

I like the sense of security that it [Sonnenallee] gives refugees once they arrive here. To many the `Arabic street` is the first stop and once you are here and see something familiar and people that speak your language and can help you settle in, suddenly the city is less strange to you and you aren`t as worried.

Arabic people, they miss Arabic feelings, food, feelings from their countries, so they come here.

Customers described the street and the reasons why they frequent Sonnenallee in a similar way:

It‘s almost like at home. I feel good here and I get everything that I need.

I heard about the Arabic street before I came to Berlin and come here ever since to feel a bit like home. And to meet my people.

My cousin ... invited me to this cafe and now I keep coming back to Sonnenallee to meet others like me.

[I visit] every weekend. A friend told me about the Arabic Street and I googled it. I feel good here.

For Germans, we look different…On Sonnenallee, I can move freely and it feels like at home.

So, while both streets suffer from and are challenged by the upgrading renewal measures, the stores on Sonnenallee but also on Karl-Marx-Straße try to keep up with the new dynamics, demographics, changes and challenges, while nonetheless trying to maintain their close and supportive relationships with regular and new customers. But urban renewal often coopts these efforts. For instance, the interviewed flower store owner also stores and distributes packages – either personal deliveries or postal packages – for residents of adjacent buildings. And as a trusted public character, locals approach her in search of help – be it private problems, debts, asking for directions or traffic schedules, searching for specific goods to purchase on the street, or seeking someone to watch their children while they have a doctor’s, hair, or administrative appointment (for more details, see Steigemann 2017, 2018).

If I wouldn’t do it, then folks would say, what a stupid cow or so, or we don’t go to her business anymore, she’s stupid or, with her, we can’t get along anymore. You know, it‘s the same when they ask me, where’s your hairdresser and then I always say, not here. Word goes around and you know, you lose reputation much easier than you establish it. That‘s why I give [information] out, also because of business interests.

Although she clearly enjoys her reputation as a trusted, knowledgeable, and respected businesswoman, she is nonetheless critical of the strings and expectations attached to this status. However, in the flow of her business operations she never hesitates to help people or provide them with information, obviously relishing the distraction from working routines and the prestige of her status as the person to approach in important matters.

Another interviewed business owner, a family that owns a Syrian bakery on Sonnenallee, for instance, has already 40 years of previous business experience in Syria, enjoying already a well-respected name and reputation by their customers. The staff, building on the already established high level of trust and good reputation, thus help customers with their paperwork (e.g. for renting out apartments, finding jobs, for the asylum bureaucracy). Many newer owners on Sonnenallee also share similar socio-economic and educational background with their customers and often come from big metropoles, such as Damascus, Aleppo, and Homs. An owner from Aleppo said that for him, big cities generally offer more opportunities to work and there are more international people. This ‘cosmopolitan experience’ helps him to bridge and overcome ‘cultural differences’ in Berlin. With this understanding he and his staff try to help other newcomers to settle in Berlin and to develop skills and strategies to get by in their new place of residence. Most often he supports his customers in terms of translation services and forwards them to local NGOs that support refugees. Further research revealed that almost all interviewed store owners offer some kind of social and emotional support, networking and advice to their customers, building on their wide stocks of local knowledge, but also technical and professional knowledge in regard to settling in as well as in regard to applying for asylum and jobs and apartments in Berlin. The high levels of interaction across ethnic lines, mutual support and trust in the stores’ internal social life are somewhat surprising, considering the public image of Sonnenallee and Karl-Marx-Straße as rather anonymous, fast and aggressive and deprived thoroughfares, and with their comparatively high level of ethnic and social diversity. While trust forms the basis for any human relationship, since without it, ‘the everyday life we take for granted is simply not possible’ (Good 1988, p. 32), trust becomes a more urgent concern in today’s more uncertain, polarized, and global conditions (Misztal 1996, p. 9).

By contrast to the more street-level trust building on the two streets, the urban renewal’s official offers and meetings for business people on Karl-Marx-Straße and Sonnenallee reveal high levels of mistrust and distrust between the businesses, especially of franchise and chain stores. This becomes also apparent in the independent owners’ lack of interaction in those meetings. Their exchanges with local officials and business people in the meetings, as reported by both the interviewed store owners and local officials, reveal a stronger focus on increasing business activity and less on mutual social ties and aid. The interviewed urban planner openly admits the business advantage accrued by the corporate partners from attending these meetings; he also acknowledges that participation in these meetings also inherently favors them because their representatives are being paid by their head offices to attend these meetings during working hours:

We also try to include the smaller entrepreneurs, but they are more difficult, it is more difficult to include them in the participation…

In the leading board, the small retailers‘ interests are only indirectly represented, because the big stores‘ managers all have an interest [in ensuring] that the location generally works, yes there’s certainly a gap [no individually owned stores represented]. If they don’t come and represent their interests, they have to take it that others do, in the process… [The chain stores] make then their own locational analyses, […] and they adapt to changing demands.

Rather than reflecting on the reasons for poor participation by the smaller and migrant owned stores, he blames them for being unable, unwilling, or ‘difficult.’ So, while the individually owned store owners receive a high level of trust from their customers and have a good relationship with their small business colleagues, they seem to receive little or no attention, respect, and trust from officials and the bigger chain stores. As of June 2020, the current community board for the development of the street did only include one of the owners of the local individually-owned businesses.

Conclusion: Businesses as important but threatened places where community and diversity are practiced

The interviewed urban planners and other urban renewal agents have a quite different vision for the future of the streets that is often ignorant of, if not downright inimical to, the owners’ manifold community building and serving practices. The local officials are also trying to enforce their own form of placemaking on Sonnenallee and Karl-Marx-Straße. With this placemaking, they plan and work for a diversity different from the current ethnic and social mix on the streets (cf. Fainstein 2005). In reaction, the owners (as the rather everyday and street-level placemakers) transfer important knowledge to their customers about the planned changes and vice versa. This information exchange helps them to deal with or mediate the effects of the urban renewal process. On top of this kind of information exchange, the newer business people that cater to people from Syria also offer help and support with paperwork, translation and with working through the very bureaucratic processes of settling in Berlin and surviving the asylum-seeking process.

However, store owners never subvert the actions and paradigms of the urban renewal agents, nor actively protest them. Despite the owners’ status as ‘public characters’ (Jacobs 1961), their wide knowledge and social networks, they rarely make strategic use of this role. Ironically, the role of local businesses in creating neighborhood social cohesion is thus asymmetric. They help neighborhood residents to settle and to feel more at home, but they themselves are too fragmented and out of touch with each other to engage in collective action around urban renewal. This increases their vulnerability in times of rising commercial rents and state-led gentrification through the ongoing urban renewal around Karl-Marx-Straße and Sonnenallee (for further detail see Steigemann 2017, 2019). The interviews revealed several reasons why they seem only to fight on their own. For instance, the owner of the flower store considers her business to be too small and economically weak to make a difference, while their migrant and refugee status lead both streets’ café owners to expect that local officials will denigrate their participation in the planning process, making them think that they will not be allowed to speak publicly for the businesses, thus excluding them a priori.

This shows great myopia on the part of the urban renewal managers and local officials. Shopping makes up a substantial part of urban everyday life and community formation. Hence, the businesses on Karl-Marx-Straße and Sonnenallee represent a great social asset to the neighborhood and the city. Urban renewal and gentrification pressures on commercial and residential rents in many ordinary neighborhoods like Neukölln threaten the capacity of these places to engage in community building and practiced diversity. Since most of the new, independent-owned businesses in Neukölln, just as in other upgrading parts of Berlin, target the new and more affluent demographics and sell comparatively higher priced goods and services, this decreases the number of places that the long-term residents have to meet and interact. The displacement of the low-threshold businesses thus parallels and is equally important to the displacement of longtime residents. Or, in other words, the displacement of the low-threshold businesses means nothing less than the displacement of community places. And for Sonnenallee, the Arabic-speaking longer-standing business people and their staff and businesses represent not only community places for the longer-term residents but they are also crucial for the more recent arrival and integration of newcomers from Syria into Berlin.

The case study of Karl-Marx-Straße and Sonnenallee has demonstrated that while diversity has become the new orthodoxy of city planning, current existing diversities are often overlooked and not appreciated in urban planning and revitalization programs. If planned environments can produce diversity, or only a ‘staged authenticity (Fainstein 2005, p. 11; Zukin 2009) for those with the means to afford it, such diversity also worsens the local economic structure and livelihoods of local businesses. The analysis of store owners’ practices that make community (at least for the time spent in the business) also shows that urban renewal agents should work more for economic development (and housing) policies that benefit lower or no income groups and all ethnic groups, instead of thinking as one urban planner involved in the renewal of Karl-Marx-Straße did: ‘We don’t need another cell phone store, we’d rather need a French or Italian fine dining restaurant here’. Thus, I suggest the approach should be diversity mainstreaming for urban development rather than planning for diversity or valorizing diversity in planning. Unfortunately, so far, it is the latter that dominates in the renewal program.

This is all the more important because the businesses on Karl-Marx-Straße and Sonnenallee reveal a unique ability to sustain the intangible social life of cities despite the high ethnic, social and commercial diversity, new increased in-migration, the high commercial fluctuation, the heightened competition and the perceived anonymity: ‘Karl-Marx-Straße is not as anonymous as it seems. Behind the curtain, it does work’ (flower store owner). With their micro- and small-scale interactions, these businesses elicit a sociability that, for some, might seem romantic or recall ‘village life’ (Zukin 2012, p. 10). In fact, these are quite real characteristics of neighborhood urban life as these contact sites bring together previously unacquainted people and thus mediate strangeness and familiarity in an increasingly diverse city.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank my Architecture, Urban Design, and Planning students at TU Berlin who conducted many of the interviews with the Sonnenallee store owners in the fall semester 2017. A big thank you also goes to the business people on both streets for inviting us to their small life worlds and talking to me and the students.

References

Amin, A. 2010, Cities and the ethic of care for the stranger. Joint Joseph Rowntree Foundation/University of York Annual Lecture, 3. https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/cities-and-ethic-care-stranger

Amin, A. & Graham, S. 1997, ‘The ordinary city’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 411-429. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-2754.1997.00411.x

Dangschat, J. S. & Fasenfest, D. 1995, ‘(Re)structuring urban poverty: the impact of globalization on its extent and spatial concentration’, in Chekki, D. (ed.), Urban Poverty in Affluent Nations. Research in Community Sociology, vol. V, JAI Press, London, pp. 35-61.

Eraydin, A. and Taşan-Kok, T. 2013, Resilience Thinking in Urban Planning, Springer, Dordrecht.

Everts, J. 2010, ‘Consuming and living the corner shop: belonging, remembering, socialising’, Social & Cultural Geography, vol. 11, no. 8, pp. 847-863. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2010.523840

Everts, J. 2015, Konsum und Multikulturalität im Stadtteil: eine sozialgeographische Analyse migrantengeführter Lebensmittelgeschäfte, transcript Verlag, Bielefeld.

Fainstein, S. S. 2005, ‘Cities and diversity should we want it? Can we plan for it?’, Urban Affairs Review, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087405278968

Gilroy, P. 2004, After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture, Routledge, London.

Glaser, B. & Strauss, A. L. 1967, The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Theory, Aldine, Chicago.

Good, D. 1988, ‘Individuals, interpersonal relations and trust’, in Gambetta, D. (ed.), Trust: Making and Breaking Relationships, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 31-48.

Hall, S. 2012, City, Street and Citizen: The Measure of the Ordinary, Routledge, London.

Hall, S. 2015a, ‘Migrant urbanisms: Ordinary cities and everyday resistance’, Sociology, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 853-869. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038515586680

Hall, S. 2015b, ‘Super-diverse street: a ‘trans-ethnography’ across migrant localities’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 22-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.858175

Hall, S. 1993, ‘Culture, community, nation’, Cultural Studies, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 349-363.

Hangebruch, N. & Krüger, T. 2014, ‘Facheditorial Einzelhandel und Stadt’, in: Raumplanung. Fachzeitschrift für Räumliche Planung und Forschung, vol. 176, no .6, pp. 6-7.

Häußermann, H. & Siebel, W. 1987, Neue Urbanität, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt-Main.

Häußermann, H., & Kapphan, A. 2002, Berlin, Leske+Budrich, Opladen.

Häußermann, H. 2011, ‘Das Bund-Länder-Programm „Stadtteile mit besonderem Entwicklungsbedarf–die Soziale Stadt’, in Dahme H. & Wohlfahrt N. (eds) Handbuch Kommunale Sozialpolitik, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp.269-279. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-92874-6_20

Hillmann, F. 2018, ‘Migrantische Unternehmen als Teil städtischer Regenerierung’, In: Emunds, B. Czingong, C. & Wolff, M. (eds.), Stadtluft macht reich/arm. Stadtentwicklung, soziale Ungleichheit und Raumgerechtigkeit, Metropolis-Verlag, Marburg.

Hillmann, F. (ed.) 2011, Marginale Urbanität. Migrantisches Unternehmertum und Stadtentwicklung, transcript Verlag, Bielefeld.

Hillmann, F., Bernt, M. & Calbet i Elias, L. 2017, ‘Von den Rändern der Stadt her denken. Das Beispiel Berlin’, Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, vol. 67, no. 48, pp. 25-31.

Hillmann, F. & Sommer, E. 2011, ‘Döner und Bulette revisited oder: was man über migrantische Ökonomie genau wissen sollte’, in Hillmann, F. (ed.), Marginale Urbanität. Migrantisches Unternehmertum und Stadtentwicklung, transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, pp. 23–86. https://doi.org/10.14361/transcript.9783839419380.23

Hüge, C. 2010, Die Karl-Marx-Straße: Facetten eines Lebens- und Arbeitsraums, Kramer, Berlin.

Huning, S. & Schuster, N. 2015, ‘“Social Mixing” or “Gentrification”? Contradictory perspectives on urban change in the Berlin district of Neukölln’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 738-755. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12280

Jacobs, J. 1961, The Death and Life of great American Cities, Vintage, New York.

Kloosterman, R., Van der Leun, J. & Rath, J. 1999, ‘Mixed embeddedness: (in) formal economic activities and immigrant businesses in the Netherlands’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 252-266. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00194

Kuppinger, P. 2014, ‘A neighborhood shopping street and the making of urban cultures and economies in Germany’, City & Community, vol.13, no.2, pp.140-157. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12064

Kusenbach, M. 2006, Patterns of neighboring: Practicing community in the parochial realm’, Symbolic Interaction, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 279-306. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2006.29.3.279

Mayer, M. 2012, ‘The “right to the city” in urban social movements’, in Brenner, N, Marcuse, P. & Mayer, M. (eds.), Cities for people, not for profit, Routledge, London, pp. 75-97.

Misztal, B. 1996, Trust in Modern Societies; Polity Press, Cambridge.

Reckwitz, A. 2002, ‘Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing’, European Journal of Social Theory, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 243-263. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225432

Reckwitz, A. 2016, ‘Practices and their affects’, in Hui, A., Schatzki, T. & Shove, E., The Nexus of Practices; Connections, Constellations, Practitioners, Routledge, London, Chapter 8.

Schatzki, T. 1996, Social Practices; A Wittgensteinian Approach to Human Activity and the Social, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Schatzki, T. 2001, ‘Introduction; Practice theory’, in Schatzki, T., Knorr-Cetina, K. & von Savigny, E. (eds.), The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory, Routledge, London.

Shamsuddin, S., & Ujang, N. 2008, ‘Making places: The role of attachment in creating the sense of place for traditional streets in Malaysia’, Habitat International, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 399-409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2008.01.004

Shove, E. & Trentmann, F. (eds.), 2018, Infrastructure in Practice, Routledge, London.

Staeheli, L. & Mitchell, D. 2006, ‘USA’s destiny? Regulating space and creating community in American shopping malls’, Urban Studies, vol. 43, nos. 5-6, pp. 977-992. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600676493

Steigemann, A. 2018, The Places where Community is Practiced. How store owners and their businesses build neighborhood social life. Springer, Dordrecht.

Steigemann, A. 2017, Offering ‘more’? How store owners and their businesses build neighborhood social life, TU Berlin University Press, Berlin.

Sundermeyer, O. 2018, Die Clans. Arabische Großfamilien in Deutschland. Kontraste. 2 Augustt 2018, https://www.rbb24.de/politik/beitrag/2019/11/interview-olaf-sundermeyer-clans-clankriminalitaet-film-ard.html accessed 11/06/2020

Wessendorf, S. Commonplace Diversity: Social Relations in a Super-Diverse Context, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Yildiz, Ö. 2017, Migrantisch, weiblich, prekär?: Über prekäre Selbständigkeiten in der Berliner Friseurbranche, transcript Verlag, Bielefeld.

Zukin, S. 2012, ‘The social production of urban cultural heritage: Identity and ecosystem on an Amsterdam shopping street’, City, Culture and Society, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 281-291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2012.10.002

Zukin, S. 2009, Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

1 I subsumed the interviewed urban planners, politicians and administrative workers as urban renewal agents. They work for the area’s upgrading through the mentioned programs and are employed by the city government, the senate, the local district administration and hired private planning offices. Their visions for the street and its future structure are more nuanced in the interviews than in their common publications.

2 According to Suzanne Hall (2012, 2015a), the quotidian perspective of the ‘ordinary’ and the ‘everyday’ offers a view of migration as integral to ongoing processes of societal change and diversification, rather than as the exception to it. It recognizes the significance of the day-to-day life and encounters of urban migration and urban multi-culture and pays attention to casual interactions among diverse individuals and groups, all of which also exhibit important dimensions of conviviality (Gilroy 2004) and commonplace diversity (Wessendorf 2014).

3 The definition of community has been left up to the interview partners and not the interviewer (myself). Community (“Gemeinschaft”) is as a very strong or even archaic term in German, denoting very strong and tight ties, and is therefore rarely used in everyday language. But if conceptualized as something that is practiced over the course of daily life, the respective community building practices and utterances can be observed empirically.

4 Tagesspiegel, 13.01.2018 https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/neukoelln-der-nahostkonflikt-im-kiez/1139718.html BerlinerKurier,12.08.2013, https://www.berliner-kurier.de/berlin/polizei-und-justiz/aktion-araber-mafia-berlin-erklaert-kriminellen-grossfamilien-den-krieg-3931370

5 While the butcher sees his personal low-point in 2004/2005, he considers 2006 as the low-point for the entire North Neukölln area.

6 GfK (2015) GfK-Studie zu den Rahmenbedingungen für den Einzelhandel in 32 Ländern Europas, http://www.gfk.com/de/insights/press-release/einzelhandelssituation-in-den-europaeischen-krisenlaendern-verbessert/, accessed 11/25/2017 .

7 Berlin.de (n.d.). Sanierungsgebiet Neukölln – Karl-Marx-Straße / Sonnenallee. http://stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/staedtebau/foerderprogramme/stadterneuerung/de/karl_marx_str/index.shtml, accessed 02/19/2016 .

8 As mentioned by all urban planners and their material, e.g. for Aktion KMS, see: Aktion! Karl-Marx-Straße (n.d.). Umbau der südlichen Karl-Marx-Straße, http://www.aktion-kms.de/projekte/umbau-karl-marx-strasse/suedliche-karl-marx-strasse/.

9 This program was established in 2008 in order to improve the economic and structural situation of selected urban shopping streets. Thereby cooperation with local retailers and retail associations is seen as key to the street’s development.

10 Cf. Aktion! Karl-Marx-Straße (n.d.). Der aktuelle Newsletter der [Aktion! Karl-Marx-Straße], http://www.aktion-kms.de/sanierung/bereich-karl-marx-strasse/konzepte-bis-2007/ (2008, p.3).

11 Aktion! Karl-Marx-Straße (n.d.). Der aktuelle Newsletter der [Aktion! Karl-Marx-Straße], http://www.aktion-kms.de/sanierung/bereich-karl-marx-strasse/vorbereitende-untersuchungen-nach-141-baugb/ .

12 2005 and particularly 2006 are repeatedly named across all interviews as the neighborhood’s nadir.

13 RBB: Abendschau (02/05/2015), http://www.rbb-online.de/abendschau/archiv/archiv.html.

14 E.g. Al Jazeera: Welcome to Syrian Berlin: A refugee tour of the city. Six sets of Syrians living in six different districts of the German capital explain what being a Berliner means to them, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2016/02/syrian-berlin-refugee-tour-city-160211132536180.html

15 As such, it is often used to muffle political opposition, and as a critique in the name of civility (Staeheli & Mitchell 2006). Inasmuch as I claim that some of the businesses serve as the heart of the community for some residents and staff – or essentially as a community center – community seems to be an appealing alternative to public life (within a privately owned space). Community as a concept promises to provide the pleasures of public sociability without the discomforts of the unfamiliar, which hints at the exclusionary dimensions of community (Steigemann 2019, pp. 73ff).