NEW: Emerging Scholars in Australian Indigenous Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1 2020,

ISSN 2208-1232 | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/student-journals/index.php/NESAIS

SITE VISITS

Waraburra Nura

Manning Nolan-Laykoski

University of Technology Sydney, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, PO Box 123, Ultimo NSW 2007, Australia. manning.nolan-laykoski@student.uts.edu.au

Citation: Nolan-Laykoski, M. 2020. Waraburra Nura. NEW: Emerging Scholars in Australian Indigenous Studies, 5:1, 1-3.

© 2020 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

My visit to the UTS’s Indigenous Art Collection and the Waraburra Nura (the Happy Wanderers place) Indigenous garden afforded me the opportunity to re-engage once again with the knowledge that my white privilege has a black history. As a member of the Munnungali clan and Yugambeh Nation-Language people who reside in the Bouedesert area of the Gold Coast Hinterland, I am already deeply connected and sensitive to issues of Colonial representations of history, the role of Indigenism in contesting Western knowledge orthodoxies, the importance of pushing back against the reproduction of the colonised as fixed identities and why under-theorizing the deprived and disadvantaged Australian Indigenous human condition, allows it to proliferate. As a whole, Jennifer Newman’s and Alice McAuliffe’s talk and the artwork on display reflected Indigenous survival, resilience and thriving. It also reflected the relationship between art and politics, not only because it represented both Western and Indigenous political ideology, through an account of political events of historical moments in time, but also because it illustrated how the artist themselves (since their art production is a commitment to a political stance) belong to the political realm.

In the Western context, art is often a demonstration of authority and power. Reflexively non-Western Indigenous art produced and displayed within the Western context illustrates questions of colonialism, sovereignty and appropriation. More specifically, the aesthetics represented in the array of UTS’s Indigenous art instillations for me, signified a pushing back in a kind of politico-artistic resistance kind-of-way against the ‘othering’ of Indigenous culture and understanding. Indigenous art therefore, for me, stands in stark contrast to traditional ‘primitivizing’ art representations of Indigenous peoples.

The plants of Waraburra Nura’s native garden illustrates the richness and complexity of Indigenous culture in the Sydney basin area. It demonstrates how Indigenous peoples adapted to life in a harsh environment over thousands of years, through their deep local knowledge and use of Indigenous medicinal, nourishing and nutritional plants. This powerful legacy, as a point of comparison, inspires Indigenous and non-Indigenous visitors not only to renegotiate their own understanding of the colonial encounter, but also to consider apprising themselves of the value of Indigenous ‘ways of knowing, being and doing’. This is something that my own mixed-race family has struggled with, especially in the face of their own deeply personal history of internalised racism.

Classmate drawing words into the wood

Finally, I think intuitively and tangibly, both the artwork and the Indigenous garden offer great insight into why there is a need for more in-depth analysis and re-evaluation of Australian history comprising Indigenous perspectives. Moreover, winning the struggle for Indigenous Australian intellectual sovereignty and representation in Western science with regard to ways of knowing, being and doing is paramount if we are to future-proof Aboriginal communities from the coloniser’s handicap and embark on a truly non-neo-colonial future.

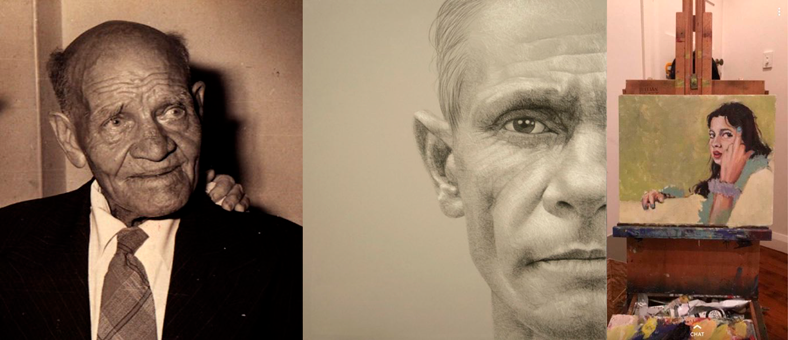

Left to right: my great great grandfather, Veron Ah Kee “Grandfather Gaze”, painting of myself by Archie Tait.

As an extension of my personal experience in the gallery, I came home and I juxtaposed these three portraits to illustrate how through time and space, the spirit, the core, the essence of Aboriginality, and especially for me, my rightful lineage is indestructible. I think the changes in generational attitude, laid bare through each individual and distinct gaze is self-evident.

References

AHRC, n.d. About Constitutional Recognition, Australian Human Rights Commission, <https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/about-constitutional-recognition>.

Australians Together, n.d. What about History?, <https://australianstogether.org.au/discover/australian-history/get-over-it/>.

Taylor, C. n.d. The Politics of Recognition, <https://online.uts.edu.au/bbcswebdav/pid-3176766-dt-content-rid-40666776_1/courses/54085-2019-AUTUMN-CITY/Taylor%281%29.pdf>.

Person, N. 2014, A Rightful Place: Race, Recognition and a More Complete Commonwealth, QE SS, <https://online.uts.edu.au/bbcswebdav/pid-3176768-dt-content-rid-40666747_1/courses/54085-2019-AUTUMN-CITY/PEARSON%20A%20RIGHTFUL%20PLACE%282%29.pdf>.