NEW: Emerging Scholars in Australian Indigenous Studies, Vol. 2-3, No. 1, 2016-17

ISSN 2208-1232 | Published by UTS ePRESS | epress.lib.uts.edu.au/student-journals/index.php/NESAIS

REVIEWS

Grandmother’s Country: history, art and survival

Stephanie Rago

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/nesais.v2i1.1482

Citation: Rago, S. 2018. Grandmother’s Country: history, art and survival. NEW: Emerging Scholars in Australian Indigenous Studies, 2-3:1, 87-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/nesais.v2i1.1482

© 2018 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

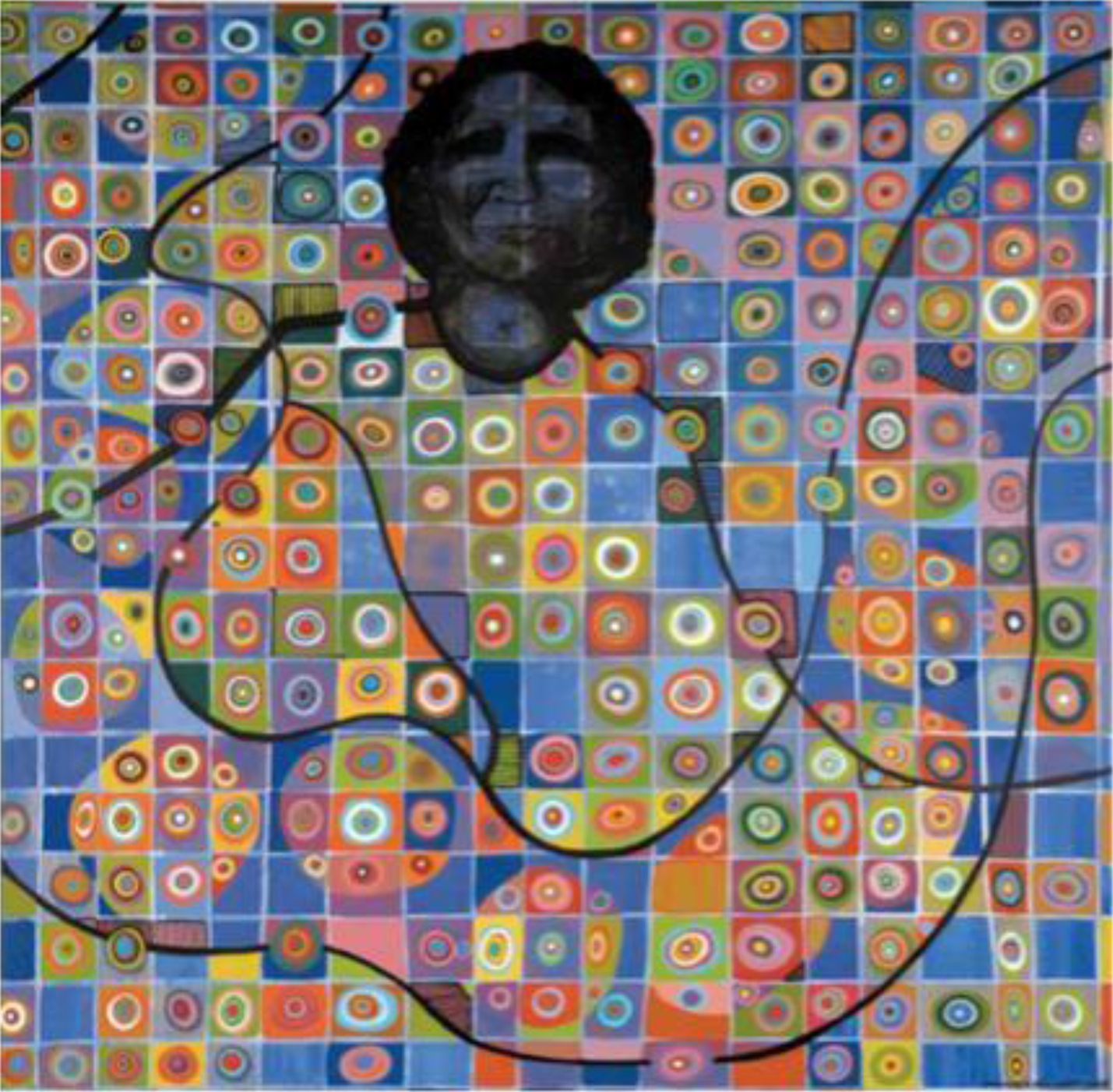

Grandmother’s Country (2005), Bronwyn Bancroft, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 149.5 x 149.5 cm, Macquarie University Art Collection.

The focal point of the Mystic Conversations series, Grandmother’s Country is more than an interpretation of spiritual identity; it is also a testament to the strength and power of Aboriginal women in Australia.

Bronwyn Bancroft, a Djanbun woman, is no stranger to the art world. She was one of the first Australian fashion designers to showcase her work in Paris; she has illustrated and authored a plethora of children’s books; and she was a founding member of the Indigenous artist co-operative Boomalli in the late 1980s. Originally from Tenterfield, New South Wales, Bancroft exhibits her personal exploration of her Aboriginal identity through colourful creations,

When I draw and paint… [it] creates a passage to freedom and to creative visual stories that mean something to me. The things that I create are all personal stories, some understood and some not… [it is] the journey to be human, to feel, to be Koori (Board of Studies 2007, p. 10; Artlink 1990).

Displayed at Macquarie University as an essential ingredient of the series, Grandmother’s Country showcases a “proud and wise Indigenous woman” (Simpson 2015, p. 19) as the prime focus. Her dark complexion and unpresuming expression contrast greatly to the grid-like pattern that holds bold concentric circles in its frame. A style familiar to Bancroft, the juxtaposing shapes and lines are quite unique. They suggest a “series of interrelated stories”, and when placed amidst the greater grid of the dreaming, they represent a much larger, more powerful system of knowledge (Simpson 2015, p.19). The shape of the woman’s body is made up of dark, intersecting lines that cut through the colourful grid. They curve and sweep across the artwork, intrinsically connecting the woman to the stories, as they are not only shown encapsulating her surroundings, but also as indispensable to the make-up of her being - physically and spiritually. Opposing the traditional Aboriginal ochres, Bancroft’s use of bold and bright colours in Grandmother’s Country brings contemporary elements to a deeply spiritual creation.

History, Art and Survival

As Bancroft states herself, “art is everything to Aboriginal people” (Board of Studies 2007, p. 11). Centred on story-telling, Indigenous Australian art is used to pass on information to following generations to preserve culture. Through art, vital messages of knowledge of the land, beliefs and rituals are shared. Today, Indigenous women are believed to be the leaders of the Indigenous art world, as toward the end of the twentieth century, they forged an arts sector that became internationally renowned. With their art they have kept culture alive by taking on new forms of living and surviving (Haebich and Parsons 2014) - a direct reaction to the effects of colonisation, as artist Lyida Miller, a Kuku Yulanji woman, reveals;

Before 1788 our peoples had to think survival… Though the world has changed and the role of our performance may have as much to do with political survival, social awareness, and the need for systematic change, the power and the role of the artists is to think survival (Haebich and Parsons 2014; Enoch, p. 349).

The long and enduring effects of colonisation have undermined the role and power of women via many avenues, but it was through popular opinion of Aboriginal people at the time of white settlement that instigated these consequences. Aboriginal people were seen as primitive and “animal-like”; they were seen as a race that could not be “saved” (Morris 1992, p. 73-4). Grounding principles in law-making and social norms in early Australian society, this discourse was further engrained into society by academics and historians that perpetrated and encouraged this way of thinking, whether it be consciously or subconsciously (Stanner 1969).

As a consequence of the imposition of White doctrine upon Aboriginal people, child removal policies (in one way or another) were implemented in each State. Detrimentally, this form of ‘protection’ and ‘assimilation’ led to the destruction of Aboriginal women’s rights, the expungement of voices and the disintegration of familial systems. Due to these subjugations, Aboriginal women were sometimes found to ‘brush off’ their experiences, or if they chose to share their story, there was no one that wanted to listen to them (Attwood 2001, p. 187-8). The silence that was created was what Attwood describes as a “means of survival” (p. 187) - and it is this silence that artists have strived to liberate.

Indigenous activists and artists started “talkin’ up” to the White people (Clark and Kelada 2013, p. 40) and thus, bridges began destroying the divides. In the art world, the 1970s saw slight changes of perspective with the deconstruction of stigma and stereotypes by artists Fiona Foley and Julie Gough. Rurally, during the 1980s, there was an increase of female Aboriginal artist clusters, who were respected in their communities for their knowledge and leadership, and for their support of their families through art sales - like the women of Papunya Tula. Also in the 1980s, urban artists, including Bancroft, challenged popular misconceptions and helped to shape representations of contemporary Indigenous culture (Haebich and Parsons 2014) through striking contemporary pieces.

Grandmother’s Country is one of many artworks that is emblematic of contesting common beliefs and recreating discourse of the Aboriginal woman. With Grandmother’s Country, Bancroft builds upon historical consciousness in a way that creates a window for non-Indigenous Australians to understand and participate in discussion of Aboriginal culture and survival (Mercer 2013). By depicting the ‘wise’ Indigenous woman at the forefront of her artwork, Bancroft “reclaim[s] a gaze which speaks directly to a colonial past and present” (Clark and Kelada 2013, p. 39). She strategically “takes control of the frame” whilst repossessing racial identity (Clark and Kelada 2013, p. 39). More importantly, Bancroft liberates the Other through Grandmother’s Country by giving voice to the “marginalised and the silenced” and by reconstructing past atrocities and misconceptions for the present audience (Fredericks 2010, p. 547-8).

Bancroft, alongside her Aboriginal art realm compatriots, has forced her way into the public sphere, and hence into popular discourse. She has forged a spaced for her art and her message to be heard, and it is with this intensity and “moral power” (Fisher 2012, p. 262) that Bancroft has been able to explore her Aboriginal identity and protest politically, culturally and socially through her art.

References

Attwood, B. (2001) “Learning About the Truth: The Stolen Generations”, in B. Attwood & F. Magowan (eds.), Telling Stories: Indigenous History and Memory in Australia and New Zealand, Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, pp. 182-212.

Board of Studies (2007) Affirmations of Identity: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Visual Artists Resource Kit, Board of Studies NSW, Sydney.

Clark, M. and Kelada, O. (2013) “Bodies on the Line: Repossession and ‘Talkin’ up’ in Aboriginal women’s art”, Artlink, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 39-43.

Fisher, L. (2012) “The Art/Ethnography Binary: Post-Colonial Tensions within the Field of Australian Aboriginal Art”, Cultural Sociology, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 251-70, https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975512440224

Fredericks, B. (2010) “Reempowering Ourselves: Australian Aboriginal Women”, Signs, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 546-50, https://doi.org/10.1086/648511

Haebich, A. and Parsons, J. (2014) “Indigenous Women and the Arts”, The Encyclopaedia of Women & Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia, viewed: 8 April 2017, http://www.womenaustralia.info/leaders/biogs/WLE0383b.htm

Mercer, P. (2013) “Australia’s Indigenous Art: ‘An Economic Colossus”, BBC Culture, 2 May, viewed: 15 April 2017, http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20130426-australias-aboriginal-art-craze

Morris, B. (1992) “Frontier Colonialism as a Culture of Terror”, in Power, Knowledge and Aborigines, La Trobe University Press in association with the National Centre for Australian Studies Monash University, VIC, pp. 72-87, https://doi.org/10.1080/14443059209387119

Simpson, A. (2015) “Bronwyn Bancroft (b. 1958) Grandmother’s Country, 2005”, Macquarie University Art Collection 50 Highlights, Macquarie University, pp. 18-19.

Stanner, WEH (1969) “The Great Australian Silence”, The 1968 Boyer Lectures: After the Dreaming, Sydney, ABC Enterprises, pp. 18-29.