PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies

Vol. 19, No. 1/2

December 2023

CREATIVE WORK

Paisaje pegajoso/Sticky sororidad Crónica

Susana Chávez-Silverman

Corresponding author: Professor Susana Chávez-Silverman, Romance Languages and Literatures, Pomona College, 333 N. College Way, Claremont CA 91711, USA, susicronista@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/pjmis.v19i1-2.8821

Article History: Received 20/09/2023; Accepted 02/10/2023; Published 22/12/2023

Abstract

This crónica is really the first time I’ve written about my childhood. As I’ve noted elsewhere, I have many black holes—up to my early teens, when things sort of snap into focus. Hi-res focus, even. Although I’ve lived in and visited a number of countries whose cuisine is imprinted in my memory and even my day-to-day practices in southern California, I decided to focus on only one place: Zapopan (Guadalajara), Jalisco, México, where I spent summers with my family as a young girl. After informally interviewing my sister, Sarita—my closest childhood compinche (she’s only 18 months younger)—I decided to take this issue’s prompt, the notion of sticky memories/emotions, literally. Stickiness functions as a sensorial structuring motif, recurring in different ways in each of my crónica’s four vignettes. However, as is my wont, it offers no sense of resolution or closure. Rather, it appears as a floating signifier: these memories of scent, taste, feel and place have ‘stuck’ with me throughout my life, but they evoke neither univocal nor consistent feelings. The same image or memory can feel now comforting, now disquieting, homely yet uncanny, familiar yet alien. Ultimately, it is this ecotonic, interstitial modus vivendi, which I’ve been inhabiting since about age four, that I hope to convey to the reader.

Keywords

Sticky; Memory; Memoir; Mexico; Bilingual; Childhood

Paisaje pegajoso/Sticky sororidad Crónica

22 julio, 2023

Heatwave Claramonte, Califas

© Susana Chávez-Silverman

Para Sarita, gracias por tus technicolor recuerdos,

que me rellenan los black holes

Once upon a time en Zapopan (Jalisco, México)

Cajeta-making Witness ¿o no?

First of all, no dejes que nadie te diga que la cajeta y el dulce de leche are the same thing. ¡No güey! I grew up with cajeta. I have that smoky-sweet, slightly tangy, burnt caramel sabor-olor tatuado en el corazón. Ahhhh, they would tell me in Buenos Aires, cuando me daban a probar los famous alfajores filled with dulce de leche, si es igual a la cajeta de los mexicanos. ¡Chale to that, ‘Tinos! I love you guys heaps, pero na’ que ver. El dulce de leche es pale, y sobre todo re empalagoso. Los ‘Tines looove their sweets, pero uf, I can’t… Y el alfajor mismo, o sea las cookies que componen el sandwich, no son crunchy—which might actually almost save the day—sino más bien blandas, crumbly. Como wannabe Scottish shortbread pero más sosas.

Ajá. That’s it. No soy nada sweetaholic, la verdad. Los sweets que me enloquecen son few and far entre, y sobretodo tienen que tener… no sé. Some kind of spark. Algo incongruente, unexpected. Hasta weird. Like that lúcuma ice cream que probé en Tsile años ha. LITTLE EYE: en el rubro ALFAJOR, definitely los de Cordy—judging by los que me ha regalado Giuliano Richetta, mi (muy corDObés) teaching assistant—son los mejores. By a mile! They’re huge y las cookies son más spongey o cakelike. Se les nota bahtante menos la corn starch. ¿Y el resheno? To my surprise, algunos venían con una especie de dark chocolate-flavored dulce de leche filling, y hasta llevaban hard chocolate coating. Yum! Pero…why are we talking about alfajores? Ah, claaaro (pronunciación porteñísima). Por lo de la cajeta.

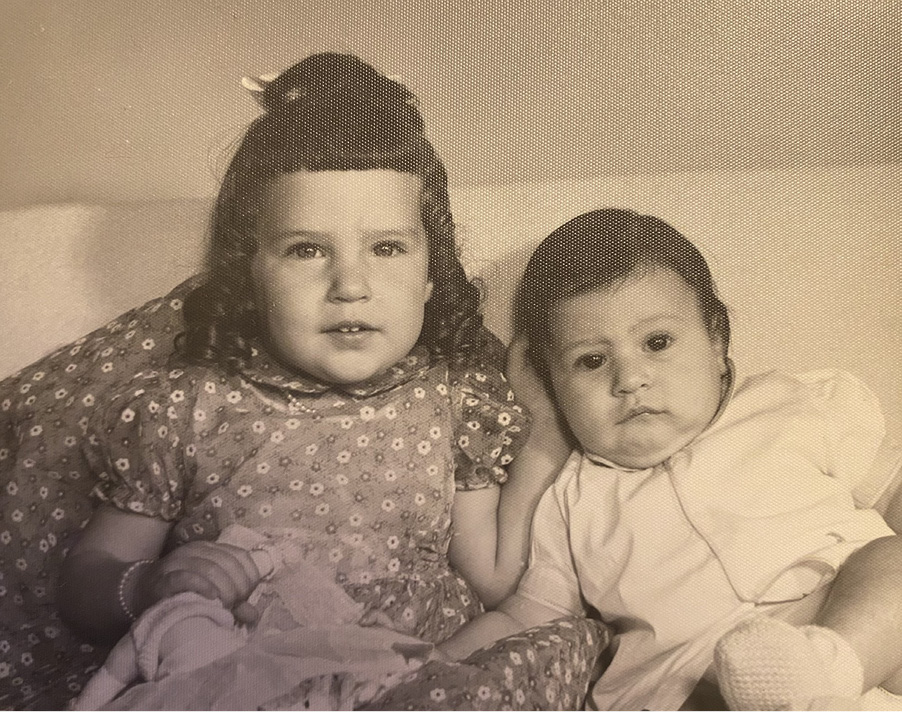

Susana (left) and Sarita © Susana Chávez-Silverman

Bueno, el tema es que Sarita alleges that we—o quizás she—learned how to make homemade cajeta en casa del Cajeta Man. When I consulted her, hace poco, indagando sobre los Greatest Hits de nuestros sensorial (and especially culinary) capers en Guadalajara para esta sticky crónica, esto es lo primero que se le ocurrió. Whaaaat? le dije, That sounds vaguely menacing. Not at all, me responde coolly. No seas drama queen. Are you sure there was really a Cajeta Man en Zapopan, en el barrio? 100%, me dice. Y de allí, she lances into an elaborate tale: una casa oscura, un very nice man mixing los ingredients in a nondescript kitchen, luego boiling la mixtura en una lata posada en una cacerola, filled partway with water que el señor dejaba casi hervir, bubbling gently, gently. I don’t remember any of this, me quejo. Pero I clearly remember ese unique, bewitching scent, le digo. Y el tangy, semisweet sabor de la freshly-made cajeta. El secreto es la leche de cabra, ¿remember?, prompts Sarita. You must’ve been there. Or not, refunfuño. Pa’ mí es puro black hole—salvo la parte sensorial. ¿Será fake memory?, le pregunto, bien disconcerted. No seas creepy! me amonesta Sarita. Pero ni modo anyway. You know the story, que no?

Recogiendo las ‘Pinks’ (dizque flowers)

Los next-door neighbors en Zapopan eran los Gómez Pardo, an upper middle class family. Que yo recuerde, el papá era lawyer y la mamá una elegant lady, tirando a formal. Pero they barely enter into this. Para Sarita y para mí, lo mejor de los Gómez Pardo era la manada de kids que tenían. Los parents moved in different círculos: los nuestros recibían visitas de algunos de sus gringo friends from the Valley (where we lived el resto del año), o hangueaban con universitarios o bohemios tapatíos mientras que los GP brindaban comidas y fiestas más stuffy. And they went out a lot, vestidos bien fancy, dejando a los kids con la criada (whom they called ‘la muchacha’).

There were three or four sons, creo, y una hermanita, la benjamina, called Larisa. La considerábamos beneath us, por demasiado baby, so we rarely played with her. Nuestra obsesión eran los GP boys. O al menos, two or three of them. El mayor, Martín, nos llevaba unos años. Era algo serio—he only graced us with his presence de vez en cuando. Abelardo le seguía. Y a pesar de (¿o por?) su prominent-jawed melancolía (cual pre-teen Mexican Felipe IV, la verdad), me fascinaba. We were, creo, about the same age aunque con el pasar de los años, I began to semi tower over him, por mis gangly legs sobre todo. Pero I don’t think we minded. Y el tercer mosquetero era Roberto. Le decíamos Beto. Era ocurrente y pícaro. Muy entertaining.

Mirando patrás now, me pregunto por qué mamá nos dejaba hanguear con estos boys, almost every day. Con lo uptight y vigilant que se pondría después, it doesn’t make sense. No me cierra, como dicen los ‘Tinos. Capaz it was because she knew we were still too young como para meternos en nada…compromising. Or maybe porque sabía que los GP boys eran “de buena familia,” o sea modositos. En todo caso, Abelardo and Beto were our cuates and it was walking home with them along the chapopote- and dust-scented road, one sultry, tormenta-threatening late afternoon, que Sarita y yo reparamos en las “pinks.” I have to call them that porque we had no clue what they were called—in any language (and we still don’t).

No idea por qué nos dio por mirarlas—I mean, really look at them—ese día. We’d passed by them day after day pero on that day era como si de repente las viéramos por primera vez: una oddly earthbound pink…nube. Ese día Sarita and I trailed our hands indolently through that soft, fuzzy cloud que se extendía hacia el horizon, clumps and clumps of pink al lado del camino. No despedían perfume, pero they didn’t need to. Eran hermosas. La nube parecía endless trigal, pero pink. Observamos que la cloud la componían hundreds, thousands of individual, pale green tallos: finos, delgadísimos como un hilo. Abelardo y Beto medio se impacientaban, Ya vámonos, ¿no? ¿Qué traen? Pero we ignored them, transfixed by our impromptu rapto plantológico. Descubrimos que al arrancar las wheatlike pink tops—bien carefully pa’ que no se nos echaran a volar, cual dandelion fluff—se desprendía la parte superior del stem. It slipped off easily, dejando la parte inferior (tougher, stiffer) anclada en la tierra rojiza. We picked a bunch of them para regalárselas a mamá.

For some unknown reason—y no me acuerdo cuál de nosotras lo hizo primero—we nibbled at a stem a bit, tentatively, y luego lo chupamos (insane, lo sé—únicamente puedo comparar este gesto a las honey flowers, de las que chupábamos un escaso néctar en los San Fernando Valley summers). De ese finísimo stem salió apenas una little droplet—un elixir terriblemente amargo. Pero a la vez strangely reminiscent. Yuck! we shrieked. Y luego, Pero… yum! Nos partíamos de risa. En eso Abel y Beto se dieron vuelta, exasperated. Mira nomás estas bellas flores, le dije a Abel, pa’ que se calmara. Pero en vez, Guácala, he exclaimed. Y hasta Beto, usually more chill, semi recoiled. Fuchi, eso no se hace. Dejen eso. Stung, we gathered our little clutch of pinks. Se las vamos a regalar a mamá, informó Sarita, haughtily. Jajaja, rióse Beto, ¡qué regalo ni qué ocho cuartos! ¿Mande Beto? le dije icily. Pero qué dices? ¿Por qué? Pos porque… ay, ya ‘sta bien. Ya verás. And then, con una look de ay cuánta pena me das, Abelardo me dijo casi tenderly, Ni modo. Ya vámonos a casa ¿no?

Ni bien llegamos, we barely even looked at los GP boys pa’ despedirnos, de tan sacadas de onda. Al entrar a casa, comenzaba la thunderstorm of the century (actually, esto se repetía casi todos los días): gordísimas gotas splattered down, el viento hacía que las tree branches rasparan el enorme picture window del living que ya había comenzado a traquetear por el thunder. Boom, boom. Criiiic, criic. Sarita and I loved it (we still do), pero aterraba a nuestra little sister, Laurita. Y desconcertaba a mamá—expecting yet another imminent apagón—aunque disimulaba. A todo esto, we’d almost forgotten about our bouquet, ahora algo wilted y tristón. Here mommy, dijimos, un regalito. Ay girls, she sighed indulgently, gracias, pero those are just weeds.

Sarita (left) y yo © Susana Chávez-Silverman

Las stolen guayabas y la leche secreta

Por supuesto, we made the peaces with the GP chamacos. How could we not? Después de todo, aunque Sarita and I hated to admit it, they were right: como regalo, esas pinks no eran pa’ tanto (we didn’t admit it to them, OB-vio!). Abelardo y Beto, and sometimes Martín, nos iniciaron en muchas actividades y pursuits algo... outré. Digo, at first. Pero by the end of each summer ya nos parecían tan normales—tan ‘us’—que we didn’t even notice el factor raro anymore.

He aquí un ejemplo: stealing guayabas de la azotea de la señora Sally Donovan. I mean: de los guava trees que se inclinaban hacia su roof. Generally, we went up the little metal escalera to the roof, luego los boys trepaban al árbol, picked some guayabas y nos las tiraban. Sarita y yo, in turn, las aventábamos a los inocentes que paseaban down below, en nuestra tranquila Zapopan side-street. A todo esto, si los passersby se quejaban con la Sally Donovan, ésta salía a la calle—sometimes with her straw-colored hair todavía en rulos (ay, cómo esto debe haber chocado a los neighbors in 60s Zapopan)—y berreaba Ni-ñows, niiii-ñows, BA-hein-say day a-yí. Right NOW! Oh, how we loved to provoke esas annoying sílabas agringadas! Before she could catch us, nos esfumábamos por la escalera de servicio, laughing maniacally. Conste: I’ve never really understood la tropi-fijación que tiene la gente con las guayabas. Even our abuela Eunice, who would turn them into revolting jalea, pa’ servirla con queso panela. Yuck! La fruta verde is the worst of the worst. Hard y medio grainy a la vez, con un sabor entre strawberry y mango pero ácida ácida, como la toronja. It’s like… eating perfume. ¡Chale! (BTW: Sarita dice que Abel y Beto nos llevaban a la azotea de la Sally Donovan pa’ enseñarnos a volar mayates verdes, pero…esa es otra.)

One time los GP—I think Martín headed this expedition, y la baby, Larisa, may have tagged along—nos llevaron a una misión top secret. Sarita siempre ha creído que nos llevaron a una underground chamber, fíjate. ¿Quéee?, le dije cuando me contó eso. OK, Zapopan era medio rural back then, pero not our barrio. Luego caí en cuenta… funny how memory works. Nos llevaron a un shed, I told her. Remember? It was dark, teníamos que agacharnos pa’ entrar. Había straw all over the floor, cual strangely biblical nest. Oh yeah, me dice. A shed. It was so dark, so stuffy in there que apenas se podia respirar. Y algo olía weird. Not unpleasant, just…

Once our eyes adjusted, vimos que allí yacía la dizque “muchacha” de los Gómez Pardo. Sarita y yo nos quedamos OF ROCK. Se veía bien different sin su uniform. Out of place. Tipo…worn out. Los hermosos cabellos azabache uncombed y algo lank. Parecía estar completely naked, wrapped up en una especie de rebozo, large and rough, demasiado heavy para el calor que hacía. She didn’t seem to mind at all que todos estuviéramos allí—all us kids—embobados. Al contrario, she beckoned us close—I think a couple of us knelt pa’ ver mejor—y allí mero, acurrucadito a su lado, tightly swaddled, dormitaba un brand-new, doll-sized baby. Stick-straight black hair, abundante (los mismísimos cabellos de Sarita, when she was born). He stirred slightly, comenzó a lloriquear y a fruncir y relamerse los teensy rosebud lips y así sin más, with no thought to her público infantil, se destapó y colocó al baby en el plump, bare brown breast. He gurgled and slurped y la mamá se quedó medio in a trance. And us too...

So that’s what that mysterious scent was, nos damos cuenta Sarita y yo. In that dense dark, los olores nos rodeaban. Nos sentíamos casi dizzy, intoxicated. We recognized the scents, pero they were jumbled, dislocated por el insólito contexto. We couldn’t place them back then, or name them. Pero ahora sí: era el olor slightly oily, pungent del jet-black, thick hair y de la piel del newborn. Era el olor de la leche. Sweet, comforting, known pero utterly defamiliarized por ese dark shed (nada lejos, we realized al salir, de la casa Gómez Pardo), por ese soft, slightly prickly and damp nido de paja. By that indigenous ‘muchacha’—ahora mamá—de quien brotaba la leche, y por ese diminutive, avidly slurping baby. Esos scents y sights en extreme close-up nos mareaban, pero we lingered, enveloped, awed. As we staggered outside, hacia la soft Zapopan afternoon light, los hermanos GP swore us to secrecy—y hasta acá we’ve kept our promise. We never told our parents, fíjate. En realidad, creo que we really didn’t have a clear idea de lo que habíamos presenciado, nor the words to tell it. Lately se nos ha ocurrido esta burning question: could that baby have been del abogado Gómez Pardo? A saberrr…

Irma de dos maneras

Criaturas en el corral: animales de granja y un insepto

I’ve wracked my cerebro, searched los recuerdos, pero I just can’t remember cómo ni dónde conocimos a Irma Gallardo. Sarita doesn’t either. For sure, los Gómez Pardo no tenían nothing to see! De hecho ahora que lo pienso, they would probably have looked askance at this amistad. Pero Sarita y yo nunca mezclamos estas friendships. Los GP eran una cosa, Irma, her sister Nacha y toda la familia Gallardo otra. Esto no era adrede, sino solo…instinctive. And just like with the GP boys, no me cierra que Mommy nos hubiera dejado pasar tanto tiempo chez Gallardo. Chez being…un modo de decir. Thinking back: si los GP boys should’ve been off limits—según las strict rules de mamá—just for being boys, you’d think she would have given us a million advertencias, antes de dejarnos ir con Irma y Nacha a jugar. Pero que yo recuerde, she never did. Mamá worried and fussed about everything: el agua (definitely NO) potable, los enchufes y su peligrosísima different current, los apagones, did we eat corn from the Elotero, did we have pinworms…You get the picture, ¿no? Pero she was oddly laissez-faire (quizás más bien clueless) about los Gallardo.

Y los peligros abundaban, that’s for sure. Yo tiraba a shy, way more than Sarita. I blame my first year of school, a los cuatro años, en la España franquista. I hated it! Mamá made Daddy take me, porque berreaba tanto. Hasta me dieron asthma attacks, daily rabietas. Lo más traumático: I was alone. Sarita tenía solo tres años y se quedaba en casa con mamá. Pero anygüey con Irma, I felt safe, relaxed. Lo primero que me gustó de Irma eran sus pierced ears. Me permitía sacar y poner los little earrings y yo quedaba embelesada. I begged and begged, pero mamá me dijo que it was a Catholic thing, or a Mexican thing y que no, no, no. Quedé destroyed. I also loved Irma’s dark wavy hair, su smooth dark skin y su manera tierna, calm.

Irma G and Susi © Susana Chávez-Silverman

Pero hablando de ears: una vez que Sarita y yo estábamos en lo de Irma, sacaron una big metal tub a la yarda. No era como ningún backyard normal. It was just dirt, packed hard pero bien dusty, que barrían constantemente. Actually, it was like a corral. Sarita dice que it was a corral, que don’t I remember the cows, las gallinas? Cuando me lo dice, they immediately come into my mind’s eye. Y te juro que I can smell them (su fur o como se diga, los ever-lurking cowpatties) y las oigo (muuu, muuu, of course, y el flic flic de las fly-swatting colas). We rode them de vez en cuando, insiste Sarita, remember? Cuando ayudábamos a Irma y Nacha a juntarlas a la tarde. Why wasn’t I scared of them? A saber…Pero I remember que nos parecía totally natural que las vacas, de noche, stayed in one room of the house y la familia en la otra.

No me acuerdo de los papás de Irma, solo como shadowy, background presencia. Creo que la mamá sacó esa tub (or maybe it was Nacha). Hasta el día de hoy, si le digo a Sarita, remember the flower water? medio se estremece, bien grossed-out. Habían llenado la tina del pozo, another danger en lo de los Gallardo. Pero a diferencia de las vacas, this one we were not blasé about. Recuerdo que we (almost always) gave that pozo wide berth. Tentaba mucho—we yearned to peer into its black depths—pero creo que it didn’t even have a lid. O quizás solo una precarious, slidey wood thing. Anyway, el agua en la tina se veía dark pink, pero al tocarla we saw that they’d filled it with little purply dried flowers. Irma se agachó, turned her head sideways, se inclinó sobre la tina y la mamá le metió la oreja en el agua, como si nada. She kind of…dunked her, like a bizarre bautizo horizontal. Sarita y yo nos miramos, speechless. ¿Qué tienes? le dije a Irma, finally. Pero she just stayed like that, con la cabeza turned sideways y la oreja underwater, las fuchsia flowers floating around her head. No, si no tiene nada, Nacha reassured us. Es que se le ha metido una tijereta, pero ahora sale. El agua las atrae. Ya verán. Pero we must not have 100% wanted to see, porque Sarita and I both draw a blank now. ¿De adeveras le salió un earwig a Irma? We can’t really say for sure. Y mamá nos dijo, later, que that was a myth anyway.

Irma invited to lunch

El otro día le pregunté a Sarita, did we ever eat anything donde los Gallardo? I never really thought about that, me dice, pero no. We never did. Le preguntaba eso porque I had decided to let myself remember esa vez que invitamos a Irma a comer. I mean, in a restaurant. As usual—little Miss Black Hole—muchos details se me escapan. Like: ¿recogimos a Irma en casa? We would’ve been in the beige Peugeot 404 station wagon que Daddy había comprado en España. We didn’t drive much en nuestro día a día, en Zapopan, y no salíamos mucho a comer. Pero that day recuerdo que fuimos todos: Daddy, mamá, Sarita y yo y nuestra little sister, Laura. And Irma. Dad made a fuss over Irma. Sentada al lado de Irma en ese hot, sticky vinyl rear seat del Peugeot, su unease se me transmitía por la piel del antebrazo and I squeezed her hand, puzzled. La quería mucho and I wanted her to have a good time. Sarita and I loved this resto porque servían comida ‘normal’ (es decir, no mexicana). OJO: adorábamos la comida tapatía, pero cada de vez en cuando we got a nostalgic hankering for something different. Es decir: something familiar de nuestra otra vida.

I think this was maybe un resto italiano or at least, la version tapatía. Sí me acuerdo que estaba en un segundo piso—very fancy, según yo. Siempre me ha parecido que fuimos al centro—es decir, Guadalajara—pero for all I know we never left Zapopan. Irma y yo subimos, holding hands. She was my shadow, cuando normalmente it was the other way around. They seated us outside, en una terraza. Los details de who ordered what no importan, except this: recuerdo perfectamente que I ordered espaguetis con mantequilla, y pedí lo mismo para Irma. When they brought the food todos exclamaron, thrilled. Pero sentí a Irma a mi lado, una burning, hesitant presence. Without even looking over, sabía que algo no andaba. Los espaguetis were sitting there in front of her, hermosamente enroscados, pale and butter-drenched en el large shallow bowl, esperando.

¿Qué, no te gusta? le pregunté medio incredulous. ¿Quieres que te eche quesito encima? No…es que yo…stammered Irma sin mirarme. Susi es que yo nunca… Me quería morir. Crawl debajo de la mesa, like Sarita and I actually had done esa vez en otro restorán cuando Daddy had joined in (más bien cut in) con un trío, irrumpiendo con ‘Regaaaalame esta noche…’ en su prístino tenor. Y, lejos de ofenderse, el solista stopped singing y ese trío had come over to our table, acompañando a papá while he serenaded Mommy. The horror, the horror.

Pero ahora, what could I do? Miré a papá con una look de tierra trágame y thank God mi smooth-as-seda Libra Daddy al rescate le dijo Irma, por qué no te pido unas tortillas ¿sí? And she gave a little relieved risilla nerviosa and then, en un acceso de jovialidad, Daddy even ordered queso fundido con rajas. El mesero le miró medio weird, pero no se inmutó and he brought everything chop-chop y los espaguetis de Irma allí se quedaban, getting cold and sticky y la mantequilla toda cuajada y fea.

Did it all really go down like that? me pregunta Sarita. Oh my God. I didn’t notice any of that. Simón, le digo. Just like that. Y ahora saben por qué, cuando pedía spaghetti with butter para mi muy finicky son when he was small, pa’ mis adentros siempre pero siempre se me abultaba un hard, red-hot knot of shame. And now you know, too, por qué me cuesta tanto rastrear, dredge up de las sea-depths del subconsciente, el tale de este Special Lunch.