Public History Review

Vol. 29, 2022

ARTICLES (PEER REVIEWED)

Materteral Consumption Magic: The Hay’s Rooftop Playground, Christchurch, New Zealand

Katie Pickles

Corresponding author: Katie Pickles, katie.pickles@canterbury.ac.nz

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v29i0.8266

Article History: Received 05/07/2022 Accepted 08/11/2022; Published 06/12/2022

Introduction

Generations of Cantabrians remember the Hay’s Limited department store roof that was open to the public for nearly 70 years from the store’s opening in 1929 until, after growth, mergers and take-over, the 1997 demolition of the then Farmers Trading Company premises. The rooftop playground is an important part of Christchurch’s cultural heritage and its collective memory. This article recovers and analyses the everyday public history of that privately owned commercial space. It presents customers’ memories of the roof and reveals the motivations of those who invented it to lure generations of children up there. Energetic and innovative store manager James Hay’s commercial, civic and welfare concerns are outlined, including his cultivation of workers and customers according to his corporate paternalist beliefs. James Hay’s creation of ‘Aunt Haysl’ and the woman who successfully became her for 37 years, Edna Neville, is explained in relation to wonder, storytelling, fantasy and childcare.

Overall, I argue that the Hay’s rooftop playground was an important modern, urban commercial space where every day public history was made and then nostalgically remade as part of Christchurch’s cultural heritage. I use the term ‘materteral consumption magic’ to capture the central discourses in the roof’s history, to explain its success, and to trace its creation as collective memory. Methodologically, I am influenced by Donna Haraway’s work on the American Museum of Natural History in New York that refers to ‘teddy bear patriarchy’ and follow Huw Halstead’s plea for a diverse and anarchic ‘everyday public history’. 1

I visited the Hay’s roof in the late 1970s and early 1980s. I remember the excitement of catching the lift, not really knowing what to expect, then emerging into an even more crowded, dark and noisy area, full of stuffy air with bodies squashed together, and slowly passing Lego models embedded in rustic black fake rock walls. I remember a smiling Aunt Haysl walking by surveying her domain. There was Father Christmas to meet, the giant doll’s house, dinosaurs to slide down, the mirrors to try out, and an old, overfull frog rubbish bin. By that time, the roof’s faded glory also made it a time travel experience into a mysterious past place. Binding everything together was Aunt Haysl. I remember her serene expression as she greeted the crowds as her kin, welcoming us to her roof as she had done for many years.

What does Materteral Mean?

During the interwar years and beyond, across several cultures, ‘aunts’ and ‘uncles’ were literal and metaphorical welfare guardian figures for children. Veronica Strong-Boag’s Canadian work has uncovered the important place that aunts and caregiving occupy in history. Aunts were central figures in fostering ‘kinship’, and in acting as allies with their siblings and nieces and nephews. They could be especially helpful ‘in addressing the vacuum created by the death of parents’. 2

The Hay’s roof was firmly part of Christchurch’s Anglo-Celtic past that, rather than engaging with Māori mythology, looked elsewhere for its storytelling inspiration. In common with Māori culture, however, was the development of kinship networks that involved the figures of aunts and uncles. For example, also demonstrating collective care beyond western nuclear family ideology, the Māori kinship term whaea usefully incorporates all women relatives of the same generation. For Māori, as Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere puts it, ‘One’s aunt in English becomes one’s mother.’ 3 The English term for auntly behaviour is materteral. Its Latin derivation from matertera (maternal aunt), which comes from mater (mother), captures a similar sense of gendered collective care as whaea. 4

With his concerns for child welfare and citizenship, James Hay was well aware of the power of avuncular and materteral figures in society. Beyond their real importance to whanau (family), Hay was part of the commercial and fictional creation of aunt and uncle characters similar to those that appeared in storybooks. Indeed, Hay himself appeared through the 1930s on the radio as ‘Uncle Hamish’. 5 At that time, capitalising on the positive, caring and trustworthy image that aunts and uncles could embody became widespread in business. In the United States, materteral figures such as the fictional Betty Crocker were invented by modern capitalists to sell their products. 6 In New Zealand, Aunt Daisy (Maude Basham) was a prominent radio personality who endorsed household products as well as constant positivity and helpful tips for the family. 7 The intention was that consumers feel a ‘familiar’ connection with these characters, thereby forming a strong bond with the businesses they endorsed and buying their products.

For all James Hay could present prizes to children who won colouring competitions and greet participants at international culture evenings, childcare was considered ‘women’s work’, requiring gendered skills of feminine caregiving. The genius of Hay was to combine welfare guardianship, childcare and citizenship-building with a fairy tale materteral figure. Hay invented the Aunt Haysl character, who, directed by him, could lure children to his roof far more effectively than he could. Along with the appearance of commercial materteral figures, Hay’s creation of Aunt Haysl was likely influenced by the appearance of children’s pages in the Star, the Sun and the Press in the 1920s. In particular, there was ‘Aunt Hilda’ at the Star, who had a long-running and successful ‘Starlets Club’ for children. 8 These media aunts were a toned-down version of the racy ‘agony aunts’ in modern newspapers and magazines that offered solutions for readers’ personal, and often embarrassing, problems.

James Hay’s aunt was cleverly named for the store ‘Hays’ and the ‘l’ was for the ‘leaguers’, the children’s troop of followers that Hay invented, likely inspired by the Starlets, and also in the footsteps of familiar contemporary groups that were part of a wider muscular Christianity movement, such as the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), Boy Scouts and Girl Guides. 9 It was reportedly Hay’s ‘dream in establishing this great family of boys and girls that they should carry out the ideals of brotherhood and community service’. 10 Historian Geoffrey Rice writes that ‘Together with the playground, the league was a brilliant marketing ploy.’ 11 Overseeing all aspects of the roof was Aunt Haysl, the jewel in the crown of Hay’s rooftop inventions.

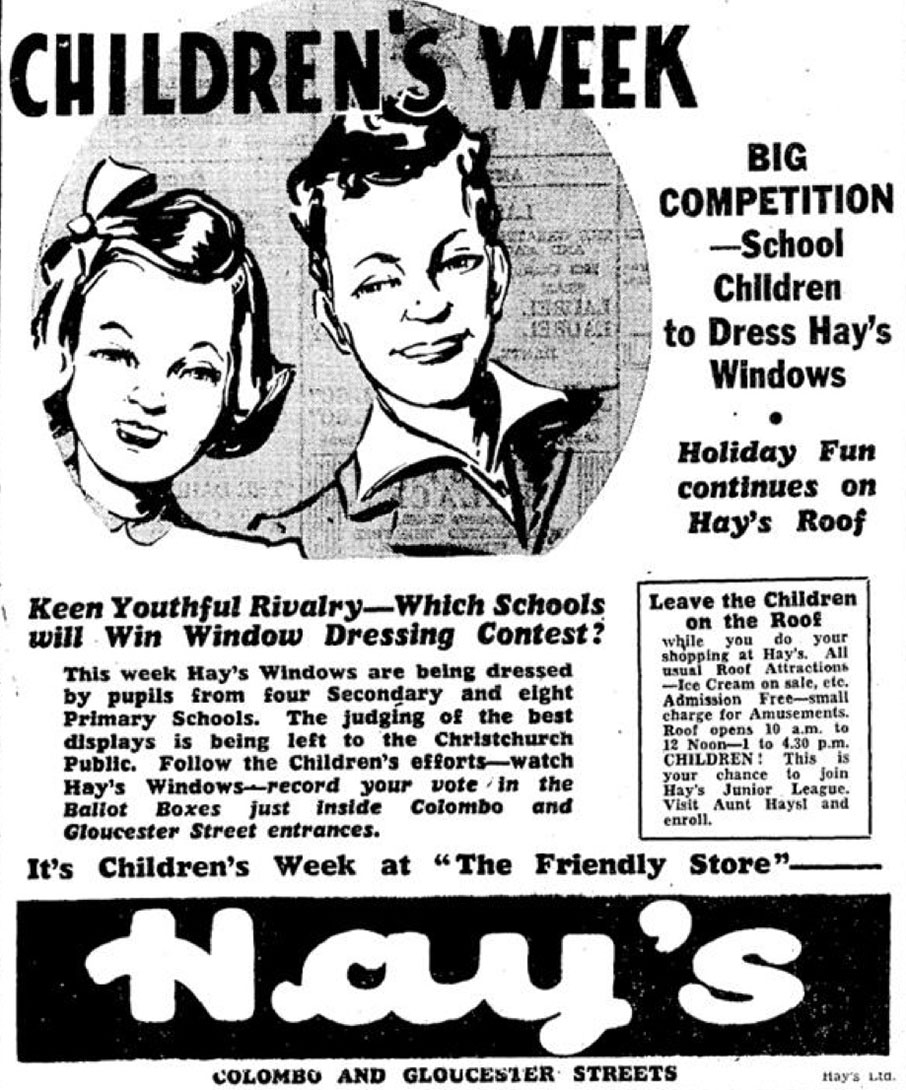

Advertisement in the Press encouraging parents to ‘leave the children on the Roof’ while they shopped in the store in 1943. (Press, 31 August 1943, p2)

Rooftops and Playgrounds

Accompanying the growth of large cities with ever-taller buildings, urban rooftop playgrounds were a global, modern, capitalist trend that appeared in the early twentieth century. A critical literature on playgrounds has overlooked these private commercial sites, instead earnestly focusing on public outdoor and recreational spaces designed by leading architects in Europe, North America and Japan. 12 Those playgrounds were built in response to a new concept of childhood as a distinct developmental phase and emphasised safe and educational play. 13 Focused on creating healthy, intelligent citizens, they featured sand pits, swings and slides.

Alternatively, this article turns to playgrounds in modern department stores. On the leading edge of urban growth, large private stores were ‘a self-contained one-stop shopping experience away from the dangers of the streets’. 14 They provided toilets, cafés and crèches to ensure that women customers could focus on lengthy shopping sprees. 15 In that context, playgrounds became part of the stores, encouraging both present and future shoppers. In addition to the child development goals of public playgrounds, these private spaces provided marvellous and exciting attractions in a similar vein to circuses and fairgrounds. Seeking to utilise their roof space in creative and alluring ways, they promoted play with the hope of developing children as lifelong consumers – an important theme though this article.

New Zealand’s first rooftop playground was opened in Auckland in 1922 by Farmers’ Trading Company. 16 General manager Robert Laidlaw had travelled to Chicago in 1915 and likely visited the iconic Marshall Field’s department store with its large children’s floor. Back in 1902, the store’s then manager, Harry Selfridge, had recognised the commercial benefits of developing children’s loyalty and had introduced a ‘Children’s Day.’ Selfridge went on to open a ground-breaking store in London where wonder and surprise were part of the shopping experience. Christchurch’s James Hay was acutely aware of global modern trends in department stores. Most directly, it is likely that he got his idea for Christchurch’s rooftop playground from Auckland. 17 By the time he opened his store in 1929, Hay’s winning point of difference was that he brought together a proven track record of experience in retail with voluntary and paid work in child, youth and wartime army recreation.

The Rooftop’s Pied Piper: James (Jim) Hay (1888-1971)

The Hay’s roof was the vision of store owner and manager James Hay, who was born in Lawrence, Otago, and left school at 13 to work in a drapery store. He moved to Milton, Ashburton and then Christchurch, where, in 1909, he joined the staff of the city’s premier department store, J. Ballantyne and Company. He later became advertising manager for another department store, J. Beath and Company.

Across his various spheres of work, the paternal James Hay was a welfare guardian figure with a longstanding concern for children and youth. A devout Presbyterian, Hay became president of its Bible Class Union movement. He was an elder of Knox Church for over 40 years and chaired a committee formed by the combined churches to raise funds for children’s homes for 18 years. Later in his career, in 1959 he formed the J.L. Hay Charitable Trust to assist children. 18

During World War One, Hay served overseas for the YMCA which, appreciating his organisational and good citizenship skills, appointed him secretary of the New Zealand Division in charge of providing recreational and welfare services to troops; he was made an MBE and then an OBE for his work. Hay married Christchurch-born New Zealand Army Nursing Service nurse Davidina Mertel Gunn in 1917 and after the war they moved to Wellington, where he worked as general secretary of the New Zealand YMCA. They returned to Christchurch in 1925, where Hay became advertising manager and staff controller at Ballantyne’s. The Hays had four children; two daughters and twin sons. 19 Visitors to the roof in the pre-World War Two years have memories of the twins working on the roof in the school holidays, ‘doing odd-jobs like supervising the merry go-round’. 20

Keen to embrace new retail developments, in 1929 Hay opened a new store in the unfashionable area north of Christchurch’s Square as an outlet for Auckland’s Macky, Logan, Caldwell. 21 From 1933 the store was Hay’s, and with the slogan ‘the friendly store’ became one of the South Island’s leading department stores. Not only did the store grow to absorb the block, but branches were established in Greymouth, Ashburton, Oamaru and Dunedin. Ever the retail innovator, in 1960 Hay’s opened Christchurch’s first suburban shopping mall at Upper Riccarton and in 1967 another, Northlands, at Papanui. 22

Geoffrey Rice describes Hay as ‘A man of great energy, initiative and imagination’ and with a reputation ‘for complete honesty and trustworthiness’. 23 Continuing his passion for civic service, Hay served on the Christchurch City Council between 1944 and 1953 and unsuccessfully ran for mayor (his son Hamish would later serve in that role for 15 years). In 1961, Hay was knighted for his services to the community. While officially retired, he remained president of Hay’s until his death in 1971. Passionate about history, Hay was an important supporter of Canterbury Museum. A longstanding patron of the arts, he was a key figure behind the new town hall, located across Victoria Square from his store, and its James Hay Theatre, the sight of many spectacular performances, was appropriately named in his honour. 24

Cultivating Workers and Customers

Importantly, James Hay’s passion for citizenship was all-encompassing. Honing knowledge and skills from his church activities and YMCA experience, making good citizens was at the core of all his actions, and could involve blending his work for church, home, work, city, nation and empire; in other words, in all aspects of his life, Hay ‘practiced what he preached’. In particular, his business interests advanced strong corporate paternalism: that is kinship and loyalty among workers who are cared for by a benevolent, fatherly employer. The pages of the Hay’s staff gazette contain examples of employee weddings, social club activities and sports such as marching and swimming. 25 There was a social and welfare committee, a staff ball, and football, cricket and baseball teams. It is remembered that ‘Mr Hay was renowned for his generosity he showered on his staff… A spirit of camaraderie was fostered by in-house social activities and sporting competitions against teams from other businesses.’ 26 Another recollection captures the notion of staff being valued and given a sense of being in a team. Jim and Moya Delore, who met while working at Hay’s, told journalist Dorothy Hunt that ‘Mr Hay showed a real interest in all the people working in the store’ and they both remembered social activities for the staff. 27 The flip side of corporate paternalism was that it was the norm to have ‘morals and good conduct constantly under scrutiny’ in an environment that encouraged social and cultural sameness. 28

Besides his workers, Hay was also dedicated to shaping his customers’ lives, with the intention of creating loyal lifetime and intergenerational customers. For example, in ‘the friendly store’, customer loyalty was fostered through a popular cash-discount stamp scheme. 29 Customers over 17 years of age joined a ‘Hay’s League’ club and collected redeemable League Discount Stamps for each 2/- they spent. 30 Started in 1930, the membership reached 42,000 by 1950. 31 Members were also offered deals on the occasion of the shop’s annual birthday celebration. Browsing through open shelves, rather than the pressure of asking an assistant for service, and low prices were also reported to be part of the Hay’s customer experience. James Hay and his workers employed marketing tactics at the forefront of global department stores. Geoffrey Rice notes the ‘innovative window displays and promotions’ and argues that ‘People came to expect the unusual at Hay’s, and were rarely disappointed.’ 32 In that vein, Hay started the annual Christmas Parade in 1948. 33 Capitalising on iconic mythical figure Father Christmas was a paramount way to cultivate the store’s festive branding and encourage spending on presents. Floats featuring storybook characters paraded from the railway station on Moorhouse Avenue to conveniently end up outside the Hay’s store. 34 The parade was a huge and longstanding success, outliving the store, and adapting with the times. 35

Hay’s Roof Memories 1929-1997

Visited by thousands during the years that it was open, there are many memories of the Hay’s roof and its playground features. The memories presented here are sourced from publications written across the years, as well as from an interview with a 1950s university student rooftop worker. A common theme in recollections is a nostalgic wonder and element of surprise that this was a ‘real’ place that is implanted in their memory. There is a strong sense of a shared collective memory that forms part of Christchurch’s cultural heritage.

In 1997, a 76-year-old man interviewed by the Press recalled that soon after the store opened there were ‘organised races and ball games’ for children on a bare roof. 36 Most memories, however, are of intriguing and spectacular fairground items. For example, at the store’s opening in December 1929 James Hay hired a tightrope walker dressed as Father Christmas, and in 1934 he had circus elephants parade past the store. 37 Magician Jack Boughen was asked to work there in 1935. In 1997, his granddaughter recalled ‘magic, Aladdin’s Cave, a slide and a merry go-round. There were monkeys for a while, but they were withdrawn when someone was bitten.’ 38 Over the decades there were many rides for children to enjoy. From the 1930s, there were a first generation of motorised ‘Scoota Boats’ that were driven around a specially built pool, a mini-rollercoaster and miniature train rides. Later there were electric space rides and sea horse rides, and even ambitious donkey rides. There was usually a small charge for the rides.

Miniature Railway, Hay’s Ltd roof 1950s. (Canterbury Museum, Hay’s Ltd collection)

The playground became a welcome rite of passage for generations of Christchurch’s children and an important source of nostalgia in future years. Interviewed about her childhood in 2013, Anne McCormack of New Brighton included going to the Hay’s roof, commenting that ‘They had a roof that was open in the holidays and it had all sorts of entertainment on it, little merry-go-rounds and that sort of thing.’ 39 Always on the lookout for the next attraction, James Hay had brought a carousel back from a 1947 trip to England. 40 There was also a popular large doll’s mansion. Another anonymous interviewee in a 1980s newspaper clipping commented that ‘For years I thought the Hay family actually lived in the store and that after hours the twins, David and Hamish, had the run of the roof and playground with its dolls house (my favourite) to themselves. I thought they must be the luckiest kids in the world.’ 41

Capturing the important connection between special occasions, holiday festivities and the roof, in the 1980s Nance Sepie recalled that the roof ‘always had special attractions for the school holidays, especially near Christmas, when Father Christmas sat in his grotto, which was always beautifully decorated’. After visiting him it was time to enjoy the roof, with its merry-go-rounds, distorting mirrors, aquariums, aviaries, lollies and ice-cream. Sepie remembered that the favourite ride was ‘the Switch-Back, a sort of mini-roller-coaster. We climbed up the stairs to a platform, sat in the “car” and held on tightly. Down we went at full speed, up, back, then slowly we came to a halt. Back up the stairs again for another go until the pennies ran out.’ 42

Another 2011 recollection by ‘Wendy’ was of ‘Trick mirrors, slides, a miniature train, a merry-go-round and holiday highlights such as waxworks, circuses and displays of animated mechanical animals or figurines were offered.’ 43 Crafted from the new material fibreglass, a sturdy giant fungus and two hardy fashionable dinosaur slides joined the roof after World War Two. The evolving rooftop attractions became etched in children’s memories, making such strong impressions that they remained into adulthood with ‘adults who now bring their children up to the roof, remember the good times they had as children and reminisce about the attractions that were there in their time’. 44 Hay’s goal of creating an enduring connection for life-long consumers was realised.

Historian and author Robyn Gosset recalls the merry-go-round, the switch-back, the sweet stall and the ride capsule experience with projected moving pictures on the walls that gave the experience of going on a journey. Gosset worked on the roof during the university holidays for three years from 1950. She remembers that workers were allowed a small cake of chocolate from the sweet stall. One of her jobs was to wrap small Christmas presents, such as a handkerchief, in preparation for sale and distribution down the shoot of a large model elephant’s trunk. One worker stood at the front of the elephant and called out the appropriate present for the awaiting child, such as ‘girl of eight’. Another worker out of sight behind the elephant then selected the present and sent it down the trunk so that, as if by magic, it appeared, making a wish come true. 45

Each summer holiday season the roof developed a new, alluring theme, such as ‘to the bottom of the sea’ and ‘up the heavens’. Gosset recalls preparing for an Alice in Wonderland ‘down the rabbit burrow’ theme where twenty-five rabbits were stuffed from the waist-up, to appear out of holes. The polio epidemic, however, closed the roof that season and the rabbits went unused. Gosset also visited the roof as a child and remembers a fawn being present as part of a Disney-inspired Bambi theme. 46 Rhesus monkeys were also part of a display when she worked there. 47

Edna Neville: The Fifth Aunt Haysl

James Hay’s creation ‘Aunt Haysl’ appeared on the roof as a kindly aunt who befriended children. Her leaguers had their own magazine in which they entered competitions and contributed stories, jokes, riddles, limericks and poems. 48 Aunt Haysl edited the magazine, which also featured her editorial, advertised city happenings and was distributed widely to schools, as well as on buses and at fairs. The league numbered an estimated 21,000 junior members in 1950. 49 One leaguer tells of the early activities on the Hay’s Roof, including the urban reinvention of ‘campfire culture’ that was part of contemporary youth movements:

The Aunt Haysl role was created as a person who could be a friend to the children and attract customers to the store. I just loved going up to the roof, it was such a magical place. Aunt Haysl was a role played by several women over the years, but the most famous was Edna Neville, who was the fifth Aunt Haysl. This was the one I knew, and who was in the role from 1944 to 1981. She was always friendly, would stop and chat to you and never seemed to tire of the attention from her fans. A huge fireplace was built on Hay’s Roof and children gathered there every Friday night to eat bread and saveloys and drink billy tea from water boiled on the fire. 50

In the 1980s Nance Sepie recalled that:

Tucked away in the corner of the roof was a small office where the door was always open. The walls were covered with paintings, cut-outs from magazines and comics, and in one corner, a desk piled high with papers. This was where Aunt Haysl lived, here was the hub of competition land… We were Hays Junior Leaguers. The Junior League was a small paper we collected from this office, then rushed home to colour-in the featured competition. Points were given and winning entries were put on display in the store. Points were also given for riddles, jokes and drawings! Aunt Haysl knew us all by name. Always friendly and interested in our school work and hobbies, she encouraged with her kindness. We loved going to see her in the little office on the roof. Time came for us to go to high school, and new friends and interests took over until we felt we were too old for the competitions and the younger children. But we never forgot Aunt Haysl… Sometimes I see her in town, and we still remember each other. Once she remarked to her companions that I was one of her Junior Leaguers from many years ago. Immediately I was back in the roof and could see the little office and hear the noise of the Switch-Back. Miss Edna Neville will always be Aunt Haysl to us. 51

The fifth Aunt Haysl realised all of James Hay’s hopes and more. What life story and characteristics equipped her to fulfil the role so successfully? Born in Christchurch in 1912 into a financially and emotionally difficult childhood, Edna Neville lived in the suburbs of Opawa and Hornby. 52 She also reportedly spent some of her ‘early years’ in New Brighton. 53 Her father was away at war, and then pursuing itinerant farming work. Neville recalled that ‘Money was not plentiful.’ She and her sister had one pair of shoes at a time and few clothes: ‘Once when I was eleven my father bought me a pink velvet suit and a picture hat and I was ecstatic. I’ve always loved picture hats and wore them in Hay’s Christmas Parades. Being given that outfit was a highlight in my childhood.’ 54

Neville wanted to be a journalist and while at Christchurch Technical School, along with book-keeping, typing, geography and history, took a journalism correspondence course. She successfully applied for holiday work in the new Hay’s store and subsequently gained permanent employment. She later reflected that she was a Presbyterian, a member of the Bible Class Union and that ‘Mr Hay wanted all his staff to be Presbyterians.’ Edna Neville had started an association with Hay’s that would last for the rest of her life. She recalled that ‘Once on the staff of Hay’s Ltd I began to live’ and that she felt a strong sense of belonging. According to a story she told recalling her life, that feeling was accentuated in 1940 when she was hit by a car when crossing the road. While in hospital for three weeks, her medical expenses were paid by Hay’s Ltd as an act of corporate paternalism. 55 With a strong sense of service, Neville trained as a Voluntary Aid Detachment worker during World War Two. She was also active in the Canterbury Repertory Theatre Society, and in 1944 performed for servicemen at Christchurch Public Hospital. 56 Speech and drama were lifelong pursuits for Neville. Thanked by the Canterbury Repertory Theatre Society for her wartime contribution, Neville went on to become a Life Member, ‘taking part in many plays and organising front of house volunteers’. 57

Always interested in working with children and after holding many different positions at Hay’s, Neville was offered a position as matron at St Saviour’s Orphanage in 1944. 58 Just as she accepted the job, the Aunt Haysl role became vacant. 59 Legend has it that having to choose between the positions was easy: ‘With Edna’s love of children and the opportunity to use her artistic talents and her vision of what could be done, the Roof won.’ 60 Inspired by James Hay, Neville was able to draw upon a potent mix of her skills in acting and journalism and her love of music and working with children, to set about providing rooftop education and amusement for children. For example, at the beginning of 1945 she formed a choir for Hay’s Junior Leaguers aged 12-16 years. Children were instructed to ‘report to Hay’s Roof before next Thursday’ where Aunt Haysl would give them the time for an audition. 61 A Hay’s League Junior Choir for younger children aged 7-13 years was also started, offering a hundred children the opportunity to sing at special events and with local artists. 62

Expanding her journalism skills, Neville enthusiastically edited the monthly Hay’s Junior Leaguer. As an educator, she created a free library with ‘two thousand books on a wide range of subjects’ that was available to ‘her children’. 63 As one ex-leaguer commented, ‘I always like to think I got my first writing break via Aunt Haysl. I had my first writing published when I was in primary school in the Hays Junior League magazine. I remember my excitement and pride in having my work published for all to see.’ 64 Robyn Gosset remembers winning a prize for her story on fossils at Curio Bay. Having her work published went towards encouraging her later career as a writer. She remembers Neville as absolutely devoted to the league, and as being available after school for children to drop in and visit. 65

Neville also developed her own writing, becoming a storyteller. Marina Warner has written that ‘Children are not likely to be committed to a certain way of thought; they can be moulded, and the stories they hear will then become the ones they expect.’ 66 Storytelling can serve as ‘a social binding agent’. 67 A book of fairy stories ‘imagined by “Aunt Haysl”’ contained ‘The Magic Watering Can’, ‘Penelope the Pansy’, ‘The Magic Pond’, ‘A Dream that Really Came True’, ‘Fairy Music’ and ‘The Rosebud Fairy.’ Following Warner’s arguments, such tales could offer ‘magical metamorphoses’ to those who heard or read them. 68 It was a related experience to that of the roof as an enchanting childcare space of excitement and wonder. Once again connecting to pragmatic welfare guardianship, James Hay wrote in the forward to the fairy tales book that the proceeds from sales would endow a ‘Leaguers’ bed’ at Christchurch Public Hospital. The plan was that children occupying that bed would be visited by Aunt Haysl or Junior Leaguer members. 69

Taking her materteral role seriously, Edna Neville studied psychology at the Workers’ Education Association. She also worked for Cholmondeley Children’s Home, Dr Barnados and the Save the Children Fund. 70 In tandem, she honed her performing skills by gaining an Associateship (ATCL) qualification in speech and drama. Contributing to her fame, from 1953 to 1966 her weekly 3ZB children’s radio session as Aunt Haysl was broadcast nationwide, drawing in a much wider audience than those who visited her on the roof. 71

Orientalism

From her rooftop office, Edna Neville pursued a global outreach. Fostering goodwill across differences, she developed an international penfriend service for her leaguers. 72 Blending her theatrical expertise with storybook fairy tales, she cultivated a form of benevolent orientalism that involved admiration and reverence for traditional world cultures. This work involved, as John M. MacKenzie has argued, orientalism as ‘a sympathetic concept’, whereby seeking better understanding, cultures considered diverse and exotic were studied. 73 For example, an international party on the roof saw participants piped in with an all-nations flag. Various national anthems were sung, there were different national dances and dolls in traditional costumes were on display. James Hay was there to greet and present scrolls to the participants. There was also ice cream and soft drinks for a treat. 74

From the early 1960s, Neville became particularly focused upon Japan. 75 She recalled that ‘My horizons were further widened by a trip to Japan as the New Zealand delegate to a peace conference with delegates from countries worldwide.’ 76 Her visits to schools included speaking as an authority on Japan. 77 Removed from politics, resting on orientalism’s aesthetic curiosity, it was Japan’s ‘traditional life’ that she promoted. Japanese culture was told as another mythical and exotic story. Significantly, Māori culture did not feature in the roof’s stories. Rather, the invention of fantasy and ‘elsewhereness’, akin to the Walt Disney Company, was strongly influenced by Anglo-American White Anglo-Saxon Protestant hegemony. 78 ‘Other’ cultures were welcomed so that they might be assimilated into dominant Christchurch society. 79

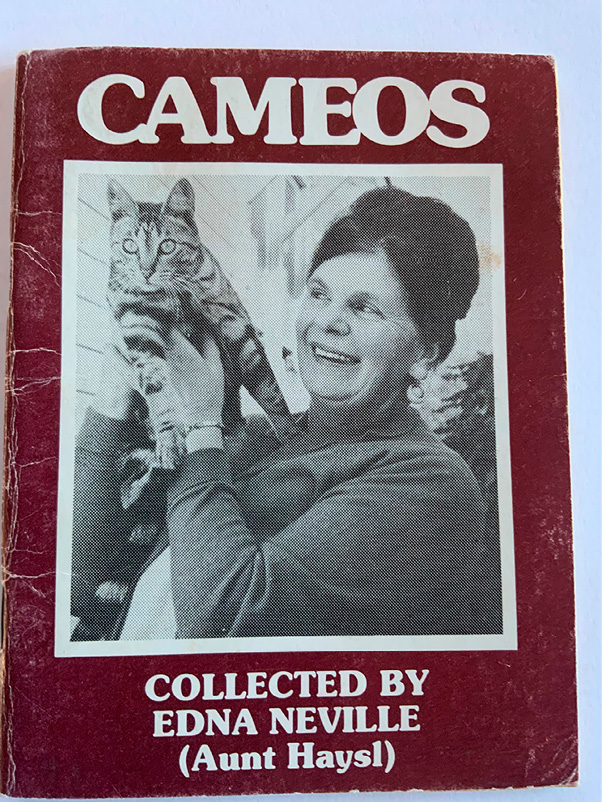

Academic Christine Tremewan has argued that ‘service to community’ was the ‘driving force’ behind Aunt Haysl. 80 Indeed, as the years passed this was increasingly the narrative surrounding her. In 1970 she was awarded the British Empire Medal for service to the community. 81 As put in the Christchurch Star in 1977, ‘She’s made thousands – and all of it for charity.’ 82 Neville also published a book of poetry, Fragments and Other Poems, and small books, Cameos, containing her inspirational sayings. As with the fairy tale book, proceeds from these publications went to charity. Described as ‘a store of potted wisdom’, her motto was ‘Give the world the best you have and the best will come back to you.’ 83

Cover of Cameos. Edna Neville was a cat lover. (Author’s collection)

Aunt Haysl the Public’s Storybook Character

Edna Neville was the lynchpin of the Hay’s roof, a vital part of its longevity. So successful was she at ‘method acting’, completely identifying with her job description, that Aunt Haysl and Edna Neville became blended together in the public’s imagination. For example, by 1950 it was commented in The Plainsman that ‘a dark-haired attractive young woman with a flair for coping with and entertaining and bringing out the best in children’ had 20,000 nieces and nephews. 84 An undated Hay’s Junior Leaguer magazine stated that:

The busy, bright-eyed, attractive, distracted young woman they call “Aunt Haysl” has two secret vices. She writes poetry, and she is passionately fond of playing marbles. We may as well admit these things right away because the rest of her is almost pure angel. 85

It wrote that the roof was as close to heaven as one can get and that Haysl ‘reigns supreme over a kingdom of 25,000 “nephews” and “nieces”’. 86 Indicatively, an anonymous clipping had the headline ‘SHE NEVER LEAVES HER JOB: EDNA NEVILLE.’ 87

Aunt Haysl enjoyed intergenerational appeal. On her 25th anniversary in the role, it was noted that ‘Many thousands of young people have passed through her hands from babes in arms to teenagers, and many now parents themselves, are bringing their children to see Aunt Haysl.’ 88 It was claimed that Aunt Haysl remembered them all. A 1969 article in the New Zealand Woman’s Weekly claimed there were 9000 leaguers and that children flocked to the roof in the school holidays to visit her. Beyond the roof, her varied work was reported as including judging baby shows, fancy dress contests, giving talks to schools and churches and organising charity affairs. Indeed, ‘Aunt Haysl Has Friends Everywhere’ and ‘In constantly thinking outwards beyond herself to other people and their needs, she has won contentment and happiness.’ 89

In 1981, a New Zealand Woman’s Weekly article with the headline ‘Her family is a city’s children’ implied that Aunt Haysl had the city’s children captivated. Edna Neville told author Felicity Price that she involved herself in charities that were mostly ‘associated with children either handicapped or in need of emotional or social assistance’. 90 Towards the end of her life, in an NZine story Dorothy Hunt wrote that ‘To go out in public anywhere with Edna is like being an escort on a celebrity’s walkabout. She is constantly being greeted with warm recognition by friends, former Leaguers and members of community organisations in which she has been involved.’ 91 In 1992, on her 80th birthday, the Repertory Sunday Club wrote in a special tribute that ‘HUNDREDS AND THOUSANDS OF PEOPLE in Christchurch and beyond will have sent loving wishes to this remarkable woman. Edna has done so much for people in Christchurch – always quietly and unselfishly – She is the kind of person who makes our Society rich.’ 92

The Christmas parade extended Aunt Haysl’s presence onto the streets and displayed her popularity and status as a storybook fairy godmother figure. In her own words, ‘Every year for Hay’s Christmas Parade which began in 1948 I wore a new dress and a picture hat. I had my own float and chose Leaguers to be dressed as fairies and accompany me.’ 93 The parade had started with floats portraying storybook characters such as Mother Goose, a practice that continued through the years, for example with about 600 people dressed that way in 1978. 94 Geoffrey Rice has commented that at the parade ‘Aunt Haysl and Father Christmas were always greeted with rousing cheers as they passed by.’ 95 Mary Rene remembers the Christmas parades and her excitement when the float with Aunt Haysl came by: ‘In her picture hat I thought she looked just like the Queen Mother.’ 96 Indeed, in the 1977 float she wore a yellow dress evocative of one worn by Queen Elizabeth II for her silver jubilee celebrations.

Aunt Haysl on Jubilee float wearing signature picture hat with junior leaguers in the Hay’s Christmas Parade 1977. (Christchurch City Libraries, ARCH812-15)

After 37 years in the job, in 1981 Edna Neville officially retired. The accolades poured in for the ‘surrogate aunt to thousands of Christchurch children’ who was leaving behind her ‘a 7000-strong “family” and a generation of goodwill seldom matched in the commercial field’. Neville planned on pursuing her hobbies of stamp collecting, pen friends, her love of cats and attending Altrusa, the Commonwealth Society, Travel Club and the Pan Pacific and South-east Asia Women’s Club. 97

Irreplaceable, and having become Aunt Haysl in the public’s eyes, and arguably her own, Neville took the character with her and continued to appear in the Christmas parade. So that she could continue her charitable work, mostly with children, the reformed store Farmers and Haywrights set up the Aunt Haysl Trust. The $10,000 donated by the company was matched by public subscription. 98 By 2001, Neville commented that $200,000 had been raised by the trust and distributed to voluntary organisations in Christchurch. 99 One of her last random acts of kindness was to invite guests to a ‘no reason party’. 100

Closure and Afterlife

Past its heyday, the rooftop limped on, surviving a number of ownership changes, staying open for almost 70 years and lasting until the building was demolished in 1997. 101 At the end of its days, the ‘Farmers Fantasy Run Roof’ in 1996 featured restored:

the old favourites, such as the green frog rubbish bins, mirrors, Dinosaur slides, Rochossaurus, and Theatrette with all the fairytales animations. Some of the new attractions are the New Santa’s Grotto, Beauty and the Beast, Fairyland, Santa Bear and Fantasy castle, Nativity and a 25 minute live ‘Santa Bear Christmas Show’ presented by Regency promotions. 102

The roof in January 1980. (Photograph by Gary Prescott, Christchurch City Libraries, DW-100591)

After the roof’s closure the attractions were split up, finding new owners and locations. In 1997, the Altrusa Edna Neville Playground opened at the Christchurch Women’s Hospital building. In a new lease of life ‘some of the equipment in the new playground comes from the now dismantled Hay’s roof children’s playground’. 103 Neville had been a charter member of the Altrusa club in 1966. 104 It built the new Edna Neville playground ‘to provide a place for children to play safely while their parents are either in hospital as patients or visiting’. 105

Staying in Farmers’ ownership, the giant fibreglass fungus moved to the entranceway of Christchurch’s Northlands shopping mall. With the idea that they would become part of the city’s heritage collection, the dinosaur slides and mirrors went to Ferrymead Heritage Park. However, after having his company transport the slides to the park for free, some time later businessman and Ferrymead board member Warner Mauger spotted the largest slide broken up and in ruins. Considering it an important part of the city’s history, he arranged for the slide to be restored and then shown-off to the public on the back of a truck at the Christmas Parade. He then offered the slide to the Christchurch City Council for use in one of its public playgrounds, but the offer was rejected on health and safety grounds. 106

In 2017, the slide was put up for sale. However, ironically, there was a large public outcry by those who in a ‘citizen’s arrest’ believed that the slide, and effectively the public history of the private Hay’s roof, belonged to the city. The sale was withdrawn. The slide currently belongs to Warner Mauger’s son, city councillor and newly elected mayor Phil Mauger, and is in the Harewood yard of the Mauger’s contracting business. 107 Interestingly, in 2017 it was commented that the slide would be a perfect addition to the new post-quake publicly owned cutting-edge Margaret Mahy playground. 108 That playground is named after another aunt who wrote many children’s stories, including fairy tales, namely the award winning author Margaret Mahy. Offering materteral magic without the consumption, Mahy dressed up and gathered generations of children around her in libraries and schools. Meanwhile, Te Pae, a new convention centre, now occupies the site of Hay’s department store. Despite its intention of attracting thousands of consumers, it has no provision for childcare.

Conclusion

The Hay’s roof is an important part of Christchurch’s cultural heritage. Part of a modern, private department store, customers and workers engaged with its themes of childcare, education, wonder and magic to create its public history. Shared rooftop experiences formed a basis for collective memory. The rooftop playground epitomised founder James Hay’s simultaneous desire to make citizens and profits. His creative leadership through his life combined entertainment, education, muscular Christianity, welfare and charitable work, especially for children. In his creation of Aunt Haysl, Hay was able to realise his pied piper intentions of drawing generations of children to the roof. Appropriately talented, Edna Neville became the storyteller Aunt Haysl, harnessing the gendered power of aunts, presiding over a troop of children and showcasing alluring playground attractions. The Hay’s roof formed as a site of ‘materteral consumption magic’, its interwoven discourses combining to create a popular and long-lastingly wondrous space that is etched into an enduring collective memory.

Acknowledgements

I wish to especially thank Fiona McKergow, and Christchurch City Libraries, Canterbury Museum, Farmers Trading Company, Te Apārangi Royal Society James Cook Fellowship, Phoebe Fordyce, Robyn Gosset, Sarah Johnston, Melissa Kerdemelidis, David Littlewood, Brittany Mauger, Geraldine Pickles, Emily Rosevear, Geoff Watson, audiences at Tūranga and Canterbury Historical Association, and the anonymous reviewers for their appreciated assistance.

Endnotes

1 Donna Haraway, ‘Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City 1908-1936’, in Social Text, vol 11, 1984-5, pp20-64; Huw Halstead, ‘Everyday Public History’, in History: The Journal of the Historical Association, vol 107, no 375, 2022, pp235-248.

2 Veronica Strong-Boag, ‘Sisters Doing for Themselves, or Not: Aunts and Caregiving in Canada’, in Journal for Comparative Family Studies, vol 40, no 5, 2009, p802.

3 Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere, ‘To Us the Dreamers are Important’, in Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel (eds), Mana Wahine Reader: A Collection of Writings, vol 1, 1897-1988, Te Kotahi Research Institute, Hamilton, 2019, p6.

4 Aunt comes from the French tante, in turn derived from the Latin amita (paternal aunt), while amma is Greek for mother.

5 Rice, G.W. 2000, Hay, James Lawrence (Online). Available: https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/5h11/hay-james-lawrence (Accessed 25 May 2022).

6 See Susan Marks, Finding Betty Crocker: The Secret Life of America’s First Lady of Food, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2007.

7 A.S. Fry, The Aunt Daisy Story, A.H. and A.W. Reed, Wellington, 1957.

8 Christine Tremewan, ‘Something for the Children’, in Canterbury Women Since 1893, Regional Women’s Decade Committee, Christchurch, 1979, pp120-29.

9 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, Volume 14, May 1997, p1, Christchurch City Libraries (CCL).

10 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/5, ‘The Woman They Call AUNT HAYSL,’ Hay’s Junior Leaguer, undated fragment, CCL.

11 Geoffrey Rice, Victoria Square: Cradle of Christchurch, Canterbury University Press, Christchurch, 2014, p214.

12 See Joe L. Frost, A History of Children’s Play and Play Environments: Toward a Contemporary Child-Saving Movement, Routledge, London and New York, 2009.

13 See Marta Gutman and Ning de Coninck-Smith (eds), Designing Modern Childhoods: History, Space and the Material Culture of Children, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 2008, pp 3-4. On the development of voluntary and state play in New Zealand, see Helen May, Politics in the Playground: The World of Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand, revised edition, Otago University Press, Dunedin, 2019.

14 Katie Pickles, ‘Workers and Workplaces’, in John Cookson and Graeme Dunstall (eds) Southern Capital: Christchurch: Towards a City Biography, Canterbury University Press, Christchurch, 2000, p158.

15 See Susan Porter Benson, Counter Cultures: Sales Women, Managers and Customers in American Department Stores, 1890-1940, University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 1986.

16 Helen B. Laurenson, Going Up, Going Down: The Rise and Fall of the Department Store, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2005, p86.

17 ibid, pp88-90.

18 Rice, ‘Hay, James Lawrence’.

19 ibid.

20 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/2, Miscellaneous, the Press, 17 April 1997, CCL.

21 See Pickles, ‘Workers and Workplaces’, p158 on the hierarchy of Christchurch’s department stores. Ballantyne’s was at the top, Armstong’s and Miller’s were for working people, DIC and Beath’s were established stores in the middle. Hay’s was a newer store trying to be different, but also in the middle.

22 Pickles, ‘Workers and Workplaces’, p159.

23 Rice, Victoria Square, p212.

24 Rice, ‘Hay, James Lawrence’.

25 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/3, Hay’s Staff Gazette, covers and fragments, 1948-1969, CCL.

26 Wendy, 2011, Hay’s – The Friendly Store Where Everything is Different (Online). Available: https://lostchristchurch.wordpress.com/2011/08/05/hays-building-oxford-terrace-c-1959/ (Assessed 25 May 2022).

27 Hunt, D. 2001, The Friendly Aunt at the Friendly Store (Online). Available: http://christchurch-cheap.nzld.com/aunt_haysl.html.NZine (Accessed 25 May 2022).

28 Pickles, ‘Workers and Workplaces’, p157.

29 Rice, ‘Hay, James Lawrence’.

30 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/5, Hay’s Junior Leaguer, no dates and parts only, anon page, CCL.

31 Wendy, op cit.

32 Rice, ‘Hay, James Lawrence’.

33 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/2, 19 April 1997, the Press, CCL. Sir Hamish says his Dad was the first to hold the Christmas Parades.

34 Rice, Victoria Square, p239.

35 After the 2010-11 Canterbury Earthquakes, the inner city was closed and the parade moved to Riccarton Road in the west. In 2022, the 75th anniversary year, there were plans for an indoor $15 per person event at Christchurch Arena. Press, 17 June 2022, pp2-3. After opposition, they were abandoned in favour of a free event at the city’s showgrounds.

36 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/2, Miscellaneous, 18 April 1997, the Press, CCL.

37 Rice, Victoria Square, p204.

38 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/2, 19 April 1997, the Press, CCL.

39 Alison Parr with Rosemary Baird, Remembering Christchurch: Voices from Decades Past, Penguin, Auckland, 2015, pp234-245, p239.

40 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, Christchurch North News, 30 November 1996, p3, CCL.

41 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, Peter McLauchlan, ‘Aunt Haysl and the Hays Junior Leaguers,’ Canterbury Sketchbook, CCL.

42 ibid.

43 Wendy, op cit.

44 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, ‘Farmers Fantasy Fun Roof’, Christchurch North News, 30 November 1996, p3, CCL.

45 Pers com Robyn Gosset, 4 September 2022.

46 Disney’s Bambi film was released in 1942.

47 Pers com Robyn Gosset, 4 September 2022.

48 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, ‘Farmers Fantasy Fun Roof’, Christchurch North News, 30 November 1996, p3, CCL.

49 Wendy, op cit.

50 ibid.

51 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, Peter McLauchlan, ‘Aunt Haysl and the Hays Junior Leaguers,’ Canterbury Sketchbook, CCL.

52 Hunt, op cit.

53 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, The Pegasus Post, 25 January 1978, p1, CCL.

54 Hunt, op cit.

55 Hunt, op cit.

56 Press, 13 January 1944, p2.

57 Press, 6 December 1945, p2; Hunt op cit.

58 Hunt op cit.

59 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, ‘People Helping People’, Presbyterian Support, December 1999, p2, CCL.

60 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/2, The CWH Playground, A booklet by Altrusa, CCL.

61 Press, 29 January 1945, p2.

62 Hunt, op cit.

63 Hunt, op cit.

64 Purpleulz, 2012, A Wonderland on a City Roof (Online). Available: https://cclblog.wordpress.com/2012/10/13/a-wonderland-on-a-city-roof/ (Accessed 25 May 2022).

65 Pers com Robyn Gosset, 4 September 2022.

66 Marina Warner, From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and their Tellers, Chatto and Windus, London, 1994, p410.

67 ibid, p414.

68 ibid, p418.

69 Fairy Stories, imagined by ‘Aunt Haysl,’ Bascands Ltd, Christchurch, no date or page numbers.

70 Children from Christchurch’s orphanages were brought along to experience the roof. Pers com Robyn Gosset, 4 September 2022.

71 Tremewan, op cit, p124.

72 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, New Zealand Woman’s Weekly, 10 June 1963, CCL.

73 John M. MacKenzie, Orientalism: History, Theory and the Arts, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2011, ppxii, 215.

74 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/2, miscellaneous document, CCL.

75 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, 13 Sept 1962, anon article, CCL.

76 Hunt, op cit.

77 Tremewan, op cit, p124.

78 On the concept of ‘elsewhereness’, see Katie Pickles ‘Southern Outreach: New Zealand Claims Antarctica from the “Heroic Era” to the Twenty-First Century’, in Katie Pickles and Catharine Coleborne (eds), New Zealand’s Empire, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2015, pp229-244.

79 On Christchurch’s hegemonic colonial past, see Katie Pickles, Christchurch Ruptures, Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, 2016.

80 Tremewan, op cit, p124.

81 Hunt, op cit. The investiture was conducted in Wellington by Queen Elizabeth II, on Friday 13 March 1970.

82 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, Brice Scott, ‘She’s Made Thousands – and All of it for Charity’, Christchurch Star, 3 February 1977, p9, CCL.

83 ibid; Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, ‘25 YEARS AS AUNT HAYSL’, undated clipping, CCL.

84 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, 1 August 1950, The Plainsman, p17, CCL.

85 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/5, ‘The Woman They Call AUNT HAYSL,’ Hay’s Junior Leaguer, undated and parts only, CCL.

86 ibid.

87 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, anonymous clipping, CCL.

88 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, ‘25 YEARS AS AUNT HAYSL’, undated clipping, CCL.

89 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, Marie Mihajlovic, 30 June 1969, New Zealand Woman’s Weekly, pp7-10, CCL.

90 Felicity Price, ‘Her “Family” us a City’s Children’, New Zealand Woman’s Weekly, 6 April 1981, pp36-7.

91 Hunt, op cit.

92 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/1, undated document, CCL.

93 Hunt, op cit.

94 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, ‘UP TO THOUSANDS EXPECTED AT CHRISTMAS PAGEANT’, Press, 15 November 1978, CCL.

95 Rice, Victoria Square, p212.

96 Hunt, op cit.

97 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, Claire Bennett, ‘Reign of Goodwill Ends for Aunt Haysl’, the Star, 26 February 1981, p20, CCL.

98 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, ‘Funds to Help Children’, 1980, anon clipping, CCL.

99 Hunt, op cit.

100 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/1, undated invitation and guest list, CCL.

101 Rice, Victoria Square, p239.

102 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755/4, ‘Farmers Fantasy Fun Roof’, Christchurch North News, 30 November 1996, p3, CCL.

103 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755, clipping from Christchurch Star, Friday 14 November 1997, CCL.

104 Aunt Haysl Papers, 755, Christchurch Star, Friday 14 November 1997, loose clipping, CCL.

105 Hunt, op cit.

106 Walker-Pearce, F. 2017, History of Famous North New Brighton Family Documented (Online). Available: https://issuu.com/the.star/docs/117017pp/5 (Accessed 14 June 2022); Paul Corliss, Mauger Milestones: The Legacy of a North Brighton Family, Purple Grouse Press, Christchurch, pp377-79.

107 Pers com Brittany Mauger, 14 June 2022.

108 Flynn, L. 2016, Iconic Dinosaur Slide Pulled from Auction (Online). Available: https://www.stuff.co.nz/the-press/news/81368384/iconic-dinosaur-slide-pulled-from-auction (Accessed 14 June 2022).