Public History Review

Vol. 29, 2022

ARTICLES (PEER REVIEWED)

Channelling a Haunting: Deconstructing Settler Memory and Forgetting about New Zealand History at National Institutions

Liana MacDonald1,*, Kim Bellas2, Emma Gardenier2, Adrienne J. Green2

1 Ngāti Kuia, Rangitāne o Wairau, Ngāti Koata

2 New Zealand Pākehā

Corresponding author: Liana MacDonald, liana.macdonald@vuw.ac.nz

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v29i0.8218

Article History: Received 04/06/2022; Accepted 08/11/2022; Published 06/12/2022

Introduction

The Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories curriculum is a landmark document through which national history must be taught to all year 1-10 students. 1 The new curriculum is significant for a country that prides itself on a treaty partnership that purports to equally include Māori and Pākehā interests in government institutions. 2 Yet it fails to deliver equitable social outcomes for Indigenous peoples in, for example, health, youth suicide and incarceration, as well as education. 3 The content of the new curriculum presents an opportunity to get to grips with our nation’s history warts and all. There are hopes it will provide a more meaningful pathway towards reconciliation between Pākehā and Māori, and ways to build a society that is more in line with the intent of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, New Zealand’s founding document. 4

Like Te Tiriti, the New Zealand Wars were crucial in determining the course and direction of New Zealand, but there is limited public understanding of these histories. 5 Teachers perceive that New Zealand’s difficult histories are too controversial for the classroom and that students do not find them interesting. 6 The new curriculum means that challenging topics like the New Zealand Wars must now be engaged with by all teachers. However, Michael Harcourt’s research finds that the small number of teachers who have taught histories of colonial violence struggle to articulate practical measures that make the past relevant and tangible to students in the present. 7 There is an urgent need for innovative pedagogical approaches that engage with key curriculum understandings like colonisation, settlement and power to make the ongoing structuring force of colonisation visible.

In this article, we present a model for challenging how power relations between settler and Indigenous groups are constructed at national institutions. Drawing on Avery Gordon’s sociological work on hauntings, channelling a haunting is a teaching approach that makes absent, silenced, and unresolved histories of colonial violence and Indigenous oppression known and felt in the present. 8 Making past episodes of colonial violence relevant today supports school students to question how the public spaces and places they move through reinforce a view of national history that aligns with settler sensibilities. National museums traditionally play an important role in reflecting and determining how people view themselves in relation to the nation state. 9 Deconstructing settler memory and forgetting about New Zealand history at national museums through challenging a haunting is an intellectual and embodied process that recognises how lovely and difficult knowledge about colonial history frames popular perceptions of national identity.

In 2021, the authors of this article undertook a seven-week project as part of a secondary school teaching qualification that examined how three New Zealand institutions conveyed national narratives of history that are implicated in colonial power relations. AJ, Emma and Kim were studying to be secondary school history subject teachers and Liana was one of their history lecturers. This paper recounts the teaching and learning journey that they undertook to channel a haunting. We start by considering the nature of resistance to engaging difficult knowledge in settler societies. The second section relays the classroom process we undertook to critique how settler memory and forgetting is constructed at national institutions. The third section focuses on the experience of channelling a haunting at two national institutions: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa. We finish by discussing the implications of the museum visits and how channelling a haunting compels action; a something to be done that motivates us to meaningfully rectify the false truth claims of settler memory in society. 10

Resisting Difficult Knowledge in Settler Societies

Difficult knowledge is a term that is generally attributed to American psychoanalyst Deborah Britzman, who distinguishes learning about and learning from difficult knowledge by explaining that the latter requires introspective reflection about how one is attached to and implicated in the construction of information. 11 However, learning from difficult knowledge about the past is not easy, because it induces a sense of shame, discomfort or anger. 12 Scholars grappling with the teaching of difficult histories theorise the nature of resistance to difficult knowledge to propose ways of working through difficult emotions and trauma productively to effect societal change.

For Britzman, resistance to difficult knowledge is a ‘psychic event’ in which an individual ‘vacillates, sometimes violently and sometimes passively, sometimes imperceptibly and sometimes shockingly, between resistance as symptom and the working through of resistance’. 13 The view that resistance to difficult knowledge is primarily an internal battle is extended by Michalinos Zembylas, who considers how interrelations between discursive practices, the human body, historically situated emotions and affects, and social and cultural forces, have an impact how difficult knowledge is negotiated by learners and teachers. 14 Joanna Kidman progresses an understanding of resistance to difficult knowledge further by showing how it is implicated in nationalist discourse. The Signs of a Nation exhibition at New Zealand’s national museum, Te Papa, presents the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi as a birth of a nation story that:

allows Pākehā citizens to imagine themselves as partners with Māori in the nation-making quest. In this sense, it exists within nationalist discourse as a form of ‘lovely’ knowledge that permits people to visualize their role within the nation’s story as benign, altruistic and at times, even heroic. 15

Kidman’s racially nuanced exhibition analysis reveals ways that settler institutions construct narratives of colonial history that appeal to settler sensibilities by excluding and silencing colonial violence.

More recently, the role of affect has been theorised in relation to how exhibits can produce material and embodied pedagogies that influence how knowledge is negotiated by school visitors in museum settings. 16 That knowledge emerges through a relationship between the body and the environment has been central to Indigenous thought and ontology for centuries, whereby affect is not theoretical and the interconnectivity of all things is real. In Australia, knowledge lives in country, and is generated through patterns of relationship to country, and paying attention to bodily responses produced through senses and emotions can be pedagogical. 17 Scholars from New Zealand similarly map how Māori have a feeling for place in which knowledge emerges through interacting with local environments. 18 Indeed, Carl Mika writes that acknowledging the multifarious and complex nature of relationships between the body and objects or things means that one never fully realises all the ways our environment contributes to conscious thought. 19 Māori are tied to the whenua (land) and all spiritual and physical phenomena through whakapapa, an ontology that privileges layers of intergenerational knowledge and relationships. Whakapapa encompasses difficult knowledge, yet cognitive perception of relationships and connections to the past and to places, events and people may be severed by human design. 20

A sense of connectedness and belonging to the whenua can be as important to settlers as it is for Indigenous people. 21 These senses can be tied to a sense of nationhood or regionalism within the New Zealand psyche. 22 Settlers must create a sense of belonging that is on par with Indigenous groups to legitimise the right to stay and feel at home in the post-migration homeland. 23 In doing so, difficult knowledge about the nature of settlement – that is, the violent and brutal ways that the colonial invaders occupied tribal lands and established political, cultural, economic and social systems to sustain the subjugation of Indigenous people – must be forgotten or, at least, be easily overlooked. 24 Julia Rose writes that ‘difficult knowledge includes difficult histories and other knowledge that is upsetting, stressful, or too hard to bear’. 25 Therefore, difficult knowledge in settler societies can also be interpreted as modern-day mechanisms of power and control that legitimise a settler presence on stolen Indigenous territories.

MacDonald and Kidman, drawing from the philosophy of Jacques Derrida, argue that a settler colonial crypt is a way of understanding the repression of traumatic knowledge associated with the colonial invasion and death of Māori during the New Zealand Wars. 26 Iwi memories of colonial violence are supressed to cultivate a relationship to place that ‘reinforces a social and bodily orientation that aligns with the emotional and affective need for settlers to feel a sense of belonging to the whenua’. 27 National institutions are places where the settler colonial crypt operates through exhibitions that forefront lovely knowledge and withhold aspects of difficult knowledge. Settler memory and forgetting can be advanced through the way the environment is designed (physical spaces), narratives of history and contemporary race relations (ontological spaces) and attachments to the setting and a sense of national identity (emotional and affective spaces).

In this article, we contend that channelling a haunting provides students with tools for deconstructing multiple spaces that uphold the settler colonial crypt. Gordon argues that a haunting is when unresolved colonial violence comes into view, involving ‘instances when home becomes unfamiliar, when your bearings on the world lose direction’. 28 Students can learn how mundane public places and spaces are not culturally neutral and are biased towards settler perspectives. It is the process of teaching students how to channel a haunting we turn to next.

Learning How to Channel a Haunting

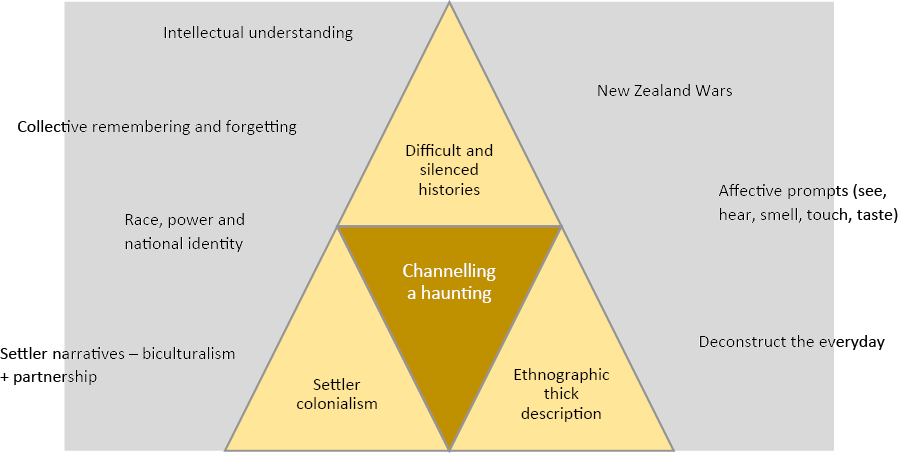

The ability to deconstruct settler memory in national institutions is based on letting oneself think and feel as though colonial violence has not between resolved and still matters today. The memory and ongoing legacy of historical colonial violence is still felt strongly by many Māori people and communities who were invaded by the British between 1843 and 1872. Perceiving that difficult histories of unresolved violence have a presence despite their absence is key to channelling a haunting. Indeed, ‘haunting recognition is a special way of knowing what has happened or is happening’. 29 There are three key cornerstones to learning how to channel a haunting, to deconstruct the false truth claims of settler memory in national institutions, as the diagram below demonstrates.

Late in 2021, the authors of this paper undertook a seven-week unit that focussed on how secondary school history students could be taught to consider the ways in which settler colonial power relations are constructed in national institutions. AJ, Emma and Kim were under 25 years old and were studying to be secondary school history subject teachers as part of a one-year Master of Teaching and Learning qualification. They were placed in a school approximately two days a week, while another two days were spent at university in courses focussed on teaching theory and pedagogy. Prior to the unit, the student teachers had designed and taught lessons and units of work with their classes about colonial conflict and used Vincent O’Malley’s work about the New Zealand Wars, in particular the Wairau Affray and the Waikato Wars. 30

The first cornerstone to teaching the process of channelling a haunting is a broad intellectual understanding of difficult and silenced histories involving Indigenous oppression. This is a necessary step towards being able to critique the narrative gaps and silences about national history presented at museums.

The second cornerstone in the process is an awareness of the key tenets of settler colonialism and how collective memory can uphold settler power and privilege in society. In the four weeks leading up to their three field trips, the student teachers read literature about mechanisms of settler domination, historical amnesia, silencing and biculturalism, and settler/Pākehā identity. 31 Work by Indigenous and Black scholars was prioritised because non-white bodies are more in tune with the ways that settler societies structure unequal and racialised power relations. 32 The readings relayed several insights about the mechanisms of settler colonial power, including:

• settlers are here to stay, so Indigenous peoples must be displaced

• settlers develop a strong attachment and sense of belonging to the adopted home

• historical amnesia erases how territories were violently taken from Indigenous peoples

• framing settler-Indigenous relations as an equitable and harmonious partnership legitimises a settler presence.

To ground the relationship between settler colonialism, national identity and cultural forgetting in a museum context, the student teachers read Kidman’s paper to examine how lovely knowledge is constructed in the Signs of a Nation exhibition. They noted that the layout of the exhibition reinforced a bifurcated, ‘two worlds’ view of Māori and Pākehā people, in which Māori are presented as aligning with the natural world, while Pākehā are ‘in tune with urban and built environments’. Other features of the physical space, like the talking posts scattered at the front of the exhibition and the ‘high cathedral-like ceiling... comfortable seating and calm ambience’, were discussed in relation to the holiness and sanctity of New Zealand’s birth of a bicultural nation narrative. 33 The article analysis process we undertook emphasised how exhibitions can produce narratives of colonial history that are steeped in power relations. With more time, we might have engaged in a more nuanced analysis that considers the degree to which historians – both Māori and Pākehā – are involved in the creation of the exhibitions relative to other experts, such as architects, conservators, designers and educators.

The third cornerstone for channelling a haunting is the ability to read and feel how settler memory is constructed in physical spaces and connected to emotion and affect. Leading up to the field trips, Emma, Kim and AJ engaged deeply in ethnographic thick description and the process of recording highly detailed accounts of experiences in the field. Liana showed the students her own field notes taken at sites associated with the 1846 Battle of Boulcott Farm. 34 The student teachers looked closely at how numerous elements, including objects, visible and missing text, layout and presentation of buildings and space, and visitors interact with each other at the Boulcott’s Farm memorial and Boulcott’s Farm Heritage Golf Club to reinforce settler memory of historical events.

The key cornerstones of Channelling a haunting. (Liana MacDonald)

After four weeks engaging with the three cornerstones through course-based university work, Kim, Liana, AJ and Emma visited exhibitions housed in three national institutions: Te Papa, the National Library and Pukeahu National War Memorial during the remaining three weeks of the unit. 35 Students were asked to compile field notes during their visits using a simple T-Chart where they recorded affective prompts (what they can see, hear, touch, smell, taste) and insights about layout, objects, text, space, people, buildings, etc, down the left-hand side of a field notes template, and some musings about how the affective prompts connected to settler memory of colonial history down the right-hand side. Due to ethical considerations, the student teachers were interviewed separately after the history course had ended and months after the visits took place. The field notes they had taken during the site visits helped to prompt their thinking, and their interview responses have been anonymised.

Deconstructing Lovely Knowledge at Te Papa

The first national institution that the authors visited was Te Papa. Many of the objects within Signs of a Nation, which was installed in 1998, and the layout of the surrounding exhibitions were discussed in relation to Kidman’s idea of lovely knowledge. For example, it was noted that the size and the wording of the three articles on the English and te reo Māori versions of the treaty replicas were equal sizes, to suggest they are of equal importance in society.

Legally we prioritize the Te Reo wording, but then in society we prioritize the English wording. We followed the articles and terms in the English version of the Treaty, and now society today is trying to transition to the Te Reo Māori version of the Treaty. But [the equal size of the wording] in both documents really impresses the idea that it’s always been an equal partnership. [Visitors] may be encouraged to sit there and think that both versions have been prioritized in history when that’s not the case.

The capacity for the objects in the exhibition to impress a harmonious and fair-minded view of colonial history on visitors was enhanced by ‘airport seats’ that encouraged them to:

Sort of sit down, look up and soak up the Treaty and the bicultural national myth. It sort of makes you feel really good about New Zealand history, as opposed to thinking about the contested nature of it.

View of Signs of a Nation with Treaty of Waitangi reproduced at centre, Te Papa, 2015. (Photograph by Norm Heke. Te Papa (75177))

Lovely knowledge about New Zealand’s colonial history was further enhanced by the layout of the Signs of a Nation exhibition and how it directed visitors through a narrative of national identity that emphasised the progressive nature of Aotearoa’s race relations.

You walk under the Treaty, then come out and see this huge Union Jack flag that is a replica of one belonging to Busby or Hobson or something, then to a small Rātana exhibit squashed at the back. You look at all the artifacts that are underneath, and then you meet a curved or an angled window that has a big view of the city and Waitangi Park. So you’re directed to think, ‘Oh, that’s right, we’re in the Commonwealth’ and ‘Oh, look, here it is the beautiful bicultural country with Waitangi Park’. So the museum is using Oriental Bay, you know, a very affluent gentrified area that is white and very wealthy, as part of the exhibition. People in this part of Wellington are arguably some of the most insulated and live in a white liberal bubble so that view when you come out is interesting.

Looking beyond Signs of a Nation and moving through and around the adjacent ‘Level 4’ exhibitions at Te Papa encouraged the student teachers to critically examine the presentation of Māori culture and identities. Next to Signs of a Nation is an exhibition about European migration. The objects, images, layout and text were organised in ways that homogenised Māori people and affectively pulled visitor bodies towards an impression that European migration was a positive event.

There’s a detailed breakdown of recent migration to New Zealand, but I didn’t get any distinction of different iwi or that Māori came to New Zealand on different waka. [The exhibition] made it clear that not all refugees are the same, but there was none of that for Māori. They sort of connected the refugees to historic migration and the colonial ships used to settle New Zealand but it’s not really the same thing. Refugees fleeing persecution, and particularly refugees of colour, are not benefiting from the colonial system... The way it’s presented makes Pākehā walking through go, ‘Oh we’re just getting more and more diverse. Oh, this is great! We started this whole migration of different peoples to New Zealand.’

The student teachers also observed a lack of recognition of difficult histories on Level 4. Sitting on one side of the Signs of a Nation is an exhibition about settler/tauiwi (non-Māori) migration, and on the other side is an exhibition about a North Island East Coast iwi. The layout and exhibition content does not convey the ‘recognition of any kind of disagreement’ between Māori and Pākehā in history.

How do Māori and Pakeha come together? How does that relationship actually work in practice? [The exhibitions] were very separate. There’s no coming together and I suppose because then that way, they would have to focus on things like the New Zealand Wars. And so it’s easier to tell these separate histories and have the Treaty as the joining sector than focusing on the reality of it. Yeah, that’s a bit of a deviation.

Moreover, moving through the exhibitions and focussing intently on the interplay of objects, sounds, and layout contributed to a disjointed and ‘disorientating’ narrative of colonial history. One student teacher felt ‘baffled’ when moving from the front to the back parts of Signs of a Nation by a significant narrative jump between events in New Zealand history.

I think it’s awesome that Rātana is featured, because it’s something that I don’t know a lot about, and I don’t know if many people probably would. But it just, I found it really interesting why they chose Rātana and chose to exclude everything else in that small section, then I became instantly disorientated. It’s kind of the end of Rātana, but I had no idea where to go from there because there was this lack of flow. And the whole time I was walking through, I just heard what sounded like a British marching brass band. So I just come out of Rātana, which I thought was meant to be a Māori movement, but I’m left with this lingering sound of something that sounds very British, which I thought was really interesting. I went back to see where it was coming from. And I think it was like a Rātana band. But the sensory experience was just a bit different from what I was reading. 36

Lars Frers writes that ‘the concept of absence is often brought into play when borderline situations and experiences are analysed, when the uncanny growls in the dark corners of regulated and orderly places and social settings’. 37 The narrative jump and juxtaposition of the treaty signing next to a religious and political movement that was critical of the Crown and government made the student teacher feel out of place. This experience evoked an embodied response that was triggered by an understanding that these two disparate events and groups cannot easily sit beside each other. By channelling a haunting, the student teachers could bring their intellectual knowledge about New Zealand history alongside the affective prompts assailing their bodies. This led them to question how settler memory of a benign and harmonious bicultural partnership is built into the construction of an exhibition, directing visitors to think and feel a certain way.

Deconstructing Difficult Knowledge at He Tohu

He Tohu is significantly smaller in size and scope than Te Papa’s Level 4, yet it elicited a similar critique from the student teachers. As it opened more recently, in 2017, the student teachers thought that the exhibition would present updated perspectives and be ‘more impartial… as opposed to Te Papa which is kind of getting a bit naff’.

Unlike Te Papa, He Tohu does engage visitors with difficult knowledge about New Zealand history. The centrepiece of the exhibition is a specially built document room shaped like a waka huia, a Māori wooden treasure box, that preserves He Whakaputanga Declaration of Independence (1835), several original versions of Te Tiriti o Waitangi (1840) and the Women’s Suffrage Petition (1893) documents within their own display cases. 38 Outside the room are written and visual forms of historical information that are pertinent to the three documents. Some of this information acknowledges more challenging and contested narratives of New Zealand history than what is on offer on Level 4 at Te Papa.

As for He Tohu, the student teachers noticed gaps and silences in the way the exhibition constructed a narrative of colonial history. They noticed the information displayed outside the document box made it difficult for visitors to discern how the three documents connected.

Are there only three moments in time that make up New Zealand history. What about the New Zealand Wars? The three documents were quoted in a lot of places and there was a picture timeline, and again it was sort of like who chose this [information]? And some of the documents and the photos were larger, and so that inherently makes one go ‘Okay, well, these are the important ones.’ because most people don’t go into a museum and read every single plaque completely.

I thought the colours were really interesting, because they had a different colour for each document and its sort of like here’s the section and one chunk and this is one moment. We have He Whakaputanga, and then Te Tiriti – what happened in the middle bit? The exhibition doesn’t encourage you looking in between the chunks and how it’s all connected.

Outside view of the He Tohu exhibition. (Photograph by Mark Beatty, National Library of New Zealand)

Inside the document room, the student teachers noticed that the size, shape and juxtaposition of the three documents ensured that that treaty signing was at the forefront of visitors’ minds, placing more importance on the intent of an equitable partnership, as opposed to racial discord.

There were three cases for Te Tiriti, and one for the [Women’s Suffrage] Petition and one for He Whakaputanga. Even though the size of the Petition and He Whakaputanga may physically be bigger, the exhibition is saying here’s half this room taken up by Te Tiriti. Three cases really put it up on a pedestal, compared to He Whakaputanga which is just as important. There’s a sense of prioritizing the Treaty in New Zealand history.

Although He Tohu presented a more contested view of New Zealand history than Signs of a Nation, the students teachers relayed similar insights about how the design of the exhibition spoke to a harmonious view of Indigenous-settler race relations in present times.

There was like a strip of leaves as you walk in, and I remember thinking I don’t quite know how leaves relate to these three documents, alongside the natural wood and the curves and the natural fabric that was used. It made me think that Māori are more in touch with the natural environment, and they’re just inherently more spiritual and that’s again sort of pushing them into the past or pushing them into a box. A literal box.

The curved seats [in the wall] encourage people to sit and engage spiritually and bask in the glory of these documents... actually it’s the other more contextual information that you maybe want people to sit with [outside the room]

The student teachers’ critique of how the document room cultivates a level of embodied racial comfort, raises questions about to what extent the environment contributes to the ability to ask critical and probing questions about national history. In He Tohu, the students appeared to be considering how there are layers of embodied messages that direct visitors towards a historically resolved view of New Zealand’s difficult histories.

Inside the He Tohu document room. (Photograph by Mark Beatty, National Library of New Zealand)

The student teachers saw a relationship between He Whakaputanga and Te Tiriti o Waitangi as ‘documents that laid out an intention for the direction of the country’ but their connection to the Women’s Suffrage Petition was less clear.

The suffrage is quite different though because it’s typically a white feminist movement. The exhibition does mention Māori woman and it went a little bit into the Māori parliament, with Meri Mangakāhia, but the Māori Women’s Suffrage Movement was kind of separate I believe to the mainstream. I don’t know if I’ve got the facts right on that, but the exhibition didn’t really go how those racial dynamics play out in women’s activism and the suffrage movement wasn’t really there. They’ve got photos of Māori woman who were taking out the petition as sort of an effort to include them, but it wasn’t much.

The image of Kate Shephard on the money and how capitalism is intertwined with colonisation is interesting. I think the commercialisation of knowledge would be something interesting to talk about, but no one ever really does in a museum. Most people know she’s on the $10 bill, so you wouldn’t really think they need to put that on the wall. The main reason I can think of to put it there is to say here’s how you know she’s really important because she’s on our money. Money is a symbol of capitalism, which is one of the big things that pushes down and manipulates Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous peoples. The note shows we value a White woman who did some great stuff but wasn’t the only suffrage leader or woman of note in New Zealand history.

By channelling a haunting, the student-teachers could move past the physical, ontological and affective buffers, which cultivate a sense of comfort about contemporary race relations, to think critically about how colonialism intersects with the histories of other ethnic and social groups. Placing understandings about settler colonialism and difficult histories at the forefront of thinking about Māori and Pākehā relations today encouraged the students to think about how objects on display can serve a celebratory cause and be implicated in mechanisms of colonial control.

Moreover, the ability to channel a haunting led student-teachers to critically evaluate the behaviours of other museum visitors and consider how they align to the function of the settler colonial crypt. A group of young adolescents moved through He Tohu during the visit and their lack of interest in the exhibition highlighted the importance of going to national institutions with historical context and understanding under your belt.

I remember listening to the Pākehā teacher taking a group of school kids around, and they were just so uninterested. They wanted to be on their phones. The teacher wasn’t even doing anything to make them interested – no extra information, nothing like that. It was like they didn’t know anything either which is a huge problem.

Although He Tohu was not associated with lovely knowledge as obviously as Signs of a Nation, Kim, AJ and Emma discovered that the embodied messages they received were in line with a comfortable and soothing view of colonial history that aligns with a need for settlers to reimagine that colonisation did not cause detrimental harm to Indigenous people. Rose writes that ‘learning from difficult knowledge asks something intimate of the learner, and it requires the learner to recognize his or her attachments that organize his or her self-identity’. 39 The organisation of information, objects, lighting and layout inside and outside the He Tohu document room distances Pākehā visitors from the shame, discomfort and anger associated with realising how historical and contemporary forms of colonial violence continue to impact Māori today.

Ghosts that Demand their Due

Haunting raises spectres, and it alters the experience of being in time, the way we separate the past, the present, and the future. These spectres or ghosts appear when the trouble they represent and symptomize is no longer being contained or prepressed or blocked from view... [a ghost] has a real presence and demands its due, your attention. 40

In the passage above, Gordon explains that hauntings and the unresolved trouble that ghosts represent are compelling and demand some form of action. The process of channelling a haunting at Te Papa and in He Tohu challenged the student teachers’ thinking and evoked strong emotional responses:

[The field trips] made me angry. I’ve come to realize over this year that a lot of what people perceive and want to believe about history has to do with where they’ve grown up and the communities where they’ve grown up… I can’t go to any site anymore and not think about what perspective it’s showing.

Te Papa is very disconnected from the reality of New Zealand’s history and that made me quite upset. I felt disappointed that this is what they’re relaying, and I probably wouldn’t go back.

The student teachers spoke candidly about the long-lasting effects of channelling a haunting, which included teaching school students how to critique settler memory and forgetting in mundane environments. AJ took one of her classes to the Petone Settlers Museum. She got her students to do field notes and noticed that they responded the same way she did during her museum visits. Kim recounted how she spontaneously stopped her Year 13 New Zealand History class and got them to sit in silence, look around their private boys’ college classroom and consider the cultural bias in that space. Finally, Emma and Kim reflected on the scaffolding process required to teach channelling a haunting to primary and secondary school students. Scaffolding supports students as they learn and develop a new concept or tool, such as teacher modelling or breaking up the learning into chunks. 41 Emma thought you could start by teaching students to just notice things, like the natural fibre in the wood in He Tohu and encourage them to ask, why is that there? Kim thought students could start by looking at a visual text, then introduce aural elements through video, followed by a field trip to public places like Civic Square and Cuba Street in Wellington which she described as ‘completely immersive’.

The seven-week unit was immensely rewarding for Liana, who was excited by the student teachers’ shifts in thinking about how to engage their own students with history. Channelling a haunting had shown AJ, Emma and Kim that the past can be made meaningful in the present if they reframe what counts as historical understanding and difficult knowledge.

One idea I later realized is that national institutions are like sources. Because they’re places where historians have got all of their primary and secondary sources together and have compiled them – so I guess it’s like a history textbook in a way. And it’s interesting to see why they’ve done the things they’ve done and why they’ve laid it out the way they have. I think as history teachers, we need to be a little bit more aware of the fact that they are sources, and we can teach our students to look at the limitations, the reliability, and whether can we trust these sources. But, when it comes to sites of historical and national significance, I feel like we’re very much just accepting that they are the way they are, and that’s the nation’s history and we don’t come with this lens of scrutiny. But they are living exhibitions rather than information in a textbook. We just need to change the way we look at them and be more critical in doing that.

Conclusion

In this article, we have argued that secondary school students can be taught how to channel a haunting to deconstruct ways that settler memory and forgetting is integral to the presentation of New Zealand history in national institutions. We have conveyed our own experiences to show how the teaching process supported students to deconstruct the way that museum exhibitions engage with lovely and difficult knowledge about national history. Although He Tohu engaged intellectually with New Zealand’s difficult histories, a harmonious and historically resolved view of Indigenous-settler relations was communicated through bodily senses, thus preserving the truth claims of historical amnesia where it is imagined that colonial violence was not really that bad and has not had a significantly negative effect on any group in society today.

In settler societies, difficult knowledge can be attributed to cognitive understanding of historical colonial violence and environmental and ongoing mechanisms of colonial control. The settler colonial crypt is a structure that coddles settler groups, providing a false sense of reality that can impede the need to make wide-sweeping social changes that aim to deliver equitable outcomes for Indigenous people. Channelling a haunting provides students with tools to engage intellectual, emotional and embodied messages about national identity and consider how settler memory and forgetting is mediated at national institutions. The process engages key ideas outlined in the new curriculum, including colonisation, settlement and power, in meaningful and transformative ways. As one student teacher said, ‘once you know, you cannot unknow’. While this paper focusses on exhibitions, we believe there is potential to channel a haunting at other types of national institutions, in order to support students to further deconstruct how everyday landscapes and memoryscapes are shaped according to settler design. 42

Acknowledgements

This work was informed by research carried out as part of a Marsden grant awarded by the Royal Society of New Zealand.

Endnotes

1 Ministry of Education, 2022, Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories (Online). Available: https://aotearoahistories.education.govt.nz/content-overview (Accessed 22 May 2022).

2 The Treaty of Waitangi (the English version) and Te Tiriti o Waitangi (te reo Māori versions) were signed in 1840 by many Māori leaders and representatives of the Queen of England to recognise collective Māori ownership of lands, forests, and other properties, and gave Māori the rights of British subjects. But whether Māori ceded sovereignty of New Zealand to the Crown or sought to retain their chiefly status is one of many issues exacerbated by different versions of the Treaty | Te Tiriti.

3 Ministry of Health, 2020, Wai 2575 Māori Health Trends Report (Online). Available: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/wai-2575-Māori-health-trends-report; Ministry of Social Development, 2021, The Social Report 2016 – Te Pūrongo Oranga Tangata (Online). Available: http://socialreport.msd.govt.nz/health/suicide.html; Department of Corrections, 2021, Prison Facts and Statistics – March 2021 (Online). Available: https://www.corrections.govt.nz/resources/statistics/quarterly_prison_statistics/prison_stats_march_2021; Ministry of Education, 2020, School Leavers with NCEA Level 2 or Above. Education Counts (Online). Available: https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/indicators/main/education-and-learning-outcomes/school_leavers_with_ncea_level_2_or_above

4 Vincent O’Malley, The New Zealand Wars | Ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa, Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, 2019.

5 The New Zealand Wars took place between 1843 and 1872. These brutal conflicts between invading British forces and settler allies, and members of small Māori communities defending their lands and ways of life, were not just about land and involved broader questions of sovereignty and authority.

6 Mark Sheehan and Graeme Ball, ‘Teaching and Learning New Zealand’s Difficult Histories’, in New Zealand Journal of History, vol 54, no 1, pp51-68; Michael Harcourt, Teaching and Learning New Zealand’s Difficult History of Colonisation in Secondary School Contexts, PhD Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, 2020.

7 Harcourt, op cit.

8 Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2008.

9 Mario Carretero, Mikel Asensio and Maria Rodriguez-Monero, History Education and the Construction of National Identities, Information Age Publishing Inc., Charlotte, 2012.

10 Gordon, op cit.

11 Deborah Britzman, Lost Subjects, Contested Objects: Toward a Psychoanalytic Inquiry of Learning, State University of New York Press, Albany, 1998.

12 Joanna Kidman, ‘Pedagogies of Forgetting: Colonial Encounters and Nationhood at New Zealand’s National Museum’, in Terry Epstein and Carla Peck (eds), Teaching and Learning Difficult Histories in International Contexts: A Critical Sociocultural Approach, Routledge, Abingdon, 2018, pp95-108.

13 Britzman, op cit, pp119-120.

14 Michalinos Zembylas, ‘Theorizing “Difficult Knowledge” in the Aftermath of the “Affective Turn”: Implications for Curriculum and Pedagogy in Handling Traumatic Representations’, in Curriculum Inquiry, vol 22, no 3, 2014, pp390-412.

15 Kidman, op cit, p105.

16 Dianne Mulcahy, ‘Pedagogic Affect and its Politics: Learning to Affect and be Affected in Education’, in Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, vol 40, no 1, 2019, pp93-108.

17 Uncle Charles Moran, Uncle Greg Harrington and Norm Sheehan, ‘On Country Learning’, in Design and Culture, vol 10, no 1, 2018, pp71-79; Neil Harrison, Fraces Bodkin, Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews and Elizabeth Mackinlay, ‘Sensational Pedagogies: Learning to be Affected by Country’, in Curriculum Inquiry, vol 47, no 5, 2017, pp504-519.

18 Alisa Smith, ‘A Māori Sense of Place? – Taranaki Waiata Tangi and Feelings for Place’, in New Zealand Geographer, vol 60, no 1, 2004, pp12-17.

19 Carl Mika, ‘The Thing’s Revelation: Some Thoughts on Māori Philosophical Research’, in Waikato Journal of Education, vol 20, no 2, 2015, pp61-68.

20 Hana Burgess and Te Kahuratai Painting, ‘Onamata, Anamata: A Whakapapa Perspective of Māori Futurisms’, in Anna-Maria Murola and Shannon Walsh (eds), Whose Futures? Economic and Social Research Aotearoa, Auckland, 2020, pp205-233.

21 Avril Bell, ‘Dilemmas of Settler Belonging: Roots, Routes and Redemption in New Zealand National Identity Claims’, in The Sociological Review, vol 57, no 1, 2009, pp145-162.

22 Michael King, Being Pākehā Now: Reflections and Recollections of a White Native, Penguin, Auckland,1999; James Belich, Making Peoples, a History of the New Zealanders: From Polynesian Settlement to the End of the Nineteenth Century, Penguin, Auckland, 2001.

23 Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang, ‘Decolonization is Not a Metaphor’ in Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol 1, no 1, pp1-40.

24 Joanna Kidman and Vincent O’Malley, ‘Questioning the Canon: Colonial History, Counter-Memory and Youth Activism’, in Memory Studies, vol 13, no 4, pp537-550.

25 Julia Rose, Interpreting Difficult History at Museums and Historic Sites, Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, 2016, p32.

26 Liana MacDonald and Joanna Kidman, ‘Uncanny Pedagogies: Teaching Difficult Histories at Sites of Colonial Violence’, in Critical Studies in Education, vol 63, no 1, 2022, pp31-46.

27 MacDonald and Kidman, op cit, p5.

28 Avery Gordon, ‘Some Thoughts on Haunting and Futurity’, in Borderlands E-Journal: New Spaces in the Humanities, vol 10, no 2, 2011, pp1-21.

29 Gordon, op cit, p63.

30 O’Malley, op cit; Vincent O’Malley, The Great War for New Zealand: Waikato 1800-2000, Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, 2016.

31 Joanna Kidman, Adreanne Ormond and Liana MacDonald, ‘Everyday Hope: Indigenous Aims of Education in Settler-Colonial Societies’, in John Petrovic and Roxanne Mitchell (eds), Indigenous Philosophies of Education Around the World, Routledge, Abingdon, 2018, pp228-245; Tuck and Yang, op cit; O’Malley, op cit; Liana MacDonald, ‘Whose Story Counts? Staking a Claim for Diverse Bicultural Narratives in New Zealand Secondary Schools’, in Race, Ethnicity and Education, vol 25, no 1, 2022, pp55-72; Liana MacDonald and Adreanne Ormond, ‘Racism and Silencing in the Media in Aotearoa New Zealand’, in AlterNative, vol 17, no 2, 2021, pp156-164; Bell, op cit; Claire Gray, Nabila Jaber and Jim Anglem, ‘Pakeha Identity and Whiteness: What does it Mean to be White?’, in Sites, vol 10, no 2, pp82-106; Ngata, T. 2020, What’s Required from Tangata Tiriti (Online). Available: https://tinangata.com/2020/12/20/whats-required-from-tangata-tiriti/ (Accessed 22 May 2022).

32 Gloria Ladson-Billings, ‘Just What is Critical Race Theory and What’s it Doing in a Nice Field Like Education?’, in International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol 11, no 1, 1998, pp7-24; Liana MacDonald, Silencing and Institutional Racism in Settler-Colonial Education, PhD Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, 2018.

33 Kidman, op cit, p102.

34 Liana MacDonald, ‘Notes from the Field: Visiting Boulcott’s Farm and Battle Hill’, in Joanna Kidman, Vincent O’Malley, Liana MacDonald, Tom Roa and Keziah Wallis (eds), Fragments from a Contested Past: Remembrance, Denial and New Zealand History, Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, 2022, pp46-65.

35 Te Papa is New Zealand’s national museum; He Tohu is an exhibition of three iconic constitutional documents that shape Aotearoa New Zealand: He Whakaputanga, Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the Women’s Suffrage Petition; Pukeahu National War Memorial Park is a national place to reflect on New Zealand’s involvement in war, military conflict and peacekeeping.

36 The Rātana movement brought together many dispossessed Māori tribes through religion and politics. The leader, Tahupōtiki Wiremu Rātana, challenged the government about land confiscations and the British Crown to honour the Treaty of Waitangi.

37 Lars Frers, ‘The Matter of Absence’, in Cultural Geographies, vol 20, no 4, p435.

38 He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene: The Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand was signed by 35 predominantly northern chiefs in 1835. Some Māori movements look to the document as a basis for Māori claims to self-determination. In 1893, the Women’s Suffrage Petition played an important role in persuading the government to grant New Zealand woman the right to vote. New Zealand was the first country in the world to do so.

39 Rose, op cit, p33.

40 Gordon, op cit, pxvi.

41 Lev Vygotsky, Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1978.

42 Toby Butler, ‘“Memoryscape”: Integrating Oral History, Memory and Landscape on the River Thames’, People and their Pasts’, in Paul Ashton and Hilda Kean (eds), People and their Pasts, Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp223–239.