Public History Review

Vol. 28, 2021

Unfinished Business: Rewriting the Past

Anna Clark

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v28i0.7753

You could argue that history itself, the stories we tell ourselves, is unfinished business. The idea of rewriting history happens again and again. Each generation revisits the history-making of forbears. Within one generation there’s disagreement over history. So history is unfinished business, driven in part by debates over colonisation, sovereignty, injustice and decolonisation.1

Think about Captain James Cook. He comes to Australia in 1770 and claims it on behalf of the British crown. But his statue is not erected until 1879. Why is that? Cook is killed in Hawaii in 1779.

A hundred years later, the colony of New South Wales seeks to memorialise his contribution to Australian history. Why 1879? Arguably it’s a moment of increasing national sentiment in Australia and nearly a century after colonisation. There’s a sense that Australian history begins with colonisation. There’s a sense that colonial Australian history has something to commemorate. So, towards the end of the nineteenth century the colonies are moving towards federation. There’s a feeling that history is needed to tell the story of the white Australian nation and that monuments commemorate and celebrate this progression. So, in that time history was about progress: White Australia, nation-building and celebration.

Fast forward another hundred and forty years. History means something quite different to many if not all people. So if we look at the interpretations of the Captain Cook statue we’re seeing those different layers of history and the fact that history is unfinished business. In 1879 there’s a very strong sense of what history is. In 2020 our understanding of history is different. We read those attempts to pull those statues down – and whether or not you agree with that move – as another interpretation of what history is and how we should understand Australia’s past.

There’s a tendency with big monuments to see their concreteness. There’s this big statement about Australian history – literally cast in bronze or written in stone. But as with all historical sources, whether you’re in Year 10 or you finished your PhD in history twenty years ago, you need to ask: who, when, where and why? Who put up the Cook statue? When was it put up? Why Hyde Park south? And why? Moves to pull it down, spruce it up for a celebration, vandalise it or protect it can create a sort of a hybrid reading of that statue. And it gives you a very clear sense that readings and understandings of history have changed over that time.

Statues can also lie. Maria Nugent has written about ‘lies in the landscape’ in relation to Cook and the national park at Kurnell at Botany Bay where Cook came ashore at Inscription Point. Take the Hyde Park Cook statue. Inscriptions on the monument read:

[Front Face, northern side]

‘Captain Cook/ This statue was erected by public subscription,/ assisted by a grant from the New South Wales Government, 1879’

[Part lie: most of the money came from the government; subcriptions from the public were small.]

[On the eastern side]

‘Killed at Owyhee, 1779’

[Yes.]

[On the southern side]

‘Discovered this Territory, 1770’

[Discovered? Really?]

[On the western side: approved by the Sydney City Council on 3 March 1908]

‘This tablet was affixed by the Yorkshire Society of N.S.W., as their tribute to the memory of Captain James Cook, 1908’

[Cook was born at Morton in Yorkshire in 1728. New South Welsh Yorkshire men were carving themselves a place in the sun in Australian history]

Police guarding the Captain Cook Statue during the Black Lives Matter protest, 12 June 2020

There was a huge crowd for the unveiling of the Cook statue. But at the same time there was a growing sense in the 1880s and 1890s – from the Bulletin school of radical nationalists including people such as Henry Lawson – that Australians were learning too much about imperial history and not enough about their own history. There’s a great article that Lawson wrote towards Federation where he says: ‘Our school children know all about the kings and queens but don’t know anything about their own country’.2 So it’s not straightforward. It was opened to great fanfare and no discussion was had. But at the same time we can’t deny the fact that at that time there was a strong sense that Australia had a history that should be celebrated. And there was a sense of progress. But progress for whom?

Who’s left out of that narrative of progress? W.E.H. Stanner wrote that a whole quadrant of Australian history is excluded from the official narrative – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. What does that exclusion mean? And what does it mean to include those perspectives? What does that do to history? Does it change what we know as capital-H history that we formally teach and learn?

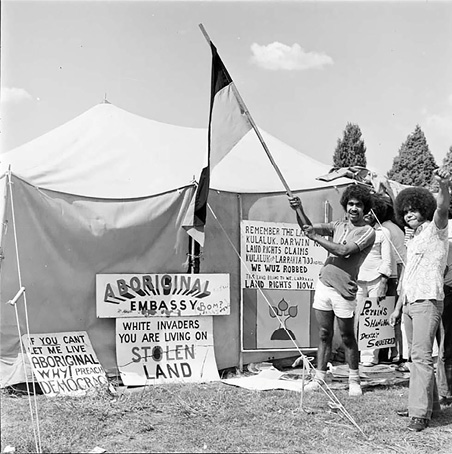

There’s an increasing recognition that history is not impartial – that it’s not objective. This isn’t something that’s just happened in the last five years. You can see a growing awareness of this particularly from the 1970s and 1980s. Consider the Tent Embassy and the signs that are there:

Aboriginal Tent Embassy, Canberra, c1973 (National Archives of Australia)

‘White Invaders, You Are Living On Stolen Land’. That’s a very different re-reading of Australian history to what had been the sense of progress until then. So this is a conversation that’s been happening for fifty years in the academic history profession, and even longer than that in Aboriginal and other communities.

There are other forms of cultural remembering: 1938 – the sesqui-centenary – the Day of Mourning; Xavier Herbert’s Capricornia; Eleanor Dark’s Timeless Land; Louis Nowra’s Inside the Island. These conversations about whose history, whose ‘progress’, have been happening for a long time. But they’ve come to the fore, particularly now with Black Lives Matter and the Uluru Statement from the Heart, calling for a truth-telling about our history. It’s really important to remember if you think about what history is that this isn’t just a matter of a cultural turn, where anything goes or every perspective is valid. This is actually saying: ‘No, there is a truth, and it needs to be told. And without it we’re living a lie.’ This is not healthy.

There is also a changing understanding of who is a historian. There aren’t many Indigenous historians in university history departments in Australia. But the idea of Indigenous historians in other institutional and community contexts is becoming more and more widespread. Changes will continue to happen and there’s growing Indigenous perspective within the formal discipline. History in the academy is also at a critical crossroads and it needs to take community engagement seriously. The statue wars has starkly highlighted the current situation.

Endnotes

1. This commentary is an edited transcript of a talk which I gave for the University of Technology Sydney Australian Centre for Public History webinar on the statue wars on 11 September 2020 available at https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=972479913267957&ref=watch_permalink (Accessed 11 October 2020).

2. Henry Lawson, ‘A Neglected History’, The Republic, 1888.