Public History Review, Vol. 26, 2019

ISSN 1833-4989 | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/phrj

ARTICLES (PEER REVIEWED)

‘in defence of liberty’?: An Atlas of Incarceration

Minna Muhlen-Schulte

GML Heritage

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v26i0.6823

Citation: Muhlen-Schulte, M. 2019. ‘in defence of liberty’?: An Atlas of Incarceration. Public History Review, 26, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v26i0.6823

© 2020 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

One-hundred-and-fifty kilometres north of Melbourne, the highway narrows and bends around shoulders of grey ironbark trees. The earth dries, houses recede and paddocks widen. Here ruins of Second World War internment camps lie crumbled inside farm properties or sprawl out through the scrub in places like the aptly named Graytown where concrete foundations are entangled in gum roots. Scattered throughout the site at ankle height – so that I almost trip – are the remains of grey ablution and latrine blocks, broken bricks and warped wire fences. Three steps ascend a concrete platform, its edge marked by the base of a bright red chimney. A low background hum of trucks along the Heathcote-Nagambie Road is punctuated by the singsong of iron bark tree branches rubbing against each other. Rusty cans and the burnt tyre tracks hint at recent activity. But over eighty years ago this was a woodcutting camp (Figure 5) for Italian and Germans Prisoners of War including members of the HSK Kormoran raider which sunk the HMAS Sydney off the Western Australian coast in 1941.

Figure 2 Woodcutting camp ruins Graytown, Victorian (Photograph Theresa Harrison)

Figure 1 Tatura Camp Prison cell ruins, Victoria. Below Figure 3 Woodcutting camp ruins Graytown, Victoria (Photographs Theresa Harrison)

This is a landscape borne out the Emergency Powers (Defence) Acts of 1939 and 1940 passed by Australian federal parliament after the outbreak of war in Europe. There was ambivalence about this legislation from the outset. Prime Minister Menzies acknowledged that: ‘The greatest tragedy that could overcome a country would be for it to fight a successful war in defence of liberty and loose its own liberty in the process.’1 In 1940, 45,000 people living in Australia became targets of surveillance – because they were born in countries that had become the nation’s enemies.2 By 1942 more than 12,000 people were interned in Australia in fourteen complexes across the country. Civilian foreign nationals were imprisoned along with captured enemy German, Japanese prisoners of war and enemy aliens deported from Britain. 3 Victoria hosted the largest complex of eight camps near the town of Tatura in an area better known to Australians as the home of Goulburn Valley tinned fruit.

I came looking for these remains to understand how complex heritage sites like this are interpreted or as the case may be largely uninterpreted. Heritage places with dissonant history are harder to interpret not only because heritage assets are often constructed as a tourist product. They also rely on ‘comfortable, harmonious and consensual views about the meaning of the past.’4 Sites of internment do not provide such a clear cut story. Although it is part of Australia’s wartime history, internment is not as easily acknowledged because it does not conform to the Allied powers ‘epic story of unity, courage, endurance and final victory.’5 Today the legacy of internment legislation literally marks the landscape in Australia and sites across the globe with camp ruins, cemeteries and memorials forming a strange atlas of incarceration.

Figure 4 Tatura Camp prison cell c1945 (Tatura Irrigation and Wartime Museum)

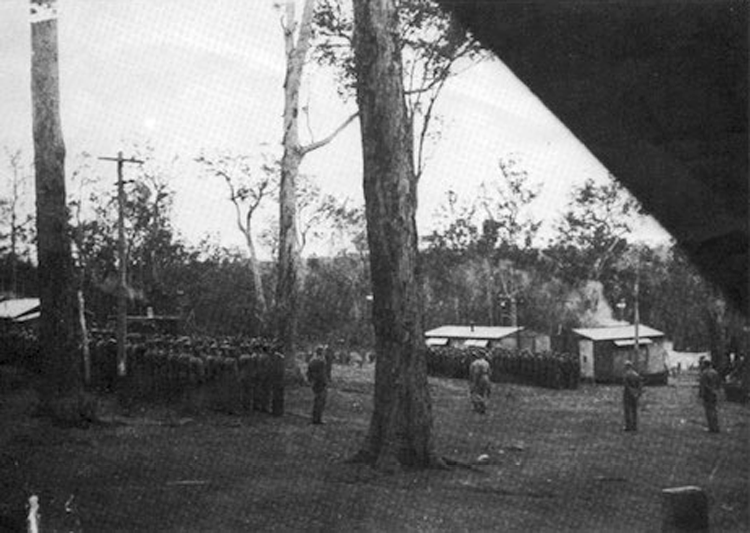

Figure 5 Prisoner of war woodcutting camp, Graytown, Victoria c1943 (Tatura Irrigation and Wartime Museum)

In Limbo

Perched on the Waranga Basin the scale of the Tatura internment complex was equivalent to a small city and far larger than the total population of its namesake town and satellite villages, Murchison and Rushworth (Figure 7). Internees arrived from different starting points. If not refugees or prisoners of war from overseas, they were civilians rounded up and kept in a procession of spaces from Long Bay Gaol in Sydney, Wirth Circus ground in Melbourne, Loveday in the Riverlands of South Australia, Hay Camp in Orange NSW, Dhurringile Mansion then camps around Tatura.

Figure 6 Map of Australian internment camps during the Second World War (National Library of Australia)

The resulting mix of internees was an extraordinary jumble of identities, especially among the German internees who were made up of German Jewish refugees escaping Nazi Germany, Wehrmacht or German Army prisoners of war captured in battlefronts such as North Africa, Temple Society members – a German religious community in Palestine captured by the British – German missionaries of New Guinea and German civilians from well-established communities in Melbourne and the nineteenth-century families of the Barossa Valley. Internees themselves were keenly aware of the differences. Forty-two of them wrote to the Australian government in 1941:

Apart from our feelings, that an error has been committed, by interning us at all, it means an unnecessary hardship and mental torture to us to be put together with our persecutors and political enemies … we consider ourselves in a position of imminent personal danger, both mentally and physically.6

While for the most part internees were treated humanely, the stigma and separation of internment had a lifelong impact on people’s marriages, families and livelihoods. The legacy for post-war Australia’s cultural life was far richer. Those internees who stayed, like Leonhard Adam, made an extraordinary intellectual contribution through his work in anthropology at the University of Melbourne. After his release from Tatura and a brief fruit picking stint, Helmut Newton went onto to become iconic fashion photographer. Former Bauhaus artist Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack influenced Australia’s abstract movement. Other less known figures like Wolf Klaphake contributed to science as a chemist and inventor.

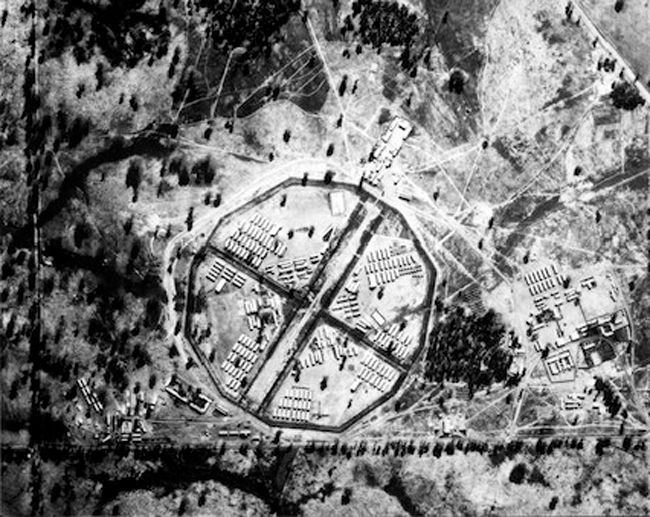

Figure 7 Aerial view of Camp 13, Murchison c1942 (Tatura Irrigation and Wartime Museum)

But the internees’ story can’t be told in isolation in Australia without understanding their connection to and experience of other sites globally. Many of the internees from overseas had already been incarcerated in British camps such as the Isle of Man. And then experienced nightmarish journeys across the sea when deported to Canada and Australia. The palpable despair of escaping Nazi Germany only to be interned at the far end of the Southern Hemisphere is recorded in letters from internees like jazz musician Stefan Weintraub who wrote to the Australian government asking: ‘What have I done that I must endure all this and that I find no place in the world where I am welcome?’7

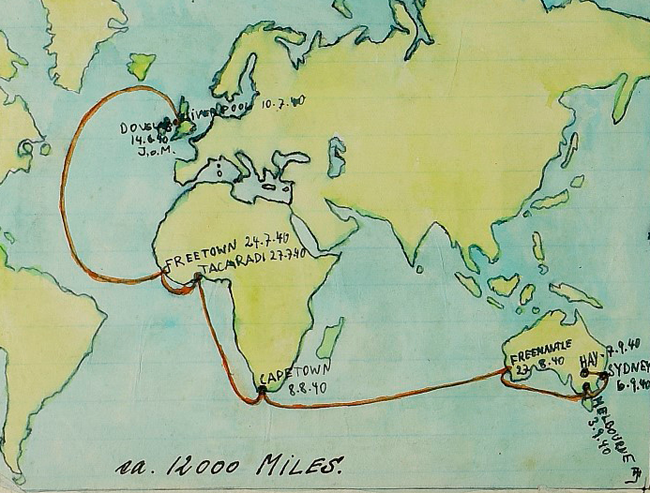

The Tatura Irrigation and Wartime Camps Museum holds hand drawn maps, diaries and paintings. You can see the internees’ attempts to fathom their journey as they were shuffled across the globe, Australia looming large in their mind’s eye. Mirror collections at the National Archive in London also hold items like an unnamed internee’s drawing (Figure 8) listing the miles, and stops across continents when shipped from the Isle of Man in the United Kingdom to Hay internment camp in New South Wales and back again.

Figure 8 An extract from a diary kept by internee who was shipped from the Isle of Man to Camp Hay, Australia and back (Source: National Archives London HO 215/263)

Leonhard Adam documented his experiences in a series of watercolours. Fleeing Berlin after the Nazis’ Nuremberg Laws stripped him of his profession in law and ethnology, Adam sought shelter in Britain. He was classified an enemy alien and deported to the Isle of Man, an islet of such ‘isolated and rugged topography it seemed to offer an ideal place to detain those deemed a threat to British security.’8 In one watercolour (Figure 9) we see part of the Isle of Man prison from an unsettling viewpoint of the camp – a claustrophobic maze of concrete walls, barbed wire and a long afternoon shadow with a lonely hunched figure loping along the path. There is no sky or any sense of an exit. It’s a pallid and lifeless scene. Deported to Tatura, Adam continued to paint. His palette lightened with the expanse of blue sky and better conditions that allowed him to teach in the camp, though the melancholy in the work is still palpable along with the tedium of being detained without trial for an indeterminate period.

Figure 9 Leonhard Adam’s watercolour of Douglas Internment Camp Isle of Man, 1940 (Tatura Irrigation and Wartime Museum)

But perhaps one of the most poignant and strange creations is a stone sculpture seen in photographs of Tatura camp in the 1940s (Figure 10). Carved by Karl Duldig it was destroyed at the end of the war and then recreated in 2016. It was also rendered in a print by Robert Felix Emile Braun and watercolour by other internees such as Leonhard Adam at the time (Figures 11 and 12). Flesh coloured, with a wave on the cusp on breaking and gulls overhead, it was dedicated to internees drowned aboard the Arandora Star in 1940. The story of this ship ricochets between continents leaving a series of memory landscapes in its wake.

Figure 10 Arandora Star Monument c1942-46. Camp 3C, Rushworth, Victoria. The girls in this photo are thought to be Gerturde Hermann and Marianne Kirsch. Both girls had lived in Tununda, South Australia Shrine of Remembrance/Tatura Museum)

Figure 11 (left) Arandora Star monument by Leonard Adam 1941 (Source: Tatura Irrigation and Wartime Museum). Figure 12 (right) Arandora Star monument by Robert Felix Braun, 1941 (as reproduced in Dunera Lives)

Incarceration on the Infinite Sea

In 1940 internees deemed a security risk in Britain as a potential ‘fifth column’ of fascist insurgents were interned in a ‘ramshackle archipelago of camps.’9 Under the British Emergency Powers (Defence) Act, they became civilian internees not refugees or prisoners of war. They were then deported from Britain aboard ships such as the SS Arandora Star, HMT Dunera and Queen Mary which were headed for Australia and Canada – dominions with greater space to hold the prisoner overflow. The imprisoned were a mix of German civilians and expatriates including Nazi sympathisers, German Jews fleeing persecution, German merchant seamen, Italian internees and British troops to guard them. An official British Home Office memorandum described the view of German internees: ‘Amongst those who claim to be refugees there may be some whose claim is doubtful and others who though in fact refugees are of such character that they cannot properly be left at large.’10

These ships represent the most amorphous space in the internment story. Aboard them, people were adrift between places, defined only by who they weren’t. Some of them unable to be a citizen in the country they had fled from or to. None of them knew their destination let alone their fate once they reached it.

On 1 July 1940, the British Government piled 712 Italians, 438 Germans and 374 British navy and soldiers onto the Arandora Star bound for Canada. A converted pleasure cruise liner, now painted grey, its decks were threaded with barbed wire to secure the internees. Captain Edgar Moulton despaired: ‘if anything happens to the ship that wire will obstruct passage to the boats and rafts. We shall be drowned like rats.’11 Twenty-four hours later his fears were realized. The ship was torpedoed and sunk in the middle of the night by a German U-boat. Internee Uwe Radok remembered the ‘dull crack and breaking glass, sound of machine stops … smoke and gas in the hall … everyone … pushing upwards.’12 Captain Moulton stood calmly side by side with POW German Kriegsmarine Captain helping to evacuate who they could. Meanwhile British guards fired at internees ‘escaping’ in lifeboats.

Over half the internees died – mostly the Italians who were encased by the barbed wire on the lowest decks. The ship sank in thirty minutes. But it took almost a month for the bodies to wash ashore coming in with the tides along a 600 kilometre stretch of coast from western Scottish isles and the west coast of Ireland. Lost embarkation rolls and the fact that internees had swapped identities with each other before boarding the ship, and the length of time the corpses were in the water, made identification impossible. Fishermen of Donegal found a lifeboat riddled with bullet holes and blood smears but didn’t know where it had come from. They repurposed the wood into fishing vessels and sheds in their village.13

A Canadian destroyer, the St Laurent, picked up the survivors after they had spent seven hours in the water. One week later 450 were sent to Tatura aboard the now notorious Dunera where Jewish refugees were brutally treated at the hands of British guards who viewed them as Nazi spies.

Burying your Enemy

Travelling through Dublin last year, my friend offered to take me to a German war cemetery hidden up in the Wicklow Mountains. We drove up to the site. A long summer drought had turned the rolling Irish green hills golden brown. Fields of heather were dried into spikey straw underfoot. Nestled on the rise was an old British barracks from the Napoleonic era, now the Glencree Centre for Peace and Reconciliation. We passed through the converted barracks building with a café filled with potted jams, hot chocolate and tea towels for sale and walked into the Deutscher Soldatenfriedhof (German War Cemetery). Here moss-covered crucifixes radiate out from a memorial shelter with a gold Pieta mosaic.

A perfunctory sign announced that German internees from the First World War are buried here alongside Luftwaffe pilots who crashed over Ireland, or drowned Kriegsmarine sailors who washed up on Ireland’s shores during the Second World War. My eyes latched onto its final note: ‘that [at] least 46 German civilians from the Arandora Star, are also buried here.’ Six months later and thousands of miles from Tatura the story of this ship had unexpectedly surfaced again.

Many of the graves are still unidentified. Some lie even further afield in the north in Donegal’s cemeteries. The civilian passengers are interred alongside Nazi spies like Dr Hermann Görtz who collaborated with the Irish Republican Army against Britain. Görtz’s is the only plot with an individual memorial. One of the Arandora Star’s Jewish refugees, Hans Moeller, lies buried on top of another grave.

The mirror to Glencree on the other side of the world is the Tatura German War Cemetery. These sites are just two of 833 military cemeteries managed by the German War Graves Commission in forty-six countries. The Australian Department of Veterans’ Affairs explains: ‘the German Military Cemetery in Tatura, Victoria, and the Japanese War Cemetery at Cowra, New South Wales, contain respectively the graves of 250 and 523 war dead of our one time adversaries.’14 But the cemeteries do not just contain our ‘one time adversaries’. Many civilians considered to be the enemy within Australia during both world wars were also laid to rest here. At Tatura a small plaque notes that German civilians who died during internment in the First World War across Australia have been disinterred and reburied at the Tatura German War Cemetery. The burial plots of Wehrmacht soldiers captured by the British in North Africa lie alongside German-Australian civilians arrested in the 1940s, demarcated by an iron cross for soldier and a crucifix for civilian.

The Tatura cemetery like Glencree has been coerced into a singular, neat representation of German nationals as our enemies over two generations. It collapses not only time but the varied identities and experiences of the individuals interred within them. Perched awkwardly in the midst of an Australian country town, the internees’ lives are commemorated by the German embassy in ceremonies in November each year. Even in death internees were jumbled together as haphazardly as they were incarcerated in life, the fault lines of identity and nationality continually shifting beneath them.

***

In the same way the ruins of Tatura have become unmoored from the spatial layout of the original internment complex, and stranded far in time from the people who might remember them, the memorials for the Arandora Star are scattered in a disconnected trail across the globe. The attempt to fix this story of interment to one site is fragmented – from the bronze lodga in St Peter’s Church in London, memorials in Liverpool where the ship departed, Glasgow’s St Andrew’s Cathedral, Glencree cemetery, the countless memorial chapels and plaques in Italy and, in the far southern hemisphere, the strange stone wave at Tatura. The sculpture only outlasted the tragedy a few years before it was ground down into the brown earth of the Waranga Basin. The attempt to fix the brined flesh that drifted in the Atlantic into something permanent – something immoveable – did not work.

None of these memorials or the ruins hold the story of internment in its entirety: the abstract policies that reclassified internees overnight into citizens of nowhere; the disparate identities aboard the ships; their bodies pushed and pulled across the ocean’s tides to far flung locations; and the procession of peripheral spaces they were incarcerated and buried in.

In the years immediately after the Second World War building material was salvaged from the Tatura camp to infill homes amid the housing shortage crisis, leaving the stubbed concrete foundations to tell just part of the story. Today as though the landscape cannot shake the historical legacy of incarceration, new correctional facilities inhabit some of the old sites of the Tatura complex. These include Dhurringile Prison where 328 men are incarcerated in the grounds of an old gold rush-era mansion. Most of the internment sites are formally registered on the Victorian State Heritage inventory and some parks signage exists. But mostly they are obscured within private farmland.

Perhaps the most meaningful way these landscapes are interpreted is in the ephemera of internees’ records such as Leonhard Adam’s watercolours or etched in the internees’ intangible memories like Helga Griffin who describes how every time she thinks of her arrival in Tatura Camp: ‘there is a particular place my memory lands like a glider. I see the same dusty barren land. A number of huts are on the periphery of my vision. My eyes rest on a bare yard where soil and gravel are compacted … I hold my brother’s hand. I am six-and-a-half. He is three years younger. Clinging to me as if I were his second mother.’15

These sites don’t allow for an easy interpretation of the Second World War in Australian history. Interning individuals without trial because of their ethnicity or categorizing them as ‘internee’ instead of refugee to remove legislative burdens opens up questionable moral terrain. In the interpretation of these sites it is easier to retreat back into national identity as the definitive marker between their history and our history. However, exploring the subjective experiences of those interned through their publications, artworks and sculptures reveals that these scattered regional sites are bound to a global story. A story of total war that disrupted the lives of people on a scale still unprecedented today. It haunts our landscape and imagination as we turn away people seeking shelter on our shores once more. The internees’ memories hang invisibly like fine gossamer threads off the weight of concrete ruins and memorials as we travel, in one way or another, through these landscapes today.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to acknowledge the support of the NSW Government through Create NSW 2018 History Fellowship.

Endnotes

1. Prime Minister Menzies as quoted in Joan Beaumont, Ilma Martinuzzi O’Brien and Matthew Trinca (eds), Under Suspicion: Citizenship and Internment during the Second World War, National Museum of Australia Press, Canberra, 2008, p2.

2. Beaumont, et al, op cit, p3.

3. Wartime internment camps in Australia, National Archives of Australia (online). Available: http://www.naa.gov.au/collection/snapshots/internment-camps/introduction.aspx (accessed 10 October 2019).

4. Laura Jane Smith, Uses of Heritage, Routledge, London and New York, 2006 p81.

5. Richard Dove (ed), ‘“Totally Un-English?”: Britain’s Internment of Enemy Aliens in Two World Wars’, The Yearbook of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, vol 7, Rodopi, 2005, p1.

6. Klaus Neumann, ‘“Victims of ‘unnecessary hardship and mental torture”; Walter Stolting, Wolf Klaphake, and other incompatibles in wartime Australia’, in Beaumont, et al, op cit, p105.

7. Stefan Weintraub, 14 September 1940, correspondence with Australian Government concerning question of nationality, National Archives of Australia, Box 71, Series no ST1233/1, Control Number N1922.

8. Richard Dove (ed), ‘“Totally Un-English?”: Britain’s Internment of Enemy Aliens in Two World Wars’, The Yearbook of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, vol 7, Rodopi, 2005, p13.

9. Ken Inglis, Seumas Spark and Jay Winter, Dunera Lives: A Visual History, Monash University Publishing, Clayton, Victoria, 2018, p43.

10. Home Office Memorandum, TNA HO 213/1834 quoted in M. Kennedy, ‘“Drowned like rats”: The torpedoing of Arandora Star off the Donegal Coast, 2 July 1940’, 2010 (online). Available: https://www.mariner.ie/the-sinking-of-arandora-star/ (accessed 10 October 2019).

12. Uwe Radok’s diary is reproduced in Ken Inglis et al, op cit, p63.

13. C. McGinley, 2014 ‘Sinking of the Arandora Star: A Donegal Perspective’, WW2 People’s War – An archive of World War Two memories – written by the public, gathered by the BBC (online). Available: https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/94/a2618994.shtml (accessed 10 October 2019).

14. ‘War Cemeteries within Australia’, Department of Veterans’ Affairs: Office of Australian War Graves (online). Available: https://www.dva.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/publications/commemorations-war-graves/P00125_war_cemeteries_australia.pdf (accessed 10 October 2019).

15. Helga Griffin, Sing for Me that Lovely Song Again, Pandanus Books, Australian National University, 2006, p216.