Public History Review, Vol. 26, 2019

ISSN 1833-4989 | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/phrj

ARTICLES (PEER REVIEWED)

‘I was not aware of hardship’: Foodbank Histories from North-East England

Jack Hepworth, Alison Atkinson-Phillips, Silvie Fisch and Graham Smith

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v26i0.6687

Citation: Hepworth, J., Atkinson-Phillips, A., Fisch, S., and Smith, G. 2019. ‘I was not aware of hardship’: Foodbank Histories from North-East England. Public History Review, 26, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v26i0.6687

© 2020 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Foodbank Histories is a collaborative public history project that began with a basic premise: poverty has a past. Media reports often suggest that foodbanks have appeared suddenly in austerity Britain. But the poverty and inequality driving foodbank use have longer roots. By listening to, and sharing, the stories of clients, volunteers and supporters of Britain’s busiest foodbank, we aimed to challenge myths about food poverty and to understand more about its historical and social context. We believe that such understandings of the past revitalise democratic debate, guard against prejudice, challenge misapprehension and provide opportunities to look in new ways at enduring issues of historical injustice.

In this article, we offer a brief history of food charity in the UK and link the rise of foodbank use to the ‘age of austerity’. Drawing on archival oral history sources, we consider how the experience of receiving ‘welfare’ or ‘charity’ has changed over time. We outline the geographical context of North East England and, more specifically, the Newcastle West End Foodbank. We explain the origins of the project partnership, who we spoke to, and what we heard. The article reports on how our findings influenced public perceptions and conversations about public policy. It details ongoing engagement activities with foodbank clients. We argue that context matters. Place matters in terms of where we do our research, but also in terms of how, where and with whom we choose to share it. Time also matters in terms of the time we take to do our research and the time we spend building relationships.

In Britain, debates over the distinctions between independent and dependent poor emerged in the late eighteenth century. Edmund Burke suggested that the word ‘poor’ should be reserved ‘for the sick and infirm, for orphan infancy, for languishing and decrepit old age.1 Poor law reformers continued rigorously to distinguish between ‘labourers’ and ‘paupers’. Thomas Robert Malthus introduced the dangerous argument that the growth of industry would stimulate population increase without sufficient increase in the food supply. Not only was Malthus’ assertion wrong that food production would not keep pace with population growth. But his belief that the birth rate would increase with a rise in the standard of living was also incorrect. Malthus’s claims, however, provided what some thought was a rational basis for their moral dislike of the poor. Any relief given to paupers would lead to an increase of their numbers, a decrease of the food available for the entire body of the poor and proliferate ‘misery and vice’. Reformers amended the law by separating pauper and poor, giving relief to the able-bodied only through the workhouse.

Food and Poverty

Beginning in the early nineteenth century, ‘Christian paternalism was replaced with Evangelical certitude’,2 positioning poverty as a consequence of vice and fecklessness. Crudely delineating the deserving and undeserving poor, this framing of poverty endured with the rise of nutritional science, amid concerns over motherhood and infant health. In the second half of the nineteenth century ‘working class’ poverty was considered less problematic:

Whatever stigma remained was reserved for the dependent and the unrespectable poor, those who existed on the margins of society or were outcasts from society. The bulk of the poor, the ‘working classes’ as they were increasingly called, were seen as respectable, deserving, worthy, endowed with the puritan virtues that had served the middle classes so well.3

This ‘deserving’ class became the focus of the social welfare reforms of the early twentieth century: the Old Age Pensions Act of 1908 and the National Insurance Act of 1911. The distinction between ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor remains pervasive. As the authors of a study of food provision to pregnant women noted: ‘The twentieth century saw the introduction of social policies with nutritional objectives but there was widespread debate about whether malnutrition and poor dietary quality were attributes of poverty or a reflection of ignorance’.4,5 These victim-blaming discourses continue today.

Since the late twentieth century, policy makers and researchers have used the terms ‘food poverty’ and ‘food (in)security’ to describe worldwide issues. Governmental and nongovernmental reports have abounded, including Hunger, Malnutrition and Food Insecurity in the UK, produced by the Environmental Audit Committee in January 2019. This report found that nearly one in five under-15s in the UK live in a home where parents cannot afford to put food on the table; and that approximately another nineteen per cent of under-15s live with an adult who is moderately or severely food insecure, with ‘limited access to food … due to lack of money or other resources’.6 Food insecurity and poverty are intrinsically linked as the UN Special Rapporteur for extreme poverty, Philip Alston noted in November 2018, calling for the United Kingdom to ‘introduce a single measure of poverty and measure food security’.7

While food provision to the needy is not new, some politicians and policy advisors argue that contemporary foodbanks differ from previous responses to food poverty. An advisor to the New Zealand government, Ross Mackay, has noted the history of marginalised groups, including homeless people without access to cooking facilities, being provided with prepared meals. In contrast, ‘foodbank provision is founded on the assumption that recipients are able to prepare meals for themselves but have no money to purchase food supplies’.8 However, in their special journal edition on the rise of foodbanks in the Global North, Martin Caraher and Alessio Cavicchi claimed that ‘food banks have always existed in some form or other. What is now different is the scale and logistics of food aid being delivered through these outlets’.9

In the UK, political arguments have addressed the reasons for this increased use. Former Prime Minister David Cameron explained that ‘we changed the rules. The previous government didn’t allow Jobcentres to advertise the existence of foodbanks’.10 Similarly, Conservative Under-Secretary of State for Welfare Reform Lord Freud claimed that the increase in foodbanks was ‘supply led’ because ‘food from a foodbank – the supply – is a free good. And by definition there is an almost infinite demand for a free good’.11

Foodbanks and the ‘age of austerity’

The British government’s policy of austerity is closely linked to the significant increase in both the existence and use of foodbanks since 2010. This governmental response to the global financial crisis of 2008 has contributed to a significant increase in inequality12 and this is forecast to continue.13 Philip Alston has highlighted how austerity has been a political choice and ‘a commitment to achieving radical social re-engineering’.14 Many UK foodbank clients are in work,15 reflecting a wider crisis of wage stagnation and insecure work patterns. Figures published in March 2017 showed that six million people earned less than the living wage. Approximately four million children across the UK were in poverty, two-thirds of whom were from families in work.16

Department of Work and Pensions reforms, especially the introduction of Universal Credit, have also stimulated increased foodbank usage.17 Introduced as a simplification of the complex combination benefits and tax credits that exists in the UK, Universal Credit is a benefit payment for people in or out of work. However, the new system has been plagued by problems.18 In April 2018, foodbanks where Universal Credit had been fully implemented showed an average fifty-two per cent increase in usage over the previous 12 months, compared to an average thirteen per cent increase in areas where Universal Credit had either not been introduced, or had been introduced for less than three months.19 Individuals with health problems face particular difficulties. In April 2017, disabled people saw the employment support allowance cut by £30 per week as part of a £3.7 billion cut to disability benefits.20

According to the Independent Food Aid Network, there are at least 2,056 foodbanks operating across the UK.21 Roughly sixty per cent of UK foodbanks are affiliated with the Trussell Trust, an Anglican charity which connects local foodbanks to a national network of food suppliers, media, and advocacy platforms. To benefit from these connections, foodbanks must adhere to fairly stringent policy guidelines that limit the number and content of food parcels to a maximum of three three-day parcels. The Trussell Trust also mediates much of UK media coverage of foodbank usage. The Trust regularly reports on connected issues, such as the impact of welfare reforms. For example, a June 2017 report outlined the demographic profile of people using Trussell Trust foodbanks over the previous twelve months.22

The Independent Food Aid Network also report at least 804 independent foodbanks operating in the UK. Without the Trussell Trust’s centralising protocols, these centres often respond to particular local needs. For example, an independent foodbank in the Garston area of Liverpool, The Orchard, caters mostly for clients aged sixty or older. The Orchard does not use a voucher system. As volunteer John Hay puts it, ‘we accept that people can have more than three crises a year’. This is the only foodbank in the area to distribute fresh produce.23

In this context, research into foodbank provision and use has proliferated. Employing statistical analyses, Rachel Loopstra et al found a strong relationship between welfare cuts, benefit sanctions and increasing food insecurity.24 Kayleigh Garthwaite’s embedded research, as a volunteer at a foodbank in Stockton-on-Tees, elucidated the dilemmas facing clients and volunteers alike.25 Thompson, Smith and Cummins engaged critical grounded theory analysis in ethnographic studies of foodbanks in Greater London.26 Interviewing foodbank volunteers and clients and observing foodbank operations, their study situated food insecurity in broader personal crises, ‘including benefit and housing problems, relationship breakdown, immigration status and other assorted crises’. These insights explored multifaceted food insecurity, including accommodation lacking adequate storage or cooking facilities. Hannah Lambie-Mumford notes the tension between the Trussell Trust’s emergency intervention emphasising ‘relief and alleviation’ and more ‘structural’ responses to overcome poverty and inequality.27

Previous Oral Histories of Food and Poverty

The impact of different ideologies on welfare recipients remains largely obscure. But oral histories over the last fifty years provide some insights. Interviews recorded in the early 1970s and collected for The Edwardians include memories of poverty.28 A former skilled manual engineer, Michael Shannon from Manchester, remembered his father being unemployed around 1910, his mother applying to the Board of Guardians as a result and the arrogance of the ‘domineering’ man who conducted a detailed assessment of the family’s assets by interview. However, what is particularly interesting about the way Shannon remembers this event is that he later talks of his father telling him about entering the workhouse during hardship around 1880. He connects this memory to his own unemployment in the 1920s:

Yes, me father. He told me about it, but I don’t remember it. Used to have to go and do a day’s work at the workhouse if they wanted assistance. I had an accident at work dropped a weight on me foot … So, I put a claim in for compensation [to his employer], but the compensation didn’t come through. And [I went to the] Board of Guardians and applied for assistance. So, they says, ‘Well you had compensation’. I said, ‘Yes, but I’ve drawn nothing’. I says, ‘I’ve had no wages at all for three week’. So, they says, ‘Oh well all we can give you is a food ticket for a pound’. That had to last me the week.29

Those like Michael Shannon, who experienced interwar poverty, poor law relief and the indignities of the means test that followed the demise of the Board of Guardians, would continue to recall a deeply resented welfare system, parsimonious and humiliating assistance and the stigma and fear of poverty. These memories of cyclical economic downturn reflected generational remembering that spanned many decades. This longitudinal collective memory pervaded the UK into the 1980s.

In the ‘100 Families’ project that collected inter-generational oral histories between 1985 and 1988, the oldest interviewees recounted similar memories:

from 1914 to 1939 – well, you know how bad times are now, and how the unemployment is – it was twenty times worse than that. Twenty times worse than it is today. Because they have got money today. There wasn’t money.

However, among the middle generation, in their thirties and forties at the time, there were more ambiguous and contradictory conceptions of want. This cohort had been born into the post-war period of full employment. They were now facing mass unemployment for the first time. As one interviewee asked: ‘I mean, it’s a bit harder now these days because genuine people are unemployed, aren’t they?’30 Or as another put it: ‘If someone is in trouble, I’ll be the first one to help them … Because everybody can be without, but … I’ve got no time for the begging bowl’.31 A third noted:

If you look at the growing problem of unemployment, I think your attitude to that must change when it’s such a severe problem as it is now and whereas in the early days, you tend to feel that it’s composed largely of a group of people who are too damn lazy to get a job. Attitudes must have modified to that considerably.32

During this period of deindustrialisation popular perceptions of poverty were being redefined. The fear of unemployment leading to food poverty is notably absent from the middle and younger generations’ oral histories. Members of all generations thought that while unemployment was to be feared, state welfare benefits would provide for adequate food and cover the rent and even the mortgage.

However, even in a period of widespread and accessible benefits there were people experiencing severe impoverishment. Re-examining two oral history studies of homelessness, collected in the mid-1990s and the early 2000s, provides insights into how receiving charitable welfare shaped people.33 Older men interviewed in the mid-1990s identified external factors, such as war, occupational accidents and malign friendships, as causes of addiction and homelessness. However, the settled view was that these factors were as much to do with fate or bad luck as individual agency. The men and their carers concurred that anyone could be homeless: the phrase ‘there by the Grace of God’ recurs in the accounts collected.

In contrast, interviews recorded by Rebecca Brown in the mid-2000s had a different collective discourse, even though the context – homeless men cared for by a religious charity – was similar. Later oral histories tended to stress family breakdown, abuse, neglect and violence as the causes of homelessness. Comparing the two projects, the influence of interview context was apparent. Those participating in the mid-2000s had been regularly interviewed, including by state benefit personnel and social workers, whereas the men in the earlier study reported being asked questions by charity volunteers and staff. Unsurprisingly, the men in the earlier project, whose experience was rooted in narratives of charitable and religious fatalism, framed their memories in that way.34 This has important implications for listening to the voices of foodbank clients, volunteers and supporters: it reminds us that while poverty has a past it also has a present.

Research Habitus: The North-East of England

The North East of England has a rich industrial heritage. The region’s coal powered the industrial revolution generated demand for migrant workers in the mines, shipyards and other heavy engineering from Ireland, Scotland, Scandinavia and British colonies. For example, South Shields was home to the UK’s first Muslim community, Yemenis who arrived as merchant seamen and married into the local population. However, since the late twentieth century, deindustrialisation has hit the region. Although regeneration efforts have transformed Newcastle’s leisure and cultural activities, some parts of the city and region never recovered. Newcastle was the first UK city to experience Universal Credit, and more than twenty per cent of the city’s population of 270,000 now live in the most deprived ten per cent of wards in England and Wales in terms of income, work, education, health, housing and crime. Some twenty per cent of households have no earner aged sixteen or older and child poverty is fifty per cent higher than the national average.35

Newcastle West End Foodbank (NWEF) was founded in 2013 by volunteers from the (Anglican) Church of Venerable Bede on West Road, within a mile of the old Elswick shipbuilding and engineering works. This area has undergone considerable change over the past fifty years, suffering the loss of industrial jobs, as NWEF volunteer Keith describes:

The industry around Tyneside has basically gone, all the heavy industry’s gone, so people, unless they have a middle-class or fairly affluent background, are going to struggle, and I think that’s what’s happened and that’s why the foodbank is in the West End.

A retired electrician, Keith left the area in the late 1980s. He dates the ‘running down’ of the area to that period. Another local change is immigration and shops changing on the local high street, as older interviewees with longstanding connections to the area note.

NWEF operates as a Trussell Trust franchise. Over the past six years it has expanded to two sites. The hall of the Church of the Venerable Bede remains the first point of contact for most people and opens Mondays and Thursdays, offering hot drinks, biscuits and informal counselling to those collecting a food parcel. A second venue, the Liliah Centre in Benwell, offers a two-course meal every Tuesday and Wednesday and is frequented by clients requiring longer-term support.

NWEF is now the busiest foodbank in England and achieved prominence in 2016, when it was featured in Ken Loach’s film, I, Daniel Blake. The film tells the story of an unlikely friendship between middle-aged Dan and young mum Katie and their struggles with the Universal Credit social security system. In one scene, Dan takes Katie and her children to visit the foodbank where she desperately eats baked beans cold from the can. The scene was filmed on location at the Venerable Bede and features real volunteers alongside the actors. The film was instrumental in shifting conversations about foodbanks away from victim-blaming and towards questioning the social structures that lead people into food poverty. I, Daniel Blake has also become an important frame of reference for people involved the foodbank, with volunteers regularly alluding to the film and its realistic representations.

As well as the two foodbank sites, and the warehouse where donations are stored, a donation station operates at Grainger Market in Newcastle city centre, run by a supporter group connected to the city’s football club. Indirectly, I, Daniel Blake catalysed the formation of the NUFC Fans Foodbank and the Foodbank Histories project. In December 2016, several Newcastle United supporters approached NWEF’s then-CEO Mike Nixon, as one of their number, Bill Corcoran, remembers:

[Mike Nixon] described a huge organisation with warehouses, distribution points, corporate affiliations, facilities, and employees. Most alarmingly, he said that 50 percent of the food distributed here in Newcastle came from London! As Newcastle fans, we couldn’t endure that situation without trying to help. We launched the NUFC Fans Foodbank on 26th January 2017 in the Tyneside Irish Centre with a showing of I, Daniel Blake.36

When we watched it with about a hundred lads downstairs – and lasses, but mostly lads – I remember at the end facing a stunned silence. I mean, we’re not naïve young fools … we’re ordinary people, we see this city, but we didn’t know the depths to which people, this society, had sunk, and the desperation that people are living their lives under, so we were all really shocked, and a bit ashamed.37

Newcastle United provided the NUFC Fans Foodbank with written authority to use the club’s name, enabling volunteers to collect outside the football stadium. The average match-day collection is £875 and a tonne and a half of food.

Challenges of Coproduction

In 2018, Bill Corcoran approached Silvie Fisch at Northern Cultural Projects (NCP) and suggested producing something creative, possibly a play, to generate income for the foodbank. Silvie decided to draw upon her oral history background, and approached NWEF for permission to interview clients one-to-one. Interviews would explore their current situations, but also past experiences and hopes for the future, beyond their interaction with the foodbank.

Newcastle University Oral History Unit and Collective (OHUC) was launched in January 2018 with a mandate to engage both academic and community-based partners. When Silvie Fisch, on behalf of NCP, approached the OHUC in early 2018, they got involved immediately. OHUC also hosts monthly drop-in surgeries to support potential partnerships. Jack Hepworth’s involvement stemmed from a conversation at a drop-in. Alison Atkinson-Phillips had recently arrived in Newcastle as a research associate with OHUC and the university’s Research Innovation Fund supported her time. Professor of Oral History, Graham Smith, provided valuable advice and guidance.

Early conversations with the NUFC Fans group suggested a disconnect between the Trussell Trust’s national approach – which was perceived to encapsulate a ‘Dickensian’ model of charity – and a more nuanced on-the-ground approach to real experiences of food poverty. This dichotomy contrasted a self-perception of ‘Geordies’ – Newcastle locals – taking care of their own with an ingrained distrust of national institutions. This narrative also reflected the region’s economic marginalisation over several generations and possible differences between ‘religious’ and ‘secular’ approaches to poverty.

We identified three clusters of participants and assigned each interviewer a group. Silvie interviewed ‘clients’, Alison ‘volunteers’ and Jack ‘supporters’. Our approach both confirmed and complicated these narratives. The project model we developed drew on the ‘Triple Helix’ CATH project at Birmingham University, modified for a community sector approach.38 NWEF was involved in designing the project. We agreed a three-way memorandum of understanding that clearly stated the shared objectives of the project. Researchers would not simply mine participants for ‘data’. Participants gave permission for their interviews to be used in three ways:

- Through artistic and academic activities, to feed these histories and stories back to participants, to empower foodbank users and volunteers.

- To inform people about foodbank users’ circumstances and needs, with the aim of improving foodbank policies and service provision.

- To inspire future creative projects used to generate income for the Newcastle West End Foodbank.

Around the boundaries of these aims, the project deliberately allowed space for ‘messiness’ and for unforeseen outcomes.

Negotiating the bureaucracies of university ethics was an early challenge. Oral history projects usually involve assigning copyright to an archival body. In this case, how could a copyright agreement ensure that the material was used for the benefit of the foodbank or its clients? New General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) added to the complication. While we worked through the detail, we invited interviewees to give their interview and data – name, date of birth, and a way of contacting them – towards the project aims as per the project information sheet.

Researchers from the OHUC and NCP conducted oral history interviews with foodbank clients, volunteers, and supporters between March and November 2018. Some of our research involved ‘deep hanging out’: spending time with clients and volunteers, washing dishes or sharing meals. However, helping with tasks, and enjoying hearty two-course meals available on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, generated conversations which reflected on why the project mattered. Only a few interviews were held at the Venerable Bede, mainly due to the lack of a private space. This biased our interview sample, because those clients who attend the Liliah are mostly longer-term foodbank clients, whereas the Venerable Bede is the initial point of contact and sees a lot of new arrivals to the city. However, the Liliah interviews illuminated experiences of intergenerational poverty in Newcastle.

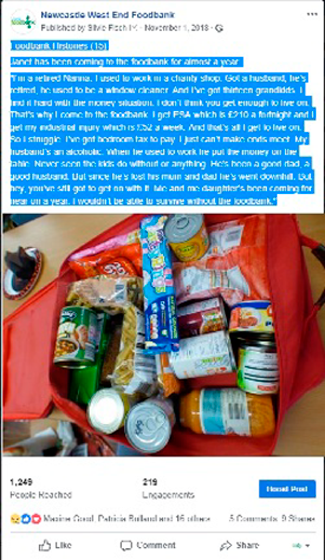

With admin access to NWEF’s Facebook page, we ‘storified’ interviews, including photographs of the interviewee or, if they preferred, another representation of their story, and writing up short narratives. For example, Foodbank Histories (15) contains an abridged transcript from Janet:

Foodbank Histories (15)

Janet has been coming to the foodbank for almost a year.

‘I’m a retired nanna. I used to work in a charity shop. Got a husband, he’s retired, he used to be a window cleaner. And I’ve got thirteen grandkids. I find it hard with the money situation. I don’t think you get enough to live on. That’s why I come to the foodbank. I get E[mployment and] S[upport] A[llowance] which is £210 a fortnight and I get my industrial injury which is £52 a week. And that’s all I get to live on. So I struggle. I’ve got bedroom tax to pay. I just can’t make ends meet. My husband’s an alcoholic. When he used to work he put the money on the table. Never seen the kids do without or anything. He’s been a good dad, a good husband. But since he’s lost his mum and dad he’s went downhill. But hey, you’ve still got to get on with it. Me and me daughter’s been coming for near on a year. I wouldn’t be able to survive without the foodbank’.39

Each post reached a minimum of 1,000 people and several received more than 100 engagements, with people sharing and commenting on posts. Some emphasised the ‘by the grace of God’ motif prevalent in earlier generations, but with a trenchant political edge:

You are doing exactly the right thing in highlighting the plight of our nation. Everyone is only two pay checks missing away from the debt spiral that brings destitution and causes people to be homeless … Food kitchens, street work with the homeless, with refugees, benefit advice etc. If what you can do well is write – write but always do something because this is going to be a long hard battle.40

Realising that the Facebook pages were aimed more at supporters than clients, we also created low-tech displays within the two foodbank collection centres. We printed Facebook posts and invited people to ‘comment’ on post-it notes. Much of this visible feedback affirmed volunteers’ work.

‘Foodbank Histories’ display at the Newcastle West End Foodbank Liliah Centre

How we Reported Joint Findings

The project navigated the challenge of raising income for the foodbank while conducting ‘research’. The causal link between government policies and food poverty, and in particular the impacts of Universal Credit, quickly emerged. For example, Deborah said of Universal Credit:

It’s horrible, being on that like. There’s a few people who I know who, just like me, are struggling like mad … When you first sign up, you have to go to an appointment, you have to do that appointment, go for another appointment … It can take up to six or eight weeks before your money starts coming in.

Claire, a foodbank client who had suffered long-term ill health, said similarly:

It got worse very recently because I attempted a phased return into work, so I was managing to do part-time work, and as a result I earned too much money. I earned about £900, so they work a month behind – so even though I got that two months ago, the fifteenth of last month, I got £399 from work, and they wouldn’t allow me any other help, so I can’t even pay my rent.

Volunteers repeated these narratives based on conversations they had with clients. Carole blamed long-term governmental failings:

Is the welfare system responsible for people in foodbanks? You bet it is – more than anything else. So when Theresa May says it’s not – yes it blooming well is, Mrs May, I’m afraid.

Our research also found that public discourse around poverty influenced foodbank clients, volunteers and supporters. Echoing previous oral history research, at times they internalised the dichotomy of the deserving and undeserving poor. Volunteers generally reflected on the foodbank making them more grateful for what they have got, sometimes falling back on ‘by the grace of God’, as a retiree, Imelda, states:

Anybody could be in need of something at any one time. Zero contract hours, people think oh it’s just people who are unemployed or whatever; it’s actually people that have jobs but they’ve just hit on hard times or they’re not guaranteed work or they’ve got a big bill to pay, something like that … It could be anybody in my family, so for the grace of God it’s not me.

While volunteers are generally very aware of the social stigma often attached to foodbanks, some also attributed food poverty chiefly to a perceived lack of education, or inability to budget. Shirley said that:

Some of the people who have come here, they’ve always been in a type of crisis. They haven’t been able to budget, they’ve always struggled. Doesn’t matter what you do for them – they’ll struggle because they don’t know how to do things to improve things.

Such ideas verge on victim-blaming, yet they stem from genuine concern about why some people seem able to cope while others cannot. A housewife who spoke about herself as ‘lucky’ for never having done paid work, Pat asked:

Why? Is there nobody else that can help them? I don’t know if it’s just because, obviously they don’t get enough money, because they wouldn’t be here if they did.

Some clients expressed negative views, differentiating themselves from ‘bad’ clients, ‘horrible people’ and ‘junkies’ who they criticised for using the foodbank unnecessarily. As Elisabeth said:

I don’t think people should take advantage the way they do. Cos some people take advantage, and I don’t think they should, I think it should just be for the ones that really need, that are struggling.

Our hope from the start had been that reflecting stories back to people could contest negative narratives, but we started to understand just how challenging that might be.

Public Outputs

In November 2018, UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty, Philip Alston, visited NWEF as part of a two-week visit to the UK. This was a special day for the NWEF. Volunteers, staff and the majority of clients valued the fact that Alston and his team had listened to their experiences. Some clients found the additional scrutiny challenging as a large entourage of reporters accompanied the UN delegation. We decided that sharing some of the interviews with Alston met the objectives to which participants had agreed, so provided a summary sheet for the UN’s use, which was well received. Alston said the interview extracts ‘helped me to understand much better the background to the establishment of the West End Foodbank which I had the privilege to visit and which does such impressive work’.41

Alison and Silvie also participated in the Alston visit by introducing the UN team to clients and volunteers who had shared their stories. It was gratifying to see clients who had previously been reticent about speaking their experiences aloud willing to join a group conversation. We believe this increased confidence came as a result of the positive scrutiny that Foodbank Histories had generated. After further permission had been sought, audio was also provided to The Guardian. A journalist who had covered Alston’s fact-finding tour, Robert Booth, used excerpts on a podcast.42

In November 2018, Foodbank Histories hosted an exhibition in Grainger Market in Newcastle city centre as part of the Being Human festival publicising humanities research. ‘Journeys of Food Insecurity’ featured large banners with extended quotes and sound clips from interviews, describing individual trajectories to the foodbank and experiences of living in the region. Dave Johns, who starred in Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake (2015) as a Newcastle joiner diagnosed unfit to work on health grounds, denied benefits and consequently plunged into poverty, officially opened the exhibition. Johns remarked on how the film had ‘changed the narrative in this country about people needing help … We shouldn’t have to have foodbanks, but we do’.43 The exhibition received extensive regional press coverage and provided a platform to publicise food insecurity in the area. At the opening event, Silvie Fisch described the project’s findings:

You see a lot of intergenerational poverty, generations of people deprived of a decent life. No matter how hard they try, they find it impossible to take control of their situation. People are confronted with a welfare system that should help them: instead it’s making their lives even harder.44

Launch of Foodbank Histories exhibition at Grainger Market

Visitors to the Grainger Market exhibition were invited to reflect and thirteen visitors completed a feedback form. For ten respondents, the exhibition had increased their awareness of food poverty in Newcastle ‘a lot’ with one describing the exhibition as a ‘vivid, honest and relevant contribution to public understanding of food poverty and its impact on the food bank’s clients and the volunteers who support them’. Another found the exhibition ‘absolutely staggering … I’m heartbroken by the comments. Huge revelation. I was not aware of the hardship’. Eight respondents said the event had encouraged them to find out ‘a lot’ more about food poverty. One visitor said the exhibition made them want to volunteer at the foodbank. Volunteers at the donation station reported a range of positive conversations with shoppers in the market who had spent a considerable amount of time reading the testimonies on display. NWEF also reported that donations had increased by one-third during the exhibition.

These positive responses contrasted with an exhibition at Newcastle’s Discovery Museum in 2015 which displayed a Trussell Trust family food parcel in its social welfare gallery. Having scrutinised around thirty visitors’ responses, the keeper of history for Tyne & Wear Archives and Museums (TWAM), Kylea Little reported that she was ‘surprised that many [visitors] thought the package, which includes no fresh items, was substantial enough to feed a family of three … The general lack of empathy was really shocking. People thought there was a lot of food in the package’. Early in 2016, Little also provided a summary of visitor reactions on the Museum’s blog in which she reported that: ‘Most people did not know that the Newcastle West End Foodbank was the busiest in the country but most people had heard of food banks generally … The display did not stimulate people to want to find out more’.45

Committed to exploring food poverty, TWAM went further. They commissioned a substantial arts installation from artists John and Karen Topping of REALTYNE. ‘Four Meals Away’ was displayed at the Discovery Museum for two weeks in February 2016. It presented a modestly equipped family kitchen, with fridge and cupboards empty. The exhibition received mainly positive feedback from visitors. Of eighty-five questionnaire respondents, seventy-three stated that they were either very or quite pleased that they came to the exhibition. Comments ranged from shock and sadness – ‘Shocked that this is the case in one of the richest countries in the world with a democratic system. Amazing how people can be left behind’ – to denouncing those responsible:

People in Britain having to use food banks when politicians get a subsidised bar in the Houses of Parliament, and recently a Conservative politician on approximately 70K a year reckons he can’t afford a house of his own, he and all Tories should try being on benefits or a ‘normal’ wage.

The artists had applied for the commission because they wanted to raise awareness of food poverty. But they were uneasy about their artwork acting as a kind of ‘information stand’. The exhibition also included a film, and the original plan had been to interview clients on camera, but not a single client agreed to be filmed. The artists, however, learned a good deal from the experience:

We produced hundreds of flyers telling people about the commission that were given out with food parcels … Foodbank staff asked people over the course of a month if they’d like to be interviewed and not one person came forward. We realised early in the project that people were ashamed to be seen in a foodbank… The last thing they wanted to do after such an ordeal was go through the emotional rollercoaster of telling two strangers ‘how it made them feel’ … We also realised that there were good reasons for people feeling the way they did and that we shouldn’t make that sort of film after all.46

There were several differences between the exhibitions at Discovery Museum and Grainger Market. The former came before I, Daniel Blake had been widely seen. The partnership approach to research also set Foodbank Histories apart. Rather than recruit participants through a flyer, ‘deep hanging out’ established rapport among regular clients. Interviewing foodbank volunteers and other supporters meant the research ‘gaze’ was not limited to clients and opened the possibility of hearing stories which overlapped these groups.

Foodbank Histories continues to develop. The exhibition banners have been shown at a range of foodbank, university, and public events. The team have reflected on findings and experiences in the OHUC blog, and at conferences and similar events. The Homeless History project included Foodbank Histories interviews in exhibitions across Newcastle in 2019. Homeless History had a compatible ethos, working with members of Newcastle’s Crisis Skylight to explore the complexity of experiences of homelessness in Newcastle over 150 years, including the overlapping issue of food poverty. Project lead Kristopher McKie stated: ‘the interviews collected by the Foodbank Histories project have been a rich and revealing resource for group members to think about food poverty in the twenty-first century and its effects on different people’.47

Foodbank Histories’ relationship with Live Youth Theatre is a further exciting development. Live Theatre produces and presents new plays, aiming to unlock young people’s potential. Artistic director Joe Douglas and youth theatre lead Paul James decided to make food poverty a long-term theme for young people. The twelve-minute performance ‘Fed Up’ was created from research around food poverty, including listening to our interviews and discussing the project with the researchers. A short version was first shown as a contribution to ‘City of Dreams’, a ten-year project aiming to improve the life chances of children and young people in Newcastle and Gateshead. The ‘real premier’ was delivered as part of the Youth Theatre’s twenty-first birthday celebrations in April 2019. With support from Newcastle University’s Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, the piece will next be taken beyond the theatre, as a campaigning and fundraising effort. A sound installation will introduce the performance, with original interview excerpts chosen by foodbank clients.

A small grant from the Newcastle University Social Justice Fund supported a short placement for Jack Hepworth within the Oral History Unit & Collective in February 2019. During the placement, Jack transcribed interviews and reported findings back to interviewees. Subsequently, these findings and feedback informed a report for NWEF trustees.

Analysing the findings, we heard foodbank volunteers articulating stories of empowerment, particularly when they spoke about work in the kitchen and the satisfaction of directly providing food to people. However, clients’ opportunities to tell similarly positive stories were limited in our initial phase. From this realisation developed Canny Cooks, a booklet with recipes and stories from, and co-produced by, foodbank clients. As well as providing a tangible outcome that finally meets the original objective of delivering a fundraising tool, it challenges prevailing myths – including those heard sometimes in the interviews – around foodbank users’ lack of knowledge and ability around food preparation. It also continued our engagement work with clients. By now the researchers had become familiar faces at the foodbank and most of the clients happily shared their favourite childhood recipes and food related memories with us. Clients also advised on the final product and suggested producing another booklet with child-friendly recipes.

Any charity provision led by the Church of England is bound to arouse suspicion for its association with the Victorian workhouse model famously depicted in Dickens’s Oliver Twist, and the associated categories of deserving and undeserving poor. This cultural framework continues to affect how foodbank users are perceived and perceive themselves. This debate connects to wider questions about foodbanks’ roles signposting to other help or bringing additional advisory and advocacy services in-house.48 Offering recipes for low budgets, the Eat Well Spend Less cookery course was rolled out across twenty-eight foodbanks by 2015.49 These developments are controversial, connecting to overarching debates about the social structures which perpetuate food poverty. Surveying foodbanks’ multiple agencies in 2016, Pat Caplan suggested that offering cookery classes and engaging nutritionists risked fortifying neoliberal portrayals of food poverty as a consequence of individual failure, remediable by education instead of redistribution.50 Canny Cooks offers a site of resistance, reminding readers that it is not food illiteracy that is clients’ problem, but a lack of money to buy the food they would like to eat.

Conclusion

Foodbank Histories began as a speculative venture between individuals interested in connecting social and historical justice with oral history. Although Newcastle West End Foodbank (cautiously) welcomed the initiative from Northern Cultural Projects and Newcastle University’s nascent Oral History Unit, inevitably it took time for the potential mutual benefits to the Foodbank to become apparent. Concomitantly, establishing trust and camaraderie between partner organisations required initiative from all parties and considerable groundwork.

Several months after the project began, the Foodbank Histories exhibition at Grainger Market in November 2018 provided vital impetus. Amplifying participants’ testimonies to wider publics – including considerable media attention – in this busy part of Newcastle invigorated the project, demonstrating the multivalent potential of these oral histories. The exhibition’s exposure empowered foodbank clients and volunteers, challenged public understanding of the issues of food poverty and stimulated a sense of civic identity which determined to challenge social injustice. As a threshold moment for the project, the exhibition attested the need for such partnership work to demonstrate its tangible benefits in the public arena.

Considerable investments of time on the ground in the foodbank sites, combined with clear, open communication between project partners, laid vital and sustainable foundations. Spending time at the foodbank, having conversations and energetically assisting volunteers all helped establish a rapport. Despite initial misgivings among participants and partners alike, as months passed, trust built. Among large sections of the community there was a palpable attitudinal shift towards wanting to participate in this developing project. Activities connected to the project have vitalised existing networks of community leaders in the foodbank and the local community more broadly. The project aims to support the foodbank however its trustees deem feasible. This involves assisting the foodbank financially, as well as empowering the community and helping to highlight and address socio-political issues. Reflecting interviewees’ stories back to them cut against hostile media narratives and individual stories of hardship to a more collective story of oppression and resistance. Involving participants at each stage of the project, we wanted to demonstrate to interviewees their ability to make change.

The conviction at the outset that the project should strive for more than merely short-term interventions underpins the plurality of outcomes from this ongoing work. Findings have instigated reflexive conversations in the foodbank. The feedback session at Benwell in March 2019 sparked discussions among clients and volunteers about how the foodbank operates, spanning praise and constructive criticism. A report for the foodbank’s CEO and trustees included recommendations both for internal operations and broader public-facing policy. Surveying the detail of this project, it must be recalled that Foodbank Histories documents one case among more than 1,000 foodbanks in the UK. Foodbank Histories has taken on a life of its own. An area for future development is to shift the emphasis to questions about how to achieve structural, long-term change. Newcastle West End Foodbank is a vibrant microcosm of a wider embattled community: one among many battling socio-political injustice.

Endnotes

1. Gertrude Himmelfarb, ‘The Idea of Poverty’, in History, vol 34, no 4, 1984.

2. Anne O’Brien, ‘“Kitchen Fragments and Garden Stuff”: Poor Law Discourse and Indigenous People in Early Colonial New South Wales’, in Australian Historical Studies, vol 39, no 2, 2008, pp150–66.

4. Fiona Ford and Robert Fraser, ‘Off to a Healthy Start: Food Support Benefits of Low-Income Women in Pregnancy’, in Peter Jackson (ed), Changing Families, Changing Food, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2009, pp19–34.

5. See Pat Thane, Unequal Britain: Equalities in Britain since 1945, Bloomsbury Publishing, London, 2010, for more historical context on poverty and its social implications in Britain in the post-war period.

6. House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee. Sustainable development goals in the UK follow-up: hunger, malnutrition and food insecurity in the UK. 2019 (online). Available: https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/environmental-audit-committee/ (accessed 29 May 2019).

7. Philip Alston, ‘Statement on Visit to the United Kingdom, by Professor Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights’. OHCHR, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23881&LangID=E (accessed 23 May 2019).

8. Ross Mackay, ‘Foodbank demand and supplementary assistance programmes: a research and policy case study’, Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, no 5, 1995.

9. Martin Caraher and Alessio Cavicchi, ‘Old crises on new plates or old plates for a new crises? Food banks and food insecurity’ in British Food Journal, vol 116, no 9, 2014.

10. See also ‘Gareth Streeter: Three Facts Which Suggest a Rise in Food Bank Use Is Not Just down to Universal Credit’, in Conservative Home (Online). Available https://www.conservativehome.com/platform/2019/01/gareth-streeter-three-facts-which-suggest-a-rise-in-food-bank-use-is-not-just-down-to-universal-credit.html (accessed 22 May 2019).

11. UK Parliament House of Lords, 2013, Food: Foodbanks (Online). Available: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201314/ldhansrd/text/130702-0001.htm (accessed 30 May 2019).

12. Steve Sweeney, ‘Generation zero: May’s legacy’, in Morning Star, 6 November 2017.

13. For example, in 2017, the Resolution Foundation predicted inequality between the highest and lowest ten percent of incomes – the so-called 90:10 ratio – would rise from 5.3 to 6 by 2020. Martin Thomas, ‘Labour manifesto: clawing back from the rich’, in Solidarity & Workers’ Liberty, vol 438, 16 May 2017.

15. https://www.trusselltrust.org/news-and-blog/latest-stats/end-year-stats/ (Accessed 28 May 2017.

16. Patrick Butler, ‘Child poverty in UK at highest level since 2010, official figures show’, Guardian, 16 March 2017.

17. Abhaya Jitendra, Emma Thorogood and Mia Hadfield-Spoor, Early Warnings: Universal Credit and Foodbanks (Trussell Trust, 2017).

18. For a qualitative study of the impacts of Universal Credit on claimants and staff, see Mandy Cheetham, Susanne Moffatt, Michelle Addison and Alice Wiseman, ‘Impact of Universal Credit in North East England: a qualitative study of claimants and support staff’ in BMJ Open, vol 9, no 7, 2019. Available: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/7/e029611 (accessed 16 July 2019).

19. May Bulman, ‘Food bank use in UK reaches highest rate on record as benefits fail to cover basic costs’, in Independent, 23 April 2018.

20. Jon Stone, ‘Theresa May refuses to rule out further disability benefit cuts’, in Independent, 10 May 2017.

21. The latest figures are dated 22 April 2019. http://www.foodaidnetwork.org.uk/mapping (accessed 23 May 2019).

22. Rachel Loopstra and Doireann Lalor, Financial insecurity, food insecurity, and disability: the profile of people receiving emergency food assistance from The Trussell Trust Foodbank Network in Britain (2017). Available: https://trusselltrust.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/06/OU_Report_final_01_08_online.pdf (accessed 2 June 2019).

23. John Hay, ‘A view from the front line, rising food bank use in an independent food bank’, in End Hunger UK. Available at http://endhungeruk.org/328-2/ (accessed 14 February 2019).

24. Rachel Loopstra, Jasmine Fledderjohann, Aaron Reeves & David Stuckler, ‘Impact of Welfare Benefit Sanctioning on Food Insecurity: A Dynamic Cross-Area Study of Food Bank Usage in the UK’, Journal of Social Policy, vol 47 no 3, 2018, pp437-57.

25. Kayleigh Garthwaite, Hunger Pains: Life Inside Foodbank Britain, Policy Press, Bristol, 2016.

26. D. Thompson, D. Smith and S. Cummins, ‘Understanding the health and wellbeing challenges of the food banking system: A qualitative study of food bank users, providers and referrers in London’, Social Science & Medicine, vol 211, 2018, pp97-98.

27. Hannah Lambie-Mumford, ‘“Every town should have one”: Emergency Food Banking in the UK’, Journal of Sociology and Politics, vol 42, 2013, p82.

28. T. Lummis and P. Thompson, Family Life and Work Experience Before 1918, 1870-1973. [data collection]. 7th Edition. UK Data Service, 2009. SN: 2000, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-2000-1.

30. Female airport worker, Families, Social Mobility and Ageing: A Multigenerational Approach, interview by Michele Abendstern, Reel-to-reel, 29 January 1986, C685/4.

31. Female warden, Families, Social Mobility and Ageing: A Multigenerational Approach, interview by Catherine Itzin, Reel-to-reel, 11 January 1986, C685/2.

32. Male, Families, Social Mobility and Ageing: A Multigenerational Approach, interview by Michele Abendstern, Reel-to-reel, 30 January 1986, C685/24.

33. For publications based on these two studies, see Graham Smith and Paula Nicolson, ‘Despair? Older Homeless Men’s Accounts of Their Emotional Trajectories’, Oral History, vol 39, no 1, 2011, pp30–42; Oscar Forero et al, ‘Institutional Dining Rooms: Food Ideologies and the Making of a Person’, in Peter Jackson (ed), Changing Families, Changing Food, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2009, pp226-45.

34. Included amongst those we are borrowing this term from are Monica D. Franklin et al, ‘Religious Fatalism and Its Association with Health Behaviors and Outcomes’, American Journal of Health Behaviour, 31, no 6, 2007, pp563-72. Frankilin et al point out that ‘Fatalism, the belief that an individual’s health outcome is predetermined or purposed by a higher power and not within the individual’s control, has been examined as an inhibitor to participation in health promotion programs and health care utilization’ (p563). From the mid-2000s onwards fears have regularly been expressed about a return to a public fatalism that sees homelessness as inevitable. See, for example, Lígia Teixeira, ‘How the Third Sector Can Convince People That Homelessness Can Be Tackled’, British Politics and Policy at LSE (blog), 20 September 2017, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/communicating-homelessness/.

35. Robert Booth, ‘“I’m scared to eat”: With the UN poverty tsar on Britain’s food bank frontline’, in Guardian, 9 November 2018.

36. Email to Silvie Fisch, 12 February 2018.

37. Interview Jack Hepworth/ Bill Corcoran 26 June 2018.

38. https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/node/195522.

39. https://www.facebook.com/NCLWestEndFoodbank/posts/1871306982991574 (Accessed 28 May 2019).

41. Email to Graham Smith, 25 February 2019.

42. https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2018/nov/19/poverty-in-britain-a-social-calamity (accessed 28 May 2019).

43. ‘I, Daniel Blake star Dave Johns says you can “always rely on the Toon” as he opens foodbank exhibition’, in Newcastle Chronicle, 16 November 2018.

45. Newcastle West End Foodbank | Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums Blog’ (accessed 1 March 2019) https://blog.twmuseums.org.uk/newcastle-west-end-foodbank/.

46. Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums, ‘Four Meals Away’ evaluation, 2016.

47. Email to Silvie Fisch, 4 March 2019.

49. Kayleigh Garthwaite, Hunger Pains: Life Inside Foodbank Britain, Policy Press, Bristol, 2016, p51.

50. Pat Caplan, ‘Big Society or Broken Society? Food Banks in the UK’, in Anthropology Today, vol 32 no 1, 2016, p8.