Research Article

Complexity in the context of information systems project management

Alexei Botchkarev1, Patrick Finnigan2

1 Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada

2 Instruments & Information, Toronto, Canada

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/opm.v2i1.4272

Abstract

Complexity is an inherent attribute of any project. The purpose of defining and documenting complexity is to enable a project team to foresee resulting challenges in a timely manner, and take steps to alleviate them.

The main contribution of this article is to present a systematic view of complexity in project management by identifying its key attributes and classifying complexity by these attributes. A “complexity taxonomy” is developed and discussed within three levels: the product, the project and the external environment.

Complexity types are described through simple real-life examples. Then a framework (tool) is developed for applying the notion of complexity as an early warning tool.

The article is intended for researchers in complexity, project management, information systems, technology solutions and business management, and also for information specialists, project managers, program managers, financial staff and technology directors.

Keywords: Complexity, project management, systems approach, information systems

© 2015 Alexei Botchkarev1, Patrick Finnigan2. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: Organisational Project Management 2015, 2(1): 15-34- http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/opm.v2i1.4272

Introduction

For five decades, complexity has been acknowledged as a critical project dimension (Baccarini 1996). Since the admitted failure of many large systems, including IT systems (Charette 2005; Standish 2013; Daniels and LaMarsh 2007), the causes have been widely studied. Such analyses have been conducted not only at the business level — where cost overrun losses can be astronomically high — but also in the failure of these systems to deliver their critically needed product and strategic objectives. There have been several well-funded and supported efforts to analyze and promote new methods of complex project management (US National Academy of Sciences Transportation Research Board 2012; Shane, Strong & Gransberg 2012; International Center for Complex Project Management Task Force 2013). These efforts are also driven by increased focus on overall project success, not just the “Iron Triangle” of function, cost and schedule (PMI 2013). A wider definition of project success (Howsawi et al. 2014) may also lead to new methods to ensure previously under-recognized implicit goals are attained as well.

The causes of complexity in projects are multiple. A good summary of the factors creating complexity is given by the International Centre for Complex Project Management Task Force:

The intrinsic complexity of projects, in part, is driven by political, social, technological and environmental issues, as well as including end user expectations which may change dramatically over the project life-cycle. Indeed, even minor projects can be complicated by hierarchical, siloed, and unnecessarily competitive organisational arrangements, wherein communication and trust can break down (ICCPM 2013, p.14).

This article will narrow the focus to a discussion of complex IT projects/systems and their implementation using new paradigms for project management, together with an overall definition of the success of such complex projects. Complexity for IT projects should be defined in a way that will help to focus on potential challenges specific to that field. This sharper focus on the underlying complexities in IT and their impact on a project will help project managers looking for more specific guidance.

First, the authors survey the literature on complexity. Then a framework for the understanding and analysis of the behaviour of such projects is presented. The framework identifies various aspects of complexity, with a process for mitigation of resulting challenges. Next, two projects the authors have managed are used as examples of how the proposed framework can be applied. Finally, possible extensions to the framework are presented, proposing calibration by users based on data from existing and future projects.

What is complexity?

Pigagaite, Silva & Hussein (2013), indicate there are “at least 31 definitions of complexity”. The term complexity is often used “because of the lack of a more appropriate expression describing the interrelated features which affect a project's life cycle” — in other words, as a catchphrase for many aspects of systems that we do not understand or are not able to manage.

Intuitively, synonyms for complexity are “intricate”, or “difficult”. Antonyms include “simple”, “well-understood” and “straightforward”. The term has different interpretations in different domains of knowledge, such as computational, systems and biological complexity (Bar-Yam 1997). In the business literature it is often “a state between order and chaos” (Kurtz and Snowden 2003). A complex system is one in which at least two parts interact dynamically to function as a whole (Serrat 2010).

To distinguish between complex and merely complicated: “Complicated systems have a large number of components with well-defined relations and roles, which are linear and fixed along time. Complex systems have usually a large number of components with non-linear relations and roles that evolve along time” (Olmedo 2010).

This reaches its zenith with software-driven appliances, where the large number of coded logic decisions and behaviours is hidden from our view or understanding, behave non-linearly (“why did this query take so long?”) and change regularly — hence surely a complex artefact. A good mental model to distinguish complexity from other system qualities is the Cynefin Framework – Table 1 (Kurz and Snowden, 2003).

| Complex | Knowable |

| Cause and effect are only coherent in retrospect and do not repeat Pattern management Perspective filters Complex adaptive systems Probe-Sense-Respond |

Cause and effect are separated over time and space Analytical/Reductionist Scenario planning Systems thinking Sense-Analyze-Respond |

| Chaos | Known |

| No cause-and-effect relationships are perceivable Stability-focused intervention Enactment tools Crisis management Act-Sense-Respond |

Cause-and-effect relationships are repeatable, perceivable, and predictable Legitimate best practice Standard operating procedures Process reengineering Sense-Categorize-Respond |

There are different concepts of complexity and its definition is bounded by other possible system states like knowability and chaos. The variety of definitions for complexity in the literature span many aspects of human cognition including:

- Our ability to mentally decompose the whole into understood parts (Albers 2011, Coulson, Barki and Pare 2013).

- Our ability to sensually detect (see, hear, etc.) or — by mental analogy to sensory experiences — deduce the function of the component parts (Bar-Yam 1997).

- Our ability to abstractly understand how the individual components work together to function as a more complex assembly. This is a well-accepted definition of complexity — the unpredictable interaction among component parts (Kurtz and Snowden 2003, ICCPM 2013).

- Our human physiological and psychological limitations to deal with multiple component parts. For example “the rule of seven” items in short-term memory, as with telephone numbers (Miller 1956, Simon 1974, Warfield 1988).

- Our lack of correct intuition of how physical systems with memory or energy storage behave, which can be “chaotic”. (Sussman 2007, Bar-Yam 1997).

- In the domain of IT projects and IT project management, project managers are being asked to deliver systems of unprecedented scope (functionality, number of users, 24x7 operation), that operate globally and are maintained across a rapidly evolving technological environment (e.g., versions of web browsers, databases, etc.), while remaining operational through what are sometimes decades of enhancement (Charette 2005, Geraldi, Maylor and Williams 2011, Gregory and Piccinini 2013, ICCPM 2013, Leukert et al. 2012).

It should be noted that complexity could be managed through decomposition, encapsulation and the definition of interfaces to the encapsulated component(s). Encapsulation into “black boxes” can reduce the complexity due to scale by packaging components together with reduced perceived complexity; a common example being the use of subroutines in computer programming that are called upon for repeated, discrete tasks/calculations. However, the potential resulting increase in the complexity of the interface to the newly encapsulated item can in itself become complex.

The traditional approach to complex IT projects and IT project management is based on size, cost and duration (PMI 2013). Size is somewhat controversial, as there can be many participants and participating stakeholder organizations for a project — but no complexity. A novel approach gaining popularity relies on the understanding of the project team as a temporary knowledge exchange group and social networks (Kurtz and Snowden 2003). Detailed discussions of the complexity of IT systems and projects can be found in Geraldi, Maylor and Williams (2011) and Gregory and Piccinini (2013).

Purpose and scope of the study

The purpose of this study is to analyze the notion of complexity in the context of a systems approach to project management and to develop a framework that can be used by project management practitioners and researchers to:

- Identify complexities

- Understand the challenges complexities present

- Deal with the challenges by implementing solutions that alleviate complexities.

The scope of this study includes considerations that are applicable to both private and public sectors at all levels: federal, provincial/state and municipal (Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat 2010, 2013a, 2013b; Haupt 2003; U.S. National Academy of Sciences Transportation Research Board 2012; Shane, Strong & Gransberg 2012), as well as using the method for critical thinking and inductive reasoning (Jackson 2011, McNabb 2013).

Most considerations of complexity are generic and applicable to any field. However, the focus here is on information systems/solutions. Information systems are understood as integrated complexes that include computers (hardware, software), means of communication, people, and business processes, e.g., enterprise resource planning (ERP), enterprise content management (ECM), business intelligence (BI) or customer relationship management (CRM) systems.

Literature review

The most popular document used by project managers and project team members is the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMI 2013). The notion of complexity is mentioned many times in the PMBoK 5th edition (PMI 2013). The term complexity is used 21 times. The adjective complex is used 16 times. The term complexity is mostly used to characterize a project: project complexity or complexity of a project. Often, the term is used in conjunction with project size (the term size is also not defined). Most often, complex is used in relation to a project, but it is used also as an adjective with products, services, results, processes, and procurements.

The PMBoK indicates that several project characteristics depend on complexity (among other attributes):

- The number of phases, the need for phases, and the degree of control applied (PMI 2013, p. 41).

- The project management plan's content (PMI 2013, p. 74).

- The size of the project charter (PMI 2013, p. 74).

- The applied level of change control (PMI 2013, p. 96).

- The level of detail for work packages (PMI 2013, p. 128).

- The cost and accuracy of bottom-up cost estimating (PMI 2013, p. 205).

- The need for formal or informal project performance appraisals (PMI 2013, p. 282).

- The number of stakeholders (PMI 2013, p. 394).

Despite frequent use, the term complexity is not formally defined in the PMBoK. Only one indicator or attribute of complexity has been identified. In the project communications chapter the number of potential communication channels or paths serves as an indicator of the complexity of a project's communications (PMI 2013, p. 292). The only recommendations provided to deal with complexity or to reduce complexity are generally to advocate iterative and incremental life cycles when an organization needs to manage changing objectives and scope (PMI 2013, p. 46). Based on the analysis of the usage of the term complexity in the PMBoK, it can be concluded that it is used to imply the scale of the project (where scale is different from the size of the project). Lack of clarity in the PMBoK regarding the nature of complexity and how to deal with it has a negative impact on practitioners.

In the academic literature, there are two notions prevailing to describe project complexity. These notions were stated by Baccarini in arguably the first review paper covering research results on project complexity from the late 1960s to mid-1990s (Baccarini 1996). The first notion stems from systems theory that project complexity can be defined as consisting of many varied interrelated parts. The second notion acknowledges that difficulty (complicatedness, intricacy) is also used to characterize complexity. However, this attribute was considered subjective and unreliable and in some later publications was separated from complexity, thus narrowing the scope of the phenomenon (Williamson, 2011). Baccarini's (1996) approach is to explicitly define complexity as the numbers of tasks, levels, inputs, etc. These numbers are objective and measurable. However, by dismissing complicatedness, these scale attribute numbers alone tend to miss certain other inherent aspects of complexity. Relying only on the numbers creates a risk of focusing only on the size.

The paper by Leukert et al. (2012) provides an example of characterizing complexity largely by numeric attributes, e.g., number of users, number of use cases, number of function points, number of user departments, number of infrastructure products (databases, operating systems), number of infrastructure services, number of infrastructure requirements. Pich, Loch and Meyer (2002) support a more generic position that complexity stems from the interaction of too many variables so that project teams are unable to evaluate the effects of individual actions.

When project management practitioners are asked an open-ended question about the main source of complexity, their answer is “the main challenge is the people” (Pigagaite, Silva & Hussein 2013). That testifies to the fact that practitioners’ understanding of complexity goes beyond a system-only vision and includes complicatedness. Finally, Coulon, Barki and Pare (2013) present complexity as resulting from unexpected events.

It must be acknowledged that there have been many philosophical discussions on the nature of complexity, chaos, and the knowledge-based aspects (“know-ability”, “un-know-ability”) of so-called “complex”, “chaotic”, “self-organizing”, and “non-linear” systems, as well as risk, and uncertainty (Horgan 1995; Sussman 2000; Sussman 2007; Foster, Kay and Roe 2001; Kurtz and Snowden 2003). This discussion spans many research areas such as biology (Solé and Goodwin 2000; Loughlin 2012), Geology (complex systems in the geosciences 2010), electronics (Axelsson 2002), and human organizations (Bar Yan 1996) including healthcare (Haupt 2003; Atun 2012). Many of the insights from this research have yet to be applied to the domain of IT projects, or be considered in our proposed complexity framework.

Table 2 shows complexity attributes from a variety of sources with an emphasis on business (i.e. project management), engineering and IT project complexity, across all the life cycle phases: planning, design, creation, and operation and maintenance.

| Complexity Attribute | Reference |

| Structural (Scale) | Baccarini 1996; Xia and Lee 2004;Turner and Müller 2006 Remington and Pollack 2007;Geraldi, Maylor & Williams 2011; Albers 2011; PMBOK 2013; Gregory and Piccinini 2013; |

|

Leukert et al 2012 |

|

Leukert et al 2012 |

|

Leukert et al 2012; Turner and Müller 2006 |

|

Gregory and Piccinini 2013 |

|

Leukert et al 2012; Albers 2011 |

|

Leukert et al 2012 |

|

Pigagaite, Silva & Hussein 2013 |

|

Leukert et al 2012; Albers 2011 |

|

Leukert et al 2012 |

|

Leukert et al 2012 |

| Technological | Baccarini 1996; Tatikonda and Rosenthal 2000; Remington and Pollack 2007;Gregory and Piccinini 2013 |

|

Kim and Wilemon 2003; Pigagaite, Silva & Hussein 2013 |

|

Pigagaite, Silva & Hussein 2013 |

| Organizational | Baccarini 1996; Thomas and Mengel 2008; Gregory and Piccinini 2013 |

| Project Management | Pich, Loch & Meyer 2002; Thomas and Mengel 2008 |

|

Turner and Müller 2006; Müller, Geraldi & Turner 2007 |

|

Pigagaite, Silva & Hussein 2013 |

|

Pigagaite, Silva & Hussein 2013 |

|

Müller, Geraldi & Turner 2007 |

|

Ramasesh and Browning 2014 |

|

Ramasesh and Browning 2014 |

| Uncertainty | Pich, Loch & Meyer 2002; Atkinson, Crawford & Ward 2006; Geraldi, Maylor & Williams 2011; Pigagaite, Silva & Hussein 2013 |

|

Kurtz and Snowdon 2003; Gruhn and Laue 2006 |

|

Turner and Cochrane 1993; Williams 1999 |

|

Nolan, Abrahão, Clements & Pickard 2011; Michalik, Keutel & Mellis 2014 |

|

Gul and Khan 2011 |

|

Gul and Khan 2011 |

| Ambiguity (lack of clarity) | Pich, Loch & Meyer 2002; Gregory and Piccinini 2013 |

| End-Users | |

|

Pigagaite, Silva & Hussein 2013 |

| Dynamics | Xia and Lee 2004; Geraldi, Maylor & Williams 2011; Gregory and Piccinini 2013 |

| Pace (temporal dimension) | Dvir, Sadeh & Malach-Pines 2006; Geraldi, Maylor & Williams 2011 |

| Constraints of the objectives, resources or environment | Remington and Pollack 2007;Dunović, Radujković & Škreb 2014 |

| Socio-political | Geraldi, Maylor & Williams 2011; Klein 2012 |

|

Turner and Müller 2006; Maylor, Vidgen & Carver 2008 |

|

Pigagaite, Silva & Hussein 2013 |

|

Jiang, Klein, Wu & Liang 2009 |

|

Browaeys and Baets 2003; Klein 2012; Ochieng, Price, Ruan, Egbu & Moore 2013 |

|

Geraldiand Adlbrecht 2007; Remington and Pollack 2007; Geraldi, Maylor & Williams 2011 |

Complexity framework

Complexity is an inherent attribute of any project, (even seemingly simple projects are just those with low complexity). Our intention therefore is to define and document complexity in a way that will facilitate the building of an early warning tool allowing project managers and teams to focus on high-risk areas and aspects of the project, in order to prevent and alleviate future issues/problems that are complexity-related.

It has been observed that complex projects should be described and investigated as systems-of-systems (SoS) (Gorod, Sauser & Boardman 2008, Zhu & Mostafavi 2014), and earlier by Flood and Jackson (1991). As the SoS principles, practices and methodology are still being developed, there are no universally accepted approaches or definition.

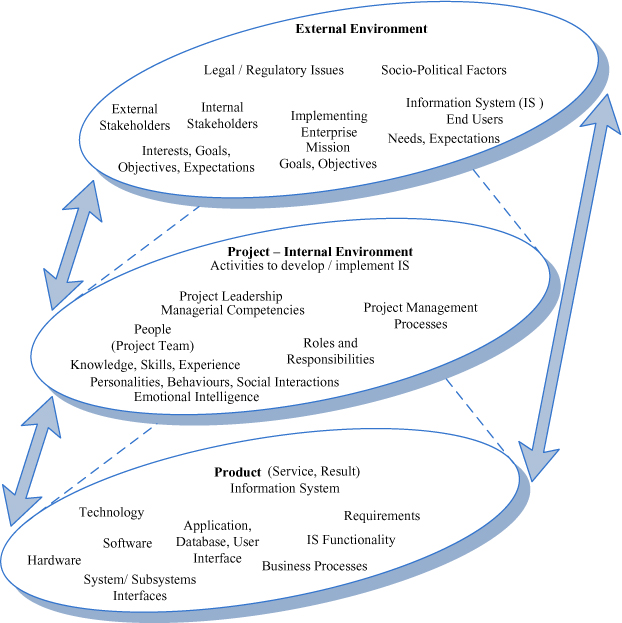

The SoS configuration we chose for our complexity framework is illustrated in Figure 1. It shows three interrelated systems. The first system, External Environment, includes: stakeholders internal and external to the company and project; the enterprise with its mission, goals, and objectives; and end-users of the information system. There are two main reasons for identifying External Environment as a separate system in our SoS-based complexity framework: primarily, its importance for the success of the project; secondarily, lack of control from the project team over elements of this system. The second system in the framework, the Project or Internal Environment, includes activities undertaken to develop or implement an information system, as well as the project team and project processes. Finally, the third system is the Product or information system that is being implemented and all of its components or subsystems such as software, hardware, etc.

Figure 1. Project as a system of systems for complexity mapping

These three interrelated systems in the complexity framework are used for grouping/clustering complexity attributes. Depending on the specifics of the project, each of these systems or their component parts may be further decomposed, e.g., if the project has extensive purchasing activities, acquisition may be viewed as a separate system within the complexity framework.

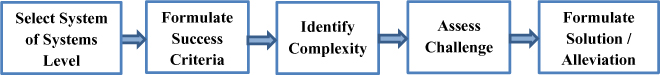

A process for managing all the specific and interacting aspects of complexity is shown in Figure 2. The intent of Figure 2 is to visualize the suggested approach/process of documenting and dealing with complexities. This approach identifies the types of complexity in the project, but also reveals the challenges associated with specific complexities and suggests practical steps to alleviate or reduce potential consequences caused by these complexities. The process promotes a practitioner-oriented approach. For this reason, a very simple and concise construct has been chosen. Complexity attributes are defined in relation to the criteria of project success and project failure factors (e.g. Hussein 2013; Yeo 2002). The benefit of the suggested process is that a practitioner is offered a tool to systematically approach complexity issues on a very wide range of IS projects. The second aspect, obviously, is that complexity issues will not be automatically resolved by applying this process. The result will depend on how effective a practitioner is in a specific situation in identifying a complexity, understanding the challenge and conceiving a solution. Each sub-step in the process is not trivial.

Figure 2. Process for IS project complexity management

The literature review showed that researchers acknowledge the existence of multiple attributes of complexity (summarized in Table 2). It also provided evidence that the complexity body of knowledge is far from being complete or even coming close to saturation — each new published article identifies additional attributes of complexity. Moreover, there is no commonly accepted generalized theoretical complexity framework that would systematically accommodate all known complexity attributes and provide space and directions for incorporating new ones. For the reasons mentioned above, arguably most research papers offer “partial solutions” — valid for certain complexity aspects or project management situations. This article is no exception.

The following criteria were used to select complexity attributes for the framework presented:

- Following a systems approach to decomposing, selecting and grouping attributes.

- Utilizing a broad understanding of the notion of complexity tending to include complicatedness as well.

- Adopting a pragmatic approach of selecting attributes that could be used in project management practice (not only in academic theoretical constructs).

- Recognizing the applicability of the attributes to the information systems subject area.

- Preferential selection of attributes that are common, well understood and present in IS development and implementation projects.

- Highlighting attributes that may have potentially fatal consequences to the project.

Certain complexity attributes (e.g., uncertainty, ambiguity, change, dynamics, risks), commonly referred to as complexities, were not included in the framework (at least at this point) for two reasons. First, these independent notions have been explored extensively in the academic literature, and there are well-defined tools and practices to deal with them; often these notions are studied without direct relation to complexity. Second, these notions constitute what could be called “vertical” attributes in relation to our SoS project model — each of these attributes can exist at each and any level of the suggested SoS structure (e.g., uncertainty of the project goals, uncertainty of the responsibilities, uncertainty of the requirements). This study focuses on the attributes specific to individual levels of the model for presentation clarity. This does not mean that these attributes do not fit into the suggested framework or cannot be handled with the suggested approach. They can be handled by the framework in the same way as the other attributes.

The initial version of the completed complexity framework is presented in Table 3. When assessing the challenge presented by a complexity attribute, the focus should be on how project success could be compromised by the complexity, and how project failure may occur. Although the table is self-explanatory, special attention should be paid to the following points: for the External Environment, the two complexity attributes related to stakeholders and end-users merit some discussion. Commonly, researchers state that complexity of a project increases with the number of stakeholders or end-users. However, the root cause of the stakeholder-related complexities stems from when there are contradictory expectations/interests or diversity of goals. This complexity attribute is stakeholder non-alignment. It is this non-alignment (which may develop gradually or arise unexpectedly) that the project manager should be carefully monitoring and mitigating. The number of stakeholders by itself may not present a challenge, if their interests and expectations are aligned. But even with just two or three non-aligned stakeholders, the project's overall success may be at risk if this particular issue is not remediated.

Note: The framework presented here is not intended to be comprehensive at this point.

Application of the framework

Two project examples illustrate applicability of the proposed framework. The examples are based on real projects. However, they were de-identified to avoid proprietary and privacy issues.

Example 1. Project with a combination of complexity attributes

Context

A large organization was involved in implementation of a CRM system. This enterprise-wide project included eight business departments, as well as CEO and PMO offices. A total staff of over 400 people was performing three distinct types of operations: information management, investment control and industry liaison.

Complexity

The project had a combination of stakeholder non-alignment and user incongruity complexities.

Challenges

A variety of the interests of diverse business departments led to a power struggle between the core stakeholders — department heads — regarding the scope and timelines of the project. Diversity of end-user needs complicated the consensus on the initial functionalities.

Solution/Alleviation

Early and forthright assessments of stakeholder interests, expectations and end-user needs were not performed. No stakeholder agreement was negotiated.

Result

This project suffered delays. Executive support was lost. The project was suspended. Neglected complexities led to suspension of a project which, all stakeholders agreed, could have been very profitable for the organization.

Example 2: Project with solution challenge

Context

A large multinational computer software company has the common situation of a database product that runs on a number of computer platforms (i.e., large servers, intermediate branch-size servers, and workstations). Customers have come to expect multiplatform capability, as well as that the product behaves functionally the same (returns the same results) across all platforms. The challenge for this manufacturer is to introduce new versions of the database with enhanced functions that will generate new licensing revenue, as well as significantly enhance performance to compete against other products.

Complexity

The project has a solution challenge, which is to exhibit uniform function (viz., return the same results from queries) on all platforms, combined with complexities of scale. In fact, this family of products (brand) exhibits all the complexity attributes shown in Table 2, as well as those identified below.

- Tens of thousands of customers (scale)

- End-user history: there are at least seven previous versions running in production

- Throughput of millions of transactions per hour in typical customer applications (scale)

- Multiple languages (scale): the product needs to display and store information in most languages used worldwide, using multiple character sets, written left to right and right to left etc.

- Multiple platforms (technological and scale complexity): quality control testing is required with a variety of new and old hardware platforms and operating systems

- Project management of multisite development: as is usual in a multinational software supplier

- Technological inherent complexity — of a code base of tens of millions of lines of code evolved over many years.

- Constraints: of the multiple computing environments in which it runs

- Socio-political interaction across stakeholders, diversity of expectations (new functional requirements), development within a large multi-national corporate environment with competition for resources

Challenges

Organizing the project management team by function is difficult because of the specialized knowledge requirements for each of the different platforms/releases.

Product management needs to compete for resources with other profitable products in the manufacturer's portfolio. The largely environmental complexities of this key component of many customers’ larger IT systems need to be continually emphasized to management, in order that appropriate resources are available for new releases of the product. By showing how critical this product is in many customer environments, customer account executives can see how dependent customers are on this component. By also showing new requirements (for example EU and ISO standards, privacy legislation etc.), it can easily be demonstrated how the complexity of a new release of the product is targeted at specific requirements. Resources, risk mitigation, etc. can be planned accordingly.

Solution/Alleviation

Project management in this example is best handled as “portfolio management”. This is most effective when a management champion is appointed for each of the product versions, whether a new or historical release (in production), or running on a specific platform. Portfolio management is used to prioritize new customer requirements and assess the impact across specific product, process and environment combinations. For example, it may not be necessary to offer all features on all platforms. The various aspects of the product, such as performance, are also assigned technical champions who plan for and secure resources to ensure their particular aspect of product complexity meets the assigned metrics. Assigning the right technical and other leaders to specific aspects of the portfolio complexity ensures the success of that aspect.

A further helpful tool for this product portfolio is the customer-sanctioned logs of complex transactions against databases. By capturing as much environmental information as possible, as well as the sequence of transactions (search for this information, store that information, etc.), along with timestamps to unravel the sequence of events, it is possible to diagnose and repair very complex technical issues (i.e., unexpected results or delays). It is quite viable for a multiplatform software product to evolve and thrive even in face of the multiple dimensions of complexity.

Discussion

This study focused on identifying individual attributes of complexity. However, the authors acknowledge that real-life projects are prone not only to a single complexity or several individual attributes of different types, but also to combinations of complexities with unpredictable integral impact. Further, interactions with other projects and shared systems can come into play. The proposed framework is therefore not a suggestion to treat projects as standalone entities.

It is true, though, that when practitioners undertake assessment of a project, they inevitably take a snapshot of the complexities, risks, uncertainties, state of interactions etc., as documenting a moving target does not seem realistic. This snapshot may look like a standalone entity, although potential dynamics of the environments and interactions are taken into account. Users of the framework should identify each of the complexity attributes shown, and analyze how they interact within their own specific projects. Once identified, these complexities can be properly managed.

To obtain senior management support, thorough documenting and characterizing of potential project complexities is important. Explaining potential complexities — and the challenges they create — can help secure executive buy-in to specific complexity mitigation strategies at the project planning stage. For complexities that cannot be eliminated, this strategy can secure funding to implement appropriate risk mitigation strategies based on proven, detailed complexity drivers.

Over time, careful tracking of complexity attributes across multiple projects will allow users to develop rules of thumb based on various severities of complexity and project management heuristics. The set of complexity attributes in the framework can also be extended through increased project experience and overarching project mandates such as ISO quality. With respect to IT projects in particular, customer data privacy will increasingly become a source of complexity.

Future research will focus on discovering additional attributes to enrich the complexity framework and on conducting quantitative evaluation of the attributes by involving project management practitioners. Also, further investigation can explore how the framework can be applied to various stages of projects across a wide range of project scale and for a variety of project methodologies in the context of unique organizational and technical environments. It is recommended that the next edition of the PMBoK should elaborate on complexity and processes to deal with it.

Conclusions

Recognizing complexities early on is critical to successful project management. The contribution of this study includes development of a new complexity reduction framework. To apply it to a specific project, a system of systems approach is first used to identify complexity attributes. Resultant challenge(s) are then mapped, followed by documenting and planning for a solution or alleviation of these challenges. The framework is applicable to project management across all domains, although this article discusses it in the context of information systems. Even though the framework is new, it has been validated in this paper against two projects. The authors welcome use of the framework by the PM practitioner/research community for its further elaboration.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the editing of this paper by Martha Finnigan, retired Professor and Coordinator of the Communications program in the School of Business, IT, and Management (BITM) at Durham College in Ontario, Canada.

References

Albers, M. (2011). Comprehending complexity: Solutions for understanding the usability of information. In M. Albers & B. Still (Eds.), Usability of complex information systems: evaluation of user interaction (pp. 1-16). Boca Raton FL: CRC Press

Atkinson, R., Crawford, L., & Ward, S. (2006). Fundamental uncertainties in projects and the scope of project management. International journal of project management, 24(8), 687-698. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2006.09.011

Atun, R. (2012). Health systems, systems thinking and innovation, Health Policy and Planning Vol. 27:iv4-iv8 doi:10.1093/heapol/czs088. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czs088

Axelsson, J. (2002), Complexity Issues in System Development: Examples from Automotive Electronics, IEEE International Workshop on Factory Communication Systems, Vasteras, Sweden, Aug. 29, 2002.

Baccarini, D. (1996). The concept of project complexity—a review. International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 201-204. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0263-7863(95)00093-3

Bar-Yam, Y. (1997). Dynamics of complex systems (Vol. 213). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Browaeys, M. J., & Baets, W. (2003). Cultural complexity: a new epistemological perspective. Learning Organization, The, 10(6), 332-339. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09696470310497168

Charette, R. (2005). Why software fails [software failure]. IEEE Spectr. Vol. 42, No. 9, pp. 42-49. DOI=10.1109/MSPEC.2005.1502528. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/MSPEC.2005.1502528

Complex Systems in the Geosciences, Developing Student Understanding of, (2010). Conference held April 18-20, 2010 at Carleton College, Northfield, MN. (http://serc.carleton.edu)

Coulon, T., Barki, H., & Pare, G. (2013). Conceptualizing unexpected events in IT projects. The 34th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS)

Daniels, C.B. and LaMarsh, W.J. (2007). Complexity as a Cause of Failure in Information Technology Project Management. System of Systems Engineering, 2007. SoSE ‘07. IEEE International Conference on, Vol., no., pp.1-7, 16-18 April 2007. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/SYSOSE.2007.4304225 URL: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=4304225&isnumber=4304211

Dunović, I. B., Radujković, M., & Škreb, K. A. (2014). Towards a New Model of Complexity–The Case of Large Infrastructure Projects. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 119, pp. 730-738. Elsevier ScienceDirect. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.082

Dvir, D., Sadeh, A. and Malach-Pines, A. (2006), Projects and project managers: the relationship between project manager's personality, project, project types, and project success. Project Management Journal, Vol. 37, No. 5, pp. 36-48.

Flood, R.L.and Jackson, M.C. (1991). Creative Problem Solving: Total Systems Intervention. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Foster, J., Kay, J., & Roe, P. (2001). Teaching complexity and systems thinking to engineers. 4th UICEE Annual Conference on Engineering Education, Bangkok, Thailand, 7-10 February 2001.

Geraldi, J. and Adlbrecht, G. (2007), On faith, fact and interaction in projects. Project Management Journal, Vol. 38 No. 1, pp. 32-43.

Geraldi, J., Maylor, H., Williams, T. (2011),"Now, let's make it really complex (complicated): A systematic review of the complexities of projects", International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 31 Issue: 9, pp. 966 – 990. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01443571111165848

Gorod, A., Sauser, B. J., & Boardman, J. T. (2008). System-of-Systems Engineering Management: A Review of Modern History and a Path Forward. IEEE Systems Journal, Vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 484-499. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2008.2007163

Gregory, R.W. and Piccinini E. (2013), The Nature Of Complexity In IS Projects And Programmes. 21st European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS 2013) Completed Research. Paper 96. http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2013_cr/96

Gruhn, Volker, and Ralf Laue (2006) "Complexity metrics for business process models." 9th international conference on business information systems (BIS 2006). Vol. 85.

Gul, S., & Khan, S. (2011). Revisiting Project Complexity: Towards a Comprehensive Model of Project Complexity. In 2nd International Conference on Construction and Project Management. Singapore, IACSIT Press. IPEDR (Vol. 15, pp. 148-155).

Haupt, J. (2003). Applying Complexity Science to Health and Healthcare,

Horgan, J. (1995). From complexity to perplexity, Scientific American, June 1995, Vol. 272, Issue 6, pp. 104-110.

Howsawi, E., Eager, D., Bagia R., Niebecker, K. (2014). The four-level project success framework: application and assessment. Organizational Project Management, Vol. 1, No. 1. http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/.v1i0.3865

Hussein, B. A. (2013). Factors influencing project success criteria. In Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems (IDAACS), 2013 IEEE 7th International Conference on, Vol. 2, pp. 566-571. IEEE. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/idaacs.2013.6662988

ICCPM. (2013). Complex Project Management Global Perspectives and the Strategic Agenda to 2025.The Task Force Report. International Centre for Complex Project Management, Kingston, Australia.Gap – Globalaccesspartnersptyltdhttps://iccpm.com/sites/default/files/kcfinder/files/Resources/ICCPM%20Resources/ICCPM_The%20Task%20Force%20Report_proof%20only_low%20res.pdf

Jackson, S. (2011). Research methods and statistics: A critical thinking approach. Cengage Learning.

Jiang, J. J., Klein, G., Wu, S. P., & Liang, T. P. (2009). The relation of requirements uncertainty and stakeholder perception gaps to project management performance. Journal of Systems and Software, 82(5), 801-808. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2008.11.833

Kim, J., & Wilemon, D. (2003). Sources and assessment of complexity in NPD projects. R&D Management, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 15-30. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9310.00278

Klein, L. (2012). Social Complexity in Project Management. Berlin: SEgroup. http://systemic-excellence-group.de/sites/default/files/klein_2012_scpm.pdf

Kurtz, C. F., & Snowden, D. J. (2003). The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world. IBM systems journal, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 462-483. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1147/sj.423.0462

Leukert, P., Vollmer, A., Alliet, B., & Reeves, M. (2012). IT Complexity metrics–How do you measure up? The Capco Institute Journal of Financial Transformation, No. 34, pp. 11-15. https://capco.com/sites/all/files/restricted/journal34-article-2.pdf

Loughlin, P., (2012). BIOENG 1320: Biological Signals and Systems. Swanson School of Engineering, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 http://www.engineering.pitt.edu/courses/BIOENG1320/

Maylor, H., Vidgen, R. and Carver, S. (2008), Managerial complexity in project-based operations: a ground model and its implications for practice. Project Management Journal, Vol. 39, pp. 15-26. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pmj.20057

McNabb, D. E. (2013). Research methods in public administration and nonprofit management: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. ME Sharpe.

Michalik, B., Keutel, M., & Mellis, W. (2014, January). Coping with Requirements Uncertainty--A Case Study of an Enterprise-Wide Record Management System. In System Sciences (HICSS), 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on (pp. 4024-4033). IEEE.

Miller, G.A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limitations on our capacity for processing information. Psychology Review 63(2), pp. 81-97. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0043158

Nolan, A. J., Abrahão, S., Clements, P. C., & Pickard, A. (2011, August). Requirements Uncertainty in a Software Product Line. In Software Product Line Conference (SPLC), 2011 15th International (pp. 223-231). IEEE. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/splc.2011.13

Müller, R., Geraldi, J. G., & Turner, J. R. (2007). Linking complexity and leadership competences of project managers. In Proceedings of IRNOP VIII (International Research Network for Organizing by Projects) Conference. Brighton, UK, CD-ROM. Universal Publishers. http://centrim.mis.brighton.ac.uk/events/irnop-2007/papers-1/Mueller%20et%20al.pdf

Ochieng, E. G., Price, A. D. F., Ruan, X., Egbu, C. O., & Moore, D. (2013). The effect of cross-cultural uncertainty and complexity within multicultural construction teams. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 20(3), 307-324. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09699981311324023

Olmedo, E., (2010). Complexity and chaos in organisations: complex management, Int. J. Complexity in Leadership and Management, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 72-82. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/ijclm.2010.035790

Pich, M. T., Loch, C. H., & Meyer, A. D. (2002). On uncertainty, ambiguity, and complexity in project management. Management science, 48(8), 1008-1023. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.48.8.1008.163

Pigagaite, G., Silva, P. P., & Hussein, B. A. (2013, November). Sources of Complexities in New Product and Process Development Projects. In International Workshop of Advanced Manufacturing and Automation (IWAMA 2013). Akademika forlag.

PMI. (2013) A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK Guide), Fifth Edition. Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute.

Ramasesh, R. V., & Browning, T. R. (2014). A conceptual framework for tackling knowable unknown unknowns in project management. Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 32, No 4, pp. 190-204. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2014.03.003

Remington, K., & Pollack, J. (2007). Tools for complex projects. Gower Publishing, Ltd..

Report of the conference Complexity Science in Practice: Understanding and Acting To Improve Health and Healthcare. (2003). Plexus Institute and Mayo School of Continuing Medical Education and Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota. http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.plexusinstitute.org/resource/collection/6528ED29-9907-4BC7-8D00-8DC907679FED/11261_Plexus_Summit_report_Health_Healthcare.pdf

Serrat, O. (2009). Understanding Complexity, Knowledge Solutions, Vol. 66, pp. 1-8. Asian Development Bank, November 2009.

Shane, J. S., Strong, K. C., & Gransberg, D. D. (2012). Project Management Strategies for Complex Projects (No. SHRP 2 Renewal Project R10).

Simon, H.A. (1974). How big is a chunk? Science 183, pp. 482-488. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.183.4124.482

Solé, R., and Goodwin, B., (2000). Signs of Life: How Complexity Pervades Biology, Basic Books, NY.

Standish Group. (2013). The Chaos Manifesto. The Standish Group International. http://versionone.com/assets/img/files/ChaosManifesto2013.pdf

Sussman, J. M. (2000). Ideas on Complexity in Systems--Twenty Views. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Internet resource, http://web.mit.edu/esd, 83.

Sussman, J.M., (2007) Collected Views on Complexity in Systems, Course materials for ESD.04J Frameworks and Models in Engineering Systems. MIT OpenCourseWare (http://ocw.mit.edu), Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Tatikonda, M. V., & Rosenthal, S. R. (2000). Technology novelty, project complexity, and product development project execution success: a deeper look at task uncertainty in product innovation. Engineering Management, IEEE Transactions on, Vol. 47, No. 1, pp. 74-87. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/17.820727

Thomas, J., & Mengel, T. (2008). Preparing project managers to deal with complexity–Advanced project management education. International Journal of Project Management, 26(3), 304-315. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.01.001

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. (2010). Standard for Project Complexity and Risk. http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=21261§ion=text

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. (2013a) Guide to Using the Project Complexity and Risk Assessment Tool. Version 1.3. http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pm-gp/doc/pcrag-ecrpg/pcrag-ecrpgpr-eng.asp?format=print

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. (2013b). Project Complexity and Risk Assessment Tool. Version 1.4. Date Modified: 2013-05-01. http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pm-gp/doc/pcra-ecrp/pcra-ecrp-eng.asp

Turner, J. R. and Müller, R. (2006) Choosing appropriate project managers: matching their leadership style to the type of project. Newtown Square, U.S.: Project Management Institute. 117p. ISBN 9781933890203

Turner, J. R., & Cochrane, R. A. (1993). Goals-and-methods matrix: coping with projects with ill-defined goals and/or methods of achieving them. International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 93-102. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0263-7863(93)90017-H

United States National Academy of Sciences (2012), Guidebook: Project Management Strategies for Complex Projects, Transportation Research Board, Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP2)

Warfield, J. N. (1988). The magical number three – plus or minus zero, Cybernetics and Systems 19, pp. 339-358. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01969728808902173

Williams, T. M. (1999). The need for new paradigms for complex projects. International journal of project management, Vol. 17, No. 5, pp. 269-273. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(98)00047-7

Williamson, D. J. (2011). A Correlational Study Assessing the Relationships among Information Technology Project Complexity, Project Complication, and Project Success. PhD Thesis.Capella University. ProQuest LLC.

Xia, W., & Lee, G. (2004). Grasping the complexity of IS development projects. Communications of the ACM, Vol. 47, No. 5, pp. 68-74. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/986213.986215

Yeo, K. T. (2002). Critical failure factors in information system projects. International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 241-246. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(01)00075-8

Zhu, J., & Mostafavi, A. (2014, March). Towards a new paradigm for management of complex engineering projects: A system-of-systems framework. In Systems Conference (SysCon), 2014 8th Annual IEEE, pp. 213-219. IEEE. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/syscon.2014.6819260

About the authors

Alexei Botchkarev is a Senior Information Management Advisor with the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (Government of Ontario), and an Adjunct Professor with the Computer Science Department at Ryerson University. He holds B.Eng. five-year degree from the Kiev Aviation Engineering Academy, Ukraine and Ph.D. from the aerospace R&D Institute, Russia. Alexei is a public service practitioner, consultant and researcher with contributions to simulation, implementation and evaluation of complex systems in information management and aerospace. Results of his research are published in more than 70 journal papers, professional magazine articles, technical reports and chapters in three books.

Patrick Finnigan is a Professional Electrical Engineer, and Senior Member of the IEEE. He spent a 40 year career mainly building commercial software products like compilers and databases, but also helping to architect and build several large enterprise-wide software applications. He holds a B.Sc. Physics (York) and a M.Math (Waterloo)