Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 17, No. 2

2025

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

Planning for Climate Change in the NSW Local Aboriginal Land Council Estate

Heidi Norman1,*, Therese Apolonio1, Evelyn Yong2, Calise Liu2, Sharanjit Paddam2

1 University of New South Wales, UNSW Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia

2 Finity Consulting Pty Ltd, 10/68 Harrington St, The Rocks NSW 2000, Australia

Corresponding author: Heidi Norman, University of New South Wales, UNSW Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia, h.norman@unsw.edu.au

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v17.i2.9634

Article History: Received 21/02/2025; Revised 28/05/2025; Accepted 28/05/2025; Published 26/07/2025

Citation: Norman, H., Apolonio, T., Yong, E., Liu, C., Paddam, S. 2025. Planning for Climate Change in the NSW Local Aboriginal Land Council Estate. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 17:2, 19–33. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v17.i2.9634

Abstract

The Aboriginal land estate in NSW is uniquely vulnerable to the physical risks of climate change and this jeopardises the rights and interests of First Nations peoples. This paper presents the findings of research and knowledge exchange between a cross-disciplinary research team and Local Aboriginal Land Councils (LALCs). The research team, with expertise on Aboriginal land rights, energy policy and actuarial modelling, assessed physical risk to LALC lands in regional NSW. At workshops held in the NSW Far Western Zone and in northern and southern NSW, LALCs truth-tested these findings. By sharing their knowledge and priorities for living on their land during climate change, these LALCs highlighted the limitations and cultural bias of Western models of assessing risk. This paper explains the context of the Aboriginal land estate and climate change risks and shares our preliminary findings, along with some considerations for supporting LALCs to develop strategies for climate adaptation and mitigation.

Keywords

Climate Change; Aboriginal Community Resilience; Indigenous Land Estate; Physical Risk; Climate Scenarios

Introduction

As researchers working in the field of Aboriginal land justice, Heidi Norman and Therese Apolonio have been assisting Local Aboriginal Land Councils (LALCs) in regional areas of NSW to plan for climate change and the renewable energy transition. Aboriginal repossession of land in NSW has coincided with the urgent need for global action to avert the worst effects of climate change. Norman and Apolonio identified the need for Aboriginal communities to plan for and adapt to the intensifying impacts of climate change to ensure long-term survival on Country and have conducted geospatial analysis of the land assets held by LALCs in western New South Wales to examine the suitability of these lands for solar and wind projects (Norman et al. forthcoming unpublished a, unpublished b).

Climate change will increase the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, which will have significant social and economic impact. Rising temperatures directly impact rainfall patterns by increasing atmospheric moisture, leading to increased rainfall extremes (O’Gorman 2015). In addition, severe and extreme heatwaves have claimed more lives than any other natural hazard in Australia (Coates 2014). Vicedo-Cabrera et al. (2021) found that 37 per cent of warm-season heat-related deaths over the past few decades could be attributed to climate change.

Norman and Apolonio set out to identify potential climate risk impacts for property assets on Aboriginal owned lands and to generate aggregate-level insights that could be of use for Aboriginal land councils. To assess the physical risk arising from exposure to flood, bushfire, cyclone, and storm, as well as the impact of heat stress, they worked with co-authors Evelyn Yong, Calise Liu and Sharanjit Paddam of the actuarial firm Finity Consulting Pty Ltd (Finity). They used Finity’s natural peril models, Finperils, which are widely used in the insurance sector, to project physical risk arising under various climate scenarios.

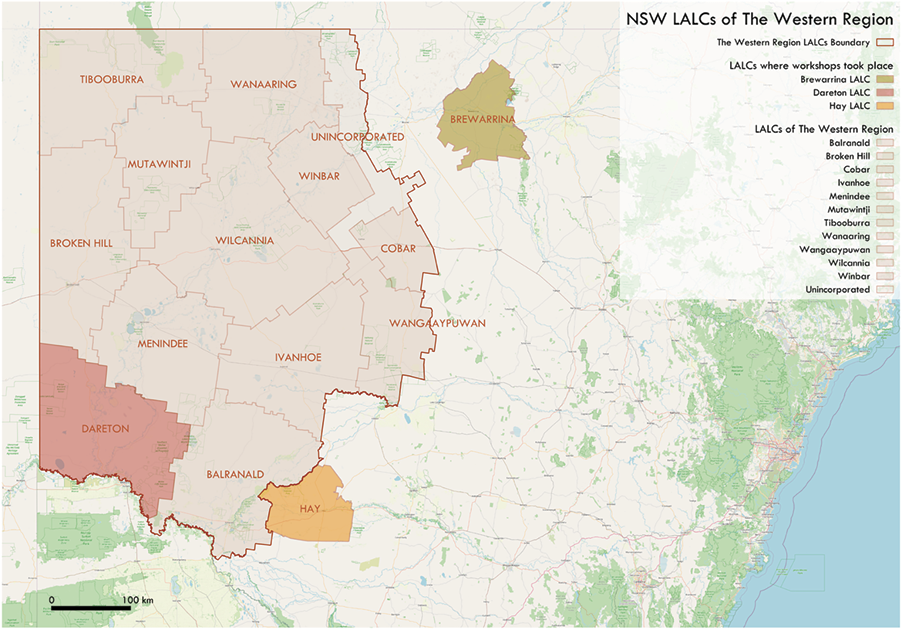

Norman and Apolonio then organised three workshops, in partnership with the NSW Aboriginal Land Council network with the aim of discussing how LALCs might respond to these risks, through renewable energy projects, other forms of land care, and modifications to dwellings and other structures. The workshops were held in the Dareton for the Far Western Zone of the Aboriginal Land Council, Brewarrina LALC and Hay LALC (see Figure 1). Workshops were structured to elicit a process of knowledge exchange between experts and LALC members. Yong, Liu and Paddam attended workshops as experts, and presented LALCs with information and estimates of the financial impact of climate-induced natural disasters on building assets. LALC members, in turn, were asked to truth-test the findings and responses were recorded as part of the overall research findings. In this process, LALC members shared their deep knowledge of their land, including its cultural heritage significance, historical weather patterns, community needs, and local preferences in relation to land access and use. These knowledge exchange workshops were effective forums for valuing different kinds of expertise and bringing different knowledge systems together to provide a pathway to develop LALC-specific plans for climate adaptation and mitigation.

Figure 1. Location of Local Aboriginal Land Councils who took part in knowledge-exchange workshops. (Map created by Finity Consulting)

None of the participants, in any of the three workshops, suggested the option of moving away from their land to escape the effects of climate change. LALC members raised concerns about future impacts on their community and began thinking though mitigation strategies. These included land management, such as returning water to rivers and wetlands, securing the supply of clean affordable energy to meet imminent increases in energy demand, and climate adaptation and disaster management plans in instances where extreme weather events isolate communities (Norman et al. forthcoming).

In this paper we share our initial research and findings. We offer some reflections on the impact, limitations and cultural bias of the existing modelling, discuss the utility of climate risk planning for LALCs, and consider what adaptive and mitigation strategies LALCs could take in response to predicted climate change risks.

The nature of the Aboriginal land estate

In New South Wales, local Aboriginal land councils (LALCs) have been engaged in a process of repossessing land to Aboriginal community control since the passage of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) (ALRA). The land estate controlled by Aboriginal people across NSW comprises freehold title land, along with joint management of National Parks, rights and interests in most of the conservation estate, and the responsibility to protect cultural heritage (Norman 2017). The dominant land recovery mechanisms in NSW are the ALRA and the Commonwealth Native Title Act 1995 (NTA). In this article we focus on the land estate recovered under the ALRA.

While the volume of land recovery at the national level is significant, in NSW land recovery has been frustratingly slow and highly constrained, with less than 1 per cent of land returned and much more awaiting determination by the NSW Government. Much of the Aboriginal land estate is of high biodiversity value. The national Aboriginal land estate contains 78 Indigenous Protected Areas, which comprise half of the nation’s conservation estate. In NSW, it is estimated up to 80 per cent of land recovered under the ALRA is zoned ‘conservation’, including land in residential, urban, rural and remote locations. Aboriginal land holdings in urban areas, some extending into the coastal zone and sea, are of high biodiversity value and provide vital green corridors in urban landscapes. Indigenous people are guardians of local and traditional knowledge systems and while some are thriving and others recovering, this knowledge connects people to places of heritage and environmental significance, and to animals, plants, and the seasons.

There are structural and political economy dimensions inherent in Indigenous landholdings. Throughout colonial history, Aboriginal people have been dispossessed of their land, nearly always in violent circumstances. Small land allocations in the form of Aboriginal reserves, often known as missions or Aboriginal stations, emerged as sites of containment and segregation. Many of these former Aboriginal reserves and stations are now held by LALCs and serve as ongoing homelands. However, in nearly all cases, these allocations reinscribe the spatial segregations of the past, which worked to ensure Aboriginal people and families were excluded from the areas favoured by white settlers and townspeople. LALC lands are often demarcated from the main township by a creek, river or train line, and are generally situated on economically marginal, low-lying land.

Such lands are vulnerable to climate change and warming temperatures. Not only are they susceptible to flooding, but the intensifying climate will exacerbate bushfires, heat stress, ecosystem collapse and food and water security.

Potawatomi philosopher Kyle Powys Whyte (2017) situates climate change in the context of a longer timeframe of environmental change wrought by colonisation and extractivism. Whyte notes dystopic descriptions of the future have been a feature of mainstream public discourse on climate change and offers a compelling alternate perspective: Indigenous peoples and their ancestors are living through the dystopian world in the now. Climate change has and continues to transform Indigenous societies, rupturing human and non-human relations that have existed since deep time.

Whyte’s portrait of climate change reveals the rapid changes to First Peoples’ society wrought by colonial violence – loss of access to land, degradation of waterways, wilful extinction of species/ancestors, and the desecration and destruction of landscapes. From Indigenous perspectives, the root causes of the climate crisis manifest as different relationships to the environment. In this context, the changing climate may further dispossess Indigenous peoples of landscapes and places that give meaning to culture and threaten cultural survival. Indigenous perspectives on climate change call for different relationships to nature.

Over the last 5 years, most Aboriginal communities living in regional and remote areas of NSW have been exposed to severe drought, record temperatures and climate catastrophe. This limits the capacity of Aboriginal people to live and work on their Country, which in turn exacerbates underlying vulnerabilities in Aboriginal communities. These vulnerabilities operate at multiple levels and are underpinned by the absence of broader recognition of Aboriginal rights in the national polity. Climate change threatens a new wave of dispossession, causing circumstances where you can no longer live on the land you have been able to recover or in the town you call home.

Government approaches to climate change and NSW Aboriginal communities

Awareness of the impact of climate change is increasing as communities face climate catastrophes. This is discernible in all levels of government and across many industries. NSW Government inquiries held in the wake of the 2019–2020 Black Summer bushfires and the widespread flooding in NSW in early 2022 focused on improving responses and funding to support disaster resilience. They also highlighted a lack of planning, preparation, and engagement with and for Aboriginal communities.

In its submission to the NSW Bushfire Inquiry, NSWALC said ‘an approach that draws on the strength of both Western and Indigenous Knowledge systems will be key to delivering appropriate and beneficial outcomes’ (NSW Aboriginal Land Council quoted in NSW Government 2020, p. 186). The inquiry subsequently found that traditional Aboriginal land management should be employed in hazard reduction. The report also called for more training of Indigenous practitioners, alongside other methods of land management that are supported by government agencies (NSW Government 2020).

Similarly, the report of the 2022 Flood Inquiry recommended that land management and disaster preparation in flood plains should consider the implications of flooding for ecosystems and landscapes and learn from traditional Indigenous land management practices. Reframing floodplains as assets means re-thinking the environmental impact from flood, as floods can have both a positive and negative impact on the environment (NSW Government 2022).

Euahlayi researcher Bhiamie Williamson (2022b) has observed that government emergency management plans in response to the fires of 2020 placed life and property above the ecosystem. He has emphasised the impact of disasters on Aboriginal communities and on Country is relational and interdependent and includes plants and animals (2022b). He argues that to safeguard Aboriginal communities, an ‘integrated response’ that draws on the knowledge and networks of Aboriginal communities and governments is required. Climate risk assessment needs to consider Aboriginal land and assets create plans that align with the values of distinct communities (Williamson 2022a).

The NSW Government’s response thus far indicates a willingness to work with First Nations communities to ensure Indigenous voices are heard in land use planning and resource management. The NSW Government has implemented the Electricity Infrastructure Roadmap (the Roadmap) (NSW, Department of Planning, Industry and Environment 2020) to craft energy transition and meet agreed targets to reduce emissions and, therefore, climate change under the Electricity Infrastructure Investment Act 2020.

The public policy focus to date has been an important step towards building community resilience to climate change impacts in NSW but consideration of the specific impacts of climate change on Aboriginal peoples’ assets and country remains limited. While the Roadmap invites Aboriginal community participation and presents opportunities for communities to negotiate benefits such as jobs and business opportunities, the NSW Government has not made any provision to ensure NSW Aboriginal communities have the resources they need to plan their futures on Country in a climate changing world. At the time of writing the Commonwealth Government is developing the National Adaptation Plan (NAP), which is described as a strategy to ‘better prepare for and manage increasing risks arising from climate change’ (NSW, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water forthcoming). The NAP includes reference to ‘supporting people and communities in disproportionately vulnerable situations’ and reports on consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (NSW, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water forthcoming). As the NAP is finalised, it is vital that resources are made available for Aboriginal organisations, such as LALCs, to plan for climate change and futures on Country.

Models from other governments

First Nations’ rights and interests interface with climate change responses in several key ways. Indigenous knowledges, custodianship of country, culture and heritage rights are all touch points in climate change adaptation plans and new climate economies, as well as potential nature-led solutions.

There are some interesting approaches being taken in Aotearoa/New Zealand, where in 2020 the Ministry of the Environment published its first national climate change risk assessment. In its top 10 most significant climate change risks it recognised the ‘risks to Indigenous ecosystems and species from the enhanced spread, survival and establishment of invasive species due to climate change’ (NZ, Ministry of Environment, p. 8). This risk was called out in the natural environment domain. The assessment also identifies ‘risks to the long-term composition and stability of Indigenous forest ecosystems due to changes in temperature, rainfall, wind and drought’ (NZ, Ministry of Environment 2020, p. 10).

With this assessment, the Ministry published a guide to local climate change risk assessments (NZ Ministry of Environment 2021), which sets out a risk assessment framework to support national adaptation planning and legislation. The guide was developed with direction from government in 2021, and workshops with a local government working group and Māori caucus and panel. It stated the primary purpose of local assessment is to inform adaptation planning and to work alongside and in partnership with hapū, iwi and Māori as Treaty of Waitangi partners on a range of priorities (social, cultural, economic, and environmental). The guide also emphasised that, when planning an assessment, the perspective and needs of Māori must be included early in the process. For example, identifying physical risks to Māori relies on working together with local representatives and understanding their views on both physical and spiritual wellbeing. The Urutau, ka taurikura: Kia tū pakari a Aotearoa i ngā huringa āhuarangi adapt and thrive: Building a climate-resilient New Zealand – New Zealand’s first national adaptation plan was adopted in 2022 (NZ, Ministry of Environment 2022). Further research will evaluate the implementation of the plan and ongoing political and community support.

There are indications of wider government action to place Indigenous perspectives at the centre of climate change responses. In Australia in 2021, a dedicated First Nations-focused chapter was introduced to the Australian State of the Environment (SOE) report, which spotlights changes in landscapes, seascapes, and ecosystems (Australia, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment 2021). Since 2022, the Australian Government has embarked on a wide range of policy and programs that curate investment to transition energy systems along with nature-led solutions to remove greenhouse gas from the atmosphere. These initiatives make provision for the inclusion of First Nations rights and interests.

Opportunities for climate adaption for First Nations communities across Australia are increasing in tandem with national energy transition and other state-level developments, such as treaty and agreement-making between governments and First Nations people. In Victoria, where solar and wind projects are underway, some Traditional Owner corporations have secured funds from the state government, via the Traditional Owner Renewable Energy Program (TOREP) (Victoria Government 2020) and First Peoples’ Adoption of Renewable Energy Program (FPARE), to develop broader climate change and renewable energy strategies for their Nations. As part of the Treaty for Victoria process, a Self-Determination Fund is also being established and it will serve two functions: to enable Traditional Owners to enter treaty negotiations with the government on a more level playing field and, in the longer term, to empower Traditional Owner communities to build capacity, wealth and greater prosperity for future generations.

Accordingly, Victorian Traditional Owners are devising plans for Country and strategies to negotiate with government and renewable energy developers to ensure benefits for the communities they represent. Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation (GLaWAC), as the Prescribed Body Corporate that represents the Gunaikurnai Traditional Owners, explains its Gunaikurnai Country has been the centre of Victoria’s energy economy for more than a century and continues to be as the energy transformation occurs. In 2022, the Australian Government designated Gunaikurnai Country as an Offshore Wind Energy Area. GLaWAC states its members have ambitions to ‘make ourselves a critical partner in this journey’ and outlines seven aspirations that underpin their interest in engaging in the energy transformation:

To have a strong, healthy and happy mob; To heal our Country; To protect and practice our culture; To be respected as Traditional Owners of our Country; To have the right to use, manage and control our Country; To be economically independent; and to have a strong focus on learning (GlaWAC 2023).

Similarly, in May 2023 Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation (DJAARA) launched the Dja Dja Wurrung Climate Change Strategy: Turning ‘wrong way’ climate, ‘right way’, which outlines the importance of DJAARA leadership in both climate adaptation and mitigation (DJAARA 2023a). They explain their approach as healing: healing climate, healing Country and healing Dja Dja Wurrung People. The Dja Dja Wurrung Climate Change Strategy brings together work that DJAARA is already leading on Country, including around natural resource management, cultural burning, forest gardening and Country-based healing. The strategy follows the publication of Djaara’s Renewable Energy (DJAARA 2022) and Forest Gardening strategies (DJAARA 2023b). Across these documents, DJAARA outline the necessary role of Dja Dja Wurrung leadership in addressing climate change in central Victoria. In addition to these plans, DJAARA are leading participants in the Greater Bendigo Climate Collaboration, a group that brings government, business, community organisations, schools and households together to work collaboratively towards zero emissions in Greater Bendigo by 2030 (City of Greater Bendigo 2023).

The Barengi Gadjin Land Council Aboriginal Corporation strategy for engaging in renewable energy and climate change mitigation and adaptation includes Renewable Energy Country Planning and other activities, including close engagement with developers and implementing their own clean energy projects (Norman et al. November 2023). It can be expected that further Recognition and Settlement Agreements over land in Victoria will be reached in coming years, which will include provisions enabling economic development opportunities for Victorian Traditional Owner Groups and pathways for realising climate adaptation ambitions.

Research process and assumptions

Emissions of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, are a major driver of climate change. The climate future will depend on how quickly we reduce greenhouse gas emissions. At the commencement of our research, we considered possible scenarios for future emissions and looked at the resulting impact on extreme weather. It is important to note that a scenario describes a path of development leading to a particular outcome. Scenarios are hypothetical constructs and are not intended to represent a full description of future scenarios, but rather identify central elements and key factors.

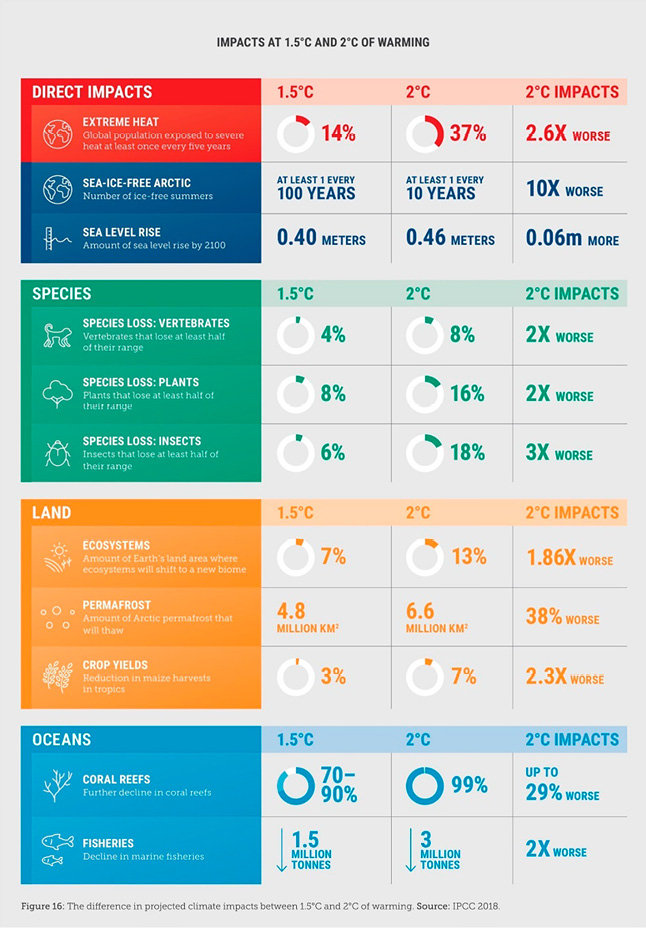

Figure 2. The difference in projected climate impacts between 1.5°C and 2°C. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2018) as summarised in Climate Council (15 April 2023)

The ‘best case’ scenario generally considered by climate researchers is that global warming remains below 2°C by year 2100, with emissions declining to net zero through technology. Even at this level, the warming climate has severe consequences for biodiversity, land and oceans, with damaging impacts on our ecosystems, water resources, agricultural production, tourism, fishing and other industries, and our mental and physical health. The ‘worst case’ scenario, which may result without actions to reduce emissions, the global average temperature is expected to rise by 4.3°C by year 2100. Regardless of the decarbonisation pathway, the Climate Measurement Standards Initiative (CMSI) states that Australia is ‘virtually certain to get warmer’ (Climate Measurement Standards Initiative 2020).

Figure 3. Projected changes in climate hazards that influence physical risks for Australian buildings and infrastructure (Climate Measurement Standards Initiative 2020).

According to CMSI guidance, ongoing drying of the climate and increased extreme weather events, including short-duration heavy rainfall and more heat extremes, will mean that:

• Bushfires will be more extreme, due to more frequent drought conditions and higher temperatures.

• Generally, storms will be more severe, due to more intense rainfall from higher temperatures, although the frequency of storms on the eastern coast of Australia will reduce.

• The risk of floods is expected to increase, owing to the greater frequency of extreme rainfall events.

• Cyclones are expected to occur less often but when they do occur will be more damaging. Cyclones may also move further south. (Climate Measurement Standards Initiative 2020).

Our research was conducted using data on the land assets held by the Local Aboriginal Land Councils (LALCs) in the Far Western Zone (FWZ), and for Brewarrina LALC in northern NSW and Hay LALC in southern NSW.

Prior to each workshop, we overlaid our data with Finity’s proprietary natural perils dataset, Finperils. Finperils is widely used in the general insurance industry to set property insurance premiums, providing an assessment of the physical risk arising from exposure to flood, bushfire, cyclone, storm, earthquake, and coastal inundation for each residential and commercial building in Australia. Finperils also includes a projection of the physical risk arising under various climate scenarios. Finperils is a dataset created to assess home buildings and contents insurance, and there were limitations in applying this dataset to the landholding assets held by the LALCs. For example, data availability for metropolitan areas is higher than for landholdings in rural and regional NSW. Further, many buildings on LALC landholdings may not be residential properties.

The assessment of the current natural perils risk included all land which has been granted to LALCs under the ALRA and other repossessed land, acquired by LALCs outside of ALRA land claims process. This includes land purchased by LALCs on the open market, land divested to a LALC (for example through the Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation), land bequeathed to a LALC or transferred to a LALC by government (for instance, after the dissolution of government departments that managed Aboriginal reserves such as the Aborigines Welfare Board (1940-1969) and the Aboriginal Lands Trust (1973-1983). Future LALC land assets, which are lands that are currently under claim and awaiting determination by government, were included in the future climate scenarios.

Truth-testing in workshops

To explore the potential of LALC engagement in the NSW renewable energy transformation and to assess risks and opportunities from climate change Norman and convened workshops in regional NSW, and invited experts such as Yong, Liu and Paddam.

In February 2023, the Indigenous Land and Justice Research Group, led by Norman, conducted a workshop in Dareton, on the Murray River in far western NSW. The workshop was convened by Ngiyampaa and Wiradjuri man Ross Hampton, Deputy Chair and elected Councillor of the Western Region of the NSW Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC). This region encompasses LALCs in the far western third of the state, including Balranald, Broken Hill, Cobar, Dareton, Ivanhoe, Menindee, Mutawintji, Tibooburra, Wanaaring, Wangaaypuwan, Wilcannia and Winbar. CEOs and members of these LALCs were invited to the Dareton workshop. Yong, Liu and Paddam, were invited to present Finity’s preliminary research on the analysis of risks arising from the physical impacts of climate change to Aboriginal land and assets (‘physical climate risk’). This workshop had originally been scheduled for late 2022 but was postponed owing to extreme flooding affecting far western NSW. This event was the second extreme flooding event since 2019 and meant that workshop participants already registered the effects of climate change on their community and on their country.

We observed that when our team shared research findings on climate change, the mood in the room became serious and sombre. Earlier presentations covered topics such as the relationship between climate change and renewable energy transition, the economic and political drivers of transition, and the political levers necessitating the renewable energy industry’s engagement of First Nations, social licence and benefit-sharing. These earlier topics were met with some scepticism and free and fearless interjection while discussion of climate risk was met with concerned silence. Authors of this paper who were present at the Dareton workshop observed that the LALC community deeply registered the risks from the already changing environment.

We also ran a workshop at Brewarrina in May 2024 and at Hay in October 2024. These workshops were run specifically for the individual LALCs, and were attended by community Elders, members, and LALC staff members. The responses in these workshops differed substantially from the reactions in Dareton. These communities have faced extensive drought in the past so viewed the projected floods as life-giving. It was clear that lived experiences shaped each community’s attitudes towards climate risk, and this reinforced to us that genuine community engagement, and the understanding of each community’s unique context and needs, was critical to supporting successful and effective climate adaptation.

Detailed case study: Climate risk assessment for LALCs in the Aboriginal Land Council Far Western Zone (FWZ)

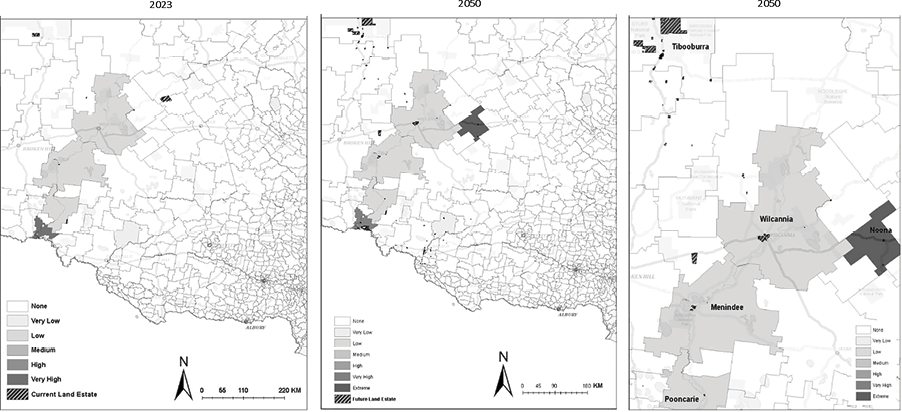

Below we show some results of the climate risk assessment conducted for LALCs in the FWZ of NSW. The most acute climate physical risk is flood, which accounts for more than 90 per cent of the total potential damage on buildings. This is especially the case on land near the Lower Darling and Barwon catchments. Areas with the highest flood risks are close to the Murray-Darling Rivers and the Menindee Lakes. All suburbs in the FWZ have some underlying exposure to bushfire and storm risks, but there are no cyclone or significant earthquake risks in this area.

The maps below show the current and projected climate physical risk for LALCs in the FWZ, including future land estate as at year 2050, under the high emissions scenario. The darker the colour, the higher the projected physical risk in that suburb.

Figure 4. Current and projected climate physical risk for LALCs in the FWZ under the high emissions scenario (Analysis by Finity Consulting, 2023)

Looking ahead to year 2050 under the high emissions scenario, the overall risk of extreme weather events is expected to increase by 12 per cent under the high emissions scenario. This is mainly due to higher flood risk in the low-lying south-western areas of the FWZ as rainfall intensity increases.

One of the key reasons for rainfall intensity increasing is due to projected rising temperatures in the FWZ. In the FWZ, the maximum temperature has increased by 1.5–2°C over the past 50 years, and the number of extreme heat days (with temperatures above 40°C) are projected to increase by up to 15 days per year by 2070 (Office of Environment and Heritage, 2014). As drought seasons becoming longer and more intense, particularly during El Niño cycles, water security in the region will be threatened. Heat could make large sections of western NSW difficult to inhabit for parts of the year.

The consequences of natural disasters such as those experienced in the last five years—drought, fires and floods—extend beyond the damage to buildings. They represent a clear and significant threat to Indigenous peoples’ health, economy, and cultural heritage.

Workshop responses

The workshops revealed the profile of climate risk was similar across the three areas, with floods being the main source of climate physical risk1. However, participant reactions to a message of more frequent and more severe floods varied significantly.

The first workshop was in Dareton, a region that had recently been impacted by severe flooding that cut off all road access to the region. Our research findings were met with silence from Aboriginal participants – the prospect of further devastation, after the recent catastrophes, was confronting. The main concerns participants had was regarding action: what could communities do about the findings and how could they minimise the risks?

The second workshop was in Brewarrina, a region that had also been impacted by floods a year prior to the workshop, following an extended period of drought. Discussion at this workshop differed substantially to Dareton, because the region experiences regular droughts and floods are viewed by the community as life-giving. This community’s resilience to flood had also improved due to the construction of a community levee, so they were protected from the full extent of the 2022 floods. The conversation was focused on adaptation, and how better to prepare as a community for more severe events in future, rather than on how to prevent climate change and avoid further devastation.

The third workshop was in Hay, at a LALC that was aware of the impact of climate change and had incorporated it into their long-term community strategy. The conversations at this workshop underscored the differences between the Aboriginal and Western cultural perspectives of floods, such as the risk assessment we were presenting, and one that is more attuned to stewardship of the lands based on thousands of years of knowledge. While our risk assessment focussed on damage to buildings, the forecast of more frequent floods under climate change was not seen by the Aboriginal community members as a threat to security and life on Country, but rather as bringing lush, green grass and life to the surrounding wetlands, especially after long periods of drought. However, the community was worried about the effect of rising temperatures and humidity on food insecurity. In addition, the further drying of wetlands and major losses of wildlife habitat under climate change was acknowledged as having impacts on irrigation infrastructure, farming, workforce, ecotourism and carbon sequestration potential.

Across the three workshops, it was clear that climate change was already apparent and part of people’s lived experience in regional NSW. However, the different responses to the impacts of climate change across the three workshops reinforced that understanding each community’s unique context is critical to supporting successful and effective adaptation.

Ultimately, these workshops are about knowledge empowerment and exchange. Providing information to LALCs enables them to make decisions about how to best support and future-proof their community and care for Country for generations to come.

Workshop participants pointed out their experiences of social and economic disadvantage and the patterns of declining economies and populations in towns and regions. The point was also raised about the ongoing marginalisation of Aboriginal voices in climate change discourse that point to structural factors that shape who is heard, and why. This was raised in the workshop we convened in far western NSW where Barkandji people expressed their exasperation that their concerns for the river came into greater focus and national attention at the height of the 2018–19 drought when many millions of fish perished in what remained of their river. The images of grieving farmers and fish kills on nightly news stories horrified the general public, however, what was conveyed in workshops was a sense of despair over the subordination of the Barkandji people as the Traditional Owners and their mother, the Baaka (Darling River), to the dominant economic interests of producers (farmers). Local people expressed a sense of loss and helplessness, compounded by frustrations about water management and policy decisions in the Murray-Darling Basin (Ellis et al. 13 September 2021).

Cultural biases and limitations

The research was necessarily focused on buildings, properties, and assets. Current models of assessing physical risks from climate change risks do not address the impact on cultural sites; how climate change impacts when viewed through a cultural lens would yield different insights. Exchanges with LALC members quickly revealed the limitations of our methodology for assessing climate risk, particularly around physical risk to cultural heritage sites.

Our research prompted Aboriginal participants to consider what impact climate change will have on sacred scar trees and ancestral burial sites, which are vulnerable to erosion. In another exchange, one man recalled impact of the loss of their totem, starved of oxygen by low, black water during the fish kills in the Baaka.

Future research should extend to climate change impacts beyond buildings, to assess the health of humans and non-humans, landscapes, and more. Developing climate change risk assessment for cultural heritage will require communities to assess and map important sites. However, most LALCs lack the resources to assess climate risk at this scale and there is, understandably, some hesitation around sharing cultural knowledge widely.

Resourcing LALCs for climate change adaptation

LALC members wanted to understand the risk to their members’ housing, and animals and landscape, and how they could build climate change risks into future land management and planning. Where our research identified high physical risks to current landholdings, LALCs responded by asking if they would be better off selling properties now, rather than in 20 years’ time.

LALCs began to think about the climate risks associated with recoverable lands, and how a risk assessment could assist them to prioritise land claims that are awaiting determination. Some LALCs wanted to delve deeper into the risk assessments for land under claim to ensure they could develop a long-term plan to protect that site, or else consider whether it was a burden they could take on. LALCs we worked with on this research said that they want to be better equipped to respond to climate change in relation to their land assets. Some LALC CEOs wondered how some of their properties would fare in extreme weather conditions, especially given that many LALCs provide housing for their communities. Some LALCs still experience energy insecurity and rely on back-up diesel generators during regular energy dropouts. There were direct and practical concerns: What will the impacts of heat be on old and young people? What will LALC energy usage be in the future, as they try to keep homes and communal spaces cool? What are more reliable and less polluting alternatives to powering LALC offices and homes?

Outside of landholding assets, LALCs also considered disaster response in the context of resilience in community leadership, and continued access to essential services. There was also discussion on reliable electricity supply for fresh food and having more boats available for transport when the rivers flooded. As noted above, no participant in the three workshops suggested the option of moving away from their land to escape the effects of climate change.

Awareness of risks can prepare communities and may even generate new opportunities. We hope that this research prompts conversations about climate change and climate preparedness for Aboriginal communities and their land estate and country.

Conclusion: A Call to Action

In addition to identifying climate change impacts and engaging the Aboriginal land estate, Aboriginal people want to share their knowledges and thinking to inform climate change adaptation. Beyond the immediate impact on Aboriginal lives and managed resources, incorporating long-held Aboriginal knowledges and systems thinking as relational and imbued with kin and spiritual connections in the management of landscapes, is central to recognition and reconciliation as expressed in the invitation articulated in the Uluru Statement from the Heart to ‘walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future’ (2017).

Our detailed climate risk assessment shows that the Aboriginal LALC estate and communities will be impacted by climate change in numerous ways, and with health and economic consequences. Flood risk and heat stress are projected to increase with climate change; drought seasons will become longer and more intense, particularly during El Niño cycles; water insecurity in the region will further increase.

Our study was largely confined to the impact of climate change on land and assets. Climate risk assessment will be more relevant when supplemented with local level Aboriginal knowledge and Aboriginal-led priorities and perspectives. A necessary next step is more detailed assessment that includes cultural heritage and Indigenous knowledge, combined with development of a climate action strategy for each LALC or region. Such studies will be of high practical benefit in the planning land use, land claims, land recovery and future development, such as projects associated with energy transformation.

If Indigenous land holders are to participate and lead climate change mitigation and adaptation, they need independent and informed research, policy advocacy, evaluation tools, technical expertise, and capital. We see ensuring that Aboriginal people are provided with the resources and research evidence they need to inform their decision making is essential to climate risk assessment.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Local Aboriginal Land Councils in Far West Zone, Brewarrina Local Aboriginal Land Council and Hay Local Aboriginal Land Council for generously sharing their time, knowledge, expertise and engagement in this research. Thanks to the New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council, and in particular, Councillor Ross Hampton and the Far West Zone Office for their support. We thank Dr Naomi Parry Duncan for editing support, Ondrej Bures for assistance with mapping, Saroop Philip and Nghaeria Roberts for contributing to LALC workshops, and anonymous reviewers for feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

References

Australia, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment 2021, Australia; State of the Environment 2021, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, https://soe.dcceew.gov.au/

City of Greater Bendigo 2023, Greater Bendigo Climate Collaboration, https://www.bendigo.vic.gov.au/community-services/environment/greater-bendigo-climate-collaboration#about-greater-bendigo-climate-collaboration

Climate Council 2023, Impacts of Degrees of Warming, 15 April, https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/resources/impacts-degrees-warming/.

Climate Measurement Standards Initiative 2020, Scenario analysis of climate-related physical risk for buildings and infrastructure: Financial disclosure guidelines & climate science guidance. https://www.cmsi.org.au/reports

Coates, L.H. 2014, ‘Exploring 167 years of vulnerability: An examination of extreme heat events in Australia 1844–2010’, Environmental Science & Policy, vol. 42, pp. 33-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.05.003

Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation (DJAARA) 2022, Dja Dja Wurrung Renewable Energy Strategy, https://djadjawurrung.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/DJA25.-Renewable-Energy-20220921-Final.pdf

Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation (DJAARA) 2023a, Climate Change Strategy, https://speedyassets.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/djaara/Climate-Change-Strategy-230523.pdf

Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation (DJAARA) 2023b, Forest Gardening Strategy, https://djadjawurrung.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Forest-Gardening.pdf

Ellis, I., Bates, W. Marin, S., McCrabb, G., Koehn, J. & Heath, P. A. 2021, ‘How fish kills affected traditional (Baakandji) and non-traditional communities on the Lower Darling-Baaka River’, Marine and Freshwater Research, vol. 73, no.2, pp. 259-268. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF20376

Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation (GLaWAC) 2023, Renewable Energy Strategy Objectives, https://gunaikurnai.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Renewable-Energy-Strategy-Objectives.pdf

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2018, ‘Summary for Policymakers’, In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 3-24. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157940.001

New Zealand (NZ), Ministry for the Environment 2020, National Climate Change Risk Assessment for New Zealand Snapshot; Arotakenga Tūraru mō te Huringa Āhuarangi o Āotearoa Whakarāpopotonga, https://environment.govt.nz/assets/Publications/Files/national-climate-change-risk-assessment-new-zealand-snapshot.pdf

New Zealand (NZ), Ministry for the Environment 2021, He kupu ārahi mō te aromatawai tūraru huringa āhuarangi ā-rohe; A guide to local climate change risk assessments, Wellington. https://environment.govt.nz/assets/publications/climate-risk-assessment-guide.pdf

New Zealand (NZ), Ministry for the Environment 2022, Urutau, ka taurikura: Kia tū pakari a Aotearoa i ngā huringa āhuarangiAdapt and thrive: Building a climate-resilient New Zealand – New Zealand’s first national adaptation plan. https://environment.govt.nz/publications/aotearoa-new-zealands-first-national-adaptation-plan/

Norman, H. 2017, ‘Return of public lands to Aboriginal control/ownership’, in Transforming the relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the NSW Government: Aboriginal Affairs NSW research agenda 2018-2023, Aboriginal Affairs NSW, Department of Education, Sydney, pp. 15-30.

Norman, H., Apolonio, T., Briggs, C. & Nelson, F. 2023, Victoria Policy Overview: First Peoples and clean energy, Nation Builder website, November 2023. https://assets.nationbuilder.com/fncen/pages/430/attachments/original/1700611485/Victoria_-_Policy_Overview_-_First_Peoples_and_Clean_Energy-2.pdf?1700611485

Norman, H., Briggs, C., Langham, E., Apolonio, T., Miyake, S. & Niklas, S. 2024, unpublished b, Renewable Hay: Local Aboriginal Land Council-led energy systems transformation, Hay LALC, UNSW Sydney, UTS Institute for Sustainable Futures.

Norman, H., Briggs, C., Langham, E., Apolonio, T., Miyake, S., Niklas, S., & Teske, S. 2024, unpublished a, Renewable Brewarrina: Local Aboriginal Land Council-led energy systems transformation, October 2024, Brewarrina LALC, UNSW Sydney, UTS Institute for Sustainable Futures.

Norman, H., Briggs, C., Langham, E., Apolonio, T., Miyake, S., Niklas, S., Teske, S. forthcoming, Local Aboriginal Land Council ‘Powershift’: How can Local Aboriginal Land Councils share in the benefits of the energy transition?, Australian Public Policy Institute, Policy Insights Paper.

NSW, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water forthcoming, https://www.dcceew.gov.au/climate-change/policy/adaptation/nap

NSW, Department of Planning, Industry and Environment, NSW Electricity Infrastructure Roadmap: Building an Energy Superpower – Detailed Report November 2020, https://www.energy.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-08/NSW%20Electricity%20Infrastructure%20Roadmap%20-%20Detailed%20Report.pdf

NSW Government 2020, NSW Bushfire Inquiry: Final Report, 30 July 2020. https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/noindex/2023-06/Final-Report-of-the-NSW-Bushfire-Inquiry.pdf

NSW Government 2022, 2022 Flood Inquiry Volume One: Summary Report, 29 July 2022. https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/noindex/2022-08/VOLUME_ONE_Summary.pdf

NSW, Office of Environment and Heritage 2014, Far West Climate Change Snapshot, https://www.climatechange.environment.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-06/Far%20West%20climate%20change%20snapshot.pdf.

O’Gorman, P. 2015, ‘Precipitation extremes under climate change’, Current Climate Change Reports, vol. 1, pp. 49-59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-015-0009-3

Uluru Statement from the Heart (2017) The Statement, Uluru Statement from the Heart website, https://ulurustatement.org/the-statement/view-the-statement/

Vicedo-Cabrera, A.S. et al. 2021, ‘The burden of heat-related mortality attributable to recent human-induced climate change’, Nature Climate Change, vol. 11, pp 492-500. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01058-x

Victoria Government, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action 2020, ‘Traditional Owner Renewable Energy Program’. https://www.energy.vic.gov.au/grants/traditional-owner-renewable-energy-program

Whyte K. P. 2017, ‘Our ancestors’ dystopia now. Indigenous conservation and the Anthropocene, In: Heise U., Christensen J. & Niemann M (eds.), Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities, Routledge, NY, pp. 222-231. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315766355

Williamson, B. 2022a, ‘Aboriginal community governance on the frontlines and faultlines in the Black Summer bushfires’, Australian National University, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR), CAEPR Discussion Paper 300/2022, ANU, Canberra. https://doi.org/10.25911/V482-AE70

Williamson, B. 2022b, ‘Like many disasters in Australia, Aboriginal people are over-represented and under-resourced in NSW floods’, The Conversation, 4 March 2022, https://theconversation.com/like-many-disasters-in-australia-aboriginal-people-are-over-represented-and-under-resourced-in-the-nsw-floods-178420

1 Far Western NSW Aboriginal Land Council Regional Forum (21st February 2023), Dareton, NSW; Brewarrina Local Aboriginal Land Council Energy Summit (20th May 2024), Brewarrina, NSW; Hay Local Aboriginal Land Council Renewable Energy Workshop (14th October 2024), Hay, NSW.