Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 17, No. 2

2025

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

First Nations People and Energy Transition: How to Increase Employment in Clean Energy

Chris Briggs1,*, Michelle Tjondro2, Rusty Langdon1, Sarah Niklas1, Ruby Heard3, Michael Frangos4, Elianor Gerrard1

1 University of Technology Sydney

2 SGS Economics and Planning

3 Alinga Energy Consulting; The University of Melbourne, Australia

4 Indigenous Energy Australia

Corresponding author: Chris Briggs, University of Technology Sydney, 15 Broadway, Ultimo, NSW 2007, Australia, Chris.Briggs@uts.edu.au

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v17.i2.9602

Article History: Received 04/02/2025; Revised 21/03/2025; Accepted 21/03/2025; Published 26/07/2025

Citation: Briggs, C., Tjondro, M., Langdon, R., Niklas, S., Heard, R., Frangos, M., Gerrard, E. 2025. First Nations People and Energy Transition: How to Increase Employment in Clean Energy. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 17:2, 34–53. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v17.i2.9602

Abstract

Training and employment will be a key determinant of whether the socio-economic position of First Nations peoples is improved through the energy transition, but there are few studies on how to increase First Nations employment in renewable energy. Our study, which focusses on Renewable Energy Zones in Australia, has four key findings. Firstly, employment and training mandates and incentives in government renewable energy auctions can increase First Nations employment, but a ‘coordinated flexibility’ approach is required which accommodates regional variations, differences in occupational structure between technologies and integrates First Nations businesses. Secondly, training-led initiatives have a poor job-creation record, but programs for school students and the unemployed are required to build the labour supply to meet procurement targets. Thirdly, wherever possible, demand and supply-side instruments should be integrated within clean energy programs (e.g. housing retrofits). Fourthly, complementary measures are required which resource industry to achieve targets, improve cultural safety in workplaces and build the capacity of First Nations organisations.

Keywords

First Nations; Indigenous; Clean Energy; Renewable Energy Employment; Just Transition

Introduction

The global energy transition entails the building of large-scale solar and wind farms, battery storage, and power lines in regional areas. For First Nations peoples, renewable energy is another wave of infrastructure development which presents challenges, risks, and opportunities. Much of the literature on the impact of renewable energy development on First Nations peoples has centred on land sovereignty, consent, and the opportunities for economic benefits from ownership of renewable energy assets.

Another important determinant of whether First Nations people benefit from the energy transition is whether it leads to increased, higher-quality employment. Secure, well-paid employment is a key contributor to well-being. In Australia, the large gap in employment rates and quality of employment is a core structural factor in the persistent socio-economic disadvantage and poverty of First Nations peoples. Just over half of First Nation Australians are employed relative to the population-wide employment rate of 60-65% (Jobs and Skills Australia 2023a). As the Australian Government’s employment white paper noted: ‘the employment rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continues to significantly lag that of non-indigenous people, and the gap has not closed notably over the past 30 years’ (Commonwealth of Australia 2023, p. x).

This study investigates whether and how the energy transition could lead to increased training and employment for First Nations people in Australia within Renewable Energy Zones (REZs). A series of REZs have been established to coordinate new investment in renewable energy, energy storage, and transmission lines in regional areas. This paper is organised into the following sections:

• Context: an overview of the current energy transition and First Nations’ involvement;

• Methodology: a summary of the quantitative and qualitative methods used in this study;

• Literature review: an analysis of insights from existing studies on First Nations and clean energy and First Nations employment;

• Quantitative analysis of the potential for First Nations employment creation in the REZs;

• Policy implications: four key considerations are identified for policymakers to increase employment and training opportunities for First Nations peoples in clean energy.

Whilst the study is based in Australia, policy implications are identified that can be applied in other societies to develop holistic jobs strategies and realise the opportunity to increase the employment of First Nations peoples in clean energy.

Context: Australia’s Energy Transition and First Nations Australians

Australia is a settler colonial society, characterised by the dispossession of First Nations lands, cultures and societies. The coercive assimilation of First Nations peoples is one of the defining historical features of Australia’s settler society, marked by struggles for access to land and resistance as some communities remain on Country (Klein 2020). The historical structures of land use, access and ownership continue to shape the energy transition in Australia; it is estimated that achieving Australia’s net zero goal will require 43% of renewable energy infrastructure to be developed on formally recognised First Nations land (Net Zero Australia 2023).

First Nations’ labour, employment and mobility are interlinked with the dynamics of settler colonial society (Stead & Altman 2019, p. 2). Australia’s history is dotted with the complex, contradictory histories of First Nations participation in the labour market, from the exploitation and resistance of First Nations workers in the pastoral industry (Stead & Altman 2019), labour markets in remote areas primarily constituted by government programs to marginal participation in the formal labour market and churning through low-wage jobs and unemployment. There is an on-going tension as the organisation of work in market economies rarely acknowledges, accommodates or reflects the cultural practices and needs of First Nations peoples. The energy transition enters a context shaped by the history of settler capitalism and the contradictory co-existence with First Nations people.

Australia is attempting to orchestrate a rapid transition from a coal-based electricity system to renewable energy, with a national government target of 82% renewable energy by 2030. Policy-settings are broadly aligned with the ‘step change’ scenario in the Australian Energy Market Operator’s Integrated System Plan (ISP) under which most coal-fired power stations would be retired by the early to mid 2030s. Under the step change scenario, renewable energy employment is projected to double to just over 66,000 by 2029 (Rutovitz et al. 2024). First Nations involvement and participation in the renewable energy sector has been low to date. Except for a few projects under development (FNCEN 2024), First Nations ownership or equity in renewable energy projects is rare and engagement with First Nations communities is acknowledged as inadequate by the renewable energy industry (CEC & KPMG 2024).

A range of policy and industry initiatives are being implemented to increase the participation of First Nations Australians in clean energy including employment. The Australian Government released a First Nations Clean Energy Strategy in 2024, which includes increased First Nations employment as a goal (Australian Government 2024c). Government renewable energy auctions at the national level (the Capacity Investment Scheme) and the state of New South Wales include criteria for First Nations economic participation and employment (AEMO Services 2022; Australian Government 2024b). While formal evaluation of these initiatives is yet to come, there is universal agreement amongst industry, government, employment service providers, First Nations representatives, and workers in the sector interviewed for this study, that employment of First Nations Australians in clean energy is low. Using occupations employed by clean energy as a proxy, Jobs and Skills Australia (2023b, p. 229) concluded that First Nations Australians are under-represented in the clean energy workforce (1.9% of employment relative to a population share of 3.8%).

Methodology

This study applies a mixed methods approach to investigate the potential for First Nations employment in clean energy. Firstly, a desktop review of academic and grey literature on First Nations training and employment participation, policy and programs, and involvement in clean energy was undertaken.

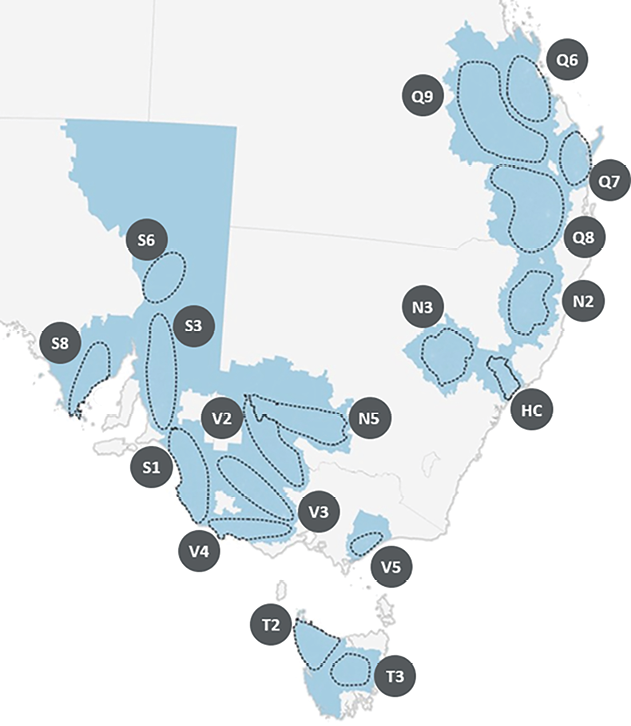

Secondly, the scope for increasing the employment of First Nations Australians in Renewable Energy Zones (REZs) was analysed by comparing labour supply against employment projections. REZs, which are being established across the National Electricity Market include the states of New South Wales (NSW), Queensland, Victoria, South Australia (SA) and Tasmania (Figure 1), are the key sites for the development of large-scale renewable energy generation, transmission, and storage projects. The labour supply of First Nations Australians was analysed for a cross-section of REZs using census data for the existing workforce, students, unemployed, and those not in the labour force. Labour supply was compared against renewable energy employment projections for each REZ modelled for the step change scenario in the Australia Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) ISP (AEMO 2024).1 Three employment shares were used as benchmarks: 1.5% (a common benchmark in tenders for First Nations employment), (NIAA 2020), 10% (a ‘stretch goal’ in renewable energy auction guidelines for NSW, (AEMO Services 2022, p. 67) and 5% (a mid-point between these minimum and stretch goals).

Figure 1. Renewable Energy Zones (REZs) in Queensland (Q), New South Wales (N), Victoria (V), South Australia (S), and Tasmania (T)

Source: Author analysis

Thirdly, empirical data on the barriers, opportunities, and solutions to increasing First Nations training and employment in clean energy was collected through fieldwork, including semi-structured interviews, two in-person workshops, and one online workshop. In total, 27 interviews were conducted including First Nations representatives, employment, training, and recruitment specialists that work with First Nations job seekers, renewable energy personnel (including some First Nations people), Government officials (NSW, Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia, WA), electricity utility staff, union officials and vocational education and training staff. The first in-person workshop in Wellington (located within the Central-West Orana REZ, NSW) included community representatives, solar and wind farm developers, vocational education specialists and government staff. The second in-person workshop was held with First Nations community members in Yarrabah, Northern Queensland, to understand the dynamics in a more remote location. A third workshop with employment service providers in the states of Queensland and Western Australia was held online.

Existing Literature: First Nations, Energy Transition and Employment

There is a growing body of literature looking at the participation of First Nations people in clean energy. Studies have been undertaken across a range of nations including Canada, New Zealand, the United States and Central and South America (see O’Neill et al. 2021, p. 2; Fish & Nehme 2024, p. 2), investigating the risks, opportunities, impacts and benefits for First Nations people. Whilst many of the studies focus on land rights, sovereignty, and First Nations ownership, fewer studies address employment within clean energy. In Australia, there is an established literature examining First Nations labour market participation and programs, especially focussed on unemployment and business formation, but a recent profile by Jobs and Skills Australia (2023b) is the only study of First Nations employment in clean energy. Noting these limitations, this section reviews existing literature to identify relevant insights for building First Nations employment in the clean energy sector.

A priority research area has been the consent and participation of First Nations people in renewable energy developments. Globally, many Indigenous communities continue to struggle for land rights, ownership and self-determination (Huff 2005), including land for renewable energy projects (Romanin Jacur, Bonfanti & Seatzu 2016, p.433) in both the Global South (Zanotelli 2016) and Global North (Scott & Smith 2017; Wade & Rudolph 2024). Clean energy and climate projects can exacerbate and entrench the socio-economic inequality of First Nations peoples sometimes referred to as ‘low-carbon colonialism’ (Sovacool 2021). Researchers highlight that it is crucial, to center First Nation rights in clean energy transitions, ensuring decision making is framed as a matter of social justice (Sovacool et al. 2016). O’Neill et al. (2021) advocate for the use of the legal concept of ‘free, prior and informed consent’ (FPIC) for agreement-making between renewable energy developers and First Nations peoples in settler-capitalist nations, encompassing protection of cultural heritage and promoting economic development including employment.

Another body of literature examines how renewable energy can lead to socio-economic benefits for First Nations communities (Schepis 2020). Some studies have focussed on the structural barriers to participation in renewable energy, such as the lack of energy knowledge, financial resources, property, racial inequality and discrimination (Keady et al. 2021). Other studies have examined the factors that can lead to a positive relationship between renewable energy projects and the well-being of remote Indigenous communities (Zapata 2024), such as project size, technology choice, community capabilities, and the integration of social, cultural and environmental considerations (Hunt et. al. 2021; Krupa 2012; Necefer et al. 2015). The role of the state in providing supportive policies is often highlighted as a key factor in driving positive outcomes (O’Neill et al. 2021, p. 5).

Ownership stakes in renewable energy projects have been associated with better outcomes. Fish and Nehme (2024) identify three types of ownership models: partial agreements between industry and Indigenous communities; Indigenous-led partnerships with non-Indigenous corporations; and Indigenous-owned renewable energy projects. Renewable energy projects (community and larger scale) led and owned by First Nations peoples bring increased sovereignty, agency and benefits (Hoicka, Savic & Campney 2021; Grosse & Mark 2023). Notably, almost half of renewable energy projects in Canada have Indigenous ownership (Hoicka et. al. 2021) and consequently many studies examine the factors enabling such (relative) high ownership (Leonhardt et al. 2023; Rioux-Gobeil & Thomassin 2024).

There is also a positive link between ownership and employment, directly and indirectly. Directly, studies have consistently found First Nations businesses employ higher numbers of First Nations workers with higher retention rates (Hunter & Gray 2016); the most recent econometric study concluded the First Nations employment rate was ‘at least 12 times higher’ (Eva et al. 2024). There are also qualitative case studies of employment creation in First Nations owned projects, such as the Atkin hydro-power project in Canada which created employment through an in-house training and skills program (Frangos et al. 2021). There can also be indirect employment benefits from First Nations ownership, where project earnings are reinvested in other First Nations businesses that create employment; for example, the First Nations-owned Tuaropaki Power Company, New Zealand used revenue from geothermal power stations to fund pastoral farming and dairy enterprises (Frangos et al.). Another indirect benefit is that First Nations staff are retained in First Nations organisations instead of working for external organisations which has flow-on benefits for community economic development (CEC & KPMG 2024).

However, there is a lack of studies on creating First Nations employment within renewable energy development which are not First Nations-owned. Existing studies demonstrate persuasively that economic and social benefits, including employment, will be highest where there is ownership, yet most renewable energy development will not be First Nations-owned. Consequently, it is also important to consider how to increase First Nations employment in renewable energy where there is no ownership stake.

There is an established literature on First Nations employment more broadly in Australia. Firstly, there is a body of studies profiling First Nations unemployment, labour market and training participation (Dockery & Milsom 2007; Windley 2017b; Jobs and Skills Australia 2022). Secondly, there is a body of studies evaluating the performance of employment service programs in reducing unemployment (Dockery & Milsom 2007; Windley 2017b; Jobs and Skills Australia et al. 2022) Most recently, there was a large-scale review of the Indigenous Skills Employment Program (NIAA 2021a, 2021b). Thirdly, there is a body of studies evaluating programs to provide employment in remote areas without developed labour markets (Dockery & Milsom, 2007). Fourthly, there are studies analysing First Nations employment within sectors such as mining (O’Faircheallaigh 2015; Parmenter & Barnes 2021; Jobs and Skills Australia 2023b, pp. 229–230).

From this literature, there are five major insights on how First Nations employment in clean energy might be increased:

1. There are common structural barriers to accessing training and employment, notably low educational attainment, poor health and disability, higher rates of incarceration, sub-standard or insecure housing, and access to transport (Dinku & Hunt 2019; Productivity Commission 2020; 2023).

2. Too often, programs with training courses without employer job commitments led to ‘training for training’s sake’, First Nations jobs-seekers accumulating ‘irrelevant’ lower-level qualifications which did little to improve their employment prospects (Windley 2017a, p. 3; 2017b). Training programs without firm job commitments by industry often fail to produce significant job creation (NIAA 2021b, p. 27).

3. Government procurement mandates have worked to increase demand for Indigenous businesses and employment. Since 2020, when First Nations business participation criteria were introduced, there has been a ‘marked increase’ in contracts to First Nations businesses and employment, totalling $6.2 billion to over 2,800 First Nations businesses (Productivity Commission 2020, p. 30). Procurement mandates have been the most effective mechanism for increasing First Nations employment.

4. Evaluations of programs for the unemployed have often noted data limitations but concluded that many of the jobs accessed were insecure, entry-level, and often temporary (Dockery & Milsom, 2007; Windley 2017b; Jobs and Skills Australia et al. 2022). Key factors that led to better results include quality, place-based training, initiatives to create culturally safe workplaces for First Nations people, with flexibility to meet family and community commitments, and on-going mentoring and support services to navigate common factors that lead to First Nations people leaving jobs (Giddy, Lopez & Redman 2009; Dinku & Hunt 2019; Productivity Commission 2020; NIAA 2021a, 2021b).

5. There is strong agreement that programs with high levels of First Nations community representation and influence are more effective, which is attributed to greater cultural expertise and connections to community. Indigenous-controlled organisations need to be central co-designers and partners in delivery of training, education, and employment services (NIAA 2021b, p. 10; Productivity Commission 2023).

Renewable Energy Zones: What is the Scope for Increasing First Nations Employment?

The REZs are integral sites to increasing First Nations employment in renewable energy. Much of the large-scale renewable energy development is planned for REZs, and they are also home to significant populations of First Nations Australians. Based on the 2021 census (ABS, 2021), the First Nations share of population averages 6% across the REZs, significantly higher than the national population share (3.8%). Some of the highest population shares for First Nations people are in REZs where the largest volume of renewable energy development is scheduled; notably, the two largest: the New England (NE) and Central-West Orana (CWO) REZs, NSW (9.4% and 12.7% respectively).

The question of whether there should be First Nations employment targets for renewable energy and if so, what level, is the subject of debate between industry, First Nations communities and governments. In the qualitative fieldwork, industry respondents were sceptical or opposed to employment targets in renewable energy for First Nations people on the basis that there is inadequate supply of suitable candidates with the right skills, qualifications, and experience. First Nations respondents and employment service providers on the other hand considered industry targets and commitments essential as a catalyst for change. From an advocacy position, some First Nations representatives argued that employment targets should be set commensurate with the share of population in the region.

There are three primary sources of First Nations labour supply for renewable energy within the REZs:

1. Existing workers in ‘renewable energy occupations’: First Nations workers in occupations commonly used in renewable energy with broad skills alignment that could be redeployed to work in renewable energy.2

2. Secondary school leavers: school leavers and young people (15-19-year-olds) could be new entrants into apprenticeships, traineeships and entry-level positions.

3. The unemployed or not currently in the labour force: unemployed people who are not in paid employment but who are actively looking for employment, or those who are ‘not in labour force’, people who are not in paid employment and who are not looking for work.

Our analysis compares the volume of potential First Nations labour supply from these segments against projected employment demand for renewable energy occupations within the REZs.

Whilst there are major uncertainties about future labour supply, there are several key findings. Firstly, the scope for the existing First Nations workforce to provide supply to the renewable energy sector is limited and concentrated in a small number of occupations. Secondly, the largest source of new labour supply are school students and youth if training and employment pathways into renewable energy can be created. Thirdly, whilst it is challenging, there is also an opportunity to create employment for those unemployed and not in the labour force. Fourthly, there are significant regional labour market variations which need to be considered in the design of any policy interventions. These suggest that policy needs to be nuanced and flexible to engage successfully with labour market circumstances.

The Existing First Nations Workforce: Low Presence in Renewable Energy Occupations

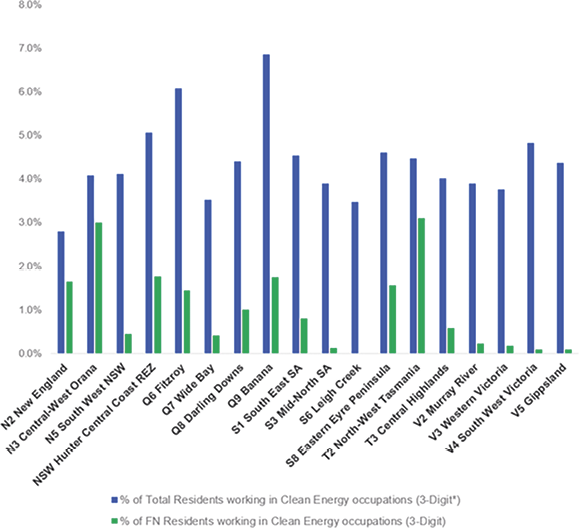

Most of the major sources of employment for First Nations Australians are in sectors with skills that are not well-aligned with renewable energy, such as health, administrative work and education (Jobs and Skills Australia 2022, p. 10). Consequently, the First Nations share of employment in renewable energy occupations across all industries is lower than the total population in every REZ and generally less than 2% (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Proportion (%) of REZ residents (First Nations and total population) in renewable energy occupations

Source: Author analysis of census data, ABS (2021).

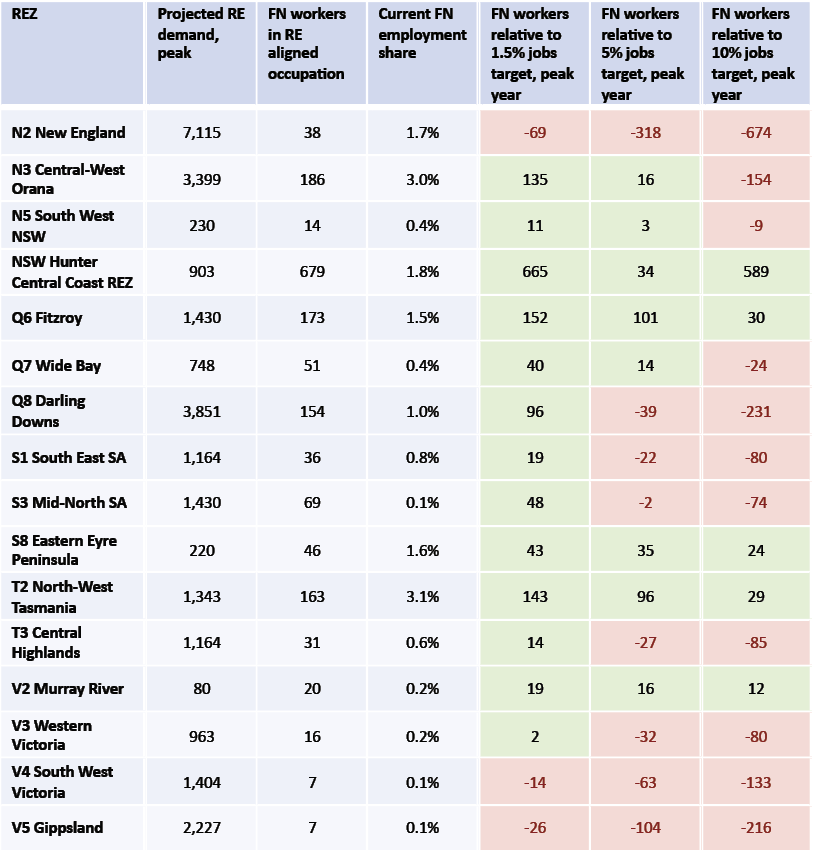

Comparing the volume of First Nations employees in these occupations with the peak employment demand year within each REZ (see Table 1), the key results are:

• In most REZs the volume of First Nations employees in renewable energy occupations, is greater than 1.5% of employment demand;

• there is an even split between REZs where there is sufficient and insufficient labour supply of First Nations employees to meet a 5% employment share;

• only in a minority of REZs is the First Nations labour supply greater than 10% of renewable employment demand.

Table 1. Current First Nations Workforce and Peak Renewable Energy Workforce Demand

Source: Author analysis, ABS (2021).

Note: red colour indicates deficit, green colour indicates surplus of labour supply relative to employment demand

However, the occupational composition of the First Nations workforce in renewable energy occupations is heavily concentrated amongst a couple of occupations in the REZs, especially truck drivers and labourers, followed by small numbers of mechanics, electricians, and construction trades. Additionally, in practice, only some fraction of the existing workforce would seek employment in renewable energy. Consequently, if there were to be redeployment from the existing workforce, it would mostly occur in lower-skilled jobs and is likely to be limited in practice.

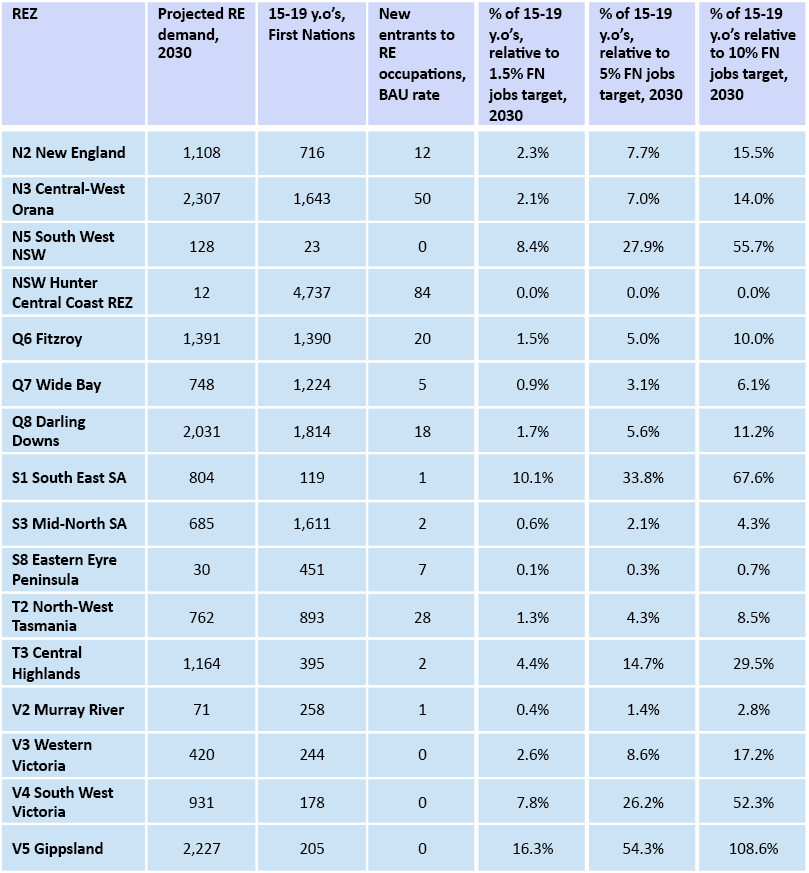

School Leavers: the major source of labour supply

The second source of labour supply could be school leavers and young people. Just over half of all First Nations residents in the REZs are aged 19-years or under, compared to just under one-quarter of the REZ population. The current (or business-as-usual) supply of new entrants into renewable energy occupations is low. However, in most REZs, if fewer than 5% of 15-19-year-old First Nations people entered renewable energy occupations, this alone would be equivalent to the minimum standard of 1.5% of renewable energy employment demand. For most REZs, less than 10% of First Nations youths entering the sector would alone be equivalent to 5% of renewable energy employment demand (Table 2).

Table 2. New workforce entrants from First Nations secondary students

Source: Author Analysis, ABS (2021).

Well-designed programs would be required to achieve these employment participation levels. The results indicate that if renewable energy could attract and train even modest proportions of First Nations students, this could make a large contribution to higher employment rates. Reflecting the importance of the school to training and work transition, the Australian Government has set a target under the ‘Closing the Gap’ initiative (target 7) to increase First Nations participation in employment, education, or training for 15-24-year-olds (NIAA 2023). Owing both to the volume of supply that could be created and the critical significance of this transition, young people should be a focal point of policy interventions to increase First Nations employment in renewable energy.

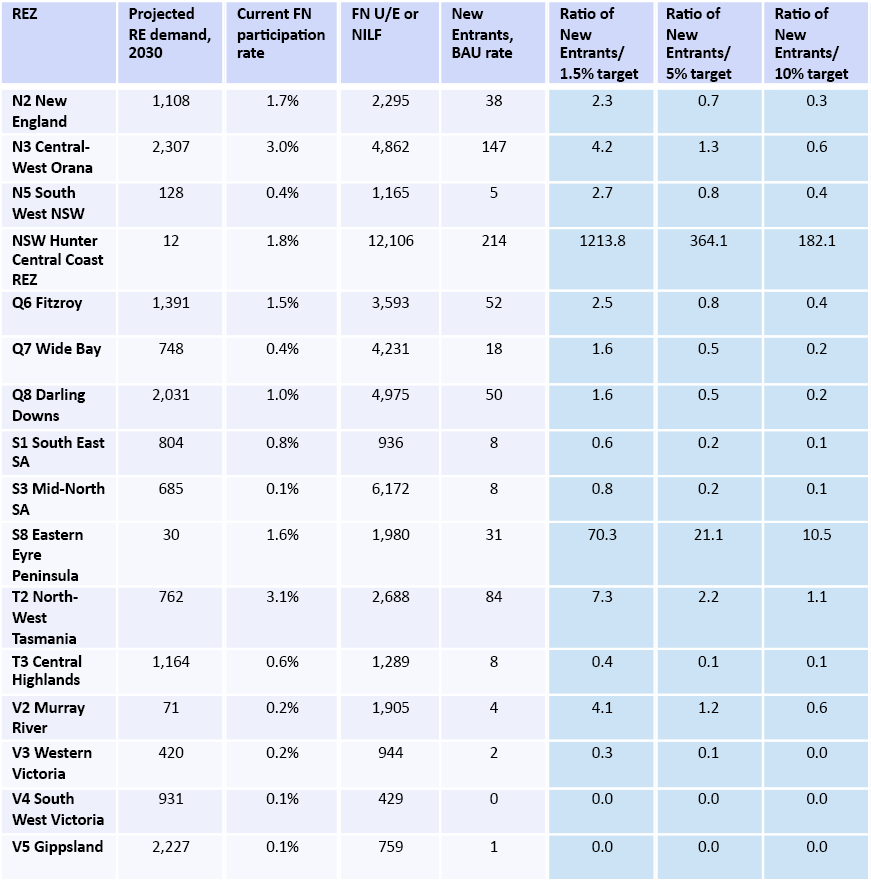

Unemployed and Those Not in the Labour Force

The third source of supply is the population currently unemployed or not in the labour force. There are major structural barriers to increasing participation amongst this cohort; however, there are cases of solar farms employing significant numbers of First Nations people from this cohort resulting in high social impact in communities with multi-generational unemployment (Australian Government 2024a).To understand the contribution this group could make to employment rates, it is assumed the participation rate in renewable energy occupations could be increased to the rate for the existing workforce which is generally 1-3% across the REZs. In most REZs, if this could be achieved, the volume of labour supply would be greater than the volumes required to achieve a 1.5% or 5% target (Table 3).

Table 3. New workforce entrants from the unemployed and not in the labour force

Source: Author analysis, ABS (2021).

The labour supply-demand analysis in the REZs highlights there are both major challenges and opportunities to increase First Nations employment in renewable energy. There is a limited skill-base in the existing workforce outside a handful of occupations, but programs to train and employ the unemployed and especially school leavers, could lead to employment rates of 5-10 per cent for First Nations people in many REZs.

How Can First Nations Employment in Clean Energy Be Increased?

Our research was unable to identify a holistic employment and training government strategy for First Nations peoples in renewable energy, either in Australia or internationally. In this context, our analysis highlights four key implications for policymakers on how to increase training and employment for First Nations:

1. Demand-side instruments (mandates, targets or incentives to increase industry employment or training for First Nations people) should be a key part of the policy toolkit, but need to be carefully and flexibly applied to avoid unintended consequences;

2. Whilst training-led programs have been identified as delivering poor results, investment in supply-side instruments (programs that increase the volume of First Nations people with the right qualifications and skills) needs to occur alongside demand-side instruments, especially focussed on school leavers;

3. Where possible, the integration of supply-side and demand-side mechanisms within climate and energy programs will deliver the best results;

4. Complementary measures to demand-side and supply-side instruments are likely to be required to achieve higher training and employment rates, such as resourcing industry and improving cultural safety in workplaces for First Nations people.

Demand-side instruments: a ‘coordinated flexibility’ approach

There is a range of policy instruments used by governments to increase industry investment in training or employment demand for under-represented groups. Some of the examples include:

• a minimum requirement in tenders for a percentage of the workforce to be a ‘learning worker’ (e.g. apprentices, trainees) or a specified group (e.g. First Nations);

• procurement incentives (e.g. tender criteria which reward higher levels of First Nations employment or contracts with First Nations businesses);

• voluntary targets; and

• wages or training subsidies for First Nations employees, trainees or apprentices.

There is an established case for the use of government interventions to address market failures associated with under-investment in training. Skill development is a public good which is often associated with under-investment by private firms due to the risks that they will not recoup the benefits of the investment if the worker leaves the firm (Keep 2006). For under-represented workers where there can be explicit or implicit forms of discrimination, low levels of industry understanding or experience with employing them, there is also an established case for the use of mandates to increase private sector investment in hiring of ‘learning workers’ to enable these groups to access training.

The Australian Skills Guarantee (ASG) places a requirement in procurement tenders for major construction and information technology projects to engage 1-in-10 workers to be a learning worker (apprentice, trainee or paid cadet) and engage a minimum proportion of women apprentices (Australian Government, Department of Employment and Workplace Relations 2024). Jobs and Skills Australia (2023a, p. 239) notes employer intakes of learning workers in clean energy need to increase and recommends applying the ASG as ‘one means of stimulating a training culture, and sustainable workplace conditions more broadly’.

Our research found strong, polarised views on the use of mandates and targets for First Nations employment and training in the renewable energy sector. In our fieldwork, there was universal, strong support for mandatory employment and training targets amongst First Nations stakeholders and employment service providers. Conversely, there was strong industry opposition to or scepticism about mandatory employment targets. The primary concerns expressed were:

• Where targets exceed the supply of trained First Nations workers, industry uses ‘accounting’ exercises in which projects find ways to meet targets (e.g. moving First Nations employees around between projects);

• industry focuses on employing First Nations people in low-skill jobs to meet targets instead of job creation across skill levels (trades, professions and managers) that require longer-term changes.

Whilst industry may be expected to highlight such concerns, the low First Nations labour supply across a range of renewable energy occupations in the REZs, validates that there are risks associated with a shortage in the supply of skilled candidates. The labour supply-demand analysis highlighted there are major regional variations which need to be considered in setting targets; for example, some of the REZs with smaller First Nations populations (e.g. the state of Victoria) have less opportunity than the REZs with higher populations and renewable energy development (e.g. the state of NSW).

There are also significant differences in the occupational and skill composition between technologies to be considered. Solar farms have higher volumes of entry-level jobs (e.g. labouring, cleaning, traffic management) than wind farms where most of the occupations require a vocational qualification and experience, such as electricians and mechanical technicians. Yet, whilst higher employment rates are possible, in our fieldwork, employment service providers said there was often no response from solar farms when approached, and First Nations community leaders in multiple regions angrily pointed to solar farms which had not employed any local First Nations people. Mandatory employment and training targets are better suited to solar farms than wind farms to realise employment opportunities for the unemployed.

Wind farm operators advocated for a coordinated industry program with voluntary targets as an alternative to short-term, mandated targets. There was strong interest amongst the interviewed wind farm operators for a coordinated industry program in collaboration with training and employment service providers to recruit and support First Nations apprentices:

‘I’ve been very keen to get Indigenous people into the business but it’s hard. It was pre-covid, 2017-18 … we had discussions about a PPA (power purchase agreement). Through that conversation, they were talking about indigenous employment which got us thinking about employing people in the service team in maintenance. It’s permanent, it’s a long-term contract and we need people, so it felt like a good opportunity … It’s difficult to find them, maintain them, make sure they’re getting what they want out of the role. It’s just so much harder. I found myself trying to dig through it. If we had a support network at industry level, then we could do that’ (Wind Original Equipment Manufacturer [OEM] 1).

‘(we’re) struggling to retain workforce, especially as we move into mining pockets … we’re lucky to get any trade attraction at all … It could be fitting and turning, auto, refrigeration mechanics – we have an apprenticeship scheme in place and other OEMs would as well …. If anybody can do a 5-day course (the Global Wind Organisation course) and climb a turbine they can become a trade assistant … There’s an opportunity for labour hire companies to target First Nations students with mechanical aptitude’ (Wind OEM 2).

‘A collaborative approach would be more effective as an industry than any business operating in isolation – all the main OEMs would be in favour of this coordinated approach … having some government direction will bring it to life much quicker’ (Wind OEM 3).

The view of industry leaders interviewed was that a program with voluntary, negotiated targets delivered in partnership with First Nations employment specialists, would work better than mandated employment targets. First Nations organisations could be engaged to build a pipeline of candidates, supply pre-employment training and on-going support services across a group of wind farm operators in a region. Voluntary targets would create a focal point for the initiative and a demonstration of business commitment, but they should be voluntary as building a cohort of First Nations apprentices could take time and learning from all parties as to how to make a program work. If mandatory targets were set, the risk is that wind farm operators would focus on how to achieve compliance but would not necessarily achieve a program that could deliver better results over the longer-term.

As an example of how such a model could work, the Infrastructure Skills Legacy Program in the state of New South Wales has combined voluntary targets for specific groups (apprentices, women), a mandatory minimum Aboriginal participation target (1.5%), and support measures for industry, to realise voluntary targets. To date, projects have averaged 26% apprentices and 7% Aboriginal employees. The program was piloted across 20 projects but has become standard practice for major government infrastructure projects after demonstrating to industry that the targets could be achieved (NSW Government 2023).

The scope of targets also needs to incorporate First Nations businesses. In addition to the literature reviewed on higher employment rates, some First Nations representatives and community members noted that renewable energy may be temporary, whereas contracts with First Nations-owned businesses can enable them to create a track-record that assists them secure contracts with other sectors and provides on-going employment.

Consequently, whilst there is a strong body of evidence to support the use of targets to increase employment demand, implementation needs to be well-designed to avoid unintended consequences. Firstly, a ‘coordinated flexibility’3 approach should be adopted which creates minimum benchmarks whilst enabling flexibility for implementation of higher targets at REZ level, reflecting variations between regions. Secondly, mandatory employment targets appear viable for solar farms where there is a higher volume of entry-level jobs but systems to employ First Nations people remain uncommon. Thirdly, the focus in wind farms could be on ‘learning worker’ targets and voluntary program models to build the pipeline of First Nations candidates. Fourthly, the application of any employment target should be implemented as part of a ‘participation’ target that recognises contracts with First Nations businesses as an alternative to direct employment.

Supply-side Instruments

There is a range of supply-side instruments available to increase the volume of First Nations candidates for jobs at entry-level, vocational qualified, and professional employment. Pre-employment training and support services alongside mandatory employment targets could increase the use of First Nations unemployed in solar farm construction. The probability of people, who have been out of the labour force for a long time or never worked, finding and maintaining employment, is increased with ‘wrap-around’ services that address circumstances which can prevent individuals getting and maintaining jobs (e.g. housing, family issues, etc). The importance of pre-employment training and support services to address barriers (e.g. acquiring construction site licences, soft-skills and so on) for First Nations job-seekers, is well-established (NIAA 2021a) and highlighted in renewable energy by employment results in solar farms (Australian Government 2024a).

In the context of renewable energy, there is a range of options to improve school to training transitions for First Nations school students such as:

• Outreach campaigns to raise awareness of the renewable energy sector: stakeholders noted the campaign would need to be well-designed to reach First Nations students, highlight connections between renewable energy and First Nations knowledge and culture and include exposure to the industry, such as site visits and ‘taste tester’ short courses;

• Establish defined pathways into training and employment: Jobs and Skills Australia (2023b, p. 138) has highlighted, the renewable energy sector currently makes limited use of ‘supported entry pathways’ such as school apprenticeships and pre-apprenticeship programs, especially for students;

• A review of First Nations cadetships programs in Australia concluded these programs had a ‘meaningful’ impact, increasing the probability of a successful transition from school to university, course completions, and employment (Inside Policy 2020, p. 12). Jobs and Skills Australia (2023a, p. 220) recently noted 80% of graduates that participated in a cadetship program were employed within 3 months of graduation. During the fieldwork, several First Nations employment specialists advocated for a specific cadetship program coordinated between clean energy firms, universities and governments (‘Career Trackers for Clean Energy’) for professional degrees such as engineering.

Integration of Supply & Demand Measures and Diversity Measures within Climate and Energy Programs

A review of diversity programs by the International Energy Agency (IEA) found outcomes are best when employment and training initiatives are integrated into the fabric of other policy domains that typically drive the change:

‘Many governments are investigating the development of training, re-skilling and educational programmes in anticipation of the upcoming changes. The most advanced programmes align energy, industrial, labour and education policies to jointly develop a strategy for energy transitions’ (IEA 2022, p. 12).

In Australia, it is striking to note how rarely this occurs in practice. For example, in Aboriginal housing retrofit program tenders, one state housing agency interviewed noted First Nations targets were used in procurement but mostly were not achieved because the program had focussed on rooftop solar and there are few First Nations electricians. Procurement targets were not being complemented by supply-side initiatives to increase investment in apprentices and therefore targets were not being met. Training is not incorporated into programs delivered by major agencies such as the Clean Energy Finance Corporation or the Australian Renewable Energy Agency.

In Canada, by contrast, training initiatives have been embedded within energy programs. Under the Regional Energy Advisor Training Program, Indigenous energy experts are trained to undertake energy audits in Indigenous housing. The program includes 100-hours of training over 8 months, audit kits, stipends and certification of auditors (Indigenous Clean Energy 2022; 2023). Under the Indigenous Off-Diesel Initiative, there is a training program to create ‘Energy Champions’ that supports Indigenous-led climate solutions in remote communities that use diesel or fossil fuels for heat and power (Government of Canada 2024). Where governments are delivering programs which create employment demand, there is an opportunity to embed training programs to simultaneously build the supply of First Nations people with the skills to work in clean energy.

Complementary Measures to Demand-side and Supply-side Instruments

Beyond the use of demand and supply instruments, complementary measures are likely to be required to address other barriers to increasing First Nations training and employment. Renewable energy firms are often trying to deliver projects in the context of skill shortages which could limit capacity to implement initiatives to increase training and employment opportunities for First Nations people and cultural safety in workplaces. Dedicated training staff provided by government could support industry to achieve higher First Nations training and employment. One of the key elements to the NSW Infrastructure Skills Legacy Program is embedding specialist training staff within projects to support them in identifying candidates and connecting to services (NSW Government 2023). Project managers need resourcing, if they are to achieve targets in practice.

Building workplaces that are ‘culturally safe’ is required, to ensure changes to training and employment are embedded. In the Australian context, the sector has acknowledged workplace practices need to be improved (CEC & KPMG 2024) to avoid discrimination and acknowledge the cultural responsibilities and practices of First Nations employees. Only 1-in-4 wind, or solar, developers has an organisational Reconciliation Action Plan.4 The commitment of resources and training is also required to create workplaces that can accommodate higher numbers of First Nations employees.

The literature review highlighted that outcomes are better with the involvement of First Nations organisations, but they also need resourcing. Industry and First Nations interviews, and workshop participants in our fieldwork, identified that First Nations organisations are stymied by a lack of resources and capacity to engage effectively with industry, both in employment-specific roles (e.g. identifying and supporting candidates) and more broadly in project development. Increasing the resourcing and capacity of First Nations organisations also needs to be undertaken to support the implementation of other measures.

Conclusion

The gap in access to stable, quality employment is one of the structural underpinnings of the socio-economic disadvantage for First Nations peoples. There is a growing recognition of the opportunity for the energy transition to contribute to reducing the employment gap in Australia, as much of the development of large-scale infrastructure is occurring either on land where there is an ownership stake or in regions where First Nations people have higher populations.

Our study contributes to understanding of the challenges, opportunities and policy options for increasing First Nations employment in renewable energy. The starting point for First Nations peoples is inequitable access to training and employment opportunities in the energy transition due to historically formed socio-economic disadvantage. A holistic employment and training strategy is required to address structural barriers to First Nations participation.

Use of procurement mandates and incentives should be a core part of any strategy, but they are contested and complex to implement. Wherever they are used, jurisdictions need to deploy a flexible approach that combines the use of minimum standards with variations in incentives and program models that match regional needs and technology workforce requirements. Initiatives to support the supply of First Nations workers in clean energy are unlikely to be successful on their own; instead, they will need to be implemented in parallel with procurement mechanisms to build the supply of skilled labour to meet targets. Purpose-built clean energy programs offer the best opportunity to increase employment and training where they can integrate the source of demand (e.g. tenders for housing retrofits) with supply-side initiatives. Finally, our study cautions that conventional approaches to employment policy (demand and supply mechanisms) could be insufficient to achieve change. Complementary measures to support the industry to achieve targets, change the culture of workplaces and increase the capacity of First Nations organisations to participate in the sector will enhance the effectiveness of labour market programs.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the valuable input of Jonathan Kneebone from the First Nations Clean Energy Network and the project’s Steering Group members: Peter Cowling (Mint Renewables), Chris Croker (First Nations Clean Energy Network), Trevor Gauld (Electrical Trades Union), Jo Haslam (TAFE NSW), Anthea Middleton (Powering Skills Organisation), and Adam West (TAFE NSW).

References

Australia Energy Market Operator (AEMO) 2024, AEMO’s Integrated System Plan (ISP). https://aemo.com.au/energy-systems/major-publications/integrated-system-plan-isp/2024-integrated-system-plan-isp

AEMO Services 2022, Guidelines-Tender Round 1 NSW Electricity Infrastructure Tenders. https://aemoservices.com.au/-/media/services/files/tender-round-1/t1_aemo_services_tender_guidelines_september_2022.pdf?la=en

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2021, Census, Canberra. https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/search-by-area

Australian Government 2024a, ‘Appendix A: First Nations Clean Energy Strategy – Case Studies. Best practice engagement: Beon Energy Solutions and Iberdrola Australia’, in Australian Government (ed.) The First Nations Clean Energy Strategy 2024-2030, pp. 9–11. https://www.energy.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-12/First%20Nations%20Clean%20Energy%20Strategy.pdf

Australian Government 2024b, Open CIS tenders, Tenders overview (Capacity Investment Schemes - CIS). https://www.dcceew.gov.au/energy/renewable/capacity-investment-scheme/open-cis-tenders.

Australian Government 2024c, The First Nations Clean Energy Strategy 2024-2030, Canberra. https://www.energy.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-12/First%20Nations%20Clean%20Energy%20Strategy.pdf

Australian Government, Department of Employment and Workplace Relations 2024, Skills Guarantee Procurement Connected Policy, May 2024 Canberra. https://www.dewr.gov.au/australian-skills-guarantee/resources/skills-guarantee-procurement-connected-policy

Briggs, C., Rutovitz, J., Dominish, E. & Nagrath, K. 2020, Renewable Energy Jobs in Australia: Stage One Research Team, Renewable Energy Jobs in Australia-Stage. Prepared for the Clean Energy Council by the Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney https://assets.cleanenergycouncil.org.au/documents/resources/reports/Clean-Energy-at-Work/renewable-energy-jobs-in-australia.pdf

Clean Energy Council (CEC) & KPMG 2024, Leading Practice Principles: First Nations and Renewable Energy Projects. https://cleanenergycouncil.org.au/getmedia/70a99026-8b0f-45d0-b987-be4e7f8d2d5f/leading-practice-principles-first-nations-and-renewable-energy-projects.pdf

Commonwealth of Australia 2023, Working Future; The Australian Government’s White Paper on Jobs and Opportunities, September. https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-09/p2023-447996-working-future.pdf

Dinku, Y. & Hunt, J. 2019, ‘Factors associated with the labour force participation of prime-age Indigenous Australians’, Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues, vol. 24, nos. 1–2, pp. 72–98. https://doi.org/10.25911/5DC3E4D902D9D

Dockery, A.M. & Milsom, N. 2007, A Review of Indigenous Employment Programs, NCVER, Adelaide. https://www.ncver.edu.au/__data/assets/file/0013/5044/nr4019.pdf

Eva, C. Hunter, B.H., Bodle, K., Foley, D. & Harris, J. 2024, ‘Closing the employment gap: Estimations of Indigenous employment in Indigenous- and non-Indigenous-owned businesses in Australia’, Economic and Labour Relations Review, vol.35, no.3, pp. 685-707. https://doi.org/10.1017/elr.2024.37

Fish, A. & Nehme, M. 2024, ‘Partnering for energy justice: Indigenous-corporate relationships in renewable energy industries in Australia’, Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, pp. 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646811.2024.2419187

First Nations Clean Energy Network (FNCEN) 2024, First Nations Energy Projects. https://www.firstnationscleanenergy.org.au/energy-projects

Frangos, M., Bassani, T., Hollingsworth, J. & Briggs. C, 2021, ‘First Nations Guidelines: Case Studies on First Nations community engagement for renewable energy projects.’ NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment. Sydney. https://www.energy.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-09/IEA%20Case%20Studies%20-%20June%202022.pdf

Giddy, K., Lopez, J. &Redman, A. 2009, Guide to Success for Organisations in Achieving Employment Outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, NCVER, Adelaide. http://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/2127.html

Government of Canada 2024, Indigenous Off-Diesel Initiative – Cohort 1. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/climate-plan/reduce-emissions/reducing-reliance-diesel/indigenous-off-diesel-initiative/iodi-cohort-1.html (Accessed: 28 January 2025).

Grosse, C. & Mark, B. 2023, ‘Does renewable electricity promote Indigenous sovereignty? Reviewing support, barriers, and recommendations for solar and wind energy development on Native lands in the United States’, Energy Research & Social Science, vol. 104, article no. 103243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103243

Hoicka, C.E., Savic, K. & Campney, A. 2021, ‘Reconciliation through renewable energy? A survey of Indigenous communities, involvement, and peoples in Canada’, Energy Research & Social Science, vol. 74, article no. 101897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101897

Huff, A. 2005, ‘Indigenous land rights and the new self-determination’, Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy, vol.16, no. 2, p. 295-332. https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/celj/vol16/iss2/3

Hunter, B. & Gray, M. 2016, ‘The ins and outs of the labour market: employment and labour force transitions for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians’, CAEPR Working paper No. 104/2016. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research. Australian National University, Canberra. https://caepr.cass.anu.edu.au/research/publications/ins-and-outs-labour-market-employment-and-labour-force-transitions-0

International Energy Agency (IEA) 2022, Skills Development and Inclusivity for Clean Energy Transitions. https://www.iea.org/reports/skills-development-and-inclusivity-for-clean-energy-transitions

Indigenous Clean Energy 2022, Energy Foundations: The Value Proposition for Financing Energy Efficient Homes in Indigenous Communities Canada-Wide, Indigenous Clean Energy, Ottawa. https://indigenouscleanenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Energy-Foundations-Report-FINAL.pdf

Indigenous Clean Energy 2023, Enabling Efficiency: Pathways and recommendations based on the perceptions, barriers, and needs of Indigenous people, communities, and organizations. Indigenous Clean Energy, Ottawa. https://indigenouscleanenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Enabling-Efficiency-Report-December-2023.pdf

Inside Policy 2020, Evaluation of the Indigenous Cadetship Support (ICS) and Tailored Assistance Employment Grants (TAEG) Cadets Programs. 24 June. Report produced for the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA). https://www.niaa.gov.au/resource-centre/indigenous-cadetship-support-and-tailored-assistance-employment-grants-cadets

Jobs and Skills Australia 2023a, The Clean Energy Generation Workforce needs for a net zero economy. https://www.jobsandskills.gov.au/download/19313/clean-energy-generation/2385/clean-energy-generation/pdf

Jobs and Skills Australia 2023b, First Nations People Workforce Analysis. Canberra. Available at: https://www.jobsandskills.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-06/First%20Nations%20People%20Workforce%20Analysis.pdf (Accessed: 2 February 2025).

Keady, W. Panikkar, B., Nelson, I. & Zia, A. 2021, ‘Energy justice gaps in renewable energy transition policy initiatives in Vermont’, Energy Policy, vol. 159, article no. 112608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112608

Keep, E. 2006, for Sector Skills Development Agency (Great Britain) (SSDA), Market Failure in Skills, SSDA, Wath-upon-Dearne, England.

Klein, E. 2020, ‘Settler colonialism in Australia and the cashless debit card’, Social Policy & Administration, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12576

Krupa, J. 2012, ‘Identifying barriers to aboriginal renewable energy deployment in Canada’, Energy Policy, vol. 42, pp. 710–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.12.051

Leonhardt, R., Noble, B., Poelzer, G., Belcher, K. & Fitzpatrick, P. 2023, ‘Government instruments for community renewable energy in northern and Indigenous communities’, Energy Policy, vol. 177, article no. 113560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113560

Necefer, L., Wong-Parodi, G., Jaramillo, P. & Small, M. 2015, ‘Energy development and Native Americans: Values and beliefs about energy from the Navajo Nation’, Energy Research & Social Science, vol. 7, pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.02.007

Net Zero Australia 2023, Net Zero Mobilisation report: How to make net zero happen, 12 July. https://www.netzeroaustralia.net.au/mobilisation-report/

NIAA 2020, Indigenous Procurement Policy, December 2020. https://www.niaa.gov.au/resource-centre/indigenous-procurement-policy

NIAA 2021a, Indigenous Skills, Engagement and Employment Program (ISEP). Canberra. https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/publications/isep-discussion-paper.pdf

NIAA 2021b, The Indigenous Skills & Employment Program. Consultation Outcomes Report. https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/publications/isep-consultations-report-26-october-2021.pdf

NSW Government 2023, Infrastructure Skills Legacy Program. https://www.nsw.gov.au/education-and-training/vocational/vet-programs/infrastructure-skills

O’Faircheallaigh, C. 2015, ‘social equity and large mining projects: Voluntary industry initiatives, public regulation and community development agreements’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 132, pp. 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2308-3

O’Neill, L., Thorburn, K., Riley, B., Maynard, G., Shirlow, E. & Hunt, J. 2021, ‘Renewable energy development on the Indigenous Estate: Free, prior and informed consent and best practice in agreement-making in Australia’, Energy Research & Social Science, vol. 81, article no. 102252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102252

Parmenter, J. & Barnes, R. 2021, ‘Factors supporting indigenous employee retention in the Australian mining industry: A case study of the Pilbara region’, The Extractive Industries and Society, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 423–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2020.11.009

Productivity Commission 2020, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage. https://www.pc.gov.au/ongoing/overcoming-indigenous-disadvantage

Productivity Commission 2023, Draft report - Review of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/closing-the-gap-review/report/closing-the-gap-review-report.pdf

Rioux-Gobeil, F. & Thomassin, A. 2024, ‘A just energy transition for Indigenous peoples: From ideal deliberation to fairness in Canada and Australia’, Energy Research & Social Science, vol. 114, article no. 103593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2024.103593

Romanin Jacur, F., Bonfanti, A. & Seatzu, F. 2016, ‘Concluding Observations’, In Romanin Jacur, F., Bonfanti, A. & Seatzu, F. (eds.) Natural Resources Grabbing: An International Law Perspective, Brill Nijhoff, Leiden, pp. 427-433. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004305663_022

Rutovitz, J., Gerrard, E., Lara, H. & Briggs, C. 2024, The Australian Electricity Workforce for the 2024 Integrated System Plan: Projections to 2050. Prepared for Race for 2030. https://racefor2030.com.au/content/uploads/NEM-2024-Workforce_FINAL.pdf

Rutovitz, J., Langdon., R, Mey, F. & Briggs, C. 2022, The Australian Electricity Workforce for the 2022 Integrated System Plan: Projections to 2050. Prepared for Race for 2030. https://www.racefor2030.com.au/project/australian-electricity-workforce-for-the-2022-integrated-system-plan/

Schepis, D. 2020, ‘Understanding Indigenous Reconciliation Action Plans from a corporate social responsibility perspective’, Resources Policy, vol. 69, article no. 101870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101870

Scott, D.N. & Smith, A.A. 2017, ‘Sacrifice zones in the Green Energy Economy: The “new” climate refugees’, Transnational Law & Contemporary Problems, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 371-381.

Sovacool, B.K. 2021, ‘Who are the victims of low-carbon transitions? Towards a political ecology of climate change mitigation’, Energy Research & Social Science, vol. 73, article no. 101916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.101916

Sovacool, B.K., Heffron, R., McCauley, D. & Goldthau, A. 2016, ‘Energy decisions reframed as justice and ethical concerns’, Nature Energy, vol. 1, article no. 16024. https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.24

Stead, V. & Altman, J.C. 2019, ‘Labour lines and colonial power’, in Stead, V. & Altman, J. C. (eds.), Labour Lines and Colonial Power; Indigenous and Pacific Islander Labour Mobility in Australia, ANU Press, Canberra, pp. 1-26. https://doi.org/10.22459/LLCP.2019

Wade, R. & Rudolph, D. 2024, ‘Making space for community energy: landed property as barrier and enabler of community wind projects’, Geographica Helvetica, vol. 79, no. 1, pp. 35–50. https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-79-35-2024

Windley, G. 2017a, Indigenous VET Participation, Completion and Outcomes: Change over the Past Decade, NCVER, Adelaide. www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/publications/all-publications/indigenous-vet-participation-completion-and-outcomes-change-over-the-past-decade

Windley, G. 2017b, Policy snapshot - Indigenous training and employment, NCVER, Adelaide. https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/publications/all-publications/policy-snapshot-indigenous-training-and-employment

Zanotelli, F. 2016, ‘(Un)sustainable wind: Renewable energy, politics and ontology in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Mexico’, Anuac, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 159-194. https://doi.org/10.7340/anuac2239-625X-2589

Zapata, O. 2024, ‘Renewable energy and well-being in remote Indigenous communities of Canada: A panel analysis’, Ecological Economics, 222, article no. 108219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108219

1 For the methodology and results of the employment modelling, see Rutovitz et al. (2022).

2 Based on industry surveys (Briggs et al., 2020), the list of ‘renewable energy occupations’ used for the analysis was:

• Construction, Distribution, and Construction Managers

• Engineering Professionals

• Health Diagnostic and Promotion Professionals

• Building and Engineering Technicians

• Electricians

• Truck Drivers

• Construction and Mining Labourers

• Miscellaneous Labourers

• Mechanical Engineering Trades Workers

• Automotive Electricians and Mechanics

• Occupational and Environmental Professionals

3 The term ‘coordinated flexibility’ is adopted from an approach used in European wage bargaining whereby industry-level agreements set overall parameters and workplace bargaining negotiates detailed arrangements to enable some flexibility.

4 AEMO publishes a list of renewable energy projects which is available here: https://aemo.com.au/energy-systems/electricity/national-electricity-market-nem/nem-forecasting-and-planning/forecasting-and-planning-data/generation-information. We conducted an online search for all the listed solar and wind farm project developers that had a ‘Reconciliation Action Plan’, a strategic framework for organisations to create opportunities for First Nations Australians which is developed and registered with Reconciliation Australia. See https://www.reconciliation.org.au for more information.