Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 17, No. 1

2025

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

(Im)mobility and Environmental Change in the Coastal Sinking Cities of Java, Indonesia

Wiwandari Handayani1,*, Citra Tatius2, Felicitas Hillmann3, Amy Young4, Landung Esariti5, Laely Nurhidayah6

1 Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, Indonesia, wiwandari.handayani@live.undip.ac.id

2 Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, Indonesia, citratatius@gmail.com/cure.ft@live.undip.ac.id

3 Technische Universität Berlin; Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, Indonesia, hillmann@tu-berlin.de

4 Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia, amy.young@griffith.edu.au

5 Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, Indonesia, landungesariti@lecturer.undip.ac.id

6 Research Center for Law, National Research and Innovation Agency, Jakarta, Indonesia, lael003@brin.go.id

Corresponding author: Wiwandari Handayani, Universitas Diponegoro, Jl. Prof. Soedarto, Tembalang, Kota Semarang, Jawa Tengah 50275, Indonesia, wiwandari.handayani@live.undip.ac.id

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v17.i1.9414

Article History: Received 23/10/2024; Revised 26/02/2025; Accepted 11/03/2025; Published 31/03/2025

Citation: Handayani, W., Tatius, C., Hillmann, F., Young, A., Esariti, L., Nurhidayah, L. 2025. (Im)mobility and Environmental Change in the Coastal Sinking Cities of Java, Indonesia. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 17:1, 64–80. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v17.i1.9414

Abstract

Environmental degradation induced by climate change disturbs livelihoods and is, therefore, a critical issue in policy and academic discourses on immobility. This paper aims to investigate experiences of immobility in three coastal areas within Indonesian cities of varying adaptive capacities, with a focus on women who represent vulnerable people whose role can be attributed to policies and governance. We adopted a qualitative methodological approach, combining ethnography and utilizing in-depth interviews with a total of 60 respondents, and roundtable discussions representing various stakeholders. Three locations, i.e., Muara Angke, Tambak Lorok, Panjang Wetan, were selected because the residents experience immobility despite massive environmental pressures. Direct and indirect adaptive capacities can lead to more equitable opportunities for residents to choose between staying or moving out and thereby may promote increased mobility justice. We highlight ways in which policy and political governance can better support impacted areas and invest in capacity-building among at-risk populations.

Keywords

Immobility; Climate Adaptation; Environmental Change; Sinking Cities; Java

Introduction

Mobility and immobility are interconnected. Global mobility has intensified with advances in information technology and transportation. While mobility is notably uneven (Sheller 2018), raising important questions regarding mobility justice, it continues to be a fundamental aspect of development activities. The regulation of mobility and related issues is apparent in the SDGs (Piper & Datta 2024). Long-term mobility, such as migration, often occurs as a consequence of specific processes in places of origin (e.g., war, disasters, and economic reasons) while promising locations of destination are often associated with potential income and job opportunities. Early models such as Lee’s (1966), inspired by push-pull migration theory, stated that economic factors are a primary consideration for people to move from one place to another in various patterns, while obstacles arise from family considerations, social ties and cost constraints as well as concrete infrastructures (such as borders). In contrast, contemporary scholarship points to the often invisible factors that regulate international mobility, with a focus on established hierarchies, producing different regional mobility regimes. Here, mobility is conceptualized as one dimension of global inequality (Sheller 2021) – and so is immobility.

Building on mobility and immobility scholarship, this paper aims to investigate experiences of immobility in three coastal areas within Indonesian cities of varying adaptive capacities, with a focus on women who represent vulnerable people whose role can be attributed to policies and governance. Our first case, Muara Angke is a dense fishing community in Jakarta, a megapolitan area with over 10 million people. Our second case, Tambak Lorok in Semarang represents a fishing community in a metropolitan city with approximately 1.7 million inhabitants (CBS 2023). Our third case, Panjang Wetan in Pekalongan, is a medium-sized city (less than 300,000 inhabitants) experiencing rapid industrialization in the neighboring district. These coastal cities have experienced coastal flooding, primarily caused by land subsidence that occurs frequently and has been progressively surpassing the sea level rise that typically amounts to a few millimeters per year (Harintaka et al. 2024). Land subsidence plays a major role in increasing environmental hazards, and goes hand in hand with sea level rise. Immobility, we argue, is a preferable option for residents in the selected study areas as they have developed different strategies for in situ adaptation. Policy and governance have also played a role in influencing immobility and in supporting local capacity building.

Theoretical Framework: Mobility and Immobility

Contemporary research emphasizes mobility and migration as a key aspect of broader social change, reflecting the interaction between agency and structure (Hillmann 2010; de Haas 2021). According to de Haas (2021, pp. 18f), ‘Migration aspirations are a function of people’s general life aspirations and perceived geographical opportunity structures’ and Migration capabilities [as] contingent on positive (‘freedom to’) and negative (‘freedom from’) liberties’. Here, the impact of environmental change on livelihoods would be considered as a part of the structural conditions, which influence capabilities. Further, Cundill et al. (2021) and Kaczan and Orgill-Meyer (2020) highlight that mobility provoked by environmental change is likely to manifest as internal mobility, with migrants moving shorter distances within countries (see paper by McLeman, this issue).

Despite extensive academic literature on mobility, including migration and mobility behaviors, relatively few studies offer detailed examination of why some individuals decide to stay put in stagnant and declining regions (Transiskus & Bazarbash 2024; Bergmann & Martin 2023; Boas et al. 2022; Zickgraf 2019; Hugo 2005). Environmental degradation driven by climate change is recognized as a critical issue in immobility discussions. Hoffmann et al. (2020) state that climate-related disasters are likely to result in immobility rather than mobility for the affected populations. Carling (2002), a pioneer in studying immobility, argues that poverty is a major contributor for individuals to remain in at-risk areas. Individuals in at-risk areas may be motivated to migrate to seek greater income, however migrating requires an initial financial investment to prepare to migrate and develop marketable skills (Zickgraf 2019). Hillmann et al. (2015) argue that processes of immobility are tied to regional patterns and policies at international, national, provincial and local scales. Government provides policy and regulation to minimize the risk to disaster prone areas. This leads to various adaptive strategies that influence individual decision making. The Foresight Report (2011) was first to come up with the notion of ‘trapped populations’, putting emphasis on the involuntary dimension of staying in place.

Rigaud et.al. (2018) categorize mobility in the context of climate or environmental change into three main types: migration (general longer-term movement), displacement (forced to move), and relocation (voluntary as part of government program). Immobility is further classified into two groups: people who choose to stay voluntarily and those who feel trapped, desiring to move but lacking the knowledge, financial resources, or capacity to do so. The lens of mobility justice helps to understand various types of immobility in its regional embeddedness. It situates immobility within policy discussions on adaptive capacity and focuses on the strengths of communities, rather than focusing exclusively on immobility as a community deficit, or as a result of the inability to access secure situations and connectivity. Many individuals opt to remain in place; even when they have the option to leave, they seem to prefer to stay put because of their attachment to the area and social ties. Bergmann and Martin (2023) assert that place attachment, social values, and cultural motives are significant reasons for individuals becoming immobile or demonstrating a preference to stay. Amin et al. (2021) classify the factors influencing immobility into four aspects: place attachment, family ties, social ties, and occupational ties.

Compared to rapid-onset events, slow-onset degradation has received less attention in terms of its linkages to migration and mobility (IPCC 2022). It is known that immobility is exacerbated by climate impacts stemming from slow-onset climate disasters, such as tidal inundation and droughts (Ober 2019). Such slow onset disasters may provide individuals with the opportunity to prepare their adaptation strategies, leading to a better adaptive capacity than responses to rapid onset disasters, which are more likely to force migration or displacement. In general, immobility is presented as an undesired decision, rooted in the discourse of migration as an expected adaptation action or part of an adaptation strategy (Blondin 2021). Boas et al. (2022) argue that much research reveals that climate migration is no longer relevant, as most mobility resulting from environmental changes is context-specific and involves primarily local mobility rather than widespread migration. Ober (2019) further explains that most slow-onset disasters lead to either local movement or even temporary mobility. People tend to protect their assets and remain in place due to their livelihoods.

Gender is an important dimension to consider in studies of mobility and immobility. For example, in the Global South including in Bangladesh (Ayeb-Karlsson 2020), women are likely to stay in situ, while men tend to migrate to earn money for their families. Bergmann and Martin (2023) categorize immobility into voluntarily and involuntarily (trapped) types based on individuals’ capabilities and aspirations. Various factors influence these categories, including policies, power dynamics within families and communities, gender roles, economic conditions and place attachment. In many migration studies, immobile people are often viewed as part of the impact of migration, receivers of remittances, or as ‘left behind’ family members (Zickgraf 2019).

This paper investigates to what extent the adaptive capacity derived from policy and governance gives nuance to experiences of immobility in the selected research areas. The next section describes the context and methodology, including the study area, data collection and analysis. The results are divided into sections that elaborate on the detailed profiles and evidence of immobility in each case study area. We then discuss and compare the characteristics and immobility across the three sites. In conclusion, we reflect on the findings in light of the theoretical framework and draw conclusions on migration governance from comparison.

Context and Methodology

The concept of immobility is highly relevant for examining the regional situation in Java, Indonesia. Java Island is home to 56.19% of Indonesia’s population, despite accounting for only 7% of the total land area of the 17.000 islands that make up the archipelago (CBS, 2021). Much of the northern coast of Java is prone to various climate disasters (Sejati et al. 2024; Handayani et al. 2020; Buchori et al. 2018). This situation is exacerbated by rapid urbanization. Cities are growing. Simultaneously sinking due to rising sea levels and, in certain locations, land subsidence from groundwater extraction (e.g., groundwater pumping) are a consequence of this population growth and massive industrialization (Handayani et al. 2020). According to Bott et al. (2021), the sinking rate of some cities along the northern coast of Java is up to 15 cm per year, resulting from the combination of sea level rise and land subsidence. For years, vulnerable individuals in these areas have been surviving and adapting to environmental degradation. National, provincial, and local governments have been addressing the needs of impacted households by providing relocation programs aimed at improving environment quality. However, relocation opportunities are often not regarded as viable options by the resident population (Amin et al. 2021).

Study Areas

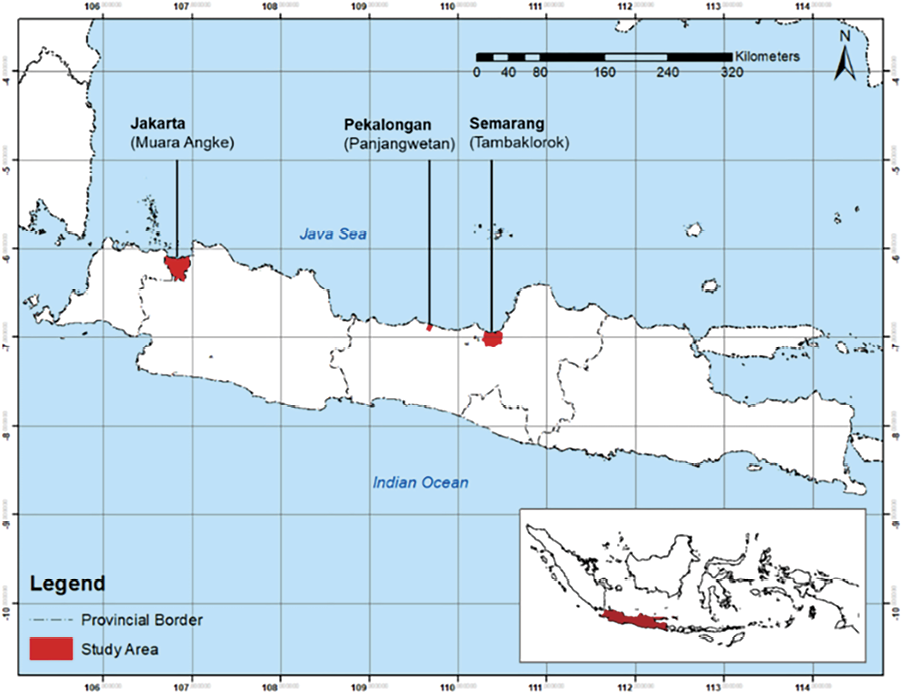

This study was conducted in three different urban villages located within three larger cities in the coastal areas of Java: Muara Angke in Jakarta, Tambak Lorok in Semarang, and Panjang Wetan in Pekalongan (see Figure 1). On average, the three selected locations experience sea level rise ranging from 3-10 mm per year, with Pekalongan experiencing the highest rate at 10.6 mm per year (Andari et al. 2023), followed by Semarang at 6-10 mm per year (Astuti & Handayani 2020), and Jakarta at the lowest rate of approximately 3.8 mm per year (Karlina & Johan 2023). However, compared with the simultaneously occurring land subsidence rate, Jakarta and Semarang tend to have higher rates exceeding 10 cm per year (Harintaka et al. 2024) along with Semarang with 10-12 cm per year (Aditiya & Ito 2023), followed by Pekalongan with 5.37 cm per year (Andari et al. 2023). These data reveal that the land subsidence rate is significantly higher than sea level rise, though the cumulative impacts need to be taken into account.

We now provide a brief description of the three selected urban villages. Muara Angke is located in the northern coastal area of Jakarta, the capital city of Indonesia, approximately 10 kilometers from the city center. It is predominantly inhabited by new migrants, primarily from a group known as RCTI (Rombongan, a group from Cirebon-Tegal-Indramayu), which consists of residents from regencies located along the coastal areas of West Java Province. These migrants initially settled in the area during the 1980s. As of 2021, the population was 16,973 people, with 93% employed in the fishery sector (CBS 2022). Men typically work as fishers, while women remain on land to work as mussel peelers. Near the port area of Muara Angke, the population density is high with, accordingly high levels of mobility (Putri et al. 2021). This well-known fishing settlement covers approximately 72 hectares and offers ample opportunities for fishers. Yet it is significantly affected by climate change, including sea level rise, land subsidence, and heavy rainfall. During severe storms, inundation depths can reach 0.5-1 meter, exceeding 3 meters in some locations, particularly around the Muara Angke Fish Market (Bennett et al. 2023), making settling in these areas difficult.

The Tambak Lorok fishing settlement is located in the Tanjung Mas subdistrict of Semarang. This area spans 46.8 hectares and includes a fishing port, which serves as the main fishing port in Semarang, along with a newly restored fish market, making it a densely populated fishers village located 5 kilometers from the city center. According to data from the subdistrict office from 2024, around 9,024 people reside in this area. Most are employed in the fishery sector, working as fishers, fish sellers at the auction market, green mussel peelers, or in the construction industry or home-based garment sewing. Due to its geological characteristics and location near the downstream area of the Barang River, Tambak Lorok not only experiences sea level rise and land subsidence but is also frequently hit by riverine floods (Astuti & Handayani 2020). It is a neighbourhood that has received much attention from the respective government agencies and has benefitted a range of interventions from the side of NGOs, municipal stakeholders, and university researchers (Hillmann & Handayani 2024).

Panjang Wetan is one of the coastal subdistricts in Pekalongan, covering approximately 158 hectares and is home to 12,331 residents. The majority of the population works in the fishery sector. However, with Pekalongan being known for its world-renowned batik industry and its strategic location, only 1 kilometer away from the city center, a significant number of the residents is also employed in sewing, through small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and in the garment industry. This site once hosted the largest fish auction market in Southeast Asia, with a daily turnover of IDR 500 million to 1 billion (USD 30,000-60,000). But due to tidal flooding caused by climate change, it no longer retains that status. Located near the Loji River, water can easily inundate the area, causing water levels to rise between 45 and 100 cm, which can take 1 to 2 days to recede (Utami et al. 2021).

Figure 1. Selected Study Areas Source: Geospatial Information Agency (BIG), 2024.

https://tanahair.indonesia.go.id/portal-web/

Research Design & Data Collection

This study uses a qualitative approach, combining ethnography with in-depth interviews and roundtables. Initially, participant observation helped us to better understand the research setting and to approach key stakeholders in the field. A total of 60 respondents were interviewed, with 20 participants from each site. Given the focus on the gendered impacts of climate change and migration, only female participants were invited to participate in the interviews. Snowballing was applied, with recruitment initiated by a local Non-Government Organisation that works within the communities. The respondents represent various sectors, including fishpond farmers, fishers, prawn and mussel peelers, SME business owners and workers, and even industrial laborers who continue to reside in the area despite the environmental hazards caused by climate change. The interviews provided insights into the attractiveness of staying in these locations from the viewpoints of local residents based on their current occupations. As a collaborative research project supported by the Indonesian and Australian Government, this study received ethical approval from Indonesian and Australian human research ethics committees.

To gain deeper insights and verify the findings, a series of roundtable discussions were held in Muara Angke, Tambak Lorok, and Panjang Wetan. These discussions aimed to engage stakeholders in addressing the issue of immobility as a response to climate change. According to Pennel et al. (2008), roundtables can be used to identify the perspectives from both people with direct experience of a problem and people who attempt to intervene and address the problem. The roundtables enabled the researchers to develop a holistic understanding of mobility and immobility challenges as a possible adaptive strategy from the perspective of policy makers and community members. Participants were purposively sampled, with a balance of gender and job title.

Two sessions were held in each city, one for government representatives and one for community representatives. Participants came from diverse backgrounds, including experts, government officials, academics, and local community members. The selection of participants was based on their involvement in climate-related issues within the context of immobility. Government informants were chosen from policymakers who were responsible for disaster management, community development (particularly on women and children as vulnerable people), employment, and settlement planning that facilitates infrastructure provision. Community informants were selected from groups representing diverse societal segments, including youth, women, workers, disaster resilience groups, and organizations actively engaged in decision-making and facilitating community development. Their diverse backgrounds and active participations provided broad insights, aligned with the aim of roundtables to gather various perspectives on complex issues. Given that Jakarta serves as the national capital, stakeholders from the national government were included in the discussions to provide comprehensive considerations for decision-making. Similarly, representatives from the provincial government participated in the Semarang roundtable session, as it is the capital of Central Java. Each session had 10 to 20 participants.

Data Analysis

The interviews and roundtables were recorded, then transcribed and translated from Bahasa Indonesia into English. Each respondent was given a code in the transcriptions during the de-identification process and anonymisation. Coding is employed to assign identifiers to respondents, facilitating the organization of their answers by location and stakeholder type within the framework of the roundtable session. Additionally, among respondents from the same city and stakeholder type, distinct individuals are differentiated using the letters ‘a’ or ‘b.’ This systematic labelling approach ensures anonymity while enabling a structured comparison of perspectives. After coding, thematic analysis was conducted, following Braun and Clarke’s (2013) methodology. The themes encompass factors related to respondents’ experiences concerning environmental changes in their neighborhoods, livelihood, gender roles, policy impacts, and decisions regarding whether to stay or move.

Findings

This section presents the findings on environmental changes in the study locations and their impact on local communities. We examine the reasons influencing the communities’ decision to stay in place, i.e. immobile, despite the environmental challenges they face. Moreover, we discuss various in situ adaptation initiatives both provided by the government and developed by the community.

Immobility in Muara Angke, Jakarta

Muara Angke began to develop in the early 1980s when the first generation of fishermen from the neighbouring areas, known as RCTI, established a fishing settlement on government-owned coastal land (Figure 2). Located in the capital city with high demand for fish and its derivative products, these migrant urban villages grew rapidly, transforming into a dense community within less than a decade. As an attractive destination for employment in the fishery sector, particularly as fishing vessel crew or fish sellers, today Muara Angke continues to draw migrants from surrounding coastal regions seeking job opportunities as informal blue-collar workers due to limited prospects in their places of origin. This means that incoming migration to urban areas is strongly driven by income opportunities. Even during extreme weather conditions that hinder fishermen from going to sea, alternative livelihoods are available. Some individuals shift their work to construction sites to maintain stable household income.

Environmental change has brought several impacts on livelihoods in Muara Angke. Polluted floodwaters contribute to skin diseases among the local population, extreme weather causes hazardous working conditions that increases the risk of accidents or even death for those working at sea. Air pollution, due to the burning of plastic and non-existent waste management, in the crowded harbour area exposes workers to respiratory health issues. It severely damages properties. However, these challenges do not seem to motivate residents to migrate from this area. The people of Muara Angke have expressed strong resistance to proposals for migration or relocation, often due to traumatic associations with past experiences. Previous relocations were typically linked to violent actions by the government, forcing them to move out (e.g., by spraying hazardous gas in their homes). National and local governments have made efforts to enhance public infrastructure, primarily aimed at addressing tidal floods. These efforts also include relocation programs designed to assist affected residents. However, they are likely to refuse relocation mainly because the alternative housing provided by the government consists of mid-rise apartments (typically 3–5 storeys), rather than ground-level housing and located far from the sea, which is essential for their livelihoods in the fishery sector. Additionally, strong social ties are considered another reason for their voluntary decision to stay.

Figure 2. Mussel Peeling Spot and Fish Harbors as Forms of Livelihood in Muara Angke

Source: Authors, 2024

I might be the person who has been relocated the most here. I have experienced many relocations since I was a child, and I ended up in this place in Muara Angke. At first, we refused to live here. It is a cursed place, many people said. I was forced by the government to move here, along with another 3 households, including my parents and me when I was a child. That’s why, now, if the people and I were asked to leave Muara Angke, forget it; Muara Angke will be the last place where I live. (Informant J1)

The community roundtable session confirmed that the immobility of Muara Angke residents is related to their attachment to their homes and their livelihoods in the fishery sector. They continue with their daily work despite facing economic downturns and various environmental hazards. They choose to stay even as living costs rise, necessitating the elevation of their houses due to sea level rise and land subsidence. Meanwhile, the government roundtables indicated that relocation remains an option, as climate impacts persist and may lead to further environmental degradation.

It is difficult for the community to change their habits, shifting their working pattern from being fishers or mussel peelers to living in vertical housing, especially since the new houses are far from the sea. This forces them to incur extra commuting costs if they wish to continue working at sea. In some cases, those who have been relocated to government-provided vertical housing must stay overnight in their previous residences. (Informant J2)

The community’s determination to remain in their area has led to the development of various adaptation strategies for climate change. In 2021, following the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ministry of Defense proposed the construction of floating and stilt houses (Figure 3). These are equipped with solar panels for energy and water desalination facilities to provide clean water. The provision of clean water is a significant breakthrough, since the residents of Muara Angke currently lack access to a clean water system and must purchase water privately at their own expense. While this could be an excellent adaptation strategy, if not carefully managed, this innovation may become a new pull factor, attracting new inhabitants and visitors to the place.

Figure 3. Floating Houses as Adaptation Measures in Muara Angke

Source: Authors, 2024

Immobility in Tambak Lorok, Semarang

Similar to Muara Angke, Tambak Lorok has been experiencing tidal floods and land subsidence for at least the last three decades (Astuti & Handayani 2020), with an aggravation of the situation since 2014. However, despite the government’s offer of new locations for settlement, the residents of Tambak Lorok have chosen to stay and adapt to these conditions. Their decision to stay is based on their familiarity with their current livelihoods (Figure 4) and their acceptance of floods as a part of life. A roundtable discussion with the community confirmed their willingness to stay, especially since the Semarang City Government, with support from the National Government, has built sea walls and regenerated some public facilities (e.g., local markets and fish auction areas) to improve the quality of the neighbourhood. Women cooperatives started to advertise successfully community gardening. Additionally, insights from the government roundtable indicated that while the construction efforts may provide some protection, they are unlikely to be sufficient for long term development and that side-effects such as the variations of streams during the floodings are not predictable. This suggests that a comprehensive, long-term solution is still needed to mitigate sea level rise and anticipate the ongoing rate of land subsidence.

Figure 4. Fish Processing and Fish Harbors as forms of Livelihood in Tambak Lorok

Source: Authors

One of our informants explained the rationale of most of the inhabitants when it comes to decision making about relocation:

When we talk about relocation, it means that the government will give us a better place than what we had before. Still, even though people in Tambak Lorok experience tidal flooding every day, none of them want to be relocated. The first reason is their livelihood–they work as fishermen, but the government has offered them vertical housing near the river. They hesitate, thinking, ‘I left my boat at the shore. What if the tidal wave hits it while I’m going back to my new house away from the coast?’. This will be hard for us, which is why there is no relocation or migration in Tambak Lorok. The government has not been able to provide us with a better place. Besides, there is no such thing as a serious disaster here–just a high tide that flooded our house. This might be a threat, but I consider it as a friend or a brother. (Informant S1a)

By deciding to stay, the residents of Tambak Lorok remain continuously exposed to climate risks, leading to various intersecting problems, including economic losses due to their inability to work during the floods, housing damage and various diseases. These conditions prompt numerous efforts to survive. The inhabitants are willing to allocate their financial resources to elevate their houses to cope with the consequences of the flooding. There is stern mistrust in the government’s offers to relocate them. While the situation of staying may lead to economic constraints, the development of an industrial zone near Tambak Lorok has created job opportunities to help meet their needs. It is also noteworthy that individuals from Demak and Purwodadi–the neighboring regencies to the east of Semarang–are willing to commute or even to relocate to Tambak Lorok and its surrounding areas to work in local industries. The neighbourhood attracts additional workers:

The women are benefiting from the development of Lamicitra Industrial Center. Previously, women can only wait at home while their husbands were at sea. Nowadays, through the synergy of Lamicitra, women of productive age are given the opportunity to work as industrial workers in the home-based garment sector. Therefore, women in Tambak Lorok can now assist their husbands in earning a living. (Informant S2b)

Residents of Tambak Lorok have developed several initiatives to adapt to their deteriotating environment. An urban farming initiative led by a group of community farmers has provided numerous benefits to the local population (Figure 5). The residents can sell their harvests to generate additional income or overcome stunting and malnutrition among their children. The community has established a waste bank and utilized eco-enzymes to address waste management issues, thereby reducing flood risk. Several community organizations have also been founded to address various sectors, including the Tangguh Bahari disaster task force, the Srikandi Bahari SMEs organizations, and the Terang Bahari group, which focuses on enhancing education for children. Piggott-McKellar and McMichael (2021) stated that enabling in situ adaptations to environmental changes can be a crucial factor for the populations to remain in place. With available resources and options for adaptation, the inhabitants of Tambak Lorok have chosen to stay and harness their capacity to survive, rendering their immobility voluntary. Additionally, the government has constructed stilt houses as a pilot project to promote more advanced adaptation strategies in Tambak Lorok. Organisations such as Women Empowerment Organization and Neighborhood Unit 15 in Tambak Lorok, (the lowest level of administrative unit in Indonesia, where the Head was interviewed) claim that already the perspective to better their own living conditions and feelings of hope help to make the place more resilient and sustainable. As a NGO-activist pointed out ‘When you’re sinking physically, you’re sinking also mentally’ (Hillmann & Handayani 2024).

Figure 5. Community Urban Farming as Adaptation Measures by Residents in Tambak Lorok

Source: Authors 2024.

Immobility in Panjang Wetan, Pekalongan

Similar to the residents in the other two case studies, the affected people who primarily depend on the fishery sector in Panjang Wetan (Figure 6), demonstrate a preference to remain in their communities and adapt to the ongoing environmental changes. Most residents express a strong desire to stay due to their attachment to Panjang Wetan as their birthplace and home. Their reluctance to migrate also stems from concerns about job insecurity elsewhere, the potential loss of business, and uncertainty about what the new neighborhood might bring.

My family does not want to migrate. This is our homeland. We were born here and we will try our best to stay here. (Informant P1)

Figure 6. Fish Market and Harbors as forms of Livelihood in Panjang Wetan

Source: Authors 2024

Some residents can migrate voluntarily, but the lack of movement is not entirely voluntary. Some respondents expressed a desire to move but said that they are unable to do so due to financial constraints. This finding aligns with previous studies indicating that economic factors are the most significant considerations rather than climate hazards. Individuals with limited economic capabilities, despite being equally exposed to climate risks, are more likely to be immobile and stay in place (Parrish et al. 2020; McMichael et al. 2021), confirming the notion of the ‘trapped population’. As the smallest city among the three selected study areas, residents of Panjang Wetan have even less access to opportunities for higher income and better quality of life compared to the two cases depicted above. At times, due to economic difficulties, Panjang Wetan residents have to take out loans from the bank to elevate their houses to prevent flooding. Thus, the findings in Panjang Wetan can be identified as involuntary immobility.

The roundtable discussions revealed that the government has considered both residents’ aspirations to migrate and their desire to stay. Relocation policies align with the Central Java provincial program named Tuku Tanah Oleh Omah (Buy House, Get Land)–an initiative aimed at supporting land purchases and housing construction. Simultaneously, as an in situ adaptation strategy, the government constructed a sea wall in 2017 as flood management infrastructure in Panjang Wetan. This intervention has helped prevent floods from disrupting their livelihoods.

In Pekalongan, residents have also experienced industrialization, with women now being able to work in the clothing convection factories to increase their earnings. Pekalongan is a center for the global batik industry, employment opportunities in the convection sector, particularly for batik, can help women from Panjang Wetan gain exposure to new prospects. These opportunities can provide them with more options and lead to an improved quality of life through infrastructure improvement and new opportunity of employment (Figure 7), allowing them to make voluntary decisions about whether to stay or migrate without economic barriers. The work in the batik industry is unhealthy for the workers and means pollution of the environment, too.

Figure 7. Sea Wall and Employment in the Home-based Garment Sewing Industry as Adaptation Measures in Panjang Wetan

Source: Authors 2024

Comparisons and Discussion

All three cases experience immobility despite environmental pressures present in their current locations. However, there are some differences in the underlying reasons for their choice to remain immobile within each community. Table 1 presents a comparative analysis focusing on the distinct physical and social characteristics of all three fishing settlements, along with different findings regarding immobility patterns.

The comparison table also identifies the characteristics of each place and its immobility patterns. In all three cases, we find indicators for the role of political governance. Larger cities provide robust economic environments and better service infrastructure, attracting people (Xing & Zhang 2017). As the residents of the capital city of Indonesia, people in Muara Angke have access to job opportunities with higher and more stable incomes, along with comprehensive services to support their livelihoods, provided by both national and local governments. They also tend to employ more advanced adaptation strategies, such as floating houses.

A similar situation applies in Tambak Lorok in Semarang. Residents have developed adaptive capacities through communal actions, supported by the availability of resources. A previous study by Astuti and Handayani (2020) found that people in Tambak Lorok can access infrastructure services due to their close proximity to urban amenities and diverse job opportunities. This is exemplified by the development of the Lamicitra Industrial Center, which offers employment opportunities for residents as laborers. In contrast, smaller cities like Pekalongan face challenges in providing the same level of economic opportunities and facilities, which can lead to residents feeling ‘trapped’ and de facto being trapped, unable to seek better living conditions. Although the government has made efforts to accommodate the community’s desire to move, people continue to pursue in situ adaptation options related to flood mitigation infrastructure and industrial job opportunities for higher income. This study implies that a city’s adaptive capacity plays a crucial role in shaping immobility patterns. Direct and indirectly, adaptive capacity can lead to more equitable opportunities for residents to choose between staying or moving, thereby promoting mobility justice.

Being situated in a large city with higher capacities to leverage economic activities and public facilities enhances people’s capacity for adaptation. Dewi et al. (2023) argue that dense and rapid population growth contributes to the expansion of public facilities, thereby increasing the adaptive capacity of certain urban areas. However, careful policy and regulations are required to ensure that this will not increase the number of vulnerable people because of the attractiveness of these areas for newcomers. This relationship is evident in our findings, particularly in Jakarta and Semarang, where residents employ more advanced adaptation strategies. To some extent, this dynamic suggests that adaptive capacity can be a driver factor for immobility, as individuals have more opportunities to transform their livelihoods without needing to relocate.

In all three cases, political governance has a certain level of impact on the mobility behavior of inhabitants. The level of trust in political processes emerged as a key factor, proving to be as significant as the availability of resources. Moreover, the variety of housing options provided for relocation played a vital role in guiding the decision-making of the inhabitants. Vertical housing solutions were perceived as leading to a deterioration of the social web. In the case of Tambak Lorok, interventions by NGOs brought change, but the sustainability of such changes might be questioned. Long-term solutions must be decided at the political level, but the local stakeholders must be part of the planning process, including the inhabitants.

Conclusion

This paper offers valuable empirical evidence on the phenomenon of immobility as observed in our three study areas along the northern coast of Java, Indonesia. The governments at the three selected research areas have attempted to respond to the emerging disturbances because of environmental changes such as sea wall construction to anticipate tidal flood and relocating vulnerable populations living in these high-risk areas. Indeed, responses to relocation vary significantly from one area to another; some individuals have relocated multiple times, while others refuse to move. Currently, there are no policies in place to support residents forced to relocate—such as providing assistance with relocation or creating alternative livelihood opportunities—nor an integrated development plan to address slow-onset disasters, such as tidal floods and land subsidence. Also missing is a prioritized response plan for the highest risk and damaged areas impacted by sea-level rise and land subsidence in coastal areas. A lack of trust in policy action and state institutions further influenced the immobility pattern. Clearly, the gap in policy needs to be addressed to minimize the impacts of climate change.

The study findings contribute two significant insights. First, it is important to understand immobility as a viable option for in situ adaptation. This includes enhancing adaptive capacity at various scales and providing more opportunities to strengthen local livelihoods. This perspective aligns closely with the concept of mobility justice, which empowers people to choose whether to stay or move. Second, the significant role of policy and political governance must be emphasized. Ultimately, what matters is the commitment of decision-makers to prioritize between managing flood-prone areas and investing in the capacity-building of at-risk populations.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank three anonymous reviewers for their constructive and insightful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

References

Aditiya, A. & Ito, T. 2023, ‘Present-day land subsidence over Semarang revealed by time series InSAR new small baseline subset technique’, International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, vol. 125, article 103579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2023.103579

Amin, C., Sukamdi, S. & Rijanta, R. 2021, ‘Exploring migration hold factors in climate change hazard-prone area using grounded theory study: evidence from coastal Semarang, Indonesia’, Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 8, article 4335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084335

Andari, L., Sugianto, D.N., Wirasatriya, A. & Ginanjar, S. 2023, ‘Identification of sea level rise and land subsidence based on sentinel 1 data in the coastal city of Pekalongan, Central Java, Indonesia’, Jurnal Kelautan Tropis, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 329–39. https://doi.org/10.14710/jkt.v26i2.18324

Astuti, M.F.K. & Handayani, W. 2020, ‘Livelihood vulnerability in Tambak Lorok, Semarang: an assessment of mixed rural-urban neighborhood’, Review of Regional Research, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 137–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10037-020-00142-7

Ayeb-Karlsson, S. 2020, ‘When the disaster strikes: Gendered (im) mobility in Bangladesh’, Climate Risk Management, vol. 29, article 100237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2020.100237

Bennett, W.G., Karunarathna, H., Xuan, Y., Kusuma, M.S.B., Farid, M., Kuntoro, A.A., Rahayu, H.P., Kombaitan, B., Septiadi, D., Kesuma, T.N.A., Haigh, R.& Amaratunga, D. 2023, ‘Modelling compound flooding: a case study from Jakarta, Indonesia’, Natural Hazards, vol. 118, no. 1, pp. 277–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-023-06001-1

Bergmann, J. & Martin, S.F. 2023, ‘Addressing Climate Change-Related Human Immobilities’, KNOMAD Working Paper, KNOMAD Trust Fund, World Bank Group, Washington, D.C. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099658308192441551/IDU1d887603a1af6e14dbd1913c1857ae096715c

Blondin, S. 2021, ‘Staying despite disaster risks: Place attachment, voluntary immobility and adaptation in Tajikistan’s Pamir Mountains’, Geoforum, vol. 126, pp. 290–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.08.009

Boas, I., Wiegel, H., Farbotko, C., Warner, J. & Sheller, M. 2022, ‘Climate mobilities: Migration, im/mobilities and mobility regimes in a changing climate’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol. 48, no. 14, pp. 3365–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2066264

Bott, L.M., Schöne, T., Illigner, J., Haghighi, M.H., Gisevius, K. & Braun, B. 2021, ‘Land subsidence in Jakarta and Semarang Bay-The relationship between physical processes, risk perception, and household adaptation’, Ocean & Coastal Management, vol. 211, article 105775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105775

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2013, Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Buchori, I., Sugiri, A., Mussadun, M., Wadley, D., Liu, Y., Pramitasari, A. & Pamungkas, I.T.D. 2018, ‘A predictive model to assess spatial planning in addressing hydro-meteorological hazards: A case study of Semarang City, Indonesia’, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 27, pp. 415–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.11.003

Carling, J. 2002, ‘Migration in the age of involuntary immobility: Theoretical reflections and Cape Verdean experiences’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 5–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830120103912

Central Bureau of Statistics, Indonesia (CBS)2021, ‘Results of the 2020 population census’, Statistics Indonesia. https://www.bps.go.id/id/pressrelease/2021/01/21/1854/hasil-sensus-penduduk--sp2020--pada-september-2020-mencatat-jumlah-penduduk-sebesar-270-20-juta-jiwa-.html

CBS 2022, ‘North Jakarta in Numbers 2021’, North Jakarta Central Bureau of Statistics. https://jakutkota.bps.go.id/id/publication/2021/02/26/79e6241adc6c6a011bc76215/kota-jakarta-utara-dalam-angka-2021.html

CBS. 2023, ‘Semarang City in Numbers 2022’, Semarang City Central Bureau of Statistics. https://semarangkota.bps.go.id/id/publication/2022/02/25/b4fc35189dd9d76b896dcbf3/kota-semarang-dalam-angka-2022.html

Cundill, G., Singh, C., Adger, W.N., De Campos, R.S., Vincent, K., Tebboth, M. & Maharjan, A. 2021, ‘Toward a climate mobilities research agenda: Intersectionality, immobility, and policy responses’, Global Environmental Change, vol. 69, article 102315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102315

de Haas, H. 2021, ‘A theory of migration: the aspirations-capabilities framework,’ Comparative Migration Studies, vol. 9, article 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4

Dewi, R.S., Handayani, W., Pratama, I.P., De Vries, W.T., Rudiarto, I. & Artiningsih, A. 2023, ‘Assessing Flood Vulnerability from Rapid Urban Growth: A Case of Central Java — Indonesia’, Chinese Journal of Urban and Environmental Studies, vol. 11, no. 4, article 2350020. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2345748123500203

Foresight Report. 2011, Migration and Environmental Change, Final project report, The Government Office for Science, London. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/migration-and-global-environmental-change-future-challenges-and-opportunities

Handayani, W., Chigbu, U.E., Rudiarto, I. & Putri, I.H.S. 2020, ‘Urbanization and Increasing flood risk in the Northern Coast of Central Java—Indonesia: An assessment towards better land use policy and flood management’, Land, vol. 9, no. 10, article 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9100343

Harintaka, H., Suhadha, A.G., Syetiawan, A., Ardha, M. & Rarasati, A. 2024, ‘Current land subsidence in Jakarta: a multi-track SBAS InSAR analysis during 2017–2022 using C-band SAR data’, Geocarto International, vol. 39, no. 1, article 2364726. https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2024.2364726

Hillmann, F. 2010, ‘On new geographies of migration and old divisions of labour’, in New Geographies of Migration in Europe, Special Issue, Die Erde, no. 141, pp. 1–17.

Hillmann, F. & Handayani. W. 2024, ‘Leben mit der Flut‘, Das Journal der Einstein-Stiftung, no. 9, pp. 84–87.

Hillmann, F., Pahl, M., Rafflenbeul, B. & Sterly, H. 2015, ‘Introduction: (Re-)locating the nexus of migration, environmental change and adaptation’, in Hillmann, F., Pahl, M., Rafflenbeul, B. & Sterly, H. (eds), Environmental Change, Adaptation and Migration: Bringing in the Region, Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137538918_1

Hoffmann, R., Dimitrova, A.K., Muttarak, R., Cuaresma, J.C. & Peisker, J. 2020, ‘A meta-analysis of country-level studies on environmental change and migration’, vol. 10, no. 10, pp. 904–912. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0898-6

Hugo, G. 2005, Migrants in society: diversity and cohesion, Global Commission on International Migration. https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl2616/files/2018-07/TP6.pdf

Intergovernmental Panel on climate change (IPCC) 2022, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerabilities. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844

Kaczan, D.J. & Orgill-Meyer, J. 2020, ‘The impact of climate change on migration: a synthesis of recent empirical insights’, Climatic Change, vol. 158, no. 3, pp. 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02560-0

Karlina, T. & Johan, W. 2020, ‘Sea level rise in Indonesia: The drivers and the combined impacts from land subsidence’, ASEAN Journal on Science and Technology for Development, vol. 37, no. 3, article 3. https://doi.org/10.29037/ajstd.627

Lee, S.E. 1966, ‘A theory of migration’, Demography, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 47-57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2060063 https://doi.org/10.2307/2060063

McMichael, C., Farbotko, C., Piggott-McKellar, A., Powell, T. & Kitara, M. 2021, ‘Rising seas, immobilities, and translocality in small island states: Case studies from Fiji and Tuvalu’, Population and Environment, vol. 43, pp. 82–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-021-00378-6

Ober, K. 2019, ‘The links between climate change, disasters, migration, and social resilience in Asia: A literature review’, Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series, no. 586. https://doi.org/10.22617/WPS190231-2

Parrish, R., Colbourn, T., Lauriola, P., Leonardi, G., Hajat, S. & Zeka, A. 2020, ‘A critical analysis of the drivers of human migration patterns in the presence of climate change: a new conceptual model’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 17, no. 17, article 6036. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176036

Pennel, C.L., Carpender, S.K. & Quiram, B.J. 2008, ‘Rural health roundtables: a strategy for collaborative engagement in and between rural communities.’, Rural and Remote Health, vol. 8, no. 4, article 1054. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH1054

Piggott-McKellar, A.E. & McMichael, C. 2021, ‘The immobility-relocation continuum: Diverse responses to coastal change in a small island state’, Environmental Science & Policy, vol. 125, pp. 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.08.019

Piper, N. & Datta, K. 2024, Migration and the Sustainable Development Goals: Elgar Companion to the Sustainable Development Goals, Edward Elgar Publishers, Cheltenham. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781802204513

Putri, K., Hargianintya, A., Hasibuan, H.S. & Sundara, D.M. 2021, ‘Housing profile: Analysing human settlement in fisheries village coastal area, North Jakarta’, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, vol. 716, article 12132. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/716/1/012132

Rigaud, K. K., de Sherbinin, A., Jones, B., Bergmann, J., Clement, V., Ober, K., Schewe, J., Adamo, S., McCusker, B., Heuser, S. & Midgley, A. 2018, Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration, The World Bank Group. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/29461/WBG_ClimateChange_Final.pdf https://doi.org/10.1596/29461

Sejati, A.W., Buchori, I., Lakshita, N.M., Wiratmaja, I.G.A. & Ulfiana, D. 2024, ‘The spatial analysis of urbanization dynamic impacts in a 50-year flood frequency in Java, Indonesia’, Natural Hazards, vol. 120, no. 3, pp. 2639–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-023-06298-y

Sheller, M. 2018, Mobility Justice: The Politics of Movement in an Age of Extremes, Verso, London.

Sheller, M. 2021, Advanced Introduction to Mobilities, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham.

Transiskus, S.F. & Bazarbash, M.G. 2024, ‘Beyond the binary of trapped populations and voluntary immobility: A people-centered perspective on environmental change and human immobility at Lake Urmia, Iran’, Global Environmental Change, vol. 84, article 102803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2024.102803

Utami, C.W., Giyarsih, S.R., Marfai, M.A. & Fariz, T.R. 2021, ‘Kerawanan Banjir Rob dan Peran Gender Dalam Adaptasi di Kecamatan Pekalongan Utara’, Jurnal Planologi, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 94–113. https://doi.org/10.30659/jpsa.v18i1.13588

Xing, C. & Zhang, J. 2017, ‘The preference for larger cities in China: Evidence from rural-urban migrants’, China Economic Review, vol. 43, pp. 72–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.01.005

Zickgraf, C. 2019, ‘Keeping people in place: political factors of (im) mobility and climate change’, Social Sciences, vol. 8, no. 8, article 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8080228