Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 16, No. 3

2024

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

Designing a Training Program for the Civil Justice Network: Lower Northern Thailand

Kammales Photikanit

Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand

Corresponding author: Naresuan University 99 Moo 9, Thapo Sub-district, Muang District, Phitsanulok, Thailand 65000, kammalesp@nu.ac.th

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v16.i3.9223

Article History: Received 04/07/2024; Revised 30/10/2024; Accepted 08/11/2024; Published 19/12/2024

Citation: Photikanit, K. 2024. Designing a Training Program for the Civil Justice Network: Lower Northern Thailand. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16:3, 49–66. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v16.i3.9223

Abstract

Since 2022, the Thai government has been establishing community justice centers nationwide. The Civil Justice Network (CJN) has played a crucial role in facilitating justice in every sub-district throughout the country. However, practical challenges have revealed limitations in the knowledge and skills of CJNs. This article aimed to develop training program guidelines for CJNs in Thailand’s Lower Northern Region. The research applied the Action Research (AR) model through a participatory appraisal approach to assess CJNs’ actual needs across five provinces. Initially, 400 CJNs were selected via simple random sampling, with 200 chosen for subsequent training. The resulting program, shaped by research, experimentation, and evaluation, recommends national implementations for all CJNs. Specifically, integrating knowledge and skills related to the principles of Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution through Peaceful Means will further enhance the effectiveness of the CJN’s work.

Keywords

Collaborative Training Program; The Civil Justice Network; Restorative Justice; Human Rights; Conflict Resolution

Introduction

In the current global justice delivery paradigm, restorative justice and alternative dispute resolution (ADR) play a central role. The primary goal is to enhance access to justice at the community level by strengthening individuals’ capacity for peaceful dispute resolution and ensuring equitable justice (Johnstone & Van Ness 2007, p. 5; Kittayarak 2007). Practitioners within the restorative justice framework focus not only on holding the guilty accountable but also on fostering positive relationships between parties, prioritizing connection and understanding over incarceration. The community actively mediates reconciliation, restitution, and forgiveness. This leads to ‘community justice,’ which emphasizes direct community engagement. By promoting social partnerships, community members take an active role in alternative legal systems. By harnessing community resources, they can establish safety and immunity from crime, facilitating justice and peace through practices such as reconciliation, mediation, and sentencing circles (Zehr 1990, pp. 10-12). Ultimately, these practices build a more harmonious and peaceful society.

Thailand has consistently embraced the principles of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) and restorative justice, particularly regarding the policies put into place by the Ministry of Justice under the strategy of the ‘Justice for All, All for Justice’ (Thailand, Department of Probation 2016). The strategy consists of policies and plans designed to promote peace and social justice fully, fairly, and equally such as launching the 2019 Dispute Mediation Act and establishing community justice centers around the nation using justice delivery systems. In 2022, there were 7,783 community justice centers across the nation, with 116,748 Civil Justice Network (CJN) members playing a key role in delivering justice at these centers (Thailand, Permanent Secretary of Justice Ministry 2017).

Although the Thai government works to implement policies for justice through the CJN as a key to promoting community justice, the training programs designed to enhance their capabilities still require adaptation to address the diverse challenges faced by the CJN in various regions. Several studies highlight three major issues: First, structural problems. The top-down approach to establishing community justice centers has led to inadequate preparation, unclear administration, and budget issues. Second, personnel development. Ongoing challenges exist in training key personnel, particularly CJN members, who need additional skills in peaceful methods to support the policies. Third, training curriculum development. The Ministry of Justice provides the training curriculum, but it does not adequately reflect the specific issues and contexts of each area, resulting in a ‘one size fits all’ problem (Conprasert 2015; Lukthong 2017; Unjan 2017; Khantahirun 2022). Additionally, integrating human rights principles into ADR and restorative justice offers a more holistic approach to conflict resolution, emphasizing healing and reconciliation. This approach prioritizes respect for dignity, rights, freedom, and equality, guiding CJNs in dialogue, mediation, and restorative processes. By fostering mutual respect and understanding, CJNs address the root causes of conflict and promote sustainable solutions (Sonnenberg & Cavallaro 2012, pp. 266-267; Chalermyot 2023).

In light of the issues raised above, this research project sought to design a training program to enhance the capabilities of the CJN. The design process focused on analyzing existing problems, identifying knowledge gaps, and developing skills related to the principles of Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution through Peaceful Means. Additionally, the researchers implemented a trial version of the training program to assess CJN members’ satisfaction. This trial aimed to refine the program for future improvements. The researchers anticipated that the training program would enhance trainees’ knowledge, understanding, and skills related to the functions of the CJN, grounded in human rights principles.

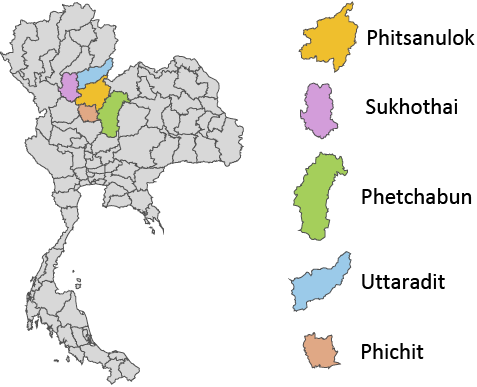

Figure 1. Map of the lower northern region of Thailand

(Source: Author)

Research Objectives

The research objectives of the project are as follows:

1. To investigate the levels of knowledge and skills required for the CJN’s work related to the principles of Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution.

2. To design and trial a collaborative training program aimed at enhancing the CJN’s capabilities based on the principles of Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution.

Literature Review

The restorative justice paradigm views crime as a dispute between the parties involved—the offenders and the victims—and requires both to acknowledge and accept responsibility for their actions. Forgiveness, compensation, and reconciliation play essential roles in repairing relationships and addressing emotions. This paradigm introduces the concept of a ‘community of justice,’ which emphasizes the active engagement and cooperation of various stakeholders within a community to uphold fairness, equity, and accountability in delivering justice. In this approach, individuals, organizations, and institutions work together to address conflicts, promote restorative practices, and protect the rights and well-being of all community members. The community of justice framework encourages inclusive decision-making, empowers marginalized groups, and creates supportive environments where justice remains accessible to everyone, with the CJN taking the lead in mediating community-level disputes (Zehr 1990, pp. 10-12; Androff 2012, p. 79).

The restorative justice paradigm shows that restorative justice and community justice practices align with the principles of human rights. As Gavrielides (2007) highlights, the focus on restoring relationships and repairing harm in restorative justice processes connects directly with the core tenets of human rights, fostering reconciliation and empowering affected parties. By prioritizing dialogue, empathy, and community involvement in addressing harm and resolving conflicts, these practices actively uphold fundamental human rights principles, particularly those related to dignity, fairness, and inclusivity (Gavrielides 2007).

In Thailand, the government places significant emphasis on providing justice to all individuals equally, in line with the principles of human rights. Thailand demonstrated this commitment by being one of the first 48 countries to endorse the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. The country has also ratified seven core international human rights treaties, further solidifying its recognition in the field of human rights1. These actions reflect Thailand’s intention to uphold international human rights norms, addressing civil and political rights, economic, social, and cultural rights, as well as specific protections for women, children, racial minorities, individuals with disabilities, and victims of torture or cruel treatment. Thailand’s ongoing commitment to these treaties highlights its dedication to promoting and protecting human rights both domestically and globally (Thailand, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2015).

The discussion of human rights studies began to gain traction in Thailand after 1997, with the inclusion of children’s rights in the basic education curriculum. Although human rights became part of the secondary education curriculum, the focus remained largely on rote memorization and lectures. This approach may not adequately address the practical learning needs of the Civil Justice Networks (CJNs) who must apply these principles in real-life situations (Amnesty International Thailand 2022). Therefore, the CJNs need additional knowledge and skills to effectively implement human rights principles in their work. As outlined in the Thai government’s policy on promoting justice and protecting human rights universally and fairly, the CJN plays a central role in facilitating justice through Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). In this role, the CJN serves as a mediator, resolving disputes through peaceful methods grounded in respect for human dignity, in alignment with human rights principles (Thailand, Ministry of Justice 2022, p. 2).

Research indicates that the CJN faces significant challenges and requires both knowledge development and skill enhancement to perform their duties effectively through ADR processes in line with human rights principles. These studies emphasize that the CJN needs not only knowledge and skills related to restorative justice and conflict resolution through peaceful means but also a deep understanding of human rights principles. The CJN’s role as a mediator in conflict resolution is closely linked to the protection and promotion of human rights, as mediation processes aim to uphold fairness, equity, and dignity for all parties involved (Soranasiri 2021, p. 67; Thanabodeethada & Wongudommongkol 2020, p. 108; Srisan & Polpanthin 2017, pp. 1967-1968).

Understanding conflict resolution through human rights principles is an important aspect of developing knowledge and skills for mediating disputes peacefully. Considerable research indicates the importance of utilizing human rights studies to attain peaceful conflict resolution. For example, the work of Raymond (2006) presents key knowledge and skills for ADR practitioners in the context of human rights and anti-discrimination law. It emphasizes the importance of specialized knowledge and skills related to human rights principles, which are crucial for individuals acting as conciliators. Furthermore, the author suggests that relevant government organizations are particularly necessary to provide specialized training for officers tasked with resolving conflicts, enabling them to develop the essential knowledge and skills for conducting appropriate mediation in diverse contexts, based on the principles of human rights (Raymond 2006). The aforementioned research, supported by Polavarapu (2023), emphasizes the importance of promoting justice through culturally sensitive human rights principles within communities, aligning with the cultural rights aspect of human rights. It emphasizes community participation and ownership of these rights by and for the community itself. Moreover, personnel involved in fostering justice within communities must possess internationally recognized knowledge and skills in areas such as ADR, community justice, and human rights principles (Polavarapu 2023).

Integrating restorative justice and human rights into training for the Criminal Justice Network (CJN) can enhance conflict resolution and community engagement (Braithwaite 2002). Research emphasizes the need for context-specific approaches. While the study focuses on Thailand’s lower northern region, comparing it with international practices could enrich its applicability. In Nepal, Saul, Kinley, and Sangroula (2010) highlight the necessity of human rights education tailored to local contexts. Their study indicates that law enforcement officials equipped with contextual knowledge are better able to prevent and address human rights violations. This tailored training enhances their conflict resolution abilities, showing that understanding human rights principles is crucial for maintaining public trust and fostering social cohesion. Similarly, Mubangizi (2015) points out the South African government’s limited role in Human Rights Education (HRE), despite its responsibility to integrate human rights into school curricula. While initiatives exist, such as the Curriculum Review Committee’s recommendations, public awareness remains low. Many South Africans lack knowledge of the Bill of Rights, underscoring the need for more effective training and outreach to improve understanding among marginalized communities. In Canada, integrating Indigenous perspectives into conflict resolution training has proven beneficial. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2015) emphasizes the importance of culturally relevant training for law enforcement and judicial officials. By incorporating Indigenous knowledge and practices, Canadian authorities can address historical grievances and promote reconciliation, which leads to more effective conflict resolution in Indigenous communities. These examples highlight the critical role that tailored human rights training plays in creating effective and equitable conflict resolution systems. This training enhances law enforcement skills while also building trust within communities.

Despite the Thai government’s commitment to human rights, current training programs must address the specific challenges faced by the CJN in various regions. Practical training is crucial, as a significant skills gap exists for effective mediation. This article argues that integrating restorative justice principles and human rights education into training programs will enhance the capabilities of Thailand’s CJN in mediating conflicts. This research project seeks to close the gaps in the CJN’s capabilities by investigating the necessary knowledge and skills related to restorative justice, human rights, and conflict resolution. Based on these findings, the project will design and implement a collaborative training program tailored to improve the CJN’s effectiveness in mediation. Ultimately, this approach aims to empower CJN members and strengthen their ability to uphold justice within their communities.

Research Methodology

This study used the Action Research (AR) model, divided into two phases:

Phase 1

Investigate the knowledge and skills needed for CJN work related to Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution

Population and sample

The population of this study consisted of 7,435 members of the CJN in the lower northern region of Thailand. The researcher followed the table of Krejcie and Morgan (1970) to ensure representations of the selected sample, with an acceptable error level of 5% and a confidence level of 95%. Thus, the sample size from the population of 7,435 in this study was 400, selected via simple random sampling.

Data Collection

1. The researcher used a paper-based questionnaire for data collection. Research assistants distributed and collected a total of 400 completed questionnaires.

2. A questionnaire was constructed based on the literature review regarding the five areas of knowledge and skills that the CJN needs for performing their duties, including: (1) Knowledge of related laws, policies, and regulations, (2) Skills in work integration, (3) Knowledge and skills in negotiation and mediation, (4) Skills in consulting and providing assistance, and (5) Knowledge of restorative justice and community justice.

3. The questionnaires were divided into three parts: Part 1: Demographic information of questionnaire respondents, which consisted of a closed-ended questionnaire (Checklist). For example, gender, age, education level, occupation, average income, and experience working as the CJN. Part 2: Information regarding the knowledge and skills related to the principles of restorative justice, human rights, and conflict resolution through peaceful means. This was in the form of a Likert Scale 5-level Rating Scale. Part 3: Other suggestions for developing the potential of the CJN based on the principles of restorative justice, human rights, and conflict resolution through peaceful means. This part was open-ended.

Data Analysis

This research employed descriptive statistics. In Part 1, percentages were utilized. In Part 2, means and standard deviations were calculated, the mean levels were interpreted as follows:

1.00-1.80 - Least serious need

1.81-2.60 - Slightly serious need

2.61-3.40 - Fairly serious need

3.41-4.20 - Very serious need

4.21-5.00 - Most serious need

Part 3 involved frequency analysis, with percentages being used for interpretation.

Phase 2

Designing a training course and organizing training projects

Population and sample

The Provincial Justice Offices in five provinces selected 40 CJNs from the study’s first phase to participate in a training program, totaling 200 trainees.

Data Collection

In developing the training curriculum, the findings of the first phase of the study were synthesized using the method of agreement approach. Subsequently, pre- and post-tests were administered to assess understanding and developmental potential among CJNs in Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution through Peaceful Means, consisting of 15 items. Additionally, a questionnaire was used to evaluate trainees’ satisfaction, divided into three parts: Part 1 is a closed-ended questionnaire (Checklist) gathering demographic information about trainees, including gender, age, education level, average income, and experience as CJNs. Part 2 assesses satisfaction across four main topics: (1) Speaker, (2) Venue/Duration/Food, (3) Knowledge and Understanding, and (4) Application of Knowledge, using a 5-level Likert Scale. Part 3 consists of an open-ended questionnaire gathering suggestions and topics that CJNs would like to see included in future training sessions.

Data Analysis

The researcher applied descriptive statistics to two major types of training programs as follows: 1) Pre- and post-test calculate by means and standard deviations, as well as using the Wilcoxon Signed-rank Test to test hypotheses. 2) For assessing the satisfaction of the trainees, Part 1 utilized percentages. In Part 2, evaluated by means and standard deviations, the mean levels were interpreted as follows:

1.00-1.80: Most dissatisfied

1.81-2.60: Somewhat dissatisfied

2.61-3.40: Neutral

3.41-4.20: Somewhat satisfied

4.21-5.00: Most satisfied

Part 3 involved frequency analysis, with percentages used for interpretation.

Research Results

Phase 1

Investigate the knowledge and skills needed for CJN work related to Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution

Out of 400 respondents, the results revealed that by a small majority most of them were male (201 50.25%) to 199 49.75 female), and aged between 46 and 60 years (52.25%). The age group with the fewest number was those under 30 years old, comprising 23 individuals (5.75%). The majority held a bachelor’s degree, with 269 individuals (67.25%). They were employed as civil servants, government officials, or state employees, totaling 221 individuals (55.25%). Moreover, the majority had over 10 years of work experience as the CJN, with 251 individuals (62.75%) and more than 20,000 baht per month was the average income for 254 (63.50%).

The results from the questionnaire, which has passed the literature review, are based on the five areas of knowledge and skills that The CJN needs for performing their duties. It was found that the need for capacity development in the form of training programs was rated at a very high level (x̄ = 4.19). Overall, the province with the highest need for knowledge and skills development in the CJN’s operational tasks is Phitsanulok (x̄ = 4.21). The area where the CJN requires the most development or enhancement of skills in work is in the field of negotiation and mediation following the principles of restorative justice, human rights, and conflict resolution through peaceful means (x̄ = 4.89). Specifically, the province with the highest need for knowledge and skills development in these areas is Phitsanulok (x̄ = 4.91). Most respondents suggested that there is a significant lack of understanding and knowledge, emphasizing the need to develop knowledge and skills related to negotiation following the principles of restorative justice, community justice, human rights, and conflict resolution through peaceful means.

The study findings presented above align with the data obtained from Part 3 of the questionnaire regarding other suggestions for developing the potential of the CJN, which revealed that out of a total of 400 completed questionnaires, 179 contained suggestions (44.75%). Most respondents from the CJN in the lower northern region suggested the necessity for training/practical exercises on negotiating and mediating community disputes or the acquisition of knowledge in order to register as mediators under the Dispute Mediation Act (2019), as well as relevant laws or policies related to the CJN’s work, (a total of 154 questionnaires, being 86.03% of those with suggestions). These suggestions encompassed both the expressed requirements and the importance of integrating the principles of restorative justice and conflict resolution through peaceful means into the training curriculum. These included, especially, the laws related to criminal proceedings concerning human rights principles in Thailand, such as the Dispute Mediation Act (2019), the Damages for the Injured Person and Compensations and Expenses for the Accused in the Criminal Case Act (2001), the Witness Protection in Criminal Case Act (2003), and the Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearance Act (2022). Following this, there was an identified need for knowledge in community justice and human rights, with 12 questionnaires, accounting for 6.70%, and a need for financial support/compensation for the CJN, with 10 questionnaires, representing 5.59%. The least frequently suggested recommendation was the establishment of a networking system/collaborative efforts among community justice networks in three provinces, with 3 questionnaires, accounting for 1.68%.

The findings highlight the importance of designing training programs for the CJN based on a thorough assessment of their specific needs. A significant majority of respondents indicated a pressing need for capacity development, particularly in negotiation and mediation skills aligned with Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution principles. These training initiatives can empower CJN members to effectively mediate community disputes while upholding human rights, fostering a more just society. Restorative Justice emphasizes repairing harm through mediation, promoting participation from both victims and offenders. By equipping CJN members with these essential skills, the programs enhance their ability to facilitate meaningful discussions and strengthen societal commitments to justice and human rights, ultimately cultivating a resilient community that promotes harmony and respect for all individuals’ rights.

Phase 2

Designing a training course and organizing training projects.

The researcher synthesized Phase 1 data into five courses focused on enhancing CJN conflict resolution skills, covering: Restorative and Community Justice, Human Rights, and Peaceful Conflict Resolution.

1. Laws, Policies, and Regulations: covers knowledge of the laws relevant to the work of the CJN, including: (a) International Human Rights Principles and Law, such as the UDHR and key human rights principles; (b) Human Rights Protection Laws in Thailand.

2. Integration of work processes: covers skills such as collaboration, communication, empathy, and community engagement within the community justice network, with an emphasis on people’s participation.

3. Negotiation and mediation for conflict resolution through peaceful means: covers knowledge and skills related to laws and techniques for mediators, such as the Dispute Mediation Act (2019), conflict analysis and mediation techniques based on principles of respect for human dignity, equality, and non-discrimination.

4. Consultation techniques: including communication skills, consultation methods, empathy, cultural competence, and ethical considerations for effective conflict consultations, adhering to the principles of fairness, equity, and the rule of law.

5. Practical training in negotiation and mediation for conflict resolution: covers knowledge and skills related to negotiation and mediation processes and techniques, nonviolent communication (NVC), conflict analysis, case studies, and conflict management techniques.

Afterward, the researchers proceeded to organize training projects aimed at developing conflict resolution potential based on restorative justice and human rights principles for the CJN, targeting groups in the five provinces of the lower northern region. The Provincial Justice Offices were responsible for selecting trainees for the training, with 40 people from each province. The summary of the training sessions is presented in Table 4. The demographic details of trainees is presented in Table 5.

The results from the 2-day training project conducted in each province revealed that a total of 200 trainees (N=200) attended. The majority were male, comprising 112 (56.00%), while females accounted for 88 (44.00%). Trainees aged between 46 and 60 years totaled 89 (44.50%). Among them, 136 (68.00%) held bachelor’s degrees. The majority were retired civil servants, lawyers, and farmers, totaling 89 (44.50%). Moreover, 141 (70.50%) had more than 10 years of work experience, and 112 (56.00%) reported an average monthly income exceeding 20,000 baht.

After completing the training in each province, the researchers assessed the knowledge and understanding of the trainees using pre- and post-tests consisting of an identical set of 15 questions. The test results showed that overall, across all provinces (N=200), the average scores of knowledges and understanding before and after participating in the training were 6.33 and 13.75 points, respectively, indicating an increase of 7.42 points. Before the training, the lowest score was 4 points, and the highest was 8 points. After the training, the lowest score observed was 12 points and the highest was 15 points. These details are shown in Table 5.

Regarding the hypothesis test on ‘the understanding and development potential among CJNs in Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution through Peaceful Means,’ which posited that ‘after the training, the level of knowledge and understanding on these issues would be higher than before the training,’ the Wilcoxon Signed-rank Test yielded an Exact Sig. (1-tailed) = 0.000, which is less than 0.05. Therefore, the null hypothesis (H0) was rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis (H1), indicating that the training significantly increased trainees’ knowledge and understanding of the subject matter at a statistically significant level of 0.05.

| N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post_test - Pre_test | Negative Ranks | 0a | .00 | .00 | Z | -12.350b |

| Positive Ranks | 200b | 100.50 | 20100.00 | |||

| Ties | 0c | |||||

| Total | 200 | |||||

| Exact Sig. (1-tailed) | .000 | |||||

aPost_test < Pre_test

bPost_test > Pre_test

cPost_test = Pre_test

The significant enhancement in knowledge highlights the importance of the training program’s design, which is based on a thorough analysis of the specific issues and skills required for the CJN. By incorporating concepts of Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution, the curriculum directly addresses the identified knowledge gaps. The program also includes modules on case studies, enabling trainees to engage with real-world scenarios and enhance their understanding through practical application. These case studies provide essential context for the theoretical concepts, making the learning experience more relatable and impactful. Additionally, simulation exercises where trainees act as mediators help them develop critical skills in a controlled environment. These role-playing activities build confidence and reinforce effective mediation techniques.

The assessment of trainee satisfaction revealed that CJNs, in their role as trainees, reported the highest overall satisfaction level (x̄ = 4.67). A closer examination showed that the highest scores came from satisfaction with the instructors (x̄ = 4.73). Trainees largely attributed this high rating to the instructors’ effective communication, their efficient integration of analytical knowledge and conflict management strategies, and their ability to blend restorative justice and community justice principles with human rights education. Uttaradit province reported the highest overall average satisfaction level with the training program (x̄ = 4.73), while Phichit province had the highest average satisfaction level with the guest lecturers ( = 4.80). The details are reported in Table 7.

The training program achieved high satisfaction levels among trainees due to the expertise of its instructors, who included key figures from various government sectors, such as directors of Provincial Justice Offices and specialists from the Ministry of Justice. Academic scholars from universities and the Office of Peace and Governance also contributed, demonstrating a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between human rights principles and restorative justice. Instructors effectively combined theoretical lectures with practical applications, using case studies and simulations to illustrate concepts and engage trainees in conflict resolution scenarios. This design carefully addressed the challenges and knowledge gaps faced by CJN members, ensuring relevance and applicability. By aligning the curriculum with the core principles of Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution, the training enhanced understanding and built confidence among trainees. Ultimately, this thorough approach not only equipped participants with essential skills but also significantly increased their satisfaction with the program, fostering a commitment to addressing real-world conflicts effectively.

Regarding other suggestions for organizing the training program, the envisioned format for the future training program for the CJN., summarizing from a total of 200 questionnaires received, there were 141 responses, accounting for 70.50%. Most respondents suggested continuous and regular training to develop operational capabilities in this area, at least once per year, totaling 83 responses, or 58.87%. Following this, there were suggestions for network training to cover every district/sub-district, totaling 30 responses, or 21.28%. Lastly, there were suggestions for network training to cover all groups, such as community mediation centers or grassroots community groups, totaling 28 responses, or 19.85%.

Subjects or topics that should be incorporated into future training programs for the CJN. can be summarized as follows: Out of a total of 200 questionnaires distributed, there were 188 responses, accounting for 94.00%. Most respondents suggested implementing training courses where trainees who have completed the training can register as mediators under the Mediation Act (2019). Additionally, they recommended practical training, experience exchange on mediation and networking to promote mutual learning, totaling 123 responses, or 65.43%. Furthermore, there were suggestions for training on legal/policy topics related to the Mediation Act (2019), such as basic laws regarding property rights and inheritance, criminal law regarding comprisable offenses and petty offences, and community justice policy based on human rights principle totaling 53 responses, or 28.19%. For example, in the performance of duties as CJNs acting as mediators under the Dispute Mediation Act (2019), it is crucial to have knowledge and understanding of human rights principles, including the fundamental role of human rights, which is to safeguard and promote the inherent dignity and worth of every individual. These principles establish the framework for peaceful coexistence and ensure conflict resolution with equality, justice, and fairness in societies. Additionally, CJNs must regularly update their knowledge of laws and government policies related to the Dispute Mediation Act (2019), including, in criminal law mediation, relevant cases include participation in combat leading to death (Article 294), physical assault (Article 295), malicious assault (Article 296), serious injury (Article 299), causing bodily harm (Article 300), and theft (Article 334) and in civil mediation, disputes involve non-property land issues, inheritance among heirs, and cases involving assets not exceeding five million baht or specified amounts. The topic that the CJN proposed to have the lowest percentage of training programs in the future is training on the principles of mediation, mediation skills, practical mediation techniques, and the exchange of experiences related to mediation among the CJN with 12 responses, or 6.38%.

This feedback highlights the necessity for future training programs to conduct thorough assessments of the specific knowledge and skills required by CJNs. It is crucial to regularly review and update course content to ensure alignment with the principles of Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution. This approach will not only enhance trainees’ effectiveness in managing diverse conflicts but also empower them to foster reconciliation and uphold dignity within their communities. By focusing on relevant topics, such as legal frameworks and mediation techniques, the training can provide CJNs with the tools they need to promote justice and equity.

Discussion and Conclusion

A review of related research reveals challenges in developing knowledge and skills within the CJN, particularly the lack of participatory training curriculum design based on educational studies and an analysis of the CJN’s issues and diverse contextual needs (Conprasert 2015; Lukthong 2017; Unjan 2017; Khantahirun 2022; Chalermyot 2023, p. 62). This research project emphasizes the importance of designing training programs that enhance the capabilities of the CJN, who play a critical role in facilitating community-level justice administration. To design effective training programs for the CJN, researchers must first conduct a thorough study of the challenges and training needs. This includes examining their core responsibilities, the knowledge and skills required, and relevant laws. This analysis provides the foundation for tailoring training programs that align with the CJN’s roles, challenges, and requirements while keeping pace with evolving situations and changes in the law.

In designing the curriculum for the training program, it is essential to build on the foundational knowledge gained from studying the CJN’s core responsibilities, existing challenges, and the knowledge and skills requirements identified in Phase 1 of the study. This knowledge should then be integrated into the various courses within the training program. The content of each course must reflect the core principles of restorative justice, human rights, and conflict resolution through peaceful means, as these principles are crucial for enhancing the CJN’s knowledge, understanding, and skill development. These principles can be categorized into two main types, as follows:

The first aspect, the benefit of increasing knowledge in the principles of restorative justice and human rights, helps the CJN understand fundamental principles from a personal level to globally accepted standards and practices, as reflected in various laws relevant to the CJN in diverse contexts. Thus, integrating human rights principles into training programs not only enhances ethical awareness, diversity respect, and justice commitment but also equips trainees with practical skills and a deeper understanding of human rights’ importance in both professional and personal spheres. This integration adds significant value by making training programs more relevant and responsive to societal needs and challenges. By fostering an ethical framework and sensitivity to navigate complex human interactions, training promotes inclusive practices, empowering communities with socially responsible individuals capable of contributing to sustainable development and equitable outcomes. Additionally, applying human rights principles in training for restorative justice is crucial for cultivating a balanced and peaceful society. Such training enables trainees to apply these principles effectively in conflict resolution, fostering understanding and utilizing trustworthy methods in addressing complex legal situations through real-life case studies and simulations, thus preparing them for practical application in their future work and daily lives.

The second aspect is the benefit of developing knowledge and skills in the CJN’s role as a mediator. The application of human rights principles in training for restorative justice is crucial for promoting a balanced and peaceful society. This training equips trainees with the knowledge and skills to apply human rights principles effectively in conflict resolution and restorative justice practices. It ensures that mediation processes uphold fundamental human rights such as equality, fairness, and dignity for all involved parties. This approach creates an environment where individuals feel respected and heard throughout the resolution process. Moreover, the training facilitates the development of practical skills through real-life legal scenarios and case studies. For instance, CJNs acting as mediators prioritize equality and respect for each individual, fostering reconciliation and redress without resorting to violence. The process encourages all parties to engage in resolving issues and take responsibility for harm caused. By emphasizing inclusive practices and building trust among trainees, the training promotes efficient inquiry and mutual understanding. By aligning with universal human rights standards, mediators ensure that mediation outcomes are perceived as just and equitable by all parties, enhancing trust in the process and increasing the likelihood of successful resolution. Furthermore, integrating human rights-based dispute resolution principles promotes social justice and contributes to building a more inclusive society by addressing underlying power imbalances and systemic inequalities that can marginalize vulnerable groups within communities.

Overall, the integration of human rights principles into mediation practices is not only necessary but also significant in promoting fairness, justice, and social cohesion within communities. It ensures that mediation processes are conducted in a manner that respects the rights and dignity of all individuals involved, ultimately leading to more sustainable and mutually beneficial resolutions.

The Potential Challenges of the Proposed Training Programs

Integrating human rights principles into training programs for the CJN presents significant challenges that can undermine their effectiveness in promoting restorative justice and peaceful conflict resolution. One major concern is curriculum development; current training often relies on rote memorization and needs to be supplemented by practical application (Amnesty International Thailand 2022). Developing a participatory and context-sensitive curriculum tailored to CJN’s needs is essential yet complex. A solid understanding of restorative justice is crucial, as without it, CJN members may struggle to facilitate mediation that upholds fairness and human dignity (Zehr 1990; Gavrielides 2007). Cultural sensitivity is also vital; human rights education must reflect diverse cultural contexts to foster community ownership (Polavarapu 2023). Furthermore, addressing significant knowledge gaps about human rights in Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) is necessary (Raymond 2006). Resistance to new practices complicates integration efforts, making effective communication about the benefits of human rights in mediation essential (Soranasiri 2021). Tailored training focused on local needs, informed by comprehensive assessments of regional human rights issues, is crucial for maintaining relevance. Lastly, resource limitations pose a barrier; adequate funding and support are vital for delivering high-quality training. By prioritizing culturally relevant and context-specific training, the CJN can enhance its capacity to promote restorative justice and protect community rights, ultimately fostering a more just and equitable society.

Figure 1. The model guidelines for collaborative training aim to enhance the CJN’s capacity by integrating concepts of Restorative Justice, Human Rights, and Conflict Resolution.

Recommendations

This study offers recommendations for changes in policy and practices, as well as suggestions for further research.

Firstly, concerning policy recommendations: The Ministry of Justice, a key sponsor responsible for shaping legal frameworks and policies related to dispensing justice, emphasizes fostering harmony and reconciliation through peaceful means and human rights principles. It should consider fostering academic collaboration, which can be achieved by constructing a training project for the CJN. The Provincial Justice Office in each province would act as the representative of the state-provincial level agency responsible for designing and organizing training programs. This collaboration could involve partnerships with higher education institutions and human rights organizations from both government and private sectors at the provincial level.

Secondly, concerning operational recommendations: In designing and organizing training programs for the CJN, it is crucial to study the specific problems and genuine needs that vary across provinces, including new laws that have been amended and reissued in response to changing circumstances. Therefore, incorporating the specific problems and genuine needs of the CJN in each province as a starting point in designing the training program will help both in problem-solving and in enhancing the efficiency of the CJN’s duties. The training program for the CJN should integrate the principles of restorative justice, human rights, and conflict resolution through peaceful means. Besides their importance in legal matters and in adhering to the Ministry of Justice’s policy of promoting fairness and justice in Thailand, which the CJN generally has experience in, the challenging question lies in how the CJN will carry out their duties based on which foundational principles. Thus, these aforementioned principles are considered international principles that not only enhance the understanding and application of justice but also promote fairness, reconciliation, and respect for human dignity. They equip trainees with skills to address conflicts constructively, fostering a society where disputes are resolved in a manner that upholds rights and promotes lasting peace. Moreover, integrating these principles underscores a commitment to ethical practices and strengthens the foundation of a just and equitable legal system.

Lastly, concerning research and academic recommendations, three areas for further research are identified: 1) The research scope should be expanded to encompass civil justice networks in other regions of the country, allowing for the application of study findings in designing relevant training projects. 2) There should be ongoing monitoring and evaluation of conflict resolution utilizing nonviolent techniques and human rights principles within civil justice networks across different regions of the country. 3) In-depth research should be conducted to identify the factors contributing to the success of CJNs (best practices), enabling the extraction of valuable insights and success factors for the expansion of civil justice networks to additional locations in the future.

Acknowledgments

The researcher gratefully acknowledges the support of the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT), the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Naresuan University, Thailand, the Provincial Justice Offices in five provinces in the lower northern region of Thailand (Phitsanulok, Sukhothai, Uttaradit, Phetchabun, and Phichit), the lecturers, and all the CJNs.

References

Amnesty International Thailand 2022, Human rights studies in Thailand. Available at: https://www.amnesty.or.th/latest/blog/1003/ (Accessed 26 January 2024).

Androff, D. K. 2012, ‘Reconciliation in a community-based restorative justice intervention’, Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 73-96. https://doi.org/10.15453/0191-5096.3700

Braithwaite, J. 2002, Restorative Justice and Responsive Regulation, Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195136395.001.0001

Chalermyot, S. 2023, การยุติปัญหาในชุมชนด้วยบทบาทการไกล่เกลี่ยข้อพิพาทภาคประชาชน [Kan Yuti Panha Nai Chumchon Duai Botbat Kan Klai Klia Khor Phiphat Phak Prachachon], Journal of Law and Political Affairs, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 60–71. https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JPG/article/download/266972/178759

Conprasert, N. 2015, ‘Problems of mediation in Community Justice Network A case study on the Mediation Officers at Khok Samrong Community Justice Center of Khok Samrong district, Lopburi Province’. Journal of Integrated Sciences, vol. 12, o. 1. pp. 97-113. https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/citujournal/article/view/246775/167490

Gavrielides, T. 2007, Restorative justice theory & practice: Addressing the discrepancy, HEUNI, Helsinki:

Johnstone G., & Van Ness W. D. 2007, ‘The meaning of restorative justice’, In: Johnstone G., & Van Ness W. D. (eds), Handbook of Restorative Justice, Willan Publishing, Cullompton, UK, chapter 1.

Khantahirun, U. 2022, A Model of the Management of Public-Sector Dispute Mediation Center by Buddhist Peaceful Means: A Case Study of Public-Sector Mediation Center, Sawai Subdistrict, Prangku District, Sisaket Province. (In Thai) Available at: https://e-thesis.mcu.ac.th/thesis/4575

Kittayarak K. 2007, Community Justice: The role of providing justice by the community for the community, Thailand Research Fund, Bangkok.

Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. 1970, ‘Determining sample size for research activities,’ Educational and Psychological Measurement, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

Lukthong, P. 2017, สภาพปัญหาและแนวทางจัดการความขัดแย้งในชุมชนของคณะกรรมการศูนย์ยุติธรรมชุมชน ตำบลหนองหาน อำเภอหนองหาน จังหวัดอุดรธานี (Saphap Panha Lae Naeothang Chatkan Khwamkhatyaeng Nai Chumchon Khong Khanakammakan Sun Yutitham Chumchon, Tambon Nong Han, Amphoe Nong Han, Changwat Udon Thani). Available at: https://buuir.buu.ac.th/xmlui/handle/1234567890/6262

Mubangizi, C. J. 2015, ‘Human rights education in South Africa: Whose responsibility is it anyway?’, African Human Rights Law Journal, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 496-514. https://doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2015/v15n2a13

Polavarapu, A. 2023, ‘Human rights, human duties: Making a rights-based case for community-based restorative justice’, William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice, vol. 30, pp. 53-99. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4545421

Raymond, T. 2006, Alternative Dispute Resolution in the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Law Context: Reflections on Theory, Practice and Skills. Australian Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission. Available at: https://www.asiapacificmediationforum.org/resources/2006/raymond.pdf (Accessed 23 July 2024).

Raymond, T. 2006, ‘Alternative Dispute Resolution in the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Law Context: Reflections on Theory, Practice and Skills’, Proceedings of the 3rd APMF Conference, June 2006, Fiji Islands. www.auddispute.unisa.edu.au/apmf/2006/papers06.htm.

Saul, B., Kinley, D. & Sangroula, Y. 2010, Review of human rights education and training in the criminal justice system in Nepal. Sydney Law School Research Paper No. 10/114. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1701476

Sonnenberg, S. & Cavallaro L. J. 2012, ‘Name, shame, and then build consensus? Bringing conflict resolution skills to human rights’, Washington University Journal of Law and Policy, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 257-308. https://journals.library.wustl.edu/lawpolicy/article/id/1468/ (Accessed 23 July 2024).

Soranasiri, J. 2021, Problems of the Operations of Community Mediation Centers under Dispute Mediation Act, B.E. 2562 Applicable in Bangkok. Available at: https://rsuir-library.rsu.ac.th/bitstream/123456789/1564/1/JITTRA%20SORANASIRI.pdf (Accessed 29 June 2024).

Srisan, J. & Polpanthin, Y. 2017, ‘The development of conflict reconciliation mediation model by community with harmonization’, Veridian E-Journal,Silpakorn University, vol. 10, no. 1. pp. 1959-1975. (In Thai). https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/Veridian-E-Journal/article/view/104720/83347

Thailand, Department of Probation 2016, Duties of Community Justice Network. Available at: https://www.probation.go.th/contentmenu.php?id=231# (Accessed 28 May 2023).

Thailand, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2015, Core international human rights treaties, Available at: https://humanrights.mfa.go.th/th/humanrights/obligation/international-human-rights-mechanism/ (Accessed January 26, 2023).

Thailand, Ministry of Justice 2022, Operation Manual Community Justice Committee. Ministry of Justice, Bangkok.

Thailand, Permanent Secretary of Justice Ministry 2017, Information for listening to opinions on the draft Community Justice Act. Available at: https://www.moj.go.th/files/moj/20170601103536_25822.pdf

Thanabodeethada, R. & Wongudommongkol, A. 2020, ‘Community mediation: Some issues about the Mediation Act B.E. 2562’, Academic Journal for the Humanities and Social Sciences Dhonburi Rajabhat University. vol. 3, no. 3. pp. 95-110. (In Thai). https://so02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/human_dru/article/view/251470/169388

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015, Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Available at: https://irsi.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/inline-files/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf (Accessed 31 October 2024).

Unjan, P. 2017, The community restorative justice process: Proposed recommendations based on critical issues and empirical case study. MA Thesis, Kasetsart University, Thailand. Available at: https://www.lib.ku.ac.th/KUthesis/2560/puwana-unj-all.pdf (Accessed 29 June 2024).

Zehr, H. 1990, Changing Lenses: A New Focus for Crime and Justice. Scottsdale, Pennsylvania: Herald Press.

1 1) the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), 2) the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), 3) the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), 4) the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), 5) the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), 6) the Convention Against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), and 7) the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).