Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 16, No. 2

2024

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

Government Communication and Social Cohesion: A Contradiction of Words in Action?

Vasanthi Naidoo1,*, Purshottama Sivanarain Reddy2

1 University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa, vnresearch202122@gmail.com

2 University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa, reddyp1@ukzn.ac.za

Corresponding author: Vasanthi Naidoo, University of Kwa Zulu-Natal, Westville Campus, University Road, Westville, Durban, South Africa, vnresearch202122@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v16.i2.9182

Article History: Received 08/06/2024; Revised 02/09/2024; Accepted 11/09/2024; Published 19/11/2024

CORRECTION: This paper has been amended to clarify authorship and affiliation. Purshottama Sivanarain Reddy was added as second author having been inadvertently omitted from the earlier version of record.

Citation: Naidoo, V., Reddy, P.S. 2024. Government Communication and Social Cohesion: A Contradiction of Words in Action? Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16:2, 79–98. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v16.i2.9182

Abstract

This article presents the findings of a 2022 doctoral study that examines the government’s communication for social cohesion in the eThekwini Metropolitan Municipal Area, also known as the city of Durban, in South Africa. The findings and recommendations are applicable to social cohesion globally as evidenced by news reports of violence against women in New York, anti-LGBTQIA+ laws in Uganda, anti-Moslem and anti-Christian sentiments. The study employing a Likert-type questionnaire and focus group discussions revealed that government communication, measured against the Social Cohesion Index, surreptitiously changes mindsets but is undermined by its actions. Participants perceive slow service delivery, corruption, unfair implementation of affirmative action, racism, homo- and trans-phobia, marginalization of the disability sector, tribalism and dearth of leaders, as hindrances. The LGBTQIA+ and disability sectors are victimised limiting their inclusion in the economy and access to services. Recommendations include appointing credible leaders as social cohesion ambassadors, fair implementation of affirmative action policies and communication substantiated by tangible public services.

Keywords

Government Communication; Social Cohesion; Trust; Social Relations, South Africa; eThekwini Municipal Area, KwaZulu-Natal

Introduction

The South African democratic government seeks to unify its diverse population, promote the values embodied in its Constitution, focusing on unity, righting the wrongs of the past, respect, tolerance, accountability, and responsiveness through, amongst others, communication. This research attempted to ascertain the impact of government communication on social cohesion and in changing the apartheid-imposed mindsets of people. The study explored the opinions, substantiated by participants’ interpretations and experiences, of South African Government messages in correlation with its practices in terms of service delivery, combatting corruption and delivering on its promises, on various developmental issues such as unemployment, gender equality and catering to the special needs of the disability and LGBTQIA+ sectors. The findings were then measured against the Social Cohesion Index (SCI) of belonging, participation, inclusion, trust and social relationships to ascertain if the South African government’s communication messages promote and ensure social cohesion and inclusion of all its diverse communities. The research looked further at how government’s practices affected participants experiences as measured against the SCI.

Literature Review

Threats to social cohesion is a global concern. News reports of violence against women in New York (Bellafante 2024), anti-LGBTQIA+ laws in Uganda (Human Rights Watch 2024) and anti-Moslem and anti-Christian sentiments (Open Doors International 2023; United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights 2024) are examples of the threat to social cohesion.

In South Africa, incidents of conflict amongst eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality’s demographically diverse communities reflect challenges in government’s attempts to unite its citizenry (Chauke 2011; Gqirana 2016; Duma 2020; Maharaj 2020). Various incidents of racism, tribalism, violence against the LGBTQIA+ and gender based violence and inequalities in the disability sector (Chauke 2011; Gqirana 2016; Duma 2020; Maharaj 2020; Fletcher 2016; de Greef 2019; Nxumalo 2020; Cele 2016; Mswela 2017; Reygan 2019, p. 94; Mphepo 2020; Bangani & Vyas-Doorgapersad 2020, p. 2; Bastart, Rohmer, & Popa-Roch 2021, pp. 2-3) reflect a fragmented society. After 30 years of democracy, South Africans remain fragmented.

The July 2021 riots in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng provinces were further evidence of this fragmented society, as communities were pitted against each other on the grounds of race and ethnicity. The unrest was triggered by the imprisonment of former president Jacob Zuma for contempt of court and a call by the former president’s supporters to protest his imprisonment. During the unrest, malls, shops, garages, tuckshops, taverns, and government facilities were looted, vandalised and, in some instances, burnt. The South African government was slow to respond, either in word or deed and the existing racial and ethnic tensions provided fertile grounds for violence and destruction of life, limb, and property (Expert Panel into the July Civil Unrest 2021, pp. 20-150; Davis 2024). Communities such as Phoenix, Inanda, Zwelisha and Bhambayi, within the eThekwini municipality, were pitted against each other as they fought to access or protect limited resources. People from Phoenix sought to protect their shops, homes, tuckshops from looters which gave rise to criminal acts of racially motivated violence between South Africans of Indian descent and indigenous Africans, mainly Zulu.

While the South African government aims to unite its diverse citizens, there are still many challenges that prevent this from happening, not least of all the government itself. The government does not adequately capitalise on opportunities to galvanise patriotism and social cohesion, for example, national assets such as the Springboks and Siya Kolisism (Laloo 2024, p. 213; Kennedy 2019; McCarry 2023; Wright 2024). The Springboks is the South African National Rugby Team, currently captained by Siya Kolisi. Siya “Kolisism” is a term, inspired by Siya Kolisi, used to refer to the leadership and uniting qualities that South Africans hope other leaders and people in the country will aspire to. The Springbok Rugby team enjoy huge support across South Africa’s diverse population and continue to unite diversity during their games, creating a sense of patriotism and unity behind the team. They do this by demonstrating each time they play, the power of unity in diversity as the team comprises players from all races and socio-economic backgrounds. Such National assets should be used as a springboard to promote social cohesion through sustained communication and active interventions. Furthermore, the literature review highlights the gap in the body of knowledge in respect the power of communication on social cohesion.

Research problem

Government communication under-utilises the opportunity to change mindsets on social cohesion and realise the country’s transformation agenda. Dedicated, unifying government messages, especially around economic emancipation and ownership, can unite citizens across diversity (Melkote & Stevens in Otto & Fourie 2016, p. 23), giving expression to the objectives of the National Development Plan (NDP), namely:

• Broad-based knowledge and support for a shared set of values for all South Africans, including those in the 1996 Constitution, hereafter referred to as the Constitution;

• Inclusive economy and society, manage issues of inequality of opportunities, capacity development and redress historical injustices;

• Increased interaction between people from various social and racial backgrounds; and

• Strong leadership across society, mobilised, participatory and responsible citizenry (Republic of South Africa, National Planning Commission 2011, p. 460; Banerji 2015).

To ascertain the impact of government communication on social cohesion, this research was undertaken with participants from Umlazi, Inanda, Phoenix, Queensburgh, and Wentworth within the eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality. The apartheid’s mindset of racial superiority prevails and invokes myriad emotions including self-hate, resentment and anger across cultures. Despite the integrated spaces at work, schools and social events, ethnic, racial, socio-economic or class and cultural integration is not prevalent to any large extent (Ero 2019). The frustration due to poverty and poor service delivery, compared to displays of opulence by the wealthy, manifests itself in the form of service delivery protests and hate crimes.

Inter-generationally transferred stereotypes and learned prejudices play an important role in how audiences engage with government’s messages. Government messaging should foster community, humanity, respect for, and acceptance of socio-economic and cultural differences. Politicians, as messengers, must be ambassadors for social cohesion to achieve the developmental goals as espoused in the National Development Plan (Republic of South Africa, National Planning Commission 2011, pp. 24-62). This will help combat socio-economic inequality and possible dire consequences such as the civil unrest witnessed in July 2021.

Hypothesis

Strategic government messaging on social cohesion can unite diversity and promote social cohesion as measured against the Social Cohesion Index (SCI) of inclusion, belonging, social relations, participation and legitimacy.

Research questions in relation to the Social Cohesion Index

Research methodology

Research methodology entails the selected research methods and research design that refers to processes that are followed during data collection, analysis and interpretation which consequently informs the recommendations (Auriacombe 2016, p. 3). The research design selected for this study was inductive and deductive. In this study, diversity refers to class, race, ethnicity, disability, gender and sexual orientation. The research aimed to determine the effectiveness of government messaging on participants’ experiences measured against the SCI. The SCI draws from the Afrobarometer, South African Social Attitude Survey, South African Reconciliation Barometer and the National Income Dynamic study. The Afrobarometer is a pan-African network which measures people’s attitudes on social, economic and political issues in Africa. The South African Social Attitude Surveys is an annual survey undertaken by the Human Sciences Research Council that monitors changing issues and can inform policy-making processes in South Africa. The South African Reconciliation Barometer measures public opinion in South Africa’s democracy. The National Income Dynamic study is the first South African panel study that tracks the changes in poverty. The SCI measurements are the five dimensions of social cohesion, namely: inclusion, belonging, social relationship, participation and legitimacy (Burns et al. 2018, p. 3).

The study adopted a mixed research method, using qualitative and quantitative research techniques, defined as historical research (Pandhey & Pandhey 2015, p. 11). The historical research method deals with past events. Welman and Kruger (2003, pp. 178-179) describe historical research as utilising existing factual sources, causally related to the current research topic, as primary data sources that can withstand criticism. ‘The nation which forgets its history is forced to repeat the mistakes’ (Špiláčková in Mohajan 2018, p. 27). Historically, the apartheid regime was characterised by legislated discrimination and human rights violations, creating a lasting impact on people’s perceptions of race, gender, ethnicity, disability, and linguistic affiliation. Legislation such as the Group Areas Act, Immorality Act, and Separate Amenities Act of the apartheid regime is causally related to perceptions of diversity and social cohesion in the democratic dispensation (Mathekga 2015, pp. 255-256). The role of government communication during apartheid was to advance legislated discrimination. The role of government communication in the democratic dispensation is to educate, inform, account, unify and promote social cohesion (Republic of South Africa, Government Communication and Information System 1996, pp. 5-91), informed by the Constitution (Republic of South Africa 1996, pp. 5-20; 92-98; 99). The historical research method ensures richness of data through triangulation with the questionnaire establishing validity and reliability of the data acquired from the focus group discussions (FGDs).

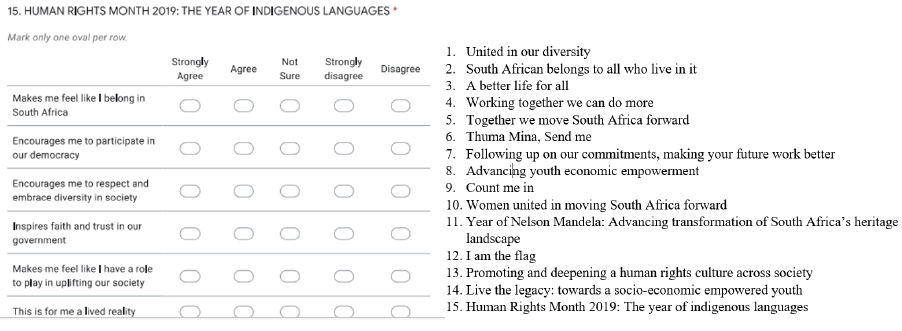

The quantitative part of the study utilises a Likert-type scale questionnaire, a frequently used research tool to measure employee satisfaction, political marketing and communication research (Chyung et al. 2017, p. 15). The questionnaire presented various government themes for participants to rate, according to their experiences against the SCI. The response options in the questionnaire were strongly agree, agree, not sure, strongly disagree and disagree. Government messages that were rated in the questionnaire were as follows:

Figure 1. Sample of the Likert-Type questionnaire and other government messages that were rated.

The qualitative research aspect of this study explored experiences of diversity using focus group discussions (FGD). The FGD drew from participants’ experiences, perceptions and attitudes towards diversity, transformation and government communication in a moderated interaction (Nyumba et al. 2018, p. 21). FGD discussions were guided by the following topics/questions:

• Participants’ knowledge/understanding of the Bill of Rights and social cohesion

• Is government communication and messaging uniting our diverse nation effectively?

• Is government communication adequately addressing transformation?

• What unites us and what divides us and how these factors can be utilised to unite South Africans

• How can government through its messaging unite South Africa towards transformation?

The qualitative approach was utilised for Objectives 1, 3 and 4. The quantitative approach was utilised for objective 2.

The study site comprised various areas within the eThekwini Municipal area, which has a total population of 4 239 901 people (Statistics South Africa 2022). Black Africans constitute 71.6 percent, Indians/Asians 19.7 percent, Whites and Coloureds 6 and 2.5 percent of the population respectively. The participants were sourced from Queensburgh, Wentworth, Phoenix, Inanda and Umlazi in the eThekwini Municipal area. These suburbs were, during apartheid, designated White, Coloured, Indian and Black areas, respectively. They are now demographically integrated, except for Inanda and Umlazi which remain predominantly Black, with some representation of other races for employment purposes. eThekwini Municipality is the only Metropolitan Municipality in the KwaZulu-Natal Province in South Africa and the highest contributor to the province’s gross domestic product. The municipal area is an employment destination for people from other parts of South Africa and neighbouring countries, due to it being a diverse economic hub. eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality is a microcosm of national and global diversity and was thus a suitable study site.

The target population, referring to the collective group of subjects from where the researcher drew the research sample, comprised the diverse demographic, economic and social groups within the eThekwini municipal area (Kumar 2014, pp. 382, 384). The research sample represented Black, Indian, White and Coloured communities from varying socio-economic backgrounds, the disability and LGBTQIA+ communities, government communicators from Government Communication and Information System: KZN Provincial Office and eThekwini Municipality Communications Unit.

The sampling strategy was phenomenologically deliberate (Moser & Korstjens 2018, p. 10) in that it sought to obtain data in respect of the SCI index through the participants’ experiences. Participants were selected on their ability to contribute relevant data (Nyumba et al. 2018, p. 23), that is, their literacy levels, ability to understand the questions or topics discussed and relate, through their experience and knowledge of social cohesion and government messaging, to the SCI index.

Purposive and snowball sampling were utilised for the designated disability, LGBTQIA+ sector and the government communicators sector. The disability and LGBTQIA+ participants were purposively selected through their respective organisations, namely Association for People with Physical Disabilities and TransHope, because they are still marginalised owing to their special needs and non-conformist lifestyles. Government communicators were purposively selected from the Government Communication and Information System in KwaZulu-Natal and eThekwini Municipality, because they are creators of government messages and communication content. Snowballing, enlisting the support and assistance of community leaders or influential persons through existing community-based networks, was utilised for community FGDs (Welman & Kruger 2003, p. 63). Through word of mouth, existing stakeholders mobilised other community members to participate in the research.

The questionnaire was piloted with 21 participants and analysed to verify its functionality in response to the problem statement using Google Sheets. The participants comprised 47 percent males and 52 percent women. In terms of race, the participants comprised 23.8 percent Indians, 23.8 percent Coloureds, 19 percent Whites and 33.4 percent Blacks. The responses from the pilot study confirmed that the questionnaire was fit for purpose.

During the final research, the questionnaire was administered to FGD participants after the discussions. The sample size was determined by the extent to which new or different data was revealed during the FGDs. Once saturation point is reached, the sample size would be considered adequate (Kumar 2014, p. 383).

48 Participants took part in the final research study as follows:

• 22 Africans: six males and 16 females;

• 11 Coloureds: two males and nine females;

• 8 Indians: three males and five females;

• 3 Whites: 3 males and 0 females;

• 2 female participants did not indicate race. One was between the ages of 36-45 and the other 56-65. One was employed while the other had retired;

• 1 Black non-binary gender; and

• 1 Coloured, gender not reflected. This participant did not answer any of the questions on the questionnaire but was part of the focus group discussion.

The above participants included 5 participants from the disability sector and 11 from the LGBTQIA+ segment.

Secondary sources of data collection were electronic and print media, research reports and relevant academic literature. Homogenous groups, which comprised between six and ten participants were projected for the FGDs to ensure in-depth and meaningful discussions (Nyumba et al. 2018, p. 23). The disability FGD comprised only five participants due to low literacy levels.

Data quality was ensured through informed consent, summary of key issues after each FGD, audio recording and transcription of the FGDs. Through triangulation, the questionnaires served to obviate the Hawthorne Effect and validate the findings of the FGDs. The FGDs were audio-recorded with the participants’ consent, for further analysis and transcription.

Analysis was done manually for the final research and through Google Sheets for the pilot. The questionnaire was completed electronically for the pilot study and manually for the final research.

Research Findings

The research revealed the following findings through the comments and perceptions of the participants.

Objective 1: FGD

Belonging

Government communication educates on social cohesion and the importance thereof.

Social cohesion and a united nation were considered important for a prosperous and stable country.

Participation

Participants acknowledged and appreciated government’s public participation initiatives, however felt that these were more for compliance.

Social Relations

The South African Government missed opportunities to strengthen social cohesion, for example, ‘Siya Kolisism.’ Siya Kolisi (Laloo 2024, p. 213; Kennedy 2019; McCarry 2023) in his speech after the 2019 and 2023 Rugby World Cup spoke of unity in diversity over a common goal that led to the Springbok’s victory in the Rugby World Cup. Siya Kolisi and the Springboks are evidence of what can be achieved if diverse people unite towards a shared goal.

Inclusion

Politicians sometimes divide people. Their personal conflicts, prejudices, factions, lack of oversight and poor service delivery spark divisions along race, ethnicity and linguistics (Gqirana 2016; South African Human Rights Commission 2022; Felix 2023) promoting tribalism which is perceived to be worse than racism. Racism was the scapegoat for poor service delivery, poor decisions and non-responsiveness by government and politicians (Expert Panel into the July 2021 Civil Unrest 2021, p. 128; Masson 2022). The LGBTQIA+ community feels that government is not promoting the rights of LGBTQIA+ individuals. They are victimised daily and subjected to ridicule and often fatal sexual violence (Youth Policy Committee Gender Working Group 2019).

Trust

Government communication inadvertently undermines social cohesion. The use of Black Africans in government graphics, images on posters and advertisements inadvertently perpetuates a racial stereotype of Black people being the only perpetrators of crime, for example, illegal electrical connections, hijackings and gender-based violence.

Objective 2: Questionnaire

Belonging

Most government messages invoked positive responses from participants. Almost all participants felt a sense of belonging in South Africa.

Participation

Most participants were positive about this indicator, possibly due to their community involvement in improving their own lives and helping each other.

Social relations

The following messages received positive responses from most of the participants across the diversity: United in our diversity, South Africa belongs to all who live in it; A better life for all; Thuma Mina and Together we move South Africa forward.

Inclusion

Across all demographic groups, disability and LGBTQIA+ sectors, people do not sufficiently feel government’s sense of inclusion. Responses were negative from the White youth who struggle to find employment because of affirmative action policies.

Towards a socio-economic empowered youth received positive responses from all except the White participants but there was a significant percentage drop on this indicator from the Black and Indian participants compared to the other indicators. This highlights high unemployment (Statistics South Africa 2021, pp. 2-3; 2023) and the fight for resources, especially amongst these communities because they live and work in close proximity to each other.

Trust

All the participants rated trust in government poorly. There was a marked reduction in positive percentage responses on the trust indicator compared to others on the questionnaires.

Objective 3: FGD

Belonging

All, except one FGD, indicated that social cohesion and transformation are complementary and must be concurrently addressed.

Participation

The government offers various platforms for community participation, including print and electronic media, social media, public hearings and community structures. However, unpopular opinions and criticism are seen as threats, resulting in marginalisation. Government is perceivably not sufficiently responsive to community needs, discouraging community participation.

Social relationships

Government’s messages surreptitiously changed mindsets from apartheid to democratic South Africa as evidenced by diverse people working together for community upliftment. Messages encouraged community members to build and sustain relationships across racial, gender and ethnic lines. However, government actions and some politicians’ statements negate the messages and social cohesion efforts at the community level. Support for marginalized groups from families, friends, and organizations is welcomed due to government neglect. Stigmatisation of the LGBTQIA+ community and people with disabilities hinders their relations with others.

Inclusion

Political patronage, nepotism, affirmative action, ethnicity, racism, non-acknowledgment from government, differing viewpoints and non-conformance to social and cultural norms and standards were cited as reasons for feeling excluded. Affirmative action excludes other races that are classified as Blacks. Cronyism and cadre deployment in affirmative action appointments were cited as reasons for unemployment and poverty, leading to emigration in search of employment, loss of critical and scarce skills and poor service delivery. The lack of suitable education facilities, resources and employment for the disability sector prevents their inclusion in the economy and society. The LGBTQIA+ participants were discriminated against in the employment sector and society. Their rights to identity, safety and security, freedom of movement, access to health care and police services, human dignity and employment are not adequately safeguarded by government. Hence, they find difficulty in accessing employment and essential services. Language also excludes or limits people’s participation in engagements. For example, Indians, Whites and Coloured may not be able to speak or understand isiZulu, or isiZulu-speaking people may not understand or speak English or Afrikaans.

Trust

FGDs validated this finding and concurred that nothing government says is trusted because it fails to honour its commitments. Corruption, infighting amongst politicians, cadre deployment and nepotism in government and the private sector contribute to the trust deficit. There is a disconnect between government’s messages and actions.

Discussions

Belonging refers to the feeling of having a common purpose, philosophy, a sense of representation, survival and a shared national identity (Healy 2019, p. 3). The positive responses to the questionnaire for this aspect do not indisputably imply that government is actively fostering a sense of belonging, but rather that government is saying the right things. Participants were dissatisfied with government’s attempt at creating a sense of belonging for its people. Politicians’ discriminatory comments, overlooking the needs of certain communities, poor service delivery, corruption, nepotism, and the disconnect between words and actions negate the messages and create a sense of marginalization affecting the sense of belonging. For example, politicians did not visit the non-Black African 2022 flood victims or the families of murdered LGBTQIA+ individuals. The lack of engagement with, and promotion of, LGBTQIA+ and disability rights negatively impacts their sense of belonging. This issue is not the government’s fault alone but involves individuals and communities. Joining organizations like TransHope and Association for the Persons with Disabilities gave these participants a sense of belonging.

Participation refers to the opportunity for citizens to participate and be acknowledged in government’s policy formulation, service delivery plans, programmes and the economy (Lefko-Everett 2016, p. 33). The messages are cognisant of respondents’ concerns and echo their wishes and needs. Participants are also at liberty to participate in any forum, structure, economic or social sector in democratic South Africa. While challenges were raised during focus group discussions, the participants appreciated the opportunity to participate, as opposed to apartheid South Africa, where participation in government programmes, social and economic sectors were largely restricted and, in some instances, prohibited. However, participants felt that these opportunities were a ‘tick-box’ exercise and government was not sufficiently responsive to or serious about addressing their needs.

Social Relations refers to attitudes towards and perceptions of people who appear different or have a different set of traditions, culture, ideology, or capabilities (Lefko-Everett 2016, p. 33). The messages promote inter-racial, inter-cultural relations and resonate with participants. This makes a welcome change from apartheid South Africa where people of different races and cultures were prohibited from associating or socialising with each other. There are no such prohibitions in democratic South Africa. However, much more needs to be done in word and deed by government to address the marginalisation, stigmatisation experienced by the LGBTQIA+ and disability sector and the inequality and poverty experienced by many communities. Government’s contradictory behaviour, politicians’ inflammatory or prejudicial remarks and poor services from public servants undermine the social cohesion gains made at community level. In seeking positive change, participants took the initiative to work together to improve their lives and communities, regardless of race, ethnicity or gender, with or without government assistance.

Inclusion refers to citizens’ access to basic services, employment, participation in and contribution to policy formulation, the reduction of socio-economic inequity and inequalities (Freira et al. 2020, p. 6), acknowledgment of identity and culture, validation and being cared for. In terms of ‘women empowerment’ and ‘making your future work better’, the responses for this indicator were positive suggesting that government’s messages were substantiated by its actions and that the lives of Black, Indian and Coloured women had improved since democracy. White women did not participate in the research.

Within their social structures, for example, the Association for Persons with Disabilities, TransHope, religious and community organisations, participants felt a sense of inclusion attributed to their community-building initiatives, shared ideology, values and ubuntu. The LGBTQIA+ individuals and others who do not subscribe to traditional, dominant or popular beliefs are ostracised and considered disruptive. The low literacy levels in the disability sector focus group reflects the inequality and inequity associated with disability in broader South African and global society.

English-speaking Whites were discriminated against by the Afrikaaner apartheid regime and feel discriminated against by the democratic government. There is acceptance that transformation is crucial; however, across the spectrum of participants, there is dissatisfaction with how it is implemented. Many participants believe affirmative action is ineffective and negatively impacts the middle-class and poor Black, White, Coloured, and Indian people’s ability to care for their families. Affirmative action is perceived to enrich politicians, their friends, relatives and African Blacks, in that order, at the expense of skills, competency and qualification. Cronyism and cadre deployment widens the inequality gap, results in conflict which often manifests in racism, tribalism and sexism (Baloyi 2018, pp. 1, 4-6) and negatively impacts the quality of life. Class distinction, evidenced by the exclusion of poor family members and friends from functions due to their inability to contribute, is increasing.

Trust refers to citizen trust in the state and public institutions attributed to government’s transparency, integrity, fairness, commitment and responsiveness (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2021, p. 2). Government is not leading by example as evidenced by corruption, factionalism and failure to meet its goals, substantiated by the following examples. The commitments made by the President (South Africa, Republic, The Presidency 2011, p. 9) were not honoured as corruption thrived (Zondo 2022, pp. 84-106.). The Medium Term Strategic Framework (MTSF) from 2014 to 2019 (Republic of South Africa, Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation 2014, p. 6) focussed on eradicating inequality, poverty and unemployment. MTSF 2019-2024 aimed to create two million jobs by 2024 (Republic of South Africa, Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation 2019, p. 48). The New Growth Path projected 5 000 000 new jobs from 2010-2020, but by 2019 only 2.5 million jobs were created (Republic of South Africa, Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation 2014, p. 6; 2019, p. 13). The Quarterly Labour Force and Quarterly Employment Statistics for the third quarter of 2021 (Statistics South Africa 2021, p. 2-3) indicated that the number of employed people decreased by 660,000, number of unemployed decreased by 183,000 in comparison to the second quarter of 2021. The number of ‘discouraged work-seekers’ (Statistics South Africa 2021, p. 2) increased by 443,000. The overall unemployment rate recorded in the third quarter of 2021 increased from 35.4 percent in the second quarter of 2021 to 35.9 percent, the highest since the first Quarterly Labour Force Statistics Report in democratic South Africa in 2008. The unemployment rate in the third quarter of 2023 was recorded at 31.9 percent, a slight improvement since the second quarter of 2021. Although youth unemployment decreased, it was still high at 43.4 percent (Statistics South Africa 2023).

A shortage of credible leaders in South Africa, echoed by Anheier and Knudsen (2023, p. 1) as a global challenge, contributes to the trust deficit and loss of confidence in government. Politicians are perceived as lacking a sense of accountability, being self-serving, focusing on garnering votes to stay in power (van Holdt, Swop, & Stifftung 2019, p. 123) contributing to the distrust. The political arena is highly contested because it provides access to an economy that enriches politicians, their friends, families and patrons (Brunette 2019; de Haas 2016, p. 45). Government’s consequence management is profoundly lacking as stated by (Republic of South Africa, Auditor-General of South Africa 2021; Republic of South Africa, KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Government 2021). The KwaZulu-Natal Framework on Consequence Management (Republic of South Africa, KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Government 2021) declared in its problem statement that the lack thereof resulted in low public confidence in, and poor perceptions of, government. There is a frequent comparison between the current and previous state presidents. The former President Zuma is seen to be charismatic but the current, President Ramaphosa, is seen to be aloof, contributing to the sentiment of distrust. This could reflect on the communication skills and personalities of both the figures or possibly tribalism or factionalism.

A focus group reported that public servants at a provincial hospital are often racist and ethnocentric. Patients are treated poorly; staff are dismissive and preoccupied with their cell phones. The group also expressed concerns about the lack of accountability for poor service by staff. This reflects poorly on the government, as the hospital is a government institution. The group felt that this behaviour conveyed an image of a divisive and uncaring government, which violates the rights of citizens to quality healthcare and fair services. Hence, civil society is more trusted than government because they are more visible and responsive to communities.

According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in (Pradhan 2021, p. 2), trust in government is earned by two drivers, namely, service delivery responsive to citizens’ needs and governments exercising their power in the public interest, display of integrity and openness. State capture and corruption related to Covid-19 procurement (Gibson 2021, p. 1), despite government’s commitment to rooting out corruption and the anti-corruption legislation, reveals that sectors of government did not act with integrity and the afore-mentioned experience by participants at a state hospital reflect poor and non-responsive service delivery.

Turning now to government’s communication platforms, participants expressed no dissatisfaction with them, although a few shortcomings were evident. The disability sector stated they would prefer audio-visual products, for example, music, videos and short movies because they engage better with the message when they see and hear as opposed to reading or listening to someone making a speech. Products in braille, as the preferred medium of communication for the blind, should be more widely produced by all government departments. The use of sign language at government events and on television and the status of sign language as an official language was commended.

Government communication products do not adequately cater for illiteracy or low literacy levels. Unmediated, face-to-face platforms are still preferred for communication with government. The visit from a political principal or government official helps to reassure and validate communities. Social media is widely used, however, limited access thereto restricts the reach of government communication efforts. Infrastructure inadequacies or cost of data and smart technology, or the lack of technological skills amongst the elderly, renders this platform unsuitable for the peri-urban, elderly and poor communities. Traditional platforms of communication such as print and electronic media are preferred.

Other weaknesses emerged. Government communication was reactive instead of proactive or anticipatory, hence failing to educate people. The example of the July 2021 riots was cited as an example. Government was aware of the threats but failed to respond in any way to prevent the riots, thereby failing to proactively effect behavioural and attitudinal change. The media sensationalizes incidents and sometimes publishes inaccurate and poorly researched stories. The use of the word ‘massacre’ to describe the events in Phoenix was inappropriate as it implies mass killing of hundreds of people. While the loss of lives cannot be condoned, 34 people were killed, the media’s use of the word led to over-generalizations about racism by criminals of Indian descent. People of Indian descent were victimised because of this. The media did not cover positive stories of diverse communities working together during the unrest. The media in South Africa is polarised; they are either seemingly for or against government or aligned to a certain political party or parties. The media, the fourth estate, plays a crucial role in informing, empowering, and holding the government accountable, but in some cases fails to act responsibly, objectively, and reliably. An example of this is the coverage by NewzroomAfrika (2021) of the President’s speech during his visit to Springfield Park after the 2021 civil unrest. The newsroom repeatedly flighted clips (a practice where an advertisement, for example, is shown, stopped and then shown again) where the President mentioned that ethnic and racial tensions appeared to be the cause of the unrest. However, they omitted the part where he categorically stated that after closer scrutiny, it was found that unseen forces with a deeper motive had pitted communities against each other.

Children do not understand the concept of race, unless parents tell them, as revealed by one participant. The participant stated their child could not differentiate between Whites, Indians and Africans but understood the differences in language and recommended that children and youth should be the main target audience of social cohesion programs. Social cohesion starts in the home and communities. As much as the government has a responsibility, individuals have a responsibility to build social cohesion. Many participants agreed that parents, caregivers and community leaders have a responsibility to teach their children to respect and embrace diversity.

Recommendations

The following recommendations will enhance communities’ sense of belonging, participation, inclusion, and trust, which are measures of a socially cohesive society as per the Social Cohesion Index. The recommendations are linked to the objectives of the study.

Objective 1

Defining Social Cohesion: Government communication must take cognisance of the language, literacy levels and special needs when communicating on social cohesion. Social cohesion campaigns must be coordinated, multi-sectoral and sustained. Events such as the Rugby World Cup, African Cup of Nations, and national team assets – Banyana Banyana, Proteas, Springboks and Siya Kolisi – unite diversity and create patriotism and national pride. The positive impact on social cohesion during and after such events and assets must be utilised as a springboard to sustain social cohesion. The media and all sectors of society must support government in this campaign. All parties must ensure that the communication is relevant to the diverse communication needs of language, channels and platforms to guarantee maximum reach and understanding for a change in mindset. The messages must show the responsibility of all South Africans in fostering social cohesion. As per the National Action Plan to Combat Racism, Racial Intolerance, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, the South African government must provide continuous diversity training to the South African National Editors’ Forum, media houses, and personnel to ensure ethical media reporting. The example of Siya Kolisi and the Springboks proves that people from different socio-economic, linguistic, racial and ethnic backgrounds can work together and achieve a shared goal. These are the kinds of stories that must be amplified by government, media, civil and private sectors in society. Government communication campaigns and graphics must promote social cohesion. The models and illustrations utilised in the images in government communication campaigns on, for example, gender-based violence, cable theft and other crimes must be reflective of the diversity of the South African population.

Politicians and government communication: Politicians influence people, their behaviour and attitudes, therefore they must display a strong moral fibre and serve as role models for South Africans. They must embrace diversity and honour their commitments. Their actions must give credibility to government messages to secure citizens’ trust. Politicians must prioritize the nation’s interests over party and self-serving interests. Inclusive action and leadership from government is needed to substantiate the declaration that South Africa belongs to all who live in it. Public servants and politicians must be trained to provide high-quality, non-discriminatory services. Communication plays a significant role in persuasion, coercion, compulsion and pervasion of a national set of values and standards of behaviour. Politicians, and administrators must use communication, substantiated by tangibles, to nurture and unite a nation aligned to the Constitutional principles and values.

Objective 2

The government messages must find expression in government’s actions. Government services must be aligned to its messages, for example, employment for all and services responsive to the special needs of people with disability. Government, the LGTBQIA+ and disability sectors need to implement a consolidated communication programme to educate, correct misinformation and debunk the myths associated with these communities. The campaigns must promote the rights of the disability and LGBTQIA+ communities, eradicate stigmatization and discrimination and ensure a conducive work environment. Messages from the government, amplified by stakeholders and politicians, must emphasize the humanness of people before race, gender, ethnicity, language, disability, sexual orientation, or class. Anti gender-based violence campaigns must prioritize violence against the LGBTQIA+ community and women in equal measure. Politicians’ reassuring presence and empathetic and decisive words would build trust with the LGBTQIA+ community and deter LGBTQIA+-directed violence.

The government must fairly implement affirmative action policies without prejudice or bias towards personal gain, appoint people based on merit and determine whether the policy should have a sunset clause. Affirmative Action policies must be implemented equitably and without corruption, nepotism or cronyism to benefit the intended communities thereby eradicating or decreasing the inequality and poverty that leads to tension and conflict amongst diverse communities. Affirmative action must benefit the poor and previously disadvantaged communities while enlisting support from the previously advantaged. Beneficiaries should include Coloureds and Indians, who are classified as Black and previously disadvantaged. The government should be more empathetic and responsive to the needs of all citizens, regardless of their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation or political affiliation. While affirmative action implementation is prioritised, the employment needs of White youth must be met. Government has a duty to create an enabling environment for employment and a stable economy, by implementing its economic policies fairly and equitably as per its communicated commitments. During times of crisis, many Whites, Coloureds, and Indians feel excluded due to the government’s inadequate support. Government must prioritise the needs of all communities equally. Black African communities have also reported feeling ignored by the government outside of election season.

Objective 3

Transformation and social cohesion campaigns must be implemented simultaneously because they complement each other. There is a need to unpack and debunk the myths around socio-economic transformation in a non-racially intimidating way, bearing in mind that transformation includes equal and equitable, efficient and effective service delivery to all citizens. Whites, Coloureds, Indians and Black Africans expressed frustration at the lack of employment opportunities and concerns about the effects of transformation. Affirmative action policies have affected the participants’ sense of belonging, inclusion and trust. Government communication and actions must assure various communities that they will not be left behind in the transformation process and that there will be equal opportunity for employment and access to employment opportunities for everyone. Government communication must educate on and acknowledge the roles diverse people play in transformation and recognise the needs of all South Africans, that is, employment; access to services; economic opportunities; and a better life. All South Africans aspire towards similar goals: safety and security, employment, ability to take care of and provide for their families, acknowledgment and respect, and a better life for their children.

Politicians must visit and engage with all communities, especially during times of crisis. The democratic legislative framework provides for platforms and structures for participation. Government must make optimum use of these platforms to listen and respond to community needs. They must be proactive in the identification and addressing of concerns before the eruption of protests. Persons who attend community, workplace and government meetings must feel safe and comfortable to voice their opinions without fear of reprisal, marginalisation or exclusion. Government officials, politicians, community, traditional and business leaders must be schooled to consider alternate or differing thoughts and philosophies.

Competition for resources and poor service delivery undermines social relations at the community level. Basic services such as water and energy security, security of person, space and property must be drastically improved to attract investment, create jobs and ensure peoples’ sense of belonging and trust. Enhanced inter-departmental and cluster communication must be substantiated with action and cooperation to prevent a silo system of working, improve responsive service delivery and restore confidence in government communication. One of the purposes of government communication is to account. Hence, feedback to the citizenry on service delivery achievements, non-achievements and remedial plans to address the latter builds trust and prevents protests that manifest as racism or tribalism. Politicians must keep their party conflicts out of the public service. They represent the government and must act with integrity, empathy, and objectivity and ensure service delivery to their constituencies.

Regarding developing a multi-lingual community, the learning of isiZulu, English, and Afrikaans in eThekwini should be promoted rather than compelled and qualified isiZulu educators should be hired for English and Afrikaans schools. Embracing African languages to maintain the cultural roots of the community, as well as drawing from diverse cultures to shape a South African identity is essential. Meetings and public events organisers must provide translators for the various languages. For example, when the KwaZulu-Natal Legislature hosts its community meetings, the predominant medium of engagement is isiZulu. Non-isiZulu speaking attendees are given earphones to listen to the English translation. This facility must be available at all government, private sector and civil society meetings to target a diverse linguistic audience.

A communication programme on scarce and critical skills, employment and economic opportunities must be executed at schools and tertiary institutions to encourage learners to pursue these career paths. The education system and curriculum must be amended to suit the changing employment market and required skill sets. Educators must be reskilled and upskilled to keep pace with the educational needs of a changing employment market.

A government communication programme on human values in all sectors of society is recommended. The education system must emphasise human values in the teaching curricula and nurture learners and students to be productive, disciplined and constructive contributors to the growth of the country. Education facilities, employment and skills development opportunities for persons with disabilities must be urgently addressed to advance their levels of literacy, employability and inclusion in the economy.

A government communication programme on ethics, respect for diversity and dedication to people-centred service is recommended for all public servants, especially those in critical services of health care, education and social welfare to give effect to the Batho Pele (People First) Principles. By fostering a service-oriented workforce, government can create a more caring, productive, and cohesive society, ensuring law-abiding citizens and inspiring trust in government. The government must prioritize respect for the rule of law at every level of society. This will attract investors and eliminate competition for resources that often leads to prejudice.

In addition, participants recommend that government communication, substantiated by action, must address the following to ensure a socially cohesive society:

• Consequence management and eradication of corruption;

• Equal application of the law;

• Improve education facilities for people with disabilities;

• Access to employment opportunities for people with disabilities and LGBTQIA+;

• Develop capacity of employers to manage the needs, render fair treatment and protect the human dignity of LGBTQIA+ individuals in the workplace and at interviews;

• Government anti-GBVF campaign must address murders and violence against the LGBTQIA+ community;

• Protect human rights, ensure fulfillment of duties and promote accompanying responsibilities;

• Education on the economy, healthy competition, ethical governance and business practices;

• Inform and educate on government’s procurement practices;

• Invest in human development and diversity training of public servants because they are also government communicators/ambassadors;

• Stop nepotism and political patronage;

• Educate individuals and communities about good values, ethics and integrity;

• Implement Batho Pele principles fairly and professionalise the public sector (Republic of South Africa, Department of Public Service and Administration 1997); and

• Support communication with tangibles

Government must develop and promote servant leaders and people of integrity in the executive and the administration. Politicians must lead by example and prioritise the needs of their constituents.

Objective 4

Simple words and sentence construction in government print products as well as the inclusion of illustrations would help communication with people with low literacy levels. Use of audio-visual products, for example, music, videos and short movies and more braille products will enhance communication with people with disabilities. Government products must be available in all official languages. The face-to-face platforms for community engagements must be strengthened with sincerity, active listening, empathy, humility and action.

Other recommendations emerged. Although they do not directly apply to government communication, they can be used to inform government communication messages and content and therefore are included here. Efforts must be made to improve the literacy levels of persons with disabilities. Departments in the social, economic, justice and other relevant government clusters must work together to engage with and ascertain the specific needs of and provide employment opportunities to such persons. Failure to meet the disability employment objectives of the affirmative action policies must be investigated and remedial action must be implemented. The renovation of facilities to be disability and LGBTQIA+ friendly must be prioritised and delivery of such interventions must be duly communicated.

Conclusion

This study revealed widespread issues that participants rarely discussed with one another. The data collected through questionnaires showed that government is saying the correct things as desired by the participants. The disconnect between government’s words and actions angered participants. Effective government communication must eliminate barriers to social inclusion, participation, belonging, and trust. Shaping a society involves changing attitudes and behaviours. The government must lead by example and work hard to build trust. Improved service delivery, access to employment, and addressing the needs of marginalized communities can help achieve this.

Government and all South Africans need to develop and robustly promote a national compact, cognisant of the diverse cultural and traditional practices, giving effect to the Constitution. Government messaging must encourage positive behaviour, prioritise consequence management for corrupt individuals, and broadcast the arrests and sentencing of criminals in government to deter future misconduct. Media must ensure independence, fairness and objectivity and government must ensure it does not interfere or judge the media for negative government-related news, provided that the coverage is factual, fair and unbiased.

The research concludes that government communication can, and does to an extent, contribute to social cohesion and behavioural change. However, the government communication must be substantiated by tangible deliverables and improved quality of life to enhance its communication and achieve greater social cohesion. There are many heartwarming stories in South Africa and in the world that bear testimony to the triumphs born out of unity in diversity. These are lessons that the South African government and governments of the world can take from its ordinary citizens who place humanity above personal gains, wealth, ambition and greed. Governments must allow themselves to be led by their people to create a safer, social cohesive and harmonious nation. Government’s actions must support its words or else, government sounds like, as one participant said, quoting from the book of Corinthians in the Bible, ‘just a noisy clanging gong’.

References

Anheier, H. K. & Knudsen, E. L. 2023, ‘The 21st Century trust and leadership problem: Quoi faire?’, Policy Insights,

vol. 14, no. 1 pp. 139-148. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13162

Auriacombe, C. J. 2016, ‘Towards the construction of unobtrusive research techniques: Critical considerations when conducting a literature analysis’, African Journal of Public Affairs, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 1-19. http://hdl.handle.net/2263/59036

Baloyi, E. M. 2018, ‘Tribalism: Thorny issue towards reconciliation in South Africa – A practical theological appraisal’, HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies, vol. 74, no. 2, article 4772. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v74i2.4772

Banerji, A. 2015, ‘Global and National Leadership in Good Governance’, United Nations Chronicle, vol. 52, no. 4. https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/global-and-national-leadership-good-governance. https://doi.org/10.18356/58a6d2ba-en

Bangani, A. & Vyas-Doorgapersad, S. 2020, ‘The implementation of gender equality within the South African Public Service (1994-2019)’, Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review, vol. 8, no. 1, article 353. https://doi.org/10.4102/apsdpr.v8i1.353

Bastart, J., Rohmer, O., & Popa-Roch, M.-A. 2021, ‘Legitimating discrimination against students with disability in school: The role of justifications of discriminatory behaviour’, International Review of Psychology, vol. 34 no. 1, pp. 1-11. https://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.357

Bellafante, G. 2024, ‘Sexism, Hate, Mental Illness: Why Are Men Randomly Punching Women?’, New York Times, April 12, Retrieved 2024-05-06. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/12/nyregion/new-york-city-random-attacks-women.html

Brunette, R. 2019, The Politics of South Africa’s patronage system (Part One), University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, August 23. https://www.wits.ac.za/news/latest-news/opinion/2019/2019-08/the-politics-of-south-africas-patronage-system-part-one.html

Burns, J., Hull, G., Lefko-Everett, K., & Njozela, L. 2018, Defining social cohesion, SALDRU Working Paper number 216, Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, University of Cape Town. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381407364_Defining_Social_Cohesion

Cele, N. 2016, ‘Living with albinism in South Africa’, Al Jazeera, June 13, Retrieved 2021-04-21. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2016/6/13/living-with-albinism-in-south-africa

Chauke, A. 2011, ‘Julius Malema says sorry for “racial slur”’, Timeslive, October 21, Retrieved 2021-04-24. https://www.timeslive.co.za/politics/2011-10-21-julius-malema-says-sorry-for-racial-slur/

Chyung, S.Y., Roberts, K., Swanson, I., & Hankinson, A. 2017, ‘Evidence-based survey design: The use of a midpoint on the Likert Scale’, Performance Improvement, vol. 56, no. 10, pp. 15-23. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.21727

Davis, R. 2024, ‘How the reports into the July 2021 unrest let South Africa down’, Daily Maverick, January 30, Retrieved 2024-08-25, <https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2024-01-30-how-the-reports-into-the-july-2021-unrest-let-south-africa-down/>

Duma, N. 2020, ‘Durban Girls’ College probing alleged racism’, Eyewitness News, Retrieved 2021-07-06. https://www.ewn.co.za

Ero, I. 2019, ‘South Africa must step up action to end “racial discrimination” against people with albinism, says UN expert’, United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, South Africa, September 27, Retrieved 2021-05-03. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2019/09/south-africa-must-step-action-end-racial-discrimination-against-people

Expert Panel into the July 2021 Civil Unrest 2021, Report of the Expert Panel into the July 2021 civil unrest, November 29, Durban, Republic of South Africa. https://www.thepresidency.gov.za/sites/default/files/2022-05/Report%20of%20the%20Expert%20Panel%20into%20the%20July%202021%20Civil%20Unrest.pdf

Felix, J. 2023, ‘DA KZN Councillor admits sending racist voice note, party has conducted probe’, News 24, January 10, Retrieved 2023-02-08. https://www.news24.com/news24/politics/political-parties/da-kzn-councillor-admits-sending-racist-voice-note-party-has-conducted-probe-20230110

Fletcher, J. 2016, ‘Born free, killed by hate – The price of being gay in South Africa’, BBC News, April 7, Retrieved 2021-04-24. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-35967725

Freira, G., Mora, M. E. G., Ibarra, G. L., & Orellana, S. S. 2020, Social inclusion in Uruguay, World Bank, Washington D.C. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/748291595402326745/pdf/Social-Inclusion-in-Uruguay.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1596/34229

Gibson, E. 2021, ‘PPE corruption: SIU refers SANDF cases to NPA for prosecution, moves to recover millions from contractors’, News24, November 17, Retrieved 2021-11-23. https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/ppe-corruption-siu-refers-sandf-cases-to-npa-for-prosecution-moves-to-recover-millions-from-contractors-20211117

Gqirana, T. 2016, ‘DA suspends Penny Sparrow over racist comments’, Mail & Guardian, January 4, Retrieved 2022-06-01. https://mg.co.za/article/2016-01-04-da-to-suspend-sparrow-over-racist-comments/

de Greef, K. 2019, ‘The unfulfilled promise of LGBTQ rights in South Africa’, The Atlantic, July 2, Retrieved 2021-04-24. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/07/southafrica-lgbtq-rights/593050/

de Haas, M. E. 2016, ‘The killing fields of KZN: Local government elections, violence and democracy in 2016’, South African Crime Quarterly, vol. 57, pp. 43–53. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2016/i57a456

Healy, M. 2019, ‘Belonging, social cohesion and fundamental British values’, British Journal of Educational Studies, vol. 67, no. 4, pp. 423-438. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2018.1506091

Human Rights Watch 2024, Court upholds anti-homosexuality act: Entrenches discrimination, enhances risk of anti-LGBT violence, April 4, Retrieved 2024-06-05. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/04/04/uganda-court-upholds-anti-homosexuality-act

Kennedy, C. 2019, ‘We come from different backgrounds, different races, and we came together with one goal’, The 42, November 2, Retrieved 2022-08-23. https://www.the42.ie/kolisi-speech-4876581-Nov2019/

Kumar, R. 2014, Research methodology: A Step-by-step guide for beginners, 4th edn, Sage Publishers, Thousand Oaks.

Laloo, E. 2022, ‘Ubuntu Leadership: An explication of an Afrocentric leadership style’, The Journal of Values-Based Leadership, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 209-219. https://doi.org/10.22543/1948-0733.1383

Lefko-Everette, K. 2016, Towards a measurement of social cohesion for Africa: A discussion paper prepared by the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation for the United Nations Development Programme, June 29, United Nations Development Programme Regional Centre for Africa, Addis Ababa. https://www.undp.org/africa/publications/towards-measurement-social-cohesion-africa-discussion-paper-prepared-institute-justice-and-reconciliation-undp

Maharaj, B. 2020, ‘“Corrupt C*****s”: Anti-Indian prejudice in the Durban Metro?’, Daily Maverick, September 10, Retrieved 2021-04-24. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2018-09-10-corrupt-cs-anti-indian-prejudice-in-the-durban-metro/

Masson, E. 2022, ‘Africans were racially profiled in Phoenix – Durban Mayor’, Mail & Guardian, March 1, Retrieved 2023-03-03. https://mg.co.za/news/2022-03-01-africans-were-racially-profiled-in-phoenix-during-july-unrest-mxolisi-kaunda/

Mathekga, R. 2015, ‘State evolution and sovereignty: The Case of South Africa’, In Ndletyana, M. & Maimela, D., Essays on the evolution of the post-apartheid state: Legacies, reforms and prospects, Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection, Real African Publishers, Johannesburg, pp. 251-267.

McCarry, P. 2023, ‘This time people were expecting’, Sports Joe, October 23, Retrieved 2023-11-18. https://www.sportsjoe.ie/rugby/siya-kolisi-world-cup-win-294597

Mohajan, H. K. 2018, ‘Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects’, Journal of Economic Development, Environment and People, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 23-48. https://doi.org/10.26458/jedep.v7i1.571

Moser, M. & Korstjens, I. 2018, ‘Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis’, European Journal of General Practice, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 9-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091

Mphepo, T. 2020, ‘Persons with albinism further marginalised and discriminated in Covid-19 response’, Daily Maverick, July 23, Retrieved 2021-04-24. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-07-23-persons-with-albinism-further-marginalised-and-discriminated-in-covid-19-response/

Mswela, M. 2017, ‘Violent attacks persons with albinism in South Africa: A human rights perspective’, African Human Rights Law Journal, vol. 17, no.1, pp. 114-133. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-8dc964ce9. https://doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2017/v17n1a6

Newzroom Afrika 2021, https://x.com/Newzroom405/status/1415964713339531266

Nxumalo, S. 2020, ‘LGBTQI activist slain in Durban “hate” crime’, Mercury, February 10, Retrieved 2021-12-04, https://www.iol.co.za/mercury/news/lgbtqi-activist-slain-in-durban-hate-crime-42460243

Nyumba, T. O., Wilson, K., Derrick, C. J., & Mukherjee, N. 2018, ‘The use of focus groups discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation’, Methods in Ecology and Evolution, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 20-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12860

Open Doors International 2023, World Watch List 2024, Retrieved 2024-05-06, https://www.opendoors.org/en-US/persecution/countries/

Otto, H. & Fourie, L. M. 2016, ‘Theorising participation as communicative action for development and social change’, Communicare, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 21-39. https://doi.org/10.36615/jcsa.v35i1.1600

Pandhey, P. & Pandhey, M. M. 2015, Research Methodology: Tools and Techniques, Bridge Centre, Buzau.

Pradhan, S. 2021, Tackling the crisis of citizen trust in governance: The World Bank Group imperative. https://blogs.worldbank.org. (Accessed on 20 December 2021).

Reygan, F. 2019, ‘Sexual and gender diversity in schools: Belonging, in/exclusion and the African child’, Perspectives in Education, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 90-102. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v36i2.8

Republic of South Africa, Government Communication and Information System 1996, Communications 2000, A Vision for Government Communications in South Africa: Final Report on Government Communications to Deputy President Thabo Mbeki, October, Comtask, Pretoria https://www.gcis.gov.za/content/resource-centre/reports/comtask

Republic of South Africa 1996, Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Government Printers, Pretoria.

Republic of South Africa, Auditor-General of South Africa 2021, Consolidated General Report of National and Provincial Audit Outcomes: PFMA 2020-2021, Public Finance Management Act General Report, Auditor-General of South Africa, Pretoria. https://www.agsa.co.za/Reporting/PFMAReports/PFMA2020-2021.aspx

Republic of South Africa, Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation 2014, Medium Term Strategic Framework 2014-2019, The Presidency, Republic of South Africa, Cape Town. https://www.greenpolicyplatform.org/national-documents/south-africa-medium-term-strategic-framework-2014-2019

Republic of South Africa, Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation 2020, Medium Term Strategic Framework 2019-2024, Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation, Pretoria. https://www.dpme.gov.za/keyfocusareas/outcomesSite/Pages/mtsf2021.aspx

Republic of South Africa, Department of Public Service and Administration 1997, Batho Pele Vision: A Better life for all South Africans by putting people first, Retrieved 2022-08-10. https://www.dpsa.gov.za/dpsa2g/documents/acts®ulations/frameworks/white-papers/transform.pdf

Republic of South Africa, KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Government 2021, KwaZulu-Natal framework on consequence management, March 2021, Retrieved 2022-08-18. http://www.kznonline.gov.za/images/Downloads/Publications/KZN_ConsequenceManagement_Framework.pdf

Republic of South Africa, National Planning Commission 2011, National Development Plan – Vision for 2030, RP 270/2011, Government Printer, Pretoria. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/devplan2.pdf

Republic of South Africa, The Presidency 2011, State of the Nation Address 2011, Retrieved 2022-10-24. https://www.gov.za/news/speeches/state-nation-address-his-excellency-jacob-g-zuma-president-republic-south-africa

South African Human Rights Commission 2022, Media Advisory: Complaints received against Mr Julius Malema and the EFF in respect of statements made during the October EFF Provincial People’s Assembly in the Western Cape, November 9. https://www.sahrc.org.za/index.php/sahrc-media/news-2/item/3348-media-advisory-complaints-received-against-mr-julius-malema-and-the-eff-in-respect-of-statements-made-during-the-october-eff-provincial-people-s-assembly-in-the-western-cape

Statistics South Africa 2021, Quarterly labour force survey: Quarter 2, 2021, August 24, Retrieved 2021-12-14, https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02112ndQuarter2021.pdf

Statistics South Africa 2022, Census 2022. Retrieved 2024-01-23, https://census.statssa.gov.za/#/province/5/2

Statistics South Africa 2023, Statistics South Africa on Quarterly Labor Force Survey quarter three 2023, November 14. Retrieved 2024-01-24, https://www.gov.za/news/media-statements/statistics-south-africa-quarterly-labour-force-survey-quarter-three-2023-14

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights 2024, UN experts warn Islamophobia rising to “alarming levels”, Retrieved 2024-05-06. https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2024/03/un-experts-warn-islamophobia-rising-alarming-levels

von Holdt, K. 2019, The Political Economy of Corruption, Elite-formation, Factions and Violence. Society, Work & Politics Institute: Working Paper no. 10, February. https://www.swop.org.za. Accessed on 5 March 2023.

Welman, J. C. & Kruger, S. J. 2003, Research Methodology, 2nd edn, Oxford University Press, Cape Town.

Wright, J. 2024, ‘Siya Kolisi dedicates Springboks’ win over the All Blacks to “South Africans who are still not free”’, August 31, Planet Rugby, Retrieved 2024-09-01. https://www.planetrugby.com/news/siya-kolisi-dedicates-springboks-win-over-the-all-blacks-to-south-africans-who-are-still-not-free

Youth Policy Committee Gender Working Group 2019, Hate Crimes against Members of the LGBTQIA+ Community in South Africa, South African Institute of International Affairs, August 2, Retrieved 2022-06-05. https://saiia.org.za/youth-blogs/hate-crimes-against-members-of-the-lgbtqia-community-in-south-africa/

Zondo, R. M. M. 2022, Judicial Commission of Inquiry into State Capture Report: Part 2 Volume 2: Denel, Commission of Inquiry into State Capture, Republic of South Africa. https://www.saflii.org/images/statecapturereport_part2_vol2.pdf