Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 17, No. 1

2025

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

The Challenges of Immigrant Policy Formation in Trinidad and Tobago: A Civil Society Perspective

Shelly Ann Tirbanie1, Michał Pawiński2,*

1 Independent Researcher, stirbanie@yahoo.com

2 University of the West Indies, michal.pawinski@uwi.edu

Corresponding author: Michał Pawiński, University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad and Tobago, michal.pawinski@uwi.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v17.i1.9164

Article History: Received 30/05/2024; Revised 13/01/2025; Accepted 15/01/2025; Published 31/03/2025

Citation: Tirbanie, S. A., Pawiński, M. 2025. The Challenges of Immigrant Policy Formation in Trinidad and Tobago: A Civil Society Perspective. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 17:1, 81–94. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v17.i1.9164

Abstract

In 2019, the government of Trinidad and Tobago (T&T) embarked on a Venezuelan Registration Exercise with over 16,000 Venezuelan nationals registered. The migratory flows such as the present experience have highlighted the weaknesses in the existing national policy framework of T&T. The inclusion of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) in the process of policy formation has been limited, while communication with governmental stakeholders to solve the challenges has been underwhelming. The present study conducted interviews with 12 CSOs in T&T with the objective of identifying the challenges they face in forming and implementing migrant policy, their experiences with political stakeholders, and their expectations of future collaboration. The research findings propose the need for the Civil Society Network in T&T and the Caribbean region to address the escalating migratory crisis.

Keywords

Civil Society Organizations; The Caribbean; Migrant Integration; Policy Development; Venezuelans

Introduction

Within the Caribbean, small island states have faced a myriad of challenges in the 21st Century, from the heightened vulnerabilities of climate change to the tumultuous COVID-19 pandemic. The manifestation of forced displacement within the region has been interposed between these anomalies and produced the greatest outflow of refugees the region has ever seen. Ellis (2017, p. 22) affirms that ‘the crisis in Venezuela is a problem for the country, and the region that neither international law nor multilateral institutions are well equipped to handle’. Nonetheless, despite this circumstance, the state’s hemispheric neighbours have facilitated migrants, and countries such as Colombia, Brazil, Guyana, and T&T have made strides to promote different levels of integration (Chaves-González & Echevarría-Estrada 2020). The current migratory crisis in Latin America and the Caribbean presents an extraordinary opportunity for Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) in Trinidad and Tobago to be included in migrant integration and to a greater extent in policy development within the field of migration policy. It is therefore under this premise that this paper pursued the contributions of CSOs and examined their perspective on the challenges that exist for developing national policies that would inform and influence migrant integration in Trinidad and Tobago. Within this context, this research was guided by the following questions: What are the opportunities that exist and the challenges that must be overcome for CSOs to be part of policymaking processes related to migrant integration? What are the recommendations from the CSOs for developing policies that facilitate migrant integration?

Civil Society in Migrant Integration and Policy Formulation

The genesis of CSOs can be traced to the antiquity of the enlightenment period (DeWiel 1997) and when mobilized, civil society organizations can present themselves as a force to be reckoned with as they have the power to influence not only elected officials but the citizenry (Jezard 2018). Within the field of migration, a report from the European Economic Social Committee Study Group on Immigration and Integration echoed similar sentiments, highlighting the significance of this type of influence. The report proposes that ‘civil society organizations play an important role in migrant and refugee integration; they carry out valuable work assisting or even substituting for government by providing guidance and support for the integration process’ (Aasmaa 2020, p. 4). Moreover, findings from the same study suggested that the expertise gained from these practitioners should be used when ‘designing integration strategies and policies to ensure that they correspond to the actual needs and circumstances, which would optimally benefit migrants’ (Aasmaa 2020, p. 4). Further recommendations from this report also encouraged member states within the European Union to establish and maintain cooperation between CSOs and government bureaucracies to create synergies that would fuse knowledge, practice, and resources available on both ends.

In a Caribbean context, civil society plays a role in policy formulation and implementation particularly within the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM) and the domain of regional integration. Bowen (2013, p. 94) states, ‘an envisioned role for civil society organizations in regional development has implications for public policy; the CSOs’ participation itself has implications for the approach to formulating policy’. In essence, his reflections not only advocate for strategic measures and legislative frameworks that can bolster CSOs’ involvement in policy development at a national and regional level, but he also regards this collaboration as a best practice. The consultations, in this regard, would not be mere opinions but substantial contributions between state and non-state actors in planning and decision-making (Bowen 2013). It is also important to note that within this region’s milieu, the terms civil society, non-profit, non-governmental, and community-based organizations are used interchangeably and appear to lack conceptual clarity. However, like CSOs in other regions, Caribbean organizations all have similar characteristics: they are voluntary, independent of both commercial and governmental entities, and do not operate for personal gain. Many of these organizations also operate under a sub-national scope (Bowen 2013, p. 83). In Trinidad and Tobago, for instance, both CSOs and NGOs can be legally registered under the Non-Profit Organisations Act No. 7 of 2019. Given this preamble, hereinafter the terms Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), and Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) will be used in a transposable manner.

The writings of Lewis (1994) have parallel connotations to those of Bowen (2013). In Lewis’ view, NGOs should be considered significant in the regional debate on development in the Caribbean, and he argues that crisis can provide a unique opportunity for NGOs to explore and promote alternatives which can transform an economy. CBOs and NGOs have not only propelled the concept of power into a new dimension but now they can collectively respond to and defend the vulnerable in society and can be considered a primary force of social movement and change in the Caribbean. CSOs are therefore a ‘vehicle through which participation in the development process can be achieved’ (Montoute 2010, p. 2). In numerous instances, apart from policy formulation, civil society groups within the Caribbean have demonstrated how beneficial and meaningful their contributions can be. For instance, Montoute (2010) highlights their role in conflict resolution: civil society actors were brought in to resolve a dispute in St. Vincent and the Grenadines after the introduction of the 1998 Gratuity Bill. This was also done in Guyana as conflict arose after their 1997 general elections.

Further influence was achieved in Trinidad and Tobago where CSOs were able to capture, through education, not only the interest of government officials, but also employers and citizens, on the challenges met by persons with disabilities or special needs. This type of advocacy led to the endorsement of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities by the government of Trinidad and Tobago in 2015 and amplified awareness amongst employers on the requirements and prospects that can be available for persons with disabilities (Cadiz-Hadeed et al. 2020). Within the context of migration, local arms of CSOs have proven to be benevolent as they have made considerable strides in providing services, especially as it relates to facilitating migrants. However, there are some organizations whose assessments of the present situation have not been adequately recognized and documented in either field (integration or policy formulation). It is noteworthy that the civil society sector in Trinidad and Tobago is rich with organizations representing a diverse array of themes and social issues. Many of them, however, are officially unregistered, or their activity status is unknown.

The Migration Dynamics Within Trinidad and Tobago

Since the death of the late President Hugo Chavez in 2013, Venezuela has been plunged into crisis as the struggle for political power prevails, leading to economic and social difficulties. This turmoil has sparked the mass migration of Venezuelans to other parts of Latin America and the Caribbean, and this has been deemed one of the largest forced displacements in the Western Hemisphere (Ellis 2017; BBC News 2021). In terms of statistics, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that, as of October 2022, there are over seven million Venezuelan migrants and refugees in the world (UNHCR 2022).

Given this context, the twin-island Republic of Trinidad and Tobago has the highest migrant stock in the region, and figures from the World Bank estimate that from 2010 to 2015 there has been an increase in the number of migrants from 2.67% to 3.7% respectively (Anatol et al. 2013; World Bank 2023). Migration to Trinidad and Tobago in some regard has been facilitated by conventions such as the CARICOM Free Movement of Skilled Persons Act (1997), which outlines that skilled persons can move and work throughout member states once they have been granted a Certificate of Recognition. In other circumstances, however, such as those arising out of the South American region, migration to this twin island nation has been largely perpetuated by internal conflict and social instability which has led to massive displacement.

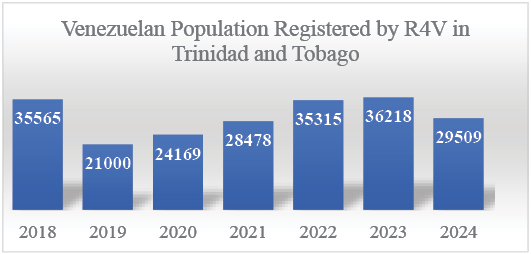

In 2019, the government of T&T embarked on a Venezuelan Registration Exercise and this process authorized Venezuelan nationals in irregular circumstances to work for a period of one year. That said year, over 16,000 Venezuelan nationals were registered and additionally, the Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) was launched to capture data for monitoring the movement and progress of migrants within Trinidad and Tobago. It should be noted that, as of March 2021, over 13,000 Venezuelans have been re-registered and one year later, on March 22nd, 2022, it was reported that those who participated in the exercise had been granted an extension on their permits until 31st December 2022 (Alvarado 2022; Trinidad Express Newspapers 2022; International Organization for Migration 2020). It is, however, difficult to determine the actual number of Venezuelan migrants to Trinidad and Tobago due to the proximity of the island to Venezuela and the permeability of the sea border. Some estimated year-by-year registration patterns are provided by the Inter-Agency Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V), as illustrated in Figure 1.

Migratory flows such as the present experience have highlighted the weaknesses in the existing national policy framework of Trinidad and Tobago and as a matter of urgency the state implemented ‘a phased approach towards the Establishment of a National Policy to Address Refugee and Asylum Matters’ (Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, Parliament Joint Select Committee on Human Rights, Equality and Diversity 2020). The Cabinet of Trinidad and Tobago adopted this proposal in 2014, and it outlines the determinants that would be necessary if a policy is to be transformed into law (Grey 2020). It should be noted however that this ‘phased approach’ is just a response to a crisis and not a policy in itself. With this in mind, we note other instruments, such as the Republic’s Constitution; its 1976 Immigration Act; and international agreements which the state has acceded to, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, and the International Convention on the Rights and Protections of Migrant Workers, that all act as a guide to the nation, as they deal with those who are undeniably displaced (UNHCR 2016). Despite the existence of those legal frameworks, it is vital to note that Trinidad and Tobago did not sign the 1951 Convention.

Figure 1. Venezuela Population Registered by R4V in Trinidad and Tobago. Source: R4V, n.d.

Other state-CSO initiatives included a National Joint Select Committee, which was held at the Fifth Session of the Eleventh Parliament in 2020. This committee held an inquiry on the treatment of migrants and focused specifically on the rights to education, employment, and protection from sexual exploitation. A report from The Joint Select Committee (Republic of Trinidad and Tobago Parliament 2020) was generated from this inquiry with several recommendations in relation to CSOs. The manuscript pointed out that in the process of building capacity and resources, a multi-stakeholder approach is needed and should comprise UN agencies, CSOs, the private sector, and other government stakeholders. This would facilitate dialogue and research, co-create solutions, and provide technical assistance and expertise, all of which would contribute to the development of political, legal, and social frameworks that would help to manage migration and the protection of refugees and asylum seekers in Trinidad and Tobago.

It is noteworthy that the data gathered, and recommendations represented, at the Joint Select Committee originated from a few members within civil society. As such, the dilemma at hand is this: the magnitude of decision-making processes and the building of norms and policies at a national level should not be placed only in the hands of the minority (as illustrated in the Joint Select Committee). Such proceedings should be a holistic forum, where prior to such engagements, actors are able to come together to determine how best stakeholders can maximize the latent opportunities of migrant integration.

Methodology

A qualitative research design was employed for this project and data collection comprised twelve standardized, open-ended interview sessions with one person from selected CSOs. The average time taken to complete an interview was one hour and thirty minutes. All sessions were recorded. One session was held face-to-face, and eleven were conducted using the Zoom platform. This online medium was suitable because of pandemic restrictions at the time and encouraged an open environment as interviewees were in familiar, convenient settings. The ethics approval from the Campus Research Ethics Committee of The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Campus (approval CREC-SA.1501/04/2022) was pursued and permission was granted to conduct a study amongst CSOs in Trinidad and Tobago. The interviews were conducted between 21st April and 2nd June 2022.

Sampling Procedure

A typology of CSOs identified by Banulescu-Bogdan (2011) was used to categorize potential organizations that function within the field of service provision, advocacy, implementation/monitoring, and policy formulation. Subsequently, a list comprising twenty-three organizations was created based on readings and further inquiry. Purposive sampling (Johnson & Christensen 2019) was then used to refine this list. The purposive sampling technique was relevant to this research as it assisted in the development of inclusion criteria. Specifically, organizations targeted for this study are civil society agents that provide services to migrants; agents that have the potential to offer services to migrants and members that have the potential to contribute to policy development within the field of migration. In addition to this technique, the snowballing sampling technique was incorporated as part of the research design. The snowballing procedure was executed at the end of each interview when interviewees were asked to identify other potential organizations that had similar characteristics as outlined within the inclusion criteria. Using both sampling methods, the sample size for this research was narrowed to twelve organizations. Of the interviewees, 5 were male and 7 were female. Six organizations had been operating for over fifteen years, two for between 7-9 years, and four for between 4-6 years. Of the twelve organizations that participated, seven were not given opportunities for consultation while five had consultancy experience with political stakeholders (see Table 1). Those organizations that had consultancy experience will be identified as ‘Interviewee (#) CE’ (Consultancy Experience), while those organizations that did not have consultancy experience will be identified as ‘Interviewee (#) NCE’ (No Consultancy Experience).

Data Analysis Method

Following data collection from interviews, recorded content was transcribed. The transcriptions were then analyzed thematically. Thematic analysis is a method in qualitative inquiry that goes beyond counting explicit words and phrases. It focuses on identifying and describing both implicit and explicit ideas within data (Guest et al. 2020). This analytical approach organizes related data sets into themes so that recurrent patterns can be revealed (Sarantakos 2017). For this research, this approach to data analysis was chosen because it presents an avenue for future researchers to review and assess primary data collected by this project. The themes generated from this research were supported by the literature review and this gave the findings presented below a level of credibility. The major themes identified are as follows: Challenges of forming and implementing migrant policy; CSOs’ experience with political stakeholders; and recommendations, expectations, and cross-CSO collaboration.

Sub-themes were also generated from the raw data, and its determinants were grouped using inductive coding. Provalis QDA Miner was used for analysing the thematic/inductive style undertaken by the research paper.

Findings

Challenges of Forming and Implementing a Migrant Policy

Given the multitude of quandaries faced by the migrant community, respondents were probed to give their view on what are some of the challenges with forming a migrant policy in Trinidad and Tobago. The major stressor for CSOs is that they operate within the parameters of an outdated legislation. For instance, Interviewee 2CE reports ‘officially, laws have not changed in order to say that Trinidad and Tobago welcome refugees to be regularized.’ This view was also supported by Interviewee 3NCE who states, ‘even though we signed on to the 1975 Convention (…) we don’t have laws here to facilitate migrants and refugees so the challenge will be those laws that’s why the government works through our community groups and NGO’s.’ The issue with the current legal framework is also explicitly problematized by Interviewee 10CE:

the immigration act that we have is very old (1976). It needs to be updated. It’s very difficult, for example, for people to get residency, to get work permits. It discriminates against persons with HIV. So that needs to be significantly recalled, particularly in a time when we have a declining growth rate, as well as labour needs in certain sectors, like agriculture, in the interest of food security.

Altogether, this deficiency and ‘lack of legal framework/policy for asylum-seekers/refugees in T&T is a concern’ (Interviewee 6CE).

The preceding responses revealed a second challenge: the lack of political will was identified by some organizations as an element that stymies progress. Specifically, Interviewee 4NCE notes within the field of migration ‘there’s a lot of potential, unrealized potential. I just think its lazy politics’. Interviewee 1NCE strongly argues that ‘it has to start with a willingness on the part of policymakers to really accept that this is an issue that we have to deal with and for too long, our policymakers (…) have buried themselves in the sand’. Another interviewee goes further to claim that ‘what actually makes the difference is whether or not the policymakers see something like this in their best interests, whether or not there’s political will’ (Interviewee 10CE). Similar sentiments were shared by Interviewee 9CE who expands on the idea of political interest by explaining that ‘what happened eventually though in talking about policy … the government of Trinidad and Tobago did not want migrants in Trinidad, meaning Venezuelans. All of a sudden, when certain corporations saw the opportunity to get cheap labour, it was a total 180 [degree turn]’.

The lack of political will connects to the third challenge which is a policy implementation deficit that plagues Trinidad and Tobago. According to Interviewee 4NCE, ‘when you look at a lot of policies developed by international organizations, more than likely you could find somebody from the Caribbean involved in that policy development. We are great policy makers. We create a lot of policy. The execution of the policy is where the issues are’. In this regard, President of the Caribbean Development Bank, Dr W. Smith, elaborated on the importance of civil society as he addressed a conference entitled Caribbean Leadership and Transformation Forum. Dr Smith stressed that ‘in these turbulent times, the ability to drive through a reform programme necessitates securing buy-in and support from as wide a stakeholder base as possible, including the private sector and civil society’ (Caribbean Development Bank 2017). It is in this same manner that Interviewee 8NCE remarks:

I don’t think that a migrant policy could be developed in isolation (…) I think that there was an economic development board, lets dust off those plans, and we don’t need to reinvent the wheel. We had a Vision 2020; we had a Vision 2030. This is why I talked about execution. I want you to tell me which one of the items of that plan you are aware of one and two has been implemented?

It is, therefore, symptomatic that 11 out of 12 interviewees expressed no confidence in political stakeholders implementing migrant policies needed to manage the current situation in the country. Interviewee 11NCE concludes we have what I term an implementation deficit in Trinidad and Tobago; to talk a lot. We do a lot of research. We have a lot of commission of inquiries into everything, but for the recommendations to see the day of light - the answer is regrettably no’.

The CSO Experience with Political Stakeholders

With reference to the accessibility of officials, respondents were asked to describe their last experience when they attempted to or did interact with government officials. Some interviewees specified that communication was ‘cordial or professional’ and one participant reflected that ‘stakeholder meetings, was actually very participatory like even the drafting of our refugee legislation was commendably participatory’ (Interviewee 10CE). Another remarked that they ‘work closely with government at senior, technical and operational levels to advance the protection and integration of refugees and asylum-seekers in T&T’ (Interviewee 6CE). At the same time, there are also instances when communication is favourable however persons would have ‘attended meetings to talk about migrant policy, but they did not allow us to see the policy […] we couldn’t be part of or see the actual draft’ (Interviewee 9CE). There are also times when communication ‘is not deep’ (Interviewee 12CE), and one may even say that ‘it’s always very good because they listen, but I think that they are good listeners’ this though is ‘depending only on the tier of government you’re officially communicating with, but they too are limited by the system’ (Interviewee 4NCE). In other circumstances, ‘the interaction with government officials is almost non-existent’ (Interviewee 11NCE).

The dynamics of the results earlier can illustrate the power of group identity, which according to Grant (1995, p. 15) is a ‘subjective perception that incorporates shared interests.’ The concept of group identity ushers in the idea of insider and outsider groups. According to Grant (1995, p. 15), an insider group is one that is ‘regarded as legitimate by government and consulted on a regular basis’, whilst an outsider group is one that is either ‘unable to gain recognition’ or simply does not seek a relationship with policymakers. Applying this notion to the findings it was observed that all the CSOs that had consultancy experience with stakeholders had been operating for a substantial period (over 15 years) in the field of migrant advocacy, and that this presented an avenue for legitimization (see Table 1). Additional review of the data revealed that the organizations that responded ‘No’ while having the same number of years in operations as above (i.e., 2 organizations), even though they offer services to migrants, they do not make these services the predominant objective of their organization. This, however, does not imply that they are incapable of contributing to policies within the migration field, as they have first-hand, on-the-ground experience dealing with vulnerable minorities. In tandem with these observations, it was found that the other organizations (those with under 9 years of operations), despite having significant encounters and grassroots experiences interacting with the migrant community, were never consulted by policymakers on migrant integration.

Even if involved in consultancy, the impact of CSOs on policy formulation can be relatively restrained, as explained by Interviewee 9CE:

we have a limited voice (…) a lot of times it is very superficial or cosmetic where they just want to say, all right, we invited NGOs. They do get information because they do need it but when it comes to actually drafting policy; this is what it’s going to be done. Sometimes it does go in the NGO favour, depends on the topic. But a lot of times it’s what the government wants to put out there.

The role of democratic life and the status quo within the realm of policy making seems to be restricted by ‘the position of power (…) we can share our concerns. We can put forward our position. At the end of the day, they are the ones that make decisions, and you can just hope for the best” (Interviewee 10CE). One interviewee also expressed concerns about the impartiality of those CSOs who consult with governmental stakeholders: ‘with NGOs when you look at where they originated or who is involved, they have very tight affiliations with government bodies … they benefit because they allocate the funds to them’. All things considered, this section created a pathway for the final thematic area as the compilations above highlighted the limited exposure of local organizations to the arena of policy formulation. It was against this backdrop that the interviewees were then given a hypothetical scenario in which they had to outline their expectations if given the opportunity to participate in a policy-making forum on migration.

Expectations, Recommendations, and Cross-CSO Collaboration

In terms of recommendations, the CSOs focused on the outdated legislative framework that currently exists and expressed that there is a need for reform. This, in their view, can be achieved if laws and policies are congruent with international standards. Furthermore, some organizations believe that migrants should be included in the reformation process, as Interviewee 2CE affirms: ‘I don’t think that they (migrants) are being included really in policy consideration. It has to come as a government-sanctioned policy and the idea would be inclusion for consideration of migrants’. This point was also reinforced by Interviewee 7CE who stated that ‘there are ways for people to actually gather data and information from us directly and dialogue. Include us in building the narrative that we need, include us in policy making, not only assume what we need or get the data brought to you and just see from your point of view, actually and actively engage us into the policy-making process’. Constructing such a narrative is critical because migration policy should be a living policy. It should be reviewed and, if necessary, revised as its implementation is constantly evaluated, as suggested by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (2009). This re-examination of policy should include all stakeholders.

The policy formation and implementation should also be homogenous as one interviewee reflects ‘what we experience now is just a whole lot of meetings. I’m unsure of the outcome. I think we need to streamline our process for how these things happen … one that balances group consultation and preparation work’ (Interviewee 2CE). With that being said, for homogeneity to be achievable a critical ingredient must be present, and that is implementation. As Interviewee 4NCE stated, ‘I would hate to sit down on a board, a committee, anything like that and then you know we work two years on this massive policy. We did all this research and spent all this time, spend the people’s money because it’s taxes that pays for these subcommittees and then for that not to be implemented’. In a similar manner, Interviewee 9CE hopes that the CSOs would have more impact on the policy than upon consultations:

if we (have) a committee, then we would be in charge of policy, advocating legislation guidelines, not just where they [political stakeholders] listen to us, but then they don’t hear anything or when they bring it up in Parliament, only about 5% of what we say. So, it would have to be a group that actually has the power to draft legislation and advocate for legislation and programming not just a focus group as most of them are.

At the end of the interviews, respondents were asked to think of ways they can unite to encourage policymakers to develop and implement a migrant policy. Several organizations verbalized the importance of being harmonious or consistent as Interviewee 5NCE states

I think before that, coming together even takes place, we as civil society need to be on the same page or have the same perspective about migrants. We don’t all have the same opinion when it comes to migrants. But for those of us who do, I think it’s an excellent idea to come together, to stick together, to brainstorm and to come up with ideas that could benefit the migrants.

For good measure, Interviewee 7CE gave a shrewd reality:

I understand that different civil societies and organizations work in different areas. Some might work directly in education skills, some might work in healthcare … others work on legal human rights, if we’re actually going to work alongside one another and actually actively work, we set clear objectives and see how we can remind political stakeholders to actually achieve the very end goal, which is building better policies and policy makers for migrants in general in Trinidad and Tobago.

Other interviewees remarked that in order to have a united front, CSOs should continue to share information and resources, and establish stronger sectoral partnerships: ‘From my experience we can collaborate by doing activities and events … to showcase what we do’ (Interviewee 3NCE). In addition to coordinated events, one interviewee also recommended that ‘we need to strengthen the referral pathways, ’cause while we have developed relationships with some organizations, places where services can be accessed, all the information is not available to everyone’ (Interviewee 2CE). In the same breath, an additional but different perspective was also offered by this same interviewee, who reflects that ‘maybe we are not reaching out enough because we are so caught up in the service provision and appealing to policymakers takes time. The process of changing policy takes time, and resources. It takes somebody sitting down and looking at a law and making suggestions’.

Considering these statements, it is important to note that consistency within the CSO sector is crucial not only because it challenges the status quo in local policy making but also because migration-related issues evolve over time. This evolution within the field should ignite an organization’s willpower to examine themselves with and for migrants to ensure that their actions remain strong, coherent and mindful of cross-cutting issues. Altogether, the findings of this research provided a perspicacious view of the realm that CSOs are duty-bound to operate within and conjointly, the next section of this paper aspires to do the same.

Discussion

The presented data in the findings section reflect on the developments within the field of migration not only in T&T but also wider Caribbean region. To recap, the findings have shown the challenges experienced by organizations and have laid out the first major stressor for CSOs – an outdated legislative framework which in their view is instrumental to migration integration.

The magnitude of this issue was illustrated in a recent judgement delivered by a local High Court. On 4th July 2023, Justice Frank Seepersad declared that the ‘obligations enumerated under the 1951 Refugee Convention and the principle of non-refoulement do not apply to Trinidad and Tobago as there has been no domestic incorporation’. As such, all immigrants are subjected to the provisions of the Immigration Act (Loop News 2023). Taking into account the above-mentioned verdict and the contributions made by the CSOs themselves in the findings, it is pertinent to now outline an assessment of Trinidad and Tobago’s 1976 Immigration Act.

Trinidad and Tobago’s Immigration Act, which governs the admission of persons into the country, not only omits in its terminology specific definitions, such as those who are deemed refugees, migrants or asylum seekers, but it also fails to guarantee any form of protection and rights to this group, and this also includes contingent rights for (un)accompanied children, and spouses who belong to migrants and or refugees. According to Pitcher and Bonnici (2021), a major flaw in the Immigration Act resides in its ‘over reliance on detention as a means of managing migration. Such methods have led to arbitrary confinement and even refoulement of persons who may have a legitimate need of protection’. It should be noted that similar sentiments of detention and deportation have been echoed by the interviewees as due process of the law is circumnavigated. For instance, Interviewee 1NCE noted that in a quest to assist ‘in finding appropriate legal aid, because so many of them experience the law being applied in a very arbitrary kind of fashion. I have had to deal with people being deported even though they may have had the government registration card’. In addition to this, Pitcher and Bonnici (2021) also specified that, in this instance, such actions are inconsistent with the Special Inquiry provisions outlined in the Immigration Act.

Further examination of this vital legislation revealed that the ‘Minister’, the person who is responsible for immigration (as identified by the act), has sole discretion to make decisions as he or she sees fit and ultimately determines the suitability of candidates entering through the nation’s borders. A notable missing feature of this Act, and our intent here is not to undermine the idea of sovereignty, is the incorporation of not only personnel from various ministries in the decision-making process but also input from civil society, which can be important and in due course may promote impartiality. This point also brings to light a discriminatory admission criterion of Trinidad and Tobago’s Immigration Act. According to Cernadas and Freier (2015), immigration legislation within the region embodies restrictive admission conditions that not only place limits on access to residency such as socioeconomic and occupational competence but also include ‘physical or mental handicaps, carrying infectious diseases … or even being considered “lazy” or “useless”’ (Republic of Trinidad and Tobago 1976, Immigration Act 1976, Section 8).

In the case of irregular migration, immigration policymaking in some territories such as Trinidad and Tobago, Jamacia and Guyana is stagnant as migratory systems and regimes are archaic, political will is unsatisfactory and measures to effectively manage massive, forced displacement equate to interim and improvised measures of assimilation. This can be illustrated by how some countries reacted to Dominicans after Hurricane Maria; Haitians fleeing continuous natural disasters; and the Venezuelan upheaval in this current study. Even in the case of regular migratory circumstances, there are instances where inconsistent application of the free mobility component exists within the CARICOM’s Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME). Notwithstanding this evidence, there are territories within Latin America and the Caribbean that have (since their independence) progressed legislatively to incorporate migrant protection into their domestic sphere. For instance, Belize, Dominican Republic, Argentina, Bolivia, and Uruguay all have favourable legislative and migratory systems that have supported humanitarian protection for a number of years and include input from various sectors (Cernadas & Freier 2015; Lacarte et al. 2023).

An example of this type of input is the progress of civil society in Uruguay’s current national framework. Diconca (2020) gives an exceptional description of the relationship between civil society and the state. In Uruguay, CSOs who are involved in migration are not only a part of an Advisory Council that informs and guides the National Migration Board (a state entity) on migratory issues, but they have collaborated on designing and monitoring public policies for the immigrant and emigrant community. To go a step further, Diconca (2020) explains that the very essence of Uruguay’s Migration Law #18250 of January 2008 enshrines civil society’s claims and reflects the influence that these non-state actors have and will continue to have. This is a notable example for CSOs in Trinidad and Tobago of the yielding power that resides in cross-collaboration – the absence of which is the third stressor identified in this study. Despite this stressor, there is avid willingness, as Interviewee 6CE indicates, ‘to support in any capacity the development of policies, procedures and legislation that contribute to the protection of the rights and well- being of people who have been forced to flee. These include refugees, returnees, stateless people, the internally displaced and asylum-seekers’.

In relation to the CSOs’ experiences with stakeholders, the findings revealed that most organizations (as indicated in Table 1 above) involved in this research were never consulted by government on policymaking. Even in situations where dialogue occurred, it is alleged that conversations lacked depth and follow-through. The absence of consultation transpired regardless of an organization’s years of operations and experience in dealing with migrants and other vulnerable minorities. Such an occurrence brought to light the idea of insider and outsider groups and questioned the legitimacy of some CSOs in Trinidad and Tobago. Considering the above circumstance, the idea of networking to promote norm entrepreneurship can illustrate the importance and impact of fostering relations that can possibly reach beyond the shores of Trinidad and Tobago.

To grasp the notion of networking in norm entrepreneurship, it is essential to understand the meaning and value of norms. Norms in international relations are universal codes of appropriate behaviour that are set by agents, states, and societal actors (Lindsay 2019). These ‘codes’ can be shared beliefs and values, and they provide cues that direct states to what kind of actions and identities are acceptable. Normative guidelines, however, are first fabricated at the national level as they rely on socialization and traditions that are built-in domestic institutions. In this capacity, networking in norm entrepreneurship can be witnessed when local CSOs come together, create similar belief systems or ideas and create a forum for the adoption or transmission of norms that could affect public opinion, influence the various arms of government, and contribute to migration governance. Ultimately, norms are then spread beyond their realms of conception (the domestic arena) and enter regional and international forums through diplomatic relations, negotiations, advocacy, and litigation (Lindsay 2019).

Nah (2016, p. 228) also proposes that CSOs can encourage states to adopt new norms towards migrants and refugees and this can occur irrespective of their status (whether they are insider or outsider groups). In this regard, CSOs should not be ‘easily dismissed as ‘outsiders’ who ‘interfere’ in the domestic affairs of a state’. Given this context, the example of the Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network (APRRN) illustrates how a formalized system of civil society agents engage in norm entrepreneurship. The APRRN is a regional group that was established in 2008, and to date comprises over 200 local civil society groups based in the Asia Pacific region, and more than 100 individuals (which includes academics, legal aid providers, universities, and CBOs). Choi (2022, p. 2527) echoes reports that since its emergence, Asiatic NGOs have pivoted from ‘service providers to primary advocates’ and their eminence has filled gaps in refugee protection. It is also noteworthy that this network operates in conditions where some states within the Asia Pacific have not acceded to international conventions relating to refugees, and others lack domestic legislative frameworks to facilitate migrant protection and assistance. For instance, within the entire Asia-Pacific region, only a handful of states are party to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol; they are South Korea, Japan, Timor- Leste, Cambodia, China, and the Philippines (Nah 2016; Choi 2022).

At present, there are no regional civil society networks in the Caribbean whose sole focus is on mixed migratory flows and refugee protection, let alone an association that does not rely on undue state intervention, intergovernmental organizations, and the media. In a comparable fashion, Interviewee 12CE identifies with this view:

If we have one opportunity, I would love to have everybody in the same basket and say okay, for all of us, we must decide. We can meet and discuss things for all of us and make suggestions and so on. One organization, one person and representation for the rest (…) to give different perspectives of that group because if we don’t unite like that, we’re not going to get in any big position.

The idea of a transnational advocacy network for migration in the Caribbean, like the APRRN, is an area worth exploration for CSOs not only in Trinidad and Tobago but also for their counterparts in the region. Trinidad and Tobago could be the first in creating such networking considering the proximity to and context of political crisis in Venezuela, resulting in significant inflow of migrants to this small island developing state. Such an initiative could influence an agent’s perception of migration as well as unify individuals and academics whose interest reside in this domain. Networking in this manner connects CSOs that are considered both ‘insider and outsider groups’, thus presenting a legitimate, vigorous force that can compel policy makers to embrace new norms towards migrants and refugees.

Conclusion

At the end of 2021, the UNHCR reported that over 85 million people have been forcibly displaced and within this aggregate figure resides a microcosm of Venezuelans who have fled their native land because of political, economic, and social instability (UNHCR Global Trends Report 2021). The ongoing migratory trends in the region have prompted local civil society actors to be involved in assimilation activities to manage the inflow of migrants, and whilst several organizations have progressed in areas such as consultancy and service provision, the contributions of others have not been acknowledged.

On account of the foregoing, the findings of this research allude to a stark reality that the time is ripe with opportunity for Trinidad and Tobago to consider migratory legislative reform as irregular patterns of migration continue to prevail as both the regional and global arena present constant vulnerabilities. This may be achieved if immigration policymaking and the rule of law synchronize to form a symbiotic relationship where not only the legitimate needs of the country are met but the rights of migrants and refugees are created, respected and made fair. Thoughts about future avenues of research are revitalized as this study provided a platform to now engage with policymakers in a similar structure. This will help to gain insight into their experience with CSOs and the trials encountered in the field of migration management in Trinidad and Tobago. Gaining an understanding of both ends of this spectrum may help to bridge gaps identified in this study and provide an opportunity for both actors to move in a direction that would benefit citizens and the nation’s vulnerable minorities.

References

Aasmaa, T. 2020, The role of civil society organisations in ensuring the integration of migrants and refugees - project summary report, European Economic and Social Committee, Brussels. https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/p3fg4v

Alvarado, G. 2022, ‘Venezuelans await word on status in Trinidad and Tobago’, Trinidad and Tobago Newsday, 13 January. https://newsday.co.tt/2022/01/13/venezuelans-await-word-on-status-in-trinidad-and-tobago/

Anatol, M., Kirton, R. M. & Nanan, N. 2013, Becoming an immigration magnet: Migrants’ profiles and the impact of migration on human development in Trinidad and Tobago, ACP Observatory on Migration, Brussels. https://publications.iom.int/books/becoming-immigration-magnet-migrants-profiles-and-impact-migration-human-development-trinidad

Banulescu-Bogdan, N. 2011, The role of civil society in EU migration policy: perspectives on the European Union’s engagement in its neighbourhood, Migration Policy Institute, Washington, DC. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/role-civil-society-eu-migration-policy-perspectives-european-unions-engagement-its

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) 2021, ‘Venezuela crisis: How the political situation escalated’, BBC News, 12 August. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-36319877

Bowen, G. A. 2013, ‘Caribbean civil society: Development role and policy implications’, Nonprofit Policy Forum, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1515/npf-2012-0013

Cadiz-Hadeed, A., Jattansingh, S. & Ramkissoon, C. 2020, An Advocacy Toolkit for Caribbean Civil Society Organisations, Caribbean Natural Resources Institute, Port of Spain. https://canari.org/civil-society-and-governance/an-advocacy-toolkit-for-caribbean-civil-society-organisations/

Caribbean Community (Free Movement of Skilled Persons) Act 1997 (Jamaica). https://laws.moj.gov.jm/library/statute/the-caribbean-community-free-movement-of-skilled-persons-act

Caribbean Development Bank 2017, ‘Caribbean policy reform threatened by lack of political will, implementation capacity’, 21 September. https://www.caribank.org/newsroom/news-and-events/caribbean-policy-reform-threatened-lack-political-will-implementation-capacity

Cernadas, P. C. & Freier, L. F. 2015, ‘Migration policies and policymaking in Latin America and the Caribbean: Lights and shadows in a region in transition’, In: Cantor, D. J., Freier, L. F. & Gauci, J.-P. (eds.), A Liberal Tide? Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy in Latin America, University of London Press, London, pp. 11–32.

Chaves-González, D. & Echevarría-Estrada, C. 2020, Venezuelan migrants and refugees in Latin America and the Caribbean: A regional profile, Migration Policy Institute. Washington, DC. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/venezuelans-latin-america-caribbean-regional-profile

Choi, W. G. 2022, ‘Becoming an advocate: Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network (APRRN) and the evolution of local NGOs in Asia’, Third World Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 10, pp. 2526–2543. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2022.2104245

DeWiel, B. 1997, ‘A conceptual history of civil society: From Greek beginnings to the end of Marx’, Past Imperfect, vol. 6, pp. 3-42. https://doi.org/10.21971/P7MK5N

Diconca, B. 2020, ‘Participation of civil society in public policies and programs related to migration in Uruguay’, In: Chiarello, L. M. (ed.), Public Policies on Migration in Latin America: The Cases of Ecuador, Uruguay and Venezuela, Scalabrini International Migration Network, New York, pp. 296–323. https://www.scalabriniani.org/c365-attualita/nuovi-volumi-simn-scalabriniani/

Ellis, R. E. 2017, ‘The collapse of Venezuela and its impact on the region’, Military Review, vol. 97 no. 4, pp. 22–33. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/July-August-2017/Ellis-Collapse-of-Venezuela

Grant, W. 1995, Pressure Groups, Politics and Democracy in Britain, Red Globe Press, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-15022-9

Grey, S. 2020, ‘Lack of refugee policy big issue for T&T govt’, Trinidad & Tobago Guardian, 27 November. https://www.guardian.co.tt/news/lack-of-refugee-policy-big-issue-for-tt-govt-6.2.1255944.89c9ad2255

Guest, G., Namey, E. & Chen, M. 2020, ‘A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research’, PloS ONE, vol. 15, no. 5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent, 2009, Policy on migration, Geneva. https://www.ifrc.org/document/migration-policy

International Organization for Migration 2020, DTM Trinidad and Tobago — Monitoring Venezuelan Citizens Presence, Round 2 (September 2019), Port of Spain. https://dtm.iom.int/reports/trinidad-and-tobago-%E2%80%94-monitoring-venezuelan-citizens-presence-round-2-september-2019

Jezard, A. 2018, Who and What is ‘Civil Society?’, World Economic Forum, Geneva. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/04/what-is-civil-society/

Johnson, R. B. & Christensen, L. 2019, Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Approaches, 7th edn, SAGE Publications, Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Lacarte, V., Amaral, J, Chaves-González, D., Sáiz, A. M. & Harris, J. 2023, Migration, Integration, and Diaspora Engagement in the Caribbean: A Policy Review, Inter-American Development Bank. https://doi.org/10.18235/0004769

Lewis, D. E. 1994, ‘Nongovernmental organizations and Caribbean development’, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 533, no. 1, pp. 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716294533001009

Lindsay, C. 2019, ‘Norm rejection: Why small states fail to secure special treatment in global trade politics’, Small States & Territories, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 105–124. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/45040

Loop News 2023, ‘T&T high court rules refugees can be deported’, 5 July. https://tt.loopnews.com/content/tt-high-court-rules-refugees-can-be-deported

Montoute, A. 2010, ‘Theorising democratic participation in development policy: The Caribbean case’, 11th Annual Conference: Turmoil and Turbulence in Small Developing States: Going Beyond Survival, Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies, Port of Spain. https://sta.uwi.edu/conferences/09/salises/papers.asp

Nah, A. M. 2016, ‘Networks and norm entrepreneurship amongst local civil society actors: Advancing refugee protection in the Asia Pacific region’, International Journal of Human Rights, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 223–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2016.1139333

Pitcher, D. & Bonnici, G. 2021, Immigration Detention in Trinidad and Tobago, International Detention Coalition, Melbourne. https://idcoalition.org/immigration-detention-in-trinidad-and-tobago/

R4V Inter-Agency Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela n.d., ‘Evolution of the Figures in the R4V 17 Countries’, https://www.r4v.info/en/refugeeandmigrants

Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, Ministry of Attorney General and Legal Affairs, 2016. Immigration Act 1976 (Trinidad and Tobago), https://agla.gov.tt/downloads/laws/18.01.pdf

Republic of Trinidad and Tobago 2019, Non-Profit Organisations Act 2019 (Trinidad and Tobago) https://www.ttparliament.org/publication/the-non-profit-organisations-act-2019/

Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, Parliament Joint Select Committee on Human Rights, Equality and Diversity 2020, Inquiry into the treatment of migrants with specific focus on rights to education, employment and protection from sexual exploitation, Eighteenth report of the Joint Select Committee on Human Rights, Equality and Diversity, Parliament of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, Port of Spain. https://www.ttparliament.org/committees/show/the-committee-on-human-rights-equality-and-diversity/reports/

Saldaña, J. 2021, The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 4th edn, SAGE Publications Ltd, London.

Sarantakos, S. 2017, Social Research, 4th edn, Red Globe Press, London.

Trinidad Express Newspapers 2022, ‘Registered Venezuelans get extension to stay in T&T: Safe for 2022’, 22 March. https://trinidadexpress.com/newsextra/registered-venezuelans-get-extension-to-stay-in-t-t-safe-for-2022/article_473f7646-aa15-11ec-be32-4b04113b31c1.html

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 2016, UNHCR submission for the Universal Periodic Review – Trinidad and Tobago – UPR 25th session (2016). https://www.refworld.org/docid/60ae44e59.html

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 2022, Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2021. https://www.unhcr.org/media/global-trends-report-2021

World Bank 2023, World Bank open data. https://data.worldbank.org