Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 16, No. 3

2024

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

Female Garment Workers in Bangladesh Facing Human Rights Violation; A Search to Find the Root Causes

Md. Basirulla1, Farhat Tasnim2,*, Md. Sultan Mahmud3

1 Varendra University, Rajshahi, Bangladesh, bosirullah213@gmail.com

2 University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi, Bangladesh, tasnim.farhat@ru.ac.bd

3 University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi, Bangladesh, smahmud@ru.ac.bd

Corresponding author: Farhat Tasnim, University of Rajshahi, Sayed Ismail Hossain Siraji Building Building, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi 6205, Bangladesh, tasnim.farhat@ru.ac.bd

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v16.i3.9089

Article History: Received 23/03/2024; Revised 06/10/2024; Accepted 16/10/2024; Published 19/12/2024

Citation: Basirulla, Md., Tasnim, F., Mahmud, Md. S. 2024. Female Garment Workers in Bangladesh Facing Human Rights Violation; A Search to Find the Root Causes. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16:3, 85–103. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v16.i3.9089

Abstract

Among the most important productive sectors of Bangladesh is the garment industry. The total contribution of the garment industries to the national foreign exchange earnings is 83%. Though the garment sector has created substantial employment for female workers, female workers face numerous human rights violations at the workplace including sexual harassment, forced labor, maltreatment of supervisors, maternity leave problems, safety problem, and health problem etc. This qualitative study gathered data from male and female garment workers, as well as from senior managers and owners, and experts from NGOs and from universities. This study revealed social-cultural, economic, structural and organizational causes behind human rights violations of female garment workers. Some of the causes are deficiency of education, fear of losing employment through complaining, lack of awareness and government oversight, weakness of the National Human Rights Commission and human rights organizations, unwillingness of owners to face the issue, poverty, and entrenched patriarchy.

Keywords

Human Rights; Human Rights Violation; Female Workers; Garment Industries; Bangladesh

Introduction

Women’s motivation to move forward has increased over time. Since women constitute almost half of the country’s total population, their participation in every field is equally necessary for the development of society and the state. In many cases, they have come a long way. But women are constantly facing various obstacles at work whether in a developing or a developed country. Women are not safe in most of the corporate organizations. Not only sexual harassment is considered unsafe, but sexual harassment hints, eve-teasing, and indecent remarks also create insecurity for women. Many keep themselves away from the workplace for fear of falling prey to such misconduct, and some remain silent out of fear of losing their job, facing shame from society, or losing their source of income. But these undesirable situations cannot be permanent. There are strict laws for the safety of women. However, implementation is doubtful. In other words, if one is completely faithful to the constitution and the law, in any case, there is no opportunity to treat women in a derogatory, discriminatory manner. Any initiative taken in the interest of women’s development is always supported by the constitution. Despite these laws, many women are still being humiliated and tortured in various ways.

Women’s rights are not a separate issue from human rights. Women’s rights and security are emphasized in every aspect of human rights. At the same time, there are certain rights for women that encourage them to live with their dignity and self-respect. Women’s rights are an issue that applies equally to women of all ages. Women workers in garment factories are being deprived of fundamental rights as well as human rights. In a previously published paper, we have briefly mentioned the types of violence that often take place on women laborers (Basirulla & Tasnim 2023). In this research paper, the researchers try to reveal the reasons behind such human rights violations. It is known to everyone that human rights of female garment workers are violated in Bangladesh. But no one can point out the main reasons for these violations, because there are not enough systematic studies on the causes of human rights violations against female garment workers. Most of the studies conducted so far are on the nature of human rights violations, gender discrimination, sexual harassment, globalization and macro implications of the growth of the garment industry in Bangladesh, growth trends of the apparel sector of Bangladesh, socio-economic and health conditions of garment workers and so on. The studies conducted by different researchers discussed many issues other than causes of human rights violation. In some research this problem has been addressed narrowly or partially. So, in this study, researchers focus on the factors behind human rights violation against female garments workers in Bangladesh. The paper first discusses the theoretical aspects of gender issues and human rights violations, then sets out the methodology of the study, and finally presents the findings of the study and concludes with a discussion.

Gender Issues and Human Rights Violation in Bangladesh

Human Rights are those basic standards without which people cannot live in dignity. The fundamental rights and freedoms that all humans are entitled to often include the right to life and liberty, freedom of thought and expression, and equality before the law. These rights come with birth and apply to people worldwide irrespective of their race, color, sex, language, political or other identity. To violate someone’s human rights is to treat that person as though they were not a human being. These are a few natural rights that cannot be denied. The state must promote and protect human rights. Everyone in a society should be able to live with dignity and have access to human rights. But in Bangladesh there are many places where human rights are being violated, for instance, at home, in the workplace, at the police station, and many more (Amnesty International 2022). Michelle Bachelet, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, visited Bangladesh in August 2022 to observe the human rights situation in this country. She expressed concerns and pointed out several sectors where human rights are violated. According to Bachelet, human rights violations include obstacles to freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, torture and other ill-treatment, extrajudicial executions, and enforced disappearances, violence against women and girls, workers’ rights, discrimination, and refugees’ and migrants’ rights (Amnesty International 2022). Ain o Salish Kendra (2024), a Bangladesh-based human rights organization, claims that 207 women died in 2023 of domestic violence in the country. Section 195 of the Bangladesh Labor Act (2006, amended 2013) outlaws numerous ‘unfair labor practices’. For example, no employer shall ‘dismiss, discharge, remove from employment, or threaten to dismiss, discharge, or injure or threaten to injure him/her in respect of his employment by reason that the worker is or proposes to become, or seeks to persuade any other person to become, a member or officer of a trade union’ (Human Rights Watch 2014). Women workers are deprived, exploited, and discriminated against in every formal or informal sector, such as garment factories, agriculture, stone quarrying, waste cleaning, waste segregation, and mobile vending, but mostly as domestic workers in urban areas (Sultana 2021; Islam & Bhuian 2019; Dey 2017; Alamgir & Cairns 2015; Khosla 2009; Hossain & Tisdell 2005). In addition to subjection to common problems such as recruitment without a written contract, low wages, prolonged working hours, lack of leave and leisure, absence of social security, denial of the right to collective bargaining, lack of safety measures and compensation for workplace injury, women workers are particularly vulnerable to discrimination, sexual harassment and insensitive treatment during maternity periods (Akter, Teicher, & Alam 2024; Haque, Sarker, & Rahman 2019; Haque et al. 2020; Islam & Bhuian 2019; Akhter, Rutherford, & Chu 2019; Begum et al. 2010).

Under its constitutional provisions and applicable ILO instruments, Bangladesh is required to undertake measures to protect the interests of the workers. But apart from concluding a decent work program with the ILO focusing on a safe and clean working environment and framing a policy document for the protection of the garment workers, its responses are poor. It has a few laws of general application, including the Labor Welfare Foundation Act (2006), providing for the creating of a welfare fund for all sectors, and Legal Aid Act (2000), and Policy (2013), supporting access to justice, including for poor workers (Syed 2020; Islam & Al Amin, 2016). Its detailed documents include a promising policy requiring a written contract, pre-fixed salary, health care, compensation, education, and maternity leave. It has, however, remained largely inoperative due partly to the imprecise allocation of implementation responsibilities and the lack of accountability of the implementing agencies (Islam & Bhuian 2019). Other laws and policies cover small areas or less important issues. There is also a lack of gender-sensitive law and social security welfare legislation for the garments sector. According to a non-governmental organization, 80% of female workers in garment factories in Bangladesh are sexually harassed in their workplace. While 25% of the respondents to the survey claimed that all female garment workers are victims of sexual harassment, 62% of respondents indicated they were aware of such behavior occurring in the workplace. The report further states that 54% of women workers do not open their mouths on this issue out of fear. Talking about this was disliked by 51% of female employees. Direct physical touch with managers was a perk that 17% of female employees had received (ActionAid 2019). This report provides an overall idea about the nature of human rights violations that are happening to women garment workers in Bangladesh. There are some other studies that also help to understand the actual conditions of the garment industry beset with numerous complaints. A few of such complaints are sexual harassment, health problem, no freedom of association, lack of childcare room, lack of toilets, exploitation of labor by low wage and over work, large-scale social insecurity of women workers, wide-scale labor lawlessness among the workers, gender-discriminated working conditions and so on (Basirulla & Tasnim 2023; Jalava 2015). The present study was conducted to understand the reasons behind such human rights violations. We have identified different social, structural and administrative reasons behind such violations. Among those reasons, some are apparent while some are hidden behind the cultural and organizational setting. The following section provides the methodology used for the study.

Research Method

The research was carried out to identify the existing reasons behind human rights violations on female garment workers in Bangladesh. This is an empirical study. Although the research initially aimed to combine both quantitative and qualitative methods, constraints in achieving a representative sample size have led us to focus primarily on qualitative methods. In this study, a qualitative method was used to get a reasonably accurate picture of the human rights situation inside the garment factories. Secondary data were collected through literature and report reviews from various sources such as relevant books, journals, reports, articles, official statistics, daily newspapers, thesis/dissertations, laws, regulations available both online and as hard copy. Further, NGO leaders, human rights activists and scholars were interviewed as key informants (Table 1).

The research was carried out in two garment factories located in the Mirpur area of Dhaka1. One large factory with a total population of 1641 workers and one smaller factory with approximately 380-400 workers were selected. From these factories, a total of 70 workers were interviewed using a structured questionnaire). Focus group discussions were conducted with female workers based on the agenda that women garment workers did not feel free to discuss topics such as the working environment, treatment by their bosses, sexual harassment, and other related issues within the factory premises. The period of data collection spanned from 10 January to 10 February 2022. A further 10 owners and senior managers, five from each factory, were interviewed using open-ended questions. While our initial plan was to select a larger sample based on Cochran’s formula (Cochran 1977, p. 413) (suggesting 312 respondents for Factory One and 192 for Factory Two at a 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error), practical constraints such as restricted access, time and budget limitations led us to purposively select 35 respondents from each factory for interview. The fear and reluctant attitude of the women factory workers to participate in the survey was a big obstacle to their participation. Respondents were selected based on random availability during the data collection period from the factory premises (Table 1).

Prominent human rights experts (KII1) and NGO leaders (KII2) were also selected purposively, based on their expertise. Researchers interviewed them for further validation. They may be considered key informants. Therefore, in order to examine the complex experiences of garment workers and the viewpoints of other stakeholders, the study mainly depends on qualitative insights from the interviews and discussions from five categories of the respondents. (See Table 1).

Factors behind Human Rights Violations against Female Garment Workers

The issue of women’s oppression has been the most pervasive theme of the women’s liberation movement in Bangladesh. The present condition of women’s oppression is a matter of anxiety for every conscious person and for all human rights organizations working in our country. Statistically, the percentage of violence is increasing at an alarming rate, and forms of oppression are arriving at a devastating stage. Women’s oppression or violence against women is not a new theme or phenomenon but it has been considered as a serious problem for decades. Especially in the workplace, female workers are deprived of their actual rights and they are facing several violations of these rights. The present researchers in another study (Basirulla & Tasnim 2023) identified nine distinct human rights violations in against women garments workers. They are forced labor, sexual harassment, inadequate supervision, lack of healthcare and sanitation, insecure environment, lack of proper maternal leave, child labor, job insecurity and infringement on freedom of association. The present study tries to explore the genuine answers to why female workers are facing violations in garment industries; what are the key reasons for such violations? Human rights violations refer to the infringement of human rights through activities that show disrespect or disregard for individuals (Jalava 2015). In Bangladesh there are many reasons to violate human rights, including lack of education, lack of awareness, patriarchy, weakness of government oversight, poverty, and so on. The data that have been gathered through key informants KII1 and KII2, focus group discussions and questionnaires, provide a quite clear picture of the factors behind human rights violations at these garment factories in Bangladesh with special reference to female workers. The following sections will now analyze the factors one by one.

Lack of Proper Education

One of the reasons behind the violations of human rights of women workers in Bangladesh is the low level of women’s education. This study, taking into account the technical qualification, education and knowledge need and the social background of the women garment workers, considers the higher secondary level education (up to twelve grade) as a standard level of education for them. Girls in Bangladesh are still lagging behind men in education. Due to gender discrimination, a girl gets fewer educational opportunities than the male members of the family. Again, parents think that their sons will take over their family responsibilities in old age, so they are less interested in educating the girl child whom they have to marry off. Women are the half of the total population of Bangladesh. These women are contributing to the overall development of our social-economic condition. Despite this fact, the so called male dominated society still has reluctance regarding female education. In addition to this, early marriage, family restrictions, child rearing and so on are actively working as the main barriers on the way to female education. The main reasons behind these barriers are poverty, illiteracy, rapid growth of population, social prejudice among others. The national literacy rate in urban areas is 81.28% while in rural areas it is 71.56%. But noticeable is that the literacy rate of male (76.56%) is higher than female (72.82%) (Star Digital Report 2022). This naturally keeps the women in a lower status than the men in the society (Rahman & Rahman 2017). If half of the population is ignorant, no nation will be able to develop. Low rate of education among the female population is considered as a reason behind social unawareness of the women. These women are unaware of their rights too (Mannan & Marri 2020).

The Bangladesh government has ambitious policies for girls’ education which increased female literacy rate from 39% to 72.82%. Though Bangladesh has progressed its educational ratio, there are some factors that still cause some barriers in rural Bangladesh. Poverty, religious beliefs, ethnic identity, taboos, cultural deprivation, poor access, cultural changes and so on are the sociocultural factors that are responsible for the obstacles for female education (Mahbub 2022).

In garments factories, most of the female garment workers having less education have migrated from rural areas since they have no other alternative means of income and resources in their villages. Throughout the country, 70% of female garment workers are from rural areas (Prothom Alo 2021). The rate of education among these female garments workers is low. As a result, they are lagging behind in the use of technology and their participation in the garment industry is also decreasing (Akter 2022). ‘A Survey Report on the Garment Workers of Bangladesh 2020’ stated that 13.1% of RMG employees have completed high school, 35.1% have attended junior school, and 4.3% have no formal education (Haque & Bari 2021). Another study also found that 52.22% women workers have completed their primary education, 42.22% have completed their secondary education and only 5.56% have completed their higher secondary education (Alam et al. 2017, p. 53). These female workers are not aware of their rights because they are not educated. So, they are constantly being harassed in the workplace and they do not have the courage to protest back and do not know the mechanism to convey their complaints. Rather they accept the mistreatments and violation of their human rights as taken for granted.

Surma (a pseudonym for one of the respondents told the researchers: ‘

When I was nine years old my father died by an accident, we are four brothers and sisters. I am the first child of my parents. After my father’s death we had no alternative source of income. I had to go out to work with my mother for the survival of the family. My mother and I used to work all day. I was not able to complete my minimum primary education level that is even 5th grade because of my father’s death. People mocked me and called me illiterate, stupid but I had nothing to do. They did not try to understand why I was uneducated or stupid? Why I could not go to school? I was very young then. So sometimes I had to endure a lot of torture if something went wrong at work. After working like this in the village for two years, my mother sent me to Dhaka with someone to work in garments. I still remember the day when I left my family and came to Dhaka which was heartbreaking both for my family and me. Since then, I have been working in this garment. Now I am 18 years old. Even though I came to Dhaka to escape the oppression of the village, the situation is the same here. I receive a small amount of salary though I have a long experience. This is because of my poor educational background. In fact, it is very difficult for the poor and uneducated to survive in this world which others will never understand.

There are many other female workers who are deprived of their basic rights of education like Surma.

Another study found that at the garments sectors 66% female workers had completed their primary education, whereas secondary level percentage was 34%, and only 0-2% female workers completed their higher education (Akter 2007). Now let us focus on our survey data:

| Class | Percent |

|---|---|

| 1-5 | 48 |

| 6-8 | 38 |

| 9-10 | 3 |

| 11-12 | 10 |

| Total | 100 |

Out of 60 female workers of the two factories under study, only 10% had passed higher secondary and 48.3% did not cross the 5th grade. Almost 40% of the female workers had completed 6-8 years of schooling and only 3% of them have studied up to class 9-10 (Table 2). When we interviewed human rights activists, prominent researchers, scholars, professionals and officials from various human rights NGOs, they also agreed about the low or no education of the female garment workers as a cause for the human rights violation upon them.

Lack of Awareness

No human being can protect his/her rights without being aware of his/her rights. Awareness serves as an important measure in all cases. A garment worker needs to know about women’s rights. The women workers have a lack of knowledge about the labor laws related to working conditions of garment workers at national and global level. The study reveals that there was a gender difference in knowledge about the labor laws. There are many factors influencing the respondents’ awareness of labor laws such as training, level of education, law consciousness and work experience. The factory management usually opposed the formation of a trade union. Most of the female workers have no knowledge about the trade union activities. Moreover, because of the fear of being dismissed, women workers do not think about it. Lack of awareness of labor rights make their position more vulnerable and they have no bargaining power to regulate the terms and conditions of employment such as wages, overtime pay, working hour, training, violation of rules, promotion, different kinds of leave including maternity leave and so on.

| Awareness of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights | Are you aware of women’s rights or laws in the workplace? | |

|---|---|---|

| Answer | Percent | Percent |

| Yes | 3.3 | 5 |

| No | 96.7 | 80 |

| No comments | 00 | 15 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

It is clear from Table 3 that female workers do not know what their rights are. Only 3% workers had known about their human rights or other women’s related rights; this scenery was despondent to the researchers. Between 80 and 96.7% of female respondents said they were unaware of their legal rights. When the researchers wanted to know about the human rights from the workers, some of them looked like they were hearing this for the first time. They are neither educated nor aware which is why they do not even realize that their human rights are being violated. Human rights advocates, well-known researchers, academics, professionals, and representatives from several human rights NGOs all agreed that women employed in the garment industry are less aware of their rights.

Owners’ Unwillingness to Acknowledge Violations

Under labor law, every office is supposed to have a ‘Sexual Harassment and Obscenity’ complaint box for the protection of women, but most offices do not have such a box. Moreover, in the offices where such a box does exist, there are no instructions on how to lodge a complaint in the complaint box, with whom to lodge a complaint, what action will be taken after the complaint, and so on. On the other hand, following the directions of the High Court, every organization should have a ‘Sexual Harassment Complaints Committee’ and most of the members of the committee should be women. However, according to Mizanur Rahman, former chairman of the National Human Rights Commission, this directive of the High Court also has no practical application. In terms of bonuses, salaries (52.22%), working nights, promotions (42.22%), overtime (5.56%), and other matters, 82.22% of female employees reported experiencing gender discrimination by the owners according to the study conducted by Alam et al. (2017, p. 53). But from the constitution of Bangladesh, we perceive that all are equal before law and every citizen has right to enjoy their rights without any discrimination in terms of age, sex, race or color (The Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh 1972, art. 27 & 28). The garments owners are surprisingly silent on this issue. Amazingly, they have no worries about the work environment for women, no initiative, and no goodwill. Far from installing the complaint box, many offices do not even have separate washrooms for women. Even if there is a washroom, there is no rubbish bin. One of the fundamental needs of women, sanitary napkins, are not provided by the garments factory. Apart from sanitary napkins, ladies’ toilets are not well secured. Several female respondents have complained that they feel threatened in terms of dignity while using the toilet (MacArthur 2023). Garments industries hardly follow the law on maternity leave, rather women workers who go on maternity leave are laid off without notice. According to the BBC, one of the main reasons for the declining participation of female workers in garment factories is the reluctance of garments owners to provide appropriate working conditions for women. They feel that male workers are more skilled and energetic than female workers due to which they can work longer hours on the garments (Akter 2022). They also feel that male workers can be more productive than females and they can increase ratio of profit that actually is the end of the owners. The same type of situation has been revealed in another study conducted by the Bangladesh Mahila Parishad (2016).

However, garments owners do not agree with this picture; they think that 98% of the workers working in garments are female, and there is no reason for them to feel unsafe there. Moreover, the owners claimed that officials always supervise the factories (Lehmann 2014). The only goal of garment owners is to make profit (Sikdar & Sarkar 2014, pp. 173-179). Taking advantage of the poverty of garment workers, the garment authorities force them to do extra work. Asma (not her real name) a female worker of the larger garment factory said:

‘The owner of my garment does not come every day and I cannot see him at all. He is the owner of a number of garments factories and also related to politics. That is why he is busy otherwise’.

During the data collection period, the owner of that larger factory was not present either. In the other factory, that was comparatively smaller, the owner was present and cooperative with the researchers. However, the overall environment of this factory was not satisfactory. This study also found that the workers were not paid on time. According to Labor Rights Law section 121 and UDHR the salary of the laborer must be paid within the first week of every month. But the owners never distributed the salary on time. In the first week of a month, 38.89% of workers receive their salary, followed by 50.55% in the second week and 10.56% in the third (Alam et al. 2017, p. 53).

| Are you satisfied with your factory’s current facilities? | Are you angry with the behavior of your superior? | Are your superiors sympathetic to you? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Answer | Percent | Percent | Percent |

| Yes | 40 | 46 | 38 |

| No | 25 | 14 | 12 |

| No Comments | 35 | 40 | 50 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

In Table 4, an attempt has been made to present the data on the relationship between the garment authorities and the workers. It appeared that a large section of the workers (46%) was not satisfied with the behavior of the authorities, and they felt that the factory owners were not sympathetic (38%) towards them. The female employees felt intimidated to divulge information about the real circumstances, which is why 30%–50% of them chose not to reply.

| If you are a victim of any kind of harassment at work, do the higher authorities take any action in this regard? | Does your garment department operate in accordance with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights | Do your garment owners bother about child labor? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Answer | Percent | Percent | Percent |

| Yes | 44 | 10 | 28 |

| No | 22 | 50 | 51 |

| No Comments | 34 | 40 | 21 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

The researcher wanted to know from the women workers whether the higher authority took any action if they were subjected to harassment in the factory. More than 40% (44%) of them answered in the affirmative but 22% outright denied (Table 5). Many women workers did not give their opinions on this issue. During the garment factory visits, the researchers found a few child workers. So, they wanted to know from the workers whether the garment department bothered about child labor. The researchers were surprised to find that 51% of the workers said that the authorities did not care about child labor. Not only that, according to the workers, the garment authorities are not aware of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and do not comply with it. Human rights advocates, well-known researchers, academics, professionals, male and female garments workers and representatives from several human rights NGOs all agreed that garments owners are less aware about human rights and the rights of women workers.

Deficiency of Government Oversight and Loopholes in the Labor Law

The Government and the employer play a major role in implementing the labor law. These include the issuing of appointment letters, observance of prescribed working hours, granting of leave, payment of wages, ensuring occupational health and safety, accidental compensation, provision of legal compensation and service benefits at the end of employment, prevention of harassment in the workplace and provide maternity leave and benefits to women workers. The main reasons behind the non-implementation of these conditions are the reluctance of the concerned implementer, the employer, and the weakness of the concerned government oversight body. The supervisory body to oversee the implementation of the labor law is the Department of Inspection of Factories and Establishments of the Government. Besides, trade unions of the concerned organization or factory also have roles to play. However, none of these institutions are fulfilling their responsibilities properly in the garment sector, and as a result women garment workers are constantly facing human rights violation (Prothom Alo 2021).

After the collapse of the Rana Plaza building with six garment factories in Savar on April 24, 2013, one of the worst massacres in the history of the garment industry in Bangladesh, there was a storm of discussions at home and abroad about the conditions, safety, quality of life, and trade union rights of Bangladeshi workers, especially the 4 million garment workers. A resolution of the European Union Parliament criticized the failure to implement various laws in Bangladesh, including workplace safety, fair wages and benefits, and labor laws for garment workers (European Parliament 2015). The Labor Act (2006) recognized the trade union rights of garment workers. The 1926, 1975, & 1979 laws also gave the right to form trade unions. Therefore, there is no doubt about giving garment workers the right to form new trade unions through the Labor Amendment Act (2013). In the Labor Act (2006), there was no provision for prior permission of employers to form trade unions. But in the Labor Amendment Act (2013), provision has been made to get the prior permission of the employers. Notable among the limitations of the existing labor law are workers’ wages, contradictory provisions on maternity leave and benefits, discriminatory provisions including maternity benefits and inconsistencies between different sections and chapters of the law on the same subject. In the case of women workers, more explicit provisions are needed for how the leave and benefits, including maternity leave, will be determined [Labor Amendment Act 2013, Sections 2(34), 46].

The 2018 amendment added that if a woman worker had an abortion or miscarriage before the scheduled maternity leave, she would not receive maternity benefits. The amended section states, ‘However, if she needs leave for health reasons, she may enjoy it’ (Article 48). But the provision does not say whether the leave will be paid or unpaid. In other words, in the private sector (according to the provisions of the labor law), maternity leave is 16 (sixteen) weeks and 24 weeks (six months) for government employees. Since these are workers in the same country, the two provisions are discriminatory and contrary to Articles 27 and 28 of the Constitution. In case of maternity leave, some more facilities, including hospital and medical expenses, need to be added.

Another important point is that there is no separate provision in the labor law regarding women’s employment and about their working conditions. The directive given by the High Court Division in 2009 (in the judgment of a writ petition) with clear provisions to prevent and remedy sexual harassment of women in the workplace has not been visibly implemented for a long time. There is no separate law or separate chapter or section of the existing labor law. There is a need to introduce universal pensions for private-sector employees. Though Bangladesh started the universal pension scheme in August 2023, questions are raised about its effectiveness. Notable people could not agree with this initiative of the government, because it is not sure how long the government can sustain this system and how much benefit the people will get, especially the working class (The Business Standard 2023). However, a pension scheme has become essential for the social security of the garment workers. In the present situation, the service rules of the two garments factories surveyed do not provide any employment benefit to the workers in case of retirement or for any other type of employment termination. For example, if a worker retires after giving service to the factory for 20 to 22 years, he/she will not receive any benefit or compensation from the authority There are many other such weaknesses in the labor law of Bangladesh, due to which women workers are not able to enjoy their basic rights. Human rights advocates, prominent researchers, academics, professionals, male and female garment workers, and representatives from various human rights NGOs all concurred on the lack of government oversight and the shortcomings in labor laws.

Weaknesses of the National Human Rights Commission

Many women garment workers need to learn about the existence of the National Human Rights Organization in Bangladesh. When researchers asked the respondents about the Human Rights Commission, they came to know that most of them had never heard of the name before. The main reason behind this situation is the weakness of the Commission itself. In this regard, the Assistant Director of the National Human Rights Commission Mohammad Azahar Hossain (2022) said, ‘As the National Human Rights Commission is a national organization, its scope of work is wide, but it can be said that there is no manpower compared to that. Nevertheless, the commission continues to conduct its activities.’ Mizanur Rahman, former chairman of the National Human Rights Commission also confirmed that the lack of manpower is the reason behind the weak performance of the commission. Moreover, female workers do not come to the commission with any complaints about their problems. He claims that when he was the head of the commission, the commission took some steps to make the garment workers aware of institutions where they can go with problems that are related to human rights violations. He also said that unless the government wishes, the commission can hardly act (Rahman 2022). The women workers who took part in this study have also been found to be unaware about such commission.

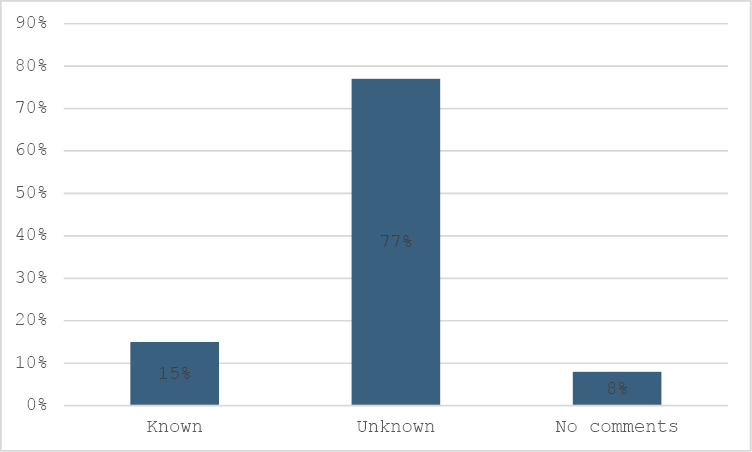

Figure 1. Workers’ Knowledge about National Human Rights Commission

According to Figure 1, 77% of the women garment workers said they did not know about Bangladesh’s National Human Rights Commission, which is very disappointing. Only 15% of the workers said that they heard the name of the commission but they had no knowledge about the activities of this organization. Some of them said they have very good knowledge about the commission’s activities but they were a small minority. On the other hand, 8 % of the female workers did not want to give their opinion on the issue. The possibility is that they did not have any idea what the commission is about. Human rights advocates, leading researchers, academics, professionals, both male and female garment workers, and representatives from various human rights NGOs all agreed on the weaknesses of the national human rights commission.

Weakness of Human Rights NGOs

There is not yet any definite and reliable list of human rights NGOs (Non-governmental Organization) in Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, there are over 2638 NGOs, registered under the Bureau of NGO Affairs, many of which focus on human rights, social welfare, and development (NGO Affairs Bureau 2024). There are many such human rights NGOs in Bangladesh that remain idle. Some do not even have the basic organizational requirements like organogram, list of personnel, objectives and the proper license to operate. Such so called organizations which are bound to protect the rights of women are not likely to succeed. All these human rights NGOs work just for money though these are non-profit organizations and no money transaction is allowed. A report on Jamuna Television (a private channel in Bangladesh) made this point clearly. Jamuna Television’s 360 team produced a special report titled ‘Human Rights Services or Business’. Through this report, the irregularities of some well-known and valuable human rights NGOs in Bangladesh came to light. These NGOs included Bangladesh Legal Aid Center Foundation, Bangladesh Human Rights Commission, Human Rights and Environmental Journalists Society, Women and Child Rights Forum, Bangladesh Human Rights Implementation Council, and so on. These organizations work for money, and in most cases, they were found to resort to fraud. These organizations take money promising to provide legal assistance to people. If the clients give money, they get membership of the organization, and (the NGOs) take larger sums of money from clients, if they promise to bring help from abroad. However, actually the responsibility of a human rights organization is to work for the rights of helpless person, be it against a large organization or against the government (Jamuna TV 2018). Many garment workers go to these organizations with their various grievances for redress, but they have to face more harassment, and this is nothing but a waste of money and a waste of time. Rahman (2022) said that he had received many such complaints during his tenure as the chairman of the Human Rights Commission but he could not take any action as he did not get any green light from the government. In his words, ‘The government should be more aware of such facts so that the common man does not have to suffer. Victims come to these NGOs with high hopes for realizing their fair share. When the government authorities who are assigned to conserve the right of the working people-- the Ministry of Labor Employment-- does not hesitate to refrain from their duty these helpless people become even more unprotected.’ This means that the behavior of structures and institutions that are to advocate and negotiate to ensure labor rights and stop human right violation of women workers have turned into causes behind such violations.

Fear of Losing Job

A large proportion of the working women belong to the lower middle class, and so they are poor. Women who come to work out of necessity hardly complain or protest out of fear of losing their jobs, even though they face injustice and maltreatment. In the midst of uncertainty of losing a job and not getting another job later, a female worker facing sexual harassment or violence, continues to work helplessly or is forced to quit her job. Although women workers in factories are victims of various forms of harassment, they remain silent out of fear, which is one of the reasons for continuation of human rights violations. According to Mahila Parishad’s research (2016), 76% of the female workers felt that they did not have financial security. They feared that they might lose their jobs any time.

On the other hand, despite the fact that the new minimum wage has been implemented according to 100% of the owners, about 40% of the women workers have said that they have not received the minimum wage. However, workers’ dissatisfaction with wages is less than before now. When it came to their pay, two thirds of the female employees were content (Mahila Parishad 2016). The Bangladesh Mahila Parishad conducted research on the working environment of female workers in garment factories. They found that 30% of these female workers suffer from insecurity in their workplaces due to a lack of job safety (Mahila Parishad 2016; Kabir, Maple, & Usher 2021). The present study found that 74% of female workers feared losing their jobs. Some did not even want to give real information about their factory and condition.

Poverty

Poverty is a terrible curse. This disrupts the normal life of the people. It brings frustration, anger, chaos in the life of the individual. In Bangladesh poverty is not only a problem, it is also the cause of many more problems. Poverty acts as an obstacle in the way of development of Bangladesh. Now GDP per capita income in this country is US$2457.9 (World Bank 2023). Most of the women garment workers are members of the rural poor. The Corona virus left a huge impact on the economy of Bangladesh as the following Table shows.

| Month & Year | Poverty Rate of Bangladesh |

|---|---|

| December, 2019 | 19% |

| January, 2021 | 42% |

| September, 2021 | 25% |

| June, 2022 | 18.54% |

Prior to Corona virus, at the end of 2019, the poverty rate in Bangladesh was 20.5% (Ministry of Finance 2022) but due to Corona, it increased to 42% in January 2021 (Prothom Alo 2021). The Corona pandemic ended but the poverty rate in Bangladesh remains 18.7% (Asian Development Bank 2024). Nazrul Islam, a professor of the University of Dhaka, said, poverty pushes women workers towards human rights violations2. Women garments factory workers continue to bear the oppression imposed on them due to poverty (Rahman 2022, January). The poverty rate of Bangladesh was at 18.54 % (Financial Express 2022) while it was passing an economic crisis but now the rate is 5.1% (Daily Star 2024). Inflation is increasing and the price of daily commodities has been rising every day, leaving no room for people to buy them in required quantities.

Currently (2024), the per capita income of this country is US$2,650 (International Monetary Fund 2024), but the economic condition of most of the people in this country is poor. Anjuman Ara (not her real name) a female garment worker who lives in Mirpur area said,

I have four daughters, the eldest daughter is 15 years old. When my eldest daughter was born, I wanted to educate her. I had so many dreams when I gave birth to each of my daughters. I wanted to educate them and make them conscious citizens and good persons. But education is out of reach for the ill-fated poor people like us! Now my elder daughter works with me in the factory because I have not been able to educate her up to the level of my desire.

In garment factories most of the female workers have come from poverty ridden backgrounds, leaving them unaware about their rights and the means to protect their rights. They work in the factory to support their family financially and continue to suffer from violations without raising any voice.

Patriarchy

Traditionally, Bangladeshi societies are patriarchal in nature (Rahman & Rahman 2017). And because of this, the women of this country easily fall victims to mis-treatment. In a patriarchal society, a man always has all the power. And women are inherently subordinate to men. Men consider it their right to control women. As a result, women easily lose their independence to men. Under such circumstances, knowingly or unknowingly, men torture women (Rahman & Rahman 2017). The traditional male dominating ideology is thus deeply rooted in the ‘deep structure’ of the factory which plays a vital role in reflecting perception on different gender roles played by men and women and their unequal capacity, creating gender unequal outcomes. This negatively affects women’s working conditions in the garment factory. The deep structure of the organization means the collection of values, history, culture and practices that form the unquestioned ‘normal way’ of working in organizations. The elements hidden in the deep structure are the critical determinants of core organizational processes such as decision-making, allocation of power, use of worker’s time, rewards and incentives and measurement of success in the gender-based organizations (Akter 2007).

In the present study, it was found that because of patriarchal attitudes within the garment factories, jobs were allocated largely on the basis of sex. Women were apparently machine operators and helpers in the sewing section. By contrast, men were non-operators, working either as cutting masters, helpers in the cutting section, or as iron men in the finishing section. The researchers found that garments owners or senior staff believed that males were stronger to do any work than females related to the garments. That is why some sectors are fixed for male, such as iron man, cutting master, helper and so on. In our selected factories, we found every supervisor is male and they were directing all the workers including female workers. It is not a fair scene for the female workers because not a single supervisor was a female.

Marri (not her real name), a garment female worker told the researchers:

I am 30 years old and have worked in the garment sector for 10 years. During this long time, I worked in many factories, and could not work for long in any of them due to maltreatment of the supervisors. In Garments most of the supervisors are male so they always try to harass the women employees and I was one of them. This reason is known to everyone, but no one can see! I am a single mother now. I have a baby girl who is 6 years old. I married one of my colleagues 8 years ago with high hopes but it didn’t take long for those hopes to turn into disappointment. A man cannot understand how helpless a woman is in a patriarchal society. I saw the real face of that man after marriage. He quit his job soon after we got married, on the pretext that he would work in a better factory with better wages but that was not true at all. He didn’t work anymore during our family life, I used to bear all the expenses of the family but I didn’t have any say. After taking money from me, my husband used to get drunk and return home late at night. I was subjected to inhuman torture when I forbade him to take drugs, the imprint of which is still present in my body. Even in this situation I wanted to continue the family because I was pregnant with my daughter. But he divorced me when my daughter was born. He had an affair with another girl while he was in the marriage with me and at one point married her without my permission. Women are neglected not only in the family but in all spheres. As you can see, most of the people who work in our factory are women workers but the supervisors are all men and even if they torture us in various ways, there is no one to see or talk about such offences.

Lack of Strong Trade Union in the Garments Sector

Most of the labor laws in Bangladesh are gender neutral. The factory management opposed the formation of a trade union. Female workers are hardly aware of such system. Moreover, out of fear of being dismissed, the female workers did not even think about it (Zohir & Paul-Majumder 1996). Though the garment workers are covered by labor laws, they did not get protection due to inadequate implementation and lack of awareness of the labor laws. No formal appointment letters stating the terms and conditions of services are issued for the workers. As a result, they can be fired any time arbitrarily by the employers without getting any protection and compensation (Akter 2007). In January 2014, Human Rights Watch reported that some union leaders tried to build up a trade union at a garment factory in Dhaka but in doing so they were brutally assaulted and their attempts led to scores of workers being fired (Human Rights Watch 2014). A pregnant union leader was beaten, forced to work at night, not paid her due wages she owed and finally was fired, only because she would not back down on unionizing (Jalava 2015). Those who form associations in garment factories and speak or agitate about workers’ wages and demand often end up in jail. These incidents are examples of dozens of cases in which union leaders have been threatened, attacked or fired for their legally entitled rights (Human Rights Watch 2014). That is why only 138 trade unions were formed in 30 years from 1983 to 2012.

However, the situation changed after the collapse of Rana Plaza. Under international pressure, trade unions were registered one after another. After the Rana Plaza tragedy hundreds of trade unions are registered every year, but most of them exist only on paper (Prothom Alo 2021). This means that though they are officially registered with the appropriate authorities, their activities are hardly felt. On November 4, 2020, 533 workers of a garment factory in Tongi, Gazipur applied to the Divisional Labor Directorate of Dhaka for union registration. On 3 January 2021, the department rejected the application as false and bogus. When the application process for re-registration began, the factory authorities sacked 20 people including the proposed union president and general secretary on January 7, 2021. The incident did not end here. Out of the 20 people who were fired, 6 joined a nearby factory on January 17. But they lost their jobs after 13 days, because a list with photos of 20 members of the proposed union was sent from the previous factory, leading the authorities of the second factory to say, ‘We cannot give you the job’ (Prothom Alo 2021).

During field work, key informants have also confirmed the anti-trade union mentality of the garment authorities. Rahman (2022) said that one of the key reasons for the violation of women’s human rights in garment factories is the absence of strong trade union. He also expressed concern that while there is no strong organization for the workers, the owners’ organizations are very strong, for instance Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association, Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association and so on. The two garment factories under study do not have any trade unions. The larger factory has an organization called the Peace Committee which is nominal. About this organization, a senior official of the factory said:

This organization is kept only to show off the foreign buyers. The main objective of the authority is to make the foreign buyers understand that there is an organization for the workers in this factory which works for their welfare. This organization was formed with some workers supported by the owner.

Conclusion

The constitution of Bangladesh recognizes equal rights for men and women. Despite such strong constitutional support, women are being mis-treated everywhere inside and outside the house. There are various laws to prevent violence against women such as: Women and Child Abuse Act 2000 (amended 2003), Dowry Prohibition Act 1980, Acid Crime Prevention Act 2002, Mobile Courts Act 2009, Pornography Control Act 2012, Prevention of Human Trafficking Act 2012 and so on. The provisions in these laws can play a strong and effective role in preventing violence against women. But sadly, there are weaknesses in the implementation and enforcement of all these laws (Akter 2007; Islam pers. comm. 2022). The contribution of garment factories to the economy of Bangladesh cannot be denied. The highest income (83%) comes from the export sector through garment factories (Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association 2022). By working in this sector, women are becoming economically self-sufficient. But in spite of these contributions, they are not receiving and enjoying the kind of rights they are supposed to get as a human being or as a worker. Through various studies and newspaper reports published at different times, the image of the inhuman life of women garment workers has come to light (Basirulla & Tasnim 2023; Haque & Bari 2021; ActionAid 2019; Haque, Sarker, & Rahman 2019; Jalava 2015). But the authorities concerned seem to be indifferent. Women are constantly being deprived of their human rights not only due to the strong profit greed of garment owners but a whole bunch of set of causes. Due to the lack of government supervision, the garment factory owners are not interested in protecting the rights of the community. Improving the human rights situation in the garment sector is the burning demand of the time. If the present condition continues, women will lose their interest in working in the garment sector.

These issues have been recognised in previous studies. Jalava (2015) has emphasized inadequate laws, unawareness of the garment workers about their rights and poverty as the main reasons behind the seven types of human rights violations of female garment workers that she pointed out – freedom of association, forced labor, discrimination, child labor, criminal justice, living wages and lack of safety. On the other hand, Haque, Sarker, & Rahman (2019) argued that lack of security, fear of losing job, all male bosses (absence of female superiors) and poverty were behind all types of sexual harassments taking place in the garments sector. Akter (2007) highlighted the discrimination between men and women in terms of working hours, type of work, wages, general leave and maternity leave etc. and identified patriarchy, less skill and knowledge of the women workers, weak enforcement of the laws as the core reasons behind such maltreatment in the garments factories. None of these studies has been able to provide all encompassing reasons behind the human rights violation, thereby not really revealing the overall picture. The present study has focused systematically on all-inclusive comprehensive causes that are related with society and culture (patriarchy, low level of education, lack of awareness), economy (poverty, fear of losing job) and the public structures (deficiency of government oversight, inadequate clauses in the law, weakness of national human rights commission), organizational (lack of strong trade union, weak NGOs and owners’ unwillingness). Some of these factors are overlapping. With such a compact set of factors in hand, the government should address the problems and causes together to improve the environment and lessen the human rights violations upon the women garment workers. All out policies and actions should be taken to promote fundamental principles and rights at work by gender mainstreaming and to ensure the participation of women workers in all areas of work in the factory according to the BLA (Bangladesh Labor Act) and ILO standards. The attitude of the owners and authorities should be humane to the workers. Owners should take swift actions against the misconduct of male colleagues or senior officers or supervisors with female workers. Garment industry authorities should ensure the job security of the workers; the government’s novel universal pension scheme needs to reach women workers. Factory management should give opportunities to form trade unions. All workers should be aware of their lawful rights and position given by the existing laws and take proper education. They need to be made aware of the human rights and other female and labor related rights through different workshops. The government should implement and supervise all the rules and regulations strictly and timely. All human rights-related NGOs should be strong and present the real picture of the garment industry.

References

ActionAid 2019, Sexual harassment and violence against garment workers in Bangladesh. https://actionaid.org/publications/2019/sexual-harassment-and-violence-against-garment-workers-bangladesh

Ain o Salish Kendra 2024, Violence Against Women – Domestic Violence (Jan-Dec 2023), 8 January 2024. https://www.askbd.org/ask/2024/01/08/violence-against-women-domestic-violence-jan-dec-2023/

Akhter, S., Rutherford, S., & Chu, C. 2019, ‘Sufferings in silence: Violence against female workers in the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh: A qualitative exploration’, Women’s Health, vol. 15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745506519891302

Akter, M. 2022, ‘Garments: What are the reasons for the declining rate of women workers in the garment industry?’, BBC Bangla, 27 January, Retrieved 2023-01-10. https://www.bbc.com/bengali/news-60159116

Akter, R., Teicher, J., & Alam, Q. 2024, ‘Gender-based violence and harassment in Bangladesh’s Ready-Made Garments (RMG) Industry: Exploring workplace well-being issues in policy and practice’, Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 5, article 2132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052132

Akter, S. 2007, ‘Gender discrimination at workplace: A study on garments industry in Bangladesh’, Institute of Bangladesh Studies, Doctoral dissertation, University of Rajshahi. http://rulrepository.ru.ac.bd/handle/123456789/574

Alam, M. A., Banarjee, S., Sharmin, S. & Akter, M. 2017, ‘Victimization and violation of rights of women in garments sector in Bangladesh: A study on women garments workers of Ashulia, Savar, Dhaka’, Bangladesh Institute of Labour Studies-BILS, p. 53-68. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Aurongajeb-Akond/publication/333506986_Victimization_of_Female_Migrant_Workers_in_Countries_of_Destination_A_Review/links/5cf0c7dfa6fdcc8475f8c5fb/Victimization-of-Female-Migrant-Workers-in-Countries-of-Destination-A-Review.pdf#page=54

Alamgir, F. & Cairns, G. 2015, ‘Economic inequality of the badli workers of Bangladesh: Contested entitlements and a “perpetually temporary” life-world’, Human Relations, vol. 68, no. 7, pp. 1131-1153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726714559433

Amnesty International 2022, Bangladesh. https://www.amnestyusa.org/countries/bangladesh/

Asian Development Bank 2024, Poverty data: Bangladesh. https://www.adb.org/where-we-work/bangladesh/poverty

Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association 2022, About Garment Industry of Bangladesh. https://www.bgmea.com.bd/page/AboutGarmentsIndustry

Basirulla, M. D. & Tasnim, F. 2023, ‘Nature of human rights violation on female garments workers in Bangladesh’, Khazanah Hukum, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1-17. https://doi.org/10.15575/kh.v5i1.22713

Begum, F., Ali, R. N., Hossain, M. A., & Shahid, S. B. 2010, ‘Harassment of women garment workers in Bangladesh’, Journal of the Bangladesh Agricultural University, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 291-296. https://doi.org/10.3329/jbau.v8i2.7940

The Business Standard, 2023, Universal Pension Scheme: Rushed or timely?, August 11. https://www.tbsnews.net/features/panorama/universal-pension-scheme-rushed-or-timely-680630

Cochran, W. G. 1977, Sampling Techniques, 3rd edn, Wiley, New York.

Daily Star 2024, High inflation likely pushed 5 lakh people into extreme poverty: W[orld] B[ank], 4 April, https://www.thedailystar.net/business/economy/news/high-inflation-likely-pushed-5-lakh-people-extreme-poverty-wb-3581496

Dey, B. K. 2017, ‘Social stratification, employment and empowerment among indigenous women in Bangladesh: A study of the Tea Labor Community’, Master’s thesis, University of Agder, Sylhet. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2459864

European Parliament 2015, European Parliament resolution of 29 April 2015 on the second anniversary of the Rana Plaza building collapse and progress of the Bangladesh Sustainability Compact, Procedure 2015/2589(RSP), Strasbourg. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2015-0175_EN.html

Financial Express 2022, New poor in Bangladesh remains high in May, says survey, June 6. https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/national/new-poor-in-bangladesh-remains-high-in-may-says-survey-1654432968

Haque, A. & Bari, E. 2021, A survey report on the garment workers of Bangladesh, 2020, Asian Center for Development, Sylhet. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350156796_A_Survey_Report_on_the_Garment_Workers_of_Bangladesh_2020

Haque, M. F., Sarker, M. A. R., & Rahman, M. S. 2019, ‘Sexual harassment of female workers at manufacturing sectors in Bangladesh’, Journal of Economics and Business, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 934-940. https://doi.org/10.31014/aior.1992.02.03.140

Haque, M. F., Sarker, M. A. R., Rahman, M. S., & Rakibuddin, M. 2020, ‘Discrimination of women at RMG sector in Bangladesh’, Journal of Social and Political Sciences, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 112-118. https://doi.org/10.31014/aior.1991.03.01.152

Hossain, M. A. & Tisdell, C. A. 2005, ‘Closing the gender gap in Bangladesh: inequality in education, employment and earnings’, International Journal of Social Economics, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 439-453. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068290510591281

Human Rights Watch 2014, Bangladesh: Protect Garment Workers’ Rights, February 6. https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/02/06/bangladesh-protect-garment-workers-rights

Human Rights Watch 2023, ‘Bangladesh: Events of 2022’, World Report. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/bangladesh. https://doi.org/10.46692/9781447318491

International Monetary Fund 2024, Bangladesh Datasets. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/profile/BGD. https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400281433.002

Islam, N. & Bhuian, M. N. 2019, Lapses in the Legal Framework related to Informal Employment Sector with Specific Focus on Women, UNDP Bangladesh, Dhaka.

Islam, M. S. & Al Amin, M. 2016, ‘Understanding domestic workers protection & welfare policy and evaluating its applications to managing human resources of informal sector in Bangladesh’, Journal of Asian Business Strategy, vol. 6, no. 12, pp. 246-266. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.1006/2016.6.12/1006.12.246.266

Jalava, M. 2015, Human Rights Violations in the Garment Industry of Bangladesh, Bachelor’s Thesis, Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences, Finland. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-2015060812853

Jamuna TV 2018, মানবাধিকার:সেবা না ব্যবসা? | (Transliteration: manobadhikar: sheba na banijjo) (English: Human Rights: Service or Business?) Investigation 360 Degree | EP 82, YouTube, December 10. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sSxTNyhNl7I

Kabir, H., Maple, M., & Usher, K. 2021, ‘The impact of COVID-19 on Bangladeshi readymade garment (RMG) workers’, Journal of Public Health, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 47-52. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa126

Khosla, N. 2009, ‘The ready-made garments industry in Bangladesh: A means to reducing gender-based social exclusion of women?’, Journal of International Women’s Studies, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 289-303. https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol11/iss1/18

Lehmann, A. 2014, ‘Cleaning up’, Deutsche Welle, June 30, https://www.dw.com/en/cleaning-up-bangladeshs-textile-industry/a-17746536

MacArthur, J. 2023, ‘Gender and sanitation: More than just a toilet’, SDG Action, March 6, Retrieved 2024-02-10. https://sdg-action.org/gender-and-sanitation-more-than-just-a-toilet/

Mahbub, M. 2022, ‘Sociocultural factors and gender role in female education: A phenomenal reviewed study of Rural Bangladesh’, SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4013668

Mahila Parishad 2016, Quest for Gender Equality and Social Justice Completion Report January 2010 to March 2016, Bangladesh Mahila Parishad, Dhaka, https://www.mahilaparishad.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/reportbmp1.pdf

Mannan, M. A. & Marri, S. N. K. 2020, নারী ও রাজনীতি (transliteration: Nari o Rajniti) (English: Women and Politics), Abosor, Dhaka.

People’s Republic of Bangladesh 1972, The Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, articles. 27-28. http://bdlaws.minlaw.gov.bd/act-367.html

People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Department of Labour 2015, The Labour Act 2006 [in Bangla].https://dol.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/dol.portal.gov.bd/legislative_information/2bb27f4d_f3b1_4808_b344_31a8294d60c0/Labour%20Law%202006.pdf

People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Department of Labour 2015, The Labor (Amendment) Act 2013. [in Bangla] https://dol.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/dol.portal.gov.bd/legislative_information/fe91f1af_e102_403b_945f_35475e5bf7e3/Bangladesh%20Labour%20Law%20(Ammendment)%202013.pdf

People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Ministry of Finance 2022, ‘Poverty alleviation’, Bangladesh Economic Review, pp.205-226. https://mof.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/mof.portal.gov.bd/page/f2d8fabb_29c1_423a_9d37_cdb500260002/22_BER_22_En_Chap13.pdf.

People’s Republic of Bangladesh, NGO Affairs Bureau Bangladesh 2024, List of All NGOs. https://ngoab.gov.bd/site/page/3de95510-5309-4400-97f5-0a362fd0f4e6/List-of-All-NGO.

Prothom Alo English Desk, 2021, Population below poverty line doubled, extreme poor trebled in 2020: SANEM, 24 January, https://en.prothomalo.com/business/population-below-poverty-line-doubled-extreme-poor-trebled-in-2020-sanem

Rahman, K. F. 2008, Unbundling of Human Rights, Academic Press and Published Library, Dhaka.

Rahman, M. H. & Siddiqui, S. A. 2015, ‘RMG: Prospect of contribution in economy of Bangladesh’, International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, vol. 5, no. 9. https://www.ijsrp.org/research-paper-0915/ijsrp-p45100.pdf

Rahman, S. & Rahman, M. M., 2017, নারী ও সমাজ (Transliteration: Nari o Somaj) (English: Women and Society), Kolom Publications, Dhaka.

Sikdar, M. M. H., Sarkar, M. S. K., & Sadeka, S. 2014, ‘Socio-economic conditions of the female garment workers in the capital city of Bangladesh’, International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 173-179. https://ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_4_No_3_February_2014/17.pdf

Star Digital Report 2022, ‘Bangladesh’s literacy rate now 74.66%,’ The Daily Star, July 27. https://www.thedailystar.net/youth/education/news/bangladeshs-literacy-rate-now-7466-3080701

Sultana, N. 2021, Gender (In)equality and Discrimination in the Readymade Garments Sector of Bangladesh: Is the Experience Of the (Female) Office Workers Overshadowed by the Experience of the Factory Workers?, University of Bergen, Master’s thesis, 9pdf. https://9pdf.net/document/yevrg6v7-equality-discrimination-readymade-garments-bangladesh-experience-overshadowed-experience.html

Syed, R. F. 2020, ‘Theoretical debate on minimum wage policy: A review landscape of garment manufacturing industry in Bangladesh’, Asian Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 211-224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-020-00106-7

Uddin, M. N. 2014, ‘Role of ready-made garment sector in economic development of Bangladesh’, Journal of Accounting, Business and Management, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 54-70 http://journal.stie-mce.ac.id/index.php/jabminternational/article/view/185

World Bank 2023, GDP growth (annual %)-Bangladesh. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=BD

Zohir, S. C. & Paul-Majumder, P. 1996, Garment workers in Bangladesh: Economic, social and health condition, Research Monograph-18, Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, Dhaka. https://bids.org.bd/uploads/publication/monograph/RM18_full.pdf

1 Mirpur area is noted for housing a good number of garment industries though it is not too far from the central down-town Dhaka.

2 Personal Communication January 2022.