Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 16, No. 2

2024

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

Involving Kyai and Thug Networks in Oil and Gas Company CSR Communication

Ahmad Taufiq1,*, Pawito2, Andre N. Rahmanto3, Drajat Tri Kartono4

1 Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia, ahmadtaufiq2018@student.uns.ac.id

2 Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia, pawito_palimin@staff.uns.ac.id

3 Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia, andre@uns.ac.id

4 Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia, drajattri@staff.uns.ac.id

Corresponding author: Ahmed Taufiq, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Jl. Ir. Sutami No. 36A, Jebres, Surakarta, Central Java, 57126, Indonesia, ahmadtaufiq2018@student.uns.ac.id

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v16.i2.8938

Article History: Received 30/11/2023; Revised 10/07/2024; Accepted 10/08/2024; Published 19/11/2024

Citation: Taufiq, A., Pawito, Rahmanto, A. N., Kartono, D. T. 2024. Involving Kyai and Thug Networks in Oil and Gas Company CSR Communication. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16:2, 57–78. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v16.i2.8938

Abstract

This paper explores local partners’ communication strategies in the ExxonMobil Cepu Limited CSR program in Bojonegoro Regency, East Java. The research data comes from in-depth interviews with 25 informants. They consist of representatives of oil and gas companies, governments, journalists, NGOs, and Corporate Social Responsibility beneficiaries. The results show that the local partner’s strategy in building symmetrical two-way communication with stakeholders can be understood at three levels. First, there is the process of social integration. The involvement of local elites, kyai, thug networks, and a grassroots approach in CSR communication is part of social integration. Second, there is social protection. The participatory communication network that has been built in the initial phase ultimately gives rise to a commitment to protect the program run by local partners. The depth of the relationship between local partners and stakeholders forms the third level, relations and social cohesion that give birth to a relationship of give and take.

Keywords

Communication Strategy; Corporate Social Responsibility; NGOs; Oil and Gas Sector; Indonesia

Introduction

The existence of non-government organizations (NGOs) and youth organizations or community organisations is increasingly being taken into account since Freeman (1984) conveyed the ideas of stakeholder theory as an inseparable part of company activities, especially corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs. Some consider the role of NGOs in carrying out CSR programs to be contrary to the values of NGOs and companies because there are different paradigms (Doh & Guay 2006; van Huijstee & Glasbergen 2008; Mzembe & Meaton 2012; Mzembe & Meaton 2014) and NGOs often oppose the actions of companies, particularly in the extractive industries. It is not uncommon for social activists to fight back, by facilitating and advocating for local communities to obtain compensation for the negative impacts of mining operations (Hudayana, Suharko, & Widyanta 2020). However, others are supportive because collaboration between companies and NGOs in Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives can be productive (Mzembe 2016). By working together, corporations and NGOs can exchange resources because they cannot be isolated in a public relationship (Jamali & Keshishian 2009). NGO-company collaboration can foster trust between both parties (van Huijstee & Glasbergen 2008; Rivera-Santos & Rufín 2010), or improve the company’s reputation in the eyes of society (Rondinelli & London 2003), foster corporate legitimacy (Eweje & Palakshappa 2009) and build social capital through shared learning (Millar, Choi, & Chen 2004; Arya & Salk 2006; van Huijstee & Glasbergen, 2008; Mzembe 2016).

The relationship between companies and NGOs in implementing CSR programs is documented by Toker (2013). Toker (2013) stated that corporate-NGO relations in CSR are paradoxical. However, in reality, many companies and NGOs work together. Therefore, this topic is still interesting because NGOs are trying to find a new role in the 21st century through CSR programs (Toker 2013).

This type of collaboration was conducted by ExxonMobil Cepu Limited (EMCL), a subsidiary of the oil company from the United States, ExxonMobil, which has implemented a CSR program in Indonesia since 2008. At the beginning of the implementation of the CSR program in Bojonegoro, East Java, Indonesia, most of the CSR programs were implemented through NGOs, which are part of civil society organizations (CSOs). However, based on the researchers’ notes and observations, in the 2017-2022 period, the majority of CSR programs associated with ExxonMobil Cepu were run by local NGOs. The novelty of this research is based on problems associated with CSR ineffective communications carried out by oil and gas companies. First, corporate CSR communication channels are still blocked, especially in the smallest community units, so local NGOs are considered to make CSR communication easier, both in conveying information and interaction (Morsing 2006a; Morsing 2006b). Second, the involvement of local NGOs is considered more ‘beneficial’ to companies than non-local NGOs. When problems occur, local NGOs can communicate with and coordinate with society more easily because they understand the conditions of social reality better. Third, local NGOs are seen by the community around the location where the company operates as ‘brothers’, or at least ‘neighbors’. If program and non-program problems occur, local NGOs can communicate and do a follow-up more easily.

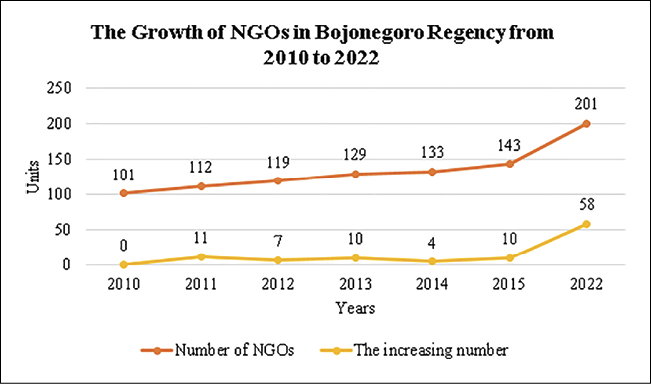

Bojonegoro Regency, where EMCL is located, experienced growth in the number of NGOs from 2010 to 2022 showing a significant upward trend. In 2010, there were 101 NGOs recorded, which increased to 201 in 2022. This trend reflects increased public awareness and participation as well as a growing need for advocacy and social services in the region (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Growth of NGOs in Bojonegoro Regency from 2010 to 2022

Source: Author, processed from Shodikin & Susetiawan, 2016 and Bakesbangpol (the National and Political Unity Agency) of Bojonegoro

For this reason, EMCL has collaborated with many local NGOs as partners in the 2017-2022. In fact, in addition to local NGOs, EMCL has also collaborated with youth and women’s organizations affiliated with Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and Muhammadiyah, large mass organizations in Indonesia, from 2020 to 2022. The shift in partner involvement, from previously national NGOs to local NGOs and OPP, is a unique and interesting phenomenon to study and differentiates this research from previous studies.

This research is also substantially different from research conducted by den Hond, de Bakker, & Doh (2015), which explored the factors that influence local company-NGO cooperation. In that study, factors behind NGOs’ collaboration with companies in CSR are the focus (den Hond, de Bakker, & Doh 2015). These include the company’s commitment to CSR, strategic suitability between company resources and NGOs, the company’s level of trust in NGOs, frequency of contact with NGOs, understanding of the NGO’s background, experience with NGOs, and the level of pressure given by NGOs to the company.

This current study further explores two topics which are the focus of this paper: the role of local partners (in this case local NGOs, local youth organizations, and local universities) as corporate partners in implementing CSR, and the involvement of local elites, religious leaders (kyai) and thug (preman) networks as a communication strategy for local partners, to help communicate CSR to the public. This local partner strategy was born to answer three problems at the ExxonMobil Cepu Limited (EMCL) CSR program location in Gayam District, Bojonegoro Regency, East Java Province, Indonesia as previously mentioned.

Referring to the existing gaps, this paper aims to answer this research question: What is the strategy of local NGOs in communicating ExxonMobil Cepu Limited’s CSR program? This paper provides a literature review, theoretical context, research methods, mechanisms for involving local partners in CSR, and local partner strategies in CSR communication.

Literature Review

Partnership between Companies and Local NGOs in CSR Implementation

There are six categories of CSR program implementation that companies want to achieve (Kotler & Lee 2005). They are Cause Promotions, Cause Related Marketing, Corporate Social Marketing, Corporate Philanthropy, Community Volunteering, and Socially Responsible Business Practice. According to Saidi and Abidin (2004), there are four models or patterns for implementing CSR programs that are generally applied by companies in Indonesia, namely: (1) Direct involvement; (2) company-owned foundations or social organizations; (3) partnering with other parties; and (4) supporting or joining a consortium. Meanwhile, according to Wibisono (2007), there are two patterns that companies generally utilize in implementing CSR. Namely, (1) self-managing, a pattern of direct involvement through foundations or corporate social organizations; (2) outsourcing, which has two patterns, namely partnering with other parties, such as NGOs, government agencies, universities, mass media, and joining or supporting short- or long-term joint activities. EMCL’s CSR implementation practice in Indonesia applies Socially Responsible Business Practices (Kotler & Lee 2005), with an outsourcing model or partnering with other parties (Wibisono 2007; Saidi & Abidin 2004).

CSR Communication

CSR communications are communications created and sent by a company about its activities (Morsing 2006a). Meanwhile, according to McWilliams and Siegel (2006), CSR communication is a company’s efforts to convey CSR program messages, obtain a good image, increase reputation, achieve product differentiation, and increase customer loyalty. CSR communication is important for three reasons (Ihlen, Bartlett, & May 2011). First, it reminds us that the public has different views about CSR and expects different things from organizations. Thus, CSR communication studies help explain its implications for corporate communications management. Second, CSR communication studies also provide the possible emergence of a dialogue. Third, citing Henriques (2007) in Ihlen, Bartlett, & May (2011), transparency is part of the moral basis for business behavior. Transparency can help organizations appear as trustworthy actors, through CSR communications, with various channels.

The company’s openness in communicating CSR is carried out using many communication channels such as CSR reports (Lock & Seele 2016), (Tewari & Dave 2012), company websites (Birth et al. 2008; Chaudhri & Wang 2007;Moreno & Capriotti 2009); mass media (Shim & Yang 2016;; Kim, Kim, & Cameron 2009), direct dialogue (Nielsen & Thomsen 2009; Verboven 2011 Ligeti & Oravecz 2009). In addition to transparency, CSR communication also creates credibility and legitimacy through a participatory process (Lock & Schulz-Knappe 2019). Besides, transparency also contributes to a company’s reputation (Ajayi & Mmutle 2020).

CSR Communication Strategy

Rogers (1982) in Cangara (2022, p. 64) defines communication strategy as a design created to change human behavior on a larger scale through the transfer of new ideas. Meanwhile, Middleton (1980), in Cangara (2022, p. 64), argues that communication strategy is the best combination of all communication elements starting from the communicator, message, channel (media), and recipient to the influence (effect) designed to achieve the optimal desired communication goals. One of the most used communication strategies in CSR communication is the model developed by Mette Morsing (2006b). In this model, Morsing suggests company managers, in addition to informing stakeholders about CSR initiatives, need to ensure that their companies improve their skills to continuously interact with stakeholders. Companies need to integrate information and interaction communication strategies in the companies’ view to develop CSR communications that are trustworthy for stakeholders. Company leaders need to understand how to build and maintain organizational sensitivity beyond corporate boundaries to enable their companies to be able to follow, understand, and even influence stakeholders to build and reconstruct expectations for the corporation. Many corporations communicate their CSR initiatives, but CSR communication to stakeholders is often one-way. As a result, although it increases company transparency, it does not satisfy stakeholders’ expectations.

Morsing’s CSR communication strategy model consists of two elements, namely: (1) informing strategy; and (2) interacting process strategies: moving from one strategy to another. Informing strategies suggest what issues stakeholders should be informed about CSR initiatives, i.e. how actions are taken to demonstrate conformity with stakeholders’ expectations in a one-way communication process. Meanwhile, the interaction strategy suggests a two-way communication process, namely what the company can do and encourage to increase stakeholders’ dialogue and thereby increase understanding of stakeholders’ expectations.

CSR Communication Strategy Through NGOs

The collaboration between NGOs and corporations in communicating CSR is starting to be widely researched. Rohwer and Topić, (2019) show that company-NGO partnerships are the right step and beneficial for society. Arenas, Lozano, & Albareda (2009) recognize that NGOs are key players in CSR communication, but their role is considered controversial and their legitimacy is questioned. This is reinforced by the fact that the role of NGOs in CSR programs has sparked debate about NGOs as ‘beneficiaries’ or ‘partners’. However, CSR communication still needs to involve NGOs (Sison & Hue 2015), because companies need to provide CSR communication strategic tools that are easy to use to create efficiency and effectiveness in communication about sustainability to stakeholders (Scandelius & Cohen 2016).

The synergy of CSR communication between stakeholders, NGOs, and corporations can also be done online (Yang & Liu 2020). The study found that two-way CSR communication is carried out by forming a communication network, where companies and NGOs are connected in a CSR hyperlink (online) network, to establish communication with other stakeholders. Consumer involvement in CSR communication can reduce the negative impacts caused by interactions in online media (Ma & Bentley 2022); two-way communication is important because CSR reports from oil and gas companies are considered to be less credible by NGOs due to its single form of communication, as shown by Lock (2017).

CSR communication studies through dialogue channels, between CSR facilitators (NGOs) and beneficiaries, should ideally adhere to participatory principles, including dialogue, participation, cultural identity, and empowerment, (Kloppers 2017). Cross-sectoral collaboration ‘bibingka’ emphasizes the importance of listening to the public’s voice (Sison & Panol, 2019; Maryani & Darmastuti 2017), as well as a combination of Buddhist philosophical approaches and local cultural values with CSR, such as research conducted by Sthapitanonda (2015), with CSR based on community empowerment (Parani 2011).

Involvement of Kyai and Thug Networks

This section explores the literature on kyai and thugs (preman). From an Indonesian perspective, kyai is another term for religious figures, especially in Javanese culture. In Javanese, the title kyai has three different meanings: first, an honorary title for something that is considered sacred; second, an honorary title for parents; and third, a title for Islamic religious experts, owning a boarding school and teaching classical books (Dhofier 1982). Kyai have charisma as a result of social strata relationships maintained within the components of society, linked to considerations regarding policies involving society, especially movement and mobilization (Jannah 2015). This is because kyai have authority, are decision-makers, and supporters of moral power (Keller 1995), agents of social change (Horikoshi 1987), as well as locomotives for increasing awareness of life and forming social and community actions (Aula 2020).

The relationship between religious values and CSR is also of concern to the researchers (Mazereeuw-van der Duijn Schouten, Graafland, & Kaptein 2014; Muniapan & Raj 2014; van Aaken & Buchner 2020). The integration of religious values by organizations in implementing CSR is important (Koleva, Meadows, & Elmasry 2023) because it can strengthen social and community solidarity (Kirat 2015). However, this paper is different because the focus of the study is on collaboration between local companies and kyai in communicating CSR programs to the public.

Turning now to thugs, preman is a term used for bad people (Ali 1993). A person or group of people can be labeled thugs when they commit crimes (political, economic, social). Research on the topic of thugs is often related to social politics. In Indonesia, the thuggery approach is still a very effective way to mobilize community support in political contestation. Thugs are one of the actors who influence social, economic, and local-national politics (Wicaksono 2022; Effendy 2013).

From the perspective of role theory, power is inherent in the roles that individuals play (Katz & Kahn 1966) and power is conceptualized as an individual’s ability to influence the behaviour of others (Dahl 1957; Ciszek 2015). Referring to this view, activists – including local NGOs, kyai, and preman networks – are conceptualized as entities that are monitored and managed by companies, especially by public relations practitioners, considering their significant role in implementing CSR. The collaboration of local NGOs with kyai and thug networks in CSR communication can be classified as mainstreaming collaborative-deliberative communication into political and social spaces which can produce greater inclusion (Demetrious 2008).

Method

Data Collection

This study used a case study method with an embedded multi-case type (Yin 2009). The dominant phenomenon of local NGOs and youth and women’s organizations affiliated with community organizations as CSR communicators was classified as a unique category, referring to Stake (1994) in Denzin & Lincoln (1994). To collect data through in-depth interviews with 25 informants from various elements, the following criteria were used in Table 1:

Source: Research data, processed (2023)

The in-depth interview took place in two stages. The first stage was done from April to June 2022. The second stage was done from July to December 2022.

Data Analysis

Research data analysis, according to (Yin 2009), consists of five phases: categorical grouping; direct interpretation; establishing patterns and finding correspondences; cross-case synthesis; and naturalistic generalization. First, at the phase of categorical grouping, the researchers tried to find data categories related to local NGO communication strategies in oil and gas company CSR programs, referring to Mette Morsing’s (2006b) model. Second, at the phase of direct interpretation, the researchers observed single examples and drew out their meanings such as interpreting the form of local NGO CSR communication strategies. Third, at the phase of establishing patterns and finding correspondence, the researchers tried to find patterns and relationships from the informants’ answers. Fourth, during the phase of cross-case synthesis, the researchers looked for the characteristics of local NGO communication strategies in EMCL CSR. Fifth, at the phase of naturalistic generalization, the researchers concluded the communication strategy from the interpretation of data from the previous data analysis phases.

Results and Discussion

Partnership between Companies and Local NGOs in CSR Implementation

Partnership Mechanism for Companies and Local NGOs in CSR

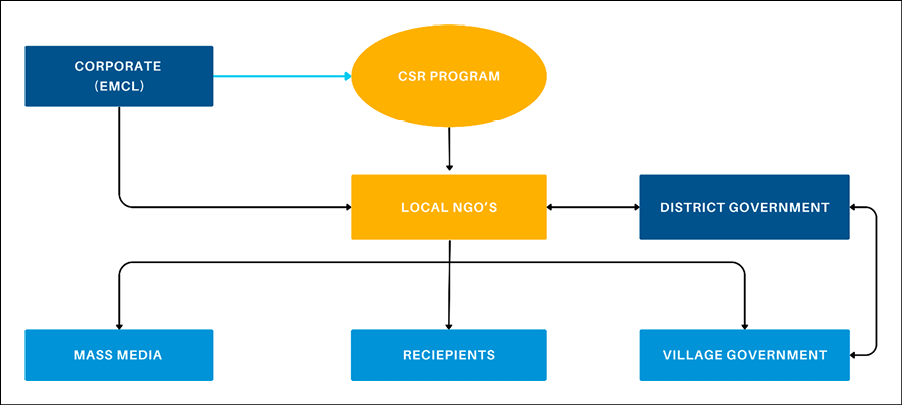

The research results showed that EMCL applies procedural mechanisms in the process of involving local NGOs as CSR program partners, as presented in Figure 2:

Figure 2. Mechanism for Involving Local NGOs in CSR Programs

Source: Research data (Author, 2023)

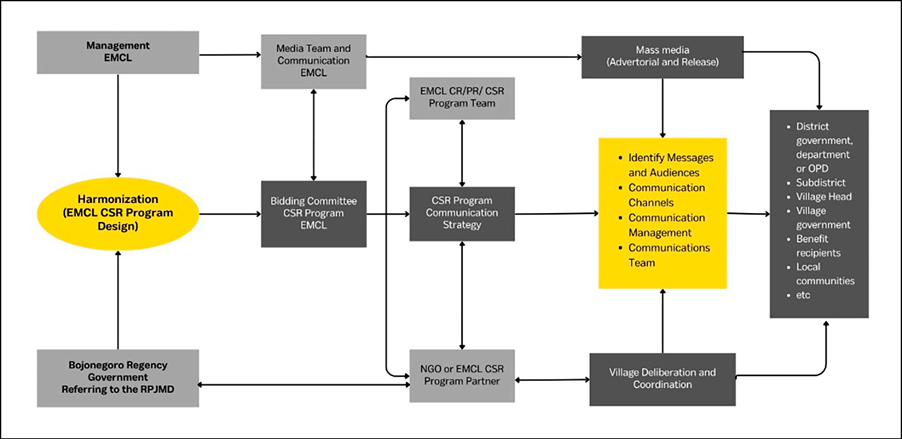

Based on Figure 2, the determination of the company’s CSR program was carried out after there was harmonization or synchronization of the program design between EMCL management and the Bojonegoro Regency Government program, referring to the Regional Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMD). Synchronization or harmonization not only discussed the type of program but also determined the program targets that can extend beyond the operational area of the company. However, not all company programs were transferred by the district government. Companies still had a right to determine certain types of programs that were tailored to the pillars of the company program, namely economics, education, health, environment, and infrastructure. Synchronization or harmonization meetings were held at the end of each fiscal year or the beginning of program planning. After approving the form of the program and targets, EMCL then determined potential partners. EMCL used a bidding mechanism by inviting potential partners, including NGOs, youth organizations, and universities to submit proposals. After passing administration, prospective partners were asked to make a presentation. For those who passed, the next kick-off meeting was discussing program implementation strategies, including CSR communication strategies. CSR communication strategies include elements of the messages and audience identification; communication channels; communications management; and communications team. Meanwhile, communication channels used two approaches: mass communication (mass media), group and interpersonal communication through village deliberation forums, and personal coordination. In this phase, the role of local NGOs was not limited to implementers because they are CSR communicators as well. During program implementation, local NGOs as partners intensively coordinated and communicated with companies in implementing CSR communications to stakeholders.

ExxonMobil Cepu Ltd CSR Program Partner

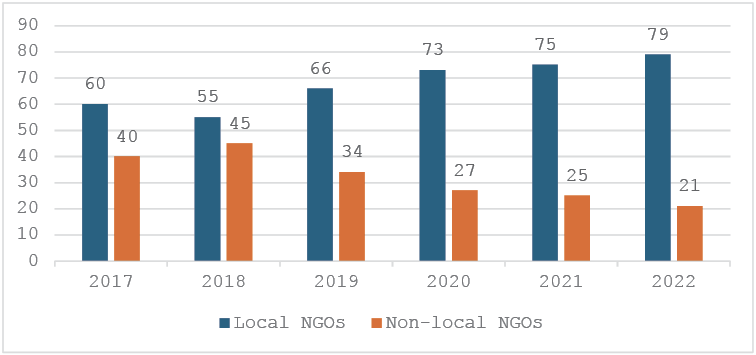

The EMCL CSR program developed in Indonesia consists of four pillars, namely: education, health, infrastructure, and economic development. In implementing CSR, the company collaborated with third parties as program partners. The partners ranged from NGOs to universities. The following is the data of partners for the EMCL CSR program for the five years period (2017-2022), as in Table 2:

Table 2. ExxonMobil Cepu Limited CSR Program Partner in 2017–2022

Source: ExxonMobil Cepu Limited, processed (2023)

Based on the table above, it can be seen that the company’s commitment to involving local partners in Bojonegoro was quite high. Of the 33 EMCL program partners in 2017, 20 of them, or more than 60 percent, were partners from Bojonegoro Regency, both NGOs and universities. There was a decrease in the number of local partners in 2018, but from 2019 to 2022 the number of local partners implementing EMCL’s CSR programs was above 65 percent. The number of local partners reached 79 percent in 2022, while non-local partners were around 21 percent. The data above shows the company’s commitment to cooperating with local partners was very strong.

ExxonMobil Cepu Limited CSR Program Communicator

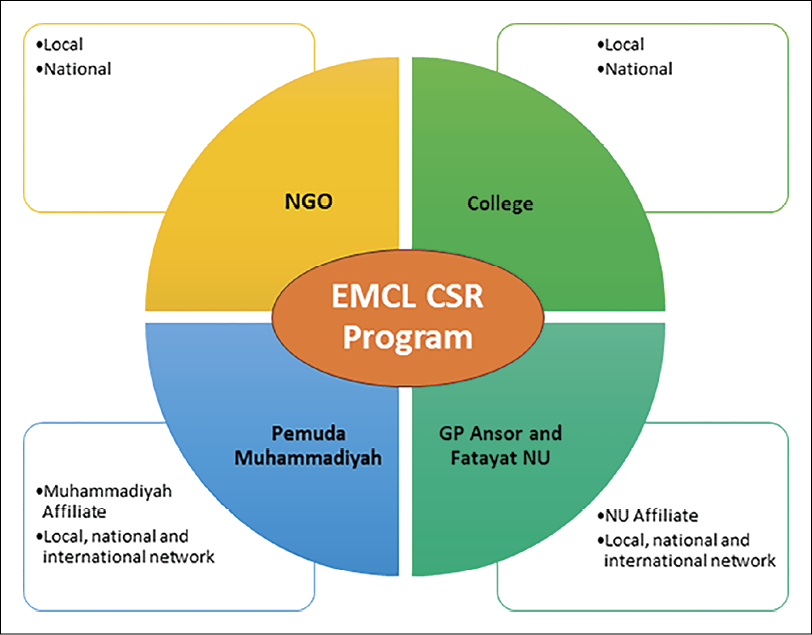

Referring to the 2020 CSR companion partner data, EMCL included three partners that were not legal foundations (NGOs/NGOs) or universities. However, youth organizations and women’s organizations (OPP) are legal associations. The three organizations were the Ansor Youth Movement (GP), Muhammadiyah Youth, and Fatayat NU. GP Ansor is a youth organization affiliated with Nahdlatul Ulama (NU). Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) is a social religious (Islamic) organization, which has quite a large influence in Indonesia and even the world. Likewise, Fatayat NU is a young women’s organization affiliated with NU. Apart from involving GP Ansor, EMCL also involved Muhammadiyah Youth as a partner. Muhammadiyah Youth is an autonomous organization affiliated to Muhammadiyah. Muhammadiyah is also a social religious (Islamic) organization, which has quite a large influence in Indonesia.

Based on the researchers’ notes, it was only in 2020 that EMCL involved OPP as program partners. Until then, EMCL had never involved OPP as a partner in running the PPM (Community Development Program) in the Bojonegoro, Tuban (East Java Province) or Blora (Central Java Province) areas. As far as the researchers’ observations are concerned, the company had only involved GP Ansor, Pemuda Muhammadiyah, and Fatayat as activity partners. EMCL had only supported the activities of the GP Ansor, Muhammadiyah Youth, and Fatayat NU organizations. However, with the inclusion of these three OPPs as program partners, EMCL’s CSR program communicators expanded, from previously only local and non-local NGOs, as well as universities, to youth organizations, that are affiliated with community organizations. The involvement of these three OPPs was considered appropriate because all three are youth organizations that have networks down to the lowest base level, the village (branch). By involving those three, EMCL was assisted in conveying information about CSR programs to stakeholders in target villages. The existence of these three OPPs completed the fragment of elements that have accessed the EMCL CSR program in several years, as depicted in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Fragment of ExxonMobil Cepu Limited CSR Program Partner

Source: Research data, processed (author)

In the CSR communication strategy model of Mette Morsing (2006b) there are three two-way communication processes: (1) increasing interaction between the company and stakeholders in a social partner forum, from dialogue to partnership; (2) local articulation; and (3) proactive support. The research results showed that what happened was not only from dialogue to partnership, as stated by Morsing, but also cooperation between local companies and NGOs started to lead to collaboration. The inclusion of youth organizations and women’s organizations as communicators of EMCL CSR programs, in addition to NGOs (local and non-local) and universities, broadened the definition of opinion leaders, which not only referred to individuals but also organizations as communicators of CSR programs.

The involvement of youth organizations such as GP Ansor, Fatayat NU, and Pemuda Muhammadiyah which are affiliated with large mass organizations (NU and Muhammadiyah) was a new strategy, which has never been found in previous research. The steps EMCL took could be analyzed as an effort to achieve the widest possible stakeholder legitimacy as found in research conducted by Lock and Schulz-Knappe (2019) and to bring benefits to the company’s legitimacy (Kwestel & Doerfel 2023).

The synergy between companies and local NGOs benefited local communities, (Simanis & Hart 2008), and was seen as a form of recognition for local communities (Kemp 2010). Even referring to the perspective of companies had the potential to enable them to be seen as development agents, especially in partnership with the government and NGOs (Hamann & Acutt 2003). This means that if companies can manage their CSR well, local NGOs, as the research findings above demonstrate, can act as development agents (Rademacher & Remus 2017). However, Hamman and Accut (2003) reminded us that although this partnership can be beneficial for NGOs, NGOs need to maintain a critical position.

Strategy Informing CSR Programs: The PESO Model+ Approach

Research shows that there are six segments targeted by local NGOs to inform stakeholders about CSR programs. Six targets determine the form of strategy used by local NGOs. Namely, for the beneficiaries, district government, village government, mass media (including social media and other publication media), NGOs themselves, and companies. Especially for companies, the strong link is with program coordination, as illustrated in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4. CSR Program Communication Actors ExxonMobil Cepu Limited.

Source: Research data, processed (2023)

The first strategy for conveying information to beneficiaries was carried out in two forms of communication. Namely, formal and informal or non-formal communication. This type of formal communication was carried out when it was related to activities like village deliberations (musdes) containing an explanation of the outline of the program. Throughout the program, there were at least three musdes: namely, socialization, planning, and handover. In the musdes, there was an interactive dialogue between program partners, companies, government (especially village governments), and beneficiaries.

For example, the direct dialogue was carried out: In the form of a musdes handing over the program or the usual village consultation, then there was dialogue and community input. (MG Interview, May 10, 2022)

Formal communication was also carried out by local NGOs with government officials. Starting from village, sub-district, to regency levels. However, the mechanisms varied. When it came to the village government, it was more about the technical implementation of CSR programs. Meanwhile, with sub-district and regency parties, it was in the form of coordination.

Apart from formal communication strategies, in carrying out their function as communicators of CSR programs, local NGOs also used informal and non-formal approaches. There were various mediums used by local NGOs to convey information. Forums and approaches to non-formal communication were carried out by STIKES (School of Health Sciences) of ICsada. The strategy utilized various cultural or informal community forums. These included routine community tahlilan (an Islamic traditional activity of communal dzikr) forums and the rewang (helping others who have a celebration) tradition for residents who had celebrations. This strategy was said to be part of strengthening the program’s roots, a kind of social cohesion that aimed to socially bind. The communication strategy was outlined in the work terms of reference, which was submitted in the proposal to the company.

Including tahlilan, rewang. Because jenenge dulur (in the name of brotherhood), humanizing humans. (NJ Interview, July 1, 2022)

NGOs did not only use a group communication approach in cultural and informal community forums but also used an interpersonal communication approach with residents, at the appropriate location where the beneficiaries were located, for example, in rice fields, moors, and so on.

We are nurses. We must be present in society. Our program is born out of the program of nurses are family’s friend program. Even we have involved ourselves in their activity at rice fields. Sometimes, we check in the rice fields. So far, it doesn’t have to be formal at the event. On the moor, we are asked to help them plant rice in the ricefield. Doing such things is fun and can help build a strong bond among us. (NJ Interview, July 1, 2022).

Another informal or non-formal strategy was conducted by having coffee together. It could be at the village head’s house, a resident’s house, or a coffee shop. This method was often used by local NGOs, one of which is LIMA2B. These NGOs often communicated informally to village elites and community leaders in unofficial places. For example, when someone from one of the NGOs was at the shop, he was asked by the village head or residents what programs there were. Then, he informally conveyed the activities being carried out. This method was sometimes more effective in building relationships and people.

Non-formal communication was also carried out by NGOs by establishing village information centers in beneficiary villages or base camps. This was done by STIKES ICsada in the health program. Apart from being a base camp, the village information center was also used to serve residents. For example, if someone asked for a health check, that was also provided. Some residents asked about the company’s flares which continued to grow. NGOs also provided information to the public about what was happening.

The researchers also found the sanepan (figurative/joking) communication style applied by LIMA2B NGO. This was done when local NGOs communicated the program to the implementation team. Usually, the program funding was based on progress terms, namely 25 percent, 50 percent, and 25 percent. For example, to disburse 50 percent of funds, someone must complete a report on the use of 25 percent of funds. Communication was carried out by NGOs using sanepan, so that the Timlak (the implementing team) did not feel that they were being ordered to perform certain tasks.

For example, one Timlak could not speak smoothly, then I asked him to joke. Look, now the money is in the bank, but your report has not been there yet. What if I give you a crowbar and a hammer? You know where the bank is located, then just pick up the money. They even laughed. Finally, they finished the report. You have to use informal methods. If they are invited formally, they usually do not even have the responsibility to complete it. (MG Interview, May 10, 2022)

NGOs also carried out informal communication with religious and community leaders. Conveying CSR program information to religious and community leaders consisted of two sessions. The first session aimed to inform and ask for support. And secondly, it was usually related to the implementation of activities for security purposes and program continuity. The NGO strategy in informing the second program was carried out in two targets, namely the village government and the district government. To the village government, CSR program partners generally carried it out in two ways, formal and informal communication. Non-formal and informal communication was started after local NGOs were declared partners by EMCL. In this stage, the NGOs were invited by the company to the village, a kind of introduction about the NGO that accompanies the program. Then an agenda was prepared for formal communication. Forms of formal communication from NGOs to village governments included socialization or village meetings.

Meanwhile, NGO strategies in informing regency governments of CSR were carried out formally by sending official letters to invite village meetings, coordinating, and harmonizing CSR programs.

We often get invitations. From partners of NGOs. (EVM Interview, May 19, 2022)

The NGOs’ strategy in informing the third CSR program was carried out in the mass media in various forms. The approach was similar to that of the company. The research results showed that there were two strategies for local NGOs to inform the mass media about programs, namely in the form of invitations for coverage, sending activity releases, and advertorials. The company recommended sending CSR activity releases from local NGOs to the mass media. However, both releases and advertorials sent to mass media had to obtain approval from the company.

The results (implementation of the CSR program) must be disclosed as widely as possible to the public (through mass media releases). For example, the inauguration of the program. (JHP Interview, May 11, 2022)

The researchers found that in mass media reports and advertorial materials sent by local NGOs, there were three key sentences emphasized by the company to appear in the mass media. These three key sentences are new strategies. The three key sentences are a form of company concern, the company’s contribution to the surrounding community, and as a good neighbor,

The fourth local NGO strategy was to disseminate information about CSR programs through social media. The choice of social media as a channel for disseminating information was based on the reason that today’s audience is mostly on social media. Thus, the company encouraged NGOs to actively publish CSR activities on partners’ official social media.

Yes, we also have the I’m Healthy program on Facebook. We also have an IG [Instagram] account, but we a more FB [Facebook] active users. There is also online media. (NJ Interview, July 1, 2022)

The fifth strategy of local NGOs was to disseminate information about CSR programs using other publication media. This could not be separated from the mechanisms implemented by local NGOs, in connection with the communication strategies promised to companies. First, banners and pamphlets promoted certain events. This publication tool had to be present at every event, especially formal activities, such as village meetings. Banners or pamphlets not only contained the musdes’ agenda, but also the logos of SKK Migas1, companies, partners, and even the logo of the regency government. Banners were made by NGOs, with company approval. The mechanism was that partner NGOs were asked to create a banner design and send it to the company. Next, the company team corrected the font, color, size, and color composition until the proportions were balanced or not. If approval had been obtained from the company, new partners of NGOs were allowed to print the banners.

The second was the Information Board in the village. Researchers found that information boards were still being used as a channel for disseminating information in the Cepu Block. On several information boards in the village, researchers found there were announcements related to program activities and the company in general. However, the use of information boards was still minimal. The third avenue was book publication. Another medium used was a book of success stories about programs that were considered successful. The fourth was a documentation video program. NGOs also used other media such as program documentation videos as channels for conveying CSR messages to wider stakeholders.

And finally, we are usually asked to make videos, but that is also for their needs, the company, not for publication. When you want to publish it, there will be a review from them, either in print or online media. (MR Interview, July 20 2022)

The fifth medium used was the NGOs’ website and YouTube account. Even though NGOs used many publication media channels, all had to receive approval from the company. This meant that NGOs could not directly publish their activities.

Based on the data above, the researchers concluded that what local NGOs did, especially those activities related to mass media and social media, was a form of the PESO Model. The PESO Model was developed by Gini Dietrich in 2014 (Thabit & Cision 2015). Previously, the PESO model was widely applied in designing strategies in the world of public relations (Pieczka 2019). PESO is an acronym model of the letter abbreviations, which are the parts it focuses on: paid media, earned media, shared media, and owned media.

The data above showed that EMCL program partners used the PESO Model to disseminate information to the public. The paid media model was used for advertorial advertising in print and online media, as was done by NGOs with mass media. Meanwhile, earned media and shared media were in the form of social media such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Furthermore, owned media was conducted by utilizing company and partner websites. The researchers concluded that the strategy for informing CSR programs carried out by NGOs was a combination of the PESO Model with dialogue channels, so the researchers called it the PESO Model+.

Two-way communication or dialogue between CSR facilitators (local NGOs) and beneficiaries was carried out to comply with participatory principles, including dialogue, participation, cultural identity, and comprehensive empowerment, as stated by (Kloppers 2017). The dialogue approach was carried out by EMCL CSR program partners in village deliberations or meetings, namely socialization, planning, and program handover.

Meanwhile, the use of three key sentences, as found in local NGO strategies in informing the mass media of CSR programs, such as the sentences: ‘a manifestation of the Company’s concern’, ‘the company’s contribution to the surrounding community’, and ‘as a good neighbor’ was a core message concept that did not automatically emerge, but was the result of careful internal and external analysis. These three important sentences were the company’s efforts to show objective claims (results), as required by Morsing’s model (2006b) in conveying the content of CSR program messages. The researchers’ analysis showed that the use of the three key sentences above was a construction built by the company to create EMCL credibility, as well as an effort to achieve stakeholder legitimacy. This was in line with research (Lock & Schulz-Knappe 2019), which examined the relationship between the credibility of CSR communications and company legitimacy.

Engagement Strategy: Involve Local Elites and the Gentho Network

Involving Village Elites in Determining Local Community Organizers (LCO)

The stakeholder engagement strategy carried out by local partners to build a two-way communication process regarding the implementation of the company’s CSR program was to build dialogue with influential stakeholders and community opinion leaders. The role of village heads is still dominant in determining the success of implementing CSR programs in target villages. Approaches to village elites were carried out by local partners during pre-conditions or before the program was implemented. This often involved having coffee together in a coffee shop or village head’s house informally, as a form of camaraderie and lightening the atmosphere.

Apart from personal, familial, and informal approaches, local partners also gave significant authority to the village head to determine the membership of the technical implementation team for the CSR program in the target village. The mechanism was that local partners prepared several team names needed for the CSR implementation team (LCO). Next, the village head determined the names. During the process of determining the name of the LCO team, local partners provided an overview of the composition of the LCO that had to be fulfilled, which included: women’s participation, and representation of hamlet leaders, community leaders, religious leaders, youth, and village officials. However, the final decision remained in the hands of the village head.

In Gayam, the main key was still in the hands of the village head although other figures were also involved, such as the hamlet head or others. (MG Interview, May 10, 2022)

Gentho Network for CSR Program Security Backup

Another stakeholder involved is Gentho (local thugs). The involvement of thugs in program implementation is a significant innovation. This strategy was implemented by the local NGO LIMA2B when carrying out a CSR program in the Gayam Village/Gayam Sub-district. The involvement of local thugs was carried out to ensure the smooth implementation of the program because there had previously been security disturbances in the implementation of the CSR program.

Before the recruiting stage, the gentho’s involvement in the CSR program went through several stages. First, local NGO LIMA2B identified and investigated the causes of the loss of building materials for a CSR program in the form of infrastructure development. In the identification process, it was found that building materials were lost because they were stolen by several local thugs in the program target villages. Next, NGO LIMA2B carried out an informal approach and communication with people identified as suspects in the disappearance of program building materials. However, informal communication efforts also failed. Similar incidents still happened repeatedly. Third, a simple mapping was carried out to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the prominent figures, including gentho which were still quite strong, in the identified target villages. The mapping was done by looking for the weaknesses of these people. Then, lobbying people who could overcome the resistance of key individuals was done to help the success of the CSR program run by local NGOs.

Based on the mapping, it was discovered that for one of the key thugs, his weakness was that he deferred to his wife. The CSR program management from a local NGO approached the thug’s wife, so that her husband would provide support for the implementation of the CSR program. Apart from that, local NGOs coordinated with the Gayam police, because, based on the results of police identification, in several cases, some criminal acts in the Gayam area were suspected to have been carried out by this network of thugs and more were anticipated.

We call it my philosophical language like the Kresno puppet. Kresno could be the winner because he had the book. The book was Jitapsara, the standard of Bharatayudha. The book contained a full explanation of the strategies to win a war. (MG Interview, May 10, 2022)

The strategy of involving thug networks turned out to be quite effective. The thug was ready to support the program. So, then local NGOs implemented the fifth stage, namely involving thugs in CSR programs. CSR program management from local NGOs involved local thug networks as part of the CSR program, especially as a building materials security officer.

We invited them, we also created a good connection with Gentho. What field was he involved in? Finally, we let them know, we are involved as PK (security guard), monitoring building materials. Or waker is the term [in Javanese] (MG Interview, May 10, 2022)

Religious Approach: Kyai as Opinion Leader, Tahlilan as Communication Medium

The characteristics of a region differentiate the strategies taken. If Gayam Village/Sub-district local partners embraced local thugs, considering their strong influence, it was different from other villages, such as Beged, Begadon, Mojodelik, and Ringintunggal Villages, all of which are in the Gayam Sub-district. In this area, local partners’ strategies were related to religious perspectives to support the successful implementation of CSR programs, which were divided into two dimensions: kyai individuals and religious rituals.

Kyai individuals were involved as opinion leaders in CSR communication to wider stakeholders. The process of involving kyai in CSR programs included, among others, involving them as LCOs in implementing the program in target villages, together with elements of women, youth, and village government officials. The strategy of involving kyai in LCO was carried out by almost all local partners (local NGOs, local youth organizations, and local universities) to help communicate CSR to the public and support program implementation. Apart from being involved in LCO, kyai also acted as a medium for consultation for local partners on various problems and program implementation strategy options. The involvement of kyai in local partner communication strategies took place in three phases: Social integration, social protection, and social relations and cohesion. (1) Social integration meant blending into the community. This phase was started by the company’s public relations officer who first sowan (visited) the kyai’s house. The message conveyed was to ask for support so that CSR programs and other company activities could run smoothly. Sowan to the kyai was quite intensively carried out by company PR, including before religious public holidays.

The one who visits us is the company’s public relations (company). They came personally, they came to my house, or the kyai’s house. (FD Interview, November 21, 2022)

However, in its development, local partners, on their own initiative or encouragement from the company, also intensively coordinated and communicated with kyai as part of the stakeholders who could act as opinion leaders and actors who influence the success of CSR. This was proven by the involvement of kyai as LCO CSR partners in almost all programs facilitated by local partners in villages in the Gayam District.

The next phase in the involvement of kyai can be seen as efforts to achieve: (2) social protection and community protection. With the kyai’s role in the community, the involvement of kyai by local partners was considered as part of the protection and prevention of possible disruptions faced in implementing CSR programs in target villages.

Also as a precautionary measure, if our program is disturbed (disrupted), then we can get support from Tomas or Kyai. (MG Interview, September 6, 2022)

Apart from the two things above, the involvement of kyai in CSR programs functions as a form of (3) social relations and cohesion, efforts to build relationships, and social glue. Social relations can be formed through a give-and-take relationship between local partners and kyai. Research shows that in several cases, religious figures often received program assistance from companies and local partners for the various needs of the institutions they cared for, especially educational institutions and the organizational needs of these religious figures.

Mr C once helped his TPQ (Alquran education school), paving the courtyard, and a small table for the Koran. The point is, I have spoken to religious and community leaders several times. (FT Interview, 21 November 2022)

In return, kyai and religious figures helped local partners and companies to secure and provide support for the implementation of CSR programs in target villages, as stated by MG informants. Forms of support were provided in forums at village meetings or in informal approaches to grassroots residents.

In addition to involving kyai figures, the strategy of the two local partners was to use religious rituals and local culture as a medium for two-way communication at the grassroots. This form and approach to non-formal communication was carried out by local partner Stikes ICsada. The strategy taken utilized various cultural or informal community forums. These included the tahlilan forum (collective prayer in the Islamic tradition, which is usually held once a week) for residents and the rewang (mutual cooperation, voluntary helping) tradition for residents who had celebrations. This strategy was part of strengthening the roots of the program, a kind of social cohesion that aimed to bind socially.

The research data above shows that the approach taken by local partners to local elites, kyai, community leaders, and gentho (thugs), to grassroots communities is a strategy to open dialogue or two-way communication (Kloppers 2017). This strategy can contribute to the company’s good reputation (Ajayi & Mmutle 2020). It can also create credibility and legitimacy for the company because local partners and these parties are stakeholders whose involvement is through a participatory process (Lock & Schulz-Knappe 2019). So, it can be concluded that the local company-partner partnership is the right step and provides benefits for society in general (Rohwer & Topić 2019).

This interaction, with various stakeholders, can be seen as part of a social partnership, an approach from dialogue to a partnership (Morsing 2006b). In fact, according to the authors, it could be developed further, namely from partnership to collaboration. The condition was that the company opened itself by providing significant space for the public to be involved openly, and to have discussions together, from the beginning of planning to monitoring the company’s CSR program. Two-way communication/dialogue between CSR facilitators and communicators (local partners) and beneficiaries was also carried out by adhering to participatory principles, comprehensive empowerment, and the use of cultural identity (Kloppers 2017), which here was realized in religious ritual forums and culture in the form of tahlilan and mutual cooperation. Another interpretation of the involvement of kyai and thug networks by local partners in implementing CSR programs is that the communication acted as a negotiation tool to prevent communal violence. For this reason, their involvement in LCO CSR could be seen as a social investment to build trust and empower residents, involving village activists and local communities in peaceful negotiations (Hudayana, Suharko, & Widyanta 2020).

Conclusion

The research aimed to provide an in-depth overview of local NGO communication strategies in ExxonMobil Cepu Ltd’s CSR program. The findings showed that, first, local NGOs are quite successful in communicating EMCL’s CSR program to stakeholders. The advantages come from local relationships and having a network down to the branch (village) level makes it easier for EMCL partners to convey program information and interact with various levels of society in implementing CSR programs to stakeholders. Adaptation with program beneficiaries and the community in general is carried out more quickly, considering that local NGOs live and operate in the same area as program beneficiaries.

Second, the local NGO strategy in communicating EMCL’s CSR program also benefits the company in maintaining its corporate reputation and legitimacy. Local NGOs are relatively easier to communicate with and coordinate regarding the dynamics occurring in society because they better understand the situation and conditions of social reality, both to the government, beneficiaries, and other parties. Thus, CSR program communication is more effective and efficient.

However, efforts to build reciprocal relationships between local NGOs and beneficiaries remain problematic. Program information is still centralized in the village elites. There is a tendency for local NGOs to feel that the community is represented by the village government. So, EMCL partners do not go directly to the community, but only to the village government. In fact, not all information conveyed to the village government or village head is conveyed to the community. The public only knows about CSR program information through village meetings. Thus, CSR information is distorted. Second, cultural forums are not used. Local NGOs do not utilize cultural forums as part of their strategy for conveying information and program interactions to beneficiaries. For example, tahlilan forums, yasinan, routine recitations, jagongan, cangkrukan, and others are not part of the communication strategy. Third, there is no communication down to the smallest unit. Local NGOs make little effort to inform CSR programs down to the smallest units in society, such as the rukun tetangga [RT neighborhood association] or rukin warga [RW community harmony] level. In fact, socialization down to the smallest unit is very important because sometimes the information conveyed at the village level is not disseminated back to the lower level. Meanwhile, CSR program targets are mostly within the smallest villages, namely hamlets, RTs, or communities.

Thus, it can be concluded that the local partner’s strategy in building symmetrical two-way communication with stakeholders formed three propositions. The first is the social integration process. The involvement of local elites, kyai, thug networks, and a grassroots approach in CSR communication is part of social integration. The more intensely the parties communicate in two-way, symmetrical ways, the more unity in the social entity can be achieved. The second is social protection. The participatory communication links that were built in the initial phase ultimately gave rise to a commitment to protect programs run by local partners. This was demonstrated by the actions of village elites, kyai, and thugs who were willing to provide support and security for the program in the target villages. In other words, social protection was formed and influenced by the depth of the social integration process of the parties involved. In the end, the depth of the relationship between local partners and stakeholders formed the third phase, that is, a relation and social cohesion which created a relationship of give and take. Local companies and partners helped with the needs of local elites, kyai, thug networks, and the grassroots. On the other hand, local elites, kyai, and thug networks helped local companies and partners maintain a conducive climate in local villages, provided support, and helped CSR programs run smoothly.

For the success of CSR programs in the future, the researchers recommend the importance of substantive two-way communication, building CSR communication to the smallest units of society through non-formal and cultural forums, as well as interaction with opinion leaders in the smallest units of target villages.

The limitation of this study is that it only captures the strategies of local NGOs in communicating CSR programs. The researchers recommend research that explores the company’s synergy with different stakeholders, including the government and mass media.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support from Universitas Sebelas Maret for this research.

References

Ajayi, O. A. & Mmutle, T. 2020, ‘Corporate reputation through strategic communication of corporate social responsibility’, Corporate Communications: An International Journal, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-02-2020-0047

Ali, L. 1993, Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia, Edisi Kedua, Balai Pustaka, Jakarta.

Arenas, D., Lozano, J. M., & Albareda, L. 2009, ‘The Role of NGOs in CSR: Mutual Perceptions Among Stakeholders’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 88, no. 1, pp. 175–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0109-x

Arya, B. & Salk, J. E. 2006, ‘Cross-sector alliance learning and effectiveness of voluntary codes of corporate social responsibility’, Business Ethics Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 211–234. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq200616223

Aula, S. K. N. 2020, ‘Peran Tokoh Agama Dalam Memutus Rantai Pandemi Covid-19 Di Media Online Indonesia’, Living Islam: Journal of Islamic Discourses, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 125-148. https://doi.org/10.14421/lijid.v3i1.2224

Birth, G., Illia, L., Lurati, F. & Zamparini, A. 2008, ‘Communicating CSR: practices among Switzerland’s top 300 companies’, Corporate Communications: An International Journal, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 182-196. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280810869604

Cangara, H. H. 2022, Perencanaan dan Strategi Komunikasi, PT RajaGrafindo Persada, Depok.

Chaudhri, V. & Wang, J. 2007, ‘Communicating corporate social responsibility on the internet: A case study of the top 100 information technology companies in India’, Management Communication Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 232-247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318907308746

Ciszek, E. L. 2015, ‘Bridging the gap: Mapping the relationship between activism and public relations’, Public Relations Review, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.05.016

Dahl, R. 1957, ‘Decision-making in a democracy: The Supreme Court as national policy-maker’, Journal of Public Law, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 279–295.

Demetrious, K., 2008, ‘Corporate social responsibility, new activism and public relations’, Social Responsibility Journal, vol. 4, no. 1-2, pp. 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1108/17471110810856875

den Hond, F., de Bakker, F. G. A., & Doh, J. 2015, ‘What Prompts Companies to Collaboration with NGOs? Recent Evidence from the Netherlands’, Business and Society, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 187-228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650312439549

Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S 1994, ‘Introduction: Entering the field of qualitative research’, In Denzin N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (eds), Handbook of Qualitative Research, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 1-17.

Dhofier, Z. 1982, Tradisi Pesantren: Studi Tentang Pandangan Hidup Kyai, LP3ES, Jakarta.

Doh, J.P. & Guay, T.R. 2006, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: an institutional-stakeholder perspective’, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 47–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00582.x

Effendy, T. 2013, ‘Premanisme dan Pembangunan Politik di Indonesia’, Al-Adl: Jurnal Hukum, vol. 5, no. 9, pp. 56-69. https://doi.org/10.31602/al-adl.v5i9.189

Eweje, G. & Palakshappa, N. 2009, ‘Business partnerships with nonprofits: Working to solve mutual problems in New Zealand’, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.192

Freeman, R.E. 1984, Strategic Management. A Stakeholder Approach, Pitman, Boston.

Hamann, R. & Acutt, N. 2003, ‘How should civil society (and the government) respond to “corporate social responsibility”? A critique of business motivations and the potential for partnerships’, Development South Africa, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/03768350302956

Horikoshi, H. 1987, Kyai dan Perubahan Sosial, P3M, Jakarta.

Hudayana, B., Suharko, & Widyanta, A. B. 2020, ‘Communal violence as a strategy for negotiation: Community responses to nickel mining industry in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia’, Extractive Industries and Society, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 1547–1556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2020.08.012

Ihlen, Ø., Bartlett, J. L., May, S. 2011, The Handbook of Communication and Corporate Social Responsibility, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118083246

Jamali, D. & Keshishian, T. 2009, ‘Uneasy alliances: lessons learned from partnerships between businesses and NGOs in the context of CSR’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 84, no. 2, pp. 277–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9708-1

Jannah, H. 2015, Kyai, Perubahan Sosial dan Dinamika Politik Kekuasaan, Fikrah: Jurnal Ilmu Aqidah dan Studi Keagamaan, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 157-176. https://www.neliti.com/publications/177934/kyai-perubahan-sosial-dan-dinamika-politik-kekuasaan

Katz, D. & Kahn, R. L. 1966, The Social Psychology of Organizations, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Keller, S. 1995, Penguasa dan Kelompok Elit: Peranan Elit-Penentu dalam Masyarakat Modern, Raja Grafindo Perkasa, Jakarta.

Kemp, D. 2010, ‘Mining and community development: Problems and possibilities of local-level practice’, Community Development Journal, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 198–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsp006

Kim, J., Kim, H. J., & Cameron, G. T. 2009, ‘Making nice may not matter: The interplay of crisis type, response type and crisis issue on perceived organizational responsibility’, Public Relations Review, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 86–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.09.013

Kirat, M. 2015, ‘The Islamic roots of modern public relations and corporate social responsibility’, International Journal of Islamic Marketing and Branding, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 97-112. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIMB.2015.068144

Kloppers, E. 2017, ‘Empowering through CSR: Communication between CSR facilitators and beneficiaries’, In Einwiller, S., Weder, F., & Eberwein, T. (eds), CSR Communication Conference 2017 Proceedings: The 4th International CSR Communication Conference, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, September 21-23, p. 23. https://csr-com.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/csrcom-proceedings-2017.pdf

Koleva, P., Meadows, M., & Elmasry, A. 2023, ‘The influence of Islam in shaping organisational socially responsible behaviour’, Business Ethics, the Environment and Responsibility, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 1001–1019. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12529

Kotler, P. & Lee,N 2005, Corporate Social Responsibility: Doing the Most Good for Your Company and Your Cause, John Wiley & Sons Inc. Hoboken, NJ.

Kwestel, M. & Doerfel, M. L. 2023, ‘Emergent stakeholders: Using multi-stakeholder issue networks to gain legitimacy in corporate networks, Public Relations Review, vol. 49, no. 1, article 102272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2022.102272

Ligeti, G. & Oravecz, Á. 2009, ‘CSR communication of corporate enterprises in Hungary’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 84, no. 2, pp. 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9678-3

Lock, I. 2017, ‘The issue of credibility for oil and gas industry’s CSR reporting. A stakeholder perspective’, In Einwiller, S., Weder, F., & Eberwein, T. (eds), CSR Communication Conference 2017 Proceedings: The 4th International CSR Communication Conference, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, September 21-23, pp. 28-30. https://csr-com.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/csrcom-proceedings-2017.pdf

Lock, I. & Schulz-Knappe, C. 2019, ‘Credible corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication predicts legitimacy: Evidence from an experimental study’, Corporate Communications, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-07-2018-0071

Lock, I. & Seele, P. 2016, ‘The credibility of CSR (corporate social responsibility) reports in Europe. Evidence from a quantitative content analysis in 11 countries’, Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 122, pp. 186-200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.060

Ma, L. & Bentley, J. M. 2022, ‘Can strategic message framing mitigate the negative effects of skeptical comments against corporate-social-responsibility communication on social networking sites?’, Public Relations Review, vol. 48, no. 4, article 102222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2022.102222

Maryani, E. & Darmastuti, R. 2017, ‘The “Bakul Gendong” as a communication strategy to reject the construction of a cement factory in Central Java’, Public Relations Review, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.10.020

Mazereeuw-van der Duijn Schouten, C., Graafland, J., & Kaptein, M. 2014, ‘Religiosity, CSR attitudes, and CSR behavior: An empirical study of executives’ religiosity and CSR’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 123, no. 3, pp. 437–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1847-3

McWilliams, A. & Siegel, D. 2006, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective’, Academy of Management Review, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 117-127. https://doi.org/10.2307/259398

Millar, C. C. J. M., Choi, C. J., & Chen, S. 2004, ‘Global Strategic Partnerships between MNEs and NGOs: Drivers of Change and Ethical Issues’, Business and Society Review, vol. 109, no. 4, pp. 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0045-3609.2004.00203.x

Moreno, A. & Capriotti, P. 2009, ‘Communicating CSR, citizenship and sustainability on the web’, Journal of Communication Management, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632540910951768

Morsing, M. 2006a, ‘Corporate social responsibility as strategic auto-communication: on the role of external stakeholders for member identification’, Business Ethics: A European Review, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2006.00440.x

Morsing, M. 2006b, ‘Strategic CSR Communication: Telling Others How Good You Are’, In Jonker, J. & Witte, M. (eds), Management Models for Corporate Social Responsibility, Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 238-246. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-33247-2_29

Muniapan, B. & Raj, S. J. 2014, ‘Corporate social responsibility communication from the vedantic, dharmic and karmic perspectives’, In Tench, R., Sun, W., & Jones, B. (eds), Critical Studies on Corporate Responsibility, Governance and Sustainability, Emerald Publishing, Leeds, pp. 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2043-9059(2014)0000006001

Mzembe, A. N. 2016, ‘Doing stakeholder engagement their own way: Experience from the Malawian mining industry’, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1353

Mzembe, A.N. & Meaton, J. 2014, ‘Driving Corporate Social Responsibility in the Malawian mining industry: A stakeholder perspective’, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 189–201 https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1319

Nielsen, A. E. & Thomsen, C. 2009, ‘CSR communication in small and medium-sized enterprises: A study of the attitudes and beliefs of middle managers’, Corporate Communications: An International Journal, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280910953852

Parani, R. 2011, ‘Public relations strategies in the implementation of CSR programs in petrochemical mining MNCs in Indonesia’, In Elving, W., Golob, U., Schultz, F., Nielsen, A.-E., Thomsen, C., & Podnar, K. (eds), CSR Communication Conference 2011: Proceedings of the 1st International CSR Communication Conference, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, October 26-28, p. 74. https://csr-com.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/csrcom-proceedings-2011.pdf

Pieczka, M. 2019, ‘Looking back and going forward: The concept of the public in public relations theory’, Public Relations Inquiry, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/2046147X19870269

Rademacher, L. & Remus, N. 2017, ‘Integrated CSR Communication of NGOs: The Dilemma to Communicate and Cooperate in CSR Project Partnerships’, In Diehl, S., Karmasin, M., Mueller, B., Terlutter, R. & Weder, F. (eds), Handbook of Integrated CSR Communication, Springer, Cham, pp. 393–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44700-1_22

Rivera-Santos, M. & Rufín, C. 2010, ‘Odd couples: Understanding the governance of firm–NGO alliances’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 94, no. 1 supplement, pp. 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0779-z

Rohwer, L. & Topić, M. 2019, ‘The communication of Corporate–NGO Partnerships: Analysis of Sainsbury’s collaboration with Comic Relief’, Journal of Brand Management, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-0111-7

Rondinelli, D. A. & London, T. 2003, ‘How corporations and environmental groups cooperate: Assessing cross-sector alliances and collaborations’, Academy of Management Perspectives, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 61–76. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2003.9474812

Saidi, Z. & Abidin, H. 2004, Menjadi Bangsa Pemurah: Wacana dan Praktek Kedermawanan Sosial di Indonesia, Piramedia, Jakarta.

Scandelius, C. & Cohen, G. 2016, ‘Achieving collaboration with diverse stakeholders-The role of strategic ambiguity in CSR communication’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 69, no. 9, pp. 3487-3499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.01.037

Shim, K. J. & Yang, S. U. 2016, ‘The effect of bad reputation: The occurrence of crisis, corporate social responsibility, and perceptions of hypocrisy and attitudes toward a company’, Public Relations Review, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 68-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.11.009

Shodikin, A., & Susetiawan, S. 2020, ‘Advokasi Aliansi Masyarakat Sipil: Kegagalan Merebut Aksesibilitas Pengelolaan Corporate Social Responsibility Melalui Peraturan Daerah’, Journal of Social Development Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.22146/jsds.204

Simanis, E. & Hart, S. 2008, The Base of the Pyramid Protocol: Toward Next Generation BoP Strategy Second Edition, Center for Sustainable Global Enterprise, Ithaca, NY. https://www.globalhand.org/system/assets/6a6f9d74c561c97e1f6f7002c83112132fbf19a0/original/BoPProtocol2ndEdition2008.pdf

Sison, M. D. & Hue, D. T. 2015, ’CSR communication and NGOs: Perspectives from Vietnam’, In: Golob, U., Podnar, K., Nielsen, A., Thomsen, C. & Elving, W. (eds), CSR Communication Conference 2015, Proceedings of the 3rd International CSR Communication Conference, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, September 2015, p. 229.

Sison, M. D. & Panol, Z. 2019, ‘Negotiated and discursive power in South-East Asia: Exploring the “bibingka” model of CSR’, In Morsing, M., Golob, U., & Podnar, K. (eds), CSR Communication Conference 2019, Proceedings of the 5th International CSR Communication Conference, Stockholm School of Economics, Stockholm, September 18-20, 2019, p. 230. https://csr-com.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/csrcom-proceedings-2019.pdf

Stake, R. E. 1994, ‘Case studies’, In Denzin N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (eds), Handbook of Qualitative Research, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 236–247.

Sthapitanonda, P. 2015, ‘“Just do it” vs “Strategic relations with stakeholders”: The challenges communicating CSR in Thailand’, In Golob, U., Podnar, K., Nielsen, A.-E., Thomsen, C., & Elving, W. (eds), International CSR Communication Conference 2015: Conference Proceedings: The 3rd International CSR Communication Conference, University of Ljubljana, September 17-19. https://csr-com.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/csrcom-proceedings-2015.pdf

Tewari, R. & Dave, D. 2012, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility: Communication through Sustainability Reports by Indian and Multinational Companies’, Global Business Review, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/097215091201300303

Thabit, M. & Cision 2015, ‘How PESO makes sense in influencer marketing’, PR Week, June 8. https://www.prweek.com/article/1350303/peso-makes-sense-influencer-marketing

Toker, H. 2013, ‘NGOs and CSR’, In Idowu, S.O., Capaldi, N., Zu, L., & Gupta, A.D. (eds), Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility, Springer, Berlin, pp. 1759-1765. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-28036-8_511

van Aaken, D. & Buchner, F. 2020, ‘Religion and CSR: A systematic literature review’, Journal of Business Economics, vol. 90, no. 5-6, pp. 917–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-020-00977-z

van Huijstee, M. & Glasbergen, P. 2008, ‘The practice of stakeholder dialogue between multinationals and NGOs’, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.171

Verboven, H. 2011, ‘Communicating CSR and business identity in the chemical industry through mission slogans’, Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, vol. 74, no. 4, pp. 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569911424485

Wibisono, Y. 2007, Membedah Konsep dan Aplikasi Corporate Social Responsibility, Fascho Publishing, Gresik.

Wicaksono, A. B. 2022, Premanisme sebagai Sumber Wacana Alternatif Mendulang Kekuasaan: Menelisik Pengaruh Kelompok Preman sebagai Means of Power terhadap Isu Sosial-Politik di Wonosobo, Jawa Tengah, Doctoral dissertation, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Repository UGM. https://etd.repository.ugm.ac.id/penelitian/detail/219200

Yang, A. & Liu, W. 2020, ‘CSR Communication and Environmental Issue Networks in Virtual Space: A Cross-National Study’, Business & Society, vol. 59, no. 6, pp. 1079–1109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650318763565

Yin, R. K. 2009, Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th edn, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

1 SKK Migas is Special Task Force for Upstream Oil and Gas Business Activities in Indonesia. SKK Migas is an abbreviation of Satuan Kerja Khusus Pelaksana Kegiatan Usaha Hulu Minyak dan Gas Bumi.