Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 16, No. 2

2024

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

Cosmopolitanism over Ethnonationalism through Social Movement: The Case of Anti-CAA Movement in India

Terbi Loyi

Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, Maharashtra, India; Pune and Arunachal Pradesh University, Pasighat, Arunachal Pradesh, India

Corresponding author: Terbi Loyi, Pune and Arunachal Pradesh University, Hill Top, Pasighat, East Siang, Arunachal Pradesh, India, terbi24@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v16.i2.8787

Article History: Received 27/08/2023; Revised 02/10/2024; Accepted 08/10/2024; Published 19/11/2024

Citation: Loyi, T. 2024. Cosmopolitanism over Ethnonationalism through Social Movement: The Case of Anti-CAA Movement in India. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16:2, 43–56. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v16.i2.8787

Abstract

Ethnonationalism based on religion has had a significant impact in the modern history of India. While celebrating its diversity as a democratic nation, the country has also witnessed numerous ethnic movements, tensions, violence as well as assertion of cultural and ideological values by one dominant group over another. The ‘State’ often gets involved in these conflicts directly or indirectly. The case of Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) of 2019 is a recent example relating to issues of citizenship and discrimination based on religion that sparked a nationwide movement. The citizens condemned the enactment of CAA as anti-democratic and against the secularistic ideology of India. Drawing upon the case of Anti-CAA movement across India the paper argues that social movements serve as a platform to revisit and realize the ideologies of cosmopolitanism.

Keywords

Cosmopolitanism; Ethnonationalism; Citizenship Amendment Act; National Register of Citizens; India

Introduction

India is renowned for its rich diversity, encompassing cultural, religious, racial, linguistic and geographical landscape. India’s diversity is evident in the different traditions, languages, and cultures that exists along with its diverse religious compositions, comprising of Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, Sikhism, Buddhism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, and Bahaism along with various indigenous belief system. This diversity, however, is not without its problems and has faced numerous challenges in terms of assertions and dominations by the dominant cultures and ideologies, and movements against these assertions by the minority communities. The country has witnessed several conflicts and frictions even with the rights and provisions outlined in the constitution of India1, guaranteeing fundamental rights2 to all citizens regardless of their birth, religion, caste, class, language, and ethnicity.

Religious communalism, ethnic conflicts and movements across India are such examples that have posed a significant threat to India’s democracy after its independence, especially since the 1980s3, making it a complex and sensitive issue. Of the various ethnic movements that took place in India, Dravidianism, Hindu revivalism, Sikh ethnonationalism, Kashmiri ethnonationalism are considered as the major ethnonational movements (Subramanian 2010), the remnants or ideas of which continue to percolate and persist in contemporary society. In the discussion of nationalism in India, Hindu nationalism takes a central stage of being an ethnonationalist project (Baruah 2010; de Souza & Hussain 2022, p. 2). It is considered as ethnonationalist because of its nature of seeking to redefine Indians as ‘Hindu’ based on a territorial, racial, and cultural identity (Bhatt 2001; de Souza & Hussain 2022).

This understanding of Hindu nationalism as ethnonationalist project took centre stage in discussions in the year 2019, because of the enactment of Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in the parliament of India. The enactment of CAA was heavily criticized and protested by the citizens for reflecting the agenda of Hindu nationalism with the intention of reconstructing India as a ‘Hindu Rashtra’ (Hindu Nation). The Hindu Rashtra, according to Kamat & Mathew (2003) is the goal of Hindu nationalist that they try to achieve by fostering solidarity among Hindus based on those who belong to the ‘Hindu family and those outside the fold of ‘Hinduness’ (p. 8). This assessment of CAA along with then ongoing updating of National Register of Citizens (NRC) sparked nationwide movement and protest against it due to its potential implications. The Anti-CAA movement is the site of the study. Taking the example of Anti-CAA movement, the paper argues that social movements provide a space where the ideologies of cosmopolitanism can be revisited, especially in a country with multitude of diversity like India. To do that the paper focuses on the nature of Anti-CAA movement in India and as it was experienced by the citizens. The paper also tries to highlight the idea of cosmopolitanism that exists in India, making it possible for people from diverse communities and ethnicities to exist together. The paper then tries to bring together the data from each section to present the argument that the ideologies of cosmopolitanism can be revisited and realised through movements and protests.

The paper is divided into five sections. The first section focuses on the features of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA)-2019. This section further discusses the Anti-CAA movement that occurred across India. The second section analyses the nature of the Anti-CAA movement in the rest of India and in the Northeast of India. This section therefore, first discusses the then upgrading process of National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam, which is linked to the Anti-CAA sentiment in the Northeast of India. The section tries to bring out the complex interplay of politics of citizenship and CAA highlighting the insecurities and anxieties in northeast. The third section focuses on the question of national identity and ethnonationalism nature of CAA. The fourth section discusses Indian cosmopolitanism and the cosmopolitan ideology of the people and groups in the movement against CAA. That section is followed by a conclusion.

I. The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) 2019

Provided that any person belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian community from Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Pakistan, who entered into India on or before the 31st day of December 2014 and who has been exempted by the Central Government by or under clause (c) of sub-section (2) of section 3 of the Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920 or from the application of the provisions of the Foreigners Act, 1946 or any rule or order made thereunder, shall not be treated as an illegal migrant for the purposes of this Act;

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt. of India

On 12 December 2019, the Indian parliament received the President’s assent for the Citizenship Amendment Act 20194. This amendment modified the Citizenship Act of 19555 to expedite the citizenship process for persecuted religious minority groups from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh. The amendment stated that the undocumented Hindu, Jain, Sikh, Buddhist, Christian and Parsi immigrants who entered India before 31 December 2014 would no longer be considered illegal6. The amendment also stated that the process of getting Indian citizenship would also be processed quickly7 for these undocumented immigrants. The Act however excluded Muslims and Jews from this provision which led to the Anti-CAA movement across India. A widespread Anti-CAA protests started as people condemned it as discriminatory and against the country’s secular principles that directs the State to treat all religions equally. Various student groups, politicians, and activists participated in these protests, leading to the Anti-CAA protests throughout India.

Anti-CAA movement: The period from 1 December 2019 to 20 March 2020, witnessed a series of protests against CAA from every part of India, gaining global attention. The movement against CAA saw participation from a diverse group of individuals, including students, youths, women, intellectuals, minorities, tribals, and dalits, as well as individuals from upper castes and middle/upper middle classes (Srikanth 2020). It started in Assam a day before the Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB)8 was introduced in the lower house of the Indian Parliament. On 4 December 2019, shortly after the Union Cabinet cleared the Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) for introduction in the Parliament, several organisations in Assam and other states in the Northeast called for a bandh9 on December 9 and 10 (Ranjan & Mittal 2023). The protest was led by individuals identifying themselves as ‘indigenous’ or ‘native’ to the region, as well as migrants settled in the region for a longer period of time. Across the country, it is found that there were over 600 anti-CAA protests, which attracted a diverse range of individuals, particularly Muslim women (Lokur et al. 2022, p. 18; Srikanth 2020).

The anti-CAA protests that started in Northeast India sparked a series of demonstrations in Delhi and a brutal police attack on students at Jamia Millia Islamia University protesting against the Citizenship Amendment Act (Shivaprasad 2021, p. 138). These protests quickly spread to Aligarh Muslim University and Jawaharlal Nehru University, and gained support from students at various central and state universities, and Institutes of Managements and Technologies. On 19 December 2019, a nation-wide bandh was called by opposition political parties to protest against CAA, and many citizens joined the anti-CAA movement to condemn the divisive and discriminatory politics that threaten the ‘Idea of India’ as a secular and democratic republic (Srikanth 2020).

These protests resulted in a significant women-led demonstration in Shaheen Bagh10 against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) that started on 15 December 2019, and lasted over 100 days until the lockdown was enforced due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Indian Muslim women led the movement, with individuals from various religious and social backgrounds joining them (Salam 2023).

Uttar Pradesh was the state most severely impacted by police brutality during the anti-CAA protests. The violence in the state led to the deaths of at least 23 Muslim men, with 22 succumbing to gunshot injuries. Some individuals who had been shot but survived were arrested months later under the ambiguous category of ‘unknown protestors’ (Kaiser & Jaffrelot 2023). The anti-CAA protest turned violent in northeast Delhi in February 2020 where it was found that mobs led by Hindu nationalists, including BJP cadres, arrived from various regions to aid local activists. The citizens committee report on the violence in Northeast Delhi led by judges of the Supreme Court and High Court of India and a retired Home Secretary, reflected in their report that the Delhi Police affidavit of July 2020 reports around 185 houses, 468 shops, 747 vehicles, 60 hand-carts, and two horse-drawn carts were burned, and looted selectively during the Northeast Delhi violence. Mosques and temples were reported to be desecrated and damaged11. The official death toll was reported to be 53, of which 40 of the deceased were identified as Muslims and 13 were identified as Hindus (Lokur et al. 2022, pp. 65-66). The communal violence in New Delhi initially began on February 23 as a confrontation between groups supporting and opposing the Citizenship Amendment Act. It quickly morphed into battles between Hindu and Muslim groups, which the police were unable to immediately stop. After the CAA was passed, it is estimated that a total of 83 people were killed in protests and riots related to the CAA in Assam, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Meghalaya and Delhi (Singh 2021)12.

II. Anti-CAA movement and NRC in Northeast India and the Rest of India

National Register of Citizens: The National Register of Citizens (NRC) is the Government of India’s attempt to update the records of legal citizens in India, including their names, photos and residential addresses. The NRC was first prepared in Assam based on the 1951 census13 data, but it was not updated after that. The updating of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) was initiated again in 2013 in all parts of Assam under the supervision of the Registrar General of Citizen Registration (RGI) in accordance with the Citizenship Act of 1955 and Citizenship Rules of 200314 (Press Information Bureau 2018)15. Assam was the only Indian state where the updating process of NRC was implemented. The major objective of the NRC update was to identify undocumented immigrants from Bangladesh who had migrated to Assam after the 1947 and 1971 war between Bangladesh and Pakistan (The Governor of Assam 1998)16. The process of updating of NRC which began in 2013, concluded in 2019, resulting in the exclusion of approximately 1.9 million people, or 6% of Assam’s population (Tewari 2019; Sufian 2020; Scroll 2019) from the citizenship registry of India. A significant proportion of those included Muslims, while many Bengali Hindus were also left out. This resulted in many individuals becoming stateless.

The updating of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) was initiated in the year 2013 in Assam, after a petition was filed by an NGO named Assam Public Works (APW) in 2009 at the Supreme Court of India. The petition was filed requesting an updating or re-verification of NRC and deletion of foreigners’ name in electoral rolls17. In 2012 Assam Sanmilita Mahasangha along with various indigenous groups filed another writ petition18 at the Supreme Court requesting to repeal the Section 6A19 of the Citizenship Act, 1955. Section 6A of the Citizenship Act 1955, provides undocumented immigrants from Bangladesh to have citizenship of India, given they arrived in India prior to January 1966. In the case where they have arrived between January 1966 and March 1971, they would be registered as citizens of India after 10 years of their stay in India. For those arriving after 1971, it was stated that they would not be eligible for citizenship. The writ petition to repeal the Section 6A of the citizenship Act was supported by the All Assam Students Union (AASU) and most of the ethnic organisations in Assam. The AASU had been advocating against the immigration of migrants to Assam, popularly known as Assam Movement/Assam Agitation, which lasted for six years, starting from the year 1979 to 1985. AASU, along with the All Assam Gan Sangram Parishad (AAGSP)20, had staged electoral boycott, and protests on streets demanding to detect, disenfranchise and deport foreigners from Assam (Ranjan 2019, p. 4). The result of these protest and movement led to the signing of Assam Accord21 on August 15, 1985, outlining measures against migrant rights in the regions (Press Information Bureau 2018). The Assam Accord is a Memorandum of Settlement (MoS) between the Central Government, State Government, All Assam Students’ Union (AASU), and All Assam Gan Sangram Parishad (AAGSP), which is a six-year agitation that started in 1979. The accord was prepared aiming to resolve the long-standing issues of undocumented immigration from Bangladesh to Assam. The key points of the accord included the identification and deportation of undocumented immigrants and securing of the international border to prevent future infiltration.

After the NRC updating process was completed in 2019, 1.9 million people in Assam were recorded as ‘foreigners.’ The result of updating did not meet the expectations of the organisations who had called for updating of NRC in the Northeast, contradicting their belief that more than 10 million Bangladeshis had settled in Assam and other Northeastern regions. As a result, some of the organizations in Assam began advocating for a new NRC22. Additionally, various indigenous civil society organizations in the northeast called for similar exercises in their states. This call for updating of NRC was further intensified in the Northeast region after the enactment of CAA which expedited the Indian citizenship process of immigrants belonging to religions like Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism. It was feared that the immigrants who were recorded as ‘Muslim foreigners’ in the updating process of NRC would apply for Indian citizenship by converting their religion or calling themselves a follower of Hinduism or any religion that benefits from CAA. Another fear was that the recorded foreigners from Bangladesh following Hinduism that had come to India after the year 1971 and were residing in Assam or any Northeast Indian states would be given Indian citizenship. These implications of the enactment of CAA when studied together with the NRC in Assam led to the start of Anti-CAA protest in Assam that later on spread all over India.

Anti-CAA sentiment in rest of India and Northeast: The anti-CAA sentiment in the rest of India stemmed from the sense of upholding the constitution of the country that gives equal rights and freedom to the people belonging from any religion. CAA, therefore, was argued as unconstitutional and anti-Muslim. It was also feared that CAA coupled with NRC could lead to removal of Muslim citizens without proper documents. CAA was called violative and discriminatory of the basic structure of constitution that values equality under law of secularism (Saha et al. 2019). The Anti-CAA sentiment in northeast India in this case is identified to be linked to the NRC, as the CAA proposes a cut-off date of 31 December 2014, for granting citizenship to non-Muslim immigrants and refugees (Srikanth 2020). The implementation of this provision would conflict with clause 5.8 of the Assam Accord, which states that ‘Foreigners who came to Assam on or after March 25, 1971, shall continue to be detected, deleted, and practical steps shall be taken to expel such foreigners’ (Problems of Foreigners in Assam p. 1)23. This variations in stand on CAA by protestors in Northeast India from the rest of India was found to be rooted in the history of insecurities and anxieties as experienced by the people of Northeast India.

North-East India: Insecurities and Anxieties

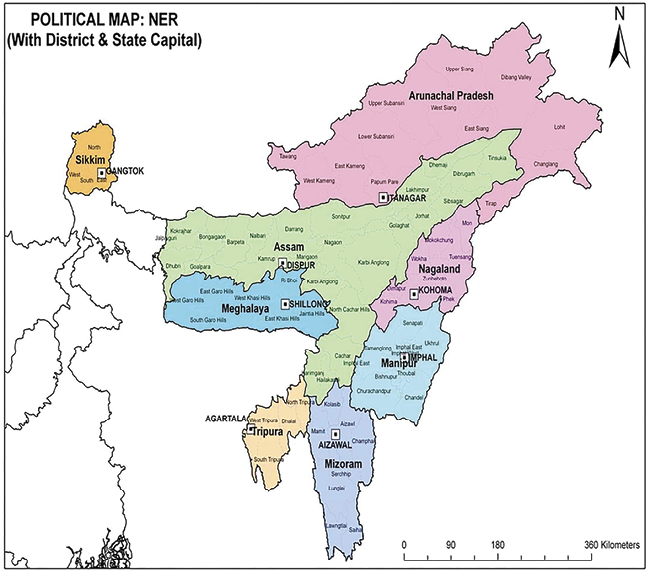

The Northeast India consists of eight states, including Tripura, Sikkim, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Manipur, Mizoram, and Nagaland is a predominantly indigenous/tribal region. The region is renowned for its ethnic diversity, with more than 200 tribes sharing international borders with China, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Bhutan. The region has experienced continuous and consistent migration both before and during the British colonial era. Following the separation of Bangladesh from Pakistan in 1971, the Northeastern states witnessed substantial migration into their territories. The United Nations Human Commissioner for Refugees reported that approximately 7.5 to 8.5 million individuals crossed the Indian border, with a significant number of them seeking refuge in Assam (Ranjan 2019, p. 4). This migration differed from previous waves, complicating the distinction between migrants and refugees. This time the migrants arrived in an already established and assimilated region of Northeast that was recognized politically as part of the Indian State. This region is now included in the constitution of the Indian State and governed by written laws and a governing authority that apply equally to all citizens. The growing political assimilation of the Northeast region into India resulted in numerous changes to everyday life and the governing system, including the transfer of authority from local communities, King, Chief, or a clan leader to the national government, a governing authority that follows a written constitution where the laws and governance system are equal for everyone who is a citizen of the Indian State.

Figure 2. Map of North East India

The influx of migrants in the Northeast led to the feelings of insecurity and territorial anxiety among the region’s residents. According to the 2011 census report on migration, there were 14.9 million migrants in the Northeast, accounting for approximately 33% of the region’s total population. This represents an increase of about 5.0 million migrants since the 2001 census. Tripura, for example, has experienced a significant influx of non-tribals, with only 31% of the state’s population representing 19 indigenous communities. In contrast, the non-tribal population, predominantly Bengalis, comprises approximately 69.95% of Tripura’s inhabitants, making the indigenous tribes a minority both in terms of population and culture.

CAA therefore, in the case of Northeast India was understood as anti-indigenous. CAA’s emphasis on granting of Indian citizenship based on religions like Hinduism and other minority religions is argued as undermining the Assam Accord and the NRC. It was also argued to be demonstrating ethnonational vision of Hindu Rashtra or Akhand Bharat (Greater India) which is fraught with territorial anxieties in Northeast due to the stark difference in the cultures of the northeast with those of heartlands in India (Longkumer 2020).

III. CAA, Ethnonationalism and National Identity

The CAA faced criticism for potentially undermining India’s secular foundations and promoting ethno-nationalism. The Citizenship Amendment Act represents a significant shift in the definition of citizenship in India and has been viewed as a means to advance the concept of Hindu Rashtra, recasting India as a Hindu nation with citizenship determined by ethno-nationalist criteria. Ahmad (2020) argues that CAA is an attempt to legally solidify the project of making India a Hindu nation-state (rashtra). In a country with diverse ethnicities existing together, ethnonationalism in the context of CAA is played out by trying to define cultural identity of various communities from diverse religious background in terms of Hinduism. CAA and NRC are initiatives that deals with the question of citizenship and national identity.

Examining national identity is a difficult task. Marschelke (2021) presents three difficulties when examining ‘national identity’. First, the term consists of two concepts, namely ‘nation’ and ‘identity,’ which in itself is very broad, transdisciplinary and controversial in nature. These two concepts cannot be analysed and understood without related concepts like nationalism, ethnicity, culture and so on. The second challenge is to acknowledge that the term ‘national identity’ is used in various contexts, including academic discourse, political discussions, and everyday conversations. Third is that the idea of nationalism has proven adaptable, finding support across various ideologies, including liberalism, conservatism, Marxism, fascism, racism, imperialism, secessionism, anti-imperialism, and anti-colonialism over time.

For this paper, the national identity is analysed in the context of ethnonationalism in India which is utilized in the political arena and everyday discourse to denote and identify those ‘who belongs’. Ethnonationalism encompasses a broad range of political phenomena, including what may be known as nationalism, separatism, secessionism, sub-nationalism, ethnic insurgency, ethnic militancy, or sometimes simply regionalism (Subramanian 2010).

Varshney (1993), in his article, ‘Contested Meanings: India’s National Identity, Hindu Nationalism and the Politics of Anxiety,’ argued that there has always been a conceptual space for Hindu nationalism in the imagination of India’s national identity. However, he also acknowledges that Hindu nationalism emerged as an institutional and ideological alternative in response to the various separatist agitations in the 1980s. Varshney further posits that three competing narratives about India have vied for political supremacy since the inception of the Indian anti-colonial movement. These narratives include i) national unity or territorial integrity, ii) cultural or political pluralism, and iii) religious or Hindutva or political Hinduism (pp. 234-235). The aforementioned themes extend to the pursuit of Hindu nationalism by Hindu nationalists, who envision two impulses: i) building a united India and ii) ‘Hinduizing’ the polity and the nation. While Muslims and other groups are not excluded from the definition of India, inclusion is contingent upon assimilation, which entails ‘acceptance of the political and cultural centrality of Hinduism’ (Varshney 1993, p. 232).

The discussion on Indian nationalism, highlights that Hindu nationalism holds a very tight grip on India’s political and cultural dimension as a nation. The passing of the Citizenship Amendment Act and implementation of the National Register of Citizens looked like the Centre’s extension of the imagined nation of Hindu nationalism, undermining the importance of other existing religions, cultures and identity, and asserting an ethnic definition of nationality. The government and legislative bodies that are instrumental in shaping national identity were questioned for their ethnonationalist agenda. The CAA movement which is reflected as a movement against an ethnonationalist agenda of the State is understood as a movement to protect and uphold the secular nationalism of India, which aims to uphold India’s geographical and cultural diversity.

IV. Social Movement and Indian Cosmopolitanism

The Covid-19 pandemic that struck the world in 2019 and the imposition of lockdowns and health casualties greatly impacted the Anti-CAA movement. The protests that were going on in different sites in India were effectively halted by the Covid-19 pandemic. On 28 July 2023, there was a request for an extension of six months by the central government to frame the rule of the Citizenship Amendment Act for its implementation. This was the seventh extension that the government obtained from the Supreme Court because of the Covid-19 pandemic that delayed the process (Singh 2023). The Anti-CAA movement, however, could not gain its momentum after the Covid-19 pandemic. On 11 March 2024, CAA was notified and implemented in the nine states of India namely Rajasthan, Gujarat, Haryana, Chhattisgarh, Punjab, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi and Uttar Pradesh. The move was called an electorate exercise before the general elections in India that was held from 19 April 2024 to 1 June 2024. The NRC faced criticism for exercising institutional exclusion. With all these cases, controversies over financial anomalies and bureaucratic lapses24 in the NRC process also appeared in the Comptroller and Auditor-General of India (CAG) report. The CAG report of 2022 pointed out that the software used to prepare the NRC was faulty. The report reads that ‘in the NRC updating process, a highly secure and reliable software was required to be developed; audit, however, observed lack of proper planning in this regard to the extent of 215 software utilities added in a haphazard manner to the core software (p. xi)’. The result is that NRC is yet to be notified by the Registrar General of India (RGI), and it has not been implemented anywhere in India, and many consider NRC as dead.

The Anti-CAA-NRC exemplifies the intricate nature of social movements and the challenges that can arise in a culturally diverse nation. It is, therefore, crucial to consider the insecurity, vulnerability, and anxiety experienced by a group when evaluating or analysing any social movement. Although the movement against the CAA in the Northeast aligned with the rest of India, the people’s perspectives and situatedness in Northeast India and the rest of India differed. The objective was unified—to prevent the Citizenship Amendment Act from being passed and implemented—but individual goals varied.

Indian cosmopolitanism or cosmopolitan ideology is rooted in its tolerance and acceptance i.e. ‘open-mindedness towards other cultures, values, beliefs, and nationalities’ (Bharati 2009, p. 65), and marginal groups. The Indian cosmopolitanism is also reflected in the secularistic nature of its constitution. Even though the Anti-CAA movement could not achieve its goal, the movement showcased the cosmopolitan nature of the people by trying to uphold the constitution and demanding inclusion and equality of all religions.

The closer analysis of Anti-CAA movements shows that the movements were motivated by the sentiment of maintaining the secular aspects of the country and the cosmopolitan definition of nationality, that defines its long-standing history of living together even with the multitude of diversities. The mobilisation of the people, students and women protestors from different social backgrounds and the use of different types of protest in different parts of the country in their movement against the Act provided them a site, where the protestors could relay their disagreements. The larger mobilisation against CAA and NRC from all over the country especially by the students in universities and women was their method of showing their cosmopolitan ideologies using slogans and placards to include all the religions in the provisions of the CAA. The protestors outside of Northeast saw CAA and NRC as unconstitutional and a form of religious discrimination towards a particular religion, in this case Islam. Srikanth (2020) argues that the mobilisation against CAA and NRC and the Muslims’ upsurge emanates not only from the perception that the CAA is discriminatory, but also out of the fear that the CAA is a prelude to an NRC, wherein they would be forced to prove their identity as citizens of India.

The analysis of Anti-CAA movement in Northeast India, however, show the anti-migrant sentiment from the indigenous communities which can be substantiated from their support for the NRC. Understanding cosmopolitanism in the context of Northeast India where diverse ethnic communities exist together and where demands or retaliation for non-inclusion of immigrants is strongly demanded can be understood through the insecurities, territorial anxieties and tribal migrations of the people to other states in India. The states in the Northeast India as discussed earlier experienced a continuous and consistent migration both before and during the British colonial era. The Northeast witnessed migration from various ethnic groups, including people from Tibet, Burma, Thailand, Bangladesh, and West Bengal in India, at different times throughout history. Some of these migrants have assimilated into the local communities over extended periods. However, the rapid influx of migrants shortly after India gained independence and control of the area has led to significant tensions with the indigenous population (Inoue 2005). This influx of people that are different from indigenous people of the region overpowered the indigenous groups in terms of numbers and representations in the political and economic affairs, leaving the indigenous people as the minority in their own land, leading to the fear of insecurities and anxiety among the indigenous people. The tribal population feared being overpowered and outnumbered by outsiders, along with the insecurity about losing their lands, resources, culture, and identity due to the potential demographic change, like that of Tripura. However, there is also an attempt to gain cosmopolitan features by the tribals which is reflected in increasing number of out-migrations from the northeast region by the tribals. Migration is significant here as it involves ‘engagement with mainstream India in contrast to the anti-India underpinnings of social and political life in the Northeast itself (McDuie-Ra 2012), making a person belonging to two distinct communities: the local and the wider ‘common’ (Delanty & Močnik 2015).

The Northeast region unlike the popular belief of uninviting of people from other regions and ethnicity, have in fact been accommodative of people and groups settling in the region, especially after India’s independence. There exists a tolerance and common understanding of not disturbing other communities in the region. The cosmopolitan understanding of Northeast in this case is therefore overshadowed by their insecurities and anxieties leading to the demand of upgradation of NRC and protest against CAA. The indigenous or tribals in Northeast believed that the CAA would legitimise foreigners living in different regions in Northeastern states thereby facilitating the entry of migrants from Bangladesh into the entire region. A narrative collected by Singh (2010) from a former president of All Arunachal Pradesh Students’ Union, (AAPSU) Itanagar, which states ‘we do not oppose their request for citizenship, but rather the idea of their long-term settlement on our land. We will not permit the Indian government to have its way in this matter. This is a matter of our survival; the survival of our indigenous communities’ (p. 2) gives insights into the scenario, where it is often relied that they do not have issues with the immigrants getting Indian citizenship but they have issue with immigrants settling permanently in their region.

This section, therefore, answers the question of why Northeastern states of India protested against CAA and not against NRC by discussing the nature of CAA and NRC and how each was perceived and interpreted by the citizens of Northeast India and the rest of India. The states in Northeast India opposed the CAA but did not oppose the NRC because they saw existing migrants as threatening to the identity, language and culture of the indigenous communities (Parthasarathy 2020; Nepram 2019). Their opposition to the CAA was consistent with this position. The press reported that ‘protests have been ongoing in Assam since 10 December 2019 against the Citizenship Act’ (Sarma 2020), claiming that if the CAA had become operational, Assam would have had to accept (non-Muslim and non-Jewish) immigrants who had entered the country between 1971 and 2014. This would have rendered the Assam Accord ineffective (Pisharoty 2019). It is also important to remember that most of the Northeastern states and their history of assimilation into the larger Indian nation is very different from the rest of the country.

V. Conclusion

The Anti-CAA movement shows that social movements have the potential to provide a space where the citizens can revisit and realise the values of cosmopolitanism. A social movement in an ethnonational diverse space provides citizens with a platform to raise their disagreement with the legislature and the State. As in the case of CAA, that is accused of being an ethnonational project that the State is legalising, the core ideas of cosmopolitanism as being tolerant, accepting, and having respect for different beliefs, cultures, values and nationalities faiths were highlighted and reminded to the State and other citizens by the actors of the Anti-CAA movement. Indian understanding of cosmopolitanism, therefore, can be understood in its tolerance and acceptance of other cultures, beliefs, values and nationalities. In a multi-ethnic country like India where various religions, beliefs, cultures and ethnicities exist together, upholding the secular values of the Indian constitution in the form of social movement can also be understood as representing the cosmopolitan values and ideologies of India.

The Anti-CAA movement also reflected the dynamics of cosmopolitanism in the case of Northeast India. The case of Northeast India presents that the idea of cosmopolitanism exists when it comes to the movement of people as in out-migration from the region due to armed conflicts in their region for better educational facilities or job opportunities. However, in terms of sharing of their land and resources, it is a reminder for them of the potential loss of their land and resources, and domination of the migrants in their region and the marginalization of the tribals by the migrants in their own land.

As previously discussed, the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) was notified and implemented on March 11, 2024, in nine states of India. However, in the case of Northeast India, following substantial protests against the Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) and CAA, it was declared that states requiring the inner line permit25 (ILP), such as Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Manipur, as well as states with provisions under the sixth schedule26 including the tribal areas of Assam, Tripura, and Meghalaya, would be exempted from the implementation of the CAA. These exemptions demonstrate the implicit recognition and contribution of Northeastern states as significant actors in the movement against CAA, which the State deemed necessary to bring under control. Due to the insecurities and uncertainties surrounding identity and control over resources, the Northeast region can be characterized as an area with volatile identities held together by the broader interest of peaceful coexistence. The anti-CAA movement in the case of Northeast, therefore, highlights the importance of understanding the frontier regions, their situations, and their contributions to the Indian understanding of cosmopolitanism.

References

Ahmad, I. 2020, Citizen Amendment Act is Confirmation of India as a Hindu Nation-State, Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs. https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/responses/citizen-amendment-act-is-confirmation-of-india-as-a-hindu-nation-state

Baruah, S. 2010, Ethnonationalism in India: A reader, Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

Bharati, R. 2009, ‘Cosmopolitanism, globalization and local administration in India’, The Indian Journal of Political Science, vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 65-75. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41856496

Bhatt, C. 2001, Hindu Nationalism: Origins, Ideologies, and Modern Myths, Berg Publishers, Oxford.

Caraus, T. & Parvu, C.-A. 2019, ‘Cosmopolitanism and migrant protest’, In: Delanty, G. (ed), Routledge International Handbook of Cosmopolitanism Studies, 2nd edn, Routledge, London, pp. 419-429. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351028905-37

de Souza, R. & Hussain, S. A. 2023, ‘“Howdy Modi!”: Mediatization, Hindutva, and long distance ethnonationalism’, Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 138-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2021.1987505

Delanty, G. & Močnik, Š. 2015, Cosmopolitanism [Dataset]. In Oxford Bibliographies Online Datasets. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199756384-0133

Fine, R. 2007, Cosmopolitanism, Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203087282

Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, Press Information Bureau 2018, ‘Cabinet approves revised cost estimates of the scheme of updating of National Register of Citizens, 1951 in Assam’. https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=178400

Government of India, Ministry of Law and Justice 2019. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, Circular no. 47, India. https://www.thehinducentre.com/resources/article30327304.ece/binary/214646.pdf

Governor of Assam 1998, Illegal Migration into Assam, South Asia Terrorism Portal, Institute for Conflict Management, November 8, Retrieved 2023-08-02. https://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/states/assam/documents/papers/illegal_migration_in_assam.htm

Inoue, K. 2005, ‘Integration of the North East: The state formation process,’ In Murayama, M., Inoue, K., & Hazarika, S. (eds): Sub-Regional Relations in the Eastern South Asia: with Special Focus on India’s North Eastern Region, Joint Research Program Series, No. 133, Institute of Developing Economies, Tokyo, pp. 16-30. https://www.ide.go.jp/library/English/Publish/Reports/Jrp/pdf/133_3.pdf

Kaiser, N. & Jaffrelot, C. 2023, ‘Three years since anti-CAA protests: Law and lawlessness’, Indian Express, January 31, Retrieved 2024-01-31. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/three-years-since-anti-caa-protests-law-and-lawlessness-8394755/

Kamat, S. & Mathew, B. 2003, ‘Mapping political violence in a globalized world: The case of Hindu nationalism’, Social Justice, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 4–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29768205

Lokur, M.B. et al. (2022) Uncertain justice: A Citizens Committee report on the North East Delhi violence 2020 Constitutional Conduct Group. Constitutional Conduct Group.

Longkumer, A. 2020, ‘Anti-Indigenous sentiment in the Citizenship Amendment Act’, Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs, March 9. https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/responses/anti-indigenous-sentiment-in-the-citizenship-amendment-act

McDuie-Ra, D. 2012, ‘Cosmopolitan tribals: Frontier migrants in Delhi’, South Asia Research, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/026272801203200103

Marschelke, J. 2021, ‘National identity’, In: Sellers, M. & Kirste, S. (eds), Encyclopedia of the Philosophy of Law and Social Philosophy, Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6730-0_324-1

Nepram, B. 2019, ‘Manufacturing citizenship: The ongoing movement against Citizenship Amendment Bill in Northeast India’, Institute for the Study of Human Rights, February 18, Retrieved 2023-06-08. https://blogs.cuit.columbia.edu/rightsviews/2019/02/18/manufacturing-citizenship-the-ongoing-movement-against-citizenship-amendment-bill-in-northeast-india/

Parthasarathy, D. 2020, ‘Citizenship (Amendment) Act: The pitfalls of homogenising identities in resistance narratives’, Economic and P litical Weekly (Engage), vol. 55, no. 25, Retrieved 2023-06-25. https://www.epw.in/engage/article/citizenship-amendment-act-pitfalls-homogenising-identities-resistance-narratives

Pisharoty, S. 2019, Assam: The Accord, The Discord, Penguin Random House, Gurgaon.

Ranjan, A. 2019, ‘National register of citizen update: History and its impact’, Asian Ethnicity, pp. 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2019.1629274

Ranjan, A. & Mittal, D. 2023, ‘The Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the changing idea of Indian citizenship’, Asian Ethnicity, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 463-481. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2023.2166460

Saha, R., Sarin, A., Varma, P., Turaha, R. M., & Ranganathan, K. et al. 2019, ‘Protest against the CAA’, Economic and Political Weekly (Engage), vol. 54, no. 50. https://www.epw.in/journal/2019/50/letters/protest-against-caa.html

Salam, Z. U. 2023, Being Muslim in India: A Critical View, HarperCollins, Noida.

Sarma, 2020, ‘Anti-CAA protests and state response in Assam: Identity issues challenge Hindutva-based politics’, Economic and Political Weekly (Engage), vol. 55, no. 14. https://www.epw.in/engage/article/anti-caa-protests-and-state-response-assam

Scroll 2019, ‘More than 19 lakh people excluded from Assam’s final NRC; BJP, Congress disappointed’, August 31, Retrieved 2023-08-05. https://scroll.in/latest/935747/assams-final-national-register-of-citizens-will-be-published-today

Shivaprasad, M. 2021, ‘Protest and Performance: My Engagement with the Anti-CAA-NRC Protests in India’, Journal of Feminist Study in Religion, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 137-141. https://doi.org/10.2979/jfemistudreli.37.2.11

Singh, D. 2010, Stateless in South Asia: The Chakmas between Bangladesh and India, Sage Publications, New Delhi. https://doi.org/10.4135/9788132104940

Singh, V. 2021, ‘Two years after CAA was passed, rules governing it yet to be notified’, The Hindu, December 9, Retrieved 2024-01-10. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/two-years-after-caa-was-passed-rules-governing-it-yet-to-be-notified/article37916342.ece

Singh, V. 2023, ‘Centre seeks six more months to frame Citizenship Amendment Act rules’, The Hindu, January 8, Retrieved 2023-07-20. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/home-ministry-seeks-another-extension-of-six-months-to-frame-caa-rules/article66350317.ece

Skrbiš, Z. & Woodward, I. 2013, Cosmopolitanism: Uses of the Idea, Sage Publications, London. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446288986

Srikanth, H. 2020, ‘Three Streams in the Anti-CAA Movement’, The India Forum, January 14, Retrieved 2024-02-10. https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/three-streams-anti-caa-movement

Subramanian, N. 2010, ‘Ethnicity and Pluralism: An Exploration with Reference to Indian Cases’, In: Baruah, S. (ed), Ethnonationalism in India: A Reader, Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

Sufian, A. 2022, ‘Geopolitics of the NRC-CAA in Assam: Impact on Bangladesh–India Relations’, Asian Ethnicity, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 556-586. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2020.1820854

Tewari, R. 2019, ‘With Assam NRC, the truth is also out — it was a pointless exercise all along’, The Print, August 31, Retrieved 2023-07-05. https://theprint.in/opinion/with-assam-nrc-the-truth-is-also-out-it-was-a-pointless-exercise-all-along/284929/

The Times of India 2023,‘Citizenship Amendment Act and its shadow on northeast politics’, February 13, Retrieved 2023-07-25. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/elections/assembly-elections/tripura/news/citizenship-amendment-act-and-its-shadow-on-northeast-politics/articleshowprint/97851232.cms

Varshney, A. 1993, Contested Meanings: India’s National Identity, Hindu Nationalism and the Politics of Anxiety, Center for International Affairs Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

1 Following the independence in 1947, India adopted its constitution on November 26, 1949, which became effective from January 26, 1950.

2 The Constitution of India, Part III- Fundamental Rights (General). Article 12-35 guarantees basic human rights to every citizen of India. They are: Right to Equality, Right to Freedom, Right against Exploitation, Right to Freedom of Religion, Cultural and Educational Rights and Right to Constitutional Remedies.

3 See Ashutosh Varshney’s article, Ethnic Conflict and Civil Society: India and Beyond https://www.jstor.org/stable/25054154 ; see also Soham Das, Ethnic conflict in the Indian Subcontinent: assessing the impact of multiple cleavages. DOI: 10.1177/2347797019886689

4 See https://indiancitizenshiponline.nic.in/UserGuide/E-gazette_2019_20122019.pdf

5 See https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1522/1/a1955-57.pdf

6 The term ‘illegal’ is used in the Citizenship Amendment Act to refer to the undocumented immigrants. The researcher therefore uses ‘illegal’ when explaining the content of the Act.

7 The Citizenship Amendment Act 2019, Government of India, Ministry of Law and Justice.

8 CAB-The Citizenship Amendment Bill for the Citizenship Amendment Act. See https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-how-to-be-a-citizen-of-india-earlier-now-6165960/

9 Bandh is a part of protest and social movement tactics, usually found in South Asian countries of India and Nepal where the activist calls for a mass protest- which results in closure of shops and offices.

10 https://www.outlookindia.com/national/shaheen-bagh-demolition-row-how-it-became-hub-of-anti-caa-protests-in-2019-news-195713

11 Affidavit of Delhi Police in Ajay Gautam, July 2020, Annexure-D, Note 1

12 https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/two-years-after-caa-was-passed-rules-governing-it-yet-to-be-notified/article37916342.ece

13 The Indian Census is the largest single source of various statistical information on various characteristics of the people of India. see https://censusindia.gov.in/census.website/node/325

14 https://www.indiacode.nic.in/repealed-act/repealed_act_documents/A2004-6.pdf

15 https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=186562

16 https://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/states/assam/documents/papers/illegal_migration_in_assam.htm

17 https://thewire.in/government/complaint-filed-against-assam-ex-nrc-chief-prateek-hajela-for-manipulating-

process.

18 Writ Petition (Civil) No 562 Of 2012 in the Supreme Court of India, Civil Original Writ Jurisdiction. Access through: https://main.sci.gov.in/case-status

19 https://www.scobserver.in/reports/indian-union-muslim-league-citizenship-amendment-act-caa-writ-petition-summary-all-assam-students-union/

https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/4210/1/Citizenship_Act_1955.pdf

20 https://graphsearch.epfl.ch/en/concept/1381513

21 https://www.scobserver.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Assam-Accord-Writ-Petition.pdf

22 https://www.aa.com.tr/en/analysis/-statelessness-in-assam-bangladesh-faces-heat-of-indias-politics/1572973

23 The Assam Accord 1985 has been named as Problems of Foreigners in Assam, Memorandum of Settlement

24 See https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/humanrights/2020/08/10/the-national-register-of-citizens-and-indias-commitment-deficit-to-international-law/

25 Inner Line Permit (ILP) is an official travel document issued to allow inward travel of an Indian Citizens by the Government of India into a protected area for a limited period. It is obligatory for Indian citizens from outside those states to obtain a permit for entering into the protected state. The Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Manipur, and Nagaland requires ILP from their tourists to enter into the state.

26 Enacted in the 1949 as per article 244 of the Indian constitution, the sixth schedule of Indian Constitution safeguards the tribal areas in the four North-eastern Indian states namely: Assam, Mizoram, Meghalaya and Tripura. The Tribal areas under the sixth schedule are granted autonomy to establish autonomous district councils or ADCs to foster tribal area development and protect their area from exploitation by others.