Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 15, No. 2

2023

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

Women Leaders and ESG Performance: Exploring Gender Equality in Global South Companies

Monique de Oliveira Cardoso*, Gustavo Andrey de Almeida Lopes Fernandes, Marco Antonio Carvalho Teixeira

Fundação Getulio Vargas, São Paulo, Brazil

Corresponding author: Monique de Oliveira Cardoso, Fundação Getulio Vargas, Av 9 de Julho, 2029 – São Paulo SP 01313902, Brazil, monique.cardoso@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v15.i2.8615

Article History: Received 13/04/2023; Revised 19/05/2023; Accepted 29/06/2023; Published 30/07/2023

Citation: Cardoso, M. O., Fernandes, G. A. A. L., Teixeira, M. A. C. 2023. Women Leaders and ESG Performance: Exploring Gender Equality in Global South Companies. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 15:2, 64–83. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v15.i2.8615

Abstract

This paper investigates the relationship between environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and gender equity in companies operating in the Global South. Using data from an ESG rating encompassing approximately 100 companies in one of the largest economies in the Global South, we explore whether higher ESG scores are associated with greater gender equity. The findings reveal that organizations with higher ESG scores demonstrate more robust performance in gender indicators and exhibit greater transparency. This relationship is particularly pronounced for companies excelling in the social aspects of ESG evaluation. However, despite their reputation for sustainability, women still face challenges related to low representation and lower salaries within these companies.

Keywords

Environmental, Social and Governance Performance; Women in Leadership; Gender Equality

Introduction

This research explores potential correlations between the environmental, social and governance (ESG) evaluation of companies in terms of their sustainability practices and management and the level of gender equity observed within organizations operating in the Global South. In these regions, companies face unique challenges and pressures related to the environment, society, and gender, operating within diverse socio-cultural contexts. These countries often grapple with issues such as compromised human rights and increased environmental degradation, particularly within the supply chains of large companies.

To achieve this objective, we employ a two-step approach. In the quantitative stage, we analyze the ESG performance data from the Bloomberg rating agency and examine six gender markers. In the qualitative stage, we interview senior executives from a subset of the analyzed companies to explore potential mechanisms underlying this relationship.

This paper consists of six sections. After this brief introduction, we discuss the existing literature on gender equity and ESG. Toward the end of this section, we present our central hypothesis. In the third section, we provide a detailed explanation of the data and methodology employed. Subsequently, we present our findings. In the fifth section, we discuss the main results and their implications. Finally, in the sixth section, we offer our concluding remarks.

Literature Review

Several authors highlighted the beneficial impact of corporate commitment to social and environmental issues (Eccles, Ioannou, & Serafeim 2014; Jha & Rangarajan 2020; Manrique & Martí-Ballester 2017; Tarmuji, Maelah, & Tarmuji 2016; Trumpp & Guenther 2017). Women in senior positions can also have a positive influence on sustainability performance (Chams & García-Blandón 2019; Qureshi et al. 2020; Post, Rahman, Mcquillen, 2015); Velte 2016; Graham 2019; Pinto, Bianquini, & Terreri 2019; Ginglinger & Raskopf 2019; del Carmen Valls Martínez, Martín Cervantes, & Cruz Rambaud 2020).

The recent emergence of ESG factors in investment decisions has given new impetus to the corporate sustainability agenda, with increasing consideration of the socio-environmental performance of companies in risk-return analyses for investment decision-making. While there is no single understanding of what one should prioritize when analyzing risk and performance using ESG factors or ratings (Porter, Kramer, & Serafeim 2019; Tucker & Jones 2020), significant progress has been made by reporting organizations, financial institutions, and data providers such as GRI, CDP, SASB, Sustainalytics, MSCI, and others, offering information at different levels and for different purposes (Kotsantonis, Pinney, & Serafeim 2016).

American and European banking institutions have predominantly embraced Responsible Investments (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim 2018), while the adoption of ESG factors has been slower in Global South countries, where it is still considered a financial sector innovation (Mendez, Forcadell, & Ubeda 2021). In the context of this research, the Global South refers to countries with an average Human Development Index, significant social and economic inequalities, and notable vulnerability to climate change, including Brazil, China, Mexico, and India (Levander & Mignolo 2011).

In countries such as Brazil, which competes with India for the position of the largest economy in the Global South, gender inequalities are also significant, with women comprising approximately 11.5% of corporate boards (IBGC 2021). We found that a 1% increase in female representation at the top decision-making level leads to a 2.21% growth in a company’s value (Schmiliver et al. 2019; Silva Júnior & Martins 2017).

Combined, good ESG performance and the presence of women in high leadership positions within organizations present fewer risks and greater dividends for shareholders (Adams & Ferreira 2009; Dezso & Ross 2012; Van Staveren 2014; Eccles, Ioannou, & Serafeim 2014; Post et al. 2015; Velte 2016; Kotsantonis & Serafeim 2019; Rissman & Kearney 2019). Women holding executive positions contribute to higher corporate sustainability ratings (Bear, Rahman & Post 2010; Chams & García-Blandón 2019; Qureshi et al. 2020).

Gender diversity in leadership positions can position companies favorably regarding ESG (Boulouta 2013). Women tend to prioritize socio-environmental agendas and have a greater intention to promote sustainability within companies, leading to investments in sustainable strategies and practices (Boulouta 2013; Weinert 2018; Ginglinger & Raskopf 2021).

Large companies often omit social performance data in sustainability reports (Cubilla-Montilla et al. 2019). The S in ESG factors represents social performance, encompassing working conditions and human rights, safety and health, customer communication, community relationships, and gender equity (Oželienė 2018). Reasons for the low transparency regarding social information include cultural values within society (Adams, Gray, & Nowland 2010; Elomäki 2018; Cubilla-Montilla et al. 2019) and the regulatory pressure associated with data disclosure (Cubilla-Montilla et al. 2019).

Measuring social indicators is crucial for better understanding the advancements in this field (Hutchins et al. 2019). The lack of disclosure of gender information violates stakeholder rights and may perpetuate the violation of women’s rights, as equity issues remain unaddressed and undiscussed (Hossain, Nik Ahmad, & Siraj 2016).

Furthermore, a more gender-diverse executive body can inspire other women to pursue higher positions (Dezso & Ross 2012). They contribute to improved management information quality, reflecting the group’s performance. A higher number of female board members increases the likelihood of a woman chairing the group, reflecting factors such as age, qualifications, and autonomy gained by them. Consequently, directors may appoint more female CEOs, providing a real possibility for effective female leadership (Wang & Kelan, 2013) and implementing gender policies within companies (Furlotti et al. 2018).

***

All in all, the literature review has revealed a significant gap: Is there a stronger presence of gender equity in companies that demonstrate better performance in sustainability? Based on this, we formulate our research questions as follows:

H0: Do better ESG performance companies have more gender equity?

Alternatively, we also infer the impact of social performance, reformulating as follows:

H1: Do better social performance companies have more gender equity?

In addition to answering the questions, we explore which mechanisms can explain the result, thus seeking to understand how the presence of women in high leadership can influence the performance in ESG factors by organizations and the level of gender equity in the organizations themselves.

Research Design

Firm Selection

We selected a sample of 93 Brazilian companies from a pool of 450 organizations listed on the Brazilian stock exchange based on their evaluation of ESG criteria by the Arabesque S-Ray® rating agency. Brazil boasts the largest GDP in Latin America and the Caribbean and ranks as the 11th largest economy globally. The country is a focal point in global discussions on climate change due to the threat to its natural assets, its crucial role as a protector of the Amazon, and its significant food exports.

Despite the size of its economy, which brings it closer to the Global North, Brazil, in its social and economic aspects, fulfills all the characteristics that place it as a member of the Global South (Burges 2005; Pecequilo 2008). It is in the process of development and is still an emerging economy. Like all Latin American countries, it has its past as a colony, differing from the Americas for having been colonized by Portugal. Within its social and economic structure, it bears the marks of various inequalities: economic between its regions; of gender, class, and race in terms of income and exclusion from access to public policies and power resources, among many others (Fausto & Fausto 2014).

The ESG information about Brazilian companies was obtained in 2020, covering a 24-month dataset. The rating agency’s database leverages artificial intelligence and big data techniques. That approach allows for systematically integrating over 250 ESG metrics with news signals from various sources. It encompasses over 30,000 publications across 170 countries (Arabesque 2021). The selected companies represent diverse sectors of the economy, including energy, infrastructure, metallurgy and steel, construction, banking, food and beverage, healthcare, pharmaceuticals, and retail.

Of the 93 Brazilian firms analyzed, 58 provide data on the gender ratio within their workforce, while 35 do not disclose any demographic information. It is important to note that, except for the retail and healthcare sectors, which serve as outliers, the industries predominantly featured on the rating list are typically male dominated in countries like Brazil.

For our analysis, we utilized two available ESG Score lists: the overall score of companies within the reference country (the Country rank) and the Social Rank, which assesses gender-related subjects, diversity, employment quality, and human rights.

Quantitative Analysis

In the quantitative stage of our research, we examined the relationship between the scores of companies in both the ESG Score and the social score and six factors (see Table 1) that are considered indicators of gender equity. Our objective was to understand the impact of women occupying decision-making positions and the level of transparency regarding gender equity on the sustainability performance of the selected companies. We employed a simple correlation analysis for this purpose.

Factors 1 and 2 pertain to the presence or absence of women on the executive board and the board of directors, respectively. We obtained the data for these factors by consulting the annual reports submitted to the Brazilian Securities and Exchange Commission (CVM) yearly. These reports are required to adhere to the criteria set by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Factor 3 focuses on the representation of women in these high-level leadership positions within each company, categorized into four distinct percentage ranges.

We obtained Factors 4, 5, and 6 from the companies’ sustainability reports in our sample. These reports were published in 2020 and were based on the GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) protocol indicators, specifically in the section related to diversity and opportunities. The disclosure of these indicators or similar ones by companies serves as a means to assess their performance in terms of workplace diversity and equality (Cubilla-Montilla et al. 2019).

The inclusion of these data in the reporting practices, as indicated in Table 1, demonstrates a concern with transparency regarding the demographic composition of the workforce (factors 1, 2, and 3). It also signifies a dedication to ensuring the presence of women in all leadership positions (factors 4 and 5), as well as a primary focus on equity by disclosing the gender pay ratio (factor 6). We will consider whether the indicators are reported for analyzing factors 4, 5, and 6. Specifically, we will classify companies as Does Not Report (NR), Reports (R), or Reports zero (R/0), which indicates the absence of women. The study will not consider the specific information disclosed by each company.

It is important to note that our level of analysis does not allow for causal inferences. However, we expect that gender equality will increase with the implementation of ESG policies, and the opposite should also be true. ESG is a more comprehensive concept, making it potentially more influential in promoting gender equality than the other way around (and vice versa). Therefore, our primary interest is in examining whether this expected two-sided relationship exists. Correlation analysis serves as a valuable tool in this regard. Additionally, we use qualitative analysis to uncover mechanisms and infer how this relationship operates.

Qualitative Analysis

During the second data collection stage, we conducted in-depth interviews with 14 women executives representing some of the 93 companies in the Arabesque S-Ray® list. It is important to note that accessing women in high leadership positions for interviews proved challenging due to their responsibilities. However, despite the difficulty, we were able to interview women from 15% of the companies in the quantitative sample.

These in-depth interviews aimed to gain a deeper understanding of socio-environmental performance and equity from the perspectives of women who are witnesses or agents of these realities (Creswell & Creswell 2017; Leavy 2014). The aim was to enrich the findings of the quantitative stage by revealing the mechanisms that explain the results.

During the interviews, we asked the participants about their perceptions of gender equity within organizations after reaching the top of the corporate hierarchy. We also sought to identify their reflections on how women in high leadership positions can influence business performance in ESG, considering various perspectives and personal capabilities.

The interviewees comprised ten directors and four board members, all occupying statutory, executive, or higher management positions. We identified 104 potential candidates, and from this group, we obtained direct contact information for 30 individuals, including their corporate and personal email addresses and mobile phone numbers. These contacts represented executives and board members from 19 companies. Fourteen positively responded to the invitation to participate in the study during the data collection period, which took place between September 2020 and January 2021. These participants represented 12 different organizations, accounting for 13% of the sample of companies. The interviewees were not informed about their respective companies’ ESG classification (high or low) to avoid response bias.

The participants in the study ranged in age from 33 to 64, with nine of them in their 50s. All participants were Brazilian, with 13 being married or previously married and one being single. Among those who were mothers, three had small children. All participants held at least one graduate degree, with nine holding two or more degrees. Among the group, 10 were directors, superintendents, vice presidents, and/or presidents, two were female board members serving as internal advisors, and two were independent advisors. Except for two independent advisors, all interviewees had built their careers within their respective companies, with at least ten years of service.

We used a semi-structured interview script with 13 open-ended questions for data collection. The research approach adopted a non-positivist perspective to understand the ‘reality experienced by social actors’ (Gil 2008, p. 37) and to capture opinions, worldviews, and the ‘meanings attributed by the subjects to the object being studied’ (Gil 2008, p. 15).

We recorded all 14 interviews with the participants’ authorization. Subsequently, we transcribed the content and selected relevant excerpts and categories we identified. The most frequently mentioned codes were determined from these categories, resulting in a total of 137 codes. The ten most frequently mentioned codes were utilized for analysis purposes, aided by the MAXQDA software.

Results

Descriptive correlation analysis

To address the research question, the companies in the sample were divided and classified into different groups based on the presence or absence of women in leadership positions and their ESG and social scores. The evaluation conducted by Arabesque S-Ray® assigned a maximum score of 100 points, with the highest score among the 93 Brazilian companies being 97.93 and the lowest score being 2.24 points. To categorize the companies based on performance, we calculated the average score of 47.88 between the highest and lowest scores.

For the ESG scores, we divided the companies into two groups: High ESG (46%) and Low ESG (54%), based on their performance relative to the average score. The same procedure was repeated for the Social Rank scores, resulting in the classification of companies into High Social (54%) and Low Social (46%) groups, using the average score of 54.24.

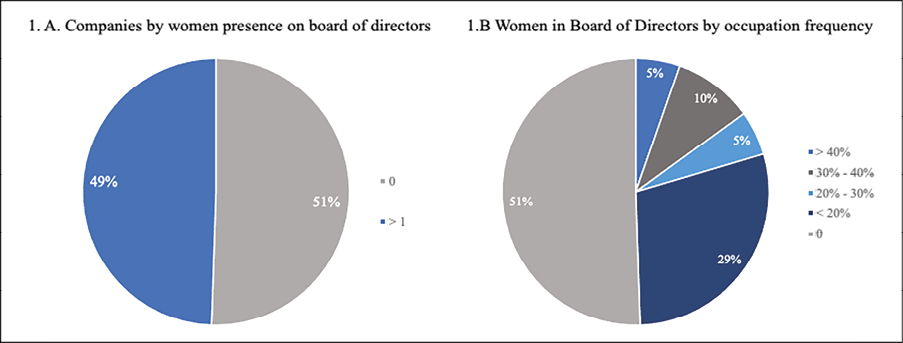

Regarding the presence or absence of female members on the board of directors, we found that 49% of companies had at least one female director (presence), while 51% had none (absence). In the highest corporate governance structure, the board, at least one female board member was present in 73% of the companies.

Among the companies with women occupying high leadership positions, only 15% had a proportion equal to or greater than 30% of female members. In 34% of companies, the number of female executives was lower than this threshold, and in 29% of companies, women occupied 20% of the board seats or less.

Graph 1. Occupation of leadership positions by women frequency

Source: The Authors

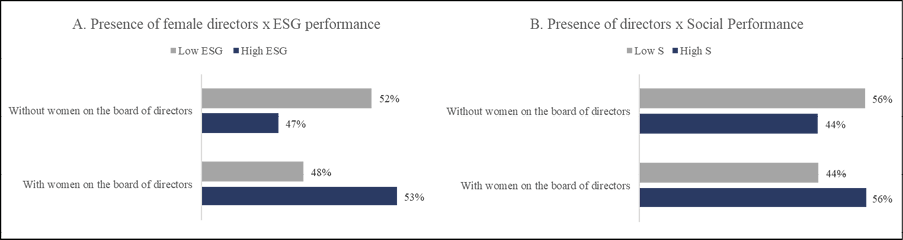

Response to H0

In H0, our objective was to examine whether organizations with stronger ESG performance exhibit greater gender equity. To address this inquiry, we analysed factors 1, 2, and 3. We correlated them with the ESG scores obtained by companies, focusing on the presence of women on the board of directors and examining the level of gender representation in companies with high and low sustainability ratings. Our findings indicate that companies with higher ESG scores have a higher proportion of women on the board of directors (53%) and in senior leadership positions (80%) compared to companies with lower ESG scores (48% and 56%, respectively). We present these results in Graph 2.

Graph 2. Presence of women in high-performance leadership

Source: The Authors

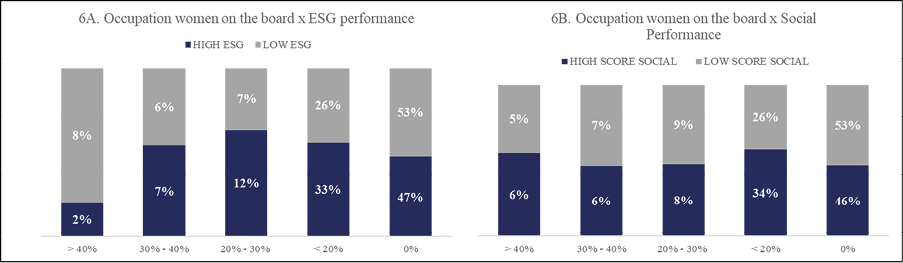

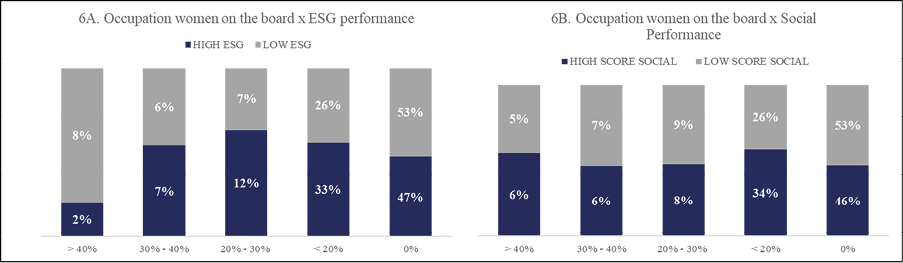

Upon analyzing the correlations, we discovered that although good performance in ESG scores is associated with a higher frequency of women in senior leadership roles, it does not automatically translate into a balanced gender representation in these positions, as depicted in Graph 3. Notably, companies with low ESG scores (14%) exhibit a higher presence (30% or more) of women directors compared to high ESG organizations (9%).

Sustainable companies demonstrate better performance in the following category, which encompasses companies with an average representation of 20% to 30% of women in senior leadership positions. However, in both high and low-ESG groups, the representation of women on the board remains limited to 20% or less, occurring in 33% of companies in the high-ESG group and 26% of companies in the low-scoring group.

Graph 3. Representation rate of women in high leadership positions versus ESG performance

Source: The Authors

Regarding the criterion of presence of women on boards, 80% of high ESG companies have female advisors, compared to 56% in the low ESG group. However, the representation of women on boards remains limited, with most companies having women occupying 20% or fewer seats. That is the case for 58% of companies with high ESG scores and 48% with low ESG scores.

It is essential to recognize that a limited representation of women can lead to tokenism and restrict their power to contribute and influence decision-making processes (Silva Júnior & Martins, 2017). The theory of critical mass suggests that to make a significant impact, women should occupy at least 30% of decision-making positions (Joecks, Pull, & Vetter 2013).

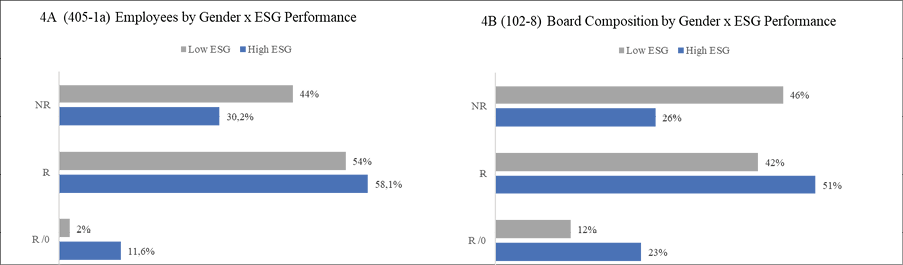

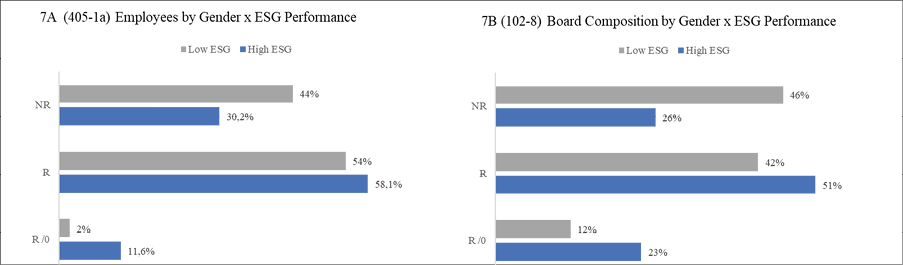

Addressing H0 also involved comparing the extent and nature of disclosure of crucial gender indicators, per the GRI guidelines, among organizations in each group (factors 4, 5, and 6). According to our survey, 62% of companies surveyed and published the GRI 405-1a indicator, which provides demographic data on employees by gender and position. However, 38% of companies did not disclose any such information. When considering the publication rate of this indicator based on ESG scores, a higher proportion of companies with high scores (72%) reported the data compared to low ESG companies (54%).

In a stratified analysis, as depicted in Graph 4, a more significant percentage of high ESG companies (70%) reported this data compared to low ESG companies (56%). Among the companies that measured and disclosed the GRI 405-1a indicator, which captures the composition of functional categories by gender (58 out of 93 companies), 22% of companies with low ESG scores reported the absence of women (0) in positions above the coordinator level. This proportion was lower (16%) among high ESG companies that published the data.

Graph 4. Presence of women disclosure rate x ESG performance

Source: The Authors

The disclosure of the composition of the board of directors by gender (GRI 102-18) is mandatory for publicly traded companies in Brazil. However, among the 93 companies evaluated, 37% of organizations either do not report this information or do not commit to annually publishing their sustainability report.

Graph 4 shows that companies with high ESG scores (74%) have a higher reporting rate of the board of directors’ composition by gender compared to the low ESG group (54%). We attributed this disparity to companies’ commitment to publish a sustainability report. A greater proportion of low ESG companies (46%) do not publish annual reports compared to the well-rated sustainability group (26%). This 20-point difference may explain the discrepancy in reporting practices concerning organizational gender performance.

Among the companies that disclose the distribution of employees by position and gender (GRI 405-1a), those with high ESG performance (17%) are more transparent about the absence (R/0) of women in leadership positions compared to the low ESG group (4%). Similarly, the disclosure of the absence of female board members is more prevalent in the high ESG group (31%) than in the low ESG group (22%).

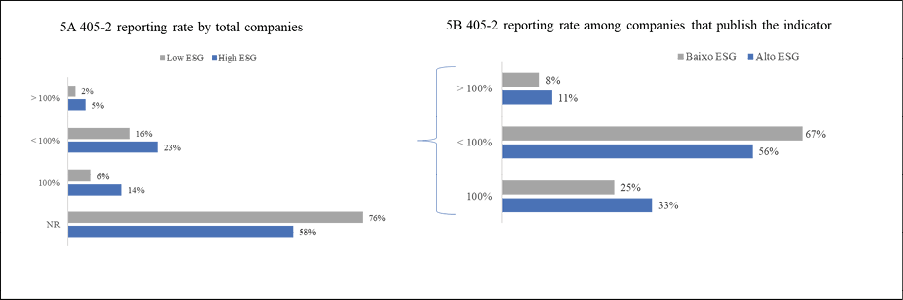

Factor 6, which pertains to GRI 405-2, is considered an essential key performance indicator (KPI) for gender equity in the workplace, as it evaluates the wage gap between men and women. According to Graph 5, companies with high ESG scores report a significantly higher proportion (42%) of the M/F salary ratio than low ESG companies (24%), even if the data is not always favorable. Among high ESG companies that disclose the pay ratio, 44% of women earn equal salaries (33%) or more than men (11%), while 56% earn less. In low ESG companies that disclose this information, 33% of women executives receive equal salaries (25%) or more than men (8%). In contrast, the majority, 67%, receive lower salaries than male executives in the same position.

Graph 5. (405-2) Pay ratio M/F x ESG Performance

Source: The Authors

Overall, the findings indicate that companies with better overall ESG performance rely on women in high leadership more often, show greater transparency in reporting gender performance data, and better performance in gender equity key performance indicators (KPIs) compared to companies with lower sustainability performance rates.

However, it is essential to note that while there is a higher reporting rate and relatively better performance on the analyzed KPIs, the study highlights that a reasonable performance on gender markers does not necessarily guarantee satisfactory gender equity outcomes. Nonetheless, the study suggests that women employees and leaders in companies that receive poor evaluations from Arabesque S-Ray® (Low ESG) are worse than in organizations that receive high evaluations (High ESG) in terms of representation and equal pay.

Response to H1

To answer H1, it was also necessary to evaluate all six factors described above, such as the distribution of female representation in the board of directors and advisory board positions and transparency of companies regarding GRI equity KPIs compared to their score received in the Social Rank.

Graph 6. Presence of women disclosure rate x social performance

Source: The Authors

Graph 6 illustrates that the representation of women on boards of directors is limited to 20% or fewer positions, with 34% of well-evaluated social companies and 26% of companies with low social scores having women in these positions. Companies with a female representation between 20% and 30% on their boards account for 8% of high-score companies and 9% of low-score companies. Only 12% of organizations in each group, whether high or low social scores have a female representation exceeding 30% on their boards. On the advisory boards, there is a more significant presence of women in well-evaluated social companies, with 78% having at least one female advisor, compared to 67% in poorly evaluated companies.

Examining the number of female board members, a higher percentage of companies with low social scores (7%) represent 30% or more women on their boards compared to companies with high scores (4%). In the range of 20% to 30% representation of women on boards, companies with above-average social scores show a slightly higher frequency of women (22%) compared to the other group (19%).

Similar to the representation on the board of directors, most companies have minimal female representation at the advisory board level, with less than 20% of available positions filled by women. That occurs in 33% of companies with low social scores and 22% of companies with high performance in the social aspect.

Transparency in disclosing gender performance information was also evaluated based on the Social Score. In terms of disclosing the composition of the functional staff by gender, explicitly identifying the presence of women in positions of coordinator or higher (GRI 405-1a), 78% of companies with good social performance report this information, compared to 44% among companies with low scores in the aspect, as shown in Graph 7. This indicator’s disclosure percentage is higher among well-evaluated social companies compared to high ESG companies, as the social score explicitly considers gender issues.

Graph 7. Presence of women disclosure rate x social performance

Source: The Authors

Among companies with a high Social Score that publish official sustainability information, 80% of them disclose the composition of the board by gender (GRI 102-8), compared to 45% in the group with the lowest evaluation. This significant difference reinforces the importance of disclosure among companies that demonstrate greater maturity in social practices.

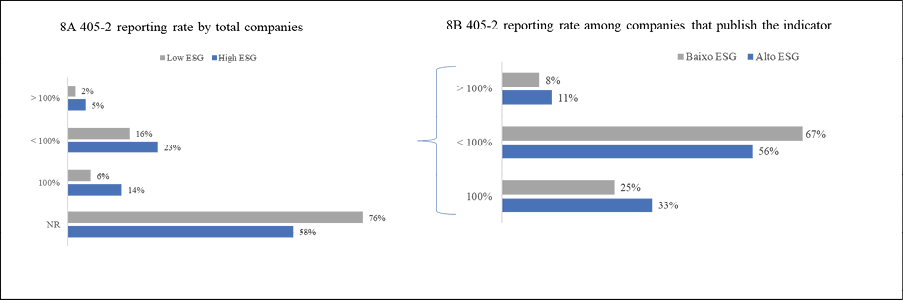

Lastly, as shown in Graph 8, more than twice as many companies with a better social evaluation (42%) report the wage ratio between men and women compared to the worst-performing organizations (18%). That indicates a higher level of transparency and commitment to addressing gender pay disparities among companies with better social performance.

Graph 8. (405-2) Pay ratio M/F x Social Performance

Source: The Authors

In the group of companies with high social performance that report the GRI 405-2 indicator, 24% of women receive the same salary as men, 62% earn more (or 26% of the well-evaluated list), and 14% receive lower remuneration (or 6% of the total). On the other hand, among the lower-performing social companies that report wage equivalence information, half have women receiving the same salary as men, while the other half have women receiving lower salaries than men. We did not find companies with low social performance where women earn more than men.

The findings do not reject the hypothesis (H0) based on the analyzed data. Companies with high social scores demonstrate more gender equity factors than the other group. These companies have a higher presence of women on boards of directors and advisory boards, report more frequently on female representation in leadership positions, show more transparency regarding the absence of women, and disclose information on pay equity more often. Among those reporting this specific data, there are more companies with high social performance where women earn equal or higher salaries than men.

These results justify the high position of companies with high social scores on the Arabesque S-Ray® list, as factors such as diversity and equal opportunities contribute to social performance in the ESG evaluation, even though they are two factors in a universe of several others, as in the agency analysis filter. It is also worth noting that the group classified as having high social performance, in isolation, performs better in gender equity indicators than the group classified as having high overall ESG performance, confirming that social evaluation is a more influential aspect of equity performance.

Source: The Authors

Discussion

Possible Mechanisms to Explain the Results

In order to further understand and explain the results obtained in H0 and H1, several mechanisms were explored. Firstly, we found companies with better ESG scores and social performance to have more female board members and executives in leadership positions. These companies also demonstrated a stronger commitment to gender performance by disclosing relevant equity markers through the GRI protocol, a widely used framework for reporting ESG performance.

To delve deeper into these findings, we interviewed 14 senior executives from the Brazilian companies evaluated by Arabesque S-Ray®. These interviews aimed to gain insights into women leaders’ personal and leadership characteristics, as their Presence on boards was positively associated with good ESG performance. Additionally, we asked the executives about the barriers they face in their leadership roles to determine if sustainability maturity alone is sufficient to foster a more egalitarian environment.

We conducted the interviews and analyzed them using software identifying the frequency of relevant codes. We identified 137 codes and the ten most prevalent codes, which we presented in Chart 2. These codes were grouped based on their affinity rather than presented in a specific order. By interpreting these prevalent codes considering the results obtained in the previous section, which focused on analyzing the six observed factors, we aim to provide further insights and understanding into the mechanisms underlying the findings.

Mechanisms Associated with Gender Relationship of Leadership and ESG Performance

First, let us examine five codes from the list together: the first, fourth, and seventh, followed by the second and third due to their similar meanings. The most frequently mentioned code, Adequate ESG Disclosure and Transparency, highlights how female executives engage in effective environmental, social, and governance management practices prioritizing ESG performance concerns. This mechanism helps explain the positive results identified in the quantitative research stage. Companies with high ESG scores exhibit a higher reporting rate across all six gender markers we considered. These companies demonstrate a commitment to transparency by disclosing more non-financial information to their stakeholders.

Moreover, the association between the degree of information disclosure and the code Investor and Market Pressure (fourth) suggests that our interviewees emphasize another mechanism reinforcing their companies’ responsiveness to the financial market’s expectations. They are attuned to the increasing significance of ESG performance in investment decision-making (Van Duuren, Plantinga, & Scholtens 2016).

ESG is not a novelty, but it has become the hot topic of the moment. It’s funny, all these ratings, which depend on some people to fill out a long and complex questionnaire, if you don’t engage teams and can’t make people understand why it’s important, they’ll deal with it as any other form, let me finish soon. Now I’m not just me talking anymore. We could be better from a rating point of view, so we›re doing the best of the evaluation agencies. (Participant 10, director)

The seventh code on the list, Track indicators, respond ratings, also denotes a view that frames sustainability performance with a management class guided by verifiable results.

Due to the particularities of our industry, we look a lot at ESG metrics. We need to show results to our shareholders and be good for society. That’s where we see that company strategy is aligned to sustainability. ESG updates this strategy by giving shareholder value. We also look at independence, the number of women on the board. We’ve got a woman advisor there again, thank God. They look more at the company’s policies than men. (Participant 5, director)

Women directors of big companies, however, make the common criticism of greenwashing risk; according to them, many organizations still speak more than they do regarding sustainability, from which we conclude that consistency is a value.

We [the company] are very targeted; we can’t say something about the company without doing it. Everything we’re doing in the Sustainability field, and winning awards for it, is a fact. Still, I think we talk more than we do. The practice always must follow the discourse. (Participant 2, director)

We can also combine the interpretation of the prevalent codes that rank second and third on the chart, as they contribute to further understanding the positive association between the increased Presence of women and higher gender representation with good ESG performance. Esteemed authors such as Porter, Serafeim, and Kramer (2019), who are pioneers in the discussion of sustainability in business strategy, argue that superior performance in material environmental and social issues, which are integrated into the core of business operations, can have a significant financial impact. However, they caution that only a few corporate leaders and investors truly recognize ESG as valuable. The presence of women, as observed in our quantitative analysis, may promote this perspective:

It annoys me a lot, and I ‘ve been asked all the time, what sustainability strategy of the people [bank]. It’s not a sustainability strategy. It’s sustainability guiding the business strategy. (Participant 8, superintendent)

The third most frequently mentioned code on the top ten list is Care and sensitivity, which are typically associated with femininity and often considered negative traits for executive positions (Lima et al. 2014). However, the interviewed executives emphasize these qualities as female attributes that can contribute to advancing the ESG agenda, challenging and valuing such stereotypes.

Having children or not, women bring a motherhood’s eye, and this is interesting regard at the bank’s executive leadership team. Raising children is something that updates you constantly, brings you daily challenges. It all makes you a complete person. (Participant 4, Superintendent)

This aspect can lead to positive reputational outcomes for companies regarding ESG and financial performance. Lower exposure to risks arising from inadequate management or disregard for socio-environmental issues makes organizations more appealing to investors. By embracing care and sensitivity, companies can enhance their overall sustainability and attractiveness in the market.

I needed to be involved in something that had a positive impact, to leave a mark, that millennial thing. And you have the concern about how to make the world better, the question of a lot of consumption, of a lot of plastic, even indoors; I began to wonder: is this the world my children are going to live in? And then I went after working with it. (Participant 10, director)

Mechanisms Associated with Equity

In this second part, we have identified that the remaining five codes (5, 6, 8, 9, and 10) in the list we can interpret as a set of mechanisms that further elucidate the results obtained in the initial stage of the research. As previously discussed, the GRI indicators monitored and reported by companies address aspects such as the representation of women in different positions, disclosure of women’s presence or absence on boards, and gender pay ratio.

These five codes specifically encompass the experiences of women in the corporate environment. Therefore, we posit that they can help explain the link between ESG and social performance and the positive results observed regarding the level of disclosure and performance of GRI indicators related to gender equity.

For the female executives who participated in the study, attaining high leadership positions results from their effort (code 5). Participant 2, a statutory director in the country’s largest online retail group, affirms: ‘Everyone respects me, whether it’s for my work, what I do, the large team I manage, or my responsibilities’. Female executives often need to assert their power and competence, as they are familiar with the need to consistently prove themselves capable (Lima et al. 2014; Mota, Tanure & Carvalho Neto 2015).

We always see men coming up, even when there were women in the same team who were better options. As women, we wanna try to make it better. Men have never been through this situation. They’ve always been kings with their established place. Women are still establishing their spots. (...) And they will stand for an agenda men will not handle. (Participant 5, director)

Women leaders perceive it as their responsibility to prioritize diversity and actively address the issue of equity (codes 8 and 9), consistent with previous studies’ findings (Larrieta-Rubín de Celis et al., 2015; Wang & Kelan, 2013).

We have to practice more the sorority, one pulling the other. But women also need to speak up about what they want. It’s behavior change going on. I’m watching [in the company] women getting promotions more often, not because the company needs to improve its numbers in equity, but because there are very capable professionals that just took more time to reach higher positions. (Participant 10, director)

The weight of being the sole woman in a leadership position within the company (code 10) concerns our interviewees regarding being misunderstood in their proposals, moreover, being the only woman on a board of directors’ risks being seen as a token. Tokens are individuals who symbolically hold positions of power without significantly influencing the group dynamics or being able to garner majority support for the proposals they wish to advocate or promote.

Newly hired, the new CFO noticed my work and decided to promote me. I replied that I was flattered, but I doubted that it was going to happen. I worked at the company for ten years at the time and was a relatively young financial planning analyst. So, I was not supposed to reach that post because only men and engineers had occupied the position the CFO was offering to me. Some people tried to stop it, but at the end of the day, I got promoted to Financial Superintendent. And I had to face all the consequences it brought to me from then. (Participant 13, board member)

Participant 13 shared her experience as a lone dissenting voice, often finding herself as the only woman in a room of 42 men. That highlights the issue of representation, which we identified as a mechanism explaining the non-positive data found in factor 3 during the quantitative analysis. The data shows that women’s occupancy of top leadership positions in most companies is limited to only 20% of the seats. Female executives are aware that being the sole woman in a leadership role can bring about risks and challenges and can be instilling and unfair. Despite breaking the glass ceiling, they may face what is known as the glass cliff phenomenon, where women are more likely than men to be exposed to adverse management conditions, precariousness, or high-risk situations, increasing the chances of failure and reinforcing negative stereotypes about female leaders (Ryan et al. 2016).

First, I was afraid because I would be the only woman on the board, imagining that big room full of gentlemen. And that’s the way it was. There are eight board members, including the chairman of the bank, all white men over 50. During the board meetings, it is difficult not to have a consensus. Usually, I am the one who votes differently. There is a synergy between them, often combining the vote before. But I need to make a stand. (Participant 7, board member)

Gender discrimination is statistically the main obstacle to women’s career progression and their entire exercise of leadership (Adams & Kirchmaier 2013). The same happens with low representation (Wang & Kelan 2013).

I’ve been put against the wall many times. Throughout my career, in situations involving fellow men, I was always afraid they would stand out more than I do. I never wanted to indispose myself to anyone [at this moment, the interviewee is thrilled and cries]. It hurt me because I thought it was my role to please. After all, it could decide whether or not I would get promoted or recognized. (Participant 10, director)

Despite occupying strategic positions in large companies, female executives often report being silenced, not given opportunities to express their ideas, or dismissing their arguments. They describe instances where their contributions are undervalued or where they are constantly interrupted in meetings. Interview 6 shared this experience of being marginalized a director of an electricity supply company. She says: ‘I’ve lived this experience many times: I had something to say, many ideas to add, and I was constantly cut off. They wouldn’t let me talk; it was a struggle.’ Interviewee 9, the vice president of a top sustainability health group, also confirms that even with her C-level position, she often feels that her input is undervalued during meetings.

Considering this, we can conclude that although objective criteria such as the presence or absence of women and transparency in gender indicators positively correlate with ESG performance, high ESG scores and social scores do not guarantee a fairer or healthier environment for women. The executives explain the association between women’s presence in leadership and ESG performance. Women value sustainability practices, advocate for the appropriate disclosure of material key performance indicators (KPIs), prioritize transparency, and strive to meet the demands of stakeholders and investor pressures.

Based on the experiences shared by the study participants, we can better understand that the fundamental mechanisms at play are (low) representation and gender bias. These experiences shed light on the fact that although there is more emphasis on sharing gender data, these indicators reveal a poor representation and a significant gender pay gap within organizations. The leading gender indicators alone are not sufficient to address the underlying gender bias that women face as they climb the corporate ladder. Companies may achieve maturity and recognition in sustainability rankings before attaining satisfactory progress in gender equity or effectively addressing and combating discrimination within their environments.

Conclusion

This paper aims to investigate the relationship between gender equity and the performance of companies in ESG factors. We analysed ESG evaluation data from publicly traded Brazilian companies and examined the presence of women in board positions, disclosure levels, and gender performance based on GRI indicators.

The results indicate a positive correlation between a strong sustainability performance rate and gender equality across five of six gender features. Notably, we observed an even stronger relationship when focusing on the social aspect of ESG in isolation. However, it is essential to note that a sustainability-oriented management approach alone is insufficient to foster an egalitarian environment or address issues such as equal pay, which remains an ongoing struggle for women worldwide and continues to be violated by companies.

There are limitations to this study, including the low number of companies considered in the ESG score list and the limited number of national capital companies listed on the Brazilian stock exchange. Additionally, the small number of interviewees, particularly high-level executives, poses a limitation due to the difficulty of accessing this group. Therefore, we cannot generalize the positive results regarding the gender-performance relationship to all Brazilian companies in this study.

Furthermore, we acknowledge that the lack of reliability and standardization in impartial ESG assessments raises concerns about the ranking scores as a comprehensive measure of a company’s adoption of impactful practices compared to others.

The analysis in this study establishes an association rather than causality, which serves as an initial step in addressing the identified gap in the literature. It raises important questions and encourages further research with new data and methodologies. Given the increasing interest in women’s leadership and ESG topics, we anticipate that future researchers will delve deeper into these areas. This study also leaves open questions regarding the effects and benefits of gender equity on the performance of companies across different sectors and sizes. It calls for a necessary discussion on the possible underlying mechanisms or factors that may provide additional explanations for the positive correlation observed in our findings.

References

Adams, R. B. & Ferreira, D. 2009, ‘Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance’, Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 94, no. 2, pp. 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.10.007

Adams, R. B., Gray, S., & Nowland, J. 2010, ‘Is there a business case for female directors? Evidence from the market reaction to all new director appointments’, SSRN Electronic Journal, pp. 1–48. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1662179

Adams, R. B. & Kirchmaier, T. 2013, Barriers to Boardrooms. ECGI - Finance Working Paper No. 347/2013, Asian Finance Association (AsFA) 2013 Conference, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2192918

Amel-Zadeh, A. & Serafeim, G. 2018, ‘Why and how investors use ESG information: Evidence from a global survey’, Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 87-103. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v74.n3.2

Arabesque 2021, Arabesque S-Ray Methodology, v.2.6.

Bear, S., Rahman, N., & Post, C. 2010, ‘The impact of board diversity and gender composition on corporate social responsibility and firm reputation’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 97, no. 2, pp. 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0505-2

Boulouta, I. 2013, ‘Hidden Connections: The Link Between Board Gender Diversity and Corporate Social Performance’. Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 113, no. 2, p. 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1293-7

Burges, S. W. 2005, ‘Auto-estima in Brazil: The logic’of Lula’s south-south foreign policy’, International Journal, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 1133-1151. https://doi.org/10.2307/40204103

Chams, N. & García-Blandón, J. 2019, ‘Sustainable or not sustainable? The role of the board of directors’, Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 226, pp. 1067–1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.118

Creswell, J. W. & Creswell, J. D. 2017, Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 5th edn, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Cubilla-Montilla, M., Nieto-Librero, A. B., Galindo-Villardón, M. P., Vicente Galindo, M. P., & Garcia-Sanchez, I. M. 2019, ‘Are cultural values sufficient to improve stakeholder engagement human and labour rights issues?’, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 938-955. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1733

del Carmen Valls Martínez, M., Martín Cervantes, P. A., & Cruz Rambaud, S. 2020, ‘Women on corporate boards and sustainable development in the American and European markets: Is there a limit to gender policies?’, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 2642–2656. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1989

Dezso, C. &Ross, D G. 2012, ‘Does female representation in top management improve firm performance?’, Strategic Management Journal, v.33, no.9, pp.1072-1089. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1955

Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. 2014, ‘The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance’, Management Science, vol. 60, no 11, pp. 2835–2857. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1984

Elomäki, A. 2018, ‘Gender quotas for corporate boards: Depoliticizing gender and the economy’– NORA - Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740.2017.1388282

Fausto, B. & Fausto, S. 2014, A concise history of Brazil, 2nd edn, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139567060

Furlotti, K., Mazza, T., Tibiletti, V., & Triani, S. 2018, ‘Women in top positions on boards of directors: Gender policies disclosed in Italian sustainability reporting’, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 57–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1657

Gil, A. 2008, Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social. 6th edn, Editora Atlas, São Paulo, SP.

Ginglinger, E. & Gentet-Raskopf, C. 2021, ‘Women directors and E&S performance: evidence from board gender quotas’, European Corporate Governance Institute – Finance, Working Paper nº 760/2021. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3832100

Graham, J. R. 2019, ‘Corporate Sustainability: The Impact of Corporate Leadership Gender on Year Over Year Performance’, In: Proceedings of the 2019 InSITE Conference, The Informing Science Institute, Santa Rosa, CA, 2019 InSITE Conference, Jerusalem, June 30 – July 4. pp. 149–183. https://doi.org/10.28945/4213

Hossain, D., Ahmad, N., & Siraj, S. 2016, ‘Marxist feminist perspective of corporate gender disclosures’, Asian Journal of Accounting and Governance, vol 7. pp. 11-24. https://doi.org/10.17576/AJAG-2016-07-02

Hutchins, M. J., Richter, J. S., Henry, M. L., & Sutherland, J. W. 2019, ‘Development of indicators for the social dimension of sustainability in a U.S. business context’, Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 212, pp. 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.199

Jha, M. K. & Rangarajan, K. 2020, ‘Analysis of corporate sustainability performance and corporate financial performance causal linkage in the Indian context’, Asian Journal of Sustainability and Social Responsibility, vol. 5, article 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41180-020-00038-z

Joecks, J., Pull, K., & Vetter, K. 2013, ‘Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm performance: What exactly constitutes a “critical mass?”’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 118, pp. 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1553-6

Kotsantonis, S., Pinney, C., & Serafeim, G. 2016, ‘ESG integration in investment management: Myths and realities’, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 10-16. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=51511

Kotsantonis, S. & Serafeim, G. 2019, ‘Four things no one will tell you about ESG data’, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, vol. 31, no. 2: pp. 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jacf.12346

Larrieta-Rubín de Celis, I., Velasco-Balmaseda, E., Fernández de Bobadilla, S., del Mar Alonso-Almeida, M., & Intxaurburu-Clemente, G. 2015, ‘Does having women managers lead to increased gender equality practices in corporate social responsibility?’ Business Ethics: A European Review, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12081

Leavy, P. 2014, The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199811755.001.0001

Levander, C., & Mignolo, W. 2011, ‘Introduction: the global south and world dis/order’, The Global South, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1-11. https://doi.org/10.2979/globalsouth.5.1.1

Lima, G. S., Neto, A. C., Lima, M. S., Tanure, B., & Versiani, F. 2014, ‘O Teto de Vidro das Executivas Brasileiras’, Revista PRETEXTO, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 65–80. http://revista.fumec.br/index.php/pretexto/article/view/1922

Manrique, S. & Martí-Ballester, C. P. 2017, ‘Analyzing the effect of corporate environmental performance on corporate financial performance in developed and developing countries’, Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 9, no. 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9111957

Mendez, A., Forcadell, F. J., & Ubeda, F. 2021, ‘Sustainable banking in the global south: ESG innovations in China’, ESIC: Digital Economy & Innovation Journal, vol. 1 no. 1, pp. 120-136. https://doi.org/10.55234/edeij-1-1-006

Mota, C., Tanure, B., & Carvalho Neto, A. 2015, ‘Mulheres executivas brasileiras: o teto de vidro em questão’, Revista Administração Em Diálogo - RAD, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 56-75. https://doi.org/10.20946/rad.v16i3.13791

Oželienė, D. 2018, ‘Model of company’s social sustainability’, Socialiniai Tyrimai, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 89-100. https://doi.org/10.21277/st.v41i2.255

Pecequilo, C. S. 2008, ‘A política externa do Brasil no século XXI: os eixos combinados de cooperação horizontal e vertical’, Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 136-156. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-73292008000200009

Pinto, L., Bianquini, H., & Terreri, A. 2019, As companhias brasileiras são socialmente sustentáveis? Uma análise das iniciativas de sustentabilidade social das companhias, Grupo de Pesquisas em Direito, Gênero e Identidade (FGV-GPDG), Sao Paolo. https://hdl.handle.net/10438/29384

Porter, M. E., Serafeim, G., & Kramer, M. 2019, ‘Where ESG Fails’, Institutional Investor, October 16. https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/2bswdin8nvg922puxdzwg/opinion/where-esg-fails>

Post, C., Rahman, N., & Mcquillen, C. 2015, ‘From board composition to corporate environmental performance through sustainability-themed alliances’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 130, no. 2, p. 423–435, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2231-7

Qureshi, M. A., Kirkerud, S., Theresa, K., & Ahsan, T. 2020, ‘The impact of sustainability (environmental, social, and governance) disclosure and board diversity on firm value: The moderating role of industry sensitivity’, Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 1199–1214. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2427

Rissman, P.; Kearney, D. 2019, ‘Rise of the shadow ESG regulators: Responsibility’, Environmental Law Reporter, vol. 49, no. 2, p. 10155–10187.

Ryan, M. K., Haslam, S. A., Morgenroth, T., Rink, F., Stoker, J., & Peters, K. 2016, ‘Getting on top of the glass cliff: Reviewing a decade of evidence, explanations, and impact’, Leadership Quarterly, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 446–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.10.008

Schmiliver, A. L., Teixeira, M. S., Brandão, M. D., Andrade, V. D., & Jucá, M. N. 2019, ‘A presença de mulheres cria valor às empresas?’, Revista Pretexto, vol. 20, no. 3, pp 83-97. https://doi.org/10.21714/pretexto.v20i3.6700

Silva Júnior, D., & Martins, S. 2017, ‘Mulheres no conselho afetam o desempenho financeiro? Uma análise da representação feminina nas empresas listadas na BM&FBOVESPA’, Sociedade, Contabilidade e Gestão, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 62-76. https://doi.org/10.21446/scg_ufrj.v12i1.13398

Tarmuji, I., Maelah, R., & Tarmuji, N. H. 2016, ‘The impact of environmental, social and governance practices (ESG) on economic performance: Evidence from ESG score’, International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 67–74. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijtef.2016.7.3.501

Trumpp, C. & Guenther, T. 2017, ‘Too little or too much? Exploring U-shaped relationships between corporate environmental performance and corporate financial performance’, Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1900

Tucker, J. J. & Jones, S. 2020, ‘Environmental, social, and governance investing: Investor demand, the great wealth transfer, and strategies for ESG investing’, Journal of Financial Service Professionals, vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 56–75. https://digitaleditions.sheridan.com/publication/?i=657585&article_id=3654132&view=articleBrowser

van Duuren, E.; Plantinga, A.; Scholtens, B. 2016, ‘ESG integration and the investment management process: Fundamental investing reinvented’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 138, no. 3, p. 525–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2610-8

van Staveren, I. 2014, ‘The Lehman Sisters hypothesis’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 38, no. 5, p. 995–1014, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/beu010

Velte, P. 2016, ‘Women on management board and ESG performance’, Journal of Global Responsibility, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 98–109, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGR-01-2016-0001

Wang, M. & Kelan, E. 2013, ‘The gender quota and female leadership: Effects of the Norwegian gender quota on board chairs and CEOs’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 117, no. 3, pp. 449–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1546-5

Weinert, N. 2018, ‘How women leaders can promote sustainability initiatives’, Senior Projects, vol. 9. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/lib_seniorprojects/9