Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 15, No. 1

2023

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

Struggling over Serra do Curral: ‘New Extractivism’ Conflicts and Civil Society

Ricardo Carneiro1, Flávia de Paula Duque Brasil2, Bruno Dias Magalhães3,*, Clara de Oliveira Lazzarotti Diniz4

1 Fundação João Pinheiro, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, ricardo.carneiro@fjp.mg.gov.br

2 Fundação João Pinheiro, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, flavia.brasil@fjp.mg.gov.br

3 Fundação João Pinheiro, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, bruno.magalhaes@fjp.mg.gov.br

4 Fundação João Pinheiro, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, claraoliveiradiniz@gmail.com

Corresponding author: Bruno Dias Magalhães, Fundação João Pinheiro, Alameda das Acácias, 70 - São Luiz, Belo Horizonte - MG, 31275-150 Brazil, bruno.magalhaes@fjp.mg.gov.br

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v15.i1.8296

Article History: Received 23/07/2022; Revised 11/01/2023; Accepted 30/01/2023; Published 26/03/2023

Abstract

The Serra do Curral is a mountain range that extends to the municipalities of Belo Horizonte, Sabará and Nova Lima, in Minas Gerais state, Brazil. It is already deteriorated by a long history of mineral extraction not followed by any environmental restoration. Since the 1960’s, Serra do Curral has been an object of many civil society collective actions calling for its preservation. In 2022, the authorization of new mining operation provoked a strong civil society reaction. A coalition of environmental and social activists, alongside new political actors convened in defence of Serra do Curral now demand the immediate revocation of the licence. The present article analyses the current conflict, identifying the main actors, their collective action repertoires, and how those actions play out as the conflict unfolds. The research is conducted through documental inquiry, media coverage analysis and on-site direct observation. Looking into the political struggle around new-extractivism conflicts, we argue, can provide important data and insights about resistance and the developing of alternatives.

Keywords

New Extractivism; Civil Society; Social Movements; Environmental Movements; Repertoires of Collective Action

Introduction

The term ‘new extractivism’ has gained prominence in the Latin-American and Brazilian debates after the 2000s. It points to a renewed emphasis on primary activity in the economy by progressive governments and its multidimensional impacts through environmental and social expropriation, as well as the degradation of entire territories and the affected populations’ lifestyles. Accordingly, it has brought about many conflicts between the state, the mining companies and civil society.

Brazil is one of the biggest mineral commodities exporters in the world, mostly due to its natural resources, lack of federal regulation, and fiscal incentives for mining activity. The State of Minas Gerais – which carries the mining legacy in its very name1 – stands out by its long history of dependence on extractivism and has recently been the site of catastrophic dam breakdowns in Mariana (2015) and Brumadinho (2019) with major environmental and societal impacts and repercussions.

In the state government, the Mining Activity Chamber of the Conselho Estadual de Política Ambiental (Environmental Policy Council – COPAM) is responsible for allowing such activities. Despite the opposition of civil society representatives, the Council has recently authorized the installation of new mining operations in an area located at the Serra do Curral in the municipality of Nova Lima, on the border with Belo Horizonte, the Minas Gerais state capital.

The mining site licensed in 2022 to the company Tamisa Mineração S.A., from now on Tamisa, is expected to have three pits, roads, tailing-containing dams and administrative buildings. The area is surrounded by Belo Horizonte’s elite neighborhoods2 and informal settlements, including a Quilombo, an African-Brazilian traditional settlement protected by the Brazilian Constitution. The area is also covered by the remnants of the native Atlantic Forest and is just 150m (492ft) from the Belo Horizonte Peak, whose outline is formally protected as cultural heritage.

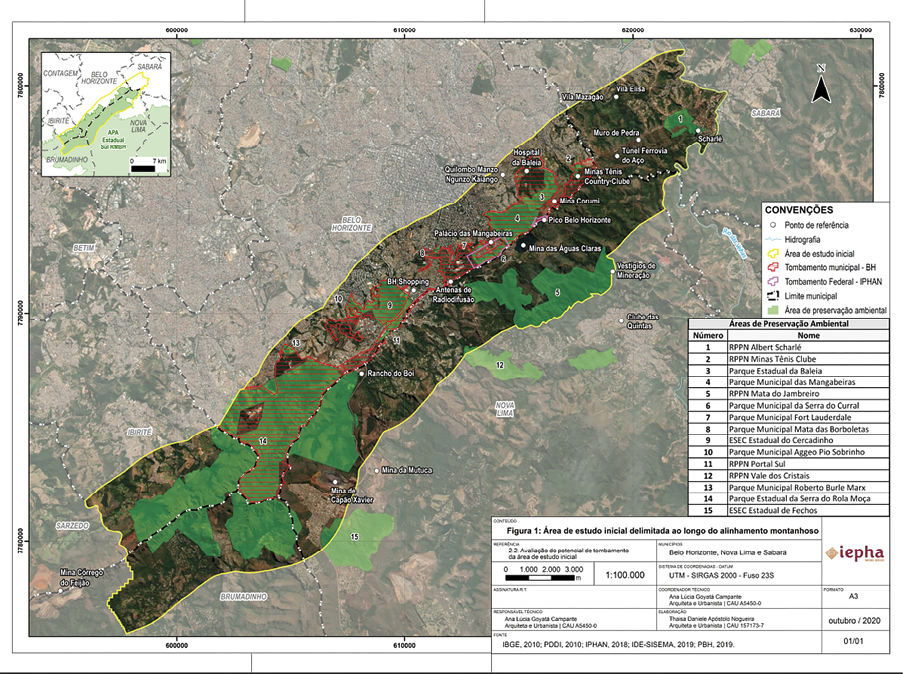

The Serra do Curral is a mountain range that extends for 14km covering the municipalities of Belo Horizonte, Nova Lima and Sabará (see Figure 1, below). Besides its environmental value and its biodiversity, the Serra do Curral has a deep rooted cultural and symbolic significance for the region. Framing the landscape of Belo Horizonte as a central reference, the mountain was elected as a city symbol and has been featured on the city flag since 1995.

Source: IEPHA 2020, p. 29.

Nevertheless, the Serra do Curral has already been degraded by a long history of mineral extraction not followed by any environmental restoration. The mining activities in the region date back to the 19th century, albeit specifically from the 1960s onwards iron ore mining began to take place along the mountainous alignment of the Serra do Curral. Moreover, around the area in Belo Horizonte and, further on, in Nova Lima, there has been a process of urban expansion, densification and verticalization that has intensified over the following decades.

As a result, notably since the 1980’s, civil society actors have rallied in defence of Serra do Curral through many campaigns and contentious collective actions calling for its preservation. These mobilizations have led to the protection of several areas, including the listing of its silhouette as a registered heritage by the Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico Artístico e Cultural (National Artistic and Historic Heritage Institute -IPHAN) in 1960. On the municipal level, civil society protests and campaigns influenced the local government to create the Conselho Deliberativo de Patrimônio Cultural de Belo Horizonte (Deliberative Council of Cultural Heritage of Belo Horizonte – CDPCM-BH) in 1984. The Council listed Serra do Curral as cultural heritage of the municipality in 1991. A decade later, in 2003, it further detailed the area’s protected perimeter (IEPHA 2022).

On the state level, a 1600-page-long dossier was elaborated by the State Artistic and Historic Heritage Institute (IEPHA) in 2020 that substantiates the need for the listing of the whole area of Serra do Curral as part of the cultural heritage of the state of Minas Gerais (IEPHA 2020). The report was waiting for the deliberation of the Conselho Estadual de Patrimônio Cultural (State Cultural Heritage Council – CONEP) to be approved, and since then COPAM’s authorization of Tamisa’s new mining operations is in the midst of a judicial and political battle.

This authorization has also provoked a major civil society reaction. A coalition of environmental and social activists, alongside political actors convened in defence of Serra do Curral and demanded the immediate revocation of the mining licence, claiming that it is illegal because it breaches protected land. The conflict mobilizes a constellation of actors against Tamisa mining operation including civil society organizations, social movements, collective coalitions, political parties, politicians, artists, influencers, Belo Horizonte’s Municipality, the Ministério Público Estadual (Minas Gerais’ State Public Prosecutor’s Office – MPMG) and even the major mining company Vale S.A. Together they carry out multiple actions that can provide some insights not only on the actual conflicts caused by new extractivism but also on forms of resistance and the generation of alternatives.

The present article aims to present a comprehensive anatomy of the current conflict, identifying these actors, their performances, and collective action repertoires. We focus on the reconstruction of an historical time frame of the conflict, starting in 2019. Departing from the broader Latin American context of new extractivism, we briefly review the social movement literature to establish a framework capable of understanding the contentious arena established around Serra do Curral. We then examine the acts carried out by civil society, the market, and government actors, including the legislative and the justice system, and how they play out as the conflict unfolds.

Since the analysis is concentrated on an on-going conflict, the research is mostly an exploratory case study. Yet it presents important data about specific struggles generated by new extractivism in more densely urbanized areas and the role played by civil society collective actions. It also advances a hypothesis on the reasons Belo Horizonte’s case has been able to actually prevent Serra do Curral’s new mining exploration, representing real resistance to corporate and government interests. Two challenges emerge from that hypothesis, the first one regarding resistance in less populated areas and the second one regarding the development of viable alternatives to new extractivism as a political and economic paradigm.

New extractivism and its impacts

There is a relative consensus in the literature (Acosta 2016; Andrade, D. 2022; Gudynas 2010, 2012; Svampa 2016, 2019) that ‘dependence on the extraction of natural resources as a vector of economic growth’ (Milanez & Santos 2013, p. 123) is a striking feature of the history of Latin American countries, as well as of other regions. This centrality of the exploitation of natural resources for regional economies can be encapsulated in the idea of extractivism.

Extractivism is understood as ‘a set of development strategies anchored in a group of economic sectors that remove a large volume of natural resources for commercialization after no, or almost no, processing’ (Milanez & Santos 2013, p. 121). Those sectors are usually based on regional enclaves, meaning their activities are concentrated in some areas that are characterized by differences in a variety of variables such as resource availability, infrastructure, supply chains but also social, cultural and sometimes political features. Extractivism involves intensive activities in the appropriation and extraction of natural resources (Gudynas 2010; Svampa 2019), encompassing both minerals, oil and gas, as well as agricultural, forestry and fishing activities (Acosta 2016; Andrade, D. 2022), mostly exported in the form of products with a low degree of processing (Acosta 2016), designated as commodities.

From a Latin American perspective, extractivism as a strategy of accumulation and/oran engine for national growth is subject to criticism from two main directions. On the one hand, despite being established as a dynamic component of the regional productive structure, these sectoral activities did not enable social and economic development capable of overcoming poverty and inequality. Gudynas (2010, p. 1) underlines the existence of a wide body of evidence about the limited contribution of extractivism to what he calls ‘genuine national development’. Developmental strategies sought by regional governments, especially in the middle of the last century with emphasis on the promotion of industrialization through import substitution, have never actually enrolled countries on the path of sustained economic growth. They were also unable to guarantee decent standards of social welfare.

On the other hand, extractivism is accompanied by deep socio-environmental impacts, given the intensive exploitation of natural resources as an intrinsic characteristic of its activities. As Milanez & Santos (2013, pp. 133) report, there is a ‘great imbalance in the distribution of benefits and losses generated’ by sectoral enterprises, in which most of the negative impacts tend to fall on lower-income extracts from local communities, while the benefits are mainly appropriated by the companies, some of them international, and national governments.

With the interpenetration of neoliberalism in Latin American countries in the final decades of the 20th century, the design of development strategies pivoted to the private sector. This inflection reflects the emphasis given by neoliberal ideology to reducing the role of the State in the economy which, in Latin America, is largely associated with the implementation of the prescriptions of the so-called Washington Consensus. This reformism can be depicted as ‘a policy package which had the free market economy as its guiding principles, and macroeconomic stability (through the control of inflation) as its explicit goal’ (Andrade, D. 2022, pp. 799). Some authors consider neoliberalism from its political aspects as a process of institutional retrenchment but also as narratives that privileged supporting established corporate power from democratic impingement (Streeck 2017). From the perspective of neoliberalism, the coordination of the economy is delegated to the dynamics of the market, presumably efficient, preventing the adoption of active public policies to promote development by national governments, who became unwilling and unprepared to defend local action against corporate activities’ impacts3.

Neoliberal reformism, however, declines in the region in the transition to the 21st century, with the rise of progressive governments from the left or center left, which takes place within the scope of a broader return of democratic institutions (Andrade, D. 2022). The process coincides with a vigorous rise in commodity prices on the international market, which greatly favors extractive activities in which Latin American countries enjoy undeniable comparative advantages. It is in this context that progressive Latin American governments resume their developmental political agendas, deepening the extractive model under the argument that revenues generated by the commodities exportation were necessary ‘to finance social investment’ (Lang 2016, p. 24).

Nonetheless, the tensions and social conflicts raised by sectoral activities gradually bring back extractivism to the discussion of developmental agendas implemented in the region. Understood as a concept ‘endowed with dimensions and with a great mobilizing capacity’ (Svampa 2019, p. 12) it is then reconceptualized as neo-extractivism, having in Gudynas (2010, 2012, 2016) a referential author (Chagnon et al. 2022; Milanez & Santos 2013; Svampa 2016, 2019). For Gudynas (2010, 2012), progressive Latin American governments promote ‘a new type of extractivism, as much because of its components as because of the combination of old and new attributes’ (2010, pp. 13). This combination gives meaning to the concept’s resignification, even if the phenomenon per se does not present ‘substantive changes in the current [economic] structure of accumulation’ (Acosta 2016, p. 66).

According to Gudynas (2010), ‘neo-extractivism serves a subordinate and functional role in inserting itself into [the] commercial and financial globalization’ that characterizes contemporary capitalism. As such, it not only maintains but deepens territorial fragmentation, creating ‘relegated areas and extractive enclaves associated with global markets’. While the extractive enclaves are territories with strong state presence, they are usually surrounded by areas with limited civil rights protection, health service and education. Moreover, enclaves are connected with cities and ports through transportation corridors that divide the territory.

Reproducing striking features of the old extractivism, ‘beyond the ownership of resources, rules, and the functioning of productive processes are displaced by competition, efficiency, maximization of profits, and externalization of impacts’. It is not surprising, therefore, that ‘social and environmental impacts in extractive sectors continue, and in some cases have been aggravated’. One of neo-extractivism’s main distinguishing aspects when compared to the old version is that ‘the state captures (or tries to capture) a greater proportion of the surplus generated by the extractive sectors, and part of these resources finances social programs, with which the state gains new sources of social legitimization’ (Gudynas 2010, p. 13). This repositioning of the State has been done through tax and regulatory system reforms, in the sense of ‘a larger presence and a more active role’ that is depicted by Andrade, D. (2022, p. 794) as ‘a style of resource management considered to be neo-developmentalist and post-neoliberal in character’. Progressive political leaders in Latin America claim that they are able to establish a proper flow of resources from extractive activities to social programs. Indeed, as Gudynas affirms, ‘they present themselves as the only ones who can handle extractivism efficiently in the future, who can adequately redistribute the wealth it generates (2010, p. 10).

This social financing has generated a legitimation that is, however, limited in scope, both from an economic perspective and, above all, from a socio-environmental perspective. Regarding the economic perspective, the expectation that the opportunities created by the favorable cycle for commodities in the 21st century and the more active role of the State could lead to development turned out to be an illusion (Svampa 2019). According to Covarrubias and Raju (2020, p. 221), the neo-extractivist model ‘has generated (...) a poorly diversified productive structure highly dependent on the international market’, reproducing the results of the development strategies adopted in the region in the 20th century. Regarding the socio-environmental perspective, the expanded scale of intensive activities in the exploitation of natural resources deepens the impacts on the environment with ‘disastrous effects on the environment and territories (...), creating new hazards and exposure settings, and thus making the populations more vulnerable’ (Covarrubias & Raju 2020, p. 221). This process has raised growing socio-environmental tensions, resulting ‘in severe territorial conflicts due to the consequences of ecological predation and human rights violations’ (Covarrubias & Raju 2020, p. 224).

The limits of state capacity to provide adequate environmental regulation are evident in the ‘explosion of socio-environmental conflicts’ (Svampa 2016, p. 143) involving, on the one hand, the government and companies that exploit natural resources, and, on the other, a varied set of social actors, such as ‘indigenous-peasant organizations, socio-territorial movements, environmental collectives’ (Svampa 2019, p. 12), among others. At the same time, the questioning of neo-extractivism gives rise to the generation of ‘other languages and narratives’, mobilized in defense of values such as ‘land, territory, common goods, and nature (Svampa 2019, p. 12). In this defense of natural resources, the concept of the commons stands out. According to Svampa (2016, p. 149), it ‘integrates different visions that support the need to keep out of the market those resources that, because of their natural, social and/or cultural heritage character, have value that transcends any pricing’. The notion as such refers ‘to the idea of the common, of what is to be shared, and, therefore, to the very definition of the community or the communitarian dimensions’ (Svampa 2016, p.149).

Returning to Gudynas, the author argues about the need for a transition to a post-extractive development strategy, which has, at its core, the fulfillment of ‘two indispensable conditions: eradicating poverty and preventing further losses of biodiversity’ (Gudynas 2016, p. 189). In this inflection, a set of ideas takes shape under the broader label of ‘buen vivir’ or ‘good living’. Starting from a ‘criticism of the ideology of progress and economic growth’, ‘buen vivir’ postulates the defense of an idea of quality of life ‘that transcends the material, individual and anthropocentric dimension for the benefit of a certain spiritual, and communitarian, well-being that extends to all nature’ (p. 182). The transition to good living requires, in the terms set out by Gudynas (2016, p. 202), ‘a social regulation – that is, anchored in civil society – which would be applied both to the market and to the State’.

At the end of the day, the critique of new-extractivism highlights the inability of progressive governments in Latin America to establish path-breaking alternatives to the region’s historical economic dependence on natural resources and the associated extractive activities. In fact, it denounces progressivism’s embracing of ‘primarization of the economy’ as a renewed narrative in which it is used to financially support social programs. If the region’s States have indeed managed to redirect and redistribute resources from corporations to social policy, evidence indicates that they still lack capacity not only to regulate private activities but also to build a more social-based governance around the ideals of wealth, nature, and the commons expressed in the buen vivir philosophy. In face of those shortcomings, some authors call for an expansion of the concept of extraction instead of talking about new-extractivism per se. According to Gago and Mezzadra (2018), new extractivism contributes to assign a mere passive position to poor urban populations as it highlights state subsidies as connectors to extractive economy and peripheral urban territories (p. 577). Junka-Aikio and Cortes-Serverino (2017), in their turn, claim that we should also analyze extractivism from the perspective of cultural studies. Taking different paths, both texts advocate for an emphasis on the category of exploitation in order to advance renewed alternatives not only to economic but also political extractivism.

The present paper finds inspiration in those attempts that go beyond the new-extractivism critique without rejecting its importance. The current analysis turns to the political aspect of the social conflicts that emerge from new-extractive contexts, especially the performances summoned by social movements. Repertoires of contentious activities as well as interaction between civil society and the State, we argue, constitute another important site to look for resistance and alternatives for development. The next section briefly examines the literature on social movements, in order to establish a framework capable of understanding such actions.

Performances, repertoires and public arenas

Social movements are usually approached through various intellectual questions (Della Porta & Diani 2006). This paper is concerned with the links between the social, political, and cultural context and the forms taken by collective action. According to this perspective, the historically and spatially situated environment of an issue is one important aspect of contemporary society and politics, and as such will influence the available repertoires of political action (Tilly 1978). A repertoire is to Tilly a set of performances a group might use for making claims of different types in particular historical periods. A petition, a demonstration or a strike are examples of performances enacted in a repertoire of direct contentious action, for example (Tilly 2006). In this paper, we use the terms collective action, repertoires and performances in a loose definition and understand neo-extractivism as the Serra do Curral conflict’s milieu in which the different actors establish their strategic moves toward an intended outcome.

According to Della Porta and Diani (2006), repertoires are finite. They evolve slowly and are passed from one generation to another. They are also a ‘byproduct of everyday experiences’ (p. 182), in the sense that ‘they are what people know how to do when they want to protest’. Despite that, actors can innovate marginally, establishing different performances derived from the diverse dilemmas they face when making the difficult, but crucial decision about the form that the action should take. Those dilemmas are both built in and solved by the political process (Tilly 1978; McAdam 1982).

While purposeful, however, social movements are not just rational, i.e. their actions are not a product of a pure strategic calculation, they are also embedded in a cognitive process in which the actors provide different understandings of available opportunities (Diani 1996) and deliver an interpretation scheme – or frame – to understand and narrate the world and its occurrences (Snow & Benford 1992).

In this sense, collective action also involves feelings and emotions. These deal with what Jasper (1997) calls the pleasure derived from social life, such as a sense of community, cooperation, solidarity, competition etc. Sometimes they are enacted by fear, anger, sense of injustice, and indignation. Other times they mobilize positive affections, social bonds, and a sense of biographical personality (Jasper 1997). As such, the conflict also depends on – and brings about – the development of group identity, that relationally positions the activists as they make sense of reality, diagnose social injustices, and establish their claims (Melucci 1996, Poletta & Jasper 2001).

Assuming a relational perspective, Cefaï (2017) draws attention to an ecology of the public experience. Experience is the disturbance brought about by affective, sensible, or evaluative proof that perturbates the everyday life. The experience is not always articulated within words and concepts. Before that it is felt as an agitation, uneasiness, distress and so on. It is, then, a proof of an aesthetic and practical sort. It is also transactional with its environment, that is, it is relationally defined within a network of symbolic devices, legal, institutional, scientific, mediatic, among others, which constitute a public culture that carries sedimented answers to previous problematizations.

Within this ecology, the disturbances are put in motion through a collective experience process, turning themselves into public issues. This process requires a capacity of feeling together, which is realized through the collective action. In this sense, ‘the constitution of a public issue is not only in the action itself, but also in suffering (padecer) and feeling sympathy (compadecer)’ (Cefaï 2017, p. 191). According to the author, a public arena is established around this publicized problematic situation. This arena is made of a bricolage of different social logics. It is not properly a market, ruled by the logic of profit in transaction, neither is it a field, ruled by domination between social groups, nor an agora, ruled by deliberation. It is a complex, interactive and generative process aimed at a public teleology supported by collective interpretation, talking, and action through the problematization and solution of public issues (Cefaï 2017).

That said, we can make sense of the numerous actions that temporally and spatially constitute the anatomy of Serra do Curral’s conflict as performances enacted by a multitude of different actors that generate purposeful strategies, collective identities, discursive narratives, frames, and experiences within the same public arena. Despite local concerns, that arena is associated with national development and global markets, for it is part of the neo-extractive paradigm. The performances, in their turn, are routines, marginal innovations, or modulations of the existent repertoires of collective action and take advantage not only of the structures of political opportunities (see Tarrow 2009; Tilly 2008;) and resource mobilization capacity (see McCarthy & Zald 1977) but are embedded in an institutionalized trajectory of experiences – a field of experiences, according to Cefaï (2017) – and a public culture.

Let us take a group of performances enacted by Brazil’s famous Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Terra (Landless Worker’s Movement – MST) as an illustration. According to Martins (2000), MST developed an efficient strategy to pressure the Brazilian government to deploy land reform by seizing an opportunity provided by the national land law which states that private property can be confiscated when, among other reasons, it is not cultivated (whenever the land is not designated an environmental protection zone). Historically, MST activists were able to settle in several unproductive areas, turning occupations into real collective work and living sites, equipped with schools and technology. The movement is now well-known not only because the successful outcomes from its settlement strategy but also for its cooperative, self-managed, and sustainable agricultural production, as well as for its participative practices. MST has effectively articulated an alternative project to land reform and to agriculture in a more general way, inspiring policies, narratives, and identities.

Importantly enough, repertoires are not always contentious, including protests, occupations, and direct action (McAdam et al. 2001). As the Brazilian literature has shown, they embrace a broader notion of collective action, such as institutionalized participation, the politics of proximity, and bureaucratic activism (Abers, Serafim & Tatagiba 2014) as well as the mobilization of law at the judicial system (Losenkann 2013). These repertoires have benefited from an era of unprecedented State permeability toward social movements in Brazil and have managed to establish more or less durable ‘agency domains’, i.e. sedimented institutional spaces that favor specific competencies and capacities (Lavalle et al 2019), not only within the government itself but also in the judicial system (Losenkann 2013).

Environmental institutions make a good example here. According to Araújo (2013), Brazil has a vast, structured, and rigorous legislation regarding environment protection. This very organized system of laws is in fact held in check and supplemented by a number of participatory institutions, in particular collegiate bodies in which civil society and environmental movements exercise their voice, such as the Conselho Nacional de Meio Ambiente (Environment National Council – Conama)4. Yet, even this institutional tangle is not sufficient to keep the Brazilian environmental policy safe from troubled water. What actually goes on is that policy is a result of moves and performances played out by different political actors who establish coalitions and dispute hegemony within the policy community. Environmental coalitions in Brazil involve civil society, politicians, and bureaucratic technocracy who shape policy institutions not only from the outside, but also from within.

The broadening of the idea of repertoire beyond the strict notion of conflict seems plausible also outside the Brazilian context, as environmental activism shows. Rootes and Nulman (2014, pp.2) point out that the environmental movement is ‘highly diverse in its forms of organization and action’. According to the authors, those movements range from direct action, such as protests and demonstrations, to ‘the often publicly invisible actions of bureaucratized formal organizations that lobby governments or work in concert with governments and/or corporations’. They note, however, that environmental movements usually depend on mass media coverage, the visibility of environmental issues, and political opportunities to be successful, as they have fewer resources than industry groups.

Accordingly, collective action deployed by social movements can be understood in terms of repertoires of performances historically situated, strategically oriented, and constitutively experienced. As such, they might be more or less contentious, varying from direct action to institutional participation, including the enactment of bureaucratic activism and the mobilization of the judiciary. As we show below, Belo Horizontes’s Serra do Curral defense is composed of a blend of these forms of collective action. Together, they have assembled different symbolic and institutional components of local resistance. This appears to have been crucial to resistance so far.

Methodological considerations

The research was conducted through documental inquiry, media coverage analysis and on-site direct observation. We aimed at two types of information, each one collected through a different strategy. The first was research on relevant and well-known local and national news channels for the state of Minas Gerais: Hoje em Dia, Estado de Minas, O Tempo, Globo and affiliates; the official State news repositories of: Minas Gerais Legislative Assembly, Minas Agency, Brasil Agency, Belo Horizonte City Council and Belo Horizonte City Hall were also used. Finally, to monitor collective actions, we also use the ‘Brasil de Fato’ portal, which, in its editorial line, notably covers perspectives of social movements. For all these repositories, the research used the term ‘Serra do Curral’ as a keyword and limited the dates of the news weekly between 04/18/2022, the week before the COPAM vote, and 07/15/2022, due to research time limitations. In the search, we found articles related with other mining conflicts in the same region, but we have only selected those that specifically focused on Tamisa. We also found more than one article addressing the same fact. In that case, we opted for choosing the one that was published first. In total 95 articles were selected, mostly from the local news channels ‘O Tempo’, ‘Hoje em Dia’, and ‘Estado de Minas’. Those were also concentrated in the first weeks of the conflict, indicating that the conflict started as local one and escalated to become a national agenda.

The second research strategy, used mostly to map the actions of civil society, was based on the investigation of events published by the members of ‘Tira o Pé da minha Serra’ campaign on ‘Whatsapp’ group chats. The groups were a campaign strategy to organize, publicize, and disseminate news and actions considered relevant by the local activists. The Whatsapp groups started to be created and advertised by the campaign on the 04/22/2022, building a dissemination network constituted by about 10 groups with more than 150 participants each. We monitored the posts of one of those groups on the 04/26/2022 and analyzed data until 07/15/2022. It is noteworthy that all the information contained in the research was verified either on news portals, or through collective actions records and/or direct experience, meaning that we have only considered verified chat messages. Using those criteria, we selected 20 events, such as calls for action, denunciations, issuing of supporting documents, and reports about collective action taken. The inquiry through internet groups made it possible, on the one hand, to map a wider range of collective actions than that published by the media and, on the other hand, to identify, albeit partially and in a non-exhaustive way, activists’ perspectives about the conflict.

More recently, as the struggle’s outcome presented an important turning point with a judicial decision to suspend the operating license of Tamisa, we added three other news articles to our data. Those covered the period from 12/15/2022 to the 01/09/2023.

Civil society and collective action: activisms and resistance

The mining plant of Tamisa in Serra do Curral has set up a broad public arena constituted by multiple social actors, frames, and repertories of collective action. Tamisa was created in 2010 as a fusion of three different mining companies. In 2014, it applied for a 30-year exploration license that was eventually denied and archived. In 2020, Tamisa submitted a new mining project to COPAM, including three different pits, roads, tailing containing dams and administrative buildings at Ana da Cruz, a farm owned by the company in Serra do Curral (Projeto Manuelzão 2022a).

By that time, however, there was a civil society coalition that argued for the protection of Serra do Curral. Created in 2018, the group owned a website called ‘Mexeu com a Serra, mexeu comigo!’5 (UFMG 2018). In 2021, the coalition launched a petition with more than 75,000 signatures aiming to suspend the licensing process and claiming that Tamisa’s mining operations would certainly cause major environment impacts in the region (Brasil de Fato 2021).

Meanwhile, the state Public Prosecutor’s Office issued an official recommendation to CONEP and COPAM to protect Serra do Curral as a cultural heritage based on the Instituto Estadual do Patrimônio Artístico e Cultural (State Historical and Artistic Heritage Institute – IEPHA) dossier. The 1,600-page-long document was requested and financed by the MPMG in 2018 and it corroborated the need for the listing of the whole complex of Serra do Curral as cultural heritage of the state of Minas Gerais (IEPHA 2020). Accordingly, later that year it became a law project in the state Legislative Chamber (ALMG 2021). Mobilization of both COPAM and IEPHA can be seen as early performances of bureaucratic activism.

In December 2021, more than forty environment movements and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) established a new coalition in defense of Serra do Curral. The network was formed by relevant activists, such as Salve Gandarela, S.O.S. Vargem das Flores, Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens (Movement of People Affected by Dams – MAB), Projeto Manuelzão6, among many others. This coalition held a campaign named ‘Save Serra do Curral’ and performed an ‘Acting of Love for Serra do Curral’, a demonstration convened in the Praça do Papa (Pope’s Square) , literally at the feet of the endangered mountain, in order to pressure the state government and mobilize public opinion towards the listing of the whole area (Projeto Manuelzão 2021). The coalition of several social movements using social media advertisement and direct actions was an important demonstration of the strength of the claims. It also created a gravity center that brought together smaller organizations. This was especially important to provide leadership and consultancy to small associations, helping them to file lawsuits, meet policy actors or even mobilizing more sound direct action.

As Tamisa’s application progressed in the beginning of 2022, civil society movements and associations held diverse collective actions aiming to obstruct the mining license process. They created large WhatsApp groups to disseminate information and also to engage supporters in new demonstrations, such as the campaign ‘Tira o pé da minha Serra’7 that produced online graphic material and street posters. Their performances also included thematic Carnival parades and road races. As the coalition enlarged, it organized new petitions to list the Serra as a state heritage and monitored closely COPAM meetings that could discuss the matter. In addition, grassroots associations already harmed by other mining operations expressed their solidarity and denounced the environmental impacts to which they were subjected. Some activists held meetings with legislative and government actors. Some environmental associations such as the Instituto Guaicuy8,the Sustaintability Party (REDE Sustentabilidade), the Belo Horizonte city council and the MPMG also filed lawsuits through the judicial system, prosecuting Tamisa and the municipality of Nova Lima. They argued that the landscape where the mining operations would happen was crucial for the remnant Atlantic Forest and the Pico de Belo Horizonte, whose profile is protected.

On April 29th, COPAM was reconvened to examine the licensing process. The session lasted for 19 hours straight. Although the meeting was public, the online room had limited seats and only some activists were able to attend. At 3 a.m. on April 30th, the Council approved the mining operation license, with 8 votes in favor – 7 from government and industry representatives and one from Sociedade Mineira de Engenheiros (Association of Engineers of Minas Gerais), and 4 against – 3 from civil society representatives and one from Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e Recursos Naturais Renováveis (Environment and Natural Renewable Resources Federal Institute – IBAMA)9 (Queiróz 2022).

Several protests and questioning actions followed the decision, bringing new actors to the arena and broadening once again the defense coalition established around Serra do Curral. Congressmen and Congresswomen from left political parties, notably Partido Socialismo e Liberdade (Socialism and Liberty Party – PSOL) and Partido dos Trabalhadores (Worker’s Party – PT), reported irregularities in the voting process and in the licensing, and asked for MPMG intervention to suspend the mining license (Cruz 2022). The Partido Verde (Green Party – PV), in turn, published the ‘Letter to the people of Minas Gerais: the Serra do Curral belongs to all generations’ (Fórneas 2022), and Partido Rede Sustentabilidade (Sustainability Party – REDE) filed a lawsuit to revoke the operation license (Andrade, J. 2022). In the absence of a larger civil organization coordination, the political parties played an important role by using their position to make possible the negotiation between the environmental activists and the State. Meanwhile the coalition ‘Tira o Pé da Minha Serra’ was enacting public performances such as rallies, public relations, and direct actions. Some State institutions, namely IEPHA and IBAMA kept pressing the State and COPAM to change their decision, another example of bureaucratic activism.

At this point, the Belo Horizonte Municipality and the Minas Gerais Legislative Assembly (ALMG) also joined in holding public hearings, establishing special committees, and issuing legislative projects (Peixoto 2022). A new unexamined aspect was raised when environmental activists and Belo Horizonte bureaucrats warned that Tamisa’s operation could also jeopardize the city water supply (Prates 2022).

Both Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Federal University of Minas Gerais – UFMG) and Pontifícia Universidade Católica (Catholic University – PUC-MG) held broad debates (Monteiro 2022). Many manifestos against the mining plant were made public, signed by artists, Catholic organizations, professional, scientific, and research associations, among others, always demanding the preservation of Serra do Curral (Brasil de Fato 2022; CORECON 2022; MinasMundo 2022).

A new actor came on to the scene when the Quilombo Manzo Ngunzo Kaiango protested and claimed that the community had not been informed, or heard, which was required by law for the approval of this kind of the project. They also denounced the mining operation in Serra do Curral as a cultural genocide of their people (Pires 2022). Based on that claim, Ministério Público Federal (Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office – MPF) filed a lawsuit asking for the invalidation of the whole licensing process. This lawsuit turned out to have major consequences by the beginning of 2023, as shown below.

On May 16th, the coalition ‘Tira o pé da minha Serra’ issued a petition to the state governor and to the judge that was responsible for one of the lawsuits related to the mining license (Pires 2022a). The coalition adopted diverse strategies, such as meetings with Belo Horizonte mayor and Congressmen/women (Peixoto 2022), media mobilization, public interviews, attendance at public hearings, and the already mentioned information spreading through WhatsApp groups and social networks (ALMG 2022).

By that time, several installations appeared in Belo Horizonte’s streets, with wordings such as ‘Save Serra do Curral’ or flyers blaming COPAM’s councilors for being responsible for the mining approval. During May and June, the environment movements continually organized several demonstrations and creative interventions: ALMG had their public spaces occupied; 66 different biking and running groups rode and ran in support of the mountain; and art performances were brought to the traditional Belo Horizonte’s Sunday Street Market. One of these acts, organized by Projeto Manuelzão, gathered children to pick flowers in the Serra do Curral and deliver them to the Judge in charge of the legal action related to the mining license.

All of those actions mobilized some sort of symbolic aspect about how Belo Horizonte’s community felt represented and closely related to the Serra do Curral mountain. To illustrate even more, activists and citizens gathered to ‘hug the mountains’ on June 5th and on three other occasions. Some of those actions were able to also engage national social movements, especially the Movimento pela Soberania Nacional na Mineração (Movement for Popular Sovereignty in Mining – MAM) and the already mentioned MAB, that stood side by side with local organizations such as Salve a Serra do Curral, Salve a Gandarela, Boi Rosado Ambiental, among others (Werneck 2022).

As the issue gained space in the public agenda, a representative of the International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) met with several of the above-mentioned movements. During the meeting, it was publicly stated that Serra do Curral should be protected from mining, otherwise UNESCO would be notified (Gondim 2022; Sampaio 2022).

Conflict’s judicialization and new ramifications

The Serra do Curral protection has until now engaged a great number of civil society members, whose repertoires of action are enacted within a context of neoextractivism in the State of Minas Gerais. A broader constellation of actors also brought together institutional actors with the shared intention of the Serra’s protection: Congressmen and women, left political parties, Belo Horizonte Municipality, State and National Public Prosecution Office, and the judicial system. However, the joint efforts towards both the annulment of Tamisa’s mining license and definitive protection of the Serra do Curral as a cultural heritage were not successful. For this reason, the conflict became increasingly judicialized, collecting uncertain, if not mere ephemeral, results for the activists, with the exception of the Quilombo Manzo lawsuit.

The Municipality of Belo Horizonte played an important role in favor of the protection of the Serra do Curral, using legal means and public relations. Besides several supportive acts – it held a seminar on the impacts of mining (Prefeitura de Belo Horizonte 2022); created an ecological corridor Espinhaço-Serra do Curral with 1.8 thousand hectares (Werneck & Parreiras 2022); conducted studies and proposed the creation of a metropolitan park of Serra do Curral, which has been discussed by state environmental agencies (Estado de Minas 2022; Rezende 2022) – the city government has also filed two lawsuits to suspend the mining license: one in the state court and the other in the federal court, which sent the case back to the state court (Estillac 2022; Mansur 2022).

Two other lawsuits were filed by MPMG: one against the Nova Lima Government and Tamisa, questioning compliance issues on the licensing process (Pimenta 2022); and another against the State Government, IEPHA, and Tamisa, asking for the nullifying of the mining license (Falabela & Mansur 2022). Additionally, MPF filed a lawsuit against the State Government, claiming that the license could not have been granted without the consent of IBAMA, since the mining activity foreshadows the deforestation of Atlantic Forest vegetation (Castro & Falabela 2022; Ferraz & Prates 2022; MPF 2022). Tamisa has also joined the judicial battle in order to maintain its mining license, to complement an attempt to counter the environmentalists’ arguments through paid advertisements in major news portals (Estado de Minas 2022a; Lagôa & Marçal 2022;).

Another lawsuit filed by REDE on July 11th managed to obtain a temporary suspension of Tamisa’s operation, but only until a new meeting was conveyed by CONEP (Araújo & Mansur 2022; Nascimento 2022). Without surprise, CONEP reconvened shortly after and reaffirmed that the license was upheld.

A partial victory for the activists was the State Decree 48,443 of June 14th, which classified the Serra do Curral as being of relevant cultural interest. At the same time as issuing this Decree, the governor of Minas Gerais also recommended the analysis of IEPHA’s dossier to verify the possibility of provisional listing the region as a cultural heritage site. In addition, on June 20th, Ordinance 22/2022, issued by IEPHA, determined the provisional safeguarding of Serra do Curral not only in its portion of Belo Horizonte, already listed by the municipality, but also in Sabará and Nova Lima, where the Tamisa mining plant is located (Manuelzão 2022; Damázio 2022).

On July 12th, 2022, Tamisa appealed the decision and filed a lawsuit to suspend the IEPHA ordinance and the CONEP meeting that would take place the next day. The judicial decision came in six minutes before the commencement of the meeting and the agenda that would probably list Serra do Curral as Cultural Heritage was suspended, as well as the ordinance. The municipality filed an appeal, and the president of the court granted the injunction on the 15th, resuming the provisional protection of the Serra do Curral and reversing the suspension of the discussions related to Serra do Curral protection at new CONEP meetings (Damázio 2022; Nascimento 2022; Projeto Manuelzão 2022).

When the last information was collected for this research’s inquiry on July 15th 2022, the government had managed to maintain the mining operation license. Amidst the escalation of conflicts and litigiousness involving IEPHA and CONEP, the State Government had refused to give up its mining agenda. Nevertheless, two important events followed, worthy of highlights as promising signs that the wind is about to change. On August 5th, the Minas Gerais State Court suspended all mining activities in Serra do Curral, not only Tamisa’s, until the discussions for the landscape’s protection legislation has reached a final decision. On December 15th, the Federal Court decided to suspend Tamisa’s license after the Manzo Ngunzo Kaiango claim, based on treaties from International Labor Organization to which Brazil is a signatory. Exposed to immense political pressure after the collective renunciation from the Civil Society Members of their seats on COPAM and legally bound by the judicial decisions, the State Government was forced to suspend the license (Camilo 2023; Mansur & Borges 2022; G1 Minas 2022).

With the conflict still at full throttle, it is hard to anticipate a definitive outcome. Yet, activists can so far claim to be successful in their resistance, making Serra do Curral already worthy of attention from academic research.

Conclusions

The mining license for Tamisa’s operations in Serra do Curral issued by CONAM on 30th April 2022 triggered a series of reactions that reignited the debates around the region’s inherited cultural and environmental value. In this paper, we argued that amidst a context of increasing new extractivism in Latin America, the Serra do Curral issue constituted a relevant public arena of activism, resistance and judicialization. In the past few months, that arena has widened in the number of actors whose repertoires were brought to the present analysis in an attempt to provide an anatomy of the current conflict. Considered together, they deepen the knowledge on the very specific ecology that emerged as the identities, strategies, narratives, frames, and experiences of an ever-increasing civil society coalition was able to problematize and, so far, prevent the environmental impacts that would most probably destroy the Serra.

The roles played by the Municipality of Belo Horizonte, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, both state and federal (MPMG and MPF), Congressmen and women, and political parties in a conflict that has been increasingly judicialized stand out. With the conflict recently circumscribed in the institutional arena of the judiciary system, the results are still uncertain. To a large extent, however, the judicial acts seemed to be mostly in favor of the mining company, which at the end of the day is able to employ greater resources in order to secure its operations. Minas Gerais history and the overall context of new extractivism also create a lock-in situation in which environmental protection, and economic growth and development are opposed.

Yet a major victory was reached when Minas Gerais State Government suspended Tamisa’s mining license in response to a judicial process that seeks to protect traditional population rights supporting the claim that civil society has until now shown creative resistance and opposition by deploying a diverse range of actions. In this sense, we believe that the Serra do Curral arena can provide important lessons on the conflicts caused by new extractivism as it gets closer to more dense urban areas. The case indicates that resistance was effective insofar as social movements were able to blend symbolic mobilization, direct action, and institutional activism. In this scenario, repertoires of bureaucratic activism and judicial prosecution go hand-in-hand with broader demonstrations that appeal to the Serra’s intrinsic cultural value as related to the identity and belonging of Belo Horizonte’s citizens.

If this hypothesis is correct, however, it points to at least two challenges. The first speaks to increasing difficulties in preventing new-extractivism’s socio-environmental impacts that occur on the most distant, fragmented, and less densely populated territories, far from the eyes of a strong, albeit sometimes latent, civil society. The second challenge refers to the complexity of going beyond resistance itself toward developing real path-breaking alternatives to new-extractivism. Indeed, the struggle depicted in the case has focused only on the preventing aspect, which is in itself hard and complicated enough. To promote alternatives, movements and States will need to reinvent themselves, looking into new repertoires, such as those related to the commons and to popular economy.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support of Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais and Fundação João Pinheiro.

References

Abers, R.; Serafim, L. & Tatagiba, L. 2014, ‘Repertórios de interação estado-sociedade em um estado heterogêneo: a experiência na Era Lula’, Dados [online], vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 325-357. https://doi.org/10.1590/0011-5258201411

Acosta, A. 2016, ‘Extrativismo e neoextrativismo: duas faces da mesma maldição’, In: Diger, G. & Pereira Filho, J. (eds.). Descolonizar o imaginário: pós extrativismo e alternativas ao desenvolvimento, Fundação Rosa Luxemburgo, São Paulo, p. 46-87.

Andrade, D. 2022, ‘Neoliberal extractivism: Brazil in the twenty-first century’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, v.49, n.4, p. 793-816. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2022.2030314

Andrade, J. 2022, ‘Rede Sustentabilidade aciona Justiça para suspender permissão de mineração na Serra do Curral, em BH’, G1 Minas, 2022-05-01. https://g1.globo.com/mg/minas-gerais/noticia/2022/05/01/rede-sustentabilidade-aciona-justica-para-suspender-permissao-de-mineracao-na-serra-do-curral-em-bh.ghtml

Araújo, A. & Mansur, R. 2022, ‘Justiça suspende proteção provisória da Serra do Curral e discussão sobre tombamento’, O Globo, 2022-07-13. https://g1.globo.com/mg/minas-gerais/noticia/2022/07/13/justica-suspende-protecao-provisoria-da-serra-do-curral-e-discussao-sobre-tombamento.ghtml

Araújo, S. M. V. G. D. 2013, Política ambiental no Brasil no período 1992-2012: um estudo comparado das agendas verde e marrom. PhD Dissertation. Universidade de Brasília, Brasilia.

Assembleia Legislativa de Minas Gerais (ALMG) 2022, ‘Comissão visita área a ser explorada na Serra da Curral’, ALMG, 2022-05-06. https://www.almg.gov.br/acompanhe/noticias/arquivos/2022/05/06_administracao_publica_visita_serra_curral

Assembleia Legislativa de Minas Gerais (ALMG) 2021, Acrescenta artigo ao Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias da Constituição do Estado, Proposta de Emenda Constitucional n°67, ALMG. https://www.almg.gov.br/atividade_parlamentar/tramitacao_projetos/texto.html?a=2021&n=67&t=PEC

Brasil de Fato 2021, ‘MG: ambientalistas fazem abaixo-assinado para suspender mineração na Serra do Curral’, Brasil de Fato, 2021-03-24. https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2021/03/24/mg-ambientalistas-fazem-abaixo-assinado-para-suspender-mineracao-na-serra-do-curral

Brasil de Fato 2022, ‘Economistas mineiros divulgam manifesto contra a mineração na Serra do Curral’, Brasil de Fato, 2022-05-05. https://www.brasildefatomg.com.br/2022/05/05/economistas-mineiros-divulgam-manifesto-contra-a-mineracao-na-serra-do-curral

Camilo, J.V. 2023, ‘Governo publica suspensão da licença da Tamisa para minerar na serra do Curral’, O Tempo, 2023-01-05. https://www.otempo.com.br/cidades/governo-publica-suspensao-da-licenca-da-tamisa-para-minerar-na-serra-do-curral-1.2792256

Castro, M. & Falabela, C. 2022, ‘Serra do Curral: MPF entra com ação pedindo suspensão das licenças concedidas à Tamisa’, G1 Minas, 2022-06-21. https://g1.globo.com/mg/minas-gerais/noticia/2022/06/21/serra-do-curral-mpf-entra-com-acao-pedindo-suspensao-das-licencas-concedidas-a-tamisa.ghtml

Cefaï, D. 2017, ‘Públicos, problemas públicos, arenas públicas: O que nos ensina o pragmatismo (Part I)’, Novos Estudos, CEBRAP, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 187-213. https://doi.org/10.25091/S0101-3300201700010009

Chagnon, C. W., Durante, F., Gills, B. K., Hagolani-Albov, S. E., Hokkanen, S., Kangasluoma,S. M. J., Konttinen, H., Kröger, M., LaFleur, W., Ollinaho, O. & Vuola, M. P. S. 2022, ‘From extractivism to global extractivism: the evolution of an organizing concept’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, vol.49, no.4, p. 760-792. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2022.2069015

CORECON 2022, ‘Nota do Corecon-MG e do Sindecon-MG sobre mineração na Serra do Curral’, Portal CORECON MG, 2022-05-05. https://corecon-mg.org.br/notaserradocurral/

Covarrubias, A. & Raju, E. 2020, ‘The politics of disaster risk governance and neo-extractivism in Latin America’. Politics and Governance, vol. 8, no. 4, p. 220–231. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i4.3147

Cruz, M. 2022, ‘Dia do Trabalhador: ato de movimentos sociais pede “Fora Bolsonaro” em BH’, Estado de Minas, 2022-05-01. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/politica/2022/05/01/interna_politica,1363502/dia-do-trabalhador-ato-de-movimentos-sociais-pede-fora-bolsonaro-em-bh.shtml

Damázio, M. 2022 ‘Mineração na serra do Curral vira uma eterna queda de braços judicial’, O Tempo, 2022-07-15. https://www.otempo.com.br/cidades/mineracao-na-serra-do-curral-vira-uma-eterna-queda-de-bracos-judicial-entenda-1.2700208

Della Porta, D. & Diani, M. 2006, Social Movements: An Introduction, 2nd ed., Blackwell Publishing, Hoboken.

Diani, M. 1996, ‘Linking mobilization frames and political opportunities: Insights from regional populism in Italy’, American Sociological Review, no.61, pp. 1053–1069. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096308

Estado de Minas 2022, ‘Avançam as articulações para a criação do Parque Metropolitano’, Estado de Minas, 2022-05-24. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/gerais/2022/05/24/interna_gerais,1368659/avancam-as-articulacoes-para-a-criacao-do-parque-metropolitano.shtml

Estado de Minas 2022a, ‘Tamisa fala sobre os mitos relacionados à mineração na Serra do Curral’, Estado de Minas, 2022-05-06. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/patrocinado/tamisa/2022/05/06/noticia-patrocinado-tamisa,1364759/tamisa-fala-sobre-os-mitos-relacionados-a-mineracao-na-serra-do-curral.shtml

Estillac, B. 2022, ‘Ação da PBH contra mina na Serra do Curral vai para a Justiça Estadual’, Estado de Minas, 2022-05-27. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/gerais/2022/05/27/interna_gerais,1369553/acao-da-pbh-contra-mina-na-serra-do-curral-vai-para-a-justica-estadual.shtml

Falabela, C & Mansur, R. 2022, ‘Ministério Público entra com nova ação na Justiça pela suspensão da mineração na Serra do Curral’, G1 Minas, 2022-05-06. https://g1.globo.com/mg/minas-gerais/noticia/2022/05/06/ministerio-publico-entra-com-nova-acao-na-justica-pela-suspensao-da-mineracao-na-serra-do-curral.ghtml

Ferraz, B. & Prates, V. 2022, ‘Serra do Curral: TJMG nega recurso do MP para barrar mineração’, Estado de Minas, 2022-05-11. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/gerais/2022/05/11/interna_gerais,1365677/serra-do-curral-tjmg-nega-recurso-do-mp-para-barrar-mineracao.shtml

Fórneas, V. 2022, ‘PV entra com recurso para barrar mineração na Serra do Curral: “Símbolo de BH”’, O Tempo, 2022-05-05. https://www.otempo.com.br/cidades/pv-entra-com-recurso-para-barrar-mineracao-na-serra-do-curral-simbolo-de-bh-1.2663870

G1 Minas 2022, ‘Conciliação na Justiça de MG suspende mineração na Serra do Curral até fim das discussões sobre tombamento’, G1 Minas, 2022-08-05. https://g1.globo.com/mg/minas-gerais/noticia/2022/08/05/conciliacao-na-justica-de-mg-suspende-mineracao-na-serra-do-curral-ate-fim-das-discussoes-sobre-tombamento.ghtml

Gago, V. & Mezzadra, S. 2017, ‘A critique of the extractive operations of capital: toward an expanded concept of extractivism’, Rethinking Marxism, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 574-591, https://doi.org/10.1080/08935696.2017.1417087

Gondim, L. 2022, ‘Serra do Curral pode ter alerta internacional de risco de órgão da Unesco’, Estado de Minas, 2022-06-29. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/gerais/2022/06/29/interna_gerais,1376854/serra-do-curral-pode-ter-alerta-internacional-de-risco-de-orgao-da-unesco.shtml

Gudynas, E. 2010, ‘The New extractivism of the 21st century: ten urgent theses about extractivism in relation to current South American progressivism’, Americas Program Report, Washington, DC.

Gudynas, E. 2012, ‘Estado compensador y nuevos extractivismos: las ambivalencias del progresismo sudamericano’, Nueva Sociedad, no. 237, p. 128–146.

Gudynas, E. 2016, ‘Transições ao pós-extrativismo: sentidos, opções e âmbitos’ In: Diger, G.; Pereira Filho, J. (Eds.). Descolonizar o imaginário: pós extrativismo e alternativas ao desenvolvimento, Fundação Rosa Luxemburgo, São Paulo, pp.174-213.

IEPHA 2020, Dossiê de tombamento da Serra do Curral, Belo Horizonte.

Jasper, J. 1997, The Art of Moral Protest: Culture, Biography, and Creativity in Social Movements, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226394961.001.0001

Junka-Aikio, L. & Cortes-Severino, C. 2017, ‘Cultural studies of extraction’, Cultural Studies, vol. 31, nos 2-3, pp. 175-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2017.1303397

Lagôa, T. & Marçal, M. 2022, ‘Fiemg defende mineração na Serra do Curral e rebate críticas: “difamaçao”’, O Tempo, 2022-05-03. https://www.otempo.com.br/cidades/fiemg-defende-mineracao-na-serra-do-curral-e-rebate-criticas-difamacao-1.2662451

Lang, M. 2016, ‘Introdução: Alternativas ao desenvolvimento’. In: Diger, G. & Pereira Filho, J. (eds.). Descolonizar o imaginário: pós extrativismo e alternativas ao desenvolvimento, Fundação Rosa Luxemburgo, São Paulo, p. 24-45.

Lavalle, A. G., Carlos, E., Dowbor, M. & Szwako, J. 2019, ‘Movimentos sociais, institucionalização e domínios de agência’, In: Lavalle, A. G., Carlos, E., Dowbor, M. & Szwako, J. (eds.), Movimentos Sociais e Institucionalização: Políticas Sociais, Raça e Gênero no Brasil Pós-transição, EDUERJ, Rio de Janeiro, pp. 21-86. https://doi.org/10.7476/9788575114797.0003

Mansur, R. 2022, ‘Prefeitura de BH entra com ação na Justiça para suspender licenciamento de mineração na Serra do Curral’, G1 Minas, 2022-05-03, Retrieved: 2022-06-04, https://g1.globo.com/mg/minas-gerais/noticia/2022/05/03/prefeitura-de-bh-ajuiza-acao-na-justica-para-suspender-licenciamento-de-exploracao-mineraria-na-serra-do-curral.ghtml

Mansur, R. & Borges, C. 2022, ‘Justiça suspende licenças prévia e de instalação de complexo minerário na Serra do Curral’, G1 Minas, 2022-12-15. https://g1.globo.com/mg/minas-gerais/noticia/2022/12/15/justica-suspende-licencas-previa-e-de-instalacao-de-complexo-minerario-na-serra-do-curral.ghtml

Martins, M. D. 2000, ‘The MST challenge to neoliberalism’, Latin American Perspectives, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 33-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X0002700503

McAdam, D. 1982, Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency: 1930–1970, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

McAdam, D., Tarrow, S. & Tilly, C. 2001, Dynamics of Contention, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511805431

McCarthy, J. D. & Zald, M. N. 1977, ‘Resource mobilization and social movements: A partial theory’, American Journal of Sociology, no. 82, pp. 1212–1241. https://doi.org/10.1086/226464

Melucci, A. 1996, Challenging Codes, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511520891

Milanez, B. & Santos, R. 2013, ‘Neoextravismo no Brasil? Uma análise da proposta do novo marco legal da mineração’, Pós Ciências Sociais, vol.10, no.19, pp. 119-148.

MinasMundo 2022, ‘MinasMundo e Sociedades Científicas em defesa da Serra do Curral’, Projeto MinasMundo, 2022-05-04. https://projetominasmundo.com.br/maquinacoes/minasmundo-e-sociedades-cientificas-em-defesa-da-serra-do-curral/

Ministério Público Federal (MPF) 2022, ‘Serra do Curral: MPF entra com ação para impedir desmatamento ilegal de Mata Atlântica por mineradora’, http://www.mpf.mp.br/mg/sala-de-imprensa/noticias-mg/serra-do-curral-mpf-entra-com-acao-para-impedir-desmatamento-ilegal-de-mata-atlantica-por-mineradora

Monteiro, M. 2022, ‘UFMG e PUC Minas se manifestam contra mineração na Serra do Curral’, Estado de Minas, 2022-05-18. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/gerais/2022/05/18/interna_gerais,1367333/ufmg-e-puc-minas-se-manifestam-contra-mineracao-na-serra-do-curral.shtml

Nascimento, P. 2022, ‘Justiça suspende mineração da Tamisa na Serra do Curral’, O Tempo, 2022-07-11. https://www.otempo.com.br/cidades/justica-suspende-mineracao-da-tamisa-na-serra-do-curral-por-tres-dias-1.2697442

Peixoto, G. 2022, ‘Prefeitura de BH irá à Justiça Federal contra mineração na Serra do Curral’, Estado de Minas, 2022-05-02. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/gerais/2022/05/02/interna_gerais,1363777/prefeitura-de-bh-ira-a-justica-federal-contra-mineracao-na-serra-do-curral.shtml

Pimenta, G. 2022, ‘Ministério Público pede à Justiça suspensão de atividades de mineradora em Nova Lima, na Grande BH’, G1 Minas, 2022-04-26. https://g1.globo.com/mg/minas-gerais/noticia/2022/04/26/ministerio-publico-pede-a-justica-suspensao-de-atividades-de-mineradora-em-nova-lima-na-grande-bh.ghtml

Pires, S. 2022, ‘Serra do Curral: comunidade quilombola se sente ameaçada pela mineração’, Estado de Minas, 2022-05-06. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/gerais/2022/05/06/interna_gerais,1364716/serra-do-curral-comunidade-quilombola-se-sente-ameacada-pela-mineracao.shtml

Pires, S. 2022a, ‘Serra do Curral: artistas entregam manifesto a presidente da ALMG’, Estado de Minas, 2022-05-16. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/gerais/2022/05/16/interna_gerais,1366819/serra-do-curral-artistas-entregam-manifesto-a-presidente-da-almg.shtml

Polletta, F. & Jasper, J. 2001, ‘Collective identity and social movements’, Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 27, pp. 283–305. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.283

Prates, V. 2022, ‘Ambientalistas avaliam hoje riscos em adutora do Rio das Velhas’, Estado de Minas, 2022-06-03. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/gerais/2022/06/03/interna_gerais,1370907/ambientalistas-avaliam-hoje-riscos-em-adutora-do-rio-das-velhas.shtml

Prefeitura de Belo Horizonte 2022, ‘Segurança hídrica da capital e Serra do Curral serão pautas do Ambiente em Foco’, Portal Prefeitura de Belo Horizonte, 2022-06-01. https://prefeitura.pbh.gov.br/noticias/seguranca-hidrica-da-capital-e-serra-do-curral-serao-pautas-do-ambiente-em-foco

Projeto Manuelzão 2021, ‘Ato de amor pela Serra do Curral acontece neste domingo’, UFMG, 2021-12-12. https://manuelzao.ufmg.br/ato-de-amor-pela-serra-do-curral-acontece-neste-domingo-12-de-dezembro/

Projeto Manuelzão 2022, ‘Proteção provisória da Serra do Curral é restabelecida após Prefeitura de BH conseguir liminar’, UFMG, 2022-07-16. https://manuelzao.ufmg.br/protecao-provisoria-da-serra-do-curral-e-restabelecida-apos-prefeitura-de-bh-conseguir-liminar/

Projeto Manuelzão 2022a, ‘Vale produziu estudo usado pela Tamisa sobre potencial minerário da Serra do Curral’, UFMG, 2022-05-10. https://manuelzao.ufmg.br/vale-produziu-estudo-usado-pela-tamisa-sobre-potencial-minerario-da-serra-do-curral/

Queiróz, A. 2022, ‘Copam autoriza mineradora na Serra do Curral; decisão saiu de madrugada’, Estado de Minas, 2022-04-30. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/gerais/2022/04/30/interna_gerais,1363157/copam-autoriza-mineradora-na-serra-do-curral-decisao-saiu-de-madrugada.shtml

Rezende, G. 2022, ‘Serra do Curral pode ter área preservada equivalente a 1,8 mil campos de futebol’, Hoje em dia, 2022-06-27. https://www.hojeemdia.com.br/minas/serra-do-curral-pode-ter-area-preservada-equivalente-a-1-8-mil-campos-de-futebol-1.906960

Rootes, C. & Nulman, E. 2014, ‘The impacts of environmental movements’, In: Porta, D. Della and Diani, M. (eds.), Oxford Handbook of Social Movements. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 729-742.

Sampaio, V. 2022, ‘Comissão de especialistas vistoria Serra do Curral e decide se vai manter “alerta de patrimônio”’, Hoje em dia, 2022-07-7. <www.hojeemdia.com.br/minas/comiss-o-de-especialistas-vistoria-serra-do-curral-e-decide-se-vai-manter-alerta-de-patrimonio-1.908701>

Snow, D. & Benford, R. 1992, ‘Master frames and cycles of protest’, In: Morris, A. and Mueller, C. M. (eds.), Frontiers In Social Movement Theory, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, pp. 133–55.

Streeck, W. 2017, ‘The return of the repressed’, New Left Review, no. 104, pp. 5-18.

Svampa, M. 2016, ‘Extrativismo, neodesenvolvimentista e movimentos sociais: um giro ecoterritorial arumo a novas alternativas?’ In: Diger, G. & Pereira Filho, J. (eds.). Descolonizar o imaginário: pós extrativismo e alternativas ao desenvolvimento, Fundação Rosa Luxemburgo, São Paulo, p. 140-173.

Svampa, M. 2019, Las Fronteras del Neoxtractivismo en América Latina: Conflictos Socioambientales,Giro Ecoterritorial y Nuevas Dependencias, CALAS, Guadalajara. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2f9xs4v

Tarrow, S. 2009, O Poder em Movimento: Movimentos Sociais e Confronto Político, Vozes, Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro.

Tilly, C. 1978, From Mobilization to Revolution, Random House, New York.

Tilly, C. 2006. Why? What happens when people give reasons... and why, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Tilly, C. 2008, Contentious Performances, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804366

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG) 2018 ‘ “Mexeu com a Serra do Curral, mexeu comigo”: Movimento lançado em BH quer lutar contra mineração na serra’ Comunicação UFMG, 2018-06-13. https://ufmg.br/comunicacao/noticias/mexeu-com-a-serra-do-curral-mexeu-comigo

Werneck, N. 2022, ‘Abraço une ambientalistas em defesa da Serra do Curral contra a mineração’, Estado de Minas, 2022-06-05. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/gerais/2022/06/05/interna_gerais,1371288/abraco-une-ambientalistas-em-defesa-da-serra-do-curral-contra-a-mineracao.shtml

Werneck, G. & Parreiras, M. 2022, ‘Decreto criando Corredor Ecológico da Serra do Curral deve sair terça-feira’, Estado de Minas, 2022-06-04. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/gerais/2022/06/04/interna_gerais,1371193/decreto-criando-corredor-ecologico-da-serra-do-curral-deve-sair-terca-feira.shtml

List of Acronyms

ALMG – Assembleia Legislativa de Minas Gerais (Minas Gerais Legislative Assembly)

CDPCM-BH – Conselho Deliberativo de do Patrimônio Cultural de Belo Horizonte (Deliberative Council of Cultural Heritage of Belo Horizonte)

CONAMA – Conselho Nacional de Meio Ambiente (Environment National Council)

CONEP – Conselho Estadual de Patrimônio Cultural (State Cultural Heritage Council)

COPAM – Conselho Estadual de Política Ambiental (Enviromental Policy Council)

CORECON – Conselho dos Economistas de Minas Gerais (Economists Council of Minas Gerais)

IBAMA – Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e Recursos Naturais Renováveis (Environment and Natural Renewable Resources Federal Institute)

ICOMOS – Conselho Internacional de Monumentos e Sítios (International Council of Monuments and Sites)

IEPHA – Instituto Estadual do Patrimônio Artístico e Cultural (State Historical and Artistic Heritage Institute)

IPHAN – Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico Artístico e Cultural (National Artistic and Historic Heritage Institute)

MAB – Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens (Movement of People Affected by Dams)

MAM – Movimento pela Soberania Nacional na Mineração (Movement for Popular Sovereignty in Mining)

MPMG – Ministério Público do Estado de Minas Gerais (Minas Gerais’ State Public Prosecutor’s Office)

MPF – Ministério Público Federal (Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office)

MST – Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Terra (Landless Worker’s Movement)

PSOL – Partido Socialismo e Liberdade (Socialism and Liberty Party)

PT – Partido dos Trabalhadores (Worker’s Party)

PUC – Pontifícia Universidade Católica (Catholic University)

PV – Partido Verde (Green Party)

REDE – Partido Rede Sustentabilidade (Sustainability Party)

UFMG – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Federal University of Minas Gerais)

1 Minas Gerais translates as General Mines.

2 Although it is not common to establish mines near elite areas, Serra do Curral has a long history of mining activities, as explained below. Moreover, the mining is concentrated in the mountains, facing away from Belo Horizonte, and hidden from the eyes of Belo Horizonte’s citizens.

3 The authors thank the reviewers for highlighting this important aspect.

4 In the present case, the Conselho Estadual de Política Ambiental (Environment Policy State Council – COPAM) plays a major role in the struggle for the preservation of Serra do Curral, as we will show below.

5 ‘Messed with the mountain, messed with me!’

6 Group from Federal University of Minas Gerais.

7 Take your foot off my mountain.

8 The Guaicuy Institute is a non-profit organization created by Federal University of Minas Gerais Professors connected with Environmental protection, specially related with water preservation. The name Guaicuy has a ‘Tupi’ origin and it’s one of the Native People’s names for one of the main Minas Gerais river: ‘Rio das Velhas’.

9 The civil society counselors that voted against the mining operation permission were Associação para Proteção do Vale do Mutuca (PROMUTUCA); Fundação Relictos and Associação Brasileira de Engenharia Sanitária e Ambiental (ABES).