Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 14, No. 2

2022

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

Physical and Digital Placemaking in a Public Art Initiative in Camden, NJ

Lili Razi1,*, Devon Ziminski2

1 Rutgers University–Camden, Camden, NJ, USA, lili.razi@rutgers.edu

2 Rutgers University–Camden, Camden, NJ, USA, devon.ziminski@rutgers.edu

Corresponding author: Lili Razi, Rutgers University-Camden - 303 Cooper Street, Camden, NJ 08102-1519, USA, lili.razi@rutgers.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v14.i2.8201

Article History: Received 16/12/2021; Revised 27/05/2022; Accepted 14/06/2022; Published 27/07/2022

Abstract

The process of placemaking entails the use of physical and digital representations of place. An understudied element of these representations is how users’ agency and interaction with physical and digital placemaking contributes to sense of place within a community. This research uses A New View - Camden, New Jersey (ANV) public art initiative as a case study to analyze how digital representation of space contributes to sense of place among community members in an urban setting. ANV’s social media reach and coverage is triangulated with data from interviews and focus groups from the 2019-2021 project period. The digital interactions with public spaces evoked meaning to experiences and places in Camden, in turn influencing perceptions of the place and willingness of community members to engage. A New View’s digital representations not only created opportunities for wider outreach and longer lasting experiences of placemaking that contributed positively to community, but also contributed to understanding of placemaking in urban public spaces, particularly during the COVID-19 global pandemic.

Keywords

Physical Placemaking; Digital Placemaking; Public Art; Sense of Place; User Agency

Introduction

Placemaking, the beautification of underutilized urban space, is a relatively recent intervention that has emerged as a diverse and flexible tool for engaging communities across a variety of topics. A New View - Camden Public Art Challenge, created and driven by community residents and cross-organizational collaborations, used both digital and physical placemaking to achieve its project goals of increased civic engagement and awareness of illegal dumping. Specifically, A New View used placemaking through public art to generate community buy-in and enhance residents’ wellbeing, incorporating underutilized urban space into its placemaking efforts by cleaning up six vacant lots often used for illegal dumping across the city (Project for Public Spaces 2007; American Planning Association 2020, National Endowment for the Arts 2021). The public art installations created in these formerly vacant lots incorporated components of sustainability to spread awareness about illegal dumping in the city. In addition to art installations at these six sites, the involvement of digital placemaking through social media campaigns, online events, and contests during the A New View project period represented a new wave of placemaking within urban public art, which flourished during the challenges induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. With the inclusion of digital placemaking and further reliance on internet-based platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic, this case study explores how digital and physical placemaking contributed to meaning making and sense of place of place identity in Camden.

Theoretical Framework

Physical & Digital Placemaking

According to Project for Public Spaces (2007), placemaking is a collective process for public spaces that promotes physical, cultural, and social identities and maximizes shared value; it is a collaborative approach centered around art that uses art as a tool to bring stakeholders and community together (Frenette 2017). A core tenet of placemaking through art is to involve citizens in the process in order to make a place valuable to them, generating a sense of place (American Planning Association [APA] 2020). Socially, placemaking engenders community buy-in and aims to increase a sense of place and place attachment to form place identity (Coghlan et al. 2017). People’s attachment to a place and the identities they develop within a place is important for wellbeing and agency over their neighborhood(s) (Najafi & Shariff 2011; Jones & Evans 2012). People’s attachment to a place can be measured through language and photos that users take of a place, generating meaning of a piece of art specifically, or a place generally (Skinner 2018; Gonçalves 2019).

While placemaking often seeks to increase social well-being of community residents and increase civic engagement or pride, it often is associated with an economic intention, to increase economic viability. Economic-driven placemaking centers on place branding that aims for the economic, political and cultural development of urban areas. However, some believe neoliberal and globalized forces are likely to move placemaking towards marketing strategies and place branding (Montgomery 2016; Milano et al. 2019; Paquin 2019; Speake & Kennedy 2019). Place branding promotes city image and competitive advantage to outperform competitors and gain economic prosperity (Hankinson 2001; Kavaratzis 2004). In 2016, the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture stated that placemaking can also engender gentrification, racism, real estate speculation, all in the name of neighborhood revitalization. Efforts that involve placemaking must reject inauthentic or commodification of spaces, particularly in efforts that occur in urban spaces that have experienced decades of intentional disinvestment and inequities stemming from structural racism and economic inequality. To align with placemaking’s original intention of ‘co-created places,’ placemaking should reinforce positive user experiences among all residents and participants (Lefebvre 1968; Whyte 1980; Entrikin & Tepple 2006; Anholt 2010, p.10; Jacobs 2016). In turn, positive experiences through placemaking can encourage meaning making within a community and contribute to a shared sense of place within that community.

With the emergence of digital platforms, public spaces are now often experienced both digitally and physically. Digital placemaking through text and photos extends physical placemaking into the virtual world as community residents, public officials, artists, and other local leaders can reflect on space through social media (Mariani et al. 2016). In digital placemaking efforts, digital platforms enable users, project leads, partners, and community residents to share the experience of place with larger audiences and contribute to the meaning making and sense of place (van Dijck 2007; van Doorn 2011; Foth 2017). Contrary to other researchers who advocate for a top-down approach of experts and elite designing urban environments, Skinner discusses how residents (not only visitors) perceive the place they call home and should be co-creators of the place (2018, Speake & Kennedy 2019). Digital placemaking provides avenues through which residents can create content and deeply contribute to the progression of a public art project (Barretto 2013; Speake & Kennedy 2019). Indeed, prior research has shown how photos of a place are perceived differently by varying groups of people on Twitter, Instagram and on official websites (Skinner 2018).

Public Art, Placemaking, & Users’ Agency

Art is a medium to make meaning and activate civic action, and placemaking uses art to brand a place and engage residents. The more a project is in line with stories of a place’s history and local residents are reflected in the placemaking project, the better the art can promote a sense of belonging, ownership, and enhance a sense of place (Ellery & Ellery 2019; Madsen 2019). A New View - Camden’s emphasis on combating the civic issue of illegal dumping and changing perceptions of Camden provided opportunities for residents to directly engage with local artists, organizations, and project partners in efforts towards these goals, resulting in an urban public art initiative that both embraced the City’s diverse and vibrant history and supported local artists and community development efforts, ultimately generating user agency through the project’s physical and digital placemaking efforts and contributing to a sense of place. The A New View lead organizations were particularly attuned to the critiques and nuances of placemaking, and the importance of co-creation throughout A New View was heavily emphasized throughout the entire project as the project’s host city, Camden, has experienced intentional disinvestment and structural racism that has disproportionately affected its residents in comparison to other local communities. As such, lead partners were intentional about the co-creation (of the art, installation spaces, and community events) with residents throughout A New View.

Throughout A New View - Camden, users’ agency was activated through public art that intended to impact Camden’s identity in a positive way. This agency depends on the extent to which people value their living environment, engage in online platforms, and contribute to neighborhood engagement by attending events and contributing back to their community; it is strengthened through community input and active participation (Main & Sandoval 2015). The intentional and mutual engagement of Camden residents and organizations during A New View both through in person contributions to A New View art installations and events and online through various digital contests and social media efforts, impacted users’ meaning making of the place and strengthened user agency.

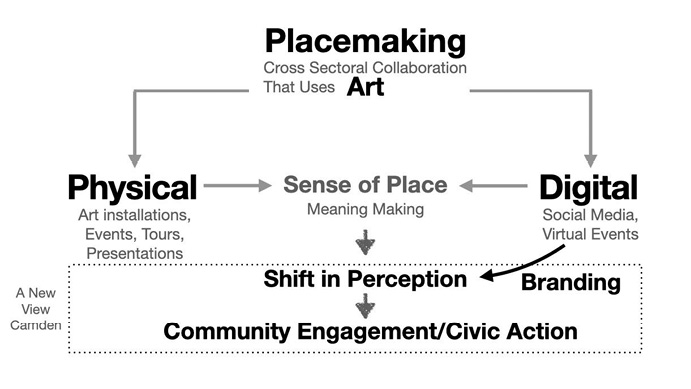

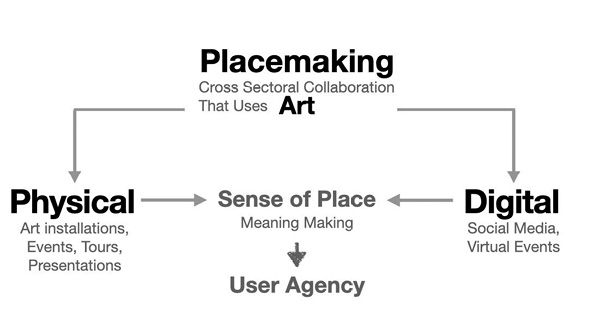

As illustrated in Figure 1, A New View - Camden engaged users along a variety of avenues in both digital and tactical placemaking towards contributions of meaning making and sense of place identity in Camden. This case study will outline how A New View placemaking occurred through intentional cross sectoral collaborations led by project partner lead organizations that included both physical placemaking, which included the art installations, events, tours, and presentations/conferences, and digital placemaking, which included virtual events, social media, and branding. The physical and digital placemaking activities engaged residents in meaning making that contributed to a sense of place towards A New View - Camden and the City of Camden. The ways that residents made meaning was through their user agency with digital and/or physical placemaking activities. The interaction of meaning making and user agency contributed to community engagement and shifts in perceptions of Camden, which ultimately could lead to additional longer term civic action.

Figure 1. Theoretical Framework

A New View - Camden Background

In 2018, the City of Camden, New Jersey won the Bloomberg Philanthropies Public Art Challenge, a program which supports major temporary public art projects in U.S. cities that address significant local issues, engage communities, catalyze economic development, and enhance the quality of life.

The Bloomberg Philanthropies Public Art Challenge invites mayors of U.S. cities with 30,000 residents or more to collaborate with artists to submit proposals to receive up to $1 million in funding for public art projects designed to address local challenges. In 2018, Bloomberg Philanthropies launched the second round of the Public Art Challenge, selecting five projects developed by Anchorage, Alaska; Camden, New Jersey; Coral Springs, Florida; Jackson, Mississippi; and Tulsa, Oklahoma. The five winning proposals highlighted issues such as climate change, illegal dumping and neighborhood blight, and gun violence and healing.

Camden received one million dollars for A New View, a public art project that transformed six vacant lots plagued by illegal dumping along major transit corridors into temporary dynamic community placemaking spaces, inspiring residents and attracting visitors. From 2019 - 2021, A New View included art installations, community-inspired events, and creative programming at several sites along Camden’s rail, road, and bike routes. The project was a collaboration led by the urban redevelopment nonprofit Camden Community Partnership (CCP) (formerly Cooper’s Ferry Partnership), Rutgers-Camden Center for the Arts, and the City of Camden. A New View encouraged residents to combat illegal dumping of household and industrial waste through education efforts and public-private partnerships. The city also aimed to strengthen the local artistic community and improve the quality of life for Camden City residents through the project.

This placemaking project is unique because the funder supported innovative temporary public art projects that enhanced the vibrancy of cities and focused on solutions for specific urban issues. A New View’s project goals were to: 1. change negative perceptions of the city by transforming a series of vacant lots, plagued by illegal dumping, into venues for public art; 2. increase civic pride and improve overall perception of the city through beautification efforts; and 3. demonstrate effective cross-sector partnerships and collaboration. To achieve these goals, A New View employed a tactical placemaking approach, which is an often temporary, small to medium scale or pilot, community development initiative that is typically cost effective and relies on community input to bring about changes in the area (Steuteville 2014; Delaware County Council 2017). This tactical placemaking approach involved both physical and digital elements of placemaking. A New View’s goals were to address illegal dumping and celebrate the vibrant arts scene in and history of the City of Camden, and project partners’ first step was to involve the people who contribute to that impact – which necessitated strengthening cross-collaboration among community members, nonprofit and for profit organizations, and government; providing opportunities for residents to engage with community and art; and supporting local artists.

Within the bounds of these goals, the short-term nature of the project coupled with the circumstances of the pandemic required some adaptations throughout the project. The project’s art installations were initially expected to run from April 2020 to October 2020. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States and around the world in March 2020 postponed all project work mid-project. Programming and evaluation resumed in full in September 2020, notably with all events, programming, and data collection occurring virtually. Resuming the project later in 2020 encouraged project partners to focus more on digital placemaking via social media. Therefore, community engagement was shifted towards the use of social media and online events. Digital placemaking through social media facilitated the branding of the sites and spread the name of the project work throughout Camden City and beyond. The public art installations were postponed from April to October 2020 to April 22, 2021 (opening day) to October 31, 2021. The postponement of the project and the two-year span contributed to the activation of users’ agency through both social media and physical spaces hosting the public art, which both provided in person and virtual opportunities to engage residents, learn about illegal dumping, and support local arts and culture initiatives.

Methodology

The case study framework for this analysis utilized multiple sources to unravel the impact of digital and physical placemaking on meaning making and users’ agency. During the course of the project, separate evaluation of A New View - Camden by the Senator Walter Rand Institute for Public Affairs (WRI) occurred. This program evaluation was required by the funder and coordinated through the main partner organization lead and the university research center. The aims of the evaluation were to contribute to the understanding of A New View’s impact. The mixed methods evaluation involved quantitative and qualitative data collection (through focus groups, interviews, and survey(s)) and analysis by the WRI. From Summer/Fall 2019 until April 2021, primary quantitative and qualitative data were collected prior to the opening of A New View installations (April 22, 2021), and were collected from April 22, 2021 to October 31, 2021 following the installations. The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily suspended the project in the middle of data collection from March 2020 to September 2020, data collection resumed in September 2020, and all university research restrictions were followed throughout the project. These methods were employed to explore the change over time throughout the project; as such, a pre and post design was employed.

This information was supplemented by various secondary data from community partners and project partners. The project partner lead, Camden Community Partnership, contracted with a separate marketing agency, En Route Marketing, to also collect a range of social media metrics related to A New View from Summer 2019 until the end of the project in late fall 2021. Metrics collected included number of A New View website page views/visitors, number of Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube followers, reach and impressions, and social media advertising totals.

All of the primary data collected through the program evaluation and secondary data from metrics from partner organizations were shared between the funder, lead partner organization, the evaluation partner, and other project partners as appropriate for various deliverables and requirements. As such, some of the focus group and interview primary data collected, analyzed, and reported on for the separate evaluation of A New View - Camden has been included here. Methodological triangulation, the use of several data collection methods and data points has been employed to increase the credibility and validity of the research findings (Denzin 2017; Cohen et al. 2002). The current study extends the triangulation from the evaluation of the [Senator Walter Rand Institute for Public Affairs (WRI)] by incorporating social media and event attendee data and metrics from the lead partner agency and marketing partner and primary interview and focus group data from the university evaluation partner. Also, in order to understand people’s feedback about the project, some posts from social media were randomly selected and represented as secondary data.

Findings

Project Partner and Resident Collaboration through Art

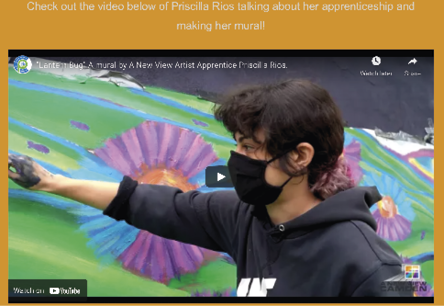

Community connection and building trust with community residents was paramount in this project. Data from project evaluation focus groups revealed the importance of this collaboration towards the urban public art placemaking initiative’s success. In some projects, ‘people come in and say one thing, and do another thing; you need to connect with the community and the top, and have people champion it themselves; tie in from the bottom up; it shows a level of respect to residents’, a community focus group participant shared. One of the main goals of A New View was to bring attention to the issue of illegal dumping, which costs the City approximately $4 million annually, and deep collaboration between project partners and residents facilitated engagement with public art and increased awareness of illegal dumping. Project partners and local artists repeatedly emphasized the importance of how they let thoughts and intentions for A New View be known to the community before decisions were made, and concertedly worked together in co-creation of A New View. One participant reflected on past community engagement experiences with Camden mural projects, where a call for community members to participate in any way they could (i.e., by bringing water to artists while working, etc.) led to people sweeping the sidewalk, and people wanting to get involved. Another shared, ‘The City was being cleaned and taken care of, and it grew through a community and art relationship’. Figures 2 and 3 show how residents served as integral partners in the project and engaged with community beautification efforts.

Figure 2. Instagram Post- Cleaning one of the sites with the community. Comment: Amazing.

Figure 3. Facebook Post- Comment: Thank you to the Dept of Public Works in Camden for all your help bringing public art and shout out to Erica and Juan for your help installing #invinciblecat

Throughout the project, the selected A New View artists were vessels between community residents and project partners. As one project partner shared, ‘signing the young artists name in the mural was meant to strengthen our relationship and have them [local artists] trust us [project partners]’. One artist shared:

‘In Camden when I moved in [year withheld], I wanted to learn the culture of the city. Their feelings, heartbeat, how they wanted to be presented. I did various workshops, spoke in church and advertised … I wanted to connect to the community before saying what the community needs. I definitely encourage you to learn about the city you want to serve’.

Throughout both the physical art installations and online events, contests, and webinars, residents and partner organizations together contributed to the creation of and elation around A New View. One respondent mentioned that ‘I love the incorporation of the book kiosk [at the public art installation sites], having a [local] artist to decorate [the box]’, others shared how a mural was painted spontaneously out of connections with local residents at the Touching the Earth public art site, and yet others commented on the written text on installation pieces by community members incorporated at the Phoenix Festival art site. One participant noted the possibilities for students to get involved in the art projects through volunteering, making videos, and storytelling.

There were dozens of unique opportunities for residents and partner organizations to connect and contribute to the creation of the art installations themselves, to conversations around illegal dumping, sustainability, and environmental racism, and to enjoy a local park or event in Camden affiliated with the A New View project. In A New View - Camden, building trust occurred by targeting an important civic issue in Camden, and welcoming, listening, and championing residents throughout the entire project process.

Figure 4. YouTube- One of the artist apprentices doing mural ‘Lantern Bug’

Physical Placemaking in A New View - Camden

The physical art installations and A New View events provided opportunities for users to gather, engage with public art and learn about illegal dumping, generate user agency over physical space across the city, and contribute to experiences of meaning and sense of place where events/installations occurred. This project was commissioned and completed during an extraordinary time of hardship and uncertainty, during which local economies crashed, daily life was disrupted, and the comforts of routines and social interactions were removed. By the time of the public art installations’ opening, vaccines against the coronavirus that caused the pandemic were beginning to be distributed among the general public, and subsequent project events and related programming were at times able to occur in person. Fortunately, the outdoor art installations provided spaces to gather in smaller groups outside and engage in socially distanced events and programming. The physical placemaking provided through A New View provided ways for users to directly engage with the City of Camden, public art, and the issue of illegal dumping. Through various events, speakers, and programs, users placed meaning to their experiences that ultimately reflected on the City of Camden.

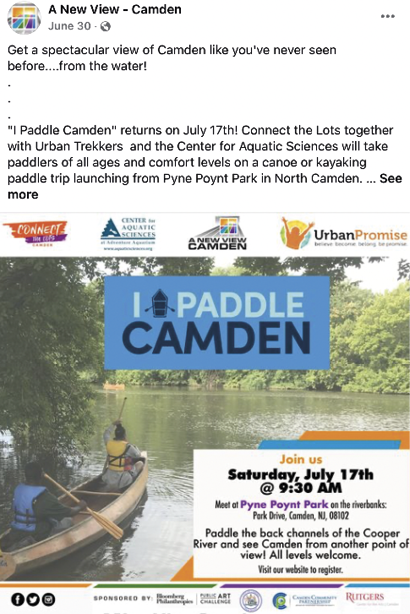

The public art installations remained open throughout the summer and fall of 2021, and often attracted passersby and local residents. A New View - Camden events included a mix of in-person and virtual events. 24 in-person events occurred from April 22, 2021 until October 31, 2021. These in person events occurred at the art installation sites and at local Camden parks and organizations. Events ranged from in-depth conversations about illegal dumping to family-fun activities; they often provided new experiences for residents (i.e., the iPaddling event Figure 8), chances to spend time with family and friends and engage with the art sites and learn about the impacts of illegal dumping and environmental racism. Other events included a photo contest, an essay contest about illegal dumping, a stoop decorating contest, and a poster contest. The physical placemaking engaged residents in different activities that induced meaning from the activity, driving creation of or a shift in place attachment and/or a sense of place related to the public art installation sites specifically or Camden generally. Together, these experiences and interactions between community members, artists, and project partners at in person events and at the art sites created reflective experiences that strengthened a sense of place and shaped meanings for the art installations and the City of Camden.

Figure 5. Figure 5 shows a post about a spoken word performer at one of A New View’s closing events, held at one of the art installation sites. Facebook Post- Comment: I had a good time. Everything was nicely done. Thank y’all so much.

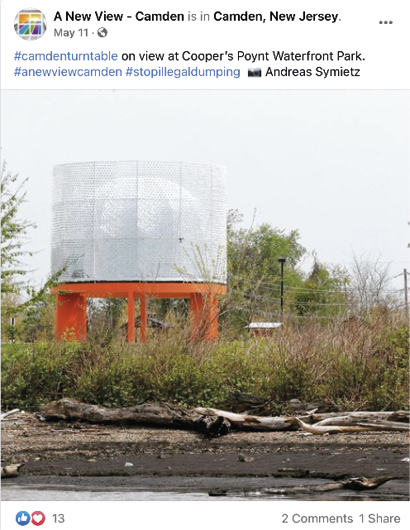

Digital Placemaking at A New View - Camden

Social media links people across time and space whilst creating and preserving meaning in those interactions. Due to A New View’s launch during COVID-19, the project had a strong social media presence and branding led by the main project partner, Camden Community Partnership. A New View had a website, Instagram, and Facebook page, and also advertised on local outlets and had much media coverage. The digital placemaking efforts were enhanced by targeted outreach and marketing of the project that increased awareness of the project and added to the project’s efforts of place branding around A New View and of Camden. Social media engagements with A New View reflected people’s experiences and meanings tied to those experiences as users were exposed to A New View online events, contests, and posts. These meanings, in turn, remain as reflections upon the specific places and spaces where those experiences occurred (Frith & Richter 2021).

As a result of digital branding, social media tracking throughout the art installation period revealed increases in engagement across platforms. Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter followers all greatly increased during the installation period, and impressions on these platforms also saw high increases. Followers essentially doubled on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter after the installations were unveiled in April 2021. Facebook reach increased 151% from 40,523 pre-installation to 101,878 post-installation, Facebook impressions increased 187% from 47,039 to 135,090, and the number of unique people who engaged with A New View Facebook posts increased 186% from 3,043 to 8,698 from the pre- to post- installation periods. The meaning that users’ experienced and subsequently defined was exhibited by their reaction to A New View - Camden’s social media posts, and included reactions expressed through both words and photos (Lynch 1964; Geertz 1973; van Dijck 2007; van Doorn 2011).

Beyond social media digital placemaking, other virtual placemaking efforts contributed to A New View’s project portfolio. Since in person activities were limited during much of the project’s duration, virtual events and engagement with social media allowed meaning making and users’ engagement to happen virtually, providing a space for users to insert feedback on the project and co-create the experience of A New View, ultimately reflecting on their sense of place towards Camden. Across the entire A New View project, almost 20 virtual events were held, engaging thousands of attendees via virtual means. Virtual events ranged from a Camden Artists Virtual Summit to Do-It-Yourself Art Projects, to discussions with local artists and the A New View Artist Curators. Essay contests, poster contents, and more started dialogue around illegal dumping and neighborhood beautification.

Recorded conversations like the WHYY-FM public radio Community Conversations helped people feel heard and raised awareness about illegal dumping and similar topics related to sustainability, environmental racism, and public funding. The digital platform became the avenue through which users experienced A New View or added their own component to the public art experience (van Dijck 2007). While users may not have been physically present in these spaces or at the art installations sites, a digital presence took on a ‘different kind’ of materiality in the form of digital text or images, which were supported by the ‘digitally material’ submissions of those who participated in the A New View photo and essay contests and other social media and digitally-led events (van Doorn 2011). The personal interactions with A New View’s social media posts and submissions to contests were often shared on the A New View social media platforms and connected users and their experiences with a larger audience, and with a Camden audience. Digital placemaking enabled residents to embed local culture, historical insight, and artistic ideas into the project and place. Digital placemaking can play a role in facilitating a dialogue across citizens, communities, government, businesses, civic groups and nonprofits, and in A New View digital placemaking enhanced widespread engagement and advertisement during the COVID-19 pandemic in ways that contributed to sense of place.

Physical + Digital Placemaking at A New View - Camden

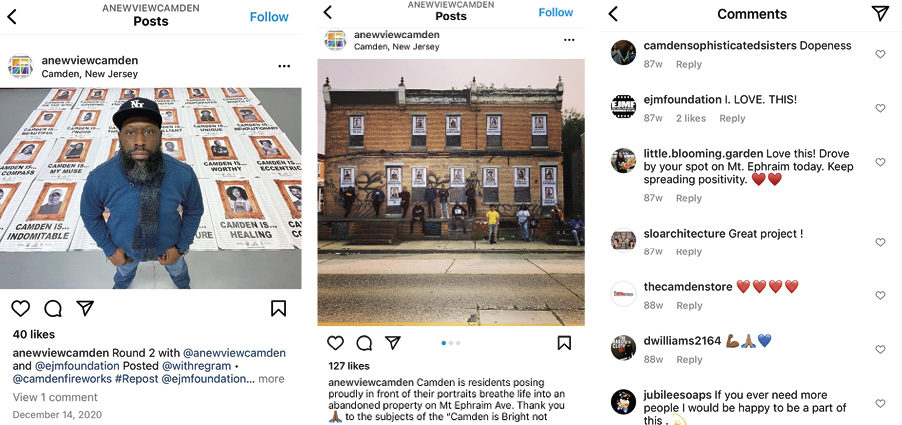

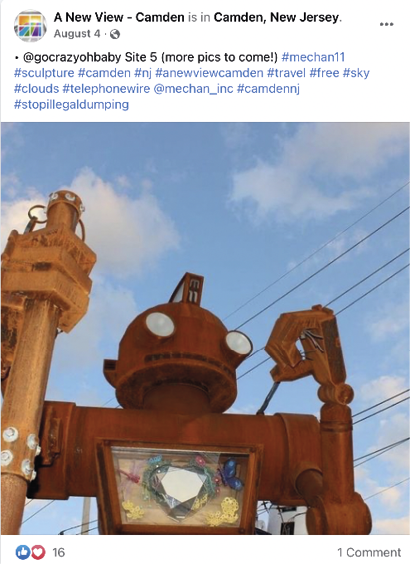

The combination of A New View branding from the project partner leads, engagement from cross sectoral collaboration, and the public’s experiences with the project created both a physical and digital presence for A New View. This combination supported the branding goals of project partners and infused the voices of residents highlighting what Camden means to them into the entire project. This hybrid placemaking model of A New View enabled people to engage with the project through both physical means and digital spaces. As noted by De Sousa e Silva and Frith, ‘when people start contributing to create the information that is attached to locations, they actively create the links among these locations...people are then transformed from readers into writers of urban spaces’ (2013, p. 45). A New View engaged residents from the project’s conception of the public issue (illegal dumping) to submit in the initial funding application through the end of the project as direct contributors and creators of programs and project events. Figures 6 - 10 exhibit social media comments and interactions with both virtual and physical A New View elements or events.

Figure 6. Facebook Post- Comment: This was so incredible! It gave my 6-year-old a whole new perspective on Recycling!!

>

Figure 7. Instagram Post- Interactions with A New View through social media comments.

Figure 8. Facebook Post- Comment: We had a great time! Thank you

Figure 9. Facebook Post- Comment: Love seeing this guy when I drive by!

Figure 10. Facebook Post- Comment: nice time and thank you for your dedication and volunteering.

A New View - Camden’s Contributions to Shifts in Perceptions and Community Engagement

Throughout the project, A New View partners and collaborators heightened usage of digital means of media and social media platforms to generate awareness about illegal dumping and the public art installations, connect individuals around the project, and provide opportunities for people to share their experiences of Camden and reflect. A New View’s toggle between digital and in person placemaking created an avenue through which users, Camden residents (or local nonresidents), could engage, share their thoughts, and voice their concerns and hopes for the project, urban public art, and Camden generally. The findings set out above chronicled various components of sense of place, collaboration, and digital and in person placemaking that contributed to A New View’s influence on the sense of place and community engagement.

Deeply related to sense of place are both negative and positive perceptions and people’s meaning making of Camden that were an undercurrent in discussing A New View’s presence within the city. Statements from interviews with project partners at both the outset and at the end of the project revealed the expectations, hopes, and challenges of the project. Many comments discussed differences in local vs. nonlocal perceptions of Camden. In reflection about external perceptions of the City of Camden, interviewees shared ‘Conception can have a strong impact’. and ‘A lot of people have never even visited Camden, but they talk about how bad Camden is, and that people still hold opinions from 10-20 years ago about what Camden is like’. Another focus group participant shared, ‘I work with members 18-26 and what I’ve heard them say about Camden is not always the best- there’s a lot of trash, it’s not pretty, there’s a lot of issues with drugs’.

A New View - Camden, through addressing rampant illegal dumping throughout the city, used public art to engage the community, while simultaneously encouraging both residents and visitors to ‘take a new view’ of the city. Local organizations shared in focus groups that perceptions start to change when people work together on an initiative in the city. Shared one person, ‘I definitely think there’s a sense of community in Camden, so as soon as they see that they are not alone in caring for Camden then it makes them want to stay in Camden and not leave’. Another participant shared how the A New View project has community involvement and gives residents a sense of pride. Another person noted that the project,

‘will bring unity to the communities because everybody from each neighborhood represents what part of the world [they are from]. So, they could live in North Camden and move to New York. They will always say, I am from North Camden because some of the representatives are from their heart. You know, people from Camden, they put a lot of pride on where they come from. It is right here, the unity’.

The meanings people attached to the project were shown through data from supplemental focus groups, with participants sharing thoughts such as, ‘Culture and arts have found a home in Camden’; ‘Forget what you thought you knew about Camden. Take a new view’; ‘Resilience in the city’; ‘Make neighborhoods know that the City of Camden is rising’; ‘The art in the city shows that this city is not a dump. We care about the city’. One participant noted the difference A New View will bring to the social and environmental attention of Camden, sharing, ‘It’s taking back your neighborhood. This is important to us. We need it. It’s a new year, new time, new view’.

Shifts in perception around Camden and what meaning both residents and visitors attach to Camden were also related to the civic action around illegal dumping. Commenting on the negative impact of illegal dumping, one focus group participant shared, ‘Some of the illegal dumping comes from outside the city but a lot of it is also about educating people and raising awareness’. Another person reflected that with increased awareness and condemning the act of dumping there is less possibility for outsiders to continue dumping in the city. Another interview participant shared that illegal dumping is twofold, as there is the physical dumping of garbage and metaphorical dumping on Camden residents. ‘Dumping on residents breeds a negative stigma, people say ‘I’m from Camden so I can’t, I won’t’. Other interviewees shared sentiments about how this meaning and narrative can be reframed to shift meaning and sense of place within Camden. One person commented, ‘art is a powerful medium to connect the project partner and community in contributing to the meaning of Camden; part of this narrative can be written through the arts, and people can champion what Camden means to them and generate a higher level of involvement’.

One interviewee commented on the positivity from people in the community about new businesses, small and large, and new generations in the city honing new talents. They shared, ‘driving through the city and seeing art installations in the streets as you drive by will raise attention. People in the city or visiting the city will see the art and notice the change’. These statements highlight the influence of placemaking efforts and contributions towards perception change and civic pride in the City of Camden.

Throughout A New View, the cross-sectoral collaboration and the use of art engaged residents and influenced perception of Camden, and this reimagining will continue. The A New View project and its placemaking was a short-term effort contributing to place identity at an embryonic stage of part of Camden’s revitalization (Hay 1998). Instead of immediate large-scale changes, the project contributed to the City’s transforming and reimagining sense of place. Many residents and local non-residents who engaged with the project reflected on the project’s appeal in Camden, expressed their pride in the project, and called for similar efforts to provide opportunities for local residents to showcase their talent and bring community members together. Shared one interviewee, ‘I still think it’s more powerful when you see the artist from the area. And you’re a little kid and your dad says he’s from this area. And you can do it too, Dad. That’s the sense of pride’.

Figure 11. Theoretical Framework leading to A New View Outcomes

As Figure 11 outlines, throughout A New View, the intentional cross-sectoral collaboration led by the main project partner involved local residents, organizations, artists, and city officials in creating and sharing dozens of physical and digital art pieces and project-related branding, events, webinars, and contests. Individuals that engaged with A New View, whether through an online art class, or through a biking event to all of the art installation sites, engaged with the project and induced various meanings from those experiences, which became attached to a sense of place of A New View and Camden. The ways users interacted with the various components of the project contributed to shifts in perception about the City of Camden and community engagement around illegal dumping and civic pride.

Discussion and Implications

Direct engagement between artists, project leaders, and residents fostered mutual relationships and contributions towards the goals of A New View - Camden. A New View revealed that digital placemaking was a medium to advertise public art, raise awareness, and engage users, operating in conjunction with the physical placemaking of the public art sites. Digital placemaking is a preliminary and parallel stage for community engagement along with physical placemaking. Cross organizational collaboration and community involvement throughout the placemaking process from beginning to the end were important to activate users’ agency as both physical and digital placemaking were manifested through sense of place and meaning making. Throughout A New View - Camden, meaning making and user agency encouraged community engagement and shifts in perceptions of Camden, which ultimately, in longer time frames, could lead to additional civic action. The project’s timeline during the COVID-19 pandemic also revealed the additive dynamism of digital placemaking to the project, supporting the inclusion of digital placemaking in future urban public art initiatives, and revealing the project’s and collaborators’ immense flexibility and creativity during a challenging and difficult public health crisis.

As part of the project’s efforts to change perceptions and increase civic engagement and pride, A New View provided time and resources to hone in on the pervasiveness of illegal dumping, raising awareness and increasing engagement around this issue. Throughout 2021, no illegal dumping occurred at any of the art sites throughout the installation period, and multiple public officials are now ‘adopting the issue’ on their platforms. A New View not only directly addressed illegal dumping during the physical placemaking but also spurred interest in replicating this type of initiative across the city for other civic topics.

The art installations provided spaces for community members, artists, and others to engage with one another, reflect, and experience public art. Partner organizations created new and more integrative relationships with other organizations in the city, reflecting on the positive experience of the A New View partnership, and interest in new partnerships forming in the future. Partnerships spurred by the project will continue following the project, as exhibited through a recent unveiling of ‘Camden’s Kings and Queens’ in Dudley Grange Park, a mural completed by one of A New View’s local artists (Trethan 2021). Two of the six installations remained after the project’s end – Invisible Cat (moved to Farnham Park across from Camden High School) and the Phoenix Festival on Federal Street. Parklets constructed by a local artist and murals painted during the installations by artist apprentices will also remain. According to another project participant, ‘We know from cases from around the world that if you provide opportunities and access for artists to move in, economic development follows. The creative spark, creative placemaking, which we now call it, of bringing artists that are innovators, curious, entrepreneurial — it’s a fever that infects everybody in the community, and it’s a tide that lifts all boats’ (April 23rd, 2021). The public art featured in A New View supported an invigoration of the community to sustain these types of physical placemaking efforts, while also creating permanent reflections of experiences during A New View from digital interactions.

The collaboration between residents, artists, and project partners strengthened the bridge between Camden’s existing art scene and new awareness to the City’s arts and culture spaces and resident artists. Users’ engagement on social media and experiences at events at the physical art spaces revealed mixed feelings - uncertainty, excitement, desire for more art in Camden, and more. Throughout the entire project, cultivating trust between residents and project partners and artists was a central focus of project leaders.

Maintaining and reimagining aspects of sense of place and meaning making remain complex processes, ones that will continue years past the project. Pre-existing and pre-conceived notions about Camden’s identity were examined, unveiled, and reimagined throughout the project and its associated events, branding, and interactions. These interactions show how continued collaboration and efforts in public art and arts and culture elevation in Camden will continue to contribute to a sense of place as residents remain engaged and continue their civic engagement. As seen through A New View, people’s engagement in both physical and digital events, art installations, and contests represented user agency in meaning making of those experiences, important experiences for residents’ wellbeing and agency over their neighborhood(s) (Najafi & Shariff 2011; Jones & Evans 2012). In Camden, the dedication to co-creation of physical and digital placemaking supported through users’ agency contributed to the reimagination of sense of place in Camden, a reimagination that will continue across other public art and collaborative initiatives in Camden in the coming years.

A New View’s physical and digital placemaking efforts promoted the diverse experiences of people within the City of Camden, supporting a sense of place of residents’ connection to Camden while working to shift outsider perceptions of the city. ‘The city is a discourse, and this discourse is truly a language’ (Barthes 1986) ‒ through fore fronting local artists and residents in designing the project, focusing on a uniquely local challenge of illegal dumping, and highlighting resident viewpoints and accomplishments throughout the project, A New View - Camden’s civic discourse was spoken through public art.

Conclusion

Both physical and digital placemaking play a role in reimagining urban spaces through art. Project partners often employ public art in placemaking projects to leverage community resources and connect people with their neighborhood. The public art in this project was used to inform people about illegal dumping and shift perceptions of Camden, NJ. In A New View, placemaking occurred through cross-sector collaborations in both physical placemaking, which included art installations, events, tours, and presentations/conferences, and digital placemaking, which included virtual events, social media, and branding. The physical and digital placemaking activities engaged residents in meaning making and contributed to a sense of place about A New View and about Camden. The ways that residents made meaning was through their user agency with digital and/or physical placemaking activities, events, and/or art pieces. The interactions with various project components sparked users to engage with the community, and also contributed to conversations around perception shifts of Camden and civic pride. The community engagement and action around illegal dumping could ultimately spur additional civic action on illegal dumping and related environmental and community development efforts. This project supported cross organizational collaboration and inspired continued celebration of the arts and investment in local artists. A New View was a short-term effort geared towards placemaking, and future research could focus on long term impacts of physical changes to the environment and sustained community engagement.

Acknowledgements

We immensely thank our colleagues Vedra Chandler and Meishka L. Mitchell from Camden Community Partnership who provided insight, expertise, and thought-partnership through the entire A New View – Camden project. Your collaboration was invaluable. We would also like to acknowledge BOP Consulting, En Route Marketing, and the Rutgers - Camden Center for the Arts for their collaboration on the project and data sharing, greatly improving the ability for this manuscript to be produced. We thank Dr. Stephen Danley for comments on early ideas of the manuscript. We acknowledge Camden Community Partnership and Bloomberg Philanthropies as funders for the Walter Rand Institute evaluation of A New View – Camden. We would like to thank the Walter Rand Institute for Public Affairs, A New View’s local evaluator, for supporting the evaluation work and case study submission. This manuscript’s submission was produced separately from the Walter Rand Institute’s A New View evaluation final report submitted to Camden Community Partnership and Bloomberg Philanthropies. We are deeply grateful for the opportunity to have engaged in this project and to collaborate with all those who led, participated, and contributed to A New View – Camden.

References

American Planning Association 2020, Creative placemaking, viewed 2021-09-20. https://www.planning.org/knowledgebase/creativeplacemaking/.

Anholt, S. 2010, ‘Definitions of place branding – Working towards a resolution’, Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, vol. 6, no. 1, pp.1-10. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2010.3

Barretto, M. 2013, ‘Aesthetics and tourism,’ Pasos: Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 79–81. https://doi.org/10.25145/j.pasos.2013.11.040

Barthes, R. 1986, ‘Semiology and the urban,’ In: Gottdiener, M. & Lagopoulos, A. P. (eds) The City and the Sign: An Introduction to Urban Semiotics, Columbia University Press, pp. 87-98. https://doi.org/10.7312/gott93206-005

Coghlan, A., Sparks, B., Liu, W., & Winlaw, M. 2017, ‘Reconnecting with place through events: Collaborating with precinct managers in the placemaking agenda’, International Journal of Event and Festival Management, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 66-83. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-06-2016-0042

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. 2002, Research Methods in Education, 5th edn. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203224342

Denzin, N. K. 2017, The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, Transaction Publishers, New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315134543

Delaware County Council 2007, Tactical Placemaking: Planner’s portfolio, issue 12. Planner’s Portfolio Series, Delaware County Planning Department. https://www.delcopa.gov/planning/pubs/Portfolio-12_TacticalPlacemaking.pdf

De Sousa e Silva, A. & Frith, J. 2013, ‘Re-narrating the city through the presentation of location’, In Farman, J. (ed.), The Mobile Story, Routledge, New York, pp. 34-49. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203080788

Ellery, P. J. & Ellery, J. 2019, ‘Strengthening community sense of place through placemaking’, Urban Planning, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 237-248. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i2.2004

Foth, M. 2017, ‘Some thoughts on digital placemaking’, In: Hespanhol, L., Haeusler, M. H., Tomitsch, M., & Tscherteu, G. (eds), Media Architecture Compendium: Digital Placemaking, Avedition, Stuttgart, pp. 203-205.

Frenette, A. 2017, ‘The rise of creative placemaking: Cross-sector collaboration as cultural policy in the United States’, The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, vol. 47, no. 5, pp. 333-345. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2017.1391727

Frith, J. & Richter, J. 2021, ‘Building participatory counternarratives: Pedagogical interventions through digital placemaking’, Convergence, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 696-710. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856521991956

Geertz, C. 1973, The Interpretation of Cultures. Basic Books, New York.

Gonçalves, K. 2019, ‘YO! or OY? - say what? Creative place-making through a metrolingual artifact in Dumbo, Brooklyn’, International Journal of Multilingualism, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 42-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2018.1500259

Hankinson, G. 2001, ‘Location branding: A study of the branding practices of 12 English cities’, Journal of Brand Management, vol. 9, no. 2, pp.127-142. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540060

Hay, R. 1998, ‘Sense of place in developmental context’, Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 5-29. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1997.0060

Jacobs, J. [1966]2016, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Penguin Random House, New York. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119084679.ch4

Jones, P. & Evans, J. 2012, ‘Rescue geography: Place making, affect and regeneration’, Urban Studies, vol. 49, no. 11, pp. 2315–2330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011428177

Kavaratzis, M. 2004, ‘From city marketing to city branding: Towards a theoretical framework for developing city brands’, Place Branding, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 58-73. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990005

Lefebvre, H. [1968]1996, ‘Right to the city’, Writings on Cities, Translated by Kofman, E. & Lebas, E. Blackwell, Malden, MA, pp. 147-159.

Lynch, K. 1964, The Image of the City, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Madsen, W. 2019, ‘Re-creating community spaces and practices: Perspectives from artists and funders of creative placemaking’, Journal of Applied Arts & Health, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 25-40. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah.10.1.25_1

Main, K. & Sandoval, G. F. 2015, ‘Placemaking in a translocal receiving community: The relevance of place to identity and agency’, Urban Studies, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 71-86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014522720

Mariani, M. M., Di Felice, M., & Mura, M. 2016, ‘Facebook as a destination marketing tool: Evidence from Italian regional destination management organizations’, Tourism Management, vol. 54, pp. 321-343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.12.008

Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Cheer, J. M. 2019, ‘Overtourism and degrowth: A social movements perspective’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, vol. 27, no. 12, pp. 1857-1875. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1650054

Montgomery, A. 2016, ‘Reappearance of the public: Placemaking, minoritization and resistance in Detroit’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 776-799. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12417

Najafi, M. & Shariff, M. K. B. M. 2011, ‘The concept of place and sense of place in architectural studies’, International Journal of Human and Social Sciences, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 187-193.

National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), 2021, Creative Placemaking, viewed 30 November 2021, https://www.arts.gov/impact/creative-placemaking.

Paquin, A. G. 2019, ‘Public data art’s potential for digital placemaking’, Tourism and Heritage Journal, vol. 1, pp. 32-48. https://doi.org/10.1344/THJ.2019.1.3

Project for Public Spaces (PPS) 2007, What is Placemaking?, viewed 2021-12-01, https://www.pps.org/article/what-is-placemaking.

Skinner, H. M. 2018, ‘Who really creates the place brand? Considering the role of user generated content in creating and communicating a place identity’, Communication and Society, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 9-24. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.31.4.9-24

Speake, J. & Kennedy, V. 2019. ‘Changing aesthetics and the affluent elite in urban tourism place making’, Tourism Geographies, pp. 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1674368

Steuteville, R. 2014, ‘Four types of placemaking’, Public Square: A CNU Journal. https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/four-types-placemaking

Trethan, P. 2021, ‘New mural shows Camden’s “Kings and Queens,” and aims to inspire other children’, Cherry Hill Courier Post, viewed 2021-09-17, https://www.courierpostonline.com/story/news/2021/11/16/photo-mural-highlights-empowers-camden-kings-and-queens-erik-james-montgomery-photography-art/8624091002/.

van Dijck, J. 2007, Mediated Memories in the Digital Age, Stanford University Press, Redwood City, CA. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804779517

van Doorn, N. 2011, ‘Digital spaces, material traces: How matter comes to matter in online performances of gender, sexuality and embodiment’, Media, Culture & Society, vol. 33 no. 4, pp. 531–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443711398692

Whyte, W. H. 1980, The Social Life of Small Urban Space, Conservation Foundation, Washington, DC.