Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 14, No. 2

2022

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

Urban Semantics through Law and Photography

Katya Assaf-Zakharov1,*, Tim Schnetgöke2

1 Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel, katya.assaf@mail.huji.ac.il

2 Photographer and Independent Scholar, tim.schnetgoeke@gmail.com

Corresponding author: Katya Assaf-Zakharov, The Hebrew University, Mt. Scopus, Jerusalem 9190501, Israel, katya.assaf@mail.huji.ac.il

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v14.i2.8028

Article History: Received 22/12/2021; Revised 10/06/2022; Accepted 10/06/2022; Published 27/07/2022

Abstract

The visual design of urban public spaces (hereinafter “cityscape”) has an important impact on city life – it can channel interpersonal communication into certain directions while excluding others; it can powerfully communicate notions of what is socially acceptable or important. Yet, while everyone may access urban public spaces, cityscapes are designed by a very limited social group. This paper focuses on the narratives embedded in the cityscapes. Analyzing legal conflicts arising around expressions that seek their way into the shared visual environment, as well as expressions whose presence in the cityscapes is disputed, we trace the dynamics of battles over urban narratives. The discussion of legal rules is complemented by photographs. Rather than illustrating the text, the photographs will relate to the discussed topics in their own way, enriching the discussion and broadening its perspective.

Keywords

Graffiti; Law and Photography; Urban Semantics; Freedom of Speech; The Right to be Heard; Public Spaces

Introduction

Every city has large public spaces that are accessible to everyone. City life is what happens in these spaces, this is where its spirit emerges and evolves. Being freely accessible to everyone, these spaces offer opportunities for spontaneous encounters between inhabitants. This communication, albeit mostly indirect, determines the very character of the city. Recognizing their central role in cities, courts identify urban public spaces as quintessential ‘public fora’ – e.g., Hague v. CIO (1939) 307 U.S. 496, at 515–16; U.S. v. Marcavage (3d Cir. 2010) 609 F.3d 264.

The visual design of urban public spaces (hereinafter ‘cityscape’) has an important impact on city life – it can channel interpersonal communication into certain directions while excluding others; it can powerfully communicate notions of what is important, what is acceptable, and what the right order of things in society is (Jacobs 1961; Marcus 1975). This paper is about the narratives embedded in the visual design of urban public spaces. Our goal is discovering these narratives and describing them, revealing the struggles behind them, outlining the dynamics of these struggles, and identifying their winners and losers.

We have chosen two different ways of listening to cityscapes and telling their stories. The first way focuses on analyzing legal conflicts revolving around expressive visual elements of urban public spaces. Legal decisions unveil the battles fought over cityscapes, allowing a glimpse into the different narratives that seek their way into our visual environment. The cases described in this paper are representative examples of larger judicial tendencies. Further decisions are summarized and discussed the longer version of the paper1.

The second way of listening and documenting cityscapes chosen here is photography. Rather than illustrating the text, the photographs will relate to the discussed topics in their own way, complementing the discussion with a visual tour through the narratives of urban public spaces. We have chosen this method to avoid redundancy and create a larger and richer picture of visual urban narratives. The photographs we use were all taken by Tim Schnetgöke during the past 5 years, documenting European cities.

Our study focuses on two locations – while the text refers to the US-American legal system, the photographs depict western European cityscapes. In legal literature, the US legal system is often contrasted to its European counterparts. Yet, as the combination of text and photographs will reveal, European and American regulations of urban semiotics bear important similarities. Splitting the focus of textual and visual discussion thus points out the general, rather than location-related, nature of our study.

This paper proceeds as follows. Part I describes legal conflicts over the right to place expressive elements into the cityscapes and remove them therefrom. Part II focuses on unofficial cityscapes created by graffiti. Part III criticizes the current state of affairs, in which official urban narratives occupy a hegemonic position, controlling our cityscapes and, consequently, largely dominating the dynamics of city life itself. It will conclude the discussion with a vision of an alternative legal order, one in which urban narratives emerge in a free and uncontrolled social discourse.

Official Cityscapes Constructed

What are cityscapes made of? They are made of various visible surfaces and other elements, which surround city inhabitants in public spaces. These are external walls of buildings, sidewalks, parks, plazas, billboards, art placed in various urban locations, trains, buses, etc. The legal system assigns and regulates rights to design cityscapes. For instance, it determines whether a sculpture in a public plaza is the artist’s protected speech or government speech or if a religious group is entitled to place a monument in a public park. Studying legal rules assigning rights to shape elements of the cityscapes, we can identify groups that enjoy the right to display their messages in the cityscapes and those whose narratives remain invisible.

Our analysis here will focus on public property. Many significant urban locations usually belong to the city or the state, and thus constitute public property. These include freely accessible public spaces – such as parks, plazas, and sidewalks – as well as central buildings of the city, such as the City Halls and other municipal or state buildings. Legal practice has classified these spaces as different kinds of ‘fora’ – public form, limited public form, and nonpublic forum (A.L.R.6th 70, 513 [2011] 2021). These categories differ in the scope of leeway the government has while imposing restrictions on free speech.

Sidewalks, parks, streets and plazas are all recognized as ‘traditional’ or ‘quintessential’ public fora, entitled to the highest degree of First Amendment protection (Cannon v. City and County of Denver (10th Cir. 1993) 998 F.2d 867; Pindak v. Dart (N.D. Ill. 2015) 125 F. Supp. 3d 720). Yet, this status has practical significance only in the field of temporal speech, such as demonstrations, rallies, and the distribution of handbills (A.L.R.6th 70, 513 [2011] 2021). Restrictions on such activities must withstand strict judicial scrutiny: they must be content-neutral, narrowly tailored to serve a significant governmental interest, and leave open ample alternative channels for communication (e.g., Clark v. Community for Creative Non–Violence (1984); 468 U.S. 288 Ward v. Rock against Racism (1989) 491 U.S. 781). Important as they may be, these types of speech do not leave any lasting marks on the cityscapes and, consequently, do not have the same effect as permanently present expressive elements, such as monuments, murals, or sculptures. These latter elements are designed by governmental bodies. Courts usually categorize them as ‘government speech’ and ‘non-public forum’. The ‘government speech doctrine’ exempts this type of speech from judicial scrutiny. This allows public authorities to exercise significant control over expressions displayed on public property, placing messages it wishes to convey and excluding dissonant speech (Muir v. Ala. Educ. Television Comm’n (5th Cir.1982) 688 F.2d 1033; Downs v. Los Angeles Unified Sch. Dist. (9th Cir.2000).

In what follows, we will describe legal conflicts around expressive elements placed – or sought to be placed – on public property. The discussion will be divided into (a) political and ideological and (b) artistic speech.

Political and Ideological Speech

From time to time, various social and political groups attempt to challenge symbolic messages placed on central urban sites. Each of these decisions allows a glimpse into the battleground over symbolic presence in urban public spaces.

Several decisions have dealt with monuments in public parks. Thus, in 1992, Chicago’s Puerto Rican community applied for permission to erect a statue of Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos, a political leader, who advocated Puerto Rican independence. The community aspired to place the statue in Humboldt Park, where several other communities – such as the German and the Norwegian ones – had already erected statues of their notable compatriots (Fernandes 2016). The city rejected the statue, explaining that it wishes to avoid the controversy of Puerto Rican independence, and the Puerto Rican community sued (Comite Pro-Celebracion v. Claypool (N.D. Ill. 1994) 863 F. Supp. 682). In a preliminary decision, the court found that the city’s rejection might run contrary to the First Amendment and refused to dismiss the community’s suit (ibid., pp. 690-691). However, the community discontinued the legal battle, probably due to the complexity and costs of such proceedings. Instead, it purchased a vacant lot inside a Puerto Rican neighborhood, and placed the monument there (Fernandes 2016).

In another case, decided in 2009, the Supreme Court dealt with a religious organization that asked the city of Pleasant Grove to place a monument containing the Seven Aphorisms of Summum in a public park, where a donated Ten Commandments monument already stood Pleasant Grove City, Utah v. Summum (2009)1 555 U.S. 460). Declining this request, the city explained that it limited park monuments to those either directly related to the city’s history or donated by groups with longstanding community ties. The Summums claimed that the city violated their rights to free speech and equal treatment of religious views. Rejecting these arguments, the court held that permanent monuments in public parks constitute government speech (ibid., p. 470). The government is entitled to choose the views that it wants to express inter alia by choosing private donations that would best deliver the desired messages. Emphasizing the important role city parks play in defining the identity of a city, the court upheld the right of the government to select monuments that appropriately convey its views (ibid., pp. 480-481).

In both cases, minority groups holding dissenting views sought representation in highly symbolic urban spaces. Such representation could lend a feeling of belonging and social acceptance. It could give both groups a chance to mark their presence and share their views with a larger urban community. Yet, both in Chicago and in Pleasant Grove, local authorities decided to deny the desired representation. Symbolic exclusion of this kind is associated with feelings of rejection, alienation, and dis-belonging among the respective communities (Buckley 2018): see Figure 1.

Figure 1. A monument in Berlin commemorating ‘comfort women’, Korean victims of Japanese sexual violence during World War II. Municipal authorities decided to remove the memorial in response to pressure from the Japanese government. However, local activists resisted the removal, and it was temporarily halted. Berlin 2020.

The same is true for groups holding non-conformist ideological views. Thus, in 2001, the Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit dealt with a Christmas display erected by the City and County of Denver on the steps leading up to the City Hall. The display included a crèche, Christmas trees, Santa Claus and similar images (Wells v. City & County of Denver (10th Cir. 2001) 257 F.3d 1132). The Freedom From Religion Foundation (FFRF) requested permission to place its own sign next to this display, reading ‘The Winter Solstice. May reason prevail. There are no gods, no devils, no angels, no heaven or hell. There is only our natural world. […] The city of Denver should not promote religion’. Having received no response to its request, FFRF placed the Winter Solstice sign next to the official display. The city removed it, and FFRF sought legal remedy.

Concluding that the holiday display was government speech, the court held that the City of Denver was entitled to present its message without having to incorporate the message of others (ibid., p. 1143)2. It declined FFRF’s argument that the message thanking the sponsors was corporate speech, rather than government speech. While acknowledging the benefits the sponsors may receive from the message, the court nevertheless held that this was a city’s message: ‘Indeed, any benefit that accrues to the sponsors ultimately serves the City's interests by providing current and putative sponsors with an incentive to contribute to the [City]’ (ibid., p. 1142).

In another case, the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit addressed the decision of the State of Maine Governor to remove a mural depicting Maine's labor history (Newton v. LePage (1st Cir. 2012) 849 F. Supp. 2d 82). The decision was taken in response to opposition from the business community, as well as to anonymous complaints claiming that the mural constituted propaganda of the Union Movement. A group of residents argued that the decision to remove the mural was based on the Governor’s disagreement with its ‘pro-Union” and ‘anti-business’ views, and hence, amounted to unconstitutional content-based speech regulation. Applying the government speech doctrine, the court dismissed this argument, exempted the Governor’s decision from free speech scrutiny and recognized his authority to decide what the State of Maine says or does not say about itself (ibid., pp. 129-130).

These cases allow a first glimpse into ideological battles over narratives shaping the cityscapes. Using their power to design public spaces, urban authorities white out expressions that do not conform to the mainstream, such as those questioning Christmas or advocating a union-led labor market. These decisions point out another significant ideological component of the cityscapes: their tendency to side with capitalist ideology. Thus, while a message thanking commercial sponsors may occupy a central site in the city, a pro-union message cannot. Figures 2-4 illustrate anti-capitalist narratives resorting to cityscapes’ margins as unofficial contributions.

Figure 2. Gonzoe, ‘Capitalism Kills,’ Berlin 2020.

Figure 3. River side luxury condos, and a message of hate directed at the rich. Berlin 2020.

Figure 4. Fight the Power / Do What Moves You, Berlin 2019.

Artistic Speech

Most artistic works displayed in urban public spaces are sponsored by the state. Acting as a significant patron of the arts, the state may commission certain artists to create works for urban spaces or announce competitions whose winners will get to display their works in such spaces. Legal conflicts in this context may arise when local authorities wish to remove a previously chosen work or decline a piece of art for apparently ideological reasons. A look at these cases will provide a sense of what kind of art local authorities favor while shaping official cityscapes.

In 1979, the US General Services Administration (GSA) selected Richard Serra, an internationally renowned American artist, to create a sculpture for the Federal Plaza in lower Manhattan, New York (Serra v. U.S. Gen. Servs. Admin. (2d Cir. 1988) 847 F.2d 1045). Soon after its emergence in 1981, Serra’s sculpture ‘Tilted Arc’ became the object of intense public debates. GSA received hundreds of letters from community residents and federal employees complaining about the sculpture's obstruction of Federal Plaza and its unappealing aesthetic qualities. Voices against removal of the work tended to be artists and art critics who pointed to the work's significance in 20th Century sculpture (ibid., p. 1047). To conciliate the opponents of ‘Tilted Arc,’ GSA decided to remove it from the Federal Plaza. Since the work was created specifically for this site and had no meaning outside its context, its removal equaled destruction (ibid.). Serra sued, claiming that GSA’s decision violated his free speech rights.

Dismissing Serra’s arguments, the court maintained that ‘Tilted Arc’ was entirely owned by the government and displayed on governmental property. Hence, the sculpture constituted government speech, and not Serra’s private speech. Accordingly, Serra was not entitled to free speech protection (ibid., pp. 1049-1050). The court further noted that even if Serra were protected by the First Amendment, the restriction on his free speech was permissible and content-neutral:

[T]he decision to remove ‘Tilted Arc’ was not impermissibly content-based. […] At the very most, Serra suggests that [GSA] thought that ‘Tilted Arc’ was ugly. That is surely an assessment of the work's content, but […] there is no assertion of facts to indicate that GSA officials understood the sculpture to be expressing any particular idea, much less that they sought to remove the sculpture to restrict such expression or convey their own disapproval of the sculptor's message. Indeed, Serra is unable to identify any particular message conveyed by ‘Tilted Arc’ that he believes may have led to its removal. […] To the extent that GSA's decision may have been motivated by the sculpture's lack of aesthetic appeal, the decision was entirely permissible (ibid., pp. 1050-1051).

Much can be learnt from this decision. First, the government decided to commission a work of a famous artist to occupy a most central site in the city. Although we can safely assume that this decision reflects the general strategy in this field, it hardly makes a good policy. Art, by its very nature, is a very dynamic field, with vague and constantly changing standards. Fame and recognition often come after years, if not an entire life, of namelessness and rejection. Art institutions enjoy significant hegemony over the question of what art is and which works should be valued. This hegemony results in a very small group of people doing art being singled out as “real artists’ to the exclusion of all the rest (Assaf-Zakharov & Schnetgöke 2021). Commissioning famous artists to adorn cityscapes with their works reinforces this hegemony and precludes a real artistic discourse – one that would allow experiment and innovation – in our shared public spaces.

Moreover, as the consequent events revealed, the idea behind choosing a renowned artist was, inter alia, to have a widely accepted and non-controversial piece of art. This policy is questionable. In the field of art, social acceptance can hardly be regarded as a reliable proxy of quality. Popular taste is, to a large extent, the result of what people are used to seeing. Thus, although impressionism seemed ugly to most of its contemporaries, now this painting style is predominantly perceived as beautiful. Holding that the decision to remove a piece of art because of ‘lack of aesthetic appeal’ was content-neutral, the court turned a blind eye to the dynamics of visual arts. To be sure, Serra was ‘unable to identify any particular message conveyed by ‘Tilted Arc’’. But the aesthetic message he was trying to voice is no less expressive because he could not put it into words.

The government’s aspiration to display only socially accepted aesthetics in urban spaces takes away one of the most essential components of art – it’s ability to question the accepted standards, to dare, to revolutionize. This policy turns public art into mere repetitions of the same well-known styles, depriving city inhabitants of everyday encounters with genuine artistic creativity (See Figures 5-6).

Figures 5 and 6. Examples of official public art adorning the streets of Berlin.

A year after the Serra decision, in 1990, the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA) was enacted as an amendment to the Copyright Act, to provide ‘moral rights’ to artists. VARA secures the inalienable right to preserve an artistic work against destruction, but only if the work is of ‘recognized stature’ (17 U.S.C. § 106A). This provision could theoretically protect an artist like Serra, whose work is about to be removed from a cityscape because of controversy. Yet, courts have interpreted VARA in a way that excludes such a possibility. First, a consistent line of jurisprudence interpreted the term ‘recognized stature’ as a broad recognition by artistic community (Carter v. Helmsley–Spear, Inc. (S.D.N.Y.1994) 861 F.Supp. 303; Martin v. City of Indianapolis (7th Cir. 1999) 192 F.3d 608), supported by extensive evidence of art experts Holbrook v. City of Pittsburgh (W.D. Pa. 2019) 2019 WL 4409694). In this sense, VARA is another brick in the wall protecting the hegemony of established art; it can offer little help to controversial artists challenging the existing aesthetic standards and social norms. Second, removing an artwork from its location is not in itself considered a damage under VARA (Baird v. Town of Normal (C.D. Ill. 2020) WL 234622). Moreover, courts have found that VARA does not protect site-specific works, whose integrity is compromised when they are removed from their location (Phillips v. Pembroke Real Estate, Inc. (1st Cir.2006) 459 F.3d 128; Urbain Pottier v. Hotel Plaza Las Delicias, Inc. (D.P.R. 2019) 379 F. Supp. 3d 130). Jointly, these judicial rules make it plainly impossible to use VARA to prevent the disappearance of a controversial artistic work from a cityscape.

Another way of disadvantaging controversial art is by denying funding. Thus, in 1989, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) – the major American sponsor of the arts – drew much controversy for having funded Andres Serrano's ‘Piss Christ’ and Robert Mapplethorpe's ‘The Perfect Moment’. ‘Piss Christ’ was a photograph of a small plastic crucifix submerged in a small glass tank of the artist's urine, and ‘The Perfect Moment’ was an exhibition of photographs depicting gay BDSM motifs. Both works sparked public and political outcry, the former being accused of blasphemy, the latter of obscenity, and both being denounced as ‘morally reprehensible trash’3. Reacting to this controversy, Congress amended the law governing NEA’s activity to direct NEA to ‘tak[e] into consideration general standards of decency and respect for the diverse beliefs and values of the American public’ in its judgement procedures (20 U.S. § 954(d)(1)).

Following this amendment, four artists whose works had been approved by NEA before the amendment, were ultimately denied funding because these works involved controversial motifs and non-mainstream sexuality. The artists filed suit, alleging that NEA had violated their First Amendment rights by rejecting the applications on political grounds (Nat'l Endowment for the Arts v. Finley (1998) 524 U.S. 569). Dismissing this claim, the Supreme Court held that while acting as a patron of the arts, Congress has wide latitude to set spending priorities, which does not mean that it engages in a content-based speech regulation (ibid. p. 571). In a dissenting opinion, Justice Souter commented:

Boiled down to its practical essence, the limitation [set forth by the new amendment] obviously means that art that disrespects the ideology, opinions, or convictions of a significant segment of the American public is to be disfavored, whereas art that reinforces those values is not. After all, the whole point of the proviso was to make sure that works like Serrano's ostensibly blasphemous portrayal of Jesus would not be funded, […] while a reverent treatment, conventionally respectful of Christian sensibilities, would not run afoul of the law. Nothing could be more viewpoint based than that. […] The Court does not strike down the proviso, however. Instead, it preserves the irony of a statutory mandate to deny recognition to virtually any expression capable of causing offense in any quarter as the most recent manifestation of a scheme enacted to ‘create and sustain ... a climate encouraging freedom of thought, imagination, and inquiry’ (ibid.).

The story of NEA’s controversial funding policy being restricted by the law is another battle over public art won by the mainstream narratives and lost by alternative voices – this time by those questioning Christianity and mainstream sexuality. Making ‘the observance of standards of decency and respect for the values of the American public’ a criterion for receiving public funding subordinates public art to dominant social narratives, stripping it of its subversive and avant-garde roles. Although it is possible to create art without public funding, NEA’s support is often a major factor in an artist’s career in the US. Hence, as the majority opinion itself noted, ‘[a]s a practical matter, artists may conform their speech to what they believe to be the NEA decision-making criteria in order to acquire funding’ (ibid., p. 589).

Two further decisions dealt with art in urban public spaces, and revolved around works created by the animal rights organization ‘People for Ethical Treatment of Animals’ (PETA). The first case focused on a public art event known as CowParade that took place in New York City in 2000 as part of the millennial celebrations. Municipal authorities co-hosted this event with private entities (People for Ethical Treatment of Animals v. Giuliani (S.D.N.Y. 2000) 105 F. Supp. 2d 294). It consisted of approximately 500 life-size fiberglass sculptures of cows, which have been artistically designed and displayed in various highly visible locations throughout the city. CowParade organizers invited individuals, groups, and corporations to submit their designs of cows to the event’s committee.

PETA proposed two cow designs. The first consisted of a cow covered with imitation leather products such as belts and jackets, and bearing the words ‘buy fake for the COW'S sake.’ The committee approved it. The second design divided the cow into sections in a manner of a butcher shop chart, with each section containing a statement concerning the health and ethical problems associated with the killing of cows, such as ‘Cattle are castrated and dehorned without anesthesia’; and ‘Meat Eaters die from heart disease 3 times more frequently than vegetarians’. This design was rejected as inappropriate, overtly and aggressively political, too graphic and violent for a display where the public at large would encounter it without having sought it out. It did not comport with the spirit of festive, whimsical and decorous entertainment envisioned for the exhibit (ibid., p. 301).

PETA filed a legal suit, arguing that the City had no authority to transform traditional public property, like parks or sidewalks, for purposes of limited expressive activities without allowing unrestricted access to anyone wishing to participate on an equal basis (ibid., p. 311). Declining this argument, the court held that the forum from which PETA's cow design was excluded was not a particular corner of a sidewalk or park, but only the CowParade:

PETA ordinarily would not be entitled to place a permanent structure, even an artwork, on a public sidewalk or park. […] [T]he denial of access to PETA to sponsor a cow in the exhibit does not in any way implicate or interfere with PETA's ability […] to carry out its mission, giving free expression to its entire message on any other public street, park or sidewalk space in the City. […] [A]mple alternatives exist for PETA to convey its full message to the same or a larger audience (ibid., pp. 317-18).

Less than two years after the CowParade, PETA decided to participate again in an outdoor art exhibit, this time in Washington D.C. (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Inc. v. Gittens (D.C. Cir. 2005) 414 F.3d 23). Similarly to CowParade, the District's Commission on the Arts and Humanities (‘Commission’) launched an event called ‘Party Animals,’ consisting of large designed sculptures of donkeys and elephants installed at prominent city locations. PETA submitted two designs, one of a happy circus elephant, and the other of a sad, shackled circus elephant with a trainer poking a sharp stick at him. The Commission accepted the happy elephant, but rejected the sad one, explaining that ‘Party Animals’ project was designed to be festive and whimsical, reach a broad-based general audience and foster an atmosphere of enjoyment and amusement. PETA's rejected design did not complement these goals, and was contrary to the event’s expressive, economic, aesthetic, and civic purpose.

PETA went to a court, and lost its case again. Applying a slightly different analysis than in the CowParade case, the judge found that ‘Party Animals’ constituted government speech, and was exempt from free speech scrutiny (ibid., p. 30-31).

The two cases can teach us a lot about the vision of public authorities as to the proper role of art in urban spaces. Two important and large-scale artistic events were both organized in cooperation with commercial sponsors and intended to bring financial benefits to the cities. Both envisioned a festive and amusing entertainment. PETA’s cow promoting imitation leather products and its happy elephant could easily fit in, but not its designs referring to animal abuse. Indeed, animal abuse and torture is a highly controversial issue. PETA’s messages are antithetical to many people’s lifestyle (Figures 7-8).

Figures 7 and 8. Examples of narratives similar to PETA’s in form of non-commissioned contributions.

We disagree with the argument in the CowParade case, according to which the rejection of PETA’s cow design does not interfere in any way with its ability to carry out its mission in public streets, parks or sidewalks. As the court itself noted, the right to free speech is not accompanied by a license to place a statue on public open spaces or to readorn public or private property. It is only accompanied by a right to temporary expressions, such as distribution of handbills or demonstrations – whereas these activities are relatively easy to ignore. Public authorities enjoy the right to place large and eye-catching designs in key locations of this city, and thus control the major means of expression in the cityscapes. They use this control to design cityscapes conveying a cheerful and consumption-promoting atmosphere, while at the same time suppressing critical voices. Because of the power of cityscapes over our perception of reality and ourselves (Jacobs 1961; Marcus 1975), this policy significantly contributes to the more general tendency of capitalist societies to educate people towards passive consumption instead of engaged citizenship (Barber 2007). Thus, the ‘expressive, economic, aesthetic, and civic purpose’ of large public events is obviously not to encourage an open democratic debate on socially important issues, but ‘to bring financial benefits to the city and its businesses’ (People for Ethical Treatment of Animals v. Giuliani (S.D.N.Y. 2000) 105 F. Supp. 2d 294, 299).

All in all, while choosing art for the cityscapes, public authorities do their best to avoid any conflict or controversy, turning our shared public spaces into sites of repetitive mainstream messages and driving away aesthetic innovation and ideological dissent. In many cases, the courts hold that the speaker behind an artistic work in public space is the government rather than the artist. These holdings largely reflect the hegemonic narratives voiced by government-sponsored public art – it communicates the narrative of social consensus promoted by public authorities rather than voicing multiple narratives of their creators.

Official Cityscapes Deconstructed – Graffiti and the Battle over Urban Narratives

The hegemony of official cityscapes is confronted by relentless resistance. Graffiti – the practice of non-commissioned painting on various urban surfaces, including walls, bridges and trains - along with other expressive interventions interrupt and deconstruct the integrity of official cityscapes, persistently claiming their own right to the city and offering an alternative, unofficial vision of the shared cityscapes (Figures 9-10).

Figure 9. Unknown Artist. Paris, 2017.

Figure 10. Clet Abraham, Naples 2019.

The legal system suppresses such attempts, fighting graffiti with remarkable vigor. Thus, legislators toughen the ‘war on graffiti,’ increasing existing criminal penalties and introducing new ones – i.e., suspension of a driving license – extending police search powers, and restricting various graffiti-related activities, such the selling of paint (Docuyanan 2000; Young 2012). Similarly, judges frequently express utmost dismay with ‘graffiti vandalism,’ sometimes issuing especially high penalties in a specific case to deter others from painting graffiti (Young 2012). Consider, for instance, the following passage:

Graffiti vandalism—the outrageous scarring of real property both public and private with unintelligible markings made by irresponsible persons—plagues […] cities in the United States and Europe (Sherwin-Williams Co. v. City & Cty. of San Francisco (N.D. Cal. 1994) 857 F. Supp. 1355).

In most cases, the judicial analysis of graffiti does not refer to its expressive content, choosing instead the narrative of numbers: how many graffiti pieces were painted, what their size was, and how much it will cost to remove them (e.g., ibid.; People v. Santori (2015) 243 Cal. App. 4th 122, 196 Cal. Rptr. 3d 500). Reading the description of the factual background of these decisions leaves the impression that the content of the writings or paintings was intentionally left outside the legal discussion, to make it clear that the case at stake deals with dirt, containment, and has nothing to do with expressive activity (ibid.). Here is a typical judicial description of graffiti: ‘[T]he graffiti was between 12 and 18 feet in length, necessitating the cleaning of a 300 square foot area of wall. […] The invoice listed a price of $475 for each location, for a total of $950’ (People v. Quezada (Cal. Ct. App. 2016) WL 2627042, p. 1).

The content of graffiti is sometimes mentioned in order to attribute multiple pieces to the same person in absence of direct evidence (e.g., State v. Foxhoven (2007) 132 Wash. App. 1053). In such cases, courts sometimes even go beyond the mere question of whether the same letters were painted, comparing the expressive content of the different messages and learning from experts’ testimonies whether different pieces were created with the same artistic ability (People v. Lopez (Cal. Ct. App. 2014) 2014 WL 68267). Additional cases where courts refer to graffiti’s expressive content are instances, in which this content is especially objectionable in the court’s eyes – such as profane, anti-police, or anti-establishment (e.g., In re T.P. (Cal. Ct. App. Jan. 18, 2007) 2007 WL 118346; People v. Aguilar (Ct. App. 2016) 209 Cal. Rptr. 3d 313). In other words, in most cases, graffiti is pictured as non-expressive activity or activity expressing objectionable messages.

Interestingly, while discussing other issues and referring to graffiti only incidentally, courts sometimes do recognize its expressive value. For instance, in one case, wishing to illustrate the idea that the legislator has the power to ban a whole channel of communication, the court observed:

[Graffiti] is an inexpensive means of communicating political, commercial, and frivolous messages to large numbers of people; some creators of graffiti have no effective alternative means of publicly expressing themselves (Metromedia, Inc. v. City of San Diego (1981) 453 U.S. 490, 550).

Similarly, while considering the constitutionality of means of combating graffiti – such as restricting the selling of paint – courts do make an effort to understand the expressive content of graffiti, in order to assess the effectiveness of such measures. Consider, for instance, the following judicial statement:

[W]e believe that an accurate description must provide that ‘graffiti’ is in fact intended as an expression of ideas, information and culture, as opposed to a product of carelessness and neglect (Nat'l Paint & Coatings Ass'n v. City of Chicago (N.D. Ill. 1993) 835 F. Supp. 421, 425).

Moreover, when graffiti plays an incidental role, courts sometimes recognize that it does not actually cause serious damage. For instance, in one case, where the defendant asked to apply a certain defense available in graffiti crimes to another criminal context, the court refused doing so, noting:

While vandalism and graffiti are frequently unsightly, the damage resulting from a vandalism or graffiti offense often does not even prevent the property owner from continuing to use the damaged property. […] [V]andalism and graffiti offenses rarely harm people and are less likely than other offenses to result in the destruction of property (In re F.C. (Cal. Ct. App. 2011) 2011 WL 2001888).

Similarly, in two cases, courts held that the painting of graffiti by a tenant did not cause serious damage and was not grounds enough to terminate the lease (Sumet I Assocs., L.P. v. Irizarry (App. Term 2011) 933 N.Y.S.2d 799; Marbar, Inc. v. Katz (N.Y. Civ. Ct. 2000) 183 Misc. 2d 219).

On the other hand, while discussing direct accusations of graffiti, courts fail to see that, in a specific case, graffiti hardly caused any damage at all. Thus, one case revolved around graffiti painted under the Locust Street Bridge in the City of Milwaukee. Evidence proved that this area was marked with a ‘sheer amount of graffiti,’ which stayed there for years without the city abating it (State v. Lawhorn (Ct. App. 2007) 303 Wis. 2d 747). Moreover, the city did not remove the graffiti painted by the accused during the two years that passed between the act of painting and the court’s decision. Nevertheless, the court accepted the city’s assessment that restitution costs for the graffiti were $1000 (ibid., p. 12).

This uneven legal attitude – recognizing that graffiti is an expressive activity that does not causes serious damage while discussing it incidentally, but treating it as mere dirt to be cleaned and damage to be restored while dealing with it directly – is puzzling. The answer to this puzzle should be sought in the realm of narratives. Indeed, much of graffiti conveys one common message. This message reveals and challenges the hegemonic power of property, commerce, and politics that dominate our cityscapes. It rejects the authority of art institutions and the market to decide what ‘real’ art is (Young 2012, p. 311; Assaf-Zakharov & Schnetgöke 2021, pp. 36-38) – see Figure 11. In addition, graffiti resists the confinement of art within specifically designated spaces, such as museums and galleries, and opposes the isolation of art from everyday life (Baldini 2016, p. 190; Riggle 2010, pp. 243–44, 246) – see Figure 12. This is a message of a personal presence and individual placemaking (Davies 2012, 47–48). This message runs sharply contrary to the narratives conveyed by the official cityscapes: tidiness and niceness, consensus and content, the power of property and the dominance of consumption.

Figure 11. Gonzoe. Jerry Saltz, graffiti referring to Jerry Saltz calling ‘99% of graffiti […] generic crap’4 as well as to an artistic exhibit of a taped banana at Art Basel in Miami peeled and eaten by a visitor. Berlin 2020 (Yasharoff 2019).

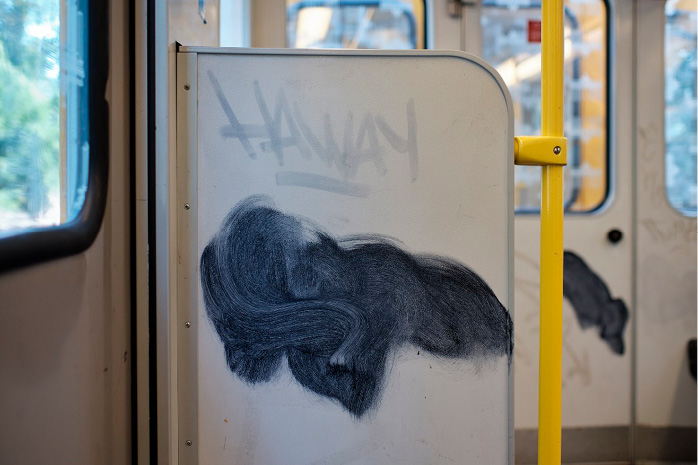

This counter-narrative of graffiti is easily understood on an intuitive level, and courts react to this subversive message with fierce protection of the official narratives conveyed by the cityscapes. Indeed, several scholars point out that the legal system greatly overreacts to graffiti, exaggerating its damages and creating a ‘moral panic’ (Ferrell 1996; Kramer 2016, p. 117). Jackob Kimvall has even suggested that the ‘war’ on graffiti is a form of iconoclasm, an ideological destruction of visual images (2007). Indeed, authorities often seek to distort graffiti images, even without removing them, with the sole purpose of defacing the painting (see Figures 13-16).

Figures 13-15. Examples of graffiti defaced by local authorities without restoring the surfaces. Berlin 2020-2021.

Figure 16. Dave the Chimp, a graffiti entering a dialogue with the half-hearted attempts of cleaning the wall. Berlin, 2017.

Figure 17. An example of an illegal paste-up that local authorities do not remove. Paris, 2020.

Thus, the war on graffiti is not a contest between expression and lack thereof, but between two conflicting types of expression – one official, monolithic and authoritative, the other unofficial, polyphonic and personal (Assaf-Zakharov & Schnetgöke 2021, pp. 27-28). Consequently, courts deciding on criminal accusations with graffiti actually decide on conflicts over narratives expressed in the cityscapes. Refusing to recognize any expressive content of graffiti equals a complete and uncompromised rejection of its narratives, the ultimate exclusion of these narratives from the scope of the legal debate.

Notably, some illegally painted pieces express understandable messages that do conform to the widely accepted narratives. Studying media releases over the last year, we have found that such pieces are usually celebrated rather than condemned. For instance, the Black Lives Matter movement’s messages on various city surfaces have been unanimously welcomed by the media in 2020 (Boyer 2020). Moreover, mayors of several cities have themselves written ‘Black Lives Matter’ with solid paint on city streets (e.g., Cruz 2020) – actions that formally fulfill the elements of the graffiti crime. At the same time, painting with chalk on city sidewalks messages criticizing a local police department has led to a criminal conviction with graffiti (Ballentine v. Las Vegas Metro. Police Dep't (9th Cir. 2019) 772 F. App'x 584). This highly selective enforcement reveals that the war on graffiti is much more about preserving the official cityscapes’ narratives against rebellious voices rather than protecting property against damage.

The same discriminatory policy is evident in the realm of aesthetic expression as well. Illegal pieces that are deemed ‘beautiful’ in accepted popular standards are celebrated as ‘contributions’ to the city (e.g., Friedman 2008), while ‘ugly’ pieces are condemned and punished (e.g., Angelini 2021). Unsurprisingly, ‘beautiful’ pieces almost never reach courts, since they are not reported to the police in the first place (See Figure 17).

Nevertheless, one such case did receive legal treatment, allowing an inquiry into the judicial position on illegal, but beautiful graffiti pieces. In this case, a court dealt with an illegal painting featuring a pink fairy in front of a school in (City of Ithaca People v Thomas (City Court of Ithaca 2014) 2014 NY Slip Op 24407). The judicial rhetoric in this case offers a glimpse into the real issue with most graffiti – its content. First, the court referred to the general case of graffiti – one that would probably have been decided applying the narrative of dirt to be cleaned:

Defacement of property (private or public) by graffiti is certainly a serious matter. This Court takes judicial notice that several years ago many properties within Ithaca were regularly defaced with ugly graffiti, and the blight was reaching near epidemic proportions (ibid., p. 2). [emphasis added]

Then, in an unprecedented move, the court openly acknowledged that graffiti might deserve differentiated legal treatment, depending on its expressive message:

Where the purpose of graffiti is not to deface, but to convey a social, political or artistic message, and such graffiti does not cause either actual or more than nominal damage to the public or private property, then the particular graffiti offense may be of such a de minimis nature that continued prosecution is unwarranted (ibid., p. 5).

The court then came to discuss the subject matter of the trial – the pink fairy, which it obviously liked, finding that the public property was not defaced, ‘but, in fact, a sprinkle of joyous whimsy was added’ (ibid., p. 7).

The Court can only imagine the laughs ringing musically through the late Spring morning air as children were welcomed by this spritely visage as they entered their school on one of those painstakingly long June days before the start of summer vacation.

The court then referred to the fact that the fairy had already been wiped away:

And the fairy—her pink flame is extinguished. She delighted Ithaca's children for just a moment and now like Lenore, she is nevermore. Her ephemeral existence is now only a distant memory like that of childhood days long gone. There is no bringing back this pink fairy of youth. […] How sad the children must have been when they looked for their little pink fairy, but only to discover her departed (ibid., pp. 7, 9).

Comparing these lines with a typical judicial discussion on graffiti removal – cleaning of dirt whose costs should be calculated – reveals how much depends on the content of the illegally painted messages. While most cases on graffiti do not even mention its content, here the whole decision is an extensive tribute to the pink fairy. While most cases of graffiti use the narrative of numbers described above, here the court cited many literary masterpieces, including ‘The Land of Heart's Desire,’ ‘The Raven,’ ‘The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,’ ‘Peter Pan’ and ‘Mary Poppins.’ Recognizing that illegal painting of graffiti constitutes a criminal act, the court nevertheless refused to convict the accused. It reasoned that doing otherwise would constitute a grave injustice, whereas the story of the criminal court system must be the story about justice and the inherent goodness of humanity (ibid., p. 11).

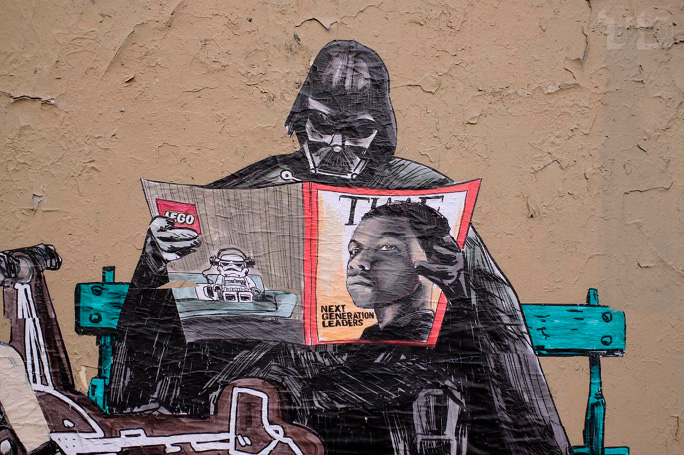

Another factor that weighs heavily in favor of accepting illegal graffiti rather than punishing it is fame. Pieces made by famous artists are celebrated by the media, local authorities, and homeowners (Barlow 2021). Thus, the well-known British artist Banksy paints on whatever surfaces he deems appropriate, including private houses and medical clinics, without asking anyone’s permission. His works are highly appreciated, sometimes safeguarded by protective casting, and restored by local authorities when needed (See Figure 18)5. ‘Vandals’ painting over his works are severely condemned in mass media and punished as criminals, while politicians express deep regret for not having done more to preserve the masterpieces on time (e.g., Brown 2019; Hutson 2020).

Figure 18. Banksy’s tribute to Jean-Michel Basquiat on Barbican Centre, protected by Plexiglas. London 2019.

Naturally, famous artists are rarely accused of painting graffiti6. Yet, we were able to identify one such case (People v. Fairey (2018) 325 Mich. App. 645). In 2015, the famous artist Frank Shepard Fairey was invited by a real estate firm to create murals on its buildings in Detroit. In an interview, Fairey admitted: ‘I still do stuff on the street without permission. I’ll be doing stuff on the street when I’m in Detroit’ (ibid., p. 647). Following this confession, the police looked for and found illegally attached posters bearing Fairey’s motives on various locations in Detroit, and accused him of making graffiti. The very first lines of the decision unmistakably identify the judge’s admiration for Fairey’s works:

Frank Shepard Fairey is an internationally acclaimed artist best known for creating a red, white, and blue poster of then presidential candidate Barack Obama, entitled Hope. […] Fairey’s work combines elements of graffiti and pop culture; his themes often thumb a nose at authority and champion dissent (ibid., pp. 646-647).

Turning to actions of the police officer, McKay, the judge described them as follows:

On May 22, 2015, McKay went on a hunt for illegal art containing the Obey Giant or other Shepard Fairey-esque images. She found posters harboring the icon … in 14 places around the city[.] … McKay decided that Fairey must have put up the illegal posters while he was in town (ibid., p. 648).

This language, ridiculing the police officer’s actions and admiring the artist, leaves no doubt about the outcome of the case. Indeed, noting that ‘[s]everal holes in the prosecution’s evidentiary canvas doom its case’, the court found that there was no sufficient evidence that Fairey himself pasted the posters onto the buildings (ibid., p. 650). Unlike in cases with ‘ugly’ graffiti, in which artists are routinely accused of painting all tags similar to theirs (e.g., State v. Foxhoven (2007) 132 Wash. App. 1053; People v. Lopez (Cal. Ct. App. 2014) 2014 WL 68267), here the court insisted on direct evidence linking Fairey with the respective posters. Referring to his statement to the press, the court remarked:

‘[D]oing stuff on the street without permission’ sounds like an artist playing a street-smart scoundrel. […] It is not a crime to fantasize (even publicly) about putting up posters on property that does not belong to you. Vincent van Gogh said, ‘I dream of painting and then I paint my dream.’ Fairey dreamed aloud, but no evidence exists that Fairey’s hands painted his dreams or even touched the 14 tagged buildings (People v. Fairey (2018) 325 Mich. App. 645, 651).

Although Fairey was acquitted because of insufficient evidence, the judicial rhetoric plainly reveals how the judge saw this case: a genius artist hunted by not-so-intelligent police officer.

The stories of pink fairy and Shepard Fairey reveal once again the preferential legal treatment of artistic pieces conforming to commonly accepted standards of beauty and those created by famous artists. This time the distinction is made in the context of criminal law, which is especially disturbing. Just think that bearing criminal liability or escaping it may depend on factors such as how beautiful the illegal piece is, in the judge’s eyes, and how famous its painter is (See Figures 19-20).

Figure 19. Frank Shepard Fairey, a commissioned work. Paris 2020.

Figure 20. Frank Shepard Fairey, an uncommissioned work. Paris, 2020.

To sum up, while some forms of graffiti are condemned as ‘vandalism’ and ‘property destruction,’ others are perceived as art or important social comment. Depending on the style and the content of a message, its creator may be imprisoned or praised, while the works themselves may be either whitewashed, left untouched or carefully preserved.

Conclusion: Imagine a City of Free Narratives

We have now completed our journey through the cityscapes. It is time to look back and reflect on the stories urban public spaces tell and the stories they conceal. As we have seen, some narratives systematically prevail in legal conflicts, while others constantly lose. Hence, we can conclude that while dealing with conflicts over the cityscapes, the legal system shows a strong tendency to side with specific narratives and disadvantage others. Let us briefly overview the balance of power our study has revealed.

One of the most powerful narratives the cityscapes promote is the consumerist ideology. Because of the strong hold of this ideology on our cultural discourse, speech favoring it – promoting consumption or endorsing business – is perceived as neutral and non-ideological. Hence, public authorities striving to avoid controversy often favor this kind of speech over alternative voices. Thus, a city would rather have a Christmas display thanking sponsors than one questioning religious views; and a city-sponsored event would rather accept an exhibit promoting the consumption of faux leather than one opposing animal torture (for a more general discussion of the legal tendency to favor consumerism see Assaf 2012, 2014).

Another important area of conflicts over cityscapes is (anti)religious views. While common Christian motifs usually have no difficulty entering the shared visual spaces, expressions challenging the widespread practicing of Christianity, opposing religion, suggesting alternative (Summum) religious views, and displaying Christian symbols in a disrespectful way were all banned from public view.

Last but not least, the legal system envisions cityscapes adorned by easily understandable, non-controversial, preferably cheerful and entertaining art conforming to widespread aesthetic standards. Pieces that gain wide social acceptance and recognition by the established art institution sometimes enjoy the highest form of protection – preservation against destruction – especially if made by famous artists. By contrast, pieces raising public controversy – due to their expressive message of aesthetic qualities – are routinely expelled from the cityscapes. All in all, our inquiry has revealed cityscapes as powerful sites of reinforcing dominant social voices and silencing dissent.

We suggest redefining the boundaries of physical property so as to restrict—with certain exceptions—private and public owners’ control over surfaces that shape our urban landscape. These surfaces will then be used as a medium of free visual expression, subject to general limitations on free speech, such as libel, incitement, and obscenity. This will reconceptualize the shared spaces as a public ‘forum’ in its classic sense; that is, a place of discussion, opinion exchange, and purely aesthetic or even entirely incomprehensible expression. It will grant city residents the right to design their urban spaces as an ever-changing collage of their expressions – see Figures 21-22.

Figures 21-22. Street views in Berlin, 2020, 2018.

Our proposal corresponds with the discourse on ‘the right to the city.’ A term coined by Henri Lefebvre, the right to the city entails two rights for city inhabitants: participation in decision making regarding public space, and appropriation of it (1996; see also Purcell 2014, p. 149; Harvey 2003, p. 941) – the latter being the relevant aspect for our discussion. Following Marx, Lefebvre distinguishes between the use value of city spaces and their exchange value, e.g., urban space as real estate belonging to a corporation. The right to the city does not refer to private ownership (exchange value), but rather to maximization of use value for residents over the exchange value for others. The ideal of urban citizenship and democratic participation is frequently limited either by class differences (marginalization and exclusion) or political pressures. This calls for reconceptualizing the distribution of power and a new understanding of human rights. Discussing the right to the city, David Harvey suggests:

The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights (2008, p. 23).

The right to the city is the right of the residents to actively engage in the creation and recreation of their shared spaces rather than passively access an environment shaped and policed by property owners and city planners (Lefebvre 1996, p. 145; Harvey 2003, p. 939; Purcell 2014, p. 150). This is a right to create public spaces as a commons of active democratic participation (Harvey, ibid. p. 941). Although it is far from clear how the right to the city should be asserted, allowing writing and painting on city surfaces is plausibly an important step in this direction.

The idea of taking external surfaces out of the owner’s control might sound radical. Yet, property is actually a bundle of privileges established by law; the content of this bundle undergoes changes from time to time (Peñalver & Katyal 2007). Consider, for instance, that at the time of the first sit-ins, it was unimaginable that grocery shop owners would be obliged to open their stores to Afro-Americans. But the Civil Rights Act of 1964 did just that, redefining the boundaries of property so as to take away a portion of the owners’ control over their property for the sake of advancing equality in the field of goods and services (ibid., pp. 1121–1122). In a sense, we propose a similar move – taking part of the owners’ control for the sake of advancing equality in the field of free speech. Our proposal seeks to grant equal speech rights in the cityscapes to everyone, regardless of social status or economic power.

As our inquiry has shown, the real opposition to graffiti has everything to do with its content: while pieces conforming to the official urban narratives are positively received and frequently preserved, dissenting expressions are whitewashed, condemned, and punished. Our proposal seeks to undermine this hegemony of the official narratives. Our shared visual environment should bear a great variety of voices and stories, rather than displaying the same authoritarian narratives – of consumerism, widely accepted political views, Christianity, and non-controversial art – over and over again. The suggested legal change will make the discourse taking place in our shared cityscapes genuinely egalitarian, inclusive, and multi-voiced. This will give a chance to various social groups to voice their views, beliefs, and concerns (See Figures 23-24). The narrative opposing violence against the black community was allowed into the cityscapes only after it had entered the mainstream discourse. During the long years of struggle, the cityscapes remained out of reach of this movement. Had this significant medium of expression been freely accessible, the voice of ‘Black Lives Matter’ could have been heard much earlier, allowing a non-violent avenue for accelerating social change (Sholette 2017, pp. 127, 151–234).

Figure 23. Sozi36, Berlin 2019.

Last but not least, our proposal seeks to open up the playground of visual art, undermining the dominance of experts, official institutions, market value, and fame. The field of visual artistic expression needs space for free and uncontrolled creative discourse, space that would provide opportunity for various voices, especially those that have not yet been heard. Our society provides enough room for art that fits into the existing standards and norms, and too little space for art created without seeking to meet the popular taste or to gain positive critique: art for the sake of art (See Figure 25). Pieces that look ugly or unintelligible today may later on be understood and valued if given the chance to participate in the artistic discourse. Notably, with some portion of art, this will never happen. But this is no reason to wipe away artistic expression seeking its way into our shared visual environment.

Figure 25. Huskies, Berlin 2019.

References

Literature:

American Law Reports, 2021, 6th ed., West, Eagan, MN.

Angelini, D. 2021, ‘Blast for vandals as town centre graffiti problem rockets in lockdown’, Swindon Advertiser, 27 January 2021. Viewed 2021-12-28. https://www.swindonadvertiser.co.uk/news/19040023.shop-owner-hits-vandals-cover-town-centre-graffiti-lockdown/

Assaf, K. 2012, ‘Magical Thinking in Trademark Law’, Law and Social Inquiry, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 595–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.2011.01271.x

Assaf, K. 2014, ‘Capitalism vs. Freedom’, NYU Review of Law & Social Change, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 201-268. https://socialchangenyu.com/review/capitalism-vs-freedom/

Assaf-Zakharov, K. & Schnetgöke, T. 2021, ‘Reading the illegible: Can law understand graffiti?’ Connecticut Law Review, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 117-153. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review/465

Baldini, A. 2016, ‘Street art: A reply to Riggle’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 187-191. https://doi.org/10.1111/jaac.12261

Barber, B. R. 2007, Consumed: How markets corrupt children, infantilize adults, and swallow citizens whole, W. W. Norton, New York.

Barlow, A. 2021, ‘Banksy in Sussex: Could Newhaven A259 stencil be latest work?’ The Argus, Viewed 2021-12-28. https://www.theargus.co.uk/news/19083694.banksy-sussex-newhaven-a259-stencil-latest-work/ (Accessed: 28 December 24, 2021)

Boyer, R. 2020, ‘How graffiti artists are propelling the vision of the Black Lives Matter movement’, ARTSY, Viewed 2021-12-28. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-graffiti-artists-propelling-vision-black-lives-matter-movement

Brown, K. 2019, ‘Banksy’s famous Brexit mural has mysteriously disappeared from the side of a building in a British seaside town’, Artnet News, Viewed 2021-12-28. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/banksy-mural-disappeared-1636069

Buckley, J. M. 2018, ‘People in place: Local planning to preserve diverse cultures’, In: Labrador A. M. & Silberman N. A. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public Heritage Theory and Practice, Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 295-308.

Cruz, A. 2020, ‘DC mayor unveils 'Black Lives Matter' painted on streets of capital’, ABC News, Viewed 2021-12-28. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/dc-mayor-unveils-black-lives-matter-painted-streets/story?id=71088808

Davies, J. 2012, ‘Art crimes? Theoretical perspectives on copyright protection for illegally-created graffiti art,’ Maine Law Review, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 27-55. https://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1135&context=mlr

Docuyanan, F. 2000, ‘Governing graffiti in contested urban spaces’, PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1525/pol.2000.23.1.103

Fernandes, J. 2016, ‘The politics of dis-belonging’, Shelterforce, Viewed 2021-12-24. https://shelterforce.org/2016/09/21/the-politics-of-dis-belonging/

Ferrell, J. 1996, Crimes of style: Urban graffiti and the politics of criminality, Northeastern University Press, Boston.

Friedman, V. 2008, ‘Tribute to graffiti art: 50 beautiful street artworks,’ Smashing Magazine, 14 September. Viewed 2021-12-28. https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2008/09/tribute-to-graffiti-50-beautiful-graffiti-artworks/

Harvey, D. 2003, ‘The right to the city’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 939-941. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2003.00492.x

Harvey, D. 2008, ‘The right to the city’, New Left Review, vol. 53, pp. 23-40. https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii53/articles/david-harvey-the-right-to-the-city

Hutson, M. 2020, ‘Bristol Valentine's Day Banksy mural vandalised’, BBC, 15 February 2020. Viewed 2021-12-28. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-bristol-51515557

Jacobs, J. 1961, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Random House, New York.

Kimvall J. 2007, ‘Bad graffiti gone good street art’, In: Nilsson, H. (ed.), ‘Placing art in the public realm’, Konstfack University College of Arts, Crafts and Design, 28 September 2007, Stockholm, Sweden. Viewed 2021-12-28. https://www.academia.edu/1121025/Bad_Graffiti_Art_Gone_Good_Street_Art

Kramer, R. 2016, ‘Straight from the underground: New York City’s legal graffiti writing culture,’ In: Ross J. I. (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Aart, Routledge, Abingdon, pp. 113-123.

Lefebvre H. 1996, ‘The right to the city’, In: Kofman E. & Lebas E. (eds.), Writings on Cities, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford, pp. 63-183.

Marcus, C. C. 1975, Easter Hill Village: Some Social Implications of Design, Free Press, New York.

Peñalver, E. M. & Katyal, S. K. 2007, ‘Property Outlaws’, University of Pennsylvania Law Review, vol. 155, no. 5, pp. 1095-1186. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/penn_law_review/vol155/iss5/2

Purcell, M. 2014, ‘Possible worlds: Henri Lefebvre and the right to the city’, Journal of Urban Affairs, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 141-154. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12034

Riggle, N. A. 2010, ‘Street art: The transfiguration of the commonplaces,’ The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 243-257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6245.2010.01416.x

Sholette, G. 2017, Delirium and Resistance: Activist Art and the Crisis of Capitalism, Pluto Books, London. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1n7qkm9

Yasharoff, H. 2019, ‘A man ate $120,000 duct-taped banana art: “I really love this installation. It's very delicious”’, USA Today, 9 December 2019. Retrieved 2021-12-28. https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/2019/12/09/banana-priced-120000-exhibit-art-basel-eaten/2628306001/

Young, A. 2012, ‘Criminal images: The affective judgment of graffiti and street art’, Crime Media Culture, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 297-314. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659012443232

Legal Cases:

Hague v. CIO (1939) 307 U.S. 496

Metromedia, Inc. v. City of San Diego (1981) 453 U.S. 490

Muir v. Ala. Educ. Television Comm'n (5th Cir.1982) 688 F.2d 1033

Clark v. Community for Creative Non–Violence (1984) 468 U.S. 288

Serra v. U.S. Gen. Servs. Admin. (2d Cir. 1988) 847 F.2d 1045

Ward v. Rock against Racism (1989) 491 U.S. 781

City of Allegheny v. Am. Civil Liberties Union Greater Pittsburgh Chapter (1989) 492 U.S. 573

Doe v. Small (7th Cir. 1992) 964 F.2d 611

Botello v. Shell Oil Co. (1991) 280 Cal.Rptr. 535

Cannon v. City and County of Denver (10th Cir. 1993) 998 F.2d 867

Nat'l Paint & Coatings Ass'n v. City of Chicago (N.D. Ill. 1993) 835 F. Supp. 421, rev'd, (7th Cir. 1995) 45 F.3d 1124

Sherwin-Williams Co. v. City & Cty. of San Francisco (N.D. Cal. 1994) 857 F. Supp. 1355

Comite Pro-Celebracion v. Claypool (N.D. Ill. 1994) 863 F. Supp. 682

Carter v. Helmsley–Spear, Inc. (S.D.N.Y.1994) 861 F.Supp. 303, aff'd. in part, vacated in part, rev'd in part, 71 F.3d 77 (2nd Cir.1995)

English v. BFC&R East 11th Street LLC (1997) WL 746444

Nat'l Endowment for the Arts v. Finley (1998) 524 U.S. 569

Martin v. City of Indianapolis (7th Cir. 1999) 192 F.3d 608

Downs v. Los Angeles Unified Sch. Dist. (9th Cir.2000) 228 F.3d 1003, cert. denied, (2001) 532 U.S. 994

Marbar, Inc. v. Katz (N.Y. Civ. Ct. 2000) 183 Misc. 2d 219

People for Ethical Treatment of Animals v. Giuliani (S.D.N.Y. 2000) 105 F. Supp. 2d 294

Wells v. City & Cty. of Denver (10th Cir. 2001) 257 F.3d 1132

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Inc. v. Gittens (D.C. Cir. 2005) 414 F.3d 23

Phillips v. Pembroke Real Estate, Inc. (1st Cir.2006) 459 F.3d 128

State v. Foxhoven (2007) 132 Wash. App. 1053 (2006), aff'd, 161 Wash. 2d 168

In re T.P. (Cal. Ct. App. Jan. 18, 2007) 2007 WL 118346

State v. Lawhorn (Ct. App. 2007) 303 Wis. 2d 747

Pleasant Grove City, Utah v. Summum (2009)1 555 U.S. 460

U.S. v. Marcavage (3d Cir. 2010) 609 F.3d 264

In re F.C. (Cal. Ct. App. 2011) 2011 WL 2001888

Sumet I Assocs., L.P. v. Irizarry (App. Term 2011) 933 N.Y.S.2d 799

Newton v. LePage (1st Cir. 2012) 849 F. Supp. 2d 82 (D. Me.), aff'd, 700 F.3d 595

People v. Lopez (Cal. Ct. App. 2014) 2014 WL 68267

People v Thomas (City Court of Ithaca 2014) 2014 NY Slip Op 24407

Pindak v. Dart (N.D. Ill. 2015) 125 F. Supp. 3d 720

People v. Santori (2015) 243 Cal. App. 4th 122, 196 Cal. Rptr. 3d 500

People v. Quezada (Cal. Ct. App. 2016) WL 2627042

People v. Aguilar (Ct. App. 2016) 209 Cal. Rptr. 3d 313

People v. Fairey (2018) 325 Mich. App. 645

Holbrook v. City of Pittsburgh (W.D. Pa. 2019) 2019 WL 4409694

Ballentine v. Las Vegas Metro. Police Dep't (9th Cir. 2019) 772 F. App'x 584

Urbain Pottier v. Hotel Plaza Las Delicias, Inc. (D.P.R. 2019) 379 F. Supp. 3d 130

Baird v. Town of Normal (C.D. Ill. 2020) WL 234622

1 Assaf-Zakharov, K. & Schnetgöke, T. (2021). ‘(Un)official Cityscapes: The Battle over Urban Narratives’, Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 57 (forthcoming).

2 But note that government speech incorporating religious messages is occasionally challenged as violating the Establishment Clause. The legal practice dealing with such claims is somewhat inconsistent: compare, e.g., City of Allegheny v. Am. Civil Liberties Union Greater Pittsburgh Chapter (1989) 492 U.S. 573 (‘display of crèche violated establishment clause’); with Doe v. Small (7th Cir. 1992) 964 F.2d 611 (allowing to display religious paintings in a public park).

3 https://ncac.org/resource/national-endowment-for-the-arts-controversies-in-free-speech.

4 https://twitter.com/jerrysaltz/status/1212845297656840192?lang=de

5 This practice bears an interesting contradiction to jurisprudence holding that VARA cannot protect works illegally made: Botello v. Shell Oil Co. (1991) 280 Cal.Rptr. 535; English v. BFC&R East 11th Street LLC (1997) WL 746444.

6 There are exceptions to this rule, however. Thus, in 2011, a well-known graffiti artist, Revok, was sentenced to 180 days imprisonment for vandalism. While he was serving his time, his works were exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (Young, 2012, p. 308; Assaf-Zakharov & Schnetgöke 2021, p. 11).