Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 14, No. 1

2022

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

From the Stands to the Arena of Social Movements: Post-2011 Football Terrace Chants in Tunisia

Soumaya Abdellatif1,*, Safouane Trabelsi2, Zahia Ouadah Bedidi3

1 Ajman University, Ajman, United Arab Emirates, s.abdellatif@ajman.ac.ae

2 University of Tunis/University of Tunis El Manar, Tunisia, safouane.trabelsi@etudiant-issht.utm.tn

3 Université de Paris and Université Côté d’Azur, CNRS, IRD, Unité de recherche Migrations et Sociétés F75013 Paris, France, ouadah@ined.fr

Corresponding author: Soumaya Abdellatif, College of Humanities and Sciences, Al Jurf, Block C, J2 Building, Ajman University, Ajman, United Arab Emirates, s.abdellatif@ajman.ac.ae

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v14.i1.7988

Article History: Received 23/11/2021; Revised 14/02/2022; Accepted 23/02/2022;

Published 31/03/2022

Abstract

This paper discusses the evolution of social criticism reflected in the Tunisian Ultra groups’ football chants and investigates the Ultras’ involvement in social movements. To address this issue, we developed a database of mostly published Ultra songs found on social media which was analyzed using thematic analysis. Findings indicate that the Ultra phenomenon in Tunisia established its influence from the first decade of 2000, as a social pattern criticizing power, through confrontation of the regime inside the stadiums, and culturally through the production of a set of critically-loaded artistic expressions. We conclude that the extension of the circle of influence of Ultra groups is indicative of an overthrowing of cultural legitimacy standards but significantly is also reflective of the emergence of new social actors capable of redistributing power through their intense politicization of interactions that prior to 2011 had been mostly social.

Keywords

Tunisia; Chants Virages; Football Terrace Chants; Social Movements; Ultra Groups

Introduction

With the surge of popular protest movements within the context of the Arab Spring, numerous new forms of expression have risen to prominence on the Tunisian art and cultural scene. Embracing a criticism-bound tendency and challenging the mainstream establishment in place, these forms of expression have gained momentum through significantly broad dissemination (Saidani 2018a, p.112-113). Formerly, they were perceived as forms articulating a counterculture (underground culture), or, at least, standing on the margins of the dominant legitimate art forms of expression which were adopted by elites whether closer to power or opposing to it. Amongst these newly emerging forms of critical art voicing a social protest are the further chants of what is commonly known in French as “chants virages”1 most often performed by the so-called “Ultras Groups” at football grounds. Over the past two decades, Ultra groups have emerged as some of the most powerful actors on the socio-political scene. They notably comprise cheerleaders commonly referred to as “radical fans” (Frazer 2005, p. 278; Tsai 2020, p. 127). These fans have a keen sense of loyalty to their sports clubs in general and specifically to their soccer clubs.

To this end, our focus on such a phenomenon more or less falls within the course of the heated controversy it has created around the extent of its contribution and the scope of its engagement in the protest social movements through cultural practices and diverse expressive art forms dissimilar to those appraised by the legitimate culture. A quite assertive example of such an effect is the chant virage “Fibladi Dhalmouni” (Wronged in my own country) initially performed, in defiance, by the Moroccan football Raja Al-Baydhaoui team supporters who voiced their social woes. The chant swiftly spread far beyond to reach out across the Arab Maghreb countries hence, turning into an anthem chanted and savored by most Ultras groups. Such criticism-charged chants and others serve as a significant indicator of a set of social transformations witnessed by the Maghrebi society whereby football stadiums turned into a protest arena, thus substituting for traditional protest spheres (Abde Latif 2019, p.18).

In Tunisia, a country undergoing a dissimilar political context, however, the salience of similar chants has been quite noticeable. For instance, “Ya Hayetna” (Ohh Our life!!), belted out by the Club Africain (CA) fans, alongside “African Winners” and Etoile Sportive du Sahel (ESS) support group Red Brigade’s chant entitled “Cortège El Mout” (Death Parade) have significantly impacted the public opinion amidst a convulsed political and economic context. Lyrical songs have overwhelmed the stadiums in defiance of the current context characterized by the decline in purchasing power, the spread of violence and a significantly declining level of trust in politicians 2.

These reasons and a lot more have contributed to the shift of chants virages where criticism is set at the forefront, from the standing terraces of the stadiums into an anthem performed by protesters resisting the current political process: protesters who have brought the chants to the attention of journalists, media commentators, scholars, civil society activists and political parties who have opted for shifting patterns of identifying a new actor mapping its insights and criticism. As part of the protest, Ultras expound new expressive art forms which have a direct impact on public opinion through the spread of chants going viral on social media sites3 thereby enabling them to occupy a crucial part of the country’s media and political current status.

Following this argument, this study investigates specifically the evolution of social criticism impregnated in the songs of the Tunisian Ultras groups. Social criticism manifests itself as a social act through which a group of individuals voice their grievances in the public arena. Their goal is to communicate with other groups and engage them in constructing an active discourse on the conditions of collective life. Under these circumstances, social criticism is a grassroots movement distinct from the so-called elitist criticism that is transacted within political institutions with the aim of modifying the positions of power to ensure the stability of the system. In this sense, social criticism tackles the issues confronted by vulnerable groups suffering from injustice and seeking to alleviate their pain and suffering (Barry 1990, pp. 262-263).

We will further scrutinize the scope of their involvement in social movements through the production of expressions comprising the overturn of legitimate culture and a change in the boundaries of the traditional customary space of the social act. In this vein, we intend to address this research problem by answering the following set of sub-questions:

• How can we distinguish Ultras groups in Tunisia in terms of size, and geographical breakdown by groups and regions?

• Can we identify the scale and content of their song production? How is the content of such chants expressive of a no-holds-barred criticism dimension? and,

• How far does it relate to the socio-political contexts which sparked it?

Mindful of the research question as such, we intend to investigate the proposition that the spread of the impact radius of Ultras groups is indicative of a change in the social make up and a reversal of the cultural legitimacy-related standards and the rise of new social actors capable of re-allocating the microphysics of power through the massive politicization of the previously most neutral social pattern existing before the 2011 revolution.

For the purpose of the present research, we intend to seek in-depth knowledge of new emerging actors through a thorough study of such groups’ most salient artistic outputs which seem to be embodied in the stadium’s chants virages, and performed at the football grounds. To illustrate how these chants have been part of the changes within the framework of a protest spectrum, we intend to explore the shift phases that these relevant chants have undergone and whose content has turned from cheering and being purely team supporting-related songs in the stadium stands, into an off-stadium sphere engagement in the social movement. This would allow for further scrutiny of the shift into alternative spaces of protest by broadening the scope of the social act and developing the critical acumen against power and socio-political elites.

Literature Review

The Ultras phenomenon has so far caught the scholars’ interest in the last two decades. Discerning the need for more rigorous research on such a thematic issue was mainly driven by the European research landscape, triggered by the mounting escalation of violence and growing extremism among Ultras groups. This surge is politically charged with a critical edge openly proclaiming a protest dimension for which the authority and political and security power organs are the fundamental target. This surge of violent rejection was also associated with the tendency towards embracing a set of extremist ideas anchored, to an increasing extent, in a chauvinistic, racist, and nationalistic dimension (Hourcade 2000, p.107-125).

Notwithstanding and with respect to the Arab level, there has been little research endeavor or scholarly literature to fully engage in the investigation of Ultras. There was fairly little relevant research, with much exclusive focus, in recent decades, on the lone case of Egypt. Such studies have built upon the approach of political sciences in terms of theoretical framing. This is why we focus our study on Ultras in Tunisia a country perceived as the historically first incubator for the Ultras groups across the Arab and Maghrebi level. These emerging driving forces for change have taken effect, then later spread across the rest of the Arab countries throughout the beginning of the third millennium (Chenouda 2016, p.6).

Much of the literature and most scholarly studies have almost exclusively focused on the relationship between Ultras groups and political actors as well as on the role they have so far played in the pre/post ‘Arab spring’ social movements. Such studies focused on manifold topics. The overarching focus has been laid, among other topics, on the identity of such groups with an attempt to classify them within spontaneous social movements or as structured political or quasi-political organizations and staging a conduct overly mired in violence.

Such studies have mostly drawn on the analysis of sampling statements of fandom of the Ultras and on the police forces and football fans representations (Chenouda 2016, p.1-32) of such propositions and expressions on the stadium terraces. Other studies have nonetheless focused on addressing politics, management, and economic dimensions of the present phenomenon. This has been carried out through scrutinizing its structure and its funding sources aligned with the exploration of its relationship with the conflicting political parties, with Muslim Brotherhood by far the most prominent actor in the circumscribed context of the Arab Spring and its aftermath, along with the spillover effect and the banning of its activities in 2015 (Sayed Ahmed 2018).

On the Maghreb level however, studies have predominantly focused on the phenomenon of momentous violence escalating in the stadiums through a mode of dissembling fundamental components of Ultras culture intertwined with the analysis of security policies taken by the authorities poised to reduce violence and have a stranglehold on such groups. Given the difficulty in engaging with such an area, the content flow flourishing on social media platforms has been a significantly relevant subject matter for research and analysis (Alomari 2019).

Social movements and emergence of non-traditional actors

Supporters’ groups, or rather radical cheerleaders, have risen to prominence since the twenties (1920s) in Latin American countries (Saidani 2018b). Likewise, the phenomenon has extended across the European sports arena since the 1960s in three major waves. The first of these represents the Italian traditions or what is commonly known as Ultras. The second wave, however, consists of the Anglo-Saxon tradition or Hooligans. South American traditions are featured in the third wave, and labelled as Barras Bravas, violent organized groups of supporters. The differences between these three waves can be distinguished on two main points: namely, their attitude towards violence and independence regarding the club’s managing bodies or other sports and non-sports institutions.

This trend of operating in terms of resistance and advocacy of independence from all institutions of any kind has been a constant feature. Accordingly, it would seem to be the all-important issue on which Ultras groups lay most emphasis while upholding the idea of self-financing of the group and its activities. Such an attitude might not arguably be the case of the Barras Bravas groups as groups supported both financially and morally by the clubs’ management (Hourcade 2000, p.109). However, in no case does this imply a full-fledged absolute dependency as these groups often exert high pressure on club managers in a kind of reverse dependency. With respect to the controversy between Ultras, hard-core supporters and Hooligans, this is to be interpreted in the issue of violence, perceived by Hooligans as part and parcel of the group’s cheering act (Hourcade 2000, p.33). Instances of violence and assault targeted at the opposing supporters and the security forces have been a feature of Hooligans’ aims in their own right. Nonetheless, Ultras groups disapprove of such acts, yet have to resort to violence in instances of necessity, very often imposed by the adversary (supporters of another group or the police) in their attempt to humiliate them or their team, restrict their liberty inside the stadium, or further threaten their existence or the continuity of their groups.

Such new forms of team support displayed in the stadiums are associated, as are other forms, with a set of social changes witnessed by the European scene in the sixties (1960s). The most prominent change was featured in the common youth awareness of their interests as a category associated with their capacity of the common act and synonymous the creation of socio-political change (Hourcade 2000, p.33). It is this combination in this context, that spurred the upsurge of Ultras groups, gathering young sports enthusiasts, mainly football supporters, around a set of radical beliefs and mindsets. This has been countered with the interests of actors who have dominant control over sports and football teams (whether players, clubs’ management, investors, leagues, traditional club lovers) (Hourcade 2000, p.33).

This phenomenon was going viral across European countries during the1970s and1980s. Such a swift expansion reflected the youth’s growing sense of disenchantment and loss amidst ideological and political conflicts in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s (the height of the Cold War). Such conflicts shifted the interest of young people who sought re-orientating the point of the compass towards sports and football. This has spurred the popularity of football (Testa 2009, p.55) which took hold to become the first congregation of youth groups, within a creative framework. The response of disillusionment was subsumed under a nascent generation daring to voice its defiance of a new sports culture which had drifted into business, football commodification and purposeful marketing, apparent in the milking of the game by investment and wealth creation. These practices were undertaken at the expense of sporting values and a set of other social values that Ultras groups strongly assert and believe in, most important of which is loyalty and sacrality of belonging.

Resistance of the business-like tendency was reflected in the upsurge of anti-Modern Football mentality, embracing alluring slogans including: “Against Modern Football Movement” and “Our passion is not a Business” (Numerato 2014, p.121). It is quite worth revealing that such resistance has extended beyond criticizing the transformations introduced by the Neoliberal system and the bourgeoisie into the realm of sports, to further address contentious political and economic issues extending beyond stadium stands (Testa 2009, p. 55-56). Such actions, which were initially left-wing, or anarchist in nature, have currently lurched into far-right contents after the surge of nationalist chauvinistic movements in Europe. Many of the European Ultras groups embrace such viewpoints within the rise of racism gripping stadiums and engulfing the playing fields. However, these far-right expressive contents hardly mirror the Ultras groups’ affiliation or are suggestive of their organizational allegiance. Furthermore, despite determined efforts by the extremist political forces (be they left-wing or right-wing) to polarize the group, the Ultras have oftentimes sustained their independence and anarchic character holding their negative position, resisting any form of authority and rejecting any institutional commitment and restrictions of their freedom (Testa 2009, p. 56-57).

On the Arab level, however, amidst the Arab Spring moves; Ultras groups have witnessed a salient transformation in terms of their relationship with political matters. Such a transformation constituted a driving force to efficiently gain a significant share and conquer a prominent position among participating actors in the movements. This was due to the prior 2011 experience they have acquired and the lessons they have learned. Ultras activities were then staged through frequent confrontations with the authorities and the security forces at the stadiums (Dorsey 2012, p.411-418). Such a change in the repertoire and the shift of protest modes towards expression of political opinion, political criticism during “contention gatherings”, engagement in public life and the occupation of real public space as a voiced act of protest whether in or outside stadiums; would lead us to consider the issue of Ultras’ engagement in the social movements. In this sense, such could be identified, borrowing Charles Tilly’s definition of social movement as: A sustained series of interactions between national powerholders and persons successfully claiming to speak on behalf of a constituency lacking formal representation, in the course of which those persons make publicly-visible demands for changes in the distribution or exercise of power, and hack those demands with public mass demonstrations of support (Tilly et al., 2004, p.3-4).

Ultras’ engagement in the protest movements has built upon the elaboration of an anti-legitimate culture and the advocacy for a popular culture while voicing claims of its class. By legitimate culture we mean the not well appreciated dominant culture embraced by the bourgeois elite in power holding a monopoly over capital and capable of reproduction to sustain its hegemonic and monopolizing position. Conversely, there exists a marginalized or non-legitimate culture embraced by classes of lower rank (that is, the grassroots) attempting to emulate the higher-class lifestyle hence, seeking to gain a legitimacy of access to the privileges or the particular lifestyle that high class represents (Bourdieu 1995). Nonetheless, it is quite worth revealing that this passage to legitimate culture is by no means acquired arbitrarily. Its entitlements or rather its legitimization is subject to conditions and courses through actors imposed by class power in harmony with its interests (Giet 2004, p.15-17). By way of illustration, Rap gained its legitimacy as an art form from the dominant bourgeoisie which came to consider it as worthy of consumption. Other classes, lower in power and prestige, followed suit, attempting to copy the habitus of the dominant classes, to use Bourdieu’s term (1977). What this means is that such art should meet the conditions of consumer art in substance, form, and marketing approach. Substance covers such aspects as thematic issues and the language used. Form references the necessary visual dimension relating to shooting high quality video clips, and the marketing approach relies on YouTube, airtime on the radio and TV Channels, bookings, and the like. Finally, Rap would have had to be adopted by actors subjugated by and mirroring the dominant authorities through such means as media over media and audiovisual production institutions.

Such new art forms have revealed the emergence of new, non-traditional actors on the socio-political and art scene. We consider non-traditional actors those being external to organizations, parties, institutions and historical groupings or communities with differing conceptions. They are actors known for their critical protest tendency and pronounced dissidence to the policies of existing regimes (Woltering 2013, p.290). Several studies conducted during the aftermath of the “Arab Spring” have revealed that understanding such a wave of social and political changes can by no means be achieved through studies of classical actors in civil society but rather through exploring steadily-growing exceptional groups or non-state actors who have not been recognized or have been denied scrutiny and, as key to understanding, have yet to be explored (Aarts & Cavatorta 2013).

Research Methodology

We have adopted in the present study an explorative qualitative research approach while pursuing a communicative content analysis of chants virages. Our intent is to interpret meaning from the content: leading towards content analysis of chants produced by Ultras Groups and channeled on social media websites (mainly YouTube and Facebook). These terrace chants are meant to be sung by passionate affiliated groups revealing lyrics inside and outside the stadium stands most noticeably during gatherings.

Our focus on such songs arises from their being one of the most significant of the Ultras’ modes of collective communication. Terrace chants reflect Ultras’ thoughts, trends, and positions towards life and socio-political reality(ies). Besides, they chronicle the most important events and conflicts witnessed by Ultras youth within the stadiums as well as their attitudes towards such highlights and conflicts.

Content analysis methodology can be identified as a research technique for the objective, systematic and quantitative description. It is: “a research technique for making inferences by systematically and objectively quantifying and describing the obvious communicative content” (Grawitz 1990, p.534). The study of such communicative contents has been conducted through a set of important methodological phases set out below:

1. Collecting a sample of communicative content through the design of a database including most of the songs published by the Ultras Tunisian groups on social media. In this vein, we adopted a two-stage song collection process. In the first phase, a survey on the Ultras active networked interest groups has been conducted both by pursuing them on social media, hence involving the contact of a group of activists to allow for listing the like-minded groups they know and connect to. The second phase mostly focused on developing a consolidated data base of songs and chants compiled from sources comprising primarily official Facebook and related pages. Despite all the efforts undertaken throughout the study period to ensure the comprehensiveness of the Ultras artistic archives collection, there are undoubtedly some musical productions that have eluded us. This might be either because the chants have not been recorded or because they have not been shared in social media or made public in any other way; it could also be due to a shortcoming in the collection approach given the significant dispersal of the chants and the lack of centralized publishing and archiving. There is scope here, in future studies for a better development of such a database to provide a comprehensive archive. Nonetheless, the songs and chants compiled in the database constitute a satisfactory repository from which to gain access to the expressions of Ultras groups, and to allow us to quantify qualitative data and develop in-depth analyses.

2. Selecting and wording of indicative units of meaning for our research question, under which classification of songs’ extracted contents will be undertaken. A pre-defined coding frame was initially identified, then partially amended through listening, and content analysis was carried out as required by the research process. Worthy of note is that our research focus has been inextricably linked to the critique-related contents of a protest dimension.

3. Transcribing the songs and relevant content classification and quantification in consistency with the list of significant units of meaning, as well as qualitative notetaking for each song. A Microsoft Excel spreadsheet has been developed for this process.

4. Quantitative data collection and content analysis consolidation by extracting the rates derived from both the frequency and intensity of the units of meaning, in terms of their change in number and in proportion over four major historical periods, namely the period before 2007, the period spanning 2007 to 2010, the period from 2011to 2016, and the period from 2017 to 2020. Such a process will enable us to weight the numerical and relative meanings in general, then draw the discrepancy with released products at the very specific period. We have used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for these statistical treatments and relied on Microsoft Excel to visualize the results.

Research results

Ultras Groups in Tunisia: Morphology and Geographical Distribution

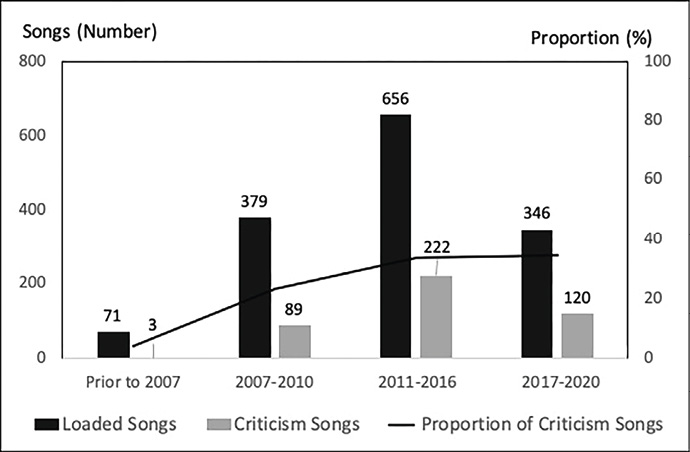

The present research intends to identify, Ultras groups in Tunisia considering the club affiliation (sports team) and geographical distribution, (governorate). Therefore, this strand of work has identified 66 groups belonging to 22 teams, geographically distributed over 16 governorates. Team affiliation seems to be prominently visible in Tunis, the capital, thus grabbing the lion’s share with 20 groups. It is noteworthy that the largest concentration is visibly spread all over the coastline while dropping in number in the inland areas.

As shown in Figure 1, it is quite noticeable that, considering residential densities across the country, the phenomenon of Ultras group formation is omnipresent in more densely populated cities and the urban sprawl marking large cities. Yet, geography and demography alone are not the main factors to interpret the rise of such phenomenon. The history of sports played a role as well, as the origins of Ultras are linked to old sports clubs and teams with a history of over many years. Indeed, in most of the governorates where the phenomenon is marked, clubs are currently or have previously been active within the 1st Pro Football League. Even in cases departing from this perception, Ultras’ emergence has been also associated with other team sports such as basketball and handball.

Figure 1. Distribution of Ultras groups on Tunisian Territory

Source: Data from authors’ collection (2020)

Ultras Chants in Tunisia: Demographics, topics and evolution of criticism dimension

The dataset for this study contains 1452 chants which are distributed over 66 Ultras groups and which can be grouped into three topics. The first topic focuses on the team and the team player support where the song is typically chanted for a specific player in a sign of gratitude. Such was the case of the chant: “Thank you Lassaad” or “Grazie Lassaad” by the Club Africain supporters crowd paying tribute to the former team leader Lassaad Al-Ouertani who was killed in a car crash on January 4th, 2013. The second topic is essentially about chants, considerable as they are, attacking the opposition teams, supporters and belying managers. The third topic is focused on socio-political criticism. More often than not, one chant might embrace all the three topics.

| Frequency | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 434 | 29.9 |

| No | 1018 | 70.1 |

| Total | 1452 | 100,0 |

Source: Data from authors’ collection (2020)

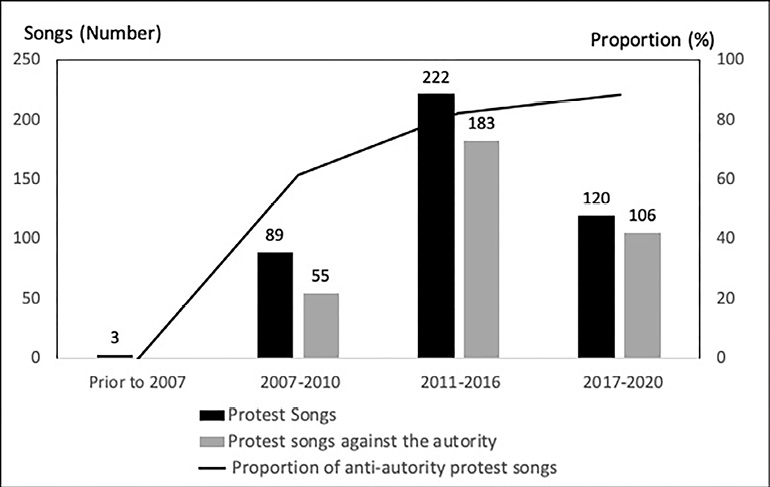

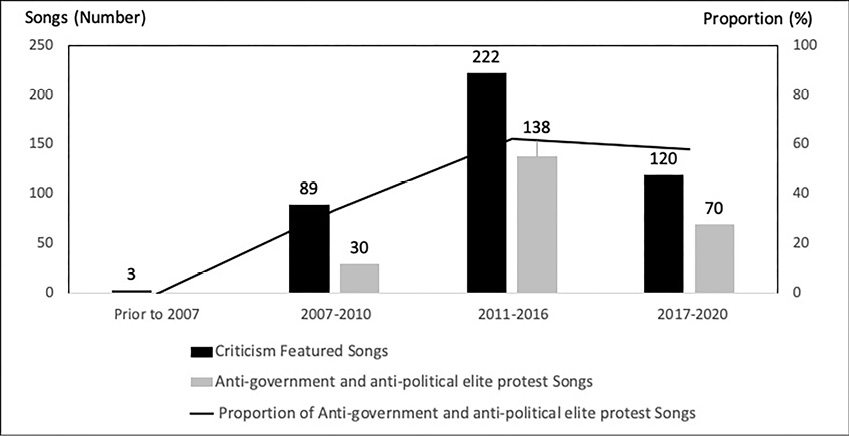

As mentioned earlier, the purpose of this study is to focus on the chants with a critical socio-political dimension. Multifarious messages of disdain and contempt found their way into the lyrics of Ultras’ protest and resistance songs. These target society, institutions and public figures, both political figures and sports ones. These lyrics suggest a protest context or an advocacy context extending beyond the sports competition on the pitch. Reflecting the operational definition, criticism-themed songs account for 30% of the total number of songs produced by football groups in Tunisia. We have noted above that the Ultras phenomenon emerged as far back as 2007, but there seems to be hardly any trace of produced protest songs at that time. Only three (3) protest songs out of 71 which came into fruition at the very same period and prior to such a date (2007) are based on criticism, a rate of less than 5%. These three chants have been produced by “African Winners” groups which have been active within Club Africain Football fans. They address the issue of corruption in the realm of sport, which they specifically claim as the powerful influence and pressure brought to bear by the former president of Espérance Sportive de Tunis (EST) Slim Chiboub, the son-in-law of Zine Al -Abidine Ben Ali, Tunisian President at the time. According to the supporters’ claim, influence was exerted on the referees, on the Tunisian Pro Football League or on the rival clubs. Nonetheless, since 2007, there has been a sustainably significant upward movement to reach its peak since the revolution of 2011, and continuing beyond as is shown in Figure 2

Figure 2. Evolution of Criticism-loaded Songs in Tunisia from 2007 to 2020

Source: Data from authors’ collection (2020)

Protest Songs: Themes, emergence contexts, and evolution

The Contents of Intense politically charged Chants Virages

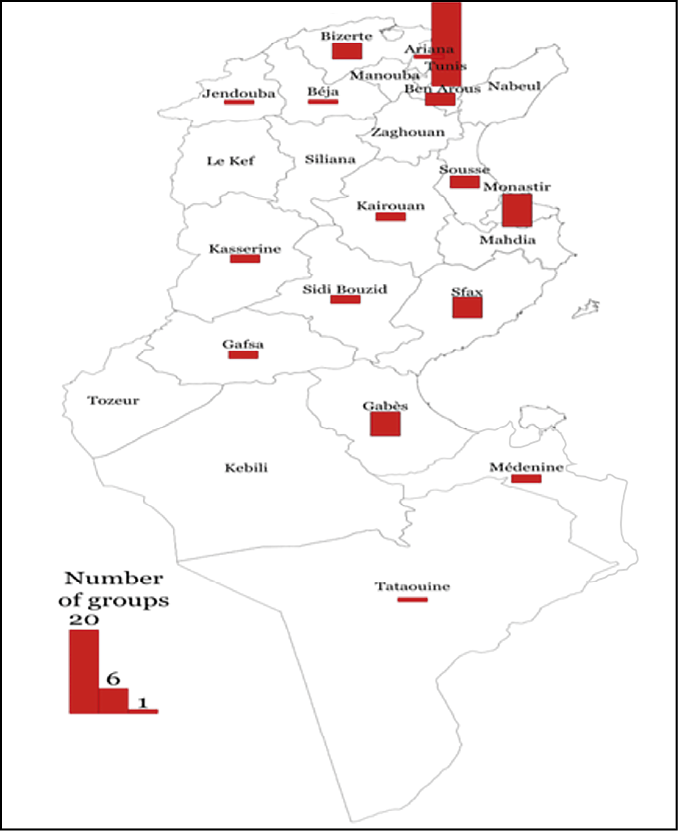

Criticism of the establishment and the ruling system is by far the most prominent theme. By criticism of power we mean criticism of the state, its institutions as well as its administrative elites. Such a theme accounts for 79% of the total number of Ultra chants coded under the dimension of criticism. The phenomenon arose in the 2007 football season to take hold in expressive practices of all Ultras groups without exception across the period spanning 2007-2020. The rate of new chants has increased considerably during the study period, as Figure 3 shows.

Figure 3. Evolution of Anti-authority Protest songs in Tunisia from 2007 to 2020

Source: Data from authors’ collection (2020)

Such a historic phase, during which this phenomenon of criticism has featured on the social landscape; was characterized by a particularly depressed economic and political environment; whereby the sports realm has witnessed upheavals and undergone conflicts. Many messages contain salient details featuring conflict between the president of Espérance Sportive de Tunis, Slim Chiboub, the Tunisian president’s son in law, on the one hand and the members of the Trabelsi family close to Club Africain on the other. Such a dispute which turned into significant power abuse by both parties, fomented the supporters of both clubs, hence fueling a tense atmosphere on the stadium arena and eventually escalating into numerous acts of violence.

The very same period witnessed many socially oriented protest movements across the country. These were reflected in the Mine Basin protests allied with numerous protests movements led by the political elite within the context of the process or preparing to challenge Zine Al-Abidine Ben Ali in the presidential elections due in 2009. In the face of the protest moves the Ben Ali regime became all the more persistent in his attempts to further strengthen his grip on power and impose his authority by restricting freedoms and furthering the excessive use of force.

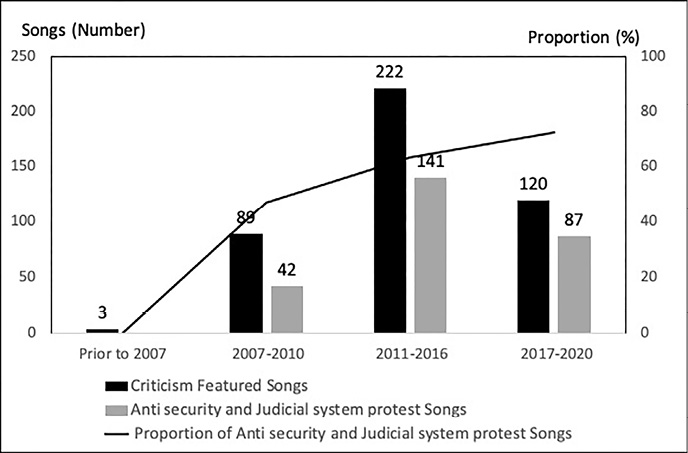

As shown in Figure 2, the repressive wave has an impact on the songs produced during that period. The earliest released Ultras groups chants reflected messages bringing into prominence anti-authority criticism, primarily targeting the police and the Ministry of the Interior, with criticism against the judiciary and the justice system ranking second. Nonetheless, this subsidiary theme on criticism of the security and judicial systems ranks first overall among the most criticism-related thematic issues addressed by Ultras in their chants, with a rate exceeding 62% of the entire protest songs. The evolution of the rates of protest songs challenging both systems reached its peak over the period 2017 - 2020, exceeding 88% of the total musical protest productions which were released during that period.

The backbone of the theme, criticizing the police repression, is evidenced by the frequent use the slogan A.C.A. B4. The theme is embedded in many Ultras chants revealed as a provocative movement in response to their attitude towards what they consider to be the practice of extreme violence by the police. The Ultras relate their exposure to violence starting with the ticketing phase marked by smuggling and corruption in the sale and purchase of tickets in the black market. The police and part of the sporting establishment seemed to be engaged in these corrupt practices. Ultras groups further relate the humiliations they are subject to in queues for ticketing, and during inspection or/and identification procedures before entering the stadium. Referring to the issue of police repression, we have so far noted its salience in numerous chants with the most acclaimed song by Etoile Sportive du Sahel Ultras chanted as follows:

“Handcuffed, they dragged me with nightstick

Beaten and battered to death

Battered, oh my body wholly disabled.”

The issue of repression by the professional police is found in criticism of those who, during the game, are involved in taking photos of supporters for the purpose of arresting those involved in acts of violence, shooting flares or setting off fireworks when the game is over. A significant number of references to professional police have frequently been noted inextricably linked with face-covered supporters using a specific cap known as a balaclava to cover the face. References are also found in a sarcastic and provocative context relating to lyrics contained in many songs encapsulating the slogan:

“I create chaos and don’t care about the football policing unit.”

Figure 4. Evolution of Anti- security and judicial system protest songs in Tunisia from 2007 to 2020.

Source: Data from authors’ collection (2020)

As mentioned earlier, our observations state that the judicial system has by no means been sheltered from the criticism of the Ultras chants as the judiciary is implicated, colluding with security establishment, in trumping up malicious charges. Such is evidenced in protest songs chanted by the fan supporters of Etoile Sportive du Sahel encompassing the following catchy phrase:

“Investigating upon me, With no substantiating evidence. /

Either trumping up a false allegation against me/

or dragging me into drug analysis and testing.”

Such a claim falls within the context of the regime’s persistence in jailing members of Ultras on any pretext. In cases with no evidence, charges related to Indian hemp (marijuana) are the easiest way to sweep up supporters, because of their customary high consumption of alcohol and substance abuse during the game. With a view to eroding the legitimacy of a strongly criticized judicial system, the very same messages are conveyed in another song testifying the sharp protest voiced by Club Athlétique Bizertin supporters:

“Handcuffed, my parents are exhausted by strenuous efforts.

The police knowingly and willfully deceived me/

The judge hit hard against me.”

Criticizing the judicial system is not solely confined to its contribution to trumping up charges but extends, in Ultras’ view, to covering up police crimes. Such a protest theme has been conveyed particularly in the songs responding to the most contentious issue of the mysterious death of Omar Labidi, a Club Africain Supporter. His death on 31st March, 2018 triggered a national jointly launched campaign between civil-society activists and crowds of fans from diverse football clubs. The campaign was entitled “Ettallam Oum” (You should learn to swim) while the judiciary covering up the police crimes are evident in the song entitled “Ye Hayetna” (Oh! Our Life!!) chanted by the Club Africain fan supporters. The lyrics are presented below:

“Oh! Judge! We are seeking truth.

Sick and bored of talking nonsense.

God takes life away. Power constrained

We will eventually die and will accept death-as a decision made by God”

Figure 5. Evolution of Anti-government and anti-political elites’ songs in Tunisia from 2007 to 2020

Source: Data from authors’ collection (2020)

The government and the political elites are another target of the anti-authority songs serving as the second sub-theme and accounting for 54.8% of the total number of criticism songs. While the evolution of the protest songs rate reached its height up to 62.2% in the period spanning over 2011-2016, this rate has shown a slight decline from 2017 - 2020. The drop in the number of chants does not mirror the vehemence of the criticism; the chants and songs present the rise of new rhetoric and concepts of politics and knowledge-based dimension on the part of the state, the system and the elite. This is manifested in the anti-system song “Ya Hayatna” whose lyrics testify:

“the ruling system, we hate you.

You are bereft of mercy.”

Another example comes from the protest song bearing the title “Dynia me Titchef” (A hidden life) chanted by the Club Sfaxien fan supporters featuring the following words:

“pleasurably written words/

one cigarette after the other ignited /

By pen or sword /

a system we take revenge on.”

The songs have moved from mere and transient reference to political corruption and the government’s oppressive measures to songs attributed exclusively to criticism of economic and political elites. Such are manifested These are evident in many songs where the most prominent wording centers on “Ya Hayetna” song of Club Africain fan supporters, “Cortège El Mout” (Death Parade) chanted by Etoile Sportive du Sahel masses, “Bled Ennida” (The Country of Nidaa5) of CAB supporters, and finally in “Koura wou Politick” (Football and Politics) chant performed by Espérance Sportive de Tunis supporters, to name but a few.

Chants virages as a social movement engaged in matters of public interest

Along with criticism related to political corruption and mismanagement broughttargeted at state agencies, opportunism and the scramble for power have been added into the mix, so that compelling examples of messages bearing a political edge and shaking up the status-quo are to be found, an example of which is voiced in the following words:

“You plundered millions looted our country’s wealth /

handed it to foreigners /

You have turned a blind eye and bedded theft.”

Ultras’ chants have been characterized by a high level of engagement in public matters as they have turned to the pulse of major events and momentum witnessed by the socio-political landscape. One of the many instances of compelling songs voicing the sentiment of society over such matters is the chant entitled “Miskina libled” (Oh pitiful is my country!) whose core focus is set on the politically charged campaign “Winou el petrol?” (Where is the petrol?) is reflected in the verse:

“What you did is worth a book/

where is the petrol? Where is the youth share?”.

Moreover, one can note a most prominent reference in the so-called crisis of the neonatal/new-born deaths reflected in “Ya Hayatna” chant whose words are:

“The dear mom got her baby back in a cardboard box”.

The “Ya Hayetna” song further voices concerns on the death of the rural working women in a rollover accident that took place in the district of Essabala, Sidi Bouzid as do lyrics highlighting the bus accident of Amdoun killing 26 youths.

Many of those and other incidents sparked large-scale national popular protest responses. As protests featured a significant pathway into participation in public matters, Ultras have addressed such events demonstrating their engagement in protest movements. Ultras groups who define themselves as prey to injustice and exclusion have duly and very often taken on a high degree of critical visibility towards the political elite, hence holding it responsible. Thus, they can be seen to have performed the chants to speak on behalf of the marginalized and the oppressed. This claim can be made for many Ultras’ chants, most prominently mirrored in the famous Adios Ultras protest song presented by the Jeunesse Sportive de Kairouan (JSK), fan supporters as follows:

“Far away from the game, I am speaking out on behalf of the oppressed.”

Or in the “Ya Hayetna” song in the expressions:

“In the terrace leisure, a place to derive pleasure,

I do what I want/

Do nothing but havoc/ and support without care,

I am the voice of the oppressed and the grieved orphaned.”

Yet, the political elite was not wholly and solely held responsible. Businessmen do not seem to be immune to such criticism. Seeking to dislodge the corrupt businessmen, the references to resisting their corruption, wealth monopoly and misdistribution, allowing for the growth of instances of disparity and inequity; have impregnated the ESS chant “Ya Houkouma Rabbi fil Woujoud” (Oh Government! God exists) stating:

“You will be freed if you enjoy rampant nepotism/

Otherwise when poor, you will spend the night in jail.”

Resistance to prevalent cronyism and ubiquitous corruption is further displayed in “Miskina Bledi” song (Oh My pitiful country) whose lyrics feature the following:

“Bellow your chant, do not even give a damn/

If you have been at the bottom and poor, then you are stepped on, trampled.”

Or again in “Dawlit Ediaaeyet” (The state of rumors) song cheering:

“My wealthy country where the people are denied life/

in your offices you have sold the citizen/

you have made cost of living soaring/

You made us despise this country.”

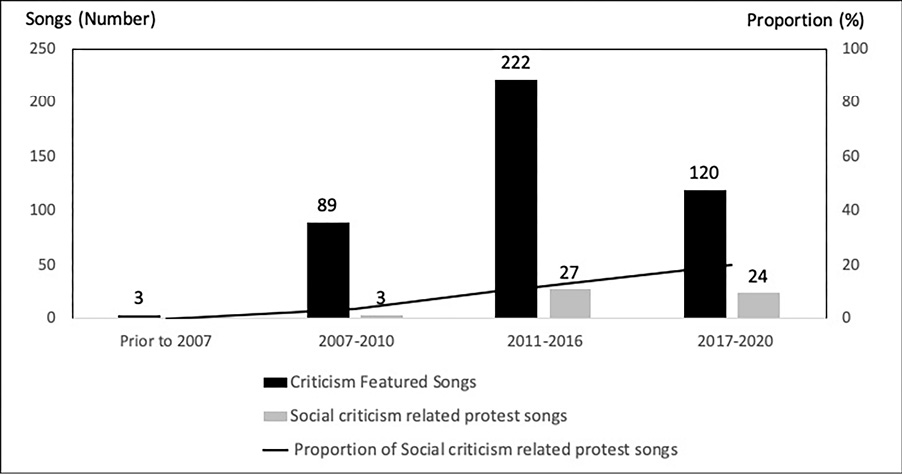

Figure 6. Evolution of Social criticism -related protest songs in Tunisia from 2007 to 2020

Source: Data from authors’ collection (2020)

In this context, more often than ever do such songs serve as a repository of social messages loaded with issues afflicting society and plaguing it in terrorism and criminal phenomena, in drug abuse and in smuggling. Such is vividly mirrored in’ “Ya Hayetna” song:

“You have brought contraband heroine and corrupted the country by wreaking havoc,

You have made people feel more alien and driven them out,

You had them withstand estrangement and alienation,

You have strangled the country,

You have yielded high profits,

And thrown people onto a vessel in a harrowing smuggling journey by sea.”

Continuing in in another vein, the song highlights the people’s grievances pointing out:

“You never know how many neighborhoods are bearing the brunt of marginalization and joblessness /

Vanquished peoples have turned to drugs and alcohol!”

Songs concerned with such issues are 12% of the total socially loaded protest songs, reaching their peak over the period 2017-2020 to attain 20% of the entire songs for that period.

Issues of rejection and protest have been expressed by Ultras groups who have engaged in the usage of revolt and resistance and overt claims for freedom. such calls are found in 51% of the criticism-related songs., As was found in the broader theme, this topic reached its peak over the period 2011-2016, rising to 56.8% of the entire number of Ultras protest songs. The use of freedom is linked to Ultras’ resistance to what they consider oppression by security, aligned with terms denoting freedom claims through the slogan “Libertà per la curva” (Freedom to the Terrace). The message in such a song implies the right of the masses of supporters and groups to freedom of expression of opinion and support for their team in the stadium in their own way, and the ability to do so without police intervention and state imposition of deterrent and severely punishing laws against the supporters. Examples include references to the most notorious “Law -18” which states that: “youth under age 18 are prohibited from entry to the stadium”; the decisions on banning audience attendance, commonly called “Huis Clos”6; or, the 6-month jail sentence on charges of letting off firecrackers in the stands; or again the prohibition against the display or/and entry into the stadium of visual displays such as tifo and banners7 , besides all festive and celebratory symbols invoking the Group’s identity.

Consistent Hostility towards the Security Apparatus

The semantic field Ultras groups use to express the aggravated relationship with the security forces and their oppression mechanisms often draws on the Salafi religious lexicon. A lexical item that has gained ground in the stands qualifies security agencies as “Taghout”8. Quintessentially, “Taghout” references parties espousing an Islamic character. Voicing their grudge at the stands, cheerleaders seem to serve as mediators of and mouthpieces for an Arab-Islamic identity. Such a position is reflected in the EST Ultras chant titled “Virajna Hizboullah”, which translates as “Our terrace is the Party of God), or CA Fandom’s chant whose words indicate the magnitude of the crisis as they perceive it: “Al-Qassam Brigades!! Let’s annihilate the enemy”.

This animosity is consistent with the criticism leveled at political elites who are perceived as enemies of religion and detractors of an assumed Arab-Islamic identity. Another illustration is the religious register populating CAB’s chant that seeks to raise the audience’s awareness of their issues at stake. The lyrics translate as follows:

“Not much has changed, the mentality remains the same/

you are attacking on the true faith/

fighting against religion yet advocating for homosexuality.”

It is estimated that the Ultras groups’ religious lexicon amounts to 9.7% of the total number of protest songs. However, it must be noted that the present section does not limit its purview to criticizing the elites, the authority, and the security forces. Quite the contrary, it blends an array of political messages extending to anti-colonial resistance; most groups taking this approach, particularly those formed during the colonial era, define their institution as an act of resistance to free the country and defend those persecuted for their faith9.

Security apparatuses and political elites constitute the main theme for the Ultras groups’ protest songs. However, other issues and institutions emerge as targets of criticism. Sport’s governing bodies such as the Tunisian Football Federation, the clubs’ managing structures, and sporting officials themselves are not immune from criticism; 14.5% of the total number of protest songs target such bodies. Under this framework, protest songs are vehemently critical of sports and the sports establishment. Several thematic issues reverberate through these songs. One of these is an undertone of detected corruption in the realm of sport in relation to interventions led by politicians and people of power and influence. This is consistent with significant capital influx driven by marketing mechanisms, financial agencies, and advertising businesses. Such dealings were imposed by modern football rules that turned the Tunisian championships into a marketing opportunity for massive profits.

There is room to mention the complicity of the authorities with the sports’ governing bodies to oppress Ultras groups who identify as the last line of defense of sports teams against corruption. In the Ultras groups’ views, the sports establishment have approved deterring legislation and engaged, via the media, in attacking the audiences and framing the Ultras groups as gangsters and terrorists.

The media sector, too, has its share of the criticism aired by Ultras groups. In total, 13.4% of protest songs target this sector. The frequency rate of these songs peaked over the 2007-2010 period, and gradually declined afterwards. Media outlets consistently stigmatized these groups before and after the revolution and characterized them as criminal gangs associated with terrorist Jihadist networks. Ultras cheerleaders firmly reject such characterizations in most of their chants; they perceive these chants as an art form in its own right, performed with artistic and innovative dimensions indicative of their activism. With that, these groups believe there is a cause-effect relationship between the authorities’ oppressive practices and their vocal denunciation of these practices. These groups’ reactions may constitute a departure from and an escalation of their original goal that consisted primarily in cheering their favorite teams and incentivizing players to win.

From Regular criticism and generalized protest to self-discipline

Qualitative content analysis (QCA) suggests that self-criticism is prominent throughout the significant themes despite the low frequency, not amounting to more than 5% of the total number of criticism-oriented songs. By self-discipline songs or parts of songs, we mean those songs whereby Ultras engage in criticism against the practices and behavior of some groups which is considered to veer from’ the Ultras “mentality”: that is, to diverge from the ethical standards governing the conduct of Ultras while committed to affiliating to the group.

Examination of this theme shows that the subjects of this self-criticism fall into four key categories. The first category is dedicated to criticizing some individuals within the Ultras who seek to win the privilege of a seat on the clubs’ governing bodies or who try to politicize groups and facilitate their infiltration by political parties or further by club steering officials themselves. The second category revolves mainly around individuals who are seeking personal recognition so that constructing their sense of joining both the group and the team serves nothing but a financial profit motive or fame or a pathway allowing them to satisfy other personal motivation. The third category addresses criticism of gratuitous violence enacted by some of the Ultras members and which contributes, in their view, to weakening and waning of the movement. The fourth category, however, deals with some group members’ low culture regarding the mentality and its rules, which often spurred on gratuitous bellicose violence and unjustified practices. These are categorically rejected by Ultras because they do not appear in the chants. An example is to be found in the lyrics of “Be Ultras” song10 whose producer we have not identified yet. This is a song through which Ultras have highlighted the rules governing their insights and conduct. In sum, it appears that Ultras groups are keenly interested in completing the frameworks required for elaborating a unifying identity to which individuals may adhere at will. In this sense, these groups model what Michel Maffesoli refers to as post-modern “tribes”. These tribes constitute an autonomous vital social space where members share tastes and emotions and are not prevented from belonging to other social communities in the frame of what he defines as “fragmented identities” (Maffesoli, 2010).

Conclusion

The present paper has attempted to address the phenomenon of Ultras groups in Tunisian society, a phenomenon that has pre-occupied several scholars focusing on Arab issues over the last decade. We have approached this phenomenon from a specific perspective that sets it apart from, from most published literature in the Arab world, both theoretically and methodologically. We have attempted to approach the phenomenon from a sociological presumption that primarily addresses the social criticism development of Ultras group musical productions while bringing up its engagement in the social movements through the production of expressions that embrace a toppling of the legitimate culture. This approachfurther calls into question the shifting of the borders of the social space previously monopolized by political elites and civil society organizations, whether close to power or opposing it.

We have proceeded from the proposition that the extension of the Ultras groups’ circle of influence is indicative of an overthrow of cultural legitimacy standards and the rise of new social actors: actors capable of re-allocating the microphysics of power through their massive politicization of the social pattern that would have been more neutral prior to the 2011 revolution. This has been partially substantiated by our findings that Ultras do not adopt a neutral position, instead imposing their influence as a social mode of criticizing power. We have pointed out that this influence has been brought to bear in various ways since the beginning of the third millennium: by challenging the regime in the chants and songs, and through the bloody confrontations with the security forces within the stands. It has also been reflected as a counterculture spurring the production and release of a set of artistic forms of protest.

This type of counterculture rejects prevalent social values and norms and encourages the emergence of opinions and trends that go so far as to offer alternatives to the dominant culture. Social movements adopt this type of culture as a foundational way of life and turn it into an active force contributing to social change, carving a new a space for expression, and spearheading their aspirations for a better life (Giddens 2001). Further research could consider the extent to which Ultras groups could be considered examples of social movements. An examination of a grassroots Arab counter-culture in this context could provide interesting insights into both Maffesoli’s concept of tribes and Tilly’s theory of social movements.

The approach adopted to address the Ultras phenomenon is informed by the writings of French sociologist Alain Touraine. The aim has been to make sense of the Ultras groups as social actors by placing their struggles in the context of social negotiation with other actors. Based on this approach, the Ultras are treated as rational agents deploying specific strategies and actively preforming actions that are not merely the byproducts of objective conditions beyond their control (Touraine 2002).

Investigation into the proposition proved challenging due to the sizable limitations we have encountered. The lack of a verified list of Ultras groups across Tunisia is significant. This has been intertwined with the absence of unified archival data of their artistic productions, that is, the songs under analysis. We have attempted to overcome these limitations by conducting a two-fold survey attempting, in the first phase, to identify Ultras groups and provide a list, and then explore the archives posted on social media for references to recordings of songs and to eventually collect them in a single database. Such an endeavor allowed for the selection of songs with embedded g criticism content while demonstrating their prevalent highlights in the present paper. We have then presented the most prominent units of meaning while measuring their evolving frequency across the text and exploring a three-phase evolution across the period spanning over 2007-2020.

This study remains exploratory, but its methodological approach can lead to the development of a data base of relevant materials and appropriate research tools, with a view to bundling audio archives of Ultras groups together. Such an undertaking would allow for a further in-depth, substantive and extended analytical approach, delving into the sub-themes of the chants virages.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to Geoffrey Pion (https://geoffreypion.com/) for his invaluable contribution to the design of the map in Figure 1. Special thanks are also due to Oussama Abidi for his invaluable contribution to song collection and tabulation.

References

Aarts, P. & Cavatorta, F. (eds.) 2013, Civil Society in Syria and Iran; Activism in Authoritarian Contexts, Lynne Rienner Publishers, Boulder, CO.

Abde Latif, I. 2019, ‘Balaaghit joumhour kourat el kadam: Tassiss Nadhari wa Midhal tatbiqui’ (The rhetoric of football fans: a theoretical foundation and an applied example), El Omda In Linguistics and Discourse Analysis, no. 6. https://www.asjp.cerist.dz/en/downArticle/485/3/1/74511

Alomari, M. 2019, Political activists or violent fans? Understanding the Moroccan Ultras perspective through social media discourse analysis, Capstone Collection, 3161. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones/3161

Barry, B.1990. ‘Social criticism and political philosophy’, [Review of Interpretation and Social Criticism.; The Company of Critics: Social Criticism and Political Commitment in the Twentieth Century, by M. Walzer], Philosophy & Public Affairs, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 360-373. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2265318.

Bourdieu, P. 1977, Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511812507

Bourdieu, P. 1995, La Distinction: Critique Sociale du Jugement, Cérès Éditions, Tunis.

Chenouda, I. 2016, ‘Al-Altras bayna al-Haraka Al-Ijtimayiia wa tandhim Irhabi Dirassa Istitlaia ala aina min Altras wal Amn wal jamahir bi mouhafadhat al -Kahira al koubra’, (Ultras between social movement and terrorist organization: an exploratory study on a sample of ultras, security and the public in Cairo Governorate), Majallat Bouhoudh Achark Al-Awsat, no. 39, pp. 1-32.

Dorsey, J. 2012, ‘Pitched battles: The role of ultra soccer fans in the Arab Spring’, Mobilization: An International Quarterly, vol. 17, no. 4, pp.411-418. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.17.4.867h607862q165r7

Giddens, A. 2001, Sociology (4th ed.), Polity Press, Cambridge.

Giet, S. 2004, La Légitimité Culturelle en Questions, Presses universitaires de Limoges et du Limousin.

Grawitz, M. 1990, Méthodes des Sciences Sociales, Dalloz, Paris.

Hourcade, N. 2000, ‘L’engagement politique des supporters “ultras” français; Retour sur des idées reçues’, Politix, 2000/2, no. 50, pp.107-125. https://doi.org/10.3406/polix.2000.1089

Maffesoli, M. 2010, Le temps revient : formes élémentaires de la postmodernité. Desclée de Brouwer, Paris.

Numerato, D. 2014, ‘Who says ‘No to Modern Football?’ Italian supporters, reflexivity, and neo-Liberalism’, Journal of Sport and Social Issues, vol. 39, no. 2, pp.120-138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723514530566

Saidani, M. 2018a, ‘Post-revolutionary Tunisian youth art: The effect of contestation on the democratization of art production and consumption’, In Oinas, E. Onodera. H. and Suurpää, L. (eds.), What Politics? Youth and Political Engagement in Africa, Brill, Leiden, pp. 111-122. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004356368_008

Saidani, M. 2018b, ‘An takuna Ultiras yaeni an yakun wujuduk alaijtimaeiu munshaqqan’, (To be Ultras means to have a schismatic social existence), Alfaisal, 1 May 2018, https://www.alfaisalmag.com/?p=10043

Sayed Ahmed, M. 2018, ‘Al’abead al’iqtisadiat walsiyasiat wal’ijtimaeiat li-thahirat al-Ultras fi almujtamae almisrii’, )Social, economic, and political dimensions of the ultras phenomenon in Egyptian society(, Annals of the Faculty of Arts, Ain Shams University, vol. 46, no. 1, pp.260-283. https://aafu.journals.ekb.eg/article_31387_fdd10e1a1637288a32b0b353ba524e16.pdf

Testa, A. 2009, ‘The UltraS: An emerging social movement?”, Review of European Studies,vol.1, no.2, pp. 54-63. https://doi.org/10.5539/res.v1n2p54

Tilly, C. 2004. Social movements, 1768-2004, Paradigm Publishers, Boulder, CO.

Touraine, A. 2002, ‘The importance of social movements’, Social Movement Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 89-95. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742830120118918

Tsai, D. Y. 2020, ‘“A tale of two Croatias”: How club football (soccer) teams produce radical regional divides in Croatia’s national identity’, Nationalities Papers, vol.49, no.1, pp.126-141. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2019.122

Woltering, R. 2013, ‘Unusual suspects: “Ultras” as political actors in the Egyptian revolution’, Arab Studies Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 290-304. https://doi.org/10.13169/arabstudquar.35.3.0290

1 The closest English expression for chants virages is terrace chants, but it is not a complete match, and therefore, the French phrase will be used in this paper. The following is offered by way of explanation: In football stadiums, fans are usually grouped around the curves or bends (virages) in the line of the stadium and each group develops its chants or songs, usually in support of its team; in the English-language context, the phenomenon of team songs or chants is well known, and the place where team supporters’ group together is known as the terraces, hence the phrase terrace chants.

2 The first Ultras Albums and songs have been recorded and publicly released via social media during the Football seasons over 2007-2010. Those mentioned prior to 2007 are old chants most of which were sung and performed in stadiums during the 1990s and the beginning of the 3rd millennium. Examples are chants belonging to the archives of “African Winners” group which undertook the release of its entire musical archives in celebration of the centenary of the Club Africain Club.

3 Considering the “Ye Hayetna” chant, we are referring to millions of views and hundreds of thousands of comments since the first week of its release on social media websites.

4 A.C.A.B. This acronym for All Cops Are Bastards is used by Ultras in English.

5 Nidaa Tounes, the party led by President Beji Caid Essebsi, commander of Essebsi, who led the presidential and legislative elections from 2014 to 2019.

6 "Huis Clos" is a term from French courts of law where proceedings are held 'in camera', that is to say in secret. The President of the court decides that the interested parties and their lawyers are the only ones allowed to attend the debates. But in football, a Huis Clos means a match without an audience.

7 A tifo is a very large banner that is rolled out in the stands before a sports match by ardent supporters (tifosi) in tribute to their favorite team.

8 It is a term often used in Salafi circles and means the person who is oppressive or unjust and who must be resisted.

9 One could note, in this regard, the Palestinian cause as one of the major themes brought up by Ultras chants, representing a source of permanent conflict between Ultras groups and the security agencies, most recently the clash that occurred between the fan supporters of EST and the Egyptian security forces upon the raising of the Palestinian flag in the stadium during the game versus A-Zamalik football team within the context of the first leg of the quarter-final of the African Champions League held in Cairo on 28th February 2020. Such thematic issues have rates ranging from 5% to 5.5% of the total number of protest songs.

10 The song embraces messages related to setting off firecrackers and shooting flares which they perceive as a necessary practice at the crux of the repressive period. They therefore deem it the only tool to draw from the audience the substantial attention necessary to convey their critical messages against power and under oppression, since other forms of expressions in the stadiums, including visual displays such as tifos, banners and canvas, have been banned.