Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 14, No. 1

2022

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

“Sana All”: Netizens’ Perception of Government Responses to COVID-191

Leo Vicentino, Janah Zerina T. Doroteo, Lyn Angel V. Garcia,

Nicole Myem S. De Jesus

De La Salle University Integrated School - Laguna Campus

Corresponding author: Leo Vicentino, De La Salle University Integrated School - Laguna Campus, Laguna Boulevard 4024, Binan City, Philippines, leo.vicentino@dlsu.edu.ph

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v14.i1.7961

Article History: Received 11/11/2021; Revised 20/01/2022; Accepted 11/02/2022; Published 31/03/2022

Abstract

Netizens posted views that contradicted the results released by research agencies about the Philippine government’s responses to COVID-19. In this study, Twitter, which is a key communication channels, was the main source of data to explore the public’s perception of the Philippine government’s performance to the pandemic response. To limit tweets to be studied, sana all, a language phenomenon mostly used at the time of community lockdowns, was observed and utilized as a code identify relevant tweets. Between March and August 2020, 257 tweets were collected and researchers used presuppositions to extract socio-political context and truths implied in tweets. Then, the data underwent a 6-level thematic analysis and eleven categories were formed. The prevalent language intention emerging from the tweets is empathy. This paper will discuss how empathy associates the sound dissatisfaction of the netizens with the responses made by the current administration to combat the COVID-19 multi-effects.

Keywords

Participative Governance; Twitter; Philippines; COVID-19

Introduction

In the first two quarters of 2020, the rapid spread of COVID-19 in the Philippines resulted in local lockdowns and the national government’s Proclamation 922s or State of Public Health Emergency in March 2020. Guidelines in community quarantine, social distancing, closing of establishments, change of learning mode, and prohibition of mass gatherings were put in place to prevent the continuous increase of cases (Ocampo & Yamagishi 2020; Baticulon et al. 2020). With such drastic moves, it became imperative to know the public’s perception about government responses in this health crisis, to measure the trust both the public health leadership and political leadership. Equally, it was essential to uncover the public’s perceptions because this is necessary to achieve democratic participation in governance, and because the public’s experience will provide information or feedback that could help in the development of policies, decisions, and implementation (McFadden et al. 2020).

Existing investigations of the public’s perceptions were conducted by agencies such as Statista Research Department (Statista 2020), Philippine News Agency (PNA) (Gita-Carlos 2020), and Social Weather Stations (SWS) (Marquez 2020). These surveys conducted during months of quarantine showed the majority were ‘highly satisfied’ with the performance of the Philippine government. These studies’ results might have come from research authorities but their limitations should be acknowledged. There have been concerns found from earlier literature regarding the processes of such studies, including the limited focus of analysis of these perceptions from the participants (van der Weerd et al. 2011), selection criteria of participants gathered (Zulkifli et al. 2017), and the development of the instrument used in gathering perceptions (Baticulon et al. 2020). Studies regarding perceptions have revealed the important connection between analyzing citizens’ insights and service development. Maxwell (2019) stated that in perception studies, most significant is the spaces where the researchers assess how the respondents discussed their opinions, for example, evaluating the authority’s or state’s control. Even though these surveys have been shown to be an important source of the public’s perceptions the researchers need to assess carefully the possibility of response bias (Byrnes et al. 2021) since individuals may manifest their perceptual biases (Starbuck & Mezias 1996).

In the exploration of perceptions, there is a set of available data aside from conducting large quantitative studies coming from surveys and interviews —the social media. Criado et al. (2013) explained that social media can be understood as a platform for governments ‘to interact with citizens’, thus establishing this as an area to reveal public opinions. Further, Warren et al. (2014) stated that social media plays an important role in defining citizen involvement and in preparing people to perform community actions. Along with this, Takahashi et al. (2015) proposed that social media have been acknowledged as an essential dissemination tool that can also serve as a communication channel in crises. Thus, this study marks out the data from social media, Twitter, that captures the essence of the study’s framework, which is participative governance, and constructs readily available sources to cross-reference it with the information released from government institutions and media outlets. It is commonly accepted that Twitter has been used as a way for netizens to share views especially in times of crisis, as this social media platform helps in information dissemination (Song & Lee 2015), and serves as prominent role in gathering news, and presenting experiences of the public (Takahashi et al. 2015).

Thus, the objectives of this study are to collect the netizens’ perceptions of the government’s actions through their posted tweets, during the months of strict quarantine. This could elaborate their all-important views on the government actions during the period, and determine if the netizens in Twitter were satisfied as compared to the released results cited above.

Sana all

To limit the tweets to be studied, the phrase sana all was utilized as the code to be generated in the Twitter search engine. Sana all is a unique Filipino expression, which has become very popular in everyday culture. It has two meanings. Traditionally, it has been seen as an expression that calls for equality. More recently, it has been used by Filipinos, especially teenagers and other young people, as a kind of catchphrase to wish for an individual’s good fortune. It is made of two components, sana meaning hope and all referring to everyone and is present in oral and digital communications.

Scholars in linguistics and political science may have associated the concept traditionally with socialist political ideology as the phrase intends equal distribution of wealth and resources across the population. It has also been associated with the Filipino concept of inggit (envy) in a recent undergraduate study from the University of the Philippines-Diliman (Pontanilla 2020), which explored the meanings behind this popular and well-used phrase. The researchers found that other intents aside from being envious can be linked in sana all as its use or meaning has evolved based on the current context. For instance, what the speaker meant when saying sana all may ayuda can be strongly ambiguous. It can mean that you can be envious because you have not received support or that you are disappointed that not everyone has received their support, thus showing concern to others. However, saying sana all may dyowa, where dyowa (also spelled jowa) means lover or girlfriend or boyfriend, the phrase can mean envious because you’re not in a relationship and nothing more.

Presupposition

Having explained the significance and meaning of the key phrase, sana all, it is now appropriate to turn to the way that the data will be analysed. It will be looked at from a pragmatic perspective to determine presuppositions, then form categories and eventually describe the intention of those posting these tweets.

Fillmore and Atkins (1992) stated that in human communication we achieve ‘understanding’ for the knowledge we acquired from previous interactions and exposures, as such our natural capability to presuppose. In addition to this, Simons (2003) described the mind’s capacity to analyse and to understand the whole meaning of an utterance by the process of assuming. Associating the assumptions, Fairclough (1989; 1992 cited in Polyzou 2014) identified presupposition as a type of contextual knowledge observed in our utterance. For Polyzou (2014), every statement consists of an underlying set of truths known as presuppositions. It is an implied ‘background’ —developed from continuous exchanges of information, and actors involved in these systems of discourses are capable of comprehending the overall message. Presuppositions, in simplest forms, are ‘non-overt parts’ of the messages delivered by the sender, and those that are part of the messages’ macrosystems can decode these parts.

This study aims to interpret the messages of the netizens, in which it focuses not only on the surface level but targets to describe the implied contents or socio-political context of the tweets. Yule (1996) identified six types of presupposition: existential, factive, lexical, structural, non-factive, and counterfactual. Of particular concern to us here is the distinction between factive and non-factive verbs. Factive verbs make a commitment to the truth of a statement; examples of factive verbs include note, demonstrate, confirm. The verb ‘sana’, to hope, is non-factive. Examples of non-factive verbs include suggest, assume, imagine, hope. These words do not presuppose a truth but may denotes some form of wish or intention (Nagel 2017 cited in Nazlidou et al. 2018). The presuppositions of an utterance can only be grasped from the context of the utterance itself. Therefore, in this study, taking a pragmatic approach, researchers, will investigate the internal and external arguments near the verb hope inside a phrase or sentence —to determine the netizens’ intention.

Concept of Empathy

Finally, given the potential ambiguity in tweets using the phrase sana all, it is relevant to consider the concept of empathy as a way of clarifying this potential ambiguity. Barker (2003) explained empathy as a process when people can perceive, understand, experience, and respond to the ideas and emotions of another individual. It is also when an individual involves, connects, and relates themselves to other people’s situations, feelings, or experiences. Segal (2011) stated that empathy is present when an individual receives the perceived realities of other people after understanding their experiences and sufferings. In addition to this, Decety and Yoder (2016) argued that a person is being empathic when they show great concern for the importance of other people’s well-being. As a result, individuals who show more empathy are those who are most likely to act and help those who are in need and suffering. Empathy can also make an individual feel other people’s suffering and their emotions by letting themselves have sympathy and concern towards other people (Clifford et al. 2019). By resonating with these emotions, individuals are most likely to relate with other people. Moreover, empathy was defined by Chen et al. (2020) as a characteristic in which a person recognizes other people’s emotions and feelings by letting themselves experience their sentiments. With this, an individual showcases empathy when he or she has the ability to understand and care for other people. Empathy is about how individuals connect with others’ experiences by perceiving their emotions and experiencing their suffering. It is how they prove to others that they understand their situation and the sufferings that they are experiencing. In this study, the researchers observed that the netizens are vocal on social media and this platform is a way for them to share their perceptions about the situation of others, and themselves. In these actions performed by the netizens, the researchers have assumed that it is empathy that leads them to post tweets.

Conceptual Framework

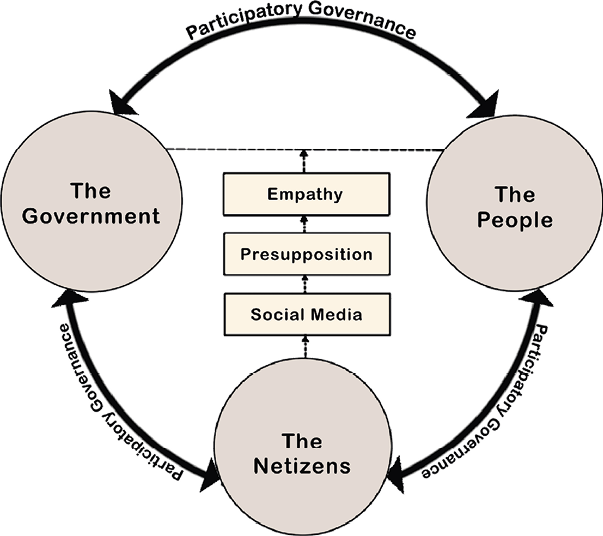

Figure 1. Government, People, and Netizens in Participatory Governance

The study follows the framework of the growing body of work in participatory governance (Gustafson & Hertting 2016). The figure above shows three important actors working for particular actions to attain the goals of the community: (1) the government, being the authority known to be taking the initiative as their main role is to design programs for development and crisis management, and (2) the people and (3) the netizens, as the key important player in the process of participation. Gustafson and Hertting (2016) in the same paper enumerated the motives of participants in calls for community actions: (a) common good motives, (b) self-interest motives, and (c) professional competence motives. The first calls for the authentic improvement of their neighbourhood, the second calls for promotion of one’s group or family’s interest, and the last calls for less political focus on the interest-driven by professional life. As such, this study observes the emerging motives or intention of netizens on the tweets they post on Twitter concerning the context of this research. Previous literature described and identified the roles netizens have taken in terms of ensuring effective governance to crises, people, and related contexts. Aizu (2004) noted that in netizen participation in internet governance, netizens become watchdogs, becoming the provider of checks and balances in the complex system. These actors, the government, people, and netizens, when heavily involved can perform the promise of ‘integration’ as netizens here are not necessarily just receivers of orders or representatives, but part of the system to enhance the government processes of policy creation, and this encourages dialogue between mentioned participants that could practice the idea of innovative democracy (Smith 2009; Warren 2009). Social media, particularly in this period, has become the tool to exhibit involvement in political discourses as observed which is beneficial, as it can increase interest in politics (knowledge and empowerment) among individuals and can increase representation to marginalized groups. This can establish efficiency and exert appropriate force coming from the netizens for the authorities involved in the government to give quality service to the people. On the other hand, Hajer (2003) and Cornwall (2008) described the vagueness of the participatory governance process, in particular, on how to perform participation or integrate this concept into practice. Figure 1 captures the participation process that happens when actors play their multifunctional roles in the system. As active contributors to governance, these actors are not merely recipients of information but are equal sources of actions and initiatives as this framework shows.

Methodology

The goal of this descriptive research study is to look closely use of sana all, a current phenomenon in the Filipino language and investigate its socio-political context. The appearance of Sana all, observed to be present anywhere in oral and social media discourses most especially at the time of the community lockdown, was used as the main criterion in determining the data to be collected from the social media platform —Twitter. Known as the most popular social media and a microblogging website, Agarwal and Sureka (2017) named Twitter as a space where people on the internet strongly share their feedback about governance. Descriptions of the context in which sana all is used, identification of the intention of netizens’ usage are the expected results. In this social media research study of public perceptions, sana all was used as a code to be generated in the Twitter search engine. Other related codes frequently appeared in the search engine such as sana ol, covid-free, DDS, gobyerno, academic freeze, Vico, administrasyon, and quarantine and these were purposely selected to limit the total number of tweets and assured that tweets collected were connected to the period’s dominant social context. Tweets in Filipino and English tweet were collected. The researchers arranged and stored the collected tweets in a Google Drive folder arranged by month. Then, researchers used Google Sheets for managing the tweets to their assigned groups and extracted presuppositions to form categories. Researchers set month-long synchronous sessions to agree on tweet’s presuppositions. Before the stages of analysis of data using presuppositions and thematic analysis strategy started, the researchers read related current event articles from various local media and government agencies as input for contextual immersion to the collected tweets. The six-level thematic analysis strategies proposed by Braun and Clarke (2012) were utilized strictly. Afterward, researchers looked closely at the intention of the netizens in these presuppositions and match supporting literature —forming a checklist to cross-examine and explain the observed motives through online discussions.

Results

From March to August 2020, 257 sana all tweets on the first phases of the strict implementation of Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) were collected. The initial stages of the analysis have purposely grouped each collected tweet based on the observed surface content commonalities: (1) COVID-19 experiences, (2) Mayor Isko Moreno & Manila, (3) Mayor Vico Sotto & Pasig City, (4) Ayuda, (5) Education, (6) National/Local Government of the Philippines, (7) Inequality in the Philippines, (8) About the Law, (9) President Rodrigo Duterte, (10) Vice President Leni Robredo, and (11) other places/countries’ situation and government. Then presuppositions for each tweet were extracted following the group arrangement. This example statement shows how researchers elicit presuppositions: Maria hopes to eat sinigang for her lunch. This statement presupposes that (A) Maria does not have sinigang, and (B) Maria asks sinigang for lunch. The researchers found some presuppositions that were similar within the group and others that were distinct. So to arrange these, those with similarities were used to form categories and those that varied within the group were combined with the matching presuppositions from the other groups. As a result, a total of eleven categories was formed from the 809 presuppositions identified in 257 tweets, as shown in the table below.

The majority of the presuppositions, 59.46%, were about opinions of the Duterte administration. This largest category is concerned with knowledge of the public about good governance, effects on employment, local health care system, and militarization as the government’s solutions. Netizens showed they were keeping an eye on exposed societal issues this lockdown through their engagement in social media. Social inequalities experienced by citizens and their neighbours contributed 8.78%. Lack of purchasing power due to increasing unemployment, inefficient and unequal systems of support distribution, inconsistent conditions for contractual employment were their arguments on how problems caused by their socio-economic disposition affected their lives. Views of netizens on evidence-based policies accounted for 8.41%. Here, they called for effective international standards to contain COVID-19 and they also pointed out unnecessary elements in the systems of implementation such as biased guidelines. Opposing perspectives on the government’s actions were proposed by 6.67%. They expressed their appraisal or criticisms, their belief and disbeliefs, and agreement or disagreements towards the government and these revealed their different political biases. Impacts on ordinary citizens —on livelihood, mental health, and lack of employment alternatives – were evident in 4.57%, while 4.33% expressed events they desired to happen. In the immediate aftermath of the lockdown, a number of Filipinos were distraught by the prospect of having an inadequate quality of life during this pandemic, leading them to change their life aspirations. Support to the most vulnerable as a focus for 2.72%. Netizens expressed their disappointments on how the frontlines staff were treated, the vaccine availability, and unobtained benefits; they reflected on wow the government failed to deliver for the most affected, demonstrating inequalities in assistance and how some officials focused on the economy instead of on public health. Performing good citizenship was a concern for 2.47%. They criticized those who did not follow the measures, and they expressed the importance of these guidelines to their life. A small proportion, 1.36%, commended of the actions of front lines and civilian volunteers. Filipino discipline compared with that of other countries was judged too, while a somewhat smaller proportion, 0.99%, pointed out the public’s declining trust. Netizens aired their frustration and doubted the government’s intention. Finally, with a focus on understanding resilience. 0.25% were grateful that their family was surviving, in spite of facing huge financial difficulties, a mentality that some saw as toxic.

Opinions on Current Governance

Epstein in his On the Importance of Public Opinion (2012) emphasized that people have an essential role in constructing important public policies. Netizens have an array of knowledge and criteria for good governance as the data shows. They demanded that the government must perform appropriate actions in crisis, must be competent authorities, must be transparent to the public, and must be science-oriented and evidence-based in policy creation and decision making. Data shows that netizens commented on several local governments (LGU) including the cities of Manila and Pasig, both in Metro Manila, as being responsive to the needs of locals and they identified these LGU’s as being of greater help to them than the Duterte government. They even shared how other countries had battled the COVID-19 pandemic successfully compared to the Philippines. An example of this is a tweet from a netizen that stated (1) some countries have a lower ratio of death cases regarding the pandemic, and (2) the netizen is hoping for everyone to be like other countries situation. Aside from calling for effective governance, the public demanded solutions to the lack of job opportunities, problems with public transport, and support for employees under the ‘no work, no pay’ scheme. They were highly critical of militarization as the government’s priority to problems related to policy implementation nationwide. Netizens positioned their disappointment on how the government abused its power to control the citizens during these times. One position expressed was that that (1) the military is not needed to solve COVID-19 cases in the Philippines just like other countries, and (2) the military has been present and used by the government but still, more people are infected by the virus.

Observed Social Inequalities

The long-term effects to the poor of a globalizing world will last unless initiatives such as institutions work collectively on how to effectively equalize the distribution of wealth. As such, a small fraction of the world’s population will continue to dominate the economy while the rest will remain as they are in the next long years (Scheffer et al. 2017). It is at this time where we can most observe its effect and an example is the welfare of poorer students that is greatly affected in netizens’ view. A netizen stated that only those who are privileged are the ones who can afford the online setup. They also lamented the plight of students who have extra burdens to support their families as their parents experienced the loss of jobs due to lockdown. In addition, some netizens mentioned that not all have a support system or resources to buy their essential needs in this situation, they questioned where they would find capacity to purchasing their class equipment or resources, and others asked the government to provide support for student’s daily necessities. The anger of the netizens was also directed to government officials as citizens in all walks of life do not receive the fair support that they need, and not everyone receives help from the government as the government had indicated. They said that (1) the government’s plans and actions are insufficient and not for all, (2) vulnerable citizens do not have access to assistance, and some citizens (3) need more urgent support from the government. They viewed the distribution of resources as unequal, one particular example they presented is the ayuda, that is, government-provided emergency welfare support. Some local government units distributed goods and resources unfairly which supporting their point that there are people who have the upper hand because of their connections to the government. These netizens demanded that every citizen should receive fair assistance from the government, whether they are registered voters, middle class, have overseas worker families, or not.

Comments on National Policies

Böcher (2016) explained that political actors should utilize scientific knowledge and integrate it into their actions to find community-based and inclusive solutions. Several netizens expressed their criticisms and disagreement towards the government’s policies in combatting the pandemic, particularly with the effects and impact of this to people: limited face-to-face contact, wearing of face masks or shields, and designated community quarantines. Some netizens have stated that these policies were insufficient, and others lacked scientific support since the COVID-19 cases were still high in the country; several citizens chose to violate the government’s policies for humanitarian reasons. The netizens compared the actions of the Philippines with the neighbouring countries by measuring the difference in terms of COVID-19 cases and how their governments handled the height in their place. Comparing the Philippines and the government’s performance during the pandemic to these countries with successful implementations is a way for them to see the shortcomings of the Philippines in handling the crisis. Therefore, netizens demanded that the government work out what they should adopt from other countries’ practices. Here are some words from netizens: (1) Thailand does have minimum COVID-19 cases, (2) the COVID-19 situation in South Korea is well-handled by their government, and (3) COVID-19 free countries due to the early implementations of the safety protocols of their governments like New Zealand.

Polarized Political Positions

A recent study of the University of Wyoming and five more US universities found that the welfare of people in important aspects such as finances, health, relationships, and societal interest are affected most due to the increasing political polarization of a country (Weber et al. 2021). Netizens were highly involved, what some would call blind fanaticism, in the activities of the two highest elected public positions: President and Vice President, who are currently leaders of the majority and opposition respectively. Netizens monitored the actions of these political heroes through consistent appraisals to commendable actions and giving their harsh criticisms on observed negligence or lack of action. The majority of the tweets said that actions from VP Maria Leonor G. Robredo are remarkable compared to those of the president. They expressed admiration towards the VP because of her works and contributions during this time. She was able to raise 61 million pesos worth of donations (about US$1.12m) from different private sectors. She was praised for her people-oriented actions, different from other officials. On the other hand, several netizens expressed the view that they cannot trust and benefit from the Duterte administration. The netizens showed their disappointment and disbelief towards the administration since according to them, the administration only prioritized and gave full attention to ‘non-urgent’ matters. They decried the actions and decisions President Duterte had made as for them not helpful ‘for all’. They appealed for smarter policies and better plans to properly manage the ongoing crisis. Yet, there were still those who expressed strong support for the administration. Noting the opening cited study, we can imagine that netizens can create ‘specific-shared reality groups’ that only accept what seems to be ‘acceptable’ for them, which can eventually be ‘harmful’.

The Impact of the Pandemic on Ordinary People’s General Aspirations

The pandemic has greatly affected the economic aspect of the country, and this has been clearly exposed due to the unemployment situation of many citizens. A netizen said that (1) Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) cannot send remittances to their families here in the Philippines, (2) a lot of the citizens lost their jobs, and (3) they are wishing to still provide or buy things for their needs. Also, the pandemic brought a lot of issues in the society besides economics. It had a significant affect on the well-being of Filipinos, not only those who tested positive, but also the mental health of the general public. Netizens also expressed even those not directly affected cannot work since there are fewer employment opportunities, and this led to them voicing how they experienced hunger, with no available sources of income and non-existent savings. As they desire to let the Philippines get back to normal, they tend to compare the Philippines’ situation to neighbouring countries, to be one of the privileged people who experienced great service, and to hope for a competent government that is deeply concerned for its citizens and capable to prevent the continuous heights of cases.

Exhibiting Good Citizenship and Supporting the Most Vulnerable

As the government implemented safety protocols to prevent uncontrollable transmissions of the virus, more citizens violated these measures, particularly social and physical distancing, proper wearing of face masks & shields, and individuals who are vulnerable to the disease having outdoor activities, according to concerned netizens. Although some people disobeyed the directives, others chose to follow them and dealt with the ‘stay at home’ protocol rather than risk contracting a far more deadly disease. The netizens expressed their reminders to individuals who violated the safety measures including the liquor ban, set curfew hours, and the rest of the measures. They also demanded from their fellow citizens active participation and intentional dialogue with officials so everyone is engaged in actions against COVID-19 (US AID 2008). A netizen elaborated an opinion about Filipino discipline compared with other countries, saying that (1) other countries have disciplined citizens, and (2) other countries have a good policy system compared to the Philippines as their people would agree. The netizens in general also emphasized the dependence of the concerned public on future vaccine distribution, they requested the government to prioritize the frontlines staff and even to consider the most vulnerable groups such as the homeless, the senior citizens, and the likes.

Public Trust and Resilience

Government officials are assigned to initiate immediate actions on crises and perform duties as leaders. They are responsible for the safety and welfare of the citizens (Paydos 2020). As netizens showed awareness of this, they hoped they would act accordingly especially in this important time. From their perspective, netizens questioned the capacity of these leaders as doubts on their tweets were overtly expressed. A netizen wrote that (1) the citizens may have lost their hope on how the Philippines will battle against the pandemic, (2) the citizens are not hoping that the government will solve the problem anymore, and (3) the complaint and supplication of some citizens are not being heard and taken care of. Netizens have shared opposing opinions also on resilience as there are still people who display clueless positivity in this time of pandemic, even though the situation is worse, and there are on another side whose who are thankful for their families who are still capable of providing their necessities. Filipino resilience, according to Libot (2020), should not be praised or admired. Rather, the public should expect the people in the government to be held responsible for building a better system to lessen the suffering of the Filipinos who experience catastrophic events. It is understandable for people to be delighted that some of the citizens were able to recover. Nevertheless, the thought of having an almost unheard of portion of the country unemployed indicates that worse things could have happened and this may lead to the result that there is an underlying problem that transcends beyond the pandemic (Marquez et al. 2020).

Netizens’ Sana All Intent: To Empathize

All categories discussed in the previous section lead to one overarching intention of the netizens as observed in the tweets and their presuppositions —empathy. To cross-examine the connection of netizens’ sana all tweets to empathy, researchers made a comprehensive compilation of literature regarding the concept, creating a checklist of scholarly works featured here. The concept of empathy from various scholars cited in this section was determined through systems of discussions by researchers and in this, they gauged these to be appropriate descriptions to the presuppositions, and these explained the ‘reality perception’ and ‘intention’ of the netizens in their tweets. As researchers looked at the intention while presenting appropriate discussions to support the observation, this section presents appropriately selected tweets then explains the main argument of this study, that these groups of netizens when tweeting sana all in this context intend empathy. All tables are named after the context of each tweet as perceived by the researchers. In the table the contextual translation of the tweet, the presupposition, the perception, and the observed attitude —empathy – are all presented.

| TWEET | Sana all mayaman (I hope everyone is rich) |

| PRESUPPOSITION | People are not capable enough to purchase goods. |

| PERCEPTION | Economically poor will not survive in this crisis. |

| INTENT | Puts themselves in other’s shoes (Chen et al. 2020) |

Assuming the internal drive of the one who tweeted shown in Table 2, the researchers looked at the situation of ‘the world’’ of people from the selected tweet not having the power to purchase their essential needs at this time of community lockdown. The researchers viewed it as an articulation of a person’s reflection to themselves or from the presence of ‘all’, it can be the netizen putting themselves in ‘other people’s shoes’ and relating themselves in the situation of their neighbour (Chen et al. 2020). From the pointed root of intention comes this post ‘sana all mayaman’, which presupposes that the one who tweeted here wants or hopes everyone to become rich. With Sana or hope being a non-factive verb, the receiver of the tweet will believe that the netizen perceives that the people whom they observed may not be capable of surviving this pandemic. The researchers would need to carry out further investigations to conclude the person’s socio-economic status, remembering the two possible interpretations of the use of sana. There is a possibility of the netizen not being rich or it can also be a reflection of the netizen’s view and observation as stated. As a contention, the empathic traces observed from the tweet as explained, drive the motive to post the tweet sana all mayaman.

| TWEET | kainggit talaga ibang bansa. literal na sana all (I envy other countries, I hope everyone.) |

| PRESUPPOSITION | Some countries handle the pandemic well. |

| PERCEPTION | People need the government as they battle against the pandemic. |

| INTENT | Identifies and experiences other people’s emotions and feelings (Chen et al. 2020) |

Table 3 shows that the netizen expressed in the tweet how envious they feel of countries other than the Philippines who handled the pandemic excellently. The tweet presupposed countries ‘exist’ that have handled the pandemic well. Identifying that there are also countries that do not handle the situation well, this tweet can be evidence of a call for help so the country can still survive. This shows how this netizen identified and experienced other people’s emotions and feelings which are seen as empathy (Chen et al. 2020). The netizen saw that the citizens needed help and assistance from a competent government like how effective the actions of leaders in other countries were.

| TWEET | Sana all equipped (I hope everyone is equipped) |

| PRESUPPOSITION | Students are not equipped to continue learning in the setup. |

| PERCEPTION | Students have limited capacity for participating in online classes. |

| INTENT | Understands people by perceiving or experiencing their life situations, gaining insight into structural inequalities and disparities (Segal 2011) |

The tweet shown in Table 4 highlights students who are not prepared for the new education setup which is online distance learning (Baticulon et al 2020). The netizen points out the advantage of privileged students as they were capable and had the means for this type of learning. The researchers observed that the person who tweeted this may show understanding of other students’ situation by perceiving or experiencing a similar situation as they have insights of inequalities and disparities of their neighbour (Segal 2011). The intention resulted to post ‘sana all equipped’ hoping that the underprivileged students they observed would be helped by the government to become equipped and prepared for online education.

| TWEET | sana all privileged (I hope everyone is privileged.) |

| PRESUPPOSITION | There are those privileged and not during this pandemic. |

| PERCEPTION | Citizens are not just holding the government accountable for themselves, but also for the people who do not have enough resources to survive this crisis. |

| INTENT | Feels responsible and needs to be involved (Barker 2003) |

As shown in Table 5, the researchers observed that the tweet is exposing the socio-economic disadvantages of an individual during this period. People who are privileged and underprivileged exist and this discrepancy became more prevalent this time. The researchers saw traces of empathy as the netizen may feel responsible and involved in the situation of the disadvantaged (Barker 2003). However, this tweet cannot directly conclude the status of the netizen. If this netizen bears the hardships of the underprivileged, it can be viewed that they are holding the government accountable for people who are not capable of sustaining themselves as they do not have the resources to live during this crisis.

| TWEET | Sana all...lalo na yung ating mga government leaders. (I hope everyone especially our government officials.) |

| PRESUPPOSITION | There is no government to lead during the crisis. |

| PERCEPTION | Individuals are doing their best to help fellow citizens in need. |

| INTENT | Can help to react to another individual suffering with feelings of sympathy and compassion (Clifford et al. 2019) |

In the context of extending help to those people in need during these times, the netizens knew that there is a government to lead during the pandemic. Supposing that there are also citizens who do not receive help from the government, other people reacted to their sufferings with feelings of sympathy and compassion, called empathy (Clifford et al. 2019). The netizen was hoping for people in power, especially the government officials, to act and help everyone in need; this tweet presented in Table 6 expresses the sentiment that ordinary individuals are doing their best to help their fellow citizens.

Conclusion

Research agencies’ reports of high satisfaction rating resulting from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic during the first period of ECQ are contradicted by an overwhelming majority of the netizens’ feedback from the sana all tweets collected from March to August 2020. The pre-lockdown survey results produced last February 2020 by Statista Research Department (SRD) viewed the government as ‘had acted appropriately’ in handling the outbreak with the majority of 69% and only 23% viewing the government as ‘not acted sufficiently’. The results released by Gallup International Association (GIA) said the Duterte administration impressed 80% of Filipinos receiving a satisfaction rating from the response to the health crisis in April 2020 and only 18% were dissatisfied. And from the September 2020 survey of the Social Weather Stations (SWS), the majority answered that the government response was ‘adequate’ in three over four pertinent areas that concern pandemic: inform the public on how to fight COVID-19 (71%), conduct extensive contact tracing (67%), affordable COVID-19 testing (54%) and government’s aid to displaced workers (44%).

The result of this current study showed different views over the results released by the cited research agencies. Numerous determining factors could have affected the contradictions in the findings of the studies mentioned. One is the design —this study uses data from social media, the others utilized online survey methods and one had integrated computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI). The data resource was the biggest factor in the significant difference of these perception studies. SRD selected 4,111 respondents, GIA has interviewed 867 Filipinos aged 18+, and 1,249 respondents aged 18+ from the SWS survey. To create extended propositions, a fair investigation should be made to determine in the next studies the practice of principles of these institutions in designing the selection of respondents. The time element when the study was conducted cannot be seen to be a factor as the three agencies’ results consistently evaluated government performance as satisfactory from February to September 2020 and the dissatisfaction of netizens in this study’s data was clearly demonstrated. Varieties of the respondents’ background in these studies such as locality, gender, age, socio-economic status, and others like different communication contexts could be the determining factors of the distinctions presented. However, perhaps the strongest factor lies in the contrast between the nature of the data, strategically designed surveys or interviews compared with naturally occurring posts in social media. We could also not remove factors that are unseen, such as bias and interest, and we do not know how many people posted tweets, only the number of tweets posted using this phrase or a closely related one. Whatever the projected effect of these identified factors on the recent findings, this cannot decrease the relevance of this study’s results.

To maximize people’s participation in community actions and to have access to appropriate sources to be taken into account in the government’s decision-making, netizens’ feedback should always be considered in the policy development process. Social media platforms such as Twitter are becoming essential especially during this time of crisis (Takahashi et al. 2015). It is a mechanism for posting information, specifically the different complaints of the people about services, and the government should respond to these and think about how they can provide responsible actions and connections to the public (Agarwal and Sureka 2017). Overall, Twitter has become a channel for information exchanges where anyone can display their perceptions of realities, and when their ulterior motives when posting are critically examined, different traces were identified and one found in this study is netizens’ empathy towards people, a factor which is important in societal cohesion.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to express their sincerest gratitude towards De La Salle University Integrated School for giving them the maximum support for this research opportunity. They are grateful to Miss Myrla De Luna-Torres, Miss Liezl Rillera-Astudillo, the late Mr. Rembrandt P. Santos, and Mr. Raymund G. Endriga for their assistance and moral support. They would also like to give their sincere appreciation to their research mentor, Mr. Janeson M. Miranda, and Mr. Jeyson T. Taeza. They also thank Mr. Christian M. Lacza, Miss April Rose C. Gonzales, Mr. Dastin M. Tabajunda, and Mr. Jairus A. Fernando for sharing their time and expertise to improve the paper. Importantly, they would like to thank their peers and families who gave their utmost support and motivation throughout their research journey: my love and gratitude to my mom, Norma Vicentino; my parents, Rosario T. Doroteo and Aldrin R. Doroteo for their endless support, love, and encouragement for this project; my parents, Lisa Garcia and Rolando Garcia for their unending support and love; my parents Meldy De Jesus and Jonathan De Jesus for their utmost support. Finally, they acknowledge the constructive criticism of the anonymous reviewers, whose comments have significantly strengthened this paper.

References

Agarwal, S. & Sureka, A. 2017, ‘Investigating the role of Twitter in e-governance by extracting information on citizen complaints and grievances reports’, Big Data Analytics, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference, BDA 2017, Hyderabad, India, December 12-15, 2017, pp. 300-310. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72413-3_21

Aizu, I. 2004, Netizen Participation in Internet Governance, ITU Workshop on Internet Governance, Geneva, 27 February 2004. https://www.itu.int/osg/spu/forum/intgov04/contributions/izumi-contribution.pdf

Barker, R. L. 2003, The Social Work Dictionary, National Association of Social Workers, Washington, DC

Baticulon, R. E., Alberto, N. R. I., Baron, M. B. C., Mabulay, R. E. C., Rizada, L. G. T., Sy, J. J., Tiu, C. J. S., Clarion, C. A. & Reyes, J. C. B. 2020, ‘Barriers to online learning in the time of COVID-19: A national survey of medical students in the Philippines’, Medical Science Educator, vol. 31, no.2, pp. 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.16.20155747

Böcher, M. 2016, ‘How does science-based policy advice matter in policymaking? The RIU model as a framework for analyzing and explaining processes of scientific knowledge transfer’, Forest Policy and Economics, vol. 68 (C), pp. 65-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2016.04.001

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2012, ‘Thematic analysis’, APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. Vol. 2, pp. 57-71. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

Byrnes, Y. M., Civantos, A. M., Go, B. C., McWilliams, T. L. & Rajasekaran, K. 2021, ‘Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical student career perceptions: a national survey study’, Medical Education Online, vol 25, no.1, article number 1798088. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2020.1798088

Chen, L., Wang, Y., Yang, H., & Sun, X. 2020, ‘Emotional warmth and cyberbullying perpetration attitudes in college students: Mediation of trait gratitude and empathy’. Plos One, vol. 15, no.7, e0235477. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235477

Clifford, S., Kirkland, J. H., & Simas, E. N. 2019, ‘How dispositional empathy influences political ambition’, Journal of Politics, vol. 81, no. 3, pp. 1043-1056. https://doi.org/10.1086/703381

Cornwall, A. 2008, ‘Unpacking “participation”: Models, meanings and practices’, Community Development Journal, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsn010

Criado, J. I., Sandoval-Almazan, R. & Gil-Garcia, J. R. 2013, ‘Government innovation through social media’, Government Information Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 319-326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.10.003

Decety, J. & Yoder, K. J. 2016, ‘Empathy and motivation for justice: Cognitive empathy and concern, but not emotional empathy, predict sensitivity to injustice for others’, Social Neuroscience, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2015.1029593

Epstein, L. 2012, ‘On the importance of public opinion’, Daedalus: Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 141, no. 4, pp. 5-8. https://www.amacad.org/sites/default/files/daedalus/downloads/Fa2012_On-Public-Opinion.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00169

Fillmore, C. J. & Atkins, B. T. 1992, ‘Toward a frame-based lexicon: The semantics of RISK and its neighbors’. In Lehrer, A. & Kittay, E. (Eds.), Frames, Fields and Contrasts: New Essays in Semantic and Lexical Organization, Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 75-102. http://www.icsi.berkeley.edu/pubs/ai/towarda92.pdf

Gita-Carlos, R. A. 2020, ‘80% of Filipinos satisfied with gov’t response to Covid-19: poll’, Philippine News Agency, 23 April 2020. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1100714

Gustafson, P. & Hertting, N. 2016, ‘Understanding participatory governance: An analysis of participants’ motives for participation’, American Review of Public Administration, vol. 47, no. 5, pp. 538-549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074015626298

Hajer, M. 2003, ‘Policy without polity? Policy analysis and the institutional void’, Policy Science, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 175-195. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024834510939

Libot, J. 2020, ‘As Filipino resilience gets exploited, netizens slam gov’t disaster response’, Rappler, 12 November 2020. https://www.rappler.com/moveph/filipino-resiliency-exploited-netizens-slam-disaster-response-government-uselessph

Marquez, C. 2020, ‘SWS: Majority of Filipinos say gov’t response to COVID-19 was “adequate”’, Inquirer.net, 17 October 2020. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1349244/sws-majority-of-filipinos-say-govt-response-to-covid-19-was-adequate

Marquez, P., Hermano, J. & Tablada, A. J. 2020, ‘Breaking the silence of resilience’, Makesense.org. https://philippines.makesense.org/2020/10/07/breaking-the-silence-of-resilience-2/

Maxwell, S. R. 2019, ‘Perceived threat of crime, authoritarianism, and the rise of a populist president in the Philippines’, International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 207-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2018.1558084

Mcfadden, S. M., Malik, A. A., Aguolu, O. G., Willebrand, K. S. & Omer, S. B. 2020, ‘Perceptions of the adult US population regarding the novel coronavirus outbreak’, Plos One, vol. 15, no. 4, article e0231808. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231808

Nazlidou, E.-I., Moraitou, D., Natsopoulos, D., Papaliagkas, V., Masoura, E. & Papantoniou, G. 2018, ‘Inefficient understanding of non-factive mental verbs with social aspect in adults: Comparison to cognitive factive verb processing’, Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, vol. 14, 2617–2631. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S165893

Ocampo, L. & Yamagishi, K. 2020, ‘Modeling the lockdown relaxation protocols of the Philippine government in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: An intuitionistic fuzzy DEMATEL analysis’, Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, vol. 72, article 100911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2020.100911

Paydos, T. 2020, ‘The essential role of government during COVID-19’, Forbes, 13 April 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ibm/2020/04/13/the-essential-role-of-government-during-covid-19/?sh=4a22f330114a

Polyzou, A. 2014, ‘presupposition in discourse’, Critical Discourse Studies, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 123-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2014.991796

Pontanilla, N. 2020, UP Department of Linguistics. [Facebook] 10 August. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/search/top?q=sana%20all%20department%20of%20linguistics

Statista 2020, ‘Filipinos perception of the government’s response to the coronavirus COVID-19 outbreak in 2020’, Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1103474/philippines-population-perception-of-government-response-coronavirus-covid-19/

Scheffer, M., Van Bavel, B., Van de Leemput, I. A. & Van Nes, E. H. 2017, ‘Inequality in nature and society’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 114, no. 50, pp. 13154–13157. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1706412114

Segal, E. A. 2011, ‘Social empathy: A model built on empathy, contextual understanding, and social responsibility that promotes social justice’, Journal of Social Service Research, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 266-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2011.564040

Simons, M. 2003, ‘Presupposition and accommodation: Understanding the Stalnakerian picture’, Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition, vol. 112, no. 3, pp. 251-278. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023004203043

Song, C., & Lee, J. 2015, ‘Citizens’ use of social media in government, perceived transparency, and trust in government’, Public Performance & Management Review, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 430–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2015.1108798

Starbuck, W. H. & Mezias, J. M. 1996, ‘Opening Pandora’s box: Studying the accuracy of managers’ perceptions’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 99-117. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199603)17:2<99::AID-JOB743>3.0.CO;2-2

Takahashi, B., Tandoc, E. C., Jr. & Carmichael, C. 2015, ‘Communicating on Twitter during a disaster: An analysis of tweets during Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines’. Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 50, 392–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.020

US Aid, Local Support Governance Program, 2008, ‘Good Governance Brief Citizen Engagement and Participatory Governance Challenges and Opportunities to Improve Public Services at the Local Level’. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnadq127.pdf

Van der Weerd, W., Timmermans, D. R., Beaujean, D. J., Oudhoff, J., & van Steenbergen, J. E. 2011, ‘Monitoring the level of government trust, risk perception, and intention of the general public to adopt protective measures during the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands’. BMC Public Health, vol.11, article 575. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-575

Warren, A. M., Sulaiman, A. & Jaafar, N. I. 2014, ‘Social media effects on fostering online civic engagement and building citizen trust and trust in institutions’, Government Information Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.11.007

Warren, M. E. 2009, ‘Governance-driven democratization’, Critical Policy Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460170903158040

Weber, T.J., Hydock C., Ding, W., Gardner, M., Jacob, P., Mandel, N., Sprott, D.E. & van Steenburg, E. 2021, ‘Political polarization: Challenges, opportunities, and hope for consumer welfare, marketers, and public policy’, Journal of Public Policy & Marketin. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743915621991103

Zulkifli, N., Rahman, S., Nurudin, S. M., Hamik, S. A., Mohamed, A. S. P. & Hashim, R. 2017, ‘Managing public perception towards local government administration’. International Journal of Public Policy and Administration Research, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 14–20. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.74/2016.3.2/74.2.14.20

1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 5th International Academic Conference on Humanities and Social Sciences, June 2021, Brussels, Belgium.