Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 15, No. 3

2023

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

Cosmopolitan Society and its Enemies: Historical Amnesia Narratives

Kazuma Matoba

Witten/Herdecke University, Witten, Germany

Corresponding author: Witten/Herdecke University, Alfred-Herrhausen-Str. 50, D- 58455 Witten, Germany, kazuma.matoba@uni-wh.de

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v15.i3.7901

Article History: Received 06/07/2023; Revised 02/01/2024; Accepted 09/02/2024; Published 28/03/2024

Citation: Matoba, K. 2023. Cosmopolitan Society and its Enemies: Historical Amnesia Narratives. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 15:3, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v15.i3.7901

Abstract

Since the end of the Cold War, the world has not abandoned ‘the dream of cosmopolitan peace’ (Alexander 2005). The adjective ‘cosmopolitan’ refers to the political and philosophical concept that all human beings are members of a single community. In the 21st century, however, the world faces a stark reality that is far from this vision, one which is consumed by an epidemic of social inequality and global injustice. The refugee crisis, climate injustice, racism, nationalism, terrorism, and other challenges are rooted in serious, untreated historical traumata which ultimately can lead to a collective form of amnesia related to these respective histories. I argue that to build a resilient, cosmopolitan society requires giving voice and expression to the narratives of victims of perpetration. And, equally important is to disclose the hidden intention in the historical narratives voiced by perpetrators. Through the exploration of these narratives, I argue, citizens will begin to wake up from their historical amnesia.

Keywords

Cosmopolitan Society; Historical Trauma; Cultural Trauma; Historical Trauma Narrative; Historical Amnesia Narrative

Introduction

Karl Popper wrote: ‘Had there been no Tower of Babel, we should invent it’ (Popper 1994, p. 158). His advocacy for the invention of a Tower of Babel was expressed in his essays and lectures, and specifically in his discourse on the Open Society and Its Enemies (1945). Since the publication of his book, an ‘open society’ based on a foundation of democracy has been established in many nations. Ulrich Beck attempts to adapt Popper’s ‘open society’ for the 21st century in Cosmopolitan Society and Its Enemies (Beck 2002). He explains that ‘cosmopolitan society’ is based on “dialogic imagination” or a vision of a globally shared collective future (p. 27). For Beck, ‘cosmopolitan society’ would be possible if we could learn from and survive in a ‘risk society’, a term that could accurately be applied to the conditions we are currently facing as we tackle local and global catastrophes and crises.

Borrowing Popper´s and Beck´s frameworks, this paper focuses on historical and cultural trauma and attempts to deliver a new perspective that elucidates the idea of a cosmopolitan society. A cosmopolitan society, I argue, can be achieved by reflecting on the prevailing narrative of historical amnesia, that is, forgetting which is prompted by collective traumatic experiences. In the present, we are, however, unaware that the world is suffering from this amnesia. This approach conforms to the cultural trauma theory of Jeffrey Alexander and the collective trauma integration work of Thomas Hübl, who formulate their transformative scientific perspectives as a means to construct a restorative cultural process within societies. This paper is organized in six sections: cosmopolitan society and reflexivity in sections 2 and 3, collective and historical trauma in section 4, cultural trauma and narratives in section 5, and resilience narrative for a cosmopolitan society in section 6.

Cosmopolitan Society

In the discussion about cosmopolitan society, Beck (2002) brings forth the notion of a ‘risk society’, which challenges people throughout the world to reflect more deeply on ways to co-create a more meaningful, sustainable and healthy future for all humankind as they work through the inherent risks. The global consciousness of a shared collective future is only possible if humans are aware of the ‘world risk society’. He writes ‘cosmopolitanism in the world risk society opens our eyes to the uncontrollable liabilities, to something that happens to us, befalls us, but at the same time stimulates us to make border-transcending new beginnings’ (Beck 2006, p. 341). The global awareness of the world risk society contributes not only to the social, political and economic ‘de-territorialization,’ but also to the social, political and cultural ‘de- and re-traditionalization’ (Beck 2002, p. 27) because it makes it irrevocably clear that the responsibility for positive change and to build a cosmopolitan society lies in our individual and collective responsibility, not with our enemy or foe.

The structure of modern society is exposed to risks such as pollution, disease, crime, terrorism, many of which are the result of modernization itself. A risk society is, as Beck (1992, p. 21) describes, ‘a systematic way of dealing with hazards and insecurities induced and introduced by modernization itself’. This kind of risk, called ‘manufactured risk’ by Giddens (1999), is the product of human activity, and societies have the potential for ‘reflexive introspection’, which allows its citizens and leaders to assess the level of risk that is being produced or is about to be produced. This reflexive introspection is characteristic not only of modernity, but also of the process of developing national institutionalizations over the past three centuries (Alexander 2005).

Throughout human history, societies have engaged in reflective introspection after collective crises, which spawned the next stage of their evolution. Since the end of the Cold War, the composite of human society has not abandoned ‘the dream of cosmopolitan peace’ (Alexander 2005, p. 89) in the discourse around globalization. Globalization is a political and economic construction which was produced as part of reflective introspection – across many societies in the world – on the heels of World War II. Alexander (2005, p. 85) explains, ‘Globalization appeared as response to the trauma of the twentieth century, in a moment of hope when it seemed, not for the first time, that the possibility for a worldwide civil society was finally at hand’. Globalization, still in progress, challenges the world with its side effects of manufactured risk, resulting in the refugee and climate crises, the COVID-19 pandemic, poverty, and modern slavery, among many other pressing challenges.

Absence of Reflexivity to Respond to Collective Trauma

In sociology, reflexivity is a cognitive and instrumental approach for problem-solving in which uncertainty, complexity, and ambivalence are handled through the use of rationality and technology (Boström, Lidskog, & Uggla 2017). Besides this definition, Beck (2009) focuses more on another aspect of reflexivity – self-confrontation. It refers to the capacity of an agent to recognize forces of unintended and unknown side effects and transform her/his situation in the social structure. We are often confronted with uncertain situations, like the climate crisis, in which citizens look for transparency and yearn to either participate in the problem-solving process or avoid it. We are used to receiving information and guidance from others in our society, such as from politicians and scientists, but not by searching for this information within our own lives and consciousness, unless we are directly confronted with and suffer from the direct impacts of global warming such as drought, rising see levels, wildfire and an influx of climate refugees. More than ever, individual reflexivity is required to enable citizens to witness the collective phenomena that result directly or indirectly from individual behaviors. For example, we expect more political strategies against global warming to secure our own survival, but the majority of people including government leaders do not want to make radical changes to their lifestyles by abandoning driving, flying, eating meat and imported foods, and turning towards sustainable practices. The German government wants to maintain the tax benefits of carbon-intensive company cars for high earners which increasingly cause a social and environmental misalignment.

The majority of people in the world are continuing with business as usual. There are several reasons why this is happening: First, many believe that making minor efforts to live and behave ethically has little impact on changing the world, so they deem it not worth the effort. Second, nobody complains about their individualistic lifestyles and behaviors; they believe that no one will constrain their freedoms, their basic human rights as part of a democratic society (cf. Rossen, Dunlop, & Lawrence 2015). Third, they lack empathy with those who are suffering. The empathy deficit is supported by a recent Gallup poll showing that roughly a third of the population of the United States does not think there is a problem with race relations (Gallup 2021). The limitation, or the absence, of individual reflexivity is common, and many of us choose to – and need to be – blind to all the serious challenges occurring in the world in order to function in our daily lives.

Scharmer & Kaufer (2013) coined the word ‘absencing,’ which refers to ‘our blind spot of not being aware which traps us in patterns of destruction and self-destruction’ and ‘holds on tightly to the past and does not dare to lean into the unknown, the emerging future’ (p. 25). Furthermore, as Scharmer & Hübl (2019) point out, this term describes the unseen part which is buried, but which we do not realize is buried, reflecting symptoms that are characteristic/indicative of collective trauma.

As a result of the phenomenon of ‘absencing’, we are unaware of the potential cultural hindrances around individual and societal development which are influenced by collective trauma (Scharmer & Hübl, 2019). For example, George Floyd´s murder in Minneapolis in May 2020 sparked the largest racial justice protests in the United States since the Civil Rights Movement. But the movement inspired a global reckoning with racism and becoming more aware of the fact that the historic racial trauma impacting people of color is built upon centuries of oppressive systems and racist practices that are deeply embedded within the nation´s fabric. Without such tragic events we might lack the reflexivity to respond to collective trauma, and we are also unaware of this absence of reflexivity. New generations of anti-racist activism in the U.S. may look back at this murder as a defining point. This absence of reflexivity in response to the risks of industrialization, modernization and globalization seem to cause a vicious circle that perpetuates such risks and their resulting trauma, both of which continue to remain beyond our reflexive capabilities. I offer this working hypothesis for consideration to inspire further research.

Due to the lack of reflexivity to respond to collective trauma, we may never achieve a cosmopolitan society, but remain stuck in a continuous inability to overcome a ‘risk society’. In this way, humans are repeatedly born into a traumatized society and suffer under ‘societal dysfunctions’. According to Johnson (2013), societal dysfunction occurs when social institutions do not positively contribute to the maintenance, or adaptation, of society, causing social, maladaptive, interpersonal, organizational and societal dysfunction. Many researchers of collective, historical and cultural trauma describe these dysfunctions as ‘post-traumatic socio-cultural dysfunction’ which are rooted in the post-traumatic individuation and socialization process of identity building (Lerner 2012; Matoba 2022). The next section offers an overview of collective and historical trauma research, highlighting three aspects: collective trauma bonding, historical unconsciousness, and the trauma field. These three, I propose, compose the ‘historical trauma narrative’, which I argue is the enemy of cosmopolitan society.

Collective and Historical Trauma1

Researchers who have contributed to defining collective trauma include Volkan (1997), Neal (1998), Koh (2021), Alexander (2012), Aydin (2017), Hirschberger (2018), Hübl (2020) and Matoba (2022). These scholars also study and utilize related terms such as: collective trauma, historical trauma and cultural trauma.

Collective trauma causes a large group to face drastic losses, feel helpless or victimized by another group, and share a humiliating injury (Matoba 2022). A large group does not choose to be victimized or suffer humiliation, but some members of this group unconsciously associate the trauma of an event they have experienced as part of their identity. ‘The fact that while groups may have experienced any number of traumas in their history, only certain ones remain alive over centuries’, leads Volkan (1997) to call these traumas that endure over centuries ‘chosen trauma’. This ‘is linked to the past generation’s inability to mourn losses after experiencing a shared traumatic event, and indicates the group’s failure to reverse narcissistic injury and humiliation inflicted by another large group, usually a neighbor’ (p. 7). The chosen trauma is ‘woven into the canvas of the ethnic or large group tent, and becomes an inseparable part of the group’s identity’ (p. 10).

Hübl (2020) writes about ‘collective and historical trauma’ which ‘refers to the effects of serious, untreated trauma which has been experienced by one or more members of a family, group, or community and has been passed down from one generation to the next through epigenetic factors’ (p. 66). His definition of trauma ranges from the painful and long-lasting consequences of colonization to occupation, enslavement and war. Collective or historical trauma can manifest in individuals as symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Collective trauma bonding can occur among the descendants of victims and be perpetuated in unconscious social patterns lived by descendants of perpetrators.

Collective Trauma Bonding

Catastrophic events such as genocide and war have been memorized and narrated as trauma both by the victims and the next generations. These patterns of behavior and habits influence the descendants of victims emotionally, mentally, and/or somatically. Vignoles et al. (2006) suggest that collective trauma may facilitate the construction of the various elements of meaning and social identity: purpose, values, efficacy and collective worth. These effects of trauma on the construction of collective meaning may increase as time elapses from the traumatic event (Klar, Schori-Eyal, & Klar 2013). This is, as Hirschberger (2018, p. 3) argues, ‘because the focus of memory shifts from the painful loss of lives to the long-term lessons groups derive from the trauma’. Little attention has been paid to the experiences of suffering and deaths of the victimized ancestors, usually because their group, community, or state has made enormous efforts to rebuild a culture (Matoba 2022). In this rebuilding process of a culture, its members were socialized into forming a coherent social identity by constructing meaning.

Many trauma therapists and researchers argue that individual trauma caused by a large-scale event must be viewed through the context of collective trauma (Matoba 2022). Collective and individual traumas are entangled as ‘a kind of collective trauma bonding’ (Hübl 2020, p. 91). Unconscious - unintended - entanglement or bonding influences collective and individual behaviors in a post-traumatic society and is exhibited as ‘a social form of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PSTD)’ (Lerner 2012). It creates unconsciousness as well as expressing it:

• Social pressure for silence: a traumatized society has become collectively withdrawn from public emotional expression and fatalistic in outlook. ‘Silence about the trauma is enforced by social pressure because it would be too painful to re-experience the original terror or shame’ (Rinker & Lawler 2018).

• Pseudo-safety: ‘The dominant community in such a traumatized society, having failed to work through their own past trauma, empowers itself by over-subjugating the oppressed. The dominant community tries to achieve a sense of pseudo-safety by force and justifies inhumane treatment of the oppressed by dehumanizing them socially and economically’ (Rinker & Lawler 2018).

• Conflict-in-process: In post-traumatic communities where people live the social legacies of long-term historical trauma, these communities are still dealing with the traumatic historical events in the context of ongoing violence (e.g., Sandole 1998).

• Vicarious trauma: certain descendants of a traumatized society have not been directly exposed to violence but exhibit the symptoms of having experienced the trauma. Furthermore, this trauma is constantly re-triggered and reinforced by virtue of proximity to a perceived ‘enemy other’ (Rothbart & Korostelina 2011, p.28), or what Volkan (1988) called ‘suitable targets for externalization’.

Those who experience these social forms of PTSD act out a guiding narrative of their identity. This narrative is the internalized and evolving story of the self that a person constructs to make sense and meaning out of his or her life. This narrative identity as descendants of victims draws disparate tribes together over generations and creates an inter-, and trans-, generational trauma and victimhood psychology. The collective and individual symptoms as effects of unconscious influence of this traumatic narrative identity are clearly evident in post-traumatic societies. The invisible entanglement between chosen traumas and narrative identity is enacted and reproduced in post-traumatic socio-cultural dysfunctions such as human rights violations, political corruption, economic instability, and radical politics, among other challenges (Matoba 2022).

Historical Unconsciousness

Hirschberger (2018, p. 3) points out ‘the effects of collective trauma on the construction of meaning is not limited to the victim group that needs to reinvent itself and reconstruct all that was lost, but also to the perpetrator group that must redefine itself and construct a positive moral image of the group in light of the atrocities it committed’. Hirschberger (2018, p. 9) sheds more light on the collective trauma that impacts perpetrators. Reminding them of the responsibility of their group for past misdeeds leads to derogation (Castano & Giner-Sorolla 2006) and to negative attitudes toward the victim group; it leads to a defensive attempt to protect the group by minimizing the historical crime (Doosje & Branscombe 2003), distorting the memory of the event (Frijda 1997; Dresler-Hawke 2005; Sahdra & Ross 2007), and justifying in-group behavior (Staub 2006). Members of perpetrator groups often display ‘blind spots’ in their memory of the event to eliminate inner conflict (Frijda 1997, p. 109; Dalton & Huang 2014), or deny the ongoing relevance of the past by demanding historical closure on this chapter in history (Hanke et al. 2013; Imhoff et al. 2017). Orange (2017) calls this blind spot ‘historical unconsciousness’.

In the U.S. the historical ‘unconsciousness silence about the U.S. history of settler colonialism’ leads people to be ‘ignorant and mute about our crimes of chattel slavery and racial domination, neither governments nor citizens can seriously tackle climate injustice until we confront this 400-year history’ (Orange 2017, p.37). Not only climate injustice but also many other social problems in the world can be rooted in a shared historical unconsciousness. I argue that ‘so far as perpetration of our ancestors has not been atoned sincerely by them and their descendants, the descendants are possessed by historical unconsciousness and their behaviors have negative impacts on the descendants of historical victims consequently’ (Matoba 2022). In this way the ancestral perpetration is entangled with the historical unconsciousness of descendants, and perpetration and victimization are repeating non-locally and cyclically.

Trauma Field

Aydin (2017) argues that ‘if the collective trauma is not dealt with, it will ultimately completely define the identity of a culture. Therefore, a culture will entirely coincide with its history, or even worse: with one dark page of its history’ (p. 131). The unintegrated collective trauma ‘disorganizes the community´s psychic economy because the beliefs, values, expectations, and ideals that are part of its cultural identity are radically shaken, challenged, and disrupted’ (p. 129). This inability to reconcile and resolve a dark episode of history can disrupt the organization of the values, expectations, and ideals of a victimized group to such a degree that it no longer can provide sufficient orientation and self-esteem (Volkan 2001, pp. 87–89). Consequently ‘the further development and flourishing of a group’s cultural identity can be severely disturbed and even completely obstructed’ (Aydin 2017, p. 129).

If the unintegrated collective trauma is too large to digest, it might damage the resilience of a culture and hinder its growth and flourishing. When the trauma cannot be integrated it remains invisible, separated from the cultural identity of the victims and their descendants. According to Aydin (2017, p. 131), ‘they are unable to integrate the trauma into their cultural identity and, at the same time, they can never let go of what has happened’. The unintegrated trauma becomes a shadow of culture which we can perceive but cannot express in language. Our language which is acquired in our socialization process is not adequate to describe it. Hiroshima/Nagasaki is undoubtedly a collective trauma of Japan. What has happened there is beyond the possibility of communication. There is no language for it. Additionally, there are silenced voices of ten-thousands of ethnic Korean atomic bomb survivors who had migrated or been mobilized to Japan under colonial rule. After several decades of legal proceedings in Japan, they became eligible for financial and medical support from the Japanese government in 2003 (Oh 2017). Such intentionally ignored pains by the Japanese Government has cast a long shadow in the process of societal and cultural rebuilding (Yamamoto 2015). Hübl (2020) calls this shadow of culture the ‘dark lake’ or ‘trauma field’ in which ‘large portions of energy are strongly dissociated and suppressed in shadow’ (p. 92).

This trauma field is not visible to members of the society, even while the symptoms produced by the trauma field are widely manifested throughout. The next generation is born into and raised within that field, into which the effects and structures of the collective trauma become wired and are perceived as normal. This conditioning makes it difficult for any person living within that community to realize a felt sense of its own trauma field (Matoba 2022).

Cultural Trauma and Narratives

For Alexander (2012) ‘cultural trauma occurs when members of a collectivity feel they have been subjected to a horrendous event that leaves indelible marks upon their group consciousness, marking their memories forever and changing their future identity in fundamental and irrevocable ways’ (p. 1). He reports on his empirical research and interpretation concerning the Holocaust, Hiroshima, Nanjing, and the India-Pakistan conflict, demonstrating that ‘this new scientific concept also illuminates an emerging domain of social responsibility and political action’. The collective memory of cultural trauma comprises not only a reproduction of the events, but also a continuing reconstruction of the trauma in an attempt to make sense of it (Matoba 2022). Cultural trauma remains beyond the lives of the direct survivors of the events, and is remembered, narrated, reconstructed and re-narrated by group members who may be far removed from the traumatic events in time and location.

We become who we are by finding our place within the social world which is structured around a particular order into which we are born. The social world is produced in patterns of action, ways of survival and symbolic terms, through language. Language divides up the world in particular ways to produce for every social grouping what it calls ‘reality’. Each language has its own way of doing this, but none of these is complete. There is always something that is missing, something that cannot be symbolized, as referred to in Lacanian psychoanalytic theory as ‘the real’ (Edkins 2003). A trauma field is the real, and ‘has to be hidden and forgotten, because it is a threat to the imaginary completeness of the subject’ (p. 11). We hide the trauma field (‘the real’), and stick with imagination and fantasy about what we call ‘social reality’ which ‘inscribes and re-inscribes traumas into everyday narratives’ (p. 13). The (re-)inscribed narratives about traumatic experiences are ‘broken narratives’ which are disruptive, fragmented and incoherent (Basseler 2019, p. 28). The memories of a trauma can feel like a jumbled mess of fragments which are told repeatedly as cohesive trauma narratives.

The fields of psychology and psychotherapy have established research on the importance of the trauma narrative expressed by trauma survivors. The narrative is used as a therapeutic support to help survivors make sense of their experiences. Sharing and expanding upon a trauma narrative enables people to organize their memories, making them more manageable and diminishing the painful emotions they carry. In contrast to the research on the trauma narratives of survivors, few studies have been conducted on the trauma narratives of perpetrators (e.g. the South African Truth and Reconciliation Process, cf. Gibson 2006).

Table 1 outlines key concepts on trauma symptoms and trauma narratives, either related to victims or perpetrators, visualized along a time axis (‘trauma time’ T0 – ‘post-trauma time’ T1 – ‘present time’ Tp). ‘Trauma time’ T0 is a moment in which many people in a community, a region or a state experienced a large-scale traumatic event collectively (collective or historical trauma). ‘Post-trauma time’ T1 refers to the lifespan of the symptoms affecting those who were traumatized after T0. They suffer from physical and psychological injuries and damages caused by traumatic events at T0 and later exhibit symptoms of various trauma-related disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at T1.

| Time | Victims | Perpetrators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancestors | Trauma time (T0) Post-trauma time (T1) | Symptoms | Depressive Disorder, Normative Reactions, Acute Stress Disorder, No Reaction, Anxiety Disorder, Substance Use Disorder, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (DSM-III 1980) | ‘Perpetrator-induced traumatic stress (PITS)’ (MacNair 2002) ‘Perpetrator trauma’ (McGlothlin 2020) ‘Dissociative amnesia’ (Loftus 1997) |

| Narratives | ‘Trauma narratives’ (Basseler 2019) ‘Post-trauma narratives’ (Meng 2020) | |||

| Descendants | Present time (Tp) | Symptoms | ‘social form of PTSD’ (Lerner 2012) ‘Trauma bonding’ (Hübl 2020) | ‘Historical unconsciousness’ (Orange 2017) |

| Narrative | ‘Historical trauma narratives’ (Mohatt et al. 2014) | Historical amnesia narratives | ||

Collective or historical traumas experienced by ancestors are transmitted through ‘trauma narratives’ and ‘post-trauma narratives’ from generation to generation. The next generations as descendants of traumatized ancestors live in ‘present time’ Tp after T0/T1 and may experience a ‘social form of PTSD’ and ‘trauma bonding’ which are expressed in ‘historical trauma narratives’ implicitly or explicitly. The transmitted trauma to descendants at Tp can be categorized as cultural trauma that results from the narrative process (remembering, narrating, reconstructing and re-narrating) of collective/historical trauma. There are very few studies about the traumas of the descendants of perpetrators and their narratives as part of the category of Tp.

The following three sections focus mainly on narratives at T0, T1 and Tp: trauma/post-trauma narratives of ancestors´ collective trauma at T0/T1 (5.1.), historical trauma narratives of victims´ descendants at Tp (5.2.), and historical amnesia narratives at Tp (5.3.).

Trauma/Post-trauma Narratives

The close relationship between trauma and narrative was reconfirmed as Holocaust survivors who began speaking of their somber responsibility to recount both their own stories and those who were murdered. In the 1970s U.S. Vietnam veterans began sharing stories of the horrors of war. Through the process of recalling collective atrocities, we see how trauma and narrative are tightly bound. Hartman (1995) writes that narrative can help us ‘read the wound’ of trauma (p. 537). Later, trauma theorists argued that the trauma narrative possesses a value for communicating our deepest psychic pains (cf. Schauer, Neuner, & Elbert 2011).

According to Brabeck & Ansilie (2008) there are two aspects of narrative trauma: psychoanalytic and anthropological. The psychoanalytic aspect of trauma narrative theorizes that individual identities become embedded within a particular group identity, thereby distinguishing its own us/we group from the them/they group. In the trauma narrative one externalizes the unintegrated aspects of her-/himself that threaten coherent identity and summon only the memories that support her/his claims. Moreover, she/he projects the unsettling aspects of her-/himself onto the ‘other’ through expressing narratives about who ‘we’ are vs. who ‘they’ are (Novey 1968). Similar processes of externalization and projection function on a collective level of the trauma narrative (Volkan 1988; 1997). Communities under the stress of trauma need to strengthen the community´s sense of identity and emphasize the narrative through the use of symbols, slogans, and concepts that link their members. Simultaneously communities need to externalize and project onto ‘others’ the parts of themselves they deny, or that which is unwanted within themselves. One recent example: following the pandemic years of COVID-19, China is now experiencing a domestic real estate crisis and economic slowdown. Domestic unrest may lead the government to direct attention to international affairs, for example, China may ‘embrace even more aggressive nationalism as a basis for legitimacy and accelerate efforts to unify Taiwan with China’ (Fravel 2023).

In contrast to the psychoanalytical, the anthropological aspects of the trauma narrative focus on ‘socio-political conditions in their explanations of why one story is privileged over another’, and ‘the implication for the story that is not told’, which is called ‘silenced narratives’ (Brabeck & Ansilie 2008, p. 4). Trouillot (1995) argues that narratives are silenced when they fail to be ‘unthinkable’ within the worldview of those in power in terms of political power, class, gender and racial relations. Trauma narratives with these aspects – psychoanalytic and anthropological – construct meaning or ‘cultural meaningfulness’ (Vu & Brockmeier 2003, p. 282), which influences what to think, what to forget, and what/how to communicate with others. As Leese (2022, p. 16) points out, trauma narratives are ‘constituted from the cultural heritage and resources available to the teller.’

The post-trauma narrative recounts the belated pains and problems that directly follow trauma, with a focus on the present, unlike the trauma narrative which focuses on recalling the past. Meng (2020) analyses fragmented memories and screening nostalgia for the cultural revolution in China and compares post-trauma narratives with previous traumatic narratives that were popular in the late 1970s and 1980s. Although they both center around the pain and healing of the past, (1) ‘the previous traumatic narrative often exposes this pain in the past tense and seeks a cathartic ending’; (2) ‘the post-trauma narrative reveals a fragmented yet protracted agony in the present’; (3) ‘post-trauma narrative believes that people have to face the past and their pain, even if there may be no simple solution in the form of healing and redemption’ (p. 94). In post-trauma narratives, which express implicitly and explicitly the lasting pains from the past, the past and the present are in tension, and at the same time have many similarities, ‘as well as having an intriguing connection’ (p. 94). In this way, we might say that the coexistence of the past and the present in post-trauma narrative represents the social reality of contemporary society which, at its core, is rife with ambiguity and fragmentation.

Historical Trauma Narratives

Mohatt et al. (2014) argue that historical trauma functions as a public narrative that connects present-day experiences (Tp) and circumstances to the trauma (To and T1), which leads to a negative impact on health. Historical trauma itself affects psychological health of a particular group or communities through the experience of loss at T0 and T1. The empirical research on historical trauma, especially intergenerational trauma related to the Holocaust, has followed the development of the theory that links historical trauma to individual and community health (Bar-on et al. 1998; Brave Heart & DeBruyn 1998).

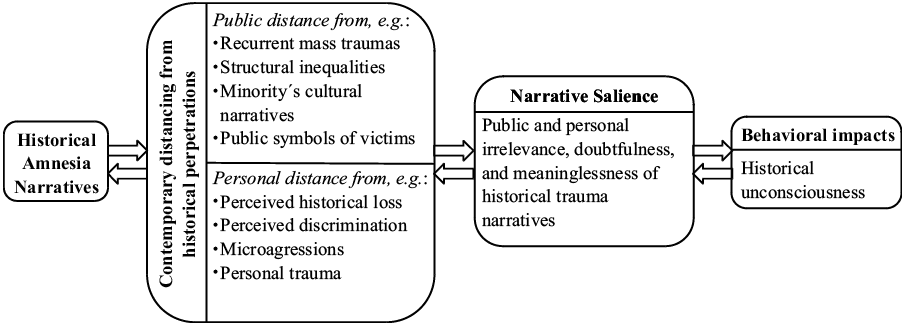

Historical trauma narratives are public narratives that are constructed, told, interpreted and re-told collectively at Tp by descendants of a particular group or community who experienced traumatic events at T0 and T1. These narratives link the historical past through meaning-making to contemporary circumstances (Crawford 2013; Gone 2013). Mohatt et al. (2014) propose a narrative model of how historical trauma impacts health. Figure 1 is designed to reflect experiential observations of historical trauma narratives as they connect historical traumas to health impacts. This happens through public and personal contemporary reminders and the degree of narrative salience like relevance, believability and meaningfulness. Each stage of the narrative model is recursively influenced by the connecting stages.

Figure 1. Narrative Model of How Historical Trauma Impacts Health (Mohatt et al. 2014)

A narrator who relates their story as a contemporary reminder ‘contextualizes one´s lived experience and interpretation of historical trauma’ (p. 9). Public reminders are collectively experienced events, symbols, contexts, systems, and structures that recall historical trauma narratives, while personal reminders are individually experienced and relate to historical traumas through an individual’s personal narratives. Figure 1 depicts how historical trauma narratives may be more or less salient to an individual or community, and also shows how narrative salience influences health impacts. Many scientists have identified a range of negative health outcomes in response to historical trauma and used historical trauma as an explanatory framework for understanding a wide-range of health disparities through psychological, social and biological mechanisms (Crawford 2013; Daley 2006; Gone & Trimble 2012; Sotero 2006; Walters et al. 2011).

Perpetrator Trauma and Historical Amnesia Narratives

Recent research on trauma and the trauma narrative focuses mainly on experiences of victims of violence. However, Sigmund Freud, a foundational theorist in early psychological investigations of trauma, collected examples of traumatization not only from the victims of violence, but also from the perpetrators (McGlothlin 2020, p.102). The prevalence of symptoms among Vietnam War veterans – and of those who were the perpetrators – played an important role in the initial establishment of PTSD as a recognized disorder. PTSD was first introduced to the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980. The definition emphasizes ‘primarily the experience and aftermath of severe deprivation, victimization, and personal life-threat [rather than on] the moral conflict, shame, and guilt produced by taking a life in combat’ (Maguen et al. 2009, p. 435). The perspective of experiencing or witnessing trauma was emphasized over the perspective of the enacting perpetrator behavior that brought about the traumatic conditions of the war. MacNair (2002) criticizes the contemporary PTSD researchers´ belief ‘that all PTSD symptoms must relate to what the enemy did, not what the soldier did’ (p. 162).

One of the most critical issues in the research of perpetrator trauma is the unclear definition of perpetrator and diverse descriptions of perpetrations. McGlothlin (2020, p. 101) distinguishes two categories of perpetrations:

• the collective commission of mass crimes and cruelties, whether punctual or sustained, intentional or structural (such as military violence; state-sanctioned mass atrocity; genocide; oppression and expropriation associated with colonization; terrorism; and institutionalized racism, sexism and economic inequality)

• violence originating with and committed against individuals (including murder, sexual assault, domestic violence and other forms of personal terrorism, such as bullying)

It is impossible to represent adequately all the ways in which trauma can play out in the diverse contexts of perpetrations. For this reason, there is little research or academic literature on war/genocide perpetrator trauma. As McGlothlin (2020, p. 100) writes, ‘The experience of perpetrators, on the other hand, has fallen outside of this normative trauma paradigm by virtue of the greater cultural commitment to and even identification with victims’ experience of suffering’. Although trauma research has not been interested in describing the process of how perpetrators experience trauma through their very commission of violence, mental health professionals and legal decision-makers have often reported evidence of memory impairment in perpetrators of extreme violence such as homicide (e.g., Kopelman 1995; Roesch & Golding 1986; Schacter 1986). This memory loss has been discussed as ‘dissociative amnesia’ which is characterized as a sudden inability to remember important personal information within a traumatic and criminal experience not caused by brain trauma or ordinary forgetfulness (Porter et al. 2001). It is easily imaginable that dissociative amnesia of perpetration at To and T1 may influence perpetrators´ communication, which should be a focus of perpetrator narrative research at T0 and T1.

‘Historical unconsciousness’, discussed in the previous section, is a mental state of being, brought on by adopting the historical trauma narrative of the dominant social group at Tp. This narrative is often expressed by community or cultural members whose ancestors were positioned on the side of perpetrations, or who are descendants of perpetrators. This narrative is primarily produced by the dominant group in society which has a political intention to hide the ‘bad-behavior-of-us’, which is not different than the ‘bad-behaviors-of-our ancestors’. This political intention is suggested indirectly in the narrative by expressing one’s own victimhood (us), caused by immoral others (them) as ‘suitable targets of externalization’ (Volkan 1988, p. 31). Such historical trauma narratives are welcomed and widely accepted, without critique from political opposites, so that the narratives are comprehended as common sense among people within society. Over time, the original political intention is forgotten, which leads to amnesia that cannot be recognized and diagnosed. I call this the ‘historical amnesia narrative’ which belongs to the ‘perpetrator historical trauma narratives’ (cf. McGlothlin 2008; Lampropoulos & Markidou 2010; Zlatar-Violić 2020).

One example of historical amnesia narrative is ‘sustainable development’. Telleria & Garcia-Arlas (2022) analyze critically the United Nations 2030 Global Development Agenda, calling the ‘sustainable development goals (SDG)’ a ‘fantasmatic narrative’. Their argument is that ‘sustainable development is the empty signifier that articulates and sustains the agenda’s discourse’. Their analysis suggests that ‘the agenda naturalizes and consolidates the existing status quo: a status quo that has created (and continues to perpetuate) the global problems that the agenda aims to solve’. One example is the electric car. Electric vehicles powered by clean energy sources enhance the share of renewable energy in the energy mix (SDG target 7.2) and help combat air pollution and related health impacts (SDG target 3.9). Lithium-ion cells that power most electric vehicles rely on metals like cobalt, lithium and rare earth elements. These raw materials are linked to grave environmental and human rights concerns; mining cobalt, in particular, produces hazardous tailings and slags that can leach into the environment. Studies have found high exposure in nearby communities, especially among children, to cobalt and other metals. The process of extracting the metals from their ores also emits sulfur oxide and other harmful air pollution. Almost 70 percent of the world’s cobalt supply is mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a substantial proportion in unregulated mines where workers including many children dig for metal using only hand tools, actions that are a great risk to their health and safety, human rights groups warn (Tabuchi & Plumer 2021). Figure 2, analogically based on Figure 1, visualizes a hypothetical relation between historical amnesia narratives and ethical behaviors.

Figure 2. Narrative Model of How Historical Amnesia Narratives Impacts Ethics (original)

As Figure 2 suggests, ‘sustainable development’ as a historical amnesia narrative has a function of distancing from historical perpetration – colonization, globalization and environmental degradation. This distancing can be observed both in the public/political and personal spheres. Throughout the SDG Report 2022 (United Nations 2022), the word ‘climate change’ is used 34 times, but ‘global warming’ appears only two times. According to Ouassil & Karig (2021), the former US Vice President and former oil company executive Dick Cheney chose the phrase ‘climate change’ instead of ‘global warming’, for political reasons since he didn’t want to instill fear among the public. Laming (2019) reports that the public/political distancing from ‘global warming’ by paraphrasing it as ‘climate change’ was influenced by the Republican Party and the US oil and gas lobby. Referring to the personal distancing most people feel when it comes to approaching the climate crisis, Marshall (2021) asks ‘Why are our brains wired to ignore climate change?’ Many people think ‘sustainable development’ is ‘too boring’ to command public attention, ‘too vague’ to provide guidance, and ‘too late’ to address the world’s problems (Dernbach & Cheever 2015, p. 247). A ‘sustainable development’ narrative leads both public and personal opinions into a ‘historical unconsciousness’, forcing us to regard historical trauma narratives which are influenced by colonization, globalization and global warming as irrelevant, doubtful and meaningless. These examples illustrate historical unconsciousness – doing nothing and just acting as bystanders – which results from a historical amnesia narrative. Leading to negative impacts on our behavior and ethics.

In contrast, a diversity of socio-ecological concepts and environmental movements as alternatives to green capitalism have emerged in various regions of the world since the beginning of this century. For example ‘Buen Vivir’ (Gudynas 2011), ‘Ubuntu’ (Metz 2011), ‘Degrowth’ (Kallis, Kerschner, & Martinez-Alier 2012) and ‘Inner Development Goals’ (Stålne & Greca 2022) all seek to achieve more fundamental transformations. Unlike SDG, which is falsely believed to be universally applicable, these alternative approaches cannot be reduced to a single model.

Resilience Narrative for a Cosmopolitan Society

Post-trauma communities in which historical trauma narratives and historical amnesia narratives are spoken implicitly or explicitly in personal and public daily life need ‘social resilience’ for constructive social development. ‘Social resilience’ is the capacity of social groups and communities to recover from, or respond positively to, crisis (Maguire & Hagan, 2007, p. 16). Basseler (2019) argues that ‘resilience might be fruitfully conceptualized within social and ecological discourses as a response to the risk society’ (p. 22) and ‘can be understood as a concerted response to the realities of the global risk society and its actual and potential traumas’ (p. 23). Social resilience can be promoted through ‘resilience narratives’ which are constructed by competent narrators, who should not be those in power, but involve indigenous, underrepresented peoples, and those of the Global Majority. They can make a ‘sustained effort at reconstructing some kind of coherence and continuity’ (p. 28) and can offer the interpretive framework that enables citizens to recognize historical trauma narratives and historical amnesia narratives by practicing dialogue with an open awareness of the hermeneutic circle, so that they can move from an interpretation of the broader context of a perspective to an interpretation of the detailed elements of the voiceless message from the world.

One possible effective method of enhancing social resilience is the ‘Collective Trauma Integration Process (CTIP)’ which was developed by Thomas Hübl (Hübl 2020). This method leads participants to the conscious perception of personal emotional, cognitive and physical processes by voicing and attuning to trauma which had been silenced, while relating to the group as witnesses. Wagner, Strasser, & Schäpke (2022) report that the trauma-informed large group process based on CTIP in Germany could raise public awareness of resilience narratives and overcome the absence of reflexivity to respond to historical trauma, current crises and social polarization.

To uncover historical amnesia and (re-)construct resilience narratives, face-to-face interactions are insufficient. Learning to transform the historical amnesia narrative into the resilience narrative of civil solidarity after intense periods of social fragmentation and polarization requires much more than simple communication. It depends on deeply emotional and highly symbolic social performances of reconciliation. Alexander (2005, p. 7) writes ‘Only via such cultural performances can experiences of collective and historical trauma become occasions for reconstructing collective identity, one in which antipathy gives way to mutual identification’. If a new structure designed to cultivate a sense of healing is constructive, then civil consciousness can flourish, advancing societies towards a constitution that is truly cosmopolitan. In resilience narratives created by social performance, powerful symbols must be projected and materialized in community and society, such as ‘trauma-informed journalism’ (Ogunyemi & Price 2023), ‘developing urban resilience’ (Bugno-Janik & Janik 2020), ‘reconciliation pedagogy’ (Bekermann & Zembylas 2012), and ‘art as a political witness’ (Lindroos & Möller 2017). Engaging in civil discourse through the lens of a resilience narrative builds the cultural foundations for peace. Both sharing and living this narrative allow for democratic recognition, transforming ignorance and aggression into agnostic dialogue and providing opportunities for meaning-making that can transform a society conditioned by absencing into a cosmopolitan society.

Conclusion

Karl Popper wrote The Open Society and Its Enemies while in political exile during World War II. This book was first published in 1945 and is considered a powerful and profound defense of democracy against totalitarian regimes. They have caused many collective, intergenerational and historical traumas throughout the world, and many of these traumas have not been fully healed and continue to manifest as traumatic symptoms. In this context, globalization has been promoted and embraced, creating risks and cultural traumas as a side effect (Beck 2002).

Since I began writing this article, the world has been completely upended by the Russian-Ukrainian war (since February 2022) and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (since October 2023). Witnessing and confronting this terrible world reality sadly confirms my working hypothesis: the lack of reflexivity with regard to the risks generated as side effects of industrialization, modernization and globalization creates a vicious circle that perpetuates these risks and the resulting traumas. This is a hypothesis that is provisionally accepted as a basis for ongoing and future research, in the hope that a viable theory and practice for realizing the ‘dream of cosmopolitan peace’ (Alexander 2005) through ‘dialogical imagination’ (Beck 2002) will be produced. To continue current studies and promote future research, we need more inter- and transdisciplinary collaborations between psychology, psychotherapy, sociology, political science, peace studies, medicine, neuroscience, and communication studies, as well as more in-depth dialogues between science, politics, and the arts. All these efforts beyond boundaries may hopefully promote the most important transgenerational sustainable dialogue to unravel the ‘collective trauma bonding’ and to transcend the positions of past perpetrators and victims who have been the actors in our historical traumas by listening to ‘historical amnesia narratives’.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the following individuals in the information collection and improvement of the manuscript: Thomas Hübl, Lori Shridhare, and Simon Spire.

References

Alexander, J. C. 2005, ‘Globalization as collective representation: The new dream of a cosmopolitan civil sphere’, International Journal of Politics, Culture, & Society, vol. 19, no. 1-2, pp. 81-90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-007-9017-1

Alexander, J. C. 2012, Trauma: A Social Theory, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Aydin, C. 2017, ‘How to forget the unforgettable? On collective trauma, cultural identity, and mnemotechnologies’, Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 125-137. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2017.1340160

Bar-On, D., Eland, J., Kleber, R. J., Krell, R., Moore, Y., Sagi, A., Soriano, E., Suedfeld, P., van der Velden, P. G., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. 1998, ‘Multigenerational perspectives on coping with the Holocaust experience: An attachment perspective for understanding the developmental sequelae of trauma across generations’, International Journal of Behavioral Development, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 315–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/016502598384397

Basseler, M. 2019, ‘Stories of dangerous life in the post-trauma age: Toward a cultural narratology of resilience’, In: Erll, A. & Sommer, R. (eds), Narrative in Culture, De Gruyter, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110654370-002

Beck, U. 1992, Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity, Sage, London.

Beck, U. 2002, ‘The cosmopolitan society and its enemies’, Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 19, no. 1-2, pp. 17-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327640201900101

Beck, U. 2006, Cosmopolitan Vision, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Beck, U. 2009, World at Risk, Polity Press. Cambridge.

Bekerman, Z. & Zembylas, M. 2012, Teaching Contested Narratives: Identity, Memory and Reconciliation in Peace Education and Beyond, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139015646

Boström, M., Lidskog R., & Uggla, Y. 2017, ‘A reflexive look at reflexivity in environmental sociology’, Environmental Sociology, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 6-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2016.1237336

Brabeck, K. & Ansilie, R. 2008, ‘The narration of collective trauma: The true story of Jasper, Texas’, Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 123-142. https://doi.org/10.1057/pcs.2008.6

Brave Heart, M. Y. H. & DeBruyn, L. M. 1998, ‘The American Indian Holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief’, American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 56–78. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9842066/ https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.0802.1998.60

Bugno-Janik, A. & Janik, M. 2020, ‘City and Water: The problem of trauma in the process of developing urban resilience’, Zarządzanie Publiczne Public Governance, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 67-84. https://doi.org/10.15678/ZP.2020.54.4.06

Castano, E. & Giner-Sorolla, R. 2006, ‘Not quite human: Infrahumanization in response to collective responsibility for intergroup killing’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 90, no. 5, pp. 804–818. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.804

Crawford, A. 2013, ‘The trauma experienced by generations past having an effect in their descendants: Narrative and historical trauma among Inuit in Nunavut, Canada’, Transcultural Psychiatry, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461512467161

Daley, T. C. 2006, ‘Perceptions and congruence of symptoms and communication among second-generation Cambodian youth and parents: A matched-control design’, Child Psychiatry and Human Development, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-006-0018-5

Dalton, A. N. & Huang, L. 2014, ‘Motivated forgetting in response to social identity threat’, Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 1017–1038. https://doi.org/10.1086/674198

Dernbach, J. & Cheever, F. 2015, ‘Sustainable development and its discontents’, Transnational Environmental Law, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 247–287. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102515000163

Doosje, B. & Branscombe, N. R. 2003, ‘Attributions for the negative historical actions of a group’, European Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.142

Dresler-Hawke, E. 2005, ‘Reconstructing the past and attributing the responsibility for the Holocaust’, Social Behaviour and Personality: An International Journal, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 133–148. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2005.33.2.133

Edkins, J. 2003, Trauma and the Memory of Politics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511840470

Fravel, M. T. 2023, The myth of Chinese diversionary war, Foreign Affairs, 15 September. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/myth-chinese-diversionary-war

Frijda, N. H. 1997, ‘Commemorating’, In: Pennebaker, J.W., Paez, D. & Rimé, B. (eds), Collective Memory of Political Events: Social Psychological Perspectives, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 103–127.

Gallup, 2021, Race Relations. https://news.gallup.com/poll/1687/race-relations.aspx

Gibson, J. L. 2006, ‘The contributions of truth to reconciliation: Lessons from South Africa’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 409-432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002706287115

Giddens, A. 1999, Runaway World: How Globalization is Reshaping Our Lives, Profile, London.

Gone, J. P. 2013, ‘Redressing First Nations historical trauma: Theorizing mechanisms for Indigenous culture as mental health treatment’, Transcultural Psychiatry, vol. 50, no. 5, pp. 683-706. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461513487669

Gone J. P. & Trimble J. E. 2012, ‘American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: Diverse perspectives on enduring disparities’, Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, vol. 8, pp. 131–160. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127

Gudynas, E. 2011, ‘Buen Vivir: Today’s tomorrow’, Development, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 441-447. https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2011.86

Hanke, K., Liu, J. H., Hilton, D. J., Bilewicz, M., Garber, I., Huang, L. L., Gastardo-Conaco, C., & Wang, F. 2013, ‘When the past haunts the present: Intergroup forgiveness and historical closure in post World War II societies in Asia and in Europe’, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.05.003

Hartman, G. H. 1996, The Longest Shadow: In the Aftermath of the Holocaust, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN.

Hirschberger, G. 2018, ‘Collective trauma and the social construction of meaning’, Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 9, article 1441. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01441

Hübl, T. 2020, Healing Collective Trauma: A Process for Integrating our Intergenerational and Cultural Wounds, Sounds True, Boulder, CO.

Imhoff, R., Bilewicz, M., Hanke, K., Kahn, D. T., Henkel-Guembel, N., Halabi, S., Sherman, T.-S., & Hirschberger, G. 2017, ‘Explaining the inexplicable: Differences in attributions to the Holocaust in Germany, Israel and Poland’, Political Psychology, vol. 38, vol. 6, pp. 907–924. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12348

Johnson, H. M. 2013, Sociology: A Systematic Introduction, Routledge, London.

Kallis, G., Kerschner, C., & Martinez-Alier, J. 2012, ‘The economics of degrowth’, Ecological Economics, vol. 84, pp. 172-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.017

Klar, Y., Schori-Eyal, N., & Klar, Y. 2013, ‘The ‘Never Again’ state of Israel: The emergence of the Holocaust as a core feature of Israeli identity and its four incongruent voices’, Journal of Social Issues, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12007

Koh, E. 2021, ‘The healing of historical collective trauma’, Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 115–133. https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.15.1.1776

Kopelman, M. D. 1995, ‘The assessment of psychogenic amnesia’, In: Baddeley, A. D., Wilson, B. A., & Watts, F. N. (eds), Handbook of Memory Disorders, Wiley, Chichester, pp. 427-448.

Laming, J. 2019, ‘Goodbye global warming: Why environmental terminology matters’, Good Energy, 21 February. https://www.goodenergy.co.uk/goodbye-global-warming-why-environmental-terminology-matters/

Lampropoulos, A. & Markidou, V. 2010, ‘Configuring cultural amnesia’, Synthesis: an Anglophone Journal of Comparative Literary Studies, No. 2, pp. 2–6. https://doi.org/10.12681/syn.16485

Leese, P. 2022, ‘The limits of trauma: Experience and narrative in Europe c. 1945’, In: Kivimaki, V. & Leese, P. (eds), Trauma, Experience and Narrative in Europe after World War II, Palgrave Macmillan, Geneva. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84663-3_1

Lerner, M. 2012, Embracing Israel/Palestine: A Strategy to Heal and Transform the Middle East, North Atlantic Books, Berkeley, CA.

Lindroos, K. & Möller, F. 2017, Art as a Political Witness, Barbara Budrich Publishers, Leverkusen. https://doi.org/10.3224/84740580

Loftus, E. F. 1997, ‘Creating false memories’, Scientific American, vol. 277, pp. 70-75. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0997-70

MacNair, R. 2002, Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress: The Psychological Consequences of Killing, Praeger, Westport, CT.

Maguen, S., Metzler, T., Litz, B., Seal, K., Knight, S., & Marmar, C. 2009. ‘The impact of killing in war on mental health symptoms and related functioning’, Journal of Traumatic Stress, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 435–443. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20451

Maguire, B. & Hagan P. 2007, ‘Disasters and communities: Understanding social resilience’, Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 16-20.

Matoba, K. 2022, ‘“Measuring” collective trauma: A quantum social science approach’, Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, vol. 57, pp. 412-431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-022-09696-2

McGlothlin, E. 2020, ‘Perpetrator trauma’, In: Davis, C. & Meretoja, H. (eds), The Routledge Companion to Literature and Trauma, Routledge, New York, NY, pp. 100-110. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351025225

Meng, J. 2020, Fragmented Memories and Screening Nostalgia for the Cultural Revolution, Screen, vol. 62, no. 3, pp. 432-435. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjab043

Metz, T. 2011, ‘Ubuntu as a moral theory and human rights in South Africa’, African Human Rights Law Journal, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 532-559. https://philarchive.org/rec/METUAA-2

Mohatt, N. V., Thompson, A. B., Thai, N. D, & Tebes, J. K. 2014, ‘Historical trauma as public narrative: A conceptual review of how history impacts present-day health’, Social Science & Medicine, vol. 106, pp. 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.043

Neal, A. G. 1998, National Trauma and Collective Memory: Major Events in the American Century. M. E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY.

Novey, S. 1968, The Second Look: The Reconstruction of Personal History in Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis, Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, MD.

Ogunyemi, O. & Price, L. T. 2023, ‘Exploring the attitudes of journalism educators to teach trauma-informed literacy: An analysis of a global survey’, Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, vol. 78, no. 2, pp. 214-232. https://doi.org/10.1177/10776958221143466

Oh, E. J. 2017, ‘Memories and records in bureaucratic red tape: The acquisition process of Hibakusha Techō by the Korean atomic bomb survivors’, Seoul Journal of Japanese Studies, vol. 3, no.1, pp. 103-126. https://s-space.snu.ac.kr/bitstream/10371/135181/1/06_OH%20Eun%20Jeong.pdf

Orange, D. 2017, Climate Crisis, Psychoanalysis, and Radical Ethics, Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315647906

Ouassil, S. E. & Karig, F. 2021, Erzählende Affen. Mythen, Lügen, Utopien, Ullstein, Berlin.

Popper, K. 1945. The Open Society and its Enemies: Volume 1: The Shell of Plato, Routledge, London.

Popper, K. 1994, In Search of a Better World: Lectures and Essays from Thirty Years, Translated by L. J. Bennett, Routledge, London.

Porter, S., Birt, A. R., Yuille, J. C., & Hervé, H. F. 2001, ‘Memory for murder: A psychological perspective on dissociative amnesia in legal contexts’, International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 23-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2527(00)00066-2

Rinker, J. & Lawler, J. 2018, ‘Trauma as a collective disease and root cause of protracted social conflict’, Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000311

Roesch, R. & Golding, S. L. 1986, ‘Amnesia and competency to stand trial: A review of legal and clinical issues’, Behavioral Sciences and the Law, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 87-97. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2370040107

Rossen, I., Dunlop, P. D., & Lawrence, C. M. 2015, ‘The desire to maintain the social order and the right to economic freedom: Two distinct moral pathways to climate change scepticism’, Journal of Environmental Psychology. vol. 42, pp. 42-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.01.006

Rothbart, D. & Korostelina, K. 2011, Why They Die: Civilian Devastation in Violent Conflict, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.1913185

Sahdra, B. & Ross, M. 2007, ‘Group identification and historical memory’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 384–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206296103

Sandole, D. 1998, ‘A comprehensive mapping of conflict and conflict resolution: A three pillar approach’, Peace and Conflict Studies, vol. 5, no. 2, article 4. https://doi.org/10.46743/1082-7307/1998.1389

Schacter, D. L. 1986, ‘Amnesia and crime: How much do we really know?’, American Psychologist, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 286-295. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.3.286

Scharmer, O. & Hübl, T. 2019, ‘Collective trauma and our emerging future: Global Social Witnessing’, Kosmos: Journal for Global Transformation, Winter Quarterly 2019. Retrieved on February 12, 2020, from https://www.kosmosjournal.org/kj_article/collective-trauma-and-our-emerging-future/

Scharmer, O. C. & Kaufer, K. 2013, Leading from the Emerging Future: From Ego-System to Eco-System Economies, Berett-Koehler Publishers, Oakland, CA. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137468208_12

Schauer, M., Neuner, F., & Elbert, T. 2011, Narrative Exposure Therapy, Hogrefe, Göttingen.

Sotero, M. 2006, ‘A onceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research’, Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 93–108. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1350062

Staub, E. 2006, ‘Reconciliation after genocide, mass killing, or intractable conflict: understanding the roots of violence, psychological recovery, and steps toward a general theory’, Political Psychology, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 867–894. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20447006. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00541.x

Stålne, S. & Greca, S. 2022, Inner Development Goals: Phase 2 Research Report, 12 September. https://idg.tools/assets/221215_IDG_Toolkit_v1.pdf

Tabuchi, H. & Plumer, B. 2021, ‘How green are electric vehicles?’, The New York Times, 2 March. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/02/climate/electric-vehicles-environment.html

Telleria, J. & Garcia-Arlas, J. 2022, ‘The fantasmatic narrative of ‘sustainable development’. A political analysis of the 2030 Global Development Agenda’, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 241-259. https://doi.org/10.1177/23996544211018214

Trouillot, M.-R. 1995, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, Beacon Press, Boston, MA.

United Nations, 2022, The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022, United Nations Publications, New York, NY. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2022.pdf

Vignoles, V. L., Regalia, C., Manzi, C., Golledge, J., & Scabini, E. 2006, ‘Beyond self-esteem: influence of multiple motives on identity construction’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 90, no. 2, pp. 308–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.2.308

Volkan, V. D. 1988, The Need to Have Enemies and Allies: From Clinical Practice to International Relationships, Jason Aronson, Lanham, MD.

Volkan, V. D. 1997, Bloodlines: From Ethnic Pride to Ethnic Terrorism, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, NY.

Volkan, V. D. 1998, ‘Transgenerational transmissions and chosen traumas’, XIII International Congress International Association of Group Psychotherapy, London, 23-29 August.

Volkan, V. D. 2001, ‘Transgenerational transmissions and chosen traumas: An aspect of large-group identity’, Group Analysis, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/05333160122077730

Vu, N. & Brockmeier, J. 2003, ‘Human experience and narrative intelligibility’, In: Stephenson, N., Radtke, H. L., Jorna, R., & Stam, H. J. (eds), Theoretical Psychology: Critical Contributions, Selected Proceedings of the Ninth Biennial Conference for the International Society for Theoretical Psychology, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, June 3-8, 2001, Captus University Publications, Toronto.

Wagner, A., Strasser, J., & Schäpke, N. 2022, Overcoming Polarization in Crises: A Research Project on Trauma and Democracy with over 350 Citizens, Pocket Project e.V. & Mehr Demokratie e.V., Wardenburg & Berlin. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366353517_Overcoming_polarization_in_crises_A_research_project_on_trauma_and_democracy_with_over_350_citizens

Walters, K. L., Mohammed, S. A., Evans-Campbell, T., Beltrán, R. E., Chae, D. H., & Duran, B. 2011, ‘Bodies don’t just tell stories, they tell histories’, Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X1100018X

Yamamoto, A. 2015, 核と日本人-ヒロシマ、ゴジラ、フクシマ [Nuclear and Japanese - Hiroshima, Godzilla, Fukushima], Chuokoron-sha, Tokyo.

Zlatar-Violić, A. 2020, ‘Culture of memory or cultural amnesia: The uses of the past in the contemporary Croatian novel’, In: Gorup, R. (ed), After Yugoslavia: The Cultural Spaces of a Vanished Land, Stanford University Press, Redwood City, CA, pp. 228–240. https://doi.org/10.11126/stanford/9780804784023.003.0016

1 This section represents my core thoughts about collective trauma. The ideas elaborated here were developed mainly in Matoba (2022).