Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Vol. 13, No. 2

2021

ARTICLE (REFEREED)

Social Value Orientations and Public Confidence in Institutions: A Young Democracy Under the Imprint of COVID-19

Sheena Moosa, Aminath Riyaz, Raheema Abdul Raheem, Hawwa Shiuna Musthafa, Aishath Zeen Naeem

The Maldives National University

Corresponding author: Sheena Moosa, The Maldives National University, Rahdhebai Hingun, Malé, Maldives. moosa.sheena@gmail.com

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v13.i2.7548

Article History: Received 22/12/2020; Revised 05/05/2021; Accepted 15/06/2021; Published 19/07/2021

Abstract

Social value orientations (SVOs) of a society determine peoples’ behaviour and are critical for young democracies in crises. This paper draws on the Maldives Values in Crisis survey, conducted during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. SVOs assessed using the Schwartz Personal Values Questionnaire shows that Maldivian society weigh slightly towards prosocial. Urban-rural, age, and gender determine the SVOs on the dimension of Openness to change versus Conservation while age and gender determine the SVOs on Self-enhancement versus Self-transcendence dimension. Confidence in the public institutions were moderate and not associated with the SVOs. The moderate level of SVOs and confidence in institutions reflects the democratic landscape of the country. Although prosocial SVOs are favourable for implementing containment measures of the pandemic, without a strong value orientation towards conservation and self-transcendence, and confidence in the institutions, the country faces the risk of non-compliance to measures and escalation of the crisis.

Keywords

Social Value Orientation; Pandemic; Public Confidence; Prosocial; Democracy; Maldives

Introduction

Social value orientations (SVO) determine how people judge situations and behave in a social setting. Predominant SVOs of a society provide meaning to the attitudes and behaviour with regard to family and institutions, development and democracy (Inglehart and Baker 2000; Inglehart and Welzel 2005; Welzel 2013; Welzel and Alvarez 2014; Alemán and Woods 2016). As such, SVOs are critical for the society’s wellbeing. Theoretical perspectives on SVOs suggest that the development of social values is a slow process initiated during the formative years of socialisation which are internalised by adulthood and remain stable for one’s life (Inglehart and Baker 2000; Robinson 2013). However, it has been posited that short-term adjustments occur in response to situational changes during the life course (Kuczynski, Marshall and Schell 1997; Pailhé et al. 2014). Based on this understanding, rapid changes in SVOs are unlikely under usual circumstances, but adaptations are likely in the unusual circumstances of a pandemic. This position has significant implications in a crisis situation, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where containment measures limit democratic rights of the people and challenge the predominant SVOs (Alford 2017).

The coronavirus pandemic of COVID-19 is hailed as a crisis unlike any other the world has seen in recent decades and presents a considerable challenge to global public health and the economies (Musthafa et al. 2020; Wolf et al. 2020). To contain the virus, many countries declared a state of emergency and exercised governmental and administrative overreach and enforced restrictive measures such as lockdowns, curfews, forced business closures, cancellations of public gatherings including religious congregations (Thompson and Ip 2020; Riyaz et al. 2020). Such measures override civil liberties and fundamental freedoms; and the state of emergency has the potential for governments to exercise disproportionate emergency measures, failure to engage in proper deliberative and transparent decision-making, and even the suspension of effective democratic control (Frantz 2018). Therefore, COVID-19 pandemic control measures imposed by the governments have the potential to be viewed as authoritarian and can lead to non-compliant behaviour, disruptive to the desired outcomes in societies that have higher openness to change and lower conservation values (Bardi and Schwartz 2003). However, attitude and behaviour are largely driven by the SVOs and it has been shown that societies with high conservation values and ‘uncertainty avoidance index’ have high compliance to movement restrictions and physical distancing measures (Huynh 2020). Wolf and colleagues (2020) suggest that motivations for compliance with regulatory measures and behaviour towards supporting others is moderated by the predominant SVOs; hence, framing containment measures relevant to the SVOs is particularly important in the current pandemic situation.

Considerable similarities have been observed in the value orientations of societies across different countries across the world (Schwartz and Bardi 2001). Nevertheless, it is acknowledged that contextual factors such as historical experiences, economic advancements, human development and capitalism have been shown to shift the prevalent social value orientation in societies (Schwartz 2005; Abdollahian et al. 2012; Shahrier, Kotani and Kakinaka 2016), raising questions about the stability of value hierarchies across cultures. Collectivistic cultures, where the identity of the individual is perceived as part of the larger whole (e.g., family, society), and where social functioning is dependent on an arrangement of mutual obligation towards each other, may have orientations that place greater emphasis on more conservative values (Różycka-Tran et al. 2017; Schwartz and Bardi 2001). Findings from collectivist societies of Asia, Africa and Pacific indicate values such as security, conformity and tradition as being more important than openness to change and self-enhancement values (Joseph 2015; Różycka-Tran et al. 2017). They also place higher ratings on benevolence value types, which might be attributed to the fact that individuals’ sense of identity is embedded into ethnic, local or familial contexts, where the benefit of the in-group is considered to take precedence over individual interests (Saffu 2003). These findings, however, need to be regarded with caution since they do not account for the heterogeneity of the population of a country and the multiple cultural groups that exists within a society. For instance, comparative analysis of the Pacific island societies shows diverse cultural practices and norms between different islands and within the same island (Norton 1993; Meyer and Fourdrigniez 2019).

Another related factor that influences value orientations is religiosity of the people. Kuşdil and Kağıtçıbaşı (2000) observed that people with low religiosity gave higher ratings to openness to change as compared to high religiosity groups. At the same time, people with strong commitments to religion were found to favour self-transcendence values such as benevolence, but not universalism; and gave lower importance to hedonism and self-enhancement values such as achievement and power (Saroglou, Delpierre, and Dernelle 2004). Other studies have observed that universalism was negatively associated with religiosity in the mono-religious societies of the Mediterranean countries (Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Israel), but there was no association with religiosity in secularised and pluri‐religious countries such as Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands (Saroglou et al. 2004). These findings suggest that, there is a complex interplay between historic, developmental, cultural context and how religion is expressed in the society that impact on the predominant value orientations.

Maldives is a mono-religious Muslim country and can be considered a collectivist society with pressures upon individuals to follow the cultural norms of the society (Sadiq 2011). The limited research evidence does not place the Maldives populace in either end of the spectrum of collectivism versus individualism, however, it alludes to a collectivist mind-set that places communal over personal goals (Abdulla 2019). Although hierarchically organised families may not be common in Maldivian societies, it is quite typical for extended families to live together and contribute financially and emotionally to extended family members (Moosa 2019). Despite this, a previous study on cultural values in the country showed a high score on individualistic value dimensions and suggested that ‘while Maldives is a close-knit society with extensive relationships within and between families, the remoteness of the islands has compelled individuals to rely on themselves’ (Sadiq 2011, p. 8). Furthermore, Maldives, in the last decade, has moved towards a full democracy at a rapid pace and the democratisation process continues to be fragile, with continuing allegations, mistrust and contest for boundaries of the executive, parliament and judiciary (Faizal 2013; Zubair 2013; Naseem, 2020). The stages of democracy have also been associated with value orientations, with those societies that lean towards openness to change and self-enhancements having more democratic processes and institutions (Schwartz 2014).

The government of Maldives imposed a lockdown in the central areas of the country and closed the country’s border in April 2020 with the detection of first case of COVID-19 (MED 2020). The full lockdown lasted 45 days and the government continues to levy restrictive interventions to contain and control the disease and mitigate the impact of the pandemic (Suzana et al. 2020). These include curfews, movement monitoring for contact tracing, limitations on public gatherings, compulsory wearing of masks while in public places, and state sanctioned penalties on those who infringe on the restrictive measures (Usman, Moosa and Abdullah 2021).

While these interventions are being implemented, there still exists a gap in systematic exploration aspects of values of the Maldivian society to inform judgements about the possible behaviour of the society. Furthermore, how Maldivian value orientations pan out in a crisis has not yet been studied. Our hypothesis postulates that existential threats in the pandemic situation cause value shifts into a protective direction that would drive people to place greater emphasis on conservation values that result in higher motivation for compliance with containment measures. Therefore, this paper explores the SVOs of the Maldivian society and its relationship to people’s behaviour and confidence in the institutions during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research methods

Measuring values. The study adopts a psychological measurement of values using the Schwartz values framework that identifies 10 personal values that are differentiated by motivation and the underlying goal (Schwartz 2005). In this framework, the values are noted to be dynamic where some values are congruent and others conflicting. The Schwartz values framework places these values in two higher order bipolar dimensions; openness to change versus conservation and self-transcendence versus self-enhancement (see Schwartz 2012 for a detailed description). The dynamic nature of the values in sitautions poses inherent methodological limitations with the quantitaive measurement in that some items such as hedonism relate to both openness to change and self-enhancement (Schwartz 2012). Despite these caveats, the methodology has been validated in a number of coutnry settings to examine the SVO at societal level (Schwartz 2012).

Value scales. The Schwartz values framework is operationalized in this study using the 21-item short version of the personal values questionnaire (PVQ-21) (Schwartz 2003). This instrument is selected as appropriate for this study as it is a conventional instrument that has shown good reliability and validity in detemining the SVO at societal level in a number of studies across countries (Schwartz 2012). The PVQ-21 presents participants with 21 short descriptions of individuals who are defined in terms of their goals, aspirations and wishes. For example, ‘She/he looks for adventures and likes to take risks’, ‘She/he wants to have an exciting life’ measures stimulation. The respondents rate how similar the individual described in each scenario is to them using a six-point scale ranging from 1 (very much like me) to 6 (not like me at all). In this study, all items were reverse scored: higher numbers would indicate greater agreement with the item.

Other measures. The study also collected information on the public confidence in the government, health sector and public institutions as a whole, using single item questions on each of these variables measured on a Likert scale 1 to 4 (1=A great deal, 2=Quite a lot, 3=Not very much, 4=None at all). Single items were also used to measure the participants’ perception on how well they perceived the government was handling the Corona crisis with Likert scales 1 to 5 (1= poorly, 5= very well). Further, the participants’ perception on how well the people of the country were behaving under the imprint of the Corona crisis was sought with Likert scales 1 to 5 (1= very improperly, 5= very properly).

Data collection. The study draws on the data from the Values in Crisis (VIC) survey, with 1026 participants, carried out during the lockdown phase of the COVID-19 pandemic response in the Maldives. The study utilised a stratified probability sampling of residents in islands officially designated as cities (urban, n=433) and other islands of the Atolls (rural, n=593), further stratified by age and sex. More details of the sampling and data validity for VIC is provided by Riyaz and colleagues (2020) and additional findings from the VIC has also been reported (Musthafa et al. 2020).

Data cleaning. There were no missing data for the 21 items. Participants who responded with the same response to more than 16 items were removed from the analysis, as recommended in the instructions for PVQ-21 (Schwartz 2005). Hence, 208 participants (20.3% of the respondents) were dropped from the analysis. Therefore, the final data set consists of 818 participants (urban n=350, rural n=468).

Internal reliabilities. The reliability for this dataset (Table 1) is low for basic values and unacceptable for five basic values, but relatively good for higher order values, with the lowest being for self-enhancement. Schwartz (2003) notes that internal reliabilities of several PVQ indexes can be relatively low given the small number of items used to measure each of the ten values, and items for each are selected to cover the different conceptual components to increase the breadth of the meaning of the values, rather than choosing items with similar meaning.

Computing value scores. A score was computed for each of the ten basic and the higher order values by averaging participants’ responses to the items that constitute the value. Scoring followed the Schwartz’s instructions for the PVQ-21 (Schwartz 2003, 2005). The value indices were corrected by centring each individual’s responses to their mean response to all 21 items (Schwartz, 2005). Centring of value indices at the ‘within-individual level’ decreases the scale use response sets (respondents’ tendency to locate their responses on specific parts of the scale) and it enables scores that measure the relative (versus absolute) importance of values to the person to be generated (Schwartz 1996). Higher order values were computed by averaging participants’ responses to the items from the values that constitute it. The items correspond to Openness to Change: 1,11,6,15 (10,21); Conservation: 5,14,7,16,9,20; Self- enhancement: 2,17,4,13, Self-transcendence: 3,8,19,12,18 (see Schwartz 1996, 2005).

A score for the higher order bipolar dimensions, openness to change versus conservation dimension was obtained by subtracting the conservation score from the openness to change score. Similarly, a score for the self-transcendence versus self-enhancement dimension was obtained by subtracting the self-transcendence score from the self-enhancement score. The openness to change versus conservation dimension captures the conflict between values emphasizing ‘independence of thought, action, and feelings and readiness for change’, and values that emphasize order, self-restriction and resistance to change (Schwartz 2012, p. 8). The self-enhancement versus self-transcendence dimension, on the other hand, captures the conflict between values emphasizing ‘concern for the welfare and interests of others’ and values that emphasize ‘pursuit of one’s own interests, relative success and dominance over others’ (Schwartz 2012, p.8).

Quantitative analysis: Means of centred scores of the SVOs and higher order values are presented by gender, age group and urban/rural geographic categories of the sample. To explore the relationships between the SVOs and perceptions of public confidence on the government, health sector and public institutions as a whole, correlation tests were done using the score for each variable with the centred higher order value scores. Further analysis was done to explore whether the demographic variables age, gender and geographic residential area (urban or rural) determine the average position of the higher order values in the bipolar dimensions. Multivariate linear regression was performed for each dimension with the standardised coefficients representing the tendency towards the poles. To conduct this regression, computed scores for each of the bipolar dimensions that represent its position on the dimension were used as the dependent variable. Categorical variables, gender and urban-rural were coded as binary (0=males; 1=female; urban=0, rural=1).

Results

The SVOs of Maldivian society do not show a strong polarisation of values (Table 2). The population scores are above five for benevolence, security, conformity, tradition and universalism presenting a slight inclination towards conservation and self-transcendence values. Public confidence in institutions is also at a moderate level. About half of the respondents answered ‘a great deal or quite a lot’ to the question on confidence in the government (52%), health sector (57%) and public institutions as a whole (51%). Similarly, 52% felt that the government was handling the crisis well, but only 21% felt that most people in the society were behaving properly.

| Values | Total | Urban | Rural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Achievement | 4.06 | 1.30 | 3.95 | 1.31 | 4.14 | 1.29 |

| Benevolence | 5.38 | 0.98 | 5.39 | 0.96 | 5.36 | 0.99 |

| Conformity | 5.16 | 0.99 | 5.16 | 0.97 | 5.17 | 1.00 |

| Hedonism | 4.50 | 1.21 | 4.64 | 1.17 | 4.40 | 1.24 |

| Power | 3.64 | 0.98 | 3.60 | 0.96 | 3.67 | 0.99 |

| Security | 5.18 | 0.91 | 5.13 | 0.97 | 5.21 | 0.86 |

| Self-direction | 4.15 | 1.08 | 4.18 | 1.05 | 4.12 | 1.11 |

| Stimulation | 4.16 | 1.24 | 4.19 | 1.21 | 4.14 | 1.27 |

| Tradition | 5.13 | 1.01 | 5.13 | 1.02 | 5.14 | 1.00 |

| Universalism | 5.10 | 0.93 | 5.11 | 0.93 | 5.09 | 0.93 |

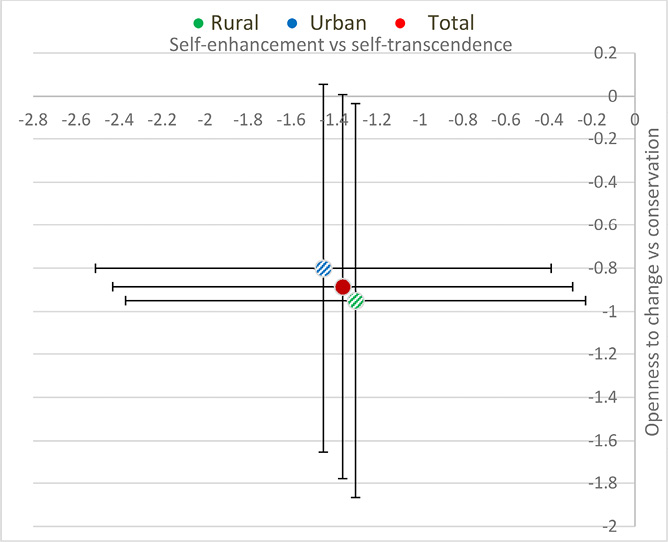

The scores for self-enhancement dimension versus self-transcendence dimension, on the horizontal axis of Figure 1 runs from -.29 to -2.43, with the average tendency below the neutral point zero, for the total sample as well as for urban and rural geographic categories. This indicates that self-transcendence is valued as more important than self-enhancement in the population as a whole as well as by those residing in urban or rural areas. The score for the openness to change versus conservation dimension, on the vertical axis, run from .008 to -1.86, with the average tendency below the neutral point zero. This indicates conservation is still valued more than openness to change by the population at large. On the dimension of openness to change versus conservation dimension, the mean for the population is -.886 (SD = .894); on the self-transcendence versus self-enhancement dimension, the mean is -1.362 (SD = 1.07). From the plot (Figure 1), the urban population weigh slightly more towards self-transcendence (Mean score for the dimension; urban: -1.45 (SD 1.06); rural: -1.30 (SD 1.07)) and openness to change compared to the rural population (Mean score for the dimension; urban: -.80 (SD .85); rural: -.95(SD .91)). However, there were no statistical differences in the scores between urban and rural.

Figure 1. Higher Order SVOs Dimensions Plot

The mean scores for openness to change and self enhancement are slightly higher for men compared to women (Table 3). On the dimension of openness to change versus conservation dimension, the mean score for males is -.768 (SD = .85) while for women the mean score is -.982 (SD = .92). For the dimension of self-enhancement versus self-transcendence dimension, the mean score for male is -1.20 (SD = 1.07) while for female the mean score is -1.49 (SD = 1.05).

The SVOs show small variations by age group with younger age groups weighing towards openness to change and self-transcendence (Table 3). This is also observed along the SVO dimensions where the score for openness to change versus conservation dimension are closer to zero among younger age groups compared to older age groups. On the self-enhancement versus self-transcendence dimension, the people in the older age groups weigh more towards self-transcendence compared to younger age groups.

While difference in the mean score was observed in the SVOs, for both dimensions by residential area, regression analysis (Table 4) shows that urban-rural residence, age and gender determine the value orientations on the dimension of openness to change versus conservation [p<0.05, OR-0.081, CI (-2.68_-0.25), p<0.01, OR -0.145, CI (-0.268_-0.025), p<0.01, OR-119, CI (-0.335_--0.092)] respectively. On the self-enhancement versus self-transcendence dimension, only age and gender determine the value orientations [p<.05, OR 0.071, CI (0.003_0.113) for age, p<.0.01 OR -0.132, CI (0-.430_-0.138) for gender].

There were no significant associations between the SVOs and people’s perceptions of how well the government was handling the crisis, confidence in the institutions, and people’s behaviour during the period of COVID-19 crisis (Table 5).

Discussion

Maldivian society leans towards prosocial value orientations; however, the society appears not to hold particularly strong orientations, with scores for the higher order SVOs clustering towards the middle of the scales as observed in the higher order SVO plot. The findings can be explained by the influence of economic advancement of the country and improvements in the economic and social situation of the people influencing changes in SVOs. This is consistent with the findings across countries, where a shift in SVOs has been observed with economic and human development (Abdollahian et al. 2012). Changes in value orientations occur with social changes and economic development, and people adjust their value orientations to the opportunities available in their environment and life changing events (Schwartz and Bardi 2001; Inglehart and Welzel 2005; Bardi et al. 2009). Although there are some geographic differences in the higher order SVO dimensions between those residing in more urbanised islands and those in smaller less developed islands, the differences are statistically significant only for the openness to change versus conservation dimension. In the Maldives, the urbanisation and its associated changes in family structures towards nuclear families contribute to this observation (Moosa 2019). Similar observations were found in Turkey, where nuclear families scored value orientations that favoured openness to change compared to those with extended families that favoured conservation (Kuşdil and Kağıtçıbaşı, 2000). Despite this, the lack of significant difference on the self-enhancement versus self-transcendence dimension suggests the complex interplay of factors that affect value change. One proposition is that Maldivian society is quite a mobile population – that is, those residing in the urban areas, particularly the capital, are temporary residents for the purpose of education and work and maintain traditional orientations (Hasan and Hynds 2014). This often results in some members of the family residing in their home islands and other family members residing on the capital island for the most part of the year, yet they maintain kinship relationships with family in the islands, allowing the maintenance of values developed during life stages.

While the Maldivian society has a prosocial orientation in general, the younger age groups and males appear to have SVOs that are less prosocial, scoring less on the conservation and self-transcendence values compared to older age groups and females. This mirrors the findings observed across 20 countries with older age groups and females having stronger prosocial orientations (Vilar, Liu and Gouveia 2020). Although the difference by age group observed in this study is minimal, it is significant and is reflected in the conservation versus openness to change dimension as well as self-enhancement versus self-transcendence dimensions. Globalisation and the country’s incremental development and dependency on global markets perhaps contribute to this transition in the SVOs of the Maldivian society. Berry (2008) observed that in the interconnected world, intercultural contact initiates change both at cultural and individual levels and the process of this change could have a number of outcomes from acculturation, assimilation, integration and separation or marginalisation. While some authors posit that at times of global crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, people are likely to revert to their original value orientations (Kurman and Hui 2011; Wolf et al. 2020), others suggest there is a short-term adaptation influenced by other contexual and psycho-social factors, rather than a shift of value orientations that influence compliance behaviour (Tabernero et al. 2020; Van Bavel et al. 2020). Following this argument, the compliance to pandemic containment measures reflects the short-term behaviour adaptation in the face of the crisis. Furthermore, studies have shown variations in the compliance behaviour is observed by the type of activity, duration of restrictions and positive or negative outcome of that experience, with higher compliance in short term and those with positive experiences (de Haas, Faber and Hamersma 2020; Reiger and Wang 2020). For instance, in the Netherlands working from home is seen as a positive experience while education from home is not (de Haas, Faber and Hamersma 2020). Despite these observations, it must be recognised that contextual factors including social and economic resources available to the societies are likely to affect compliance behaviour and the complex interplay between SVOs, contextual factors and compliance behaviour is an area that needs further exploration.

It is also proposed that during the crisis of a pandemic, motivating different segments of the population will require appealing to group similarities of different segments of the society (Wolf et al. 2020). Farias and Pilati (2020) suggested that men may see compliance as a sign of weakness, while younger individuals may not take the threat seriously. These factors are also influenced by the value orientations. Pandemic risk communications thus need to take into account the differences in SVOs in drawing support of younger age groups for compliance with the pandemic control and compliance measures.

During a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, trust in institutions is of paramount importance as it is related to people’s compliance with the containment measures put in place by the government, particularly when the interventions restrict people’s freedom and choice. Although the notion of trust may differ across contexts, trusting an institution implies that a person is confident that the institution is reliable and will act efficiently and fairly to serve the general interest (Morselli, Spini and Devos 2015). Institutions arguably allow for the maintenance of social order and stability in society whilst inadvertently curbing the constitutionally granted freedoms of individuals (Kragset 2009). By evoking a state of health emergency, governments have a legal framework to limit individual freedoms which in turn has the potential to be misused (Thompson & Ip 2020). Hence, it can be expected that institutions serve to reassure individuals who value security, whilst they may be perceived quite sceptically by individuals whose values align more with autonomy, and freedom of choice, as their liberties are potentially at risk (Devos, Spini and Schwartz 2002). Devos and colleagues (2002) found a significant positive association between trust in institution and the values of conservation such as security, conformity, tradition and power; there was a significant negative correlation with values of openness to change domain which includes self-direction, universalism, and hedonism. Similar pattern of results was also obtained by Morselli, Spini and Devos (2012) across three different cross-cultural datasets. Although the findings from the Maldives did not show a significant difference in trust in government and institutions by the different SVOs, the higher value orientation towards benevolence, security, conformity, tradition and uniformity correspond to conservation and self-transcendence orientations that are prosocial. It has been proposed that in societies with a predominant social focus, there is higher compliance with public health interventions imposed by the governments without the need for strict enforcement (Van Bavel et al. 2020; Wolf et al. 2020).

The socio-economic and political development level of the country also influences the level of trust and confidence in institutions and can reliably explain the between-country variance that is observed for the relationship between values and confidence in institutions (Morselli, Spini and Devos 2012). Maldives has experienced significant economic development and democratic change over a short period of time leaving profound tensions for political, social and economic clashes (Henderson 2008). It has been suggested that people’s value orientations are influenced by institutions and that institutional changes lead to changes in SVOs (Shi 2001). Dalton (2004) proposed the paradoxical view that trust in institutions and compliance with authority decline in wealthy countries with established democracies. Other studies have proposed that compliance to public health interventions in the wake of COVID-19 across societies is moderated by the predominant SVOs and confidence in institutions (Smith and Gibson 2020; Wolf et al. 2020).

Although, democracy in Maldives is still in its infancy, it has been hailed as a ‘liberal democracy in the Islamic world’ (Moorcmfi 2009, p. 249). The moderate level of SVOs across the values and confidence in institutions lends support to the argument that democratic change influences level of trust in institutions. Furthermore, the level of public confidence in national institutions is an indicator of social and political stability and is of importance during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Newton & Norris 2000). An erosion of public confidence in institutions is of concern in the COVID-19 crisis in the Maldives with almost half the study population reporting that they not having much confidence in the institutions, government and even the health sector. The level of confidence in the public institutions, perhaps reflect the changes in the national institutions and government with the democratic reforms of the last decade and the associated turmoil in the country (Zubair 2013). The level of trust and confidence in institutions is important for compliance with public health interventions, particularly when the measures for containing the epidemic impinge upon individual freedoms and rights with regard to movement and work (Han et al. 2020). However, this finding is not consistent with the assumption of the positive correlation of trust in government with compliance as other studies in the country reported high compliance to the government interventions of lockdown with movement control and have been suggested as a key factor in successful control of the COVID-19 first wave in the country within two months of lockdown (Moosa et al. 2020; Moosa and Usman 2020; Suzana et al. 2020). This further indicates that contextual factors significantly influence people’s behaviour irrespective of their SVOs. The findings are also confounded by the timing of the studies, as higher compliance to interventions was observed to be driven by the fear of the disease that was high at the start of the pandemic across the world (Harper et al. 2020). Other explanations for this could be methodological differences and instruments used in different studies that limit such comparison.

The COVID-19 pandemic at this stage in the country’s development poses profound uncertainty of people’s confidence in the government institutions. However, the findings suggest that, despite the tensions associated with the accelerated development, the social value orientations observed during the crisis continue to be prosocial and there is not a significant difference between those that hold individualistic values with regard to confidence in the government and institutions or the behaviour in relation to the public health measures. Thus, it remains to be investigated how these contextual variables affect the predictive power of values in determining an individual’s level of trust in institutions in the Maldivian society.

The SVO provide a useful context in pandemic response. Examination of SVO and compliance behaviour and death from COVID-19 in European countries indicated that Scandinavian countries with predominant prosocial orientations had significantly lower mortality compared to north European countries that have lower social focus in their value orientations (Ibáñez and Sisodia 2020). It has been proposed that countries with predominantly prosocial values can tap in to social responsibility and social compromise while societies with higher pro-self-values, such as high-power distance values, could rely on experts and public personalities focusing on autonomy and self-protection to achieve compliance with public health measures during the pandemic (Ibáñez and Sisodia, 2020; Leder, Pastukhov and Schütz, 2020). Since the SVO scores for the Maldives are not very high, even though they are predominantly prosocial, it indicates that risk communications for compliance will have to draw on a combination of strategies that rely on social responsibility and self-protection.

The findings of this study are limited by the timing of the data collection which was soon after the initial lockdown with the detection of the first case of COVID-19 in the country. Furthermore, it is not possible to make comparisons with SVOs prior to the crisis given the lack of prior comprehensive studies on values. Hence, the results may be confounded by the panic associated with the pandemic, which was starkly evident across the world. For instance, the findings did not find any significant difference of the SVOs with behaviour and confidence in situations, which could possibly be attributed to the uncertainty observed in the early stage of the pandemic. The findings of this study need further validation with additional studies as the epidemic progresses and after the ease of restrictions, during recovery.

Conclusion

Maldivian SVOs weigh towards prosocial, in the openness to change versus conservation dimension as well as on the self-enhancement versus self-transcendence dimension, reflecting the traditional collectivist social structures and culture, similar to a number of Asian societies. This meant that, in the face of the COVID-19 crisis, there were no significant differences on how people viewed public institutions, government response or their behaviour. These collectivist SVOs of Maldivian society meant compliance with public health interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic that enabled effective control of the first wave. However, the uncertainties and panic associated with early stages are more likely to have affected these behaviours. Urban and rural differences indicate changes in SVOs, particularly significant on the openness to change versus conservation dimension, hinting at effects of urbanisation and development that bring about significant life changes. The changes observed in SVOs by residential area, gender and age groups, along with the socio-economic and political situation of the country, need to be considered in risk communications to ensure continuity of compliance to public health measures as the pandemic has already lasted almost a year at the time of writing.

Acknowledgements

The authors make note of the support from the cross-country Values in Crisis (VIC) Survey team for sharing the protocol and instruments to implement the research in the Maldives.

References

Abdollahian, M.A., Coan, T.G., Oh, H. and Yesilada, B.A. 2012, ‘Dynamics of cultural change: the human development perspective’, International Studies Quarterly, vol. 56, no. 4, pp. 827-842. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2012.00736.x

Abdulla, F.N. 2019, ‘Silence in the islands: An exploratory study of employee silence in the Maldives’, Journal of Social and Political Sciences, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 777-789. https://doi.org/10.31014/aior.1991.02.03.118

Alemán, J. and Woods, D. 2016, ‘Value orientations from the world values survey: How comparable are they cross-nationally?’ Comparative Political Studies, vol. 49, no. 8, pp. 1039–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015600458

Alford, R. 2017, Permanent state of emergency: Unchecked executive power and the demise of the rule of law, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal.

Bardi, A. and Schwartz, S.H. 2003, ‘Values and behavior: Strength and structure of relations’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, vol. 29, pp. 1207–1220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203254602

Bardi, A, Lee, J.A., Hofmann-Towfigh, N. and Soutar, G. 2009, ‘The structure of intraindividual value change’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 97, no. 5, pp. 913-929. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016617

Berry, J.W. 2008, ‘Globalisation and acculturation’, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.04.001

Dalton, R.J. 2004, Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices, Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268436.001.0001

de Haas, M., Faber, R. and Hamersma, M. 2020, ‘How COVID-19 and the Dutch ‘intelligent lockdown’ changed activities, work and travel behaviour: Evidence from longitudinal data in the Netherlands’, Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, vol. 6, 100150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100150

Devos, T., Spini, D. and Schwartz, S.H. 2002, ‘Conflicts among human values and trust in institutions’, British Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466602321149849

Faizal, M. 2013, Civil Service in an Emerging Democracy: The Case of the Maldives. PhD Thesis, University of Wellington. http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/2832

Farias, J.E.M. and Pilati, R. 2020, ‘Violating social distancing amid COVID-19 pandemic: Psychological factors to improve compliance’, PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/apg9e

Frantz, E. 2018, Authoritarianism: What Everyone Needs to Know, Oxford University Press, New York. https://doi.org/10.1093/wentk/9780190880194.001.0001

Hasan, A.R. and Hynds, A. 2014, ‘Cultural influence on teacher motivation: A country study of Maldives’, International Journal of Social Science and Humanities, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 19–28. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJSSH.2014.V4.312

Harper, C.A., Satchell, L.P., Fido, D. and Latzman, R.D. 2020, ‘Functional fear predicts public health compliance in the COVID-19 pandemic’, International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 27 April 2020, pp. 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00281-5

Henderson, J.C. 2008, ‘The politics of tourism: A perspective from the Maldives’, Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 99–115. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/25378/1/MPRA_paper_25378.pdf

Huynh, T.L.D. 2020, ‘Does culture matter social distancing under the COVID-19 pandemic?’ Safety Science, vol. 130, pp. 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104872

Ibáñez, A. and Sisodia, G.S. 2020, ‘The role of culture on 2020 SARS-CoV-2 Country deaths: A pandemic management based on cultural dimensions’, Geojournal, 30 September 2020, pp. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-020-10306-0

Inglehart, R. and Baker, W.E. 2000, ‘Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values’,. American Sociological Review, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 19–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657288

Inglehart, R. and Welzel, C. 2005, Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790881

Joseph, J. 2015, ‘A values-based approach to transformational leadership in the South Pacific’, Community Development, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2014.971037

Kragset, A.O. 2009, Utopian Freedom: individual freedom and social order in Thomas More’s Utopia, Marge Piercy’s Woman on the edge of time and Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. Master’s thesis. University of Agder. Norway. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/225889626.pdf

Kuczynski, L., Marshall, S. and Schell, K. 1997, ‘Value socialization in a bidirectional context’,.in Grusec, J.E. and Kuczynski, L. (eds.), Parenting and Children’s Internalization of Values: A Handbook Of Contemporary Theory, Wiley, London, pp. 23–50.

Kurman, J. and Hui, C. 2011, ‘Promotion, prevention or both: Regulatory focus and culture revisited’, Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, vol. 5, no.3, pp. 1 – 16. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1109

Kuşdil, M.E. and Kağıtçıbaşı, C. 2000, ‘Value orientations of Turkish teachers andSchwartz’s theory of values’, Turk Psikoloji Dergisi, vol. 15, no. 45, pp. 59–76.

Leder, J., Pastukhov, A. and Schütz, A. 2020, ‘Social value orientation, subjective effectiveness, perceived cost, and the use of protective measures during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany’, Comprehensive Results in Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743603.2020.1828850

Ministry of Economic Development (MED) 2020, Rapid Livelihood Assessment: Impact of the COIVD-19 Crisis in the Maldives, Male’, Maldives: Ministry of Economic Development. https://www.trade.gov.mv/dms/708/1598369482.pdf

Meyer, J.Y. and Fourdrigniez, M, 2019, ‘Islander perceptions of invasive alien species: the role of socio-economy and culture in small isolated islands of French Polynesia (South Pacific)’, in Veitch, C.R., Clout, M.N., Martin, A.R., Russell, J.C. and West, C.J. (eds.), Island Invasives: Scaling up to Meet the Challenge. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, Gland, pp.510-516. http://www.issg.org/pdf/publications/2019_Island_Invasives/Meyer.pdf

Moorcmfi, P. 2009, ‘The Maldives: the strange case of Islamic multiparty liberal democracy’, in Salih, M.A.M. (ed.) Interpreting Islamic Political Parties, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp.249–258. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230100770_13

Moosa, S. 2020, ‘Social connectedness and wellbeing of ageing populations in small islands’, in Morese, R. (ed.), Social Isolation; an Interdisciplinary View, IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.85358

Moosa, S., Suzana, M., Najeeb, F., Abdul Raheem, R., Ibrahim, A., Riyaza, F. and Usman, S.K. 2020, Preliminary report : Study on socio-economic aspects of Covid-19 in the Maldives (Round One - May 2020). Maldives National University and Health Protection Agency. http://saruna.mnu.edu.mv/jspui/handle/123456789/7227

Moosa, S. and Usman, S.K. 2020, ‘Nowcasting the COVID-19 epidemic in the Maldives’, The Maldives National Journal of Research, vol. 8, no. 1,pp. 18–28. https://rc.mnu.edu.mv/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Nowcasting-the-COVID%e2%80%9119-epidemic-in-the-Maldives.pdf

Morselli, D., Spini, D. and Devos, T. 2012, ‘Human values and trust in institutions across countries: A multilevel test of Schwartz’s hypothesis of structural equivalence’, Survey Research Methods, vol. 6, no. 1,pp. 49–60. https://doi.org/10.18148/srm/2012.v6i1.5090

Morselli, D., Spini, D. and Devos, T. 2015, ‘Trust in institutions and human values in the European context: A comparison between the world value survey and the European social survey’, Psicologia sociale, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 209–222.

Musthafa, H.S., Riyaz, A., Moosa, S., Raheem, R.A. and Naeem, A.Z. 2020, ‘Determinants of socioeconomic experiences during COVID-19 pandemic in the Maldives’, The Maldives National Journal of Research, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 76-88. http://saruna.mnu.edu.mv/jspui/handle/123456789/8669

Naseem, A., 2020. ‘Democracy and Salafism in the Maldives: A battle for the future’, in Riaz, A. (ed.) Religion and Politics in South Asia (2nd ed.), Routledge, London, pp. 124-140. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429356971

Norton, R. 1993, ‘Culture and identity in the South Pacific: a comparative analysis’, Man, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 741-759. https://doi.org/10.2307/2803995

Pailhé, A., Mortelmans, D., Castro, T., Cortina Trilla. T., Digoix, M., Festy, P., Krapf, S., Kreyenfeld, M., Lyssens-Danneboom, V. and Martín-García, T. 2014, ‘Changes in the life course – state of the art report’, Families and Societies Working Paper Series 6. http://www.familiesandsocieties.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/WP6PailheMortelmansEtal2014.pdf

Rieger, M.O. and Wang, M. 2020, ‘Secret erosion of the “lockdown”? Patterns in daily activities during the SARS-Cov2 pandemics around the world’, Review of Behavioral Economics, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 223-235. https://doi.org/10.1561/105.00000124

Riyaz, A., Musthafa, H. S., Raheem, R.A. and Moosa, S. 2020, ‘Survey sampling in the time of social distancing: experiences from a quantitative research in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic’, The Maldives National Journal of Research, vol. 8, no. 1, pp 169–192. https://rc.mnu.edu.mv/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Survey-sampling-in-the-time-of-social-distancing-experiences-from-a-quantitative-research-in-the-wake-of-COVID%E2%80%9119-pandemic.pdf

Robinson, O.C. 2013, ‘Values and adult age: Findings from two cohorts of the European Social Survey’, European Journal of Ageing, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-012-0247-3

Różycka-Tran, J., Ha, T.T.K., Cieciuch, J. and Schwartz, S.H. 2017, ‘Universals and specifics of the structure and hierarchy of basic human values in Vietnam’, Health Psychology Report, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 193–204. https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr.2017.65857

Sadiq, A. 2011, ‘A study of the impact of national culture on transformational leadership practices in the Maldives’, AU Journal of Management, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 1–11. https://aujm.au.edu/index.php/aujm/article/view/60/46

Saffu, K. 2003, ‘The role and impact of culture on South Pacific island entrepreneurs’, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550310461045

Saroglou, V., Delpierre, V. and Dernelle, R. 2004, ‘Values and religiosity: A meta-analysis of studies using Schwartz’s model’, Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 721–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2003.10.005

Schwartz, S.H. 2014, ‘National culture as value orientations: Consequences of value differences and cultural distance’, in Ginsburgh, V. and Throsby, D. (eds.) Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, North Holland, Amsterdam, vol.2, pp.547–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53776-8.00020-9

Schwartz, S. H. 1996, ‘Value priorities & behavior: Applying a theory of integrated value systems’, in Seligman, C. Olson, J.M. &. Zanna, M.P. (eds.), The Ontario symposium: Vol. 8. The psychology of values, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 1-24.

Schwartz, S.H. 2003, ‘A proposal for measuring value orientations across nations’, in Questionnaire package of the European Social Survey, Chapter 7, pp. 259 – 319.. https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/methodology/core_ess_questionnaire/ESS_core_questionnaire_human_values.pdf

Schwartz, S.H. 2005, Human values, European Social Survey Education Net. http://essedunet.nsd.uib.no/cms/topics/1/

Schwartz, S.H. 2012, ‘An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values’, Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 919–2307. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116

Schwartz, S.H. and Bardi, A. 2001, ‘Value hierarchies across cultures: Taking a similarities perspective’, Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 268–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022101032003002

Shahrier, S., Kotani, K. and Kakinaka. M. 2016, ‘Social value orientation and capitalism in societies’, PLoS One vol. 11, no. 10, e0165067. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165067

Smith, L.G.E. and Gibson, S. 2020, ‘Social psychological theory and research on the novel coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pandemic: Introduction to the rapid response special section’, The British Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 571 – 583. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12402

Suzana, M., Moosa, S., Rafeeq, F.N. and Usman, S.K. 2020, ‘Early measures for prevention and containment of COVID-19 in the Maldives: A descriptive analysis’, Journal of Health and Social Sciences, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 251–264. https://doi.org/10.19204/2020/rlym10

Tabernero, C., Castillo-Mayén, R., Luque, B. and Cuadrado, E. 2020, ‘Social values, self-and collective efficacy explaining behaviours in coping with Covid-19: Self-interested consumption and physical distancing in the first 10 days of confinement in Spain’, Plos one, vol. 15, no. 9, e0238682. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238682

Thomson, S. and Ip, E.C. 2020, ‘COVID-19 emergency measures and the impending authoritarian pandemic’, Journal of Law and the Biosciences, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1-33. https://doi.org/10.1093/jlb/lsaa064

Usman, S.K., Moosa, S. and Abdullah, A.S. 2021, ‘Navigating the health system in responding to health workforce challenges of the COVID‐19 pandemic: the case of Maldives (short case)’, The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, vol.36, no. S1, pp. 182-189. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3136

van Bavel, J.J., Baicker, K., Boggio, P.S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M.J., Crum, A.J., Douglas, K.M. and Druckman, J.N. 2020, ‘Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response’, Nature Human Behaviour, vol. 4, pp. 460-471. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/y38m9

Vilar, R., Liu, J.H. and Gouveia, V.V. 2020, ‘Age and gender differences in human values: A 20-nation study’, Psychology and Aging, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 345-356. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000448

Welzel, C. 2013, Freedom rising: Human Empowerment and the Quest for Emancipation, Cambridge University Press, New York. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139540919

Welzel, C. and Alvarez, A.M. 2014, ‘Enlightening people, in the civic culture transformed: from allegiant to assertive citizens’, in Dalton, R.J. and Welzel, C. (eds.) The Civic Culture Transformed: From Allegiant to Assertive Citizens, Cambridge University Press, New York, pp.59–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139600002.007

Wolf, L.J., Haddock, G., Manstead, A.S.R. and Maio, G.R. 2020, ‘The importance of (shared) human values for containing the COVID‐19 pandemic’, British Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 618–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12401

Zubair, A. 2013, Challenges to the consolidation of democracy: A case study of the Maldives. MA Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California.