Literacy and Numeracy Studies: An international journal in the education and training of adults, Vol. 25, No. 1 2017

ISSN 1839-2903 | Published by UTS ePRESS | epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/lnj

RESEARCH ARTICLE (PEER REVIEWED)

Immigrant and Refugee Women’s Resourcefulness in English Language Classrooms: Emerging possibilities through plurilingualism

Julie Choi*, Ulrike Najar

Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne, Kwong Lee Dow Building, 234 Queensberry Street, VIC, 3010

*Corresponding author: Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne, Kwong Lee Dow Building, 234 Queensberry Street, VIC, 3010; julie.choi@unimelb.edu.au

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/lns.v25i1.5789

Article History: Received 10/11/2017; Revised 12/10/2017; Accepted 12/12/2017; Published 27/12/2017

Abstract

Citation: Choi, J. and Najar, U. 2017. Immigrant and Refugee Women’s Resourcefulness in English Language Classrooms: Emerging possibilities through plurilingualism. Literacy and Numeracy Studies: An international journal in the education and training of adults, 25:1, 20-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/lns.v25i1.5789

© 2017 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

Reports on refugee and immigrant women in Australia show these women have low literacy in their first language, limited English language abilities, and minimal formal schooling. With major funding cuts to the adult migrant education sector and persistent public ‘deficit views’ of immigrant and refugees’ levels of literacy, approaches to teaching and learning in this sector require flexible views of language that embrace plurilingualism as a valuable resource within and outside of the socially-orientated ESL classroom. In this article, we present and discuss our findings from a study in which we co-taught English to immigrant and refugee women in a housing estate in Melbourne, Australia, and investigated the effects of a plurilingual view on the women’s English language learning experience and communication skills. Drawing on recorded classroom dialogues, observation notes, and worksheets produced by the women, we demonstrate the extraordinary plurilingual resourcefulness immigrant and refugee women bring to the challenge of learning to communicate in English. Our aim is not to promote a particular teaching approach, but to suggest the value of ongoing critical reflection on the underpinning ideas of plurilingualism for immigrant and refugee learner groups such as those we experienced in our own classroom interactions.

1. Introduction

Eighty per cent of Australia’s refugee intake are women and children. Many of these women are the main caretakers of their young children as they rebuild their lives in Australia. Increasing reports show these women have low literacy in their first language, limited English language abilities, and minimal formal schooling (Islamic Women’s Welfare Council of Victoria 2005, Jenkinson, Silbert, De Maio and Edwards 2016, Milos 2011). The literature on immigrant and refugee women, particularly Muslim women, living in Australia also highlights issues related to discrimination, safety and trauma (Bartolomei, Eckert and Pittaway 2002). These women face significant barriers in developing connections with others, and experience a growing sense of shame, a lack of purpose, and emptiness in their lives.

While the learning of English alone cannot ‘fix’ problems such as race, culture and gender-based violence and victimization, English is connected to various facets of the struggles they face in rebuilding their lives. Greater competence in English is an important factor in rebuilding their lives particularly as English plays a major role in the shaping of their children’s identities as they grow up in Australia. However, in relation to learning English, numerous studies have shown contextual, physical, emotional, historical and personal challenges make it difficult for the women to commit to learning activities in any regular and sustainable manner (Deng and Marlowe 2013, Fozdar and Hartley 2013, Hauck, Lo, Maxwell and Reynolds 2014). Additionally, English language instruction for adult ESL migrants in Australia is often framed by ‘neo-liberal notions of functional literacy designed to enable the learner to function within the workplace’ (Atkinson 2014:8). While many women would like to work, with little, if any, support for childcare, workplace English is not high on their priority list. English language teaching and learning is thus complexly intertwined with a whole range of difficult societal issues, often communicated confusingly and inaccurately by policy makers and politicians. Australia’s immigration minister Peter Dutton, for instance, recently claimed that refugees are illiterate but are simultaneously taking jobs from Australians, and that those who are not working, are languishing in unemployment queues and health care systems (Bourke 2016). Claims, such as those by Dutton, although belied by evidence, exacerbate the image of refugees as linguistically deficient and a burden to society.

As English language teacher educators interested in finding ways of encouraging our teachers-in-preparation, the learners themselves and stakeholders to further move away from a ‘deficit’ lens, we designed a study that, through a participatory teaching approach, investigated the effects of a ‘plurilingual resourcefulness’ lens in the English language classroom for immigrant and refugee female learners. ‘Resourcefulness’, as Bezemer and Kress (2016) state, refers to ‘the resources developed in transformative engagement with the world and accumulated in a community over time’ and ‘a disposition on the part of members in their use of these resources’ (p. 130). By ‘plurilingual resourcefulness’ we are particularly focusing on the purposeful use of a variety of semiotic resources including multilingual, multisensory and multimodal elements as well as the ‘cooperative dispositions’ (Canagarajah 2013) that teachers and learners bring and negotiate together for purposes of learning and communication.

Developing such a plurilingual vision is challenging as it requires rethinking in both teachers and learners, the role of the first language (and other languages they may have acquired) in learning the target language. Despite numerous studies (Cummins 1984, García and Kleifgen 2010, Cenoz and Gorter 2015, Cook 2016) that show the value and necessity of drawing on learners’ existing knowledge of other languages, monolingual practices still prevail in language education (Lee and Oxelson 2006, Scarino, 2014). Secondly, although ‘bilingual support’ and ‘bilingual resources’ (usually referring to the need for teaching assistants who speak learners’ first languages), have traditionally been encouraged with adult immigrant and refugee learners in Australia (AMEP Research Centre 2007), focusing solely on the inclusion of learners’ first language is inadequate in understanding the complex semiotic resources learners need to draw on to learn a new language. Following Kress (2000), language is only one out of many semiotic tools for meaning making.

With increasing funding cuts, ‘bilingual support’ is unlikely to be sustainable. Teachers and learners need to take matters into their own hands, drawing on all available resources, to create their own meaningful learning opportunities. While literature on adult immigrant teaching strategies is abundant (see Auerbach 1992, Auerbach and Wallerstein 2004), we have seen little in the way of literature, if any, on the plurilingual resourceful ways in which groups of multilingual immigrant and refugee women can begin taking up a range of semiotic modes and practices for language learning and communication in English language classrooms. As Bezemer and Kress (2016) rightly point out, there are ‘real effects on what and whose semiotic work is to be recognised, particularly work that at present is often disregarded, may be ‘invisible’ and goes unnoticed, or is simply taken for granted’ (p. 130). A resourcefulness framework ‘rendering all means for meaning-making recognizable, and giving recognition to all kinds of agency, identity, knowledge and learning anywhere’ is crucial in making ‘noticeable, audible and visible some of what is currently unnoticed, inaudible and invisible’ (p. 130). In our own classes with immigrant and refugee women we set out to promote such plurilingual resourcefulness, in ways discussed below. Hence, the research question that guided this study was: What was the effect of plurilingual resources on the learning taking place in an immigrant and refugee women ESL classroom?

In this article, we present and discuss our findings from teaching English using a plurilingual stance to immigrant and refugee women over a period of 12 weeks from February to May 2016 in a housing estate in Melbourne, Australia. Drawing on recorded classroom dialogues, observation notes, and worksheets produced by the women, we show the extraordinary resourcefulness the women displayed in deploying a range of linguistic and extra-linguistic resources to communicate their thoughts and feelings within an English-medium context. Our aim is not to promote a particular teaching approach, but to suggest the value of understanding the underpinning ideas of plurilingualism for such groups of learners as we experienced in our own classroom interactions.

2. Conceptual Framework

Plurilingualism

Numerous studies in the field of Applied Linguistics have shown the merits in adopting a plurilingual vision in language teaching instruction (see Creese and Blackledge 2010, Conteh and Meier 2014, Mazak and Carroll 2017, Paulsrud, Rosén, Straszer and Wedin 2017, Choi and Ollerhead forthcoming). As an inclusive way of embracing linguistic diversity, the notion of plurilingualism rejects viewing languages as discrete and separate entities in bounded autonomous systems. Rather, languages operate in integrated and dynamic systems that consist of a totality of resources that individuals draw on to communicate meaning. Following Blommaert (2010) we refer to ‘resources’ as ‘the actual and observable ways of using language’ which include various types of semiotics, modalities, sensory cues, ‘ways of using language in particular communicative settings and spheres of life, including the ideas people have about such ways of using their language ideologies’ (p. 102). Such an epistemological understanding of language is centred not on ‘language’ as a static, ideological construct, but focuses on language usage. This shift is significant in discussions on language pedagogies as it enables us to view our learners not as ‘two monolinguals in one body’ (Gravelle 1996:11) but as ‘actors who signify differently by performing different language practices’ (García 2010:532). The lens we see their utterances through is not a lens of deficit but windows into different possibilities of how a whole set of knowledges and skills comes together to achieve communication goals.

Uncomfortable with the label ‘low language and literacy learners’ to describe the women in our group (as questions of what we actually mean by ‘low or fluent’ depends on the criteria we apply), we turn to Blommaert’s (2010) description of ‘truncated repertoires’ as a more precise way of framing our interpretations of their linguistic performances. Truncated repertoires denote a combination of resources derived from multiple languages, with some bits more developed than others. All speakers, as he states, have specific language competencies and skills:

We can use particular genres quite acceptably, speak in the registers that are typical of some social genres quite acceptably, speak in the registers that are typical of some social roles and identities, produce the accents of our native regions, and deploy the schooled literacy of our education trajectories (p. 103).

The emphasis that ‘no one knows all of a language’ and that ‘there is nothing wrong with that phenomenon of partial competence’ (p. 103) is a powerful insight that constantly reminds us to hold a critically reflexive position in what we count as correct and feel is necessary to be successful communicators in Australia. It is useful to keep in mind Canagarajah’s (2007) statement in reference to the pragmatic strategies used by students of English,

[p]articipants…’do their own thing’, but still communicate with each other. Not uniformity, but alignment is more important for such communication. Each participant brings his or her own language resources to find a strategic fit with the participants and purpose of a context’ (p. 927). Our capacity to ‘achieve alignment’ explains ‘how we can use resources that are disparate, incomplete, and even conflictual, and systems that are not tight, whole, or uniform, and still communicate. (Canagarajah 2013:32).

Many adult immigrant and refugee groups have experienced extraordinary histories in multiple geographical locations picking up chunks of plurilingual resources and ‘working’ them to achieve their communication goals. Classroom interactions and language exchanges are naturally entangled in a web of semiotic, multimodal, and multisensory resources, such as the use of various languages, cultural knowledge, gestures, electronic devices, the Internet, and affective responses to communicate meaning. It is this understanding of language and interactions that we used in our study and that guided our view of the relevance of plurilingualism as a resource in the immigrant and refugee classroom. Locating English squarely in the centre, in isolation from other semiotics and modes of communication in studies on adult ESL learners, does not give us a concrete view of how language and other semiotic modes are used in their worlds. Furthermore, if the sole orientation towards English is our concern in a country such as Australia where institutional curricula revolve around criterion measures against some form of ‘standard English’, we are susceptible to see their usage of English in terms of deficiencies than different and complex ways in which different people organise their thoughts and ways of understanding the world. As we have learned through our study, the use of their resources is not an option or choice but a normal part of everyday life. How these resources unfolded in the classroom interactions will be illustrated in the analysis of the data to follow.

3. The study

3.1 Setting and participants

The twelve two-hour teaching classes took place in the first half of 2016 in the community activity room of the women’s housing estate in Melbourne’s northeast. We had a whiteboard, access to laptops and computers, the Internet, and several long desks we joined together to form one big table – all provided by the housing estate. Four to ten women with varying numbers of children joined our classes. With most of the women coming from Iran and the Horn of Africa, their language and literacy skills were diverse and spoken English varied significantly. We focus on three women, Jannah, Kotra, and Semira1, who actively participated and joined the classes regularly. Fig. 1 summarises their background information.

Figure 1 General profile details of the women in this study

3.2 Methodology

The method used was duoethnography, a participatory research methodology that is designed to study a certain phenomenon through in-depth conversations with another researcher (Sawyer and Norris 2013). In reflecting on our teaching and researching in post-class recorded conversations, we aimed to develop a shared meaning making process that not only involved the English language learning needs of the women but also the process through which we came to understand the learning that was taking place in class and the power relations that were part of it (see Najar and Choi forthcoming). Detailed qualitative analysis took place that was based on grounded theory (Charmaz 2006) and the recorded dialogues of the researchers. The processes of jointly discussing, note taking, and negotiating the material collected enabled certain themes to emerge from the data as well as the researcher dialogues.

We received ethics approval to record and publish this work from the community centre and the housing estate. The women were informed of the project and all (but one) women signed the consent forms. Classroom interactions were audio recorded and the women’s worksheets were shared with us for scanning purposes. Individually, we kept ongoing field notes throughout the week as we prepared for classes. After classes, we, as both the teachers and researchers of this study, held debriefing sessions on our reflections which we also audio recorded.

3.3 Syllabus, Resources Used and Teaching Approaches

In preparing the study, we consulted extensively literature on pedagogies in the area of low language and literacy adult English language learners. Experts in the field call for ‘social-contextual approaches’ (Auerbach 1989) based on a framework of ‘meaningful participation’ where identity and ‘the aspirations of learners and the unique social world which contextualises their learning’ (Atkinson 2014:8) is at the core of the pedagogy. Although functional agendas in curricula do have a place, a narrowly functional agenda can, as Roberts and Cooke (2009) point out, ‘flatten out interactional complexity’ (p. 620) and ‘fail to equip migrants to realise their full potential as users of English, members of the work force and future citizens’ (Cooke 2006:56). Materials need to ‘exemplify the social relations and discourse routines of everyday and institutional interactions’ (Roberts and Cooke 2009:620) and while the availability of such research based materials are still scarce, resource packages such as Talking Shop: A curriculum sourcebook for participatory adult ESL (Nash, Cason, Rhum, McGrail and Gomez-Sanford 1989) and Reflect for ESOL (Reflect 2007) created specially to provide teachers with a variety of themes and activities pertinent to adult immigrant lives, have influenced our own pedagogical approach.

In line with many of the ideas on pedagogical approaches advocated for family literacy programs, we used a participatory framework, which has ‘meaningful participation’ at its core. Applying a participatory framework meant there were opportunities for the women to feel free to tell us what they wanted to learn on an ongoing basis from suggestions on weekly topics to the level of words or expressions. However, we realised it was not as simple as we thought in having them tell us what they wanted. Early in our study, we began by asking the women in a questionnaire ‘what do you want to learn through these English lessons?’, and we received a combination of very general answers:

‘reading-writing-speak’, ‘speaking English’, ‘read write speakspoke’, ‘reading, wrighting, speaking, ‘spelling, Wrtling, Talking’, ‘Writing, speak, speekin, how to read an write’, ‘to speac english, Speaking, Writing’, ‘any things, mostly speaking and grama’. (Morning tea questionnaires, 18 February 2016)

While language proficiency may be one reason for not being able to express any specific desires, as marginalised speakers of English who have had minimal formal schooling experience, there are limits to what one can say in response to such a question. In casual conversations that occurred in class, we learned they themselves might never have thought about what they would do or who they could be using English. While asking about what they would do if they had more free time, Semira replied, ‘I study. But in here I’m not sure what job, what study I can do in English.’ While we eventually chose topics ourselves (which made our overall approach only semi-participatory), we aligned these with classroom conversations and issues that revolved around childcare education and health needs (see Fig. 2). The women gradually became vocal about what skills they wanted to develop such as wanting to learn how to use certain words, grammatical constructions, the use of computers, and being able to respond appropriately in everyday socio-cultural situations.

Figure 2 Twelve-week syllabus topics

There were no set textbooks used. We chose visual texts displaying particular situations (e.g. a parent speaking to a teacher, portrayals of various roles of women in the media, bullying in schools), photographs (e.g. of our own families, which also naturally led to them showing us photos of their families stored in their phones), simple charts with grammatical rules, and homework sheets with language exercises or simple logs of their daily activities (see Fig. 3). As language teachers who are interested in the sociocultural orientation to literacy that takes seriously the relationship between meaning and power found in ‘critical literacy’ approaches (Janks 2012, see also Muspratt, Luke and Freebody 1997), our pedagogical motives in using these texts were to activate the women’s knowledge and experiences in order to explore issues of power relations and assumptions that are involved in everyday life. This blend of approaches enabled us to put meaningfulness at the core of our interactions allowing for a variety of semiotics to become visible and audible.

Figure 3 Week 1 Homework: Semira’s ‘My daily routine diary’. [Transcription] Morning: I clean my home and I make breakfast for my kids; I go out for shopping; I listen Quran in Arabic Afternoon: I read Quran in Arabic language

4. Plurilingual resourcefulness in immigrant and refugee English language classrooms: Three emerging possibilities

In this section, we use extracts from classroom conversations to illustrate where the women communicated meaningfully with the help of plurilingual resources. By doing so we discuss our underlying views of plurilingualism, how these views were enacted in our classroom interactions with the women, and the possibilities for language and literacy development we saw in the ways in which the women’s resourcefulness enabled real-life stories and individual needs to emerge. Overall and throughout the course, three themes emerged that were particularly related to the women’s use of multiple languages in class: these are 1) the enabling of the formation of a ‘group connection’ and of, what Davies (2016) calls ‘emergent listening’, a different kind of listening from ‘listening-as-usual’, a mode of listening that ultimately ‘uphold[s] the normative order’ by ‘presum[ing] it knows already what anyone might say or mean; ‘emergent listening’ is actively engaged in the formation of selves within already known categories’ (p. 73); 2) making way for digital literacy skills; and 3) the creating of possibilities for plurilingual literacy development. The following sections unpack and illustrate these points in more detail.

4.1 Enabling ‘emergent listening’

The relevance of a cooperation between the women and the formation of a ‘group connection’ became relevant when we first witnessed Semira’s engaging speaking performance during a conversation about her use of English in a shopping scenario. The urgency that embodied the utterance of her words, and the clear and creative gestures she used to clarify and animate meaning for all the group members immediately came to our attention. The following extract exemplifies how her gestures and plurilingual resources merged with the resourcefulness of the other women present in class.

Extract 1: Semira, Kotra, Jannah, and Julie are talking about where Semira goes shopping for food (Week 2).

As Semira becomes increasingly more animated, the interaction progresses with everyone’s admiring reactions (lines 15, 23, 25) and wordy explanations are not enough anymore to capture the activity of grabbing as many avocados as possible before they are all sold out. Semira uses an imitative sound (‘wah wah wah’) making gestures of taking the avocados by creating the hanging fabric of her hijab into the shape of a basket (lines 27-29). Jannah understands her gestures clearly and there is a synchronous burst of laughter amongst everyone (lines 29-31). Contrary to some views that see immigrants as unable or unwilling to communicate with unfamiliar others, the linguistic moves shown here emphasise the importance of the ‘cooperative dispositions’ the women bring to classroom spaces, that is, their ‘tastes, values, and skills that favour co-existence with others’ (Canagarajah 2013:176) they would have likely developed through their ‘socialization in multilingual environments and contact zones’ (p. 178). This cooperative disposition for us is embodied by an affective openness to each other, listening to each other not ‘in order to fit what we hear into what we already know and to judge it accordingly’ (Davies 2016:78), but the kind of listening that uses all one’s senses - a listening that opens up the not-yet-known, where something new has the potential of emerging, what Davies (2016) calls emergent listening. This emergent kind of multisensory, affective engagement made our classroom spaces more than simply a place for learning English but a space for sharing stories, laughter, meaningful contact and connection.

4.2 Making way for digital literacy skills

Another theme that emerged from the data revolved around the use of digital tools and electronic devices, that, in combination with various languages, multiple semiotics and sensory cues lead to the formation of digital literacy skills. The women all had iPhones, some with and without Internet connection and translation apps that were downloaded during our period together. However, until the third week, the women were reluctant about using their phones to look up information themselves. Sometimes we used our own phones or the housing estate’s laptop asking them to insert words in Persian and then copying and pasting those words into Google to find images, reminding them that even if words are not always spelt perfectly, we would still be able to find a word or an image we are looking for. For instance, Kurdish, Arabic, and some Persian were used to translate unfamiliar words, topics, and instructions to each other. The following extract exemplifies how plurilingual resourcefulness unfolded in collaboration with digital tools during a conversation on religion with Jannah and Semira.

Extract 2: Julie is talking about the usage of the words ‘choice, choose and chose’ which has led to a conversation on religion (Week 8, narrations in italics derive from fieldnotes)

The deficit connotation embedded in the label ‘low language and literacy learner’ obscures the resourcefulness multilingual women such as Jannah can bring to a discussion. Jannah expresses the choices Muslim women in Iran can make with various Arabic words and gestures of the choices in lengths and sleeves of the dresses (lines 32-38), which perfectly accompanies her main point that everyone is different in the choices they make (lines 26-28, 38). However, the plurilingual resources she uses draw not only on language and visible gestures. Having spent some time with Jannah, we have developed some understanding of the tone of her laughter, which varies from signalling friendly greetings or exchanges, full understanding, confusion, and resistance. Her shrugs give us indications of her uncertainty, confusion, frustration, or simply that the topic isn’t worth all the effort for her to speak at different points in time. But these semiotic forms of expressions are not just tactics for her own survival, they are also deployed cleverly to mediate tense situations (i.e. the interjection of her laughter, lines 21-22) and more significantly, in diplomatic ways that do not take sides but skilfully and resourcefully bring to the fore her own position (i.e. that everyone has a choice). Her interjection also effectively ‘rescues’ what is becoming an awkward conversation between Julie and Semira (lines 18-19).

While it is valid to assume people will become silent when they do not have high levels of language to express their views to their satisfaction particularly in difficult and contentious topics such as in speaking about one’s religious beliefs, it is also incorrect to assume people will stay silent until they have acquired ‘enough’ grammatical and lexical knowledge in order for communication to become possible. Referring back to Canagarajah’s (2013) point on ‘alignment’, it is not ‘grammatical competence, but performative competence, that is, what helps achieve meaning and success in communication is our ability to align semiotic resources with social and environmental affordances’ (p. 32). Encouraging the drawing on all of the resources they already have available in their immediate contexts does much more than simply communicating ideas; it enables an open space where women feel they can participate plurilingually in discussions they feel are important and in ways they are comfortable performing.

4.3 Possibilities for plurilingual literacy development

Another key point that repeatedly came to our attention was the relationship between the formation of literacy skills and the use of plurilingual resources which the women already brought into the classroom. In particular Jannah’s development was surprising. As an asylum seeker whose application for residency has been rejected several times, her utterances were usually in reference to her sense of depression and anxiety related to her legal status of being stateless as expressed by her statement below:

Australia, me, depress, stress, everything, every day. Visa and my two big son, very stress me. No work, sometime fighting at home. Fighting with father. Stay home all day. I think home, stress! [Julie: You need friends.] Frie…nds! No friend. Very depress, very very depress. No talk. Just watching TV. Watch Iranian TV, watch film. All day cooking, cleaning. Son, me “Mom go to Iran”. Very depress.

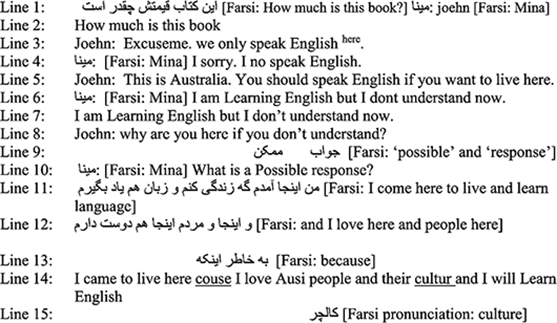

While Jannah only used Kurdish at home with her family, she was mentally in a state of preparation, thinking that once her application gets successfully processed, English will come in handy. For Jannah, English is closely tied to the desire for citizenship, for a sense of safety that will come from legal protection. Fig. 4b and the adjoining figure following below (Fig. 5) are worthy of examining more closely as they capture the plurilingual process of Jannah’s plurilingual literacy development. Adapting an activity on literacy and critical thinking in everyday life we found in Talking Shop: A curriculum sourcebook for participatory adult ESL (Nash et al 1989), we gave the women a short dialogue of arrogance and racism in English with two blank sentences where we asked them to translate ‘how much is this book?’ and ‘what did you say?’ in Persian (see Fig. 4a) which took them a great deal of negotiation to figure out before they wrote the Persian script. They were then asked to write their own final response at the end of the dialogue. Jannah came back with the following dialogue (see also original writing in Fig. 4b).

Figure 4a Activity on literacy and critical thinking in everyday life discussed in class and completed as homework

Figure 4b Jannah’s response to the task and final draft submitted to us

Extract 3: Transcription of Fig. 4b [brackets English translation of Persian]

When Jannah handed in her work she originally only gave us the final version above (Fig. 4b) but we happened to see another crumpled-up piece of paper hanging out of her bag. It was a draft version of Fig. 4b. In this draft version (Fig. 5), she copies the original text, looks for Persian translations of new words such as ‘possible’, ‘response’, ‘cause’, writes the sounds equivalent in Farsi such as ‘caltar’ [culture], writes and rewrites Mina’s part changing the original script (see Fig. 4a) from ‘I no understand’ to ‘I don’t understand now’ which she writes twice (Fig. 5, lines 6-7), the second time in a neater format. She tries writing her ideas in Farsi (lines 11-12), then rewrites the sentence in English (with help from her son) joining the ideas together. She then transfers what she has created neatly onto the final homework sheet. It is important not to lose sight of the effort and desire that goes into producing these texts. The performance of such practices and dedication show us development of new scholarly skills currently in process, her eagerness to study and produce ‘good’ work, and the capacity to become someone other than she was before. The use of her plurilingual resources played an important part in producing this first draft of the text, as shown below.

Figure 5 Jannah’s draft version before submitting final draft above in Fig. 4b)

Extract 4: Transcription of Fig. 5

As shown here, a critical literacy framework and plurilingual strategies stimulate and enable possibilities for language, literacy and identity development to emerge. The resources she draws on and the strategies she uses are not uncommon in the ways many language learners learn new languages or navigate their everyday worlds. However, for learners such as Jannah who have left the formal educational scene many years ago, finding out what she can do and explicitly communicating the plurilingual resources she has available can make a meaningful difference in developing a voice (i.e. her point of view) in English. In this case, a critical voice, seeing the dialog is fundamentally set up to critically engage with and respond from different power positions.

5. Discussion

Following and Freeman Field (2010), we are not interested in ‘the quest for the best model’, rather in, ‘a set of principles that underlie quality schooling for all bilingual learners, and select approaches that are realistic for our particular teaching and learning contexts’ (p. 108). Reflecting on our experience here, we believe an approach that views plurilingualism as a resource for learning is an invaluable way of moving away from a deficit view and instead, productively engaging both teachers’ and learners’ various semiotic resources for the purposes of effective teaching and learning. As our data analysis shows, the use of a variety of plurilingual resources opens up possibilities for the women to engage in meaningful listening, speaking and writing activities in English language classrooms, that are based on real-life and socially-relevant scenarios. For those who are in precarious and vulnerable legal situations, such possibilities, enabled by drawing on the resources they have available, can be the very threads that sustain their sense of hope and survival as they work towards rebuilding their lives in a new country. Thus, following Bezemer and Kress (2016), we believe a focus on the use of specific resources ‘deserve to be made explicit and given serious attention’ (p. 131) in research on learning and communication. Furthermore, we learned about our need to lean into their spaces, listening to the women carefully without our pre-conceived presumptions, allowing the conversations to go in directions where opportunities to show us what they can do might become possible.

Our research set up where teaching and researching were conjoined allowed us to interact with the women in close proximity where we gained a much more accurate understanding of the advanced levels of knowledge and capacities they bring to their performances in English (i.e. broad knowledge of content words, ability to rephrase, translate, and perform in animated ways as seen in Extract 1 and participate in challenging conversations as shown in Extract 2). As teacher-researchers thinking about how communication works in these spaces, we began to understand how multisensory understandings (such as the different functions and volumes of laughter, Extracts 1 and 2) can easily fall through the cracks in our documentation if we observe from a distance. An exclusive focus on English is likely to miss the simultaneous translations and processual work learners do in looking up information using devices (Extracts 2, 3 and 4). We may also not be able to get hold of valuable information such as Jannah’s crumpled up piece of paper that contained processes of her language and literacy development. In line with our understandings of plurilingualism we outlined earlier, we understand ‘none of us speaks “a language”, as if this were an undifferentiated whole’, rather, as we have seen in Jannah’s critical, plurilingual literacy development, ‘we engage in language practices, we draw on linguistic repertoires, we take up styles, we partake in discourse, we do genres’ (Pennycook 2012:98).

However, learners may not always see plurilingual strategies or resources as preferable or conducive to learning. As the only non-Kurdish or Persian speaker, Semira often lectured the other women to stop using their other languages so that they could use classroom time to speak as much English as possible. In principle, the other women agreed, but in practice, the women could not, or perhaps found it pointless to not involve their first languages since they were able to follow the lesson more efficiently when they could help each other with explanations using Kurdish. Although Semira can feel left out in these moments, she too benefits from Jannah’s plurilingual repertoire in keeping the conversation going when the dynamics are changed and other Kurdish speakers are not present (as shown in Extract 2). In our view, policing plurilingual speakers’ multiple ways of creating meaning is an unnecessarily awkward and futile act seeing much more can be communicated, shared and understood between members who only have a limited amount of time each week to meet. However, in reflection, we also realise we never explicitly discussed the benefits of drawing on different resources for learning purposes with the women, and now understand such a discussion to be valuable and crucial in deploying a plurilingual approach in adult immigrant teaching and learning contexts.

Although we recognise the various obstacles in implementing a plurilingual vision in contexts where English is the majority language, we firmly believe a bilingual stance as de Jong and Freeman Field (2010) point out, ‘is always possible and desirable from a social justice perspective because it aims to validate the linguistic (and cultural) resources of students and their families’ (p. 110). However, developing such a stance requires a deep level of understanding of the very notion of ‘language’, and an articulation of the goal of language education in an increasingly complex world. As Canagarajah and Liyanage (2012) state, ‘what we need is a paradigm shift in language teaching. Pedagogy should be refashioned to accommodate the modes of communication and acquisition seen outside the classroom’ (p. 58). Without a strong foundational understanding, discussions among learners, teachers and pedagogues around strategies and plurilingual resources will remain at the level of having a few neat techniques that do little more than show teachers are ‘cool’ with linguistic diversity, or as Kramsch (2014) puts it, ‘surfing diversity, not engaging with difference’ (p. 302).

Conclusion

There is an urgent need to redress teacher education in the area of adult English language education that has at its core, a ‘more reflective, interpretive, historically grounded, and politically engaged pedagogy’ (Kramsch 2014:296, see also Freire 1970) in an era of globalization. We believe a plurilingual vision embodied by notions such as ‘emergent listening’, ‘digital literacy skills’, and ‘plurilingual literacy skills’ can lay a strong foundation for teachers and learners to work as partners in the co-construction of meaning. The use of multiple plurilingual resources may only be one piece in this very complex puzzle, but we hope we have shown how their use can open up certain possibilities for teachers and learners in discovering the ongoing needs of both parties as they are brought about through meaningful pedagogical encounters (Davies and Gannon 2009).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Emeritus Professor David Nunan for his constructive comments on an earlier draft, the reviewers for their feedback, Dr. Mahtab Janfada for the Persian translations, the community centre organiser, and the housing estate managers for their support.

References

AMEP Research Centre (2007) Course Planning for Pre-literate and Low-literacy Learners. (Teaching Issue No. 10). Retrieved from http://www.ameprc.mq.edu.au/docs/fact_sheets/Teaching_Issues_Fact_Sheet_10.pdf.

Atkinson, M (2014) Reframing Literacy in Adult ESL Programs: Making the case for the inclusion of identity, Literacy and Numeracy Studies, vol 22, no 1, pp 3-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/lns.v22i1.4176.

Auerbach, E (1989) Toward a Social-contextual Approach to Family Literacy, Harvard Educational Review, vol 59, no 2, pp 165-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.17763/haer.59.2.h23731364l283156.

Auerbach, E (1992) Making Meaning, Making Change: Participatory curriculum development or adult ESL literacy, Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, DC.

Auerbach, E and Wallerstein, N (2004) Problem-Posing at Work: English for Action, Grass Roots Press, Edmonton.

Bartolomei, L, Eckert, R and Pittaway, E (2002) “What Happens There … Follows Us Here”: Resettled but still at risk: Refugee women and girls in Australia, Refuge, vol 30, pp 45-56.

Bezemer, J and Kress, G (2016) Multimodality, Learning and Communication: A social semiotics frame, Routledge, Oxon.

Blommaert, J (2010) The Sociolinguistics of Globalization, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Bourke, L (2016, May 18) Peter Dutton says ‘Illiterate and Innumerate’ Refugees would Take Australian Jobs. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/federal-election-2016/peter-dutton-says-illiterate-and-innumerate-refugees-would-take-australian-jobs-20160517-goxhj1.html.

Canagarajah, S (2007) Lingua Franca English, Multilingual Communities, and Language Acquisition, The Modern Language Journal, vol 91, pp 923-939. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00678.x.

Canagarajah, S (2013) Translingual Practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations, Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203073889.

Canagarajah, S and Liyanage, I (2012) Lessons from Pre-colonial Multilingualism. In Martin-Jones, M, Blackledge, A, and Creese, A, eds, The Routledge Handbook of Multilingualism, Routledge, Oxon, pp 49-65.

Cenoz, J and Gorter, D, eds, (2015) Multilingual Education: Between Language Learning and Translanguaging, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Charmaz, K (2006) Constructing Grounded Theory: A practical guide, 2nd ed, Sage, London.

Choi, J and Ollerhead, S, eds, (forthcoming) Plurilingualism in Teaching and Learning: Complexities across contexts, Routledge, New York.

Conteh, J and Meier, G (2014) The Multilingual Turn in Languages Education: Opportunities and Challenges, Multilingual Matters, Bristol.

Cook, V (2016) Second Language Learning and Language Teaching, Routledge, New York.

Cooke, M (2006) “When I Wake Up I Dream of Electricity”: The lives, aspirations and ‘needs’ of Adult ESOL learners, Linguistics and Education, vol 17, pp 56-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2006.08.010.

Creese, A and Blackledge, A (2010) Multilingualism: A critical perspective, Continuum, London.

Cummins, J (1984) Bilingualism and Special Education: Issues in assessment and pedagogy, Multilingual Matters, Clevedon.

Davies, B (2016) Emergent Listening, In Giardina, M, ed, Qualitative Inquiry through a Critical Lens, Routledge, New York, pp 73-84.

Davies, B and Gannon, S, eds (2009) Pedagogical Encounters. Peter Lang, New York.

de Jong, E, and Freeman Field, R (2010) Bilingual Approaches. In Leung, C and Creese, A, eds, English as an Additional Language: Approaches to teaching linguistic minority students, Sage, London, pp 108–121. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446251454.n8.

Deng, S, and Marlowe, J (2013) Refugee Resettlement and Parenting in a Different Context, Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, vol 11, no 4, pp 416 - 430. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2013.793441.

Fozdar, F, and Hartley, L (2013) Civic and Ethno Belonging among Recent Refugees to Australia, Journal of Refugee Studies, vol 27, pp 126-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fet018.

Freire, P (1970) The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Herder and Herder, New York.

García, O (2010) Languaging and Ethnifying. In Fishman, J. and García, O, eds, Handbook of Language and Ethnicity: Disciplinary and regional perspectives, 2nd ed, vol 1, Oxford University Press, New York, pp 519–535.

García, O and Kleifgen, J (2010) Educating Emergent Bilinguals: Policies, programs, and practices for English language learners, Teachers College Press, New York.

Gravelle, M (1996) Supporting Bilingual Learners in Schools, Trentham Books, Stoke-on-Trent.

Hauck, F, Lo, E, Maxwell, A and Reynolds, P (2014). Factors Influencing the Acculturation of Burmese, Bhutanese and Iraqi refugees into American Society: Cross-cultural comparisons, Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, vol 12, no 3, pp 331- 352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2013.848007.

Islamic Women’s Welfare Council of Victoria (2005) Self-esteem, Identity, Leadership & Community, Islamic Women’s Welfare Council of Victoria, Melbourne, Victoria.

Janks, H (2012) The Importance of Critical Literacy, English Teaching: Practice and critique, vol 11, no 1, pp 150-163.

Jenkinson, R, Silbert, M, De Maio, J and Edwards, B (2016) Settlement Experiences of Recently Arrived Humanitarian Migrants, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne, Victoria.

Kramsch, C (2014) Teaching Foreign Language in an Era of Globalization: Introduction, The Modern Language Journal, vol 98, no 1, pp 296-311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2014.12057.x.

Kress, G (2000) Multimodality: Challenges to thinking about language, TESOL Quarterly, vol 34, no 2, pp 337-340. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587959.

Lee, J and Oxelson, E (2006) “It’s not my job”: K-12 Teacher Attitudes toward Students’ Heritage language maintenance, Bilingual Research Journal, vol 30, no 2, pp 453-477. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2006.10162885.

Mazak, C and Carroll, K (2017) Translanguaging in Higher Education: Beyond monolingual ideologies, Multilingual Matters, Bristol.

Milos, D (2011) South Sudanese Communities and Australian Family Law: A clash of systems, Australasian Review of African Studies, vol 32, no 2, pp 143-159.

Muspratt, S, Luke, A and Freebody, P (1997) Constructing Critical Literacies: Teaching and learning textual practices, Allan & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW.

Nash, A, Cason, A, Rhum, M, McGrail, L and Gomez-Sanford, R. (1989) Talking Shop: A curriculum sourcebook for participatory adult ESL, University of Massachusetts, Boston.

Najar, U and Choi, J (forthcoming) How do ‘We’ Know What ‘They’ Need? Learning together through duoethnography and English language teaching to immigrant and refugee women, in Stanley, P and Vass, G, eds, Questions of Culture in Autoethnography, Routledge, New York.

Paulsrud, B, Rosén, J, Straszer, B and Wedin, Å (2017) New Perspectives on Translanguaging and Education, Multilingual Matters, Bristol.

Pennycook, A (2012) Language and Mobility: Unexpected places, Multilingual Matters: Bristol.

Reflect (2007) Reflect for TESOL: English for speakers of other languages. Retrieved from http://www.reflect-action.org/reflectesol.

Roberts, C and Cooke, M (2009) Authenticity in the Adult ESOL Classroom and Beyond, TESOL Quarterly, vol 43, no 3, pp 620-642. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2009.tb00189.x.

Sawyer, R and Norris, J (2013) Duoethnography: Understanding qualitative research, Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199757404.001.0001.

Scarino, A (2014) Situating the Challenges in Current Languages Education Policy in Australia – Unlearning monolingualism, International Journal of Multilingualism, vol 11, no 3, pp 289-306. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2014.921176.