International Journal of Rural Law and Policy, No. 2, 2019

ISSN 1839-745X | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://ijrlp.epress.lib.uts.edu.au

ARTICLE (PEER-REVIEWED)

The emergence of ungoverned space in the British countryside

International Journal of Rural Law and Policy, No. 2, 2019

ISSN 1839-745X | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://ijrlp.epress.lib.uts.edu.au

ARTICLE (PEER-REVIEWED)

Kreseda Smith

Harper Adams University, Shropshire, UK. kresedasmith@harper-adams.ac.uk

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijrlp.2.2019.6555

Article History: Received 09/04/2019; Revised 19/05/2019; Accepted 15/06/2019; Published 06/08/2019

Citation: Kreseda Smith, ‘The Emergency of Ungoverned Space in the British Countryside’ (2019) 2 (special issues on Rural Crime) International Journal of Rural Law and Policy. Article ID 6555, https://doi.org/10.5130/ijrlp.2.2019.6555

© 2019 The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Police and farmers in Britain have differing views on the effectiveness and measures of effectiveness of the policing of rural and farm crime. Farmers are increasingly feeling abandoned by the police while the police are trying to resource rural policing against a backdrop of budget cuts, inadequate strategic guidance and a lack of understanding of the impact of rural and farm crime.

To obtain information on issues about farm crime, interviews were conducted with Police and Crime Commissioners and Crime Prevention Advisors across four rural police forces in England. Interviews and focus groups were also conducted with farmers.

The research found that farmers have low levels of confidence in the police, which resulted from the police providing poor response and feedback on incidents. This in turn results in low levels of reporting of crimes by farmers. The police are dealing with increased demands with much lower budgets and few opportunities for specialist training. Combined with ineffective strategic responses and a lack of understanding of farmers’ situations regarding the impact of farm crime, the police are perceived as ineffective in deterring rural criminals.

This paper explores these policing issues and suggests the need to improve confidence among farming communities to encourage the reporting of farm crime, enabling a better understanding of the extent of farm crime in Britain.

Farm crime; police; police response; farmer confidence; improved reporting

The aim of this paper, based on research undertaken by the author, is to explore the police response to rural, and, in particular, farm crime, and how successful this response is perceived to be by farmers. In light of this, the key aspects that the police should be considering to improving the reporting of farm crime is discussed. This paper will consider existing research relating to farm crime and how it affects farmers’ fear of crime and attitudes towards the police, along with the methodology used to address the issues raised. The key findings of the research will be explored in response to the two identified research questions enabling a discussion of what aspects the police in Britain may need to consider for enabling better reporting of farm crime.

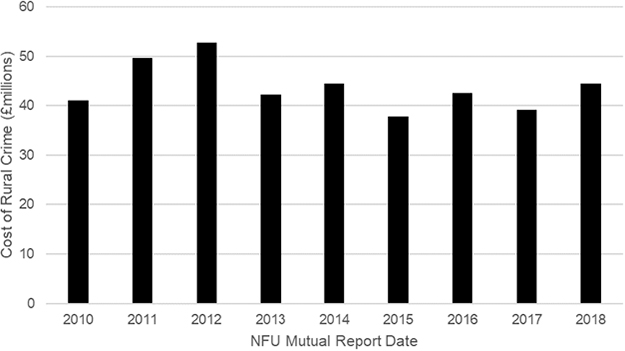

Farms across England and Wales continue to experience profoundly depressing levels of crime,1 with insurance claims reported at £44.5m in 2017.2 This is despite a range of strategies aimed at reducing these problems, including farm crime prevention events run by the police and the National Farmers Union, reduced prices and offers on crime prevention measures by companies, and increased coverage of crime in the farming press. The impact of farm crime reverberates far beyond the immediate rural community, affecting employment, food prices and food traceability.3

Figure 1 Cost of rural crime in Britain as reported by NFU Mutual, 2010-2018

(Source: NFU Mutual)

Tucker argues that ineffective national crime recording classifications, combined with a lack of specialist rural knowledge among responding officers and call handlers means that farm crime is not recorded accurately, and many crimes are subsumed into the much larger volume of urban crime figures.4 Coupled with this is the lack of consistency in defining rural crime. Marshall and Johnson5 note that the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) and the Police recorded crime data record rural crime differently, making the data incomparable and, therefore, ineffective in accurately representing the level of rural crime.6 This has led to a situation in which there is a reliance on data from insurers and other non-governmental sources. That data shows that rural crime is significant, as shown in NFU Mutual’s report, (see Figure 1).7 Not only is there a lack of reliable data, the topic of rural crime is also a relatively neglected area of research in criminological literature.8

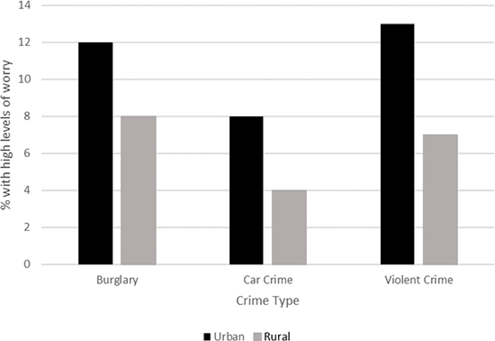

High levels of reported crime in urban areas means that, historically, fear of crime is perceived particularly as an urban problem.9 This is supported by figures obtained from the Crime Survey of E&W 2013/2014,10 as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 High levels of worry about crime in urban vs rural areas across three recordable crime types

Hale postulated that higher levels of fear of crime in urban areas may be partly because of reduced social ties resulting from higher density and increased heterogeneity of the population, leading to isolation and loneliness.11 However, this proposition does not recognise that farms are often affected by geographic isolation in addition to social isolation. Fear of crime among farmers, while culturally unrecognised, potentially has detrimental effects, such as trusting visitors to the farm,12 or even people they know.

Fear of crime among farmers may also negatively affect the uptake of farm crime prevention measures; paradoxically, heightened anxiety and fear can lead to an increase in negative choices.13 Negative choices may also result from a reluctance to make their fear explicit in the face of a belief in the traditional rural masculinity of farmers being strong and resilient.14

Fear of crime among farmers may be partly influenced by the potential, or the perceived potential, that they are likely to be targeted more than once (repeat victimisation - RV). Although the topic of RV has been researched over several decades,15 not much of that research looks at how RV might translate to the rural, and in particular, farm victimisation. Factors, including geographic isolation,16 prior victimisation,17 and the role of a single offender in RV,18 seem to suggest that RV may be more of a problem in rural areas and, particularly, on farms, than research and datasets seem to suggest. If, as Ceccato noted,19 RV affects fear, maybe fear of crime among British farmers extends much further than reported.

In recent years, levels of confidence in the police among farming communities have diminished.20 The cause is said to partly result from ongoing restructuring of the police forces in Britain and a focus on reactive policing, meaning an increase in target-driven policing that focuses on crime hotspots. The restructuring and change in focus have caused local policing to become urban-centric, which has, inevitably, led to the closure of rural police stations21 and a change in the relationship between the police and the farming community.

The village constable was traditionally regarded as part of the rural landscape and, therefore, a part of the rural idyll.22 Now police are often located some distance away.22 The demise of the rural ‘bobby’ may mean that people in rural communities now feel less safe.24 There is evidence that the closure of rural police stations that has led to a reduced police presence in rural areas is correlated with increased targeting of these areas by criminals, particularly by organised crime gangs,25 and decreased conviction rates.26 Farmers are discouraged from reporting crimes, or even helping the police, because of the leniency of the courts and prosecutions being rare.27 Farmers may also consider certain crimes as too trivial to report and, therefore, there are inaccurate records of frequency of the crime, or they do not realise a crime has occurred in the first place.28 This oversight may occur because of the environment in which farmers work. Examples may include being unaware of the theft of sheep until the farmer counts their flock, which may be at irregular intervals particularly on hill farms. In addition, farm machinery used infrequently may be stolen once put into storage, with such theft not noticed until the farmer needs that piece of machinery again, which may not be until the following planting or harvesting season.

To summarise, low levels of confidence in the police force among the farming community are having a detrimental effect on the levels of reporting crime to the police, which influences the allocation of police resources, thus creating a self-fulfilling prophecy, as illustrated in Figure 3. This pattern leads to a disconnect between the police and the people they serve, with farmers not reporting crimes and the police not being present in these communities.

Figure 3 Cyclic issues affecting the policing of farm crime in the British countryside

The study reported on in this paper aimed to identify the extent of low confidence among the farming community towards the police, the factors affecting this situation, and how the police are addressing these issues. The key research questions were: 1. are police force definitions of rural crime enabling an effective response to farm crime; and 2. how can the police improve farm crime reporting. The key findings are presented under these two headings; the findings to question 1 comprising two central aspects relating to how the police are defining rural/farm crime and how they are measuring the effectiveness of their response, and the provision of farm crime prevention advice.

Data was obtained via interviews with various police forces across England, focus groups and interviews with farmers from across Cheshire, Shropshire and Worcestershire in England. The study was conducted within the Harper Adams University Ethics framework and under the Market Research Society Code of Conduct.29

Interviews were requested with Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) and Crime Prevention Advisors (CPAs) from all 41 police forces with an elected PCC. London Metropolitan and Greater Manchester Police Forces do not have elected Commissioners and so were not included in the list. In addition, the areas of rurality within these force areas are limited and these forces likely would not have, or considered the need for, a rural crime strategy.

Responses were received from six forces: Lincolnshire, West Mercia, Thames Valley, Cheshire, Kent and North Wales. As participation from both the PCC and the CPA was required, interviews with CPAs from Kent and North Wales were not included in the analysis, because they did not allow for a direct comparison of the approach to rural crime within forces and between forces. Interviews were carried out either in person or via telephone, and audio recorded for later analysis.

The focus group questions were drafted to address the key concepts of Behavioural Science while remaining on topic regarding farm crime prevention. Four focus groups were held at locations across North Shropshire, Worcestershire, South Shropshire and Cheshire. These areas represent the range of British farming types and included fairly isolated locations and those closer to urban centres. The participants were identified, and the meeting venues arranged with the assistance of local contacts who had regular contact with the farming community. All focus groups were video recorded to allow easier transcription of the discussion.

Five of the participants who took part in the one-to-one interviews were farmers who attended the focus groups and who subsequently volunteered to take part in the interviews. The sixth interview participant was a farmer who had contacted the researcher directly prior to the interviews being arranged and whom the researcher contacted to enquire if they would be happy to take part.

Each interview participant was contacted individually either by email or telephone to arrange a convenient date and time for their interview. All interviews took place at the home of the farmers, which helped to ensure they were comfortable, at ease and more likely to be willing to provide honest opinions rather than what they believed the researcher wanted to hear.

The key findings from the research will be discussed here in relation to the two research questions identified in the methodology. This will explore the police response to farm crime and ways the police could improve farm crime reporting. The police representatives interviewed were the PCCs who were responsible for the strategic oversight and measuring effectiveness of the response to rural/farm crime, and the CPAs who provided direct, individualised guidance to farmers on how to best protect their property.

To understand how police forces in Britain are responding to farm crime, it is important to explore how rural/farm crime is being defined by the police, and how this drives their response. This section explores the responses of the PCCs and CPAs to interview concerning their definitions of rural crime, whether they have or intend to publish a rural crime strategy for their respective police force, how effectiveness is being measured by the police, and how they are providing crime prevention advice. In addition, this section explores the impasse between the police and the farming community regarding the police response to farm crime.

Each force had taken a different approach to defining rural crime. While the varying approaches may reflect the different agricultural communities in each force area, it does not allow for a standardised measurement of effectiveness to be established to allow consistent tracking of the success or otherwise of policies aimed at tackling farm crime.

Definitions of rural crime adopted by the police forces varied greatly and were often criticised by members of the forces. The varied definitions and criticisms reflect the discussion in academia, which highlight concern about a lack of a universally accepted definition among rural crime researchers; this being perpetuated by a lack of clarity of the definition of what is rural. Indeed, what can be classified as ‘rural’ is an international question, as illustrated by research from the US and Australia.30 It may be that those who work on the ‘front line’ of policing, dealing with victims daily, would find a more specific definition and strategic guidance more useful in their day-to-day work.

West Mercia defined rural crime in their strategy document as:

Any crime or anti-social behaviour that takes place in a rural location or is identified as such by the victim.

This definition was criticised by the West Mercia CPA:

Rural crime as a definition is quite vague and quite open. (West Mercia CPA)

Cheshire police defined rural crime in their strategy document as:

Any Crime and Disorder that takes place in a non-urban location as defined by the rural definition. (Output areas)

However, the Cheshire CPA noted that the strategic definition of rural crime from PCC had not been clearly conveyed:

Crime across the equine communities, farming communities, the more rural villages across Cheshire … I don’t think I’ve actually read a definitive description from our side, (Cheshire CPA)

Thames Valley Police have established a detailed strategic definition of rural crime:

We do have a fairly detailed description of rural crime which you’ll find on our website … but it was a difficult one defining what exactly is rural crime (Thames Valley PCC)

Despite this, it is interesting that the CPA and their team work with a slightly less structured definition, which may encompass incidents that may not fit the strategic definition:

Definition we use is anything with the word farm in it, hare coursing, poaching. (Thames Valley CPA)

Despite the effort taken to define rural crime, Thames Valley have not established a rural crime strategy enabling farmers to understand how the force would tackle the issues. While it is possible a rural crime strategy may have little added value at a strategic level, such a document may be a useful tool in increasing the levels of confidence among the farming communities, by enabling farmers to clearly identify what their local force plans to do to address rural crime issues. Indeed, such a document may form a small part of the Behavioural Science (BS) approach to addressing farmer crime prevention decision-making. Providing a rural crime strategy to farmers that sets out what the force intends to do effectively creates a commitment contract. BS researchers have shown that the existence of commitment contracts encourages people or organisations to follow through with beneficial behaviours or actions.31

Lincolnshire police made clear that all crime was treated in the same way across the force area:

Although rural areas have problems that are different to those of urban areas in general, they’re both policed in exactly the same thorough way (Lincolnshire PCC)

This practice may be providing mixed messages, not only to farmers but also to operational police officers. While the PCC states that all crimes are policed in the same way, this negates the impact of such crimes on farmer victims and the added complexities of providing the same service to communities that are often socially disadvantaged and geographically isolated. Moreover, such socio-geographic characteristics of rural communities make it difficult to understand how the model of intelligence-led policing which relies on community-oriented policing32 can be successfully applied to rural communities on a national level when the National Intelligence Model33 is urban centric in its design.34

As a response, CPAs felt it was particularly important that the police have a much better understanding of how crime impacts upon farmers, and their frustrations in relation to the police response to rural crime:

More understanding of how it does affect the rural communities, and just because they perhaps don’t have the same volume of problems, its showing that it is still a problem. (Cheshire CPA)

Feedback such as this may call into question the assertion of some PCCs that all crimes, regardless of where they occur, are being dealt with in the same way. However, farmers noted that, in many cases there is a lack of visible, proactive policing in rural areas, and when the police did turn up, they were often not prepared:

They don’t come out with a pair of boots on, they come out in low shoes. We don’t exist as far as they’re concerned. (Farmers JH)

It was clear when talking with farmers who took part in the research that they perceive the service they receive from the police as not on a par with that provided in urban areas. Farmers exhibited a level of resignation to the fact that police did not respond to crime in rural areas in the same way as they do to crimes in urban areas:

Nine times out of ten they say sorry; we’ve got nobody we can send. (Farmer RA)

I wouldn’t expect the police to put huge resources in that … it’s fairly minor compared to theft in towns, isn’t it? (Farmer JP)

Despite the differing approaches to a rural crime strategy and definitions, there does seem to have been a concerted effort across the four forces to establish a working definition of rural crime to inform the policing response. However, when asked what had been done to tackle farm crime, the PCCs tended to focus on the things that have been done at a more general level, and talked about events, networks and operations, including joint patrols with police and farmers, which seem to be PR events rather than measures of effectiveness that can be adequately evaluated:

The permanent marking of vehicles using CESAR … we’ve got the rural and wildlife officers … recruit the potentially thousands of people in this county who ride horses to become HorseWatch volunteers. (Cheshire PCC)

Whereas the CPAs across the four forces all talked about what they are doing on a more personal level with individual farmers, things that are of immediate benefit:

Key points are being accessible and being visible, appreciating their needs and the fact that the impact of crime is often greater for them, and giving them the appropriate support and reassurance. (Cheshire CPA)

Although such a difference is expected between the PCCs and the CPAs, it is interesting that, despite their inevitable involvement in many things talked about by the PCCs, not one of the CPAs mentioned any of them. This may be indicative of problems arising from policies and strategies that are solely top-down approaches to issues, which may be based on what the PCCs and policymakers think is best for the target population and less likely to come from a consultative process to understand what the target population want and need in a bottom-up approach.35

In light of the range of rural crime definitions, it is hard to see how police forces can meaningfully quantify the effectiveness, or otherwise, of their strategies to tackle rural crime. As a results, police forces in this research report reduced crime levels but do this based on insurance claims data36 rather than crime figures:

You can see it in the National Farmers Union Insurance claims they have gone down in Thames Valley where in most of the rest of the country they have gone up. (Thames Valley PCC)

However, extraneous variables influence insurance claims data, including the non-reporting of losses to insurers and the fact that NFU Mutual do not insure every farmer or rural resident across Britain. By recording the rural crime that is reported specifically as rural crime, forces would be able to accurately report back to their constituents on progress being made to tackle the issues.

Despite the PCCs and CPAs that were interviewed acknowledging they had a role to play in tackling farm crime, some PCCs made it clear the responsibility for protecting the farm comes down to the farmer:

It’s all about harnessing the strength of the rural communities to really mobilise themselves … because the police clearly can’t be there twenty-four hours a day” (Cheshire PCC)

When considering how to improve the uptake of farm crime prevention, the police felt that farmers tend to be stuck in their ways, afflicted by status quo bias37 and getting them to change their way of doing things may prove problematic:

They become quite resentful because they say they’ve done this for thirty years and they’ve never been a target in the past. (Cheshire CPA)

While some farmers did agree with this assessment, many farmers are more likely to use crime prevention now than ever before:

We’re doing more than we ever used to about crime prevention. But it’s not enough. (Farmer PG)

Any advice given to the farmer may or may not be acted upon, dependent upon the way the police think farmers feel about change. This is captured by something that the Lincolnshire CPA said:

We only go and give advice. It’s up to the farmer if he then acts upon that advice. (Lincolnshire CPA)

This is reflected by the fact that some farmers admit to not doing anything to protect their property:

I don’t lock anything up. (Farmer HW)

Another comment from the Lincolnshire CPA tends to suggest, possibly from experience, that farmers can underestimate their risk of victimisation and so seem to be hyperbolic discounters when it comes to adopting crime prevention:

It’s never happened, so it’s never going to happen. (Lincolnshire CPA)

This is reflected by some of the comments made by farmers themselves with crime prevention not necessarily being high on their priority list:

We’ll probably talk about it but not do anything about it. (Farmer PG)

In a bid to enable an effective police response, there seems to be a general agreement among the CPAs from the forces that specific training relating to attending farms and identifying key equipment and livestock would be beneficial in their day-to-day working and being able to better provide advice on how to best protect that property:

Additional training is always of benefit (West Mercia CPA)

However, a shortage of available funding may be preventing some CPAs from undertaking such training and learning their trade as they go along:

Can’t afford to send some to all these. (Thames Valley CPA)

By contrast, PCCs seemed to feel that specific training may not be a necessary value-added activity or an effective use of scant resources:

It probably is … if there is specific stuff for rural crime. But I have to say that a great deal of it is normal policing, it shouldn’t be exceptional. (Thames Valley PCC)

It is questionable whether someone without specialist knowledge, not just of crime prevention but of working farms, should be visiting such sites given the potential health and safety issues on a farm holding. Moreover, if specific training on vehicle identification, livestock marking and handling, or farming tools had not been undertaken, one must question how a CPA can adequately advise on the best crime prevention options for that property and, therefore, provide an effective response to the problem of farm crime.

It seems from this snapshot of feedback that the police are trying to encourage farmers to be more proactive about crime prevention, however, they may not be approaching it in the right way because farmers do not seem to be heeding advice to protect their property. Farmers simply want crime prevention advice to be effective, tailored and from a trusted source and, while they are less concerned by who provides the advice, most did feel that it should be the police or insurers.

More than one PCC noted that to improve farm crime reporting requires an improvement in engagement between the police and farmers:

It’s engaging with the communities, and the police have got to engender the confidence of the communities. They’d be foolish to walk away from it now. (West Mercia PCC)

It was noted by the CPA of West Mercia that, due to historic government policies, many rural communities were not policed in the way they should have been policed:

Crime in rural areas would have been policed on a second-rate basis, and that was to do with Home Office targets and guidelines. These have changed, particularly with the advent of the PCC’s office. (West Mercia CPA)

To address these historic issues, the forces have identified a variety of operational strategies that seem to be proving successful in tackling rural crime:

We found that targeted policing can be hugely effective … Operation Galileo aimed at dissuading and prosecuting harecoursers. (Lincolnshire PCC)

Go out on patrol with members of the rural communities so hopefully you learn a little bit about their area, they learn a little bit about our life. (Thames Valley CPA)

These operational strategies are showing signs of success because they are getting farmers involved and the police are making decisions about how to tackle crime at a local level rather than a force-wide level. With operational strategies such as those described above, which may be long-term operations such as Operation Galileo, or short-term sporadic operations such as that described by the Thames Valley PCC, it is often the local policing teams who are working with farmers to enable these operations; though they recognise there is a lot more to do. Operational strategies such as these should instil confidence in the farmers that the police are serious about tackling farm crime, but the police need to recognise the need for a long-term strategy not just a stand-alone week-long operation.

The improvement of confidence levels towards the police among farmers is perhaps the most important measure of success for police rural crime strategies. Without improved confidence levels, farmer reporting of crime, buy-in and the provision of valuable information is unlikely to increase.

From the discussions, it seems the starting point has to be increasing the visibility of the police in rural areas. While research shows that an increased police presence does not necessarily deter crime,38 it might reassure farmers:

Some of them say oh this is great, we know you’re in the area now and we feel reassured, we feel like there is a presence. (Cheshire CPA)

Most farmers, however, reported feeling abandoned by the police following the closure of almost all rural police stations and the loss of many local rural police officers:

We’d love to see the police around a bit more often. (Farmer RB)

By increasing visibility and talking to the farmers, the police can make farmers aware of what the police are doing to address farm crime and potentially encourage the farmers to work with the police:

It’s about developing initiatives and ensuring that the farming community, particularly the rural communities, are aware of what we’re doing. (Cheshire PCC)

By increasing the visibility of the police and raising awareness of what they are doing, steps can be taken by the police to ensure farmers feel their time and information is valued, they will be listened to and that something will be done:

One of the biggest plusses was that they felt they were being listened to at last, and we were actually interested. (Thames Valley CPA)

Despite this feeling from the Thames Valley CPA, farmers taking part – both in this research and from across Britain as reported by the National Rural Crime Survey39 – still felt that the police were not taking their crime reports seriously. This is despite varying attempts by police forces across Britain to improve the service provided to rural communities – examples of which can be seen on the National Rural Crime Network website40 – which has a detrimental effect on the future likelihood of reporting crimes:

I think [the police] are paying lip service to it [farm crime] at the moment. (Farmer AB2)

Farmers are not satisfied with police simply making a record of rural crime. The response they get when they do report crime to the police is of more of concern and a key aspect influencing their lack of confidence in the police:

All [the police] do is give you a crime number and that’s it. (Farmer RA)

You have almost settled for a crime number and that is it. (Farmer CW)

In addition, it is suggested that to improve confidence, it is essential that the police provide feedback to farmers on what is happening, or any information farmers have provided. This is identified by the Cheshire CPA:

Ensuring that when people do report a crime, they are having information fed back to them and there’s some coordination. (Cheshire CPA)

Nonetheless, this does not seem to be happening in practice, leaving farmers feeling frustrated:

We need to know what’s happening about things because we need other people to realise that if they do report something, something happens. (Farmer KB)

These comments suggest that by improving the communication between themselves and farmers, improving visibility, and showing they are taking farm crime seriously, the police may enable farmer buy-in to the strategic response:

It’s vital that we have the buy-in of the farming community. (Lincolnshire PCC)

Moreover, in addition to improving visibility and communications with farmers, the police also need to ensure that those officers who respond to the reports of farm crime are suitably prepared to attend a farm, and present an attitude of willingness to help the farmers, unlike the experience one farmer reported:

You’re not going to catch any of [the criminals] then, so you may as well go back to the town where you want to be. (Farmer EH)

Police forces that took part in this research and police forces across Britain41 recognise the need to increase the confidence levels among farming communities. By laying the foundations of confidence and trust, farmers may be more likely to cooperate with the police, and negative feelings that persist among farmers may dissipate enabling improved measures of effectiveness:

You get people saying we don’t bother reporting crime, waste of time the police, or the police aren’t interested, which causes you a little bit of concern. (West Mercia PCC)

This is reflected by the comment of one farmer:

I can’t see what all the fuss is wasting time with the police when they’re just a waste of time. (Farmer AB1)

When considering what the police could do to improve confidence and trust, the farmers in this research felt the response from the police was generally poor, leaving some farmers disappointed in the police. This leads to the situation where farmers were only reporting the crime to obtain a crime number for their insurance, as previously discussed, rather than having any expectations that the police will do anything about the report:

I rang [the police] out of desperation and I must admit I was really disappointed in them. They say all the right things and did all the wrong things. (Farmer JH)

It should also be important to continue the engagement with farmers after they have reported something to the police and, wherever possible, arranging a personal visit to the farm to follow up, feedback and provide guidance or assistance where required:

I don’t think I’ve had more visits requested as a result of crime; I’ve had more visits because the awareness of people has raised of rural crime. (Cheshire CPA)

By engaging in this way, and ensuring farmers understand the police are aware of how big an issue crime on farms is, police forces may be able to regain the trust of farmers and increase the likelihood of a farmer reporting a crime to the police:

[The farmers] never hear anything else from the police and I think that really infuriates people. (Farmer ST)

To support this need for improved engagement, the following comment is indicative of the current perceived lack of interest on the part of the police. While many farmers were prepared to help the police with information, if that information is passed off as irrelevant by the police it will only harm relations between the two further:

I went to the police and said I’ve got the reg. I’ve got the car. I’ve got the description of three men. No, I don’t think that’s relevant, until they’ve come to court and he says would you come to court, no thank you. (Farmer AM)

Furthermore, the farmers talked about the at times extreme lengths they had to go to just to get a response from the police:

The only time [the police respond] is if you threaten that you have got a shotgun under your arm and you are going to use it … and that is terrible really. (Farmer RB)

In light of the farmer comments, it seems that the test for police forces will be in re-establishing confidence and trust with farmers in the years to come. Without a two-way interaction, it will continue to prove difficult to obtain the information from farmers that can create the intelligence required to support the need for ongoing and improved rural policing. However, it seems that there is currently little the police are doing that is likely to win over the farming community and encourage increasing confidence levels and closer working:

It’s not an easy job is it … But sometimes [the police] don’t help themselves. (Farmer AB2)

Several conclusions can be drawn from this research in relation to rural/farm crime and how the police response is perceived within the police, and among the farming community.

It is arguable that the police need to establish a better understanding of what rural/farm crime actually is. Each force is defining rural crime in a different way. This may be as a result of the lack of a national definition of rural crime and what constituent farm crime, wildlife crime and heritage crime. While it is acknowledged that a national definition may not be suitable for all police forces, it would provide the foundation for a clear strategic plan that could be adapted to meet the specific needs of the individual police forces. This would ensure that the police force response would take into account the added complexities of geographic isolation, longer response times, and how access to victim services should be handled. To enable such a response, it could be the case that individual police forces consult with rural and farming communities to ensure their input in considered in the creation of rural crime strategies.

There seems to be the need for a coherent, long-term, strategic approach to tackling rural/farm crime in its widest sense. Such strategies should be created in conjunction with farmers to enable the buy-in of those best placed to identify issues. It is noted from this research that the police and the farmers may have different ideas about what rural/farm crime is and the best way these crimes should be tackled.

It is essential that the police have a better understanding of the wider impact of crime on farmers to be able to best serve them. It is clear from this research that, despite the efforts so far on the part of the police, farmers do not feel that the response of the police to farm crime and, therefore, the service being provided, is effective. Consideration needs to be paid to the fact that rural/farm crime is different to urban crime. Not necessarily in its form, but in the fact that the impact is compounded by distance, isolation and a lack of resources and available services in the locality. The police could achieve this by improving their approach to policing rural/farm crime, recognising the additional vulnerabilities that rural communities face and by moving towards a more proactive way of dealing with these crimes. Such an approach may have wider positive benefits for addressing other crimes committed within the rural setting.

The key aspect that the police need to address is how to improve confidence levels among rural communities, therefore making farmers more likely to report crimes and other information to police. Only by improving confidence levels will the police be better able to get a true reflection of the extent of rural/farm crime, its impact on victims, and an understanding of how offenders are using the British countryside for their own gain. Furthermore, by improving confidence levels, and thus crime reporting, the police will be able to better record rural/farm crime, which will enable them to provide an improved measure of the effectiveness of their rural crime policies.

Despite some examples of good practice across British police forces, this research suggests that there is a lot of work for police forces to do. There seems to be a need for a more coordinated approach to creating a working definition of rural/farm crime that enables a more integrated, cross-force approach to tackling rural crime, while at the same time recognising the specific issues each police force may be dealing with. Furthermore, having a coordinated definition of rural crime could enable more meaningful analysis of rural crime data and, therefore, more robust measures of effectiveness. Hand-in-hand with this, there needs to be concerted efforts to rebuild trust among farming communities that the crimes they report are being taken seriously. This will lay the foundations for building an increase in farmer confidence towards the police in conjunction with greater visibility, improved communications and better training for police and police staff at all levels. With increased confidence, it is suggested that increased farmer buy-in of the police response to rural/farm crime will follow, thus enabling improved levels of farm crime reporting and farm crime prevention uptake. Moreover, such improved understanding of rural/farm crime among the police, combined with increased confidence among farmers and rural communities to report things they witness could herald a move away from the British countryside being considered an ungoverned space and towards truly intelligence-led, proactive rural policing in Britain.

Aust, Rebecca, and Jon Simmons, Rural Crime: England and Wales, 01/02 (Home Office, 2002)

Bankston, William B, et al, ‘Fear of Criminal Victimization and Residential Location: The Influence of Perceived Risk’ (1987) 52(1) Rural Sociology 98

Barclay, Elaine, ‘The Determinants of Reporting Farm Crime in Australia (2003) 27(2) International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice 131. DOI: 10.1080/01924036.2003.9678706

Barclay, Elaine, et al. Property Crime Victimisation and Crime Prevention on Farms: Report to the New South Wales Attorney General’s Crime Prevention Division. (The Institute for Rural Futures, 2001)

Brandt, Berit, and Marit S Haugen, ‘Rural Masculinity’ In M Schucksmith and D L Brown (eds) Routledge International Handbook of Rural Studies (Routledge, 2016) 412

Bryan, Elizabeth, et al, ‘Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change in Kenya: Household Strategies and Determinants’ (2013) 114 (15 January) Journal of Environmental Management 26. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.10.036

Carcach, Carolos, Size, Accessibility and Crime in Regional Australia: Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice. (Australian Institute of Criminology, 2000)

Ceccato, Vania, Rural Crime and Community Safety (Routledge, 2016) 65.

Chalfin, Aaron et al, The Costs of Benefits of Agricultural Crime Prevention (Urban Institute Justice Policy Center, Florida State University College of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 2007) 1

Donnermeyer, Joseph, and Elaine Barclay, ‘The Policing of Farm Crime’ (2005) 6(1) Police Practice and Research 3. DOI: 10.1080/15614260500046913

Farrell, Graham, and Ken Pease, Once Bitten, Twice Bitten: Repeat Victimisation and its Implications for Crime Prevention (Police Research Group Crime Prevention Unit Series Paper No 46, 1993, London: Home Office Police Department)

Garside, Richard, ‘Crime is down. Crime is up. What’s going on?’ Centre for Crime and Justice Studies (online), 24 April 2015 <https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/resources/crime-down-crime-whats-going>; see also, Jane Jones, The Neglected Problem of Farm Crime: An Explanatory Study, 2010, 9, Safer Communities, 36-44. DOI: 10.5042/sc.2010.0013

Gilchrist, Elizabeth, et al, ‘Women and the ‘Fear of Crime’: Challenging the Accepted Stereotype’ (1998) 38(2), British Journal of Criminology, 283. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a014236

Gilling, Dan, Crime Reduction and Community Safety: New Labour and the Politics of Local Crime Control (Willan, 2011).

Gottfredson, Michael I, Victims of Crime: The Dimensions of Risk. (Home Office, 1994)

Hale, Chris, ‘Fear of Crime: A Review of the Literature’ (1996) 4(2), International Review of Victimology 79. DOI: 10.1177/026975809600400201

Halpern, Scott D, et al, ‘Commitment Contracts as a Way to Health’ (2012) 344(e522) British Medical Journal 22. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.e522

Hartley, Catherine A, and Elizabeth A Phelps, ‘Anxiety and Decision-Making’ (2012) 72(2) Biological Psychiatry 113. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.027

Hepburn, Cameron, et al, ‘Behavioural Economics, Hyperbolic Discounting and Environmental Policy’ (2010) 46(2) Environmental and Resource Economics 189. DOI: 10.1007/s10640-010-9354-9

Insurance claims data only extends to that published by NFU Mutual. This poses its own issues as only three quarters of farmers are insured with NFU Mutual

Jackson, Jonathan, ‘Bridging the Social and the Psychological in the Fear of Crime’ in M Lee and S Farrall (eds), Fear of Crime: Critical Voices in an Age of Anxiety (GlassHouse Press, 2008) 143

John, Tim, and Mike Maguire, ‘The National Intelligence Model: Key Lessons from Early Research’ (Home Office Online Report 30/04, 2004)

Johnson, Joan H, et al, ‘The Recidivist Victim: A Descriptive Study’ in Institute of Contemporary Corrections and The Behavioural Sciences, Criminal Justice Monograph (Sam Houston University, vol 41, 1973)

Jones, Jane, and Jen Phipps, ‘Policing Farm Crime in England and Wales’ (Conference paper, British Criminology Conference, 2012) 3 <http://britsoccrim.org/new/volume12/PBCC_2012_12_wholevolume.pdf>

Kahneman, Daniel, et al, ‘Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias’ (1991) 5(1) The Journal of Economic Perspectives 193. DOI: 10.1257/jep.5.1.193

Kleck, Gary, and James C Barnes, Do More Police Lead to More Crime Deterrence? 2010, 60(5), Crime and Delinquency, 716-738. DOI: 10.1177/0011128710382263

Marshall, Ben, and Shane Johnson, Crime in Rural Areas: A Review of the Literature for the Rural Evidence Research Centre (London, UCL, 2005) 10

Matland, Richard E, ‘Synthesizing the Implementation Literature: The Ambiguity-Conflict Model of Policy Implementation (1995) 5(2) Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 145. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a037242

Mawby, Rob I, ‘Myth and Reality in Rural Policing: Perceptions of the Police in a Rural County of England’ (2004) 27(3) Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 431. DOI: 10.1108/13639510410553158

Mingay, Gordon E, The Rural Idyll (Routledge, 1989)

MRS, MRS Code of Conduct, (online, 2014) <https://www.mrs.org.uk/pdf/mrs%20code%20of%20conduct%202014.pdf>

National Farmers Union, ‘Combatting Rural Crime’ (NFU, 2018)

National Rural Crime Network, ‘Best Practice’ (NRCN, undated). <https://www.nationalruralcrimenetwork.net/best-practice/>

National Rural Crime Network, ‘National Rural Crime Survey: Living on the Edge’ (NRCN, 2018). <https://www.nationalruralcrimenetwork.net/research/internal/2018survey/>

Office for National Statistics, Crime Statistics, Focus on Public Perceptions of Crime and the Police, and the Personal Well-being of Victims: 2013 to 2014 (2015) 31

Pease, Ken, Repeat Victimisation: Taking Stock. (Crime Detection and Prevention Series, Paper No 90, Home Office, 1998).

Peterson, Marilyn, ‘Intelligence-led Policing: The New Intelligence Architecture’ (US Department of Justice, 2005).

Reft, Tim, ‘Rural Crime costs “Hit Five-Year High”’, Farmers Weekly (online, 30 March 2018) <https://www.fwi.co.uk/news/rural-crime-costs-hit-five-year-high>

‘Rural Crime Report 2018: Taking the Fight Forward’, NFU Mutual (Web Page, 14 August 2018) <https://www.nfumutual.co.uk/farming/ruralcrime/>

Skogan, Wesley G, and Michael G Maxfield, ‘Coping with Crime: Individual and Neighborhood Reactions’ (Sage, 1981) 14.

Smith, Robert, ‘Developing a Working Typology of Rural Criminals: From a UK Police Intelligence Perspective’ (2013) 2(1) International Journal of Rural Criminology 126. DOI: 10.18061/1811/58844

Smith, Robert, ‘Policing the Changing Landscape of Rural Crime: A Case Study from Scotland’ (2010) 12(3) International Journal of Police Science and Management 373. DOI: 10.1350/ijps.2010.12.3.171

Smith, Robert, et al, ‘The Rise of Illicit Rural Enterprise Within the Farming Industry: A Viewpoint (2013) 2(4) International Journal of Agricultural Management 185. DOI: 10.5836/ijam/2013-04-01

Smith, Robert, and Peter Somerville. ‘The Long Goodbye: A Note on the Closure of Rural Police Stations and the Decline of Rural Policing in Britain (2013) 7(4) Policing 348. DOI: 10.1093/police/pat031

Swanson, Charles, ‘Rural and Agricultural Crime’ (1981) 9(1), Journal of Criminal Justice 19. DOI: 10.1016/0047-2352(81)90048-9

Tseloni, Andromachi, et al. Exploring the International Decline in Crime Rates (2010) 7(5). European Journal of Criminology 375. DOI: 10.1177/1477370810367014

Tucker, Sarah, Rural Crime and Policing: Literature Review (Cardiff, Universities’ Police Science Institute, 2015) 6.

Weisheit, Ralph, et al, Crime and Policing in Rural and Small-Town Rural America (Waveland Press, 2006)

1 Tim Relf, ‘Rural Crime Costs “Hit Five-Year High”’, Farmers Weekly (online, 30 March 2018) <https://www.fwi.co.uk/news/rural-crime-costs-hit-five-year-high>.

2 ‘Rural Crime Report 2018: Taking the Fight Forward’, NFU Mutual (Web Page, 14 August 2018) <https://www.nfumutual.co.uk/farming/ruralcrime/>.

3 Aaron Chalfin et al, The Costs of Benefits of Agricultural Crime Prevention (Urban Institute Justice Policy Center, Florida State University College of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 2007) 1.

4 Sarah Tucker, Rural Crime and Policing: Literature Review (Cardiff, Universities’ Police Science Institute, 2015) 6.

5 Ben Marshall and Shane Johnson, Crime in Rural Areas: A Review of the Literature for the Rural Evidence Research Centre (London, UCL, 2005) 10.

6 Indeed, Richard Garside has noted that the CSEW is neither a survey of crime, a survey of victims, nor a survey of victimisation, thus suggesting its use in crime research is, in itself, problematic: Richard Garside, ‘Crime is down. Crime is up. What’s going on?’ Centre for Crime and Justice Studies (online), 24 April 2015 <https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/resources/crime-down-crime-whats-going>; see also, Jane Jones, The Neglected Problem of Farm Crime: An Explanatory Study, 2010, 9, Safer Communities, 36-44. DOI: 10.5042/sc.2010.0013.

8 Jane Jones and Jen Phipps, ‘Policing Farm Crime in England and Wales’ (Conference paper, British Criminology Conference, 2012) 3 <http://britsoccrim.org/new/volume12/PBCC_2012_12_wholevolume.pdf>.

9 Wesley G Skogan and Michael G Maxfield, ‘Coping with Crime: Individual and Neighborhood Reactions’ (Sage, 1981) 14.

10 Office for National Statistics, Crime Statistics, Focus on Public Perceptions of Crime and the Police, and the Personal Well-being of Victims: 2013 to 2014 (2015) 31.

11 Chris Hale, ‘Fear of Crime: A Review of the Literature’ (1996) 4(2), International Review of Victimology 79. DOI: 10.1177/026975809600400201.

12 Elizabeth Gilchrist et al, ‘Women and the ‘Fear of Crime’: Challenging the Accepted Stereotype’ (1998) 38(2), British Journal of Criminology, 283. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a014236; Jonathan Jackson, ‘Bridging the Social and the Psychological in the Fear of Crime’ in M Lee and S Farrall (eds), Fear of Crime: Critical Voices in an Age of Anxiety (GlassHouse Press, 2008) 143.

13 Catherine A Hartley and Elizabeth A Phelps, ‘Anxiety and Decision-Making’ (2012) 72(2) Biological Psychiatry 113. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.027.

14 Berit Brandt and Marit S Haugen, ‘Rural Masculinity’ in M Schucksmith and D L Brown (eds) Routledge International Handbook of Rural Studies (Routledge, 2016) 412.

15 Joan H Johnson et al, ‘The Recidivist Victim: A Descriptive Study’ in Institute of Contemporary Corrections and The Behavioural Sciences, Criminal Justice Monograph (Sam Houston University, vol 41, 1973); Michael R Gottfredson, Victims of Crime: The Dimensions of Risk. (Home Office, 1994); Graham Farrell and Ken Pease, Once Bitten, Twice Bitten: Repeat Victimisation and its Implications for Crime Prevention (Police Research Group Crime Prevention Unit Series Paper No 46, 1993, London: Home Office Police Department); Andromachi Tseloni et al. Exploring the International Decline in Crime Rates (2010) 7(5). European Journal of Criminology 375. DOI: 10.1177/1477370810367014.

16 William B Bankston et al, ‘Fear of Criminal Victimization and Residential Location: The Influence of Perceived Risk’ (1987) 52(1) Rural Sociology 98.

17 Vania Ceccato, Rural Crime and Community Safety (Routledge, 2016) 65.

18 Ken Pease, Repeat Victimisation: Taking Stock. (Crime Detection and Prevention Series, Paper No 90, Home Office, 1998).

20 Dan Gilling, Crime Reduction and Community Safety: New Labour and the Politics of Local Crime Control (Willan, 2011).

21 Rob I Mawby, ‘Myth and Reality in Rural Policing: Perceptions of the Police in a Rural County of England’ (2004) 27(3) Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 431. DOI: 10.1108/13639510410553158; Robert Smith and Peter Somerville. ‘The Long Goodbye: A Note on the Closure of Rural Police Stations and the Decline of Rural Policing in Britain (2013) 7(4) Policing 348. DOI: 10.1093/police/pat031.

22 Gordon E Mingay, The Rural Idyll (Routledge, 1989).

23 Rebecca Aust and Jon Simmons, Rural Crime: England and Wales, 01/02. (Home Office, 2002).

24 Robert Smith, ‘Policing the Changing Landscape of Rural Crime: A Case Study from Scotland’ (2010) 12(3) International Journal of Police Science and Management 373. DOI: 10.1350/ijps.2010.12.3.171.

25 Robert Smith et al, ‘The Rise of Illicit Rural Enterprise Within the Farming Industry: A Viewpoint (2013) 2(4) International Journal of Agricultural Management 185. DOI: 10.5836/ijam/2013-04-01.

26 Elaine Barclay et al. Property Crime Victimisation and Crime Prevention on Farms: Report to the New South Wales Attorney General’s Crime Prevention Division. (The Institute for Rural Futures, 2001).

27 Joseph Donnermeyer and Elaine Barclay, ‘The Policing of Farm Crime’ (2005) 6(1) Police Practice and Research 3. DOI: 10.1080/15614260500046913.

28 Barclay et al 2001 (n 30) 24; Elaine Barclay, ‘The Determinants of Reporting Farm Crime in Australia (2003 ) 27(2) International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice 131. DOI: 10.1080/01924036.2003.9678706; Charles R Swanson, ‘Rural and Agricultural Crime’ (1981) 9(1), Journal of Criminal Justice 19. DOI: 10.1016/0047-2352(81)90048-9.

29 MRS, MRS Code of Conduct, (online, 2014) <https://www.mrs.org.uk/pdf/mrs%20code%20of%20conduct%202014.pdf>.

30 Barclay 2003 (n 34) 133; Carlos Carcach, Size, Accessibility and Crime in Regional Australia: Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice. (Australian Institute of Criminology, 2000); Ralph Weisheit et al, Crime and Policing in Rural and Small-Town Rural America (Waveland Press, 2006).

31 Elizabeth Bryan et al, ‘Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change in Kenya: Household Strategies and Determinants’ (2013) 114 (15 January) Journal of Environmental Management, 26. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.10.036; Scott D Halpern et al, ‘Commitment Contracts as a Way to Health’ (2012) 344(e522) British Medical Journal 22. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.e522; Cameron Hepburn et al, ‘Behavioural Economics, Hyperbolic Discounting and Environmental Policy’ (2010) 46(2) Environmental and Resource Economics 189. DOI: 10.1007/s10640-010-9354-9.

32 Marilyn Peterson, ‘Intelligence-led Policing: The New Intelligence Architecture’ (US Department of Justice, 2005).

33 Tim John and Mike Maguire, ‘The National Intelligence Model: Key Lessons from Early Research’ (Home Office Online Report 30/04, 2004).

34 Robert Smith, ‘Developing a Working Typology of Rural Criminals: From a UK Police Intelligence Perspective’ (2013) 2(1) International Journal of Rural Criminology 126. DOI: 10.18061/1811/58844.

35 Richard E Matland, ‘Synthesizing the Implementation Literature: The Ambiguity-Conflict Model of Policy Implementation (1995) 5(2) Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 145. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a037242.

36 Insurance claims data only extends to that published by NFU Mutual. This poses its own issues as only three quarters of farmers are insured with NFU Mutual: see NFU Mutual (n 2) 2.

37 Daniel Kahneman et al, ‘Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias’ (1991) 5(1) The Journal of Economic Perspectives 193. DOI: 10.1257/jep.5.1.193.

38 Gary Kleck and James C Barnes, Do More Police Lead to More Crime Deterrence? 2010, 60(5), Crime and Delinquency, 716-738. DOI: 10.1177/0011128710382263.

39 National Rural Crime Network, ‘National Rural Crime Survey: Living on the Edge’ (NRCN, 2018). <https://www.nationalruralcrimenetwork.net/research/internal/2018survey/>

40 National Rural Crime Network, ‘Best Practice’ (NRCN, undated). <https://www.nationalruralcrimenetwork.net/best-practice/>

41 National Farmers Union, ‘Combatting Rural Crime’ (NFU, 2018).