International Journal of Rural Law and Policy, No. 2, 2019

ISSN 1839-745X | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://ijrlp.epress.lib.uts.edu.au

ARTICLE (NON-REFEREED)

A comparison of rural crimes in Australia (NSW) and South Africa

International Journal of Rural Law and Policy, No. 2, 2019

ISSN 1839-745X | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://ijrlp.epress.lib.uts.edu.au

ARTICLE (NON-REFEREED)

Willie Johannes Clack

Department of Corrections Management, School of Criminal Justice, College of Law, University of South Africa. wclack@unisa.ac.za

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijrlp.2.2019.6467

Article History: Received 06/02/2019; Revised 13/06/2019; Accepted 17/06/2019; Published 06/08/2019

Citation: Willie Johannes Clack 2019. A comparison of rural crimes in Australia (NSW) and South Africa (2019) 2 (special issues on Rural Crime) International Journal of Rural Law and Policy. Article ID 6467, https://doi.org/10.5130/ijrlp.2.2019.6467

© 2019 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Rural criminology as a topic of scholarly study, neglected over the past two to three decades, has bounced into the spotlight, with claims now being made that rural criminology is receiving justified attention among the academic fraternity. This paper presents a comparative analysis of the major challenge facing two countries with different levels of development as identified by the United Nations Human Development Index. A predicament for rural criminology is that the world is not equal: rural crimes is researched in developed countries but not in developing countries. This paper compares the types and prevalence of agricultural crimes in Australia (NSW) and South Africa to determine whether significant differences or similarities exist.

Agricultural crimes; contact crimes; comparative study; economic development; livestock theft; rural crimes; victimisation rates

Crime affects all people, irrespective of demography, which is contrary to the impression created by 21st Century television and movies which depict crime as an urban phenomenon only. Gone are the days when people watched Country and Western movies showing that crimes, and activities associated with crimes, existed in all spheres of society. Modern society and academia within the social sciences conveniently forget that towns originally developed to escape rural banditry, as portrayed in the old movies; the consequence is the neglect of research into crime in rural areas – though, fortunately, it is currently receiving attention. Donnermeyer recently chronicled the discipline of rural criminology, showing the trajectory in research since 1931.1

The study of rural crime enhances understanding of and helps efforts to prevent specific crimes in these areas. Significantly, recent studies2 indicate that rural crimes are not only a concern in developed countries but also in developing countries; however, studies or rural crimes in developed countries are sparse. The reason for this neglect may be an underestimation of the negative impact of crime on the sustainable development of rural areas in developing countries.3 Irrespective of this view, it is clear that the discipline is in an early stage of development, not least because it has thus far failed to clearly define the terms ‘rural’ and ‘rural crimes’. Defining these terms becomes even more complex when they are applied internationally and differences between countries, regions, provinces etc, and rural and urban crimes are neglected.

This paper presents a comparative analysis of rural crime in the context of levels of development as defined by the UN Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI status of a country is important because rural areas in developed countries tend generally to have lower levels of crime when compared to urban areas.4 This paper begins by using different definitions of the term ‘rural’ to highlight the challenges when conducting comparative studies across different economies and cultures. The definitions adopted in Australia and in South Africa are then explored in an attempt to find common denominators for comparison.

The latter part of the paper deals with specific comparisons of agricultural crime victimisation rates in Australia (NSW) and South Africa, determining significant differences and/or similarities that may influence future research and/or policies. The two jurisdictions were chosen based on the availability of information in NSW in Australia and the familiarity of the South African situation to the author.

For decades, the terms ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ were accepted as socio-economic classifications of countries based on the prosperity and standard of living of their populations. Ironically, the UN does not have an official definition for these terms. The World Bank (WB) simply lumps together countries in the top third of gross national income (GNI) as developed countries and the bottom two-thirds as developing countries.5 The World Trade Organisation (WTO) allows countries to declare themselves as either developing or developed.6 The International Monetary Fund (IMF) states that its own distinction between advanced and emerging market economies ‘is not based on strict criteria, economic or otherwise’.7 The various global organisations do not have consensus on the classification of developed and developing countries because each organisation has different aims and objectives. In 2016, the WB decided that, in future, it would not distinguish between ‘developed’ countries and ‘developing’ countries in the presentation of its data. The decision marked an evolutionary change in thinking about the distribution of poverty and prosperity. Although it may sound drastic, the decision is not radical, considering that, universally, nobody agrees on a definition of these terms.8

At present, most organisations use the HDI of the UN Development Programme (UNDP) to measure the achievements of countries in three aspects of human development: health, education and living standards. These aspects of human development provide a single statistic that serves as the frame of reference for both social and economic development observed in this paper.9

Environmental criminology theories and concepts are used to explain agricultural crimes by examining the interactions between people and what surrounds them, as well as how these interactions encourage some people to commit a crime.10 Environmental criminology is not limited to a single theory but consists of a family of approaches relating to crime,11 which comprise the concepts of routine activity, crime pattern, rational choice and buffer zone.12 Each of the approaches analyses crimes from a different angle but, in the end, they all arrive at the same place.13 The routine activity theory is the most useful of the theories for this study. It requires the breakdown of the crime into the constituent elements of willing offender, suitable object and absence of a guardian (victim) in the environment, all of which are necessary for the crime to be committed.14 The overlap between the activities of the offender and those of the victim creates a location in which the offender feels comfortable to commit a crime provided a suitable object is present.15 Routine activity supports the notion that crime can be committed anywhere within the offender’s activity space, but, naturally, criminal activity is spatially dependent on proximity to the offender’s activity nodes. In the analysis and comparisons, routine activities, motivated offender, suitable target and guardian will form part of the equation when appropriate.

The study is cross-national and compares overall human security, agricultural rural indicators and the victimisation rates of agricultural crimes for farmers in NSW, Australia and South Africa, focusing on similarities and differences between the two countries. Document analysis as a research method was adopted and, to seek convergence and corroboration, a variety of resources was utilised. The main resources, however, were the HDI of the UNDP and data in studies by Elaine Barclay, specifically, the paper ‘The context of farm crime in Australia’,16 and the Bureau of Market Research (BMR). The objective of the study was to measure the financial impact and reporting of crime incidents.17

In 2015, the author contacted Elaine Barclay of New England University, Armidale, NSW, Australia, requesting a copy of the research questionnaire she used for her study on farm crime and permission to alter the questionnaire for South African circumstances as well as to utilise the questionnaire for rural crime research in South Africa. The questionnaire and authorisation for utilisation were provided promptly without any prerequisites and/or conditions.18 The questionnaire was amended to South African English and vocabulary, for example, paddock was changed to kraal, mustering to gathering, acres to hectare etc. To avoid errors in respondent comprehension and interpretation, the questionnaire was tested, using convenience sampling, by 15 farmers known to the author who were assured of anonymity. However, the research did not proceed at this time because of funding limitations.

On 13 November 2017, Prof Tustin of the BMR, University of South Africa, made a presentation to the rural safety committee of AgriSA19 for conducting a national agricultural sector crime survey of South African farmers who were members of the organisation. The author, who attended the meeting, indicated that a questionnaire had already been developed and tested, with the necessary permission having been obtained for utilisation. In January 2018, the researchers and parties from AgriSA designed a more condensed version of the original questionnaire to measure the prevalence, incidence, financial impact and reporting of crime incidents experienced by commercial farming units in South Africa. The results were made available to AgriSA20 in July 2018.

One of the Author’s prerequisites for providing the original questionnaire was to be able to use the results for further research and publication. The last agricultural census in South Africa was carried out in 2001; therefore, all figures used in the results are estimates. The BMR study had a specific mandate, and the survey dealt only with commercial farmers who were members of AgriSA, thus excluding farmers belonging to other farmers’ unions, such as the Transvaal Agricultural Union of South Africa (TAU SA), the African Farmers’ Association of South Africa (AFASA) and the National African Farmers’ Union (NAFU). The numbers of farmers referred to in Table 1 is an estimate and not an exact figure. Furthermore, most farmers (commercial, emerging or subsistence do not belong to organised agricultural unions.

The HDI compares 159 countries in the world. Australia, with a rate of 0.939, falls within the top five countries of the world and boasts a very high human development group. South Africa, with a rate of 0.699 is number 113 of the compared countries, falling within the medium human development and the bottom half of development. The African continent has the lowest HDI of all continents, with an average HDI of 0.536. South Africa is in the ninth position of the HDI of the continent. South Africa is the country in the world showing the highest inequality, with a Gini coefficient21 of 0.633 and with 55 per cent of the population living in poverty. Differences in development are significant between the two countries but there is little convincing evidence on the causal effect of inequality on crime in developing countries.22

In Australia, reliable rural crime and agricultural crime statistics are only available on a state by state basis. For this study, the statistics for NSW have been used. South African rural crime statistics are available for the whole country

Though statistics may be available, methodological difficulties when comparing crime rates include:

The above factors are applicable more to some crimes than to others and, in selected cases, most notably in homicide, comparisons are safer.25

In conducting the study, these methodological difficulties were taken into account, and the author utilised historical information and permissions from the authors of the original papers to use their information to eliminate most of the challenges that the research methodology approach poses.

The prisoner population rate and homicide rate are used as indicators of the overall human security with reference to crime, shown in Table 1.26

The HDI counts the average incarceration rate per 100,000 of the general population for very high human development countries as 284 and for medium human development countries as 66 per 100, and the world average is 143. The rate in Australia is low compared to the average of other very high human development countries and just above the world average. South Africa has a very high incarceration rate when compared to both averages of medium human development countries and the world. The incarceration rate is an indication of the punitiveness prevalent in a society, albeit an imperfect measurement. The rate of incarceration, nevertheless, provides an overall assessment of the scale of punishment that a society is willing to impose on offenders.27

The HDI average homicide per 100,000 of the general population for very high human development countries is 3.2 and for medium human development countries it is 4.5, and the world average of 5.4. Australia has a low rate compared to both the average of other very highly developed countries and the world average. The homicide rate is not a security indicator, although it is the best indicator of violence in a society because it is the best recorded crime.28 South Africa has a very high homicide rate compared to the average of both medium human development countries and the world. It has the highest homicide rate in Africa and is ranked 12th in the world, below Latin American countries. Clearly, South Africa has a violent society because this trend is also prevalent in other contact rural crimes in South Africa.

Globally, attempts to define rural areas have posed a predicament. Anderson stated in 1999 that the term ‘rural’ can be easily understood at a common-sense level but is difficult, if not impossible, to define for research purposes.29 This predicament contributes to academia and government agencies embracing multiple, ambiguous, confusing and contradictory descriptors and conceptualisations of the concept of ‘rural’ means.30 Consequently, within social sciences, a trend has developed to move away from defining urban and rural areas,31 and, instead, adopt a degree of flexibility in the definitions of ‘rural’ and ‘rural crime’s to make data and discussions comparable.32

One of the first attempts to define rural areas in 1998 suggested it be done by considering population size, density and geographical location, including remoteness.33 In South Africa, definitions are based on settlement typologies that classify cities and towns in the country based on size, function and institutional legacy.34 In criminological research ‘“Rural” refers to those places with a lower population size and population density than urban localities”.35 The definition of ‘rural crime’ has similarly suffered varied definitions, one being that rural crime should be defined according to a range of demographical, economic, social and cultural factors, including the ideological perspectives of different bodies involved in rural crime enforcement or policies.36

Australia (NSW) and South Africa have formal operational criminal justice definitions for rural crimes. The NSW Police utilise the following definition: ‘Agricultural crimes are incidents of crime that impact on the pastoral, agricultural and aquaculture industries and are referred to as rural crimes’37 The South African Police Service (SAPS) define rural areas as:

[T]he sparsely populated areas in which people farm or depend on natural resources, including the villages and small towns that are dispersed through these areas. In addition, they include the large settlements in the former homelands, created by the apartheid removals, which depend for their survival on migratory labour and remittances.38

The NSW Police definition is brief and specific, whereas the definition used in South Africa includes historical considerations and are more aligned to the definition used in the US, where a city or town that has a population of more than 50,000 inhabitants and the urbanised areas contiguous and adjacent to such a city or town, is excluded. In England, Wales and Scotland, any town or village with fewer than 10,000 residents are classified as being ‘rural’, that is, a non-metropolitan area.

Regardless of the wording, it the three basic elements of demographics, economics, social and cultural determinants that underpin definitions.

The demographic determinant refers to the number of people concentrated in an area and location. Generally, rural areas are geographically isolated and physically removed from major urban centres with low population densities. Poor surveillance and the absence of people increase the opportunities for crimes.39 In South Africa, the term ‘rural’ is normally used to denote communities in country districts (die platteland) outside of urban or peri-urban communities.40 In Australia, the common term is ‘the bush’ without really identifying the exact location.41

The economic determinant associated with the primary economic activity of a demographic area as rural, is dominated by a ‘country lifestyle’ based on agricultural activities. Rural crimes in economic terms directly affect farming livelihoods and rural economies; livestock and crop theft as well as environmental and wildlife crimes are examples of crimes committed on property.42

The social determinant of rurality relates to a variety of characteristics such as intimacy, informality and homogeneity. According to the cultural determinant, people residing in rural areas are more traditional and conservative in their political outlooks.43 Hence, understanding similarities and differences in expressions of crime in rural and urban places is important.

Given the comparative nature of the paper and the overlapping aspects of the definitions used in Australia (NSW) and in South Africa, the primary focus of this paper will be on agricultural crimes committed on farms in the respective countries.

Table 2 lists the general and rural area indicators of the two countries. The information is later used to calculate the ratio in the comparative analysis.

Table 2 shows that Australia is geographically larger than South Africa with South Africa only comprising 15.84 per cent of the land size of Australia. The land area available for farming and the size of agriculture in the countries are more comparable; South Africa farms are equivalent of 27.7 per cent of the Australian continent, with most of the farming being done on the eastern side of the country. Agriculture in the state of NSW comprises 65 million hectares of farmland, which constitute about 80 per cent of the farmland in South Africa, providing a more reliable (but not necessarily perfect) unit of analysis.

In both countries, agriculture comprises mainly beef cattle, sheep and grain, or a mixture of two or more of these enterprises. Beef cattle production is the most common enterprise in both countries, comprising one-third of all farm operations in Australia and 76 per cent of all farming operations in South Africa. The higher number in South Africa is because 68.6 per cent of the total land comprises suitable grazing land.44

In South Africa, more people (5.6%) are economically dependent on agriculture. In Australia 99 per cent of farming operations are family owned45 and the number of people per farm is 3.55, meaning that one person is responsible for 1,200 hectares of farmland. In South Africa, different farming enterprises are used as business models and the number of people per farming unit is 21.86, meaning that one person is responsible for 103 hectares. Naturally, different farming commodities require different human resources and technical resources, these numbers are, therefore, a generalisation; for example, in the more arid areas there are few people per square kilometre while in highly productive farming areas there are many more. However, the comparison is not too outrageous since the number of people living in rural areas and making a living out of agriculture is very different in the two countries, with 14 per cent in Australia and 34 per cent in South Africa. A feature of both countries is that, from west to east, the population of people and rainfall increases. South Africa has seven climatic regions, ranging from Mediterranean to subtropical to semi-desert, based on rainfall patterns.46 In Australia, 88 per cent of the population lives along the eastern seaboard between the cities of Brisbane and Melbourne, and along the south-west coast of Western Australia.47 The population of South Africa is concentrated in Gauteng, in the municipalities of Johannesburg, Tshwane and Ekurhuleni, situated in the centre of the country, and on the east coast.48 These differences are of cardinal importance because rates of crime are related to the size of an area, be it urban or rural population.49

Comparing the victimisation rate of agricultural crimes between the two countries is vested in the following quote:

Criminology as a discipline has profited immensely from internationalisation and globalisation over the past few decades. Even if criminal justice and criminology are still ‘parochial’ in their perspectives, the ways in which we perceive and position ourselves are increasingly informed by how we compare ourselves to others.50

Agricultural crimes in this paper refer to ‘predatory violations’, meaning those illegal acts in which someone definitely and intentionally takes or damages the person or the property of another.51 The definition is two-pronged: crimes against the person (contact crimes) and economic (property and environmental) crimes. All studies with a rural focus – except studies conducted in South Africa – analysing agricultural crimes focus on one segment of predatory violations, namely economic crimes, which are divided into property and environmental crimes. Property crimes refer to an array of commodity theft, for example, livestock, grain, wool, fruit, vegetables or fish and oyster theft. Burglary of rural premises, associated with the theft of agricultural machinery, tools, equipment, fuel and fertilisers, is also included in this category. Environmental crimes refer to the vandalising of crops and farm infrastructure as well as illegal dumping of waste, theft of water from irrigation systems or timber from farms and state forests.52 In South Africa, a highly emotional and politicised crime known as farm attacks,53 referring to damages of the person (contact crimes), is an imperative inclusion in the paper, although not measured in other countries in the world. Farm attacks are persistent in rural areas and they involve all contact crimes – crimes against the person, for example, murder, rape, assault and culpable homicide.54 As economic crimes are more general and measured in both countries, they are first analysed and only then are the crimes against the person discussed.

Table 3 shows comparative statistics on property and environmental crimes in Australia (NSW) and in South Africa. The differences between the victimisation rates in the two countries are also shown.

* E Barclay, ‘The Context of Farm Crime in Australia’ (2018) 31(4) Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology

** D Tustin and C Van Aardt, ‘Agri SA 2018 National Agricultural Sector Crime Survey’ (Bureau of Market Research, University of South Africa, October 2018)

Variation in crime rates in different demographic environments, for example countries, urban, rural etc, has been recognised over a long period.55 The figures in Table 3 indicate that for all the crimes measured, South Africa has a much higher agricultural crime victimisation rate than Australia (NSW), except for theft of game and illegal hunting. On average, Australian (NSW) farmers experience 17 per cent victimisation related to property crimes, compared to a rate of 26 per cent in South Africa. The reasons that South Africa is experiencing more agricultural crimes in all the categories of property and environmental crimes than Australia require inductive generalisation. Although the victimisation rates of all the crimes are not that dissimilar, with a 9 per cent difference, specific crimes do show considerable differences. The victimisation rates of ten crimes are shown in Table 3, with theft of farm infrastructure (33%), theft of game and illegal hunting (31%), theft of agricultural inputs, for example, seeds, fertilisers and pesticides (19%), malicious damage to farm property (13%), and theft of livestock theft (13%) being the five showing the most differences.

The theft of game as well as illegal hunting in Australia (NSW) is a major problem, with 59 per cent of farmers experiencing the crime, compared to 28 per cent in South Africa. When the theft of game and illegal hunting is excluded from the analysis – as these are the only crimes more prevalent in Australia (NSW) – the average exposure to victimisation changes considerably. In Australia (NSW), the average victimisation rate then drops to 12 per cent, meaning that South African farmers are victimised at double the rate of Australian (NSW) farmers.

The data in Table 2 are also explanatory of this phenomenon: In South Africa, many more people (34% compared to 14% in Australia) are living in rural areas and many more people are employed in agriculture in South Africa than in Australia. These contrasts in patterns of settlement affect crime and justice in important ways that have been neglected in research.56 In South Africa, small towns, according to the definition of rural areas, have informal settlements (shanties) situated close to them, with extremely high numbers of uneducated people, high levels of poverty and high levels of unemployment that bear directly on high rates of crime.57 In Australia, 90% of people completed at least secondary education, compared to 75.7 per cent of people in South Africa. In 1996, 55 per cent of people living in rural areas in South Africa were illiterate and, at present, the illiteracy rates are still extremely high.58

South Africa, as a medium human development country, has one of the highest unemployment rates in the world at 27.7 per cent, which disproportionately affects youth living in rural areas.59 Australia, on the other hand, has a low unemployment rate of 5.7 per cent, compared to South Africa and other countries in the world.60 There is a direct relationship between unemployment and poverty.61 Poverty as a relative concept describes the situation in which some people in society cannot afford the essentials that most people in that society take for granted. In 2012, 13.9 per cent of the total population in Australia lived in households with an income of below the Australian poverty line, which means a disposable income of less than A$400 per week for a single adult and less than A$841 per week for a couple with two children.62 By comparison, more than half of South Africans (55.5%, 30 million people) live below the national poverty line of R992 (A$94) per month.63 Poverty is consistently higher among South Africans living in rural areas, with 65.4 per cent of the population living below the poverty line in 2015. This is not a rare occurrence, as rural areas in medium and low HDI countries are often characterised by high rates of poverty and food insecurity.64 The relationship between income inequality and crime is important because researchers have generally found that poverty and its associated disadvantages have a substantial positive effect on crime rates that can contribute to understanding why agricultural crimes are more prevalent in South Africa.65 From a routine activity theory perspective, poverty leads to a high proportion of motivated offenders who are frustrated by their lack of money in a money-centred society, contributing to increased economic crimes.66

All the economic crimes referred to in this category can be committed in urban and rural areas, except for livestock theft and the theft of game, which can only be committed on farms or in national parks. Because livestock theft is measured in both countries, it is now discussed.

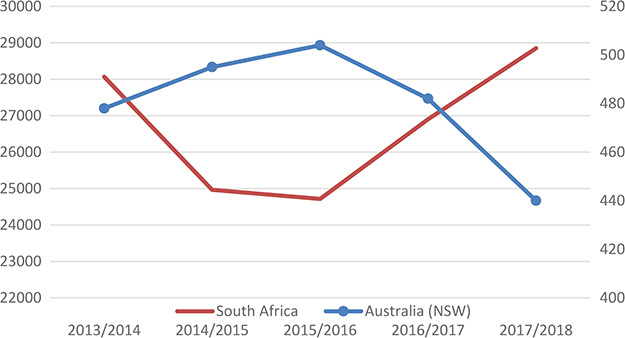

As seen from Table 3, farmers in both countries are victims of high rates of livestock theft, which is the most prevalent crime in rural areas. Figure 1 shows the number of cases per year in Australia (NSW)67 and in South Africa68. The number of livestock theft cases is higher in South Africa than in Australia (NSW).

Figure 1 Number of cases per year in Australia (NSW) and in South Africa

The Stock Theft Act (Act 57 of 1959) in South Africa deals with this type of crime. In Australia (NSW), livestock theft is dealt with in terms of section 126 of the NSW Crimes Act 1900 (NSW).69

Note that the data sets of the two countries are not directly comparable since the statistics for Australia (NSW) are calculated from October to September each year, while the statistics from South Africa are taken from April to March each year. Irrespective of this challenge, it is obvious that the number of cases differs immensely. Another predicament is the fact that the real number of farmers in South Africa is not known because of poor measurement; therefore, the calculation of rates cannot provide conclusive information.

Table 4 shows agricultural crimes committed and measured in Australia (but not in the BMR study).

| Theft of fuel | 23% |

| Dumping of rubbish or waste on farmland | 13% |

| Theft of timber | 7% |

| Growing of cannabis or other drugs | 3% |

Although the victimisation rates of fuel theft and timber theft are not measured in South Africa, they are also prevalent crimes. Farmers are constantly warned against rising fuel thefts because these thefts cripple agricultural operations.70 Although the timber industry in South Africa is buckling under timber and related theft, the authorities are seemingly unperturbed by the rise in these increasingly sophisticated environmental crimes. The theft of timber has become such a problem that a timber theft forum was established to discuss the issue.71

Table 5 summarises the statistics for violent crimes affecting farmers in South Africa. Many studies in South Africa have focused on violent crimes committed on farms because the murder of farmers is a highly emotional issue, with the modus operandi differing widely.72 Australia does not measure violent crimes committed in rural areas, but it is fair to say that it does exist in Australia because rates of violence are, on average, higher per capita in regional and rural communities.73 Nevertheless, with regard to homicide, it is evident that South Africa is a much more violent society than is Australia.

| Robbery | 25.1% |

| Assault | 5.7% |

| Attempted murder | 1.3% |

| Rape | 1.1% |

| Murder | 1% |

| Culpable homicide | 0.9% |

Source: D Tustin and C Van Aardt, ‘Agri SA 2018 National Agricultural Sector Crime Survey’ (Bureau of Market Research, University of South Africa, October 2018).

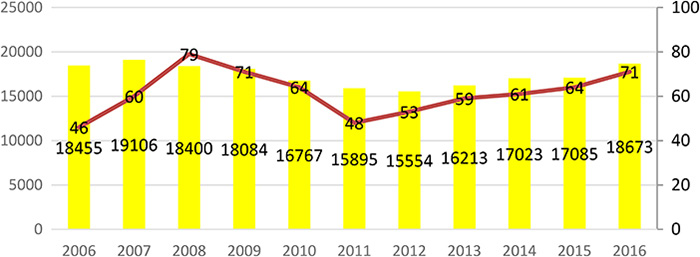

Figure 2 shows a comparison of the number of murders in the general population to murders on farms and in rural areas. Owing to this unequal distribution, it is not practical or possible to compare the crimes per 100,000 of the population.74 The data shown in Figure 2 indicates that the trendline between rural and urban is in equilibrium, although the numbers of murders differ significantly with much more murders in urban than rural areas.

In Australia (NSW), the overall population murder rate is generally even lower than the murder rate for farmers in South Africa.

Figure 2 Comparing the number of murders in the general population (Yellow bars) to murders on farms and in rural areas (red line)

This paper compared crimes committed in Australia (NSW) and South Africa and discussed the associated challenges when making such comparisons. The social sciences forget that towns were originally developed to escape rural banditry and have thus largely neglected carrying out research into crime in rural areas, even despite the fact that recent studies have found rural crimes are a concern in most countries.

The HDI of Australia (NSW) to that of South Africa shows that South Africa has a much lower development level than Australia, particularly regarding levels of education, poverty and inequality.

Australia and South Africa have overlapping aspects in the respective definitions of rural crime victimisation rates, highlighting demographic and economic determinants. Australia is geographically a much larger country than South Africa, but agricultural comparisons are possible when using data from the state of NSW and South Africa. In both countries, agriculture comprises mainly beef cattle, sheep and grain farming, or a mixture of two or more of these enterprises. Findings from the study are that the agricultural crime victimisation rate in South Africa is double that of Australia (NSW) except for theft of game and illegal hunting.

It was difficult to compare violent crimes committed on farms because Australia (NSW) does not specifically collect data on violent rural crime. Nevertheless, the overall murder rate in Australia is lower than the rate of murders of farmers in South Africa.

In South Africa, more people live in rural areas and are employed in agriculture than in Australia. Rural areas in South Africa have high numbers of uneducated people, high poverty levels and high levels of unemployment, all of which have a bearing on the high rates of crime in the country.

Australian Institute of Criminology, ‘Comparing International Trends in Recorded Violent Crime’, (2006) <https://aic.gov.au/publications/cfi/cfi115>

Barclay, E, ‘A Review of the Literature on Agricultural Crime’ (2001) Institute of Rural Futures, New South Wales, Australia: University of New England. http://criminology.fsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/A-Review-of-the-Literature-on-Agricultural-Crime.pdf

Barclay, E, ‘Research Rural Crimes’ (E-mail Letter 25 September 2016)

Barclay, Elaine, ‘‘Farm Victimisation: The Quintessential Rural Crime’ in Joseph F Donnermeyer (ed), The Routledge International Handbook of Rural Criminology (Routledge, 2016) 107

Barclay, E, ‘The Context of Farm Crime in Australia’ (2018) 31(4) Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology

Bashir, AM, RB Yusof and T Azlizan, ‘Cattle Rustling and Insecurity in Rural Communities of Kaduna State, Nigeria: An Empirical Study’ (2018) 6(5) Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies <http://www.ajms.co.in/sites/ajms2015/index.php/ajms/article/view/3046>

Bowen, GA, ‘Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method’ (2009) 9(2) Qualitative Research Journal 27.

Brooke ‘Poverty in Rural Australia’, Australian Rotary Health <https://australianrotaryhealth.org.au/poverty-in-rural-australia/>

Ceccato, VA, Rural Crime and Community Safety ( Routledge, 2016)

Chibba, M, and J Luiz, ‘Poverty, Inequality and Unemployment in South Africa: Context, Issues and the Way Forward’ (2011) 30(3) Economic Papers: A Journal of Applied Economics and Policy 307.

Clack, W, and A Minnaar, ‘Rural Crime in South Africa : An Exploratory Review of “Farm Attacks” and Stocktheft as the Primary Crimes in Rural Areas’ (2018) 31(1) Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology 103.

Carrington, K, and R Hogg, ‘History of Critical Criminology in Australia’ in Routledge Handbook of Critical Criminology (Routledge, 2013) <https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9780203864326>

Clack, W, ‘Livestock Theft a Global and South African Perspective’ (Red Meat Producers’ Organisation Conference, Pretoria, 2018). http://www.stocktheftprevent.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Livestock-Theft-Report-2018-Final.pdf

Cohen, LE, and M Felson, ‘Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach’ (1979) American Sociological Review 588, 588

Coomber, R, et al, ‘Key Concepts in Crime and Society’, Sage (2015) <http://sk.sagepub.com/books/key-concepts-in-crime-and-society>

Digit Western Cape, ‘Farm Fuel Theft Warning as Darker Nights Close In’, Track :: Monitor :: Manage, 24/7! <http://www.digitwesterncape.co.za/farm-fuel-theft-warning-as-darker-nights-close-in/>

Donnermeyer, J, ‘The Social Organisation of the Rural and Crime in the United States: Conceptual Considerations’ (2015) 39 Journal of Rural Criminology 160

Donnermeyer, JF, ‘Rural Criminology TimeLine’ (E-mail Letter, 19 December 2018)

Enamorado, T, et al, ‘Income Inequality and Violent Crime: Evidence from Mexico’s Drug War’ (2016) 120 Journal of Development Economics 128

Felson, M, and LE Cohen, ‘Human Ecology and Crime: A Routine Activity Approach’ (1980) 8(4), Human Ecology 389, 390.

Felson, M, and RV Clarke, ‘Opportunity Makes the Thief: Practical Theory for Crime Prevention, Policing and Reducing Crime Unit: Police Research Series (1998) 4 <https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/09db/dbce90b22357d58671c41a50c8c2f5dc1cf0.pdf>

Fernholz, T, ‘The World Bank is Eliminating the Term ‘Developing Country’ from its Data Vocabulary’, Quartz <https://qz.com/685626/the-world-bank-is-eliminating-the-term-developing-country-from-its-data-vocabulary/>.

Forestry South Africa, ‘Waves of Crime Crippling the Timber Industry’ (18June 2014) <http://www.forestry.co.za/waves-of-crime-crippling-the-timber-industry/>.

Ghani, ZA, ‘A Comparative Study of Urban Crime Between Malaysia and Nigeria’ (2017) 6(1) Journal of Urban Management 19, 20 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2017.03.001

Gous, N, ‘SA Most Unequal Country in World: Poverty Shows Apartheid’s Enduring Legacy’ <https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2018-04-04-poverty-shows-how-apartheid-legacy-endures-in-south-africa/>.

Grote, U, and F Neubacher, ‘Rural Crime in Developing Countries: Theoretical Framework, Empirical Findings, Research Needs’ (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2756542, Social Science Research Network, 1 March 2016) 2 <https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2756542>

Hannon, L, ‘Criminal Opportunity Theory and the Relationship Between Poverty and Property Crime’ (2002) 22(3) Sociological Spectrum 363, 363.

Hogg, R, and K Carrington, ‘Crime, Rurality and Community’ (1998) 31 Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology <http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-0032391165&partnerID=40&md5=52e505ff12ada915750a1a1196c74f5c>

Hogg, R, and K Carrington, ‘Policing the Rural Crisis’ (2006) 38(3) Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology

Karstedt, S, ‘Comparing Justice and Crime Across Cultures’ in The SAGE Handbook of Criminological Research Methods (SAGE Publications, 2012) 373 <http://methods.sagepub.com/book/sage-hdbk-criminological-research-methods/n25.xml>

Kelly, M, ‘Inequality and Crime’ (2000) 82(4) The Review of Economics and Statistics 530, 530. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465300559028

Ken, J, M Leitner and A Curtis, ‘Evaluating the Usefulness of Functional Distance Measures when Calibrating Journey-to-Crime Distance Decay Functions’ (2006) 30 Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 181, 182 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2004.10.002

Laldaparsad, S, ‘Urban and Rural Trends in South Africa’ (2013) Statistics South Africa 1 <https://www.statistics.gov.hk/wsc/CPS101-P5-S.pdf>

Lam, D, M Leibrandt and C Mlatsheni, ‘Human Capital, Job Search, and Unemployment Among Young People in South Africa; Cape Town: 2010’ (2010) <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228950917_Human_Capital_Job_Search_and_Unemployment_among_Young_People_in_South_Africa>

Louw, A, ‘A Framework for Solving Farm Attacks?’ (1998) 2(5) Nedcor/ISS Crime Index 5, 7.

Marshall, B, and S Johnson, ‘Crime in Rural Areas: A Review of the Literature for the Rural Evidence Research Centre’. Hildebrand 7 <http://public.hildebrand.co.uk/rerc/findings/documents_reviews/Rev2RuralCrime.pdf>

Mauer, M, ‘Incarceration Rates in an International Perspective’, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice (2017) <http://oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264079-e-233>

McKechnie, G, and G Worboys, ‘Rural Crime Prevention in New South Wales’ (Conference presentation: Rural Crime and the Law, UNE 30 November 2018)

Newman, L, ‘Poor Literacy Levels Still a Concern in SA’, Daily News (2018) <https://www.iol.co.za/dailynews/poor-literacy-levels-still-a-concern-in-sa-14601496>

Nolan, JJ, ‘Establishing the Statistical Relationship Between Population Size and UCR Crime Rate: Its Impact and Implications’ (2004) 32(6) Journal of Criminal Justice 547 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2004.08.002

NSW Department of Justice, Crime statistics (2018) <https://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au:443/Pages/bocsar_crime_stats/bocsar_crime_stats.aspx>

Nurse, A, Interpreting Rurality: Multidisciplinary Approaches (Routledge, 2013) 205

Pachico, E, ‘Why it’s Important to Visualize Homicide Data’, InSight Crime (29 May 2015) <https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/why-its-important-to-visualize-homicide-data/>.

Red Meat Research and Development South Africa, ‘Overview of the Industry’ (2018) <http://www.rmrdsa.co.za/REDMEATINDUSTRY/OverviewoftheIndustry.aspx>

Reynolds, J, ‘Difference Between Developing Countries and Emerging Countries’, Bizfluent (2018) <https://bizfluent.com/info-10002682-difference-between-developing-countries-emerging-countries.html>.

‘Rise in Diesel and Petrol Thefts off Farms’ Nelspruit Post (6 November 2018) <https://nelspruitpost.co.za/272437/rise-diesel-petrol-thefts-off-farms/>

Rossmo, K, ‘Geographic Profiling,’ CRC Press (1999) 111 <https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781420048780>

Ryan, ‘The Mistake of Only Comparing US Murder Rates to “Developed” Countries’, Mises Institute (12 October 2015) <https://mises.org/wire/mistake-only-comparing-us-murder-rates-developed-countries>

Smith, R, EK Bunei and G McElwee, ‘From Bush to Butchery: Cattle Rustling as an Entrepreneurial Process in Kenya’ (2016) 11(1) Society and Business Review 46. https://doi.org/10.1108/sbr-10-2015-0057

South African Police Service, ‘National Rural Safety Strategy’ (2011) <https://africacheck.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Rural-Safety-Strat.pdf>

Statistics South Africa ‘Statistical Release (revised) Census 2011’ (2012) 15

Sulla, V, and P Zikhali, ‘Overcoming Poverty and Inequality in South Africa: An Assessment of Drivers, Constraints and Opportunities’ The World Bank (22 March 2018) 124521, 1 xix <http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/530481521735906534/Overcoming-Poverty-and-Inequality-in-South-Africa-An-Assessment-of-Drivers-Constraints-and-Opportunities>

Swart, D, ‘Farm Attacks in South Africa: Incidence and Explanation’ (2003) 16(1) Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology 40.

Tekeli, S, and G Günsoy, ‘The Relation Between Education and Economic Crime: An Assessment for Turkey’ (2013) 106 Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 3012, 3013

Tennant, J, ‘SA’s Key Economic Sectors’, Brand South Africa (2 January 2018) <https://www.brandsouthafrica.com/investments-immigration/business/investing/economic-sectors-agricultural>.

Tshabalala, NG, ‘Crime and Unemployment in South Africa; Revisiting an Established Causality: Evidence from the KwaZulu-Natal Province’ (2014) 15(5) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 519, 519

Tustin, D, and C Van Aardt, ‘Agri SA 2018 National Agricultural Sector Crime Survey’ (Bureau of Market Research, University of South Africa, October 2018)

UN Office of Drugs and Crime (UNDOC), ‘Compiling and Comparing International Crime Statistics’, (2019) <https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/Compiling-and-comparing-International-Crime-Statistics.html>.

UNDP ‘Training Material for Producing National Human Development Reports’ <http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdi_training.pdf>

United Nations Development Programme, ‘UN Human development indices and indicators (2018)’, <https://www.onlinegk.com/download/2018_human_development_statistical_update.pdf>

Warchol, GL, and BR Johnson, ‘Securing National Resources from Theft: An Exploratory Theoretical Analysis’ (2011) 6(3) Journal of Applied Security Research 273, 274 https://doi.org/10.1080/19361610.2011.580257

Weisheit, RA, DN Falcone DN and LE Wells, Crime and Policing in Rural and Small-Town America (Waveland Press, 3rd ed, 1999)

Weisheit, RA, and J Donnermeyer, ‘Change and Continuity in Crime in Rural America’ (2000) 1 The Nature of Crime: Continuity and Change 310

Weisheit, RA, DN Falcone and LE Wells, Crime and Policing in Rural and Small-Town America (Waveland Press, 3rd ed, 2005) 3

Wilkinson, K, ‘FACTSHEET: Statistics on Farm Attacks and Murders in South Africa’ Africa Check <https://africacheck.org/factsheets/factsheet-statistics-farm-attacks-murders-sa/>

Wilkinson, A, et al, ‘The Employment Environment for Youth in Rural South Africa: A Mixed-Methods Study’ (2017) 34(1) Development Southern Africa 17

Wortley, R, and L Mazerolle, Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis (Routledge, 2013) 1

1 JF Donnermeyer ‘Rural Criminology TimeLine’ (E-mail Letter, 19 December 2018)

2 R Smith, EK Bunei and G McElwee, ‘From Bush to Butchery: Cattle Rustling as an Entrepreneurial Process in Kenya’ (2016) 11(1) Society and Business Review 46.; AM Bashir, RB Yusof and T Azlizan, ‘Cattle Rustling and Insecurity in Rural Communities of Kaduna State, Nigeria: An Empirical Study’ (2018) 6(5) Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies <http://www.ajms.co.in/sites/ajms2015/index.php/ajms/article/view/3046>.; W Clack and A Minnaar, ‘Rural Crime in South Africa : An Exploratory Review of “Farm Attacks” and Stocktheft as the Primary Crimes in Rural Areas’ (2018) 31(1) Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology 103.

3 U Grote and F Neubacher, ‘Rural Crime in Developing Countries: Theoretical Framework, Empirical Findings, Research Needs’ (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2756542, Social Science Research Network, 1 March 2016) 2 <https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2756542>.

4 VA Ceccato, Rural Crime and Community Safety ( Routledge, 2016).

5 T Fernholz, ‘The World Bank is Eliminating the Term ‘Developing Country’ from its Data Vocabulary’, Quartz <https://qz.com/685626/the-world-bank-is-eliminating-the-term-developing-country-from-its-data-vocabulary/>.

6 J Reynolds, ‘Difference Between Developing Countries and Emerging Countries’, Bizfluent (2018) <https://bizfluent.com/info-10002682-difference-between-developing-countries-emerging-countries.html>.

7 Ryan, ‘The Mistake of Only Comparing US Murder Rates to “Developed” Countries’, Mises Institute (12 October 2015) <https://mises.org/wire/mistake-only-comparing-us-murder-rates-developed-countries>

9 UNDP ‘Training Material for Producing National Human Development Reports’ <http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdi_training.pdf>.

10 K Rossmo, ‘Geographic Profiling,’ CRC Press (1999) 111 <https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781420048780>.

11 R Wortley and L Mazerolle, Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis (Routledge, 2013) 1.

12 J Ken, M Leitner and A Curtis, ‘Evaluating the Usefulness of Functional Distance Measures when Calibrating Journey-to-Crime Distance Decay Functions’ (2006) 30 Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 181, 182.

13 M Felson and RV Clarke, ‘Opportunity Makes the Thief: Practical Theory for Crime Prevention, Policing and Reducing Crime Unit: Police Research Series (1998) 4 <https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/09db/dbce90b22357d58671c41a50c8c2f5dc1cf0.pdf>.

14 LE Cohen and M Felson, ‘Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach’ (1979) American Sociological Review 588, 588.

15 GL Warchol and BR Johnson, ‘Securing National Resources from Theft: An Exploratory Theoretical Analysis’ (2011) 6(3) Journal of Applied Security Research 273, 274.

16 E Barclay, ‘The Context of Farm Crime in Australia’ (2018) 31(4) Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology.

17 GA Bowen ‘Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method’ (2009) 9(2) Qualitative Research Journal 27.

18 E Barclay, ‘Research Rural Crimes’ (E-mail Letter 25 September 2016).

19 AgriSA is an agricultural union in South Africa, representing commercial farmers in the whole country.

20 D Tustin and C Van Aardt, ‘Agri SA 2018 National Agricultural Sector Crime Survey’ (Bureau of Market Research, University of South Africa, October 2018).

21 Gini index measures the degree of inequality in the distribution of family income in a country.

22 T Enamorado et al, ‘Income Inequality and Violent Crime: Evidence from Mexico’s Drug War’ (2016) 120 Journal of Development Economics 128.

23 Australian Institute of Criminology, ‘Comparing International Trends in Recorded Violent Crime’, (2006) <https://aic.gov.au/publications/cfi/cfi115>; ZA Ghani, ‘A Comparative Study of Urban Crime Between Malaysia and Nigeria’ (2017) 6(1) Journal of Urban Management 19, 20.

24 S Tekeli and G Günsoy, ‘The Relation Between Education and Economic Crime: An Assessment for Turkey’ (2013) 106 Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 3012, 3013.

25 UN Office of Drugs and Crime, ‘Compiling and Comparing International Crime Statistics’, (2019) <https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/Compiling-and-comparing-International-Crime-Statistics.html>.

26 United Nations Development Programme (UNDOC), ‘UN Human development indices and indicators (2018)’, <https://www.onlinegk.com/download/2018_human_development_statistical_update.pdf>.

27 M Mauer, ‘Incarceration Rates in an International Perspective’, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice (2017) <http://oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264079-e-233>.

28 E Pachico, ‘Why it’s Important to Visualize Homicide Data’, InSight Crime (29 May 2015) <https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/why-its-important-to-visualize-homicide-data/>.

29 B Marshall and S Johnson, ‘Crime in Rural Areas: A Review of the Literature for the Rural Evidence Research Centre’. Hildebrand 7 <http://public.hildebrand.co.uk/rerc/findings/documents_reviews/Rev2RuralCrime.pdf>; RA Weisheit, DN Falcone and LE Wells, Crime and Policing in Rural and Small-Town America (Waveland Press, 3rd ed, 2005) 3; RA Weisheit and J Donnermeyer, ‘Change and Continuity in Crime in Rural America’ (2000) 1 The Nature of Crime: Continuity and Change 310, 311.

30 J Donnermeyer, ‘The Social Organisation of the Rural and Crime in the United States: Conceptual Considerations’ (2015) 39 Journal of Rural Criminology 160, 161.

31 A Louw, ‘A Framework for Solving Farm Attacks?’ (1998) 2(5) Nedcor/ISS Crime Index 5, 7.

32 Weisheit, Falcone and Wells (n 29) 3.

33 R Hogg and K Carrington, ‘Crime, Rurality and Community’ (1998) 31 Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology <http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-0032391165&partnerID=40&md5=52e505ff12ada915750a1a1196c74f5c>.

34 S Laldaparsad, ‘Urban and Rural Trends in South Africa’ (2013) Statistics South Africa 1 <https://www.statistics.gov.hk/wsc/CPS101-P5-S.pdf>.

35 R Coomber et al, ‘Key Concepts in Crime and Society’, Sage (2015) <http://sk.sagepub.com/books/key-concepts-in-crime-and-society>.

36 A Nurse, Interpreting Rurality: Multidisciplinary Approaches (Routledge, 2013) 205; RA Weisheit, DN Falcone DN and LE Wells, Crime and Policing in Rural and Small-Town America (Waveland Press, 3rd ed, 1999).

37 G McKechnie and G Worboys, ‘Rural Crime Prevention in New South Wales’ (Conference presentation: Rural Crime and the Law, UNE 30 November 2018); South African Police Service, ‘National Rural Safety Strategy’ (2011) <https://africacheck.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Rural-Safety-Strat.pdf>.

38 South African Police Service (n 37).

39 Grote and Neubacher (n 3) 3; Coomber et al (n 35) 117.

40 Clack and Minnaar (n 2) 105.

41 McKecknie and Worboys (n 37).

43 Weisheit, Falcone and Wells (n 29).

44 Red Meat Research and Development South Africa, ‘Overview of the Industry’ (2018) <http://www.rmrdsa.co.za/REDMEATINDUSTRY/OverviewoftheIndustry.aspx>.

45 Barclay, ‘The context of farm crime in Australia’ (n 16).

46 J Tennant, ‘SA’s Key Economic Sectors’, Brand South Africa (2 January 2018) <https://www.brandsouthafrica.com/investments-immigration/business/investing/economic-sectors-agricultural>.

47 Barclay ‘The Context of Farm Crime in Australia’ (n 16).

48 Statistics South Africa ‘Statistical Release (revised) Census 2011’ (2012) 15.

49 JJ Nolan, ‘Establishing the Statistical Relationship Between Population Size and UCR Crime Rate: Its Impact and Implications’ (2004) 32(6) Journal of Criminal Justice 547, 547.

50 S Karstedt, ‘Comparing Justice and Crime Across Cultures’ in The SAGE Handbook of Criminological Research Methods (SAGE Publications, 2012) 373 <http://methods.sagepub.com/book/sage-hdbk-criminological-research-methods/n25.xml>.

51 M Felson and LE Cohen, ‘Human Ecology and Crime: A Routine Activity Approach’ (1980) 8(4), Human Ecology 389, 390.

52 Elaine Barclay, ‘‘Farm Victimisation: The Quintessential Rural Crime’ in Joseph F Donnermeyer (ed), The Routledge International Handbook of Rural Criminology (Routledge, 2016) 107.

53 A word derived from the Afrikaans word ‘plaasaanval’ and unique to South Africa.

54 Clack and Minnaar (n 2) 108.

55 Felson and Cohen (n 51) 391.

56 K Carrington and R Hogg, ‘History of Critical Criminology in Australia’ in Routledge Handbook of Critical Criminology (Routledge, 2013) <https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9780203864326>.

57 NG Tshabalala, ‘Crime and Unemployment in South Africa; Revisiting an Established Causality: Evidence from the KwaZulu-Natal Province’ (2014) 15(5) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 519, 519.

58 L Newma, ‘Poor Literacy Levels Still a Concern in SA’, Daily News (2018) <https://www.iol.co.za/dailynews/poor-literacy-levels-still-a-concern-in-sa-14601496>.

59 A Wilkinson et al, ‘The Employment Environment for Youth in Rural South Africa: A Mixed-Methods Study’ (2017) 34(1) Development Southern Africa 17; D Lam, M Leibrandt and C Mlatsheni, ‘Human Capital, Job Search, and Unemployment Among Young People in South Africa; Cape Town: 2010’ (2010). <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228950917_Human_Capital_Job_Search_and_Unemployment_among_Young_People_in_South_Africa>.

61 M Chibba and J Luiz, ‘Poverty, Inequality and Unemployment in South Africa: Context, Issues and the Way Forward’ (2011) 30(3) Economic Papers: A Journal of Applied Economics and Policy 307.

62 Brooke ‘Poverty in Rural Australia’, Australian Rotary Health <https://australianrotaryhealth.org.au/poverty-in-rural-australia/>.

63 N Gous, ‘SA Most Unequal Country in World: Poverty Shows Apartheid’s Enduring Legacy’ <https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2018-04-04-poverty-shows-how-apartheid-legacy-endures-in-south-africa/>.

64 V Sulla and P Zikhali, ‘Overcoming Poverty and Inequality in South Africa: An Assessment of Drivers, Constraints and Opportunities’ The World Bank (22 March 2018) 124521, 1 xix <http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/530481521735906534/Overcoming-Poverty-and-Inequality-in-South-Africa-An-Assessment-of-Drivers-Constraints-and-Opportunities>.

65 M Kelly, ‘Inequality and Crime’ (2000) 82(4) The Review of Economics and Statistics 530, 530.

66 L Hannon, ‘Criminal Opportunity Theory and the Relationship Between Poverty and Property Crime’ (2002) 22(3) Sociological Spectrum 363, 363.

67 NSW Department of Justice, Crime statistics (2018) <https://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au:443/Pages/bocsar_crime_stats/bocsar_crime_stats.aspx>

68 W Clack, ‘Livestock Theft a Global and South African Perspective’ (Red Meat Producers’ Organisation Conference, Pretoria, 2018). http://www.stocktheftprevent.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Livestock-Theft-Report-2018-Final.pdf.

69 E Barclay, ‘A Review of the Literature on Agricultural Crime’ (2001) Institute of Rural Futures, New South Wales, Australia: University of New England. http://criminology.fsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/A-Review-of-the-Literature-on-Agricultural-Crime.pdf.

70 Digit Western Cape, ‘Farm Fuel Theft Warning as Darker Nights Close In’, Track :: Monitor :: Manage, 24/7! <http://www.digitwesterncape.co.za/farm-fuel-theft-warning-as-darker-nights-close-in/>; ‘Rise in Diesel and Petrol Thefts off Farms’ Nelspruit Post (6 November 2018) <https://nelspruitpost.co.za/272437/rise-diesel-petrol-thefts-off-farms/>.

71 Forestry South Africa, ‘Waves of Crime Crippling the Timber Industry’ (18June 2014) <http://www.forestry.co.za/waves-of-crime-crippling-the-timber-industry/>.

72 Clack and Minnaar (n 2); D Swart, ‘Farm Attacks in South Africa: Incidence and Explanation’ (2003) 16(1) Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology 40.

73 R Hogg and K Carrington, ‘Policing the Rural Crisis’ (2006) 38(3) Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology

74 K Wilkinson, ‘FACTSHEET: Statistics on Farm Attacks and Murders in South Africa’ Africa Check <https://africacheck.org/factsheets/factsheet-statistics-farm-attacks-murders-sa/>.