Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 18, No. 2

July 2025

Research article (peer-reviewed)

Youth Knowledge Mobilisation: Reflections on Theory and Practice

Jennifer Thompson1,*, Sarah L. Fraser2, Véronique Dupéré2, Nancy Beauregard3, Isabelle Archambault2, Josée Lapalme2, Katherine L. Frohlich4

1 Centre de recherche en santé publique, Université de Montréal, Canada

2 École de psychoéducation, Université de Montréal, Canada

3 École de relations industrielles, Université de Montréal, Canada

4 École de santé publique - Département de médecine sociale et préventive, Université de Montréal, Canada

Corresponding author: Jennifer Thompson, jennifer.thompson@umontreal.ca

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v18i2.9405

Article History: Received 18/10/2024; Revised 07/04/2025; Accepted 23/06/2025; Published 07/2025

Abstract

This article explores knowledge mobilisation in youth research. We take as a starting point that youth knowledge mobilisation (YKMb) requires specific strategies because of the unique power dynamics involved in mobilising knowledge related to young people. However, existing knowledge mobilisation models cannot account for these specificities. YKMb often requires co-creation with partner organisations as well as with youth themselves, leading to diverse and sometimes fragmented approaches to YKMb. An overarching discussion about the theory and practice of YKMb is missing from the literature. To explore the factors that influence the diversity of approaches to YKMb, we take up reflexivity to explore the experiences of a YKMb Chair working in intersectoral partnerships as well as with young people in Quebec, Canada. This article features an emergent YKMb framework that conceptualises a continuum of approaches to mobilising knowledge about, for, with and by youth. Across these modes of working, several factors influence YKMb in practice, from research paradigm and context as well as specificities regarding which actors are involved and why these different actors want to mobilise knowledge, as well as what roles different actors play in knowledge production and mobilisation. These factors influence the continuum of roles that academic researchers may play in YKMb, from more traditional roles as knowledge translators to engaged roles such as facilitators, advocates and learners. Conceptualising YKMb through continuums of practice offers critical insights to support intersectoral and interdisciplinary teams of academic researchers, partners and young people in research co-creation to better bridge the gap between research and practice.

Keywords

Knowledge Mobilisation; Partnership Research; Youth Participation; Youth Research; Continuums of Practice

Introduction

This article explores the theory and practice of knowledge mobilisation (KMb) in the context of research about young people. This area of ‘youth research’ is notoriously vast; young people’s lives span many disciplinary areas and spheres, necessitating a plurality of approaches to research, from longitudinal statistical work to in-depth qualitative and narrative studies and conceptual interrogations of childhood. What is more, paradigm shifts in recent decades have changed the landscape for youth participation, leading to increased involvement of young people as active knowers and agents within different stages of the research process. This constellation of research practices raises interesting questions about how to put this knowledge produced by youth research into use so that it might contribute to young people’s lives in a meaningful way. Drawing on our experiences doing KMb in different ways as part of a collaborative interdisciplinary chair focused on youth research, we suggest there are opportunities to think across these diverse ways of working to consider the significance of youth knowledge mobilisation (YKMb). Given the paucity of literature exploring YKMb as a field, we offer a broad definition of YKMb as ‘the mobilisation of research knowledge that pertains to the experiences, lives and positions of young people in society’.

The concept of KMb has gained momentum in recent decades and is now considered an important criterion, if not expectation, for good quality research. Through the process of producing and mobilising knowledge generated within research environments, KMb aims to bridge the gap between research and practice. Associated with concerns about research impact, KMb involves the exchange and integration of knowledge with the goal of better informing decision-making and practice so that research benefits society (Phipps et al. 2016). The term ‘KMb’ was introduced in Canada in the early 2000s by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and is based on the French term ‘mobilisation’, which draws on ideas about ‘making ready for service or action’ (SSHRC 2019, cited in Barwick, Dubrowski & Petricca 2019, p. 5). The concept builds on, overlaps with and integrates a range of concepts and terms leading to tensions in the literature about how to define it. For SSHRC, KMb is an umbrella terms that includes, for example, the one-way transfer of information associated with knowledge transfer, the adaptation of information for different knowledge users through knowledge translation (emerging from health sciences) and more interactive processes of knowledge exchange that involve knowledge users to a greater extent. Others suggest that KMb represents a more involved interactive process with knowledge users that requires building relationships and going beyond, for example, producing reports and articles. While this field continues to evolve heterogeneously in situated ways in different contexts and disciplines (Graham et al. 2006), we work with the idea that KMb offers an evolving concept and process for a range of approaches aimed at putting research into use. In Canada, the term KMb has particular significance because the federal funding agency in the social sciences and humanities (SSHRC) evaluates the merit of KMb plans in funding applications (SSHRC 2023), leading to increasingly critical questions from academic researchers (researchers employed by research institutions) about how to do KMb.

To facilitate KMb, it is widely encouraged to involve knowledge users within various research stages. Intersectoral collaboration or partnership research offers a mechanism whereby academic researchers work with non-academic partners to produce and mobilise knowledge together (Lavis et al. 2006; Phipps et al. 2016). Partners might include any range of actors, from private and non-profit organisations, practitioners and community members to governments, policymakers, decision-makers and young people themselves. It is accepted that collaborative approaches such as co-production, co-creation, and participatory research are effective processes for integrating the knowledge produced through research more easily within practice and decision-making. Indeed, decades of collaborative research involving knowledge users have perhaps been doing the work of KMb without necessarily using this term or explicitly focusing on the KMb aspect of the partnership process. At the same time, KMb differs from partnership research because KMb is explicitly concerned with putting research into use (whereas partnership research might have different objectives). Recent scholarly work comparing KMb models with collaborative approaches such as engaged scholarship, co-production, and community-based participatory research distinguishes, for example, different objectives, historical roots, and researcher roles (Jull et al. 2017; Nguyen et al. 2020). However, these theoretical reviews of the literature still leave questions for academic researchers working across the wide variety of research traditions that do not necessarily or traditionally involve non-academic partners. There is a need for more dedicated discussions across diverse research traditions about strategies for mobilising research findings with different groups of knowledge users, and how to navigate the realities and complexities of this work in practice.

In this context, KMb scholarship increasingly critiques pragmatic views of ‘common-sense’ methodological approaches to bringing academic researchers and non-academic partners together. Alongside a number of scoping reviews taking stock of the field (Golhasany & Harvey 2023; Ziam et al. 2024), more critical accounts of KMb need to address how power relations influence the theory and practice of KMb (Crosschild et al. 2021; Grenier et al. 2021; Kelly et al. 2021). Taken-for-granted assumptions about the ease of ‘knowledge exchange’ pay little attention to the politics of knowledge and power, and how intersecting social structures influence KMb processes. As academic researchers increasingly engage in collaborative research with non-academic partners, KMb theory and practice need to account for social inequities and question whose (as well as what) knowledge and experiences are being mobilised and how. These questions are particularly important in relation to youth research given the complex social relations around youth in society and the important potential of KMb in making a difference in youth’s lives and life paths.

This article therefore begins with the premise that YKMb presents specific research scenarios for which existing KMb theories (developed in adult research contexts) cannot fully account. We posit YKMb as a unique form of KMb for two reasons. First, YKMb often involves more actors because of the social locations of young people embedded within and supported by structures such as families, schools and communities. These locations make it harder for academic researchers to access youth and youth knowledge independently. Youth are either not fully autonomous, or not thought to be autonomous, and are therefore often represented by adults. Certainly, many youth are active and mobilised in their communities yet academic researchers located within institutions tend to be removed from youth and their communities. Academic researchers thus often seek collaborations with non-academic partner organisations (for example, schools and community organisations) that act as gatekeepers, mediators or intermediaries. Second, YKMb involves complex power dynamics because young people are often constructed as less powerful and autonomous in society and therefore not expected or asked to have valuable knowledge.

For these reasons, producing and mobilising youth knowledge can take multiple forms, each presenting specific challenges and opportunities. Here, one significant distinction pertains to the extent to which young people are involved. Academic researchers doing youth research may or may not directly engage young people in knowledge production or mobilisation. Many researchers advocate for participatory approaches with, by and for youth to integrate or amplify youth as knowledge producers or youth as researchers. However, adult researchers based in academic institutions (and at times partner organisations led by adults) often lead the majority of youth research with limited input from young people. Therefore, there is significant diversity in YKMb theory and practice due to the potential involvement of many actors, including academic researchers from different disciplines, multiple partner organisations, various adults in youth’s lives and differently positioned youth. Examining the tensions across these working relationships offers opportunities towards developing more critical accounts of KMb in the context of youth research. While many excellent case studies showcase, for example, participatory approaches to involving youth in YKMb, these approaches tend to be fragmented or niche areas within youth research. Much YKMb remains limited to what academic researchers do (after knowledge production) and therefore not necessarily explicitly named or theorised as a process with important implications for youth research. An overarching discussion across the diverse approaches to YKMb is missing from the literature. These gaps leave opportunities to unpack the theory and practice of YKMb and questions about how to advance YKMb as a specific form of KMb. In the absence of a paradigm for this work, much can be learned about YKMb by reflecting critically and collectively on how different academic researchers view and practice YKMb in different research contexts. This article explores academic researcher perspectives on the concepts, factors and mechanisms that influence diverse approaches to YKMb to map out an emergent integrative framework for YKMb.

To proceed, we first present an overview of the KMb literature to ground our analysis within existing theorical understandings. This review highlights some useful concepts for framing KMb in youth contexts, as well as the limits of existing models for understanding YKMb. We then describe the context for these questions – a collaborative research Chair on YKMb – and methodology for reflecting collectively on YKMb through the work of the Chair. The findings present an emergent YKMb framework as a work-in-progress to advance discussion about the theory and practice of YKMb.

Existing knowledge mobilisation frameworks

As the field of KMb evolves amidst a range of concepts and terminology, KMb models increasingly attempt to account for complexity within KMb processes. Earlier models emerging predominantly from business and management environments conceptualise mechanisms like conduits (Boland & Tenkasi 1995), stickiness (Szulanski 1996), and spirals (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995) to describe how knowledge is shared and integrated into practice. These models tend to focus on different mechanisms and outcomes within KMb processes with the aim of improving productivity and innovation (Jull et al. 2017). Other collaboration and partnership models of KMb have different historical roots focusing on ethical questions and concerns about power relations within research with the aim of addressing social justice concerns (Jull et al. 2017; Nguyen et al. 2020). Clearly, different values and objectives inform various approaches to KMb.

Three features of KMb offer conceptual tools for understanding the diversity of approaches to YKMb. First, knowledge production and mobilisation can be separate processes or they can be intertwined. As Crosschild et al. (2021) noted, many traditional scientific research scenarios first produce knowledge and then mobilise it later. For example, academic researchers commonly produce articles, books or other outputs (for example, reports, infographics, videos or podcasts) to mobilise knowledge at the end of funded research projects. In other research scenarios, the production and mobilisation of knowledge may occur simultaneously, after which knowledge may also then continue to be mobilised with different knowledge users. For example, participatory traditions involve community members in data collection and analysis, such that the research knowledge is mobilised through the co-production process. Then, communities may also decide to hold a forum with other knowledge users (like local leaders) to share what was learned through the research. Second, some types of knowledge may be more readily shared and exchanged compared to others. For example, technical knowledge in the sciences may be easier to share compared to knowledge in sectors such as health, social services and education (Graham et al. 2006), and explicit knowledge may be more readily shared than implicit forms of knowledge (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995). Third, different relationships exist between knowledge producers and knowledge users. For example, Lavis et al. (2006) identified various models of KMb including: (1) push, where academic researchers or intermediaries reach out to community or institutional partners likely to use scientific knowledge; (2) pull, where partners ask researchers to listen to their needs and produce knowledge adapted to their questions and realities; and (3) exchange, where projects are co-developed and co-produced by both researchers and partners. Some KMb models now distinguish academic researcher roles within KMb processes, from producing knowledge to brokering research relationships and fostering networks, to advocating evidence, researching practice and advancing the field of KMb itself (Davies, Powell & Nutley 2015; Haynes et al. 2020). The field is becoming increasingly more complex and self-critical in refining the elements, mechanisms and impacts of KMb.

However, existing KMb models typically assume that partners are adults with the rights and privileges of adults, certain levels of education and training and experience working within organisational or institutional environments. Many questions remain about the theory and practice of YKMb and how the specificities, challenges and opportunities of youth engagement shape YKMb. While KMb may incorporate collaboration with partner organisations, the possible involvement of young people adds layers of complexity. These questions are particularly critical when accounting for the realities of diverse, marginalised or differently positioned youth. Social inequities affect which youth are more supported and heard within research. Integrating diverse young people across intersecting power structures that include, for example, colonialism, racism, patriarchy and transphobia requires awareness of the specific challenges to meaningful youth engagement. Many empirical studies document the facilitators and barriers involving young people in KMb, for example, through youth advisory councils (Canas et al. 2019; Chan et al. 2021; Halsall, McCann & Armstrong 2022), popular theatre approaches to working with Indigenous youth (Plazas et al. 2019) and involving racialised youth in community-university action research project (Mosher et al. 2014), although this literature does not use the term YKMb. Limited scholarship integrates and advances the theory and practice of YKMb across these diverse approaches and actors. There are meaningful opportunities to explore – within the same frame – how and why researchers engage in YKMb in the ways that they do.

To interrogate this gap, we launched MYRIAGONE, the McConnell-University of Montreal Chair in Youth Knowledge Mobilization. The Chair is held by five co-chairs working together across three disciplines and numerous partner organisations. The Chair holders each conduct different types of youth research (from quantitative to qualitative and action-oriented) with various groups and communities in Quebec, Canada (including urban, rural, and Indigenous contexts). To understand the realities and circumstance of young people, we work with an interdisciplinary approach at the intersections of health, education and work. We are particularly concerned with reaching, understanding and addressing the realities of youth in situations of social inequity. As part of the intellectual work of the Chair, we bring our diverse field experiences alongside theories of KMb to think through the specificities and complexities of YKMb in theory and in practice.

Methods

To explore the diversity of YKMb practices within our Chair, we developed an iterative inquiry process involving qualitative, reflexive and conceptual approaches over several years and phases. Early in this process, it became apparent that many YKMb practices were implicit in our work. Reflexivity offers an approach for researchers to acknowledge their role in the research and to reflect critically on how their subjectivity influences the research process, in particular, for attending to issues related to power relations (Sultana 2007). Therefore, our methodology aimed to first identify and explicitly name how the five researchers in the Chair work differently to produce and mobilise youth knowledge and then, second, develop an integrative framework for thinking across our diverse approaches. The work proceeded in three phases, as outlined below.

Phase I: Identifying different approaches to youth research

First, individual semi-structured interviews conducted by the first author (who was at the time, a postdoctoral researcher with the Chair) explored each Co-chair’s disciplinary background, conceptual and theoretical interests and methodological approaches to youth research. In this phase, each of the Co-chairs reviewed the transcript from their own interview and identified important insights, which were shared and discussed in a focus group session.

Phase II: Identifying different approaches to YKMb

This phase allowed us to identify some key actors within YKMb processes, and the range of contextual factors that influence YKMb. For this phase, we adapted Lavis et al.’s (2003) questions to identify: What knowledge should be mobilised? To whom should knowledge be mobilised? By whom should knowledge be mobilised? How should knowledge be mobilised? With what effect should knowledge be mobilised? We also added the question: Who should produce the knowledge to be mobilised? We explored YKMb as a group in a facilitated workshop as well as through a second individual semi-structured interview with each Co-chair.

Phase III: Integrating a diversity of practices

This phase aimed to account for the diversity of practices, approaches and concerns described across the work of the Chair. Inspired by continuum models of diversity, for example, Careau et al.’s (2015) framework for interprofessional collaboration, we developed a series of working continuums that consider the range of diverse approaches to YKMb within the Chair. Workshopping these continuums provided an inclusive co-analytical process that allowed for flexibility and fluidity so that researchers could identify their practices along multiple continuums, while also recognising that practices are not static and shift along continuums. These continuums – and the emergent framework below – remain purposefully tentative. This process allowed us to identify and structure the key themes and questions that we see shaping YKMb theory and practice. While we draw on our field experiences to theorise YKMb practice, we do not elaborate on individual projects in this article. We invite readers to visit our website to learn more about our work (www.myriagone.ca).

Results

YKMb is as multifaceted as youth research itself; it takes many forms that necessitate different strategies. To account for the different approaches to YKMb, it might be initially tempting to attribute this diversity to disciplinary differences. While disciplinary traditions certainly play a role, our findings suggest that discipline alone cannot account for the different ways that academic researchers think about and practise YKMb. YKMb can also vary quite considerably among academic researchers located in the same discipline because of how YKMb changes from project to project as well as from context to context. Many researchers use different approaches to YKMb, depending on the project. As we elaborate below, several other factors also come into play, which we organise in two major sections. We first present an overview of the factors influencing YKMb within an emergent framework and how these factors interact. We then zoom in on one aspect of YKMb highlighted through our focus on academic researcher perspectives: the circumstances that influence the roles that academic researchers might want or need to play in YKMb.

Part I: Mobilising knowledge about, for, with and by youth

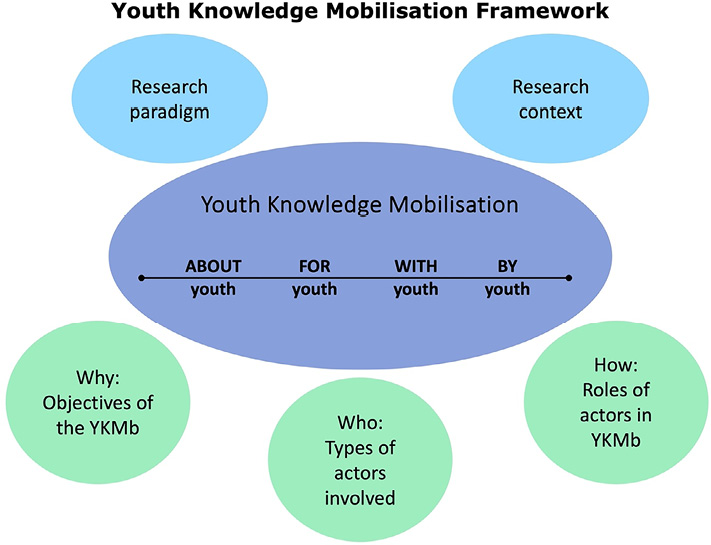

Figure 1 presents an emergent framework that integrates some key factors influencing YKMb in theory and in practice. To a certain extent, the spiral (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995) or stickiness (Szulanski 1996) models of KMb form the basis of this framework. These mechanisms portray iterative and non-linear processes that encourage different actors (for example, researchers, partner organisations or young people) to spend time together and exchange explicit and tacit knowledge in different ways and spaces. This is far more complicated than it seems. We identify several inter-related factors that differentiate why academic researchers might employ different YKMb strategies in different research scenarios.

Figure 1. An emergent YKMb framework

In the centre, anchoring the framework, a continuum of YKMb practices includes YKMb about youth, for youth, with youth and by youth. Each of these working relationships offers a different mode of youth involvement within YKMb, and each with different epistemological and methodological implications. While we focus on YKMb, these modes of working may also refer to youth involvement in research (as noted earlier, knowledge production and knowledge mobilisation may occur separately or be intertwined). Each mode considers youth differently. YKMb about youth considers young people as the object or context of the research, accounting for most youth research that tends to be conducted and mobilised by adult researchers. This mode could include, for example, theoretical work advancing academic conversations about conceptions of youth or longitudinal statistical analysis to study the transitions in young people’s lives across generations. Moving along the continuum, YKMb for youth positions young people as beneficiaries, users or receivers of knowledge. For example, YKMb for youth could include research about teaching and learning that informs school curricula and teaching practice or psycho-social research that informs social programs for youth. YKMb with youth involves young people as consultants informing or guiding the research process, or as co-researchers, co-producers or co-mobilisers of knowledge alongside academic researchers. For example, participatory visual research inviting youth to produce images to identify, represent and co-analyse issues in their lives helps to shift the narrative towards youth-centred ways of seeing. In YKMb by youth, youth lead the research process as researchers, knowledge producers and mobilisers. For example, youth-led organisations may plan, execute and mobilise research that invites academic researcher input, but youth lead the research decisions and process. These four modes of YKMb are neither static bounded categories nor are they mutually exclusive. Many projects employ different approaches across different stages of implementation.

Around this central continuum, several inter-related factors in turn shape YKMb. These factors include research paradigm and context (two spheres at the top of Figure 1) as well as which actors participate, the roles different actors play and the reasons driving different actors to participate in YKMb (three spheres at the bottom of Figure 1). Each of these factors includes a range of possibilities. Given the interdependence of these factors and the spiral dynamic that animates the framework, it is difficult to describe each factor individually or sequentially. To describe this interplay, we first introduce how research paradigm influences YKMb. We then demonstrate how other factors related to the research context intersect with paradigm to influence and complicate the who, what and why of YKMb. In broad strokes, the more researchers seek the input and involvement of different types of actors, the more complex scenarios are encountered, and the more researchers need to consider what is needed for YKMb to be meaningful and relevant for those involved.

How research paradigm influences YKMb

Paradigm refers to ‘the basic set of beliefs that guides action’ (Guba 1990, p. 17). Research paradigm plays a significant role underpinning the construction of youth within research from a range of, for example, developmental, socially constructed, historically situated and structural perspectives. Paradigmatic differences in epistemologies, ontologies and methodologies influence how youth knowledge is produced and mobilised including disciplinary traditions as well as the assumptions, values and beliefs that shape research decisions and the criteria for good quality research. Guba and Lincoln (2005) distinguish five key research paradigms – positivism, postpositivism, critical theory, constructivism and participatory – and additional bodies of scholarship also include, for example, pragmatic and transformative paradigms (Creswell & Poth 2016) as well as Indigenous paradigms (Held 2019). We do not attempt to prescriptively map out the specificities of these and various other paradigms. We simply highlight how differences related to paradigmatic expectations affect what strategies researchers use for YKMb as well as the place of youth agency and voice in these processes. For example, in theory, paradigms that require an objective distance between researcher and youth knowledge (such as positivism and post-positivism) may align with YKMb about youth. Here, traditional scientific methods aim to describe a generalisable reality, where youth knowledge is seen as external from the researcher and validated through procedures that protect objectivity. Researchers’ values, subjectivity and positionality – as well as those of partner organisations and young people – may constitute forms of bias that need to be excluded from knowledge to anchor research validity. On the other hand, paradigms that seek the co-production and mobilisation of knowledge (such as participatory or transformative paradigms) may align more fundamentally with YKMb with and by youth. These paradigms produce situated, shared and more diffuse forms of lived, embodied and sensory knowledges, and aim to address more explicitly the power dynamics between academic researchers and young people. The credibility of these knowledges depends on the quality of youth engagement.

In practice, paradigms are far from discrete or essentialised systems and often co-exist in complex, overlapping and contested ways (Guba & Lincoln 2005). It may be unconstructive and even problematic to attempt to ascribe individual researchers or projects to certain paradigms. On the contrary, different paradigms often co-exist and serve different purposes at different stages of the research process. Many researchers combine multiple paradigms and modes of working. Here it might be helpful to envision paradigm diversity as a set of nested continuums that depict some of the key tensions across paradigms, for example, on the role of objectivity or subjectivity, or on the inclusion or exclusion of personal values in research (see Guba & Lincoln 2005; Held 2019). Essentially, paradigm influences the types of relationships that researchers have with knowledge production and therefore how YKMb is conceptualised and negotiated. Research paradigm offers an integrative frame for dialogue across the diversity of approaches that researchers employ to produce and mobilise youth knowledge.

How research context influences YKMb

Alongside paradigm, we also found that YKMb practices vary from project to project and from context to context. The factors impacting this variability include social, economic, political, cultural, linguistic and geographic specificities of different research contexts. The scope of research questions also influences the scale or unit of analysis, and the methodologies needed to meet the specific needs of particular projects and youth contexts. For example, youth research in collaboration with more formal organisational partners like schools or national statistical agencies often requires more institutionalised approaches to YKMb, such as producing accessible reports and sharing them on websites, organising meetings with school boards or communicating findings through professional channels. Youth research drawing on more informal or community-based spaces like homes, streets or parks often requires for informal or community-based YKMb strategies that include, for example, visual products like pamphlets or posters, or through publicly accessible channels like radio or social media. Each research project arguably has a unique set of contextual factors. Conceivably, innumerable contextual factors influence the landscape of what YKMb looks like in practice. Together, research paradigm and context influence how researchers imagine, create and negotiate YKMb in practice. This leads to the third major factor regarding the who, what and how engaging different types of actors in YKMb.

How the involvement of diverse actors influences YKMb

Which actors participate in YKMb, the roles they play, and why they want to participate (their expected outcomes) also interact to create a range of research scenarios that require different YKMb strategies. As noted, these actors may include academics from different fields and disciplines, as well as partner organisations with different types of mandates, and young people with various backgrounds and lived experiences. Identifying who has power to take up the knowledge produced and make change helps to develop YKMb plans that include specific actors that need to be reached for the desired outcome of the KMb process. These actors also become key knowledge producers within the YKMb process and not just recipients or users of the knowledge. Research for, with and by youth requires the involvement of more actors, each with different interests and realities. Different actors often have different mandates that influence their relationships with young people, who needs to participate in YKMb and how researchers need to plan to facilitate these exchanges. Youth from different backgrounds or environments may have different interests in topics or motivations for being involved and have varying access to opportunities and mobilisation processes. For example, an interactive exhibition inviting adolescent participants and their family members to a university campus to mobilise youth-produced artwork requires a very different set of YKMb strategies compared to a media campaign mobilising research findings about the health and safety of young farmers from rural communities. Partners may have different organisational objectives, structures and capacities as well as priorities related to stakeholders and beneficiaries, internal needs or expectations. For example, organisations that want to improve service provision by supporting practitioners requires different YKMb strategies compared to organisations working to address power imbalances in their governance structures by engaging youth in decision-making. Certainly, diverse organisations have different starting points, which can create gaps in terms of language, benchmarks and resources required to participate in the YKMb. Negotiating these collaborations may be one of the ways that YKMb can effectively address the power dynamics inherent within youth research. Indeed, finding effective ways to engage diverse actors makes YKMb unique and challenging.

Part 2: A spotlight on researcher roles in YKMb

Given academic researcher responsibilities and mandates for mobilising research knowledge, it is not surprising that how researchers see and negotiate their role in YKMb influences their YKMb practices. These roles reflect academic researcher motivations to do YKMb. The reasons why researchers may engage in YKMb – the types of outcomes they want to achieve – affects how they approach YKMb and involve other actors, and who is involved or excluded from the process. Academic researchers engaging in YKMb to meet funder requirements or research-focused impacts may prioritise academic publications and academic conferences (YKMb about youth). Academic researchers and partners who want to change policy need to engage with leaders and policymakers, perhaps through more formal, public-facing strategies like public round-table discussion events (YKMb for youth). Other academic researchers interested in how YKMb may improve social support for youth through, for example, improved outreach or services may need to mobilise practitioners (for example, teachers, youth workers, healthcare providers) through engaged YKMb strategies such as infographics or video capsules easily shared on social media to provide accessible ways to engage busy practitioners. To improve youth access to structures, services and institutions, academic researchers may need to dedicate time participating and advocating in organisational committees or boards where decision-making takes place (also YKMb for youth). Researchers who want to empower or support youth leadership need to involve youth directly in the research and mobilisation processes and create dedicated space to amplify youth voices (YKMb with and by youth). Academic researchers may also value reciprocity and want to give back to partner organisations or change how they work to disrupt dominant norms within the academy. Most researchers are likely motivated by several goals including broader societal-level ones such as addressing social inequities, creating a more inclusive society and decolonising research. Academic researchers mobilise knowledge for many reasons that each necessitate different strategies for involving non-academic actors.

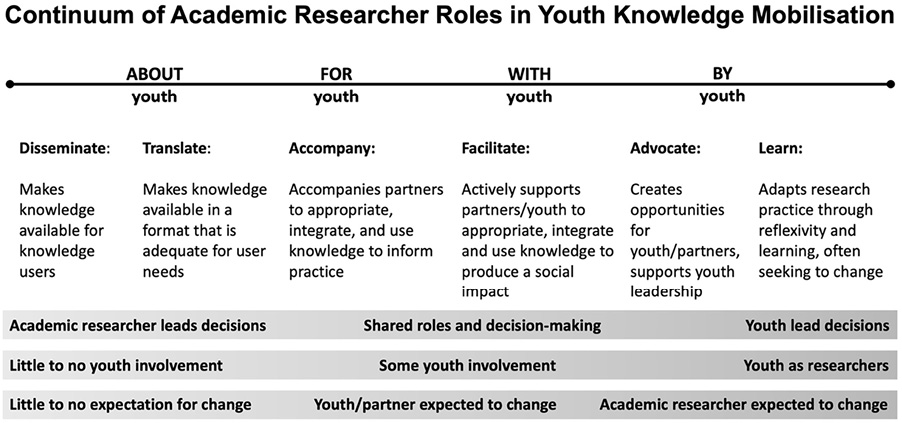

We suggest that academic researcher roles are also influenced – at least in part – by research paradigm, which ascribes specific roles that underpin criteria for what counts as good quality research (Guba & Lincoln 2005). Within some paradigms, academic researchers may view the responsibility to mobilise knowledge predominantly in their professional roles. Other paradigms may position researchers as advocates who mobilise knowledge all the time within their communities and personal lives. These roles are also shaped by how academic researchers adapt and adopt new roles to respond to partner needs or interests. For example, inviting adolescents with little exposure to academic milieus to participate in an academic panel requires more active researcher engagement so that youth feel comfortable and prepared in a new setting. In comparison, more traditional academic researcher roles involve preparing academic publications for scholarly journals. The continuum of researcher roles (Figure 2) begins to map out the diversity of roles that academic researchers may seek or expect to play in YKMb and approaches where young people are also involved as researchers. In general, these roles align with the about, for, with and by youth modes of working, as well as with paradigmatic expectations for change in the research process (bottom bar of Figure 2).

Figure 2. Continuum of academic researcher roles in YKMb

The two modes on the left of this continuum (about youth and for youth) may not directly involve young people. These modes probably account for large bodies of literature pertaining to young people over time. On the extreme left (YKMb about youth), academic researchers produce and disseminate research to make knowledge available through, for example, traditional academic outputs such as publications and conferences that tend to assume other researchers as the primary knowledge users. Academic researchers play a primary role in decision-making in these processes with little to no youth involvement or anticipated change in how researchers produce and mobilise knowledge. Moving toward the right, research becomes more like an intervention with anticipated action or change. YKMb for youth expects that the research may benefit youth directly or indirectly through partner organisation activities. For example, research may respond to partner concerns and be translated into a format accessible to diverse knowledge users (for example, reports, infographics, podcasts). Academic researchers may also accompany partners (including youth) to actively facilitate discussions about how to integrate or use knowledge to influence or adapt practice, with some expectation that change may occur.

The two modes to the right of the continuum (with youth and by youth) must directly involve young people. These modes probably account for smaller bodies of scholarship overall but are becoming increasingly common with paradigm shifts around youth participation. Moving towards the right (YKMb with youth), academic researchers advocate and create opportunities and support for youth or partner initiatives. This includes including young people at various stages of the research processes, from research design and identifying research questions, to data collection and analysis, and dissemination or mobilisation. In YKMb led by youth, researchers listen and witness, and adapt their research practice through reflexivity and learning, often seeking to change themselves and how they do research. Moving towards the right along this continuum, personal relationships become more important; academic researchers, partners and youth must invest more time building and maintaining these relationships. The higher the level of involvement and longer duration of the relationship with youth and partners, the more time and effort are required and the more YKMb practice requires personal investment from everyone involved.

This continuum of researcher roles is not linear or exhaustive. In practice, researcher roles and interests change depending on the project and situation. Returning to the YKMb framework presented in Figure 1, YKMb involves several differently positioned actors (for example, researchers, partners organisations, young people themselves) working together over time in different modes: about youth, for youth, with youth and by youth. These modes are influenced by research paradigm and context as well as by who, how and why of how non-academic actors are involved. Each mode requires different strategies and approaches to communicate across differences by finding ways to build common languages. These multiple layers interact such that YKMb practices are dynamic, cumulative, responsive and transformative. When researchers work together in interdisciplinary and intersectoral contexts, they learn from each other and from other actors therefore can be inspired to work differently. YKMb occurs across multiple projects over time and across researchers’ careers. What happens in one project – the people involved, the processes developed, the knowledge produced, how knowledge users integrate this knowledge – become building blocks and pathways for future YKMb.

Discussion

YKMb offers a critical avenue for building more inclusive and equitable societies. Global changes regarding the rights of young people have radically changed the landscape of youth participation in research (Graham, Powell & Taylor 2015; United Nations 1989). The increasing involvement of young people and youth-focused organisations in research, alongside the increasing expectation or requirement for academic researchers to both do interdisciplinary research and find ways to put the research into use, raises many questions and sometimes tensions about strategies for YKMb. Our findings build on some core components of existing KMb theories (from knowledge translation to co-production) and contribute new insights to the specificities of YKMb by identifying several layers of complexity and the concept of continuums as a strategy for working across diverse approaches. Many factors influence researcher decisions about how to develop YKMb activities: the research focus, the perception of the roles that academic researchers should (or should not) play in the public sphere, the ability to share decision-making power, the perceived responsibility for carrying out changes in practice settings and which youth ultimately participate and are heard within research. These complexities help to name what makes YKMb so challenging. We now discuss four challenges to YKMb.

First, existing KMb models imply that mobilising knowledge requires space and time to share experiential and tacit knowledge (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995). These models assume that people come together over time and build common language and understandings through rational ‘common sense’ processes (Crosschild et al. 2021). Our work suggests that the who and how of bringing diverse actors together is much more complex and power-laden, especially in youth contexts which involve many more structures and possible actors, each with different powers and expectations. The challenge is that there are zones of ‘no meet’ with impossibilities of actors spending time together. Many academic researchers have little to no contact with youth, whereas youth may be in contact with an organisation or other researchers. These relations make it essential for academic researchers to collaborate across disciplines, as well as with partners and with youth, to share knowledge. YKMb therefore involves not one knowledge spiral but several spirals that do not necessarily overlap or have the same powers. By doing intersectoral and interdisciplinary work, actors can more effectively mobilise knowledge across spirals.

Second, the institutional environments where academic researchers work shape what roles they are encouraged and supported to play in YKMb. It is well documented that universities prioritise peer-review publications in high-impact journals, which may inadvertently prioritise less time to intensive YKMb approaches. For example, YKMb about youth does not require as much of a time commitment as YKMb for and with youth where academic researchers facilitate and support relationships with partner organisations and young people. Working with youth involves building relationships and trust. Researchers need to spend dedicated time with young people to understand what interests and motivates youth to participate. Furthermore, academic researchers’ institutionalised locations – in quite different spaces from where youth spend their time – affect researcher capacities to reach marginalised youth, further shaping which youth tend to participate in research. Academic institutions also mandate their researchers with multiple competing responsibilities such as teaching and service. The resources and infrastructures needed to support direct youth engagement work are often not recognised within university structures or funding agency criteria.

Third, our findings highlight tensions in whether academic researchers can or want to work directly with youth. The time commitments and trust-building involved in working with youth complicates YKMb because academic researchers and youth may not always be available at the same times; youth have school and other responsibilities when academic researchers are available during a typical work week, and academic researchers’ personal and family responsibilities often conflict with youth’s availabilities on nights and weekends. It can be challenging to maintain ongoing contact as youth transition from secondary school to the workforce and across different levels of tertiary education or starting of families. For many reasons, not all academic researchers are available, interested or well-suited to youth engagement. Partner organisations often have existing networks and relationships with youth and their communities as well as existing in-house skills, resources and experience that are better equipped and positioned for direct youth engagement. Academic researchers may opt to collaborate with partner organisations as a more sustainable and effective approach to YKMb.

Fourth, the diversity of approaches to YKMb certainly does not occur in isolation but alongside and informed by KMb in other research contexts. While funders and institutions now often mandate KMb (for example, in the Canadian context), academic researchers often lack the practical and conceptual tools for developing KMb strategies and plans in general (Phipps et al. 2016). Existing models do not provide many concrete or reflexive tools for how to do KMb in different contexts. As a result, KMb involves individualised and sometimes ad hoc approaches (Ward et al. 2010). These personalised elements rely on taken-for-granted assumptions, which tend to render underlying structural realities and inequalities invisible. Making researcher beliefs and expectations more explicit is helpful for unpacking the theory and practice of YKMb and for developing more intentional and transparent approaches to YKMb. Coming back to critical questions about power in YKMb, fostering conversations that explicitly name expectations and objectives around YKMb can help research teams and partnerships think through who ends up being included and excluded from research processes, whose knowledge is being mobilised and why. Supporting this strategic thinking can support the design of appropriate steps to reach particular audiences, within the realities of research timelines and budgets in ways that acknowledge the power dynamics and social inequalities at play. This emergent framework suggests that YKMb needs to remain both strategic and responsive, including planned elements as well as space for spontaneous and informed interventions that work with the momentum of evolving research scenarios.

Conclusion

Amidst global concerns about research impact are questions about how research can better contribute to policy, practice and social change. While this work is always situated – often called different things in different places and disciplines – the concept of KMb offers an umbrella term that can unite core concerns about what is needed to put research into use. While the term itself has particular significance in the Canadian context, we believe the underlying ideas presented in this article offer relevant insights for researchers working with other frameworks such as knowledge transfer, knowledge democracy, engaged scholarship, participatory research and others. In the absence of a unifying body of YKMb literature, this article draws on our research experiences as an interdisciplinary Chair to offer an emergent integrative YKMb framework based on academic researcher perspectives. We suggest that YKMb is distinct from other forms of KMb because of the realities and power dynamics of young people’s lives and positions in society. Given the need for the involvement of more actors, YKMb is a complex multifaceted process that can take many different shapes, influenced in part by academic researcher assumptions and social positions, as well as by the context and needs of partner organisations and youth. Many of these factors remain implicit in practice.

Our findings demonstrate practical and theoretical implications for community-engaged scholarship about, with, for and by youth, as well as for researchers working with more traditional approaches who also want to mobilise their findings. Our findings offer conceptual tools and language for naming some of the realities and factors that influence YKMb to spur more explicit and critical interrogations within this field. In particular, when we have presented these findings with our research partners (including government, funding and non-profit organisations), the idea that there are continuums of practice has resonated the most clearly for acknowledging and articulating tensions in their work and in recognising the importance and value of different approaches to YKMb.

We conclude by emphasising the possibilities of continuums of practice in YKMb and suggest the possibilities of more community-engaged work to co-develop continuums with diverse groups of knowledge producers and users. To advance the theory and practice of YKMb, further research is needed to incorporate the perspectives of different communities of knowledge users and producers, including partner organisations, policy actors and young people themselves. We hope that inviting more critical discussions around the diversity of approaches to YKMb in theory and practice, and how continuums can support interdisciplinary and intersectoral teams, will help to make a difference in the lives of the young people who inspire this work.

Acknowledgements

Many collaborative projects have helped shape our work as the MYRIAGONE Chair. To begin, we would like to extend an important thank you to the many young people who have participated in our various research projects over the years for guiding us in this work and for letting us know what has worked and what has not worked. We thank our partner organisations for their generosity and interest in engaging in collaborative research, and for committing to processes that constantly evolve and often take longer than planned. We would also like to thank Mathieu-Joël Gervais for theoretical insights about the field of knowledge mobilisation and for accompanying us in reflecting collaboratively on our youth knowledge mobilisation practices, a process which has been far from straightforward. His suggestion to develop continuums was foundational in enabling us to think across our diverse practices in an inclusive way.

Authors’ contributions

Jennifer Thompson played a lead role in facilitating the collaborative research process and article development.

Sarah Fraser and Véronique Dupéré played lead roles in conceptualising the research design and findings, and article development.

Sarah Fraser, Véronique Dupéré, Nancy Beauregard, Isabelle Archambault and Katherine Frohlich participated in the collaborative analysis process and in article development and revisions.

Josée Lapalme participated in conceptual development of the findings and article revisions.

References

Barwick, M, Dubrowski, R & Petricca, K 2020, Knowledge translation: The rise of implementation, American Institutes for Research. https://ktdrr.org/products/kt-implementation/KT-Implementation-508.pdf

Boland, RJ & Tenkasi, RV 1995, ‘Perspective making and perspective taking in communities of knowing’, Organization Science, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 337–507. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.4.350

Canas, E, Lachance, L, Phipps, D & Che Birchwood, C 2019, ‘What makes for effective, sustainable youth engagement in knowledge mobilization? A perspective for health services’, Health Expectations, vol. 22, pp. 874-82. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12918

Careau, E, Brière, N, Houle, N, Dumont, S, Vincent, C & Swaine, B 2015, ‘Interprofessional collaboration: Development of a tool to enhance knowledge translation’, Disability and Rehabilitation, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 372–78. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.918193

Chan, M, Scott, SD, Campbell, A, Elliott, SA, Brooks, H & Hartling, L 2021, ‘Research- and health-related youth advisory groups in Canada: An environmental scan with stakeholder interviews’, Health Expectations, vol. 24, pp. 1763–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13316

Creswell, J & Poth, C 2016, Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches, Sage Publications, Los Angeles.

Crosschild, C, Huynh, N, De Sousa, I, Bawafaa, E & Brown, H 2021, ‘Where is critical analysis of power and positionality in knowledge translation?’, Health Research Policy and Systems, vol. 19, no. 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00726-w

Davies, H, Powell, AE & Nutley, SM 2015, ‘Mobilising knowledge to improve UK health care: Learning from other countries and other sectors – a multimethod mapping study’, Health and Social Care Delivery Research, vol. 3, no. 21. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr03270

Golhasany, H & Harvey, B 2023, ‘Capacity development for knowledge mobilization: A scoping review of the concepts and practices,’ Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, vol. 10, no. 235. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01733-8

Graham, A, Powell, MA & Taylor, N 2015, ‘Ethical research involving children: Encouraging reflexive engagement in research with children and young people’, Children and Society, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 331–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12089

Graham, I, Logan, J, Harrison, M, Straus, S, Tetroe, J, Caswell, W & Robinson, N 2006, ‘Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map?’, Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.47

Grenier, A, Gontcharov, I, Kobayashi, K & Burke, E 2021, ‘Critical knowledge mobilization: Directions for social gerontology’, Canadian Journal on Aging, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 344–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980820000264

Guba, EG 1990, ‘The Alternative Paradigm Dialog’, in EG Guba (ed), The Paradigm Dialog, Sage Publications, Los Angeles, pp. 17–27.

Guba, EG & Lincoln, YS 2005, ‘Paradigmatic Controversies, Contradictions, and Emerging Confluences’, in N Denzin & Y Lincoln (eds), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd edn, Sage Publications, Los Angeles, pp. 193–215.

Halsall, T, McCann, E & Armstrong, J 2022, ‘Engaging young people within a collaborative knowledge mobilization network: Development and evaluation’, Health Expectations, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 617–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13409

Haynes, A, Rychetnik, L, Finegood, D, Irving, M, Freebairn, L & Hawe, P 2020, ‘Applying systems thinking to knowledge mobilisation in public health’, Health Research Policy and Systems, vol. 18, no. 134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00600-1

Held, M 2019, ‘Decolonizing research paradigms in the context of settler colonialism: An unsettling, mutual, and collaborative effort’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 18, pp. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918821574

Jull, J, Giles, A & Graham, ID 2017, ‘Community-based participatory research and integrated knowledge translation: Advancing the co-creation of knowledge’, Implementation Science, vol. 12, no. 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0696-3

Kelly, C, Kasperavicius, D, Duncan, D, Etherington, C, Giangregorio, L, Presseau, J, Sibley, KM & Straus, S 2021, ‘“Doing’ or ‘using’ intersectionality? Opportunities and challenges in incorporating intersectionality into knowledge translation theory and practice’, International Journal for Equity in Health, vol. 20, no. 187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01509-z

Lavis J, Robertson, D, Woodside, J, McLeod, C, Abelson, J 2003, ‘How can research organizations more effectively transfer knowledge to decision makers?’, The Milbank Quarterly, vol. 80, no. 2, pp. 221–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00052

Lavis, J, Lomas, J, Hamid, M & Sewankambo, NK 2006, ‘Assessing country-level efforts to link research to action’, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, vol. 84, no. 8, pp. 620–28. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2627430/pdf/16917649.pdf. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.06.030312

Mosher, J, Anucha, U, Appiah, H & Levesque, S 2014, ‘From research to action: Four theories and their implications for knowledge mobilization’, Scholarly Research Communication, vol. 5, no. 3. https://doi.org/10.22230/src.2014v5n3a161

Nonaka, I & Takeuchi, H 1995, The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation, Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195092691.001.0001

Nguyen, T, Graham, ID, Mrklas, KJ, Bowen, S, Cargo, M, Estabrooks, CA, Kothari, A, Lavis, J, Macauley, A C, MacLeod, M, Phipps, D, Ramsden, VR, Renfrew, MJ, Salsberg, J & Wallerstein, N 2020, ‘How does integrated knowledge translation (IKT) compare to other collaborative research approaches to generating and translating knowledge? Learning from experts in the field’, Health Research Policy and Systems, vol. 18, no. 35, pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-0539-6

Phipps, D, Cummings, J, Pepler, D, Craig, W & Cardinal, S 2016, ‘The co-produced pathway to impact describes knowledge mobilization processes’, Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 31–40. https://doi.org/10.54656/GOKH9495

Plazas, PC, Cameron, BL, Milford, K, Hunt, LR, Bourque-Bearskin, L & Salas, AS 2019, ‘Engaging Indigenous youth through popular theatre: Knowledge mobilization of Indigenous peoples’ perspectives on access to healthcare services’, Action Research, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 492–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750318789468

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada 2023, Guidelines for effective knowledge mobilization, viewed 25 June 2025. https://sshrc-crsh.canada.ca/en/funding/policies-regulations-and-guidelines/guidelines-effective-knowledge-mobilization.aspx

Sultana, F 2007, ‘Reflexivity, positionality and participatory ethics: Negotiating fieldwork dilemmas in international research’, ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 374–85. https://doi.org/10.14288/acme.v6i3.786.

Szulanski, G 1996, ‘Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm’, Strategic Management Journal, vol. 17, no. S2, pp. 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171105

United Nations, Convention on the Rights of the Child, November 20 1989. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child

Ward, V, Smith, S, Foy, R, House, A & Hamer, S 2010, ‘Planning for knowledge translation: A researcher’s guide’, Evidence & Policy, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 527–41. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426410X535882

Ziam, S, Lanoue, S, McSween-Cadieux, E, Gervais, M-J, Lane, J, Gaid, D, Choinard, LJ, Dagenais, C, Ridde, V, Jean, E, Fleury, FC, Hong, QN & Prigent, O 2024, ‘A scoping review of theories, models and frameworks used or proposed to evaluate knowledge mobilization strategies’, Health Research Policy and Systems, vol. 22, no. 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-023-01090-7