Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 18, No. 2

July 2025

PRACTICE-BASED ARTICLE

Building Bridges: A Collective Case Study of an Experiential Education Boundary Spanning Framework in Action

Rebekah Harriger1, Tyler Hough2, Katia Maxwell3, Dennis McCunney4,*,

Ben Trager5

1 Office of Career Services and Experiential Learning, Harrisburg University of Science and Technology, Pennsylvania, USA

2 Career Development Office, Rice University, Texas, USA

3 Quality Enhancement Plan, Athens State University, Alabama, USA

4 Center for Student Success & Dept. of Political Science, East Carolina University, North Carolina, USA

5 Center for Student Experience and Talent, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

Corresponding author: Dennis McCunney, mccunneyw@ecu.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v18i2.9357

Article History: Received 24/09/2024; Revised 21/05/2025; Accepted 26/05/2025; Published 07/2025

Abstract

In higher education, boundary spanners play a crucial role in translating information, knowledge and culture across diverse stakeholder groups. This reflective essay shares insights from experiential education (EE) leaders who, through the Society for Experiential Education (SEE) fellowship program, examined the complexities of boundary spanning in experiential learning. Our collective inquiry highlighted the pressing need for adaptable frameworks to help professionals navigate the dynamic challenges of their roles.

Drawing upon our lived experiences, we developed the Experiential Education Boundary Spanner Framework, which includes four main pillars: (1) translating principles of practice; (2) unlocking points of access; (3) balancing stakeholder needs; and (4) envisioning and invigorating experiential education. This framework aims to assist educators and practitioners in fostering meaningful partnerships and enhancing the integration of experiential learning into curricula. The essay will outline our literature review on boundary spanning, introduce the authors and their diverse experiences, and articulate the methodology employed in our collective inquiry. Ultimately, we aim to shed light on how boundary spanners can effectively respond to the evolving demands of education while enriching student learning experiences and community engagement.

Keywords

Experiential Education; Boundary Spanning; Case Study; Higher Education; High Impact Practices

Introduction

In today’s rapidly evolving educational landscape, effective experiential education (EE) is more essential than ever. As higher education professionals, our diverse institutional roles – from directing community engagement to teaching and leading career services – shape how we understand and implement EE. We recognise that strategies effective in urban universities may not translate seamlessly to smaller liberal arts colleges. This collective case study explores our roles as boundary spanners – individuals bridging students, faculty, industry partners and communities. Each of us brings distinct insights on integrating EE into our work while addressing workforce needs and community demands. Our collaboration surfaces the nuances of practice and invites broader dialogue. By embedding real-world projects, community engagement, and hands-on learning into programs, we aim to cultivate both technical expertise and professional readiness. This dual focus equips students to navigate careers while fostering social responsibility.

Boundary spanners often share key traits: a focus on systems thinking; prioritising connection over constraint; awareness of bias and perspective; empathetic listening to build trust; and a commitment to interdisciplinary, mission-aligned leadership. These attributes are vital in higher education where disciplinary silos can hinder student learning.

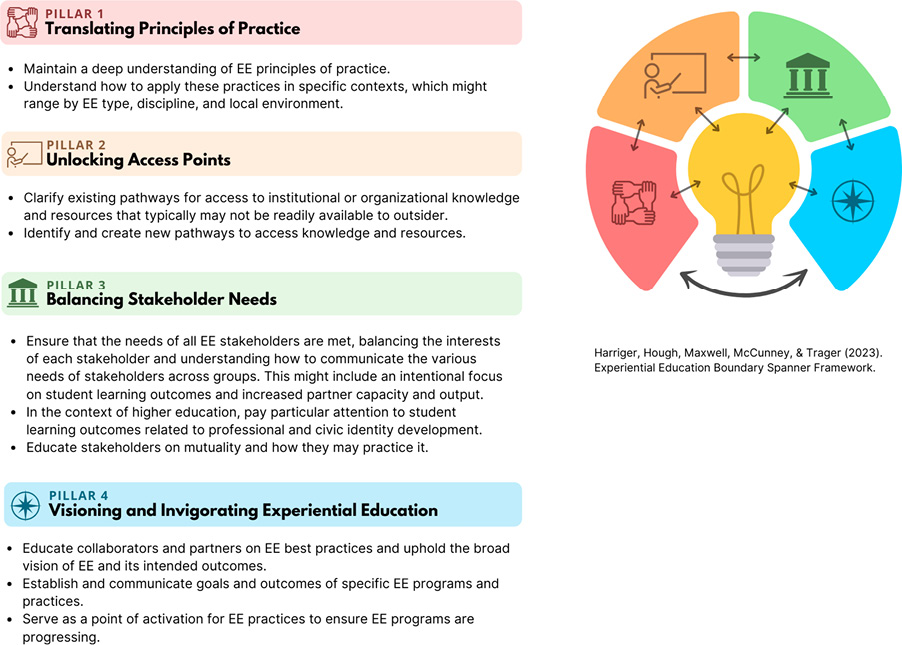

This article highlights the lived experiences of Society for Experiential Education (SEE) fellows who serve as boundary spanners. Through collaborative reflection and qualitative analysis, we present the Experiential Education Boundary Spanner Framework (Figure 1, below) – a guide for practitioners and scholar-practitioners in higher education.

Figure 1. Experiential education boundary spanner framework

Our narrative journey explores the challenges and successes of navigating stakeholder networks in EE. While existing literature defines boundary spanning in theory, our work responds to the need for applied frameworks that guide individual professionals. Drawing from diverse experiences, this framework offers a foundation for reflective practice across institutional contexts.

The following sections review relevant literature, introduce the authors, and describe the origins of our inquiry. We outline our methodology and present the framework’s four pillars: (1) translating principles of practice; (2) unlocking points of access; (3) balancing stakeholder needs; and (4) envisioning and invigorating experiential education. Through the lens of lived experience, we offer a grounded, practical perspective on boundary spanning. As we share our individual stories and collective insights, we underscore the essential role of boundary spanners in shaping EE practices that benefit both students and the communities they serve.

Boundary spanning in higher education

A robust body of literature addresses boundary spanning within higher education, offering a well-developed conceptual foundation. However, there remains a lack of specificity regarding its application across varied institutional contexts. While boundary spanning is relevant in many areas – including EE – few guiding frameworks exist to support these practices. This section synthesises key literature on boundary spanning in higher education as it informs the development of an EE boundary spanning framework.

The concept of boundary spanning in higher education is rooted in leadership theory. In response to increasing complexity and interconnection, scholars argue that executives must evolve from boundary-protecting managers to boundary-spanning leaders (Lee et al. 2014). While this transformation applies broadly, in higher education, faculty and staff often see themselves – by virtue of their roles – as the leaders charged with initiating this shift.

A 2009 white paper by Yip, Ernst and Campbell defines boundary spanning leadership, highlights a gap in capabilities, and issues a call to action. The authors identify five common types of boundaries relevant to higher education: (1) horizontal; (2) vertical; (3) stakeholder; (4) demographic; and (5) geographic. Horizontal boundaries exist across institutional functions; vertical boundaries reflect organisational hierarchies; and stakeholder boundaries arise between the university and its external community. This framework is particularly relevant for EE practitioners, who regularly collaborate across these dimensions with administrators, faculty, students, and community partners.

Some scholarly inquiries examine boundary spanning in higher education through the lens of collaboration and its outcomes. Andreasen (2023), for example, studied a school-university partnership in which school-based mentor teachers were co-employed on short-term contracts as faculty members. This model exemplifies boundary spanning in practice and demonstrates how collaboration between teacher practitioners and faculty can improve educational quality for early career teachers. Publicly Engaged Scholars: Next Generation Engagement and the Future of Higher Education (2023) similarly highlights a new generation of civically engaged scholars, introducing the concept of a boundary-spanning researcher identity. The book offers a paradigm for public engagement, shares personal narratives from individual scholars, and concludes by challenging readers to consider how public scholarship is reshaping higher education.

Sandmann et al. (2014, p. 84) examined how boundary-spanning community engagement practitioners ‘engage in unique behaviors that occur at the periphery of groups, organizations, and institutions’. In this same line of inquiry, Williams (2011) used a survey to identify, describe, and categorise boundary-spanning competencies and effective collaborative behaviour. Viewing boundary spanning through collaboration is both logical and necessary, as the practice is inherently partnership-based and designed to enhance educational outcomes through cross-boundary connection.

Another approach to boundary spanning in higher education occurs through the lens of learning. Roberts, Havemann and DeWaard (2023, p. 2) describe ‘learning designers’ who work ‘with educators to develop technologically supported and enhanced learning opportunities’. The authors discuss the role that learning designers have within third spaces, where ‘learning designers can therefore be a bridge between different domains of knowledge and ways of working, and can encourage design that respects the voices, ideas and perspectives of multiple learners in collaborative and interactive knowledge-building experiences’ (Roberts, Havemann & DeWaard 2023, p. 6). While the authors introduce a view of boundary spanning through the lens of a particular type of professional, they still do not document a model or framework that others may be able to follow.

Much of the existing literature on boundary spanning – both theoretical and applied – focuses on specific areas such as professional development, collaboration and learning enhancement. Building on this scholarship, an applied framework rooted in EE and informed by lived experience can meaningfully expand the field. In this reflective article, the authors propose a generalisable framework to help higher education practitioners understand the nuances of boundary spanning across diverse functional contexts within EE.

About the Authors

In 2023, the SEE’s fellows program convened a dozen EE scholars and practitioners, forming a community of higher education leaders committed to bridging practice and scholarship. Through strengthened connections, we discovered a shared link across our diverse campus contexts. Despite varying roles, we all embodied practitioner-scholar identities (Green 2023) and acted as boundary spanners (Hora & Millar 2011). This realisation opened the door to developing a broadly applicable framework to guide EE practice in higher education. In what follows, we share the experiences and pedagogies that shape our boundary-spanning perspectives. These brief author narratives demonstrate the range of contexts and roles in which boundary spanners inhabit.

BEN TRAGER: LEVERAGING COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS TO CHART A COLLABORATIVE FUTURE IN HIGHER EDUCATION

At the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, I lead community engagement and career services initiatives that equip students to graduate prepared for both professional success and civic responsibility. Situated within a new centre under enrollment management and student success, our work emphasises access, experiential learning and meaningful contribution. My background in urban education policy and workforce training informs a learner-centred approach that connects individual development with systemic change. Through partnerships with community organisations and industry, I ensure students gain real-world skills while advancing institutional goals. This dual focus transforms education into a collaborative force for social progress.

KATIA MAXWELL: CULTIVATING EXPERIENTIAL IMPACT FROM CODING CLASSROOMS TO CAMPUS-WIDE SUCCESS

As a computer science professor at Athens State University, I’ve always championed learning by doing. In my courses, students engage in sponsored projects, hands-on experiments and career-simulating case studies to build real-world technical and professional skills. This work led to my appointment as Director of the Experience | Success Quality Enhancement Plan, and most recently, Assistant Dean for the College of Arts and Sciences, where I now lead efforts to embed experiential learning across the curriculum and co-curricular programs. Whether students are building software, conducting research or analysing case studies, the goal is the same: preparing them for meaningful roles in the workforce.

REBEKAH HARRIGER: FUELING WORKFORCE READINESS BY BRIDGING STEM CAREERS AND EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING

At Harrisburg University of Science and Technology, I lead efforts to integrate career-oriented experiential learning into our STEM-focused curriculum. Using workforce data and industry collaboration, we align academic programs with evolving career demands. My background in career services and operations informs a strategy that connects student development with labor market needs. By embedding real-world experience throughout students’ education, we position them for career success while contributing to institutional and community impact. Our recent conference presentation introduced a boundary-spanning framework that invites collaboration and shared vision across sectors.

TYLER HOUGH: USING EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING TO POWER PARTNERSHIPS FOR GOOD

Throughout my career leading urban EE centres and now in my role at Rice Business, I’ve focused on building partnerships that advance both student success and social good. Experiential learning – rooted in Freire, Kolb and Dewey – has been central to this mission. At the Chicago Center and The Philadelphia Center, students engaged in immersive, place-based programs that developed leadership and critical consciousness. Now in Houston, I connect MBA students with industry partners to tackle societal challenges like climate change and equity. By translating knowledge into action, I help shape business as a tool for collective progress.

DENNIS MCCUNNEY: ADVANCING HOLISTIC STUDENT DEVELOPMENT WITH GLOBAL AND CIVIC VALUES

Inspired by Jesuit values of cura personalis and learning through contact, my work at East Carolina University centres on developing students as ethical, engaged leaders. As Director of Intercultural Affairs and Assistant Professor of Leadership Studies, I focus on democratic engagement, inclusive dialogue and community-based learning. With a background in urban education and civic engagement, I integrate service-learning, reflective practice and global perspectives into academic and co-curricular spaces. My goal is to equip students not only with knowledge but with the empathy and agency to create meaningful change in an interconnected world.

Methods

Our inquiry employed a qualitative interpretive lens and explored varying cases of similar phenomena – boundary spanning in the context of EE in higher education – to construct meaning. We drew on action research (Stringer 2007) and practitioner inquiry (Ravitch 2014) frameworks to support the goal of producing practical, actionable steps that could improve professional practice for those engaged in EE in higher education. The iterative, flexible process of action research (Merriam & Tisdell 2016) and drawing on experience as data through practitioner inquiry (Green 2023) lend themselves to integrating practice and knowledge generation, uniquely applicable to this line of boundary spanner inquiry.

To build a foundation of knowledge, we began by compiling EE support materials from our institutions, including mission statements, process documents, faculty course development templates and partnership guides. Each member reviewed these resources and engaged in open coding (Benaquisto 2008), identifying key concepts through line-by-line reading. We then shared observations, identified common themes, and discussed differences – conversations that generated further insight into boundary-spanning roles.

We grouped insights into categories, which one member distilled into overarching themes. The group reviewed and finalised these, resulting in four pillars described in the next section. We presented the framework at the 2023 SEE Conference, using attendee feedback to refine pillar characteristics and consider broader applications. During the review and writing process, we further clarified the subpoints within each pillar.

Findings

Figure 1 presents a flexible framework for practitioners and scholar-practitioners who serve as boundary spanners in higher education. Comprising four non-sequential, adaptable pillars, the framework allows users to engage with or move between pillars based on the demands of their specific context. The four pillars – (1) translating principles of practice; (2) unlocking points of access; (3) balancing stakeholder needs; and (4) envisioning and invigorating experiential education – offer guiding tenets grounded in the authors’ commitment to the transformative potential of EE. Rooted in lived experience, the framework provides a pragmatic, authentic lens for navigating the complexities of boundary spanning.

In the following sections, we detail each pillar, share examples of applied practice from our experiences, and describe moments when we’ve navigated the often messy, sometimes deeply fulfilling, and consistently complex realities of boundary-spanning work.

1. Translating principles of practice

In the framework, an individual boundary spanner operates from a deep understanding of how to translate EE principles of practice, as defined by SEE’s eight principles, into diverse contexts and with different stakeholders. Because EE varies across different types, disciplines and local environments, a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach does not work. Instead, boundary spanners must continually adapt and apply these principles to the unique challenges of each setting, frequently crossing the stakeholder, horizontal, vertical, geographic and demographic boundaries described by Yip, Ernst and Campbell (2009).

For example, a boundary-spanning faculty member and student affairs educator might partner with a community organisation to design a service project grounded in ‘preparedness and training’. From a student affairs perspective, this involves aligning goals and outcomes by connecting the organisation with faculty and students. Preparedness includes setting clear expectations for supervision, student roles and tracking hours – not only for students and faculty but also for the community partner. An orientation session helps establish communication and clarify responsibilities with follow-up meetings as needed. In the absence of a boundary-spanning student affairs educator, the faculty member must ensure that both students and the partner organisation are adequately prepared and informed. The boundary spanner’s collaborative behaviour (Williams 2011) is essential because it serves as a catalyst for EE activities and balances the needs of multiple stakeholders. The following sections illustrate this principle in practice.

PRACTICE IN ACTION EXAMPLE ONE: BRIDGING THEORY AND PRACTICE BY ACTIVATING SERVICE-LEARNING FOR SUSTAINABLE EDUCATIONAL CHANGE BY BEN TRAGER

In the spring of 2023, I developed a service-learning project with a faculty member in the architecture department and two partners from a STEM-focused K–12 organisation. The project engaged over 150 architecture students, working in groups of three at metropolitan schools. Each group spent 20 hours supporting classroom activities defined by teachers. As the semester progressed, students designed architectural plans to improve learning environments and presented them to teachers and schools at the term’s end.

I served as the liaison between faculty and community partners – sharing experiential and service-learning best practices, and tailoring strategies to the local school context. These examples helped build mutual understanding and translated EE principles into practice. I guided both the professor and partner through key service-learning concepts and facilitated goal setting to align expectations and ensure both student learning and community relevance.

EE efforts often risk being fragmented. I worked intentionally to expand the project’s impact and sustainability. One approach was inviting additional community partners, students and campus leaders to the final public poster session, thereby increasing visibility and institutional awareness.

Early on, I recognised I would need to act as both activator and coordinator – managing deadlines, organising a mid-semester roundtable and overseeing the final event. I also led much of the foundational work to keep the project moving. Beyond logistics, I facilitated visioning with partners to embed long-term goals and community impact into the project. Unlike recurring EE programs, this new initiative required intensive presence, responsiveness and ongoing engagement.

This experience reinforced the demanding nature of launching EE projects – especially those with multiple external stakeholders. My role extended beyond coordination to relationship-building, contextual translation, and attentiveness to evolving needs. The emotional and logistical labor involved should be acknowledged in how institutions structure and support EE roles.

Reflecting on this project, I now recognise the importance of accounting for the time, capacity and relational effort required to develop meaningful EE initiatives. These factors must inform practitioner role design – especially for institutions aiming to scale experiential learning in community-driven, sustainable ways.

PRACTICE IN ACTION EXAMPLE TWO: CREATING A SHARED FRAMEWORK FOR EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING TO IMPROVE STUDENT SUCCESS BY REBEKAH HARRIGER

During my first few months in the role, I recognised the need for consistency, standards and a shared understanding of EE among faculty. Using SEE’s best practices, I reviewed and refined our experiential learning processes to emphasise intentionality, preparation and reflection. For instance, I worked with Program Leads to ensure learning objectives were clearly defined and aligned with both academic and career readiness goals, as well as our eight university core competencies. I also integrated structured reflection activities for faculty to embed in their courses to deepen student learning outcomes.

To create a collaborative model of EE, I organised regular university-wide training sessions for new and current faculty, providing a foundation in SEE’s best practices. These workshops focused on practical application and covered topics such as defining experiential learning, leveraging assessment tools, and developing meaningful experiences.

Implementing this training was challenging because the newly created content was unfamiliar to faculty participants. I also discovered tension between the former EE staff member and faculty. Navigating this as a new staff member required patience and relationship-building as I worked to establish credibility and gain trust. I leaned heavily on my supervisor – also a faculty member – to serve as a liaison while I immersed myself in HU’s experiential learning framework to align my approach with institutional priorities.

To support consistency, I created templates and resources such as reflection prompts, rubrics and a faculty guide to experiential learning. Recognising the need for a broad but adaptable approach, I designed these tools to align with high-level standards while allowing faculty to tailor content to their program or accrediting body.

To provide ongoing support, I reinstated our experiential learning committee to foster collaboration, troubleshoot challenges and share best practices. This helped ensure faculty felt supported and confident in delivering quality experiential learning. Through this initiative, I enhanced the consistency and quality of experiential learning across the university and strengthened partnerships between experiential learning staff and academic programs. Faculty gained a deeper understanding of how to design impactful experiences that prepare students for success, while students benefited from more intentional learning aligned with industry expectations.

2. Unlocking access points

Early research on boundary spanners illustrates a multifaceted role involving both resource management and the creation of pathways that enable others to access those resources. This process – ‘unlocking access points’ – is closely tied to the work of Roberts, Havemann and DeWaard (2023, p. 6), who describe boundary spanning as bridging ‘different domains of knowledge and ways of working’.

First, boundary spanners must identify where institutional knowledge resides and learn to navigate complex systems to retrieve it. Second, they play a crucial role in disseminating resources – expertise, networks, or materials – that are often inaccessible to outsiders but critical to EE initiatives. They must also create new avenues for access, which can involve launching innovative collaborations, using technology or developing partnerships to fill existing gaps. Institutions without centralised EE infrastructure face particular challenges: without supportive communities or established partnerships, boundary spanners may work in isolation, leading to redundancy or missed opportunities. Access points also function as hubs for mutual learning, enabling boundary spanners to share insights, best practices and support. By fostering these exchanges, boundary spanners are better equipped to navigate challenges and seize emerging opportunities.

Regardless of title, EE boundary spanners must prioritise information sharing to unlock access points. This means not only distributing resources but also building connections, dismantling silos, and working across institutional and external boundaries (Yip, Ernst & Campbell 2009). Sandmann et al. (2014) describe boundary spanners’ position at the periphery of organisations – a vantage point that requires them to reach inward to establish communication channels and partnerships. This strategic positioning enhances collaboration and access, amplifying the impact of EE.

The following stories from Rebekah Harriger and Katia Maxwell demonstrate how unlocking access points plays out in practice, showcasing their boundary-spanning strategies to advance EE on their campuses.

PRACTICE IN ACTION EXAMPLE ONE: EMPOWERING STUDENTS THROUGH ADAPTABLE, WORKFORCE-ALIGNED EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING BY REBEKAH HARRIGER

At Harrisburg University of Science and Technology, experiential learning is a keystone of the student experience. Students are required to complete 13 credits of experiential learning. However, as our programs have evolved, both students and faculty expressed a desire for additional opportunities to engage in experiential learning while earning academic credit. Our students found the 13 credits so valuable, and I started hearing that they wanted more options, more flexibility, and options that were better aligned with their career goals. Fortunately, faculty interests and support served as a tailwind force in our desire to expand opportunities for hands-on learning.

Recognising this need, my team and I implemented two new credit-bearing experiential learning courses that were flexible, allowing a specific experience to be awarded up to four units. Our team first identified the gap in available experiential learning options for students and the registrar’s office and the management of the course. Established relationships with students and faculty allowed us to quickly understand what was working and where the key opportunities were. I leveraged my relationships and understanding of campus technology, increasing our likelihood for scaling these courses. We have empowered students across programs to pursue additional career aligned experiential learning opportunities, providing them with an additional pathway in their career readiness. This initiative has not only met the demand for the expanded experiential learning opportunities but also strengthened our institutions experiential learning programs to prepare students for their future careers. These courses have also aligned academic offerings with workforce needs and institutional goals.

PRACTICE IN ACTION EXAMPLE TWO: EXPANDING EXPERIENTIAL PATHWAYS THROUGH EMERGING FACULTY MENTORSHIP PROGRAM BY KATIA MAXWELL

Athens State University is a distinctive institution with an upper-division model, meaning every student who enrolls is a transfer student from a two-year college or another four-year institution. In my dual role as both a faculty member and the Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP) Director, I quickly discovered that unlocking access points was key to supporting this diverse, largely non-traditional student population, as well as the faculty and staff who serve them.

One of my early observations was that many colleagues were already incorporating elements of EE into their teaching but without labeling it as such or having a clear way to share their work. To address this, I launched a monthly newsletter during the first year of the QEP, highlighting faculty leading innovative EE projects. The goal was to celebrate strong campus EL practices and spotlight adaptable models. I partnered with the provost to include announcements in campus-wide communications and used a blog platform to extend outreach and create a culture where faculty felt recognised and empowered to explore EE.

To foster more personalised support, we launched the EE Mentor Program. Faculty and staff – either volunteering or recruited for their expertise – serve as resources for anyone developing or refining an EE project. Their profiles appear on the QEP website, offering an accessible peer network for guidance on curriculum, assessment and community partnerships. With EE happening across campus but lacking centralised coordination, the QEP provides a unifying umbrella. As a signature initiative of the QEP, the EE Mentor Program now serves as a professional development hub connecting faculty to workshops, collaborators and community partners.

By breaking down institutional barriers, encouraging cross-departmental dialogue, and providing a clear mentor network, we’ve significantly expanded pathways to experiential learning. These efforts not only make EE more visible and attainable for faculty, staff and students but also set the stage for future growth – ideally culminating in the establishment of a dedicated EE office in the years to come.

3. Balancing stakeholder needs

In higher education, the role of a boundary spanner in EE requires careful consideration of multiple stakeholders to create meaningful opportunities. A primary responsibility of boundary spanners is to ensure that the diverse needs of all participants are effectively addressed, balancing the interests of each group involved. It’s a tough job. Hora and Millar (2011) offer effective communication and cultural brokering as key boundary spanner skills, which facilitate the inclusion of diverse perspectives and, in turn, may support balancing the needs of the various stakeholders.

Educating and communicating the concept of mutuality – and its practical application in collaborative activities – to stakeholders is essential. While faculty and students often share overarching objectives related to learning outcomes and skill development, the perspectives and needs of external stakeholders can be marginalised, creating unforeseen challenges. For instance, one author’s firsthand experience showed that faculty frequently outline goals for their students without fully considering the explicit needs of partnering organisations. As a result, a gap may arise between the outcomes envisioned for students and the additional requirements or constraints of these external partners.

Moreover, while a particular student group might excel at meeting one stakeholder’s needs, a boundary spanner can employ their skills as cultural brokers to identify ‘different models as contributors to the overarching goals and objectives of the partnership’ and to invite ‘dialogue about how to deal with those differences’ (Hora & Millar 2011, p. 87). This approach, in turn, can help identify other student groups to fulfill additional needs – maximising mutually beneficial partnerships. Ultimately, the success of EE initiatives depends on forming partnerships and building relationships that serve the interests of all parties. Boundary spanners play an indispensable role navigating stakeholder dynamics and cultivating collaborative engagement. The following example from practice illustrates how a boundary spanner can balance these diverse needs in practice that may resonate if you support faculty, navigate institutional demands or advance student learning.

PRACTICE IN ACTION EXAMPLE ONE: REALIGNING PROGRAM OUTCOMES TO MEASURE RELEVANT REAL-WORLD LEARNING BY TYLER HOUGH

At the Chicago Center, I led an internal academic self-study to document our student learning impact, highlight outcomes not easily captured in coursework, and align our programs with frameworks used by partner universities. We drew on established tools, including the AAC&U VALUE rubrics and NACE career readiness competencies, to assess how we delivered transformative experiences and how our efforts measured against widely accepted standards (See: https://www.aacu.org/value/rubrics; https://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/career-readiness-defined).

While these frameworks offered a strong starting point, I adapted them to reflect the immersive, justice-oriented nature of our urban courses. Early on, some faculty questioned our focus – such as prioritising intercultural competence over global learning – and debated which definitions would guide our goals. Even after reaching consensus, steps like introducing teaching observations or formal assessments raised concerns. One long-time faculty member remarked, ‘I’ve taught this course for a decade and worked in the field for 30 years. I know what works. What do you want to assess?’

To address scepticism, I illustrated how frameworks could support – not replace – expertise, using examples like neighborhood site visits, community interviews and reflective journaling. By connecting assessment to everyday student experiences, I reframed it as a tool to illuminate and celebrate strong teaching. In workshops and individual meetings, open-minded faculty embraced the question, ‘How does my teaching align with our intended learning outcomes?’ More hesitant colleagues began to see that our goal was to enhance – not challenge – their professional judgement.

Internally, I grounded this work in our values, showing how thoughtful assessment could strengthen our credibility and uphold our place-based mission. Externally, I translated these efforts for board members, advisory groups, and academic leaders – each with their own language and priorities. Demonstrating the value and rigour of our approach helped affirm that aligning with recognised competencies benefited students and met our affiliates’ expectations.

By bridging faculty perspectives, institutional demands and student needs, I honoured diverse interests while staying true to the Center’s vision. Mapping established frameworks to our mission allowed us to uphold faculty autonomy, support accountability, and affirm the transformative power of experiential learning. This balance enabled us to highlight curricular impact while speaking to broader academic standards.

PRACTICE IN ACTION EXAMPLE TWO: REIMAGINING GLOBAL LEARNING THROUGH COLLABORATIVE COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT BY DENNIS MCCUNNEY

Our institution has a strong tradition of community engagement and a commitment to regional social and economic mobility. Community-engaged learning is central to many of our EE programs, which are interdisciplinary and involve multiple stakeholders. Offices like the Center for Leadership and Civic Engagement and the Office for Global Affairs often serve as coordinating hubs but do not always oversee specific programming, budgets or outcomes.

While serving on East Carolina University’s alternative break planning team and the Global Affairs advisory committee, I recognised a gap: students needed short-term global learning opportunities that were flexible, affordable, community-engaged, and grounded in high-quality learning. Meeting this need with existing resources presented several challenges.

First, program overlap was common. Most students earned study abroad credit through individual departments, with faculty independently proposing programs – sometimes leading to multiple, simultaneous proposals for trips to the same location, like Switzerland. Second, integrating community engagement was difficult. While some faculty included service-learning, it was often dependent on personal initiative or third-party providers. Encouraging faculty to embed community partnerships required demonstrating how these collaborations could enrich student learning. Third, sustainability was an issue. Many programs ran only once, and cancellations due to low enrollment left faculty solely responsible, with little systemic support or reflection.

In response, I proposed an alternative model that prioritised equity and addressed student, faculty and community partner needs. We began by identifying community organisations aligned with our values – such as critical reflection, experiential learning and honouring local leaders as co-educators. We tackled recurring barriers like financial constraints, major restrictions, low enrollment and weak community ties. The resulting short-term global programs offered maximum flexibility, and students could earn independent study credit, even though the programs were housed in Student Affairs.

Initially, our push for flexibility and innovation was met with scepticism. A rigid divide between curricular and co-curricular programming had taken root. However, as the first programs launched, we identified improvements that benefited all stakeholders. A key breakthrough came from bringing together decision-makers from financial aid, study abroad, student affairs, community engagement and academic units – including the honours college. Their collaboration made the model viable. A college dean even joined one of our programs in Puerto Rico, gaining direct insight and building further support. This collaborative strategy created campus-wide investment and helped establish a sustainable, inclusive model for global experiential learning.

Today, these programs represent three things: true collaborative EE efforts, symbols of our institution’s service-minded ethos, and a deep commitment to student success.

4. Visioning and invigorating experiential education

Boundary spanners play a pivotal role in advocating for EE and ensuring its long-term sustainability. One of the most important tasks is to establish and regularly communicate a clear vision. They drive EE initiatives forward by fulfilling multiple responsibilities, such as educating collaborators and partners on best practices and aligning them with the overarching organisational vision for EE. Additionally, boundary spanners articulate and communicate shared goals for specific EE programs, helping stakeholders stay focused on intended outcomes. Central to this process is maintaining alignment with the mission and vision of EE, guiding partners to stay on track, and advancing targeted objectives within various contexts.

In higher education, boundary spanners serve as educators by translating EE principles to address the diverse needs of stakeholders, all while upholding universal best practices. They also foster collaboration among stakeholders who may have interconnected yet distinct goals, expertly navigating tensions and conflicts to keep everyone moving toward shared objectives.

Acting as the functional centre of EE initiatives, boundary spanners spur action and progression in both programming and practice. Recognising the competing priorities of partners, they launch and sustain EE activities, providing essential support to community partners and faculty who are integrating EE into their specific roles. They also spearhead continuous improvement by reviewing current practices, engaging with stakeholders, and making recommendations for enhancement. In essence, boundary spanners serve as catalysts for advancing EE, ensuring it continues to evolve and flourish in varied institutional settings. The following first-person accounts illustrate how boundary spanners bring EE visions to life, showing how strategic planning, stakeholder collaboration, and thoughtful program design can transform existing structures into robust, outcome-driven initiatives.

PRACTICE IN ACTION EXAMPLE ONE: TRANSFORMING MBA CAREER TREKS INTO EXPERIENTIAL PATHWAYS BY TYLER HOUGH

Upon joining the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University, I recognised an opportunity to refresh our existing career trek program. Although the treks received consistently positive feedback from students, it was not entirely clear how they supported deeper learning or linked directly to our broader institutional or departmental objectives.

I began by convening a group of internal stakeholders to clarify the primary objectives of our career treks and agree on a set of student learning outcomes. Together, we determined that students participating in each trek should increase their industry knowledge, develop more confidence in networking, and gain a clearer sense of how their skills align with employer needs. We then crafted an assessment strategy, including targeted survey questions that we administered at a specific point in the trek experience, to get near real-time insights into students’ learning.

By gathering data in person, while students just wrapped up their company visits, we not only achieved higher response rates but also collected richer feedback. From there, we used the survey results to refine future treks, ensuring that visits to innovative technology companies, for example, would deliver the learning outcomes we identified. This process provided tangible connections between our career treks and our school’s overarching mission of preparing students for impactful careers.

This newly designed program empowers students to:

–Understand how their current skills and interests align with – or need development to meet – industry demands

–Deepen their knowledge of specific industries and career pathways

–Identify actionable steps to secure employment in their chosen fields

–Build confidence in networking and professional interactions.

By grounding career treks in clear learning objectives and refining them through real-time student feedback, we transformed the program from a series of site visits into a strategic experiential learning experience – one that better supports students’ professional development and advances our institutional goals.

PRACTICE IN ACTION EXAMPLE TWO: LAYING THE FOUNDATION FOR A CROSS-CAMPUS EE COLLABORATIVE BY KATIA MAXWELL

While my initial efforts as QEP Director focused on raising awareness of EE and providing immediate resources, it quickly became clear that long-term success required a broader vision – one that fully embedded EE into the fabric of Athens State University. As an upper-division institution serving exclusively transfer students, we needed a cohesive plan that leveraged our strengths and aligned with the varied goals of students, faculty and external partners.

From the beginning, I identified the absence of a centralised EE office as a critical gap. Strong initiatives – ranging from sponsored student projects to community-engaged research – existed across departments but remained siloed. I began advocating for a dedicated EE office, staffed by professionals who could coordinate and elevate experiential opportunities. Consolidating efforts would streamline access for internal stakeholders and external collaborators alike.

Simultaneously, I worked to build the infrastructure to support such an office. A key move was launching professional development for faculty and staff. Using QEP funds, we sponsored participation in national workshops and conferences, exposing our team to leading-edge practices. We also created the Experiential Learning Faculty Fellowship Program, offering internal grants to support curricular and co-curricular innovation. This encouraged experimentation and generated data on what works in our upper-division context.

Equally important was consistent campus communication. Through newsletters, blog posts and provost-led announcements, we shared success stories to foster a sense of shared ownership. The goal was to lay a strong foundation so that when an EE office is formally established, faculty are ready to lead, and students clearly see its relevance to their personal and professional growth. We have also ensured EE remains responsive to workforce trends and the evolving needs of our transfer student population. Ultimately, our vision is for experiential learning to be a fully integrated part of our institutional identity – preparing students with the skills, insights and experience they need to thrive.

As both faculty and QEP Director, I approach the framework’s pillars from different angles. In teaching, I lean on Pillars 1 and 3 to directly impact students and curriculum. In my leadership role, I focus on Pillars 2 and 4, recognising the need to equip faculty and staff with the tools and structures that make EE effective for both students and community partners. Through this work, we have taken key steps toward building a sustainable, inclusive ecosystem for EE – aligned with our mission and built to adapt to future needs.

Implications and further lines of inquiry

How, then, can these evolving takeaways from the lived experiences of a collection of boundary spanners both contribute to the field and be applied in other contexts? We offer a few suggestions that can serve as a heuristic for others hoping to enhance their professional practice.

In one sense, these four pillars remind us of the need for a certain amount of executive maturity and political wherewithal to help boundary spanners be successful. The ‘push and pull’ of cultural rules within organisations – and specifically within higher education institutions – can slow the work of effective partnerships and progress. As noted above, boundary spanners cannot simply check off items on a ‘to-do’ list to accomplish their work. Rather, they must carefully cultivate relationships and navigate culture over time. The ability to see the ‘big picture’, demonstrate sound judgement and resist siloed behaviour can allow boundary spanners to navigate different cultural spaces and achieve common goals. This leadership quality can be honed over time and serves as a particularly useful skill in most contexts. So, the proposed framework should also be viewed as an approach to professional development for experiential educators. Further inquiries could examine the extent to which boundary spanners demonstrate executive maturity skills and how that competency contributes to their own success.

Building on the notion of competency development, as a group of co-authors, we often discussed the important role of self-care within this framework. As originators, builders and sustainers, where do boundary spanners get their ignition? A certain amount of intrinsic motivation and institutional thinking helps to make effective boundary spanning work happen in EE contexts. When this is the case, what is both the cost and the benefit to the individual professional? How can a supportive community – much like our community of SEE fellows – provide guidance and serve as a sounding board when the boundary spanning role is less understood and underappreciated? And how can these types of support networks prevent burnout? These are other lines of inquiry that could contribute to improved morale among professionals and, ultimately, employee retention.

Conclusion

Our process of articulating these guiding tenets – translating principles of practice, unlocking points of access, balancing stakeholder needs and envisioning and invigorating EE – helped to give meaning to some of our lived professional experiences. While this is a working model that should be critiqued and molded to fit one’s needs, it can serve as a guide for others who occupy these unique spaces within higher education settings. To reiterate, this model is meant to serve as a guide for practice and should be adapted to particular contexts, rather than strictly followed. Through our collective case study process, other questions – like self-care for boundary spanners, resources for professional development, needed competencies like executive maturity – emerged as future areas of exploration. In the end, effective – and well-supported – boundary spanners can provide high-quality, transformative learning experiences for our students and community partners. This serves as the ultimate measure of our success as educators.

References

Andreasen, JK 2023, ‘School-based mentor teachers as boundary-crossers in an initial teacher education partnership’, Teaching and Teacher Education, vol. 122, no. 2, pp. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103960

Benaquisto, L 2008, ‘Codes and coding’ in LM Given (ed), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods, SAGE Publications Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 86–89.

Green, PM 2023, ‘The scholar-administrator imperative: Developing scholarship and research through practice to build the community engagement field’, Metropolitan Universities, vol. 34, no. 3. https://doi.org/10.18060/26863

Hora, MT & Millar, SB 2011, A guide to building education partnerships: Navigating diverse cultural contexts to turn challenge into promise, Routledge, New York.

Lee, L, Horth, DM & Ernst, C 2014, Boundary spanning in action: Tactics for transforming today’s borders into tomorrow’s frontiers (White paper), Center for Creative Leadership, https://doi.org/10.35613/ccl.2014.2044

Merriam, SB & Tisdell, EJ 2016, Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation, 4th edn, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Ravitch, SM 2014, ‘The transformative power of taking an inquiry stance on practice: Practitioner research as narrative and counter-narrative’, Perspectives on Urban Education, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 5–10.

Roberts, V, Havemann, L & DeWaard, H 2023, ‘Open learning designers on the margins’ in T Jaffer, S Govender & L Czerniewicz (eds), Learning design voices, EdTech Books, pp. 41–56. https://doi.org/10.59668/279.12262

Sandmann, LR, Jordan, JW, Mull, CD & Valentine, T 2014, ‘Measuring boundary-spanning behaviors in community engagement’, Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 83–96.

Stringer, ET 2007, Action research, 3rd edn, SAGE Publications Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Williams, P 2011, ‘The life and times of the boundary spanner’, Journal of Integrated Care, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/14769011111148140

Yip, J & Ernst, C & Campbell, M 2009, Boundary spanning leadership: Mission critical perspectives from the executive suite (White paper), Center for Creative Leadership, viewed 28 May 2025, https://cclinnovation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/boundaryspanningleadership.pdf