Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 18, No. 1

January 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE (PEER REVIEWED)

Curating Life in Vacant Spaces: Community Action Research and Reversing the Process of Academic Knowledge-Making

Kelly Dombroski1,*, Rachael Shiels2, Hannah Watkinson3

1 School of People, Environment and Planning, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa | Massey University

2 Placemaker, Former Director, Life in Vacant Spaces

3 Placemaker and Ōtautahi Christchurch Enthusiast

Corresponding author: Kelly Dombroski, K.Dombroski@massey.ac.nz

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v18i1.9296

Article History: Received 19/08/2024; Revised 30/10/2024; Accepted 18/11/2024; Published 01/2025

Abstract

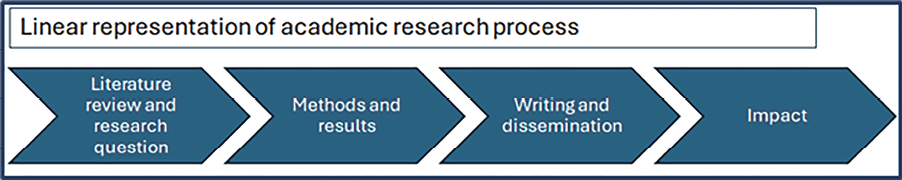

For scholars in academic institutions, the process of research usually begins with a question often gleaned from academic literature, progresses through some methods and results, then ends in writing and dissemination of the findings. ‘Impact’ is identified by trying to see if anyone takes up the research and uses it to inform policy or action outside of academia – with contemporary impact databases measuring this by whether it has been cited in policy documents. But this way of understanding impact is fundamentally at odds with researching community-led activism, where impact is already happening, and researchers engage with communities to document and evaluate the impact in ways that support the work. For activists out in the community, research and learning are happening all the time and have impact without anyone writing it up at all. This paper reflects on a research project in the city of Ōtautahi Christchurch in Aotearoa New Zealand, where researchers and community activists began with ‘impact’ and ‘dissemination’. From there, we developed frameworks and methods, developed evidence, then ended with asking wider theoretical questions relevant to academic literature. Effectively, we reversed the order that research projects usually follow. In order to recognise this ‘reversed’ order, our paper utilises a reversed structure, using the concept of thinking infrastructures to understand what academic research adds to the knowledges already produced in community impact.

Keywords

Impact; Transitional Place-Making; Community Action Research; Christchurch, New Zealand

Beginning with the end

For those of us who are scholars in academic institutions, we often frame our work as if the process of research begins with a question gleaned from academic literature, progresses through some methods and results, then ends in writing and dissemination of the findings (Bhattacherjee 2012). ‘Impact’ is often identified by trying to see if anyone takes up the research and uses it to inform policy or action outside of academia (Australian Research Council 2019) – sometimes measured by whether it has been cited in policy documents. (See, for example, the metrics developed in Scopus, https://blog.scopus.com/posts/see-how-your-research-impacts-policy-overton-policy-citations-are-live-on-scopus.) There is a certain degree of pressure to represent our work in this way, especially in the New Zealand funding environment, in turn shaping and resourcing some of the work we have been engaged in – a process known as ‘funding drift’. But this way of representing impact is at odds with researching community-led activism, where it is important to acknowledge that impact is already happening, and that researchers engage with communities to document and evaluate the impact. For activists out in the community, research and learning are happening all the time and have impact without ever being documented, and it would be disingenuous to erase this kind of impact from the research writing process.

This paper seeks to write about impact differently by reflecting on a research project in the city of Ōtautahi Christchurch in Aotearoa New Zealand. In this project we, as researchers and community activists, began with impact and dissemination. From there, we developed frameworks and methods and then ended with asking wider theoretical questions relevant to academic literature. In some ways, we could playfully suggest that we reversed the order that research projects might normally be expected to follow (see Figure 1), joining others in this special issue and elsewhere participating in iterative changes in the relationships between research, communities, writing and institutions. The long tradition of museum and exhibition curation has also influenced the way we have approached telling stories of community action and impact.

Figure 1. Linear representation of the research process

Rather than beginning with a literature review, this paper commences with the context and impacts of the temporary use organisation, Life in Vacant Spaces (LiVS). We will then move on to ‘Telling stories’, a version of writing and dissemination, then outline our approach to ‘Developing the evidence’ in a version of methods and results, finally finishing up with engaging with the literature and highlighting a research question for ongoing contemplation and research. This ‘reversed’ approach to the paper allows us to lay out the context for our decisions in writing research differently, both in this paper and in the order of the outputs we produced during the project. We invite the reader to join with us as we work through context, stories, decisions and questions in this unconventional way.

This paper is led by our work with the charitable trust, LiVS, a community organisation in the city of Christchurch. LiVS is one of many ‘transitional’ organisations that emerged following the Canterbury earthquakes of 2010 and 2011. The Canterbury Earthquake Sequence (CES), which began in late 2010, saw destruction on a scale previously unseen in New Zealand: 80% of the central city of Christchurch collapsed or was later demolished; core infrastructure across the city was damaged beyond repair; homes, livelihoods and communities were destroyed; and 181 people lost their lives (Hayward 2013). For over a decade, Christchurch has been responding, rebuilding and regenerating. We collaborated on a project at the end of that decade, in 2021 and 2022. We met through our association with LiVS: Rachael was director from 2018–2021; Hannah was a previous community partner with the organisation and worked coordinating a project from 2018–2023; and Kelly wrote about the organisation in another research project (Dombroski, Diprose & Boles 2019) and then was invited to join the board, serving from 2018 to 2022.

After the earthquakes, local and central government began planning for the recovery of the city relatively quickly. The Draft Central City Recovery Plan was prepared by December 2011 for ministerial approval. The plan outlined the opportunities created by the CES to ‘rebuild a strong, resilient and beautiful city’. But even quicker was the community response. Hugh Nicholson, previous chair of LiVS, writes:

One of my vivid memories about two months after the first of the devastating Canterbury earthquakes in 2010 / 2011 was walking down a deserted Colombo Street surrounded by broken buildings and empty sites, and seeing a flash of colour and people with music on a vacant section. It was a crazy temporary public garden with live music, poetry readings, a bit of puppetry and circus, and film screenings of old New Zealand movies with live musical accompaniment. It was my first realisation that ordinary people doing stuff on an empty section could make a difference – and help to bring a broken city back to life (Dombroski et al. 2022, p. 2).

Following these first quick and creative interventions, the longer post-quake transitional movement saw the community coming together and demonstrating a profound commitment to reinvigorating, and occasionally reinventing, the city (Bennett et al. 2014; Cloke & Conradson 2018). A handful of small organisations led the charge, but the movement attracted local creatives, business-owners and residents as well as students and visitors from around the world. The council supported the projects by allocating specific funding and temporarily removing some of the regulatory barriers to activation, thus further growing the movement of transitional activities (Carlton & Vallance 2017; Cloke et al. 2023; Dombroski, Diprose & Boles 2019).

The transitional movement helped enable a sense of ownership or belonging in the rebuilding process and supported conversations around what the new city could (or should) include (Cloke et al. 2023; Cretney 2018). Early projects were playful, run on shoe-string budgets and rebuilt connections with the city and each other. Hundreds of projects were delivered and some were eventually incorporated into the permanent fabric of the new Christchurch: the Dance-O-Mat (Figure 2), Rollickin’ Gelato (Figure 3) and the Arcades for example. The movement has been recognised globally and, in 2014, the transitional programme won a Guangzhou Award for Urban Innovation.

Figure 2. Dance-O-Mat (Location 4). Photo credit: Gap Filler

Figure 3. Rollickin’ Gelato – then and now. Photo credits: Rollickin’, Neat Places

LiVS was one of the key partners in the transitional movement. It was established as a charitable trust in 2012 in response to a report commissioned by Christchurch City Council looking at mechanisms to better enable the transitional movement in the post-quake context. LiVS has, and continues, to broker spaces for community groups, creative projects, social enterprises and start-ups; it seeks to connect owners of vacant land and buildings with creative people who have ideas, to fill these spaces. LiVS also provides support for creatives, right from the development of an idea through to project deinstallation. As one LiVS partner commented:

I think LiVS is a really great enabler…LiVS works. So, there is a removing of barriers that happens when you work with Life in Vacant Spaces. They take care of the bureaucracy, the paperwork, the leg work of finding spaces and developing relationships with landlords. They really create potentiality out of spaces which are otherwise just sitting unused. That’s for a city where there is a lot of those spaces still. That’s so invaluable, really. (Project Participant, in Dombroski et al. 2022, p. 7)

LiVS has enabled a wide range of projects. Since its inception, it has supported the delivery of over 700 projects. In particular, it has:

• provided and managed space in an abandoned school for a community of artists, including Free Theatre;

• partnered with Gap Filler, which uses temporary space to create temporary urban projects to foster community engagement and creativity such as the music and food venue Pallet Pavilion (Figure 4);

• brokered use of land for the Festival of Transitional Architecture (FESTA, Figure 5);

• provided space for Christchurch Aunties to store furniture and everyday supplies for women’s refuges and their clients;

• brokered land for Cultivate Christchurch, which integrates youth employment training and organic urban farming to support youth wellbeing;

• brokered indoor and outdoor spaces for The Green Lab, which focuses on urban greening and community connection through temporary landscaping projects;

• supported the use of council land for A Local Food Project, which engaged the community in local food production, sustainability and community food consumption initiatives;

• supported a young person to start a gelato business in a caravan on temporary-lease land, which is now a chain of gelato shops (Figure 3);

• supported the New Brighton community to self-manage Roy Stokes Hall for a variety of community projects including circus training, playgroups and events;

• supported Watch This Space to get permissions for urban art projects and exhibitions to enhance public spaces;

• found temporary accommodation several times for RAD Bikes, which recycles and repairs bikes to promote sustainable transportation and community engagement;

• subsidised spaces at Salt Lane Studios, a workspace for artists and creatives to collaborate; and

• managed East x East, transforming vacant earthquake damaged land into community spaces for various projects and activities, including Redzone Drone Racing, art interventions, an all-ages club for building and racing drones and Disc Golf at East x East.

Figure 4. Pallet Pavilion. Photo credit: Maja Moritz

Figure 5. FESTA 2016: We Have the Means. Photo credit: Jonny Knopp, Peanut Productions

Impact

While it was obvious to us, the participants, and the LiVS organisation itself that the work was making a big impact, it was hard to communicate and evaluate the work due to its multifaceted nature. Wellbeing benefits were clear to us in several ways. First, from our experiences with LiVS-enabled projects, community involvement in repurposing vacant spaces fostered a sense of belonging and improved social wellbeing. For example, The Temple for Christchurch project (2013) was a large-scale interactive art installation made from wood and other materials, designed to commemorate the 2011 earthquake and provide a space for emotional healing through community participation and the ceremonial burning of the temple. It did this by allowing people to participate in the construction and collective burning of the temple, whilst openly expressing and (however briefly) recording their losses and grief (Figure 6). This initiative fostered unity, resilience and psychosocial recovery, contributing to the city’s cultural revival and overall wellbeing.

Figure 6. Temple for Christchurch. Photo credits: Gaby Montejo

We also saw environmental benefits where unused spaces were transformed into green areas or community gardens, which has a positive impact on human mental health and overall wellbeing as well as benefiting non-human life. ‘Cultivate Christchurch’ is a social enterprise that transformed vacant post-quake land into urban farms, promoting social wellbeing and environmental sustainability. It significantly improved environmental health by collecting and converting green waste into rich soil on a previously gravel site, producing high-quality fresh produce (Figure 7). It also positively impacted individual wellbeing by providing meaningful work, time outdoors and in nature, social worker support and skill development opportunities for young people in Christchurch.

Figure 7. Cultivate Christchurch. Photo credit: Alison Watkins

Economic wellbeing outcomes were evident both for those starting out in small business and the overall economic improvement of areas when vacant spaces were filled with interesting activities or enterprises that lent a sense of vibrancy. One example is the public pizza oven created as part of ‘A Local Food Project’. This initiative enabled chef, Alex Davies, to trial his menu and gather a following for his food in a public space, eventually leading to a partnership in a restaurant space. This project contributed to sustainable economic wellbeing by supporting livelihoods and fostering a circular economy through the redesign, reuse and recycling of materials, as well as Davies’ own livelihood.

Finally, we saw that projects could strengthen social ties and, it seemed, contribute to resilient communities in the post-quake environment which were crucial for enhancing the collective wellbeing and sense of ‘rightness’ in the wider city. For example, the Roy Stokes Hall in New Brighton was transformed into a community hub, providing a versatile space for various community activities and events. This project strengthened social ties by offering a venue for community groups, workshops, performances and educational activities, fostering a sense of belonging and collaboration among residents in the suburb.

For all those involved, these benefits and more were evident, but it was and is difficult to link these benefits directly to LiVS’ activities, and to measure the ‘value’ of these activities. Many transitional organisations and social NGOs in Christchurch (and elsewhere) have trialled different ways of evaluating and communicating impact, including through story-telling, outcome harvesting, case studies, community return on investment approaches and infographics (Figure 8). Determining value and communicating it well is often a significant challenge for charities, not-for-profits and many in the creative sector; LiVS is no exception to this. Project numbers, area of space filled, and estimated lease or rental savings are easily counted and communicated. The intangible benefits – connection to place, improved wellbeing and increased community participation, for example – defy traditional valuation. This presents challenges when communicating with potential participants, delivery partners, sponsors and funders. Being unable to provide empirical evidence of benefit or improvement can create perceived risk to those looking to invest time or resources into the project(s).

Figure 8. Infographics produced by Gap Filler to communicate their impact

The research project came about near the 10-year anniversary of LiVS, with researchers collaborating with LiVS staff to conduct some research to better consider (and communicate) some of the impacts LiVS’ projects have had on community wellbeing and how these can be measured. The project action team (the authors) met with the board to set the priorities for the research project. We identified an exhibition and a book as suitable starting points for the collaboration, with the data collected for those outputs to be used for later research on evaluating and communicating LiVS’ impact. We identified these as appropriate since they were able to give greater visibility of the wellbeing impacts of LIVS’ work to residents, visitors, funders and city council. The book could be sent to people to read, and the exhibition could communicate to casual city visitors or commuters who might not otherwise read such a book.

The first task was to identify the wide range of perceived impacts and projects, and select a sample to feature in the first outputs for the action project. Rachael and Hannah, working closely at LiVS for a number of years, were able to select 34 projects from around 700 to feature in a book and exhibition celebrating the 10-year anniversary. There were a number of practical considerations in choosing the projects to feature, such as whether they had good records, photos available and some level of existing contact for permissions and possible interviews. However, our decision-making also sought to identify the significant stories to be told or revisited; those projects that were memorable, that influenced future decision making, catalysed a career or community group or project or that made a deep emotional connection. It was a strange collection of ‘somethings’, all with markers of what we intrinsically considered to be ‘impact’ but still needed to be ordered and explored to make sense. This was a reflection of a lot of the work we did at LiVS; seemingly quite bold decisions (which projects to support, which vacant space to activate, which projects to include in the exhibition) were made quickly due to the context but felt deeply and further rationalised once learnings had occurred.

We made sure to include examples from the East x East block, a vast block of land that had previously been residential and was now being activated with suburban activities by LiVS (Figure 9), as one of our funding agreements was with specific reference to this area. Kelly set out to interview participants and desk research these projects, finishing up with 27 stories (Dombroski et al. 2023). These were written up as case study summaries drawing on transcripts. After this, we faced the challenge of deciding how to present these for exhibition and in a book.

Figure 9. East x East Learn to Ride track. Photo credit: Hannah Watkinson

Telling stories: Writing and dissemination

The stories told in the interviews formed the basis of the material for the exhibition. In this section, we use a story-telling mode to open up the black box of research and writing decisions, acknowledging a range of influences including how we feel, what seemed practical and the different objectives of the community and research partners.

The exhibition started with a basic table, ordered simply by whichever interview transcript Kelly opened first. Because we didn’t really know what the exhibition would quite do, Kelly tried to map the work of each project, organisation or initiative against a range of different frameworks already used in wellbeing economies work in Aotearoa New Zealand. The idea was to present a range of possibilities from frameworks that seemed to broadly communicate alternative forms of ‘value’ in different ways. These were all frameworks Kelly had come across in her research and teaching in community, wellbeing and place. This felt fun – learning all the frameworks, reading through the transcripts and thinking about what was being achieved. These were:

• The Mauri Ora Compass, developed by colleague Amanda Yates, is an urban design tool that tries to bring conception of mauri ora, or holistic wellbeing, into urban design (Yates et al. 2022). It communicates value from a te ao Māori perspective, in terms of what an initiative contributes to the mauri (life force) of a place.

• Te Pae Mahutonga, a public health framework developed by Tā/Sir Mason Durie that lays out a set of public health conditions, including physical environments, needed for holistic Māori health and more broadly for health in Aotearoa New Zealand (Durie 1999). It communicates value in terms of whether and how something contributes to public health, informed by Māori cultural values but applicable more widely.

• The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a set of global goals developed to funnel and track progress into a set of 17 holistic goals (sdgs.un.org). They contribute value in terms of whether an initiative helps society progress towards one of the 17 internationally agreed priorities.

• The Community Economy Return on Investment (CEROI) approach is a set of six areas of investment that bring community economies (organised around six key wellbeing questions) into being (Gibson-Graham et al. 2013). It communicates value in terms of whether an initiative contributes to economic and social justice as well as environmental care outcomes.

• The Five Ways to Wellbeing is a mental health intervention that focuses on the things that individuals can do to benefit their own wellbeing. It communicates value in terms of whether an initiative could benefit individual wellbeing. This one was not used as it did not allow for analysis of the impact of community and environment in wellbeing, which was important for our communications with funders and our analyses with social and environmental change theory.

We then met to discuss what the benefits of the frameworks and decided on two: first, the Mauri Ora Compass, which drew attention to the holistic wellbeing outcomes of the projects; and secondly, the CEROI, which drew attention to the investments and intentions. While neither of these are widely used frameworks, the project was seen as an opportunity to draw more public attention to the innovative work of our colleagues, Amanda Yates, JK Gibson-Graham, Jenny Cameron and Stephen Healy. Rachael then took this table and created two documents: one, a layout of the booklet with thought about where quotes and project photos would go; and a second more condensed but visual version, created with Hannah to plan the layout for the exhibition panels (see Box 1: Rachael and Hannah’s Reflections). The eight double-sided panels were eventually printed in A0 size (841 × 1189 mm) and installed in a public laneway in the centre of Christchurch.

| Trying to shape the interviews and the case studies into an exhibition (Figure 10) and booklet was incredibly challenging. Turning all that wonderful creative chaos into something linear whilst remaining true to the individual voices, the projects of others and Ōtautahi’s ever-changing context caused many late nights for us! It really wasn’t until we settled on our frameworks that it even seemed possible; a real ‘a-ha’ moment! Considering the ‘why’ (or many) behind a lot of the projects reinforced their impacts and better helped us to tell that story. |

Figure 10. Huritanga: 10 years of transformative place making exhibition. Photo credit: Life in Vacant Spaces

The process of writing the booklet and preparing the exhibition was one of feeling our way forward. The experimental use of two frameworks (the ‘Mauri Ora Compass tool’ and the ‘Community Economy Return on Investment (CEROI) tool’) provided insights into the impacts, writing and dissemination that then needed some further examination. Both frameworks were experimental in nature and had not been developed in robust ways or widely used. Thus, the work that we did to use them to frame our exhibition and booklet was both a realisation of the holistic value of the LiVS’ work and also an experiment in seeing how the frameworks would go with communicating holistic impacts. The process of writing also raised the questions of how to think about the impacts more broadly and how to categorise them in a meaningful way. The process of developing the visual language with the designer (Figure 11), choosing images and deciding what to select or leave out, also stimulated our thinking on the meaning of the impacts. As Lykke et al. note with reference to writing: ‘This struggle should not be reduced to a wrapping-up of research results following the “serious” part of the research… [because] thinking and writing are two sides of the same coin’ (Lykke et al. 2014, p. 2). For us, this was also true in terms of design, image selection and the curatorial planning of the exhibition and booklet.

Figure 11. Huritanga: 10 years of transformative place making book. Design: Jen McBride

Developing the evidence: Methods and results

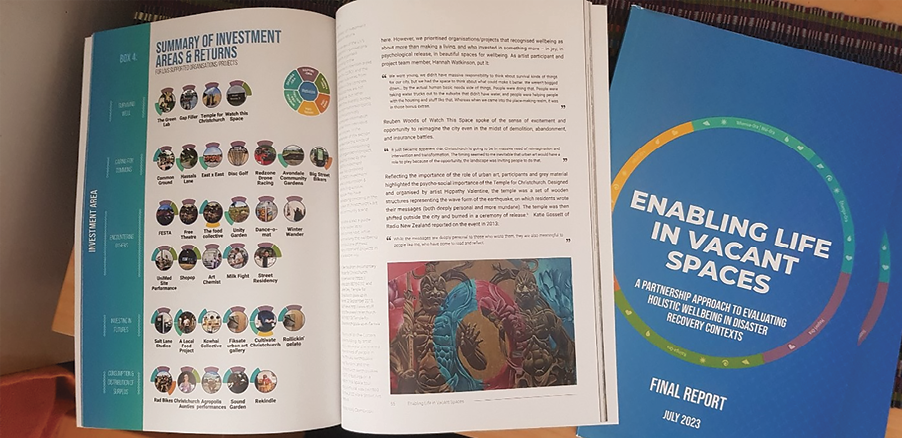

With the exhibition and booklet complete, we realised we had drawn attention to the wellbeing outcomes of LiVS-enabled projects but for city councillors and other funders to act on that, we needed a formal peer-reviewed report. Kelly collaborated with other academics working on the National Science Challenge-funded programme ‘Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities’ to gather the evidence to support the methods and results, and to write a peer-reviewed report that would then underpin what the exhibition and booklet had asserted with regard to wellbeing impacts. When spelling out the methods (including selection of projects), we framed these as a community action research project (Cameron & Gibson 2020) where communities contributed to developing the research question and approach. This provided an explanation and justification for the community-led process undertaken, situating it in wider peer-reviewed approaches. The report writing involved systematically re-analysing the interviews via a structured NVivo process, writing up the individual case studies and then writing up thematic analyses with reference to literature and evidence (see Dombroski et al. 2023). While much of this was done by Kelly, the entire report was read and commented on by the co-authors, with significant edits by Gradon Diprose (see Box 2).

The report writing process thus built on the big picture thinking and analysing done in the exhibition and booklet, while providing the evidence base for decision-makers. More than 50 copies of the report were distributed around city councils, consultancies, regional councils and place-making organisations. The report has an ISBN and is archived with the National Library of New Zealand. The style of the report was formal, developed by a designer with experience in the design of government reports (Figure 12). It was then sent to two peer reviewers in the Community Economies Research Network (one in NZ and one international), and changes made based on their review.

Figure 12. Enabling Life in Vacant Spaces final report

Writing differently: Literature and research questions

There is not necessarily anything radically different about beginning with community impacts and working back to academic theorising via methods and evidence somewhere in the middle. This is the way that many impacted communities become involved in research projects – noticing impacts and wanting to think about why, or how – or to tell others what is happening. Kaupapa Māori research, for example, is premised on the idea that Māori (and indeed, Indigenous communities more broadly) know what they need research on, and why it’s important, and that researchers should partner with communities rather than do research ‘on’ them (Tuhiwai Smith 2012). Feminist research has a long history of taking women’s words and interpretations of their own lives seriously, including reframing and inventing new concepts, words and analyses to support it (Cameron 1996; Kitzinger 2004). Community-based research also has a tradition of beginning with what communities know rather than imposing expert interpretations and knowledges, albeit often involving external experts in participatory research (Chambers 1997) and not always returning the findings back to the community (Scheyvens, Scheyvens & Murray 2014). In many ways, this project has been influenced by all those traditions.

What else is happening here, though? Is it only a ‘taking communities seriously’ approach, or is there something else going on in this project? One way of thinking about what is happening is to think about how research can provide not only ‘evidence’ but also language and ‘thinking infrastructures’ (Bowker et al. 2019) to frame what communities are already doing. LiVS already existed as an NGO and assemblage of people, things and processes creating space for temporary use projects. But the process of doing the exhibition and the booklet, the interviews and the report, pulled together a community that did not exactly exist before as a named object, and structured a language and thinking infrastructure around the work of that community. In partnership, the shared research developed and inserted a language of wellbeing and investment into the community it gathered. The research organised and categorised projects and outcomes around ‘mauri ora’ (our state of being, where our life force is in balance; we are alive, well and full of vitality), inviting readers to see the work in the city as something more than economic development or filling gaps while waiting for the ‘real’ rebuild. Like other research in the area of temporary use, our work invited those viewing the exhibition, or reading the booklet or the report, to see the work of temporary projects in transitional spaces as something more than gap-filling, as restorative of and attentive to the mauri or vitality in the city (Carlton & Vallance 2017; Chatterton et al. 2019; Dombroski, Diprose & Boles 2019; Vallance et al. 2017). It provided this thinking infrastructure while also building the evidence base for decision-makers to act further in caring for mauri ora.

In the same way that the scientific process is a thinking infrastructure that organises what is happening and translates it into a wider audience for learning, our research project began with skilled observations by place-makers such as Rachael and Hannah, then utilising Kelly’s research skills and funding to investigate and ‘translate’. The thinking infrastructure in this work has been the different wellbeing frameworks that organise and translate the work of LiVS for wider audience learning. In this way, ‘what and how we write is directly related with who we become’ (Gilmore et al. 2019, p. 9).

In short, it is not only writing that reconfigures who we are, but also the infrastructures we think with. Thinking infrastructures ‘configure the user, cognitively’ (Bowker et al. 2019, p. 2). Knowledge-making is never neutral; we therefore need to think carefully about the kinds of academic knowledges we are generating and who we are generating them for. We are not fully separate or even cognisant of the thinking infrastructures we are part of, but when we work with others we can sometimes glimpse the edges as we communicate across difference and lean into moments of awkward engagement (Dombroski 2024; Tsing 2005). The thinking infrastructures that centre researchers as the ones holding or creating knowledge, and community partners as ‘subjects’ or ‘participants’, have been roundly challenged by scholars of science and technology studies (STS) as well as the aforementioned fields of Indigenous research, feminist research and community action research. STS researcher, Annemarie Mol, for example, highlights how the thinking infrastructure of ‘client choice’ in healthcare produces perverse outcomes, in that ‘clients’ are forced to choose a provider then go with whatever that provider offers in terms of their standard healthcare. But when healthcare workers lean into the also present (but less obvious) thinking infrastructure of ‘patient care’, outcomes can be better and negotiated in partnership as things change in the patient’s circumstances (Mol 2008).

Leaning on Mol’s work, we can see it is not necessarily that researchers create thinking infrastructures and then apply them to the impacts that organisations such as LiVS produce, but that a role of researchers is listening and uncovering the traces of those infrastructures already present in a minor key, or in a less organised way. How then do those of us doing research partnerships such as this one decide which thinking infrastructures to excavate and highlight? Writer and activist, adrienne maree brown insists that it has to be about listening to those most affected (brown 2017). Michel Callon and Vololona Rabeharisoa proposed that ‘it might be fruitful to consider concerned groups as (potentially) genuine researchers, capable of working cooperatively with professional scientists’ (Callon & Rabeharisoa 2003, p. 105). For Callon and Rabeharisoa, this kind of collaborative research with those most affected was theorised using the concept of ‘hybrid collectives’, where the ‘hybrid’ is referring not only to the combination of researchers and concerned groups, but also to the technologies and non-human entities that are part of the research (Roelvink 2016). Such research ‘in the wild’ is guided by the matters of care (to use Puig de la Bellacasa’s 2017 language) and concern (to use Latour’s 2004 language) to those most affected. Those co-researchers also participate in co-researching and interpreting what thinking infrastructures that emerge to represent and frame the questions, findings and implications.

In the community action research that we have discussed here, the knowledge production of science is not necessarily at the centre of the work. Rather the co-researching relationship is akin to curating. Curating, at its heart, is the piecing together of smaller stories to create a bigger picture; or arguably, knowledge production. Curating is how we would describe the work that Rachael and Hannah did as part of the LiVS organisation, enabling a range of community projects to be realised in certain spaces. Curating is by definition selecting, organising and looking after something (Oxford Dictionary). It is packaging something to display or share more widely, and in the choosing of the ‘something’ in a placemaking sense, and indeed in the culmination of the book and exhibition, all of these thinking infrastructures need to be known, understood and purposefully progressed.

In the LiVS project outlined here, the curatorial approach that LiVS takes towards assembling core projects in the city is replicated in the curatorial approach taken towards assembling projects into the exhibition, book, report and the thinking infrastructures that emerged. Not everything is represented, but a story with a purpose is told through the curation of stories, images and quotes. In many ways, the curators had the vision and power to select from the research infrastructures offered by the research team, choosing those that best served the project as first envisioned. The research question is thus less one of ‘what is happening here in temporary use projects in Ōtautahi and what are the results?’ and more one of ‘how can we share what has happened here with temporary use projects in Ōtautahi and, both sustain and share the results with others?’ or perhaps even ‘how can we continue to curate wellbeing through temporary use both here and elsewhere?’.

Ending with beginnings

So, we end with research questions that have emerged through this project. How indeed can we and others continue to curate wellbeing through temporary use both in Ōtautahi Christchurch and elsewhere? Each of us has gone on to answer that question in different contexts in the year since the project was completed with the final report (Dombroski et al. 2023), and those continuing on with the work of LiVS or research into temporary use in Christchurch might also answer the same question. LiVS continues its work with a focus on the incubator project, a shipping container for temporary use pop-up projects right in the centre of the rebuilt city. Hannah has moved into the local government space focussing on community hazard protection, as well as strategy work to enable communities, mana whenua and territorial authorities to imagine and work together toward aspirational environmental visions for place. Rachael continues her regeneration efforts with communities, specifically focussing on place-led development and partnerships, through a role with the local economic development agency. Kelly is leading a large project looking at how community organisations are leading the transition towards postcapitalist economies centring care.

In ending with research questions, we have approached research in a way that acknowledges and works in partnership with what is already happening. Rather than having to discover or even manufacture a gap in the literature to justify our research paper, we began and ended with a story of what is already there. For us, the justification for research is not whether there is a gap in the literature. The justification for research is rather that it increases the capacity of communities to put language around and share the value of what they are already doing and know is impactful. The gaps of interest are those vacant spaces in the city used to curate life and wellbeing.

References

Australian Research Council 2019, Engagement and impact assessment 2018–19 national report, https://dataportal.arc.gov.au/EI/NationalReport/2018/

Bennett, BW, Dann, J, Johnson, E & Reynolds, R (eds) 2014, Once in a lifetime: City-building after disaster in Christchurch, Freerange Press.

Bhattacherjee, A 2012, Social science research: Principles, methods and practices, University of South Florida.

Bowker, GC, Elyachar, J, Kornberger, M, Mennicken, A, Miller, P, Nucho, JR & Pollock, N 2019, ‘Introduction to thinking infrastructures’, in M Kornberger, GC Bowker, J Elyachar, A Mennicken, P Miller, JR Nucho & N Pollock (eds), Thinking infrastructures, vol. 62, Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0733-558X20190000062001

brown, am 2017, Emergent strategy: Shaping change, changing worlds, AK Press.

Callon, M & Rabeharisoa, V 2003, ‘Research “in the wild” and the shaping of new social identities’, Technology in Society, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-791X(03)00021-6

Cameron, J 1996, ‘Throwing a dishcloth into the works: Troubling theories of domestic labor’, Rethinking Marxism, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/08935699608685486

Cameron, J & Gibson, K 2020, ‘Action research for diverse economies’, in JK Gibson-Graham & K Dombroski (eds), The handbook of diverse economies, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, pp. 511– 19. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788119962.00070

Carlton, S & Vallance, S 2017, ‘The commons of the tragedy: Temporary use and social capital in Christchurch’s earthquake-damaged central city’, Social Forces, vol. 96, no. 2, pp. 831–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sox064

Chambers, R 1997, Whose reality counts?: Putting the first last, Intermediate Technology Publications. https://doi.org/10.3362/9781780440453.000

Chatterton, P, Dinerstein, AC, North, P & Pitts, FH 2019, Scaling up or deepening? Developing the radical potential of the SSE sector in a time of crisis, SSE Knowledge Hub for SDG, United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on the Social and Solidarity Economy (UNTFSSE), https://knowledgehub.unsse.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/62_North_Scaling-up-or-deepening_En-1.pdf

Cloke, P & Conradson, D 2018, ‘Transitional organisations, affective atmospheres and new forms of being-in-common: Post-disaster recovery in Christchurch, New Zealand’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 360–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12240

Cloke, P, Conradson, D, Pawson, E & Perkins, HC 2023, The post-earthquake city: Disaster and recovery in Christchurch, New Zealand, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429275562

Cretney, R 2018, ‘“An opportunity to hope and dream”: Disaster politics and the emergence of possibility through community-led recovery’, Antipode, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 497–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12431

Dombroski, K 2024, Caring for life: A postdevelopment politics of infant hygiene, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Dombroski, K, Diprose, G & Boles, I 2019, ‘Can the commons be temporary? The role of transitional commoning in post-quake Christchurch’, Local Environment, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 313–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2019.1567480

Dombroski, K, Diprose, G, Scobie, M & Yates, A 2023, Enabling life in vacant spaces: A partnership approach to evaluating holistic wellbeing in disaster recovery contexts, Report for Building Better Home, Towns and Cities, https://www.communityeconomies.org/publications/reports/enabling-life-vacant-spaces-partnership-approach-evaluating-holistic-wellbeing

Dombroski, K, Nicholson, H, Shiels, R, Watkinson, H & Yates, A 2022, Huritanga: 10 years of transformative place-making, Life in Vacant Spaces.

Durie, M 1999, ‘Te Pae Māhutonga: A model for Māori health promotion’, Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand Newsletter 49.

Gibson-Graham, JK, Cameron, J & Healy, S 2013, Take back the economy: An ethical guide for transforming our communities, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816676064.001.0001

Gilmore, S, Harding, N, Helin, J & Pullen, A 2019, ‘Writing differently’, Management Learning, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507618811027

Handforth, R & Taylor, CA 2016, ‘Doing academic writing differently: A feminist bricolage’, Gender and Education, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 627–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2015.1115470

Hayward, BM 2013, ‘Rethinking resilience: Reflections on the earthquakes in Christchurch, New Zealand, 2010 and 2011’, Ecology and Society, vol. 18, no. 4, p. 37. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05947-180437

Kitzinger, C 2004, ‘Feminist approaches’, in C Seale, G Gobo, JF Gubrium & D Silverman (eds), Qualitative research practice, Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848608191.d12

Latour, B 2004, ‘Why has critique run out of steam? From matters of fact to matters of concern’, Critical Inquiry, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 225–48. https://doi.org/10.1086/421123

Lykke, N, Brewster, A, Davis, K, Koobak, R, Lie, S & Petö, A 2014, ‘Editorial introduction’, in N Lykke (ed.), Writing academic texts differently: Intersectional feminist methodologies and the playful art of writing, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315818566

Mol, A 2008, The logic of care: Health and the problem of patient choice, Routledge.

Puig de la Bellacasa, M 2017, Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2753906700002096

Roelvink, G 2016, Building dignified worlds: Geographies of collective action, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816676170.001.0001

Scheyvens, H, Scheyvens, R & Murray, WE 2014, ‘Working with marginalised, vulnerable or privileged groups’, in R Scheyvens (ed.), Development fieldwork: A practical guide, 2nd edn, Sage, London, pp. 188–214. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473921801.n10

Tsing, AL 2005, Friction: An ethnography of global connection, Princeton University Press, New Jersey. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691263526

Tuhiwai Smith, L, 2012, Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples, 2nd edn, Zed Books, London.

Vallance, S, Dupuis, A, Thorns, D & Edwards, S 2017, ‘Temporary use and the onto-politics of “public” space’, Cities, vol. 70, pp. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.06.023

Yates, A, Pedersen Zari, M, Bloomfield, S, Burgess, A, Walker, C, Waghorn, K, Besen, P, Sargent, N & Palmer, F 2022, ‘A transformative architectural pedagogy and tool for a time of converging crises’, Urban Science, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7010001