Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 18, No. 2

July 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE (PEER REVIEWED)

Strengthening Research and Evaluation at the Community Level: A Case for Consideration, Collaboration and Care Within Mental Health

Sumedha Verma1, 2, Belinda Caldwell1, Susie Hansen1, Sarah Pollitt1, Vicki Hams1, Lauren Bruce1, Jane Miskovic-Wheatley2,*, Sarah Maguire2

1 Eating Disorders Victoria, Victoria, Australia

2 InsideOut Institute for Eating Disorders, Faculty of Medicine & Health, The University of Sydney, and Sydney Local Health District, New South Wales, Australia

Corresponding author: Jane Miskovic-Wheatley, jane.miskovic-wheatley@sydney.edu.au

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v18i2.9272

Article History: Received 02/08/2024; Revised 11/12/2024; Accepted 23/05/2025; Published 07/2025

Abstract

Much innovation happens at the community level. Community-based services, by virtue of their setting, have proximity to consumer experiences, perspectives and needs, and often spearhead advances in community care and advocacy. Thus, leveraging local knowledges and supporting their translation across research, clinical practice and policy is integral in enabling an equitable ecosystem to enhance community wellbeing. However, research and evaluation (R&E) capacity and capability within community settings remains limited, hindering such knowledge-sharing and change. This article details a community-based participatory research (CBPR) project involving an 18-month-long partnership between academic researchers and service providers at an Australian not-for-profit eating disorders organisation to build R&E. Collaboratively, we planned, co-designed and implemented monitoring, evaluation and learning practices into service delivery. This article shares: (1) the process of academic partnership within a community mental health context; (2) critical reflections on the complexities, strengths, challenges, and opportunities of engaging in CBPR in building capability/capacity; and (3) actionable recommendations to guide future efforts. We explain the need for a systemic approach to building R&E within the community sector and provide rich examples of CBPR in practice. Our learnings hold implications for how local knowledges are created, utilised and translated, and what will help moving forward to enhance community care.

Keywords

Community-Based Participatory Research; Community-Academic Partnership; Mental Health; Eating Disorders; Co-Design; Capacity Building; Monitoring Evaluation and Learning

Introduction

Community is a central source of knowledge. Much, if not most, innovation in how we conceptualise social issues, such as mental health, and how best to address them, comes from voices of those they directly affect – the community. Across the mental health sector, lived experience and peer work is being increasingly embedded into research and service delivery in attempts to empower community voices (Musić et al. 2021; Utpala et al. 2023) and enhance health outcomes (NEDC 2019; Engage Victoria 2023). Community-based organisations increasingly co-design and offer peer-led services (Farrar-Rabbidge & Squire 2022), which leads to the ground-up creation of local knowledges from the community, often by the community. Working at the granular, grassroots level community services serve as the gateway to important information (for example, consumer demographics, engagement, program/service evaluation outcomes) in naturalistic environments, which can be leveraged to advance mental health conceptualisation and care. This uniquely positions community-based services as powerful advocates and agents of change.

It is therefore essential that such knowledges be appropriately captured at the community level. To enable the reciprocal flow of information across community-based services, research, policy, and clinical practice, a multi-level ecosystem of robust research and evaluation (R&E) is required (see Figure 1; Ayton et al. 2024; Lloyd et al. 2021). Specifically, this would enable: (1) lived/living experience voices to be supported (for example, through advocacy/funding efforts, guiding organisational values, processes and directions); (2) gaps and areas of need to be identified and addressed to better meet diverse community needs (for example, identification of under-serviced and marginalised populations); (3) existing community programs and innovations to be evaluated (for example, for safety, effectiveness and efficiency) and translated, contributing to the development of future innovations; and (4) the notable gap between research and clinical practice to be reduced (Robinson et al. 2020).

Figure 1. Ecosystem of equitable and responsive knowledge-sharing within healthcare, centring lived experience community voices at the core

For systems in which lived and living experience is a central facet of service delivery, the importance of R&E becomes even more pronounced. Supporting services to identify and address issues that directly affect community members is needed to aid advocacy and decision-making (Reed 2015), lead to better understandings (Guijt 2014) and enable community knowledge ownership (April et al. 2023; Israel et al. 2012). Additionally, if services are to be for the community and by the community, they then must be resourced to account and advocate for diverse community perspectives (Jones et al. 2021) to reduce further marginalisation and epistemic injustices (Mooney et al. 2023) that see important knowledges neglected.

However, within a context of chronic under-investment, R&E practices within community-based organisations remain under-prioritised, which limits pathways of knowledge-sharing that remain either fragmented or entirely absent. For example, the costs required to support effective R&E often exceed allocated funding, resulting in a lack of organisational capability and R&E infrastructure. This creates a vicious cycle: under-resourcing prevents the ability of community services to secure funding to establish R&E systems and demonstrate their impact, which in turn stalls knowledge generation and translation across the sector. As a result, service improvements are delayed, and overall community outcomes remain constrained. Supporting community organisations to undertake robust R&E is therefore essential – not only to ensure the safety of community members (Stewart 2014) but to amplify diverse lived experience perspectives, enhance knowledge translation, and effect meaningful social change (Guijt 2014; Reed 2015).

This issue is particularly critical for under-prioritised and highly stigmatised conditions such as eating disorders. These complex conditions have rising prevalence (Hay et al. 2023) and far-reaching impacts, not only on individuals (Miskovic-Wheatley et al. 2023) but their families and kin (Fletcher et al. 2021), as well as broader systems and structures (Ágh et al. 2016). Despite the increasing social and financial costs (Butterfly Foundation 2024), funding for eating disorders research remains disproportionately limited compared to other mental health conditions (APPG 2021; Bryant et al. 2023). Additionally, dominant conceptualisations and treatment frameworks often lack diversity and cultural responsiveness (Clark et al. 2023). The persistent under-prioritisation and ‘structural exclusion’ of eating disorders at large (Bryant et al. 2023), coupled with the marginalisation of diverse perspectives (Asaria 2025; Verma 2024) underscore the urgent need to strengthen eating disorder research, policy and care (Ayton et al. 2024; InsideOut Institute 2021; NEDC 2023).

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a broad framework in which researchers and community stakeholders collaborate to identify and address issues faced by the community (Wallerstein & Duran 2006). CBPR attempts to redress power imbalances by actively involving community partners in shared decision-making and research practices alongside academic partners. In this way, both community and academic partners contribute to the research process, sharing their unique expertise to learn from one another, create new knowledge and effect social change (Israel et al. 2018; Wilson 2019). Sanchez et al. (2023, p. 989) explain this further and call for systemic investment in ground-up, community-based initiatives:

Community-engaged work requires authentic relationship building, takes time, and does not fit the traditional research infrastructure that prioritizes proliferation of products (e.g. publications and grants) over transformation of mental health systems and clinical practices.

The benefits of CBPR are in its democratic approach, which not only captures community perspectives that may have previously been excluded from traditional research practices but centres them at the core of decision-making to better address community needs, simultaneously building knowledge and skills of all involved partners (Case et al. 2014; Guijt 2014).

One way of engaging in CBPR is through partnership between academics and community stakeholders (April et al. 2023; Morton et al. 2014), which has been utilised to enhance R&E within community services (Golenko et al. 2012). The expected benefits of community-academic partnerships specifically within the mental health sector are manifold; they may: (1) support community services to develop, maintain and own R&E systems of their own; (2) provide reprieve to capacity demands by offering academic assistance; and importantly, (3) enable knowledge-sharing between community services and research settings to promote advocacy and change. The collaborative nature of this approach appears appropriate within the eating disorder sector in which lived experience is becoming increasingly commonplace within service delivery (Utpala et al. 2023), and considering the need for greater research and diversity in conceptualisations and care (Bryant et al. 2023).

In the current article, we share the experiences, reflections and recommendations as a group of community service providers and academic partners in co-designing and undertaking R&E practices within an Australian community mental health organisation through a partnership spanning 18 months. By sharing the enablers, strengths, challenges, and opportunities of undertaking this work, we present widespread considerations that impact R&E more broadly within the mental health sector to guide future advances. Our work extends previous community-engaged research methodologies (April et al. 2023; Reed 2015) and guidelines (Sadler et al. 2012), simultaneously addressing the need for greater descriptions of community-academic co-design processes (Benz et al. 2024).

Academic-community partnership

Context and backstory

The current CBPR project stemmed from a larger, four-year government-funded project led by author Maguire to enhance multilevel eating disorder research and translation across Australia. This was called the Mainstream project (www.mainstreamresearch.org.au) and began in 2020 at the InsideOut Institute for Eating Disorders (IOI), which is a collaboration between the University of Sydney and Sydney Local Health District. We have previously published a comprehensive project protocol (Verma et al. 2024).

This project funded a full-time postdoctoral researcher (author Verma) to be embedded and work ‘on the ground’ for 18 months at Eating Disorders Victoria (EDV), a community eating disorders organisation based in Melbourne, Australia (www.eatingdisorders.org.au). Alongside advocacy, EDV offers support for community members through clinical services (that is, telehealth counselling and nursing consultations), psychoeducational resources (for example, online courses and information), various psychosocial support groups and programs (Raspovic et al. 2024), and linkage to external services. Many staff bring some form of connection to the cause, either direct caregiving lived experience, and many programs are co-designed with or led by lived experience peers (EDV 2023).

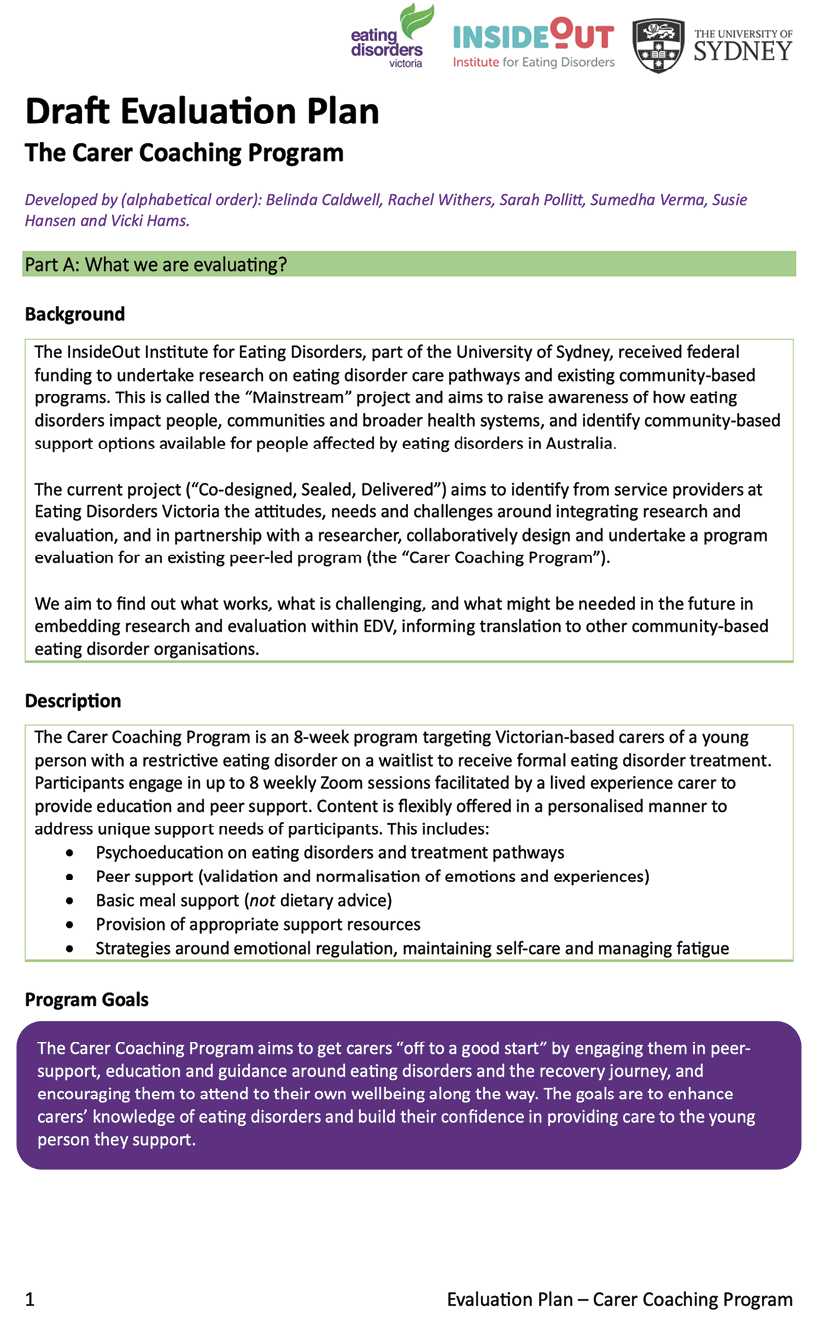

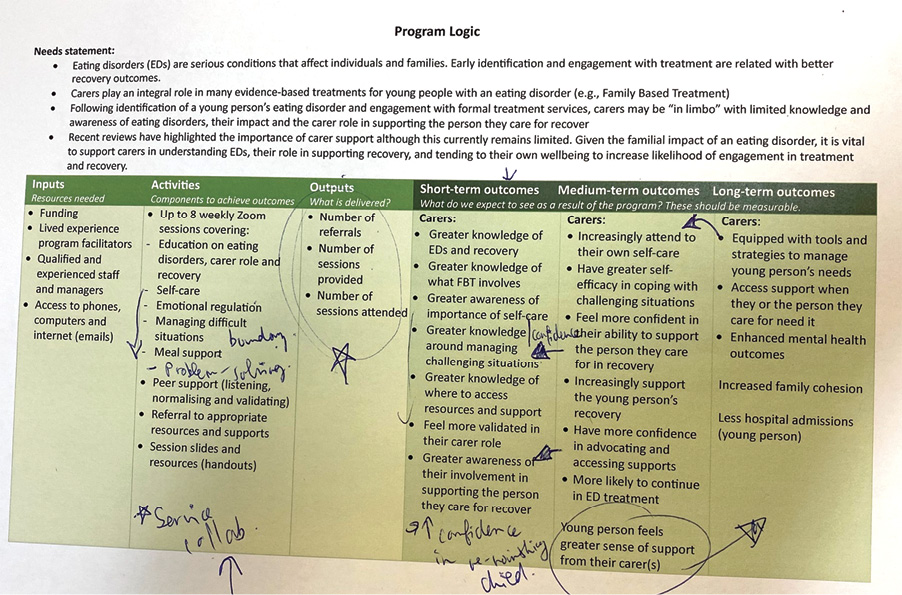

As a not-for-profit service that is almost entirely funded (approximately 90 per cent) by the Victorian State Government, historically no funding has been specifically allocated to R&E, resulting in limited R&E practices. As detailed in the protocol, originally our project planned to co-design and implement R&E practices at EDV through academic partnership to enable the evaluation of an existing early intervention program for carers of a young person with an eating disorder. This program (Carer Coaching Program) was developed, and is facilitated by, trained lived experience peer workers (Carer Coaches) in response to long wait times consumers and families often experience in accessing eating disorder care within healthcare settings.

Co-design working group

The core working group consisted of author Verma as the primary research partner embedded at EDV, and several EDV staff members (community partners) involved in design and/or delivery of the Carer Coaching Program (that is, two lived experience program providers, two managers, the CEO, one program director), who all provided informed consent. One member in the working group had a personal history of an eating disorder, and three members had lived experience of caring for a person with an eating disorder. Author Verma received high-level research guidance from authors Miskovic-Wheatley and Maguire (IOI, University of Sydney), who also contributed to project decision-making. Additionally, she received internal supervisory support from author Bruce (EDV), given the novelty and embedded nature of their role. Table 1 outlines the roles of all partners.

Note: Green shading indicates research partners, orange indicates community partners. IOI = InsideOut Institute for Eating Disorders. EDV = Eating Disorders Victoria.

Personal accounts

In Appendix 1, we have included several reflexive accounts from community and research partners to provide rich, multi-level perspectives and experiences of our project. These are referred to in the following sections but we strongly encourage readers to read our personal reflections for richer and deeper insights.

Co-design process

As detailed in the protocol (Verma et al. 2024) and author Verma’s account, we took a bottom-up, empowered approach to building R&E through academic partnership (BetterEvaluation 2021). Author Verma facilitated all meetings, which were designed to be collaborative in nature; community partners were encouraged to lead decision-making in line with best-practice community-engaged ways of working (Reed 2015). To track project process and the outcomes of building R&E practices, author Verma collected data longitudinally from the whole authoring team through meetings (audio recordings), semi-structured interviews, two formal questionnaires (baseline and mid-way), written correspondence (via emails, online chats) and comprehensive field notes that included key events and decisions, observations and personal reflections.

Over the course of 12 months, we held 75 meetings (a mix of one-on-one and group meetings, approximately 54.5 hours). To develop her capabilities in CBPR and program evaluation, and for background, author Verma sought ad hoc external consultation throughout the course of the project (27 sessions, approximately 30 hours) with a diverse range of professionals working within various fields such as eating disorders, program/service evaluation, cultural diversity, implementation science, editing and publishing, data management and ethics. Reflections were documented in her field notes. Author Verma engaged in 47 supervision sessions (approximately 42 hours), the majority with author Bruce (based at EDV).

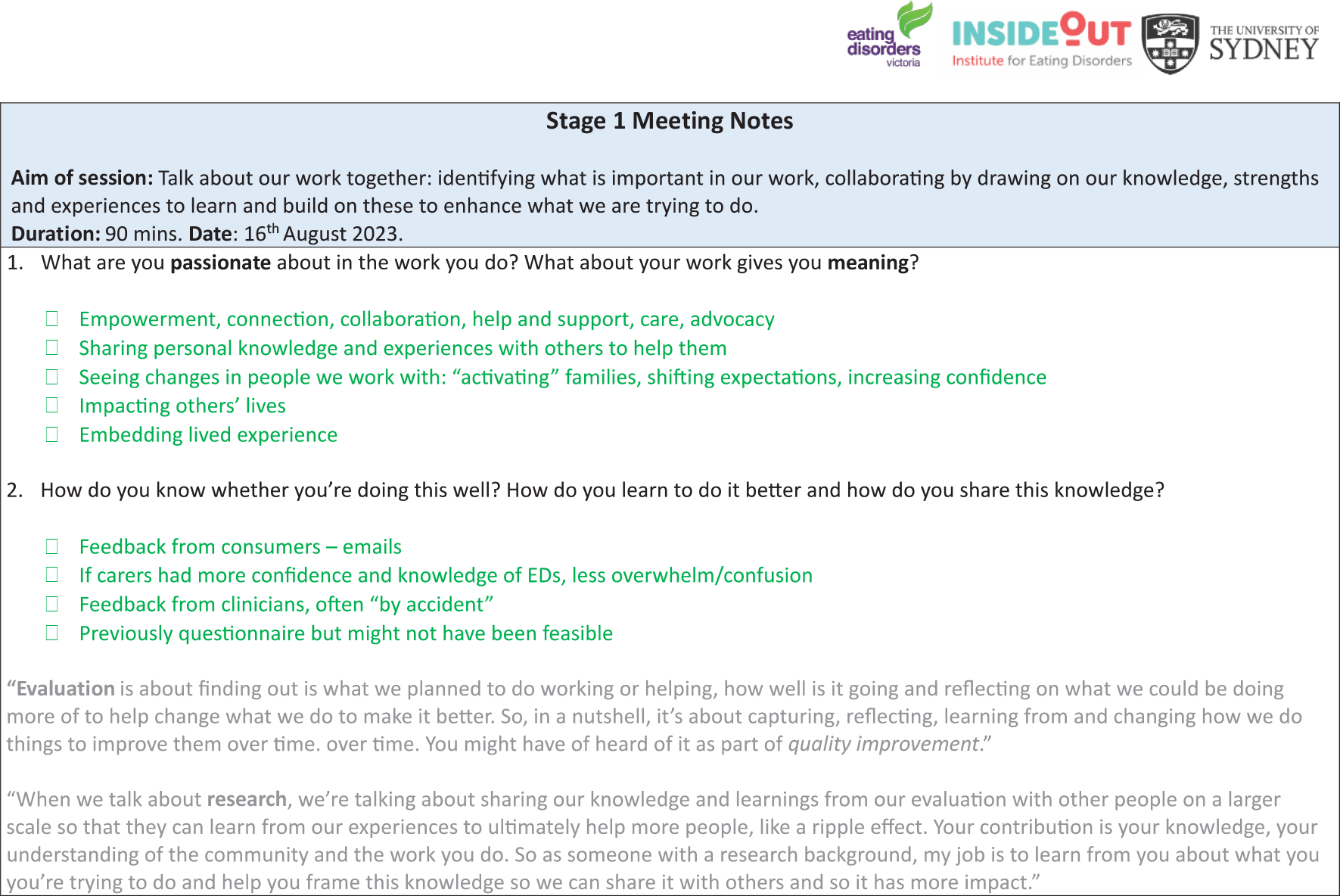

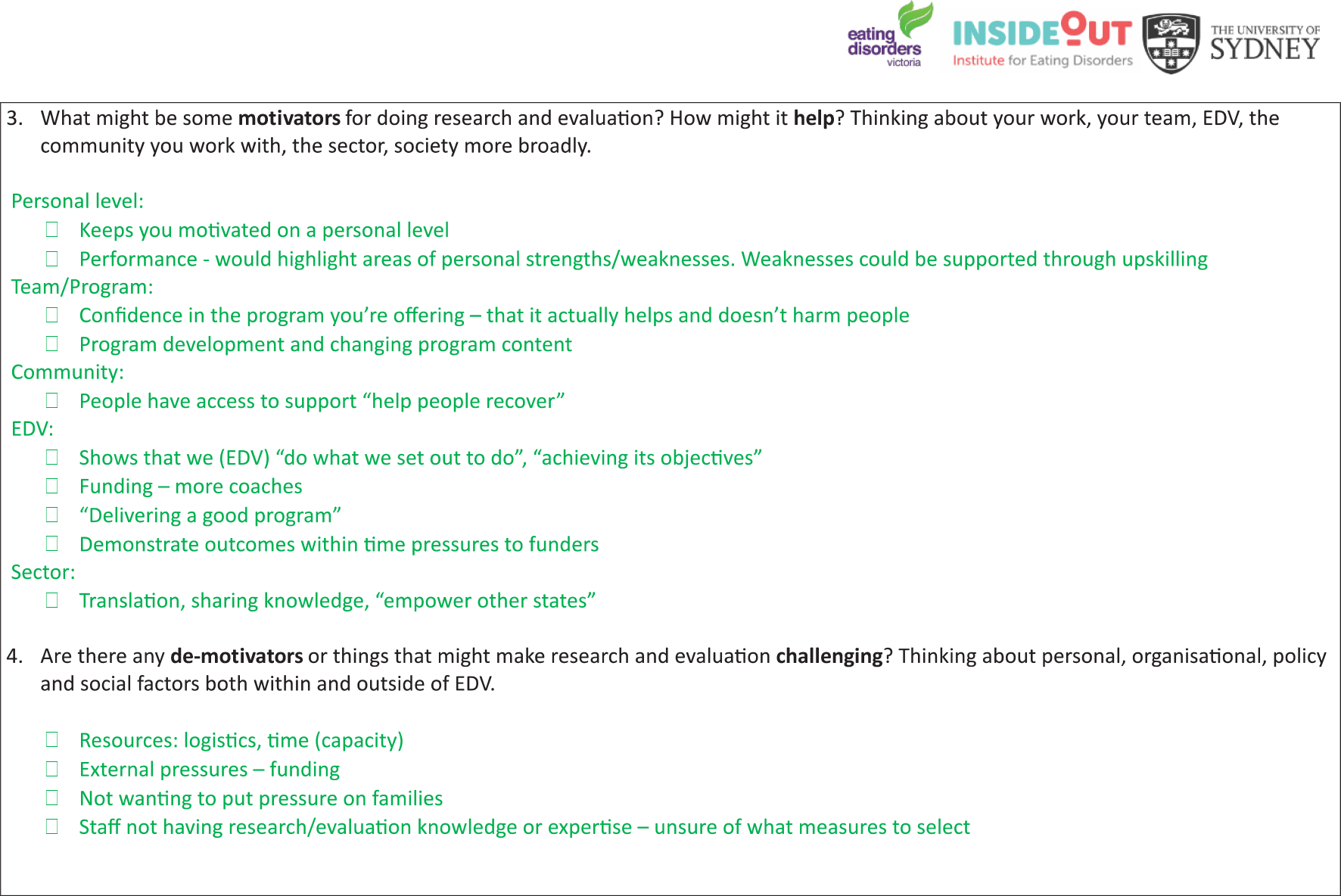

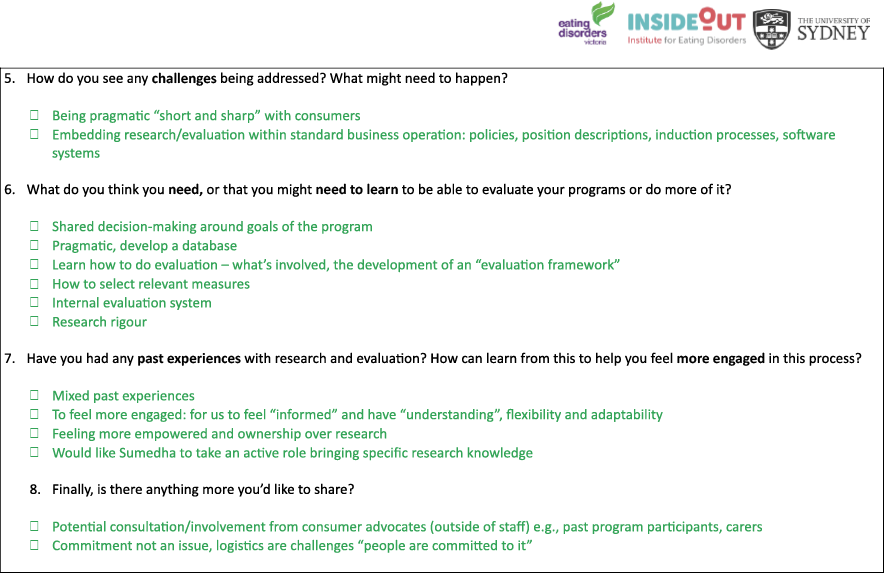

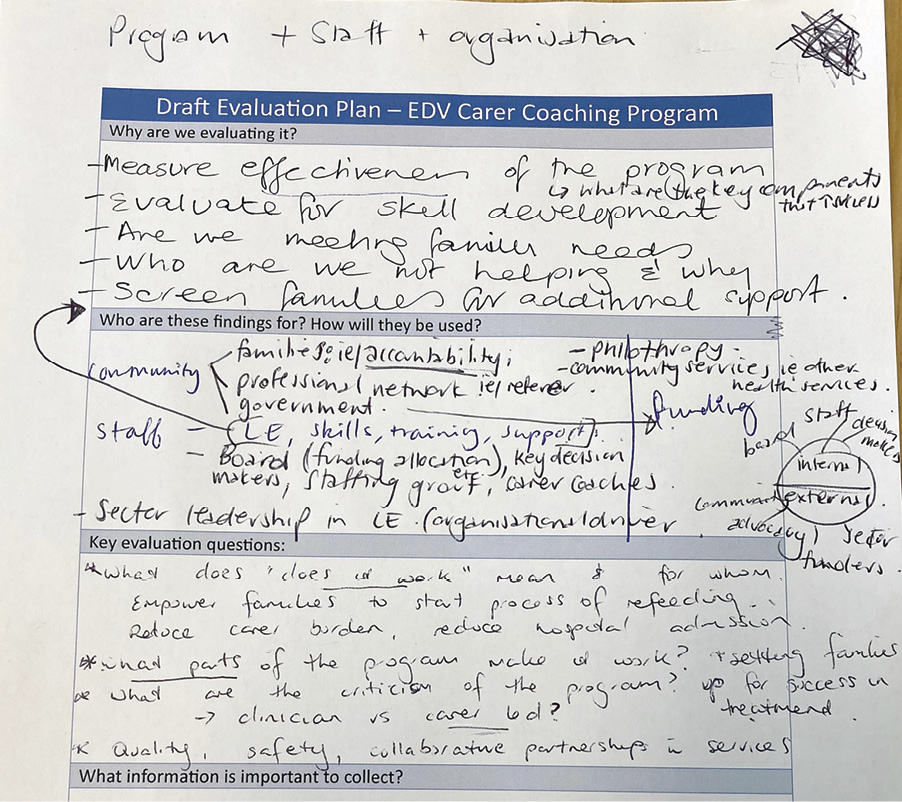

Initially, the working group held three 90-minute in-person meetings (August to September 2023) at EDV to: (1) identify prior staff experiences, attitudes, needs, and anticipated challenges of integrating R&E within service delivery; and (2) begin co-designing R&E processes, practices, and materials for the Carer Coaching Program (for example. evaluation questions, needs statement, program logic). We established an online group chat channel to regularly communicate, stay updated, and share ideas and documents. Sample research materials are provided in Appendices 2 to 4 (for example, meeting notes, draft evaluation plan, program logic).

Early pressures, pushes and pivots

As we aimed to build and embed research practices at EDV, we sought ethics approval through the University of Sydney’s ethics committee, leveraging IOI’s affiliation to avoid application costs. Early on, we faced a key challenge: how to sustain an academic partnership once project funding had lapsed. Since research required ethics approval, which in our case depended on academic affiliation, we had two options – either proceed with the University of Sydney’s ethics process without a guaranteed long-term academic partner or seek approval through an independent ethics committee, which would cost several thousand Australian dollars. We ultimately chose the former, allowing us to pilot an evaluation of the Carer Coaching Program within the current project. However, this decision required us to work within a tight timeframe, making rapid decisions and developing research materials to meet ethics deadlines.

To navigate these early challenges, we were required to think strategically and act fast. This, however, seemed to pressurise and strain working relationships. As author Hansen reflects, ‘If there is one take away from this, it’s spending more time planning and establishing the group norms rather than launching into the depths of doing.’ Following initial planning meetings, author Verma prepared drafts of explanatory statements, consent forms and questionnaires for the ethics application, which she circulated to the working group. However, it soon became clear that ‘clearer consideration and planning’ (author Pollitt) was needed to define roles, clarify expectations and lay the groundwork for decision-making and effective collaboration (also see author Hansen reflection). More structured planning could have prevented community partners from feeling pressured to make decisions and, importantly, could have mitigated author Verma’s feelings of isolation and frustration (see reflection). A proactive approach could be to formulate group guidelines from the outset, outlining collaborative goals, responsibilities and a clear strategy for addressing how to ‘respond when is something is not going to plan’ (author Hansen).

During the ethics application process, we realised that adapting the Carer Coaching Program’s inherently flexible and personalised delivery to meet requirements set by the ethics committee would take greater time than anticipated, a challenge noted by other groups (Benz et al. 2024). Key decisions around the language and length of explanatory statements and consent form (‘I was very conscious of protecting carers from additional burden’: author Hams account), questionnaire content and use of technology for data collection required further time. While ethics approval was likely achievable, the extended process would have significantly reduced the time available to evaluate the Carer Coaching Program, which we had set out to do.

Through a joint decision by the authoring team, we collectively decided not to continue in pursuing ethics approval given our limited timeframe and objectives. Instead, we pivoted toward monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) practices. We believed this approach would fast-track data collection for evaluating the Carer Coaching Program within the project’s timeframe, as it did not require formal ethics approval (this would be classed as ‘quality improvement’). An alternative would have been to make EDV partners affiliates of the University of Sydney, but this process would have been time-intensive and required capability-building for EDV staff to navigate new systems. Not pursuing ethics approval had the drawback of limiting the use of collected data for research purposes. However, it also alleviated pressure on community partners to meet tight deadlines and helped reduce tensions in the working relationship, as discussed later.

To build MEL practices, community partners proposed holding regular 30-minute meetings each fortnight, which we did across several months (mostly attended by authors Verma, Hansen, Pollitt, and Bruce). This afforded us greater time to co-design and review MEL processes and practices (for example, MEL plan, automated consent and screening procedures within existing pathways of help seeking, questionnaires for Carer Coaching Program participants) and attempt to integrate these into service delivery (for example, implementation into software systems). Importantly, during this co-design process, community partners in senior leadership roles opted to build a holistic MEL framework to be implemented across the entire organisation for long-term impact and sustainability. A key motivation behind this was to minimise any unnecessary burden placed on consumers to complete multiple forms and documents along their help-seeking journey (see author Hams account). This inevitably expanded the scope of the project as originally outlined in the protocol, which we reflect upon later.

Ultimately, we co-designed, reviewed, and adapted processes and materials that have been implemented into EDV’s service delivery including:

1. An organisation-wide ‘Engagement Agreement’ outlining EDV’s responsibilities and details of MEL practices for community members to consent to prior to engaging;

2. A standardised registration form for all consumers to capture essential demographic data;

3. Specific MEL practices for the Carer Coaching Program, including baseline and evaluation questionnaires for participants; and

4. A comprehensive R&E training resource to upskill staff within the organisation including specific guidance (for example, evaluative thinking, logic modelling, data collection, meaning-making, navigating ethics). This includes direction to further resources such as evaluation guides (Milstein & Wetterhall 1999; NSW Treasury 2023) and additional training.

Methodology

In synthesising learnings and outcomes of the current project, we were guided by past literature on longitudinal qualitative design (see Calman, Brunton & Molassiotis 2013). First, author Verma began by examining the chronology of the project, documenting key events and their outcomes, moments of tension, and influential contextual factors (for example, staffing changes, conferences, concomitant projects). She then engaged in narrative analysis (Parcell & Baker 2017) and reflexive methodologies (Olmos-Vega et al. 2023) in reviewing meeting and interview transcripts and notes, personal accounts, field notes and responses to questionnaires completed by community partners at the beginning (August 2023) and midpoint of the project (March 2024).

Using a mix of inductive and deductive approaches, author Verma identified and categorised common themes (for example, ‘feasibility’, ‘capacity/capability’, ‘sustainability’), before interpreting their meaning. Additionally, she consulted with five external advisors – four program evaluation and implementation researchers and one cultural diversity and service development consultant (approximately four and a half hours) – who supported the interpretation process. She compiled a document that outlining key events, strengths, barriers, learnings and recommendations, which was circulated to the team for iterative review. To achieve our collective standpoints and recommendations, the authoring team engaged in 11 reflective meetings (approximately nine hours, variety of group and one-to-one), including a 90-minute workshop to intensively edit the current article.

Reflections and recommendations

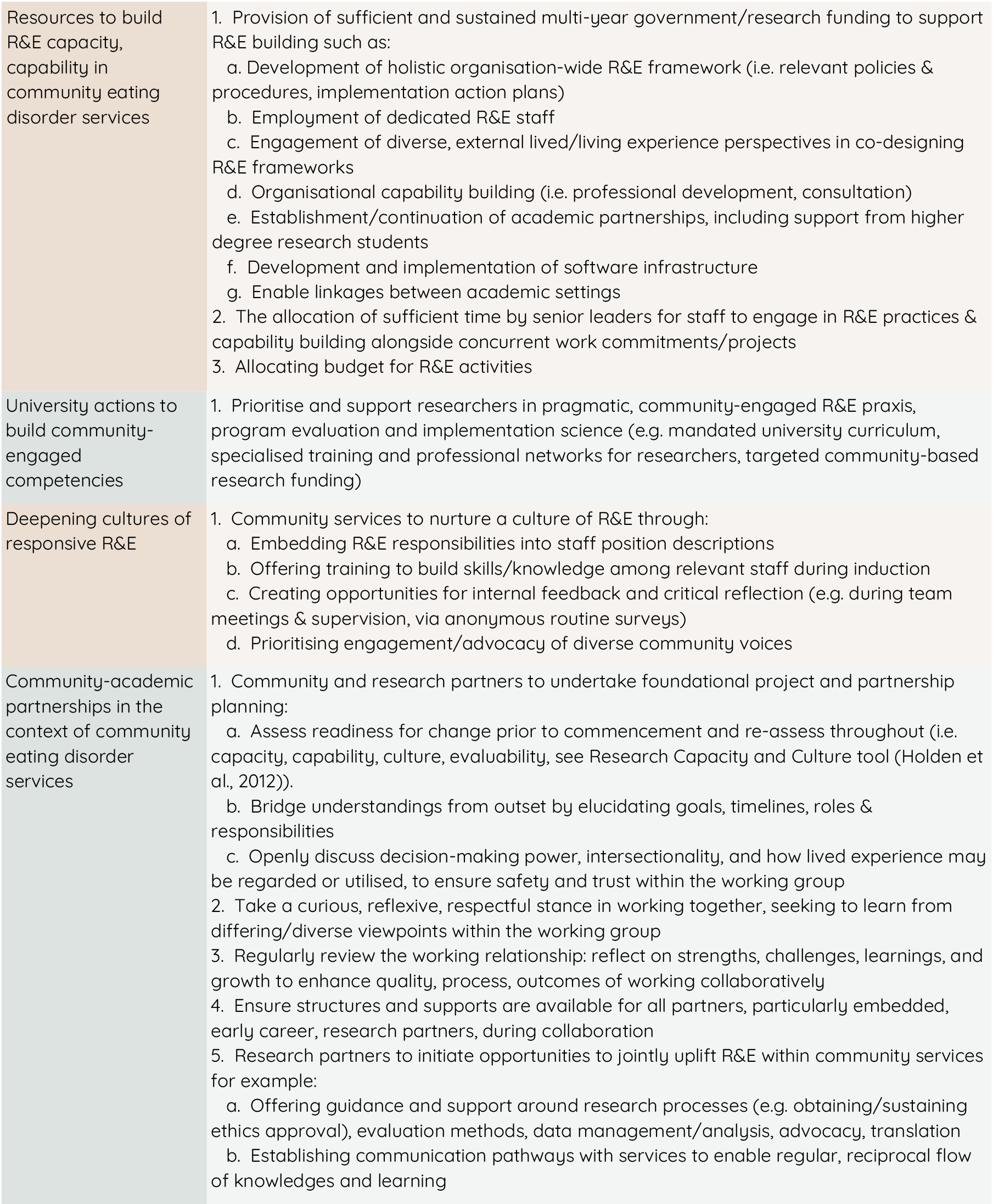

Below, we share our reflections and recommendations around co-designing and undertaking R&E within a community eating disorder context through academic partnership. Figure 3 provides a summary with actionable recommendations.

Figure 2. Critical and courageous conversation prompts for community-academic partnership

Figure 3. Recommendations for uplifting research and evaluation within community eating disorder services

Need for change and growth is restricted: Systemic factors that stifle change

Throughout our project, there was a strong expressed need and motivation to strengthen R&E at EDV to improve community, organisational and broader systemic outcomes (see author Hansen and Hams accounts). Several ideas of implementing R&E were suggested by the working group, echoing what has been extensively outlined in previous work (Stewart 2014). These included the development of a holistic R&E framework within EDV, including policies and procedures, and actionable plans for implementation (for example, embedding into position descriptions and allocating time for capability building). We additionally identified specific ways that research partners could assist uplifting R&E within community services, including providing research-related guidance, assisting in advocacy and funding efforts, and facilitating internships of research students at EDV.

The following factors were identified:

1. Capacity constraints: Despite a strong endorsement for build R&E culture and praxis, our project revealed significant capacity constraints. Most EDV partners were employed on a part-time basis due to funding limitations, and contextual factors such as concurrent work commitments, pre-existing projects and organisational/staffing changes (including resignation of one Carer Coach) ultimately hindered capacity for community partners to engage fully in the current project (see author Pollitt account). At the same time, the availability of senior supervisory and managerial academic oversight was limited as senior research partners were consistently required to attend to multiple projects at IOI, which had been under increased pressure due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, there was no funding to support consumer involvement during establishment of these new processes, which would have been beneficial (Case et al. 2014).

2. ‘Catch-22’ situation: Limited funding, particularly for eating disorders, alongside pressures to produce outcomes seems to create a Catch-22 situation. The scarcity of both funding and time perpetuates cultures of rapidity and urgency. This in turn affects the capacity to collaborate in building R&E cultures, which subsequently reduces the ability to secure future funding, translate outcomes and address community needs. Author Miskovic-Wheatley writes, ‘When research or evaluation funding is available, it is usually minimal, perhaps covering only a part-time position. This scenario creates a paradox: early-career researchers may be hired for these roles but often lack the experience, support, and resources to effectively lead and facilitate projects independently.’ This, alongside the persistent underfunding of research, seems emblematic of a broader systemic inequity in how eating disorders are conceptualised, prioritised and invested in within a dominant Western socio-political climate (Bryant et al. 2023).

3. Systemic investment: Collaboration and transformative efforts require careful consideration, nuance and time, and are dependent upon sufficient resourcing (Sanchez et al. 2023). The chronic restriction of available resources reflects a significant systemic barrier to this much-needed work. Author Maguire writes community-based programs: ‘are often at the forefront of thinking and advancement. Yet, because there is a lack of funding for their evaluation and publication, they do not have the impact on patient care that would benefit all’. Author Miskovic-Wheatley also comments on the notable cultural mismatch between academic institutions and community services. Therefore, adequate systemic investment and time are essential to properly prioritise and undertake collaborative efforts in building R&E infrastructure – a challenge in the current under-resourced climate. In our project, a longer overall duration of at least two, ideally three years, would have afforded greater opportunities for us to strategically plan and implement R&E processes without forgoing trust and relationship building that is integral to this type of community-engaged work. We recommend future projects strive for these durations. As author Maguire writes: ‘The work is worth doing certainly but it is worth ensuring that it has a life ongoing’.

Capability within the research workforce

Besides capacity, capability also presented an issue. Our academic team, while extensively experienced in participatory methodologies such as co-design, held limited expertise in community-engaged evaluation and implementation science. Looking back, formal assessments of readiness, culture, capacity, capability and evaluability (Golenko et al. 2012; Holden et al. 2012; Stewart 2014) prior to project commencement would have been integral in providing a comprehensive snapshot of existing resources, capabilities, and demands to determine feasible and realistic steps to uplift R&E considering current circumstances.

In the early stages of the project, author Verma rapidly undertook self-directed professional development and sought consultation with external evaluation advisors around community-engaged program evaluation and implementation to plan and undertake this project. Author Verma writes: ‘Collectively, this self-education and constellation of new connections provided me with great support and ultimately sharpened my thinking and doing. However, this at times was a confusing and lonesome experience ...’. While rapid self-directed learning created immersive, learning-on-the-go opportunities and professional networks for author Verma to gain and share knowledges, important aspects of project planning and processes were inevitably overlooked due to limited prior targeted knowledges within the available academic team, which contributed to author Verma’s feelings of being under-supported.

This speaks to the great need to ‘invest in systems and structures that support community-driven work’ (Sanchez et al. 2023, p. 989) and reduce the structural perpetuation and proliferation of exclusionary and problematic research practices (Emmons et al. 2022; Sanchez et al. 2023). Embedding pragmatic and participatory methodologies into university curriculum, making available community-engaged research funding and greater establishment and exposure of professional researcher networks may be ways to build academic workforce capability for more equitable R&E. Author Miskovic-Wheatley expresses the benefits of this: ‘Establishing and maintaining networks beyond individual projects could reduce resource wastage, enhance expertise, and increase the potential for collaborative grant applications, long-term research outcomes, and cross-organisational connections’.

Community-academic partnership: working with and through differences

As author Verma reflects: ‘Attention, consideration, and connection is necessary to manage the complicated and challenging nature of this transformative, systems-level work’. While readiness and resources are necessary to make space for collaboration and change, a mutual understanding or ‘bridging’ (Powell & Menendian 2024) is important for partners to move and learn together. As author Miskovic-Wheatley expresses: ‘Effective stakeholder management requires open communication, positive debate, and clear decision-making to ensure project delivery and researcher support’. Establishing and maintaining our community-academic partnership of diverse stakeholders within the context of limited time and resources required us to have constant and open communication in navigating changes along the way. Looking back, we needed to ensure sufficient time at the beginning of the partnership to: (1) reach a ‘shared vision’ of project goals and timelines (author Hansen account); (2) elucidate the role and responsibilities of partners/working group; and (3) establish respectful ways of working together as a collective (as described by Sadler et al. 2012). Our limited project timeframe plunged us into action to quickly produce outcomes, forgoing vital opportunities for us to undertake this foundational relationship-building work. ‘Slowing down’, as author Pollitt reflects, was a key learning, particularly when attempting to effect change within an already-stretched environment.

Decision-making power and intersectionality

Israel et al. (2018, p. 36) explain that one of the most crucial principles in community-based research is ‘shared control in decision making’. We faced significant challenges in this, specifically elucidating who makes decisions, and when they are made. Author Caldwell reflects on this in her account: ‘A critical issue that emerged was the distribution of power. Ambiguity in this area at the project’s outset created ongoing challenges’. Our partnership comprised people from diverse personal (that is, ages, races, cultures) and professional backgrounds (that is, peer workers, clinicians, managers, senior academics, an early career researcher) which inevitably impacted the location of power, what and how decisions were made, and the practical and emotional impacts of decision-making processes (see authors Verma, Caldwell and Hams accounts). Author Verma reflects: ‘This requires listening, learning and committed action’.

Sanchez et al. (2023) provide a seminal analysis and recommendations on dismantling power within community mental health research towards greater equity and responsiveness. Prioritising ‘courageous conversations’ (Singleton 2013) to critically discuss power and how to share it, along with positionality, for example, our ontological and epistemological orientations (Holmes 2020) and intersectionality would have been instrumental for us to better understand how ‘racism, classism, sexism, and other ‘isms’ operate to delegitimise community knowledge’ (Israel et al. 2018, p. 35). Prioritising these foundational conversations in future work would provide reflective spaces to identify emerging power dynamics and share personal/collective experiences, while problem-solving how to better work together considering diverse, and at times conflictual, viewpoints and (lived) experiences. Munshi et al. (2020) extend this, writing that in the context of health policy and systems research: ‘We need to understand the parameters in which we operate and think and recognise how they are informed by our lived experiences and positionality’.

Author Hams reflects on feeling uncomfortable in voicing her opinion at points. This could have been ameliorated by the entire working group reflexively identifying their own positionality and making space for those who ‘hold their own lived experiences and who strongly advocate for the needs of lived experience communities’ (author Hams). Importantly, lived experience is neither static nor unifying and does not make one immune to issues of privilege and power. Developing a shared understanding of how lived experience is regarded, weighted or utilised, within service delivery and collaborative partnership, and how this may intersect with power is therefore integral alongside careful de-construction of structural inequities in research and the healthcare sector (Sanchez et al. 2023). This is particularly important when partners bring their own lived experience to their work, and/or work within a predominantly lived experience setting such as EDV. To ensure a sustainable and well workforce, safety and trust are integral to maintain (author Verma’s reflection). This is of particular importance within the context of eating disorders work given how discursive these conditions seem to be (LaMarre et al. 2022).

Making critical dialogue commonplace is essential in partnership and in building R&E cultures/praxis. Specifically, we encourage future community and research partners consider the following questions during planning and engagement, which build on existing literature (April et al. 2023; Israel et al. 2018; Sadler et al. 2012).

Compassion and commitment

Showing compassion and understanding about each other’s perspectives, roles and experiences were crucial in ameliorating some of the challenges of working together (‘connection was, and is, the key to everything’: author Verma account). In future collaborative projects reinforcing past efforts (Reed 2015), it is imperative that partners take a curious, reflexive, and respectful stance by actively listening to one another and seeking to learn from each other’s perspectives, given the diverse lived/living experiences and expertise of all involved. In our project, courageous conversations were fundamental in bridging understandings and rupturing repairs while experientially modelling reflexivity, and evaluation and learning practices. An example of this was when author Verma communicated her discomfort, frustration and sense of misjudgement to EDV partners. This created an opportunity for understanding, leading to improvements in role clarity, consensus on deadlines, and enhanced communication moving forward. Through advocacy, author Verma positioned herself as an active part of the research process, and unimmune to disempowerment. This in turn sharpened her insights into how community-engaged processes impact the researcher as well as her recommendations for keeping all parties safe during CBPR, which she later reflected on (publication under review) and presented at an international conference. Ensuring structured opportunities for such collaborative problem-solving can foster a reflexive and responsive culture.

Despite the challenges encountered during our partnership, there were significant strengths in our shared commitment, persistence and adaptability (‘[w]e are deeply committed to continuing to embed what we have learnt over the last year’: author Caldwell, ‘I don’t see this as a negative but a sign of progress and maturity of EDV’: author Hansen). We maintained a commitment to attend meetings, share decision-making, navigate challenges, model continuous self- and collective reflection, and negotiate tensions and conflicts as they arose in the context of contextual changes. We endeavoured to be flexible, dynamic and move together; this required and demonstrated individual and collective resilience. Despite the challenges, author Verma ends on an honest yet hopeful note: ‘We, of course have a long way to go, and we can only get there if we move together’.

The decision to format the current article as a collaborative piece with personal and collective, reflexive accounts, for example, highlights the commitment of our team to walking and working side-by-side, creating and sharing knowledge collaboratively rather than a top-down manner. This represents a notable benefit of CBPR in that learning is reciprocal, and we grow together (Guijt 2014; Reed 2015). Identifying and celebrating the successes and growth as a working group were essential in enhancing motivation, meaning and mutual care within our partnership, which may be facilitated in future work by formal ‘group reflection’ opportunities during projects. Continually reviewing the process and quality of working together gave us a greater sense of trust and containment and connection. Making open, courageous conversations the norm would provide inclusive space for working group members to voice their experiences and feel validated by one another, which enhanced partnership outcomes (see author Hansen account).

Structures and supports

It is important for all partners to have structures and support during their engagement in novel projects or initiatives like ours (‘scaffolding and supports are crucial’: author Verma). This may include formal supervisory or managerial support, and the option to provide feedback and raise any concerns around project processes and practices. Structurally, there was confusion in reporting lines for the embedded research partner role, most probably due to the novelty of this collaborative work for both IOI and EDV. As the embedded research partner, author Verma received managerial and supervisory support from authors Miskovic-Wheatley and Maguire (IOI), and author Bruce (EDV). Author Pollitt observed that these multiple reporting lines ‘led to challenges in connection and relationship of the researcher to parts of the project team and confusion in project direction, role responsibilities, and decision making’.

In her account, author Miskovic-Wheatley notes community-based R&E roles often involve early career researchers due to funding constraints, providing several suggestions for ensuring holistic researcher support including: access to university resources, mentoring and supervision, professional development, expert consultation, financial support, and guidance around statistical analysis. She adds: ‘Early career researchers, with their enthusiasm and creativity, are vital to these projects. However, their work must be meaningfully and reliably supported by broader research and translation networks’. We collectively believe that clear position descriptions, terms of reference and codes of conduct could provide better structure in work roles in this type of collaborative work. This is particularly important for emerging researchers who have great potential to championing innovation and systemic change yet remain consistently under-supported (Kent et al. 2022).

In our project, professional supervision and external consultations provided valuable opportunities for author Verma to express experiences of working pragmatically and on the ground, critically reflect, build capability, and develop her academic acumen (see account). Importantly, peer supports at EDV and IOI provided a sense of connection, kinship, inclusivity and support, providing some buffer against the isolation due to the embedded and autonomous nature of her role, which boosted empowerment, innovation and advocacy: ‘The community of colleagues/friends I have found in my experience catapulted me into taking up space, using my voice, respecting my power and advocating for change that is needed in the world’. To further support embedded researchers, author Miskovic-Wheatley suggests: ‘Regular, informal check-ins could also help researchers who might feel isolated in their role within an organisation where research is not core business’. This again calls for systemic prioritisation to support research partners in their collaborative, community-based work roles in making greater change and staying well in doing so.

Concluding remarks

Our article offers actions, insights, learnings and recommendations from community and research partners in undertaking an 18-month collaborative project to uplift research, evaluation and learning within an Australian community-based mental health service. We describe the processes and the surrounding internal and external landscapes of our collaborative efforts, offering critical reflections on the logistical, organisational and systemic issues that impact the development of an equitable knowledge-sharing ecosystem within the mental health sector. Ultimately, our project represents a plea for greater consideration, collaboration and care in building equitable R&E practices to strengthen the health and wellbeing of our community.

As Sanchez et al. (2023, p. 988) put it, change requires ‘both interpersonal awareness and institutional transformation’. Building research, evaluation and learning praxis is predicated upon reflexivity, transparency and accountability (Stewart 2014). Our project demonstrates the experiences faced by services and academics within the mental health sector attempting to effect change, which necessitate recognition and action. While needs and motivations were strong, community services require practical support to build, embed, and sustain effective R&E cultures and practices to better capture, learn from, share and advocate for diverse community voices. This demonstrates the fundamental requirement for a systemic approach towards supporting R&E at the community level and nurture ‘a dynamic and passionate research workforce’ (author Miskovic-Wheatley) to bring about meaningful change.

Two things are therefore crucial: (1) an ecosystem of R&E within the eating disorders sector is prioritised and invested in, locating diverse community voices at the core; and (2) the responsibility to build equitable and responsive R&E cultures is shared between community members, academics, community services, policy makers and funders. As author Hansen reflects: ‘A key reflection is the need to dedicate resources that can support and commit to embedding sustainable practices rather than relying on roles that are already stretched’. Greater funding (for example, from research agencies and governments) is needed to support the costs of capacity and capability building within community services and the academic workforce, and large-scale, responsive R&E implementation efforts to enhance innovation and translation of meaningful local knowledges and reduce structural inequities (Bryant et al. 2023; Sanchez et al. 2023). Simultaneously, journals that welcome community-engaged ways of working are required to share these important knowledges.

Besides sharing the complex experiences of undertaking R&E at the community level, we explore the nuances of lived experience and benefits of working collaboratively through CBPR within a chronically under-resourced environment to incite cultural change. These reflections hold implications for how local knowledges are created, utilised and shared across the sector, and inform future capacity and capability building efforts within the community context. Arising recommendations add to existing community-academic engagement literature, offering actionable steps to building R&E capacity, capability, and cultures within and across community settings to enhance health research, translation and innovation.

Finally, we hope that what has emerged from our work lays out important, multi-level considerations to guide future R&E efforts towards greater responsivity, advocacy, and transformation within the eating disorder, broader community and mental health sectors. The strengths of our partnership in commitment, adaptability, resilience and joint learning represent positive markers of growth. With further consideration, resourcing and reflexivity, we hope that community members, service providers, peer workers, researchers, funders and policymakers can come closer together in their transformative efforts. We see connection as the only way to incite systemic transformation towards greater equity and responsiveness for our diverse and ever-changing communities – to hold, respond to and heal – together.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the traditional custodians of the land upon which this research was undertaken, and we pay our respects to Elders past and present. Sovereignty was never ceded.

We respect the valour, grit and endurance of lived and living experience communities; the ongoing work of all involved in this project is with the aim of improving the lives of people, carers, families and communities impacted by eating disorders, and the systems that implicate them.

We would like to express our gratitude to the following people for their engagement and support throughout this project: Caroline Salom, Rachel Withers, Charlotte Young, Breanna Guterres, Sarah Squire, Morgan Sidari, Phillip Aouad, Shehani De Silva, Rowland Mosbergen, Stephanie Shavin, Froukje Jongsma, Kirsty Jones and the broader teams at Eating Disorders Victoria and InsideOut Institute.

This work was conducted as part of the Mainstream project. We acknowledge all investigators/partners from the Mainstream Consortium in this work.

Author contributions

Sumedha Verma: Conceptualisation, methodology, project administration, investigation, resources, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, visualisation

Belinda Caldwell: Conceptualisation, writing – review and editing

Susie Hansen: Writing – original draft, writing – review and editing

Sarah Pollitt: Writing – original draft, writing – review and editing

Vicki Hams: Writing – original draft, writing – review and editing

Lauren Bruce: Supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing

Jane Miskovic-Wheatley: Supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing

Sarah Maguire: Conceptualisation, supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing

References

Ágh, T et al 2016, ‘A systematic review of the health-related quality of life and economic burdens of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder’, Eating and Weight Disorders, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 353–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0264-x

All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) 2021, Breaking the cycle: An inquiry into eating disorder research funding in the UK, Beat Eating Disorders, viewed 26 May 2025, https://beat.contentfiles.net/media/documents/APPG_Research_Funding_inquiry_report.pdf

April, K et al 2023, ‘“Give up your mic”: Building capacity and sustainability within community-based participatory research initiatives’, American Journal of Community Psychology, vol. 72, no. 1–2, pp. 203–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12674

Asaria, A 2025, ‘Improving eating disorder care for underserved groups: A lived experience and quality improvement perspective’, Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 13, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-024-01145-2

Ayton, A et al 2024, ‘From awareness to action: An urgent call to reduce mortality and improve outcomes in eating disorders’, British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 224, no. 1, pp. 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2023.133

Benz, C et al 2024, ‘Community-based participatory-research through co-design: Supporting collaboration from all sides of disability’, Research Involvement and Engagement, vol. 10, no. 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-024-00573-3

BetterEvaluation 2021, Empowerment evaluation, viewed 26 May 2025, https://www.betterevaluation.org/methods-approaches/approaches/empowerment-evaluation

Bryant, E, Koemel, N, Martenstyn, JA, Marks, P, Hickie, I & Maguire, S 2023, ‘Mortality and mental health funding – Do the dollars add up? Eating disorder research funding in Australia from 2009 to 2021: A portfolio analysis’, The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific, vol. 37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100786

Butterfly Foundation 2024, Paying the Price Report 2024, viewed 26 May 2025, https://butterfly.org.au/who-we-are/research-policy-publications/payingtheprice2024/

Calman, L, Brunton, L & Molassiotis, A 2013, ‘Developing longitudinal qualitative designs: Lessons learned and recommendations for health services research’, BMC Medical Research Methodology, vol. 13, no. 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-14

Case, AD et al 2014, ‘Stakeholders’ perspectives on community-based participatory research to enhance mental health services’, American Journal of Community Psychology, vol. 54, no. 3–4, pp. 397–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9677-8

Clark, MTR, Manuel, J, Lacey, C, Pitama, S, Cunningham, R & Jordan, J 2023, ‘Reimagining eating disorder spaces: A qualitative study exploring Māori experiences of accessing treatment for eating disorders in Aotearoa New Zealand’, Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 11, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00748-5

Eating Disorders Victoria (EDV) 2023, Position paper: Lived experience and peer work, Abbotsford, Victoria. https://eatingdisorders.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/EDV-Lived-Experience-and-Peer-Work-Position-Paper.pdf

Emmons, KM, Curry, M, Lee, RM, Pless, A, Ramanadhan, S & Trujillo, C 2022, ‘Enabling community input to improve equity in and access to translational research: The Community Coalition for Equity in Research’, Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, vol. 6, no. 1, p. e60. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2022.396

Engage Victoria 2023, Victorian Eating Disorders Strategy: What we heard report, Victorian Government, Melbourne, Victoria.

Farrar-Rabbidge, M & Squire, S 2022, Eating disorders and stigma, Butterfly Foundation, Sydney, https://butterfly.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Research-paper_Eating-disorder-stigma_June-2022.pdf

Fletcher, L, Trip, H, Lawson, R, Wilson, N & Jordan, J 2021, ‘Life is different now – Impacts of eating disorders on carers in New Zealand: A qualitative study’, Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 9, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-021-00447-z

Golenko, X, Pager, S & Holden, L 2012, ‘A thematic analysis of the role of the organisation in building allied health research capacity: A senior managers’ perspective’, BMC Health Services Research, vol. 12, no. 276. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-276

Guijt, IM 2014, ‘Participatory approaches’, Methodological Briefs: Impact Evaluation 5. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Office of Research. https://cnxus.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Participatory_Approaches_ENG.pdf

Hay, P, Aouad, P, Le, A, Marks, P, Maloney, D, Touyz, S & Maguire, S 2023, ‘Epidemiology of eating disorders: Population, prevalence, disease burden and quality of life informing public policy in Australia – A rapid review’, Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00738-7

Holden, L, Pager, S, Golenko, X & Ware, RS 2012, ‘Validation of the research capacity and culture (RCC) tool: Measuring RCC at individual, team and organisation levels’, Australian Journey Primary Health, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY10081

Holmes, AGD 2020, ‘Researcher positionality – A consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research – A new researcher guide’, Shanlax International Journal of Education, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.34293/education.v8i4.3232

Insideout Institute 2021, Australian eating disorders research & translation strategy 2021–2031, University of Sydney, Sydney, https://www.eatingdisordersresearch.org.au/static/6bce4b1c17e5c9217edbf2954193fabf/national-eating-disorders-research-and-translation-strategy-long-version-2024.pdf

Israel, BA, Eng, E, Parker, EA & Schulz, AJ (eds) 2012, Methods for community-based participatory research for health, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Israel, BA et al 2018, ‘Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles’, in B Duran, N Wallerstein, JG Oetzel & M Minkler (eds), Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity, 3rd edn, Jossey-Bass and Pfeiffer Imprints, Wiley, New Jersey.

Jones, N, Atterbury, K, Byrne, L, Carras, M, Brown, M & Phalen, P 2021, ‘Lived experience, research leadership, and the transformation of mental health services: Building a researcher pipeline’, Psychiatric Services, vol. 72, no. 5, pp. 591–93. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000468

Kent, BA et al, 2022, ‘Recommendations for empowering early career researchers to improve research culture and practice’, PLoS Biol, vol. 20, e3001680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001680

Lamarre, A, Levinem, MP, Holmes, S & Malson, H 2022, ‘An open invitation to productive conversations about feminism and the spectrum of eating disorders (part 1): Basic principles of feminist approaches’, Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 10, no. 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00532-x

Lloyd, N, Kenny, A & Hyett, N 2021, ‘Evaluating health service outcomes of public involvement in health service design in high-income countries: A systematic review’, BMC Health Services Research, vol. 21, no. 364. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06319-1

Milstein, B & Wetterhall, SF 1999, ‘Framework for program evaluation in public health’, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, vol. 48, no. 11.

Miskovic-Wheatley, J et al 2023, ‘Eating disorder outcomes: Findings from a rapid review of over a decade of research’, Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 11, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00801-3

Mooney, R, Dempsey, C, Brown, BJ, Keating, F, Joseph, D & Bhui, K 2023, ‘Using participatory action research methods to address epistemic injustice within mental health research and the mental health system’, Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1075363

Morton, M, Bergen, A, Crann, S, Bader, D, Horan, M & Bonham, L 2014, ‘Engaging evaluation research: Reflecting on the process of sexual assault/domestic violence protocol evaluation research’, Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, vol. 7, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v7i1.3395

Munshi, S, Louskieter, L & Radebe, K 2020, Decentering power in health policy and systems research: Theorising from the margins, International Health Policies, viewed 27 May 2025, https://www.internationalhealthpolicies.org/featured-article/decentering-power-in-health-policy-and-systems-research-theorising-from-the-margins/

Musić, S et al 2021, ‘Valuing the voice of lived experience of eating disorders in the research process: Benefits and considerations’, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 216–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867421998794

National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC) 2019, Peer work guide, viewed 27 May 2025, https://nedc.com.au/eating-disorder-resources/peer-work

National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC) 2023, National eating disorders strategy 2023–2033, viewed 27 May 2025, https://nedc.com.au/downloads/nedc-national-eating-disorders-strategy-2023-2033.pdf

NSW Treasury 2023, Policy and Guidelines: Evaluation TPG22-22, NSW Government, viewed 27 May 2025, https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/noindex/2025-03/tpg22-22-evaluation.pdf

Olmos-Vega, FM, Stalmeijer, RE, Varpio, L & Kahlke, R 2023, ‘A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149’, Medical Teacher, vol. 45, no. 44, pp. 241–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287

Parcell, E & Baker, B 2017, ‘Narrative analysis’, in M Allen (ed), The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 1069–72

Powell, JA & Menendian, S 2024, The practice of bridging, Othering & Belonging Institute, viewed 26 May 2025, https://belonging.berkeley.edu/practice-bridging

Raspovic, A et al 2024, ‘A peer mentoring program for eating disorders: Improved symptomatology and reduced hospital admissions, three years and a pandemic on’, Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 12, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-024-01051-7

Reed, R 2015, ‘Program evaluation as community-engaged research: Challenges and solutions’, Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 118–38. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v8i1.4105

Robinson, T et al 2020, ‘Bridging the research–practice gap in healthcare: A rapid review of research translation centres in England and Australia’, Health Research Policy and Systems, vol. 18, no. 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00621-w

Sadler, LS, Larson, J, Bouregy, S, Lapaglia, D, Bridger, L, Mccaslin, C & Rockwell, S 2012, ‘Community–university partnerships in community-based research’, Progress in Community Health Partnerships, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 463–69.

Sanchez, AL, Cliggitt, LP, Dallard, NL, Irby, D, Harper, M, Schaffer, E, Lane-Fall, M & Beidas, RS 2023, ‘Power redistribution and upending white supremacy in implementation research and practice in community mental health’, Psychiatric Services, vol. 74, no. 9, pp. 987–90. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.20220209

Singleton, GE 2013, More courageous conversations about race, Corwin Press, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Stewart, J 2014, Developing a culture of evaluation and research (CFCA paper no. 28), Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne, Victoria.

Utpala, R, Squire, S & Farrar-Rabbidge, M 2023, Eating disorders peer workforce guidelines, Butterfly Foundation, Sydney. https://butterfly.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/24003_Butterfly_Design_PeerWorkforceGuidelines_A4_72dpi-5.pdf

Verma, S 2024, ‘A case for re‐conceptualizing the “atypical” – A lived experience perspective’, International Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 1026–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.24086

Verma, S, Salom, C, Miskovic-Wheatley, J, Aouad, P, Sidari, M, Caldwell, B & Maguire, S 2024, ‘Building research and evaluation within an Australian community eating disorder organisation through academic partnership: A pragmatic protocol’, Gateways International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1–45. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v17i1.9145

Wallerstein, NB & Duran, B 2006, ‘Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities’, Health Promotion Practice, vol. 7, no. 3, 312–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839906289376

Wilson, E 2019, ‘Community-based participatory action research’, in P Liamputtong (ed), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences, Springer, Singapore, pp. 285–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_87

Appendix 1

Personal reflections (listed in authoring order)

Sumedha Verma: Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Eating Disorders Victoria & InsideOut Institute

In leading this work, I was afforded great space and autonomy. Initially, I was tasked with evaluating the Carer Coaching Program yet learned quickly from conversations on the ground that a top-down approach would be ultimately problematic; the organisation’s prior experiences with research and evaluation had left somewhat of a disempowering legacy, which I was determined to correct.

As a strong proponent of community-driven research and evaluation, I believe that community services should be equipped to take the lead on things that directly affect them, including how grassroots knowledges are captured, utilised and shared. My own positionality in decolonial praxis inevitably shaped the look, feel and direction of this project as one that is community-centric and participatory at its core – something that brings me deep pride. This was possible with the encouragement from senior partners who similarly believed in community-driven ways of working and held great trust in my vision.

This freedom and trust created an environment of unrestrained exploration and learning; my mind was allowed to roam deep and wide. I read up extensively on various literature and reached out to other scholars and professionals doing aligned work in search of guidance, mentorship and kinship. Collectively, this self-education and constellation of new connections provided me with great support and ultimately sharpened my thinking and doing. However, this at times was a confusing and lonesome experience in the face of structures and systems that do not move at the rate they need to.

The frustrations of working within a resource-limited and structurally isolated role are real and felt by the researcher, which is why scaffolding and supports are crucial. Otherwise, we risk losing people who tenaciously inspire change within difficult landscapes to marginalisation and neglect, particularly those of us at various intersections. Attention, consideration and connection is necessary to manage the complicated and challenging nature of this transformative, systems-level work.

This work was tough, and I learned that connection was, and is, the key to everything. Being embedded within a community mental health not-for-profit setting exposed me to people of tremendous resolve – both those who draw upon their lived experiences and steadfast allies. The community of colleagues/friends I have found in my experience catapulted me into taking up space, using my voice, respecting my power and advocating change that is needed in the world.

Being suspended in a web of new friends, collaborators and mentors has supported me in taking various intellectual and emotional strides. I have learned much about power and progress over the past 18 months – what stalls change and what inspires it, and how we know when to step away to maintain our own wellbeing. There are deep learnings that happen on the ground through applied research.

What ought to lie at the core of any and all change efforts are the voices of those in our diverse communities. Ultimately, we need systems and people that comprise them that are aware of their own power, privilege and capability to maintain archaic, othering, at times hurtful, ways of being and doing. This requires listening, learning and committed action.

Ultimately, I see this project as being one small, yet fundamentally important, step towards more equitable, reflexive and responsive community care. We, of course, have a long way to go, and we can only get there if we move together.

Belinda Caldwell: CEO, Eating Disorders Victoria

As CEO, my main goals in integrating more evaluation into our programs and services are threefold: using data to better tailor our services for our community, ensuring our team feels rewarded in their work, and effectively communicating the value of our work to the broader community and funders to ensure sustainable funding.

Taking on the task of embedding a co-designed evaluation into our organisation’s core operations has been a learning experience, presenting both anticipated and unexpected challenges, as well as occasional tensions. One significant challenge stemmed from differing perspectives among team members regarding priorities, sometimes causing obstacles, lack of cooperation, or anxiety about the processes involved. Responsibility for designing and implementing this project largely rested with our embedded researcher, a setup I would reconsider in the future by integrating research and evaluation responsibilities into the leadership team’s performance expectations at Eating Disorders Victoria (EDV). While having dedicated personnel with research and evaluation expertise can drive structured and time-bound efforts forward effectively, a more sustainable approach would involve holding leadership accountable with dedicated support staff to execute these initiatives.

While EDV has employed co-design principles in developing programs and services in the past, co-designing research and evaluation was a new endeavour. One observed challenge was the initial divergence in understanding the evaluation’s purpose. My dual perspective as both a carer with lived experience and someone with extensive experience in carer support led me to have clear initial ideas about what aspects we should evaluate and some preferred tools. Conversely, our Carer Coaches focused heavily on service delivery, finding it challenging to adopt an evaluative lens on effectiveness. Other team members approached the process from organisational or clinical perspectives, aiming to align any new processes with existing quality improvement initiatives. Managing these diverse viewpoints proved challenging for our embedded researcher in reaching a cohesive outcome.

A critical issue that emerged was the distribution of decision-making power. Ambiguity in this area at the project’s outset created ongoing challenges. While oversight for the specific evaluation of caregiver coaching had a designated decision-maker, my involvement was more from a procedural interest, ensuring the evaluation aligned with organisational goals of demonstrating outcomes. However, clarity on who had final decision-making authority over various project elements was lacking, causing confusion and frustration. In future evaluations, I aim to establish clear parameters upfront to assign decision-making responsibilities, thus preventing ambiguity and enhancing efficiency.

The reflections we have undertaken as part of this process have enabled us to reframe what evaluation and research will look like at EDV into the future and, despite the challenges that have been key learnings, we are deeply committed to continuing to embed what we have learnt over the last 18 months.

Susie Hansen: Director of Clinical and Telehealth Services, Eating Disorders Victoria

This project within Eating Disorders Victoria (EDV) has been pivotal in the way that we consider and build a whole-of-service system of care within EDV, which has embedded monitoring and evaluation. My involvement, as the Director, meant holding this vision and stepping out from the original intention of review one component of the service, the eight-week Carer Coaching Program.

For EDV, underpinning all decision making is the objective to ensure the pathway to appropriate care is seamless for those experiencing an eating disorder in Victoria. Key to this objective is ensuring that the practical entry points to EDV services are straightforward and limit further burden. EDV’s evolution, driven by incremental funding, has resulted in systems tailored to individual program needs. Post-COVID stability provided an opportunity to consider the entire system of care, including embedding monitoring and evaluation within whole-of-service systems of care. In recent years, there has been a commitment to review a variety of practices across EDV to eliminate hurdles for those accessing care, with the aim to give positive experiences of help seeking.

An issue for EDV and similar community organisations is the burden of monitoring and evaluation on service users. Simplifying the support journey for those impacted by eating disorders is central to EDV’s philosophy. Given the complexity and intensity of eating disorder treatment, adding barriers like additional forms or lengthy questionnaires informed our project decisions.

In the early days of the project, the focus shifted from the Carer Coaching Program to those whole-of-EDV practices that were required to make this sustainable. Reviewing and embedding key tools such as the common EDV Engagement Agreement and automated data collection became a priority. This effort coincided with a significant IT project aimed at simplifying and consolidating automated information gathering and eliminating standalone consent and data collection processes. This alignment, however, impacted the rollout of the Carer Coaching Program evaluation project causing delay and reasonable tension within the project team. The resources to undertake two major projects within EDV was limited, resulting in myself and others intensely involved with both, on top of other role expectations.

A key reflection is the need to dedicate resources that can support and commit to embedding sustainable practices rather than relying on roles that are already stretched. Another key reflection from a leadership perspective was the importance of committing the time at the commencement of research/evaluation projects to ensure there is a shared vision and understanding.

A major roadblock and learning was maintaining a common understanding of the long-term objective. Shifting focus from one service to elements impacting all-of-EDV caused delays and strain, particularly in achievement of expectation from the research partnership. Realigning the vision was crucial however given we had not established ‘how’ we could have these conversations constructively, misunderstanding and frustration developed.

Project groups are not dissimilar to therapeutic groups with the need to establish expectations, decision making, engagement and communication styles, along with the ‘how do we respond when is something is not going to plan’ discussion prior to commencement. If there is one takeaway from this, it is spending more time planning and establishing the group norms rather than launching into the depths of doing.

Over time, the project’s starting and ending points changed. I do not see this as a negative but a sign of progress and maturity of EDV. Embedding monitoring, evaluation and learning within the systems of accessing care has been more complex; however, ensures the result is sustainable and accessible for the community throughout their help-seeking journey.

Sarah Pollitt: Manager Telehealth Support Programs and Practice Development Lead, Eating Disorders Victoria

This project has highlighted and reiterated the importance of slowing down, allowing adequate space within projects and practising known and evidence-based implementation science. Within small non-government organisations (NGO) such as Eating Disorders Victoria (EDV), this step may be understandably lost due to competing priorities, limited time and stretched capacities. In this project, the passion and commitment for the project team was palpable and due to timeframes the project started with a rapid pace. This however missed key considerations in the what, the who and the how like those described by the Center for Implementation (2021).

On reflection, areas of importance included taking time to consider the working group; who should be involved, clearly defining roles, expectations and responsibilities, reflecting on strengths in individual working styles and prior experience/knowledge. In the wider context, consideration for current capacities both individually and organisationally and planning the how; what meetings would occur, how documents would be shared, and where the researcher and project was positioned within the organisation and priorities.

At the time of our project, EDV was completing other intersecting projects such as the review of software systems, which was both enabling for this project yet at times required a slower pace as they intersected. This project involved two research projects co-occurring: evaluation of embedding research in a small NGO with InsideOut Institute (IOI) and outcome research of the Carer Coaching Program. The projects’ co-occurrence required clearer consideration and planning. For example, the researcher reported to two organisations: IOI and EDV. At EDV, the project directly related to the Carer Coaching Team, yet they were positioned in the Education and Research Team. This effectively led up to four reporting lines, which led to challenges in connection and relationship of the researcher to parts of the project team and confusion in project direction, role responsibilities, and decision making at times.

Through the challenges the project adapted, enabling embedded and wider reaching outcomes for EDV than purely the Carer Coaching Program. A refined whole-of-service approach for data collection and future research has been developed. The Carer Coaching Program evaluation is now in use. There are also key reflections learnings for the organisation moving forward on how we think, plan and evaluate projects.

Vicki Hams: Lived Experience Program Facilitator, Eating Disorders Victoria

As the lived experience carer representative in the project, I sometimes felt like the ‘disruptor’ in the process of embedding the research and evaluation project! Whilst understanding the importance of data and evaluation, I held the voice of carers at the very heart of this process. I wanted the impact to the carer to be of absolute minimum and to be able to collect meaningful data so the Carer Coaching Program could be successfully evaluated and/or learnings be implemented. Sometimes, it felt like the two things were not aligning.

I was very conscious of protecting carers from additional burden when they were help seeking from our organisation at a time of high distress and fear. I felt anxious that the organisation’s need for too much carer information may reduce our carer clients to numbers, and could risk being insensitive to the very real-world experiences of what carers go through.

During meetings, I felt slightly uncomfortable to voice my opinion in relation to this because I had been one of the creators of the program undertaking the research project as well as the person delivering the content on a daily basis. I was aware that anything I had to say might seem as if I was being defensive of the program. In reality, I was looking forward to seeing any improvements that could be made through feedback from embedding research and evaluation.

During the co-design process, due to time constraints on both the project and the normal workday, some of the communication became ad hoc. Reviewing documents became complicated – both through it being unclear which was the latest version and what involvement I was expected to have. This made it tricky to know whether my comments or thoughts had been received or dismissed.

Being the client-facing worker, it would be me who would be asking carers to undertake questionnaires before I could assist them in the Carer Coaching Program, so I had to be comfortable doing so for the new research/evaluation processes to be feasible. I knew that ultimately if the process was difficult or too intrusive, we may not get the take up due to adding to carer burden. This highlighted the importance of involving program facilitators in research and evaluation design processes, especially those of us like me who hold their own lived experiences and who strongly advocate for the needs of lived experience communities.

Lauren Bruce: Reflection not provided

Jane Miskovic-Wheatley: Research Stream Lead, InsideOut Institute

The challenge of bridging the research-translation gap necessitates integrating clinical and community environments with research laboratories. One promising strategy is embedding research in natural translation hubs, such as consumer organisations. These organisations, with their focus on lived experience and co-design, offer unique advantages for implementing evidence-based care, evaluating consumer-led initiatives, and linking empirical research with real-world experience. This integration can facilitate genuine co-production of knowledge, promoting meaningful translation and change.

However, consumer organisations typically rely on grants and donations to deliver services, often leaving little room for embedded research. When research or evaluation funding is available, it is usually minimal, perhaps covering only a part-time position. This scenario creates a paradox: early-career researchers (ECRs) may be hired for these roles but often lack the experience, support, and resources to effectively lead and facilitate projects independently.