Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 18, No. 1

January 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE (PEER REVIEWED)

A Curated Walk with Peer Researchers and their Communities: Engaging a Research Journey Toward Meaningful Impact

Bradley Rink1, Gina Porter2, Bulelani Maskiti3, Sam Clark4, Caroline Barber4 with peer researchers Jeffery Ashitey, Archie Evans, Siyamkela Jucwa, Baphelele Malangabi, Sisonke Mpiliso, Siyabonga Ntozini, Ansari Pulickal Abdul Azeez, Thobinceba Siyatha, Bonginkosi Sosanti, Raqib Uddin and Dillon Watson*

1 Department of Geography, Environmental Studies & Tourism, University of the Western Cape

2 Department of Anthropology, Durham University

3 Independent Researcher

4 Transaid

* Additional peer researchers remain anonymous for ethical reasons

Corresponding author: Bradley Rink, brink@uwc.ac.za

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v18i1.9217

Article History: Received 01/07/2024; Revised 30/11/2024; Accepted 05/12/2024; Published 01/2025

Abstract

As a collective of peer researchers, scholars and members of a non-profit organisation, we have come together to share a curated walk through low-income communities in Cape Town and London. We do so with the intent of exploring the embodied and social experiences of walking and writing research differently through a collaborative process of listening, co-creating and sharing knowledge about the pedestrian mobilities of young men as mediated by the precarities of urban life. Our walking-writing practices are a hybrid of the actual practices of walking and potential for enacting change by valuing the everyday experiences and knowledge of peer researchers. The curated walk that we share guides readers on the research journey that we have taken together from the homes of those involved to the metaphorical centre of power in the cities/regions where our work takes place, with the intention of long-term, meaningful impact.

Keywords

Peer Research; Walking; Gender; Young Men; South Africa; United Kingdom

Take your research for a walk. How will you respond by walking-with?

(Springgay & Truman 2018, p. 142)

A curated walk in Cape Town and London

The journey described below is a comparative walking-writing practice through Cape Town, South Africa and London, United Kingdom. It is the result of collaborations between 12 peer researchers who live in the communities about which we write, scholars whose work entails research and teaching, and members of a non-profit organisation based in London whose work focuses on mobility outreach and training in cities across the Global South. Our walk is a propositional activity, inspired by Springgay and Truman (2018), who define such activities as ‘hybrids between potentiality and actuality’ (Springgay & Truman 2018, p. 130). What follows is a walking-writing practice that traces actual walking journeys, while at the same time exploring their potential for meaningful change. In our case the proposition lies not only in our shared concern in exploring the experiences of walking from home to transit hubs in the neighbourhoods where our peer researchers live, but also in creating impact beyond academia. Through our curated walk, we share a ‘temporal and spatial co-presence’ (Vergunst 2010, p. 386) on the city streets of Cape Town and London.

Walking is both an embodied practice of mobility and social phenomenon that has gained interest from scholars over recent decades despite being taken and understood as a mundane practice (Lorimer 2016). It is a practice that helps to make sense of the city while engaging a range of senses themselves (Middleton 2010; Springgay & Truman 2018; Vergunst 2010). Through the act of being in the city, we can sense slices of urban life from the perspective of the street (Belkouri, Lanng & Laing 2022). However, walking is often invisible even in the scholarly literature of transport and mobilities (Sagaris et al. 2022). Notwithstanding its importance in African cities, walking is absent from policy and infrastructure investment (Benton et al. 2023). Our collective walk thus helps to illustrate its importance in everyday urban life while also undermining conventional thinking about how young men practise and experience walking.

We acknowledge the lack of evidence that articulates how the walking journeys of young men in their communities are experienced, the power differences amongst members of our collective and the impact that those historically embedded inequalities have on those whose voices are heard in research findings. We are interested in and have insights to share about many aspects of walking: (1) how walking is done as an embodied practice; (2) how it is experienced as a social practice; (3) the enablers and limitations of walking; and (4) the pleasures and perils that come with walking on a daily basis, even if one is a captive pedestrian due to financial constraints, scheduling constraints, or a lack of other modes of transport. As we have learned through our collaborations, however, being labelled as a ‘captive pedestrian’ can obscure the desire that some may have to walk, and their agency in deciding to do so. It may also overlook and undervalue the pleasures of walking.

‘Walking-with’ peer researchers

Over the past decade, increasing attention has been paid to the potential for change when peer researchers are involved in the research process. There is a simple reason for this – peer researchers are experts in their own lives. From the perspective of scholars who engage in research and teaching, peer research may help to facilitate access to groups who can be reluctant to engage with professional researchers, and enable higher quality, more nuanced data, built through insider understanding, empathy and sensitivity (Porter 2016; Yang & Dibb 2020). Community-based peer research is a participatory research method in which research subjects from the same social or generational group are active partners in the research process – they are sometimes called ‘community researchers’ or ‘peer interviewers’ (Burke et al. 2019; Devotta et al. 2016; Mosavel et al. 2011; Porter et al. 2023b).

Peer researchers were identified through community-based organisations, non-governmental organisations and leaders within the communities in question. They helped to frame the research instruments and provided data in the form of mobility diaries and interview transcripts with community members. Scholars performed the work of sourcing funding, establishing ethical clearance, organising peer researcher training workshops, curating vignettes and writing up this journey in its present form. Curation was necessary on account of our ethics of care in that only project leads and research assistants had access to all research data. Although peer researchers did not have access to others’ data, stakeholder workshops and peer researcher reflection sessions provided opportunities to discuss findings with everyone at the conclusion of the project. Both individual and collective voices (using pseudonyms) marked our journey. Vignettes from peer researchers’ mobility diaries and their interviews with community members were spanned by reflective bridges from other team members. Together, our curated walk illustrates the varied experiences of walking in our study sites.

The choice of our two study sites was not by accident. The collaborators have noted the steady development of knowledge over the past decade regarding challenges faced by women as they travel around urban areas of the Global South and North, yet young men’s experiences have been largely ignored. With evidence from team members’ research on young women’s mobility in low income neighbourhoods of Cape Town, the present collaboration also sought to test the applicability of a participatory methodology developed in African urban mobility contexts in cities in the Global North; hence our comparative study across geographies of North and South. The choice of study sites was also based on the differences in perceived walkability and prevalence of walking for residents of low-income communities in each. Despite the legacy of apartheid spatial planning on walkability, residents of Cape Town’s low-income ‘township’ communities rely on walking (Benton et al. 2023). At the same time, the dense network of public transportation in London might skew perceptions of the need to walk, and feeling safe doing so. Each city brings to the study a unique environment for walking and for exploring young men’s experiences of the same. While we give some general clues as to where our walking-writing practices take place, our ethics procedures require us to keep the study sites anonymous. But our ethics of care extends beyond the rules imposed by our institutional committees. By keeping the specific sites anonymous we also seek to avoid further stigmatising the low-income areas where we walk and write.

Our walk traces a journey from home to the centre; from the periphery to the core, where our research collaboration may have impacts beyond academia. We journey to the metaphorical ‘centre’ of the city by way of speaking and writing back to relevant stakeholders and policymakers in our respective cities, and in doing so help to effect change in policy with respect to walking. Our curated walking-writing practice is prefaced by an exercise in mapping our journey together, and constructed by vignettes of everyday walks from home to transit points in our communities of concern. The use of the term ‘curated’ describes both our ethics of care (Fraser & Jim 2018) and the solidarity (Reilly 2010) that we wish to achieve through the walk. It also demonstrates our shared accountability to the walking-writing process. We are inspired by Fraser and Jim who highlight the Latin origin of the word ‘curate’, whose meaning suggests taking ‘care of objects, communities, or the living, with all the aesthetic, social, political, and environmental difficulties and differences that this might involve’ (Reilly 2010, p. 7). Our curation lies in a combination of reflections from our research materials alongside more conventional theoretical commentary. Like most journeys, the curated walk that we guide you along is not linear. It weaves through the relational geographies of the peer researchers’ communities, employing a peer research methodology that is meant to elevate the voices of individuals who may only be acknowledged as ‘subjects’ in traditional research design. The peer research methodology therefore helps to transform scholarship and knowledge production by valuing insights from peer researchers starting with research design and implementation.

Our peer researchers were unemployed or casually-employed young men between the ages of 18 and 35 years. Although unemployed or casually-employed, they agreed to devote time to our project, and were paid a stipend for the time they devoted to it. Other members of our team were being paid for their research time, whether directly through project funds or indirectly through a monthly salary from their institution. Therefore, an important step in equalising the relationship was to ensure that peer researchers were also compensated for their time. With formal ethics approval achieved (Durham Ref: ANTH-2023-01-10T15_46_55-dan1rep / UWC Ref: HS23_1_6) and our teams assembled in both study sites, we embarked on the first steps of our walk, guided by setting expectations and framing the geographical context of our explorations through a mapping exercise.

Mapping the way forward

Journeys often begin with a map, and ours was no different. The group of collaborators in both Cape Town and London came together for the first time during five-day peer research training workshops in each city that enabled the team to plan and visualise the journey ahead as one does with a map. Implicit in the design of the workshops were opportunities to listen, equalise power in the research process, collaborate in the design of the research instruments, co-create knowledge through mapping and discussion, and celebrate achievements. As we set out on our walk together we found that we had different but compatible goals and expectations. These goals and expectations may be likened to mental maps of what we might expect or hope for in the journey ahead, and how we envision the path that we want to take.

We started on day one of the workshops by asking each member of the team what they wanted to achieve from the walking-writing practice. Goals expressed included: (1) learning about/from the communities involved in our study; (2) relationship building amongst each other and the communities in question; (3) effecting change and building trust in researchers; and (4) skills development such as communication and critical thinking that could be transferrable beyond the time and scope of the project. The goals expressed align with the views of Porter et al. (2023b), who highlight the potential attributes of peer research as including: (1) peer researchers’ personal empowerment (as training, work experience and social interaction with researchers build self-esteem); (2) mitigation of the usual power imbalances between researcher and research subject; and (3) wider community empowerment, encouraging action.

Goal-setting and expectations were followed by establishing the ground rules that would guide the workshops in the days ahead. Peer researchers and the rest of the project team worked together to establish shared rules of conduct with respect to: (1) starting and finishing times for the daily sessions; (2) listening carefully to one another; (3) addressing each other with respect; (4) allowing others to speak without interruption; (5) whether or not to allow photography during the sessions; (6) confidentiality of personal information; and (7) use of mobile phones during workshop sessions, etc. The rules that we established collaboratively had to be agreed by all participants before we moved on. These preliminary steps in establishing respect, equality and openness also included some points of housekeeping such as discussing and signing of peer researcher informed consent forms.

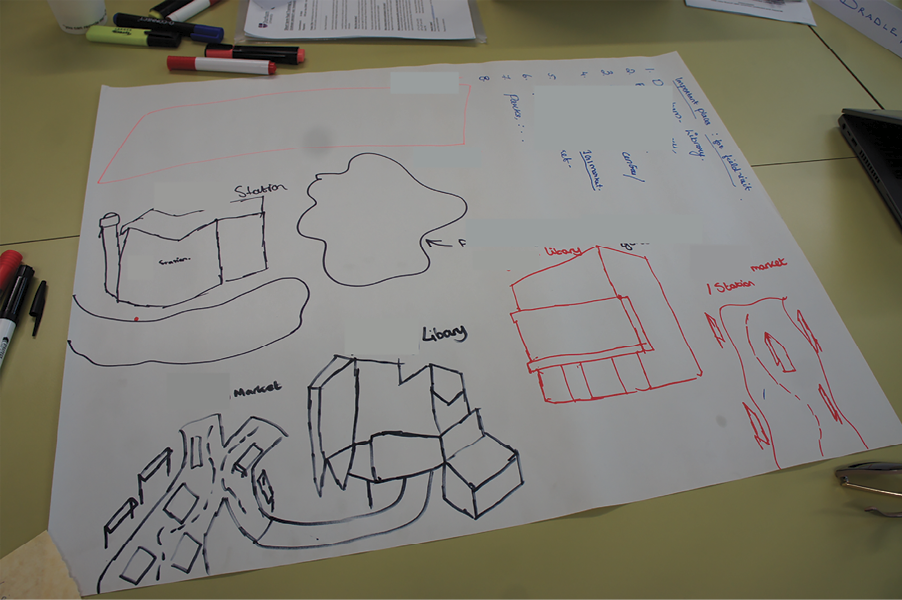

From the start we established a partnership of equality and valuing of knowledge from the peer/community context. Our first exercise in creating cognitive maps from individual and shared experiences of study areas allowed peer researchers to share and value their own knowledge while imparting it to the entire team. Appreciating knowledge from peer researchers is not simply about respect for each member of the team, but is also important for gaining critical insights from everyday mobility practices (Rink 2020). After getting to know each other, setting expectations of what each member would like to achieve by participating in the project and establishing ground rules for conduct, we initiated a mapping exercise whose inputs were laid down on paper by the peer researchers through vigorous discussion, debate and consultation (see Figure 1). These maps became an important starting point for discussing the matters at hand in each of the low-income study sites, and formed a critical understanding of the geographic contexts of the communities about which we would write. This included the geographical extent of the communities, their urban form and infrastructure(s), the places to which people travel (and how), as well as qualitative indicators such as places of importance and meaning, and places of safety or danger. As the maps came together, peer researchers from different neighbourhoods in each city were invited to present the maps to their entire group. Discussions followed, particularly to understand elements included during the process of drawing the maps. We asked questions of each other as the richness of the maps emerged: (1) What are the good/bad things about the area in which you live? (2) What are the reasons that people travel, and how? (3) Where does walking fit into the mobility practices of the neighbourhood?

Figure 1. Community mapping at peer researcher workshops in Cape Town and London (Authors)

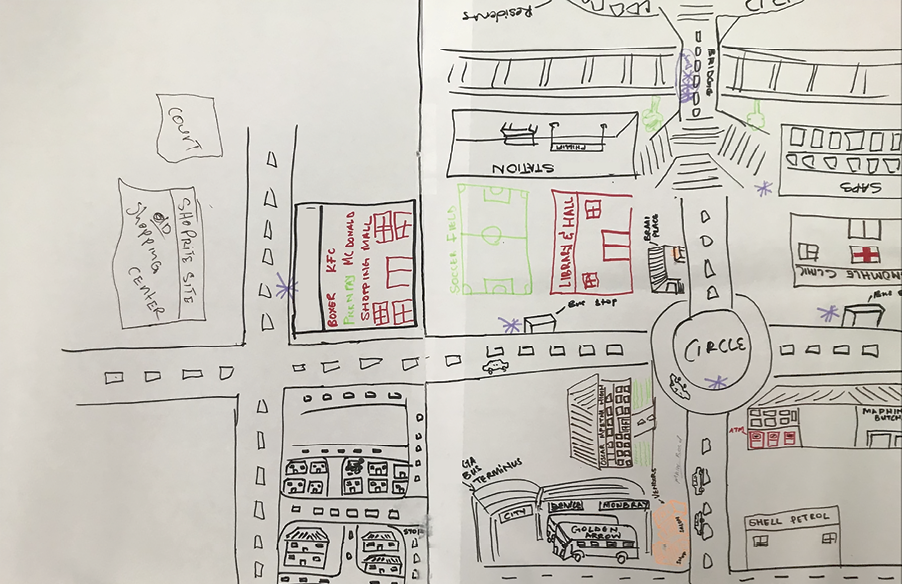

This mapping exercise emerged out of the desire to establish the context of the study sites, understand key issues in the everyday experience of walking, develop new knowledge, and hone research skills together (see Figures 2a and 2b).

Figure 2a. Community map from Cape Town workshop (Authors)

Figure 2b. Community map from London workshop (Authors)

Aside from training our collective eyes and ears in understanding the social and physical landscapes of the study areas, the workshops also allowed us to develop our research instruments. This included discussing how to engage in reflective writing of daily ethnographic mobility diaries, development of interview questions, and how to conduct interviews and record responses from community members. Related to this were discussions on establishing procedures for the ethical application of our research methodology in-line with ethics approval from the respective academic institutions that were part of the project. This included procedures for informed consent, safety and respect with participants during fieldwork.

The workshops also provided an opportunity for peer researchers to practise interviewing techniques by walking together in small groups of two or three in the vicinity of the training venue. While one peer researcher asked a set of research questions and noted responses from the second peer researcher (respondent), the third observed and intervened if any issues arose. With an opportunity for each to practise the roles, and a group debrief thereafter with all workshop participants, we turned our senses to the process of collecting walking stories and understanding the urban landscape.

Between the two study sites, language challenges also emerged. Workshops in Cape Town and London were conducted in English; however, English was not the first language for our peer researchers in Cape Town, and despite being the lingua franca in London, it was not the primary language for all peer researchers there. Peer researchers were assisted with translation of texts where needed. Although the multilingual environment created some inconsistencies in the fluency of vignettes, they nonetheless provided detailed evidence of walking experiences.

We took the time to celebrate milestones along our journey by recognising the achievements of peer researchers in ways that extend the impacts of their participation beyond the publication of research outputs. We did this by providing peer researchers with certificates to mark significant stages of our journey – one upon the completion of the peer researcher training workshop (see Figure 3 below), and another after the completion of data collection and engagement during stakeholder meetings and reflection sessions. Peer researchers use these certificates to demonstrate their skills in job applications.

Figure 3. Ready to walk – Celebrating the completion of peer researcher workshops in Cape Town and London (Authors)

The mobile ethnographic methods that we have discussed and practised help to explore the embodied and social act of walking, as we ‘[travel] with people and things, participating in their continual shift through time, place and relations with others’ (Watts & Urry 2008, p. 867). By collectively seeing, hearing and broadly sensing (Middleton 2010) different aspects of the city around us – and sharing those reflections – we engaged in a walking-writing practice with each other (Springgay & Truman 2018, p. 142). These formative steps not only prepared us all with skills and knowledge related to walking in the city, but also provided the impetus for our walk to get underway.

Setting off on a Monday morning

Our walk begins in Cape Town early on a Monday morning when residents set off to work, school, visits to social service organisations or local clinics. The low-income communities that we explore (both in Cape Town and London) are situated on the socio-economic and geographical periphery of the metropoles they are part of and very few of the young men interviewed or part of our team of peer researchers have access to a private car; thus walking is a key mobility practice. Unlike in London, residents in the communities we engaged with in South Africa have to grapple with the enduring legacy of racist spatial planning that predates apartheid (Mabin & Smit 1997) and continues to shape poverty and precarity in Cape Town’s townships and informal settlements (Huchzermeyer & Karam 2006). As we set out, the walk within the community is a ‘first mile/last mile’ strategy for connecting to public transport, or is part of a journey that is entirely on foot. Time is of the essence, as distances to be covered are often great. Thus for many residents of these communities the day begins early, when it is still dark outside. Despite the early hour, the streets of the townships in Cape Town are buzzing with activity. Along our walk we encounter others, engaging sometimes in acts of care and at other times seeking to avoid them. As we walk, choices have to be made; a negotiation of the potential risks that lie in the darkness, as Sipho from Cape Town notes:

Today was kind of different because it was darker, and I usually walk to the taxi rank but today I decided to catch one of those morning neighbourhood taxis that take me straight to the taxi rank because I had to think about my safety and I was kind of intimidated by the challenges I might come across when walking in the dark. While waiting for the taxi to arrive there were familiar faces from within my neighbourhood who were also waiting for the taxi so I was comfortable since I wasn’t alone in the dark.

On days like this, the darkness is complicated by periods of scheduled electricity outages due to undercapacity, euphemistically called ‘load-shedding’ in South Africa. Under these circumstances, the neighbourhood streets are in complete darkness, with only the possibility of a faint glare from a mobile phone of a hurried pedestrian, or the dazzling headlights from a passing minibus taxi. Sometimes, the temporalities of darkness combined with poor weather and the threat of violence eliminate Sir J’s desire to walk at all:

This day I decided I am not gonna go anywhere because the weather is not as good it is raining at it rains early in the morning and the weather news did say last night that the rain is going to be 100% today. I didn’t even jog because it’s cold and rainy at the same time it’s windy and if I can do the outside activities I can probably catch flu.

While I was at home laying on my bed the time it was past 9am in the morning … I heard gun shots at the back of my house … I was still in bed the shots when coming from different direction and you could hear that these people that were shooting are fighting.

It may not be external forces that keep us from walking, but our own fears and anxieties from past experiences, as Nitin, aged 34 from London, notes:

… I was on my way to work when I was mugged. I was walking home from the train station when a man came up behind me and grabbed my bag. I tried to fight back, but he was too strong. He took my bag and ran away. I was left standing there, shaken and scared. After that experience, I was really shaken up. I was afraid to go out alone, and I was worried about being mugged again. I eventually started to go out again, but I was always very careful. I made sure to walk in well-lit areas, and I always kept my phone with me in case I needed to call for help.

Facing vulnerabilities posed externally by incidents of crime and internally by one’s own insecurities can have a chilling effect on access opportunities for work, education and social contact. Before we started our journey together, we sought to question some commonly-held assumptions regarding the gendered nature of walking that often suggests that young men are invulnerable. As we walk the journey with our peer researchers and their communities we provide clear evidence of some of the challenges that young men face, most of which are largely ignored by scholarly research in favour of studies focusing on road safety, traffic injury and men’s health.

Travel perils: Exposing vulnerabilities

We have sensed danger along the path of our walk. Conventional thinking about young men and their walking journeys suggests that these individuals are invulnerable and walk without concern. This sentiment is underscored by our group discussions with peer researchers, especially those in Cape Town who cite cultural expectations of men being strong, brave and fearless. Our collaborative walk helps to dispel such notions and expose the vulnerabilities of young men as they go about their daily lives by walking through their neighbourhoods. Both peer researchers and their community interlocuters provide evidence of the perils presented during the walk to the transit hub. Such perils include: (1) theft, with the strong possibility of being accompanied by violence; (2) long distances; (3) long waits to connect with public transportation; (4) temporalities of poor weather and darkness; and (5) dangers associated with poor driving and motor vehicle accidents that may involve pedestrians.

Concerns over theft while walking, possibly accompanied by violence, is the dominant theme along the journey in Cape Town at any time of day, though in London it is more of a late night concern. Nearly all of the peer researchers and their interviewees in Cape Town have been witness to street robberies, some taking place at gunpoint. The fear of crime is complicated by the dual-impact of feeling ‘useless, weak and vulnerable’ as a result of being victimised. The threat of crime and violence is especially felt while walking alone or waiting at a transport hub and is heightened during periods of darkness in the early morning hours or late at night, or in the case of South Africa, during night-time load-shedding where one noted how he fears for his life. Mark, a 20-year-old immigrant from Mauritius who lives in one of the London study locations, tells us how he compensates for such perils, even putting on a friendly smile to avoid conflict:

I plan my journey during daylight hours to ensure better visibility and a safer environment. I avoid late evenings when the streets might be less crowded. While walking, I remain observant of my surroundings, noticing any changes in the environment or potential obstacles ahead. I greet passersby with a friendly smile or a nod, maintaining a positive and friendly demeanour.

Risk and vulnerabilities are both temporally determined, as Mark notes, but also spatially dependent. While Mark avoids late evenings and empty streets, peer researchers in Cape Town experience the highest risk when walking in high density informal settlements with narrow alleys. As one recalls:

Once I get out of [specific high-density area] unharmed in the morning then I know I’m safe afterwards.

Mark’s walking experience cannot be separated from the larger journey that he and others in London have taken over the course of their lives. As an immigrant, his experience of walking is often mediated by the sense of being different, a point that several of our London peer researchers highlighted in our conversations and in their walking diaries. One had moved to London from Accra at the age of nine, while another had only arrived in the United Kingdom weeks earlier from his former home in Lagos. The traces of their journeys were thus understood as part of larger scale mobilities.

Pretend to tie your shoelace: Tactics for safe walking

An untied shoelace slows us down. We must stop and make it right. However, tying a shoelace can also be a tactic that serves as a means of scanning the environment while preserving one’s dignity, as we learned from Mabhuti, a Cape Town resident in his early 30s who was born in a small town in the Eastern Cape:

I walk in the afternoon to the bus [to get to a job in a distant neighbourhood]. It takes 10 minutes. It’s not safe. I’ve not experienced it, but I’ve seen others robbed at gunpoint. You can get robbed waiting at the bus. I don’t interfere if others get robbed … If I see criminals, I pretend I’m tying my shoelace.

This unique tactic not only helps Mabhuti to avoid danger, but also to preserve an expectation of strength and invulnerability that pervades the gendered mobilities of young men.

The young men amongst us make careful choices of dress and the goods they carry. Sandals are to be avoided according to our peer researchers in Cape Town, because they make it difficult to run if you must escape a dangerous situation in a hurry. Headwear also carries significance. As one peer researcher who identifies as a Rastafarian and wraps his hair in a rastacap affirms, ‘You can’t rob a rasta [in the study neighbourhood].’ Religious identity in this case means a great deal. Attention to dress is also important as we walk through London. Mohammad, a young man in his late 20s suggests that dress sense can help to ensure a safe walk. As he noted, ‘I don’t wear my long chain when I’m walking at night as that can attract some unwanted attention.’ Although walking with jewellery can be avoided, walking with a phone may be inevitable, but it is important to carry it in a secure place. Some question whether or not to carry a knife for protection, and all are cognisant of their choice of travel time and route, preferably along the shortest and most travelled route. Walking safely is also helped by paying attention to the streetscape ahead (and sometimes behind you), and always keeping an eye out for trouble, as Dwight reminds us along the way:

I’m looking forward when I’m walking … your eyes must be there before you!

While we may think of walking as a practice that primarily concerns the movements of our legs, our walks also call attention to the importance of verbal and non-verbal aspects of walking. Gangsterism is rife in some of the communities where our peer researchers reside. Some peer researchers found it useful to practise walking and talking like a gangster. A Cape Town peer researcher shows that he is ‘walking confidently so the skollies [thieves] won’t notice me’ while in London his counterpart points out that ‘I don’t face any challenges … since I was also a gangster’. Bodily comportment thus becomes one way to express confidence and masculinity, despite the fears and vulnerabilities that may be sensed. Many also suggest that walking with trusted others is both a tactic to ensure a safe walk, but also one that is enjoyable.

Walking with others

In the communities we explore, we often walk with others, in some cases out of concern for safety, but other times because the streets of these communities are vibrant spaces that exemplify the sociality of the city. In Cape Town, Swazi hints at the tensions as he escorts potentially vulnerable women home:

Today I am walking my daughter and her mother home as they had visited me the previous day. It is afternoon at around 1 o’clock and usually during this time of the day there would be a lot of people and kids playing around my street, but there is just two little girls playing with sand on the side of the road. I can see that they didn’t go to school today because the school is normally out at 2 o’clock. I can also tell by how dirty their legs are that they haven’t been to school … I don’t really know people from this section, just people I went to school with a long time ago. As I am walking in the open field that is between the houses, where most people that are going to a church nearby always walk, there are three young girls approaching us. They are probably at their early 20’s. I can see by the way they are dressing that they are going to church because they have their doek (head wrap) and skirts on. They stop and greet as they reach us, probably because they know my girlfriend. I then continue walking, leaving her behind because the bag I am carrying is a bit heavy. I am also rushing to get back home. After a few minutes, they catch up with me as I am getting close to where they live. After a 20 minutes walking, I then say my goodbyes with them and then turn back using the same direction I came in. I am walking a bit fast, faster than then pace I was walking in when I came this side because the road was clear and quiet with only one lady walking in front of. I can she is coming from Shoprite because of the plastic she is carrying. I quickly go pass her without even greeting. I hear a sound of dogs barking from a nearby house as I enter a street that leads to the passage that takes me to the main road. I am crossing the road to where I stay, and the scene is a bit different to what it is like one the side. Here the house are shacks and there is no proper infrastructure but on the other side houses are properly built and there are proper streets. I make a 5-minute walk from the road to my house without really seeing anyone, just avoiding flooding water on the street as it is wet.

Walking the streets of our study communities in Cape Town requires attention to unpredictable changes in the infrastructure and materiality of the city as Swazi’s reflection suggests. Blocked drains cause flooding on some streets while drain covers may be absent in others. This requires a careful eye to the ground while still scanning the streetscape ahead. This experience contrasts with that of our walks in London. One young man in his 20s reflects on how he navigates the streets of London:

I maintain awareness of my surroundings and follow pedestrian safety guidelines to ensure a smooth and safe walk. If I encounter any potential dangers, I adjust my route or seek assistance from nearby authorities or pedestrians.

Senses and sense-making (Middleton 2010) play an important role in daily walks. Attention to the environment, the infrastructure and others who are walking are all part of the routine. While senses are often attuned to danger, there are also moments of joy.

Finding joy in walking

Our walk is not only filled with fear and trepidation. We also find joy as we amble through the city. In recognising this we help to undermine conventional notions about walking for young men in low-income communities, especially for those captive to walking as a mobility practice. While walking may be physically taxing, and pedestrians may often endure long distances in poor weather and under threats of danger, there are often pleasures to be found. Our walk reveals the joys to be found in everyday encounters. In London there are children playing in the park, people walking dogs, other people laughing and having a good time. One peer researcher stumbles upon a lively fun fair. They note the enticing scent of a cooked breakfast wafting through a nearby window as they set off on their journey or pass through a street market that exudes the lively energy of the city. Even in the more uncertain context of Cape Town, another appreciates acknowledging and being acknowledged with a smile or greeting by others.

During our walk, peer researchers have highlighted social encounters of many kinds – all which point to the joys of encounter. Several reflections even mention how strangers sometimes go out of their way to help others, extending the notion of ‘care’ to our human geographies (Middleton & Samanani 2021) and an ethics of care within the neighbourhoods where our peer researchers reside (Porter et al. 2023a). This ethics of care aligns with our careful curatorial method (Fraser & Jim 2018) of writing differently as it enables findings that illustrate care in the experience of walking the city.

The joys we experience from walking are often unexpected but memorable as we recall previous journeys. Riyaaz remembers a particular journey from his home in London to a relative’s house. He recalls that:

… [t]he journey started on a pleasant note given that the sun was blazing but it was the cool breeze that accompanied the atmosphere. Walking along, I was captivated by the vibrant blooms of flowers adorning the front yards. As I walked along, enjoying the pleasant morning, I came across a talented street performer playing his violin. The street performer was playing a piece called Campanella on his violin, and it had been quite some time since I last heard it. I was completely captivated by the melody, lost in its enchanting notes. Unfortunately, my mesmerisation caused me to miss my bus. However, the music made my journey far more enjoyable.

The experiences of young men in our collective have helped us to recognise not only the financial advantage of walking, but also the benefits of walking for both physical and mental health. Peer researchers and members of their communities tell us that they appreciate how walking helps the respiratory system, even that it is a ‘sort of meditation to get peace of mind’. Josh in London comments how he ‘love[s] walking, it keeps me fit and I enjoy the outdoors, it clears my mind I often walk to nearby stores, parks …’. His counterpart in Cape Town reflects that by walking:

I get to breathe fresh air, instead of just sitting in the house and be thinking about being unemployed and stuff. I get to see people and be healed.

Tago, a 28-year-old man in Cape Town, appreciates how walking can help him and his pregnant partner to find relief:

I love walking and my girlfriend also love walking. She says that her doctor told her to take some walks when she can because it will make her feel much better. Walking also help me to cool down because I am very stressing now because I don’t have a job and my girlfriend is pregnant. But I know my God will provide.

The pleasures of walking extend to the encounters that young men may have at the travel hubs to which they travel. By walking they are able to experience familiar faces, as Amos in London relates:

Today the walk felt different but in a surprising way, it was more relaxing than normal … the walk was about 10 minutes and I didn’t have my AirPods in ever so I was listening to the sounds of the wind, cars and people talking throughout my journey.

…

I then carried on my walk after waiting for the traffic light to turn green and walked about another 5 minutes to work, I saw a couple people I knew along the way so that was quite nice being able to have some morning social interaction with familiar faces even just by me waving or smiling.

The joys of walking remind us that encountering the city on foot, even if it may be the only option, holds the potential for positive benefits, in terms of physical and mental health, social cohesion and environmental impact. Walking also provides a unique way of knowing the city one inhabits, and importantly where power rests. Walking helps to unlock the ‘relationship between mind, body and [place]’ (Muecke & Eadie 2020, p. 1205), and ultimately allows us all to walk out of our disciplinary framework which both guides and limits us. As we near the end of our walk, we take the last steps to help effect meaningful and long-lasting change by ‘talking’ our walk to those in powerful positions.

Walking for impact

Our walk ends metaphorically at the heart of the city. Our walk has traced a journey from the homes of our peer researchers and their fellow community members to the centre; from low-income communities on the periphery to the seat of power. We have done this based on a methodology that was first developed and tested in the context of the Global South – testing it in this case within the context of the Global North. When we set out on our collaborative journey we sought to ensure to the best of our abilities that our research might have impacts beyond academia. Traditionally, the research work that we do speaks back to other scholarly outputs, by framing the research in a literature review and contributing back to the debates therein. The scholars amongst us, whose work is focused on research and teaching, still endeavour to do this. However, we intend to offer something different.

Our walk is a propositional hybrid (Springgay & Truman 2018) comprised of the actuality of walking journeys and their potential for meaningful change. Our proposition lies not only in our shared concern to explore the experiences of walking from home to transit hubs in the neighbourhoods where our peer researchers live, but also in creating impact beyond academia. Our ‘walking-with’ not only refers to the sociability of walking with others; it also highlights our accountability to indigenous/local knowledge and ways of being in the world (Sundberg 2014). Inspired by the Zapatista movements in the early 2000s, walking-with demonstrates ‘respect for the multiplicity of life worlds’ (Sundberg 2014, p. 40) as we have attempted through our curated walk.

The last ‘steps’ of our walk entail sharing the life worlds of our peer researchers directly with stakeholders within the local governance structures of our respective sites of enquiry. Beyond the traditional academic journal article, our project has been designed to ‘write’ research into the discourse of public policy through stakeholder engagement workshops. These workshops were held both in Cape Town and London – the former with members of the city’s Urban Mobility Directorate, community activists and researchers; and the latter with representatives from local councils within which peer researchers reside, community safety and Transport for London officials, and local public transportation providers.

These stakeholder workshops formed an important element in our project design. The workshops in each city provided peer researchers and other members of the project team the opportunity to meet with relevant local stakeholders including community youth organisations, informal transport associations, transport companies, NGOs, local government, unions, law enforcement organisations, amongst others to discuss the potential implications of project findings for further action, policy, and practice. The potential impacts on policy or practice are not prescribed by us, but are intended to emerge through the process of engagement. Potential actions in response might include increased safety measures, attention to walking infrastructure, or policies directed toward enabling more safe and enjoyable walking journeys, amongst others.

Looking back

There were times during our walk where we took an opportunity to look back upon the steps that we had made. These reflections helped us to assess the aim of our walking-writing practice – in terms of testing the applicability of the peer research method across Global North/South contexts, as well as on effecting meaningful change. While we have found valuable insights across the two cities, a key challenge in London was in the recruitment of peer researchers. Although community institutions in Cape Town yielded a large number of potential peer researchers, recruitment in London proved challenging. Whether due to broad scepticism of the project, fear of scams, or the availability of other opportunities, recruitment in London required considerably more effort. High unemployment rates and dense networks of community organisations with ties to Cape Town’s communities in question meant that young men were eager for the opportunity to take part, learn new skills, provide their knowledge and help to effect change. In our post-stakeholder interviews with peer researchers, many noted a feeling of empowerment in telling their stories directly to those in positions of power and influence. Reading excerpts from their mobility diaries validated the experience of walking in their communities. In the post-walk discussion in London, one peer researcher mentioned community members enjoying being interviewed. Their satisfaction came from sharing stories of their daily lives – something they do not normally have an opportunity to do, and a sign of respect for their knowledge and insights from daily experiences. This is ‘walking-with’ in its true sense. The same can be said for discussions with peer researchers in Cape Town, as they valued the opportunity to share their life worlds directly to city officials, literally speaking truth to power. By foregrounding peer researchers’ voices in stakeholder workshops, we helped to turn the tables on knowledge production and dissemination, giving space for peer researchers to lead the research in an important way, and to help enact meaningful change through presenting findings directly to those charged with policy making.

Our curated walk helped to trace the research journey that we have taken together from the homes of those involved to the metaphorical centre of power in the cities/regions where our work takes place. Our aim was to ‘walk-with’ our peer researchers through a propositional activity, inspired by Springgay and Truman (2018, p. 130), highlighting the actuality of our embodied, sensory walks with their potentiality to effect change. Through our collaborations we underscore both the sociability of walking-with peer researchers and their communities, but also our accountability to each other. While achievement of long-term, meaningful impacts from our project are still forthcoming, our contribution to writing research differently can be seen in the walk we have taken together. Enacting policy change takes time. What we have achieved is a journey toward change, mapping a collaborative process of listening, co-creating and sharing knowledge from the starting point of the homes of our peer researchers and fellow members of their communities to the metaphorical ‘centre’ of the city. In our efforts to take this walk together, we have demonstrated how long-term, meaningful impacts might take shape.

Acknowledgement

We wish to acknowledge peer researchers and fellow community members for their contributions to this work. While some remain anonymous for ethical reasons, the project would not have been possible without their knowledge and efforts.

References

Belkouri, D, Lanng, DB & Laing, R 2022, ‘Being there: Capturing and conveying noisy slices of walking in the city’, Mobilities, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 914–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2022.2045871

Benton, JS, Jennings, G, Walker, J & Evans, J 2023, ‘”Walking is our asset”: How to retain walking as a valued mode of transport in African cities’, Cities, vol. 137, 104297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104297

Burke, E, le May, A, Kébé, F, Flink, I & van Reeuwijk, M 2019, ‘Experiences of being, and working with, young people with disabilities as peer researchers in Senegal: The impact on data quality, analysis, and well-being’, Qualitative Social Work, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 583–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325018763515

Devotta, K, Woodhall-Melnik, J, Pedersen, C, Wendaferew, A, Dowbor, TP, Guilcher, SJ, Hamilton-Wright, S, Ferentzy, P, Hwang, SW & Matheson, FI 2016, ‘Enriching qualitative research by engaging peer interviewers: A case study’, Qualitative Research, vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 661–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115626244

Fraser, M & Jim, A 2018, ‘Introduction: What is critical curating?’, Canadian Art Review, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 5–10. https://doi.org/10.7202/1054378ar

Huchzermeyer, M & Karam, A 2006, Informal settlements: A perpetual challenge? UCT Press, Cape Town.

Lorimer, H 2016, ‘Walking: New forms and spaces for studies of pedestrianism’, in T Cresswell & P Merriman (eds), Geographies of mobilities: Practices, spaces, subjects, Routledge, London, pp. 19–33. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315584393

Mabin, A & Smit, D 1997, ‘Reconstructing South Africa’s cities? The making of urban planning 1900–2000’, Planning Perspectives, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 193–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/026654397364726

Middleton, J 2010, ‘Sense and the city: Exploring the embodied geographies of urban walking’, Social & Cultural Geography, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 575–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2010.497913

Middleton, J & Samanani, F 2021, ‘Accounting for care within human geography’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12403

Mosavel, M, Ahmed, R, Daniels, D & Simon, C 2011, ‘Community researchers conducting health disparities research: Ethical and other insights from fieldwork journaling’, Social Science & Medicine, vol. 73, no. 1, pp. 145–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.029

Muecke, S & Eadie, J 2020, ‘Ways of life: Knowledge transfer and Aboriginal heritage trails’, Educational Philosophy and Theory, vol. 52, no. 11, pp. 1201–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1752185

Porter, G 2016, ‘Reflections on co-investigation through peer research with young people and older people in sub-Saharan Africa’, Qualitative Research, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115619001

Porter, G, Dungey, C, Murphy, E, Adamu, F, Bitrus Dayil, P & de Lannoy, A 2023a, ‘Everyday mobility practices and the ethics of care: Young women’s reflections on social responsibility in the time of COVID-19 in three African cities’, Mobilities, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2022.2039561

Porter, G, Dungey, C, Akoshi, M, Bullus, PH, Houiji, R, Matomane, S, Mohammed, AU, Mohammed, H, Nasser, AIMW & Usman, UN 2023b, ‘Peer research, power and ethics: Navigating participatory research in an Africa-focused mobilities study before and during COVID-19’, in B Percy-Smith, NP Thomas, C O’Kane & AT-D Imoh (eds), A handbook of children and young people’s participation: Conversations for transformational change, Routledge, London, pp. 140–6. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003367758

Reilly, M 2010, ‘Curating transnational feminisms’, Feminist Studies, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 156–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40608006

Rink, B 2020, ‘Mobilizing theory through practice: Authentic learning in teaching mobilities’, Journal of Geography in Higher Education, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 108–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2019.1695107

Sagaris, L, Costa-Roldan, I, Rimbaud, A & Jennings, G 2022, Walking, the invisible transport mode?, Report for the Volvo Research and Educational Foundation.

Springgay, S & Truman, SE 2018, Walking methodologies in a more-than-human world: WalkingLab, Routledge, London, UK.

Sundberg, J 2014, ‘Decolonizing posthumanist geographies’, Cultural Geographies, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474013486067

Vergunst, J 2010, ‘Rhythms of walking: History and presence in a city street’, Space and Culture, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 376–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331210374145

Watts, L & Urry, J 2008, ‘Moving methods, travelling times’, Environment and Planning D: Society & Space, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 860–74. https://doi.org/10.1068/d6707

Yang, C & Dibb, Z 2020, Peer Research in the UK, Working Paper, Institute for Community Studies.