Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 18, No. 1

January 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE (PEER REVIEWED)

Experimenting with Twilight Learnings and Twilight Writings for Community Engagement

Silvia Mugnaini1, Åsa Ståhl2 and Leah Ireland3

1 Education and Psychology Department, University of Florence, Italy

2 Design Department, Linnaeus University, Sweden

3 Independent author, Feminist Farmers/VXO Farm Lab, Sweden

Corresponding author: Silvia Mugnaini, silvia.mugnaini@unifi.it

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v18i1.9209

Article History: Received 30/06/2024; Revised 30/10/2024; Accepted 05/11/2024; Published 01/2025

Abstract

This contribution explores community engagement through the collaborative practice ‘Twilight Learnings – Seasonal experiments in the Tiny House on Wheels (THoW)’. In this article, we show that a reflective community can start to emerge through sharing experiences and knowledges in a confined space that is simultaneously connected to society in a fractal scaling (O’Brien et al. 2023) way. Some of the participants grew so fond of reflecting together on hope, allies, uncertainties, pain and frustrations, that they continued to build the community by articulating themselves through follow-up interviews and through writing together in different ways.

We document hidden and ‘marginal’ stages of a research process allowing longer timeframes so that practitioners and scholars can write together in a slow science (Stengers 2018) approach. This article mainly explores three aspects of community engagement: 1) reporting on community-based research and practice and reflective experiences in a workshop in the THoW; 2) reflecting on collective writing processes through performative writing; 3) meta-reflecting on scaling and performativity. In other words, this article contributes to how knowledge production and world-making can go together through community engagement that extends into writing.

Keywords

Social Economy; Participatory Design; Collaborative Knowledge Production;

World-Making; Emerging Communities; Co-Writing

Introduction

Let us invite you directly into the structure of this article. After stepping into a particular Tiny House on Wheels (THoW) (Section 1), we examine our position on knowing and making worlds (Section 2) to contextualise the reporting of our joint experience in the THoW (Section 3), before joining our main concepts of community engagement and knowledge co-production and our empirical material on social economy and change work (Section 4). Finally, we conclude the article with a reflection on community writing (Section 5).

The purpose of this writing and collaborative knowledge production is to investigate, report and elaborate on capacities needed to enable sustainability transformations within and beyond the article format.

An invitation to a Tiny House on Wheels

You are welcome to peek into the THoW through the windows. There are two on one side and three on the other. However, it is easier to connect with it if you walk up the three steps (Figure 1). What makes you curious to walk through the door frame? What do you smell? What do you hear? What do you see? What do you feel when you get closer to the stove where water is boiling for tea? What openings for community-building can be created here?

Figure 1. Stepping into the THoW. Photo: Åsa Ståhl

When we step into the THoW, we walk into a mobile house built by Stephan Hruza as part of the Formas-funded research project Holding Surplus House. The THoW is a mobile house that constitutes the research setting for exploring transformative practices and imaginaries of eco-socially just householding with resources. With this experimental platform we are inviting participants, sometimes broadly and sometimes exclusively, to create relationships in a household that we conceptualise as a social dynamic entity that finds the differences between all involved actors as generative (Raven et al. 2021). We acknowledge not only humans as householders but also more-than-human actors. We use it as a site for the experimentation of householding with resources. This includes asking the following questions. What is a resource? How is it valued? How can it be distributed fairly? We take a holistic approach by integrating the ecological, economic, social and cultural aspects of householding, drawing on the roots of oikos where economy and ecology come together in the home (Gibson, Bird Rose & Fincher 2015).

In the building process of the THoW, we decided to emphasise processes of becoming in relationships, collaborations, vulnerability, and incompleteness rather than striving for or enacting the house as a finished piece for self-sufficient living that would invite humans to imagine living off-grid. For example, the Seasonal Clothing experiments (Figure 2) show how the THoW can be understood as being relative, as an entity that is not discrete but rather changes with seasons, sites, contexts and actors over time.

Figure 2. Holding Surplus House designing for Seasonal Clothing in 2024. Photo: Åsa Ståhl

Twilight Learnings

In this article, we focus on ‘Twilight Learnings – Seasonal Experiments in the Tiny House on Wheels’. The gathering focuses on the idea of not trying to escape the dark season, but rather living with and embracing the strengths of the Swedish winter season, emphasising rest and reflection. The case builds on a collaborative practice between Silvia Mugnaini, a doctoral student in Education Sciences and Psychology at Florence University (Italy), who was visiting the Design Department of Linnaeus University (Sweden) during the autumn and winter of 2023, and Åsa Ståhl, a senior lecturer in design at Linnaeus University.

At the time of the winter solstice, we invited colleagues and local people on and beyond campus to a curated workshop aimed at building inner capacities for transformation within social economy organisations. Social economy organisations represent the seeds of a radically different economy as they put people over profit and reinvest surplus into economic and social objectives (UNTFSSE 2022). Inner capacities and associated internal dimensions (values, beliefs, worldviews/ paradigms) are seen as a deep leverage point for change, as they tackle the internal mental states (e.g. consumerism, racism, elitism, injustice) which are the root causes of climate change and interlinked crises (e.g. health, poverty) (Wamsler, Hertog & Di Paola 2021). In other words, it is essential to develop a quality of agency which entails an approach to scaling sustainability transformations. O’Brien at al. (2023) describe such an approach as that which can generate fractal-like patterns of sustainability which recursively repeat at all scales, enacting universal values, to create a world where people and the planet can thrive.

From a methodological point of view, the workshop was designed as a learning arena to enable reflexivity (Augenstein et al. 2020) allowing for reflection on ways of organising for sustainability transformations. First, participants presented their organisations (The Feminist Farmers/ VXO FARMLab, Smålands Trädgård and Macken) and the sustainability initiatives they carry out (collective farming, co-working, repurposing and social integration). The discussion was then structured into different rounds based on areas of sustainability that included questions such as what values, governance models, inner capacities, collaborations, narratives and economic and environmental dimensions enable or inhibit the development and implementation of sustainability initiatives. We attempted to enhance the embeddedness of personal experience in an exploration that connects the individual and the local context to global sustainability issues, and back, to strengthen participants’ agency. Although we had a framework for our invitation, we allowed the situation not to be fully controlled.

The Twilight Learnings was also an occasion to draw on elders’ practices of taking a momentary pause in the working day at the time of dusk to Kura Skymning, which can be explained as a way of marking the difference between more outward actions during the daylight and the evening chores as the day turns to night. As a practice, our Kura Skymning involves sitting together, dreaming, integrating and sharing insights on the challenges and joys of change work (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Twilight Learnings – Seasonal experiments in the THoW. Photo: Åsa Ståhl

Furthermore, the workshop was a way to discuss and reflect on community engagement and an experiment in common knowledge production. As a way of working in continuous reflection, we invited our participants to take part in the process of writing this article. As a result, Leah Ireland, who attended the workshop, with her experience from The Feminist Farmers/ VXO FARMLab, has become the third author of this article.

In terms of the method for generating material for this article, Mugnaini and Ståhl made direct and open invitations, structured the workshop with five participants, and noted the need for agile adjustments as hosts throughout the session. In a later stage, the two invited the participants to co-write the article via an open document accessible to all participants. The article has thus been available since January 2024 and has been growing in size with the input of participants. We also followed up with discussions over Zoom with three participants based on questions we had prepared in advance. Oral and email contributions in the form of ideas, comments and reflections appear here in both named and anonymous forms according to the preferences of the participants. Just as the THoW acts as an experimental space, becoming with and through participation, this article reflects these values through this collective writing process and communal production of knowledge.

Knowing and making worlds: Different kinds of research make different kinds of worlds

How one does research makes different worlds (Watts 2021). This means that we are not only noticing and trying to know the world, we also recognise that we are part of making the world. Since we work from an ontology of being in relationships and from a situated knowledge approach (Haraway 1988), we, the main authors, will examine our position on knowing and making worlds.

Mugnaini and Ståhl have long experience working in participatory processes where many epistemic communities come together with their different languages, preconceptions, expectations and more. Mugnaini has a background in economic development; Ståhl as a journalist, an artist and a design researcher; and Leah Ireland as a designer and practitioner in socially engaged organisations. We have all, in other contexts, created formal and informal learning experiences and share a commitment to inquiring into and suggesting transitions that combine social and ecological justice, including economic relationships.

Given these diverse backgrounds, we come together for an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary work bridging different research areas, predominantly sustainability transitions research (Hölscher, Wittmayer & Loorbach 2018), adult and transformative educational research (Federighi 2018) and participatory design with a focus on caring design experiments (Lindström & Ståhl 2019).

When actors from different epistemic and practice communities come together, it is unlikely that there will be a full concurrence of ontologies, epistemologies, methodologies or ethics. In that sense, this article also functions as a boundary object (Star & Griesemer 1989) bridging scientific disciplines with practice by highlighting place-based societal changes driven by local actors (Lam et al. 2020) and considering how these contribute to transformative change. Understanding that there are many ways of knowing the world and that everyone involved has a contribution to make, the development and implementation of sustainability initiatives by local actors provides new indispensable ways of thinking, doing and organising (Lam et al. 2020). With this in mind, local sustainability initiatives are potential solutions to sustainability problems with global relevance (Lam et al. 2020).

It is imperative to be aware of the dominant scientific paradigm that embraces the nearly universally accepted ideologies of empiricism, reductionism, positivism and progress within modern science (Ives et al. 2023), particularly since it has influenced sustainability transformation research, predominantly led by researchers in the Global North, who often adopt technocratic paradigms with Western perspectives, mindsets and values. Research methods also carry contingent and historically specific Euro-American assumptions about what we must do when we investigate (Law 2004). However, the unprecedented challenges posed by socio-ecological crises call for the integration of diverse forms of knowledge and perspectives – including those held by many wisdom communities (Ives et al. 2023). Furthermore, there is a need to expand the systems and processes that determine how knowledge is produced, revealed, negotiated, transmitted and incorporated into sustainability practice (Ives et al. 2023). The same authors stress that knowledge co-creation necessitates the development of cultures of care and compassion among researchers and practitioners. They also list what knowledge production requires including:

1. fostering collaboration, based on close and respectful interactions, aimed at co-producing knowledge that includes the perspectives of local and marginalised groups;

2. representing an experiential process in which change is interpreted from an embodied and relational perspective, rather than from detached, observational approaches that are characteristic of Western science. This also entails an openness to not knowing. In this sense, inner–outer transformation is also about decolonising current methods and approaches;

3. reflexivity, as a way of acknowledging one’s positionality as a researcher or practitioner;

4. empowering individuals involved in knowledge production to develop inner capacities to drive change at individual, collective and systemic levels.

In our joint experiment with Twilight Learnings in the THoW, we took these four points into practice, as shown in the following examples. Firstly, we established a collective research practice (Gibson-Graham 2008) working across differences with non-academic as well as academic subjects and contexts, which leads to what Tsing (2015) would describe as contamination or ‘transformation through encounter’ (Tsing 2015, p. 28). Working co-creatively with other stakeholders is an important methodological aspect of this article in which we collected stories of change working with people who were already making new worlds: The Feminist Farmers/VXO FARMLab, Macken, and Smålands Trädgård. Secondly, we experientially co-produced knowledge through the means of a situated activity (Semeraro 2014). As researchers, we are building knowledge together with others, and the interpretation of data by participants is essential and influential, never accidental. In other words, knowledge becomes and emerges together with specific actors sometimes expressed as embodied knowledge in the form of capacities, skills and narratives. The knowledge is thus situated, connected and thereby robust while at the same time able to travel and become meaningful elsewhere.

It is this vulnerability, strangeness, imperfection and awkwardness of the hybrid that makes the research strategy resilient, opening up the researcher to many ways of relating, participating, and contributing (Tham, Ståhl & Hyltén-Cavallius 2019).

Thirdly, as academics we recognise ourselves as engaged scholars (DiSalvo 2022) and scholar activists (Gibson-Graham 2008) informed by the Community Economies research programme. In a nutshell, Community Economies research how academic practices can contribute to the exciting proliferation of economic experiments occurring worldwide at the current moment (Gibson-Graham 2008). Accordingly, we have embraced an experimental attitude towards the objects of our research (Gibson-Graham 2008) by designing the Twilight Learnings as a space to understand the participants’ strategies to promote change, support their efforts to learn from their experience and help them find ways of changing what they wished to change. This experimental approach to research is characterised by an interest in learning rather than critically assessing the ways in which the object of the research is good or bad (Gibson-Graham 2008).

Thus, in this science-practice collaboration, we have reflected on how we can use our position as academics to make space for the research process itself to be a learning experience that enlarges the inner capacities of the persons involved, making it durable over time while uncovering already existing processes of transformative change. Consequently, we have followed Augenstein et al.’s (2020) suggestion that researchers engaged in inter- and transdisciplinary research collaborations should be sensitive to epistemic plurality, work explicitly with boundary objects and adopt novel forms of facilitating knowledge integration as a fundamental element of research projects. To reiterate, this means that the approaches we draw on emphasise the role of experimentation, acknowledging the value of learning rather than adhering to short-sighted solutionism.

The emphasis on learning resonates with the notion of ‘scaling deep’ (Moore, Riddell & Vocisano 2015); that is, a process of impacting cultural roots to build durable change. Scaling deep is based on reframing stories to change beliefs and norms and intensively share knowledge and new practices via learning communities.

Scaling deep also resonates with the concept of ‘fractal scaling’ (O’Brien et al. 2023). Social fractals are self-similar patterns produced by individuals through conscious agency. These human and social fractals embody values that manifest consistently across various scales. When our actions align with values that pertain to the whole, they generate new patterns that are replicated through language, narratives and meaning-making at all levels, with each part and whole reflecting those qualities. Consequently, every action has the potential to create an interconnected quantum fractal, a pattern that recurs non-locally across all scales (O’Brien et al. 2023). Fractal scaling can thus be understood to always be local, but also able to expand beyond the local.

We find it generative to have several ways of understanding scale, particularly against the dominant discourse of bigger, linear, growth-based examples of scales, since hyperlocal experimentation is often put to the test and measured against these.

Finally, in this article we attempt to ‘describe things that are complex, diffuse and messy’ (Law 2004, p. 2) as one can see in section 3. Examples of this ‘mess’ are, for instance, emotions such as pain, hope, intuition, losses, mundanities and visions, unpredictabilities, vulnerabilities, fears and betrayals; that is, forms of knowing through one’s senses and emotions that are rarely caught by social science methods. For this reason, the results section is not ‘the kind of summing up that has become the hallmark of modern knowledge’ (Tsing 2015). Rather, it is a ‘rush of troubled stories’ (Tsing 2015) that pays respect to the diversity emerging from our encounter-based collaboration. In reporting data, we reflect on the words of Lenz Taguchi (2018) on the inter-connectedness and companionship with various bodies (fellow researchers, data, places and spaces) within a collective researcher assemblage. Lenz Taguchi (2018) highlights the dynamic tension between the enjoyment derived from deeply engaging with data and the sense of violation encountered in its analysis. Therefore, we give space to community-based expertise and voices along with our disciplinary-based expertise, including transcribed quotes from the Twilight Learnings and follow-up conversations as a way to share the participants’ own experiences. We have organised the troubled stories thematically.

Reporting troubled stories of community engagement in the THoW

Posters of Twilight Learnings and the Kura Skymning, as a joint reflection and a resting opportunity, were spread on notice boards on campus, and digitally, through social media and a staff mailing list to Mugnaini’s and Ståhl’s colleagues. We also reached out to some people and their organisations directly as we were specifically curious to learn with them.

The starting time had been scheduled in the afternoon when it was still rather light. Leah Ireland says that her first memory in hindsight is that of trying to intercept people moving around the house, to direct them to the right place. We were scattered and trying to assemble in the THoW.

A couple of participants expressed nervous anticipation of the unknown before entering the THoW, regarding who they would meet, what would the place be like and how it would all pan out, as highlighted in online follow-up meetings six months later.

Seven people eventually entered. A fire in the woodstove filled the place with warmth and steam contrasting with the temperature and cold wind outdoors. The participants arrived with different experiences as well as knowledges. Most participants were acquainted with at least two others; some knew each other through Linnaeus University as former students, administrative staff or in teaching and research positions. One participant reported afterwards that it felt empowering that it was mostly women and a mix of ages. Everyone was invited to partake in fika – a mundane Swedish cultural ritual of gathering around sweets or savouries – this time with homemade chocolate balls and Italian apple pie, mass-produced seasonal gingerbread, tea and coffee (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Swedish ritual Fika with homemade and bought pastries. Photo: Åsa Ståhl

No one seemed to dare to start eating. Fika was set on the centrally located table and there were tiny covers and pillows to allow people to sit comfortably. In the words of one participant, it was ritually both simple and generous. In contrast to the hesitation, everyone was paradoxically rather relaxed and informal in attitude and the way they approached each other. There was closeness since the size of the THoW made the space intimate as pointed out in one of the follow-up meetings. One of the participants said that there was something delicate and childish in the space, and that it was an experience of care.

Participants were guided by questions in a conversation on harnessing, what one participant called, ‘a momentum for change’. This could be understood as a time and a place where we had the individual and collective ability to practice change work, communicate stories of change and activate people to collectively transform our current sociocultural economic system, building one that is collaboratively imagined with deliberation. In the Twilight Learnings session, through our communal presence in the THoW, the experience was that the aggregated embodied knowledges that had accumulated in particular situations in other times and spaces made it possible to cross boundaries while sitting together. In entering a confined space, we created room for reflection that connected with the broader society and related it to our work, sharing and gaining knowledge. This double-movement was emphasised by several participants: the THoW was embracing and intimate, while at the same time opening up for an expanded presence.

Culture, norms, and values, that enable or inhibit sustainability initiatives

Value frictions emerged, not so much between the participants themselves but in relation to institutionalised norms that they had encountered as they were pursuing their visions and trying to make the world in accordance with their ideas. An enabling factor identified by participants was knowing how to use communication strategies such as marketing and branding. This is one of the themes that emerged as divisive in participants’ perceptions:

(Mariana Gómez Johannesson): I think it is interesting to understand how we sell these tiny ideas. It is an issue of marketing at the end of the day.

(Leah Ireland): I thought it was so funny that you mentioned this marketing thing [...] because this is something we found so frustrating [...] we were trying to get business advice [from a consultancy service on cooperatives and the] reflection on our idea was that it was so cool, so great that we have branded ourselves with the feminist farmers because it was such a hot topic right now and we were so pissed off that he would say it is so fashionable to think and work with feminism. So, it was really good for us and our brand because we could sell whatever we were doing. But we had no real understanding of what we were doing. But when you are thinking of this idea of marketing and working also with these kinds of values and so on and then you enter in some sticky world where I have people saying, ‘oh you are very good with branding’ and I was ‘ohwn… (makes a sound of throwing up)’ that’s so not where I stand.

(Stephan Hruza): Most of the social companies are driven by many idealists having good ideas and they do not want to, it is not about selling but at the same time to survive you need to sell, at the end you are so dependent on this system.

In hearing how the participants cued each other in sharing, we observed that connections were made in many ways. One participant said that despite differences such as age, working experience and type of responsibilities, they interpreted the discussion and body postures as signs that participants were feeling that they were listened to without judgment of each others’ struggles. When digesting the conversation, it is noticeable that it led to reconnecting with the past, tracing stories and connecting with people’s thoughts, experiences and feelings. The present was performed as an exploration of what had been and what if – a kind of daydreaming while listening carefully. While change practices were different, common frustrations were shared. Sharing these frustrations felt almost like a cathartic experience, one participant said, because one could understand and gain perspective on the experiences and transformations of the other participants as well as on how funding or other structures affect projects.

Governance models that enable or inhibit sustainability initiatives

There were stories shared about how systems can be challenged but projects can also lose momentum, fall apart or need to transform. Through the sharing, the participants could also notice repetitive patterns: entrepreneurial effort starting with an energetic person trying to apply their ideas in a specific context. Then it becomes tricky – entangled – and the energy may go out, momentums falter, funding gets lost, or other greater structures block the work. Different statements capture this:

[unpredictabilities] (Leah Ireland): It was a passion project, [...] but then they needed a sort of authority of the land so they pushed us to find a way of organising ourselves and facilitating the area but we were all full-time students from different parts of the world so we decided to form a new ekonomisk förening (economic association) called VXO FARM Lab and that is still running so the Feminist Farmers has slowly ended and VXO FARM Lab has taken over facilitation of this area.

[pains] (Stephan Hruza): The thing is that I remember this frustration that you really feel that it is such a good idea and thing and something that should continue exists and at the same time you are feeling that this is not doable, [...] we questioned ‘how can we survive?’ Or not survive? [...]But at the same time there are so many nice people you meet and you really make a difference for them and there are so many good things happening but at the same time you can’t do it. You can do it for some years and then either you go to the wall or you have to quit before doing that. At least it wasn’t for me.

[betrayals](Mariana Gómez Johannesson): So of course you are happy, or I felt happy to see people feeling good and this woman reporting on people of feeling of use (you can call it like that) and at the same time they broke my heart to see they basically took everything we said, we worked on, we were doing, and it cost a lot of suffering for many people, and then again the suffering is also different, so it is tough in that way, but amazing people keep happening so in that way you put it in the balance, which you have to and then someone else is good because of this people, it’s great.

The dominant value frictions and greater challenges that emerged in the conversation apparently come from working with these transformative projects within certain societal structures. Across the Twilight Learnings and follow-up meetings with participants, it has been articulated that it is not always easy to work in rigid systems, following rules and laws that are at times contradictory, when one works with place-based societal initiatives that cater to the basic needs of citizens. This can be seen by noticing how there is competition from publicly funded initiatives and laws that are holding back innovation while at the same time seeing that you are prohibited from doing things by law that are allowed in other European countries.

(Mariana Gómez Johannesson): The things that they are doing are so basic and simple, they are so beneficial, but still, we have to follow laws and rules and systems and it is such a contradictory sort of feeling that ‘how can things not be easier?’

The Twilight Learnings built a feeling of belonging, one participant said. As authors, we also saw that the participants gifted each other with experiences in the form of stories. The contributions of experiences through stories demonstrated that one is not alone – more people could do these things together. Our situated definition of co-presence, in this article, thus builds on how there was a bridging of the physical co-presence created by the setting, atmosphere and proximity of participants in the THoW. Furthermore, co-presence was manifested by participants keenly listening and connecting with each other’s practices, wins and struggles. In addition, the participants expressed that co-presence is desirable and a key ingredient to harness this larger momentum for change. From the scale of the THoW to the scale of the larger organisations we brought with us into the THoW, the discussion touched upon the challenges of keeping up momentum and of negotiating co-presence between larger groups of people working towards a goal. Therefore, we extended our definition to recognise the necessity of negotiating expanded co-presence with larger, shifting groups and managing momentums that are mutable.

Personal capacities that enable or inhibit sustainability initiatives

The social economy is also full of diverse interests and it demands an entrepreneurial and economic mindset as suggested by an attendee. The work of convincing people and sharing inspiring examples and stories that resonate, are also ways of acknowledging that you are part of something greater within society and can function as a cross-learning opportunity.

(Mariana Gómez Johannesson): I know a lot of people felt that we failed – but I’m like: without this, this other thing wouldn’t have happened so you have contributed and that gives you hope because from there someone else built, learnt something. And people who work in the social economy should remind themselves of these small steps and how they have contributed.

(anonymous): From a personal perspective, you have to experience some wins when trying to practice and reaching out and you also have to be able to handle losing to be able to pick up the courage to try again.

(Leah Ireland): I learnt a lot of how to come to terms with certain outcomes and to let go of - not control but... the outcome – when I heard how things ended with Macken, how they moved on, it helped me get a bit of distance from my self and from my work – I think I needed that quite a lot actually.

Despite the value frictions identified in the system and the frustrations one had to endure, several participants articulated that the setting in the THoW generated hope, since it showed that there are, in one of the participants’ words, ‘beautiful minds out there and they are doing things’. The same participant continued: ‘We got to share and to understand that people are so active and are so revolutionary and are ready to really dig in.’

Collaborations that enable or inhibit sustainability initiatives

But how do we, then, further support this important work? Based on lived experiences and references for making change, such as collective work in cooperatives and activism, an answer turns out to be: making allies, and in the long run, getting organised. A participant told the others about actively seeking a place for change.

[Hope] (anonymous): I moved there to find momentum for the change we need to make. I didn’t really find that feeling of ‘oh it’s on, it’s going somewhere, people are talking about it, they are looking forward to something new’ so I was like ‘okay. I have to start creating it if i can’t find it, try to find people to possibly do things with’.

[inclination] (anonymous): We need to create this wave of people willing to work with us and understand how important this is. We had this idea of workation but I can’t do this alone. I need people who believe in it enough, and enough people or organisations that want to create a meeting space in the countryside.

Through these exchanges and additions to everyone’s repertoire of experiences, it is evident that things can be done differently. Social economy and various entrepreneurial organisations can be part of building resilient societies through community engagements that invite negotiations of power and distribution of resources, such as material waste and marginalisation, without asking for distanced solutions. Organisation is pointed out as connected to involvement:

(Stephan Hruza): This way of working together, being part of decision making, having these common goals that everybody thinks are good creates this engagement.

Or, as another participant explained it: ‘We have a goal and the goal is not earning money, the goal is helping as many as possible and I think this is what creates engagement.’

Pulling people in requires the mobilisation of a specific mindset and individual and collective capacities.

(Mariana Gómez Johannesson): You are whole yourself. So, when we start talking to people now I am talking to you as a parent, as a politician, as a society member, as a decision maker, as a man…so you need to call to these (identities) as close as possible.

(anonymous): When you are meeting people you can just try to see their core values and see where to meet each other, and actually learn about each other, you need to learn about those core values if you want to innovate something together.

(anonymous): Make people identify with the need to see how it should be done. Approach the other people from their perspective.

(Mariana Gómez Johannesson): You have to adapt the storytelling. It is a dance. In each of these scopes you need ambassadors. And this is why this narrative is so important. But I don’t go and talk to a company and tell things in the way I would sell it to the municipality. I would need to talk their talk. And then make sure that at least one person would be so in love with what I’m representing and with the idea. So, ambassadorship is crucial.

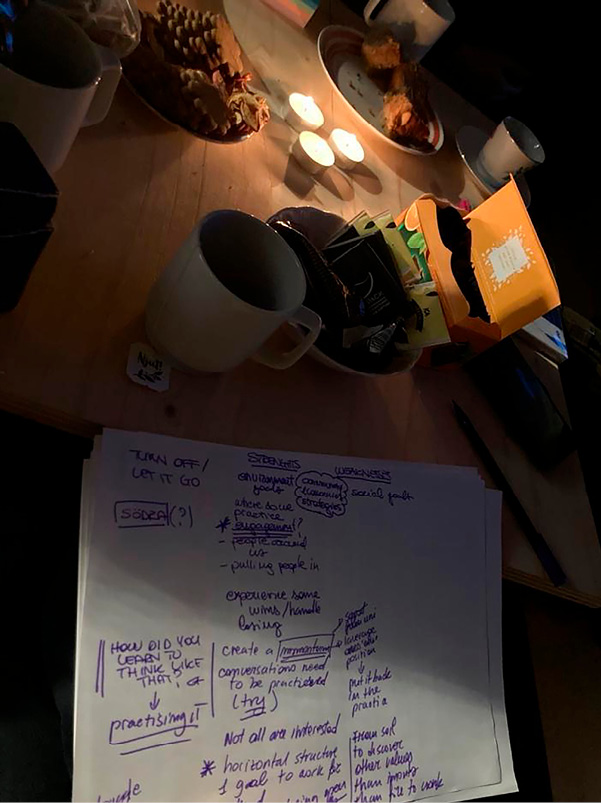

The Twilight Learnings had a couple of different endings. One of them occurred when Silvia Mugnaini summed up the discussion (Figure 5). The summary was a way to signal an ending and offer a sense of conclusion, to have something to take away and treasure, even if one participant proposed that the Twilight Learnings could have lasted longer because of a growing potential to learn from each other.

Figure 5. Conversation notes, and candles in darkness. Photo: Åsa Ståhl

Another ending was when we shared a few minutes of silence and returned to reflect on our experiences of the time together in the THoW – in some ways an actual Kura Skymning. Gratitude was manifested from one participant to the next through our reflections, words offered like candles lit from one to the next, a communal feeling of having shared something important. Sitting together in silent darkness, dreaming, sharing takeaways on the challenges and joys of change-work and expressing gratitude led to making plans to sustain newly formed relationships. For example, one participant found that ending in silence was a really important step after all of the space for sharing and connecting with words. The silence was grounding and allowed us to explore on our own how we had connected with each other and the place. One participant said six months later, about the break-up in the THoW: ‘No one wanted to go home, didn’t want to light up reality again.’

Stepping out of the ThoW, however, involved not fuelling the fire in the stove anymore but rather letting that light and heat fade out as well. Walking through the door frame, down the steps and putting on clothes was thus one way of stepping out. Another way of stepping out of the THoW is to allow for staying in that twilight – one that intermingles temporalities, actors and spaces – by lighting up the fire of collaborative learnings in the writing of this article.

Meta-reflection on turning away from prescriptive writing and into community-based research and practice

This article has explored the co-presence and reflective experiences of community engagement in the THoW (section 3). Whereas no prior community existed, old business partners from Macken met up again, as well as alumni and university employees of Linnaeus University, and new relationships were established between Holding Surplus House and Smålands Trädgård. This diversity of participants’ identities brought a plurality of experiences and different situated knowledges. There was growth and change present in the THoW by consciously letting go of attempts to fully control situations: overcoming past frustration, developing hope, cathartically making closure and moving forward through sharing and understanding. Thereby, storytelling contributed to thick temporalities (Jönsson, Lindström & Ståhl 2021) and became a factor in our co-presence.

Learnings on change work

We acknowledge that research is performative, and that it makes worlds (Watts 2021). In both the references on different ways of knowing and making worlds that we build on (Section 2) and in the material that has been generated through the Twilight Learnings, we draw the following conclusion: to make change one needs to move between practical, political and personal work to build collective change (Leichenko & O’Brien 2020). In other words, harnessing the current momentum for change is a dance between individual work and entrepreneurial company work; there is work that needs to be done in the structures around us; and then there is the institutional work, political and legislative. In addition, and as suggested by Gibson-Graham (2008), conversations need to be practiced and people need to be pulled in, starting from the ones around us. In reference to the Twilight Learnings, collective change is built at the practical level through the daily work of social economy organisations addressing societal needs. Western cultural tradition has tended to attribute, to individuals, or individual associations or economic enterprises, the responsibility for solving social problems, instead of expecting that the task belongs to communities and governments (Houtbeckers 2018). Thus, it is important to understand the practice of individual third sector organisations not as an individual heroic activity but to keep in mind that transformative capacity lies in highlighting such practices to expand imaginaries and empower communities of practice to emerge that address common goals.

At the same time, it has been expressed by participants involved in this type of change work that capacities are needed to recognise which laws and regulations inhibit or facilitate the practical work and how to lobby the system at different levels to make a shift that is beneficial to change work. Nevertheless, a cultural transformation can be achieved only if social economy organisations develop the capacity to communicate and make visible the practical work and therefore expand the imaginaries of non-capitalistic ways of organising the economy and society.

More specifically, to make allies, one needs to develop or harness advocacy skills with which to approach structures. Structures can be challenged by engaging one’s core values and crafting a narrative that resonates with the perspectives of those involved in dialogue. People have different roles and identities within society that can be used to approach different supporting structures. When possible, it is crucial to turn to the structures with counter-narratives to pave the way for others, saying it with confidence and leveraging research. This includes lobbying the system – and recognising that the system is us.

Change through community-building is not a straight, smooth line, but rather a bumpy road. Change work is made of momentums, both successes and failures – being able to transform, handle losing and letting go when necessary are therefore key. This is shown in our own material and in the references.

One of the participants commented on scaling change-work when we met up again six months after the Twilight Learnings. The participant connected values to scaling. We translate what they said: ‘The values are so strong in many that they act based on the values and want to shape the world based on what one believes in, using one’s force and strength for the good’. Value frictions also seem to be important in taking action: ‘One works on changing that which one finds to be frictions in society based on what one can. This gives hope – this is where societal change happens’. And then the participant continued by connecting to the emerging community: ‘That these people exist – when one doesn’t see it, it is hard to believe that it exists, but this set of humans exist in many places. And this meeting – then it can happen in more places.’

The emerging hope is connected to knowing that there are others who work with a strong driving force towards change, to an emerging community and its temporality: being able to share and recognising that nothing stays forever. This recognition of temporality, of what can happen over time, plays a major role in community building.

On answering the explicit question, has anything moved from the Twilight Learnings session in the THoW, one participant answered: ‘not content-wise, but in terms of hope’. Similarly, Leah Ireland reflects that the agency developed and lessons learned in our sharing live on in the participants. With the help of O’Brien et al. (2023), we can call this way of understanding change ‘fractal scaling’. Rather than scaling by maintaining or building upon the group structure as it was, the participant-turned-author recognised how the stories shared offered a sense of empowerment and reinforcement of values that could then be brought with her into other contexts. When the participants speculate on the creation of a learning community in which values, experiences, struggles and strategies have been shared impacting the cultural roots of those involved, they are thus imagining what could be called both deep scaling and fractal scaling. The takeaway from the Twilight Learnings is then not a list of facts or skills, but an emerging scalable community of practice.

Learnings on community writing

This article is our attempt at inquiring into and showing what difference radical co-presence can make in temporary communities and how it can be illustrated in a journal article. Along this line, we also want to reflect on turning away from prescriptive writing technologies that define credible witness to experiments (Haraway 1997; Stengers 2018). We have aimed at making this article innovative in the way that it describes a collaborative study in which researchers and practitioners write together in a participatory and collective way. The article documents hidden and marginal stages of a research process, allowing longer timeframes for collaborative writing in line with the principles of slow science (Stengers 2018).

To sum up, we have:

1. invited co-writers;

2. invited guardians and authorities of the article; and

3. moved from individual voices to a somewhat collective voice.

Through exchanging emails and organising Zoom meetings, we elevated the article from a partnership between two academics into a co-authorship with a practitioner and workshop participant.

We also let go of systematic research control by opening up different ways of involving participants with the article. We developed guardians of the article, that is people who do not manually type in words but contribute to meta-reflecting in physical and online spaces adding richness to the reflections in the article format.

Being involved in the making of this article has been described by one participant as a fantastic alternative to come to the core (kärnfullhet in Swedish) of things; to access deep understanding, reflection, knowledge sharing, community engagement, as well as knowledge production and community building.

The process of making this article has allowed us to reflect over time and to slowly build an emerging community as we turn to each other as participants and co-authors to discuss, iterate and develop the structure of our writing. We have thus become an emergent community in a slow process of knowledge and world-making.

Final remarks

The confined presence in the THoW generated a stillness that allowed us to travel through experiences of friction as well as hope. The THoW not only provided a space for doing research differently due to the social material circumstances it enabled, but it also acted performatively in bringing things about. We also suggest, although this might seem like a long stretch, that the THoW is a voice of both similarities and differences. The THoW has allowed these experiences and words to be articulated, as emphasised by several of the participants. The THoW thus appears here as a subject that, in line with processual ontology and epistemologies that recognise that making and knowing worlds go together, can hold frictions and hope of differences and commonalities over time and place. Importantly, when subjectifying the THoW, we must listen to the many voices it hosts and lodges. Therefore, our method and our matter-of-concern are connected in the sense that they both try to challenge dominant paradigms – traditional science methods and economic growth – by opening up different ways of conducting research and organising the economy. However, although this is particular and unique, we claim that the THoW, together with the methodology used to guide participants, generated a fractal-like pattern that enacted situated knowledges and experiences that connect to global sustainability challenges. These learnings can be precious at different scales and the socio-material circumstances in which they were created can be of inspiration to scale this practice. This is how we think scaling can be understood in this context.

We claim that the Twilight Learnings that took place in the THoW itself and the writing process of this article led to an emerging community of actors – that already had common interests and experiences of change through entrepreneurial and academic efforts – and represented a continued reflective space. The hours in the THoW, hosted by Silvia Mugnaini and Åsa Ståhl, resulted in relationships that have proved to be meaningful and that have taken on a life beyond the initial meeting. Writing this article means that we are part of ‘making the world’, a world where the participants know of each other’s work and have articulated the hope that is generated by knowing that one is part of a movement. During this process, differences have also been centre-stage and have led to learnings; for example, Macken acted as an elder, a wise example with many joyous and troublesome nuances to learn from.

In particular, our material recognises that change work can be sustained by the hope generated through knowing that other change-making practitioners and practices exist. This is the important emerging community. And although it might seem contradictory when a participant said they had learnt from the Twilight Learnings that nothing needs to be permanent, it is simply a paradox to live with; that imagining change through brief entrepreneurial efforts involves recognising that it is a way of building up potentials or momentums of something that might look different but that was seeded in earlier attempts.

Our material shows that change work requires mobilising different capacities. Cultivating sustainability initiatives requires nurturing complex relationships. To secure allies, one can advocate one’s values, goals and interests, or take on an ambassadorship role, as one of the participants said. At the same time, those engaged in the social economy world must be able to let go, allowing new people with new skills to take the lead if necessary.

We have further understood that the relevance of this article lies in its utility for individuals aspiring to start a social enterprise, as it highlights the strengths and weaknesses of such businesses. Similarly, it is valuable for those already involved in the field, offering opportunities to connect with others and learn new strategies to enhance their organisations. Additionally, the article provides guidance for politicians that can offer financial and structural support to those organisations as they contribute to addressing societal issues for which the government is also responsible. Finally, the article gives insights into networks of social economy organisations and representative associations on how to better drive their advocacy and lobbying efforts to pave the way for social economy’s change work.

Finally, the collective research and writing processes also enabled a reflection regarding the agency of different actors involved and the struggles and dilemmas that collaboration entails; the feeling of organising collaborative encounters, participants being given space to imagine the future and for whom, in giving learnings back, have the feeling of playing the expert while learning as well. Not all tensions may be resolved but they can drive further research and reflection. For example, developing matters-of-care (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017) could be a potential direction in upcoming community engagement writing practices and efforts.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Mariana Gómez Johannesson as guardian of the article for sharing ideas regarding the article in an oral form. We further acknowledge all the workshop’s participants for their contribution in co-producing knowledge.

Reference list

Augenstein, K, Bachmann, B, Egermann, M, Hermelingmeier, V, Hilger, A, Jaeger-Erben, M, Kessler, A, Lam, DPM, Palzkill, A, Suski, P & von Wirth, T 2020, ‘From niche to mainstream: The dilemmas of scaling up sustainable alternatives’, GAIA-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 143–7. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.29.3.3

DiSalvo, C 2022, Design as democratic inquiry: Putting experimental civics into practice, The MIT Press, Minneapolis. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/13372.001.0001

Federighi, P (ed.) 2018, Educazione in età adulta: Ricerche, politiche, luoghi e professioni, Firenze University Press. https://doi.org/10.36253/978-88-6453-752-8

Gibson, K, Bird Rose, D & Fincher, R (eds) 2015, Manifesto for living in the Anthropocene, Punctum Books, New York. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1r787bz

Gibson-Graham, JK 2008, ‘Diverse economies: Performative practices for other worlds’, Progress in Human Geography, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 613–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132508090821

Haraway, D 1988, ‘Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective’, Feminist Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 575–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Haraway, DJ 1997, Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium. FemaleMan©_Meets_OncoMouseª: Feminism and technoscience, Routledge, New York and London.

Hölscher, K, Wittmayer, JM & Loorbach, D 2018, ‘Transition versus transformation: What’s the difference?’, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, vol. 27, pp. 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.10.007

Houtbeckers, E., 2018. ‘Framing social enterprise as post-growth organising in the diverse economy’, Management Revue, Vol. 29, pp.257-280. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2018-3-257

Ives, CD, Schäpke, N, Woiwode, C & Wamsler, C 2023, ‘IMAGINE sustainability: Integrated inner-outer transformation in research, education and practice’, Sustainability Science, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 2777–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-023-01368-3

Jönsson, L, Lindström, K & Ståhl, Å 2021, ‘The thickening of futures’, Futures, vol. 134, p. 102850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2021.102850

Lam, DPM, Martín-López, B, Wiek, A, Bennett, EM, Frantzeskaki, N, Horcea-Milcu, AI & Lang, DJ 2020, ‘Scaling the impact of sustainability initiatives: A typology of amplification processes’, Urban Transformations, vol. 2, pp. 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42854-020-00007-9

Law, J 2004, After method: Mess in social science research, Routledge, London.

Leichenko, R & O’Brien, K 2020, ‘Teaching climate change in the Anthropocene: An integrative approach’, Anthropocene, vol. 30, p. 100241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2020.100241

Lenz Taguchi, H 2018, ‘The fabrication of a new materialisms researcher subjectivity’, in C Åsberg & R Braidotti (eds), A Feminist Companion to the Posthumanities, Springer, Switzerland, pp. 211–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62140-1_18

Lindström, K & Ståhl, Å 2019, ‘Caring design experiments in the aftermath’, in T Mattelmäki, R Mazé and S Miettinen (eds), Nordes 2019: Who Cares?, 3-6 June, Aalto University, Espoo, Finland. https://doi.org/10.21606/nordes.2019.022

Moore, ML, Riddell, D & Vocisano, D 2015, ‘Scaling out, scaling up, scaling deep: Strategies of non-profits in advancing systemic social innovation’, The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, no. 58, pp. 67–84. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2015.ju.00009

O’Brien, K, Carmona, R, Gram-Hanssen, I, Hochachka, G, Sygna, L & Rosenberg, M 2023, ‘Fractal approaches to scaling transformations to sustainability’, Ambio, vol. 52, no. 9, pp. 1448–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-023-01873-w

Puig de la Bellacasa, M 2017, Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2753906700002096

Raven, R, Reynolds, D, Lane, R, Lindsay, J, Kronsell, A & Arunachalam, D 2021, ‘Households in sustainability transitions: A systematic review and new research avenues’, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, vol. 40, pp. 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.06.005

Semeraro, R 2014, ‘L’analisi qualitativa dei dati di ricerca in educazione’, Italian Journal of Educational Research, no. 7, pp. 97–106. https://ojs.pensamultimedia.it/index.php/sird/article/view/267

Star, SL & Griesemer, JR 1989, ‘Institutional ecology, “translations” and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology’, Social Studies of Science, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 387–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

Stengers, I 2018, Another science is possible: A manifesto for slow science, John Wiley & Sons, England.

Tham, M, Ståhl, Å & Hyltén-Cavallius, S 2019, Oikology – Home ecologics: A book about building and home making for permaculture and for making our home together on Earth, Linnaeus University Press, Växjö.

Tsing, AL 2015, The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins, Princeton University Press, Princeton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400873548

United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy (UNTFSSE) 2022, Social and Solidarity Economy and the Sustainable Development Goals, viewed 11 October 2024, https://unsse.org/sse-and-the-sdgs/

Wamsler, C, Hertog, IM & Di Paola, L 2021, ‘Education for sustainability: Sourcing inner qualities and capacities for transformation’, in E Ivanova & I Rimanoczy (eds), Revolutionizing Sustainability Education, Routledge, pp. 49–62. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003229735-6

Watts, L 2021, ‘Poetry and writing’, in K Jungnickel (ed.), Transmissions: Critical tactics for making and communicating research, The MIT Press, US.