Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 18, No. 1

January 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE (PEER REVIEWED)

Reflections on Multimodality: Making the Most of Kairotic Moments

M. Rebecca Genoe1,*, Darla Fortune2, Colleen Whyte3

1 Faculty of Kinesiology and Health Studies, University of Regina

2 Department of Applied Human Sciences, Concordia University

3 Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies, Brock University

Corresponding author: M. Rebecca Genoe, Rebecca.Genoe@uregina.ca

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v18i1.9204

Article History: Received 27/06/2024; Revised 03/12/2024; Accepted 11/12/2024; Published 01/2025

Abstract

It is generally accepted in extant literature that friends drift away after a person receives a diagnosis of dementia. In turn, we set out to explore friendships that continued to flourish following a diagnosis by interviewing people living with dementia, their friends, and family members. Along the way, we shaped and adopted a multimodal approach, incorporating artistically rendered, fictionalised vignettes based on our participants’ stories, thus incorporating visual and auditory components that encourage people living with dementia and their friends to reflect on how best to continue to nurture their relationships. In this article, we describe our process of adopting multimodality through an intertwined set of five kairotic moments, whereby we pushed ourselves out of our comfort zones to move beyond the format of the conventional peer-reviewed journal article, recognising the need to write differently to reach a broader audience. In another moment, we moved past an academic emphasis on writing to adopt multimodality. Subsequently, we connected with artists and knowledge mobilisation specialists to bring our collective vision to life. Finally, we aimed to make our study findings more accessible by sharing them through our website and engaging with various types of media. We conclude by offering a methodology for multimodality that includes relationality, axiology, passivity and action and temporality in embracing opportunities to write differently.

Keywords

Dementia; Friendship; Kairotic Moments; Methodology; Multimodality

Introduction

This paper reflects on and proposes a methodology for multimodal action with conceptual, practical and epistemological implications for the research process. We detail our research journey through a specific study, emphasising pivotal moments that inspired us to adopt multiple modes of representing data and actively engage with our findings. In turn, these five interconnected and overlapping ‘kairotic’ moments helped to shine a light on our researcher conversations and deliberations rooted in relationality, axiology, temporality and the active engagement with knowledge. These deliberations prompted the research team to critically examine the purpose of academic writing and question who benefits from its traditional structures and venues for dissemination. Moving beyond traditional approaches enabled us to confront uncertainties regarding knowledge mobilisation, researcher control and academic expression. Our adoption of multimodality, incorporating artistically rendered, fictionalised vignettes, conversation guides and media engagement, were essential in effectively disseminating our findings to those most likely to benefit from them. As we experienced these ‘kairotic’ moments, we learned a great deal from the challenges and opportunities of embracing multimodality in our research. We now hope to apply these insights and iterative methodological processes to our traditional knowledge mobilisation efforts. We offer our resultant methodological blueprint to encourage others to adopt multimodality in their research process.

Kairos: The right occasion

Researchers are often reminded of the importance of translating research findings for practical use (for example, Glover 2015). These activities – broadly understood here as knowledge mobilisation, which includes the conventional peer-reviewed research article – are generally envisioned as occurring at the end of a linear research process which places primary importance on the production and dissemination of scientific knowledge. The sharing of alternative types and modes of knowledge – communicating stories as stories, for example – comes later. Yet the production of knowledge occurs in an iterative manner, influenced by the researchers’ epistemology and axiology, the research question(s) and methodological approach. Further, decisions made at each stage influence the types of knowledge that are produced and who gets to be involved in its production. The seemingly neutral linear conception of the research process tends to obscure what is in fact the active, serendipitous nature of research and its dissemination. As we moved through the phases of our qualitative approach to knowledge production, we experienced several moments that we came to call ‘kairotic’, as they effectively interrupted our thinking and anticipated activities. These differently-felt moments enabled us to embrace multimodality in sharing the knowledge produced in different ways, including both traditional academic writing and presentations, as well as fictionalised vignettes and conversation guides.

The word ‘kairos’ originated in Ancient Greece and refers to ‘the right moment or occasion’ (Baert 2020, para. 1). According to Fletcher (2022), there were two ways of conceptualising time in Ancient Greece: chronos, or quantifiable time and kairos, which is relational in nature. Chronos refers to duration and amount of time, whereas kairos refers to the character, quality of, the position or circumstance, significance, and opportunity of time (Fletcher 2022). For example, a research study unfolds in chronological time, yet there are many opportunities to make decisions that influence the production of knowledge. Thus, there are many ‘right moments’ or occasions that researchers may experience which influence not only what knowledge is produced, but also how it is produced and used. We experienced several of these ‘right’ moments or opportunities in our research process.

Various definitions of kairos exist. Some define it as ‘a rhetorical appeal that uses situational context and precise timing to deliver a message, so it is perceived with the greatest impact and urgency’ (Calonia 2024, para. 4). It also refers to a time for accomplishment of crucial action (Merriam-Webster n.d.). In academia, kairotic spaces are informal sites where knowledge is produced and power is exchanged (Price n.d.). Price provides the example of an academic conference as a kairotic space, or many kairotic spaces where conference attendees exchange knowledge and power in informal moments, such as during the question and answer period following a presentation, or during a conversation between delegates at the elevator. Price provides five characteristics of the kairotic space including: (1) real time unfolding of events; (2) impromptu communication; (3) presence of participants, either in person or virtually; (4) a strong social element; and (5) having high stakes, where there is potential for meaningful impact.

Throughout our research project, we experienced kairotic moments that pushed us to think about and act on our research non-traditionally and to share our findings with those for whom they matter the most. These opportunities provided room for us to produce and share knowledge in new ways, to share power and, we hope, deliver an impactful message to our intended audience – people who are living with dementia, their family members and friends, along with service providers who may be supporting them.

In the next section, we provide the context of our original study. This is followed by our kairotic moments. Then, we describe our multimodal methodology and practical writing strategies. We conclude with thoughts on how we will incorporate these insights into our research moving forward.

Context

In the study that inspired our move towards multimodality, we set out to explore how friendships can be maintained after a diagnosis of dementia. Rooted in constructivism, phenomenology and a strengths-based approach, we interviewed people living with dementia, their friends and family members to find out what made their friendships work. Forty participants, including individuals with dementia, friends and family shared their insights, tips, joys and challenges of friendship. We analysed our data using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke 2006) (for a more detailed description of our findings, please see Fortune, Whyte & Genoe 2021; Genoe, Whyte & Fortune 2022). Findings from our research illuminated how relationships were maintained, re-constructed and negotiated after a diagnosis of dementia and highlighted meaningful ways to support sustained friendships. For over a year, each of us sat in the kitchens and living rooms of people who had known each other for years and even decades. Our interview transcripts were filled with rich and profound stories that spoke of the bonds of friends who are like family. We heard stories of kindness, compassion and reciprocity amongst friends who looked out for each other and connected over shared interests. We learned how spending time together is important: ‘I just love being in her presence still. It doesn’t really matter. Sitting and having a cup of tea with her ...’ (Genoe, Whyte & Fortune 2022, p. 436). Friends appreciated each other regardless of their current abilities and level of support that they may have required: ‘... there’s still a sense of humour ... Just the fact that he’s right there and enjoying his beer and always mentions, “oh yeah, I remember all the good times we used to have”’ (Genoe, Whyte & Fortune 2022, p. 438). Another friend stressed the importance of patience and kindness: ‘I would say that I try not to be different than I’ve always been except I try to, at the same time, be far more patient. I’m quite willing to listen to the same story time and time again as if it’s a new story to me’ (Genoe, Whyte & Fortune 2022, p. 437). Our findings emphasised the meaning and importance of sustaining friendship after a diagnosis of dementia.

When it came time to share the findings from our study, we presented at academic conferences and published academic manuscripts, with the traditional structure of background, literature review, methods, findings and implications for future research (Fortune, Whyte & Genoe 2021; Genoe, Whyte & Fortune 2022). Our knowledge mobilisation (KM) plan included creating text-based documents (for example, plain language summaries) for dissemination to agencies such as the Alzheimer Society of Canada and disseminating our findings among practitioners at professional conferences. We also planned to produce written tools to showcase evidence-informed strategies adopted by individuals and friends to sustain their relationships. We committed to publishing our academic papers in journals that provided open access options so that these papers were easily accessible for all readers. We focused first on the traditional conference presentations and peer-reviewed articles, leaving the other types of KM to later in our research process.

The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) defined KM as ‘the reciprocal and complementary flow and uptake of research knowledge between researchers, knowledge brokers and knowledge users—both within and beyond academia—in such a way that may benefit users and create positive impacts within Canada and/or internationally, and, ultimately, has the potential to enhance the profile, reach and impact of social sciences and humanities research’ (SSHRC 2024, para. 33). When it came to the uptake of knowledge within academia, our intention was to engage academics to learn from the rich stories presented in our published articles in order to advance a more balanced representation of dementia that goes beyond tragedy discourse regarding life with dementia. Findings from our work resonated with fellow academics who study experiences of dementia from a social well-being lens. Manuscript reviewers noted that it was ‘nice to read something that takes us entirely outside of the health and care domain with a focus instead on day-to-day living with dementia’ and ‘I applaud the authors for recognising the dearth of, and value of, research focusing on the topic of friendship for people living with dementia and working to add to this body of research.’ At conferences, we had many great conversations with peers who appreciated hearing about the gifts of friendship with someone who lives with dementia, the meaningful role leisure plays in maintaining joy, fun and engagement in life, and tips shared by friends who simply want to pass on strategies that work for them with the goal of destigmatising dementia. In fact, the invitation to submit an abstract to this special issue arose at one of these academic conferences.

While pleased that our research findings were out in the academic world, we were left with the feeling that our study was unfinished. There was a visual aspect to our data that was not captured in text-based journal articles, plain language summaries or other written tools. As a research team, we felt an obligation to share our participants’ stories with people who could learn from them (for example, individuals living with dementia, their families, the public); stories that did not translate well into the formula of short snippet direct quotations around a researcher-generated theme. Our participants’ stories were dissected into codes which, when combined with other ‘like’ snippets, became the holy grail of qualitative research – the theme. The story from start to finish no longer held the same meaning. Furthermore, the stories we heard did not lend themselves to creating ‘tools’ outlining tips and strategies – these stories needed to be shared in more evocative ways. Challenging the way we understand dementia and social well-being was a much bigger issue than could be addressed in academic journals alone. These publications, with their few citations, did not necessarily tip the scales in favour of a more balanced representation of lived experience of dementia and friendships. This is particularly the case when we consider that the very individuals who could benefit most from research findings typically do not engage with such traditional forms of KM (for example, academic journal articles) (Boydell & Croguennec 2022).

We started by asking how our stories could be represented in a manner more reflective of their rich and storied nature. We regretted not video recording our kitchen conversations. In its place, could we explore arts-based representations of our texts that incorporate moving visual images and sound? Could this exploration lend itself to a more effective dissemination of our stories and their lessons among people for whom this issue resonates? Our intention in considering alternative types of KM was not only to share our stories, but also to have users consider the stories in relation to their own experiences. Appreciating how the use of visual imagery and animation can be effective KM strategies due to their evocative and engaging nature and ability to instill an emotional connection with the material (Boydell & Croguennec 2022), we wondered how an emotional connection with our research findings might prompt people to engage differently in their friendships. For example, by sharing the poignant ways friends were negotiating their relationships, could we invite knowledge users to commit to action in their own friendships?

Writing differently: Embracing multimodality through five kairotic moments

While immersed in the data we generated with our research participants, we grappled with the challenge of presenting it in ways that were meaningful to those who would benefit the most. The data were deeply moving, often more so than other studies we had conducted in our respective research programmes. For example, it was touching to hear a participant speak so affectionately about her friend with dementia and share that while she found some of the changes upsetting to see, she still loved being in her presence. As participants told us stories of their years-long friendships and what it meant to sustain them after dementia, we recognised that sharing these stories in traditional academic journal articles was simply not enough.

Based on these rich stories, we knew that our findings mattered for people living with dementia, their loved ones, the general public, health care providers, policy makers and researchers. In particular, they were vital for counteracting the tragedy discourse of dementia (Genoe, Whyte & Fortune 2022) as they emphasise both gains and losses after a diagnosis of dementia rather than assuming that life is over after diagnosis (see Genoe & Dupuis 2012; Genoe & Fortune 2024). These findings were important for shifting the way people perceived themselves and others. These stories provided the situational context for the kairotic moments, or opportunities, that subsequently propelled us towards embracing multimodality. We needed to reach people who were navigating the complexities of living with dementia and needed to hear these stories.

In Figure 1, we provide a visual depiction of our kairotic moments, with each grouping of flowers representing one of our five kairotic moments. The green hills represent the situational context: our participants’ stories that set the stage for these five moments. The sky above, which is vital for growing plants by providing light, water and oxygen, represents the exchange of knowledge and power, which combined to create the ‘right moment’ to move forward in our journey. With the situational context serving as rich, fertile soil for growing strong roots, the flowers representing our kairotic moments were nurtured through social engagement whereby we shared knowledge and power to best present the findings of our study.

It is relevant to note that while we present these as series of moments, they did not occur in isolation. Rather, these moments of producing knowledge and exchanging power as we learned to ‘write differently’ overlapped and informed one another.

Recognising the necessity of writing differently

In June of 2018, Rebecca’s university hosted the annual Congress of the Social Sciences and Humanities, a national conference that brings together academic associations from across Canada for knowledge translation. Our own association, the Canadian Association for Leisure Studies, was attending the event for the first time in its history. The conference was the catalyst for our first kairotic moment (represented by the patch of white flowers on the left-hand side of Figure 1). All three of us were attending the conference, and we booked extra time at the beginning to connect with each other about the data and to identify our next steps. As a geographically dispersed research team, our meetings were largely virtual, and communication occurred through email. This was a rare instance when all three of us were together in one place.

We met in a hotel lobby over breakfast to discuss the data, share our initial thoughts on themes and subthemes, and consider how to divide the data up for the requisite peer-reviewed publications (Darla would focus on leisure, Rebecca would focus on strategies and Colleen would write about the gifts of friendship). Once we identified a writing strategy, we turned to the elephant in the room – non-traditional KM – the area where we most lacked relevant skills. How could we move beyond our comfort zones to ensure the strategies and approaches for maintaining friendship would not appear only in academic journals, waiting for another researcher or instructor to search for the right key words and land on these articles? Darla suggested writing a play. We considered this briefly, but decided this approach was too resource intensive and we lacked the knowledge and skill to write a script. We did not reach a decision that day, but this kairotic opportunity prompted us to leave the meeting with deep awareness that the knowledge we were generating needed to be shared in a creative and meaningful way that was accessible to people living with dementia and their friends. We needed to shift the power to people living with dementia and their friends to have the knowledge they needed to make decisions about their own relationships. We all agreed: traditional academic outputs along with plain language summaries and tools were not ideal for reaching the audience we wanted to reach in a meaningful way. In keeping with Price’s (n.d.) characteristics of a kairotic space, this meeting over coffee and pastries (social element) was informal in nature with casual, impromptu conversation as we tossed around ideas and grappled with the challenge ahead of us. We were physically present in the moment (presence of participants) as we contemplated the implications of our study and how to share them with others (high stakes, as moving beyond the conventional journal article to have meaningful impact was a risk we were willing to take).

Moving past the boundaries of the traditional academic article

Recognising the need to write differently provided us with the right opportunity to consider our research findings beyond the traditional academic journal article. However, doing so required resources. Thus, the next key kairotic moment in our move towards multimodality came during 2020 as we sheltered in place to wait out the pandemic restrictions. Data collection and analysis were complete, and two of our manuscripts were in various phases of writing, editing and being submitted to journals. We had prioritised academic writing to satisfy our respective annual review processes, whereby our colleagues and deans expect to see ‘productivity’ in the form of peer-reviewed articles. The period of our grant was almost up, but we still had funds to put towards alternative forms of communication. As principal investigator, Colleen worked her magic with her research office to extend the funding and we started more seriously brainstorming ideas for writing differently. This opportunity allowed us to direct resources to multimodality. We now had the flexibility to move forward with sharing these rich stories in new ways.

Turning away from the traditional approach to writing, this was the opportune time to draw on creative analytic practice, and we wrote fictionalised vignettes based on our participants’ stories (see Box 1 for an example). We each wrote a vignette relating to our respective peer-reviewed manuscript, with Darla focusing on leisure, Rebecca focusing on strategies and Colleen focusing on the gifts of friendship. Rebecca notes:

To write my vignette, I spent time reflecting on the stories of friendship the participants shared with me. I returned to my initial codes and their associated quotes and spent time considering the data. Writing for a non-academic audience requires a different headspace than a traditional article. That headspace always feels more relaxed and natural to me, but it is not always easy to transition in and out of it. I considered what strategies I wanted to prioritise and how to share those stories in an engaging manner. In doing so, I created a composite of participants and fictionalised two friends, both women, sharing their stories. My vignette consists of three stories or scenes, and includes a narrator who tells the viewer about her friend, Claudia, who was diagnosed with dementia. Each story/scene focuses on one major theme from the data analysis that highlights strategies that friends used (see Genoe, Whyte & Fortune 2022). The first, prioritising friendship, explores the history of the friendship and highlights the ways that the two friends stay in touch and support each other. In the second section, the narrator identifies how she has changed her thinking about the friendship. The third scene highlights practical strategies, and the narrator tells the viewer about the importance of direct communication and spending time together. While writing, I envisioned what images I wanted to use to portray the story. I considered these stories as a window into the lives of our fictionalised research participants, and the artists incorporated the symbol of the window into the vignette.

In tandem with writing our vignettes we worked closely with artists who made up for the important skills we lacked in making our stories come to life. Decisions were made on colour schemes, images to be used and how the videos would be narrated. We met several times with the artists and reviewed many versions of the vignettes before signing off on the final versions. A particular challenge was colouring: we wanted bright, vibrant colours while the artists preferred more muted, subtle colours (see Figure 2 for an example of the final artwork). This process involved relying on the artists’ expertise, while sharing our knowledge generated through the study. Through this kairotic moment, power shifted back and forth between the artists and us during a reciprocal process. We had a particular vision, but relied on the artists’ skills to execute that vision, and to inform us about the feasibility of the vision.

Once we agreed upon all three vignettes, we were ready to find ways to share these stories with a broader audience.

Figure 2. A group of friends shares a meal: Still image from ‘Leisure and Friendship’

Recognition of the need to write differently for our intended audience of people living with dementia and their friends signalled the start of a longer kairotic moment in our process. This moment was characterised by creativity, collaboration and learning. The moment, represented by the grouping of orange flowers in Figure 1, was vital for embracing multimodality within our process in real time over several months, where we came together virtually as a research team and with the artists. Our Zoom meetings allowed us to connect with each other and share ideas in a safe, non-judgemental space.

Conversations with friends

We recognised that it was not enough simply to show our vignettes to those who might benefit. We wanted viewers to engage with the material and consider how the vignettes might relate to their own experiences with friendship and dementia. This realisation led to an additional kairotic moment. To help us through it, we reached out to a KM expert whose work we already admired. The KM expert, Lisa, was well versed in non-traditional KM for people living with dementia and their family partners in care. Furthermore, Lisa had connections to people with lived experience of dementia and could include them in the next step of our multimodal journey. Lisa connected with Brenda, who lives with memory loss. Lisa and Brenda have a history of working together on research projects, and, importantly, have developed a friendship themselves.

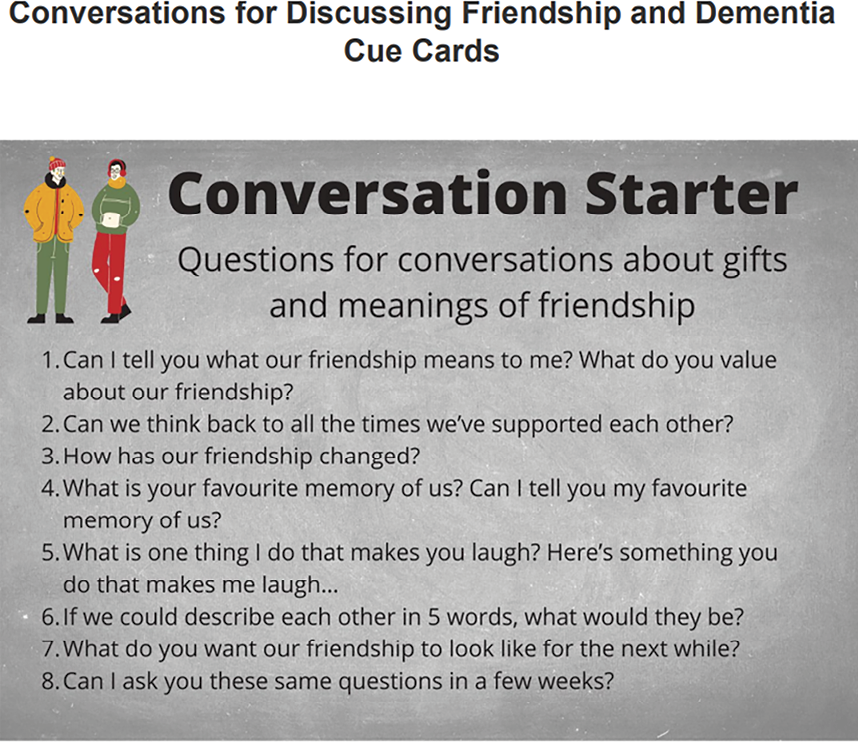

Lisa and Brenda worked together, viewing the vignettes, and chatting about them, and then writing a series of conservation guides to accompany the vignettes. The guides included suggestions for how to have discussions about friendship and dementia, including a list of dos and don’ts, tips for starting conversations, tips for maintaining friendships, and questions that people living with dementia and their friends can ask each other to determine how best to sustain the friendship (for example, how can I support you to make use of your skills and strengths?; where do you feel safe and able to be yourself?; how do we check in on our friendship? See Figure 3).

This kairotic moment, represented by the blue forget-me-not flowers in Figure 1, gave us space to exchange knowledge and power with Brenda and Lisa (blue forget-me-nots are used to raise awareness of dementia). Once again, we were no longer the experts, and needed Brenda’s and Lisa’s wisdom and experience to turn our research findings into tangible, bite-sized information that supported people living with dementia to have challenging and potentially uncomfortable conversations with their friends.

Figure 3. Example of our conversation starters. These questions are designed to inspire reflection and discussion between people living with dementia and their friends to explore what their friendship means to them.

Taking the research online

While we worked with Brenda and Lisa, we also contracted a web developer to build a website suitable for hosting the vignettes, conversation guides and other information about the study (see https://dementiaandfriendship.ca/) for access to the vignettes, conversation guides and other information related to the study). Now that we had content to share with our intended audience, it was the right time to determine how to make the information accessible. Again, we needed to find appropriate partners to assist in the areas where we lacked skills, and website development is certainly not our forte. Our goal with this phase of our KM process was to provide access to the information that people living with dementia and their friends could find and use with ease. As such, we wanted the website to be user friendly and appealing. We shared a lay summary of the study on the website along with the vignettes and conversation guides. We also included links to our open access peer-reviewed papers, and other media engagements. The website allowed us to make the most of multimodality by providing virtual space to present the data in several ways. It enabled people living with dementia and their friends the opportunity to engage with the data at their own pace, picking and choosing from a variety of options – watching, reading, and listening to the knowledge generated through the study.

This moment, represented by the second group of white flowers in Figure 1, also unfolded over several months as we engaged together as a research team to identify our needs and wants for the website, and as we engaged with the web developer to work through how best to present the information in an accessible manner.

Engaging with media

Completion of the discussion guides provided the catalyst for our next kairotic moment. We needed to take advantage of the opportune time to get our vignettes and discussion guides out into the world. Engaging with the media was vital for sharing our findings more broadly. We did so in various ways. First, Colleen took the lead on writing an article for The Conversation Canada, an organisation that helps academics to publish their research in a way that is accessible for non-academic audiences (Whyte, Fortune & Genoe 2022). Since publication, the article has been read more than 15 000 times, a marked increase from our peer-reviewed articles, which have accumulated approximately 1700 views and seven citations. We learned quickly from our Conversation article that complementing a traditional article with a more accessible one enabled us to connect with a much broader audience. While publication of articles in the Conversation is encouraged by our universities as an important means of KM, it is not necessarily rewarded in the annual review process and would not be considered as ‘worthy’ as traditional, peer-reviewed articles.

The article was subsequently picked up by other media outlets and led to an interview with CBC Saskatchewan with Rebecca and Brenda (The Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC) is the national public broadcaster in Canada. The interview took place during the morning show in Rebecca’s province of Saskatchewan). As well, Colleen worked with Brenda and Lisa to deliver a podcast on friendship and dementia, which was released around the time of International Day of Friendship, which is designated by the UN to acknowledge the importance of friendship for building community and providing safety (United Nations 2024). Details of all of these media engagements were posted on the website so that those looking for more information could easily find it. This moment, represented by the sunflower in Figure 1, required our virtual presence as we worked together to write the Conversation article and share our stories orally through media and social media.

These intertwined kairotic moments created opportunities for us as a research team to incorporate multimodality into our traditional qualitative research study. These moments were characterised by engagement of the research team alongside experts who supported us where we lacked skills in largely virtual spaces. Each moment helped us to move forward in our journey towards multimodality.

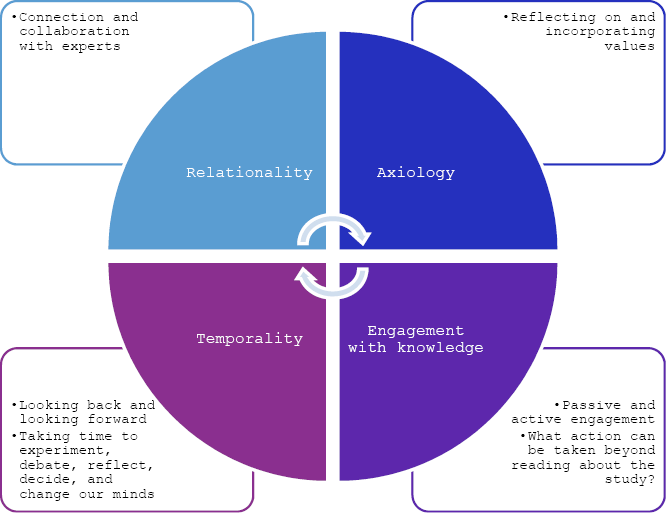

A methodology for multimodal action

In this section, we elaborate on the lessons learned along the way, proposing a methodology for multimodal action. Our methodology consists of four components: relationality, axiology, engagement with knowledge and temporality (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. A methodology for multimodality

Relationality: The importance of relationality to complement our skill set

Over the course of our work, we came to understand the importance of relationships in the process of moving beyond traditional KM towards multimodality. Kairotic time emphasises the importance of relationality, and likewise, Price (n.d.) stresses the social nature of kairotic spaces. Thus, connecting and collaborating with each other and experts in areas where we lacked skills was necessary for moving through our kairotic moments. For example, we knew we had the ability to write the vignettes, but not to bring them to life for the intended audience through imagery and sound. As such, we focused on our writing skills and then handed the stories over to artists who could create compelling visual images. Knowing we were well versed in qualitative research, but not as strong in creating reflective outputs, we drew on the expertise of our knowledge mobilisation expert and her friend with lived experience of dementia. These pre-existing relationships were vital in providing a safe space to share our work and to make it useful for people who are living with dementia and their friends.

We also learned how to work together as a research team. While the three of us had pre-existing friendships as graduate students, this was the first project we had undertaken together. Drawing on the strength of our pre-existing relationships and shared history of the challenges and tribulations of pursuing a doctorate enabled us to have difficult conversations and disagreements about the research process and data, and to work through our kairotic moments together as a team. Frequent video-conference meetings provided us with the kairotic space to develop our knowledge and consider the exchange of power (Price n.d.). These meetings helped us to prepare for collaboration with the KM experts and artists who brought our vision to life, which also served as vital kairotic spaces as we developed our KM tools. We were able to work out our own differences to reach consensus with each other before connecting with collaborators. Creating a safe space to explore differences was important for moving forward with each step of this process. Thus, our proposed multimodal methodology emphasises relationality and the importance of nurturing relationships among research team members and experts who support their work.

Axiology: Re-affirming our values

Over the course of the project, we reflected on the importance of our own values and how they guided the decisions made about the work we were doing. Our experiences as leisure practitioners working with older adults combined with our academic training in the field of leisure studies led to a set of shared values that helped to inform the study and subsequent KM products. First and foremost, our preference for strengths-based practice influenced our initial research question and directed us towards focusing on positive experiences of friendship after diagnosis rather than focusing on the tragedy discourse (Mitchell, Dupuis & Kontos 2013) most often associated with dementia. Beyond valuing strengths, we also hold inclusivity and adaptability in high regard. Thus, we emphasised the need to ensure that the tools created were user-friendly and relevant to people living with dementia and their friends. Reflecting these values, our tools are designed to be adaptable to individual circumstances. They are meant to serve as a guide rather than a list of step-by-step instructions. Again, drawing on the expertise of others played an important role in ensuring relevance. Lisa and Brenda had been friends for 20 years, and still learned new things about each other as they worked through the vignettes to create the discussion guides.

Reflecting on and incorporating values is vital for ‘writing differently’. Keeping our values at the forefront helped us to make decisions about how to present the data in a meaningful way. As such, axiology plays a key role in our proposed methodology, and we encourage researchers to reflect on and integrate their values throughout their own multimodal processes.

Encouraging both active and passive engagement with knowledge

As we experienced these kairotic moments, we came to view peer-reviewed publications in a different light. In the past, we ascribed to the peer-reviewed article as the gold standard and had learned to carefully follow a formulaic approach to writing and publishing. For example, each fall semester, Rebecca outlines the components of a manuscript for students in her graduate level research methods course. These components tend to follow a particular formula: the introduction identifies the research problem; the literature review identifies the gap in research and justifies the study; the methods section explains and justifies the approach; the findings focus on snippets of conversations organised into themes and subthemes; and finally the discussion highlights the contribution of the study to the extant literature. Our peer-reviewed manuscripts resulting from our friendship research follow a similar approach.

However, once we began to incorporate multimodality into our work, we recognised the limitations of the traditional approach. Upon reflection of the process, we came to see academic writing as a way to justify the need for our study and the decisions we made in order to answer the research questions. In contrast, embracing multimodality allowed us to create ‘active’ outputs, such as watching a vignette and answering reflective questions, downloading a conversation guide, and talking with a friend. While we continue to value the traditional academic article as an important means of sharing research findings, moving forward, our methodology for multimodality calls for researchers to challenge themselves and to consider what other actions can be taken to facilitate engagement with research beyond reading a published manuscript, particularly among non-academic audiences who engage with research in different ways.

Temporality: Planning for ongoing use

Multimodality gave us pause to consider temporality within our research outputs. Our study unfolded in chronological time (chronos), while kairotic time presented us with opportunities to do things differently. Additionally, our academic publications are a text-based report of the past (chronological time): what we DID; what we FOUND; what our participants SAID. Moving beyond the static, rear-view journal article to incorporate images, motion and audio forced us to recognise that these forms of knowledge mobilisation are about the present and future: why DOES this matter to you? What CAN you take away? How CAN you change your engagement? These questions go beyond a research-centred focus to include a variety of users. For us, multimodality was a way to look to the future with a sense of hope, and to support people living with dementia and their loved ones to do the same, particularly when that future might be very different from what one had imagined or hoped for. It was a way to facilitate kairotic moments beyond our research team as our tools provide people living with dementia and their friends and families with opportunities to discuss their relationships.

Through this project, we learned a great deal about ‘taking our time’, sitting with the data, allowing the stories to percolate, taking care with identifying next steps rather than pushing ahead quickly. We acknowledge that we were afforded a particular privilege in doing so in that Colleen’s university was willing to support the transfer of funds when the formal grant period ended, rather than sending them back to the funding organisation. This extra time gave us room to experiment, debate, sit with our decisions and change our minds. Taking time with our research allowed us room to engage in deep thinking that led to intentional decision making over time. As a result, our methodological approach to multimodality includes looking back and looking forward, but also slowing down and taking time.

Practical strategies for writing differently

The lessons we learned throughout this process highlight the need for two practical strategies related to writing differently. The first strategy is writing for relevance. Writing for relevance involves more than identifying the knowledge gaps or unanswered questions our study attempts to address; it involves deep reflection about the broader implications of our study and its real-world impact. A study’s potential impact increases when researchers focus on the needs of knowledge users rather than solely on the advancement of scholarly knowledge (Rutter & Fisher 2013). As Glover (2015) argued, for research to be relevant and have an impact, findings must be translated for productive use, which happens when research ‘concerns itself with helping individuals, communities, and groups make sense of their position in the world and the nature of the challenges that confront them’ (Glover 2015, p. 3). In regard to this project, we would consider our research to be relevant if it is useful for friends to start a conversation about how to navigate a dementia diagnosis or even to prompt a hypothetical conversation between friends prior to a dementia diagnosis. It would also be relevant if people were impacted by the deeply moving stories of friendship we shared and had the value of their own friendships reaffirmed.

The second strategy is building a well thought out KM plan from the onset (and still be open to change). We now realise that to do this, we need to identify and connect with intended knowledge users up front rather than later in the study. Indeed, as other researchers have argued, building strong networks with community organisations, policymakers and other stakeholders can help amplify both the dissemination and use of research findings (cf. Grimshaw et al. 2012; Gurukkal 2022). When conceptualising a study, it would be helpful to ask intended knowledge users not only how they think they may use the findings, but also how they would like to receive the findings. This strategy also highlights the value of involving knowledge users as partners on the research team from the beginning to enhance relevance and applicability. Many KM strategies highlight the need for active engagement and relationships forged between researchers, decision-makers and other stakeholders throughout the research process. Glover (2015), for example, stressed that influencing meaningful change is dependent upon reaching the right people. Connecting with a knowledge mobilisation specialist at the beginning of the project would also help generate ideas regarding different methods of dissemination and incorporate the cost of such methods into the budget. Furthermore, incorporating our study participants into the KM plan would have provided an additional opportunity to exchange knowledge and power. Unfortunately, due to the timing of the pandemic, we were unable to return to the participants to invite them to share their perspectives on the vignettes and conversation guides. As a result, we turned to (knowledge translation expert) and (friend). Importantly, though, as we discovered with this study, a KM plan should also be fluid and flexible enough to provide space for researchers to change course after reflecting on their findings and determining that evocative and affective dissemination methods are most appropriate for different audiences.

Conclusion: The next kairotic moment

A research study typically follows a chronological order, beginning with the proposal, moving through data collection and analysis, followed by KM. This chronological flow contains kairotic opportunities where researchers can slow down, reflect, collaborate and consider what is most appropriate in that moment. Taking advantage of these kairotic moments allows space to move toward multimodality. Beyond our own experiences and lessons as we navigated our own kairotic moments to share our data beyond the traditional academic article, we propose a broader kairotic moment for academics to grapple with as they aim to find relevant ways of sharing their research with a range of audiences. We invite researchers to attend to what is appropriate in the moment in order to have the greatest impact. Price (n.d.) noted the lack of attention paid to kairotic moments and spaces within academia. Perhaps with greater consideration of the significance and quality of these informal, social, high stakes moments where we give deeper contemplation to the exchange of knowledge and power, researchers can adopt multimodality in both their peer-reviewed work and their non-traditional KM. We encourage academics to embrace the situational context of a research study while making the most of critical moments to create and share knowledge and power in ways that are relevant to all potential audiences. In doing so, we may all be better situated to ask, and answer, why does this research matter, and for whom, as posed in the call for papers for this special issue. In our case, this research matters as a means of challenging the tragedy discourse of dementia that our society holds while providing practical, useful tools that are widely available for academics, service providers and the general public.

Going beyond the bounds of the traditional journal article allowed us the freedom to represent data differently and embrace multimodality within our work. In our study, our participants reminded us of the importance of living in the moment within the context of dementia. Friends emphasised taking time, slowing down and being with the person with dementia wherever they were at during that particular moment in time. We, in turn, learned to ‘go with the flow’ in our research journey, consider each moment as it came, and make the most of the opportunities that both presented themselves to us (for example, meeting over breakfast in a hotel restaurant) and those we created (for example, advocating to extend the timeline of the study to enable us the flexibility to incorporate multimodality into our writing). In this project, these kairotic moments led to changes in our non-traditional KM. In the future, however, we intend to explore these moments more fully to better understand how they shape our contributions to peer-reviewed work. We will apply our methodology proposed here to our academic writing in the future, and challenge ourselves to incorporate more visual and auditory aspects in peer-reviewed work.

References

Baert, BMT 2020, Kairos: The right moment or occasion, Institute for Advanced Study, viewed 9 August 2024, https://www.ias.edu/ideas/baert-kairos

Boydell, K & Croguennec, J 2022, ‘A creative approach to knowledge translation: The use of short animated film to share stories of refugees and mental health’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 19, no. 18, pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811468

Braun, V & Clarke, V 2006, ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Calonia, J 2024, What is kairos? History, definition, and examples, Grammarly, viewed 9 August 2024, https://www.grammarly.com/blog/kairos/#:~:text=Kairos%20is%20a%20rhetorical%20appeal,the%20greatest%20impact%20and%20urgency

Fletcher, J 2022, Making the most of the opportune moment, Rhetorical Thinking, viewed 23 August 2024, https://rhetoricalthinking.com/2022/09/12/making-the-most-of-the-opportune-moment/

Fortune, D, Whyte, C & Genoe, R 2021, ‘The interplay between leisure, friendship and dementia’, Dementia, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 2041–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301220980898

Genoe, MR & Dupuis, SL 2012, ‘“I’m just like I always was”: A phenomenological exploration of leisure, identity and dementia’, Leisure/Loisir, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 423–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2011.649111

Genoe, MR & Fortune, D 2024, ‘Resisting stigma’, in C Russell, K Gray & J Twigg (eds), Leisure and everyday life with dementia, Open University Press, pp. 117–30.

Genoe, MR, Whyte, C & Fortune, D 2022, ‘Strategies for maintaining friendship in dementia’, Canadian Journal on Aging, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 431–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980821000301

Glover, T 2015, ‘Leisure research for social impact’, Journal of Leisure Research, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2015.11950348

Grimshaw, J, Eccles, M, Lavis, J, Hill, S & Squires, J 2012, ‘Knowledge translation of research findings’, Implementation Science, vol. 7, pp. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-50

Gurukkal, R 2022, ‘Knowledge translation: A challenge in research’, Higher Education for the Future, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 129–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/23476311221110342

Merriam-Webster n.d., Kairos, viewed 9 June 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/kairos#:~:text=kai%C2%B7%E2%80%8Bros,the%20opportune%20and%20decisive%20moment

Mitchell, G, Dupuis, S & Kontos, P 2013, ‘Dementia discourse: From imposed suffering to knowing other-wise’, Journal of Applied Hermeneutics, vol. 5, pp. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.55016/ojs/jah.v2013Y2013.53220

Price, M n.d., Defining kairotic space, viewed 9 June 2024, https://kairos.technorhetoric.net/18.1/coverweb/yergeau-et-al/pages/space/defining.html

Rutter, D & Fisher, M 2013, Knowledge transfer in social care and social work: Where is the problem?, PSSRU Discussion Paper 2866, Personal Social Services Research Unit.

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) 2024, Definition of terms, viewed 26 April 2024, https://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/programs-programmes/definitions-eng.aspx#km-mc

United Nations 2024, International day of friendship, viewed 13 November 2024, https://www.un.org/en/observances/friendship-day

Whyte, C, Fortune, D & Genoe, R 2022, ‘Maintaining friendships after a dementia diagnosis can spur feelings of joy and self-worth’, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/maintaining-friendships-after-a-dementia-diagnosis-can-spur-feelings-of-joy-and-self-worth-187038