Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 18, No. 2

July 2025

Research article (peer-reviewed)

Place-Based Learning and Community Stewardship: A Framework for Facilitating Community Engagement

Áine Bird*, Frances Fahy, Kathy Reilly

University of Galway, Ireland

Corresponding author: Áine Bird, a.bird4@universityofgalway.ie

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v18i2.9192

Article History: Received 19/06/2024; Revised 03/02/2025; Accepted 04/03/2025; Published 07/2025

Abstract

Community stewardship involves active participation and responsibility from local residents in collectively caring for and managing their shared environment and its resources. The essential role of community stewardship lies in its capacity to foster sustainable behaviours, empowering communities to make informed decisions, and driving positive, lasting impacts towards a more environmentally conscious future. A key challenge presented in much of the related literature is how to engage citizens in community stewardship initiatives. This article aims to address this challenge by exploring the theoretical and practical aspects of community stewardship, using the Heritage Keepers national initiative in Ireland as a case study. The article navigates the complexities of community stewardship, acknowledging diverse perspectives within communities and the importance of scale in stewardship activities. It explores the intersection of place-based learning and stewardship, emphasising the need for a holistic approach.

The article is based on a five-year practitioner-led doctoral project undertaken while the primary author was embedded in a community stewardship initiative in the west of Ireland. Various methodologies are employed that reflect both practitioner and community-based research principles. The methodology and findings presented were guided by the central research question: How can place-based learning enhance community stewardship? Emerging from the empirical research conducted as part of a change-oriented community-university research initiative, this article presents a practical framework to support the process of community stewardship. Specifically, the article identifies five key elements central to the community stewardship process; these include: Care, Knowledge, Facilitation, Agency, and Action. Enhancing and under-pinning each of these is Collective Action. By synthesising these elements, the framework offers valuable insights for researchers and practitioners seeking to implement similar community stewardship initiatives, moving community stewardship beyond a conceptualisation to a series of sequential and operational steps that can be implemented across a variety of contexts.

Keywords

Community Stewardship; Place-Based Learning; Scale; Community-University Partnership; Ireland

Introduction

I found it a wonderful programme for people like me who didn’t think their voice could be heard, but now I feel that there are people who help and encourage everyone to protect nature, the environment, and the heritage of an area. (Heritage Keepers Community Participant, 2023)

There is an ever-increasing need for greater attention and action from society to address climate change and biodiversity loss. To meet the urgency of such challenges there is a role for small scale, grassroot, ground-up initiatives (with the potential to develop into something more significant) (Jans 2021). Central to this is a marked shift away from more traditional, hierarchical approaches where the state bears sole responsibility for society, moving instead towards partnerships that acknowledge the interdependencies between state bodies, NGOs and the economy in addressing sustainability and environmental issues (Hajer et al. 2015). Communities taking action to explore local issues to enhance their local places results in immediate impact but can also be a catalyst for future action (Foster-Fishman et al. 2006). Studies have demonstrated that involving various interest groups in decision-making can contribute to a process that garners broader interest, acceptance and sustained engagement among community members (for example, Dawson et al. 2021). Findings presented in this article point towards the role which community stewardship (discussed in greater detail later in this article) can play in harnessing the power of communities to address local challenges, while simultaneously empowering and enhancing the capacities of communities.

This article presents a case study based on a five-year practitioner-led doctoral project, where the primary researcher was embedded in a community stewardship initiative in the west of Ireland. While conceptual framings of community stewardship exist, there is a lack of literature relating the theory to practice (Couceiro et al. 2023). Addressing this, the aims of this article are two-fold. Firstly, we identify and discuss the elements that play a significant role within successful community stewardship initiatives. Secondly, we propose a practical framework that supports the process of ‘doing’ community stewardship, moving beyond a conceptualisation of community stewardship to consider how the concept might be operationalised through communities and programs in a range of contexts. The article embeds practitioner experience and empirical data in a theoretical discourse, providing a framework that informs future research considering the community stewardship paradigm. It also most usefully outlines the necessary elements for others looking to facilitate community stewardship in their setting. We examine the underlying processes and their interrelationships in the act of facilitating and promoting community stewardship.

The next section of the article reviews existing literature in the fields of community stewardship and place-based learning, before outlining the research context and methodology. The results and emergent framework are presented, followed by a detailed exploration of the framework elements. The article concludes by considering the future implications for both community stewardship practice and research.

Conceptualising community stewardship and place-based learning through existing literature

Community stewardship has become an increasingly popular approach for managing natural resources and promoting sustainable development in many parts of the world (Couceiro et al. 2023; Peçanha Enqvist et al. 2018), and this also is reflected in recent calls for more research in this area (Dawson et al. 2021). Depending on the context, there are multiple meanings, definitions and understandings of the term stewardship and by extension, community stewardship (Bennett et al. 2018). The stewardship approach emphasises local participation, collaboration, and empowerment in the management of natural resources and the promotion of social and economic development (Berkes 2009). In the context of this article, stewardship is defined as place-specific actions to which individuals and communities directly contribute their time (Carnell & Mounsey 2022). An adapted version, community stewardship refers to the actions of groups of people. These groups can be gatherings of people who share a place, common interest, goal, or cause (for example, development associations, schools, environmental advocacy groups, or sports clubs). In a review of conservation efforts, which also considered local community well-being, Dawson et al. (2021) indicates that the majority of studies showcasing positive impacts on both well-being and conservation predominantly emerge from situations where Indigenous peoples and local communities hold a pivotal position. Conversely, interventions overseen by external organisations, which aim to alter local practices and replace customary institutions, tend to yield less effective conservation outcomes while concurrently leading to adverse social consequences. While community stewardship has been recognised for its potential to enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of conservation and development initiatives, there is still much to be learned about how to effectively engage communities in stewardship activities (Moser & Bader 2023). Addressing these questions is central to the work informing this article.

Place-based learning takes a holistic view of place, involving the acquisition of knowledge about a specific place while being physically immersed in that place and with the central purpose of enhancing that place. Commentary around the growing disconnect between people and places more broadly has been present for a long time (Relph 2008). According to Relph (2008), establishing a connection to specific places serves as a practical basis for confronting significant challenges, both local and global, such as climate change and economic inequality. However, as suggested by Massey (2004), the significance of place and locality should be tempered by an understanding of, and connections to, broader geographical contexts and global requirements for example globalisation, economics and movement of people. Massey (2004) suggests that we now see ‘the global construction of local place’ where the essence of a place does not solely stem from its internal activities; rather, it also arises from the blending and interaction of external influences, connections, and relationships.

The way individuals connect with and strive to safeguard a place has been recognised to be influenced by scale (Lopez & Weaver 2023). Connection to place and scale are central to this article and the Heritage Keepers program. Scale, as it relates to the potential for interdisciplinary academic study, is discussed in detail by Friis et al. (2023). They unpack the potential confusion around terminology and metaphors related to scale, encompassing concepts like local, regional, national, and global by acknowledging that these phrases can be used with specific analytical or political objectives in mind. In the context of Heritage Keepers and community stewardship, several dimensions of scale are considered including the participants themselves (individual, group or community), the geographic area of focus (local, national or global) and the topic of focus (relating to a specific place or a broader issue such as climate change or biodiversity loss). These issues were considered by Lopez and Weaver (2023), where they looked at those that engage with stewardship initiatives and considered the impact of scale, finding that micro-motivations play a crucial role in steering stewardship within smaller community-based organisations, while macro-motivations are instrumental in influencing engagement in larger, multi-jurisdictional organisations. They also (importantly in the context of Heritage Keepers) emphasise that the proposed binary is oversimplified, and it is more appropriate to perceive this distinction as a flexible continuum rather than a rigid dichotomy. This also echoes the findings of Ardoin (2014), who identified a noteworthy correlation between the scale of actions and the level of place connection held by a volunteer. Individuals with stronger local-scale place connections were notably more inclined to take action on a smaller scale, whereas those with larger-scale place connections were significantly more prone to engage in actions on a larger scale.

Understanding why people do or do not protect their environment is a central consideration when proposing a community stewardship approach. While this article provides insight into the elements that play a role in successful stewardship initiatives, it is important to note that determining why people undertake environmental actions is a vast area of study in its own right and detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this article (for examples, see Huoponen 2023; Kollmuss & Agyeman 2002). Numerous factors drive individuals to form deep connections with nature, and these factors can serve as motivation for endorsing conservation initiatives (Pascual et al. 2022). A multi-faceted combination of factors, encompassing social integration, the exploration of shared values, the reinforcement of environmental identity, self-efficacy, and agency is required to cultivate stewardship (Nelson et al. 2022). However, there is a significant body of evidence suggesting that an individual’s values and world view play an important determining role in their pro-environmental behaviour (Kollmuss & Agyeman 2002; Sockhill et al. 2022). Gallay et al. (2016) contribute to this discourse by examining place-based stewardship education, arguing that such education nurtures a sense of responsibility and commitment to safeguarding rural communal spaces. This approach not only promotes aspirations for environmental protection but also encourages community engagement, emphasising the vital role of education in fostering a sense of environmental stewardship. Furthermore, enabling a holistic comprehensive viewpoint of the factors that influence community stewardship plays a significant role in fostering sustainable environmental behaviours (Ojala 2017). Across the various approaches, what emerged as crucial was the need to select an approach based on particular objectives and the intended audience (Grilli & Curtis 2021). Grilli & Curtis (2021) also consider the lack of knowledge around the degree to which behaviours are sustained beyond programs or research studies.

The study this article is based on explores the intersection of place-based learning and community stewardship. The methodology and findings presented were guided by the central research question: How can place-based learning enhance community stewardship? The following section first outlines the research context before discussing the research methodology.

Case study context

Community stewardship as an approach is not widely employed in Ireland but is growing in recognition and application, particularly in small locally specific contexts (for example, where the community engages and takes responsibility for the care and management of a landscape feature such as a bog or beach) (Flood et al. 2022). Ireland has a very rich natural, cultural and built heritage, and is also characterised by diverse communities (urban and rural; newcomers and long-term residents). This article explores community stewardship and place-based learning through the lens of the Heritage Keepers program in Ireland. Launched in 2022, this initiative assists schools and communities in exploring and improving their local environments through workshops and the development of local action plans (discussed later in this article).

The Heritage Keepers program was developed as part of a practitioner-led doctoral research project, marking it as the first of its kind in Ireland. This collaborative effort involved the Burrenbeo Trust (hereafter Burrenbeo), a community-based organisation, and the University of Galway, focusing on researching evaluation, best practices, and scaling-up of place-based learning and community stewardship initiatives. The lead author, embedded in Burrenbeo through an employment-based PhD funding scheme by the Irish Research Council, was both an employee and researcher bridging theory and practice by assuming dual roles in both the organisation and academic community. This strategic framework promotes collaborative inquiry and knowledge co-creation, offering nuanced insights into real-world challenges and fostering contextually relevant solutions (Brannick & Coghlan, 2007).

The strong university-community partnership fosters mutual learning and capacity building, enriching understanding of key issues. Campbell et al. (2016) highlight the benefits of embedded researchers in building trust and sustaining engagement beyond research projects, though challenges like conflicting priorities and potential conflicts of interest must be managed (Vinke-de Kruijf et al. 2022). Haverkamp (2021) stresses ethical considerations in community research, advocating for a transformative approach that prioritises care, cooperation, and marginalised empowerment. Lopez (2020) frames community geography as an interdisciplinary model aligning academic research with community needs. This article reinforces these themes, emphasising local knowledge, co-ownership, and sustainable, community-driven solutions that amplify marginalised voices, enhance environmental monitoring, and cultivate long-term academic-community collaboration.

Engaging local communities with heritage and environmental themes through place-based learning initiatives is at the core of Burrenbeo’s mission. As previously mentioned, the primary author was embedded in Burrenbeo during this practitioner-led research project. Burrenbeo, an independent membership charity headquartered in Kinvara, County Galway, primarily serves the Burren region in the west of Ireland. Since 2008, they have been actively coordinating and executing various programs that aim to connect individuals with their surroundings, highlighting the community’s role in protecting these places. These initiatives encompass community and school-based activities such as walks, talks, community festivals, training events, and conservation volunteering. Burrenbeo’s work is grounded in the principles of place-based learning and community stewardship, reflecting the work of Smith and Sobel (2010) who focused on the power of local learning to encourage community action.

The Heritage Keepers program, launched in 2022, supports schools and communities in taking local actions for heritage conservation. It involves a series of place-based learning workshops that culminate in the development of a local action plan. Participants can seek funding of up to €1000 to implement their plans and receive ongoing guidance from Burrenbeo. The program’s design, delivery, and outcomes were shaped through consultation with an advisory committee and by adapting existing Burrenbeo programs. The experience of program facilitation amongst Burrenbeo’s staff informed the program development and four of the team were involved in program delivery. The team has expertise in biodiversity, archaeology, education, community engagement and communications. Program delivery has included groups ranging from two-teacher rural schools to community groups in large urban areas, highlighting the adaptability of the approach and the potential for delivery across a broad scale (for further detail on the Heritage Keepers program see Bird & Reilly 2023).

Heritage Keepers workshops, lasting 10 hours in total over a five-week period, were delivered by the Burrenbeo team to a diverse range of participants, including primary and post-primary school groups, adult community groups, teachers, and community facilitators (who were tasked with delivering the program in their own setting). These workshops, offered both online and in person, encouraged participants to explore their local environments, discover resources related to their heritage, envision the future of their places, and plan actions to realise their vision. The workshops fostered interactive and engaging discussions, focusing on the concept of community stewardship and collaborative heritage engagement. Importantly, the action plans developed through the workshops were crafted by the participants themselves, ensuring that they reflected the specific place-based concerns and aspirations of each community. Since the program was initiated, almost 1000 participants from 177 different schools and communities have completed the 10 workshop hours resulting in almost 50 local action projects, 18 local heritage fieldtrips and micro-financing of over €40 000 to groups and schools. The initial funding for the program was provided through a three-year partnership with the Irish Heritage Council from 2021–2023. Subsequently, the program has been funded through a combination of grants and philanthropic sponsorship. Average school group sizes are 18 children or young people, and average community group sizes are five people.

Methodology

This article incorporates a range of methodologies reflecting both a practitioner and community-based research ethos. The primary author is a practitioner-researcher who led the development, coordination and facilitation of the Heritage Keepers program. Frances Fahy and Kathy Reilly, geography lecturers at the University of Galway, supervised the research project, providing guidance and expertise throughout the study. This article provides analysis of data relating to the initiative, followed by reflection and interrogation of the literature resulting in the development of a proposed framework. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected over a 12-month period (May 2022 to May 2023) across the country. Specifically, surveys and focus groups were employed in this study to explore the lived experiences and perceptions of community members and facilitators, and provide context-specific insights into the dynamics of the community stewardship process. Limited demographic information was collected relating to the location of participants (rural or urban) and gender. The questions relating to demographics were not compulsory.

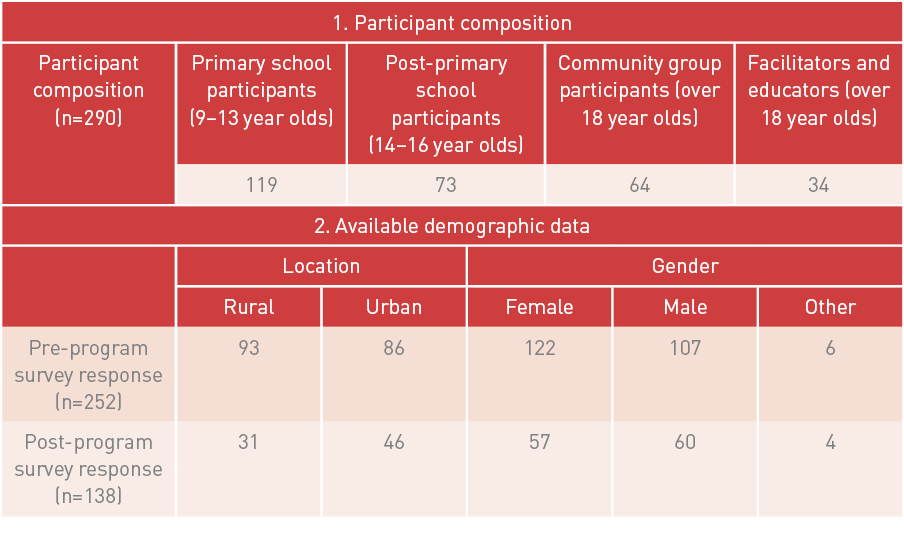

Table 1. Participant composition and demographic data

Participants were recruited for the Heritage Keepers program via an open call seeking expressions of interest, advertised through national media, existing networks and contacts. Some community groups were from pre-existing organisations (for example, a local development group). However, participants were encouraged to create new groups, amalgamating existing local groups where possible, for instance, one from a local sports club, one from a Tidy Towns group, one a local business owner, and one a newcomer to the area.

The titles of the five two-hour workshop sessions were: Introduction and My Place; Culture and the Past; Biodiversity and Land Use; The Future; and Planning for Action. The study received ethical approval from University of Galway and anonymity was maintained during data collection, analysis and reporting, using pseudonyms for participant identities. The analysis of participant data in this study was conducted by comparing pre-program (n=252) and post-program (n=138) completed surveys. The total participant number was 290 meaning there was an 87 per cent response rate to the pre-program survey and a 48 per cent response rate to the post-program survey. Survey responses provided insight into the impact of the program on the participants’ community stewardship perceptions and behaviours. Questions asked participants to evaluate the extent to which they feel connected to their local community, take pride in their area, are driven to address local challenges, feel overwhelmed by issues such as climate change and biodiversity loss, and assess their understanding of local heritage. For information on the survey questions used in this study, please contact the corresponding author. There was also an opportunity to provide open-ended responses, including a question detailing any positive actions participants had taken that were inspired by the Heritage Keepers program. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss every question asked on the survey and as a result we include only that data stemming from the survey questions that concern this article’s aims and objectives (for further detail on the Heritage Keepers program see Bird & Reilly 2023).

As well as the survey data, evaluation data was also obtained through focus groups where the four Burrenbeo staff facilitators participated in a semi-structured focus group to provide qualitative feedback on the program’s effectiveness, successes and challenges. Pre-circulated discussion topics included workshop content, delivery methods (for example, facilitator training, online or in-person), administration, and next steps. This format ensured key themes were covered while allowing space for new ideas to emerge. Insights highlighted strengths like participant engagement and learning outcomes, as well as challenges such as logistical issues and resource gaps. This multi-faceted approach to data collection ensured a comprehensive understanding of the program’s outcomes and effectiveness. As the PhD researcher was simultaneously the practitioner implementing the program, the feedback coupled with the survey results, could inform the program evolution in real time.

Thematic analysis was employed to identify and interpret patterns, themes, and meanings within the collected data, following the methodologies of Braun, Clarke and Weate (2016) and Fram (2013). This involved an iterative coding process, beginning with the importation of qualitative survey data into Excel, where each question was assigned an individual sheet. Data items were thoroughly reviewed and initial codes were applied to capture the essence of each response. For instance, the response, ‘Yes ... by encouraging participants to try something similar in their own communities ... e.g., a heritage walk,’ was coded as ‘Encouraging replication in own community’. These initial codes were then refined and grouped into broader categories through constant comparison, enabling consistent and relevant categorisation. For example, codes such as ‘Learning about monuments’ and ‘Discovering information on ringforts’ were combined under the theme ‘Learning about built heritage’. Once coding was complete, a holistic analysis was conducted, examining the dataset as a whole to identify overarching patterns and connections. This rigorous and iterative approach ensured that the final themes accurately represented the data and provided meaningful insights.

Findings and discussion

The following section outlines the key elements of the community stewardship process as engaged by this study and situated within existing literature. This is followed by a discussion outlining an emergent framework supporting community stewardship processes from the perspective of the Heritage Keepers program. The points outlined are not mutually exclusive and the inherent interconnections are discussed later in the article. In the community stewardship literature, the work of Peçanha Enqvist et al. (2018) resonated particularly strongly. These authors examined various stewardship contexts and identified three critical elements for effective initiatives (care, knowledge, and agency), all underpinned by the concept of collective action. The framework proposed in this article extends Peçanha Enqvist et al.’s work by adding two additional elements: facilitation and action, while also expanding on care, knowledge, and agency. Although Peçanha Enqvist et al.’s framework offers a valuable theoretical foundation for exploring community stewardship, it lacks detailed guidance on the practical steps needed to implement each of its core components. The findings outlined in this article and the developed framework result from an applied approach that moves beyond theory and into practice.

Care

The first element we consider is care. At its most basic, care in the context of community stewardship is concerned with the participant’s emotions and feelings about their local place. Care addresses the sense of connectedness participants feel toward their place helping to identify what people value about their local place and how they would like their place to be in the future.

The Heritage Keepers surveys revealed that participants already felt a significant sense of belonging in their communities before participating. Participants were asked pre- and post-workshop to indicate their degree of agreement with the statement ‘In the last month, I have felt part of my local community’. Pre-workshops, 49 per cent responded ‘A lot’, 42 per cent responded ‘A little’ and 10 per cent responded ‘Not at all’. Post-workshop, the respective responses were 55 per cent, 35 per cent and 10 per cent. This was not anticipated but upon reflection indicates that those who already feel a sense of belonging may be more invested in their place and more likely to engage in a process such as that offered by Heritage Keepers. The possibility of their prior involvement with, and knowledge of, other participants and the place is also significant here.

Expanding on this, the insights suggest that without a sense of connection, people are unlikely to engage in stewardship behaviours. West et al. (2018) explore care as foundational to stewardship, emphasising its practical expression. This viewpoint highlights the need for fostering relationships and ethical values in stewardship initiatives, guiding communities toward sustainability.

A challenge emerges regarding the language used in discussing environmental, heritage, climate, and biodiversity issues. The scientific and academic community often prioritises precise language, which may not resonate with local communities seeking more emotive and story-based communication approaches (Tait 2021). To cultivate affection and commitment toward local places, an assets-based approach is beneficial, focusing on strengths, resources, and community capacities rather than solely addressing needs (Mathie & Cunningham 2005). Similarly, Toomey (2023) argues that facts alone do not sway public opinion on conservation; acknowledging the role of experiences, values, and emotions in communication is crucial. Heritage Keepers workshops allow participants to explore and express their feelings about their local environments.

Of note also when considering the degree to which people care about their environments is the methods that have been used historically to engage people in conservation and environmental issues. The approach proposed through Heritage Keepers while acknowledging the issues that exist, maintains a focus on first identifying the existing positive elements and then subsequently on the actions which can be taken, shifting from a fear-based lens to one which empowers. This emphasis on what can be achieved was reflected in feedback from one of the participants who noted ‘[T]he positivity of the participants about their own place and what they can do to improve it’. Historically there has been an over reliance on ‘Fear Appeal’ where the worst case scenarios are described in an attempt to scare people into caring and action – this approach is often counter-productive (Stoknes 2014). It has since been suggested that people may experience ‘Apocalypse Fatigue’ and choose (knowingly or unknowingly) to disengage from the issue (Nordhaus & Shellenberger 2009). Several inconclusive studies have tried to measure the impact of fear-based approaches to encouraging action around climate change and the environment (Kothe et al. 2019).

The focus on care contends that for community stewardship initiatives to be successful, participants must care about the topics, place or community in question. The sense of belonging and connection to a place and community can be a key factor in this, as are the methods employed to encourage caring.

Knowledge

It could be argued that the knowledge element of building community stewardship is the simplest – premised on the idea that if people have information and skills, they can take the required action. However, knowledge as an element of a community stewardship process is often reductively oversimplified and does not receive adequate consideration. Returning to Peçanha Enqvist et al. (2018), they include the importance for community stewardship initiatives to engage basic information about the place, acknowledging that various knowledge sources are required and relevant for the community to engage with stewardship. However, findings from the Heritage Keepers initiative point specifically to the exact knowledge required, and consideration for how such knowledge is delivered becomes apparent. Post-workshops all participants were asked, ‘What was your favourite part of the program?’ In response, a theme emerged around the discovery of resources facilitating participants learning more about their local place. Another theme related to how much participants had learned, for example, from free online websites and demonstrations on how to use the resources.

Practical information is crucial for community projects. Precise details and procedural steps are necessary for communities to successfully execute projects. This need for clarity was evident in post-workshop support and focus group discussions with staff facilitators. Communities required targeted knowledge to avoid mistakes, such as correctly placing a wildlife pond to preserve biodiversity or using safe techniques for historic graveyard surveys. Additionally, information must be condensed to avoid overwhelming the participants. While abundant resources exist, like those from the All-Ireland Pollinator Plan and Heritage Council, targeted and simplified content proved effective in the Heritage Keepers initiative. Although customising information for each community is labour intensive, key guides (for example, ‘Top Ten Tips for Pond Building’) and facilitator support mitigated this. Despite the national scale of the program, information provided was specific to local contexts and needs.

Not all knowledge is equal. As Bonnett (2023) outlines, while factual knowledge and skills remain important, there is other knowledge, such as embodied knowledge one has through experience of a place or community. In the context of community stewardship, embodied knowledge may be even more important than other knowledge. Bonnett argues that this established knowledge serves as a foundation for more conceptual understanding, helping to counterbalance excessive human-centred utilitarian approaches, speaking again to the notion of care and how we view our environments. The Heritage Keepers initiative encourages engagement with knowledge from within the local community whether it be from farmers, storytellers, musicians, local historians or a local business owner. Arguments have been made for a more critical pedagogy of place to replace scientific dominance prevalent in Western culture and education (Tsevreni 2011). Pretty (2011) examines the significance of local knowledge of nature as a guiding force for actions and decision-making in a place-based approach, thus fostering a deeper connection between individuals and their natural surroundings.

The final element to consider around the knowledge required for successful community stewardship initiatives is capacity building. Capacity building, in the context of empowering communities and facilitating community stewardship, refers to the process of equipping individuals and groups with the knowledge, skills, resources, and confidence they need to effectively take control of their own development, make informed decisions, and manage their local resources and affairs. Regardless of the project undertaken, building the capacity to identify local actions, plan and complete them has a value for communities. As one participant noted, ‘The online sessions were inviting, and so empowering, by sharing resources that can guide myself and our group to seek out places to care for’.

Facilitation

In considering community stewardship in the context of the Heritage Keepers program, it is important to consider the role and importance of facilitation. For Heritage Keepers, the program is facilitated by a member of staff who directs the activities, moderates discussions and supports action plan delivery. In general, a facilitator empowers each individual to engage and learn with the group, both collaboratively and experientially (Creswell 2003). One of the findings identified from the post-program surveys was that groups reported that the process of engaging with facilitated activities and workshops can shed new light on local issues and assets, propose new ways of thinking about their place and community, in addition to shifting dynamics in existing groups. The facilitation experience can also be fundamental for groups who have come together specifically for the program in question. The presence of an external facilitator leading the group through exploration of their place can provide an objective view on the local place, which can be useful in determining where the group’s action would be best focused (Nelson & McFadzean 1998). This does require the facilitator to have a certain skillset and competencies, some of which include creating empathy, being specific, being genuine, engendering respect, listening effectively and, very importantly, gaining trust (Hughes 1999). The model employed in the Heritage Keepers program follows the well-recognised approach where instruction is not imposed, rather a space is created for participants to explore for themselves the elements of their place and community and their desires for its future, facilitated by conversation (Sharples et al. 2006). While facilitation is central to the success of the program and proposed framework, further research on more emergent community stewardship (where an action is undertaken without external support or facilitation) would also be useful. This was not the focus of this study.

Agency

Arguably the most critical element in achieving positive outcomes from community stewardship processes is agency. Considering the potential for communities to respond to environmental problems, Adams et al. (2019) emphasise the importance of understanding the political economy, arguing that power imbalances and unequal distribution of resources can hinder collective action and perpetuate socio-ecological problems. They also discuss the role of social capital, trust and collaboration in fostering effective collective action. Peçanha Enqvist et al. (2018) include agency in their framework as the abilities and capacities of communities or individuals to carry out actions. Essentially, do the structures and supports needed to carry out stewardship actions exist? Are the planned actions feasible, given the specific conditions for the group in question? There were some specific findings that emerged following the analysis of the data from the Heritage Keepers program, which spoke directly to the importance of agency. Over the years, various programs with a similar focus, delivered by Burrenbeo, have encouraged action, and while participants on these previous programs indicated in post-program surveys that they felt encouraged to take action, it very rarely actually resulted in action – could this have been because the agency element had not been adequately considered in these earlier programs? When developing Heritage Keepers, financial support via micro-financing for the initiatives was added. We now argue that this innovation, alongside the provision of ongoing support and mentoring for participants while they complete actions has resulted in the program’s positive outcomes. These elements ensure that local schools and communities were supported to complete the actions they had identified. Equally, the process of engaging with the Heritage Keepers workshops as outlined, assisted the participants in identifying areas where they could have an impact in their area.

Drawing on experience of delivering previous programs to a wide range of groups and individuals lead to the specification of the Heritage Keepers program being exclusively developed for groups (rather than individuals). While acknowledging that this may exclude those that do not already have connections within their community, or feel safe or welcomed in community spaces, practitioner experience suggested that it was often too much for one person to be tasked with taking on a community stewardship action. In addition, group participation makes space for collective participatory decision-making and the emergence of a community mandate. The groups that participated could be pre-existing, and groups were encouraged to connect (for example, a representative from existing local groups or societies came together to form a local Heritage Keepers group).

Action

It may seem unnecessary to include action as a separate element when the assumption is that if the goal is community stewardship that an action will result, however it is useful to add some specifics here from the Heritage Keepers perspective. In deliberately focusing the program around the identification of, planning for, and completion of local heritage actions, the program provides a clear and achievable goal for participants. This echoes the earlier suggestion from Grilli and Curtis (2021) that in encouraging pro-environmental behaviours identifying a very specific objective was a good approach. Equally, Oinonen et al. (2023) highlight the importance of strengthening young people’s beliefs in their ability to make a difference and produce desired sustainability outcomes.

For each participating Heritage Keepers group, deciding on the particular action and refining the plan if required is supported by the facilitator (who as previously mentioned can provide a useful outside perspective). Examples of actions which have been completed by participants include: development of heritage trails; publication of oral history records; creation of biodiversity areas; celebration of notable figures; community networking events; art installations; digging of wildlife ponds and many more. While the scale and legacy impact of work involved is different in each setting, actions look for ‘small wins’ (Foster-Fishman et al. 2006), showing that a community can achieve something if they set out to (providing the necessary elements are present). This also builds on the earlier discussion of ‘Apocalypse Fatigue’ (Nordhaus & Shellenberger 2009). Peters et al. (2013), in a discussion of fear-based approaches to encouraging action, found that prioritising efficacy was most effective – in this case, the power of the group to complete their desired action.

However, it could be argued that this focus on an often discrete action is one of the weaknesses in this type of work as it does not allow for a longer-term consideration of stewardship behaviours of participants. It would be desirable to build in a mechanism to continue to engage with and monitor the actions of participants beyond the timeframe of the program to establish whether the actions that were initiated were continued, developed, expanded or simply finished once the program ended.

Collective action

The final point to address is collective action, where individuals are motivated by seeing their efforts contribute to a larger cause, knowing their ‘small wins’ are bolstered by similar successes across the country. Collective action is increasingly recognised as crucial for advancing global environmental initiatives (Gulliver et al. 2022). While some may equate collective action solely with activism (Gulliver et al. 2022), Heritage Keepers participants have found that connecting with other communities, both online and through culminating showcase events, enriches their experience by sharing challenges and learning from others’ achievements. One participant remarked, ‘The accomplishments of other Heritage Keepers … was amazing to hear and see. It certainly has encouraged our group to complete our projects and take on other aspects within our community’. This underscores the earlier discussion on the need for multi-level action to tackle challenges collectively, where shared initiatives alleviate the workload. The role of networks and social movements, extensively discussed in literature (Saunders 2013), resonates with participants who value connecting with like-minded individuals passionate about their environments and evidenced by the participant who said, ‘Great to connect with people who feel the same passion about their own place/environment as I do’.

Nelson et al. (2022) in their Climate Stewards program in America highlight the importance of early connections in fostering shared beliefs and values among participants. Groups involved in Heritage Keepers bring diverse backgrounds and experiences, collaborating to build local knowledge and engage with other community groups, enhancing peer learning and knowledge exchange. The nature of the groups and the interactions between the groups is something that will be discussed at a later stage.

In summary, collective action is pivotal in community stewardship, amplifying individual efforts into a unified movement towards environmental sustainability. The next section will delve into practical applications of the community stewardship process, drawing on insights from the Heritage Keepers program and existing literature to provide a framework for researchers and practitioners.

Reflections on an emergent framework

Before discussing the elements of the community stewardship process and the suggested framework, we start with a broader look at scale and the scaling-up of environmental and sustainability actions. Participants from the Heritage Keepers program engage immediate local actions while also representing integral parts of larger social and spatial assemblages. The works of Lopez and Weaver (2023), Ardoin (2014) and Massey (2004) all point towards the role of scale in community stewardship initiatives. Essentially, recognising one’s place on a scale beyond the local enhances understanding of how individual actions can collaborate with others, contributing to broader transformative change (Ardoin 2014). Equally important in this context is the move from a focus on actions taken by an individual, to collectively supported actions within a group, building on social capital bonds to positively facilitate meaningful action (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Framework for the process of community stewardship

The elements comprising the community stewardship process interact in intricate and dynamic ways. The framework identifies five distinct elements integral to the overall process. However, the nuanced relationship between knowledge and caring (Kollmuss & Agyeman 2002), underscores a reciprocal connection. Individuals may find themselves in a symbiotic relationship where caring is propelled by knowledge acquisition, or conversely, the pursuit of knowledge is fuelled by pre-existing care. This interplay resonates with discussions on ‘information deficit’ models and the ‘value-action gap’ within environmental action (Blake 1999). These discussions suggest that individuals’ engagement in environmental initiatives hinge on their awareness and understanding, emphasising the interconnectedness of knowledge acquisition and the manifestation of caring attitudes. Relatedly, the proposed framework elements are part of an iterative process and at times participants may return to earlier steps in the process, particularly if their engagement with community stewardship is ongoing (as would be desired) rather than a single occurrence. For example, participants may first focus on a local archaeological feature, learn about it, feel a connection and engage in an action associated with it. Over the course of the engagement, they may discover a specific ecological feature connected to the site leading to further ideas for research and emerging actions.

Critically reflecting on the research conducted and emergent framework, it is clear that the process of facilitating community stewardship is a complex yet crucial endeavour. To support and encourage communities in becoming stewards of their local places, facilitation is key. A skilled facilitator can create a supportive and inclusive atmosphere, encouraging active participation and empowering participants. In recognising and valuing the diverse perspectives and experiences within communities, the facilitator fosters a sense of belonging and shared responsibility, essential for successful community stewardship initiatives. In the process of facilitating community stewardship, the knowledge shared must be easily digestible and relevant to the community’s needs and interests. Complicated jargon and technical information can be overwhelming and disempowering. Instead, the process should employ clear, concise, and accessible language, making complex concepts relatable and digestible for all participants. Sharing resources and building capacity among participants supports informed decision-making, ensuring that stewardship efforts are well-informed and sustainable.

Emotional connection proves pivotal in community stewardship, motivating individuals to protect and conserve their environment. Utilising storytelling, personal experiences, and cultural ties may evoke emotions that resonate. While this article explores community stewardship through participant perspectives, a key question arises: how can we increase involvement from non-participants? Further investigation into fostering emotional connections could drive future research on enhancing community stewardship. The Heritage Keepers program exemplifies how engaging in this process promotes stewardship behaviours, including sustainability, conservation, and responsible management of local environments. Additionally, collective action among participants nationwide reinforces these behaviours, uniting toward shared environmental goals and catalysing impactful change.

This study faced several limitations that merit consideration. Although the research spanned a longitudinal period (2018–2023) and benefited from the researchers’ prior familiarity with and knowledge of the organisation, more comprehensive follow-up could provide deeper insights. For instance, conducting in-depth interviews with participants might offer a richer understanding of their experiences, and long-term follow-up could determine whether participants continued their civic engagement after completing the Heritage Keepers program. However, maintaining participant interest and involvement over such an extended timeframe presents its own challenges. Additionally, the open call for participation may have resulted in a less representative sample, potentially limiting the broader applicability of the findings. Future research could address this by actively targeting underrepresented groups within the organisation’s audience. Finally, while embedding the research within Burrenbeo contributed to its success, reliance on a single organisation may have introduced biases linked to its specific aims and resources. Subsequent studies could benefit from examining a broader range of organisations and contexts to enhance the robustness and generalisability of the findings.

Building on the experience described in this article, the Heritage Keepers program in 2023 and 2024 focused its delivery on primary schools, youth organisations and community groups, with a further 140 participant groups completing the program in this time. The program is funded for 2025 and ongoing grant applications will hopefully ensure it continues successfully for years to come.

Conclusion

As outlined above, there are multiple factors determining whether community stewardship initiatives are successful. For the purposes of this study, successful initiatives are those which achieve the aim of facilitating local community action. The first element, Care, highlights the significance of cultivating an emotional connection and sense of responsibility towards local community and place. In fostering a deep sense of care and attachment, community members are motivated to protect and preserve their surroundings, thereby providing a strong foundation for stewardship behaviours. Future research on how care is initiated (and the influencing factors) would be useful to explore through the community stewardship lens. The second element, Knowledge, emphasises the significance of the accessibility and relevance of the information shared during the process as well as the significance of diverse knowledge, such as experiential and embodied knowledge. By presenting information in a digestible and meaningful manner, participants are empowered to make informed decisions, contributing to informed and effective stewardship practices. The third element, Facilitation, plays a pivotal role in the community stewardship process, creating an inclusive and supportive environment that encourages active participation and ownership. Effective facilitation ensures that diverse perspectives are valued and integrated within decision-making processes, driving collaborative and community-driven initiatives. The fourth element, Agency, acknowledges the importance of supports and external drivers in empowering participants in their stewardship efforts. This element is fundamental for any successful community stewardship, providing an opportunity for initiatives (across a variety of scales) to be implemented. There is also a need for further research around community stewardship legacy (that is, once the specific supports provided by programs are no longer available). The fifth and final element, Action, relates to the tangible, measurable and achievable goal(s) attained through the process. We have presented these findings as a practical framework that is readily adaptable by similar initiatives. As outlined previously, this work has been developed via an embedded practitioner-researcher in partnership with a university. The applied nature of the work as well as the fact that the project is ongoing could be viewed as testament to the value of an embedded practitioner research design.

When communities are provided with the necessary tools and support, they may emerge as powerful agents of positive change for their environment. By fostering a sense of ownership, belonging, and collective responsibility, the journey towards community stewardship becomes a collaborative and empowering experience. It is through this process of partnership and active engagement that communities can truly become champions of their place and environment, ensuring a greener and more resilient future for generations to come.

References

Adams, LB, Alter, TR, Parkes, MW, Reid, M & Woolnough, AP 2019, ‘Political economics, collective action and wicked socio-ecological problems: A practice story from the field’, Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, vol. 12, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v12i1.6496

Ardoin, NM 2014, ‘Exploring sense of place and environmental behavior at an ecoregional scale in three sites’, Ecology, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 425–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-014-9652-x

Bennett, NJ, Whitty, TS, Finkbeiner, E, Pittman, J, Bassett, H, Gelcich, S & Allison, EH 2018, ‘Environmental stewardship: A conceptual review and analytical framework’, Environmental Management, vol. 61, pp. 597–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0993-2

Berkes F 2009, ‘Indigenous ways of knowing and the study of environmental change’, Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014220909510568

Bird, Á & Reilly, K 2023, ‘From local to national – lessons from a community stewardship perspective’, Irish Geography, vol. 56, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.55650/igj.2023.1480

Blake, J 1999, ‘Overcoming the “value-action gap”’ in environmental policy: Tensions between national policy and local experience’, Local Environment, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839908725599

Bonnett, M 2023, ‘Environmental consciousness, nature and the philosophy of education: Matters arising’, Environmental Education Research, vol. 29, no. 10, pp. 1377–1385. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2023.2225807

Brannick, T & Coghlan, D 2007, ‘In defense of being “native”: The case for insider academic research’, Organizational Research Methods, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106289253

Braun, V, Clarke, V & Weate, P 2016, ‘Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research’, Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise, Routledge, pp. 213-227. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315762012-26

Campbell, LK, Svendsen, ES & Roman, LA 2016, ‘Knowledge co-production at the research–practice interface: Embedded case studies from urban forestry’, Environmental Management, vol. 57, no. 6, pp. 1262–1280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-016-0680-8

Carnell, R & Mounsey, C 2022, Stewardship and the future of the planet: Promise and paradox, Routledge, New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003219064

Couceiro, D, Hristova, IR, Tassone, V, Wals, A & Gómez, C 2023, ‘Exploring environmental stewardship among youth from a high-biodiverse region in Colombia’, Journal of Environmental Education, vol. 54, no. 5, pp. 306–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2023.2238649

Creswell, JW 2003, Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 2nd edn, Sage Publications, California.

Dawson, NM, Coolsaet, B, Sterling, EJ, Loveridge, R, Gross-Camp, ND, Wongbusarakum, S, Sangha, KK, Scherl, LM, Phan, HP, Zafra-Calvo, N, Lavey, WG, Byakagaba, P, Idroo, CJ, Chenet, A, Bennett, NJ, Mansourian, S & Rosado-May, FJ 2021, ‘The role of indigenous peoples and local communities in effective and equitable conservation’, Ecology and Society, vol. 26, no. 3. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12625-260319

Foster-Fishman, PG, Fitzgerald, K, Brandell, C, Nowell, B, Chavis, D & Van Egeren, LA 2006, ‘Mobilizing residents for action: The role of small wins and strategic supports’, American Journal of Community Psychology, vol. 38, no. 3–4, pp. 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-006-9081-0

Flood, K, Mahon, M, & McDonagh, J 2022, ‘Everyday resilience: Rural communities as agents of change in peatland social-ecological systems’, Journal of Rural Studies, 96, pp.316–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.11.008

Fram, SM, 2013, ‘The constant comparative analysis method outside of grounded theory’, The Qualitative Report, vol. 18, no. 1. http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR18/fram1.pdf

Friis, C, Hernández-Morcillo, M, Baumann, M, Coral, C, Frommen, T, Ghoddousi, A, Loibl, D & Rufin, P 2023, ‘Enabling spaces for bridging scales: Scanning solutions for interdisciplinary human-environment research’, Sustainability Science, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 1251–1269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01271-3

Gallay, E, Marckini-Polk, L, Schroeder, B & Flanagan, C 2016, ‘Place-based stewardship education: Nurturing aspirations to protect the rural commons’, Peabody Journal of Education, vol. 91, no. 2, pp. 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2016.1151736

Grilli, G & Curtis, J 2021, ‘Encouraging pro-environmental behaviours: A review of methods and approaches’ Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110039

Gulliver, R, Star, C, Fielding, K & Louis, W 2022, ‘A systematic review of the outcomes of sustained environmental collective action’, Environmental Science & Policy, vol. 133, 180–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.03.020

Hajer, M, Nilsson, M, Raworth, K, Bakker, P, Berkhout, F, de Boer, Y, Rockström, J, Ludwig, K & Kok, M 2015, ‘Beyond cockpit-ism: Four insights to enhance the transformative potential of the sustainable development goals’, Sustainability, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 1651–1660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7021651

Haverkamp, J 2021, ‘Where’s the love? Recentring indigenous and feminist ethics of care for engaged climate research’, Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, vol. 14, no. 2. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v14i2.7782

Hughes, C 1999, ‘Facilitation in context: Challenging some basic principles’, Studies in Continuing Education, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037990210102

Huoponen, A 2023, ‘From concern to behavior: Barriers and enablers of adolescents’ pro-environmental behavior in a school context’, Environmental Education Research, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 677–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2023.2180374

Jans, L 2021, ‘Changing environmental behaviour from the bottom up: The formation of pro-environmental social identities’, Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101531

Kollmuss, A & Agyeman, J 2002, ‘Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior?’, Environmental Education Research, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145401

Kothe, EJ, Ling, M, North, M, Klas, A, Mullan, BA & Novoradovskaya, L 2019, ‘Protection motivation theory and pro-environmental behaviour: A systematic mapping review’, Australian Journal of Psychology, vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12271

Lopez, CW 2020, ‘Community geography as a model for improving efforts of environmental stewardship’ Geography Compass, vol. 14, no. 4. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12485

Lopez, CW & Weaver, R 2023, ‘What influences where volunteers practice environmental stewardship? The role of scale(s) in sorting stewards’, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, vol. 66, no. 9, pp. 1983–2008. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2022.2049596

Massey, D 2004, ‘The responsibilities of place’, Local Economy, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 97–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/0269094042000205070

Mathie, A & Cunningham, G 2005, ‘Who is driving development? Reflections on the transformative potential of asset-based community development’, Canadian Journal of Development Studies, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2005.9669031

Moser, S & Bader, C 2023, ‘Why do people participate in grassroots sustainability initiatives? Different motives for different levels of involvement’, Frontiers in Sustainability, vol. 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2022.994881

Nelson, SM, Ira, G & Merenlender, AM 2022, ‘Adult climate change education advances learning, self‐efficacy, and agency for community‐scale stewardship’, Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031804

Nelson, T & McFadzean, E 1998, ‘Facilitating problem-solving groups: Facilitator competences’, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437739810208647

Nordhaus, T & Shellenberger, M 2009, ‘Apocalypse fatigue: Losing the public on climate change’, Yale Environment 360. https://e360.yale.edu/features/apocalypse_fatigue_losing_the_public_on_climate_change

Oinonen, I, Seppälä, T & Paloniemi, R 2023, ‘How does action competence explain young people’s sustainability action?’, Environmental Education Research, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 499–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2023.2241675

Ojala, M 2017, ‘Hope and anticipation in education for a sustainable future’, Futures, vol. 94, pp. 76-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2016.10.004

Pascual, U, McElwee, PD, Diamond, SE, Ngo, HT, Bai, X, Cheung, WWL, Lim, M, Steiner, N, Agard, J, Donatti, CI, Duarte, CM, Leemans, R, Managi, S, Pires, APF, Reyes-García, V, Trisos, C, Scholes, RJ & Pörtner, HO 2022, ‘Governing for transformative change across the biodiversity-climate-society nexus’, BioScience, vol. 72, no. 7, pp. 684–704. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biac031

Peçanha Enqvist, J, West, S, Masterson, VA, Haider, LJ, Svedin, U & Tengö, M 2018, ‘Stewardship as a boundary object for sustainability research: Linking care, knowledge and agency’ Landscape and Urban Planning, vol. 179, pp. 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.07.005

Peters, GJY, Ruiter, RAC & Kok, G 2013, ‘Threatening communication: A critical re-analysis and a revised meta-analytic test of fear appeal theory’, Health Psychology Review, vol. 7, pp. S8–S31. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2012.703527

Pretty, J 2011, ‘Interdisciplinary progress in approaches to address social-ecological and ecocultural systems’, Environmental Conservation, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892910000937

Relph, E 2008, ‘Senses of place and emerging social and environmental challenges’ in A Williams, Sense of place, health and quality of life, Routledge, London, pp. 51-64

Saunders, C 2013, Environmental networks and social movement theory, Bloomsbury Academic, London. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472544490

Sharples, M, Taylor, J & Vavoula, G 2006, ‘A theory of learning for the mobile age’ in The Sage Handbook of Elearning Research, pp. 221–247. https://telearn.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00190276 https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607859.n10

Smith, G & Sobel, D 2010, ‘Bring it on home’, Educational Leadership, vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 38–43.

Sockhill, NJ, Dean, AJ, Oh, RRY & Fuller, RA 2022, ‘Beyond the ecocentric: Diverse values and attitudes influence engagement in pro-environmental behaviours’, People and Nature, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 1500–1512. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10400

Stoknes, PE 2014, ‘Rethinking climate communications and the “psychological climate paradox”’, Energy Research and Social Science, vol. 1, pp. 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2014.03.007

Tait, A 2021, ‘Climate psychology and its relevance to deep adaptation’ in J Bendell & R Read (eds), Deep adaptation: Navigating the realities of climate chaos, pp. 105–123. Polity.

Toomey, AH 2023, ‘Why facts don’t change minds: Insights from cognitive science for the improved communication of conservation research’, Biological Conservation, vol. 278, 109886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109886

Tsevreni, I 2011, ‘Towards an environmental education without scientific knowledge: An attempt to create an action model based on children’s experiences, emotions and perceptions about their environment’, Environmental Education Research, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 53-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504621003637029

Vinke-de Kruijf, J, Verbrugge, L, Schröter, B, den Haan, RJ, Cortes Arevalo, J, Fliervoet, J, Henze, J & Albert, C 2022, ‘Knowledge co-production and researcher roles in transdisciplinary environmental management projects’, Sustainable Development, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2281

West, S, Haider, LJ, Masterson, V, Enqvist, JP, Svedin, U & Tengö, M 2018, ‘Stewardship, care and relational values’, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 35, pp. 30-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.008