Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 17, No. 1

June 2024

Practice-based article

Greenspace & Us: Exploring Co-design Approaches to Increase Engagement with Nature by Girls and Young Women

Stuart Cole1, Jessica Goodenough2, Melissa Haniff3, Nafeesa Hussain4, Sahar Ibrahim3, Anant Jani5*, Emily Jiggens6, Ansa Khan4, Pippa Langford7, Louise Montgomery7, Lizzie Moore6, Rosie Rowe6, Sam Skinner8

1 Oxfordshire County Council Innovation Service

2 Oxford City Council Greenspace Development Team

3 Resolve Collective

4 Name It Youth Project/Oxford Youth Enterprise

5 University of Oxford

6 Oxfordshire County Council Public Health

7 Natural England

8 Fig Studio

Corresponding author: Anant Jani, anant.r.jani@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v17i1.8881

Article History: Received 27/10/2023; Revised 30/01/2024; Accepted 05/04/2024; Published 06/2024

Abstract

Nature connection through engagement with greenspaces plays an important role in promoting well-being. In England, certain groups, such as girls and young women from disadvantaged backgrounds, have limited access to high-quality greenspaces and face other barriers to engaging with nature. In Oxfordshire, the County Council has committed to improving access to greenspace and nature for all. In 2022, a group consisting of twenty girls and young women (aged 10–16) from East Oxford not-for-profit organisations, academic institutions and public bodies came together to start an initiative called ‘Greenspace & Us’. The girls and young women participated in six three-hour workshops in February to March 2022. Using the COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour) approach, we explored the enablers and barriers to girls and young women in Oxford engaging more with nature, which included: increasing equity of access; introducing meaningful co-production; taking safety concerns seriously; making nature normal; promoting the right to play; and increasing the ability to connect with greenspaces. The outputs of this process were synthesised into the ‘Greenspace & Us Manifesto’, which was crafted collectively. Furthermore, these insights were used to design inclusive park furniture, which was later installed in a local park in East Oxford. In this practice-based article, we outline the methods, outcomes as well as the strengths and weaknesses of the engagement, co-design and co-production approaches we used in Greenspace & Us. We hope the insights from our project will support more inclusive and equitable design of greenspaces for all.

Keywords

Young Women; Greenspaces; Inequalities; Nature Connection; Co-design; Wellbeing

Introduction

Nature accessibility, engagement and connectivity play crucial roles in promoting physical and mental well-being (Fields in Trust 2022). However, certain groups encounter significant obstacles when attempting to access and engage with green and natural spaces. Natural England’s People and Nature Survey reveals a substantial decline in nature connection between the ages of 9 and 15, with no recovery to childhood levels (Richardson 2019). Additionally, Sport England’s Active Lives survey identifies a decline in physical activity among teenagers, particularly impacting girls and young women, who struggle to regain a healthy level of physical activity (World Health Organization 2022). These challenges are particularly pronounced for girls from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, who not only have limited access to high-quality greenspaces, but also face other barriers hindering their engagement and connection with nature, many of which remain poorly understood and go unrecognised in traditional narratives on greenspace use.

A recent Mental Health and Wellbeing Needs Assessment for Oxfordshire County in England highlights a sharp decline in self-reported well-being among young people aged 13-16, with teenage girls being especially vulnerable to depression and anxiety, and generally poor mental health (Arbuthnott 2021). Although disengagement from broader well-being enablers is believed to be a central factor contributing to this trend, local insights explaining this phenomenon are scarce.

To advance the county’s goal of creating a greener, healthier and more equitable environment, at the time of this project, Oxfordshire County Council’s Fair Deal Alliance had identified ‘improving access to greenspace and nature’, ‘prioritizing the health and well-being of residents’ and ‘addressing inequalities in Oxfordshire’ as key priorities in nine focus areas. A consultation conducted in Autumn 2021 revealed that young people had increasingly prioritised spending time in greenspaces during lockdown (Arbuthnott 2021). They also expressed concerns about the potential impact of new housing developments on access to greenspaces and that they felt a lack of socialising opportunities.

In order to enhance knowledge and understanding of the barriers to and facilitators of girls and young women engaging with and using greenspaces, as well as co-designing approaches to increase their engagement with and use of greenspaces, a group consisting of girls and young women from Oxford not-for-profit organisations, academic institutions and public bodies came together to introduce an initiative called ‘Greenspace & Us’. Greenspace & Us is a co-production community-based partnership project that aims to address three questions:

(1) What is the current utilisation of greenspaces by young women and to what degree does it fulfil their requirements?

(2) What factors act as obstacles or facilitators in influencing the access, engagement and connection of young women with greenspaces and nature?

(3) What co-design and co-production approaches can be used to create solutions to increase greenspace and nature engagement and use by girls and women in Oxfordshire?

The answers to question 1 are documented in a publication produced for Natural England (Cole et al. 2023). In this practice-based article we present the results linked to questions 2 and 3; we outline the engagement as well as the co-design and co-production approaches we used, the outcomes of these approaches, and reflections on the strengths and weaknesses of these approaches. Our hope is that these insights may help other groups engaging in similar work in the future to reimagine the narrative around natural spaces.

Greenspace & Us Methods: Participatory and Creative

Greenspace & Us aimed to first understand the perceptions and needs of girls and young women, and through this process, to then use these insights to contribute to the co-design and co-production of effective approaches to engaging young people in matters related to the built and natural environment. The methods employed were participatory, creative and empowering, ensuring equitable knowledge sharing with participants and fostering sustainable relationships with the young people and community-based organisations working to represent and help realise their interests.

The methods were devised by a collaborative working group comprising representatives from Oxfordshire County Council, the University of Oxford, Name It Youth Project (Oxford Youth Enterprise) and Fig.Studio, overseen by Natural England steering group members. For this study, Barton & Sandhills in the OX3 ward and Rose Hill & Iffley, Littlemore, Northfield Brook and Blackbird Leys in the OX4 ward of East Oxford were selected as the geographical context due to the higher levels of deprivation in these areas, (Insight.oxfordshire.gov.uk, 2023) which are also recognised for their inadequate provision of publicly accessible greenspaces. It is important to note that the intention of the project was not to critically evaluate specific sites within East Oxford, but rather to establish a comprehensive understanding of the underlying issues related to nature engagement by girls and young women.

The project development and methodology underwent assessment and approval in accordance with Natural England’s internal ethics review checklist (available upon request). The collection of data as part of the project strictly adhered to the regulations outlined by the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the data processing policy of Oxfordshire County Council. All quotations were anonymised and the photographs were used with the written consent of the individuals involved.

The methodology employed in this study encompassed two main components: participatory workshops and co-production of creative outputs. We discuss each one in turn.

(1) Participatory Workshops

A total of twenty young women, aged 10–16, with a median age of 12 years, were recruited by Oxford Youth Enterprise through various youth organisations operating in the area. The young women had engaged with Oxford Youth Enterprise and a previous project organised by Name It Youth and, as such, there was a strong element of trust between the young women and the enterprise’s youth workers. These participants engaged in a series of six three-hour workshops, conducted in February and March 2022. The decision to set the lower age limit at 10 was made to ensure inclusivity of 10-year-old girls who were already involved in youth work and expressed significant interest in the project.

Among the 20 workshop participants, approximately two-thirds were already engaged with the Name It Youth Project, and each member of the group was acquainted with at least one other participant at the outset of the project. The majority (16 out of 20) of the group resided in the OX4 area, with three living in the neighbouring OX3 area, which hosts some of Oxfordshire’s most deprived wards. One participant, who maintained a strong connection with East Oxford, resided just outside the city in OX13.

While the group represented various ethnic backgrounds, approximately one-third identified as ‘Asian or Asian British’ (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi), or other Asian backgrounds. None of the participants reported having any physical or mental health conditions that might limit their ability to carry out day-to-day activities.

The workshops were facilitated by six female members of the working group, comprising individuals from Oxfordshire County Council Public Health, Name It Youth Project, and RESOLVE Collective. The decision to maintain a female-only space and foster a safe environment for open discussion was made during the early planning stages.

The design and overall approach of the workshops was guided by the COM-B model (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour) of behaviour change; for this project the aimed behaviour change was to support the young women participants to engage more with greenspaces. The COM-B model posits that for any behaviour to occur, individuals must have the capability and opportunity to engage in that behaviour, coupled with a higher level of motivation relative to other behaviours. In addition to informing the methods of data collection, this framework was utilised to structure and summarise the findings of the project (Michie, Atkins & West 2014). The content and specific questions addressed in the workshops were informed by survey data, established models of best practice in engaging young people in matters related to their built and green environments, as well as contributions from youth workers and creative professionals.

Table 1 outlines the workshop program. Content was adapted on a weekly basis, informed by ongoing feedback from participants (‘Check-In’ and ‘Check-Out’ sessions) and weekly facilitator debrief sessions. Except for a local greenspace walkabout, all workshops were held at an East Oxford community garden.

Data collection methods comprised a range of techniques, encompassing flip chart notes/presentations, annotated maps, annotated photos, audio clips, and group discussion notes and thoughts from participants (Figs 1A and 1B). The activities were agreed jointly with the girls/young women and were designed to provide a space for them to share their experiences, perceptions and needs from greenspaces. Sessions 1–3 focused on understanding their experiences and perceptions. Through approaches like the ‘Tree of Change’ (Fig. 1C), coined by the young women, the participants were able to identify the barriers and enablers related to greenspace access that they felt could be realistically changed. These changes were recorded on coloured leaves and, through group consensus, determinations were made regarding their changeability and subsequent incorporation on the tree. The purpose of this method was to stimulate discussion among the young women concerning their perceived ‘reasonable asks’ directed towards decision-makers responsible for their environment.

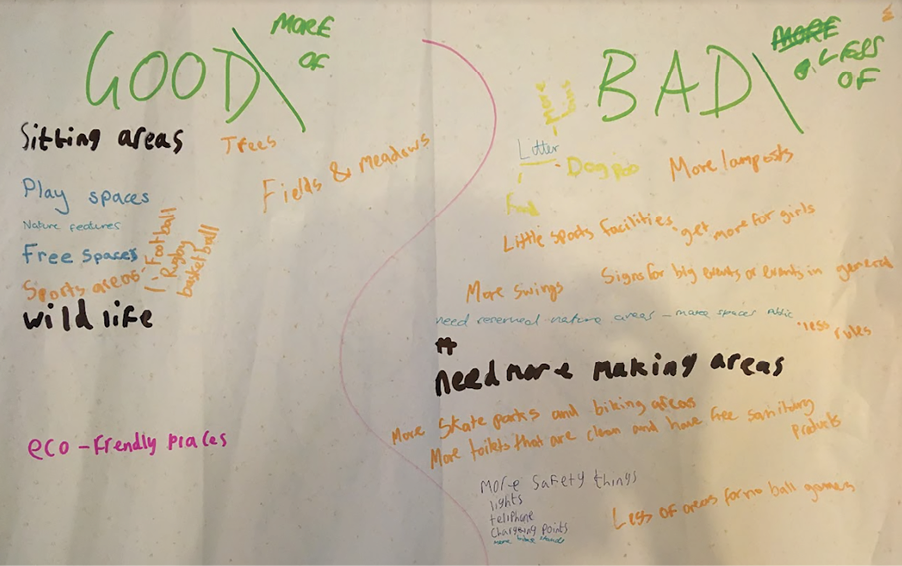

Figure 1. Data collection methods: (A) An example of group mapping work; (B) An example of small group discussion notes and thoughts from participants; (C) Examples of exploratory workshop outputs – The Tree of Change.

(2) Creative outputs

The design and creation of the creative outputs was supported by the RESOLVE Collective. RESOLVE is a design collective that aims to address social challenges through interdisciplinary approaches combining architecture, engineering, technology and art. They conceptualise ‘design’ as including both physical and systemic interventions that can drive political and socio-economic changes. Furthermore, one of their guiding principles is to design with and for under-represented groups, especially young people.

From the outset of Greenspace & Us, RESOLVE Collective introduced the concept of utilising a creative output to articulate the group’s ideas, but they did not impose specific parameters on the format of the output. Sessions 1–3 focused on need finding, followed by sessions 4–6, which involved activities aimed at shaping the narrative surrounding the needs of the young women participants and their role within greenspaces. Participants were supported in drafting a Manifesto to publicly declare their perspectives and intentions, while also exploring their concepts through physical artwork. The group consistently displayed an interest in constructing a tangible structure.

While the creative outputs were regularly discussed throughout the project, substantial progress in their development occurred predominantly during sessions 5 and 6. Decisions were made collaboratively or, when necessary, by vote. Following the conclusion of the sessions, a Celebration Day was organised. This event provided an opportunity for the young women to commemorate their participation and showcase their ideas to family, friends and local stakeholders involved in Greenspace initiatives.

Results

The first three workshops aimed to understand the capability, opportunity and motivation (COM) of the young women participants engaging with greenspaces.

Capability

In the first two workshops it became evident that many participants were unfamiliar with the term ‘greenspace’. Consequently, a considerable amount of time was dedicated to establishing a collective understanding of the diverse range of environments that could fall under the umbrella of ‘greenspace’. The participants eloquently mentioned various natural settings, such as forests/woods, nature reserves, fields/farmland, gardens, lakes/rivers/sea, hills and plains, as well as associated features like trees, plants, flowers, insects, animals, wildlife, fresh air and sunlight. However, despite their comprehensive conceptualisation of greenspace, their lived experiences revealed a more limited picture. During a local greenspace mapping exercise, participants consistently identified, on average, two greenspaces that they frequented regularly – predominantly parks or recreation grounds situated in proximity to their homes or schools. Nature reserves or woodlands, despite their abundant presence in the area, were seldom acknowledged as viable destinations for visits.

Further to this, throughout the project, participants gradually expressed their concerns regarding the equitable distribution of greenspaces, which they perceived as being predominantly dominated by other demographics. This perception was partly influenced by the design of spaces and facilities, which the young women believed catered more to younger children and favoured traditional ‘male’ physical and social activities. Additionally, there was a lack of confidence among these young women to assert their ownership of these spaces.

Opportunities

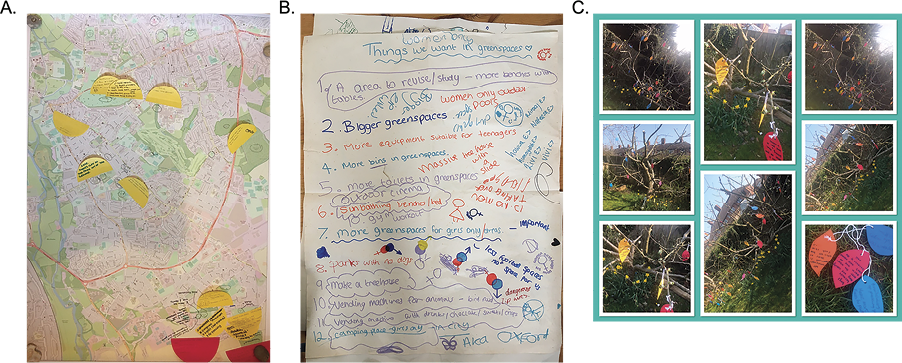

One finding that was particularly interesting was that, despite holding positive ideals, it became evident that the young women’s lived experiences of greenspaces varied within the group, there being both positive and negative experiences. Alongside the positive aspects, they associated negative features with local greenspaces, which elicited feelings ranging from disinterest and distaste to a sense of discomfort or insecurity (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Outputs highlighting the young women’s perceptions of the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ of greenspaces.

The maintenance of public greenspaces emerged as an essential area of concern during several workshops. Inadequate upkeep led to unattractive spaces, where dirty environments and equipment, vandalism, mud, litter and dog waste were more likely to be present. Participants consistently advocated for more waste bins to address the issue of litter and dog waste. Furthermore, the participants highlighted that most of the greenspaces lacked facilities that catered to young women’s basic needs, such as access to food and water, clean toilets, seating and shelter. The lack of sufficiently quiet and safe spaces, in which young women could socialise without being ‘bothered’ by boys or young children, also contributed to rendering greenspaces initially as undesirable and inconvenient, ultimately limiting the amount of time young women could comfortably spend in these areas.

These results challenged the traditional narrative and absolute statements that greenspace was good for health and wellbeing. There was, instead, a set of qualifiers linked to the quality, safety and design of greenspaces that had a great impact on the health and wellbeing benefits that could be expected of such spaces, and the opportunities for different demographics to experience the benefits of greenspaces. If, for example, a young woman were to go to a greenspace and experience bullying or be exposed to unsettling incivilities like drug use, it could harm her mental health and wellbeing.

The participants also highlighted that the competing priorities of school, their social life and other activities, as well as the limited availability and high cost of outdoor sports clubs for girls, had a negative impact on opportunities to engage with greenspaces.

Motivation

During the workshops, a widespread sentiment among many participants was a positive recollection of time spent outdoors. They shared anecdotes of beautiful walks with family members and the joy experienced at organised events. In describing greenspace, words such as ‘fun’ ‘free’ and ‘fresh’ were commonly used, reflecting their positive association with the natural environment. Moreover, workshop participants frequently and articulately acknowledged the positive effects of greenspace on mental health. Their fluency in using language related to wellbeing was particularly evident, signifying their awareness of the significant impact that greenspaces and nature could have on promoting mental health and wellbeing.

Through an exploration of the use of greenspaces, we found that participants predominantly portrayed them as social environments and saw them as tranquil places that fostered feelings of calmness, relaxation, and opportunities for socialising and ‘hanging out’ with friends. The young women also emphasised a desire for more social opportunities within greenspaces, especially those specifically tailored to girls and young women. Such opportunities encompassed a range of organised physical and creative activities, social gatherings, such as outdoor cinema nights and festivals, as well as nature-based experiences. The promotion of gender-specific events and activities emerged as a key aspiration towards fostering a more inclusive and engaging greenspace environment for young women. It also underscored recognition of the positive wellbeing impact associated with play and the call for more age-appropriate equipment to foster adventurous, physical and nature-oriented play.

During the initial workshop discussions, the young women demonstrated a clear understanding of the link between greenspaces and environmental conservation, which was distinct from concerns regarding access. They acknowledged the significance of spaces dedicated to wildlife and nature while also recognising their role in protecting the environment. Furthermore, they displayed awareness of broader environmental issues, such as the use of fossil fuels, plastic pollution, and other forms of environmental degradation. Their perspectives extended beyond personal access to greenspaces, reflecting a broader understanding of the importance of preserving urban greenspaces that serve as habitats for wildlife and contribute to the overall health of nature.

The participants also mentioned several factors that negatively impacted their motivation to engage with greenspaces, some of which were captured in ‘Opportunities’. Some young women associated greenspaces with anti-social behaviour, such as drug taking or gang presence, and expressed apprehension that the lack of activities for teenagers could expose them to such risks. The issue of safety in greenspaces was also framed in terms of broader societal problems surrounding misogyny and gender-based violence, which they perceived as more prevalent in a typically ‘male-dominated’ space. Other young women had direct experiences of gender-based harassment, bullying, or intimidation in greenspaces. Finally, and importantly, there was a sense of disempowerment among the participants that appeared to be linked to a lack of ownership and, consequently, a reduced inclination to engage actively with local greenspaces.

Table 2 summarises the barriers and enablers identified under the headings of Capability, Opportunity and Motivation in workshops 1–3.

| COM-B element | Behavioural influences (barriers and enablers) to co-design and co-production | |

|---|---|---|

| Capability | Psychological (knowledge, cognition, interpersonal skills, self-regulation) | Lack of knowledge of local green spaces or available activities Lack of confidence to claim a male-dominated space |

| Opportunities | Social (peer pressure, social norms, culture, credible role models) | Competing priorities – school, social life and other activities |

| Physical (triggers/prompts, space/time, location/services) | Unable/unsafe to get to green spaces Lack of attractive and well-maintained green spaces nearby Lack of facilities in green spaces to meet basic needs of young women Lack of quiet and protected green space in which young women can socialise Lack of play equipment aimed at older kids and teenagers Not enough/high cost of outdoor sports clubs for girls | |

| Motivation | Automatic (emotions, desires, impulses, habits) | Desire to participate in a wide range of activities in green spaces Desire to visit a wider range of green spaces Green spaces are/can feel unsafe for young women Lack of sense of ownership over local green spaces and exclusion from democratic processes Mixed feelings about ‘nature’ spaces |

| Reflective (plans, intentions, beliefs, identity) | Awareness of the well-being benefits of green space and nature Perception that there is ‘nothing to do’ in green space | |

The Greenspace & Us Manifesto

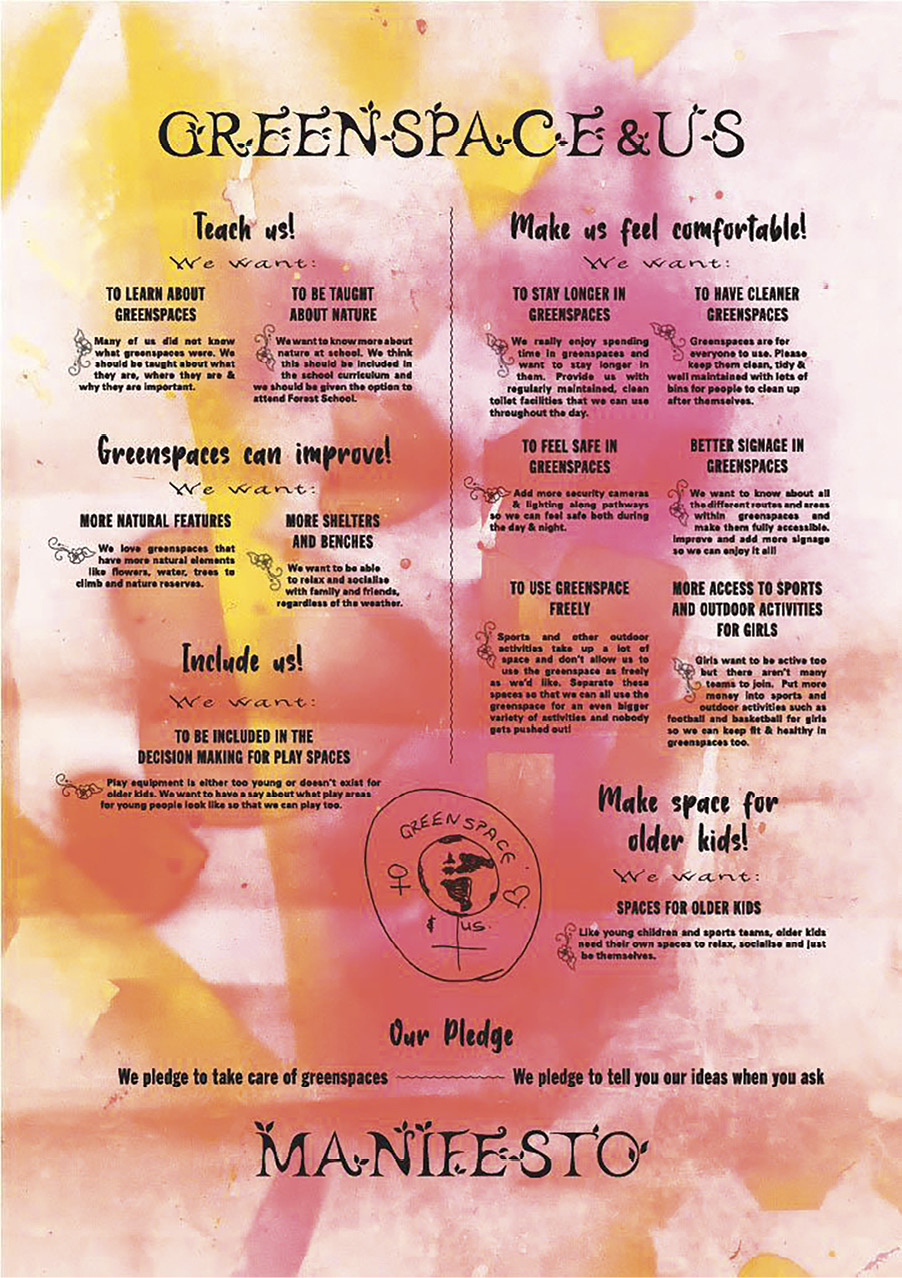

Using the outputs from the COM-B analysis (Table 2), workshop participants collaborated closely with artistic partners, Fig.Studio and RESOLVE Collective, to synthesise their ideas and aspirations (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Participants working on the Greenspace & Us Manifesto.

Accounting for the participants’ experiences, perceptions and needs from the previous sessions, it was clear that a reimagining of greenspaces needed to start with an acknowledgement of the roles that greenspaces fulfilled for girls and young women. For the participants, greenspaces served as a place for social activities and play, as opposed to providing a place for formal/informal sport and physical activity. Translation of these insights yielded a set of concrete ideas on the changes required of greenspaces to meet their specific needs so that they can equitably benefit from the health and well-being benefits that greenspaces can offer.

Specific highlighted needs and preferences included social seating and shelter, amenities (including toilet facilities and bins), security features (such as lighting and cameras), signage, greater consideration of the potential negative impact of designated sports areas on non-core-user demographics, more organised active opportunities for girls, and facilitation of the right to play for older girls, not just boys.

These insights and ideas were synthesised into a comprehensive ‘Greenspace & Us Manifesto’ to support decision makers to understand girls/young women’s needs. The Manifesto’s content and design elements were crafted collectively and later compiled into a final document in the form of a zine with the assistance of a local artist. Figure 4

Figure 4. The Greenspace & Us Manifesto.

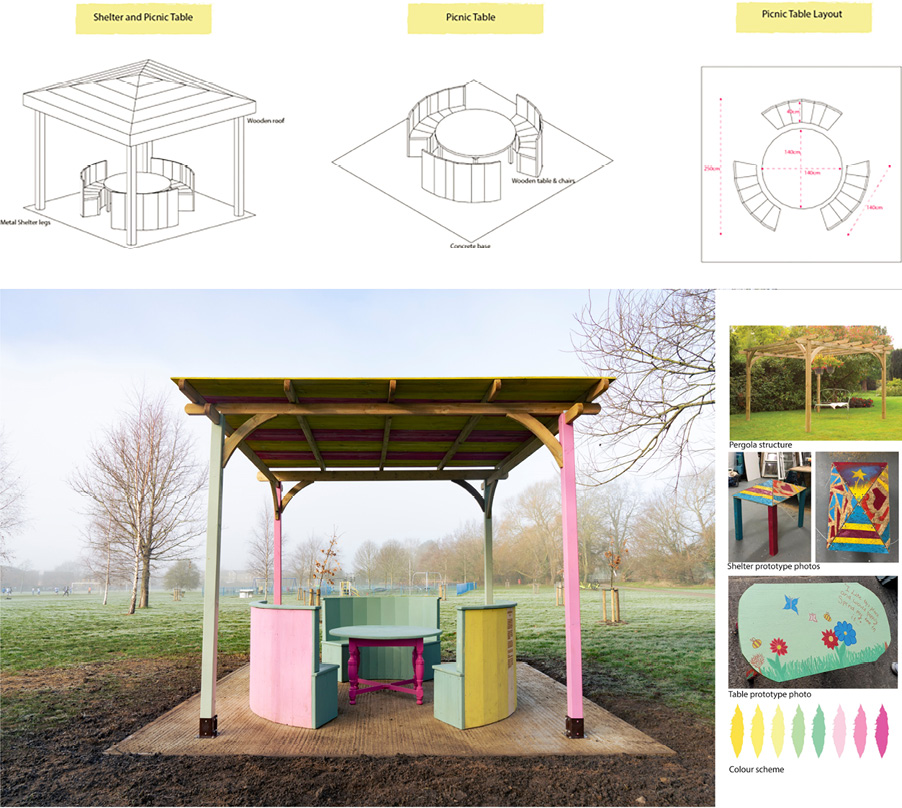

Addressing the recurring discussions on fundamental necessities, such as seating and shelter, participants collaborated with RESOLVE to create a table and shelter combination, representing a prototype of more inclusive greenspace furniture. The young women took an active role in developing and constructing prototype elements, and professional designers refined the concepts with continuous input from the participants (Figure 5). The furniture piece was crafted by a local carpenter and installed in an East Oxford Park, complemented by informative printed boards detailing the project’s objectives and completed with hand-drawn illustrations by the group of young women.

Figure 5. Professional work-up of the table and shelter designed by RESOLVE Collective in collaboration with participants who worked on the prototype. The final structure was built by Toffee Hammer Carpentry and painted using designs and motifs from and by the young women. Final structure photographed by Reuben Worlledge. © Greenspace & Us 2023 and Reuben Worlledge.

As part of the creative workshops, participants deliberated on a ‘strategy’ for presenting the Manifesto and initial design concepts to chosen stakeholders during a celebratory event – the project’s ‘Celebration Day’. Invitations were extended to friends, family, and County and City Councillors, as well as to members of the Public Health Team, Oxford City Greenspace Development Team and Natural England. This strategic outreach ensured that the voices of the young women advocating for more inclusive and fulfilling greenspaces would resonate with influential decision-makers, fostering a culture of active community engagement and empowerment.

Discussion: Recommendations, Lessons Learned and Next Steps

Principles and Recommendations

The aim of Greenspace & Us was to explore how co-design approaches could be used to better understand the barriers and enablers influencing engagement with and use of greenspaces by girls and young women. We also wanted to use these insights to co-design and implement solutions to overcome any barriers and to leverage the facilitators we identified.

Using the COM-B model as our underlying approach, we assembled a collaborative group of girls and young women from East Oxford to identify some of the factors affecting their capability, opportunity and motivation to utilise greenspaces (Table 2). The COM-B model proved useful in capturing and analysing how an apparently simple specific outcome (lack of use of greenspaces) could result from a complex interplay of factors relating to capacity, opportunity and motivation. A limitation to the approach was that there was no prioritisation element in the model that could reveal if certain factors were more important than others in influencing behaviour. Insights on the priorities could have been helpful in directing the use of scarce resources to providing interventions that had the potential to be effective and have the greatest impact. Despite this, we were still able to gain insights from the participants and better able to define the challenges, so as to refine our model and co-create an intervention that aimed to augment enablers and overcome some of the barriers to access identified in the workshops.

One of the most important, but unexpected findings, was a challenge to the traditional narrative regarding greenspace benefit, which was not experienced by girls/young women in this area because it did not equitably meet their needs. In addition to the factors directly linked with the COM-B approach, we identified some principles and recommendations, as highlighted below:

• Equity of access: Understanding of differential access should underpin all decision-making around the design and management of community greenspaces. This includes honest acceptance of how facilities and the distribution of space meet the needs of different demographic groups.

• Meaningful co-production: We can, and must, get better at listening to young people and other marginalised groups, and involve them in decision-making about community outdoor spaces in an age and gender-appropriate way.

• Taking safety concerns seriously: We must listen to young women’s safety concerns about greenspaces and treat them with the same importance and urgency as any other setting.

• Making nature normal: We must build access to greenspace and conversations about nature into the daily lives of young people. We cannot rely on childhood exposure to maintain connection with nature, which is essential for wellbeing.

• The right to play: We have a responsibility to facilitate age and gender appropriate outdoor play for adolescents as well as younger children.

• Connected greenspaces: Physical accessibility to greenspace for young women is as important as the characteristics of the space itself in influencing usage.

Further to this, it is important to note that these principles and recommendations are not directed towards any one organisation or sector (e.g. public, not-for-profit, academic), but highlight general approaches that are likely to assist partnerships in working successfully together. How these principles and recommendations should be implemented will vary based on the target beneficiary’s local needs, local assets, local resource constraints (time, expertise, space, money) and relevant local political priorities. In East Oxford, our consultation with multiple stakeholders, including the Oxford City Council, pointed to the youth shelter and benches (Fig. 5) as being practical and useful solutions to meeting some of the key needs of the girls/young women, as expressed in their Greenspace & Us Manifesto, for which we were able to obtain permission to construct and resource. The model generated by the young women in East Oxford may need to be further refined if it is to be applied to other target populations to allow for variability in response, preference and local resource constraints.

Lessons Learned

The Greenspace & Us project revealed some very interesting, and unexpected, insights into the complexity of collaboration and approaches that can be taken to improve it.

One of the most important factors in our ability to successfully engage with our young collaborators was our partnership with the Name It Youth project. Having worked with local girls and young women in the past, they tend to play a crucial role in project development, recruitment and fostering meaningful relationships. Otherwise, building the level of trust and engagement we achieved would likely not have been possible in the short time-frames we had for this project.

As we began the process of running our workshops, one of the lessons we learned was the importance of being in agreement on the scope of the project and the definitions of the key terms we would use. In the early stages, we took for granted that everyone would have the same understanding of terms like ‘greenspace’. This led to some confusion, but we addressed this by taking a step back and, with our stakeholders, agreed a definition of greenspace, which was important because this process also revealed further insights that informed our understanding of the capability, opportunity and motivation of the participants to engage with greenspaces. In the future, we will take time to create a glossary of key terms with indicative definitions that we will open up to participants to modify as they feel appropriate. We may also experiment with doing this as a pre-workshop exercise that could be done virtually, or the glossary could be given as a pre-read that is then discussed and agreed at the beginning of the workshops.

Our experience in running the workshops also highlighted the benefits of utilising creativity to engage with young people and with public authorities. These creative approaches provided a neutral platform that allowed for the articulation of ideas through different means (e.g. written word, drawing, use of colours) that may not have been possible if there had been a basic focus group approach with just questions and answers that required information to be conveyed only through verbal/written means. Our creative partners skilfully provided a vital medium to enthuse and energise discussions, injecting an element of excitement and joy into the project. By utilising different means of engagement with the girls, young women and other stakeholders over the course of six sessions, we were able to build trust and rapport that allowed for more open and honest discussion, which enabled further collaboration and engagement opportunities.

While navigating the complexity of collaboration, we learned valuable lessons about being led by young people. This process necessitated investing time and resources to align with their pace and terms, which fostered a sense of ownership and empowerment among the youth. At the end of the project, after we had completed the workshops and collected feedback from the girls and young women, they highlighted that they did not always feel like they were being listened to, and although their feedback indicated that they had enjoyed the creative activities, they also mentioned feeling that some of the activities and processes were imposed upon them. This reflects the tension between delivering a research project linked to funding requirements within a relatively short time, and the need to allow time for full co-production. In retrospect, we recognise the potential benefits of fully co-producing methods and outputs, a crucial change that could address the challenge of empowering girls and young women without fostering unrealistic expectations of the project’s scope and influence. Although too late to inform the methodology for this project, it is an important learning that we have been able to build into the design of subsequent projects. Empowering young women and involving them in democratic decision-making processes are crucial steps towards fostering greater community engagement and inclusivity. By encouraging active participation and acknowledging their valuable insights, local authorities can strengthen the bonds between young women and their communities, thus promoting a collaborative approach to creating vibrant and responsive public environments for people and nature.

Using the COM B model allowed the specific insights of the young women to refine and shape our understanding of the various factors influencing their behaviour, resulting in more targeted and effective suggestions for interventions. This approach proved highly flexible as it could be adapted and refined through the workshop process as further insights were identified. It also enabled collaboration between the disciplines, i.e. the arts and public health, and enabled us to bring together diverse expertise and the lived experiences of the young women to better understand and address the barriers and enablers that were identified through the COM-B model.

Finally, when it came time to implement the solutions, we found that we lacked resources, especially money and time. One of the challenges of co-design is that one cannot a priori determine what the solution will be. For us, we lacked sufficient funds to design and build the shelter from the original funding we had for the project; however, we were thankfully able to raise the needed funds through financial support from the County Council and donations from local organisations. We also did not account for the time needed to get permission from the City Council to instal a physical structure in a park. We were able to eventually get permission through the City Council, but there was a delay of several months from the conceptualisation of the idea to raising the additional funding, building the shelter and having it installed in the local park in East Oxford. In the future, we would aim to be much more transparent about resource limitations to avoid creating unrealistic expectations that, if not met, could be very demotivating for the collaborators, especially the girls and young women, who invested so much time and energy in these processes.

Next Steps

Despite the constraints of a tight funding schedule, our commitment to seeing girls and young women in East Oxford increase their engagement with and use of greenspaces continues. The ‘Greenspace & Us’ group, with support from the Name It Youth Project, continues to meet and maintain active conversations with the Oxford City Council’s Greenspace Development Team. This sustained dialogue not only empowers girls and young women to offer their views on greenspace developments in the city, but also ensures that their voices resonate in shaping the future of greenspaces and improving equitable access to the benefits that can be derived from connection to nature.

Additionally, we would like to formally evaluate the impact of the shelter. We are interested, in particular, to determine whether girls from East Oxford, those involved in Greenspace & Us and those from the wider East Oxford community:

- are using the shelter

- what they are using it for

- if they are using it for purposes that they did not articulate during our workshops

- how frequently they are using it, and

- getting a breakdown of the uses based on different demographics.

We would also be interested to know if other groups, apart from girls and young women, have begun to use the shelter. In addition to observing the purposes the shelter fulfils for these groups, we would like to understand the perceptions and attitudes of these users of the shelter, as well as their thoughts on the approach of Greenspace & Us to empowering girls and young women in East Oxford. For example, could other groups feel like they were being excluded because the co-design and co-production group consisted only of selected girls/young women, and could the unintended consequences of our approach lead to greater polarisation within the local community?

Acquiring answers to these types of questions could help us better understand the strengths and weaknesses of our collaborative and co-design approaches. Furthermore, these answers could provide critical insights into the barriers and facilitators of the use of co-designed and co-produced solutions.

We are also interested in exploring other co-designed solutions, such as forest schools or organising group trips to local greenspaces, that adhere to the principles and recommendations above, but may require fewer resources to implement in practice.

Conclusions

The Greenspace & Us project offered a valuable platform for girls and young women to share and contemplate their experiences in accessing greenspaces, while providing public health and other stakeholders with profound insights into the lived reality of this often underserved group. Although centred in East Oxford, many of our findings transcend specific locations and possess broader applicability, especially of the important qualifiers of whether and how greenspaces can deliver health and wellbeing benefits equitably across a population.

Throughout the journey, as participants, facilitators and stakeholders, we collectively identified an array of factors influencing not only behaviour, but also the very essence of young women’s relationship with greenspaces. While some challenges, such as the provision of age- and gender-appropriate play equipment, call for straightforward solutions, others, such as addressing genuine safety concerns and fostering a sense of ownership over public spaces, demand a more nuanced, collaborative and co-production approach. Resolving these complex issues requires unwavering dedication, bold investment decisions, and a united effort alongside young people to achieve equitable access to greenspaces and public areas.

While this initiative was born from public health endeavours, its implications extend beyond the confines of a single sector. Action to dismantle barriers and enhance greenspace accessibility necessitates a shared vision and partnership among planning authorities, greenspace management teams, educational institutions, social work agencies, youth organisations, environmental sector entities, public health, and the broader society. Rather than providing definitive answers, the insights garnered from Greenspace & Us have lain the groundwork for deeper conversations tailored to specific sub-groups of the population, locations and spaces. They also serve as a powerful advocacy tool, advocating for an approach that fosters equity and inclusivity, one that is directly shaped by the voices of those who are often the most underrepresented and who have the most to gain.

Our collaborative journey reflects the intricacies of meaningful engagement and the impact of our collective endeavours extends beyond the project’s scope, leaving an enduring legacy of empowered youth shaping the built and green environments of their community, and continuing to produce further projects.

Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to all our participants and partners for their invaluable contributions and unwavering support. Without them, the realisation of this project would have remained beyond reach. Their commitment has invigorated our pursuit of a greener, more inclusive community for all. We would particularly like to thank:

• All the survey respondents and workshop participants, without whom the project would not have been possible

• Art and design collaborators, CommonBooks, Lisa Curtis and Toffee Hammer Carpentry

• Oxfordshire County Council’s Engagement Team

• Oxford City Council’s Green Space Development Team

• Active Oxfordshire.

References

Arbuthnott, K 2021, ‘Mental wellbeing needs assessment’, Mental Wellbeing in Children & Young People. https://insight.oxfordshire.gov.uk/cms/system/files/documents/MWBNA_Oxon_Dec21_forweb.pdf

Cole, S, Goodenough, J, Haniff, M, Hussain, N, Ibrahim, S, Jani, A, Jiggens, E, Khan, A, Langford, P, Moore, L, Montgomery, L, Rowe, R & Skinner, S 2023, Greenspace & Us: A community insights project to understand barriers and enablers around access to greenspace for teenage girls in East Oxford.

Fields in Trust 2022, Green Space Index: Latest analysis of Great Britain’s publicly accessible park and green space provision. https://www.fieldsintrust.org/green-space-index

Michie, S, Atkins, L & West, R 2014, The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions, Silverback Publishing.

Richardson, M 2019. https://findingnature.org.uk/2019/06/12/teenage-dip

World Health Organisation 2022, ‘85% of adolescent girls don’t do enough physical activity: New WHO study calls for action’. https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/04-03-2022-85-of-adolescent-girls-don-t-do-enough-physical-ctivity-new-who-study-calls-for-action