Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 16, No. 1

November 2023

PRACTICE-BASED ARTICLE

Inciting Change Makers in an Online Community Engaged Learning Environment During Pandemic Restrictions: Lessons from a Disability Studies and Community Rehabilitation Program

Meaghan Edwards1,* and Joanna C. Rankin1

1 Community Rehabilitation and Disability Studies, Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Corresponding author: Meaghan Edwards, meaghan.edwards@ucalgary.ca

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v16i1.8695

Article history: Received 29/06/2023; Revised 21/08/2023; Accepted 16/09/2023; Published 11/2023

Abstract

This practice-based article presents strategies employed in the shifting of the Community Engaged Learning (CEL) components of an undergraduate program in community rehabilitation and disability studies (CRDS) to an online modality during the 2020-2021 Covid-19 restrictions. The CRDS program, based in Calgary, Canada places high importance on CEL with a focus on critical engagement, mentorship, and community action for social justice. The Inciting Change Makers (ICM) framework, which we present here, is foundational to our teaching and learning in this field. During the pandemic restrictions, we found the framework not only supported us to engage learners in our focus areas for inciting change, but also provided the opportunity to consider ways that the online learning environment enhanced the CEL practica experience.

Using vignettes, we demonstrate the successful use of the ICM framework in an online CEL context to develop a more authentic, engaged and inclusive community of learners. Three vignettes illustrate specific approaches used to carry out meaningful, impactful CEL opportunities in a mandated online environment. Lessons from these strategies may assist similar programs in adapting their own Community Engaged Learning programs in an increasingly online world.

Keywords

Online Learning; Disability Studies; Pandemic Restrictions; Community Engaged Learning; Community of Learners; Critical Engagement

Introduction

Disability studies is an area of critical scholarship that finds its roots in the Disability Rights movement and examines how disability is constructed, created and related to in everyday life (Cameron 2013). Disability Studies is concerned with dismantling the ableist systems and structures in society that exclude, marginalise, pathologise and oppress disabled people (Goodley 2011; Oliver 2013). The field of Disability Studies, which emerged as an area of scholarship in the 1980s, has significantly shaped policy such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN-CRPD; United Nations 2006), the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) and the Accessible Canada Act (Government of Canada 2019) and has impacted the design and delivery of disability services and supports on a global scale. Disability studies are now included in many training and post-secondary educational contexts (Goodley 2013), emphasising a theory and praxis connection aimed at social transformation. Community Engaged Learning is particularly important in this field as it is essential to practise disability studies in partnership with disability communities in order to democratise scholarship and promote learning and engagement beyond university walls (Nishida 2018).

One such program, The Community Rehabilitation and Disability Studies (CRDS) program at the University of Calgary, aims to promote justice for people with diverse abilities by delivering programs in the domains of leadership, community capacity development, and innovation. Students who have completed our four-year degree often go on to work in allied health fields and take on leadership positions in advocacy and service organisations. The development of an inclusive and engaged community of learners is central to the CRDS program and provides the support required to carry out the challenging work of critical analysis and community action for social justice. In line with the wider disability studies field, we ask our students to work outside the classroom in community-engaged learning opportunities where they must apply their critical theory skills in community settings, such as disability services and advocacy organisations.

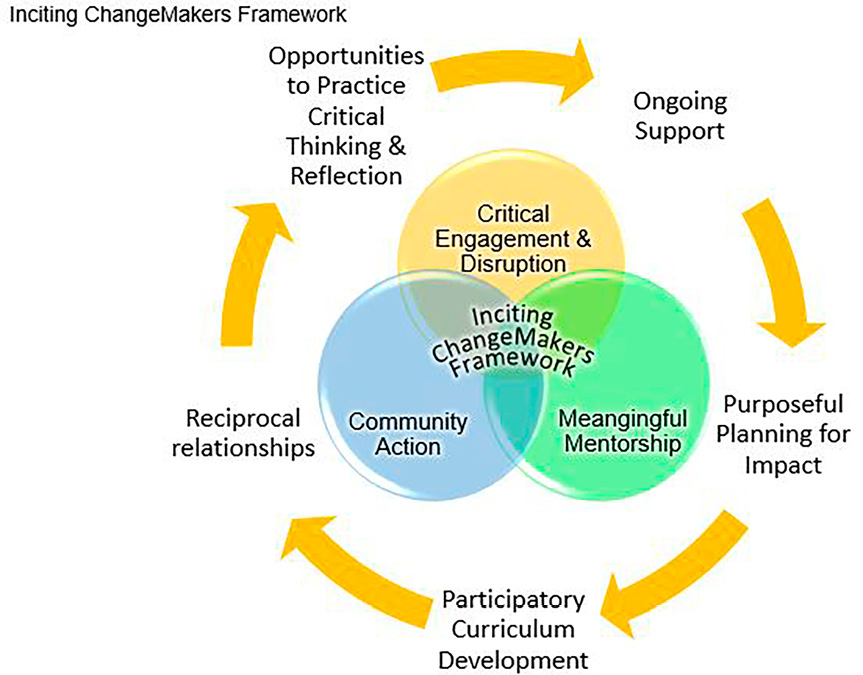

Our Inciting Change Makers (ICM) framework (Figure 1) forms the basis of our educational approach. The ICM provides structure for critical thinking and planning for practical social change. The framework includes three tenets. The first, critical engagement and disruption, supports students to apply critical thinking in their future careers as leaders in community agencies, government organisations, or healthcare settings. The second, meaningful mentorship, recognises that students engaged in the critical work necessary to shift cultural systems of oppression need to be supported by instructors, by one another, and by the community. The third tenet, community action, is focused upon social change and allyship, and is rooted in values of justice and citizenship.

Figure 1. The Inciting ChangeMakers Framework

Community Engaged Learning (CEL) is a key modality through which the ICM operates. Our students learn to design, deliver and evaluate support services, and engage with policy analysis and impact strategies in collaboration with our community partners, including governmental offices, both municipal and provincial, disability service and support organisations, educational settings, Indigenous organisations, advocacy groups and health care settings. This CEL approach aligns with the larger field of disability studies in recognising that social change begins when individuals develop a clearer sense of their own values and begin to understand and critique the political, economic and social conditions that impact their lives, and the lives of community members, through critical thinking and honest dialogue. Our approach to CEL involves mutually beneficial relationships for the purposes of co-learning and co-creating knowledge, in turn contributing to positive social change. Similar approaches have been taken in aligned critical educational fields. Lum and Morton (2012), for example, describe their pedagogical approach within a critical race framework as requiring students to address inequality by examining power, identity and their own privilege when working in community settings. Morton et al. (2019) present a similar position, emphasising the importance of collaboration and partnership in critical community-engaged learning in gender studies.

The transition of education to an online format during COVID 19 restrictions in 2020 and 2021 affected our program at a foundational level as the delivery of the ICM model relied upon CEL-based programming on the ground, at the frontline of services, support and policy development. In the online format, face-to-face mentorship and student interactions were not available. Our community partners who provided CEL practica opportunities to our learners were forced to dramatically change their daily operations during COVID 19. These changes meant that hosting our students in person or even offering extra support online was often impossible. The transition of our CEL programming online was complex and multi-faceted, and we experienced both successes and failures. The ICM framework supported and provided structure for the pivots we undertook in our transition online.

In the following sections, we use short examples, or vignettes, of actual situations that arose in our program during COVID-19 restrictions. We offer one vignette to illustrate each of the three tenets of the ICM (Critical Engagement and Disruption, Meaningful Mentorship, and Community Action) to describe ways the ICM was used pre-pandemic, and the pivoting that occurred by students, instructors and community agencies when forced to move online. Under the three tenets of our framework, we show some of the ways that we used the ICM strategies (opportunities to practise critical thinking and reflection, ongoing support, purposeful planning for impact, participatory curriculum development and reciprocal relationships) in these CEL contexts.

Illustrative Vignettes

ICM Tenet 1: Critical Engagement and Disruption

Our ICM framework provides a way to understand and encourage opportunities for students to apply their critical thinking in CEL experience and in their future careers as leaders in community agencies, government organisations and/or healthcare settings. We ask our students to engage in critical examination as a path to disrupting the systems and structures that create oppression and maintain an ableist culture that actively excludes disabled people.

Preparation to disrupt systemic injustice and uphold disability rights is facilitated through the kinds of critical engagement developed and required in our community-based placements. Through constant questioning, reflection and engagement between the university and the community, students learn to identify multiple perspectives and pathways to social justice. In practice, in CRDS educational environments, much of the critical questioning and dissent has been carried out in seminars with faculty and peer support. The practice of disruption carried out at the site of CEL placements is often in collaboration with community and facilitates opportunities for ongoing change within and beyond the university. This collaborative work is carried out in parallel with the CRDS seminars and is relational in design. Trust is built with community partners through ongoing conversations, and planning occurs between the student and the community partner. CRDS faculty supervisors generally participate in these conversations once a semester during a supervisory visit to the community site.

Our first vignette presents an example from an important CEL setting for our students, a vocational service provider. We pivoted our CEL approach online in this context through a variety of strategies, including a movement to small group seminars and a focus on reflective writing, as well as increased opportunities for peer collaboration and online meeting opportunities. Vignette 1 provides further details.

Vignette 1: Vocational Rehabilitation

People who are injured/disabled at work are supported through insurance systems (i.e. Long Term Disability, Worker’s Compensation) to return to their pre-injury job or to new employment. Participation in vocational programs is often mandatory to receive ongoing benefits. Three students completed their senior level practicum concurrently with a vocational service provider during the COVID-19 pandemic. Each student completed a separate project with the organisation, working with employers, injured workers and potential employers to develop resources and assist injured workers in their return to employment. Services were offered online, in many instances for the first time, creating challenges for the service provider, service users, students and faculty.

| Pre-Pandemic Approaches | Post-Pandemic Pivot | |

|---|---|---|

| Ongoing Support | ||

| Instructors meet with individual students and supervisors | → | Practicum meetings were held with groups of students rather than individual students to encourage collaborative learning. |

| Monthly online student seminars led by practicum instructors on topics of advocacy, reflective practice and leadership | → | (Semester 1) Monthly online seminars were run as small group peer-run seminars on topics determined by students on critical engagement in practica. (Semester 2) Small group writing preparation for a reflective journal article was facilitated by an instructor. |

| Planning for Impact | ||

| Project often predetermined to reflect the need for flexibility in human services field and incorporate anti-ableist focus | → | Project planning with CRDS graduate site supervisor allowed groups to brainstorm projects to address critical questions around client-centred practice and mandated programs. |

| Clients attend programs at the community site office | → | Appointments occurred online, allowing students and clients to attend from home, making students question the accessibility and inclusivity of fully office-based services. |

| Participatory Curriculum Development | ||

| Project set-up and design frequently completed by phone; draft project proposals shared via email | → | Consultation and preparation of ideas were completed in a more visual, conversational format via Zoom, with options to share documents simultaneously. Students prepared documents in a more visual format, i.e. PowerPoint, to share their ideas. |

| Students complete individual coursework involving theory and practice | → | Students worked collaboratively on aspects of their assignments (i.e. peer review of a social justice paper), which assisted in critical analysis and the reflective paper required for the CEL practicum. |

| Reciprocal Relationships | ||

| Students sign up for areas/projects based often on interest and proximity, and accessibility of site to students’ homes | → | Students were able to access a larger number of sites to best suit their interests and abilities as they were not restricted by their geographical location. |

| Students bring experiential and cultural knowledge to share with site, but at first may feel intimidated to speak up in person | → | The ability to use chat functions on online learning platforms encouraged greater levels of engagement and sharing of knowledge, and also encouraged discussion of informal knowledge since the format seemed less intimidating to students. |

| Opportunities to Engage Critical Thinking and Reflection | ||

| Students develop client-centred interventions | → | New ways of engaging with clients outside of traditional office meetings created opportunities to consider barriers to participation for mandated programs (i.e. transportation and medical appointments). |

| Seminar facilitation with group on activism, reflective practice and leadership | → | Students provided critical thinking tools and cheat sheets to facilitate critical questions and examination in these seminars. Also provided opportunities to practise with peers. |

Tenet 2: Meaningful Mentorship

The second tenet of the ICM is based on the assertion that students engaged in critical work need to be supported by instructors and by one another. Critical elements of mentorship include reciprocity, learning relationships, partnerships, collaboration, mutually defined goals and development (Zachary 2012). Contemporary models of mentorship illustrate the shifting of traditional mentorship relations to include undergraduate students and highlight changing boundaries between students and faculty (Barrette-Ng et al. 2019). The assurance that student mentorship is equitable, diverse and inclusive is central to its impact (Rankin et al. 2022)institutions of higher education emphasize a tripartite mission of teaching, research, and service. Different institutions place varying weight on these mission areas, both in policy and in practice. Most institutions now also include a commitment to diversity as an institutional priority, although diversity statements are sometimes criticized as more performative than substantive (Hoffman & Mitchell, 2016. This highlights the importance of students having equitable access to mentorship from faculty and community. Students also work together as both mentors and mentees. They are often mentored by community-based CRDS alumni, who have gone on to take leadership positions in the disability sector after graduation. Mentors use transdisciplinary approaches, which reflect the realities of the social service and policy world into which these future changemakers will graduate. We also instill the need for support and mentorship that our students will need once in the field. The demands of their work as leaders in their communities may make the task of inciting change difficult and daunting but ensuring the habit of mentorship and support of one another through critical engagement may strengthen resolve and provide the essential social support and social capital needed to be empowered to enact change. We also mentor each other as faculty through the difficulties in navigating this critical space and delivering education both online and face-to-face. Our second vignette presents an example from an increasingly vital element of the social service landscape: programming and support for the ageing population. We pivoted our approach to CEL in this context through a variety of strategies, including increased and regularly scheduled meetings with instructors and supervisors, enhanced use of technology, reflective writing and critical thinking, and action around the value placed on the lives of older people during population health crises and beyond. Vignette 3 provides further details.

Vignette 2: Research and Program Development with Seniors

Seniors’ programs exist in residential, day program and community service formats across the city. Two prominent issues these programs attempt to address are isolation and caregiver burnout. In-person and residential programs offer opportunities for seniors to connect with staff and peers and engage in health and recreational activities, while providing respite for caregivers at home. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit seniors and long-term care facilities particularly hard, many of these programs were required to cease or limit operation to full-time residents and staff. Four students completed their senior practicums at three different programs for seniors, which included long-term care residents, and users of day programs and community supports under COVID-19 restrictions. Students’ projects included working with seniors, care givers and agency staff. Students in the three locations were supervised by program managers, including one site where two students were supervised by a CRDS graduate.

| Pre-Pandemic Approaches | Post-Pandemic Pivot | |

|---|---|---|

| Ongoing Support | ||

| Students complete individual projects with ongoing support from instructors and site supervisors. | → | Two sets of students completed their projects in pairs. They consulted with each other regularly and developed practices and resources together to foster peer support. |

| Students meet with site supervisors and practicum instructors as needed. | → | Students checked in more regularly via Zoom with the practicum instructor to discuss accommodation needs during the pandemic. Flexibility with projects and deadlines was required. |

| Planning for Impact | ||

| Projects reflect the need for flexibility in the human services field and incorporate anti-ableist focus. | → | Students planned time for technology to be set up and for individual users to be guided through the process. Client-driven programming was developed, including individualised and one-on-one supports for seniors and their caregivers. |

| Active collaboration with seniors was initiated to determine their wants, especially in terms of program planning. | → | A telephone-based survey was developed to engage seniors and also to understand their needs during the pandemic. |

| Reciprocal Relationships | ||

| Students developed projects to be used moving forward. | → | The programs developed will continue to be used for those who are unable/prefer to attend online. |

| Students brought experiential and cultural knowledge to share with the site. | → | Students gained unexpected knowledge around the technological abilities of seniors while sharing new platforms and ways to connect with them and their caregivers. |

| Opportunities to Engage Critical Thinking and Reflection | ||

| Students entered a program which described the needs of its users. | → | COVID-19 required us to question the needs of the different groups being served and to consider the ways that seniors are devalued in society, and how this is reflected in the types of programming available. |

| Services and programming were provided for seniors. | → | The projects required students to consider the available supports for caregivers when in-person programming was unavailable. |

| There were peer reviews of journal submissions, but no requirement to submit to the journal. | → | Student journal submissions reflected on the societal treatment of seniors in care as well as tools to diminish isolation in a system that promotes it. |

Tenet 3: Community Action

Our program is focused on social change in our critically engaged coursework and in our CEL placements. The coursework and placements create opportunities for action through scholarship and learning, generating new knowledge through the combining of academic and community-based expertise, which is reflected in the third tenet of the ICM, Community Action. This particular practice of community engagement is rooted in values of social justice and citizenship, and prompts academics and universities, in their roles of teaching, research and service to society, to work in ways that will build mutually beneficial and reciprocal bridges between university activity and civil society (Beaulieu Breton & Brousselle 2018). Although research on CEL suggests positive impacts for students and communities alike (Boyer 2016; Comeau et al. 2019), the approach is not without difficulties. CEL practice often struggles to match the needs of the community with the priorities of academia, with communication issues and power differentials often creating barriers to successful practice (Edwards & Milaney 2020; Gelmon, Jordan & Seifer 2013). The strategies we use to support CEL within our ICM framework purposefully seek to dismantle these differentials amongst community and academia and to provide genuine opportunities for students to engage in social change at the frontlines of services, systems and policy. Our third vignette presents an example from a setting that seems to be becoming more popular with our students every year: community-led research for social change. We pivoted our approach to CEL in this context by making space for increased community leadership (in this case disabled people and disabled people’s organisations), an increased recognition and use of students’ technical expertise, and a reliance on student-led initiatives. Vignette 5 provides further details.

Vignette 3: Community-Led Research

A community alliance made up of service agencies, self-advocates and stakeholder groups serving the disabled community was convened in May 2020 to respond to emerging issues of exclusion in the City of Calgary. A former CRDS student working with the alliance mentored three CRDS senior level practicum students working with self-advocates to develop an accessible survey asking disabled people and their families about their experiences with COVID-19 related restrictions and policy decisions. The development of the survey, the collection of the data and the analysis of the preliminary results made up the students’ CEL practicum project for the 2020–2021 academic year. A CRDS faculty member was the site supervisor, as is often the case in research-based practica.

| Pre-Pandemic Approaches | Post-Pandemic Pivot Successful Strategies | |

|---|---|---|

| Planning for Impact | ||

| Research was designed with students in collaboration with the community group to ensure the research was community led and community driven, with measurable outcomes. | → | Research questions were largely community driven, with some input from students. Most information was translated to students via the site supervisor as the time restraints of the community alliance members allowed little time for exploring questions in collaboration with students. |

| Outputs were co-created with students, with policy documents for wider distribution usually being produced by the site supervisor and/or community leaders. | → | Students were able to produce info-graphic outputs utilising their graphic design and experience in an online format that required little editing by project leaders. |

| Participatory Curriculum Development | ||

| Students explored research methodology and collaborative research approach in initial months of practicum guided by the site supervisor. | → | Students developed a plan to build research knowledge and background knowledge on COVID-19 and its impacts upon disabled people. Students found and participated in several online courses under their own initiative. |

| Although working in teams, much of the course work was individually based, including reflective writing and project planning documents. | → | Students worked collaboratively on aspects of their assignments, which assisted in critical analysis and a reflective paper required for the CEL practicum. Students also undertook project planning and evaluation as a team. |

| Reciprocal Relationships | ||

| Students built trusting relationships with community partners, working together to ensure equitable research practice. | → | Due to the restrictions on face-to-face meetings, these relationships did not have a chance to develop, especially with self-advocates, who often did not have access to the technology necessary for online meetings such as Zoom. The site supervisor often acted as a go-between. |

| Students brought experiential and cultural knowledge to share with each other and the site. | → | The ability to use chat functions on online learning platforms encouraged greater levels of engagement and sharing of knowledge amongst students. |

| Opportunities to Engage Critical Thinking and Reflection | ||

| Students critically examined research methodologies that regularly excluded disabled people. | → | Exclusion became very clear to students as they observed lack of inclusive policy, income disparity and a resistance to plain language translations, making critical examination meaningful and accessible. |

| Group online seminar facilitation to group on activism, reflective practice and leadership | → | Students provided critical thinking tools and cheat sheets to facilitate critical questions and examination in these seminars. They also provided opportunities to practise with peers. |

Discussion

Through our experience as instructors delivering CEL practica experiences in a fully online environment over a year, we discovered that we were able to use our ICM framework as a foundation for CEL in this new and changing environment. While recognising some of the difficulties faced by students, community sites, instructors and service users in a virtual world, we were also able to identify a number of successful strategies that we believe not only upheld the values and commitments of CEL practica experiences, but also revealed new ways to teach and learn in virtual settings that uphold more inclusive practices in building a more engaged community of learners. The vignettes presented exemplify some of the ways in which the ICM framework was successfully used. This allowed students to continue to, and in many ways, add additional options when engaging in meaningful CEL experiences.

The vignettes presented provide examples of online learning opportunities that we can learn from in future online iterations of CEL practica experiences, and in future in-person learning courses. We have identified key learnings from these examples that demonstrate the ways in which we believe the online environment has enhanced student learning and promoted the goals of the ICM during the year of fully online delivery.

Authentic collaboration

While online learning is often critiqued for lacking opportunities for engagement and collaboration, during their CEL practica students developed meaningful and authentic collaboration opportunities. Students were able to collaborate with more stakeholders in an online environment than they had been face-to-face and were able to engage in genuine change making. The students who worked with seniors, for example, were able to talk to them about their needs and desires, and their ability to engage with technology while facing isolation during COVID-19. The removal of geographic boundaries allowed for collaboration with a wider scope of stakeholders, including community leaders and service providers. The opportunity to collaborate with a greater number of people created opportunities to engage with those at the forefront of social change, as was the case with students involved in the community alliance to address exclusion in the city of Calgary. Working with this diversity of voices, students were able to identify issues around topics such as inclusive policy and income disparity. Rather than critically examining this exclusively in the classroom, students brought together theory and practice in this context to develop authentic collaborative work with the potential to impact social issues.

Students also worked more collaboratively with peers in the online environment during seminars. Where previously student work was mostly completed individually, the online practica offered more easily accessible options for collaboration. Using the chat function during seminars, for example, allowed opportunities for collaboration by those who did not feel comfortable speaking in class. Working in small groups, students engaged in a peer review process for a journal submission and together developed practical tools, such as critical thinking tools and cheat sheets, to facilitate questions in seminars.

The value of informal knowledge and skills developed outside of the classroom, such as online collaboration and social media expertise, was also emphasised when learning moved beyond the walls of the classroom/service provider site. Learners were increasingly able to build connections and use their prior experience to engage in change-making processes. Students with graphic design experience, for example, created infographics to demonstrate project findings and shared the findings widely in online formats. The use and sharing of these skills and experiences with the larger group show some of the ways in which an online environment can promote the value of prior learning and the possibility for increased collaboration.

Increased inclusivity

While there has long been debate in the disability studies field around the benefits and barriers created by technology and the digital divide around access, ability and use of technology (MacDonald & Clayton 2013), in this case the use of online learning opened opportunities for a more inclusive learning environment to many students. Students with employment commitments, for example, were able to access practica sites without commuting, geographical or transit barriers. The sprawl and limited transport available in Calgary, especially in the industrial areas where many disability services are housed, sometimes limit opportunities to access sites where CEL practica are offered. Engaging with sites online thus gave more opportunities for a ‘good fit’ between the site and the students. One student was able to complete her CEL practica from the Philippines.

Learning opportunities also became more readily available to students who often had limited availability. Many practica sites offered professional training as part of the CEL practica (i.e. first aid, data analysis, organisation specific training). As sites were forced to go online, professional training opportunities were offered asynchronously or online, making them more readily accessible to students. It should be noted that participatory opportunities were limited for some students because of time constraints and access.

The requirement to pivot to new ways of engaging learners in online formats also forced instructors to consider the traditional presentations of academic learning and the utility of presenting their work in more holistic and inclusive ways. Moving beyond traditional written essay formats for seminar assignments allowed a diversity of learners the opportunity to share their learning in a multitude of ways. Students co-presented their critical reflections regarding their sites as narrative reflections (i.e. podcasts) or through visual media (i.e. photovoice) and participated in an online ‘Community Connector’ event where students presented an overview of their projects to site supervisors and practicum instructors. The online learning space also facilitated students’ identification of gaps in inclusive practice and in systems and service provision. Students reported that being on site at disability organisations could, at times, be an intimidating setting from which to explore critiques of the systems and structures used by the organisations themselves. It seemed to be easier for students to share critiques and suggestions with community site supervisors in online formats rather than face-to-face. Students seemed to be able to brainstorm projects collectively and more confidently and disrupt and critique programs when the work took place online.

Greater engagement by a community of learners

The online CEL practica experience demonstrated ways that students were more engaged as a community of learners and more readily able to engage in the ICM principles. Recognising the centrality of instructor presence online (Baran & Jones 2020; Beltran et al. 2020; Brook & Oliver 2003; Northcote 2008; Passmore 2021) to engage learners and create a community, instructors provided online office hours, regular virtual site meetings and seminars to support learners. The implementation of online office hours greatly increased student use of this time, serving as an opportunity to answer questions, critically assess their placement and provide mentorship. We, as faculty members, were able to meet with students more often and found that students showed up to meetings more reliably when online. Before the move online, instructors had to physically travel to meet with placement supervisors and groups of students. Being able to do this online meant that there were more meetings, and we were able to respond more quickly to situations as they arose. The opportunity to collaboratively develop ideas and projects with other students changed the power dynamics, and we also noted as a faculty that students seemed to feel more confident in their building and questioning of ideas, systems and practices when online. Working collaboratively on projects within a single organisation also created more opportunities for peer engagement, which resulted in individualised and needs-based projects that created meaningful opportunities for students. A group of students, for example, worked on a plain language translation of COVID-19 documentation. This information was used to develop an online survey with over 200 participants and to communicate research findings to the community.

Finally, the practice of critical thinking and reflection with small groups online, using breakout rooms, provided the most obvious example of the development of a community of engaged learners, demonstrating the tenets of the ICM. We observed that students seemed to feel free to discuss and question ideas, to challenge assumptions and service provision, and sometimes stay beyond the duration of the seminar to continue their discussions. Student groups also frequently worked together in their own online meetings.

Conclusion

As we implemented the ICM framework during COVID-10 restrictions, it was sometimes difficult to see obvious connection points between the online CEL practica experience work and the three tenets of the framework. The five ICM strategies, however, provided a direct pathway between these interconnected practices and values. Using the identified tenets of the ICM framework as foundation for our CEL experiential practica and other course work in our program, we see the values and principles of disability studies reflected. The purposeful development and implementation of such a framework provides CEL practica instructors a means to evaluate and ensure that the strategies we use to support students are effective in facilitating the confidence and competence of students to engage in their CEL experiences. This is ever more important in a virtual environment where informal assessments of these skills are less easily carried out.

Working online through the CEL experiential practica provided significant challenges. However, the vignettes illustrate the ability, flexibility and engagement of the students and instructors in engaging in and inciting change in this essential work.

Although COVID-19 restrictions have ended, we have continued to use the learnings from our program in the following ways.

Authentic collaboration

• We have made space for hybrid practica placements where students can engage with clients and join community advocacy and service groups in an on-line format, allowing for more choice and active participation. This has increased the range of opportunities for students and has enhanced student engagement as they may not need to physically travel to other locations. We continue to notice students sharing ideas and opinions more often when they are able to use a video and/or a chat box to communicate.

• Modelled on the successful virtual break-out rooms we used during COVID restrictions, the in-person CEL seminars are now often divided into smaller peer-led discussion groups, with faculty present only when needed so that students can feel free to share ideas amongst one another, and can build relationships and increase peer support. We have noticed that student reflection papers and assignments seem to have improved a great deal with this increase in peer support and collaboration.

• We have continued to allow opportunities for students to use their expertise and knowledge of virtual environments by redesigning assessments to include online presentations and use of media, such as virtual photography, videos and art.

Increased inclusivity

• We now allow for virtual participation in practica for those who request it and often allow for hybrid designs. Meetings with faculty and community sites often take place online, making activities more accessible for students, and often for clients and the community as well.

• Online meetings are now common amongst faculty supervisors, students and community sites. We have continued to observe students participating in critical engagement and project planning more confidently when connecting with faculty and community supervisors in a virtual environment.

Greater engagement by a community of learners

• We, as faculty, have continued to offer virtual meeting hours and an increased frequency of meetings with students and the community. A virtual format allows us to be more responsive, especially when extra support is needed in a timely manner.

• We have continued to collaborate with students and the community online. Frequently, planning and sharing goals has become easier and the possibilities for larger group meetings are increasing.

• Our annual congress, when students report findings and experiences to the entire group of our community practica partners, has moved online. We have found that students feel more at ease presenting virtually. The timing of the event has become more effective, and the attendance of our community members has increased.

Drawing on our collective experiences over the duration of our online experiential practica, the lessons learned have resulted in what we believe is a stronger, more responsive and more varied CEL program. The resulting practices for supporting CRDS CEL students continue to employ the tenets of the ICM framework and support both virtual and in-person strategies. The ICM framework has provided the structure we needed to adapt, and it will continue to be used to take on new challenges as we work towards inciting positive social change.

Bibliography

Accessible Canada Act (2019 c-10). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/A-0.6/

Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, 42 U.S.C. § 12101 et seq. (1990). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/STATUTE-104/STATUTE-104-Pg327/context

Baran, E, Correia, A & Thompson, A 2013, ‘Tracing successful Online Teaching in Higher Education: Voices of exemplary online teachers’, Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, vol. 115, no. 3, pp. 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811311500309

Baran, M & Jones, J 2020, ‘Online teaching and learning in higher education settings: Focus on team effectiveness’, in C Stevenson & J Bauer, eds, Enriching collaboration and communication in Online Learning Communities, IGI Global, pp. 137–58. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-9814-5.ch008

Barrette-Ng, I, Nowell, L, Anderson, S, Arcellana-Panlilio, M, Brown, B, Chalhoub, S, Clancy, T, Desjardine, P, Dorland, A, Dyjur, P, Mueller, K, Reid, L, Squance, R, Towers, J & Wilcox, G 2019, The Mentorship Guide for Teaching and Learning, prism.ucalgary.ca. [online] https://prism.ucalgary.ca/items/ecee219d-928b-4525-890f-976a5828857c

Beaulieu, M, Breton, M & Brousselle, A 2018, ‘Conceptualizing 20 years of engaged scholarship: A scoping review’, Plos One, vol. 13, no. 2, p. e0193201. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193201

Beltran, V, Decker, J, Matzaganian, M, Walker, N & Elzarka, S 2020, ‘Strategies for meaningful collaboration in online environments’. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-9814-5.ch001

Boyer, E 2016, ‘The scholarship of engagement’, Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 15–28.

Brook, C & Oliver, R 2003, ‘Online learning communities: Investigating a design framework’, Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 19, no. 2. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1708

Cameron, C 2013, ‘Disability studies: A student’s guide’, Disability studies, pp. 1–184. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473957701

Comeau, D, Palacios, N, Talley, C, Walker, E, Escoffery, C, Thompson, W & Lang, D 2019, ‘Community-engaged learning in public health: An evaluation of utilization and value of student projects for community partners’, Pedagogy in Health Promotion, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2373379918772314

Edwards, M & Milaney, K 2020, Research 2: Social action for vulnerable families: Advancing social change with ‘true’ Community Engaged Research and Partnership [online]. https://obrieniph.ucalgary.ca/sites/default/files/teams/1/events/Seminar%20Series/2020-2021%20Seminars/05%2029%20Edwards%20and%20Milaney%20Poster.pdf

Gelmon, S, Jordan, C & Seifer, S 2013, ‘Community-Engaged Scholarship in the Academy: An action agenda, Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2013.806202

Goodley, D 2011, Disability studies: An interdisciplinary introduction, Sage Publishers, London.

Goodley, D 2013, ‘Dis/entangling critical disability studies’, Disability & Society, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 631–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.717884

Lum, B & Jacob, M 2012, ‘University-Community Engagement, Axes of difference & dismantling race, gender, and class oppression’, Race, Gender & Class, vol. 19 (3/4), pp. 309–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43497501

Macdonald, S & Clayton, J 2013, ‘Back to the future, disability and the digital divide’, Disability & Society, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 702–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.732538

Morton, M, Simpson, A, Smith, C, Westbere, A, Pogrebtsova, E & Ham, M 2019, ‘Graduate students, community partner and Faculty reflect on Critical Community Engaged Scholarship and Gender Based Violence’, Social Sciences, vol. 8, no. 2, p. 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8020071

Nishida, A 2018, ‘Critical disability praxis’, in Manifestos for the future of critical disability studies, pp. 239–47, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351053341-22

Northcote, M 2008, ‘Sense of place in online learning environments. Hello! Where are you in the landscape of educational technology’, Computer Science.

Oliver, M 2013, ‘The social model of disability: Thirty years on’, Disability & Society, vol. 28, no. 7, pp. 1024–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2013.818773

Passmore, D 2021, ‘Transforming from the classroom to an Online Nursing Educator: A transformative learning experience for new Online Nursing Faculty, in: N Tilakaratna, M Brook, L Monbec, S Lau, V Wu and Chan, eds, Research anthology on Nursing Education and overcoming challenges in the workplace, IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-9161-1.ch005

Rankin, J, Pearl, A, Jorre de St Jorre, T, McGrath, M, Dyer, S, Sheriff, S, Armitage, R, Ruediger, K, Jere, A, Zafar, S, Sedres, S & Chaudhary, D 2022, ‘Delving into Institutional Diversity Messaging: A cross-institutional analysis of student and faculty interpretations of undergraduate experiences of equity, diversity and Inclusion in University websites, Teaching and Learning Inquiry, vol. 10. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.10.10

United Nations 2006, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Treaty Series, 2515, 3.

Zachary, L & Fain, L 2022, Mentor’s Guide: Facilitating effective learning relationships, Jossey-Bass Inc, US.