Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 16, No. 2

December 2023

RESEARCH ARTICLE (PEER-REVIEWED)

Asset-Based Community Development in an Online Context: Crafting Collective Experience Into an Asset of Expertise

Samantha Close1, Chiarra Lohr2

1 Assistant Professor of Communication, DePaul University, Chicago, Illinois, USA

2 Executive Director, Indie Sellers Guild, USA

Corresponding author: Samantha Close, sclose@depaul.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v16i2.8684

Article History: Received 21/06/2023; Revised 03/08/2023; Accepted 31/10/2023; Published 12/2023

Abstract

This article analyses a case study for which an asset-based community development (ABCD) orientation was used to conduct community-based research (CBR). The community in question is, unusually, a digital community comprised of people who sell handmade crafts and vintage goods through digital marketplace platforms. This project, headed by a team of one academic and one community organiser, demonstrates a process by which CBR can be initiated by a community itself in order to effect change in the structural inequalities with which they are faced. To do so, we argue that community members’ expertise is a key asset, both individually and when collectivised through the research process. Involving community members in research on this basis helps change the way they look at themselves and their situation, and strengthens the bonds of this virtual community.

Keywords

Asset-Based Community Development; E-Commerce; Digital Communities; Community-Based Research; Crafts; Expertise

Introduction

This article details a case study in which the two authors, one an academic and the other a community organiser, used an asset-based community development (ABCD) approach to conduct research that was initiated by the community itself. This fundamentally alters the typical balance of power in the research process, conceptualising community members and academic researchers as experts working together rather than one as information source and the other as an expert extracting knowledge.

We first lay out the background of this particular case study, focusing on the power dynamics between communities, technologies and institutions. We continue by reviewing the relevant literature on online communities, ABCD, and their expertise in the context of independent craft entrepreneurship. We then explain the methodology of the study, with particular attention to how we incorporated ABCD principles and ideas of expertise in our study process, before turning to a discussion of what we gained by using this approach rather than a more traditional academic approach.

The Case Study

The Platform

Online marketplaces are ‘platforms’, or intermediary websites that ‘provide storage, navigation and delivery of the digital content of others’ (Gillespie 2010, p. 348). Customers search for items and make their purchases through the platform itself, rather than directly from each individual business which lists its wares on the platform. The platform takes a fee from sellers in exchange for this service and is also in charge of the technological infrastructure, policies, marketing and branding of the marketplace. Handmade marketplaces are those online platforms specifically used for the selling of handmade and vintage items. Each of these marketplaces has its own policies and enforcement rules for what types of items may be sold on its platform. Etsy, the largest handmade marketplace, allows handmade and vintage craft supplies, and items designed by a creative indie seller, but produced by another company, to be sold on their platform (Seller Policy 2022). Other marketplaces are more specific; for example, Ravelry is a marketplace for knitters, crocheters and other fibre artists.

There is a significant power imbalance between handmade marketplaces and the creative indie sellers who use the platform (Close 2018; Postigo 2014). The relationship between a seller and the marketplace is treated as a business-to-business relationship, with an underlying assumption of equal leverage. However, although creative indie sellers are technically small business owners, the majority of them are a business of one – themselves – who work out of their home (Etsy employees 2021). Platforms like Etsy are large, publicly traded global corporations with hundreds of employees, though often headquartered in the USA. Much like a boss sets work hours, conditions and terms, platform companies use tools like policy and the website’s algorithms to strongly encourage those who sell through their websites to behave in particular ways (Rosenblat & Stark 2016).

There is often an assumption that platform users, such as creative indie sellers, who are unhappy with one platform can simply leave the site and join another. The reality is very different (Cassidy 2022). Large online marketplaces like Etsy, eBay and Amazon Handmade attract the vast majority of customers for handmade, vintage and craft supply products. As one business news outlet put it, ‘for many sellers, there are few alternatives’ because of Etsy’s domination of the search results for handmade goods, the higher transaction fees charged by alternative services and the technical know-how required to set them up (Kaziukėnas 2022). An individual seller has no real power to change or challenge the policies set by these large marketplaces and often cannot afford to leave. In this way, individual indie sellers can end up trapped on platforms that provide the majority of their customers, but whose policies and fees make it more and more difficult to run a sustainable business.

In the world of handmade crafts, vintage goods and craft supplies, Etsy originally played a large part in creating the indie seller community following its founding in 2005. It offered workshops on different topics to help sellers grow their businesses and created ‘street teams’ that helped sellers negotiate better rates for vending at in-person art fairs (Lee McCarty 2021). Etsy became a certified B- Corporation, a business which meets certain requirements in terms of its profit distribution, community relationships and environmental impact in 2012. B-corporations that go public are ‘legally required to consider the interest of all stakeholders in making corporate decisions and allocating resources, not just the interests of shareholders in maximizing profit and financial return’ (Chou 2018). But after their Initial Public Offering (IPO), Etsy dropped its B-Corporation certification (Silverman 2017). The drive to return a greater and greater profit to its venture capital investors led to several leadership changes at Etsy as well as the discontinuation of these seller support programs (Lee McCarty 2021).

The Community

As Luckman (2013) argues, times of rapid technological advancement and integration into society commonly see countercultural movements that embrace traditional ways of making items, such as handcraft. This was absolutely the case for the recent so-called digital revolution and rise of the Internet. Knitting, for example, was embraced by young women in ‘stitch ‘n bitch’ groups, which saw the percentage of American women under 45 who could knit or crochet double from 1996 to 2003 and then continue to expand (Stoller 2003). Despite their emphasis on handmaking, these crafters were highly connected through the internet (Levine & Heimerl 2008).

Within this large and diffuse subcultural movement exist many smaller self-aware communities. One such example is the Indie Sellers Guild (ISG), a grassroots non-profit organisation that ‘fight[s] for a better, fairer internet—where makers, artists, designers and other creative indie sellers can run sustainable online businesses’ (Indie Sellers Guild 2023). Its members are indie sellers themselves as well as ‘allies’, such as the customers who shop at independent businesses. This type of small business is very community driven. Handmade and vintage sellers usually start off as handmade and vintage hobbyists who are encouraged to start businesses by their crafty friends (Close 2014; Kim 2019). Customers shop with these kinds of businesses because they want to know who they are buying from and how their items were made or found (Dudley 2014; Matchar 2013). ISG has organised itself according to the methods that its members are used to; for example, creating a Discord server and Facebook community so that its globally dispersed membership can come together and discuss online, as well as hold monthly online meetings using tools like Zoom.

What differentiates the ISG as a community is that it is an organisation focused on labour rights that was self-organised by handmade crafters and vintage sellers. In April 2022, nearly 30,000 Etsy sellers went on a week-long ‘strike’ to protest policy changes to the platform. The strike mobilised from among the more than 80,000 signers of Kristi Cassidy’s petition on Change.org that initially demanded Etsy roll back a 30 percent increase in the fees they charged to sellers. It grew, however, to encompass five key demands: cancel the fee increase, crack down on dishonest ‘resellers’ who pass off mass-produced items as handmade crafts, provide better customer support to sellers, end the ‘Star Seller’ program which many perceived as pushing them to work faster and longer, and allow sellers to opt out of offsite ads, for which Etsy charged an extra fee to provide to the sellers. The strike made news headlines around the world and eventually did win some concessions from Etsy management (Indie Sellers Guild 2022).

However, by the end of the strike it had become clear that, in order to achieve lasting change for workers, it would take more than a single week of grassroots action. Unlike most formal employer–employee relationships, people who work through platforms are not covered by labour regulations that ensure fairness on the job (Gray & Suri 2019; Rosenblat & Stark 2016). To that end, the Etsy Strike 2022 organisers came together to build a lasting democratic organisation of independent online sellers, the ISG, to advocate for their interests collectively. Lohr was elected as the Executive Director of the ISG.

Though there is no exact count of creative independent sellers globally, Etsy alone has 6.3 million sellers, of whom roughly 3.3 million are in the United States (Etsy Employees 2021). According to the demographic research done for this study, ISG members roughly mirror the larger population of Etsy sellers in that they come from around the world, but tend to concentrate in the US, the UK and Canada, range significantly in age, and the majority are female. Similar proportions identify as male and as non-binary/third gender and are in the majority white. The largest difference between Etsy’s census data and our participants is that 37 percent of our participants identified as LGBTQIA+, while only 14 percent identified as such in Etsy’s census. Etsy did not collect data on disability or caregiving responsibilities; however, many of our participants had these identities. Fourteen percent identified as physically disabled, while 27 percent identified as mentally disabled or neurodivergent. Twenty-four percent had primary caregiving responsibilities, such as childcare, eldercare, or disability care.

What these demographics tell us is that indie sellers are non-traditional business owners and entrepreneurs in terms of their gender – in the United States, only 40 percent of entrepreneurs and 43.2 percent of small business owners are female (‘Entrepreneur Statistics’ 2022; Main 2022). Most studies of entrepreneurs do not collect data on sexuality, disability, or caregiving responsibilities.

This indicates that indie sellers overrepresent those who have been pushed out of the traditional workforce: people with disabilities or chronic health issues, caregivers, and trans and non-binary individuals. A creative small business provides them with a way to make supplemental income or even a living from home, and the ability to work to their own schedule and around their other needs using skills they already possess. Such people are even more dependent on platforms because they cannot easily re-enter the traditional workplace. They also suffer more from platform policy and algorithm changes that micro-manage how they work. For instance, the Star Seller program requires that sellers respond to every message sent through the platform within 24 hours and gives preferential placement in search results to Star Sellers. But how could someone with a chronic health condition who started an Etsy shop be available every single day?

Literature Review

Online Communities

‘Community’ is a powerful and oft-invoked concept, as demonstrated by the names ‘community-based research’ and ‘asset-based community development’. But as with many such concepts, the precise definition of community is contested and difficult to pin down (Bradshaw 2008).

In the context of ABCD, communities are often assumed to consist of people in close physical proximity to each other. For instance, Kretzmann and McKnight (1993) often refer to communities as ‘neighborhoods’, and this focus on physical place has persisted in the field. Even place-based communities, however, have a sense of virtuality to them. Early theorists of community, such as Weber (2013) and Tönnies (2001), suggested that one type of community was the ‘community of the mind’, in which the felt sense of belonging was as or more important than physical closeness. Benedict Anderson (2006, p. 6) influentially theorised that nations, as imagined communities, ‘imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion’. Urbanisation is often argued to have undermined community (Putnam 2001). Yet some see it more as a process of people shifting from belonging in place-based communities to belonging in community with those of similar profession, religion, sexuality, or even interests (Bradshaw 2008).

Howard Rheingold (1993) was one of the first to apply the idea of community to the then-new phenomenon of the internet, optimistically praising the potential for new forms of community-building online. Subsequent literature often referred to ‘online participation’ (Carpentier & Dahlgren 2011) or ‘participatory culture’ (Jenkins 2008) rather than community-building, per se, while still discussing many of the features associated with communities. Participatory culture communities have a few key specific features: a creative dimension, in which members create and share artistic works with each other, a social dimension, in which members see themselves as part of a community group, and a motivational dimension, in which participation is associated with a social purpose (Lutz et al. 2014).

This literature has been critiqued as overly optimistic, with some questioning whether online participation meets the standards for community-building set by face-to-face organisation (Hay & Couldry 2011; Turkle 2011). Some of this scepticism might be prompted by the evolution of Web 1.0, characterised by email lists and discussion boards, into the social media of Web 2.0, characterised by platforms that allowed users to create profiles and engage with each other, and corporate encroachment on the concept of community (Jenkins et al. 2013). Similarly, some scholars critique the technological determinism of ideas like a ‘Facebook Revolution’ spawned by the Arab Spring uprisings, in which activists and everyday citizens utilised social media tools to organise and protest (Allagui & Kuebler 2011; Morozov 2014).

That being said, online communities are particularly important for people who work via online platforms. Gray and Suri (2019) found that crowd workers, or people who do the small tasks that fuel AI, collaborate with each other via online social networks in order to manage administrative overhead, find better work, and receive the social support traditionally associated with in-person workplaces. Maffie (2020) found that ride-hail drivers, who work via platforms like Uber or Lyft, were significantly more interested in joining a labour organisation when they interacted more frequently with other drivers via social media. Joyce, Stuart and Forde (2023) argue that unions and union-like organisations are more successful with workers in the platform economy when they build on the existing, often online, social networks workers have formed with each other rather than depending on the workplace-specific organising tactics used against auto manufacturers, for example.

Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD)

ABCD is, at its heart, an approach that seeks to build on a community’s strengths – its assets – rather than looking to address its needs (Kretzmann & McKnight 1993). In this, ABCD shares some core ideas with Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach to development, which emphasises people’s ‘actual ability to achieve various valuable functionings as a part of living’ rather than quantitative and material measurements such as wealth or personal utility (Sen 1993, p. 30). ABCD assets include six different types: individuals, associations, institutions, land and the physical environment, exchange, and culture and stories (García 2020). ABCD often takes physical neighbourhoods as the theoretical environment in which research or development will take place. As such, the asset of individuals would be people living in the neighbourhood. The asset of associations would be the kind of informal gatherings that often make up the social life of a neighbourhood, such as a knitting circle or a regular pick-up after a basketball game. Institutions are associations that have been formally concretised – for instance, a non-profit operating in a neighbourhood, a local business association, or a church. Land and the physical environment are assets: buildings, which might be used for meetings; empty lots, which might be turned into gardens; or restaurant kitchens, which might be able to host events or supply a community food bank. The asset of exchange relates to local economies: how money and goods flow through a community. This often refers to the kinds of businesses operating in a neighbourhood, for example, small, locally owned shops that keep money within the community rather than extracting it, as large corporations do. But it can also refer to money-less exchanges, such as a clothing exchange or ‘buy nothing’ groups. The asset of culture and stories is the knowledge that lives within the community, such as stories about what happened the last time researchers came to the community, or histories of the neighbourhood.

As these examples demonstrate, assets are mergers of tangible and intangible things. For instance, an individual can have ‘gifts of the head (subjects residents know)’, ‘gifts of the hands (practical skills that residents know)’ and ‘gifts of the heart (issues residents care deeply about)’ (García 2020, p. 70). ABCD often begins from a practice of asset-mapping, whereby researchers help community members recognise all of the assets they already possess (Haines 2014). One impetus behind ABCD is a desire to avoid continually associating already marginalised communities with deficits or needs, as this approach can make the communities themselves seem like ‘the problem’. It can also ‘lea[d] concerned outsiders into becoming charitable “fixers”’ rather than concentrating power within the community (Bergdall 2013, p. 1).

One key difference between needs-based development and ABCD is that for needs-based development, financial resources are the most important resource, whereas for ABCD, people and relationships are the most important resource (García 2020). Once assets are mapped, ABCD works to connect them together, when these connections do not already exist. This multiplies the power of each individual asset (Kretzmann & McKnight 1993). Asset connection is a particularly powerful part of ABCD in the context of CBR, where partnerships between academic institutions and communities are common. These partnerships are usually begun with great hope, but often run into many problems, such as ‘terminological and conceptual differences, multiple perspectives and ways of knowing, inconsistency about what constitutes success, and measurement messiness’ (Plummer et al. 2022). The ABCD approach helps to cut through this potential morass by providing a clear framework for identifying the unique strengths of all involved, both researchers and community members.

ABCD is more often associated with local development projects than it is with research projects, per se (García 2020; Kretzmann & McKnight 1993; Mathie & Cunningham 2003, 2005). However, many of its core values and ideas are reflected in CBR. For instance, Mathie and Cunningham (2003, p. 474) write that ‘the appeal of ABCD lies in its premise that people in communities can organise to drive the development process themselves by identifying and mobilising existing (but often unrecognized) assets, thereby responding to and creating local economic opportunity’. This clearly resonates with CBR, as such research is ‘genuinely collaborative and driven by community rather than campus interests; that democratizes the creation and dissemination of knowledge; and that seeks to achieve positive social change’. (Strand et al. 2003, p. 5). The obvious points of overlap are self-determination by community members and a clear end goal of social change. We see expertise as another crucial point of overlap. Expertise is an asset when considered under the ABCD framework, and recognising the expertise of community members is crucial in order to ‘facilitate collaborative, equitable partnerships in all phases of the research’, a key principle under the CBR framework (Roche 2008, p. 3).

ABCD is not without its critics. The idea of focusing on marginalised communities’ strengths sounds, to some, much like the neoliberal ideal of pulling yourself up by your bootstraps (MacLeod & Emejulu 2014). Friedli (2013, p. 140) similarly argues that ABCD’s ‘fatal weakness has been the failure to question the balance of power between public services, communities and corporate interests’. It is true that much of ABCD’s foundations come from situations in urban America where the possibilities for outside assistance, from the state or other sources, were considered ‘bleak indeed’ (Kretzmann & McKnight 1993, p. 5). This state of affairs has unfortunately expanded since Kretzmann and McKnight did their work.

We argue that ABCD is still a highly productive approach despite these critiques. Pairing ABCD with a research-based political economic analysis, as in CBR, can address some of the blind spots identified by critics. Further, as we will demonstrate in this case study, taking an ABCD approach does not have to mean letting the state off the hook for its responsibility to support its citizens. Community assets, such as culture and stories, can be mobilised by community members to influence legislators and affect public policy, which can change the power relations in which the community is embedded.

Expertise

Expertise presents a conundrum for technologically advanced democracies. It is, on the one hand, necessary to build, maintain and advance technology. On the other hand, it necessarily introduces differences between people in an anti-democratic fashion, separating the population into expertise haves and have-nots (Faulkner et al. 1998; Schrock & Close 2017). Activists have targeted the idea of expertise as a vector for social change. Some community organisations, such as Black Girls Code, seek to disperse expertise, for instance, teaching technology skills to those under-represented in technological fields. Others, like low-fi radio activists Prometheus, attempted ‘to break the conventions of expertise as it is traditionally constructed in order to promote an egalitarian ideal’ (Dunbar-Hester 2014, p. 186).

Expertise is often conceptualised in relation to professional work – as a special kind of knowledge, in that expertise carries with it social esteem and often a paid position (Brown 2014). Particularly in the contemporary digital moment, science and engineering or ‘STEM’ fields form a bastion of expertise that is socially validated (Faulkner et al. 1998). That being said, there is a literature that explicitly considers expertise in relation to craft. Sennett (2008) takes an individualistic perspective which valorises the expertise of the master craftsman and his satisfaction in a simple job done well, which McRobbie (2016) has critiqued on gendered grounds. Patel (2020) has most comprehensively developed a theory of the contemporary cultural worker’s unique expertise. Her model of ‘aesthetic expertise’ incorporates competence within the skills of creative production – rather than the aesthetic judgement of the art critic – as well as the capacity to signal those skills, particularly in an online context, and the ability to balance their primary creative activity with the entrepreneurial activity necessary to earn a living.

But is expertise solely an individual property? Digital media studies have suggested a different approach, which takes a large crowd, rather than a credentialled professional, as the potential source of expertise. There are two major theories: the wisdom of the crowd paradigm and the collective intelligence paradigm.

The wisdom of the crowd argues that ‘even if most of the people within a group are not especially well informed or rational, it can still reach a collectively wise decision’ (Surowiecki 2005, p. xiii). As an example, proponents of the wisdom of the crowd often use the curious phenomenon that when a crowd of people all guess the answer to a question, such as how many gumballs are in a jar, the average of their guesses is likely to be correct. In other words, the wisdom of the crowd is all about aggregation, particularly the aggregation of strangers. It underlies processes, such as ‘crowd work’ platforms, where a single job is broken up into micro-level ‘tasks’ and each one given to a different person from a very large pool. Rather than any particular individual inside the crowd, no matter their gifts, the crowd itself is the ‘expert’. This view has become particularly common among owners of digital platforms.

The collective intelligence paradigm, by contrast, depends on socialising and connecting within the crowd (Lévy 1997). As Jenkins (2008, p. 4) put it, ‘None of us can know everything; each of us knows something; and we can put the pieces together if we pool our resources and combine our skills.’ A good example of collective intelligence is actually the ABCD ideal: a community whose assets are known and connected with each other. For instance, a church (institution) might work with a local women’s group (organisation) to put on a thrift sale (exchange) to help raise money to create a new community garden in an empty plot (land). No one member of the church or customer at the thrift sale could have accomplished all of this on their own. Neither could the aggregate crowd of people involved without the social network that tied them all together. In a very powerful sense, everyone involved is simultaneously an expert in something and a layperson in something else. This idea of expertise diminishes its anti-democratic properties and suggests that expertise lies in networks rather than crowds of strangers.

Methodology

Cunningham and Mathie (2003, p. 476) explain ABCD as ‘an approach, as a set of methods for community mobilization, and as a strategy for community-based development’. Here we envision CBR as a tool that can be deployed within the ABCD approach that the ISG is taking. Flyvbjerg (2012, p. 33) argues that the basic questions of values rationale, or phronetic social science research, with reference to a specific community, are ‘Where are we going? Is this development desirable? What, if anything, should we do about it? Who gains and who loses, and by which mechanisms of power?’ In this case study, the ISG and its members had already answered the first two questions: We are going in a direction where a small number of online platforms will have total power over the working environments of independent online sellers, and this is extremely undesirable. Alternative marketplace platforms exist, but they tend to be smaller and – as evidenced in discussions among ISG members and the larger online crafting subculture – varied dramatically in quality. The ISG answered Flyvbjerg’s third question (what should we do about it), by suggesting the idea of a marketplace accreditation project, as a community labour organisation, whereby the ISG could vet marketplace platforms on how well they treated the sellers who worked on them and whether they provided what different groups of sellers needed.

There was one problem: the ISG was not sure what constituted a ‘good’ marketplace platform for sellers. Individual ISG members had personal opinions on the topic, such that an ‘Etsy Alternatives’ discussion channel was created early on in the organisation’s discussion server. But members freely admitted that their opinions depended heavily on their own situations – their particular craft, their geographical location, their level of coding knowledge, whether they were full-time or part-time sellers, and so forth. Close conducted a review of the literature on marketplace platforms and discovered that there were two major approaches. First, an abundance of business literature on online marketplace platforms existed, but it was almost exclusively from the point-of-view of the companies owning the platforms – not that of the people working on them (Evans & Schmalensee 2016; Sanchez-Cartas and León 2021). Second, media and communications scholars had developed a burgeoning literature on ‘platform studies’, but it tended to be more critical and theoretical rather than concerned with the practical and day-to-day policies and features by which marketplaces could be judged (Duffy 2017; Gillespie 2010; Nieborg & Poell 2018). Thus, new research was needed to determine what standards the ISG should use for its marketplace accreditation program.

We designed a methodology based on ABCD principles and included the concept of expertise as a community asset. We posited that the knowledge of what an ideal marketplace platform should look like – an ‘asset of the mind’ – was already distributed among the many members of the ISG and the wider handmade and vintage communities. What the ISG then needed was a way to concretise that knowledge into expertise, which could form the basis of the accreditation program.

Close suggested that she serve as an outsider catalyst whose research skills could help to draw out the collective intelligence of the community as an asset of shared expertise. Outsider catalysts are people from outside a community who ‘hold up a mirror so residents can see themselves as they really are ... [using] analytic tools and exercises that help community residents to identify and recognise strengths and capacities which they may have overlooked or ignored in the past’ (Bergdall 2013, p. 4). As the term implies, catalysts should stimulate or encourage community members to develop projects, rather than taking on leadership roles. We accomplished this by considering Close’s academic expertise to be primarily useful in creating spaces for community members to recognise their own expertise.

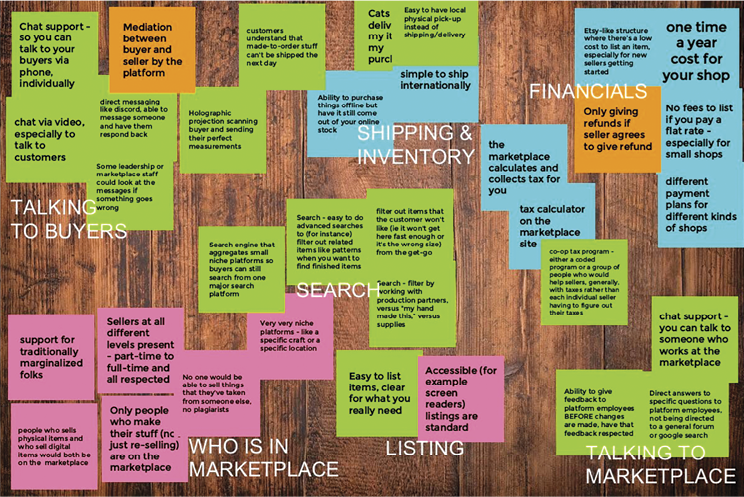

The research was a multi-stage process. First, Close hosted an online workshop for ISG members. Lohr posted an open invitation to the event in the community’s Discord server and Facebook group. Seven members attended and participated in the workshop. In a traditional ABCD study, this would be a session dedicated to asset-mapping. However, these techniques are designed for place-based communities, such as neighbourhoods, and do not translate easily to a geographically dispersed community like that of indie sellers. We focused on the assets of exchange and culture and stories. Close asked attendees to imagine what online marketplaces might look like for indie sellers in the year 2100 if they developed in the best possible way (see results in Figure 1). This naturally transitioned into community members sharing stories about their experiences when things went well, along with challenges they encountered. Close documented the discussion by writing virtual post-it notes as people talked, then asking the community members to organise the post-it notes into common themes.

Figure 1. Exchange and culture and stories asset-mapping workshop result

Close and Lohr then wrote an open-ended survey that covered the topics around which workshop attendees’ ideas had coalesced. We also added questions similar to those asked in the workshop, such as ‘If your ideal ONLINE marketplace was a PHYSICAL space, what would it look like?

We then shared this draft of the survey with community members for their feedback. As discussed earlier, many crafters are disabled, and their ideas significantly impacted the framing of our demographic questions around disability. They rejected ‘person-first’ language common in academia, such as “I am someone with a physical disability,” in favour of language which recognised disability as an identity, such as “I am disabled.” After revisions, we offered the survey to both sellers and customers of handmade, vintage and craft goods online, using the ISG’s social media to spread the word throughout the community. There were 215 responses, drawn primarily from the ISG membership, roughly a 10 percent response rate.

We then took the qualitative data from the open-ended survey and applied a similar process to that following the workshop: identifying common themes as well as areas of agreement and disagreement. Close read the answers to the questions addressed to sellers and Lohr read the answers to the questions addressed to buyers. Each author prepared a summary of the responses to each question. After comparing our summaries, we wrote a multiple-choice survey covering the same topics as in the qualitative survey, but with more specific questions. For example, two questions drawn from the responses to the question about communication between self and the marketplace platform were: In MOST CASES, the best method of communication between the marketplace site and me is ... (followed by communication channels such as phone call, email, etc.). When PROBLEMS OCCUR, the best method of communication between the marketplace site and me is ... (as above). These questions derived from our discovery in the open-ended survey that sellers felt these two communication contexts were different and likely required different communication channels. In this section, we also asked ‘When I’m communicating with the marketplace, it’s MOST important that ... (communication is fast and easy to access/I feel heard and the communication is respectful/the issue is resolved).’ This arose from reading that these three values of speed, respect and resolution were important, but it was difficult to tell which was of primary importance due to the open-ended nature of the survey.

The multiple-choice survey was then distributed among ISG’s membership and throughout the broader community of creative independent sellers via social media posts and keyword-based advertisements. At the time of writing, over 1200 people had responded.

The ISG will take the results of the multiple-choice survey and use them to develop its Marketplace Accreditation program. It will use the survey results as a concrete explanation of community members’ needs and desires for marketplaces and also use them to create a standard by which to judge marketplace platforms, both large ones such as Etsy or eBay, and smaller, newer platforms attempting to enter the space or to specialise in one craft area. This program will help the community break Etsy’s monopoly over handmade crafts and vintage goods by making it easier to tell which platforms are worth sellers’ time and effort to use. Over time, sellers will migrate away from platforms which exploit them and towards platforms that work with them fairly.

Discussion

Indie sellers are often told, particularly by platforms, that any problems they encounter are a result of deficits in their craft and business skills. A proposed solution is for them to individually seek help from outside experts, for example, taking a business course. However, we argue that this is wrong on multiple levels. Our research demonstrates that, while any one individual seller may be able to improve on a skill, creative independent sellers collectively possess clear expertise. They are ‘content experts’, possessing gifts both of the hands and the heart (Attygalle 2017; García 2020). The community’s gifts of the hand lie in their aesthetic expertise: they know how to craft or locate an item, how to photograph that item, how to list that item, how to pack and ship an order, and how to engage with customers about their purchases. Their gifts of the heart consist in their collective vision for sustainable businesses that value their own voices and ‘the handmade’.

We align with Roy (2017) in that ABCD is a way to enhance the collective and build solidarity, values opposed to neoliberalism’s individualism and privatism. Taking part in this CBR project helps crafters and vintage sellers to reconceptualise themselves as experts in conducting independent creative businesses online. It is their ideas that determine which aspects of marketplaces are important, as well as what kinds of policies and features will best support them. Further, it became clear to indie sellers that the problems they encounter are shared. This supports an understanding of their relationship with marketplace platforms as one beset by structural inequality, not one in which all their problems would disappear if they simply worked harder or smarter.

The value that the community puts on the idea of the handmade emerged from the research process. We go into some detail here about this to demonstrate the kind of findings that CBR can produce when using an ABCD orientation.

Most participants in the qualitative survey emphasised the importance of a marketplace having only ‘truly handmade’, ‘actually handmade’ and ‘genuinely handmade’ items available for sale. Clearly this concept was of great importance to the community, perhaps even serving as the basis on which members built their own aesthetic expertise. And yet, it was also clear that indie sellers disagreed about the precise definition of handmade. One seller responded, ‘High end, completely hand made only. people designing and making their own items from scratch, without production partners.’ Another answered, ‘Handcrafted items, items that are printed or manufactured with the help of a second party, or raw materials/tools for crafts.’ These definitions directly contradict each other.

This finding was not one anticipated by the workshop, nor would it have likely emerged from a study looking at the existing literature on e-commerce marketplaces, which tend to gloss over handmade marketplaces. It only emerged through considering indie sellers to be experts on handmade marketplaces and asking them what kinds of items should be sold on such platforms. This dissensus on the definition of handmade poses a serious challenge for ISG’s Marketplace Accreditation Program, as it must be sensitive to the competing definitions of ‘handmade’ present in the community.

After receiving this feedback, we added an entirely new section to the multiple-choice survey to help tease out the different definitions of handmade. Understanding the subtlety of how the creative indie seller community defines handmade will not only make the eventual marketplace accreditation program more likely to be successful, but will be critical to defining the boundaries of the community itself. If the community of creative indie sellers involves ‘small businesses run by artists, makers and curators selling handmade, unique, vintage and craft supplies’, as defined earlier, then how members of the community define handmade is critical to its self-understanding.

This touches on one key way this case study is different from other ABCD work. The creative indie seller community is not defined by location, socio-economic status, racial or ethnic identity, or employer. It is a community defined by the kind of work that members do, in a profession that does not have clear outside definitions or credentials. This kind of community is increasingly more common in our digital and globalising world and should be considered as a site for community development, particularly when it is a site of community economics.

What this research process also demonstrates is the value of conceptualising expertise according to the theory of collective intelligence. This theory highlights the importance of social connections between community members, which here has culminated in the Indie Sellers Guild. The ISG can now build on the combined expertise of its members to create the Marketplace Accreditation Program, which will begin to challenge the structural inequalities facing creative independent sellers. No one person’s expertise could do this alone.

Conclusion

J.K. Gibson-Graham (2006, p. xxx) writes that she is often approached with the question ‘Why do these things always fail?’ in response to her work on post-capitalist and community economic projects. A similar gloom hangs around press coverage of the ISG, for example, in the Washington Post: ‘I admire their effort, though I suspect it’s in vain. Just as the Arts and Crafts movement couldn’t last, a large-scale online marketplace of handmade goods in the age of Amazon Prime seems increasingly like a hopeless endeavor’ (Wagner 2023). This is an ironic statement at a time when Etsy facilitated the sale of 12.2 billion dollars of goods in 2021 alone – –hardly a marketplace on the verge of collapse (Etsy employees 2021). Gibson-Graham (2006, pp. xxx–xxxi) asks whether this mindset has ‘a theoretical investment in failure ... [where] anything in relation to capitalism is understood to be dominated, if not actually controlled by it’. Using an ABCD approach that helps creative indie sellers see themselves as capable agents of change, with expertise and a community behind them, directly counters this cynicism. Co-researching questions that matter to the community shows people how their expertise can be the basis for a new and better version of e-commerce, one focused on sustainability and support rather than exploitation and extraction.

CBR like this, carried out in the context of ABCD, can also help communities influence state policymaking. In July of 2023, US Senator Baldwin (WI-D) reached out to the ISG to ask their opinion on new legislation that would require anyone selling a new, foreign-made item online to disclose their item’s country of origin. This touches directly on the issue of ‘what is handmade?’ that arose in our study, as resellers often buy items made outside the United States before passing them off as handmade within the United States on platforms like Etsy. There was a strong consensus from the community’s responses to our survey that such practices should not be allowed.

Following this research, the ISG was able to confidently issue a statement of support for the proposed legislation and also provide data to back up its claim that the legislation would be strongly supported by creative indie sellers. The hitherto lack of existing research on what this community needed in a marketplace, as well as its dispersed, ‘crowd-like’ nature, meant that the marketplace platform owners had previously spoken for the community to legislators. They had successfully lobbied against previous versions of the bill, claiming that it would be a hardship for indie sellers, in direct contradiction to our research findings. This time, the bill progressed out of committee’s hands and will be considered by the full US House of Representatives.

This case study demonstrates the utility of ABCD and hopefully answers the concerns of some critics, particularly around its attention to structural power. It brings ABCD into the context of digital communities organised on the basis of shared work and interests, rather than place-based communities. It conceptualises community members as possessing an asset of expertise based on the knowledge they develop working day-in, day-out at selling their own handmade crafts or vintage goods. Finally, it highlights how a community association like ISG can harness the community’s assets of expertise into a collective program that will help rebalance the scales of power in the digital platform economy.

References

Entrepreneur Statistics, 2022, Think Impact. https://www.thinkimpact.com/entrepreneur-statistics/ (accessed 8.1.2023)

Allagui, I & Kuebler, J 2011, The Arab Spring and the role of ICTs, Introduction, International Journal of Communication, vol. 5, no. 8.

Anderson, B, 2006, Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism, rev. edn., Verso, London and New York.

Attygalle, L 2017, ‘The context experts’, Tamarack Institute. https://www.tamarackcommunity.ca/library/the-context-experts

Bergdall, T 2013, ‘The catalytic role of an outsider: Facilitating Asset Based Community Development’, in Timsina, T & Neupane, D (eds), Changing lives changing societies: ICA’s experience in Nepal and in the world, ICA International, Kathmandu, Nepal, pp. 1–13.

Bradshaw, T 2008, ‘The Post-Place Community: Contributions to the debate about the definition of community’, Community Development, vol. 39, pp. 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330809489738

Carpentier, N & Dahlgren, P 2011, Introduction: Interrogating audiences: Theoretical horizons of participation, Communication Management Quarterly, vol. 6, pp. 7–12.

Cassidy, K 2022, ‘Please don’t lie to yourself!’, Indie Sellers Guild. https://indiesellersguild.org/please-dont-lie-to-yourself/

Chou, E 2018, The Public Capital Markets and Etsy and Warby Parker [WWW Document], Social Enterprise Institute, Northeastern. https://www.northeastern.edu/sei/2018/10/the-public- capital-markets-and-etsy-and-warby-parker/

Close, S 2018, ‘The Political Economy of digital platforms’, Flow Journal, p. 25.

Close, S 2014, ‘Crafting an ideal working world in the Contemporary United States’, Anthropology Now, vol. 6, pp. 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/19492901.2014.11728453

Dudley, K 2014, ‘Guitar makers: The endurance of artisanal values in North America’, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226095417.001.0001

Duffy, B 2017, (Not) getting paid to do what you love: Gender, social media, and aspirational work, Yale University Press, New Haven, London. https://doi.org/10.12987/yale/9780300218176.001.0001

Dunbar-Hester, C 2014, ‘Low power to the people: Pirates, protest, and politics in FM radio activism’, Inside technology, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262028127.001.0001

Etsy employees 2021, 2021 Global Seller Census Report, Etsy Corporation, New York.

Evans, D & Schmalensee, R 2016, Matchmakers: The new economics of multisided platforms, Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, Massachusetts.

Faulkner, W, Fleck, J & Williams, R 1998, Exploring expertise: Issues and perspectives’, in R Williams, W Faulkner & J Fleck (eds), Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-13693-3_1

Flyvbjerg, B 2012, ‘Making Social Science matter’, in G Papanagnou (ed.), Social Science and policy challenges: Democracy, values, and capacities, UNESCO Publishing, Rochester, NY, pp. 25–56.

Friedli, L 2013, ‘What we’ve tried, hasn’t worked’: The politics of assets based public health’, Critical Public Health, vol. 23, pp. 131–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2012.748882

García, I 2020, Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD): Core principles, in R Phillips (ed.), Research handbook on community development, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK, pp. 67–75. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788118477.00010

Gibson-Graham, J 2006, A postcapitalist politics, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Gillespie, T 2010, ‘The politics of “platforms”, New Media Society, vol. 12, pp. 347–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809342738

Gray, M & Suri, S 2019, Ghost work: How to stop Silicon Valley from building a new global underclass, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston.

Haines, A 2014, ‘Asset-based community development’, in R Phillips & R Pittman (eds), An introduction to community development, Routledge, pp. 67–78. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203762639-14

Hay, J & Couldry, N 2011, ‘Rethinking convergence/culture’, Cultural Studies, vol. 25, pp. 473–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2011.600527

Indie Sellers Guild 2023, ‘About Us’ (www document), Indie Sellers Guild. https://indiesellersguild.org/about/

Indie Sellers Guild 2022, Indie Sellers Guild Media Coverage. https://indiesellersguild.org/media/

Israel, B, Schulz, A, Parker, E & Becker, A 1998, ‘Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health’, Annual Review of Public Health, vol. 19, pp. 173–202. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173

Jenkins, H 2008, Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide, University Press, New York.

Jenkins, H, Ford, S & Green, J 2013, ‘Spreadable media: Creating value and meaning in a networked culture’, Postmillennial Pop, New York University Press, New York and London.

Joyce, S, Stuart, M & Forde, C 2023, ‘Theorising labour unrest and trade unionism in the platform economy’, New Technology, Work and Employment, vol. 38, pp. 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12252

Kim, H 2019, ‘Essays on economic sociology of innovation and entrepreneurship’ (thesis), Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, MA.

Kretzmann, J & McKnight, J 1993, Building communities from the inside out: a path toward finding and mobilizing a community’s assets, The Asset-Based Community Development Institute, Chicago.

Lee McCarty, A 2021, The Etsy-sodes (Part I): Children’s books about fish + crafting as a political expression, Clotheshorse. https://clotheshorsepodcast.com/the-story-of-etsy-part-one/ (accessed 27.10.2023).

Levine, F & Heimerl, C 2008, Handmade nation: The rise of DIY, art, craft, and design, Princeton Architectural Press, New York.

Lévy, P 1997, Collective intelligence: Mankind’s emerging world in cyberspace, Perseus Books, Cambridge, Mass.

Luckman, S 2013, ‘The aura of the analogue in a digital age: Women’s crafts, creative markets and home-based labour after Etsy’, Cultural Studies Review, vol. 19, pp. 249–70. https://doi.org/10.5130/csr.v19i1.2585

Lutz, C, Hoffmann, C & Meckel, M 2014, ‘Beyond just politics: A systematic literature review of online participation’, First Monday. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v19i7.5260

MacLeod, M & Emejulu, A 2014, ‘Neoliberalism with a community face? A critical analysis of asset-based community development in Scotland’, Journal of Community Practice, vol. 22, pp, 430–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2014.959147

Maffie, M 2020, ‘The role of Digital Communities in organizing Gig Workers’, Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, vol. 59, pp. 123–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12251

Main, K 2022, ‘Small Business Statistics of 2023 – Forbes Advisor’ [WWW Document], Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/business/small-business-statistics/#small_business_ownership_statistics_section (accessed 8.1.2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/nba.31518

Matchar, E 2013, Homeward bound: Why women are embracing the new domesticity, Simon & Schuster, New York.

Mathie, A, Cunningham, G 2005, ‘Who is driving development? Reflections on the transformative potential of Asset-based Community Development’, Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue canadienne d’études du développement, vol. 26, pp. 175–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2005.9669031

Mathie, A & Cunningham, G 2003, ‘From clients to citizens: Asset-based community development as a strategy for community-driven development’, Development in Practice, vol. 13, pp. 474–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/0961452032000125857

McRobbie, A 2016, Be creative: Making a living in the new culture industries, Polity Press, Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA.

Morozov, E 2014, To save everything, click here: The folly of technological solutionism, PublicAffairs, New York.

Nieborg, D & Poell, T 2018, ‘The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity’, New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769694

Patel, K 2020, The politics of expertise in cultural labour: Arts, work, and inequalities, Rowman & Littlefield, London, Lanham.

Plummer, R, Witkowski, S, Smits, A & Dale, G 2022, Appraising HEI-community partnerships: Assessing performance, monitoring progress, and evaluating impacts, Gateways 15. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v15i1.8014

Postigo, H 2014, ‘The socio-technical architecture of digital labor: Converting play into YouTube money’, New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814541527

Putnam, R 2001, Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community, Simon & Schuster, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1145/358916.361990

Rheingold, H 1993, The virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

Roche, B 2008, New directions in Community-Based Research (White Paper), Wellesley Institute, Toronto, ON.

Rosenblat, A & Stark, L 2016, ‘Algorithmic Labor and information asymmetries: A case study of Uber’s drivers’, International Journal of Communication, vol. 10, p. 27.

Roy, M 2017, ‘The assets-based approach: Furthering a neoliberal agenda or rediscovering the old public health? A critical examination of practitioner discourses’, Critical Public Health, vol. 27, pp. 455–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2016.1249826

Sanchez-Cartas, J & León, G 2021, ‘Multisided platforms and markets: A survey of the theoretical literature’, Journal of Economic Surveys, vol. 35, pp. 452–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12409

Schrock, A & Close, S 2017, ‘Expertise and the constitution of publics’, Communication and the Public, vol. 2, pp. 193–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047317722798

Seller Policy (effective from 1 December 2022) – Our House Rules [www document] 2022, Etsy. https://www.etsy.com/legal/sellers/, https://www.etsy.com/legal/sellers/

Sen, A 1993, ‘Capability and well‐being’, in Nussbaum, M & Sen, A (eds), The quality of life, Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198287976.003.0003

Sennett, R 2008, The craftsman, Yale University Press, New Haven.

Silverman, J 2017, ‘Business as a force for good: Defining Etsy’s path’, Etsy News. https://www.etsy.com/news/business-as-a-force-for-good-defining-etsys-path

Stoller, D 2003, Stitch ’n bitch: the knitter’s handbook, Workman, New York.

Strand, K, Marullo, S, Cutforth, N, Stoecker, R, Donohue, P 2003, ‘Principles of best practice for Community-Based Research’, Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 9.

Surowiecki, J 2005, The wisdom of crowds, Nachdr. ed., Anchor Books, New York.

Thier, J 2022, ‘Thousands of Etsy sellers are planning a strike to protest new fee increases’, Fortune. https://fortune.com/2022/04/04/thousands-of-etsy-sellers-are-planning-a-strike/

Tönnies, F 2001, Community and civil society: Cambridge texts in the History of Political Thought, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Turkle, S 2011, ‘Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other, Basic Books, New York.

Wagner, K 2023, ‘Etsy promised shopping with a soul. Then the scammers came’, Washington Post.

Weber, M 2013, Economy and society: An outline of interpretive Sociology, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London.