PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies

Vol. 16, No.2

December 2023

RESEARCH ARTICLE (PEER-REVIEWED)

The Essential Role of ABCD in Developing Two Community Engagement Frameworks for Supporting Latinx Students

Marisol Morales

American Council on Education, United States

Corresponding author: Marisol Morales, MMorales@ACENET.EDU

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v16i2.8679

Article History: Received 20/06/2023; Revised 29/10/2023; Accepted 28/11/2023; Published 12/2023

Abstract

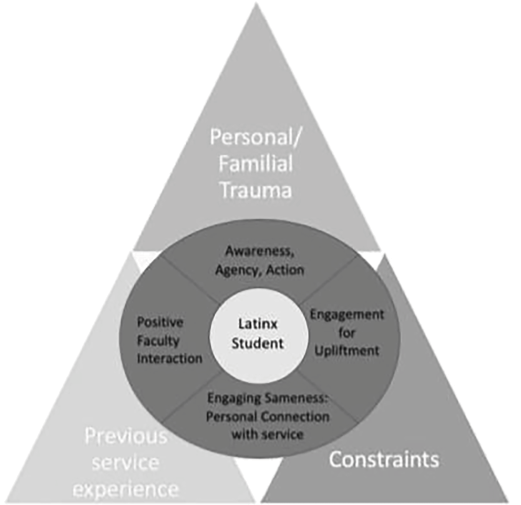

Asset Based Community Development (ABCD) is an important framework to understand and develop community-engagement experiences for Latinx students, especially at Hispanic Serving Institutions that play an important role in educating Latinx students. This article presents the conceptual findings of a research project that looked at the community-engagement experiences of Latinx students at an HSI. Drawing on in-depth interviews and critical frameworks for engagement, two models were developed: Prism of Liberatory Engagement and Asset Based Critical Engagement. These frameworks are presented as ways to (1) understand and differentiate the service learning experiences of Latinx students and (2) provide a framework for faculty and Community Engagement Professionals (CEPs) to situate their courses and community relationships, and work from an asset-based philosophy of engagement. The Prism of Liberatory Engagement gives explicit attention to the themes (awareness, agency and action; positive interaction with faculty; engaging sameness, and engagement for uplift) and the significant factors (personal/familial trauma, constraints and previous experience with service) that shape the community-engagement experiences of Latinx students. The Asset Based Critical Engagement model presented in this article provides a theoretical asset-based framework for critical pedagogy for service learning and community engagement that can be vital for institutions, in and outside of the United States, which are serving an increasingly diverse student population.

Keywords

Asset Based Community Development; Latinx Students; Hispanic Serving Institutions; Community Engagement; Service Learning; Prism of Liberatory Engagement; Asset Based Critical Engagement

Introduction

This article shares two community-engagement frameworks for supporting Latinx students in community engagement. The frameworks are deeply informed by Asset Based Community Development (ABCD). In this study, I sought to explicitly understand the community engagement experiences of Latinx students at a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI). Before presenting this research in detail, it is necessary to define these key terms: Latinx, Hispanic and Hispanic Service Institutions. I also briefly introduce myself, and the role that ABCD has played in my work and life.

Latinx is a gender neutral term and is specific to the United States. Latinx represents individuals who were either born in, or whose parents or ancestors were born in, Latin America or the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, but now reside in the United States, or whose ancestors were impacted by the border change that was a result of the Treaty of Guadalupe between Mexico and the United States. Latinx could be synonymous with the term Hispanic, but the term Hispanic can be a politically charged term since it tends to ignore the African or Indigenous influences in Latin America. In US demographics Hispanic is not a race but an ethnic category.

Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) is a designation granted to higher education institutions in the United States by the US Department of Education. To receive this designation, institutions must have a full-time undergraduate enrolment that comprises at least 25 percent Latinx students. This designation allows eligible institutions to apply for specific federal grants to assist these types of institutions in expanding educational opportunities for Latinx and other underrepresented populations. HSIs play a significant role in educating Latinx students in the United States. Excelencia in Education, a research and policy organisation that focuses on Latinx student success in higher education, identified 571 HSIs, 401 emerging HSIs and 241 Hispanic Serving Institutions with graduate programs in 2021–22. HSIs enrol 62 percent of all Latinx students and represent 19 percent of all institutions of higher education in the United States. They are located in 30 states and territories (Excelencia in Education 2023). Given their significant role in educating this demographic of students, HSIs should, theoretically, create an educational environment that serves and supports the specific needs of Latinx students, despite many of their roots being in Predominantly White Institutions (PWI) (Fosnacht & Nailos 2016).

Asset Based Community Development has been an important part of my understanding and practise of community work even before I had heard of this terminology. It was the way that I, an Afro-Puerto Rican woman born and raised in Chicago, understood grassroots activism and solidarity work. The power of a strong cultural identity, knowledgeable and determined activist ancestors, and my study of colonialism’s impact on Puerto Rico and its diaspora, seeded my resistance to erasure and invisibility. This awareness came about for me through an undergraduate service-learning course titled ‘US Colonialism of Puerto Rico’ in the last quarter of my second year at DePaul University in Chicago, Illinois. This course in an academic setting was the first time I learnt about my own history and culture. It provided me space to understand the socio-political and economic reasons my family migrated and to analyse and act upon this newly gained awareness through a community-engagement project. This experience also altered my educational and professional trajectory, leading me along a path to becoming an activist, community organiser and a higher education professional.

My own experience as a Latina student involved in community engagement also led to my decision to undertake research on community-engagement experiences of Latinx students. I wanted to deeply understand the impact, challenges and opportunities that community- engagement might have on Latinx students at an HSI. As I engaged in my research, I became aware that Latinx students were talking about their community-engagement experiences and the critical frameworks and pedagogies that were situated in my work. Critical Race Theory (CRT) scholars have demonstrated that United States’ history is embedded in structural racism and manifests in the fight for representation in the academy , 2009; McCoy & Rodricks 2015; Patton 2016; Solorzano & Villalpando 1998). According to the US Census, Latinx people make up 19.1 percent of the overall US population, while the US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (2021) shows that Latinx make up a quarter of the students in K–12 public schools and 17 percent of the undergraduate student population, but they only represent four percent of the total faculty population in the United States.

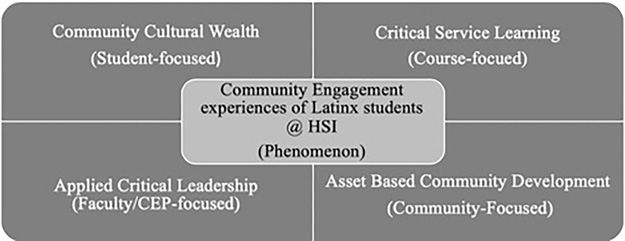

This phenomenological study explores the community-engagement experiences of Latinx students at an HSI. As a result, this article presents two conceptual models: (1) Prism of Liberatory Engagement and (2) Asset Based Critical Engagement, to better understand Latinx student engagement and offer critical pedagogies that are asset based and equity focused.

Theoretical Landscape and Critical Pedagogies

Asset-based community development is a community development model that originated in the fields of sociology and social policy (Donaldson & Daugherty 2011). It focuses on the strengths and capacities of the community and challenges the deficit-based approach often levied against communities. A deficits-based approach results in the following: (a) disempowerment of the community by relying heavily on outside experts; (b) resources and funding not being entrusted to residents but to services; (c) services being provided by outside entities, which does not provide direct economic benefit to community residents; (d) may promote a client mentality rather than a neighbour mentality; (e) community leaders being put in a position to denigrate the community by highlighting growing needs, gaps and wants, in order to receive funding; and (f) deepens dependency on outside entities (Donaldson & Daugherty 2011; Kretzmann & McKnight 1993). This deficit-based lens is often prescribed to communities of colour and low-income communities, in order to sustain manifestation of colonial practices in community development. In contrast, an asset-based approach identifies community assets. It looks at the skills, talents and abilities of local residents and amplifies their voices to address community issues. This appreciative method of community development honours community assets and recognises them as powerful tools for community empowerment, especially for communities that have been historically and structurally marginalised in society (Kretzmann & McKnight 1993).

Similarly, in many colleges and universities in the United States, community engagement has been embraced as one of the primary roles of institutions of higher education. Over the last thirty years, a growing movement has pushed colleges and universities across the country to re-examine and invest in their civic and community-engagement efforts because they see the important roles that colleges and universities play in educating an engaged and informed citizenry. In 2012, the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) published the report, A Crucible Moment: College Learning and Democracy’s Future, which argued that ‘colleges and universities are among the nation’s most valuable laboratories for civic learning and democratic engagement’ (The National Taskforce on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement, 2012, p. 2).

Service learning (SL) is one example of the ways in which this ‘civic learning and democratic engagement’ is taking shape. SL refers to the integration of theory and practice into an academic setting where action is realised through student participation in community service, volunteerism, advocacy, research, and so forth. According to Jacoby et al. (1996, p. 5), it is ‘a form of experiential education in which students engage in activities that address human and community needs, together with structured opportunities intentionally designed to promote student learning and development’. It melds community action with classroom learning through reflection. Its roots trace back to the 1960s social movements, but some of the earliest conceptions of it come from the 1860s land grant movement, progressive education and extension services (Stanton, Giles & Cruz 1999). Service learning, community-based learning, civic engagement and academic service learning are all names used to describe experiential learning courses that seek to link student learning with community-based learning experiences (Eyler & Giles 1999; Stanton & Giles 2017). Students make the connections between theory and practice through critical reflection (Mitchell 2008). This type of pedagogy is identified as a high-impact practice (Kuh 2008).

While many colleges and universities are developing criteria around civic learning outcomes and competencies to help support these efforts and increase student engagement, service learning is generally framed from the perspective of whiteness (da Cruz 2017; Hurtado 2006; Lee & Espino 2010; Mitchell, Donahue & Young-Law 2012). Pedagogy of whiteness refers to strategies that reinforce norms and privileges that were developed by white people and to benefit people who were perceived or classified as white. Whiteness continues to be replicated and it perpetuates a colour-blind and ahistorical view of societal issues and dismisses white privilege and structural racism as a key contributor to the issues faced by communities of colour. The perpetuation of colour-blind and charity dispositions in teaching service learning ignores racial realities and dismisses the experiences of Latinx students, and has the potential to reinforce stereotypes (Becker & Paul 2015; Endres & Gould 2009; Green 2001, 2003; Mitchell et al. 2012; Novick et al. 2011). In addition, from the early days of service learning, much of the benefits associated with it were seen as a model for teaching White middle-class college students about diversity and multiculturalism, and exposure to those different from themselves. This happened also through exposure or interaction with marginalised and oppressed communities, mainly communities of colour (Butin 2006; Dunlap 1998; Green,2003; Philipsen 2003 & Sperling 2007).

Recent research shows that Latinx students are participating in service-learning and community-engagement experiences at higher rates than those of white students (NSEE 2018), thus the changing demographics of college students in the United States necessitates a different approach to our work. The National Survey on Student Engagement 2018 report on High Impact Practices shows that senior Latinx students have higher service-learning participation rates than their white counterparts. Senior Latinx students are participating in service learning at a rate of 63 percent and white students at 60 percent (NSEE,2018). While participation rates in service learning for Latinx students are higher than those of their White counterparts (NSSE 2018), many of the community service projects and their framing are around problem-solving or experiencing diversity (Green, 2003; Jones, 2001; Mitchell, Donahue & Young-Law, 2012; Sperling, 2007).

There is growing awareness that the field of literature and how we consistently frame community engagement are not aligned with the increasing diversity of our student body in the United States, nor do the current theories capture what service-learning experiences are like for diverse students. My work seeks to contribute to and provide a more nuanced and authentic way to understand the community-engagement experiences of diverse students, especially Latinx students.

When applied to service learning, asset-based community development becomes an integral component of a social justice oriented course. It addresses issues of power, challenges students to look beyond how they might have been taught to view communities and their residents, and invites recognition of the local knowledge of community residents (Hamerlinck & Plaut 2014; Hastings 2016). ABCD in service-learning (Bauer, Kniffian & Priest 2015; Garroutte 2018; Shabazz & Cook 2014) pushes back on focusing on community needs and deficits in order to provide ‘help’, and instead invites students to engage in a process of discovery of community assets, such as the individual talents of community members and the formal and informal associations that exist within the community. It also explores how institutions such as schools, businesses, community organisations, etc. can be mobilised within the community for the community’s own benefit (Hamerlinck & Plaut 2014; Hastings 2016, Kretzmann & McKnight 1993). ABCD in service-learning is grounded in communities and their knowledge resources. This approach shifts traditional power dynamics to the university and the community. It can become an effective resource to access students’ cultural wealth by leveraging the knowledge they have of their communities, especially if those are the same communities they are being asked to engage with in their service-learning courses.

The Research methodology

Current literature in the field has focused little on the experiences of Latinx students (Langhout & Gordon 2021; Langhout, Lopezzi & Wang 2023; Smith-Warsaw, Crume & Pinzon-Perez 2020). This phenomenological research addresses that gap by focusing on and highlighting the community-engagement experiences of undergraduate Latinx students at a Hispanic Serving Institution. For this study, the stories and lived experiences of six current or recently graduated Latinx students, who had participated in service-learning experiences at a Hispanic Serving Institution, were collected through in-depth semi-structured interviews in order to generate the life stories of the participants.

Utilising phenomenological methodology, the researcher engaged in an interpretive process known as the hermeneutic cycle. This cycle includes reading, reflective writing and interpretation of the data gathered from in-depth interviews with research participants. The depth of knowledge gained and shared through a hermeneutic phenomenological study makes it a more relevant research methodology than a focus group. This hermeneutic phenomenological research study utilised social justice-oriented frameworks, such as community cultural wealth, applied critical leadership, critical service learning and ABCD.

An important element of hermeneutic phenomenological research is that the process of bracketing, or suspension of researcher’s understanding, is difficult (Kafle 2011). Thus, the researcher must acknowledge implicit assumptions and bring them forward explicitly. Given that the researcher is a practitioner in the field, the researcher can be seen as an insider. In addition, given that the researcher’s introduction to this work was by being a student of colour in an ethnic studies course, this shaped the researcher’s positionality and connection to the field of community engagement and her interest in HSIs and Latinx students. The researcher’s identity as an Afro-Puerto Rican cis-female, mother, educator and professional in the field was part of her subjectivity in the research. Although the researcher did not attend an HSI, she did work at one, and her introduction to community engagement came via a class that provided her with a culturally relevant and safe environment to engage with her own ethnic community, much like HSIs can do for Latinx students. The researcher was deeply connected to the research.

A purposeful sampling technique was used to select individuals to participate in the study. A homogeneous sampling process was applied because the researcher was selecting participants who (a) were over the age of 18, (b) had taken a service-learning course at the HSI, and (c) identified as a Latinx student. To find the individuals who possessed those characteristics, an eligibility survey was administered to each potential participant. The eligibility survey collected (a) demographic information, including age, gender, ethnic or racial background, parental status, work; (b) family background, including level of education of parents, language spoken at home, birthplace of parents, and so forth; (c) university experience, including major and minor involvement in clubs and activities, and participation in a community-engagement course. Eleven eligibility surveys were begun, nine were completed, eight individuals were invited to an interview, and six confirmed and participated in the interview. For the purposes of this study, the institution was given the pseudonym of North Star University. This particular university was selected because it is one of the oldest HSIs in the Midwest and because it has had programs serving Latinx students since the 1970s. North Star University is located in a large Midwestern city and in one of the most diverse neighbourhoods of that city. The University has a main campus and three satellite campuses.

The participants were both traditional and non-traditional students or recent graduates. There were four female-identified and two male-identified participants. The students interviewed were in different community-engagement courses, with different faculty, and engaged with different communities. Most of the faculty who were teaching the community-engagement courses were faculty of colour, 4 Black, 1 Latinx and 1 White. Students undertook their engagement at an on-campus food pantry, a community-based housing organisation and their high school, with a Latina-focused service and advocacy organisation. Using pseudonyms, the female participants were Janessa, Xaviera, Dana and Dora. The male participants were Josue and Adam. The service-learning courses were First Year Experience courses in Education, Justice Studies, Psychology and Internship s. Most participants took more than one service-learning course.

Acknowledging the limitation of the small sample size, the intent of this research study was to identify the manifestation of these community-engagement experiences to contribute to challenging the dominant narrative of needs, gaps and wants in the field and practice of community engagement. This study applied the frameworks of applied critical leadership, critical service learning and community cultural wealth, which are derived from CRT, as well as asset-based community development (ABCD) as the theoretical lens by which to analyse the interview data. These frameworks reinforced the interview data and data from the literature review, and provided support to the themes that were developed and addressed the research questions. The evidence that overlapped allowed for coding and theme development related to the community-engagement experience. The data that was repeated across five or more participants was synthesised into themes. The four themes that emerged from the data were:

1. Awareness, Agency and Action

2. Positive Interaction with Faculty

3. Engaging Sameness: Personal Connection to the Service

4. Engagement for Upliftment

Other evidence that emerged from the interviews, but independent of the classroom-based community-engagement experience, we identified as significant factors. These factors were significant to how the students interacted with and connected to the phenomenon. Significant factors were identified if they were shared by four or more of the participants.

The three significant factors were:

1. Personal/Familial Trauma

2. Constraints

3. Previous Experience with Service.

The themes and significant factors that emerged using the hermeneutic cycle of analysis of the stories were shared with all of the participants. CRT and social justice lenses helped shape a new conceptual framework, the Prism of Liberatory Engagement. The consistent appearance of the significant factor, which was outside the service-learning experience, but had influence on their engagement, led to the researcher to creating a place for them in the background of the themes that arose from the students’ community-engagement experience. Aligning it with the analogy of a prism that filters out or separates white light to see the spectrum of colour, the Prism of Liberatory Engagement allowed us to see the spectrum of experiences and factors that impact the community-engagement experiences of Latinx students.

Prism of Liberatory Engagement

The Prism of Liberatory Engagement invites community-engagement practitioners to understand their Latinx students’ experiences and create liberatory spaces for self-determination and self-actualisation in their classrooms and programs by inviting and validating different ways of knowing, reducing barriers, and kindling compassion and respect for self and others. Figuratively, a prism is ‘a way of looking at or thinking about something that causes you to see or understand it in a different way’ (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, n.d.). It allows the field of community-engagement to work against a dominant deficit ideology and to see Latinx community-engagement through a lens of community cultural wealth. It honours the knowledge that students bring with them about their community and does not presume the goal or outcome of their engagement. The model of the Prism of Liberatory Engagement is depicted below (Figure 1) and then explained section by section.

Prism of Liberatory Engagement

Awareness, Agency and Action

Awareness, Agency and Action is the process that the Latinx students in the study experienced in their community-engagement courses. The use of reflection in service-learning courses provides an opportunity for students to become aware of social inequality, and of themselves as community assets and agents of change, and has a long-term impact on students’ civic identity (Astin, Vogelgesang, Misa, Anderson, Denson, Jayakumar, Saenz & Yamamura 2006; Einfeld & Collins 2008; Sheil & Rivera 2016; West & Simmons 2012). The focus and framing of the community-engagement courses offers participants the opportunity to connect their learning and their lived experiences. This prior community knowledge enhances Latinx students’ community-engagement encounters by acknowledging the assets they bring to the institution and the community (Pérez Huber 2009; Littenberg-Tobias & Cohen 2016; Yosso 2005). They also understand that they, their families and/or their communities have experienced the social issues they were studying. The service-learning course included an opportunity to reflect on their own community’s experience. For example, the following quotation from Adam describes how the service-learning class in which he was enrolled increased his awareness:

I went into the course with an open mind and just with the procession of like the experiences that I already live. And like I said prior to your previous question, it just helped reinforce that. So, I already knew some of the stuff that was going on, but it helped explain, even gave me a broader sense of, you know, more issues that are actually correlated. So not just poverty and hunger and homelessness, but again social and structural barriers. You know, I didn’t know anything about that until that course. And then it helped me broaden on like how everything’s interconnected from politics to policymaking to taxes you know, high income neighborhoods to low income neighborhoods and the discrimination and inequality between them.

The service learning course provided the participants with language to understand and articulate the broader social issues at play that impact the everyday lives of the most marginalised. This newfound academic awareness of social issues also led to the development of agency. As Castañeda (2008, p. 325) states, ‘there is greater social awareness that emerged as a result of the intersection of the theory and praxis’. Community-engaged courses become an important space for deeper understanding to occur because of the ability to see how those broader issues play out in real-world settings and in real people’s lives, and for these participants in their own lives.

Participants identified seeing themselves as agents of change. For some, it was something they were able to realise through the service-learning experience or their time at the HSI they attended. The courses with engagement experiences were predominantly in the social sciences, from departments like Justice Studies or Psychology. These courses engaged with issues of social justice and communities. As Adam pointed out:

It helped me open my eyes to everything that really is going on in the world and gave me a sense of it, reinforce my goals, that I want to go to law school and become an immigration and criminal lawyer, and that would be my way of helping back African American and Latinx communities.

Yep and Mitchell (2017, p. 295) point out that framing community engagement in social justice and critical pedagogies unmasks ‘hegemonic power structures and foster[s] autonomy and self-determination’. The autonomy and self-determination they reference is agency. Agency in this context is imbued with critical analysis of the root cause of social issues. Agency is also the motivation that is reinforced by analytical awareness. The agency helped the Latinx students in my study understand their own ability to contribute and provided them with opportunities for action.

Action manifested in the ways the research participants took the class content and engagement and manifested it in action in their own lives. For some, this was teaching family and friends about what they were learning about social structures. For others, it was deciding what kind of career they wanted to pursue or discover their passions. But for all, it was an acknowledgment of themselves as agents of change. Critical service learning, a social justice-oriented service-learning pedagogy, is focused on this kind of social change orientation (Mitchell 2007). The action portion of this theme is situated in critical service learning’s social change orientation. This quote from Dora illustrates the connection between awareness, agency and action, and points towards a social change orientation:

And the professor always, I will never forget this because, she said this every single class, she’d always say that “you don’t have to change the world. You just have to change the ground underneath your feet.” And that really stuck with me and it’s something that I’ve continued to engage in and take with me. After being here, I was like, okay, well how can I apply everything that I learned there and change the ground underneath my feet. So, for me, food insecurity . . . was important and I felt like this course was going to teach me more about it.

Critical service learning is a service-learning pedagogy where students engage in analysis and reflection around power distribution, build meaningful relationships with the community and become more change-oriented. Critical service learning serves as one of the theoretical lenses used to interpret data and directly correlates with the theme of Awareness, Agency and Action. Students’ Awareness, Agency and Action emerged from a course-based process that links awareness of structural or social issues to the realisation that you have agency and power to create change, and the vehicle by which to enact that change. It creates a space for critical analysis of injustices faced by communities and offers participants an opportunity to see themselves as agents of change, not just in the immediate term, but as actors in long-term social change.

Positive Interaction with Faculty

All participants discussed and identified positive interactions with their faculty members from the community-based learning course. Specifically, the results of the study, in relation to positive faculty interaction, included three sentiments: (a) students felt that they were able to relate to the faculty; (b) they sensed that the faculty cared for them, and (c) they perceived that the faculty took time for them. These descriptions led to the second theme of positive interaction with faculty. Xaviera shared, ‘I’ve had very understanding professors; they didn’t put too much pressure on us. They were able to just talk to us like regular people.’ She also noted her service-learning professor, whose class she took as a first-year student:

She talked to us like normal people, you know, like we’re, we’re college students and she really wants us to learn and to help other students learn. I think that even now I still see her around the hallways and she’s very like, Oh my gosh, hi. You know, and very inviting. And I think that’s one thing that I really took away from her is that she sees you. She’s a great person and I want to be that person. You know, because I’ve always been a very kind of, I guess laid back, kind of reserved onto the side type of person. But, you know, I was so happy because she, she saw me and she like knew my name and it’s, I have a very difficult name to pronounce, but she still tried and was just very welcoming. And I think that’s how I want to be with anyone, especially with my young future students.

The emphasis on faculty in this study is consistent with what is in the literature regarding Hispanic Serving Institutions. Specifically, faculty who teach at HSIs are generally cognisant of the unique curricular needs of their Latinx students (Kiasatpour & Lasley 2008; Lara & Lara 2012; Garcia 2019). As the research participants noted in regard to positive faculty interaction, they felt they could relate to the faculty based on shared experiences. They also noted when that was not present. Most of the faculty that taught the engagement courses that participants were in were faculty of colour. Four of the six faculty were African American and one faculty was Latinx. As a student noted in the interview and I observed from the data, this alludes to solidarity in experiences shared by both African American and Latinx communities, especially as it relates to inequities that these communities face. A few of the students interviewed spoke to the similar experiences shared by Black and Latinx communities in the United States. The faculty who taught these courses had a justice orientation in their courses.

Garcia (2019) recommends that the reframing of the HSI narrative should include hiring faculty, staff and administrators committed to justice and liberation. This means that university leaders need to emphasise more than just demographic representation of faculty, but also invest in bringing on those who understand how larger systemic issues impact students. Those faculty committed to justice, love and liberation create opportunities for students to understand their own agency in creating change and do so in an assets-based way. For me, justice is restorative. It is, as Desmond Tutu stated, ‘concerned not so much with punishment as with correcting imbalances, restoring broken relationships – with healing, harmony and reconciliation’ (Tutu, p. 9) and this can only be done with disclosure and truth telling. Liberation, as I utilise it in this work and in my own practice, is tied to love. As hooks states ‘the moment we choose love we begin to move against domination, against oppression. The moment we choose love we begin to move towards freedom, to act in ways that liberate ourselves and others’ (1994, p. 297). In addition, hooks identifies that ‘critical pedagogies of liberation … embrace experiences, confessions and testimony as relevant ways of knowing, as vital dimensions of any learning process’ (hooks 1994, p. 88). The faculty, described by the participants in this study, do appear to possess that orientation towards justice, love and liberation.

Participants also noted that they felt like faculty cared and took time for them. They checked up on them, learned their stories, and gave of their time and made accommodations to help the participants manage the varied commitments and realities in their lives. This points to authentic caring by the faculty towards the participants and is an important aspect of positive interaction with the faculty. As Cammarota & Romero (2006, p. 16) point out, ‘authentic caring promotes student-teacher relationships characterized by respect, admiration, and love that inspires you Latinas/os to better themselves and their communities’. This was apparent in the participants’ experiences. They truly felt like their faculty cared for them. The sense of care and belonging, coupled with a social justice curriculum and community-engagement experiences, reinforced awareness, agency and action. The coupling of both positive interactions with faculty and awareness, agency and action inspired the participants to better themselves and their communities.

These positive interactions with faculty and the justice orientation demonstrated by faculty actions and the course content align with applied critical leadership. In applied critical leadership, educational leaders are considerate of the social context and considerate of their own identities, all through a Critical Race Theory lens (Santamaria & Santamaria 2012). According to the participants’ responses regarding their faculty, it appears that the faculty from the engagement courses were practising applied critical leadership in their community-engagement classes. The faculty engaged critical pedagogy and presented social justice content, utilising service-learning. Their classrooms and their interactions with the participants demonstrated both authentic care of the participants and presentation of counter-hegemonic content to challenge racism and oppression and move towards liberation. In addition, faculty of colour utilised their own identities to relate to the participants. As this quote by Adam indicates, the lived experience of his African American professor made an impact in the classroom:

She’s African American. She lived all her life in the Lincoln Park area that is very diverse with both Black and Latino communities. It made me stay the course and not drop it because she told us about her experiences, her struggles as a student. . . She had troubles at home as well. So, she really connected with a lot of the students and then she always created a safe space where she would never judge us and even allowed us to share our own personal experiences and our own struggles. The class, it felt more like family. Like you would just go in and it’s like you haven’t seen them in a while, but they just, understood you regardless of their ethnicity, we had a wide variety of [ethnicities]. From Asian students to White students to Latinx students and even African American students and even some transgender students. But it was just the wide range of everyone like understood each other. And there we validated each other’s struggles, each other’s experiences that we’ve gone through. So, it just felt we were a bit of a family.

The vulnerability in this faculty of colour in those who teach at this diverse institution may have been possible because their intersectional identities are seen as an asset in this diverse institution. Intersecting identities is a concept connected to intersectional theory, developed by activist and Professor of Law Kimberly Crenshaw, which says that an individual’s identity consists of multiple intersecting factors, including, but not limited to, gender identity, gender expression, race, ethnicity, class (past and present), religious beliefs, disability, sexual identity and sexual expression. In this HSI environment, the students felt safe to share their experiences because the faculty were transparent in sharing their own life experiences.

Engaging Sameness: Personal Connection with the Service

In the HSI in this study, community engagement has to be framed differently because the student body is extremely diverse. Most of the participants were born in the United States to immigrant parents. Their engagement activities are influenced by the realities of their social identities and lived experiences. Their intersectional identities influence the type of engagement they participate in and how they understand the course content. Janessa said that when her group was searching for a community on which to focus their service-learning project, this concept of engaging sameness was present: ‘We initially just wanted to help out a group and since most of the ones in our group are Latinx or Latinas, we wanted to help the Latinx population.’ In her resistance group, which was what the professor called the community-engagement project group, most of them had experience with how the current political climate surrounding immigration was impacting Latinx families. This quote demonstrates that personal connection:

My mother came here undocumented and received amnesty. And then my brother is an undocumented person also, but he has DACA [Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals] status, but then everyone else in my family is documented. So, it’s something that for a lot of the students that are in the resistance group we can connect to it. So that’s why we wanted to predominantly work with undocumented families.

The participants explained this reality when describing their community-engagement experiences. Their engagement occurred mainly with Latinx communities. They understood the broader social issues presented in their courses more intimately because they had faced those same issues. The issues of food insecurity, immigration, violence and discrimination were not abstract concepts; they were their own lived realities. According to a study by Stepick, Stepick & Labissere (2008), youth of immigrant origins do tend to engage in services that relate to the communities they are a part of more than the general population. They also bring that knowledge into the classroom and into their engagement experiences. As an example, all the participants spoke Spanish and were bicultural, and used those skills during their engagement activities.

The participants understood these sensitivities and expressed authentic empathy and compassion for those they served in their engagement projects. The undocumented woman they helped with a resume could have been their sister. The young woman they gave information to about domestic violence could have been their aunt. The inmate who received their letters could have been their cousin. All of the participants possessed a connection to the service in which they were engaged, whether it be because their families were experiencing housing or employment discrimination or the deep fear that resides in mixed status households where the fear of deportation is an everyday reality. The demonstration of the theme of Engaging Sameness drew on the community cultural wealth they brought to the university. This appeared to be both acknowledged and respected by the faculty who taught their engagement courses. The community cultural wealth theory, developed by Yosso (2005), is based on critical race theory (CRT). CRT takes a critical approach to examining society and culture and their intersection with race, power and privilege. This approach challenges the deficit model that communities of colour are often subjected to and applies a broader appreciative lens to the cultural values, skills, abilities and relationships that exist in marginalised communities (Littenberg-Tobias & Cohen 2016; Pérez Huber 2009; Solorzano & Yosso 2002; Yosso 2005).

Yosso’s (2005) theory of community cultural wealth utilises CRT to contest traditional interpretations of cultural capital. She sought to bring to the forefront the cultural capital that marginalised communities have, which is rarely acknowledged or recognised by mainstream society. In her work, she identified six types of cultural capital that educators can utilise in their interactions with students. The six forms of cultural capital are aspirational, linguistic, familial, social, navigational and resistance. These forms of cultural capital can be used to help educators understand how Latinx students access and experience college, from an asset-based perspective.

This strengths-based framework (Yosso 2005) acknowledges the cultural and social assets that students bring from their communities as a way of challenging the structures of inequity that exist in academia. Aspirational capital is associated with the hopes and dreams of the participants to pursue and complete their higher education. Linguistic capital was present when participants used their bilingual and bicultural skills at their community-engagement sites, and were able to connect with members of the community they were serving. Navigational capital appeared in the way participants had to navigate college as first-generation students, students whose parents did not attend college, and find their way in order to access resources available to them. This was most prevalent for the first-generation transfer students. Resistant capital was demonstrated in their persistence and commitment to complete their education despite obstacles and barriers they faced. Social capital was how they accessed and connected to networks of people and community resources that helped them navigate mainstream institutions, such as the university, public school system, or community-based organization, to find engagement projects that were meaningful for them. Familial capital appeared in the ways they continued to connect to their community or were able to develop that sense of belonging and community in the classroom. This came with developing relationships with faculty and staff on campus and a network of friends to access for support. The conceptual framework of community cultural wealth allowed this study to identify the understanding, familiarity and knowledge that participants possessed as the theme of Engaging Sameness.

Engagement for Upliftment

Engagement for upliftment signifies the ways in which the participants interpreted or defined community-engagement as a service of bettering, empowering or uplifting the community. Also, it includes aspects of reciprocity, as well as how they see themselves as agents of change or how their future careers will be focused on uplifting and helping their community. The notion of self-efficacy is at the heart of upliftment. The civic identities of the participants were bolstered by their ability to make positive change in the community (Alcantar 2014) and understand their role in that change. Engagement for upliftment became a reciprocal cycle of acknowledgement of what was given by the community to help get the participants to where they are, and what the participants in turn provide the community through their engagement, and then, what the community and participant both received from that engagement for their mutual upliftment. In this quote, Josue discusses the reciprocal nature of working with the community and how it felt for him to complete his service project at the high school that he graduated from.

I felt great because it is important to give back to the community because who knows, the community could give back to you one day.

Similarly, Adam said:

Like my mother would say, it doesn’t matter how far in the education system, you may be, a PhD professor or doctorate, whatever, but never forget your roots and where you come from. And never forget the people that helped you get to where you are. And if you have a chance to give back, do it because you never know. That chance that you, that fighting chance, that you give a person back might be their chance in order to succeed to where you are now.

Upliftment refers to the responsibility that participants felt toward the Latino community’s betterment, as well as acknowledgement of what they received from the community that assisted them in their own journey. The acknowledgement of privilege is a key aspect of engagement for upliftment.

Asset Based Community Development (ABCD) (Kretzmann & McKnight 1993) is centred on identifying assets and mobilising those assets to facilitate change. The model is based on identification and appreciation of the gifts, talents and abilities that individuals, institutions and communities possess and how these are accessed and mobilised to confront challenges. In this study, those features were displayed in the ways that the participants described their community engagement, themselves as agents of change, and where they saw their future involvement and role in uplifting the community.

Significant Factors

The three significant factors were underlying realities that did not have to do with the specific course-based community engagement experience, but did influence their experience. Thus, the researcher determined that these factors were worthy of mention and identification. The three significant factors were Personal/Familial Trauma, Constraints, and Previous Experience with Service.

Each of the participants shared a personal or familial experience with trauma. For one it was the fear of deportation of her brother because he was undocumented, even though he had DACA status. In addition, this same student indicated that her mother had been a battered woman. For others, it was violence – either violence that they had experienced directly or violence in the community that they lived in, such as hearing gunshots, and the fear that caused them. For at least two students, they had childhoods that were impacted by their parents’ dysfunctional relationships. This trauma had some impact on what they did as part of their service or what they decided they wanted to study or do for their careers. The prevalence of these stories in the lives of the participants, and the participants connecting them to their class, education and/or community engagement experiences, is what made the researcher identify this as a significant factor.

Another significant factor was the constraint that participants felt. The most prevalent constraint was time, because of their need to work and financially support themselves and their families. Another constraint was economic. Most of the participants were paying for their own education. The final constraint for students, which emerged in the significant factors portion of the framework, was having a strict family that did not allow them to be out past a certain hour or limited where they could go or be outside of school. These constraints limited their ability to engage fully in campus life and the kinds of engagement opportunities in which they could participate.

The final significant factor for the participants was previous experience with service. Four of the six participants identified previous experience with service, either related to their time in high school and/or as part of their religious background and identity. This previous experience with service seemed to predispose them to selecting community engagement when it was an option or seeking that kind of experience from their academic program.

These significant factors demonstrate the need to be more expansive and inclusive of the external factors that impact the engagement experiences of Latinx students and other students of colour (Alcantar 2014). The researcher could not have fully understood the phenomenon of the community-engagement experiences of Latinx students at an HSI without having understood or made room for external factors that students brought to their experiences. These significant factors did have an impact on the students’ experience of the phenomenon. While most of the research on community engagement is more classroom-based and focused on learning outcomes, this study sought to be more socio-centric. The inclusion of these significant factors provided a space to discuss the interplay between the students’ life and the classroom. Latinx students are at the centre of this experience, but the underlying reality is the basis for the significant factors. The community-engagement experience is demonstrated in the overlaid circle. The four quadrants of the circle identify the essence of the experience and the major themes that the data revealed of the phenomenon. This model is a depiction of the influence of the significant factors on the participants’ community-engagement experience and the students’ overall experience of higher education. Together, the themed experiences and the significant factor form the Prism for Liberatory Engagement (Figure 2).

Asset Based Critical Engagement

Asset Based Critical Engagement

As has been shown above, the constant back and forth between interview data, critical frameworks, reading and reflective writing led the researcher to propose a second model, Asset Based Critical Engagement. Asset-based critical engagement is an engagement framework that seeks to intentionally identify and position community-engagement experiences with all people within the context of their location and experiences. The visual depicts the interplay of the themes and critical pedagogies that form the foundation of the model of Asset Based Critical Engagement.

Community Cultural Wealth

Within the model of the Prism of Liberatory Engagement, the theme of Engaging Sameness: Personal Connection to the Service, aligned with community cultural wealth. The data from the interviews supported Yosso’s (2005) research on community cultural wealth, which was a theoretical framework employed in this research. This was demonstrated in the ways the participants connected to linguistic capital, familial capital and aspirational capital.

Applied Critical Leadership

The theoretical framework of Applied Critical Leadership was prevalent in the theme of Positive Interaction with Faculty. The fact that five of the six faculty who taught the community- engagement course, in which students were enrolled, were faculty of colour demonstrates the importance of both representation and authenticity in the faculty. Although the difficulty of recruitment made it impossible to only select participants who had participated in ethnic studies courses that included community-engagement, what did become apparent was that the ethnic/racial background of the faculty mattered. Participants felt safe enough to share their lived experiences in the classroom because of the type of space that the faculty created through the sharing of themselves. thus participants did connect their course-based community engagement to the local Latinx community.

Critical Service Learning

In this study, critical service learning was apparent in the theme of Awareness, Agency, and Action. Through the course content, participants were able to move through this process, whereby faculty employed the markers of critical service learning. This course-focused approach created a classroom space for a social change orientation to develop in the students by activating their agency, increasing their awareness, and offering tangible opportunities for action.

Asset-Based Community Development

This critical concept was connected to the theme of Engagement for Upliftment. Engagement for Upliftment became a reciprocal cycle of acknowledgment of what was given by the community to help get the participants to where they were, what the participants in turn provided the community through their engagement, and what both the community and participants received from that engagement for their mutual upliftment. In this sense, the assets, skills and contributions of the students were employed in their communities, whether it be Spanish language skills, lived experience, or compassion and empathy at their placement site. Those assets were brought forward not for the purpose of their own benefit, but for the benefit and upliftment of their communities. They hold a responsibility to their communities precisely because they see them as contributing to their path toward higher education. They understood what their communities had given them and now had the opportunity to reciprocate. In this way, ABCD leads to the empowerment of both the students and the community.

Asset Based Critical Engagement is a framework for practitioner engagement and reflection that seeks to leverage the strengths, talents and skills of students, faculty and the community to create classrooms and community spaces that critically analyse and interrogate systems of inequality. It is inclusive of the community cultural wealth that Latinx students bring to their institutions and their community-engagement experiences and take into account the external factors that impact their engagement. Asset Based Critical Engagement invites course content that is social justice oriented and encourages critical analysis of social structures and inequities in an environment based on authentic community partnerships that support Latinx students in the discovery and execution of their own agency as change makers. This model encourages faculty/practitioners to embrace applied critical leadership as a practice that honours their authentic selves and their own community cultural wealth in supporting diverse students in their persistence and their sense of belonging. It also honours the contribution to and assets of the community through asset-based community development. This is the basis for reciprocity between students and their communities, in the context of the significant factors of trauma, constraints and previous experience with service. This practice then becomes a means to respond and act through these strengths-based approaches that activate one’s own agency in creating change.

ABCD’s interaction with this research and its influence on both the Prism of Liberatory Engagement and Asset Based Critical Engagement lends to seeing Latinx students and their communities from a place of inherent value. An Asset Based Critical Engagement orientation serves as a benefit to the Latinx students and communities whose experiences and interactions are being viewed and understood as a counter-narrative to the current positioning within community engagement that often places marginalised communities as recipient and not co-creator. Asset Based Critical Engagement is a model that creates space and leverages the assets of the faculty and practitioners who adopt a liberatory lens through their applied critical leadership in their classrooms and interaction with students, and it understands that community partnerships are the cornerstone of this work.

Concluding Thoughts

The participants in this study shared their service learning experiences at an HSI. The data collection and analysis revealed the participants’ lived experiences with community engagement and elevated four main themes: Awareness, Agency and Action; Positive Interaction with Faculty; Engaging Sameness: Personal Connection to the Service; and Engagement for Upliftment. The analysis also revealed significant factors that, although not directly emanating from the community-engagement experiences, did impact them. Their reflection on their experiences offered a glimpse into the community– engagement experiences of Latinx students, both the visible and invisible. All participants valued the community-engagement experience as positive and eye-opening, and saw themselves as agents of change. The themes and the factors were important to both providing evidence to answer the research questions and to informing the practices of the broader field of community engagement. The research findings led to the creation of the Prism of Liberatory Engagement and Asset Based Critical Engagement.

The findings of this research study are significant for five reasons. First, the focus on Latinx students aligns with the future demographics of higher education and the diverse student body we are called to serve regardless of institution type. Second, the two models offer a critical tool for practitioners to situate their own engagement practice to better serve their Latinx studentsr. Third, in the field of community engagement, more attention has to be given to the intersection of diversity/equity and community engagement. This research helps to fill that gap. Fourth, the study challenges the dominant narrative of needs, gaps and wants that has dominated the field and practice of community engagement. Finally, the findings can stand to inform administrators and practitioners of the vast assets and community cultural wealth that exist in the communities that Latinx students are coming from, and going back to, for their community-engagement experiences.

ABCD, as a foundation for these two models, offers an orientation geared towards challenging historical deficit narratives imposed on Latinx students and their communities. The situatedness of an HSI provides an access point for the growing number of PWIs that are quickly turning into HSIs to begin to imagine how their engagement strategies need to evolve to serve a more diverse student population. Hispanic Serving Institutions will have to grapple with the tension between merely enrolling and properly engaging and serving Latinx students. The Prism of Liberatory Engagement and Asset Based Critical Engagement, through its ABCD orientation, can serve as tools for discernment and practise as institutions of higher education embrace the responsibility and reward of serving Latinx and other historically marginalised students.

References

Alcantar, C 2014, ‘Civic engagement measures for Latina College Students’, New Directions for Institutional Research, vol. 158, pp. 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.20043

Astin, A, Vogelgesang, L, Misa, K, Anderson, J, Denson, N, Jayakumar, U, Saenz, V & Yamamura, E 2006, Understanding the effects of Service-Learning: A study of students and faculty, Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA.

Butin, D 2006, ‘The limits of service-learning in higher education’, Review of Higher Education, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 73–498. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2006.0025

Cammarota, J & Romero, A 2006, ‘A critically compassionate intellectualism for Latina/o students: Raising voices above the silencing in our schools’, Multicultural Education, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 16–23.

Castañeda, M 2008, ‘Transformative learning through Community Engagement’, Latino Studies, vol. 6, pp. 319–26. https://doi.org/10.1057/lst.2008.35

Donaldson, L & Daugherty, L 2011, ‘Introducing asset-based models of social justice into service learning: A social work approach’, Journal of Community Practice, vol. 19, pp. 80–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2011.550262

Du Bois, WEB 1968, The souls of black folk: Essays and sketches, AG McClurg, Chicago 1903; Johnson Reprint Corp, New York, NY.

Dunlap, M 1998, ‘Adjustment and developmental outcomes of students engaged in Service Learning, Journal of Experiential Education, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 147–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382599802100307

Einfeld, A & Collins, D 2008, ‘The relationship between Service Learning, Social Justice, Multicultural Competence and Civic Engagement’, Journal of College Student Development, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2008.0017

Excelencia in Education 2023, ‘Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSIs)’, Infographic 2021–22, Washington, DC.

Fosnacht, K & Nailos, J 2016, ‘Impact of the environment: How does attending a Hispanic serving institution influence the engagement of Baccalaureate-seeking Latina/o students?’ Journal of Higher Education, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192715597739

Garcia, G 2019, Becoming Hispanic-serving Institutions: Opportunities for Colleges and Universities, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Garroutte, L 2018, ‘The sociological imagination and community-based learning: Using an Asset-based approach’, Teaching Sociology, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 148–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X17750453

Garoutte, L & McCarthy-Gilmore, K 2014, ‘Preparing student for community-based learning using an asset-based approach’, Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 48–61. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotlv14i5.5060

Green, A 2003, ‘Difficult stories: Service Learning, Race, Class and Whiteness, College Composition and Communication, Urbana, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 276–301. https://doi.org/10.2307/3594218

Hamerlinck, J & Plaut, J (eds) 2014, Asset-based community engagement in Higher Education, Minnesota Campus Compact, Minneapolis, MN.

Hastings, L 2016, ‘Intersecting Asset-Based service, strengths, and mentoring for socially responsible leadership’, New Directions for Student Leadership, vol. 150, pp. 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20173

Holsapple, M 2012, ‘Service-Learning and student diversity outcomes: Existing evidence and directions for future research’, Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, Spring, pp. 5–18.

hooks, b. 1994, Outlaw culture: Resisting representation, Routledge, New York.

Jones, S & Hill, K 2001, ‘Crossing High Street: Understanding diversity through Community Service-Learning’, Journal of College Student Development, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 204–16.

Kiasatpour, S & Lasley, S 2008, ‘Overcoming the challenges of teaching Political Science in the Hispanic-serving classroom: A survey of Institutions of Higher Education in Texas. Journal of Political Science Education, vol. 4, pp. 151–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512160801998064

Krtezmann, J & McKnight, J 1993, Building communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community’s assets, ACTA Publishing, Chicago, IL.

Langhout, R & Gordon, D 2021, ‘Outcomes for underrepresented and misrepresented college students in service-learning classes: Supporting agents of change’, Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 408–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000151

Langhout, R, Lopezzi, M & Wang, Y 2023, ‘Not all service is the same. How Service-Learning typologies relate to student outcomes at a Hispanic-serving Institution’, Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 73–89.

Lara, D & Lara, A 2012, From ‘Hell No!’ to Que pasó?’: Interrogating a Hispanic-serving institution possibility’, Journal of Latinos & Education, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 175–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2012.686355

Lee, J & Espino, M 2010, ‘Diversity and Service Learning: Beyond individual gains and toward social change’, College Student Affairs Journal; Charlotte, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 1–16, 91–93.

Littenberg-Tobias, J & Cohen, A 2016, ‘Diverging paths: Understanding racial differences in civic engagement in White, African American and Latino adolescents using structural equation modeling’, American Journal of Community Psychology, vol. 57, pp. 102–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12027

Merriam-Webster 2020, Awareness, in Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/awareness

Mitchell, T 2007, ‘Critical Service-Learning as Social Justice Education: A case study of the Citizen Scholars Program’, Equity & Excellence in Education, vol. 40, pp. 101–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665680701228797

Mitchell, T 2008, ‘Traditional vs Critical Service-Learning’, Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, pp. 50–65.

Mitchell, T, Donahue, D & Young-Law, C 2012, ‘Service Learning as a pedagogy of whiteness’, Equity & Excellence in Education, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 612–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2012.715534

Mitchell, T 2015, ‘Using a Critical Service-Learning approach to facilitate civic identity development’, Theory Into Practice, vol. 54, pp. 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2015.977657

Mitchell, T 2017, ‘Teaching community on and off campus: An intersectional approach to Community Engagement’, New Directions for Student Services, vol. 157, pp. 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.20207

National Center for Education Statistics 2022, ‘Characteristics of post-secondary faculty: Conditions of education’, U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved 31 May 2022. https://nces.ed.gob/programs/coe/indicators/csc

Novick, S Seider, S & Hughley, J 2011, ‘Engaging college students from diverse background in Community Service Learning, Journal of College & Character, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–8. https://doi.org/10.2202/1940-1639.1767

Perez, W, Espinoza, R, Ramos, K, Coronado, H & Cortes, R 2010, ‘Civic engagement patterns of undocumented Mexican students’, Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, vol. 9, no. 3, 245–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192710371007

Pérez Huber, L 2009, ‘Challenging racist nativist framing: Acknowledging the community cultural wealth of undocumented Chicana College students to reframe the immigration debate’, Harvard Educational Review, vol. 79, pp. 704–730. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.4.r7j1xn011965w186

Philipsen, M 2003, ‘Race, the college classroom, and Service Learning: A practitioner’s tale’, Journal of Negro Education, vol. 72, no. 2, pp. 230–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/3211172

Samuelson, C & Litzler, E 2016, ‘Community cultural wealth: An Assets-Based approach to persistence of engineering students of color’, Journal of Engineering Education, vol. 105, pp. 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20110

Santamaria, L & Santamaria, A 2012, Applied critical leadership in Education: Choosing change, Routledge, New York.

Santamaria, L & Santamaria, A (eds) 2016, Culturally responsive leadership in Higher Education: Promoting access, equity, and improvement, Routledge, New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315720777

Sheil, A & Rivera, J 2016, ‘Reaching back strategy: Using mirroring, trust, and cultural alignment in a Service-Learning course to impact Hispanic parents’ perception of College’: A case study’, Journal of Latinos and Education, vol. 15, pp. 140–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2015.1066253

Smith-Warsaw, J, Crume, P, Pinzon-Perez, H 2020, ‘Impact of Service-Learning on Latinx College students engaged in intervention services for the deaf: Building multicultural competence’, International Journal of Multicultural Education, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 50–75. https://doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v22i3.2413

Sperling, R 2007, ‘Service-Learning as a method of teaching multiculturalism to white College Students’, Journal of Latinos and Education, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 309–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348430701473454

Stepick, A, Stepick, C & Labissiere, Y 2008, ‘South Florida’s immigrant youth and civic engagement: Major engagement: Minor differences’, Applied Development Science, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888690801997036

Taylor, M, Dwyer, B & Pacheco, S 2005, Mission and Community: The culture of community-engagement and minority serving institutions, Higher Education collaboratives for community engagement and improvement, Education Scholarship, Paper 4. http://scholars.unh.edu/educ_facpub/4

Tutu, D 1998, ‘Foreword by Chairperson’, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume One. http://www.justice.gov.za/trc/report/finalreport/Volume%201.pdf

The National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement 2012, A crucible moment: College learning and democracy’s future, Association of American Colleges and Universities, Washington, D.C.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), Spring 2019 through Spring 2021, Human Resources component, Fall Staff section.

West, J & Simmons, D 2012, ‘Preparing Hispanic students for the real world: Benefits of problem-based Service-Learning projects’, Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, vol. 11, pp. 123–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192712437037

Yep, K & Mitchell, TD 2017, Decolonizing Community Engagement: Reimagining Service Learning through an Ethnic Studies lens, in C Dolgon, T Mitchell & T Eatman (eds), The Cambridge Handbook of Service Learning and Community Engagement, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 294–303. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316650011.028

Yosso, T 2005, ‘Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth’, Race Ethnicity and Education, vol. 8, pp. 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/1361332052000341006