Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 16, No. 2

December 2023

Research article (Peer-reviewed)

Faith-Based Community-Academic Partnerships: An Asset-Based Community Development Strategy for Social Change

Linda Silver Coley1, Elizabeth Stryon Howze2, Kyle McManamy3

1 Executive Director, The Ormond Center at Duke Divinity School, Duke University, 407 Chapel Dr., Durham, NC 27708.

2 Director of the Academy of Teaching, Training, and Learning, The Ormond Center at Duke Divinity School, Duke University, 407 Chapel Dr., Durham, NC 27708.

3 Director of Strategic Projects, The Office of the Dean at Duke Divinity School, Duke University, 407 Chapel Dr., Durham, NC 27708.

Corresponding author: Linda Silver Coley, lcoley@div.duke.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v16i2.8672

Article History: Received 17/06/2023; Revised 22/10/2023; Accepted 03/11/2023; Published 12/2023

Abstract

Faith-based community anchor institutions are important collaborators in community development. They are respected social innovators who deploy their assets for the common good, especially good works aimed towards helping marginalised communities and those in poverty. More recently, the pace of faith-based social innovation and community development leadership has slowed substantially (Jones 2016). Seeking renewed imagination, will and ability for asset-based social innovation among faith-based communities, the Ormond Center at Duke University’s Divinity School has developed a curriculum, based on a human ecology framework, that engages faith-based ‘community-academic partnered participatory research’ (Chen et. al. 2006) towards social change. Our approach starts by working with congregations to discover community-level barriers to thriving in their local context. We then walk alongside faith-based communities to identify strengths-based, relationship-centred opportunities to collaboratively integrate congregational assets with community assets towards positive social change. This curriculum has been tested by the Ormond Center with several diverse, multi-denominational congregations in communities located in North Carolina and Virginia. Its potential to encourage asset-based community development for social good is supported by tangible evidence. This article takes the reader through the process of changing a semester-long graduate course, designed by the academy for the academy, to a six-week course that walks alongside faith-based lay leaders and pastors in their local context, towards asset-based community development for positive social change. Five viable asset-based solutions to community-level social issues are shared, and lessons learned are offered.

Keywords

Asset-Based; Endowments; Faith-Based; Human Ecology; Relationship-Centred; Social Innovations

Introduction

Asset-based community development (ABCD) links the assets of local communities to social change. In earlier years, American faith-based communities practised a version of asset-based community development. These faith-based community development organisations (FBCDOs) invested their assets in local places, projects and people groups to effect positive social change. Supporting this point of view, L Gregory Jones (2016, p. 5) offers, ‘For most of American history, faith-based communities led the way in innovative approaches in sectors such as education, health, housing, and food, just to name a few.’ An example from the education sector reminds us of the time in United States history when African Americans were forbidden access to higher education. Then, FBCDOs stepped in to address this racial inequality that caused educational disparities and birthed more than two hundred historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) that continue to serve US communities today (see Consecrated Ground: Churches and the Founding of America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities | National Museum of African American History and Culture: Smithsonian).

John P Kretzmann & John L McKnight (1993, p. 143) also lend insight to the contributions and significance of faith-based institutions in asset-based community development, claiming that:

[n]eighborhood religious institutions have an abundance of resources that can contribute directly to the process of rebuilding communities. As a matter of fact, many churches and synagogues have already begun to utilize their resources within the community in extremely creative and innovative ways and thus have become centers for interaction between local individuals, groups, associations, and institutions. In other words, at the present time many contemporary religious leaders have come to understand that they cannot continue to remain viable within their community unless they learn to develop vital links to the development and improvement of that community. This understanding has led to an astounding variety of creative approaches to community-building by religious institutions.

However, as Jones (2016, pp. 5–8) claims, more recently, the pace of faith-based communities’ asset-based social innovations appears to have slowed substantially. While we do not have a specific answer for this, it coincides with the rapid pace of decline in church attendance and religious affiliation noted between 2007 and 2019 (Smith, Schiller & Noland 2019, Pew Research Center). Other research suggests not only has the pace, but the depth of social-change efforts, appear to have altered. In his book about community economic development, David Kresta (2021, p. 9) acknowledges that, while churches ‘[… have] a long history of social service programs, … a common critique of social service programs is that they do not address the root cause of poverty nor create long-term change.’ In apparent agreement with Kresta’s opinion, Fitzgerald (2009, p. 181) highlights the more traditional view of FBCDOs’ role in the community, which is ‘providing charity … (e.g. soup kitchens and temporary shelter), before he acknowledges movement ‘into other forms of social service provision including job training, permanent low-income housing and small business loans.’ This latter type of social service provision might suggest the potential for innovative, long-term positive change.

This article seeks to pick up on the faith-based community’s long, if intermittent, history of profound social innovation, asking: What would be the societal impact if faith-based communities everywhere experienced renewed imagination and intentionally practised asset-based community development with a goal of generating sustainable positive social change? Put another way, what if faith-based community partners innovatively operationalised the biblical charge to live out faith in action (James 2:14-17) in collaboration with other community constituents and stakeholders to serve the marginalised and address the barriers to thriving in their shared community? Seeking answers to such questions, the Ormond Center (TOC) at Duke Divinity School (DDS) posits that faith-based community-academic partnerships with renewed imagination, will and ability can be deployed towards sustainable social change, using asset-based community development strategies that address barriers to thriving congregations and communities.

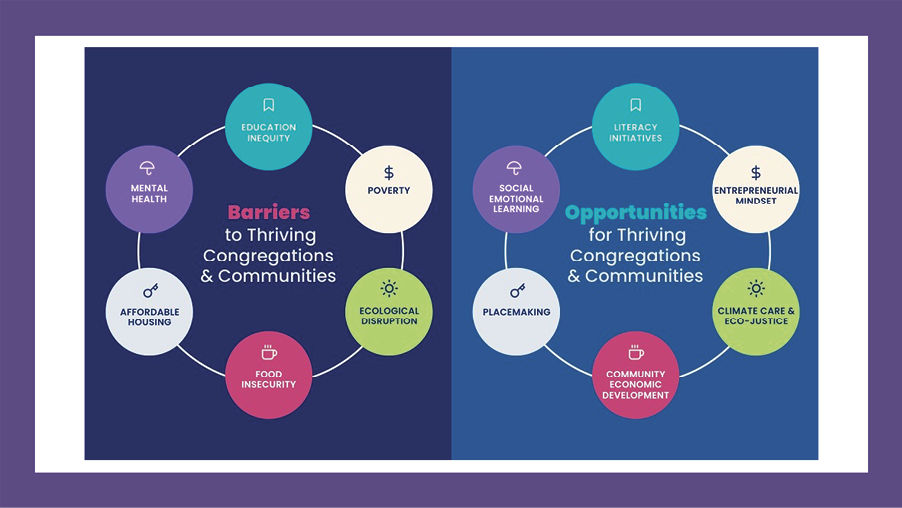

Believing that an intentional process could generate opportunities for social impact creation, TOC and its faith-based partners identified some of the major barriers to thriving congregations and communities in their local context and sought opportunities to address them together (see Figure 1). We believe that if congregations participate in the process of identifying, understanding and addressing these complex barriers to community thriving, then congregations will thrive as well.

Figure 1. Thriving Congregations and Communities: Barriers and Opportunities

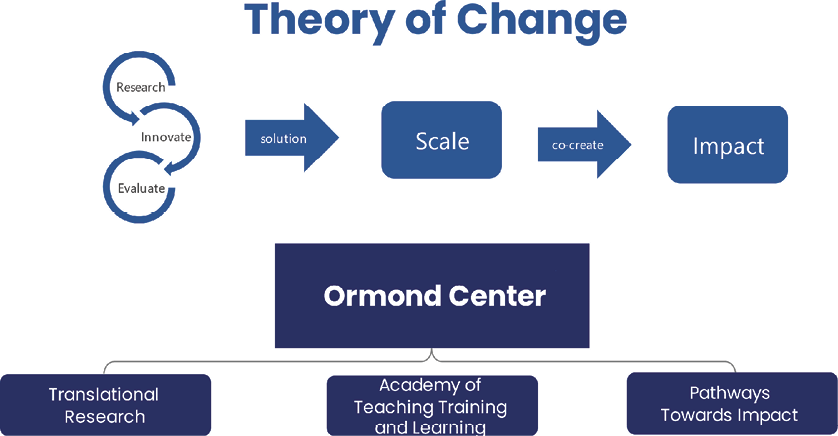

To guide our hypothesis, we developed a theory of change (see Figure 2). It begins with iterations of research, innovation and evaluation, and ends with impact co-creation alongside faith-based organisations in the communities that we share. The hope is to be able to scale the innovations towards evidence-based sustainable change across local, state and global communities.

To implement this theory of change, The Ormond Center reorganised into three distinct areas, Translational Research, the Academy of Teaching, Training and Learning, and Pathways Towards Impact (see Figure 2).

Working alongside local congregations in Durham and Chapel Hill, North Carolina, we integrated local faith-based organisations and community stakeholders into the asset-based community development conversation using a curriculum based on human ecology theory. According to Tulchinsky & Cohen (2023), human ecology theory, which was ‘introduced in the 1920s and revived in the 1970s, attempts to apply theory from plant and animal life to human communities’. Application of the human ecology concept to the ABCD conversations generally ‘involves the interrelationship among people, other organisms and their environment’ (Steiner 2008). Taking a quasi ‘human ecology theory’ approach to human flourishing and reflecting on the work of urbanist Jane Jacobs (2011), Joshua J. Yates (2017), who developed the Human Ecology Framework to capture shalom in practice, expands human ecology theory, saying

[h]uman ecology stresses the fact that cities are neither collections of autonomous individuals or discrete problem areas (like poverty or affordable housing) each hermetically sealed from one another; nor do cities behave like mechanical systems that can be managed and controlled by rational experts from on high. … A human ecology approach sees cities as complex, asymmetric, and dynamic social organisms that both empower and constrain the ways of life and life chances of their residents. The concept of human ecology thus enables us to think about the shape and character of concrete places and people in the most culturally and historically robust terms.

In the next section, we introduce the Human Ecology Framework, and take the reader through the development of one of our programs designed to drive faith-based academic–community social innovation. Finally, we share some of our projects that are in progress in North Carolina and Tidewater, Virginia.

Scholars are keenly aware of a need for new ways to understand, study and address complex social, cultural and historical problems that prevent human flourishing and thriving communities. Thus, according to Wright et al. (2011, p. 1), quoting Minkler & Wallerstein (2008), ‘in recent years [… there are] increasing demands for research and program implementation that is community-based, rather than merely community placed.’

Also, according to Wright et al. (2011, p. 1), ‘In the United States, community-based participatory research (CBPR), with its emphasis on the creation and use of community-university or community-academic partnerships, is the prevailing paradigm to address complex community challenges’. Scholars generally define CBPR as a ‘collaborative partnership approach to research that involves community members, organisational representatives and [academic] researchers in all aspects of the research process’ (Ahmed et al. 2001, p. 141). One approach to CBPR, coined by Chen, Jones & Gelber (2006), is community-academic partnered participatory research (CPPR).

We expand this concept to advance ‘faith-based community-academic partnered participatory research’ (FB-CPPR), by asking, ‘How might a faith-based community-academic partnered participatory research team motivated through teaching, training and learning be deployed to address complex social barriers to thriving in their local context, and thereby seek opportunities for positive social change? Moreover, what are potential social impact projects that might spring from faith-based community-academic partnered participatory research teams? Lastly, how might the collaboration partners implement the projects together?

Background

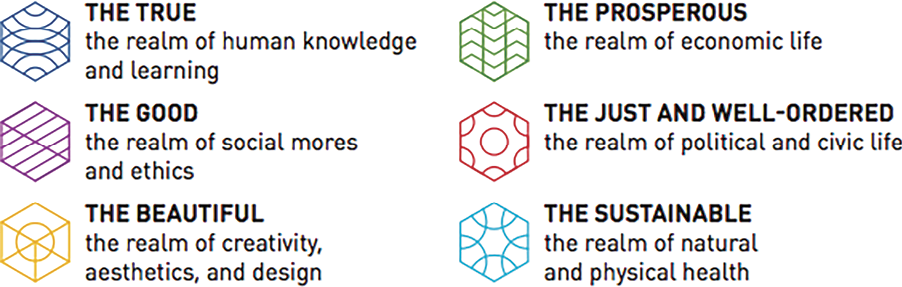

Our FB-CPPR work integrates the Human Ecology Framework advanced by The Thriving Cities Lab at the University of Virginia’s Institute for Advanced Studies, which became the Thriving Cities Group, into faith-based, community-level social change conversations. This Human Ecology Framework provides a lens through which to view societal issues, places and assets as interconnected and related to the wellbeing of people. Specifically, in explaining their framework, they offer:

The human ecologies of an area contain and depend upon an array of different, but fundamental endowments. The first three of the six endowments build on the classical ideals of The True, The Good, and The Beautiful; the last three are more modern ideals of The Prosperous, The Just and Well-Ordered, and The Sustainable. The Human Ecology Framework is a tool for understanding and assessing urban thriving for the 21st century (The Thriving Cities Group).

These referenced ‘endowments’ are depicted in Figure 3. As happens with the term ‘asset’, the word ‘endowment’ is often used in financial sectors and is more commonly associated with resources, usefulness, or a thing of value.

Figure 3. The Human Ecology Framework

Source: Thriving Cities Group

Understanding the nature of community-level endowments could suggest a pathway forward for impactful social change where needed. For example, ‘The True’ endowment assesses the realm of knowledge and knowing, which entails educational institutions (schools, colleges, universities, etc.); bookstores and libraries; a community’s general level of education (and who has education and who does not); what propositions are taken for granted in a community vs. those that are challenged; which knowledge sources are considered reliable, and which are not, etc.

An application question for The True endowment is, ‘What might the impact on asset-based community development be in the long run if a faith-based community re-purposed their place of worship to become a place that lovingly cultivates learning, especially among children in families experiencing intergenerational poverty, who may need a little extra love and support?’ For example, this could be accomplished by a place of worship becoming an after school and summer tutoring partner that helps children who experience educational and social and emotional learning gaps. Adding perspective to this question and idea, Amy L Sherman (2022, p. 102) says, ‘Today, too many precious young minds are not being lovingly cultivated.’ This suggestion about the power of love in the process of cultivating learning speaks to us because the concept of love is fundamental to faith-based organisations. Including the concept of love amid addressing intergenerational poverty is confirmed by Harvard professor Jack P. Shonkoff, MD (2019), whose research is at the forefront of intergenerational poverty. He adds, ‘When we ask anybody’s grandmother about what you need, it’s just somebody to love you’. And, he adds, ‘What science says is you need someone who will create an environment that’s well-regulated and protective and predictable [; and the impact is that] kids are developing and thriving’ (Shonkoff, Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University). Importantly, linking social disparities of health and development to community development, Shonkoff (2021 p. 125) also advocates community-level place-based interventions.

We agree with Ahmed et al. (2001 p. 142) when they write, ‘Communities and academic institutions must desire and learn how to work together.’ Our goal is to transform theological and missional aspects of complex social issues, such as education inequity or inequality, learning gaps, food insecurity, poverty, homelessness, oppression, mental health, climate change, marginalisation, and many other barriers to thriving, by teaching, training and learning the practical aspects of addressing these issues alongside faith-based communities. To accomplish this goal TOC modified the ‘Community Craft’ (CC) curriculum, which is based on the University of Virginia’s Human Ecology Framework, for use by churches and community partners. Dr Joshua J. Yates first taught this curriculum in the Master of Divinity (MDiv) and Doctor of Ministry (DMin) programs at DDS in 2020. In addition to the classroom version, Dr Yates beta tested the concept with a graduate student in an independent study of a local North Carolina community. In all cases, the curriculum was modified for utility in the divinity context by integrating a more faith-informed expression of the concept.

MDiv and DMin participants begin their curriculum journey by considering their own social location, history, and congregational and community assets. The curriculum requires students to do further research to fully understand the interconnectivity of community assets and how they are being deployed by community people and institutions in the communities that they share. Thus, participants continue their learning journey, conducting investigations into census data, community asset-mapping and ground-truthing through qualitative research, such as focus groups and interviews, among those who live and serve in the community.

The quality of some of the student projects suggested a potential for deploying FB-CPPR teams in local communities to address barriers to thriving. The question then became, ‘How do we move this curriculum strategy for asset-based community development from the classroom (among scholars who pay for an MDiv and DMin education) to the community to achieve social intervention among faith-based community people who are not all interested in the rigour of academia and do not have resources or time to attend universities?’

Methodology

Before moving the semester-long curriculum from the academic classroom to the community for free consumption, we needed to shorten the curriculum. In addition, the academy and our faith-based partners needed more relationship building, community information sharing, and mutual teaching, training and learning. Therefore, a process of mutual dialogue and information exchange was developed to undergird potential future faith-based community-academic partnerships.

First, we conducted listen and learn focus groups to intentionally generate dialogue about a common social issue among established DDS/TOC faith-based community partners. Choosing a social concern important to established partners helped to facilitate dialogue about solutions for a mutually significant and contextually relevant barrier to thriving.

Second, we conducted a five-month speaker series of lectures on topics that surfaced from the listen and learn focus group, alternating speakers between faith-based community leaders and university-based academic divinity scholars as the content experts. The goal of the series was to offer learners theological foundations, practical tools, stories of transformation, and to highlight skill sets that fostered a commitment to addressing factors that hindered community thriving.

Third, we reduced the 17-week semester long graduate course to six weeks and three days, and piloted it for utility in faith-based community-academic partnered participatory research among participants in two regional markets. At present, TOC continues to test iterations of the community-level course, which is modified through a process of continuous improvement, participant feedback and TOC’s observations in various local contexts of interest.

During their onboarding process, all participants are informed that the CCC is a pilot program and are given opportunities (written and verbal) to provide written consent to TOC at DDS to use media/information (video, website, publications) about them and share learnings, in whole or in part on any communications and materials related to TOC’s/DDS’ mission(s). The materials in this article, including church names, videos, images and online links, have been vetted by participants, and some have been included in e-newsletters sent directly to participants. All information collected and shared is for teaching, training and learning, not for commercial gain.

The findings and results from this sequential methodology are discussed in detail below. Then, the asset-based Christian social innovations that were generated among the two regional cohorts are presented. We end with our walk alongside strategy that helps to ensure asset-based community development implementation, which we call a ‘Pathways Towards Impact’ process.

Findings and Results

Curriculum Pre-Launch Insights

TOC convened a ‘listen and learn’ focus group lunch to hear the immediate needs and concerns of local faith leaders who were serving in minority communities that have a history of social disparities. The goal was to listen to and learn from pastors and congregations in the communities that we share for ways the Academy might best come alongside and mutually support community thriving. Pastors or ministry leaders of seventeen African American congregations, with established relationships within the local Durham community, as well as the Office of Black Church Studies at DDS, were invited to participate in the focus group. Fourteen of the invited leaders (6 female, 8 male) accepted the invitation. Since the group was convened during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevailing topic of conversation was the impact of the pandemic on the lives of minority communities. The focus group session was entitled: Pressing Our Way through COVID-19: Catalyzing, Curating, and Convening Mindsets, Toolsets, Skillsets, and Soul-sets.

The question that best summarised group-consensus at the end was: How do we help our congregations grieve the loss of what was, and still move forward with joyful anticipation of what can be? Additionally, five major themes were identified and used to inform the creation of a five-month speaker series to enhance respect for mutual teaching, training and learning between the community and the Academy.

Next, qualitative data and insights that were acquired from the focus group survey, as well as formal/informal conversations among congregational and university leaders who participated in the focus group, led to a five-month virtual speaker series taught by local community subject-matter experts and Divinity School faculty subject-matter experts. The series focused on the perceived most urgent COVID-19 related challenges within African American congregations and communities.

Tailored for the faith-based community and academic partners, the topics and speakers were: (1) For Such a Time as This (Rev. Dr David E Goatley, then associate Dean of Academics and Director of Black Church Studies at DDS, now president of Fuller Theological Seminary); (2) Buildings and Communities (Rev. Dr Patrick Duggan, church-owned real estate finance and development expert); (3) Asset Stewardship and Sustainability (Rev. Dr Donna Coletrane Battle, practitioner who focuses on justice and holistic wellness at the intersection of race, gender and spirituality); (4) Reshaping Leadership (Rev. Dr Herbert R Davis, founder and senior pastor of a local Durham church); and (5) Recalibrating Worship (Rev. Dr Luke Powery, Dean of the Chapel at Duke University). Again, the goal of the series was to offer learners theological foundations, practical tools and stories of transformation, and highlight skillsets that fostered a commitment to community thriving.

A website was created by Duke Learning Innovation to house the speaker series: Pressing Our Way Through COVID-19 – With Skillsets, Toolsets, Mindsets, and Soulsets (duke.edu). Sessions were attended by at least fourteen local congregations, representing six denominations, and included participants from congregations as far away as Canada. A follow-up survey reported overwhelmingly positive feedback. Many respondents expressed gratitude, stating that they felt ‘encouraged, invigorated, and equipped’ to adapt their ministries to achieve positive social impact. This sentiment was captured by one survey respondent who said: ‘My “aha” from the series is that the Bible already has a plan of what Durham has to do to become better, but when we come together to learn about who we are, where we are going, and what resources we have, we can better know the possibilities of where we can go.’

Learnings from the focus group and lecture series offered insight to launching a faith-based community academic partnership, using the community craft curriculum originally developed for MDiv and DMin and students. The redesigned course for the faith-based community and their partners was named the Community Craft Collaborative (CCC). Faith community relationship partners who attended the focus group and/or the lecture series were the first to be offered the course. The underlying aim of the pre-launch was to funnel congregations into the CCC program as a ‘next step’ once the speaker series had ended. Two pilot launches of the continuously developing Asset-Development for Social Change Curriculum will be discussed next.

Curriculum Launch Insights

Participants in the focus groups and lecture series communicated a desire to maintain this emerging community-university learning partnership. They wanted ‘next step opportunities’ that provided ‘further resources’, ‘hands-on training’ and ‘practical processes’ that would assist them in crafting innovative solutions to complex local social and emotional challenges in their community. TOC listened and learned.

As a result of communal listening and learning, the cohort-based learning journey program, titled The Community Craft Collaborative (CCC), was developed over an eight-month period to fit the unique context of faith-based academic-community partnerships. The primary goal of the learning journey was to offer high-impact training using an asset-based curriculum that was substantially shorter than its university-driven, semester-long counterpart. Other important goals were peer-to-peer learning and development of an interdisciplinary toolkit and a research-based theological framework. The underlying objective was to help congregations and academic partners journey together towards faith-inspired imagination and faith-informed action, ultimately fostering innovative social improvement and community economic development. To increase the value of the experience to participants, TOC offered the course with a continuing education unit (CEU) credit option and a stipend towards implementation.

TOC embodied a shared leadership model throughout various stages of the CCC program’s planning and implementation phases. For example, TOC partnered with Durham Cares, a Durham-based nonprofit which utilises a holistic and community-driven approach modelled on the eight key components of Christian Community Development to create initiatives for collaboration and teach principles that foster healthy community engagement. Durham Cares staff and cohort participants were invited (at various stages) to assist with planning logistics, co-convene the cohort, review the curriculum and advise on key decisions that would inform program outcomes. Furthermore, collaborative recruitment efforts for the beta cohort leveraged TOC’s pre-existing relationships (interpersonal and professional) within the local Durham/Chapel Hill community. Newly cultivated relationships from the pre-launch phase, and the relational capital housed within the Office of External Relations at DDS were also leveraged.

While nine local congregations expressed serious interest and perceived readiness, six community-based congregational learning teams joined the first CCC cohort, which was launched during November of 2022. These six faith-based communities included thirty-five participants, representing six denominations within the Durham/Chapel Hill North Carolina region. The six congregations were (1) Chapel Hill Bible Church (non-denominational, predominantly white); (2) City Well United Methodist Church (predominantly white); (3) Cole Mill Rd. Church of Christ (predominantly white); (4) Mt. Level Missionary Baptist Church (predominantly black); (5) Nehemiah Church of God in Christ (predominantly black) and (6) Wings of Eagles Christian Church (non-denominational, predominantly black).

Pre/post surveys were administered in-person to the thirty-five participants during the cohort’s opening and closing events to gauge participants’ learning in four primary competency areas, which were grouped as (1) mindsets: adaptive to context and continually changing to meet the challenges of complex conditions, and growth in possibility, flexibility in approach and willingness to change one’s mind based on new perceptual and experiential information; (2) skillsets: knowing how to do something. We needed to be able to put our mindset to work, including understanding how to create, design, construct, implement and learn from experience; (3) toolsets: what mechanisms did we need to be able to reach our goal/objectives? While participants built up their toolset, they also needed to develop the skill of discernment so that they [might] choose the correct tool for the job; (4) soul sets: the theological foundations and Black Church traditions upon which this work is built (past, present and future). A virtual focus group and formal/informal interviews were used to evaluate the program and its methodology, as well as collect suggestions for design improvements and future learning opportunities. The participant feedback (video) added insight to the effectiveness of the curriculum.

The second CCC pilot cohort was launched in the Tidewater region of Virginia in April 2023. The launch followed four months of data analysis and faith-based community-academic collaboration, which led to program and curricular updates, as well as to the design of additional resources used to enhance participant learning outcomes. While a wealth of insight emerged from these learnings, three outcomes were most notable: (1) the Community Craft Collaborative website was redesigned to offer current and potential participants enhanced clarity on CCC’s purpose, methods and anticipated outcomes; (2) a participant workbook was created to offer participants increased accessibility to training material; and (3) the curriculum was updated to further amplify the theological connections.

Again, leveraging pre-existing interpersonal and professional community relationships, TOC partnered strategically with the Co-Presidents (Rev. Dr Veronica R Coleman and Rev. Dr Melvin T Blackwell) of the Metro Ministers’ Conference of Virginia (MMCV), formerly the Historical Tidewater Metro Baptist Ministers’ Conference of Virginia, in its Virginia-based recruitment efforts. The MMCV has approximately 125 members who serve at 50 historically black churches in the Hampton Roads area. The Virginia included five community-based congregational learning teams, totalling 35 participants, representing three denominations within the Hampton Roads region of Virginia. The congregations were (1) Mt Pleasant Baptist Church (Norfolk); (2) Rehoboth Baptist Church (Seatack); (3) New Light Full Gospel Church (Virginia Beach); (4) First Baptist Bute St. (Norfolk) and (5) New Jerusalem Ministries (Kempsville, non-denominational).

As with the first pilot test, pre-post surveys (in person) and formal/informal interviews were used to evaluate the program and its methodology, as well as to collect suggestions for design improvements and future learning opportunities (these results are still under review). However, a newly designed virtual feedback survey was piloted to enhance TOC’s insights on participants’ attitudes towards the human ecology framework, as well as the hybrid peer-learning method. Examples of feedback from this survey are shown below.

When asked how the human ecology framework training enhanced or diminished their current understanding of ‘cultivating community thriving’, one participant responded:

A thriving community must view and include aspects of the 6 Endowments. This in-person and virtual learning experience provided space and time to think about, research, observe, and apply knowledge gained. The Bible is replete with Jesus modeling and explaining His Kingdom in Heaven and on Earth that involves the ‘Good, Prosperous, True, Sustainable, Just & Well-Ordered, and Beautiful! I believe the groundwork that was laid during the in-person training provided a great foundation of the Endowments, our roles in the project, and how it all ties together. As with the process of teaching and learning, what has been taught will be ‘caught’ in future endeavors. Although we applied the knowledge for our pitch, this knowledge is long-lasting; meaning, we will be able to apply it to future experiences and be able to say, ‘hey, here we go again with ‘endowment thinking’.

In response to the same question, another participant wrote:

The in-person explanation of the endowments gave me another method of seeing the community in relation to the world surrounding us. I will revisit the Human Ecology framework on a continuing basis and use it to point young people toward employment positions which they may wish to pursue. Additionally, as Pastor I am constantly looking at the systems behind the problem. I fight constantly with not falling into a sense of hopelessness when we see the causes beneath the surface of so much suffering in our community and the world.

The findings and results from the two regional cohorts support the potential of FB-CPPR to drive asset-based social innovation.

From Idea to Implementation: Pathways Towards Impact

We now share five of the faith-based communities’ ideas pitched during the two pilot studies. All five ideas for asset-based solutions, one from the North Carolina cohort and four from the Virginia cohort, represent promise for meaningful social change. This final step in our faith-based community-academic partnership process is referred to as Ormond’s ‘Pathways Towards Impact’ (PTI) process. The PTI process allows TOC to continue to humbly walk alongside community partners beyond the CCC program, seeking asset-based pathways towards tangible solutions to systemic marginalisation, poverty, oppression and injustice. The idea is to help clergy, congregations and communities to get closer to the asset-based social impact creation finish line.

Cohort 1: North Carolina Case Study

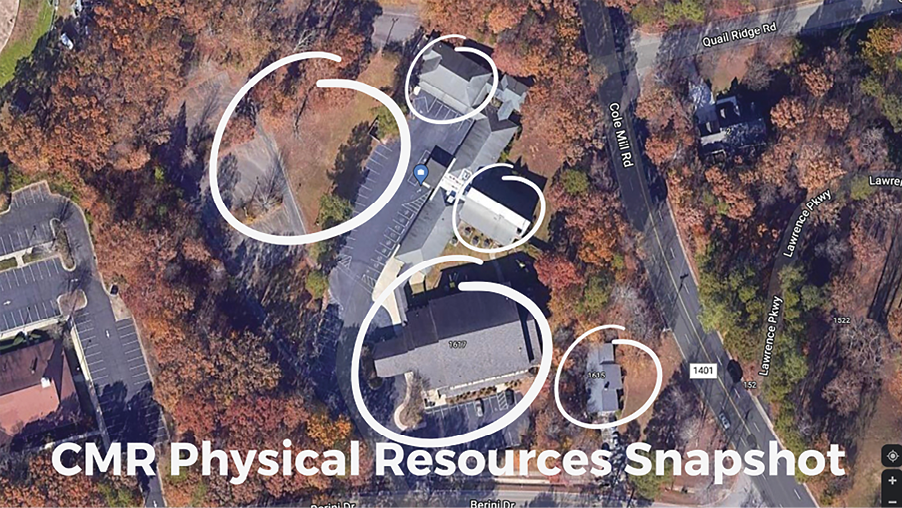

Cole Mill Rd. Church of Christ (CMRCC), Durham, NC joined CCC in November 2022 hoping to gain clarity around their church’s deeply rooted desire to repurpose underutilised property assets and building resources for social good in the local Durham community. TOC uses the term ‘placemaking’ to refer to this type of repurposing of church land and building assets. As defined in TOC’s April e-newsletter:

Placemaking is a process and philosophy adopted primarily from urban landscape designers and architects. Used by this sector since the 70s, placemaking describes the process of re-imagining underutilized public space. Known in some church communities simply as ‘church property redevelopment,’ placemaking has a long history among congregations. Underutilized church property is increasingly in the hands of churches in every North Carolina neighborhood [and neighborhoods across the nation], both rural and urban. This significant asset has the potential to foster thriving while generating economic impact. See Placemaking and Renewed Imagination (campaign-archive.com).

The e-newsletter further explains that ‘CMRCC’s proposal is not just about self-interested economic benefit, but about a life-giving impact to make a place for those who are marginalized’ to live. Because CMRCC’s proposal aligned well with TOC’s mission and vision (About – Ormond Center), TOC invited CMRCC to continue the newly formed FB-CPPR relationship, with a focus on developing an integrative approach to placemaking and asset community development through the Ormond PTI process. CMRCC accepted the invitation (February 2023). Their vision for deploying their underutilised church property assets, shown in Figure 4, is being operationalised for the common good.

An in-depth feasibility study was completed in June 2023 by Wesley Community Development Corporation (Wesley CDC ), a commissioned TOC partner. The study provided a detailed site analysis, a geographic analysis, a space utilisation study and a financial forecasting model. The results offered the critical clarity needed to move forward with continued discernment, congregational visioning and the development of critical next steps towards innovative placemaking in Durham, NC. The next phase will be to facilitate congregational focus groups that will inform CMRCC members of the feasibility study findings, capture feedback and collaboratively discern next steps.

Cohort 2: Four Virginia Case Studies

TOC launched the Tidewater Virginia Community Craft Collaborative program on 1 April, 2023. The closing event was held on 20 May, 2023. Four ideas crafted for social impact creation are shared below.

Congregation 1: New Jerusalem Ministries (NJM), Kempsville, VA

Proposed project: The C.L.U.B (Creative, Learning, Unity, Belonging) Project: Building Pathways to Advancing Equity in Educational Outcomes)

NJM, located in historic Kempsville, is near two elementary schools within the Virginia Beach Public School System. Their proposed project considered community-based research, which highlighted the educational disparities in academic achievement between Black and White students from 2021 to 2022 across all Virginia Beach public schools.

Furthermore, their research found that socio-economic inequities have a profound impact on student academic achievement, mental health and future opportunities for thriving. Additional contributing factors to low student academic achievement included limited access to quality early childhood education, inadequate resources, systemic inequities and the effects of the pandemic on under-resourced families.

When reporting on their findings, participant 1 stated:

Using the ‘ground truthing’ tool, we learned, through various interviews with local educators (active and retired) and public-school administrators, that the Pre-K students needed help with recognizing their alphabets, and that, overall, students needed a sense of belonging … We also learned that addressing these disparities can contribute to a better skilled and educated workforce that is able to attract business and promote economic development (NJM pitch proposal, 2023).

Using the human ecology framework, the NJM team identified an opportunity to: (1) narrow disparities and foster stronger, healthier communities (The Sustainable); (2) increase wisdom and intellect to contribute to more meaningful lives (The True); and (3) encourage positive social mores and ethics (The Good).

At the conclusion of the learning journey, NJM proposed the launch of two after-school clubs: (1) The Mighty As for Pre-K second grade students to focus on improving reading and mathematics skills and (2) The Young Students of Promise Chess Club for grades 3–5 to focus on character building through chess. The clubs will be piloted over a seven-month period and facilitated weekly in ninety-minute sessions. Additionally, NJM plans to host quarterly mentoring and enrichment sessions to bring families together and encourage parental involvement. Identified stakeholders, partners and leadership team members include the NJM Clergy Leadership Team, the NJM Citizens and Volunteers group, a Norfolk State University intern, who will coordinate the program, the Virginia Beach Health Department, the Virginia Beach Cooperative Extension Agency and the Virginia Beach Department of Human Services.

Congregation 2: Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church (MPBC), Norfolk, VA

Proposed project: Seeds of Hope Community Garden

MPBC is a historic pillar in the Titustown community. It is located one block from the Tucker House community, which is a 127-unit senior living facility located on three acres. Tucker House is home to 50–75 residents who regularly attend MPBC worship services and events, and/or receive ministry support from the church (i.e. clothes, food, outings, personal and household items, bill payment). The residents live at or below federal poverty guidelines and face numerous barriers that impact food access and food choice. While discussing the findings of MPBC’s community-based research, participant 2 said:

We noticed that many of our seniors were having to choose between food and basic needs. When we started exploring data about senior care and aging populations, we learned that one of the most vulnerable and under-served populations in the United States of America is the aged or senior population who are 65+ years; specifically, the aged who live in senior or assisted living facilities…We also found that 43% of senior households in Norfolk earn less than $30,000 per year and 25% of people 60 and over receive food stamps (MPBC pitch proposal, 2023).

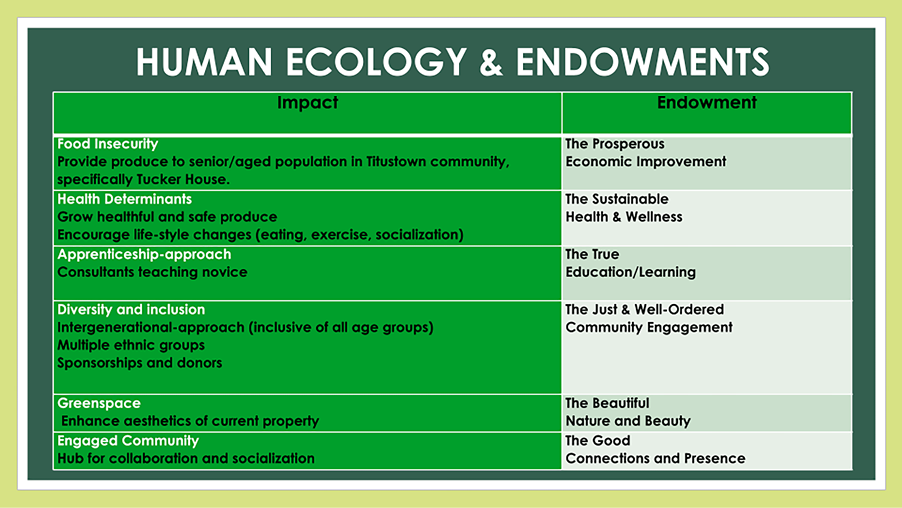

During the CCC learning journey, MPBC identified an opportunity to address food insecurity among the aged and senior population in their local community and, specifically, the Tucker House community. At the conclusion of the learning journey, MPBC proposed the ‘Seeds of Hope Community Garden’ (SHCG). An example of the proposal’s integration with the human ecology framework is shown in Figure 5.

SHCG will be launched in three phases over five months. The anticipated completion date of the first phase is June 2023. Activities include: engaging the congregation, securing major stakeholders, creating a garden design and blueprint, defining roles and responsibilities, establishing a budget and exploring types of vegetation. Identified stakeholders, partners and leadership team members include: The Titustown Civic League (volunteering, advertising and donations), plant/horticulture doctors, scholars and students from Norfolk State University (consultants, expertise, donations and support), the Norfolk Master Gardeners Urban Agriculture Program (consultants, expertise and donations), TOC (financial donation, research, continuing education opportunities) and the MPBC congregation (volunteering, donations and overall support).

Congregation 3: First Baptist Bute Street (FBBS), Norfolk, VA

Proposed project: The Crown Project

FBBS is a historic church, founded in 1800, that currently houses three businesses. Reflecting on FBBS’s motivation for joining the CCC program, participant 3 stated:

Our Church leadership and congregation have been at the forefront of development and support in the City of Norfolk for a long time. Our church has grown over the years, and we want to continue to establish ourselves as leaders and forward thinkers with ministries and businesses…we live in the third-most populous city in Virginia… Norfolk holds a strategic position as the historical, urban, financial, and cultural center of the Hampton Roads region and is the 37th-largest metropolitan area in the United States. (FBBS pitch proposal, 2023).

FBBS used community-based research to highlight rising violence in many heavily populated urban cities, including Norfolk. Their findings reported a 34 percent increase in homicides in 2020, with 90 percent of murder victims being African American. FBBS correlated these statistics with increasing levels of stress and hopelessness brought on by the economic challenges following the pandemic. Participant 4 stated:

Unlike wealthier people, poor people clustered in poor neighborhoods are more likely to have their jobs eliminated or hours cut because of the challenging economic times… Also, neighborhood food pantries and other resources were stretched thin and many places that offered enrichment to children were forced to close or reduce services. All of this has contributed to the rise of hopelessness and violence in our community (FBBS pitch proposal, 2023).

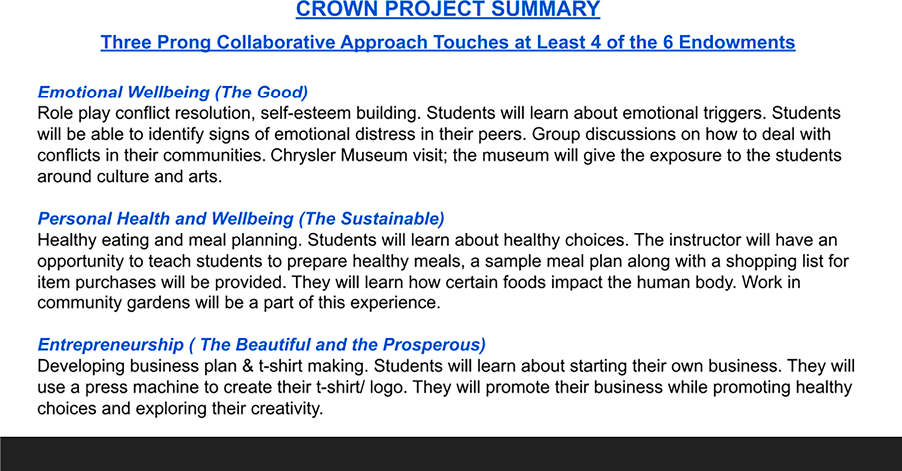

During the CCC learning journey, FBBS identified an opportunity to further explore the connection between anger and low self-esteem amongst youth by using a three-prong approach to address the physical, mental and emotional health of participants as a countermeasure to depression, anger, fear, anxiety, stress and worry. At the conclusion of the learning journey, FBBS proposed ‘The Crown Project’ (TCP), an enrichment program for youth. While available to all youth aged 7–13 who live or attend school in downtown Norfolk, TCP will primarily target those who were adversely affected by the pandemic and who experienced decreased social interaction as well as increased exposure to neighbourhood violence.

TCP will be launched in 2023 and piloted for one year. FBBS will facilitate three eight-week cohorts, each containing thirty youth. Each cohort will offer activities such as interactive instructional sessions, field trips, mentoring opportunities and parent nights. Through collaborative engagement with community-based assets, TCP hopes to cultivate (1) emotional well-being (The Good); (2) personal health and well-being (The Sustainable); and (3) entrepreneurship (The Beautiful and The Prosperous). An example of TCP integration with the human ecology framework is shown in Figure 6.

Reflecting on TCP, participant 3 also stated:

While we see the violence, poor academic performance, and incarceration rates, our solution addresses the underlying (iceberg) beliefs and systemic structures that intentionally or unintentionally contribute to the facts we see and read about on the news and in our media (FBBS, pitch proposal, 2023)

MBBS has identified five subject-matter experts from inside the congregation and two from within the community to fill various program roles.

Congregation 4: Rehoboth Baptist Church, Seatack, VA

Proposed project: Keeping It Real 100

Rehoboth Baptist Church (RBC) is situated in the historic community of Seatack, the oldest settlement on the East Coast of free African Americans and is within 1.5 miles of two low-income apartment housing complexes of approximately 350 families. Using community-based research, the RBC learned that the complexes have a reputation for high poverty rates, drugs, gangs and gun troubles. Upon completing a community-based interview, participant 5 stated:

I learned there is a need for young people to talk to somebody about what appears to me as an unprecedented stress level. It seems to me young people are so stressed out about life decisions, where they fit in, being accepted by peers, and what to do with all of the worldly freedom they have. It makes them feel hopeless to the point of considering harming themselves or others (Ground Truthing Worksheet, 2023).

During the CCC learning journey, RBC identified an opportunity to address the need for intergenerational dialogue, peer support and empathy-based relationship building. Participant 5 stated:

As a Pastor, I have been made aware of two incidents of young adults being so frustrated and confused that they have mentioned to their parents the desire to commit suicide. Another young person within our sphere of influence has expressed the idea of living in two worlds, his church world and his ‘real life’, which Y’all don’t understand.’ And he was right. We don’t understand what it is like to be 16 years old and going to school where anything goes and the world around them is in tumult. As an adult, I struggle sometimes with all of the contention. But as a minor child, who has to depend upon others to care for them, he can’t express everything he is feeling because he thinks we can’t understand (Challenge Response Worksheet, 2023).

A 12-year-old interviewee and community resident stated:

Church is very judgmental … like, if you look some type of way, dress some type of way then they’re not going to accept you and I feel like church should accept everybody no matter what relationship they have with God … because, like, if somebody walks in and you don’t even know who they are, you can’t just judge a book by its cover cause that’s not right cause you don’t know what that person has gone through … and you’re just like, ‘oh, they don’t belong here’ (RBC pitch proposal, 2023).

At the conclusion of the CCC learning journey, RBC proposed Keeping It Real 100 (KIR1), a youth focused social media podcast created to invite and enable young people to discuss their lives, feelings, dreams and disappointments, so that the Church may discern how to expand, alter and/or create new ministries to aid youth in reaching their respective goals. Participant 5 stated, ‘They get to talk; we get to listen and ask, “how can we help”’ (RBC pitch proposal, 2023). KIR1 will: (1) foster two-way learning between youth and adults, community and the church (The True); (2) champion God’s social reality as a way to offer hope to those who feel hopeless (The Good); (3) emphasise the importance of civic engagement and youth leadership (The Just and Well-Ordered); (4) introduce youth to opportunities that cultivate employable skills (The Prosperous); (5) identify and amplify the creativity of local youth (The Beautiful); and (6) provide a positive opportunity for youth to address low self-esteem, hopelessness, and concerns for their futures (RBC pitch proposal, 2023). Participant 5 stated:

By providing the forum for our youth to speak out, we are addressing this problem on the structural level as we look at how we allocate funds, resources, and our time. The mental level of both the church and stakeholders benefit as we get to see what is important in the eyes of teenagers and young adults. In return, the Church has fresh input by which to implement ministries for those who need the church (Challenge Response Worksheet, 2023).

KIR1 will be launched in two phases. The first phase will invite youth to come and talk about ‘their lives and challenges in their way, in their language, and to use social media to reach their peers’ (RBC, pitch proposal, 2023). Phase 2 will invite previous youth participants to co-lead roles (e.g. moderator, producer, production crew, etc.). A mobile component will be incorporated to allow for community-based interviews. Podcast episodes will be hosted on a You Tube channel that will be co-created by the youth-adult leadership team. Participant 5 stated:

We believe the mission of the Church is to share God’s word and salvation with them [youth] but we need to reach them in order to do so … We realize if we are going to ask them to share, participate, and ultimately run this program, we need to make space for what they think is important and what they wish to do, or it [KIR1] will not succeed (RBC pitch proposal, 2023).

Identified stakeholders, partners and leadership team members included four youth participants, four RBC members, a local middle school teacher and two local ministers (one being the CEO of a local production company and the other, a retired professor with valuable podcast experience).

Conclusions and Next Steps

The intentionality and practicality of our theory of change, the organisational framework that we built (based on our theory of change to drive impact creation) and the resulting six projects shared in this study track well with the nine guiding principles of community-based participatory research cited by Wright et al. (2011). These principles resulted from ‘an inclusive review of the literature’ (Wright et al. 2011, p. 84). The cited principles or characteristics are:

(1) recognising community as a unit of identity; (2) facilitating a collaborative, equitable partnership in all phases of the research, involving an empowering and power-sharing process that attends to social inequities; (3) building upon strengths and resources within the community; (4) integrating and achieving balance between knowledge generation and intervention for mutual benefit of all partners; (5) fostering co-learning and capacity-building among all partners; (6) focusing on local relevance [. . .]; (7) disseminating results to all partners and involving them in the dissemination; (8) involving systems development using a cyclical and iterative process; and (9) involving a long-term process and commitment to sustainability (Wright, et al. 2011, p. 85).

In addition to tangible evidence, we introduced the concept of a faith-based factor into the asset-based community-academic participatory research community conversation; and we agreed with Wright et al. (2011, p. 85) when they opined, ‘It is important to note that no one set of principles will be applicable to all partnerships; rather, all partners need collaboratively to decide what their core values and guiding principles will be.’ We see our role in the academy, community and church, or faith-based partnerships we are developing, as that of facilitator, convenor and capacity-building research partner in the triadic network (Figure 7) while the networked partnerships attend to social inequalities or disparities in the communities that we share.

We began this article with questions associated with sustainable and deep impact creation at the community level through FB-CPPR. We explored the questions through a sequential and mutual faith-based/academic-informed process that linked the human ecology framework concept and a graduate curriculum modified for community use. Projects generated by graduate students exposed to the curriculum caused our team to wonder, ‘How do we move this curriculum strategy for asset-based community development from the classroom (among emerging scholars who pay for it) to the community for social change among faith-based community people who may not have the interest in, or resources for, formal university programs?’ We continue to explore this question and implement viable answers through generous grants from The Duke Endowment and the Lilly Foundation.

Initial results and findings suggest that faith-based community-academic partnered participatory research teams can be motivated through a teaching, training and learning process to pursue complex social problems towards positive social change. We introduced here five of the twelve projects that sprung from FB-CPPR teams between November 2022 and April 2023 that show immediate potential. While it is still too early to quantitatively measure the effect of our FB-CPPR on impact creation at the community level of the economy, our qualitative insight and the enthusiasm of the partners in our pilot programs look promising. Consequently, we believe that this type of faith-based academic partnership approach could indeed generate sustainable asset-based community development for positive social change, locally, regionally, nationally and beyond.

Therefore, the Ormond Center at Duke Divinity School will continue to walk alongside these five faith-based partners through its Pathways Towards Impact process, by supplying capability grants, sponsored partnerships and no-cost consulting. At the same time, the lessons learned from participant feedback and team observations during the first two pilot launches of the Community Craft Collaborative continue to improve the evolving curriculum. New launches are also being planned for Western and Eastern North Carolina and South Carolina.

We believe that the lessons learned during this process can be applied to the Academy. For example, the case studies in this FB-CPPR can be used as exemplars in the classroom. The six-week rather than the 17-week semester long model could also be adopted for summer school and emersion type learning initiatives in for-profit and non-profit corporations and organisations.

As has been observed in this work, when faith-based communities and academic institutions collaborate, their shared learning and labours can promote thriving communities. What might happen if congregations everywhere were taught how to connect community-based assets for the good of their neighbours? What might occur if different community anchors within local ecologies – universities and churches – brought their knowledge and assets to partnerships? This article highlights the immense potential of such collaboration, rendering these questions worth asking and solutions worth seeking for a long time to come.

References

Ahmed, S, Beck, B, Maurana, C & Newton, G 2004, ‘Overcoming barriers to effective Community-Based Participatory Research in US Medical Schools’, Education for Health, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 141–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576280410001710969

Chen, D, Jones, L & Gelberg, L 2006, ‘Ethics of clinical research within a Community-Academic Partnered Participatory Framework’, Ethnicity & Disease, vol. 16, Supplement 1: The Community Health Improvement Collaborative: Building community-academic partnerships to reduce disparities, pp. 118–35. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48666978

Community Craft Collaborative 2023, Ormond Center website, viewed 14 June 2023. https://ormondcenter.com/join-the-collaborative

DurhamCares 2017, DurhamCares website, viewed 14 June 2023. https://durhamcares.org/what-is-christian-community-development/

Fitzgerald, S 2009, ‘Cooperative collective action: Framing faith-based community development’, Mobilization, vol. 14, issue 2, pp. 181–98. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.14.2.2vq3x29k57l842q3

Jacobs, J 2011, ‘The kind of problem a city is’, The death and life of great American cities, Modern Library, New York, pp. 558–86.

Jones, L 2016, Christian social innovation: Renewing Wesleyan Witness, Abingdon Press, Nashville, TN, p. 5.

Kresta, D 2021, Jesus on Main Street: Good news through community economic development, Cascade Books, Eugene, OR, p. 9.

Kretzmann, J & McNight, J 1993, Building communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community’s assets, The Asset-Based Community Institute for Policy Research, DePaul University Sterns Center, Chicago, IL, p. 143.

Lilly Foundation Inc., website, viewed 20 July 2023.

Minkler, M & Wallerstein, N 2008, Community-Based Participatory Research for Health, 2nd edn, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 1–23.

National Museum of African American History and Culture, ‘Consecrated Ground: Churches and the founding of America’s historically Black colleges and universities’, 12 October 2023. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/consecrated-ground-churches-and-founding-americas-historically-black-colleges-and universitie

Pressing our way through COVID-19 2021, Duke University site, viewed 14 June 2023. https://sites.duke.edu/pressingourway/

Sherman, A 2022, Pursuing Shalom in every corner of society: Agents of flourishing, Intervarsity Press, Downers Grove, ILL, p. 102.

Shonkoff, JP., MD Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University https://developingchild.harvard.edu/people/jack-shonkoff/; see Annual Review of Public Health Early Childhood Adversity, Toxic Stress, and the Impacts of Racism on the Foundations of Health; see also https://www.empathways.org/news/article/harvard-research-impact-of-poverty-begins-in-the-womb-but-it-doesnt-have-to

Steiner, F 2008, ‘Human ecology: Overview’, in Encyclopedia of Ecology, Academic Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 1898–1906. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008045405-4.00626-1

The Duke endowment website, ‘A private foundation’, viewed 20 July 2023.

‘The human ecology’, The thriving cities group site, viewed 14 June 2023. https://thrivingcitiesgroup.com/our-framework

Tulchinsky, T, Varavikova, E & Cohen, M 2023, ‘Expanding the concept of Public Health’, in The New Public Health, 4th edn, Academic Press, Cambridge MA, pp. 55–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822957-6.00008-9

Wright, K, Williams, P, Wright, S, Lieber, E, Carrasco, S & Gedjeyan, H 2011, ‘Ties that bind: Creating and sustaining Community-Academic Partnerships’, Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, vol. 4, pp. 83–99. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v4i0.1784

Yates, J 2017, ‘The city, the good society and human flourishing’, Yale Values and Human Flourishing Conference, Yale University, New Haven, CT, 26 March.