PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies

Vol. 16, No.2

December 2023

RESEARCH ARTICLE (PEER-REVIEWED)

Front Porch Conversations: Methodological Innovations to Participatory Action Research & Asset-Based Community Development

Josh Brewer1,* and Brandon Kliewer2

1 Executive Director, Manhattan Area Habitat for Humanity; doctoral student, Leadership Communication, Kansas State University

2 Associate Professor of Civic Leadership, Staley School of Leadership Studies, Kansas State University.

Corresponding author: Josh Brewer, jobrewer@ksu.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v16i2.8670

Article History: Received 17/06/2023; Revised 09/11/2023; Accepted 15/11/2023; Published 12/2023

Abstract

Complex public problems are resistant to top-down, technical solutions creating the need for new and innovative ways of approaching community. In response, many practitioners working in community development organisations have embraced community strengths- or asset-based approaches to community development, including Asset Based Community Development (ABCD). Similarly, those scholars committed to social change have started to include action research/learning and participatory approaches to their research design, including Participatory Action Research (PAR). This article describes a qualitative method that was developed by a non-profit practitioner working for a local Habitat for Humanity affiliate and a researcher from a land-grant university in Manhattan, Kansas to operationalise a neighbourhood revitalisation framework with a community conversation series called Front Porch Conversations. The qualitative method developed by the university-nonprofit partnership –called the Front Porch Development Procedure – serves as both a PAR-informed mode of inquiry and an ABCD-informed mode of development. This method provides an example of how university-community partnerships can approach changemaking in novel ways by considering ABCD and PAR approaches.

Keywords

Asset Based Community Development; Participatory Action Research; Action Learning; Leadership as Practice; Neighbourhood Revitalisation; Habitat for Humanity, International

Introduction

A neighbourhood is a network of spatially bound social relationships between people – neighbours – who live and feel close to one another. A neighbourhood may also represent a community of individuals who feel a sense of belonging within a social group, but those neighbours likely belong to multiple communities, including faith communities, workplace communities, political groups, etc. that transcend neighbourhoods. In addition to social closeness, a neighbourhood also represents a space which contains disharmonious relationships. For these reasons, this article will consider the neighbourhood as a socio-material frame and refer to community when discussing the broader publics which are represented by individuals within a neighbourhood. We, the authors of this article, begin with this frame because we are interested in the ways emancipatory change emerges from within neighbourhoods and the evolving relationships of which they are constituted. This interest is related to our work as a nonprofit practitioner and a scholar of civic engagement, and our commitments to advancing change in ways that are transformational, reciprocal and mutually beneficial to our organisations and the unique neighbourhoods in which we live and work.

In this article, we introduce a dialogic procedure that we developed to facilitate strengths-based, grassroots community conversations, which represent a community-driven mode of inquiry and development. We approach this work as community members committed to social change, as professionals who work to recognise knowledge, and as neighbours who would like to see our neighbourhood provide all our neighbours with the opportunity for a high quality of life.

Our work recognises the lived experience of low-to-moderate income neighbours who have experienced waves of disruption, including public disinvestment, privatisation, gentrification, inconsistent policing and displacement over the past several decades in American neighbourhoods (Desmond 2023). Our contemporary phase of disruption largely began in the 1970s when white opposition to desegregation policies emboldened politicians to reorient the benefit of public welfare policies from support for pathways out of poverty, such as public housing and education, and support for labour, such as a stable minimum wage and union protections, to focus on the maintenance of wealth (Desmond 2023). The policy change has been effective, as inequality in income and wealth has soared, while middleclass progress erodes and lower working-class ambitions stagnate (Horowitz, Igielnik & Kochhar 2020). For those neighbours living in disrupted and disinvested neighbourhoods, this reality is experienced as a series of challenges that defy technical solutions despite the clear need for change, and, at times, resources to advance change. Nevertheless, these neighbours and their neighbourhoods persist as long as neighbours can rely on their network of relationships to struggle with these challenges and improve their shared quality of life.

Whenever possible, our conversations take place on front porches to recognise the cultural role of front porches as a space of civility and fellowship, and, at times, female and anti-racist resistance, where residents are seen by passers-by and work at becoming neighbours (hooks 2009). The front porch is a liminal space where outside agents, who we will refer to as guests in the neighbourhood, may join neighbours in their efforts to advance change. The liminal space of the front porches creates a container where neighbours can reimagine systems and structures of power (hooks 2009). Liminal spaces, in this case, the front porch, are an in- between space that does not quite exist. As such, the liminal space of front porches invites consideration of what is, what can be, and what ought to be. Neighbours join one another on front porches, breathe life into values and weave together the social fabric of their shared humanity (Carlon 2021). In a practical sense, our facilitated conversation series aims to empower neighbours as they recognise and consider their shared experience, and possibly advance social change.

We represent our institutions as we enter neighbourhoods, and these institutions hold resources and a privileged social position relative to our community. While our relatively small non-profit organisation is based in and governed by the local community, our institution of higher education has access to significantly more resources than the neighbourhoods. Our institution, like others in higher education, has described our work outside the university as service, outreach and, increasingly, community engagement (Weerts & Sandmann 2010). Our university context reflects an increased awareness of our land grant mission, in line with a longstanding call from engagement scholars for the transformation of institutions and practices of higher education, to become more supportive of engaged scholarship (Sandmann, Saltmarsh & O’Meara 2008). We support replacing the unidirectional approach to knowledge transfer from university to community with a mutually beneficial collaboration focused on recognition and development of knowledge (Weerts & Sandmann 2010). We also support a reconsideration of the positionality of neighbourhood-based communities as being on the margins of university-based learning communities, and the incorporation of facilitators from neighbourhood communities to facilitate our conversations (Sousa 2021).

In disrupting the campus-community binary, we applaud the work of non-profit practitioners and engagement scholars who recognise their shared interest in community challenges and build bridges between campuses and surrounding neighbourhoods through boundary spanning (Weerts & Sandmann 2010). Boundary spanning is a complex and diverse set of practices that exist at organisational and individual levels that varies by individuals’ task orientation and their social closeness to university and community settings (Weerts & Sandmann 2010). Boundary spanners, which is how we identify, include practitioners and scholars who approach community challenges with diverse motivations and backgrounds. Regardless of our focus, we often find an interconnected, tangled mess of complexity surrounding even the most straightforward problems in community settings. As boundary spanners from non-profits and public agencies seek public resolution in their work, they bump into others working within academic institutions who are equally curious about the complexities of social issues. These researchers typically represent educational institutions, which have more resources than community-based organisations, and often speak about their work using unfamiliar language and who are detached from the experiences of community members, which heightens distinctions between a researcher’s and the community’s priorities (Tyron & Stoecker 2008). Further, structures within institutions of higher education, such as publication, tenure and promotion, often do not require or even value the social change efforts of the community (Weerts & Sandmann 2010).

The contrast between the priorities of community members and academic institutions is even more pronounced when those working from a needs- or deficit-based research perspective interact with practitioners of asset-based community development (ABCD). Practitioners of ABCD believe that community challenges are best addressed by mobilising existing resources to action, in contrast to those working with traditional social service models, which focus on mobilising outside resources to address community deficits or gaps (Kretzmann & McKnight 1993). In this article, we show the potential for practitioners of ABCD to find common ground with scholars working within the paradigm of participatory action research (PAR) as they believe that knowledge is not created for or on a subject, but alongside a partner in a community context. These scholars recognise the emancipatory purpose of action research and see the participatory turn in the social sciences as an opportunity to understand an issue in a deeper way through involvement in the community context and through iterative interpretation (Schubotz 2020).

We believe that the practices of ABCD and PAR are not only complementary but represent a potential value-add. ABCD, as a mode of development, combined with PAR, as a mode of inquiry, provides a viable strategy for a research agenda for public engaged scholarship (Giles 2016). As a demonstration of that potential, the dialogic procedure described in this article embeds a PAR approach to inquiry in an ABCD development practice. The Front Porch Conversation holds space whereby common assumptions may be explored and new identities may emerge at the individual, group and community levels. The ABCD-PAR relationship is possible due to theoretical and practical commitments to collective meaning making and empowerment. This potential is demonstrated in our development of an event series called Front Porch Conversations, which operates according to an underlying procedure called the Front Porch Development Procedure (FPDP). The FPDP leverages ABCD and PAR to hold space where neighbours can recognise community assets, seek resolution of community challenges and advance change to improve their quality of life.

The objective of this article is to highlight how dialogic procedures like the FPDP can combine elements of PAR and ABCD that cooperatively function as a mode of inquiry and community development. Our experience with FPDP suggests that engagements directed by ABCD- and PAR-informed procedures have the potential to advance change that results in new forms of knowledge and improved community well-being. Our development of the FPDP demonstrates how boundary-spanning scholars, especially practitioners of PAR, may develop research opportunities within ABCD contexts. As a mode of inquiry, we argue that this facilitated conversation series illuminates a potential theoretical convergence between PAR and ABCD that may be further explored by boundary spanners in academic and community-development contexts. To advance this argument, we provide a brief introduction to Habitat for Humanity’s Neighborhood Revitalization program and Quality of Life Framework, Asset Based Community Development and Participatory Action Research before outlining the theoretical framework used to develop the Front Porch Development procedure. We found that this procedure successfully operationalises Habitat for Humanity’s Quality of Life Framework while offering conceptual and methodological approaches that connect PAR to ABCD and to a wider audience of boundary spanning scholars and practitioners. The Front Porch Conversation Series is currently operating. This article is not a case study or an evaluation of the Front Porch Conversation Series, though our perspective is informed by practical experience. In this article, our intention is to focus on the framework and theoretical underpinnings of the FPDP itself. To be clear, the authors of this article wrote and facilitated the FPDP because we are invested in the outcomes of these conversations. We will be successful when our neighbours are successful. In sharing our work, our hope is that the FPDP can motivate similar approaches to neighbourhood empowerment in other communities.

Habitat for Humanity’s Quality-of-Life Framework

Habitat for Humanity, International is a Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) best known for its integrated home construction and mortgage finance operations, which in 2016 topped the Builder 100 as the largest private homebuilder in the United States (Croce 2016). At the same time, Neighborhood Revitalization programming emerged through the organisation’s grassroots structure as local affiliates embraced an ABCD framework called the Neighborhood Revitalization Quality-of-Life Framework to affect change via a Resident Strengths-Based Approach (Habitat for Humanity 2023a). Local Habitat for Humanity affiliates are independent NGOs that oversee construction, mortgages and discount retail lines of business in compliance with Habitat for Humanity policies, under the direction of a local board of directors (Habitat for Humanity 2023b). The Manhattan Area Habitat for Humanity is an intermediate-sized local affiliate which has provided housing services in two counties in northeast Kansas since 1994 (Manhattan Area Habitat for Humanity 2023). Adjacent to Kansas State University, a Midwestern land-grant university, and Fort Riley, a large military base, this affiliate serves a diverse region of rural and urban communities, and works to develop its Neighborhood Revitalization program with the detailed Quality-of-Life framework, Habitat for Humanity International, provided to its affiliates (Manhattan Area Habitat for Humanity 2023). However, in developing Neighborhood Revitalization programming, the affiliate found a gap in moving the theory towards a practice framework capable of implementation.

With the ABCD methodology in mind, this affiliate recognised the opportunity to partner with a unit at Kansas State University committed to forms of community-engaged scholarship and capable of co-developing a place-based process by which citizens could shape community development activities in their neighbourhoods. The resultant dialogic process, called Front Porch Conversations, held expertise-driven institutional knowledge alongside local experiential knowledge of neighbours, demonstrating that university partners could share power with citizens within an ABCD framework when the process was designed with power-sharing in mind.

Front Porch Conversations are organised using a core document called the Front Porch Development Procedure (FPDP), detailed later in this article. The FPDP process is designed in ways that attempt to account for operation of power at multiple levels. First, the FPDP attends to the ‘power within’ the process to identify self in relation to others and systems differently. Next, the FPDP attends to ‘power with’ or the ways that the dialogic process creates conditions to co-create new ways to understand community, leadership and power. Finally, the FPDP attends to ‘power to’ by focusing on the collective agency that helps unleash a range of community-development efforts.

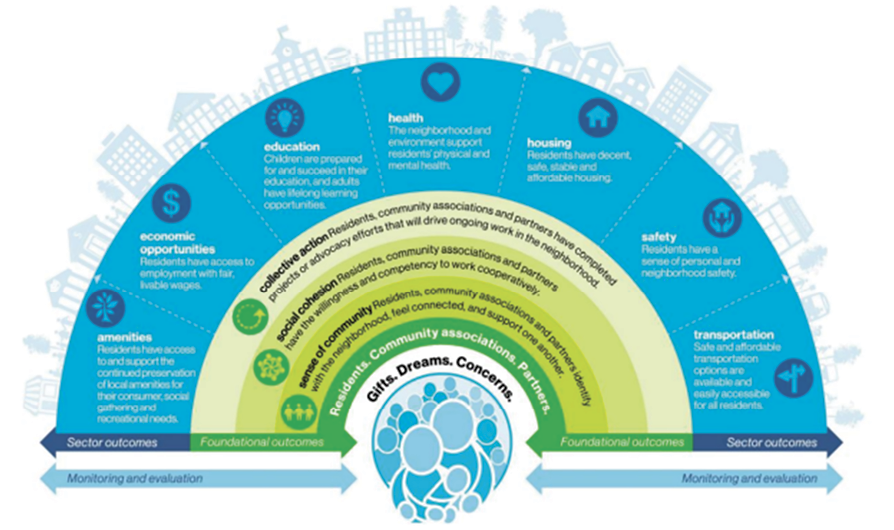

Habitat for Humanity’s Quality of Life Framework presents a holistic approach to neighbourhood revitalisation (Habitat for Humanity 2023a). To effect change, the Quality-of-Life Framework centres the beneficiaries of change efforts and their hopes, dreams and concerns (Habitat for Humanity 2023a). The use of the term beneficiary recognises that cross-sector partnerships between outside agencies and neighbours produce value and centre the beneficiary of that value in line with a critical theory of value creation (Le Ber & Branzei 2010). Including a developed concept of the beneficiary in the FPDP is not inherently inconsistent with our practices of ABCD and PAR, as it recognises that community-based partners benefit from change efforts, while some benefit more than others. Under the Quality-of-Life Framework, the beneficiary of our change efforts is the individual neighbour who effects systemic change through three foundational outcomes:

1. Sense of community: Identifying with the neighbourhood, feeling connected and supporting one another.

2. Social cohesion: Being willing and able to work together.

3. Collective action: Sustaining ongoing projects and advocacy efforts (Habitat for Humanity 2023a).

Once change is reflected in these foundational outcomes, the Quality-of-Life Framework posits that sector level outcomes in housing, economic opportunity, safety, transportation, health, education and amenities may be monitored and evaluated (Habitat for Humanity 2023a). In this framework, change is not directed from community deficits, as defined by comparable approaches or expert-driven definitions, but by a community asset, its people, and their perspectives. This participatory and asset-oriented approach is not unique to Habitat’s framework but has been shown to provide space for critical engagement in community issues, within which unique and effective solutions may emerge (Taliep et al. 2020).

ABCD and PAR

Participatory Action Research (PAR) is a liberating mode of inquiry that moves practitioners beyond the binary of community change efforts and objective, expertise-driven social science research to empower communities through action and recognition of knowledge claims (Hersted 2019). PAR draws on the work of scholars from the Global South with deep commitments to emancipatory change, including Freire (1970) and Tandon (1988). In these foundational works, an emphasis on participation lessens the distinction between community participants and university researchers as learners (Tandon 1988). As a form of Action Learning (AL), PAR is connected to a broader educational approach that uses group dialogue to ‘generate learning from human interaction during the solution of real-time (not simulated) work on [community] problems’ (Raelin 2006, p. 6). AL has a long tradition of infusing participatory and democratic elements into knowledge creation and problem-solving processes; however, in practice, many activities have prioritised benefit to the university over off-campus communities (Sousa 2021). The narrower concept of Participatory Action Research (PAR), which remains deeply committed to liberation, typically assumes that integrating expertise within participatory processes creates forms of knowledge better suited for real-world challenges than AL or expertise can produce alone.

However, even the best efforts to create community-driven and participatory action learning have not been able to remove or adequately attend to dimensions of power associated with creating and applying new knowledge to address social problems. Power differentials inherently shape how knowledge is created in groups (Christenson 2016; Olesen & Nordentoft 2013; Olesen & Nordentoft 2018; Phillips & Napan 2016). Instead of trying to remove or somehow equalise power differentials, there have been growing efforts to recognise power as an essential element of group dynamics and the knowledge-creation process. By attending to power as a part of the knowledge-creation process, we support forms of ‘co-production’ that strengthen the integrity of collaborative learning and action processes (Nordentoft & Olesen 2018). By using a PAR approach that acknowledges the practice as inherently value- and power-laden, we hope to create learning opportunities embedded within the ABCD framework.

Participatory Action Research is an approach to inquiry and knowledge creation that empowers action. PAR creates new forms of knowledge that can mobilise action and make progress on real-world challenges that confront communities. Therefore, the objective of knowledge creation, in the context of PAR, is to mobilise action. This empowering and action-oriented notion of knowledge aligns with the underlying assumptions of ABCD. Two commitments of ABCD, ‘Nothing About Us, Without Us’ and ‘Everything For Us, By Us’, provide simple guardrails that encourage beneficiaries to participate in change efforts. Within these boundaries, learning focuses on community assets, relationships and networks to release individual, organisational and community capacities for positive change (Kretzmann & McKnight 1993). When combined with PAR, ABCD becomes an effective framework to navigate and account for power dynamics in community and group-processes, to co-produce rich ways of understanding wicked problems and to reach resolution for action. As PAR proposes to increase the capacity of change efforts through insider action research, ABCD provides the framework for raising curiosity about those assets, which may be taken for granted in community conversations. This capacity, referred to as ‘preunderstanding’ is essential for effectively effecting change within a system (Coghlan & Shani 2015). To speak briefly to positionality, ABCD and PAR are deeply political practices and aspire to emancipatory change. However, we must recognise that practitioners have a standpoint from which they engage in community change. This standpoint affects the strategies for leveraging strengths to address community concerns.

Theoretical Framework

Beyond the methodological commitments that structure our practices of inquiry and development, theory represents an essential way of making sense of our experiences in the world. As authors, we recognise that the theoretical commitments that underly the FPDP reflect our values, positionality and limited set of experiences; and, we acknowledge that those commitments influence and limit the potential community and scholarly outcomes of the broader Front Porch Conversation series. It is only fair to make these commitments explicit, and so we provide here a brief orientation to the theoretical framework that influenced our composition of the FPDP. The FPDP was developed with clear theoretical commitments regarding the nature of reality, or ontology, and the nature of knowledge, or epistemology.

The FPDP follows a relativist ontological tradition that rejects the Cartesian distinction between subject and object inherent in ontological realism, recognising that reality cannot be separated from human practices (Heidegger 2010). Instead, this work recognises intersubjectivity and interconnection as fundamental to reality and focuses on relationships and networks rather than individuals when considering change. Within those relationships, language, space, place and socio-material interactions provide the framework to constitute and reconstitute reality and to socially define knowledge. In this view, meaning is not coded into language for transference, as suggested by the signal-channel-receiver model of communication, but the use of language presupposes meaning through metaphor, diction and syntax. In this view, to know reality is to constitute reality through interpretation, which inevitably imbues it with biases (Gadamer 2013).

Knowledge, in this view, does not reflect an objective truth about physical reality, but reflects the a priori commitments that link us to one another (Gergen 2009). These relationships are co-constitutive in the sense that they are intelligible based on previously agreed-upon norms, while mediating norms through their very constitution. This commitment is at the heart of a social constructionist epistemology, which acknowledges that ‘all reality, as meaningful reality, is socially constructed’ (Crotty 1998, p. 54). This perspective rejects the positivist definition of singular truth, in favour of agreement between networks of people who exist within a cultural and historical context (Dugan 2017). For this reason, the social constructionist perspective of the FPDP is less interested in what is true or false and more curious about who benefits from a particular way of knowing and the effect of discourse on socio-material relations (Barrett 2015). This recognises that our agreed-upon norms are value-laden, and for that reason often reflect and reproduce power differentials. This recognition orients the FPDP towards the tradition of critical theory, which aims to reveal power structures through reflective practices, often referred to as critical reflexivity (Dugan 2017).

Finally, the composition of and participation with the FPDP is a practice of leadership, which our theoretical framework considers an emancipatory practice by which we attend to the exigencies of our time by reshaping socio-cultural norms (Dugan 2017). Our perspective recognises that the practice of leadership takes place within Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS), which are experienced relationally. CAS is a group of semi-autonomous agents or groups that interact in ways that produce system-wide patterns, which loop back and influence future interactions (Dooley 1997; Eoyang and Holladay 2013; Lichtenstein 2014). Taking systems of power into account, this work recognises knowledge emerging from leaderful community practices (Raelin 2011). Leadership as Practice (LAP) is foundational to this framework because it moves the focus of research from the individual to the processes, practices and socio-material interactions of community-based work. This approach follows a definition of leadership as a ‘socio-spatial process of accomplishing direction’ (Alvehas & Crevani 2022, p. 232). By studying leadership as practice, this framework moves beyond a competency-based paradigm towards a practice-based paradigm where activity happens and from which knowing emerges within community contexts (Carroll et al. 2008). By approaching leadership as something that emerges from our experience with social and material elements of places, scholars and practitioners have a powerful lens through which to understand and create leaderful spaces.

In this view, leadership is embodied in socio-material spaces and is experienced through interactions with physical materials and social norms (Ropo, Sauer & Salovaara 2013). This experience is made meaningful by emotions, but also the memories of previous experiences, referred to as a ‘backward reflexivity’ (Ropo, Sauer & Salovaara 2013). These spaces are not inert; rather, they reflect and constitute dominant power relations, allowing critical researchers additional data for understanding hegemonic pressures and practitioners’, and new experiments for creating power-with (Ropo & Salovaara 2018). The lens of socio-materiality also affects this work as it explores how leadership practitioners leverage liminal spaces to create democratic experiences that challenge the dominant structure. The evolution from dominant spaces to liminal spaces allows us to better understand and leverage the socio-material to affect power relations.

The experience of equality, or ‘communitas’, is considered a fundamental basis of organisation and cooperation in changing structural norms (Turner 1969). Focusing on these spaces, Poyhonen (2018) writes in ‘Room for Communitas’:

This rich opportunity for temporal, out-of-norm behavior makes these spaces home for anti-structural thinking and action; it is within these organizational spaces that the experiences of liminality and communitas most easily arise, especially within a hierarchical organization ... The experience of communitas, then, especially plays into construction of more plural forms of leadership, as it unmasks the equal human beings behind their formal ranks and the rules their normal social structure entails

(Poyhonen 2018, p. 596).

Following a leadership as practice approach, the FPDP is an example of activist scholarship which explores liminal threshold spaces with a focus on out-of-norm behavior, that create opportunities for rewriting dominant power relations. This explicitly critical, discursive approach to cultivating a leaderful practice recognises language as a lively, non-fixed element embodied with Foucauldian power as Discourse, which reflects and actively constitutes reality through its performative impact (Ford 2015). This work embraces dialectical tension to explore gaps and exploit contradictions (Collinson 2019). This work also moves beyond the inheritance of heroic leadership thinking to embrace a collective leadership model that embraces outsider perspectives (Ospina 2019).

Such a shift toward a critical leaderful practice full of lively language has implications for both practice and research. In both applications, it is worthwhile to remember that a critical approach to leadership is emancipatory. We work toward the reduction of injustice in the world. We work to build power with one another, especially with those who are excluded from decision-making processes. Such a commitment is appropriately called critical hope, a recognition of the realities of injustice and oppression that also affirms resilience and sets direction for moving forward (Dugan 2017, p. 51). This perspective leads us to embrace new ways of knowing, of non-standard traditions of sharing knowledge, such as storytelling, and outsider perspectives in capturing a more holistic view of community challenges. When taken together, this critical approach to knowing through leaderful practice has the potential to engage scholars in community work, add capacity and creativity to practitioner efforts, and build desperately needed hope in an unjust world.

Critical leaderful practice is made possible by combining ABCD and PAR, which creates a community-engaged methodology that co-creates a mode of inquiry and a mode of community development. These complementary practices are the result of deep collaboration between activist academics who seek emancipatory change through their research activities and community practitioners who lead change efforts in community settings. Together, ABCD and PAR efforts can surface novel ways of knowing by inviting non-dominant perspectives while leveraging the capacity of institutional assets. For this emancipatory potential to be realised, practitioners of ABCD and PAR should be conscious of their critical project and reflective on the success of their interventions. With theoretical consciousness and reflexivity, practitioners can co-develop purposeful practices with community that create conditions for social change to emerge. The Front Porch Development Procedure is one process that creates conditions for emancipatory change to emerge.

Front Porch Development Procedure

The Front Porch Development Procedure (FPDP) described in this article combines commitments to PAR and ABCD to allow for new knowledge on neighbourhood dynamics, while simultaneously increasing neighbourhood capacity for leadership and community development. The FPDP structures a hyper-local event called a Front Porch Conversation, which seeks to operationalise Habitat for Humanity’s Quality of Life Index.

Four roles will be described in this section: a community-based convener, a trained facilitator, a notetaker, and a steward who is a boundary spanning practitioner of ABCD and/or PAR. As a mode of inquiry and development, the FPDP recognises under-leveraged community assets necessary to advance neighbourhood revitalisation, such as schools, parks, key relationships, or stories, leading to new ways of knowing and being in the community.

FPDP Roles

The FPDP begins with a steward who is either a practitioner of ABCD or PAR and has a boundary spanning role. The steward is responsible for ensuring that the Front Porch Conversation engagement remains mutually beneficial and true to its theoretical commitments. The steward is also responsible for promoting the conversation series to residents through local networks, such as neighbourhood associations and common spaces, such as community centres and churches. When a resident first signals interest to host a community conversation, the steward meets with them to provide an overview of the FPDP and to share promotional materials, including a yard sign and flyers describing the Quality-of-Life Framework, which is based on ABCD principles. As a representative of an institution with power and resources, and potentially educational privileges, the steward should provide the resident with a choice to convene the conversation or reduce the social pressure to serve their neighbours in this capacity.

When the resident schedules their conversation, they become a convener. The convener is usually a long-time neighbourhood resident with connections to many of their neighbours. The convener approaches their neighbours in the way they feel is most appropriate, whether by door knocking or electronic communication. When the convener connects with neighbours, they can choose to share the materials that the steward has prepared for them or not. The convener has the choice to organise their Front Porch Conversation around a meal, beverages, or a shared activity. Whichever way the gathering is organised, it is important that the steward empowers the convener to gather their neighbours on their terms. As the convener speaks with neighbours, they share that the purpose of the conversation is to identify community assets, community aspirations and neighbourhood revitalisation interventions, and increase understanding of potential neighbourhood improvements.

Front Porch Conversations are facilitated by an individual who has received training in the FPDP. Facilitator training is an effort to ensure the process is fair, equitable, and can attend to power dynamics that may influence the substance of the dialogic process. During the event, facilitators are responsible for moving through the process and creating conditions that support full participation from the convener and their neighbours. Full participation is an asset-based aspiration that each neighbour will have a meaningful opportunity to contribute ideas and offer perspectives that have the potential to shape the direction of the discussion. The process and facilitation practices represent a commitment to recognise the inherent dignity of each participant. Part of recognising this is to acknowledge that each participant has important knowledge to share individually, and with appropriate support, co-create new knowledge with others (Eoyang & Holladay 2013). Facilitators are trained to solicit input from neighbours who have not shared and to highlight non-dominant perspectives during the Front Porch Conversation. Facilitators are also trained to create ‘holding environments’, which participants can use to make sense and meaning of the conversation on leadership and community development. Facilitator interventions help shift leadership and community development mindsets and support participants to co-construct asset-based mental models capable of revitalising neighbourhoods.

While facilitators create the conditions for this work, notetakers capture key information on large paper tear sheets so that participants can hold onto shared touchpoints as the conversation evolves. The partnership between the notetaker and the facilitator is essential for a successful Front Porch Conversation as both listen for colliding perspectives and highlight key information so that learning may take place. For example, while the facilitator may ask for more to be said about contradictory claims, a notetaker can capture a record of the conversation, including key assets, insights, opportunities and emergent knowledge, for participants. The notes create an emergent artifact that helps participants make sense and create meaning associated with their conversation. Notes may be shared with participants and referenced in follow-up actions and meetings. The exchange between the facilitator and the notetaker, and the actual act of notetaking, are practical means of managing contestation, and visually represent any power dynamics emerging from the conversation.

The FPDP requires only a few supplies to produce notes and artifacts. The essential materials are as follows: The Habitat for Humanity Quality of Life Framework, which is printed on a larger posterboard, and individual sheets, tear sheets, red-, yellow-, and green-dots, and some refreshments. Prior to the exercise, tear sheets should be hung, and dot sheets torn so that each strip includes a red, yellow and green dot.

The following section details how these roles and materials should be used to create an asset-based learning and development environment.

Operational Procedure

When neighbours arrive at a Front Porch Conversation, the convener, steward, facilitator and notetakers should work to quickly create a shared and collective sense of purpose by greeting every person, inviting them to sign into the meeting and identifying themselves using a nametag. Each neighbour will be handed a torn dot sheet and a copy of the Habitat for Humanity Quality of Life Framework. The convener should thank every person by name for attending the meeting and introduce themselves to anyone unfamiliar with it. Once it is time to begin the meeting, the facilitator should introduce themself to the group and ask neighbours to introduce themselves and offer one reason why they were motivated to say ‘yes’ to the meeting. Next, the facilitator should invite the steward to introduce him or herself and the purpose of the gathering. The steward will speak about the mission of the organisation in which they serve and the aims of ABCD and PAR. If multiple stewards are present, they will each speak to their organisational mission and to their background of either ABCD or PAR. The steward will also communicate their definition of leadership as practice and the view that leadership capacity deepens when learners have a space to experience ‘heat’ or be included in stretch conversations, be challenged by perspectives different from their own, and also have space for critical reflection. (Jones Chesley & Terri 2020; Petrie 2015). The steward will ask the neighbours if they have any questions about their motivations for the gathering and answer any questions succinctly if they arise. Finally, the steward will recognise the notetakers’ role in documenting the discussion themes and the facilitator for their work supporting the discussion using the FPDP.

The FPDP calls for the conversation to start with three ground rules: seek full participation, hold space for multiple viewpoints and listen with curiosity. These ground rules should be written on a tear sheet prior to the beginning of the session. The facilitator should note that these ground rules align with the conditions that support leadership and community development. Facilitators will invite participants to contribute additional ground rules to ensure a successful discussion. As neighbours share ground rules, notetakers will record anything that is added. If the group is reticent to share, the facilitator will point to rule number one – seek full participation – to demonstrate how the ground rules will be used in the discussion and to manage interpersonal dynamics.

Introducing the Quality-of-Life Framework

The facilitator will invite the steward to frame the conversation via the HFHQL Framework using a poster detailed in Figure 1. The steward should introduce the Quality-of-Life framework as a way of understanding the community. The steward will begin by describing sector level outcomes – housing, healthcare, neighbourhood amenities, safety, etc. – pointing out how much community-level discussion focuses on these topics as if they were disconnected from one another. The steward will then recognise how sector outcomes, such as housing, are the result of decisions by experts, policy makers and community members, and the complex community context that surrounds the sector. The steward will highlight how the sector outcomes experienced by the community today are the result of agreements among neighbours over generations and are always changing with each interaction between neighbours – good and bad – with the acknowledgement that agreements exist within the context of economic or political structures.

Figure 1. Habitat for Humanity Quality of Life Framework

The steward then introduces three foundational outcomes as determinant factors in producing the conditions for sector level outcomes. First, the steward will define the sense of community as the ability for neighbourhood residents to feel connected to one another whether by associations, faith communities, mutual aid networks. The ‘cup of sugar’ rule – that a neighbour may ask another for a cup of sugar or a pat of butter –illustrates this capacity. Next, the steward will define the sense of social cohesion as the willingness for neighbours to work together to address shared challenges. For example, the steward may ask for an example of a time when a problem arose, and ways neighbours banded together in small groups or a large group. Finally, the steward will define the sense of collective action as the shared experience of working together on projects or advocacy efforts to improve the neighbourhood quality of life. Taken together, the steward will explain how these foundational outcomes are recognised as essential to making change in the neighbourhood. The steward then invites neighbours to share any thoughts or questions about foundational outcomes.

Finally, the steward should recognise the neighbours, their community associations and community partners as the core of the quality-of-life framework. Each neighbour brings unique gifts and dreams, but also concerns to the neighbourhood and to the conversation. The steward then explains how these unique gifts are the root of the foundational outcomes and represent the core focus of the facilitated conversation. To conclude, the steward will summarise the framework again from the core outward as the gifts, dreams and concerns of the neighbourhood affect the foundational outcomes which produce the sector level experiences that are often referred to as the quality of life that a person experiences in a neighbourhood. Neighbours are encouraged to explore the Quality-of-Life framework further after the meeting.

The majority of the FPDP, at least 45 minutes, should be dedicated to a dot voting exercise introduced by the facilitator. The facilitator’s role is essential to the FPDP and can be understood within the context of praxis (Raelin 2005). Facilitation in this context should aim to realise the power structures that contextualise neighbourhood dynamics while empowering neighbours to take action through dialogue and as a result of dialogue. Within the conversation, learning is the result of facilitated praxis and is the ultimate responsibility of the facilitator. As a critical exercise, facilitation should create the dialogic conditions for emancipatory action.

To begin, the facilitator will invite each neighbour to look at their dots. The facilitator will explain that yellow dots represent gifts, green dots represent dreams and red dots represent concerns. The facilitator will then direct the notetaker to write each sector-level outcome –housing, healthcare, neighbourhood amenities, safety – on a tear sheet and place it in an accessible place. The facilitator will then explain that where neighbours place their dots will advance the conversation about the type of leadership and community development capacity necessary to make sector-level change. The facilitator should ask if the neighbours have any questions about the exercise, and once the group has clarity, invite the neighbours to place their dots on sector-level outcomes that they see as gifts, dreams and concerns. As neighbours place dots on the tear sheets, facilitators should listen for conversation between neighbours about their dots and look for moments of curiosity or surprise. This interest should guide the facilitator’s attention.

Once all the dots are placed, facilitators will ask neighbours to identify patterns associated with gifts and dreams. For example, a group of green dots may be focused on housing and yellow dots on neighbourhood amenities. In this case, the facilitator would encourage individuals who placed those dots to share more about what that placement represented for them. As neighbours explore assets and dreams, the facilitator should pay particular attention to information that seems novel to some group members and encourage others to engage their curiosity. Once the sharing of dreams and assets begins to slow, the facilitator should ask about patterns associated with red dots or the concerns of the neighbourhood. The facilitator should take special care to maintain the asset-orientation of the discussion and to manage conflict. Where possible, the facilitator should highlight and direct the conversation toward areas of tension between the assets, dreams and concerns. For example, if housing is recognised as a gift, but community safety is seen as a concern, the facilitator may ask if neighbours feel unsafe inside their homes, in their yards, on the footpath or on the road.

When the conversation recognising assets, aspirations and concerns subsides, the facilitator should ask the group to consider how the assets referenced were developed. The facilitator may ask this question broadly or specifically. For example, if tree-lined streets were identified as an asset, the facilitator may ask, ‘Who planted the trees?’ and ‘How did tree planting become a priority?’. In asking these questions, the facilitator should listen for and highlight patterns demonstrating asset leveraging and times where leadership and leadership learning made way for community change. When identified, facilitators should encourage participants to explore how that leveraging or learning came to be, who was involved, and how that may be reproduced in addressing current concerns or to achieve aspirations. In this section of the discussion, the facilitator should feel comfortable with pauses in the conversation as neighbours consider the questions. To ensure full participation, the facilitator may need to ask individual neighbours if they have learning to share with the group. Facilitators and notetakers should aim to leave participants with energy and a shared purpose, necessary for making progress on shared issues, by focusing on the quality of the conversation, as opposed to the quantity of topics covered.

Sense and Meaning Making for Future Action

In the final 10 minutes of the FPDP, the group focus on making sense of new learning and discussing leadership and community development capacity. The space allows participants to make observations on specific ways their leadership and community development capacity increased during the exercise or to highlight areas in which deeper capacity would need to be developed to advance sector level change. To begin, the facilitator may ask a simple question, such as ‘What did we learn tonight?’ or ‘What ways did we grow as a group?’. Once progress has been named, the facilitator will ask the group to identify potential next steps without fully committing to any specific action. The purpose of this question is to increase awareness of community possibilities. The facilitator should listen for moments when neighbours invite one another to join ongoing efforts and highlight areas of shared purpose.

To conclude, the facilitator should thank the group for their participation, the convener for gathering their neighbours, and the notetaker for documenting the work that has been accomplished. The facilitator will then invite the steward to address the group to close the gathering. The steward should begin by thanking the facilitator for their work in advancing the conversation and thanking the neighbours, convener and notetaker once again. The steward should then congratulate the group on areas of significant learning that they heard in the conversation. Finally, the steward should explicitly highlight the potential for Front Porch Conversations to create new knowledge that increases leadership and community development capacity. The steward then concludes the FPDP.

Concluding thoughts

Front Porch Conversations employ the FPDP to create momentary adaptive-discursive spaces to shift neighbourhood thinking from forms of knowledge limited to recognition of deficits requiring outside intervention to emancipatory forms of knowledge that celebrate assets and enable change from the inside out. The FPDP aims to activate what bell hooks calls ‘a democratic meeting place, capable of containing folks from various walks of life, with diverse perspectives’ (hooks 2009, p. 147). With new ways of knowing, neighbours are more likely to consider sector-level challenges that affect their well-being, in the context of their social networks and the relationships within those networks, or their neighbourhood. This partnership found that, by combining PAR and ABCD processes, they were able to more effectively operationalise Habitat for Humanity’s Quality of Life framework to effect change, while situating learning and capacity building within the experiences of community members. Recognising these new forms of knowledge not only empowers neighbours to effect change democratically, but also acknowledges that collective and asset-based forms of leadership and community development will be required to create the type of sector-level change needed to improve community well-being.

Community integration results in significant learning on the nature of knowledge produced within an ABCD-PAR experience. As ABCD is focused on community-driven change from an asset-based approach, its integration with PAR creates a future-oriented learning environment. Knowledge produced in this environment does not only seek to understand an issue in an objective, positivist manner, but must be deeply committed to action and forms of knowledge that increase the capacity of community to act. By combining practices of ABCD and PAR, the FPDP functions as both a mode of inquiry and a mode of leadership learning and development. From a development perspective, PAR creates the potential for more effective solutions to emerge from neighbourhood contexts than may be called for in a more conventional top-down approach. Further, by attending to power within, a PAR practice of inquiry and an ABCD practice of development through co-production, more diverse knowledge forms can be recognised and engaged so that grassroots community change can emerge through relationships within spatially oriented networks, which we have referred to as neighbourhoods. The inquiry process described in this article not only creates new forms of knowledge but does so in a way that builds social connection – identity, efficacy and motivation to collectively address challenges in common. This approach to ABCD-PAR recognises the essential role of agreed-upon or shared knowledge in making progress on community challenges.

Knowledge creation processes consistent with PAR also require full participation and a recognition of the ways knowledge is co-created through shared context and dialogic and relational interaction. When done intentionally, community learning can develop leadership capacity through participation in inclusive practice and processes. As participants move through a facilitated ABCD-PAR exercise, such as the FPDP, each neighbour has the opportunity to collectively join a momentary adaptive container to deepen neighbourhood leadership capacity, i.e. to positively effect change. Each time a Front Porch Conversation occurs using the FPDP, new neighbours have new opportunities to create knowledge in ways unique to the particular collective in the context of their neighbourhood at that time. Changes that follow Front Porch conversations are often small – organising a community clean-up or a collective social event – but continue to develop beyond the conversation and the outside agency that serves as steward. While the outcome may not appear liberating at first glance, each instance represents a small group of individuals who create new forms of knowledge and act collectively – usually for the first time – to improve their own quality of life by leveraging neighbourhood assets.

With a theoretically informed FPDP, the next step for this project is to facilitate more Front Porch Conversations and to document new knowledge that emerges through a community writing project. Front Porch Conversations with a focus on connecting with conveners from our historic Black and disinvested neighbourhoods will take place across our community. Each conversation will continue to focus on co-production of knowledge and recognition of community assets, and will be followed by a writing prompt to be described in future work. This community writing project will produce information on a community asset map to be shared within the community via ArcGIS StoryMaps. This technology will enable community members to highlight assets identified during Front Porch Conversations, in addition to others. Ultimately, it is the hope that, with this knowledge and increased leadership capacity, community change efforts will effectively emerge through the neighbourhood networks to improve community well-being.

This article has laid the foundation for future work by providing a brief overview of the theoretical framework informing the Front Porch Development Protocol (FPDP) that structures Front Porch Conversations. The FPDP serves as one example of how a combined ABCD-PAR approach can produce learning by recognising community strengths and leveraging those strengths to mobilise social, political, economic and moral change. The FPDP also serves as an example of one way to operationalise Neighbourhood Revitalisation models like Habitat for Humanity International’s Quality of Life Framework through dialogic processes. In both cases, our commitment is to move new forms of knowledge towards action to improve community well-being in our neighbourhoods. Above all, we recognise that grassroots change represents iterative community resolution, which is how we may approach wicked problems from a position of strength to build community capacity through participatory learning and action. As neighbours, we are committed to this work as fellowship.

References

Carlon, C 2021, ‘Contesting community development: Grounding definitions in practice Contexts’, Development in practice [Online], vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 323–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2020.1837078

Cooperrider, D & Whitney, D 2005, Appreciative inquiry: A positive revolution in change, 1st edn, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco, CA.

Croce, B 2016, Builder 100: The top 25 private companies, Builder Magazine, Builder. www.builderonline.com/builder-100/builder-100-the-top-25-private-companies

Christensen, G 2015, ‘Power, ethics and the production of subjectivity in the group interview’, International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/18340806.2015.1157846

Coghlan, D & Shani, A 2015, ‘Developing the practice of leading change through insider action research: A dynamic capability perspective’, The SAGE handbook of action research, pp. 167–78.

Desmond, M 2023, Poverty, by America.

Dooley, K 1997, ‘A complex adaptive systems model of organization change’, Nonlinear dynamics, psychology, and life sciences, 1, pp. 69–97. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022375910940

Dugan, J 2017, Leadership theory: Cultivating critical perspectives, John Wiley & Sons.

Eoyang, G & Holladay, R 2013, Adaptive action: Leveraging uncertainty in your organization, Stanford University Press.

Freire, P 1970, Pedagogy of the oppressed, Continuum, New York.

Giles, D 2016, ‘Understanding an emerging field of scholarship: Toward a research agenda for ‘Engaged Public Scholarship’, Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 181–91.

Habitat for Humanity (n.d.), The importance of healthy neighborhoods. https://www.habitat.org/our-work/neighborhood-revitalization/importance-of-healthy-neighborhoods (accessed 30 July 2023).

Habitat for Humanity (n.d.), What are Habitat for Humanity affiliates? www.habitat.org/about/faq#affiliates.

Hersted, L, Ness, O & Frimann, S (eds) 2019, Action research in a relational perspective: Dialogue, reflexivity, power and ethics, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429289408

hooks, b, 2009, Belonging: A culture of place. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203888018

Horowitz, J, Igielnik, R & Kochhar, R 2020, ‘Most Americans say there is too much economic inequality in the US, but fewer than half call it a top priority’, Pew Research Center, 9.

Jones, H, Chesley, J & Egan, T 2020, ‘Helping leaders grow up: Vertical leadership development in practice’, The Journal of Values-Based Leadership, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 8. https://doi.org/10.22543/0733.131.1275

Kretzmann, J & McKnight, J 1993, Building communities from the inside out.

Le Ber, M & Branzei, O 2010, ‘Towards a critical theory of value creation in cross-sector partnerships’, Organization, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 599–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508410372621

Lichtenstein, B 2014, Generative emergence: A new discipline of organizational, entrepreneurial and social innovation, Oxford University Press, USA. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199933594.001.0001

Manhattan Area Habitat for Humanity (n.d.), ‘About Us’ [online], Manhattan Area Habitat for Humanity (mahfh.org).

McKnight, J & Block, P 2011, The abundant community: Awakening the power of families and neighborhoods, Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Olesen, B & Nordentoft, H 2013, ‘Walking the talk?’: A micro-sociological approach to the co-production of knowledge and power in Action Research, International Journal of Action Research, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 67–94.

Olesen, B & Nordentoft, H 2018, ‘On slippery ground – beyond the innocence of collaborative knowledge production’, Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 356–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-09-2017-1562

Petrie, N 2015, ‘The how-to of vertical leadership development: 30 experts, 3 conditions and 15 approaches’, Center for Creative Leadership, vol. 26, Part 2.

Phillips, L & Napan, K 2016, ‘What’s in the ‘co’? Tending the tensions in co-creative inquiry in Social Work education’, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 827–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1162869

Raelin, J 2006, ‘The role of facilitation in praxis’, Organizational Dynamics, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2005.12.008

Rittel, H & Webber, M 1973, ‘Dilemmas in a general theory of planning’, Policy Sciences, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 155–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

Ropo, A, Sauer, E & Salovaara, P 2013, ‘Embodiment of leadership through material place’, Leadership, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 378–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715013485858

Sandmann, L, Saltmarsh, J & O’Meara, K 2008, ‘An integrated model for advancing the scholarship of engagement: Creating academic homes for the engaged scholar’, Building the field of Higher Education Engagement, Routledge.

Schubotz, D 2019, Participatory research: Why and how to involve people in research, Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529799682

Sousa, J 2021, ‘Community members as facilitators: Reclaiming community-based research as inherently of the people’, Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v14i2.7767

Tandon, R 1988, ‘Social transformation and Participatory Research’, Convergence (Toronto), vol. 21, no. 2, p. 5.

Taliep, N, Lazarus, S, Cochrane, J, Olivier, J, Bulbulia, S, Seedat, M, Swanepoel, H & James, A.M. 2023, ‘Community asset mapping as an action research strategy for developing an interpersonal violence prevention programme in South Africa’, Action research, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 175–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750319898236

Tryon, E & Stoecker, R 2008, ‘The unheard voices: Community organizations and service-learning’, Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 47–60.

Weerts, D & Sandmann, L 2010, ‘Community engagement and boundary-spanning roles at research universities’, The Journal of Higher Education, vol. 81, no. 6, pp. 632–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2010.11779075