Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 15, No. 2

December 2022

Research article (peer reviewed)

Youth Visions in a Changing Climate: Emerging Lessons from Using Immersive and Arts-Based Methods for Strengthening Community-Engaged Research with Urban Youth

Nadia Sitas1,*, Odirilwe Selomane1, Ffion Atkins2,3, CareCreative4,5, DFeat once4, Urban Khoi Soldier4, Mac14, Elona Hlongwane5, Sandile Fanana5, Theresa Wigley5, Teresa Boulle5

1 Centre for Sustainability Transitions, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

2 African Climate and Development Initiative, University of Cape Town, South Africa

3 The Beach Coop

4 Handcantrol360

5 Amava Oluntu

Corresponding author: Nadia Sitas, nadiasitas@sun.ac.za

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v15i2.8318

Article History: Received 14/08/2022; Revised 19/09/2022; Accepted 22/11/2022; Published 12/2022

Abstract

Despite increasing efforts, youth perspectives remain largely excluded from decision-making processes concerning their future and the social-ecological challenges they are set to inherit. While youth are a critical and powerful force for social change, many youths in underserved communities have limited access to appropriate information on the root causes and consequences of environmental change, in addition to an array of other complex social injustices. To address this, we embarked on a participatory action research process which focused on democratising research, science and the arts by facilitating experiential, immersive learning opportunities with the intention of eventually co-producing artifacts (in the form of participatory murals) in public spaces to facilitate longer term engagement with human nature futures. This article outlines and shares reflections on our process and offers insights for future engagement activities that seek to mobilise youth imaginaries and agency. We found participants were better engaged when conversations were (1) facilitated by other participants; (2) were outdoors and centred on public art; and (3) were happening in parallel with a hands-on activity. This contrasted with asking interview-type questions, or asking participants to write down their answers, which felt more like a test than a conversation, minimising participation. Key learnings included: the need to co-develop knowledge around enhancing climate literacy that is based on local realities; that multiple capacities and hives of activity already exist in communities and need to be mobilised and not built; that creative visioning and futuring can help identify options for change; and that many youths are seeking creative, immersive and safe spaces for co-learning and connection. Initiatives that aim to engage diverse voices should therefore be well-resourced so as to carefully co-design processes that start by acknowledging contextual differences and capacities within those contexts, and co-create immersive dialogues, in order to move away from test-like engagements which perpetuate power imbalances and discourage participation.

Keywords

Urban; Knowledge Co-production; Arts-Based Practice; Nature; Plastic Pollution; Resilience

Introduction

The future is bright, gets brighter every day. I am the future and the future is me (Youth Participant)

Healthy, functioning and accessible urban ecosystems have a critical role to play in enhancing the resilience of city landscapes, both now and into the future, and constitute a disproportionately important safety net for many marginalised communities (Keeler et al. 2019; Sitas et al. 2021). Rapid and unplanned urbanisation has eroded the capacity of coupled social-ecological systems to absorb, adapt and transform in response to multiple pressures, including climate change, limiting the contribution of these systems to human wellbeing through the provision of essential ecosystem services (Bai et al. 2018; du Toit et al. 2018; IPBES 2019; Keeler et al. 2019). These changes have the potential to impact almost one billion of the nearly four billion urban residents living in informal settlements in the Global South who have limited access to infrastructure, services and healthy green spaces that can buffer the impacts of rapid changes ushered in by the Anthropocene (Elmqvist et al. 2019; Shackleton & Gwedla 2021; UN Habitat 2020; Venter et al. 2020).

By 2050, cities, especially in the Global South, are predicted to account for over half of the world’s population, with youth accounting for most of this statistic (UN 2018). Ecosystems have a role to play in providing a range of opportunities and benefits for youth. However, the understanding of how ecosystems provide benefits (e.g. regulating temperature, purifying air and water, creating nature-based jobs) to society, and how interconnected humans and nature are across scales is limited, not only by the constraints of current environmental education and science communication (Lotz-Sisitka et al. 2015), but also radically under-resourced and capacitated teaching and learning environments. The often formal channels for communicating on climate change frequently miss the realities of context, with young people remaining firmly entrenched in ‘cultural memories’, some of which, in South Africa, are linked to Apartheid era injustices (Leck et al. 2011). These memories present a formidable barrier to climate change adaptation as conserving nature is often viewed as ‘for the benefit of the privileged few’, since this was historically the case. Thus development of national protected areas is often linked to displacements and restrictions of access, and challenges associated with green gentrification/urban greening (Anguelovski 2016; Rigolon & Németh 2020).

The power of cities stems from their density and diversity as they provide space for intersections of cultures, finance, innovation, aspiration and ideas. Thus, cities in the Global South have a strong imperative, as well as complex historical contexts, unique biocultural diversity and creative capacities, to advance the global sustainability agenda to be spaces for inspiration instead of just intervention (Nagendra et al. 2018; Nkula-Wenz 2019; Ziervogel 2019). Cities are increasingly hives of opportunities for experimentation, with novel responses for catalysing change (Hebinck et al. 2021; Sitas 2020). As most of the infrastructure for cities in the Global South is yet to be rolled out, there are immense opportunities for (re)imagining what equitable, resilient and multifunctional cityscapes could look like (Nagendra et al. 2019; O’Farrell et al. 2019).

Youth voices are critical to shaping these emerging cityscapes, but how their participation is envisioned and enacted will determine how their visions are included in city planning processes. Accordingly, this project sought to explore how a participatory action research process that focused on democratising research, science and the arts by facilitating experiential, immersive learning opportunities could create new insights for engaging with youth on issues linked to environmental change and its impacts.

We offer our contribution as a practice-based article to ensure it will be accessible to the partners in this research, most of whom are not from academic communities. This article provides an overview and reflection on the various processes, in terms of project planning and practice, that emerged in our iteratively co-designed work, and highlights some emergent learning. While the body of the article focuses more on the reflections and findings from our process, we have also provided rich details in the supplementary information which outline aspects of the project co-design process and methods (Supplementary material A – Table 1), a description of the workshop series (Supplementary material B – Table 2) and an overview of a workbook that was co-developed to guide our activities and capture participant reflections, imaginations and ideas (Supplementary material C - Workbook). Future communicative efforts will explore findings through film and a more theoretical paper.

Location and community characteristics

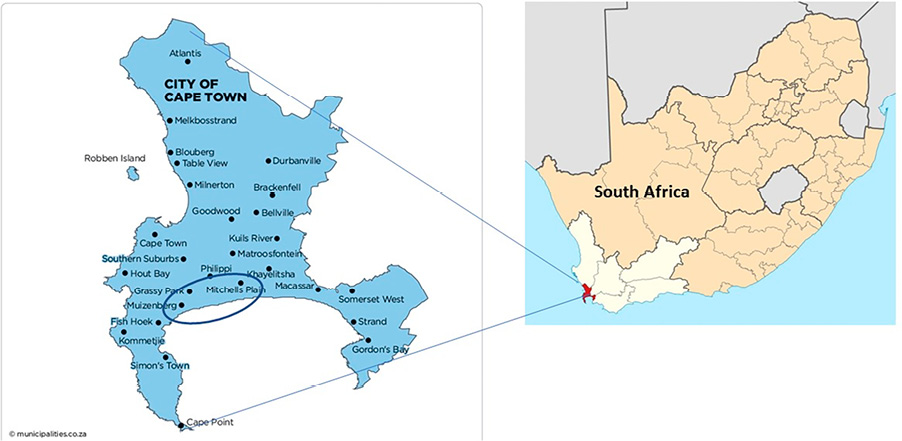

The project activities reported on here took place in Cape Town, South Africa, in two of its southern wards: Muizenberg and Mitchells Plain (Figure 3). Muizenberg is a well-established beachside holiday town with a long history of attracting wealthy beach goers from across the city and beyond. In recent years, Muizenberg has seen substantial private and public investment, especially at the beach front, making it an attractive place for tourism, surfing and eating out, as well as being a popular area to live, especially among young middle-class professionals and their families. Mitchells Plain is 17 kilometres east of Muizenberg and was established about 50 years ago during Apartheid as an area designated for middle-income Coloured communities, with the term Coloured in South Africa denoting one of four official classifications of people by race, the other three being Black, White and Indian. Many Coloured people were forceably removed from District Six (a former inner-city residential area in Cape Town) and rehomed here. Today the area houses a diversity of class backgrounds, but is known to be rife with gangsterism and drug abuse, especially among the youth. We focused on the development and maintenance of a detention point which had the potential to be a multi-use space (e.g. recreational area), compared to its currently single use as detention and channelling water out of the area.

Figure 1. Location of case study sites in (a) Cape Town, South Africa, and (b) Muizenberg and Mitchells Plain

Methodology

Awakening critical consciousness through arts-based practices has a long history of emancipatory engaged scholarship, developing what Freire (1970) referred to as conscientization. Art-based and embodied methodologies are therefore an effective way to develop passion for and emotional connection with environmental issues and can help surface future imaginaries of what options exist for change. Art-based approaches can also provide spaces where negative dystopian views of the future can be transformed by creating positive visions and emotions linked to hope, solidarity, responsibility and care (Pereira et al. 2019). We used a participatory action research approach (Ballard & Belsky 2013) to understand the ways in which immersive and arts-based methods could strengthen opportunities for engaging urban youth in understanding environmental concerns and impacts.

Our methodology was underpinned by an ethic of care and co-designed to avoid being extractive (Coombes et al. 2014; Haverkamp 2021), and immersive workshops and ‘courageous conversations’ were facilitated to minimise didactic learning practices.

Supplementary material A – Table 1 highlights the different elements and rationale for our research design, which includes a description of the project team, the co-design process, the methods used, how participants were recruited, an outline of the workshop series and a description of how data were collected and analysed. There were three workshops, each comprising various methods of engagement (Supplementary material B – Table 2). During the first workshop, each person was handed a workbook (Supplementary material C – Workbook) on which to document their reflections as they embarked on a silent beach clean-up, an estuary (vlei) clean-up, and discussions on climate change and the role of public art.

We used plastic pollution as a tangible ‘entry point’ to conversations around environmental change and its impacts on social–ecological systems (see Supplementary material B – Table 2, ‘Workshop 2’).

Results and discussion

Below we present emerging reflections on our process and an analysis of the outcomes of the workshops, which we combine in this section.

Engaging with plastic pollution as an entry point for participation

We received feedback that the silent beach clean-up was an enjoyable process for many and the participants enjoyed being by the ocean and having time to be in their own thoughts. Participants also reflected on how, when you look, it is very clear that pollution is everywhere, something that some admitted they would previously not have noticed. For example, participants mentioned:

How we often don’t see it [plastic] until we are looking for it, how we can tune our eyes into see different things that we bring our attention to, what else are we not seeing?

That so many of us do not know that we are living amongst our own trash.

How we are beautiful, curious fun-loving humans yet often it is our enjoyment of life that is destructive to the planet like a day at the beach & how much plastic this leaves behind.

Through experiential learning that occurred during the clean-up events, it emerged that we cultivated deeper systemic understanding of the links between personal choice, community and the environment (including rivers, canals, wetlands and oceans), thereby cultivating a stronger sense of community responsibility and agency in the participants involved, with participants reflecting that they would initiate clean-up activities closer to home and/or engage in existing litter clean-up activities as a way to ‘give-back to nature who does so much for us for free’. Similarly, Jorgensen, Krasny and Baztan (2021) found that volunteer beach clean-ups fostered environmental stewardship.

The process of focusing on an activity with one’s hands, of ‘weaving’ plastic into a rug through the Hydro-rug process, allowed for a sense of distraction from our differences and connection with our own and each other’s stories. This process surfaced intergenerational stories and connections with water, combining folklore, superstition and visions of opportunities to connect more in seascapes to conquer fears or learn about new watery worlds. Enqvist et al. (2019) suggest that strong place attachment can promote deeper stewardship commitment and thus activities that connect people to natural spaces, both tangibly through immersive activities or through storytelling, and can help foster connections to place.

Our experience of the process of engaging in an artistic activity, such as that experienced during the hydro-rug process, was that, by providing the space to go inward and to actively focus attention on our own thoughts and creativity, we facilitated an atmosphere where we were more connected as a group. We bonded over an activity, a process of personal expression that was, at the same time, inherently collective, whereas a reflection around the room session often makes people feel that they have to say the correct thing. There was no pressure to actively engage with one another, but connection was inevitable – either through conversation, observing each others’ creative expressions or simply through sharing the space. This contrasted with putting people on the spot to answer questions in a focus-group type session, which often makes them feel like they have to say the ‘correct’ thing.

Art for democratising science

The project team reflected that the facilitated discussions around the estuary mouth felt much more like an outside ‘lecture’ where the distinction between facilitators and participants was very clear. More animated and engaging two-way dialogues and engagement only really gained momentum with the discussion around public art and its role in society. This emphasised the importance of connecting around issues through a common language, as highlighted by a participant who said:

We come from very different places with very different mother tongue languages so what I’m interested in when we try and create those spaces of community what languages can we use that make sense for all of us especially science and academia and their big words and I’m English and I don’t understand – I’m excited about the idea of using things like art as a language that we all have in common to express ourselves and make sense of life with it.

Creating novel and imaginative spaces for reflexivity, learning and experimentation with arts can play a critical role in shifting mindsets and providing inclusive and safe spaces for opening up new political horizons and visions of the future (Bentz & O’Brien 2019; Galafassi et al. 2018).

The group became even more engaged during the discussion on climate change, which was led by youth facilitators who told their own stories of how they became climate activists. While initial conversations centred on how climate change was not perceived to be an issue for many urban youth, being a thing happening ‘out there’, the youth facilitators used lived experiences of floods, droughts and fires to connect seemingly global issues to local impacts. Framing climate change through the lens of impacts on these communities resonated with people, most of whom had first-hand experiences of them in their neighbourhoods. Participants reflected that climate change was taught abstractly in school, or they heard about it from researchers or on TV linked to high-level policy discussions, and that none of the people talking about it looked and acted ‘like us’, and as one participant put it:

African climate justice activists should be on the international panels in order to make informed decisions. We also need young people taking up space educating and creating awareness.

Another participant added that:

More localized climate change starts in our thoughts and then moved to the heart & hands. Instead of climate change stories, news and headlines just spoke about by experienced advocates, it should start when children are young – this would result in youth and young adults who are more careful towards our planet earth and people care.

Numerous participants spoke about the justice dimensions of climate impacts and wanted to know what they, as young people, could do to spread information to their neighbours, family members and friends about climate change being a shared risk, but also a shared responsibility to address.

What also emerged strongly from our workshops was the need to co-develop more Afrocentric climate literacy through inclusive, accessible and creative knowledge co-production processes (Macintyre et al. 2018) as this information was perceived to be lacking. For example, Chirisa, Matamanda and Mutambwa (2017) suggest that science tends to ask for collective action based on regional and global trends in climate change, while indigenous technical knowledge (ITK) first observes that ‘something is wrong somewhere’. Without pinpointing context and the place-based problem, discussing general trends becomes meaningless. Science-focused and fear-based facts that aren’t contextualised to the lived realities of participants, and especially youth, hold little resonance. Research suggests that education surrounding climate and environmental change should become responsive to the existing beliefs, attitudes and situational contexts of specific audiences (Brownlee, Powell & Hallo 2013) and be complimented by participatory and arts-based modes of engagement, especially with youth (Rousell & Cutter-Mackensie-Knowles 2020). We found the need to challenge deficit discourses that alledged youth and other marginalised groups need capacities ‘built’ as if they have no capacities.

This project reaffirmed that the capacity for change already exists in individuals and their communities in the form of values, knowledge, skills, agency, relationships, imagination and other resources. What is needed is the elevation of youth voices and youth empowerment through mobilisation of existing capacities in communities to communicate the urgency of climate action. Bringing people into conversations, assuming they have nothing to add until they are capacitated to do so, does not encourage them to bring what they know, their experiences, and reflects power imbalances that perpetuate feelings of not being heard. Thus, huge and currently untapped potential exists to build on existing hives of activity by leveraging on a diverse set of existing creative projects and organisations that focus on climate, biodiversity, energy and social justice, as offered by local organisations.

Learning from the emerging future

Talking about the future was often difficult, especially for participants who were bringing spoken and unspoken trauma with them into the workshops. Here we recognise the importance of trauma-informed work (Champine et al 2022; Rosenberg, Errett & Eisenman 2022) and that we have much to learn about creating safer spaces for people to identify and see pockets of potential that can be amplified in different ways to co-create the future we want to see, in the present. Committing to furthering decolonial methods, approaches and movements in our work can enable us to avoid ‘colonising our future’ by facilitating visioning exercises that retain features of unjust systems and carry them into our envisioned futures (de la Rosa Solano, Franklin & Owen 2022; Wilkens & Datchoua-Tirvaudey 2022). As a collective, we are working on co-designing what these could look and feel like for future engagement. A starting point is that we need to continue to leverage our privilege and mobilise diverse, intersectional and inclusive contributions from many lived experiences and backgrounds, especially from youth in underserved and climate-affected communities.

We visited a detention pond in Mitchells Plain, where several institutions (University of Cape Town, Danish International Development Agency, City of Cape Town) are piloting the transformation of its original design to control excess stormwater drainage to a multi-use space. The proposal is for an area that promotes the retention of stormwater for aquifer recharge and the regeneration of endemic biodiversity, and in the process a co-created urban space to support recreational activities for the surrounding community. This was a space that was relatively unknown by many of the facilitators and participants. Our presence drew some interest from nearby residents who were curious to learn why we were in their neighbourhood. An immediate question for the project team was ‘who gives us the “right” to be here, bringing new people into this space’. While we connected with researchers working on the detention pond, there was not the same effortlessness we felt when working on our familiar turf of Muizenberg, which made us question whether place-making or stewardship could be cultivated in places where people are not rooted?

Nonetheless, reflections from participants suggested that many of them did not know the purpose of these green spaces that they recognised in their neighbourhoods. Everyone was visibly moved and commented with awe when, after we sang and clapped indigenous songs to honour the space and the history that came before us, the frogs in the reeds erupted in a chorus. This moment was described a few times in workshops as meaningful, as it reminded participants that nature can be found in the most surprising spaces and that, if we care for these spaces, important ecosystem functions can return.

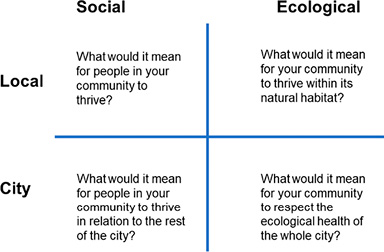

On our drive back to Muizenberg in two cars we used the opportunity to discuss the questions that were posed in the City Portrait Canvas quadrant (See Figure 6 in Table 2 of Supplementary material). These questions included: (1) What would it mean for people in your community to thrive? (2) What would it mean for people in your community to thrive in relation to the rest of the city? (3) What would it mean for your community to thrive within its natural habitat? and (4) What would it mean for your community to respect the ecological health of the whole city? (Adapted from the City Portrait Canvas from the Doughnut Economics Lab). In both cars, the conversation did not go much further than the first question as it quickly became evident that these questions required much more context and preparation. Firstly, what does ‘thrive’ mean in a social context and in an ecological context? Secondly, the answers that were given indicated that perhaps these questions do not acknowledge several key features that are often characteristic of the Global South. An answer from one of the participants who lived in Khayelitsha, one of Cape Town’s largest township areas with high levels of informality, was ‘we need the government to fix our leaking sewage pipes so we are not walking through sewage to get to our home’ quickly indicated that much more thought was needed in applying these questions in these contexts. How can one begin to re-imagine futures when basic physical needs are not being met? And when much of what is required to have these needs met depends on an actor external to our actionable world (i.e. beyond our perceivable sphere of influence). In the other car a participant mentioned:

Why would I believe that anything would be different, it has been like this for 20 years, nothing has changed since then and nothing will change for me for the next 20 years.

One immediate lesson that emerged for facilitators was that the youth involved in this project came from very different circumstances, making it challenging for them to launch into what their imagined futures might be. Without understanding their current situation and the issues that were front of mind for them, it was not possible for them to imagine a different future for themselves through conversations and questions like these. This is critical because a lot of climate and other environmental communication that researchers, activists and the city aim to disseminate will likely not land for young people if the message does not consider where they are ‘at’ and what collective and individual traumas they are often processing. Starting with a visioning exercise before first surfacing these lived realities did not encourage a natural flow in conversation – rather it highlighted differences in home environments amongst the group.

While the City Portrait Canvas questions did not stimulate generative conversations, the Hydro-rug process did offer an informal, positive way of encouraging participants to share stories of their own connection to water, highlighting that these more dialogical/storytelling methods could be used in combination with futuring tools to move beyond sharing of experiences to processes that can analyse and dismantle oppressive structures.

Reclaiming the commons for community making

We found that the research process was much less about imparting, sharing or gathering knowledge and much more about sharing a process together. As Freire (1995, p. 31) puts it:

Through dialogue, the teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist and a new term emerges: teacher-student with student-teachers. The teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach. They become jointly responsible for a process in which all grow.

There was a sense that facilitators truly felt like participants, as highlighted by one of the artists:

Today the vision becomes real, the same way if we keep making our visions clearer and clearer and sharing them with each other they can drop down into reality in a way that we don’t expect. We can create a future that we are inspired to move towards and along the way if we have a clear idea we see clues along the way and that is something reminds you of your future and we can bring energy together more quickly move together to a future we want.

One of the new youth members of the project reflected that:

It was first time I was in a circle like this and experienced the best things, Aweh! and it was just nice to be amongst new people and feel like we are building a sense of community just for that day, we are creating our own space within a new space.

Many articulated a desire to have more spaces to gather and learn about important issues and how to open up the spaces for more participants. As one youth mentioned:

New voices must be heard, there must be much more space to have these conversations.

Reflections at the last workshop all shared the same sentiment that these spaces are for community making and for activating new and existing spaces to be spaces of healing, co-learning and creativity. Even though those who had engaged in the entire workshop series found it very beneficial to be part of the whole process, there was an acknowledgement that there should have been opportunities for people to connect at different times, as highlighted by a participant who said:

I’m so excited to be here again, it’s a thing of community, of how we can create spaces of community even though the people in that space can come and go.

Using many indoor and outdoor spaces across our neighbourhoods for collective learning events as a strategy to reclaim community spaces for transgressive learning sparked a desire for more gatherings in these spaces. This, together with using arts-based practices as platforms for catalysing difficult conversations, co-learning and inspiration deepened the sense that we were in a process of ‘community making’, by having courageous conversations around whose future we were fighting for. Processes that were facilitated outdoors, offering opportunities to connect tangibly with nature, made a big difference to communicating and understanding key landscape features, as well as witnessing the human impact or intertwined relationships in these spaces, also found by Jose, Patrick and Moseley (2017). Building space for ‘doing nothing’ in nature was also highlighted as being refreshing and offering participants quiet moments of reflection and healing away from the hustle of urban living, which is akin to Audre Lorde’s (1988) notion of self-care as an act of political warfare and communal effort.

Conclusion

Many city-scale policies and engaged scholarship processes highlight a need for new methodologies that can create opportunities for greater understanding of the underlying factors and root causes of systems that are trapped in undesirable situations, but also where ‘seeds’ or pockets of potential future transformation might exist. We hope that our series of workshops will act as a catalyst for public enrolment and have transformative potential for political (re)orientation, fostering new perceptions and dispositions of (future) citizens (Sitas & Pieterse 2013) for those involved, but also as a guide to how inclusion and participation of marginalised voices can be strengthened. Urban youth, in particular, are often overlooked in their role as active citizens, having agency and social cohesion, and also in how this plays out in advancing some of the goals towards building social–ecological resilience. The same goes for the question of what role social cohesion will play in advancing these goals. Co-designing engagement processes can assist greatly in informing more inclusive, socially relevant and non-extractive scholarship, but the necessary transformation of how knowledge is produced and mobilised and the deconstruction of knowledge hierarchies remains a never-ending process that necessitates ongoing attention to power dynamics and ‘care-full’ scholarship. For the transgressive engaged research that is needed, deft juggling skills will be required to navigate both academic and political rigour (Temper, McGarry & Weber 2019).

Endnotes

At the time of writing this article, despite support from the City, we have only just been given the green light for a permit to paint our participatory mural in a public space in Cape Town. This has involved drawn-out consultation with a local rate payer association which was not in favour of the mural. The workshop series and engagement sessions have involved many courageous conversations and have catalysed a longing for spaces to share stories and visions of the future in words, songs, paintings and food. These gatherings will be in various formats, some of which will be linked to future transdisciplinary projects that are in the pipeline, some will engage city officials on strategic interventions, while others will co-develop learning materials needed to mobilise climate action, or silent litter clean-ups. In the words of one of our participants:

we’re all seeking the community we’ve now sown the seeds for, we just need to show up and do the work, and this work needs to happen in different ways, with different heads and hearts and hands.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the participants for their passion and enthusiasm, and deep and meaningful insights during this workshop series. We would also like to thank the funders of this research, the Cape Higher Education Consortium (CHEC) and City of Cape Town, for driving this new community of practice that has energy to co-create further work. We are deeply grateful for all the participants and facilitators who co-funded their time to work on this project and the many hands and hearts behind the scenes that assisted with admin, extra meals, social media posts and project management.

References

Anguelovski, I 2016, ‘From toxic sites to parks as (green) LULUs? New challenges of inequity, privilege, gentrification and exclusion for urban environmental justice’, Journal of Planning Literature, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412215610491

Bai, X, Dawson, R, Ürge-Vorsatz, D, Delgado, G, Barau, A, Dhakal, S, Dodman, D, Leonardsen, L, Masson-Delmotte, V, Roberts, D & Schultz, S 2018, ‘Six research priorities for cities and climate change’, Nature, vol. 555, pp. 23–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-02409-z

Ballard, H & Belsky, J, 2013, ‘Participatory action research and environmental learning: Implications for resilient forests and communities’, in Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems, Routledge, pp. 152–68).

Bentz, J & O’Brien, K 2019, ‘Art for change: Transformative learning and youth empowerment in a changing climate’, Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 52. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.390

Brownlee, M, Powell, R & Hallo, J 2013, ‘A review of the foundational processes that influence beliefs in climate change: Opportunities for environmental education research’, Environmental Education Research, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2012.683389

Champine, R, Hoffman, E, Matlin, S, Strambler, M & Tebes, J 2022, ‘What does it mean to be trauma-informed?’: A Mixed-Methods study of a trauma-informed community initiative, Journal of Child and Family Studies, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 459–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02195-9

Chirisa, I, Matamanda, A & Mutambwa, J 2017, ‘Africa’s dilemmas in climate change communication: Universalistic science versus indigenous technical knowledge’, in Handbook of Climate Change Communication, vol. 1, pp. 1–14, Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69838-0_1

Coombes, B et al. 2014, ‘Indigenous geographies III: Methodological innovation and the unsettling of participatory research’, Progress in Human Geography, vol. 38, no. 6, pp. 845–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513514723

De la Rosa Solano, S, Franklin, A & Owen, L, 2022, ‘Participative and decolonial approaches in environmental history’, in Co-creativity and Engaged Scholarship (pp. 105–29), Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84248-2_4

Du Toit, M, Cilliers, S, Dallimer, M, Goddard, M, Guenat, S & Cornelius, S 2018, ‘Urban green infrastructure and ecosystem services in sub-Saharan Africa’, Landscape and Urban Planning, vol. 180, pp. 249–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.06.001

Elmqvist, T, Andersson, E, Frantzeskaki, N, McPhearson, T, Olsson, P, Gaffney, O, Takeuchi, K & Folke, C 2019, ‘Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century’, Nature Sustainability, vol. 2, no. 4 , pp. 267–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0250-1

Enqvist, J, Campbell, L, Stedman, R & Svendsen, E 2019, ‘Place meanings on the urban waterfront: A typology of stewardships’, Sustainability Science, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00660-5

Freire, P & Macedo, D 1995, ‘A dialogue: Culture, language and ace’, Harvard Educational Review, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 377–402. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.65.3.12g1923330p1xhj8

Galafassi, D, Tàbara, J, Heras, M, Iles, A, Locke, K & Milkoreit, M 2018, ‘Restoring our senses, restoring the Earth: Fostering imaginative capacities through the arts for envisioning climate transformations’, Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, vol. 6. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.330

Haverkamp, J 2021, ‘Where’s the love?: Recentring Indigenous and feminist ethics of care for engaged climate research’, Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v14i2.7782

Hebinck, A, Selomane, O, Veen, E, De Vrieze, A, Hasnain, S, Sellberg, M, Sovová, L, Thompson, K, Vervoort, J & Wood, A 2021, Exploring the transformative potential of urban food. npj Urban Sustainability, vol. 1, no. 1, pp.1-9. https://www.nature.com/articles/s42949-021-00041-x https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-021-00041-x

IPBES 2019, ‘Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services’, IPBES Secretariat, Bonn, Germany. https://ipbes.net/global-assessment

Jorgensen, B, Krasny, M & Baztan, J 2021, Volunteer beach cleanups: Civic environmental stewardship combating global plastic pollution’, Sustainability Science, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 153–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00841-7

Jose, S, Patrick, P &Moseley, C 2017, ‘Experiential learning theory: The importance of outdoor classrooms in environmental education’. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 269–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2016.1272144

Keeler, B, Hamel, P, McPhearson, T, Hamann, M, Donahue, M, Prado, K, Arkema, K, Bratman, G, Brauman, K, Finlay, J & Guerry, A 2019, ‘Social-ecological and technological factors moderate the value of urban nature’, Nature Sustainability, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0202-1

Leck, H, Sutherland, C, Scott, D & Oelofse, G 2011, ‘Social and cultural barriers to adaptation implementation: The case of South Africa’, in L Masters & L Duff (eds), Overcoming barriers to climate change adaptation implementation in southern Africa, Africa Institute of South Africa, Pretoria, pp. 61–88).

Lorde, A 1988, A burst of light, Firebrand Books, Ithaca, New York.

Lotz-Sisitka, H, Wals, A, Kronlid, D & McGarry, D 2015, ‘Transformative, transgressive social learning: Rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction’, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 16, pp. 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.07.018

Macintyre, T, Lotz-Sisitka, H, Wals, A, Vogel, C &Tassone, V 2018, ‘Towards transformative social learning on the path to 1.5 degrees’, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 31, pp. 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.12.003

Nagendra, H, Bai, X, Brondizio, E & Lwasa, S 2018, ‘The urban south and the predicament of global sustainability’, Nature Sustainability, vol. 1, no. 7, pp. 341–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0101-5

Nkula-Wenz, L 2019, ‘Worlding Cape Town by design: Encounters with creative cityness’, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 581–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18796503

O’Farrell, P, Anderson, P, Culwick, C, Currie, P, Kavonic, J, McClure, A, Ngenda, G, Sinnott, E, Sitas, N, Washbourne, C & Audouin, M 2019, ‘Towards resilient African cities: Shared challenges and opportunities towards the retention and maintenance of ecological infrastructure’, Global Sustainability, vol. 2. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2019.16

Pereira, L, Sitas, N, Ravera, F, Jimenez-Aceituno, A, Merrie, A, Kapuscinski, A, Locke, Moore, M 2019, ‘Building capacities for transformative change towards sustainability: Imagination in Intergovernmental Science-Policy Scenario Processes’, Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 7. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.374

Rigolon, A & Németh, J 2020, ‘Green gentrification or “just green enough”: Do park location, size and function affect whether a place gentrifies or not?’, Urban Studies, vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 402–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019849380

Rosenberg, H, Errett, N & Eisenman, D 2022, ‘Working with disaster-affected communities to envision healthier futures: A trauma-informed approach to post-disaster recovery planning’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 19, no. 3, p. 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031723

Rousell, D & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A 2020, ‘A systematic review of climate change education: Giving children and young people a ‘voice’ and a ‘hand’ in redressing climate change’, Children’s Geographies, pp. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2019.1614532

Shackleton, C & Gwedla, N 2021, ‘The legacy effects of colonial and apartheid imprints on urban greening in South Africa: Spaces, species, and suitability’, Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, vol. 8, pp. 579–813. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.579813

Sitas, R 2020, ‘Becoming otherwise: Artful urban enquiry’, Urban Forum, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 157–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-020-09387-4

Sitas, R & Pieterse, E 2013, ‘Democratic renovations and affective political imaginaries’, Third Text, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 327–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2013.798183

Sitas, N, Selomane, O, Hamann, M & Gajjar, S 2021, ‘Towards equitable urban resilience in the Global South within a context of planning and management’, in Urban Ecology in the Global South (pp. 325–45), Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67650-6_13

Temper, L, McGarry, D & Weber, L 2019, ‘From academic to political rigour: Insights from the “tarot” of transgressive research’, Ecological Economics, vol. 164, p. 106379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106379

UN Habitat, World Cities report 2020. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/10/wcr_2020_report.pdf

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2018, The World’s Cities in 2018, Data Booklet (ST/ESA/SER.A/417).

Venter, Z, Shackleton, C, Van Staden, F, Selomane, O & Masterson, V 2020, ‘Green Apartheid: Urban green infrastructure remains unequally distributed across income and race geographies in South Africa’, Landscape and Urban Planning, vol. 203, p. 103889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103889

Wilkens, J & Datchoua-Tirvaudey, A 2022, ‘Researching climate justice: A decolonial approach to global climate governance’, International Affairs, vol. 98, no. 1, pp. 125–43. https://academic.oup.com/ia/article/98/1/125/6484828?login=false. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiab209

Ziervogel, G 2019, ‘Building transformative capacity for adaptation planning and implementation that works for the urban poor: Insights from South Africa’, Ambio, vol. 48, no. 5, pp. 494–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1141-9

Supplementary Material A

| Project element | Description | Rationale / Reflection |

|---|---|---|

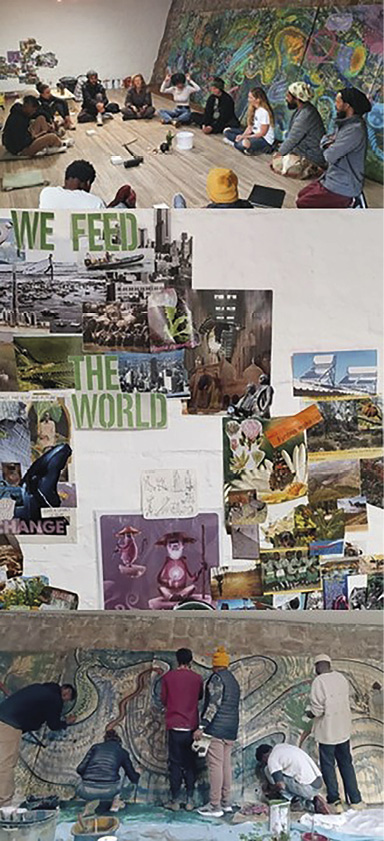

| 1. Project team | The project is a collaboration between researchers from the Centre for Sustainability Transitions (CST) at Stellenbosch University (Sitas, N and Selomane, O), the University of Cape Town and The Beach Coop (Atkins, F); facilitators from Amava Oluntu (Hlongwane, E, Fanana, S, Wigley,T and Boulle, T) who work with local youth; and locally-based artists CareCreative (Claire Homewood) and Mac1 and other members of the HC360Crew (DFeat once, Urban Khoi Soldier). |  Figure 2. Project team meeting to plan the workshop series The project team sought to build on a portfolio of existing work that had been co-created through a number of research and arts collaborations that the project team has been involved in, instead of creating something completely new. We intentionally worked with youth facilitators from an organisation (Amava Oluntu) with a track record of projects on the workshop sites. All project team members were involved in the co-design of the project. |

| 2. Project co-design | Our project sought to co-design the project from the outset, first through joint planning of the process, with the authors of this contribution stemming from diverse collaboratives and non-academic institutions. The collaborators brought in questions and methods from the communities they work with, and these were further shaped by participants and the questions and contestations that surfaced through workshops. | This iterative process of planning, reflection and adaptation facilitated immense learning for the project team which resulted in some of the lessons we highlight in this article. Our approach was transdisciplinary, with each team member being responsible for ‘holding’ different stages/parts of our process based on their expertise and/or knowledge of the workshop sites, e.g. climate researchers, public artists, water researchers and activists. |

| 3. Arts-based immersive methods | We used outdoor spaces as immersive living labs and combined content discussions with individual and collective reflective opportunities guided by a co-created workbook (see supplementary material A). Wherever possible, we provided spaces for creative reflections through arts-based processes, including collaging, drawing, painting and story-telling. Details of how each process was run are given in the Workshop Flow and Reflection section and Table 2. | Our project centred on the premise that providing safe playful spaces for transformative learning experiences to occur, and facilitated in ways that unlock future imaginaries, was important for instilling agency and purpose in future generations. Immersive learning experiences – both in nature and in creative co-constructed imaginary worlds – can be powerful tools to spark (re)imagination of radically different futures to the realities of the everyday. Connecting to radically different ways of seeing the future is a critical tool in the arsenal of science communication for improved sustainable development decision-making in a time of unprecedented human-induced social and environmental change. |

| 4. Co-creation of workbook | We co-created workbooks for participants to use during the workshop series. We adapted information from local organisations working on the thematic issues our project engaged with (e.g. information on plastic pollution and climate change), as well as methods designed to foster imaginative processes (e.g. questions about what types of futures participants envisioned). | The workbook (supplementary information A) was developed for a number of purposes:

|

| 5. Participant recruitment | Originally participants were recruited through an online call, which was shared through our networks. Requirements for participation initially needed participants to live in Mitchell’s Plain or Muizenberg. These two areas were chosen to reflect inland (Michell’s Plain) and coastal systems (Muizenberg) – see Figure 2 below. For this work, we set age-based criteria for recruiting participants (18–30 years) for procedural reasons linked to our university ethics requirements of working with minors, but offer reflections of working with youth in this article. | We received a large response from those living in other neighbourhoods, which made us question our selection criteria. In the end, over 50 youth from a variety of neighbourhoods in Cape Town engaged in the workshop series. Transport, airtime (cell phone call credits) and mobile data were provided to facilitate ease of travel and the ability to communicate and share pictures, stories and reflections via a Whatsapp group that was created. For participants who did not have access to a mobile phone, we communicated through the institutions they were engaged in or through word of mouth by participants. We foregrounded all workshops with conversations around informed consent and these were revisited to ensure that all participants felt comfortable with how information, pictures, videos and insights would be used. |

| 6. Workshops | We held three workshops in locations that were familiar or at least accessible to project facilitators. The first two workshops entailed an immersive process of being outside, a plastic clean-up, discussions centred around several location-specific themes, such as plastic, wetlands and estuaries, art in public spaces, climate change and historical injustices. During these workshops and discussions, space was created for reflection and inputting into the workbook. The last workshop was focused around bringing these themes together and creatively bringing them into conversation through discussion, collage, drawing or painting the murals. | The purpose of each workshop was to develop a more systems perspective of the site and how people and nature are connected across scales, both temporally and spatially, and how actions at different sites/scales can have cascading impacts on people and nature. Each workshop started with an opening blessing, which could be in the form of a poem, a song or a story from a participant. As the workshops were held in Cape Town, we acknowledged the Indigenous Khoisan custodians of the spaces where we gathered. All workshops also paid close attention to food as a connector: as both a source of nourishment and to anchor conversations in communities through food made in community kitchens. Further details of what each workshop entailed are provided in the Workshop Flow and Reflection section and Table 2. |

| 7. Data collection and analysis | We relied on multiple sources of data, including photographs, videos, voice recordings, observation and notes from the project team. We also collected workbooks at the end of each workshop to capture key insights and reflections from participants. The main source of information came from reflections shared at project team meetings, which were captured through voice recordings and notes. We analysed data using thematic analysis through an iterative process of joint sense-making within the team. Emerging themes were then negotiated and discussed, and then written down. | The emerging themes were used to inform subsequent workshop planning, e.g. to plan specific questions for participants to discuss, to gather material for creative processes, or to move away from ‘pipe-line’ models of knowledge transfer (i.e. expert ‘lecturing’ of participants on their topic) towards more two-way modes of engagement. We also paid attention to what made participants ‘come alive’ and share more openly, which often involved an activity, e.g. doodling or sketching, painting boards or collecting plastic. |

Supplementary Material B

| Workshop and location | Description |

|---|---|

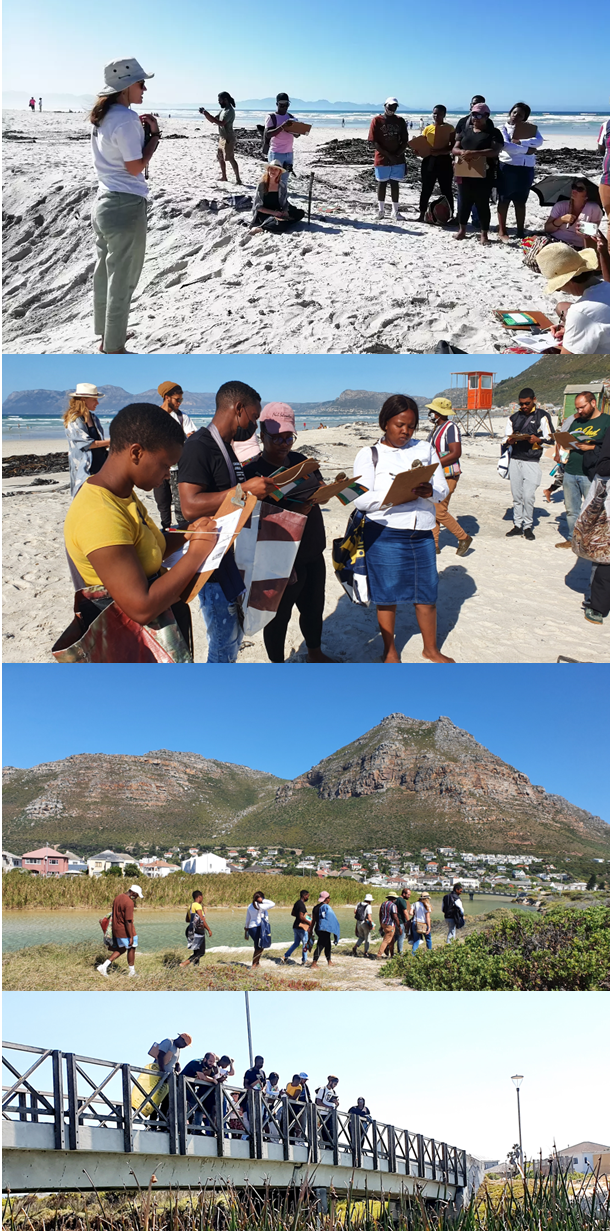

| Workshop 1: Experiential learning and conversations Location: Muizenberg beach and Zandvlei estuary  Figure 4. Walkshop along Muizenberg beach and Zandvlei estuary, Muizenberg.  Figure 5. Workshop 1 participants discussion the role and value of art in public spaces. |

The workshop started with introductions between youth members coming from various neighbourhoods across Cape Town, facilitators, and the project team. We focused on answering the questions: How are we connected to each other? How are we connected to the sea? What do we love to do? We proceeded on to the immersive component of the workshop through a walk highlighting various social-ecological issues on the landscape. This involved a few steps. First, the participants were introduced to a citizen science initiative, the Dirty Dozen, which was facilitated by project collaborator, Beach Co-op (https://www.thebeachcoop.org/). The process involved a silent walk and beach clean-up along Muizenberg beach, through which participants were urged to observe their surroundings and pick up plastic items on the beach. Once collected, they identified the Dirty Dozen items, which are the 12 most common items found on our beaches and rocky shores. This was followed by discussions around plastic pollution, to connect what the participants experienced on the walk with the impacts of this pollution on the ecosystems. Second, the walk proceeded to Zandvlei Estuary Nature Reserve to discuss the role of wetlands and estuaries, and how pollution from land uses such as agriculture, canalisation to improve boating and other modifications of the landscape affect the functionality of these systems, and as a result affect various fish species which use this as a nursery. Third, we proceeded to a work of public art along one of the buildings in the reserve, with the intention to discuss the role of public art in communicating issues such as climate change and to surface narratives emerging from these conversations. These conversations were facilitated by the artist collaborators in the project who highlighted both the impacts and responsibilities around public art. The walk finally ended at a ‘Fynbos Mandala’, where discussions about climate change, extinction risk and climate justice continued. The last part of (and throughout) this workshop involved creative harvesting, where using the workshop booklet, participants could ‘download’ their experience of the workshop into a visual form or write emerging reflections, followed by a shared lunch at the Muizenberg Community Kitchen. |

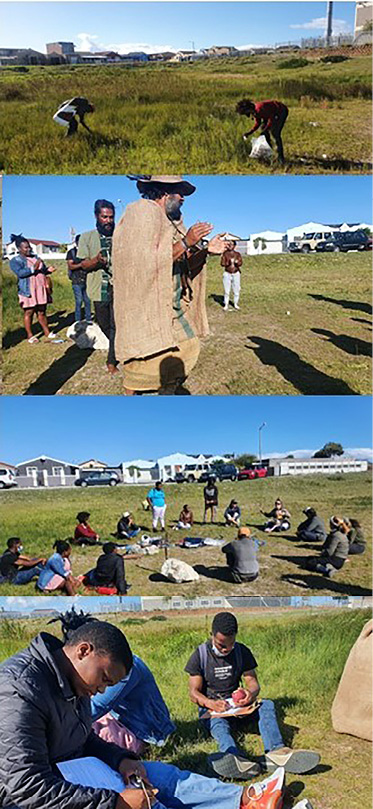

| Workshop 2: Connecting people and places Location: Mitchells Plain – stormwater detention pond  Figure 6. Scenes from Workshop 2 and the Mitchells Plain stormwater detention pond. |

Similar to workshop 1, and also because the participants group had changed somewhat (we lost some participants and gained some new participants), the workshop started with a brief round of introductions, and an introduction to a space, which was one of Cape Town’s 737 storm water detention ponds, critical for slowing water flows and reducing urban flooding, but often seen as a barren unused greenspace that could be allocated for housing. Next, a process of connecting to place was facilitated by a local Indigenous Chief through song and dance. This was followed by a litter clean-up to honour the space and make a connection to the plastic that was collected on the beach at the previous workshop to facilitate systems thinking of ‘source-to-sea’ and how waterways are often conduits of plastic in landscapes. A conversation was then facilitated about what the site was originally and what it was used for now, and identifying what other projects were currently underway (such as a project by the University of Cape Town advocating for multiple uses of the green open spaces). Duing this process, we also noted and highlighted links between neighbourhood, rivers and canals, and the ocean and how many of these types of spaces hold legacies of brutal apartheid spatial planning processes. In the effort to solicit human-nature future visions, we adopted a City Portrait Canvas methodology used by the Doughnut Economics lab, which asks four questions (Figure 6). |

Figure 7 Adapted City Portrait Canvas questions from the Doughnut Economic Lab (found online at https://doughnuteconomics.org/tools/76). |

Conversations covering these four questions were facilitated as part of the drive from Mitchells Plain to Muizenberg, where participants could stick sticky notes containing reflections on the quadrants and share their reflections with other participants. These conversations were recorded with permission. The last leg of the workshop was facilitated at the Amava Oluntu Studio in Muizenberg and comprised continued engagement in workshop booklets and facilitated conversations around stories of connection to water through a Hydro-Rug process by Aaniyah Martin-Omardien from The Beach Co-op, together with a shared lunch from the Muizenberg Community Kitchen. The Hydro-rug is a social sculpture method developed by Aaniyah Omardien-Martin from The Beach Co-op, which involves citizen led public storytelling around the invisible histories of and relationships with the ocean, with the explicit aim to surface new care practices related to the ocean which reveal indigenous and local meaning making, world-views, histories and memory. |

Figure 8 The hydro-rug process, facilitated by Aaniyah Martin-Omardien from The Beach Co-Op. Figure 8 The hydro-rug process, facilitated by Aaniyah Martin-Omardien from The Beach Co-Op. | |

| Workshop 3: Creative studio and collaborative future visioning Location: Muizenberg Community kitchen  Figure 9. Scenes from workshop 3: participants starting off the participatory mural painting process and some examples of the collage that was created. |

The original plan was to paint a participatory mural in a public space as the final product of this project. Slow city processes and competing multiple jurisdictions (e.g. two city departments owning parts of the same wall we intended to paint) meant that we had not obtained the permit to paint a public wall in time, and so our third workshop involved a creative studio session where we painted on six 2.4m x 1.2m boards. We gathered and reintroduced ourselves, indicating what we enjoyed about the previous workshops and what we were looking forward to in this one. There were a few new participants who hadn’t been present in the previous two workshops, so they were invited to share what drew them to the workshop. Following a visioning process which featured prompts from a Donella Meadows ‘Down to Earth’ speech delivered in 1994 to help us envision the visions of nature-futures we longed for, we moved the visions we held in our minds-eye into a creative space to make them come alive. We provided three separate workplaces through which participants could feel free to roam: a drawing station with a library of books to find inspiration, if needed; a collage station with magazines; and a wall to display the collage. The other was the main mural painting boards with multiple paints and paint brushes. Participants were left to their own devices and each either found their station or spent some of their time at each. The day closed with a shared lunch in the Muizenberg Community Kitchen. |

Supplementary Material C