Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 15, No. 2

December 2022

RESEARCH ARTICLE (PEER-REVIEWED)

‘Do You Own Your Freedom?’ Reflecting on Cape Town Youths’ Aspirations to Be Free

Mercy Brown-Luthango1,*, Rosca van Rooyen2

1 African Centre for Cities, School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics, University of Cape Town

2 NoDread Pty (Ltd) and African Centre for Cities, School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics, University of Cape Town

Corresponding author: Mercy Brown-Luthango, mercy.brown-luthango@uct.ac.za

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v15i2.8210

Article History: Received 01/06/2022; Revised 30/09/2022; Accepted 08/12/2022; Published 12/2022

Abstract

Young people make up half of the world’s population and constitute the majority of the population across the Global South (Cooper et al. 2019). In South Africa, the youth constitute one-third of the country’s population, many of whom belong to the so-called ‘born free’ generation. The ‘born free’ generation typically refers to those who were born after the end of Apartheid, or those who were coming of age after 1994. The youth, particularly in cities of the South, represent an excluded majority in terms of access to meaningful employment and quality living environments.

This article reflects on a research project which used narrative photovoice as a method to engage a group of 13 young people from Mitchell’s Plain, Philippi and Gugulethu; poor marginalised areas in Cape Town. Narrative photovoice combines photography with writing to give participants an opportunity to convey particular stories or issues through their photography. Through a process of co-production and collaboration between academic researchers, a community-based organisation (CBO) called ‘Youth for Change’ and a creative enterprise called ‘noDREAD’productions, the youth were engaged in a creative process using photographs to tell stories about themselves, their communities and the broader city context in which they live.

This article draws on Appadurai’s notion of the ‘capacity to aspire’ to make sense of the aspirations and dreams the participants talk about through their photographs; how they navigate structural, psychological and other factors which impede their aspirations and their freedom, and how they make sense of their everyday realities. The article advances two interlinked arguments: firstly, it makes visible the ‘navigational capacity’ of youth from marginalised neighbourhoods and their capacity to aspire amidst multiple constraints. It does so by illustrating how the youth grapple with the idea and experience of freedom in their everyday life. Secondly, it makes a case for the use of photovoice as a method that is well positioned to (a) capture the visual dimension of youth aspirations and (b) allow for co-production between the different stakeholders.

Keywords

Youth; Agency; Aspirations; Freedom; Hope; Choices

Introduction

Youth now make up a vast majority of people living in the Global South (Cooper et al. 2019). This youthful population find themselves in a context marked by deepening economic inequality, poverty and socio-spatial fragmentation, with cities being the primary sites where these conditions come to the fore. This article reflects on a research project aimed at exploring these issues amongst a group of young people in Cape Town, South Africa. Using Appadurai’s concept of the capacity to aspire, it reflects on how young people’s navigational capacity and agency are impacted by a severe lack of psycho-social and material resources in their immediate socio-economic environment and how they respond to these multiple challenges in their everyday lived environments. These structural impediments significantly impact the youths’ experience of freedom, and the article shows how they make sense of and navigate the varied dimensions of freedom in their daily lives. It also advances two interlinked arguments: firstly, it makes visible the ‘navigational capacity’ of youth from marginalised neighbourhoods and their capacity to aspire amidst considerable constraints. Secondly, it makes a case for the use of photovoice as a method that is well positioned to (a) capture the visual dimension of youth aspirations and (b) allow for co-production between the different stakeholders.

The Youth, Identity and the City project engaged thirteen youth from Mitchell’s Plain, Philippi and Gugulethu, poor marginalised areas in Cape Town, in a process of reflection and exploration using photography as a tool. This project was based on a collaborative partnership between a youth-based NGO called ‘Youth for Change’, a creative social enterprise ‘noDREAD’ Pty (Ltd) and an academic partner. This latest project stems from the continuation of a long-term partnership between ‘Youth for Change’ and Mercy Brown-Luthango, one of the co-authors of this article. Between 2012 and 2015, the researcher established a relationship with a CBO in Tafelsig, called the Tafelsig People’s Association (TPA), as part of an ongoing university-based research project that studies the relationship between upgrading of informal settlements and experiences and perceptions of violence and safety. Tafelsig is one of the poorest sections of Mitchell’s Plain, one of the biggest townships in Cape Town.

During this research project, the issue of youth and their experiences and perceptions emerged strongly as a theme needing further investigation. TPA decided to shift their strategic direction from a sole focus on housing struggles towards youth. They established ‘Youth for Change’, a CBO focused on youth development and indicated their desire for a research process which would assist them in gaining a greater understanding of some of the perceptions and experiences of youth in the area. Through this, the community-based partner directed the researcher towards the nexus of urban youth experiences, a topic which up until this point was not an explicit focus of her research. Based on this, Youth for Change and the researcher co-designed a pilot project that also involved two activist filmmakers as a means to connect with youth and their everyday lived realities. This project engaged ten young people from Tafelsig in a range of participatory activities and exercises including excursions to various historical places in the city. They also interacted with local artists and entrepreneurs hailing from the greater Mitchell’s Plain area who shared their life histories and imparted important lessons to the youth.

The program prompted the participants to reflect critically on their history, their place in the city and the challenges that they currently face, and to draw connections between these various elements. This culminated in the production of two short films, written and produced by the youth with guidance from the filmmakers (http://www.saferspaces.org.za/blog/entry/media-as-empowerment-for-youth-in-mitchells-plain). Each youth participant was given a copy of the films which they produced, and the films were shared with their family, friends and the broader community at a film screening in the local library in their neighbourhood.

The research project, on which this article is based, a follow-up to the initial youth-based project, sought to include youth from surrounding areas like Gugulethu and Philippi. This time around, Youth for Change and the researcher collaborated with ‘noDREAD’ Pty (Ltd), a creative social enterprise owned by the other author of this article. Whilst the foundational methodology and objective of the research remained the same, we used photography – rather than film-making – as a tool to encourage the youth to tell their stories.

To this end, we decided to use photovoice as a methodology. Whilst there is no consensus on what exactly photovoice means, the collective desire expressed by Youth for Change, noDread and the researcher was to allow the youth as much autonomy in driving the engagement as possible by allowing them to capture the images they wanted to capture, to choose the photographs they wanted to exhibit and tell the stories they wanted to tell about their photographs. The sections below provide a broader framing for the research project and describe in more detail the methodology that underpinned the co-production process and how this facilitated the process of deep reflection, learning and unlearning for us, as researchers, and the youth participants.

Co-production is a much-debated concept within disciplines such as planning, organisational management and the social sciences more broadly (Brown-Luthango & Arendse 2022). Here we think of co-production as a process which involves multiple actors that contribute their unique resources, knowledges and skills to the production of knowledge that is context-specific, context-sensitive and mutually beneficial. Whilst we do not believe that a co-production process of this kind, between a university partner and a community-based organisation, can ever be truly equal, given, amongst other factors, the imbalance in access to financial resources, the community-based partner in this instance could influence the direction and focus of the research to meet their needs at a particular time if there was mutual learning and reflection over the course of a collaboration spanning a number of years. The narrative photovoice methodology used for this project allowed the youth participants a great deal of autonomy to steer the creative process and the resultant products of the research.

The photographs and the narratives produced by the participants revealed several issues which they were concerned about. One of the main themes that was consistently highlighted, both in the individual and collective narratives, centred around the idea of freedom: what it means and how the idea of freedom, or being free, relates to their everyday lived realities.

This article first discusses Appadurai’s concept of the capacity to aspire and its relevance to the South African context. It then presents insights on the research process and shows how narrative photovoice can be used to capture youth aspirations in a more holistic manner. Finally, it discusses some key findings of the research, showing how youth from marginalised neighbourhoods in Cape Town navigate and negotiate their aspirations vis-a-vis complex social, spatial, economic and psychological challenges. It illustrates, through the participants’ photos and written work, how the youth wrestle with their perception of freedom, both individually and collectively, and the myriad factors that impact their aspirations for freedom.

Background and Context

Urbanisation is proceeding at a rapid speed in Asia and Africa. This is accompanied by growing informality, violence and insecurity as the delivery of basic services does not keep pace with the rate of urbanisation. The failure of neo-liberal economic policies and stagnant economic growth have seen an increase in poverty, inequality, economic precarity, rising unemployment and a shrinkage of social protection in many countries of the Global South. Youth live, by and large, in cities and towns, and according to UN Habitat, by 2030, 60 percent of all urban dwellers will be under the age of 18 (UN Habitat 2012). It is an unfortunate reality that the youth, particularly in cities of the South, still represent an excluded majority in terms of access to meaningful employment and quality living environments. Young people, specifically those between the ages of 15 and 34, bear the brunt of joblessness and insecurity, and in Africa constitute the largest share of those employed in the informal economy (UN Habitat 2013). Youth are concentrated in informal settlements or marginalised urban settlements, which means that they are disadvantaged in terms of access to basic services, such as water, sanitation and electricity, as well as public amenities, affordable and quality health care and educational infrastructure (UN Habitat 2013).

Like the rest of Africa, South Africa has a youthful population and its youth are particularly disadvantaged in terms of living conditions and professional opportunities. Amongst the 20.4 million young people aged between 15 and 34, 43.2 percent were unemployed during the first quarter of 2020 (Statistics South Africa Quarterly Labourforce Survey 2020). This was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in large-scale job losses. This precarity manifests in multiple socio-economic forms, such as violence, crime, lack of safety and poor health outcomes in terms of HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, as well as food insecurity, by which young people, particularly Black African and Coloured youth, are disproportionately impacted. Black African and Coloured are racial classification categories in South Africa, as are Indian and White.

The so-called ‘born free’ generation, those born after the advent of democracy or have come of age since 1994, represent a significant proportion of South Africa’s youth population. This term, coined by the media, imposes much expectation on this group. There is an assumption that, not being burdened by the shackles of Apartheid legislation, they would benefit from the many supposed opportunities that a post-Apartheid South Africa would afford them. This group is subject to stereotypes and is considered by some from the ‘struggle’ generation (those who lived through and experienced the period of Apartheid from 1976 onwards) to be ‘apathetic, apolitical, lazy and unaware of the history of struggle that made freedom and desegregation possible’ (Mpongo 2016). It has been argued that this term is imposed on young people by the media and certain sectors of society, and is one with which many young people in fact do not identify (Maimela 2014; Malila 2015; Malila & Garman 2016; Mpongo 2016; Vandeyar 2019).

Furthermore, young people are for the most part voiceless and invisible in mainstream media and many policy processes that report and make decisions about issues which concern them. Malila and Garman (2016), for example, found that only 8.5 percent of all education-related stories covered in the media included and considered the opinions and perceptions of young people. Research undertaken with participants from the so-called ‘born free’ generation find that many of them in fact do not feel free, and whilst they are not living under Apartheid, they still experience the psycho-social impact of the legacy of Apartheid and persistent spatial fragmentation and segregation, which prevent them accessing the spaces and opportunities which living in a democratic society should afford them (Maimela 2014; Malila 2015; Malila & Garman 2016; Mattes 2012; Mpongo 2016; Vandeyar 2019; Willmore et al. 2022). It is argued that freedom is multi-dimensional and political freedom experienced by ‘born frees’ is but one dimension of a larger dynamic of freedom and bondage (Vandeyar 2019, p. 466).

Much scholarly work has grappled with understanding the impacts of structural conditions on young people’s life chances, everyday lived experiences, their futures, and attainment of dreams and goals. This article draws on Appadurai’s concept of the capacity to aspire. The choice of this theoretical framing was informed by the ways in which the youth reflected on the notion of freedom and their capacity to aspire and make choices in a context marked by poverty, inequality of various kinds, drug abuse and high levels of interpersonal violence.

Youth Aspirations – Capacities and Constraints

Poverty, intergenerational deprivation, and the capacity to aspire

The relationship between poverty and the formation and attainment of aspirations, particularly among youth, has received much attention in scholarly work investigating young people. Aspirations are referred to as the ‘hopes, ambitions and drive to achieve certain goals’ (Ibrahim 2011). Ray (2003) argues that a two-way relationship exists between aspiration and poverty as poverty can inhibit the attainment of aspirations, which in turn can manifest in poverty. This is what is referred to as ‘aspirations failure’. Appadurai (2004) and others argue that aspirations are not formed or achieved in a vacuum, but are created, embedded and sustained within the social environment (Appadurai 2004; Ibrahim 2011; Jeffrey 2004; Ray 2003). Family, peer and other relationships within young people’s social context have considerable bearing on their aspirations. These are used to construct what the literature refers to as the ‘aspirations window’, which is defined as the ‘individual’s cognitive world and what is perceived as attainable’ (Ibrahim 2011, p. 5). An ‘aspirations gap’ exists when what is aspired to is not matched with the necessary resources (economic, social and other) available within young people’s social environment. Young people’s aspirations and goals are conditioned and shaped by the lifestyles, social and political norms, and economic position of others within their social environment. In a context of severe multi-dimensional, intergenerational poverty and deprivation, which is endemic to certain contexts within cities of the Global South, young people’s aspirations window can be narrow, constituting what Camfield et al. (2012) refer to as ‘aspirational inequalities’, which are closely connected to and conditioned by material and social inequalities.

It is important to note that the aspirations window is not only constrained by external limitations, but also internal psychological resources. Drawing on research in Northeast and Southern Thailand, Camfield et al. (2012) argue that the aspirations window of young people in the Global South is not only impacted by their immediate social environment, but also by the daily bombardment of images of wealth and the consumer culture from other parts of the globe, creating rising and unequally satisfying aspirations, as their own inability to secure meaningful employment make these unattainable. The authors observe that in this context, young people ‘adapt’ their aspirations by lowering their expectations, as a means of preserving psycho-social wellbeing.

This requires a careful and complex balancing of aspirations, strategies and action to make sense of and respond to their social environment and the obstacles they face in fulfilling their aspirations (Copestake & Camfield 2010). Appadurai uses the concept of navigational capacity, or an individual’s capacity to aspire, which he argues is not evenly distributed in society, but is very much dependent on the cultural tools, resources and networks, and the access to information which this enables. This has a class dimension as ‘the more privileged in any society simply have used the map of its norms to explore the future more frequently and more realistically, and to share this knowledge with one another more routinely than their poorer and weaker neighbors’ (Appadurai 2004, p. 69). Poverty, then, constrains the capacity to aspire and limits navigational capacity.

Another conceptual angle relevant to the research presented below is the nature of agency and how this intersects with the attainment of aspirations.

Agency, Freedom and Choice – More than meets the eye

Aspirations are linked to freedom and agency. Ibrahim (2011, p. 9) states that ‘aspirations are based on individuals’ freedoms to achieve the lives that they aspire to and their ability to use their human agency to effectively achieve these aspired lives’. However, human agency is itself socially conditioned by structural and institutional factors which impede freedom and choice, resulting in unfilled aspirations, powerlessness and frustration which, in turn, affects capabilities, resulting in what Ibrahim refers to as the intergenerational transmission of aspirations failure (ibid).

Scholars of social psychology have made a point of stressing the importance of internal belief systems and psychological agency in shaping youth’s perception of their aspirations window and, in turn, propelling them towards taking purposive action towards attaining their aspirations and goals (Bandura 2005; Banks 2015; Narayan-Parker 2005). This is what Narayan (2005) refers to as ‘the power within’. However, Klein (2014), reflecting on work done in Bamako, Mali, emphasises that psychological agency on its own is not a sufficient condition to move people closer to their desired outcomes. This must be supported by a ‘favourable opportunity structure’ and one’s sense and experience of power within this opportunity structure. There is, in fact, a dynamic interaction between psychological agency and the structural environment, which either constrains or enables action towards the realisation of dreams and aspirations (Klein 2004). Arguing for a more holistic and multi-dimensional conception of purposeful agency, Klein argues that ‘we need to see purposeful agency not just as the expansion of resources, the distribution of power, or the enlargement of decision-making ability, but also as the psychological power within that drives agents above and beyond their own socio-economic characteristics to make positive changes for their own lives and the community around them’ (2004, p. 21).

Drawing on developmental psychology, Banks (2015) alludes to the importance of a range of personal, family and community resources, both material and psycho-social, to the development and fulfilment of aspirations. She argues that ‘the accumulation of these factors – the development of a coherent sense of self, a range of core developmental assets and warm and supportive institutions and relationships – combine to influence young people’s ability or inability to build dreams, developing hopes and aspirations for the future that they then strive to meet” (Banks 2015, p. 3).

Given the lack of voice and invisibility of young people already alluded to by other youth scholars (Maimela 2014; Malila 2015; Malila & Garman 2016; Mpongo 2016;), this research used narrative photovoice as a method to give youth a voice and to listen and observe how they make sense of and navigate the structural conditions which impact their daily lives.

Methodology and the Research Process

In 2018 we embarked on a research project entitled ‘Youth, identity and the city’. To build a baseline understanding of young people’s perceptions and ideas around the key questions and concerns of the research, in-depth interviews were conducted with young people from Tafelsig in Mitchell’s Plain and young people from Philippi and Gugulethu at the start of the project. It became clear that many of the young people interviewed either struggled to or were reluctant to answer some of the questions posed during this interview process. The participants’ reluctance prompted exploration of more creative techniques and participatory methods, specifically the use of photography, to engage research participants. The research employed narrative photovoice as a method to understand how young people engage with their everyday social environment and navigate the myriad of challenges that they are exposed to in their everyday lives.

Photovoice (PV) is a collaborative, qualitative research method often used in community-based participatory research (CBPR) projects. The method was first developed by Wang and Yurris in the early 1990s and was used to study the reproductive health of Chinese women in Yunnan, China (Nykiforuk et al. 2011; Strack et al. 2014; Wang 2006). It has its theoretical foundations in the work of Paulo Freire, with its emphasis on critical dialogue and feminist theory, stressing the need for inclusion and participation of marginal voices in knowledge creation and sharing (Harley & Hunn 2015; Rose et al. 2016; Strack et al. 2014; Wang 2006; Wang et al. 2004). The photovoice method entails several distinct steps or phases, including a preparatory phase where participants are trained in aspects of photography and discuss issues around power and ethics. This is followed by the taking of photographs and a process where participants are encouraged to select the photographs that they want to display. This is accompanied by facilitated discussion about the photographs: why participants took specific photographs and their reasons for selecting these and not others.

Many scholars cite the benefit of the PV method for working with young people and eliciting their perspectives and experiences around sensitive issues in their everyday living environments that are sometimes difficult to verbalise, thereby amplifying marginalised voices (Gant et al. 2009; Harley & Hunn 2015; Nykiforuk et al. 2011; Vaughn et al. 2008). Here the combining of visual and narrative techniques to engage youth in a process of ‘meaning-making’, critical dialogue and knowledge co-production is of particular importance (Chanody et al. 2013; Simmonds et al. 2015; Zenkov & Harman 2009). One of the challenges or tensions in applying this method is around participation and control, and balancing of the interests of all role-players, including the participants, researchers and other community partners involved in the process (Chanody et al. 2013; Johansen & Le 2012; Rose et al. 2016). Researchers might begin with a set of preconceived research objectives and questions, but the photographs that participants take and select for reflection and the narratives which they construct around these might lead the research down a different path. Vaughn et al. (2008, p. 308) argue that photovoice ‘allows for participants’ voices to truly be heard and for a deeper understanding of how people make meaning in their lives rather than imposing a research objective upon a community, often with predetermined assumptions and outcomes’.

This requires that the researcher/s be willing to cede a greater level of control of the process and outcome to the participants. This is not always easy but can provide participants with a sense of ownership of the process and can generate new and different insights which might not have been possible to attain through traditional methods. However, this also requires a level of trust between all parties involved, based on long-standing relationships that have been built over time (Nykiforuk et al. 2011). The time and resource commitment required by photovoice methodology has been raised as one of the challenges of employing this method. These were tensions and issues that we also confronted in this research project.

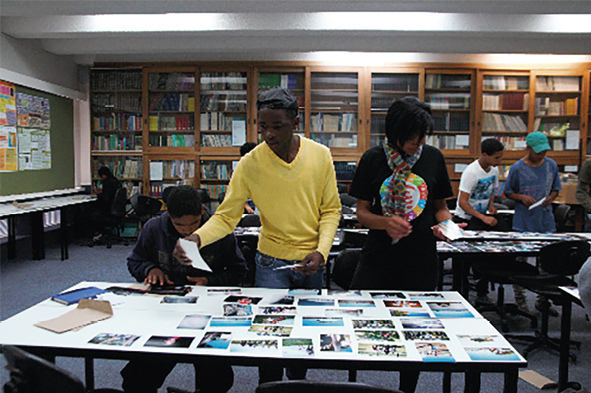

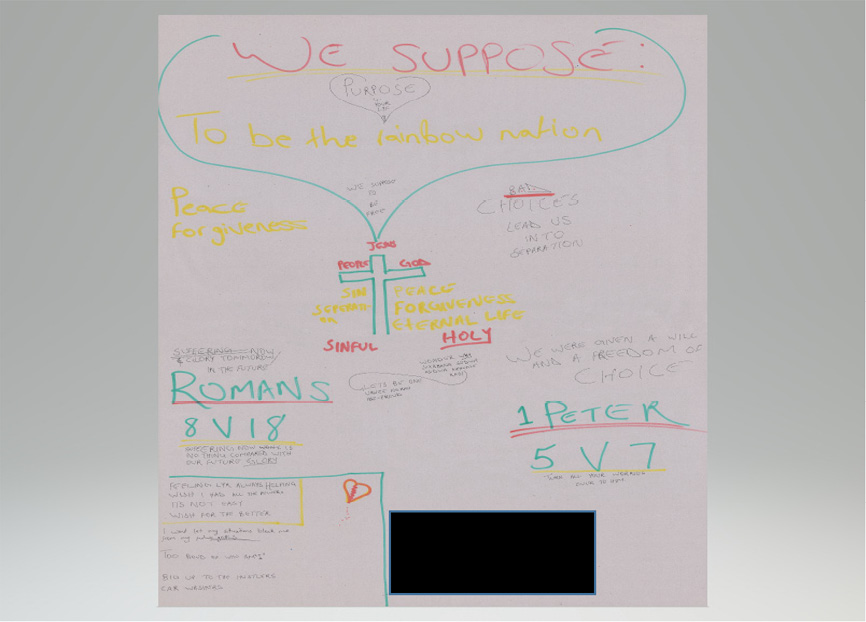

The process started with a series of seven workshops, which took place between September 2018 and December 2019, to involve the youth and slowly build a relationship and rapport. The first was a two-day workshop, which was aimed at drawing the young people into a process of self-reflection where they had to think about their personal identity and who they are in the spaces they live in, through a process of sharing their life stories with the rest of the group. During the first workshop, they also had to construct their personal asset tree and identify and share with the group their experiences, skills and knowledge (see Images 1 and 2). The personal asset tree encourages youth to think about their personal resources, skills and capabilities, and the exercise is aimed at encouraging the participants to understand themselves more deeply and to consider what capabilities they have.

Images 1 and 2. Participants introducing themselves and their asset trees

Images: Mercy Brown-Luthango, Cape Town, 18 September 2018

This was followed by an exercise in which they introduced their various communities to one another in an effort to build better understanding and allow the youth to think about and identify points of connection between themselves and across their communities. Important to note here is that, although these communities (Mitchell’s Plain, Philippi and Gugulethu) are located in physical proximity to one another, they are still socially distant due to the remnants of social engineering and racial segregation policies imposed under Apartheid. So, building better understanding and closing some of the social distance between members of the group was a desired outcome of all the processes.

The first workshop laid the foundation for the youth engagement process, which culminated in an exhibition, curated by the youth, as well as a photo book which they took the lead in creating. Drawing on the photovoice methodology, photography was employed as a research method because of its potential to engage the youth around topics and experiences which they might otherwise not feel free to talk about. At times it is difficult to convey understanding of our world through words or language. However, photography creates a different platform for uncovering the perspectives and truths relevant to the photographer. The images that are produced may allow the researcher to understand each perspective better, whereas language may fail to convey a specific message. The second workshop was the ‘Image vs Truth’ workshop, where the aim was to teach each participant a basic understanding of photography and the power of the tool in conveying messages through visual representation (see Image 3).

Image 3. First day of ‘Image vs Truth’ workshop

Image: Rosca van Rooyen, Cape Town, 27 September 2018

During the workshop, participants were provided with a basic understanding of a camera, lighting and visual symbols in photographs. They were also taught to understand visual cultural representation and misrepresentation in marketing techniques, and a basic understanding of posing and directing people to pose. In addition, they were exposed to photography ethics as they pertain to photographing people. This laid the foundation for their own photographic project. The project included both individual activities and moments of collective reflection; both of which were important to the overall process.

At the end of this workshop, each participant was provided with two disposable cameras. The brief was for them to use one camera to take photographs of their respective communities, both ‘good’ and ‘bad’ aspects of their social and built environment. The second camera was to be used to take photographs on their excursions to places of cultural and historical importance in the city (Robben Island, Castle of Good Hope, the Civic Centre in the Central City), which they visited as part of the project (see Images 4 and 5). The Castle of Good Hope is a fort which was built in the 17th Century during the Dutch occupation and Robben Island is an island in Table Bay, Cape Town where people of colour were imprisoned at different points during South Africa’s history. Inmates included those imprisoned for general crimes, as well as political prisoners like Nelson Mandela who were imprisoned for opposing the Apartheid regime. Here, the students were encouraged to photograph the similarities/connections between their social and/or built environment and the places they visited on their excursions. These two instructions allowed each participant to engage with their understanding of the built and social environments in the city and their ability to access various spaces in the city.

Image 4. Excursion to the Castle of Good Hope (a participant depicting the position that slaves were kept in during colonial times)

Image: Youth participant, Castle of Good Hope, Cape Town, 24 October 2018

Image 5. Excursion to Robben Island

Image: Youth participant, Victoria and Alfred Waterfront, Cape Town, 13 October 2018

This was followed up six weeks later by a second photography workshop, ‘Curating your Voice’, where each participant had to look at all their photographs and then choose the 10 photographs that best represented the personal narratives of their communities and any connections to different neighbourhoods visited (see Image 6). Once participants had chosen their photographs, in-depth interviews were conducted with each participant to gain an understanding of why they had chosen those particular photographs and the messages they wished to convey.

Image 6. Participants choosing their 10 favourite photos

Image: Kirsten Warries, University of Cape Town, 28 July 2021

Image 7. Exhibition curated by youth participants

Image: Mercy Brown-Luthango, University of Cape Town campus, 5 December 2019

The next part of the process was a full-day workshop, Exhibit, where the youth started working on the curation of their photographs and the exhibition. This was preceded by training provided by one of the facilitators, with the assistance of a local visual artist, in the technical and entrepreneurial aspects of curation, which included the process of writing an artist statement and exhibition and photograph titles.

During this activity, the participants had to narrow their choice of photographs down to five out of the ten photographs from the previous workshop, and begin writing the title of their photo essay, titles of each photograph, artist statements, and symbols that best represented their work. Through this process, the youth constructed an individual narrative for each of the five photos they had chosen.

The fourth element in the process was a workshop, held at the University of Cape Town, where participants had to start the process of creating one cohesive curated exhibition out of the individual photo essays. Here the focus shifted from the individual to the collective, and drawing connections between personal perceptions of the narrative. During this process, participants looked at and read each participant’s photo essay and then attempted to seek commonalities. The aim was to create cohesion in the exhibition and experience to curate a collective narrative. The workshop was mostly to allow the participants to discuss and negotiate amongst each other how they would bring all participants’ ideas and messages together and find a cohesive curatorial statement and overall title for the exhibition. This provided balance between the individual and the collective voice, which can often be a challenge in photovoice projects (Chanody et al. 2013; Johansen & Le 2012; Simmonds et al. 2015; Zenkov & Harman 2009). The final activity in this process was the set-up and launch of the exhibition, so that the youth could celebrate their work and showcase it to their families, friends and members of the public.

The interviews, group discussions, photographs, individual and collective stories about the photographs, curatorial statement, individual participant journals and various engagements with the youth over the course of this journey provided rich material, which formed the basis for this article. The participants were given journals at the start of the process, during the first workshop, and were encouraged to write down their personal reflections and/or capture drawings throughout the process. The theme of freedom and what this looks and feels like emerged as a central concern, amongst several other themes. These themes included the idea of hope and maintaining hope amidst their everyday struggles, the idea of hustling and making do, grappling with substance abuse and gang violence, and how to improve their communities. For the purposes of this article, the focus will be on freedom and how participants maintain hope in the face of limited freedom. These themes are presented and discussed below.

Freedom – As Expressed and Experienced by the Youth

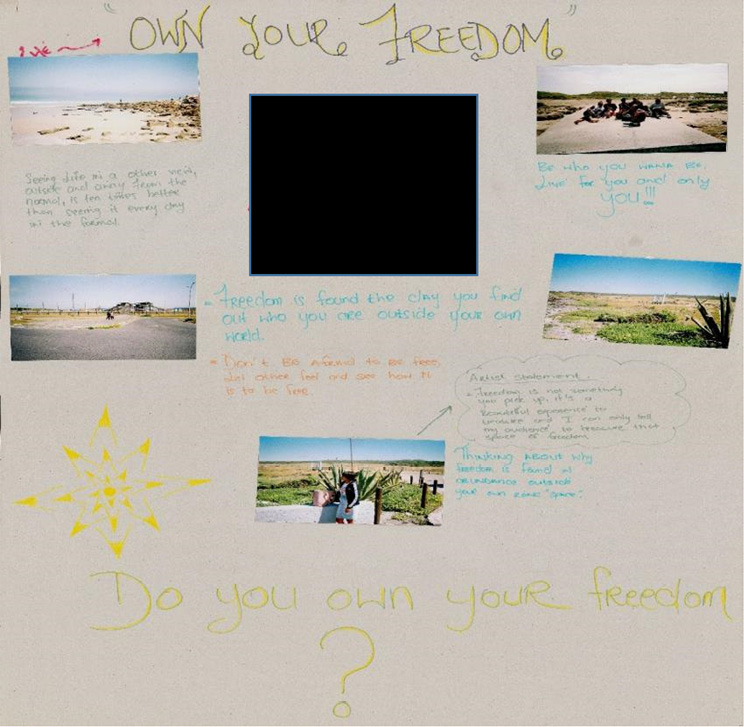

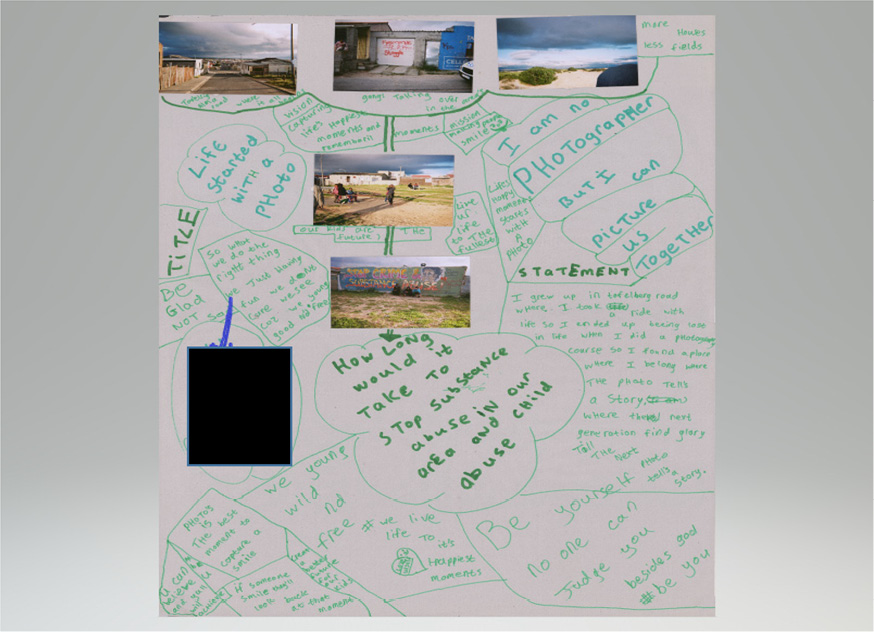

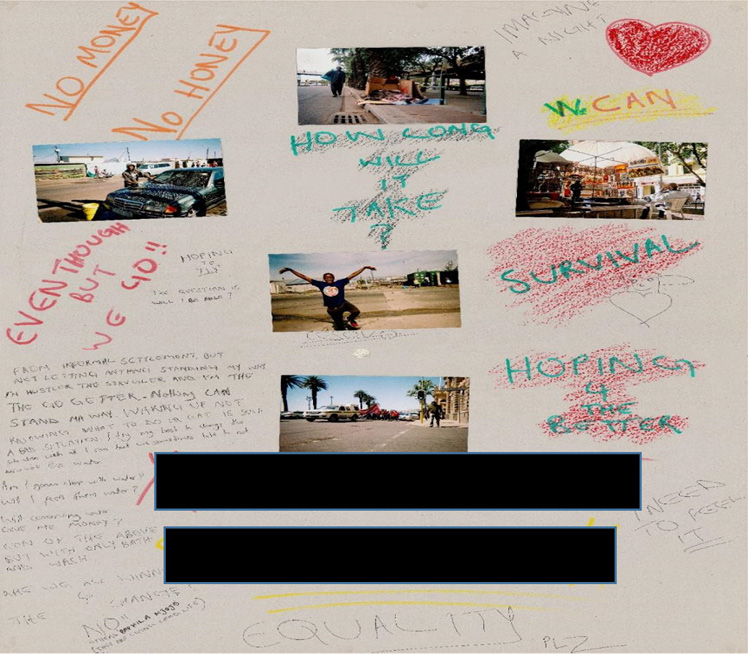

This section provides an overview of the main ideas expressed by the youth in relation to how they understand and experience freedom in their everyday life. Here we present four of the youths’ visual essays which speak to the notion of freedom, how they understand and navigate different structural impediments to freedom and their hope for the future.

Visual Essay 1 – Own your freedom

Visual Essay 1 was created by a twenty-three-year-old young woman from Tafelsig, Mitchell’s Plain, and describes what freedom means to her. The poster presented here combines photographs taken on Robben Island (three landscape pictures, one group picture and one distant portrait of the author herself). What emerges strongly from this presentation is that her idea of freedom is centered around her experience of leaving her neighbourhood and visiting Robben Island which, ironically, was a space where she felt free. The author stresses the importance of this physical displacement in her artist statement: Freedom is found the day you find out who you are outside your own world. The title given to the last photograph, a portrait where she poses meditatively against the desert landscape of the island, is even more explicit: Thinking about why freedom is found in abundance outside your own zone, space. With this sentence, she directly suggests that she does not feel free in her neighbourhood. What this visual essay shows is that freedom only starts to gain meaning once it is actually experienced and that the meaning of freedom comes from a physical experience of both displacement and reflection. Visual Essay 2, prepared by a young man who lives in the same neighbourhood as this young woman, also speaks poignantly to the idea of space and how the experience of freedom, both physically and socially, is connected to the spaces we inhabit.

Visual Essay 2 – Life started with a photo

Visual Essay 2 was created by a young man who lives in Tafelsig, Mitchell’s Plain. He chose to exhibit five photographs from his neighbourhood. These photographs speak powerfully to themes of housing access, gangsterism, substance abuse and crime. The Tafelsig community has been involved in a long struggle for access to housing. A photo of a vacant field, which often becomes the site for gang fights, is captioned more houses, less fields. Another of a road, Alma Road in Tafelsig, which was the site of an informal settlement community’s struggle for housing, is captioned Tafelsig, Alma Road, where it all begins.

The other three photos reflect the participant’s deep concern for the challenges of gangsterism (gangs taking over in the area – in reference to a photograph of graffiti to mark gang territory), substance abuse and child abuse, and how these impact on the future of the children – our kids are the future, create a better future. A photo of three young boys next to a mural created by the community, he captioned how long would it take to stop substance abuse and child abuse in our area? This statement expresses a weariness with the perpetual nature of these intractable challenges. However, at the same time the participant encourages himself and others to be yourself, no one can judge you, beside God, be you. Interestingly, he expresses much excitement about the power of a photo or photography to ‘tell stories, capture happy moments, to capture a smile and when someone looks back at that picture, they can smile’. This illustrates the value of PV as a participatory method which stimulates deep reflection and the surfacing of hidden feelings and ideas.

Visual Essay 3 – No money, no honey

Visual Essay 3 was created by a twenty-five-year-old young man who lives in an informal settlement in Philippi, one of Cape Town’s poorest neighbourhoods. Visual Essay 3 contains five photos depicting economic precarity and efforts to secure a livelihood in his neighbourhood and the inner city. A photo of a young man washing a car in his neighbourhood is entitled no money, no honey, playing on the notion that without money it is very difficult to attain certain aspirations. The pictures and narratives in Visual Essay 3 depict the participant wrestling with his daily struggles to access basic services like water and sanitation whilst trying to maintain hope for a better future.

When asked about his perceptions of the ‘city’ and the area where he lives during an excursion to the central city, the same participant remarked ‘Kosovo is not Cape Town’. Kosovo is the name of the informal settlement where he lives. Although Kosovo is located in Cape Town, for this participant it seems far removed from all that the ‘city’ represents. He spoke at length about the dreams he had about Cape Town when he moved from his rural home. However, now he feels that there is no difference between Kosovo and where he comes from, because in both places he does not have access to basic amenities like water, electricity and sanitation, and he struggles to find employment. He relates his daily lived reality to broader struggles for economic freedom in his pictures of a service delivery march (entitled ‘hoping for the better’) and an informal trader (entitled ‘survival’) in the central city. This visual essay also reflects a sense of stretching, expressed in the question: ‘how long will it take?’ next to a photo of homelessness and the statement: ‘hoping to fly, the question is, will I be able to do it’ next to a photo of himself. This sense of stretching corresponds to sentiments expressed by the young man from Tafelsig in Visual Essay 2.

Visual Essay 4 – We suppose to be the rainbow nation

Visual Essay 4 is a continuation of the young man’s narrative in Visual Essay 3, where he relates his personal struggles and those of others to the idea of the rainbow nation and all the promises that were supposed to accompany political freedom, obtained in 1994. This same youth now rationalises his disappointment about the promise of the rainbow nation and its associated freedom(s) by reverting to biblical scriptures, and notes that suffering now does not compare to our future glory and we were given a will and a freedom of choice. The issue of faith also features in the visual essays of other participants as well, for example one participant narrated in great detail his journey of trying to become a religious leader.

The idea of choices and the freedom to make the right choices was a theme that the participants chose to carry into their collective curatorial statement and the title of the exhibition.

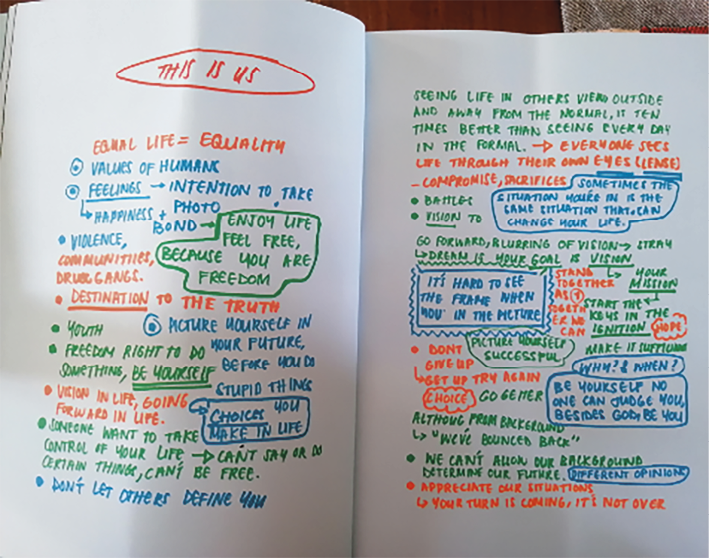

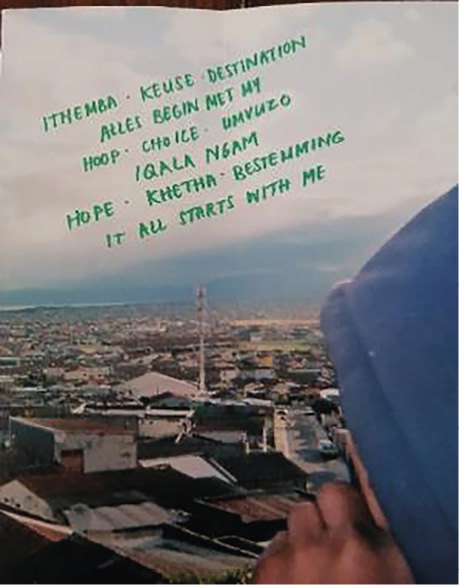

Participants’ Curatorial Statement – ‘This is us’

The above photographs are taken from the photobook which reproduced the participants’ original artist statements and the title for the exhibition, which they collectively came up with during the second last workshop. During this workshop participants had in-depth discussion and constructive back and forth between their individual narratives and what they wanted to present as a collective statement during the exhibition. The different languages (English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa) in which the exhibition title was written express the participants’ desire to ensure inclusion and celebrate their different cultural identities. The artist statement and the title of the exhibition provide a window into how our participants understand their own agency as they struggle with notions of freedom, choice, and the idea of control over the kind of choices they can make in the everyday, given structural and other obstacles which constrain their freedom and their ability to make good choices. These statements express a sense of ‘wrestling’ that many of the participants experience with the idea of freedom. Participants expressed the belief that they were free, free to make their own decisions, yet at the same time they feel that they are not free to make good choices and attain their goals. This is captured in statements such as:

Own your freedom, just be yourself, don’t let others define you

Enjoy life, feel free, because you are free

Freedom, right to do something, be yourself

The idea and perception of freedom was strongly tied to the ability to make good, constructive choices, and participants seemed to feel constrained in their ability to make such choices. There was an appreciation of the importance of making good choices in life; for example, the choice to engage in substance abuse or not, to join a gang or to stay in school. However, there was again, a realisation of how the socio-economic environment made it very hard to make good choices all the time.

Picture yourself in your future before you do stupid things

Choices, you make in your life

There was the idea of ‘lenses’ (‘lense’, in Afrikaans) – that your freedom depends on your view of the world, your view of the situation that you find yourself in, but your vision too is constrained by your social environment:

Everyone see life through their own eyes (lense)

Picture yourself successful

It’s hard to see the frame, when you are in the picture

Going forward, blurring of vision – stray, dream is your goal, is your vision

What does this mean for the capacity of these young people to aspire and the size of their aspirations window? The work of Appadurai and others on the social embeddedness of aspirations and the impact of material conditions and psychological agency on the formation and attainment of aspirations is relevant in this context. The stories told by the youth through their photographs and artists’ statements resonate with Ibrahim’s (2011) arguments that aspirations are conditioned by freedom and that agency is shaped by structural and institutional factors which impede freedom and choice. In this context, it can be argued that our participants’ desire for freedom transcends their own immediate personal freedom, also reflecting a deep desire for greater societal transformation which would enable young people to dream and pursue their ambitions and to make good choices. These young people have a deep understanding of how persistent and intractable socio-economic and spatial inequalities constrain their aspirations window. They are aware that their own freedom is closely tied and connected to a broader structural transformation which is yet to be realised, despite the political transition which occurred in South Africa in 1994. This is perhaps captured in Image 4 above, where one of the participants during a visit to the Castle of Good Hope put himself in the chains which slaves were held in during colonial times.

This group of young people in fact possess strong psychological agency. This enables them to face the manifestations of material inequalities and intergenerational deprivation on an everyday basis yet remain hopeful and press forward. However, Klein’s (2014) observation that psychological agency on its own is not a sufficient condition to move people closer to their desired goals holds true.

This psychological agency, despite an acknowledgement of their lack of freedom and limited choices, is rooted in strong social ties and faith (as depicted in Visual Essay 4). Hope is linked to the idea of lenses and ‘agency’ – making good choices – which in turn is connected to power and control. This hope is also linked to a conscious focus on the future and the desire to create a better future for themselves and others in their community. This is what motivates them to keep going, ‘even though, but we go’, despite their awareness of structural conditions which constrain their spatial and socio-economic freedom.

Conclusion

This article reflects on a research study which engaged young people on their perceptions and experiences of living in a city, using narrative photovoice as a method. It was based on a long-standing relationship between the researcher and a community-based organisation.

The methodology employed in this study provided the youth with the tools to enable them to step in and outside the frame of their lives and to observe at a critical distance. The act of taking photographs and taking a step back to examine why they took a particular picture and what story they wanted to convey, while moving between their neighborhoods and other areas in the ‘city’, enabled critical reflection and meaning making. This gave us a window into how young people make sense of these different social environments, their everyday struggles, and their own agency and aspirations. This ability to take critical distance, stay at a critical distance, is often reflected in the PV literature as one of the important goals and outcomes of this methodology. However, this mostly applies to participants. The literature hardly speaks about the impact of the PV methodology on the researchers and their own process of reflexivity. The young people’s practice of reflection and moving in and out of the frame also challenged us, as researchers, to embark on a process of self-reflection.

They also challenged us to change our lenses, put ourselves in the frame and change our filters, and to rethink and interrogate concepts that we use and take for granted in an uncritical way, because of the perspectives we hold, based on our location, position and the spaces we occupy. How useful are concepts such as aspiration, freedom, choice and agency in the context in which these young people find themselves? To this group of young people, most of whom are not in employment or in education, their most immediate aspiration is not based on idealised Western-based notions of success, but their idea of freedom and the ability to make good choices. This is interesting, given that in the South African context, these young people are part of the ‘born free’ generation, born after the end of Apartheid. Yet, they do not consider themselves to be free as their social, economic and physical mobility is heavily constrained by persistent poverty and economic and spatial inequality. This study contributes to research which engages with young people and allows them to speak in their own voice about their daily lived experiences within a democratic South Africa, what freedom means to them, and how they make choices and maintain hope in an environment where there is very little which distinguishes their world from that which previous generations encountered under Apartheid.

Mattes (2012) argues that the picture which ‘born frees’ experience in post-Apartheid South Africa is one of ‘continuity, even regression, rather than a sharp generational break/change from the past’. Our research shows that the youth we worked with are actively trying to make sense of the varied dimensions of freedom and how these manifest in their daily lived experiences. Whilst acknowledging the political and legislative freedom obtained post-Apartheid, they are under no illusion about how this has not translated into economic freedom or widened their aspirations window. Our engagement with the youth, however, reveals strong psychological agency and navigational capacity in the midst of structural barriers. This is fueled by faith and spirituality, as well as strong family and community connections, which enable them to remain hopeful.

References

Appadurai, A 2004, ‘The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition’, in Culture and Public Action, Vijayendra Rao and Michael Watson (eds), Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, pp. 59–84.

Bandura, A 1998, ‘Personal and collective efficacy in human adaptation and change’, Advance in Psychological Science, vol. 1, Psychology Press, UK, pp. 51–71.

Banks N, 2015, ‘Understanding youth: Towards a psychology of youth poverty and development in Sub-Saharan African cities’, Working Paper 216, Brooks World Poverty Institute (BWPI), The University of Manchester, United Kingdom, pp. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2704451

Camfield, L, Masae A, McGregor A & Promphaking B 2012, Cultures of aspiration and poverty? Aspirational inequalities in Northeast and Southern Thailand, Working Paper 38, The School of International Development, University of East Anglia, pp. 1–35.

Cooper, A, Swartz, S & Mahali, A 2019, ‘Disentangled, decentered and democratized: Youth studies for the Global South’, Journal of Youth Studies, vol. 22, pp. 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2018.1471199

Copestake, J & Camfield, L 2010, ‘Measuring multi-dimensional aspirational gaps: A means of understanding cultural aspects of poverty’, Development Policy Review, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 617–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2010.00501.x

Gant, L, Shimshock, K, Allen-Meares, P, Smith, L, Miller, P, Hollingsworth, L & Shanks, T 2009, ‘Effect of Photovoice: Civic engagement among older youth in urban communities’, Journal of Community Practice, vol. 17, pp. 358–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705420903300074

Harley, C & Hunn, V 2015, ‘Utilisation of photovoice to explore hope and spirituality among low-income African American adolescents’, Child Adolescent Social Work Journal, vol. 32, pp. 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-014-0354-4

Ibrahim, S, 2011, ‘Poverty, aspirations and wellbeing: Afraid to aspire and unable to reach a better life – voices from Egypt’, BWPI Working Paper 141, Creating and sharing knowledge to help end poverty, Brookes World Poverty Institute. ISB 978-1-907247-40-8, p1-23

Johansen S & Le T 2012, ‘Youth perspectives on multi-culturalism using photovoice methodology’, Youth and Society, vol. 46, no. 4, pp. 548–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X12443841

Jeffrey, C & McDowell, L 2004, ‘Youth in a comparative perspective: Global change, local lives’, Youth and Society, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 131–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X04268375

Klein, E, 2014, ‘Psychological agency: Evidence from the urban fringe of Bamako’, Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), Working Paper 69, University of Oxford, pp. 1–29. ISBB 978-19-0719-456-6

Malila, V 2015, ‘Being a born free’: The misunderstanding and missed opportunity facing young South Africans, Last Word, RJR 35.

Malila, V & Garman, A 2016, ‘Listening to the born free: Politics and disillusionment in South Africa’, African Journalism Studies, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2015.1084587

Mattes R 2012, ‘The “born frees”: the prospects for generational change in post-apartheid South Africa’, Australian Journal of Political Science, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 133–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2011.643166

Mpongo, S 2016, ‘The born free generation’, visual essay, Anthropology Now, vol, 8, no. 3, pp. 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/19428200.2016.1242919

Narayan-Parker, D (ed.) 2005, Measuring empowerment: Cross-disciplinary perspectives, World Bank Publications, Washington. https://doi.org/10.1037/e597202012-001

Nykiforuk, C, Vallianatos, H & Niewendyk, L 2011, ‘Photovoice as a method of revealing community perceptions of the built and social environment’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 103–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691101000201

Ray, D 2003, Aspirations, poverty and economic change, New York University and Instituto de Análisis Económico (CSIC).

Rose, T, Shdaimah, C, deTablan, D & Sharpe, T 2016, ‘Exploring well-being and agency among urban youth through photovoice’, Children and Youth Services Review, vol. 67, p. 114–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.04.022

Simmonds, S, Roux, C & ter Avest, I 2015, ‘Blurring the boundaries between photovoice and narrative enquiry’: A narrative photovoice methodology for gender-based research’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691501400303

Statistics South Africa 2020, Quarterly Labourforce Survey 2020, Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

Strack, R, Magill, C & McDonagh, K 2014, ‘Engaging youth through Photovoice’, Health Promotion Practice, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 4–-58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26735303 https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839903258015

UN Habitat 2012, ‘State of the urban youth – youth in the prosperity of cities: Overview and summary of findings’, UN Habitat, Nairobi.

UN Habitat 2013, ‘Cities of youth: Cities of prosperity’, United Nationals Human Settlement Programme, UN Habitat, Nairobi.

Vandeyar, S, 2019, ‘Unboxing the “born-frees”: Freedom to choose identities’, Ensaio: aval. pol. públ. Educ., Rio de Janeiro, vol. 27, no. 104, pp. 456–75, July/September. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-40362019002702196

Vaughn, L, Rojan-Guyler, L & Howell, B 2008, ‘A photovoice pilot of Latina girls’ perceptions of health’, Family Community Health, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 30516. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.FCH.0000336093.39066.e9

Wang, C, Morrell-Samuels, S, Hutchison, P, Bell, L & Pestronk, R 2004, ‘Flint PV: Community building among youth, adults and policymakers’, American Journal of Public Health, vol. 94, no. 6, pp. 911C20. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.6.911

Wang, C 2006, ‘Youth participation in Photovoice as a strategy for community change’, Journal of Community Practice, vol. 14, nos 1–2, pp.147–61. https://doi.org/10.1300/J125v14n01_09

Willmore, S, Day, R, Roby, J & Maistry S 2022, ‘Ubuntu among the born frees: Exploring the transmission of social values through community engagement in South Africa’, International Social Work, pp. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/00208728221086151

Zenkov, K & Harman, J 2009, ‘Picturing a writing process: Photovoice and teaching writing to urban youth’, Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, vol. 52, no. 7. pp. 57584. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.52.7.3