Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 14, No. 2

December 2021

RESEARCH ARTICLE (PEER-REVIEWED)

Harnessing the Power of Stories for Rural Sustainability: Reflections on

Community-Based Research on the Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland

Brennan Lowery1, Joan Cranston2, Carolyn Lavers3, Richard May4, Renee Pilgrim5 and Joan Simmonds6

1 Postdoctoral Researcher, School of Science and Environment, Grenfell Campus of Memorial University, St. Anthony, NL, Canada

2 Coordinator, Bonne Bay Cottage Hospital Heritage Corporation, Norris Point, NL, Canada

3 Port au Choix, NL, Canada

4 Executive Director, Nortip Development Corporation, Bird Cove, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada

5 Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioner and Acupuncturist, St. Anthony Bight, NL, Canada

6 Manager, French Shore Historical Society, Conche, NL, Canada

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v14i2.7766

Article History: Received 15/06/2021; Revised 18/10/2021; Accepted 25/10/2021; Published 12/2021

Abstract

Stories have the power to shape understanding of community sustainability. Yet in places on the periphery of capitalist systems, such as rural and resource-based regions, this power can be used to impose top–down narratives on to local residents. Academic research often reinforces these processes by telling damage-centric narratives that portray communities as depleted and broken, which perpetuates power imbalances between academia and community members, while disempowering local voices. This article explores the potential of storytelling as a means for local actors to challenge top–down notions of rural sustainability, drawing on a community-based research initiative on the Great Northern Peninsula (GNP) of Newfoundland. Five of the authors are community change-makers and one is an academic researcher. We challenge deficiencies-based narratives told about rural Newfoundland and Labrador, in which the GNP is often characterised by a narrow set of socio-economic indicators that overlook the region’s many tangible and intangible assets. Grounded in a participatory asset mapping and storytelling process, a ‘deep story’ of regional sustainability based on community members’ voices contrasts narratives of decline with stories of hope, and shares community renewal initiatives told by the dynamic individuals leading them. This article contributes to regional development efforts on the GNP, scholarship on sustainability in rural and remote communities, and efforts to realise alternative forms of university-community engagement that centre community members’ voices and support self-determination.

Keywords

Rural Development; Sustainability; Storytelling; Community-Based Research; Self-Determination; Newfoundland and Labrador

Introduction

Stories are uniquely powerful in shaping our understanding of community sustainability. Yet, in rural and natural resource-based regions, this power can be used to question community viability (Bebbington 1999), reinforcing uneven capitalist development patterns (Kühn 2015). Furthermore, academic research often tells damage-centric narratives that portray communities as depleted and broken (Tuck 2009), rather than foregrounding local ways of knowing (Christensen, Cox & Szabo-Jones 2018) and acknowledging the holistic value of community assets (Winkler et al. 2016).

Rural coastal communities in Newfoundland and Labrador (NL), Canada, are often cast as victims in the story of the 1992 fisheries collapse that shook the province’s foundations (Davis 2014). In particular, the Great Northern Peninsula (GNP) is often associated with high rates of population ageing and youth out-migration (Roberts 2016; Simms & Ward 2017). However, these narratives overlook the GNP’s many assets, such as natural resources, social cohesion and cultural heritage (Parill et al. 2014). In both the GNP and other rural regions, the value of these assets is often under-recognised in traditional economic development models (Arias Schreiber, Wingren & Linke 2020), overlooking the diverse resources available to communities to start a ‘spiraling up’ of vitality (Emery & Flora 2006) and excluding rural communities from the story of change towards sustainability.

In this article, we explore the potential for communities to use storytelling to challenge top–down narratives of rural sustainability. We contribute to scholarship on the role of storytelling in sustainability transition (Veland et al. 2018), including how ‘deep stories’ can motivate social action (Hochschild 2016) and how rural and resource-based communities are often excluded from dominant sustainable development narratives (Lowery et al. 2020). We also demonstrate an alternative relationship between rural communities and academia in describing our co-creative process as an author team including an academic researcher and community change-makers from the GNP. Reflecting on power in our process, we acknowledge how university-community engagement often perpetuates colonial patterns of extraction (Walker et al. 2020) and thus seek to centre community members’ voices and share power in the research process. Our research question is: how can storytelling enable communities on the GNP to challenge top–down narratives of rural sustainability, and what lessons can be learned for engaged research on the role of stories in power, self-determination and community sustainability?

Conceptual Approach

We approach community sustainability as a holistic agenda balancing global goals, such as climate action, gender equity and food sovereignty (United Nations 2015) with community-level priorities (Bridger & Luloff 1999). However, in regions made peripheral relative to centres of power and wealth (Kühn 2015), it may be more appropriate to approach sustainability by ‘[starting] with what is strong, instead of what is wrong’ (Russell 2016). We draw from Asset-Based Community Development, painting a ‘glass half-full’ portrait of community sustainability that can be especially appropriate for marginalised communities (Kretzmann & McKnight 1993). We also consider notions of ‘diverse economies’, acknowledging the value of self-provisioning, volunteering, social enterprise, and other activities on the fringes of capitalist exchange (Arias Schreiber et al. 2020). In this broader conception of value, intangible assets, which often are not measured by mainstream sustainability indicators (Ramos 2019), can be harnessed to trigger a ‘spiraling up’ of community wellbeing, combining interdependent forms of social, natural, economic, cultural and human capital (Emery & Flora 2006).

In search of inclusive visions of community sustainability, we highlight the potential of storytelling. Oral history, ethnography and Indigenous methodologies have often used storytelling to foreground the knowledge of marginalised peoples (Christensen, Cox & Szabo-Jones 2018; Ritchie 2014). Similarly, cultural planners have acknowledged the importance of narratives as one of ‘multiple epistemologies’, whereby oral histories can be used to identify diverse cultural assets (Ashton, Gibson & Gibson 2015), but are often silenced by Western knowledge systems (Young 2008). Policy researchers have also highlighted how tropes like the ‘rags to riches’ stories or tales of a lost Golden Age can shape collective understanding of planning proposals (Sandercock 2005), and how actors use political myths to explain current struggles in relation to an imagined past (Bottici & Challand 2006). Similarly, the ‘deep story’ concept reveals how the latent frustrations of disenfranchised groups can be manipulated to fuel xenophobic social movements (Hochschild 2016). In contrast, storytelling may be a tool for mobilising citizens around an inclusive sustainability agenda that motivates action across a broad audience (Veland et al. 2018).

Yet, research often tells an urban-centric story in which rural and natural resource-based communities play no part in sustainability transitions (Lowery et al. 2020). Inheriting Western cultural narratives that equate urbanity with modernity and progress, sustainable development research and practice often overlook differences between rural and urban contexts (Markey, Connelly & Roseland 2010), or even disparage resource-based livelihoods as antiquated and unsustainable (Hall & Donald 2009), while undervaluing community assets that remain after disruptions like boom and bust cycles (Winkler et al. 2016). For rural and resource-based communities to tell their own sustainability stories, community members must articulate unique visions for local wellbeing while aspiring to an inclusive agenda that reflects global priorities.

Rural Sustainability Narratives on the Great Northern Peninsula

Since I was a child, I’ve driven the peninsula, always going somewhere else…I was back and forth the peninsula to the airport, the university, back from vacations. I left home when I was 17. And that peninsula was just a throughway. It was just a way to get through. And it was always beautiful, but I never stopped anywhere to appreciate it. I didn’t explore any of it because I was always trying to get somewhere else.

Renee Pilgrim, resident of St. Anthony Bight

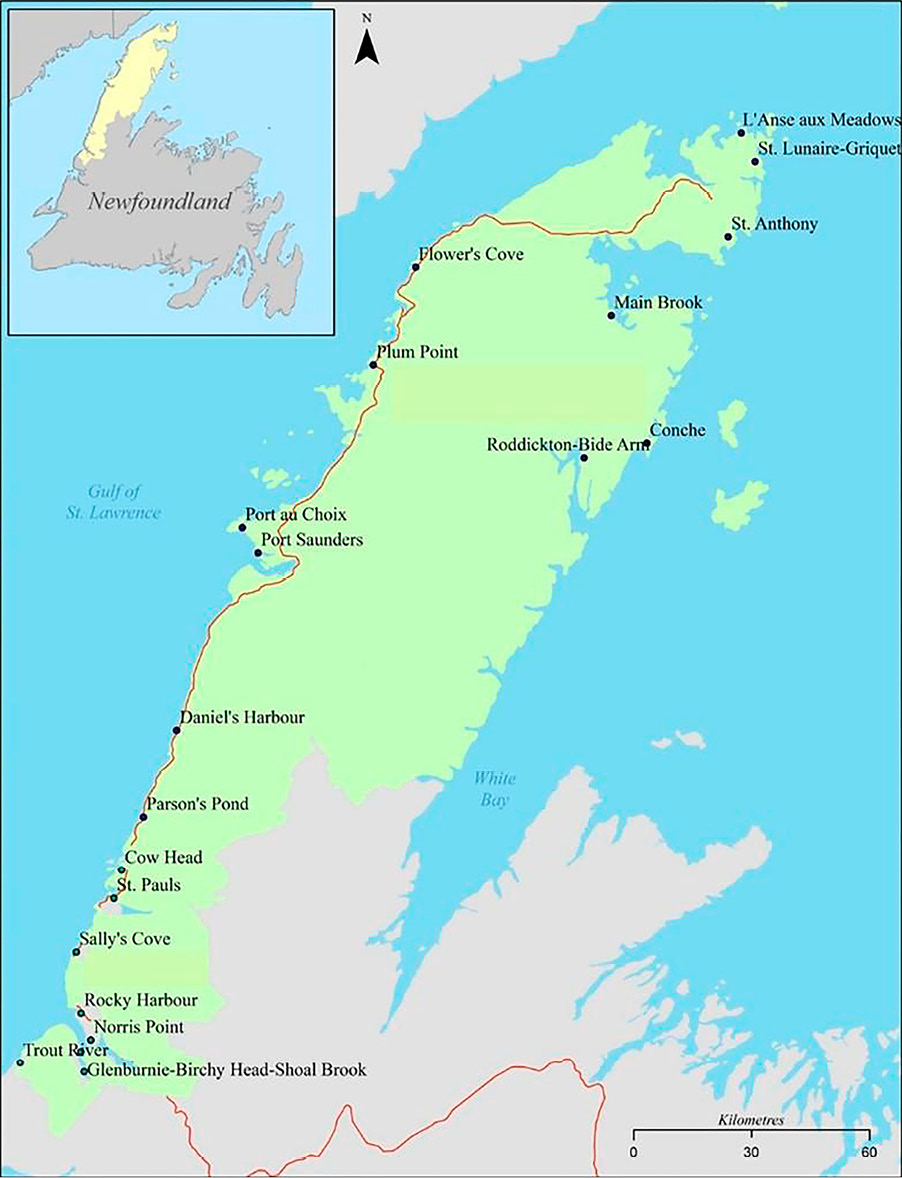

The GNP is home to 69 communities spread across 17,483 km2 on the northwestern tip of Newfoundland (Gibson 2014). The region has a rich heritage of Indigenous and settler cultures, including Maritime Archaic peoples, North America’s only Viking settlement (Parks Canada 2021 a, b), and intersecting English, Irish, Mi’kmaq and French identities. Its 2016 population was 15 485 people, including the largest community of St. Anthony (2255), with the nearest city, Corner Brook (19 547), a 2–5 hour drive to the south.

Figure 1. Map of the Great Northern Peninsula

However, in popular and academic discourse, the GNP and other rural NL regions often are discussed not for their assets, but their challenges. Rural coastal communities were devastated by declining cod stocks in the late 20th century and resulting federal moratorium in 1992 (Davis 2014). Today, influential voices use socio-economic indicators to tell a negative story about rural NL, highlighting the province’s economic uncertainties to justify withdrawing public services from rural regions. When releasing the 2021 provincial budget, Finance Minister Siobhan Coady stated that ‘solutions are needed to address long-standing structural issues, such as the high cost of providing services to nearly 600 communities across a large geography, chronic deficits, dependence on volatile oil revenues, as well as a declining and aging population’ (Antle 2021, para. 11).

Hit hard by the moratorium, the GNP continues to experience rapid demographic decline, losing 7.1 per cent of its population between 2011 and 2016 (Community Accounts 2020). Media and academic attention focuses on these trends; for example, a report by Memorial University (MUN) researchers predicted that the GNP’s population could shrink by up to 40 per cent by 2036 (Simms & Ward 2017). Similarly, Roberts (2016, para. 5) concluded: ‘[t]hat’s the story of the Northern Peninsula: heavy youth out-migration; one of the oldest median ages in the country; an economic base teetering on the brink’. Although these assessments may make for eye-catching journalism or compelling research, they impose top–down narratives on to the GNP, privileging expert knowledge over that of rural residents. Furthermore, these narratives fail to acknowledge the very assets that communities can harness to reverse these trends.

Community-Engaged Research Methods

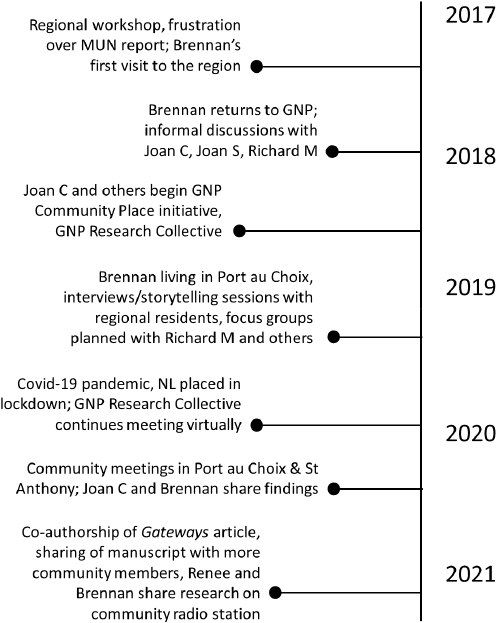

This article portrays a story of community-engaged research that both reflects and challenges power relations between rural communities and academia. As the academic author, I draw on my PhD work in the first person singular (‘I’). This research would not have been possible without the knowledge and guidance of community co-authors, which we share here using the first person plural (‘we’). We also describe a new university-community partnership called the GNP Research Collective, in which many of us are engaged. We outline these efforts in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Timeline of community-engaged research methods

In late 2017, I visited the GNP for the first time to attend a workshop, led by MUN, where local leaders expressed frustration about the recent report highlighting the region’s demographic challenges (Simms & Ward 2017). They were eager to show that the region had many assets that could be used to fight these trends. During subsequent visits, I met informally with community leaders to explore how asset mapping could challenge this decline narrative and highlight new development opportunities.

In Fall 2019, I lived in Port au Choix and conducted semi-structured interviews across the region. These interviews served as both data collection tools and storytelling sessions, inviting residents from diverse backgrounds to share their life stories and knowledge. The interviews followed an informal and narrative structure, asking what people felt their community’s greatest strengths were and what stories often were told about the region (Appendix 1). I also asked questions about a previous asset mapping project conducted on the GNP (Parill et al. 2014), for which local stakeholders expressed a desire to expand into a regional asset inventory. To engage the most inclusive group possible, I followed a purposive sampling rationale, selecting community members representing local government, non-profit organisations, businesses, and provincial and federal government, but also seeking residents who did not occupy formal leadership roles. Participants came from a variety of stakeholder groups (Table 1); to our knowledge, one participant self-identified as Indigenous and the rest were Caucasian.

We concurrently conducted four focus groups across the region to member-check preliminary findings with residents, engage with a diverse set of stakeholders in a group setting, and share an initial draft of the regional asset inventory to gather additional feedback (see Appendix 2 for guiding questions). Participants came from a wide range of stakeholder groups (Table 1); one participant self-identified as an Indigenous leader and all others (to our knowledge) were Caucasian.

Several members of the author team have become involved in a new initiative called the GNP Community Place (GNPCP), which seeks to establish a clinic in Port au Choix to improve access to primary care and offer various wellness programs not available in the area. This includes a bottom-up Research Collective that hopes to use community-based research to guide the design of the GNPCP. Our collaboration on this article is part of the larger Research Collective.

Three months after this primary research concluded, COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic and the province went into lockdown. Nevertheless, we continued to hold virtual discussions on how to use this research to support community development initiatives in the region and share it with a wider audience, particularly through the recently formed Research Collective. Once in-person gatherings were safe, we held community meetings in Port au Choix and St. Anthony in February 2021 to share our findings with a wider group of community members and facilitate a discussion on how they may inform the Community Place and other local initiatives. We also shared various drafts of the manuscript with community members across the GNP and discussed it on a community radio station (Voice of Bonne Bay Radio: https://vobb.org/) to share the findings with a wider group of residents.

A Deep Story of Sustainability on the Great Northern Peninsula

I remember Priscilla Renouf said to me one time…“over the 5,000 years of history we’ve had…the commonality between all of the cultures that was in and out of Port au Choix over the years is that we all came here chasing resources, and that was the fishery”…That’s what the Maritime Archaic was doing here, that’s what the Groswater was doing here, that’s what the Dorset was doing here…and then the European came, and that’s where we came from…but it’s all connected to the fishery.

Carolyn Lavers, resident of Port au Choix

Many cultures have moved across the GNP over the millennia. The region has been inhabited by Indigenous Peoples, including the Maritime Archaic, Dorset, Groswater and Beothuk, and continues to be home to the Mi’kmaq. L’Anse aux Meadows hosts the only known Viking settlement in North America (Parks Canada 2021a). These historical peoples have attracted academics like archaeologist Priscilla Renouf and historian Selma Barkham, whose research informed numerous heritage interpretation sites. More recent European settlement by the French and Basque peoples centred around the seasonal cod fishery, and they were followed by English and Irish settlers. The region was visited later by Dr Wilfred Grenfell, a British doctor who came to St. Anthony in the 1890s and built hospitals, orphanages and social housing, and was responsible for agricultural initiatives (Wood & Lam 2019).

In contrast to these heroic journeys of the past, recent stories about the GNP often feature crisis and decline. Before the cod moratorium that shook the entire province to its foundations, the fishery was transformed by the rapid introduction of large-scale vessels and industrial processing. Carolyn Lavers describes the fisheries boom in Port au Choix:

I was here in the last five years of the 70s and the early part of the 80s…there was 12 months of the year there was fishing going on…because the boats had become much larger. The 65-footers had been introduced with all this modern technology on them, so they could move up and down the whole coast…in the winter they moved to Port aux Basques and fished – and of course that was part of the problem because we fished the spawning season…

Personal communication, 6 November 2019

Just as pronounced as its boom, the bust following the moratorium was catastrophic for Port au Choix. Another resident described that:

When the moratorium happened, you saw people leaving…I recall so vividly watching the news and seeing…people in their 40s and 50s who lost their jobs at the fish plant…picking up their belongings and heading west.

Personal communication, 25 November 2019

Although residents told stories of decline, they also expressed optimism about the potential to revitalise local economies. One common source of hope was vacant public buildings, such as schools, which represented both a sense of loss and untapped opportunities to foster local economic development. Richard May mused that:

…if for argument’s sake…I won $10 million…to be able to sit down…and say, ‘Ok, I got this idea. Where might the best spot for that be?’ Ok, out in Port Au Choix would be a great place to put that. They’ve got a school that’s not being used. There’s not so many people working at the fish plant as there was. The population in the region has been relatively stable, so there must be unemployed people looking for work.

Personal communication, 7 March 2019

We now look across these community stories to identify three overarching themes about regional sustainability that directly address the narrative of decline. In each theme, we describe a key tension, reflecting both a problem-based message of vulnerability and a message of hope.

Honouring the past while looking to the future

The first tension is a sense of nostalgia for the pre-moratorium days, contrasted with an understanding that the region cannot return to these times. Many Port au Choix residents reminisced about a time when wharves were full of fishing boats, streets were busy with traffic and the community’s nightlife venues were bustling. According to a former Port au Choix resident:

…we had everything. We had a movie theatre. We had three or four clothing stores…you know, there was…how many gas stations? There was three take-outs and a restaurant, and there was two clubs, and there was a live band at each club every weekend.

Personal communication, 21 March 2019

Figure 3. Boat-blessing ceremony in Port au Choix, 1980 (Retrieved from Canadian Broadcasting Corporation NL, ‘Land and Sea’ series, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TGay54WsCDk)

Nonetheless, residents also acknowledged that the past had problematic elements. For example, the role of women in sustaining communities was discussed as both an important element of traditional livelihoods and a part of the region’s history that is often undervalued by both local leaders and external actors. One resident of Roddickton described the workforce of the pre-moratorium days as ‘100% employment…the men fished and the women worked in the fish plant, for the most part’ (Personal communication, 14 November 2019). A resident of Conche described this gendered division of labour before industrial fish processing was introduced: ‘women made the fish, they used to call it “making the fish”, you know…and [looked after] the boats, and the grass, and everything, and the children…’ (Personal communication, 4 December 2019).

Joan Simmonds shared this memory:

I remember one time, my mother…we had sheep, so she used to collect the wool and send it into…St. John’s to get spun into wool, right, for knitting… after she washed all the wool…she would have to wait for a nice day with no wind to lay out all the wool…and she had just put all the wool out in the meadow, and the wind came out. And…there was 10 of us running around, getting the wool, collecting the wool. And she was almost in tears because she knew that if she lost her wool, she wouldn’t get nothing knitted for the winter…”.

Personal communication, 4 December 2019

Another undervalued aspect of the region’s past and current identity is Indigenous stories. Due to systemic racism, Indigenous Peoples in Newfoundland have often concealed their identity to avoid discrimination. Today, the histories of ancient Indigenous groups, such as the Maritime Archaic, often receive less attention than colonial heritage, as revealed by a local tourism representative: ‘within the community, there seems to be more interest in our French heritage than in the Indigenous heritage’ (Personal communication, 25 November 2019). Furthermore, self-identifying Indigenous people were largely excluded from receiving official status in the Qalipu First Nation, with the Northern Peninsula Mekap’sk Mi’kmaq Band making recent efforts to increase the recognition of Indigenous people in the region (The Telegram 2018). Many residents have called for greater awareness of the role of Indigenous Peoples in both the region’s past and the identities of present-day community members. According to a local Indigenous leader: ‘along our coast … I think there is a very big lack of knowledge … of the Indigenous history, or Indigenous culture’ (Personal communication, 2 December 2019).

When reflecting on the more positive aspects of the region’s past, residents often had a pragmatic sense of it being impossible to return to this heyday. A forestry stakeholder reflected that:

…there was at least twenty to twenty-five trucks a day moving…And besides the logs that were going to the sawmills…Now, we can never go back to that …because at the time…people were harvesting manually, right, so…most of them were people with chainsaws in the woods.

Personal communication, 8 November 2019

Whether due to mechanisation in forestry, which shifted from chainsaws to large harvesting equipment, or ecological collapse, such as the moratorium, residents often expressed a sober outlook, that the region could not return to this Golden Age. A fisheries stakeholder reflected on fish processing plants: ‘…all those plants that died over the years, they’re not coming back, unless they got something to come back to’ (Personal communication, 18 November 2019), acknowledgeing that cuts to fisheries quotas had reduced the number of processing plants that could be economically sustained. These stories suggest that residents have a deep sense of nostalgia, but also acknowledge the need to recognise undervalued elements, such as the role of women in sustaining communities and the region’s Indigenous cultures in striving for a more equitable future.

Reducing dependence on external heroes

The second key tension is a sense that some outside entity will save the region from its problems, contrasted with a rejection of external dependence and desire for self-determination. The region’s history is marked by the heroic journeys of outsiders coming to the region. For example, the GNP’s main highway is called the Viking Trail, commemorating the Norse landing site at L’Anse aux Meadows.

Figure 4. Leif Eriksen statue at L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site

Perhaps the most celebrated external hero is Dr Grenfell, whose journey to the GNP to alleviate poor health conditions is a source of pride for St. Anthony and other communities (Wood & Lam 2019). According to a St. Anthony resident:

even in…Englee, Conche…Roddickton, I mean, Dr. Grenfell’s legacy…even through Flower’s Cove, Daniel’s Harbour, that area, right. Got a connection pretty much all over.

Personal communication, 17 November 2019

More recent external saviours include large-scale infrastructure and industrial projects. Several projects were being discussed at the time of the research, including a wood pellet plant in Hawke’s Bay spearheaded by British firm Active Energy Group (AEG), a proposed tunnel between the peninsula and Labrador (which is currently connected by ferry) and a port development at Crémaillére Harbour to service the oil industry. However, residents also felt that these projects perpetuated external control over local resources. One forestry stakeholder described how:

…we’re in a precarious situation…because two thirds of our timber rights now have been given to AEG, their office in England. So, all we can do is look at it grow. We got no control over it.

Personal communication, 14 November 2019

Community members told stories of saviours fallen from grace: development projects that sparked hope among local stakeholders but ultimately failed. For example, Holson Forest Products received government funding to operate a sawmill and pellet plant in Roddickton-Bide Arm, but was shuttered in 2014. A local forestry stakeholder reflected:

…we thought we had something moving when they give the money to Holson Forest Products…we thought that would be the bright spot, or the saviour of the forest industry, but that didn’t work out.

Personal communication, 7 November 2019

These failed projects damaged not only regional economic conditions, but also the psychological wellbeing of residents. Community members’ stories suggest a ‘boy who cried wolf’ dynamic, in which local stakeholders believe that the right project will come some day, but perhaps will not receive adequate support because of these past failures. This dynamic reflects an overall sense of external dependency on regional development. One recent newcomer to the region said:

…there is a lot of Newfoundlanders who live up here who have lost an internal locus of control. Everything is because of an external source, and they feel so little ability to affect their situation.

Personal communication, 13 November 2019

In contrast to this external dependence, many residents identified the need for individuals to foster greater self-reliance by taking on leadership roles in local organisations, such as Town Councils, small businesses and non-profit organisations. The founder of the recently formed Norpen Status of Women Council described the challenges faced by those seeking to launch new initiatives:

…trying with this Status of Women Council…I could have give up a dozen times along the way, and said ‘oh this is too much work’…And you run into little obstacles that…you want to throw your hands up and say ‘I’m giving this up!’, or whatever. But I think…you have to be persistent, persistent, and be positive…

Personal communication, 2 December 2019

Rediscovering local conceptions of wellbeing

The final tension is that residents learn from a young age that they should leave the region to be successful, contrasted with an identified need for youth to rediscover local ideas of wellbeing. In other rural regions, brain drain has been linked to a tendency for educational systems to teach that rural lifestyles are not valuable (Corbett 2007). On the GNP, Carolyn Lavers described that:

One of the things that we never did – and that goes back even from when I was in school – we never, never, never told our children the benefits of living in rural regions. Oh, and I’m still hearing it – you get your education and you leave, ’cause there’s nothing here for you.

Personal communication, 6 November 2019

Residents described a generational divide that occurred after the moratorium, in which younger generations became geographically severed from their communities and lost touch with traditional ways of life and values. A Port au Choix resident shared that:

‘…we’ve lost the connection. So we’ve got the aging people, aging parents who by now are dead, a lot of them…So the middle-aged people, some of them will come back and retire, but the younger people’s not coming back… My boys, they moved away to get work out of school, basically, because, you know, there wasn’t no longer work available here…

Personal communication, 25 November 2019

To restore this connection, residents discussed traditional practices, such as food self-provisioning, as a way for younger generations to rediscover local ideas of wellbeing. Self-provisioning activities are important sources of food across NL: 44.2 per cent of NL residents engage in some amount of fishing to supplement their diet (21.9 per cent above the national average) and 39.3 per cent in foraging (22.9 per cent above the national average (Atkinson et al. 2020). On the GNP, self-provisioning may be even more prevalent, with one resident estimating that

‘…just on very broad strokes, I’d say 20% of people’s income is on average from berries or getting your moose, or you know, dragging scallop, or getting fish’.

Personal communication, 13 November 2019

A recent study on the region’s roadside gardens, a tradition originating from the Grenfell Mission, identified high rates of household agricultural production (Wood & Lam 2019). A resident of Englee reflected:

…we grew our own vegetables, we sustained ourselves…there was no grocery, there was no refrigerator, there was no power. So we had to sustain ourselves on the wild, and do our own gardening, and keep it all winter in our cellars…

Personal communication, 4 December 2019

Figure 5. Roadside garden near St. Anthony Bight

In reflecting on traditional practices, such as self-provisioning, residents highlighted the need to celebrate local livelihoods and identities rather than striving for external notions of wellbeing. This challenges prevailing wellbeing indicators, which tend to privilege narrow quantitative measures like per capita income over intangible factors (Ramos 2019). More broadly, residents identified the need to teach youth that they do not need to leave to be successful, but rather instil an appreciation for the region’s rural culture and lifestyle.

Stories of Community Renewal

I was filled with hope today when a community member said to me “It is time to tell a new story about the health and wellness of Newfoundlanders. It is not all doom and gloom; some of us are healthy and living well in our rural communities”. When we start changing the narrative ourselves, telling our own ‘new rural story’, that is how we can really take charge and start shaping our own future.

Joan Cranston, resident of Norris Point

The perspectives shared above demonstrate that the deficiencies-based narrative often told by powerful actors does not tell the whole story of the GNP. They also challenge academic research not only to critique dominant stories, but to work hand-in-hand with community members in telling a new story based in potential and possibility. In that spirit, we now share stories of community renewal initiatives that are imagining alternative futures for the GNP, told by the local change-makers who are leading them. Based in four communities across the region, these initiatives have taken different approaches to mobilising community assets and are at different stages of development, but have each engaged with the deep stories of their communities to enhance self-determination and community well-being.

French Shore Interpretation Centre

By Joan Simmonds

In 2000, some Conche residents founded the French Shore Historical Society (FSHS) as a formal organisation to present the region’s history and culture, and has since created an interpretation centre for local people and an attraction for tourists (website: https://www.frenchshore.com/en/attractionsanintriguinghistory.htm). Building on the preservation of historical sites, the town and FSHS share the goals of preserving their cultural history, promoting its continued strength, using it as an economic development tool, and providing a sense of shared community among residents.

To begin their heritage development, the town provided a building for the museum and both groups worked to raise funds for renovation and exhibit development. Work on this project was provided by local craftsmen, volunteers, town staff, regional government agents and external non-profit organisations. FSHS collaborated with the town on expanding and maintaining a growing heritage infrastructure, with different funding agencies to help support the programs. There are a number of groups and committees in the French Shore region, including representatives from the town and FSHS, that develop and work on heritage development projects. Tourism businesses also play a role in this. As in many rural places, residents wear ‘several hats’ and collaboration is key to sustaining the economy and lifestyle. FSHS has also reached out to cultural groups in France that share their history. The outreach has resulted in joint publications, conferences, and exchanges between museum staff.

After ten years of participating in many partnerships with funding agencies, universities, and arts and craft councils, FSHS decided to use our history to create a piece of artwork that would tell the story of the French Shore. The French Shore Tapestry would be utilised to enhance the economic benefits of tourism for the community and would give the local population an increased awareness of their own history. The tapestry has become an anchor attraction for this region.

Since the opening of the French Shore Interpretation Centre, we have seen an increase in the number of visitors to our town and an increase in the cultural activities within the town. The town has two Airbnb accommodations and last year, in the midst of the pandemic, a new wellness-based tourism experience was launched within the town, called Moratorium Children, started by a young woman who recently returned home to Conche after living away. The French Shore Interpretation Centre is playing an active role in helping people research the history of the French Shore of Newfoundland. This research will not only increase community members’ awareness of our history, but also share the story of Conche with the wider world, resulting in a positive impact on our town.

The Old Cottage Hospital

By Joan Cranston

The former Bonne Bay Cottage Hospital was built in 1939 in Norris Point as part of the Cottage Hospital System put in place by the Commission of Government to provide healthcare in rural communities. It was built using locally donated labour and material. The government paid for the nails and the wages of the foreman. The hospital provided high-quality care to the communities from Daniel’s Harbour in the north to Trout River in the south for over 60 years, until it closed its doors in 2001 when a new modern hospital was built.

A group of community volunteers recognised the value of preserving this unique piece of community heritage infrastructure and formed a not-for-profit community corporation to take ownership of the building. The Old Cottage Hospital now functions as a Social Innovation/Rural Research/Community Response Centre, offering a safe, accessible place that serves the needs of the surrounding communities, and also a different model of sustainable economic and social development (website: https://oldcottagehospital.com/about/).

We work in partnership with many community, government and academic agencies and institutions to provide programs and services that help to preserve local culture and heritage, promote community health and wellness, and foster community economic and social development. The Old Cottage Hospital is home to numerous initiatives and programs, such as a community kitchen that serves healthy plant-based meals, a library, a community radio station, a local concert series, and hopefully a daycare centre that is currently being developed to meet the growing need for childcare for young families in the area. In the words of one community member, the centre ‘was built by, and belongs to, the community. It reflects our past; it supports the present; it will enrich our future.’

GNP Community Place

By Joan Cranston

The GNP Community Place (GNPCP) offers a social enterprise solution to a ‘wicked’ healthcare problem for communities on the rugged coast of the GNP. Lack of access to health services, such as physiotherapy, massage therapy, mental health, addictions counselling and other health and wellness services in rural areas, as well as lack of treatment for chronic pain, arthritis, injuries and other physical and mental health conditions leads to poor health outcomes and preventable disability. One of the factors contributing to this problem is the absence of appropriate clinical space for these services.

A group of citizens in Port au Choix met with a community broker to create a solution. They formed a not-for-profit community corporation and adopted a social enterprise approach to the problem. They are raising the funds to purchase a community heritage property and to redevelop it as a ‘Community Place’. It will be designed to provide the following:

• private treatment rooms and offices available for rent by visiting professionals, such as physiotherapists, massage therapists, counsellors, other health practitioners, and researchers

• a fitness centre for individualised exercise programs

• a community kitchen to increase access to healthy food through education, cooking classes and food security initiatives

• community café/meeting room, which will provide a flexible space for meetings and workshops, and serve as a ‘place’ for the community to gather to engage in health and wellness activities

• accommodation for visiting professionals and researchers.

Revenue from the rental of space to visiting professionals and other services located in the ‘place’ will help to offset the costs of heating and lighting, insurance, etc. This will be a partnership between the community (people), private practitioners and the public health system. The project will involve other partners as well, such as research partners, funding partners and corporate partners.

This project is unique in that it offers a social enterprise solution to an identified issue, in which we are blending non-profit funding strategies, such as grants with market-based tools, but prioritising community reinvestment over profit. It utilises an interdisciplinary Collective Impact Approach and a ‘3-P’ Partnership Model (Public/ Private/ People/Community), while introducing the concept of community brokers. It will be evidence-based and supported by the involvement of the GNP Research Collective.

Food sovereignty initiative

By Renee Pilgrim

Since development of the roads up the GNP, these are now peppered with roadside gardens constructed from the remaining piles of topsoil. Residents of the GNP are resourceful people and the available soil also meant more food for families and communities from the gardens.

Before that, people had little gardens around their houses, up over a hill or anywhere they could find fertile and workable soil. With a short growing season and limited resources, growing food was an incredible effort endured to sustain families over the winter. Dr Grenfell recognised the nutritional health challenges and developed the Grenfell Gardens for the hospital, and supported communities with seeds and start-up materials (Wood & Lam 2019).

Gardens weren’t a hobby or supplemental; they meant survival. With the arrival of roads and access to fertile soil gardens, the locals could feel abundant. Roads also opened up travel for work, and families left. More food was imported and the need for gardens declined, as did the population.

Gardening was challenging, but food could be bought and many had money. Growing food had become a choice for some, for others still necessary to feed a large family or supplement a seasonal income. The perspective had shifted and some folk took pride in not having to grow a garden. A sign of progress. Over these same years, diabetes, heart disease and obesity grew province-wide and notably in this area. No longer suffering from starvation, scurvy or rickets, the population developed new nutritional health challenges, being overfed and undernourished.

The beat of rural life turned towards the mainland. As people left for bigger city centres, we imported packaged food: carrots from Israel, apples from Mexico and potatoes from Ohio, anything frozen or in a box or can. Generations separated from the land and sea, losing interest in what had long kept us here.

Fresh and local produce is scarce on the GNP, except in the Fall when gardeners have enough turnips, cabbages, carrots, potatoes and beet. Some have enough to last the winter where there is storage, but cold storage has proved to be another barrier for local farmers. The growing season is another challenge – it isn’t long enough for too many other varieties of vegetables and the population is more likely to eat packaged, frozen and foreign foods.

A study of the history of Grenfell Gardens and other factors (Wood & Lam 2019) raised the question: would a greenhouse be a valuable resource to supplement the short season? In February 2021, the GNP Research Collective hosted a community meeting, where it was determined that a community assessment was needed, to be headed by Brenda Whyatt. Additionally, interested members formed the St. Anthony & Area Gardening Alliance (SAAGA), headed by myself, Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioner and Acupuncturist Renee Pilgrim, to address the skill loss of younger generations, share resources and create a community network around growing local nutritious food.

The town of St. Anthony provided the Friendship Park greenhouse. To date, we have held four public events: a seed exchange, plant exchange, compost talk by 3F Waste Recovery and a harvest.

More people have planted crops this year than previously, maybe a side-effect of COVID-19. The retired roadside gardens are coming back in droves and, along with the potholes, will make for a slow Sunday drive as people tend to gardens this season and in many more to come. People are still growing the same things; however, resource sharing, diversified crops, adequate soil and cold storage are some of the bigger items we’re identifying, and hope to address in time.

Concluding Thoughts

Through both the deep story emerging from local voices and stories that community change-makers have told of their renewal efforts, this article contributes to scholarly understanding of sustainability in rural and resource-based regions and efforts to achieve it in practice. We conclude by identifying the article’s main practical and academic contributions, reflecting on both the joys and the challenges of the research process we have followed, and highlighting potential paths forward for applying its lessons to the GNP and beyond.

Telling a new story about rural sustainability

We contribute to scholarly understanding of the potential of storytelling for facilitating empowerment in rural and resource-based communities. Building on the long-standing use of narrative approaches in Indigenous research (Christensen, Cox & Szabo-Jones 2018), we show how storytelling also can be used to centre the knowledge and experience of non-Indigenous communities on the periphery of uneven development processes (Kühn 2015). Rural regions have often been abandoned by capitalist systems once primary resources are exhausted (Winkler et al. 2016), while largely being overlooked in the theory and practice of societal transitions to sustainability (Lowery et al. 2020). Ironically, the deep story concept – which explains how communities left behind in these processes can fall prey to xenophobic political movements (Hochschild 2016) – can also help identify inclusive visions of community sustainability emerging from residents’ deep-seated experiences and memories. Thus, we extend research on the role of storytelling in sustainability transitions (Veland et al. 2018), while reinforcing the importance of narratives in cultural planning and asset mapping (Ashton et al. 2015).

On the GNP, stories of boom and bust in primary industries and dependence on external heroes reveal an entrenched myth that will take considerable effort to uproot – particularly due to the external locus of control described by residents and collective traumas from failed development projects. Our findings hint at potentially valuable links between psychological well-being and community self-determination, which future research could explore by examining the relationship between individual trauma and collective efforts to make sense of these experiences (Maitlis 2020). Yet, our community renewal stories also show how residents are challenging these myths through self-directed initiatives such as community clinics, local agriculture movements and heritage sites. In particular, the French Shore Tapestry represents a form of visual storytelling, weaving the region’s history into a story narrated by local voices.

Stories as tools for identifying undervalued assets

We also offer new insight into how communities can use storytelling to show the value of often undervalued assets. Communities that are characterised as deficient by powerful actors often turn to asset-based development approaches (Bebbington 1999), demonstrating the value of intangible assets that often are overlooked in prevailing sustainability indicators (Ramos 2019), and highlighting the diverse ways communities sustain themselves beyond mainstream economic development models (Arias Schreiber, Wingren & Linke 2020).

Local actors on the GNP are using a multitude of local assets to renew communities. However, these assets often are overlooked in dominant narratives that favour quantitative indicators like demographic decline (Simms & Ward 2017). These narrow measures do not tell the whole story about rural sustainability, including the interdependence of diverse forms of community capital ranging from labour markets to cultural identity (Emery & Flora 2006), while ignoring the entrenched values and beliefs that inform residents’ decisions to leave or stay in their communities. By exploring generational divides that occurred after the moratorium and lessons that children learn about their communities, we build on previous research about rural brain drain (Corbett 2007), while offering new insight into how rural communities can restore intergenerational connections through traditional practices, such as self-provisioning. By highlighting these local practices, we reaffirm the power of asset-based approaches (Kretzmann & McKnight 1993) and challenge damage-centred narratives that tend to privilege external interventions over endogenous solutions (Tuck 2009). The stories told by community change-makers, for example, the SAAGA initiative, which is reconnecting communities to their agricultural history, demonstrate how grassroots efforts can harness valuable knowledge and skills that often have been lost, while forging new bonds between older and younger generations.

Storytelling to reimagine academic-community relationships

Finally, we demonstrate that storytelling, as research process, can facilitate participatory methods and reduce power imbalances between academics and community members. Considering how academic research often perpetuates extractive colonial practices (Walker et al. 2020), new approaches to community-based inquiry that centre community members’ voices and share power in both conducting and writing about research are needed. By using storytelling methods in both collecting primary data and writing the research findings, we seek to place power in community members’ hands through a co-creative process. In particular, the community renewal stories demonstrate that local residents can claim power by sharing their experiences, aspirations and successes in their own words.

There are many ways that we could have embodied participatory processes more fully, such as engaging with a more diverse set of residents or approaching the writing process in a more participatory manner. As the academic author, I recognise my incentive to publish and acknowledge the burden I have asked of the community co-authors. We also could have engaged more proactively with the region’s Indigenous identities by exploring decolonising approaches to telling these long-suppressed stories – an opportunity that we hope to explore further in partnership with local Indigenous leaders. While far from fully participatory, our approach aimed to demonstrate the potential of storytelling as both a theoretical lens for understanding rural sustainability and a practical way to do research that strives for more equitable power relations.

Yet, this story is only the beginning. On the GNP, we will continue using community-based research to demonstrate the potential of local initiatives, such as the Community Place and SAAGA, engaging with residents to explore their own research questions and striving for more participatory methods. We will also continue engaging with a global network of community-based researchers to learn from university-community collaborations in other places and explore how our storytelling approach might be adapted in similar contexts. We conclude with a challenge: to reimagine the role of research in creating sustainable communities, critically reflect on the power of the stories we tell, and uplift new stories of empowerment and possibility.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to the many community members on the GNP who shared their knowledge, perspectives, and time to make this research possible. We thank the Department of Industry, Energy, and Technology of the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, the Town of Flower’s Cove, the Town of Roddickton-Bide Arm, and the College of the North Atlantic for support in conducting focus groups. We also acknowledge the support of Drs. Kelly Vodden, John Dagevos, Ratana Chuenpagdee, Doug May, Mery Perez, and Natalie Slawinski, the Grenfell Office of Research and Engagement, and Myron King (Environmental Policy Institute, Grenfell Campus) for his assistance in creating maps. We also thank the Gateways editorial team, the special issue guest editors and co-contributors, and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

References

Antle, R 2021, ‘N.L. budget pledges “change” and shift in status quo to rescue fiscal future’, CBC Newfoundland and Labrador, 31 May, viewed 7 June 2021, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/nl-budget-2021-main-1.6046843.

Arias Schreiber, M, Wingren, I & Linke, S 2020, ‘Swimming upstream: Community economies for a different coastal rural development in Sweden’, Sustainability Science, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00770-0

Ashton, P, Gibson, C & Gibson, R 2015, By-roads and hidden treasures: Mapping cultural assets in regional Australia, UWA Publishing, Perth, Australia.

Atkinson, J, Liboiron, M, Healey, N, Duman, N & Van Harmelen, M 2020, Overview of the importance of wild food in NL, Food First NL, St. John’s, NL, viewed 12 September 2020, https://www.foodfirstnl.ca/wild-food.

Bebbington, A 1999, ‘Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty’, World Development, vol. 27, no. 12, pp. 2021–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00104-7

Bottici, C & Challand, B 2006, ‘Rethinking political myth: The clash of civilizations as a self-fulfilling prophecy’, European Journal of Social Theory, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 315–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431006065715

Bridger, J & Luloff, A 1999, ‘Toward an interactional approach to sustainable community development’, Journal of Rural Studies, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 377–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(98)00076-X

Christensen, J, Cox, C & Szabo-Jones, L 2018, ‘Introduction’, Activating the heart: Storytelling, knowledge sharing, and relationship, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, Waterloo, ON.

Community Accounts 2020, St. Anthony-Port Aux Choix Rural Secretariat Region Profiles, viewed 28 October 2018, https://nl.communityaccounts.ca/profiles.asp?_=vb7En4WVgbWy0nI_.

Corbett, M 2007, Learning to leave: The irony of schooling in a coastal community, Fernwood Publishing, Black Point, NS.

Davis, R 2014, ‘A cod forsaken place? Fishing in an altered state in Newfoundland’, Anthropological Quarterly, vol. 87, no. 3, pp. 695–758. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2014.0048

Emery, M & Flora, C 2006, ‘Spiraling-up: Mapping community transformation with Community Capitals Framework’, Community Development, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330609490152

Gibson, R 2014, ‘Collaborative governance in rural regions: An examination of Ireland and Newfoundland and Labrador’, PhD Thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Hall, H & Donald, B 2009, Innovation and creativity on the periphery: Challenges and opportunities in Northern Ontario, Working Paper Series: Ontario in the Creative Age. REF. 2009-WPONT-002.

Hochschild, A 2016, Strangers in their own land: Anger and mourning on the American Right, The New Press, New York.

Kretzmann, J & McKnight, J 1993, Building communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community’s assets, Center for Urban Affairs and Policy Research.

Kühn, M 2015, ‘Peripheralization: Theoretical concepts explaining socio-spatial inequalities’, European Planning Studies, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 367–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.862518

Lowery, B, Dagevos, J, Chuenpagdee, R & Vodden, K 2020, ‘Storytelling for sustainable development in rural communities: An alternative approach’, Sustainable Development. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2124

Maitlis, S 2020, ‘Posttraumatic Growth at Work’, Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 395–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044932

Markey, S, Connelly, S & Roseland, M 2010, ‘Back of the envelope’: Pragmatic planning for sustainable rural community development’, Planning Practice and Research, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697451003625356

Parill, E White, K, Vodden, K, Walsh, J & Wood, G 2014, Regional asset mapping initiative: Humber-Northern Peninsula, Southern Labrador Region, Grenfell Campus, Memorial University, Corner Brook, NL.

Parks Canada 2021a, L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site, viewed https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/nl/meadows/info.

Parks Canada 2021b, Port au Choix National Historic Site, viewed 25 March 2020, https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/nl/portauchoix/info.

Ramos, T 2019, ‘Sustainability assessment: Exploring the frontiers and paradigms of Indicator Approaches’, Sustainability, vol. 11, pp. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030824

Ritchie, D 2014, Doing oral history, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Roberts, T 2016, ‘With few prospects, Northern Peninsula youth say they’ll join the exodus’, CBC News, November.

Russell, C 2016, ‘Sustainable community development: From what’s wrong to what’s strong’, YouTube Tedx Talks.

Sandercock, L.2005, ‘Out of the closet: The importance of stories and storytelling in planning practice’, in B Stiftel & V Watson (eds), Dialogues in urban and regional pllanning, Routledge, New York, pp. 299–321. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203314623_chapter_12

Simms, A & Ward, J 2017, Regional population projections for Labrador and the Northern Peninsula, Report prepared for the Leslie Harris Centre for Regional Policy and Development, Memorial University Population Project, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL.

The Telegram 2018, ‘Northern Peninsula’s Mekap’sk Mi’kmaq Band formally asserts Aboriginal title for region’, 6 March, viewed 12 September 2020. https://www.thetelegram.com/news/local/northern-peninsulas-mekapsk-mikmaq-band-formally-asserts-aboriginal-title-for-region-191169/.

Tuck, E 2009, ‘Suspending damage: A letter to communities’, Harvard Educational Review, vol. 79, no. 3, pp. 409–28. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15

United Nations 2015, ‘Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’, General Assembley 70 session, vol. 16301, October, pp. 1–35.

Veland, S, Scoville-Simonds, M, Gram-Hanssen, I, Schorre, A, El Khoury, A, Nordbø, M, Lynch, A, Hochachka, G & Bjørkan, M 2018, ‘Narrative matters for sustainability: the transformative role of storytelling in realizing 1.5°C futures’, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 31, pp. 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.12.005

Walker, S, Bruyere, B, Grady, M, McHenry, A, Frickman, C, Davis, W & Unity Women’s Village 2020, ‘Taking stories: The ethics of cross-cultural community conservation research in Samburu, Kenya’, Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, vol. 13, no. 1, viewed 14 February 2021, https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/ijcre/article/view/7090. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v13i1.7090

Winkler, R, Oikarinen, L, Simpson, H, Michaelson, M & Gonzalez, M 2016, ‘Boom, Bust and Beyond: Arts and Sustainability in Calumet, Michigan’, Sustainability, vol. 8, no. 3, p. 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030284

Wood, G & Lam, J 2019, Restoring and retelling the story of Grenfell Gardens, Sustainable Northern Coastal Communities Applied Research Fund Report, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Corner Brook, NL

Young, G 2008, Reshaping planning with culture, 1st edn, Routledge, London.

Appendix 1: Guiding Questions for Semi-structured Interviews

Participant’s background in the region

• Can you tell me about your previous professional background and any involvement you may have had with other types of community development or sustainability projects in the past?

• What geographical scale has your community development work focused on (e.g. your community, the entire Great Northern Peninsula region, a smaller region, other)?

• What does sustainability mean to you, for your community and for the Great Northern Peninsula region overall?

Story of community strength

• Can you tell me a story about your community or about the broader region that symbolises to you what makes it a great place to live? In this story, you may choose to discuss any of the following:

◦ Your personal story, including your role in the community in which you live, either professionally or as a volunteer, and how you came to take on that role

◦ A story that highlights what is strong about your community, including anything that you are proud of or feel makes your community a good place to live

◦ Stories that show how the community has sustained itself over time and continues to do so

◦ Stories about the cultural heritage of the community or region, or other heritage assets

◦ Stories about the broader region (whether a sub-region or the region as a whole).

Familiarity with previous asset mapping project

• Are you familiar with the asset mapping project that was carried out in the region in 2014?

• Were you involved in that project? If so, what was the nature of your involvement?

• Did the project have any strengths or weaknesses that you think would be important to consider if building on it in the future?

Perspectives on a regional asset mapping initiative

• How could future efforts to identify and mobilise regional assets learn from the successes and failures of the previous project?

• How could regional asset mapping be used to tell the story of the Great Northern Peninsula and its communities, such as the stories of community strength you have shared?

• What challenges might arise in creating a regional asset mapping tool?

• What could be done to make such a process beneficial for regional economic development?

• How could it be incorporated into regional governance efforts?

• In what ways could these regional assets be visualised or otherwise shared so that people in the region could learn about them and use them in decision-making?

• Do you know of any similar initiatives that have occurred in the region or elsewhere that may be worthwhile considering?

• What other thoughts or recommendations would you offer to inform this kind of effort in the future?

Appendix 2: Guiding Questions for Focus Groups

Review of regional asset inventory

• Based on our individual discussions during the interviews, do the additions to the regional asset inventory seem to accurately reflect the assets in your communities that we discussed?

• What other assets do you think should be added to the inventory, either for a particular community or for the region (or sub-region) overall?

• Are there any assets you think should be removed from the inventory? If so, why?

• How well does the asset inventory portray the assets of your home community, this sub-region, or the Great Northern Peninsula overall?

• What could be done to ensure that the inventory portrays community and regional assets more effectively?

Perspectives on use of regional asset inventory

• How can this inventory be used by individuals and groups in the region, or in specific communities?

• Which groups or organisations do you think would be most likely to use the inventory, and for what purposes?

• How could regional asset mapping be used to tell the story of the Great Northern Peninsula and its communities?

• What could be done to make this asset inventory beneficial for regional economic development?

• How could it be incorporated into regional governance efforts?

• What challenges might arise in using this tool, or other asset mapping tools, in community and regional development?

• In what ways could these regional assets be visualised or otherwise shared so that people in the region can learn about them and use them in decision-making?

• Do you know of any similar initiatives that have occurred in the region or elsewhere that may be worthwhile considering?

• What other thoughts or recommendations would you offer for making this inventory as useful as possible for the region?