Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement

Vol. 14, No. 1

May 2021

PRACTICE-BASED ARTICLE

Prioritizing Partnership: Critical Steps Towards Relationship Development for Sustaining Community-University Partnerships

Stephanie Baker1 and Ann Meletzke2

1 Assistant Professor of Public Health Studies, Elon University, Elon, North Carolina, USA

2 Executive Director, Healthy Alamance, Burlington, North Carolina, USA

Corresponding author: Stephanie Baker; sbaker18@elon.edu

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v14i1.7595

Article History: Received 17/02/2021; Revised 25/03/2021; Accepted 22/04/2021; Published 05/2021

Abstract

The increase in undergraduate programs in public health within liberal arts institutions in the United States creates an opportunity for community-engaged research with local public health organisations. This type of engagement is one way to connect community members, agency representatives, students, staff and faculty around social justice organising efforts that impact entire communities. Authentic relationships and partnerships can reduce real barriers to building bases of support for intervention development, local advocacy efforts and policy change, to achieve a more just and equitable society. This practice-based article describes key steps to partnership development between a private, engaged-teaching liberal arts institution and a local public health non-profit located in central North Carolina. The partnership was formed to use community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches to address health equity. To create an authentic CBPR partnership, an intentional partnership development process took place with key steps that were integral to the formation. Structured learning experiences and mentorship provided by previously established CBPR partnerships were critical to partnership development. Shared capacity building experiences, consistent meetings and goal setting facilitated progress. This partnership has lasted since 2015 and continues to grow. Partnership development is an important foundational activity for CBPR and is feasible for local community organisations and undergraduate public health studies departments outside of Schools of Public Health.

Keywords

Partnership Development; Community-Academic Partnership; Community-Based Participatory Research (Cbpr); Health Inequities; Community Research; Community Engagement

Introduction

Undergraduate public health programs in the United States have seen a recent increase in volume; in 1992 there were 45 institutions with undergraduate programs in public health and by 2012 the number had increased to 176 (Leider et al. 2015). Some departments reside in schools that also offer graduate-level public health degrees, often accompanied by greater resources and administrative support for research, while some undergraduate public health departments are in liberal arts institutions within, for example, a College of Arts and Sciences, where no graduate-level public health degrees are offered (Riegelman & Albertine 2011). Liberal arts institutions are committed to baccalaureate-level education, award most degrees within arts and sciences majors, and tend to have smaller class sizes and more intentional interaction among faculty and students. Over the past decade, there have been more publications investigating pedagogy owing to the increasing number of undergraduate programs in public health (Barnes et al. 2012; Caron 2013; Nelson-Hurwitz & Tagorda 2015; Yeatts 2014), but there is less in the literature about the opportunities and potential benefits undergraduate programs present to the communities within which these liberal arts institutions reside. Many liberal arts institutions support engaged-learning, and the presence of a public health studies department creates an opportunity to expand upon engaged-learning to include engaged-research, using a community-academic partnership approach that is practised among public health workers and researchers, for example, community-based participatory research (CBPR).

CBPR is an approach to research adapted by public health researchers and practitioners that sets high standards for equitable processes, power sharing and community leadership, and participation in all aspects of the research process (Israel et al. 2005). CBPR is an effective approach to address health inequities (Israel et al. 1998; Parker et al. 2012; Wallerstein & Duran 2006). A critically important stage in the CBPR approach is partnership development and capacity building (Allen et al. 2011; Coombe et al. 2018; Corbie-Smith et al. 2015; Israel et al. 2005; Parker et al. 2012). While new undergraduate public health departments have the opportunity to create CBPR partnerships, the first stage of the process of partnership development may be unique for programs that reside within liberal arts colleges without graduate degree programs because these programs often lack a history of partnership development and may also lack the expertise and resources that exist in programs with a greater emphasis on research. The communities within which these institutions exist may also be unfamiliar with CBPR, but the process of relationship development could equip these community and academic institutions with important tools, skills and resources to address health inequities.

Authentic engagement in mutually beneficial community-campus partnerships using CBPR has the potential to create more opportunities for social justice work at the local level for community, students, staff and faculty. The basic tenets of CBPR include intentional engagement of those most impacted as well as shifting power towards marginalized communities. A CBPR approach creates the environment for universities to find their role in supporting the leadership of community organisers and activists, who have lived experiential expertise. While this expertise may not fall directly in line with a specified project, it is important expertise and should be valued. The relationships that develop can lead to community members seeking resources and assistance from institutions in order to play their part in movements for equity and justice. Institutions must follow the lead of community members as top-down solutions to problems are rarely based on an accurate and in-depth understanding of the problem or viable, practical and realistic solutions.

This article aims to provide a picture of what partnership development can look like for regional communities and the liberal arts colleges within them. It does so by describing the partnership formation and key steps in shared capacity building of a community-academic partnership between a private, engaged-teaching intensive liberal arts institution in south-east United States and a local public health non-profit organisation located in a regional city and suburban county community that did not have previous exposure to CBPR. The article also shares lessons learned that can be applied more broadly to partnerships in a variety of developmental stages.

Partnership Formation

Elon University, the academic partner’s institution, has a community engagement centre, the Kernodle Center, which facilitates service learning and volunteer and community engagement opportunities, and also hosts a lunch once each semester to create space for faculty and the leadership of local community agencies and organisations to meet and network. A networking guide containing contact information for participating faculty and representatives from the community organisations is created and distributed. Attendees at the event are assigned to tables based on shared interests. During three rounds of networking, Kernodle Center staff help to connect potential partners in conversation. Event participants are provided with a gift card for a local coffee shop to encourage continuing interaction.

At one of these events, the faculty member, who worked in the Department of Public Health at Elon University, and the executive director of Healthy Alamance, the potential partner in the project, were assigned the same table due to their shared interest in public health. The Elon faculty member had belonged to a community-academic partnership in the city of her previous place of employment and was actively looking for a community partner who would be interested in working together to address health equity challenges in Alamance County (described below). The potential community partner had a history of engaging with Elon faculty through guest lectures and academic service-learning projects, and was interested in collaborating around research. Healthy Alamance was interested in a CBPR approach as they transitioned away from traditional public health interventions, such as addressing obesity through support of farmers’ markets and nutritional programs, to more community-engaged, participatory and structural-level change strategies. To achieve these changes, more creative ways of partnering with communities most impacted by inequities was critical.

These shared interests led to a follow-up meeting, a series of email exchanges, and ultimately a decision to apply to the Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center’s Community Based Participatory Research Partnership Academy for assistance in growing and strengthening a partnership (see below for more details). This all happened within a two-month period.

Community Characteristics

Alamance County is located in central North Carolina and 70 per cent of the residents live in rural areas (AccessNC Dashboard n.d.). Approximately 68 per cent of Alamance County residents are White, 20 per cent are Black and 13 per cent are Hispanic/Latinx (Piedmont Health Counts :: Demographics :: County :: Alamance n.d.). Among residents 25 years and older, 85 per cent are high school graduates and 23 per cent have a Bachelor’s degree or higher (U.S. Census Bureau Quick Facts, Alamance County, North Carolina, n.d.).

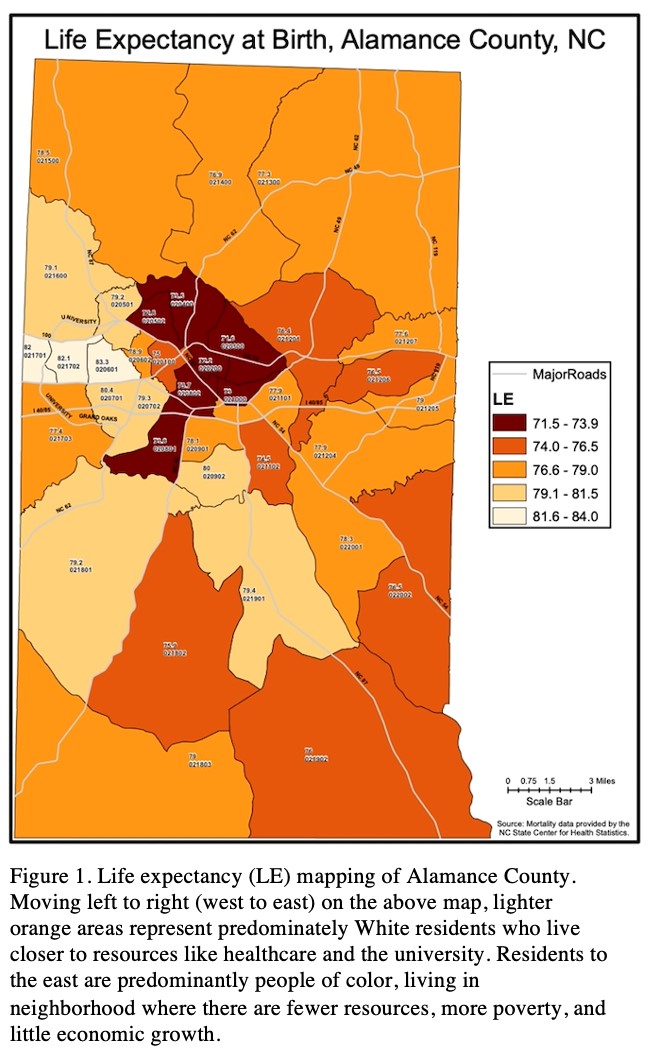

Poverty rates in Alamance County (16% of the total population) are worse than the poverty rate for the state of North Carolina (12.4%), and the poverty rate for children is 30% (Alamance County Community Health Assessment 2018). While a larger number of White residents in the County live in poverty, a disproportionate number of people of colour do so: 26%, 35% and 32% of Black, Hispanic/Latinx, and American Indian/Alaskan native people, respectively, live in poverty compared to 13% of White people (U.S. Census Bureau n.d.). Approximately 34% of Black children, 24% of Hispanic/Latinx children and 6% of White children reside in areas of concentrated poverty (Selected Indicators for Alamance County, North Carolina n.d.). Additionally, median household income is higher for White (US$54,410) compared to Black (US$37,797) and American Indian/Alaskan Native residents (US$31,486) (Piedmont Health Counts :: Demographics :: County :: Alamance n.d.). Black residents have a much higher rate of cancer, heart disease and stroke, and die at an earlier age compared to their White counterparts (Alamance County Community Health Assessment 2018). As presented in Figure 1, a study conducted through a collaboration between Alamance County Health Department, Alamance GIS Department, the Guilford County Health Department, and the State Center for Health Statistics shows an 11-year difference in life expectancy between West Burlington and East Burlington, even though this area is where the primary focus of public health interventions has occurred (N.C. State Center for Health Statistics 2019).

Figure 1. Life expectancy (LE) mapping of Alamance County. Moving left to right (west to east) on the above map, lighter orange areas represent predominately White residents who live closer to resources like healthcare and the university. Residents to the east are predominantly people of color, living in neighborhood where there are fewer resources, more poverty, and little economic growth.

There is a growing conversation in the community around root causes of inequity and its effects on health because a developing body of evidence suggests that where you live in Alamance County determines the quality and length of life a resident can expect. Historically, community collaborations have exclusively included social service and healthcare institutions and their leaders and there have been few partnerships with those whose health is most impacted by these issues.

Key Steps in Partnership Development and Shared Capacity Building

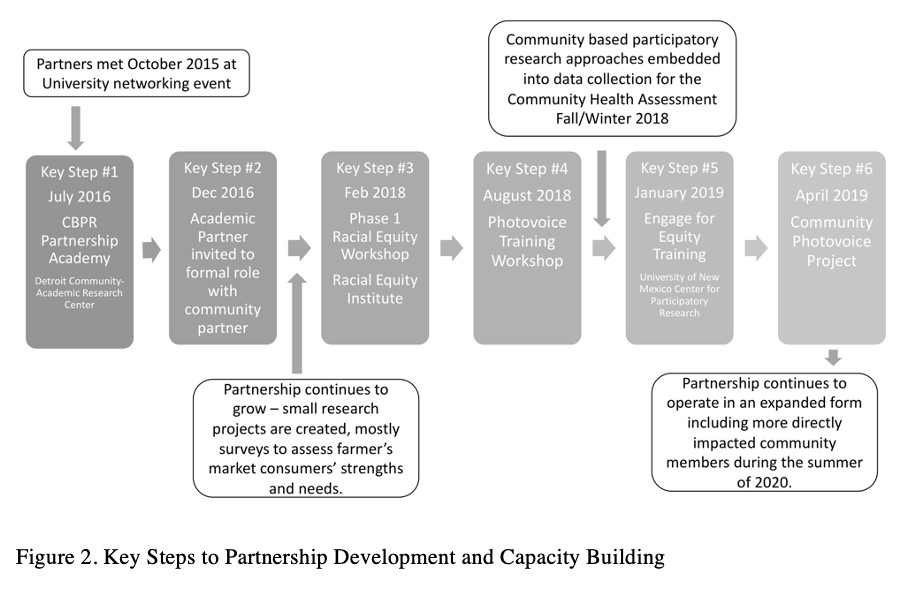

Figure 2 presents the six key steps in our partnership development and shared capacity-building process. While they are shown linearly, there was iterative movement back and forth between steps over the course of time.

Figure 2. Key Steps in Partnership Development and Capacity Building.

Step 1. Our first step involved a commitment to co-learning about the CBPR approach. Although the academic partner had previous experience with CBPR, learning alongside the community partner was an effective strategy to manage power dynamics with respect to knowledge. Soon after our initial meeting, the Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center (Detroit URC) released an application for a CBPR Partnership Academy, a year-long opportunity to support the development of community-academic partnerships (https://www.detroiturc.org/cbpr-partnership-academy.html) (Coombe et al. 2018). The five main components of the Partnership Academy included: ‘a weeklong intensive course, development and implementation of a partnership development planning grant, mentoring by an expert community-academic pair, structured online learning activities and peer exchange, and an ongoing network’ (Coombe et al. 2018). Our partnership applied for and was selected to participate in this program, and our participation resulted in a more defined and developed partnership in several ways. The community partner received formal training in the CBPR approach and examples of existing CBPR partnerships, through which they gained an in-depth understanding of the history of CBPR and its research methodology. We were thus able to more clearly delineate our work as separate and different from our previous community engagement efforts that typically involved working with a class for a semester-long project. We agreed to focus our partnership on the issue of health equity – broadening our partnership to extend beyond its narrower focus on a Farmers’ Market in a neighbourhood with low access to affordable fresh fruit and vegetables – and to think more deeply about food as a tool for equity.

Our participation in the CBPR Academy also led to writing a small seed grant proposal for our first research project. The development of the proposal was accomplished with strong support from the Academy’s assigned academic and community mentors in the form of conference calls and email exchanges to assist with planning and problem solving, and written feedback on the actual proposal. The grant was agreed and the project included survey data collection from customers at North Park Farmers’ Market, a market originally created with a goal of improving food access in a neighbourhood classified as a food desert. While the initial development and implementation of the farmers’ market intervention included surveying the community, it did not adopt a CBPR approach.

Step 2. A second intentional step to strengthen partnership development was to create more structured ways for the academic partner to be a part of the ongoing work of the community organisation. The academic partner was invited to become a member of the Farmers’ Market Steering Committee and eventually was invited to join the Healthy Alamance Board of Directors as an academic liaison for Healthy Alamance. This role was the first of its kind for the Board. The expertise of the faculty member helps to centre community engagement and partnership, and examine problems and solutions through an equity lens, while formalising the relationship between Healthy Alamance and Elon University. Additionally, it allows for discussion involving a broad cross-section of Board members, from elected county commissioners to institution leaders and farmers, on health equity for Healthy Alamance and their work. These conversations have influenced more organisations to provide racial equity training for their employees and to incorporate intentional community engagement strategies into their work.

Step 3. In order to align our goals for the partnership, we realised there was also a need to align our theoretical perspectives and analytical lenses on the causes of racial health disparities. The academic partner had previously committed to using a racial equity lens in their work and the community partner saw this lens as appropriate and applicable to their work. Therefore, the community partner attended a two-day Phase I Racial Equity Workshop delivered by the Racial Equity Institute in Greensboro, NC (https://www.racialequityinstitute.com). This workshop introduced a historical, structural, systemic and institutional analysis of racism in the United States. The academic researcher also attended this workshop, but as an alumna, because she had previously attended multiple times, was a local organiser of these trainings in her home community and utilised this lens in her work. Having the community partner attend the workshop increased the capacity to apply racial equity analysis in their shared work in two main ways: (1) it created a common language around health inequities and (2) it emphasised analysis of the ways in which structures and systems can lead to inequitable health outcomes among communities of colour.

Step 4. The next step involved co-learning around specific engaged methodologies. The community partner was previously involved in implementing a photovoice project and desired to use this method in their partnered work, but the academic partner did not have experience with photovoice. Therefore, Step 4 involved organising a two-day Photovoice Training Workshop to strengthen their shared capacity to conduct qualitative research. Photovoice is a participatory action research approach where people create and talk about photographs with the goal of inducing personal and community change (Wang et al. 1998). Both the academic and the community partner attended as participants and invited other community and organisation representatives to participate as well. The workshop prepared participants to facilitate a photovoice project, emphasising the importance of skill development in focus group moderation. The capacity-building workshop was intended to support our ability to involve all partners in qualitative data collection for a planned Community Health Assessment (CHA). The state requires every county to submit a CHA every three years. While, historically, Alamance County has been recognised for partnering with public health hospitals and social services to produce the assessment, no consideration had been given to including community residents as partners and stakeholders.

Step 5. A fifth key step in partnership development and capacity building included committing ourselves to evaluate and reflect on the state of our partnership. We had the great fortune to participate in an Engage for Equity training workshop, which was developed by a partnership of the University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research, the University of Washington, Community-Campus Partnerships for Health, the National Indian Child Welfare Association, University of Waikato New Zealand, Rand Corporation, and a Think Tank of Community and Academic CBPR Practitioners (Leider et al. 2015). The two-day participatory workshop focused on sharing tools and resources to enhance partnership reflection and growth. Prior to participation, we completed surveys to evaluate the key components or promising practices of our partnership, or strong CBPR partnerships identified by Engage for Equity. At this workshop we created an historical timeline for our partnership, engaged in a visioning exercise using the CBPR Conceptual Model developed by the Engage for Equity team to identify goals for our work, reflected on the results of our survey for promising practices, and participated in knowledge sharing and exchange with other CBPR teams in attendance. During the workshop, we realised that we needed more community members and more people directly affected by health inequities to be a part of the foundational partnership team, which led to a photovoice project.

Step 6. In our final partnership development step, we co-created an actual research project. Both partners worked together to organise a five-week photovoice project to engage more members in the community-academic partnership. We recruited participants in a variety of ways, including by email, social media and phone, from those who had participated in focus groups for the CHA, attended a Community Forum where findings from the CHA focus groups were reported back to the community, and other stakeholders identified from participation in health-related activities and organisations. To demonstrate shared power, we hired an outside facilitator so that we could be participants like all other attendees. Our goal of the photovoice project was to involve all participants in making decisions about the direction this community-academic partnership would take to address health inequities in Alamance County using a CBPR approach. In addition to developing weekly themes connected to the topic of health equity in Alamance County, we introduced the CBPR approach to participants, provided examples of successful partnerships, for example, the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative (greensborohealth.org) in Greensboro, NC, and intentionally emphasised shared decision-making, shared power and shared leadership in keeping with core CBPR principles as described above.

Discussion: Achievements and Lessons Learned

The partnership’s achievements included: (1) embedding a CBPR approach within a farmers’ market

survey and making adjustments to operations; (2) forming a community health assessment and forum;

(3) disseminating our work to the community and at professional conferences; (4) organising community-academic CBPR training in the community over two days; and (5) planning for a forthcoming Community of Practice on CBPR for university staff and faculty. We believe that our commitment to partnership development was critical to these accomplishments.

Below we focus on the major lessons learned across the six steps of partnership development and capacity building.

Step 1 Lesson: Co-learning about the CBPR approach

We learned that to create a successful and long-lasting partnership we must dedicate time to partnership development, commit to regular meetings and adhere to those commitments, utilise the support offered from mentors, and create momentum to continue the journey. Mentors emphasised the importance of valuing the needs of community partners, sharing information with stakeholders and community members, and considering the needs of the academic partner in publishing findings in journals and presenting at professional conferences.

Step 2 Lesson: Structured involvement

There is great value in having both the community partner and the academic partner together at decision-making sessions. This communicates to others that power sharing and shared decision making happen consistently and that the organisation is serious about taking a CBPR approach to its work. This serves as checks and balances for the board on issues related to equity and community involvement.

Step 3 Lesson: Partner alignment on issues of race and racism

In order to authentically address racial inequities in outcomes, those working together must have a shared understanding of the structural and systemic nature of racism and how it affects the communities they are serving. Race was evident in our partnership: the community partner is White, the academic partner is Black, and the communities in which many of the health inequities are experienced are communities of colour. The County itself has a complicated and painful history of racism that contributes to present-day realities regarding race. Participation in the workshop opened up space to have honest conversations about race and racism, particularly on how it may influence our work.

Step 4 Lesson: Partner co-learning in engaged research

Training other colleagues in CBPR approaches is critical to accomplishing tasks that require people power. Increasing the capacity of colleagues to support focus group data collection was necessary to be able to embed CBPR approaches in the County’s Community Health Assessment (CHA).

Step 5 Lesson: Intentional self-reflection and evaluation

As we traced the history of our partnership through visioning and reflection activities, a noticeable gap in active and consistent participation from those living in the community was clearly identified. An expansion of our partnership was needed in order to centre the voices of those most impacted by health inequities in our work.

Step 6 Lesson: Co-creating a research project

There is a desire among community members to have an active role in improving health equity in the County. Many community members have been harmed in the past by feelings of tokenism and have felt that their contributions have not been valued or taken seriously. This five-week process, led by an external facilitator, was essential to recognising the imbalance of power in the relationship and the need for a more authentic approach to the partnership.

Conclusions

This partnership development and capacity-building experience may provide other similar community and academic partners with strategies for partnership development. Our partnership, whch started in October 2015, has lasted almost six years, and there is no intention to end it. It demonstrates the benefits of expanding an undergraduate Public Health Department’s capacity to participate in community-engaged research with their local communities, particularly by investing in authentic relationships with those most impacted by health inequities.

CBPR partnerships can be created in communities where resources to support the work are limited. While some of the specific co-learning opportunities, with which this partnership engaged, were unique, time-specific and based on grant-funded training programs, both the Detroit Urban Research Center and University of New Mexico Engage for Equity groups maintain active websites offering resources and tools for partnerships to utilise. In order to be successful, partners need to allocate time to the development of the partnership and seek ongoing training and funding opportunities, while intentionally embedding the partnership into the institutional structure of their respective agencies. The next phase of our work will include implementing the strategies and activities that the newly expanded partnership has identified and integrating undergraduate students more intimately into the work of the organisation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our community partners in Alamance County and our mentors, Ricardo Guzman, Dr Barbara Israel and Dr Nina Wallerstein, for their guidance during our partnership development and growth, and subsequent dissemination strategies.

References

AccessNC Dashboard n.d., viewed 7 September 2019, https://accessnc.nccommerce.com/

Alamance County Community Health Assessment 2018, viewed 26 April 2019, www.alamance-nc.com/health/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2019/04/CHA-2018-Alamance-County.pdf

Allen, M, Culhane-Pera, K, Pergament, S & Call, K 2011, ‘A capacity building program to promote CBPR partnerships between academic researchers and community members’, Clinical and Translational Science, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 428–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00362.x

Barnes, M, Wykoff, R, King, L & Petersen, D 2012, ‘New developments in Undergraduate Education in Public Health: Implications for Health Education and Health Promotion’, Health Education & Behavior, vol. 39, no. 6, pp. 719–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198112464496

Caron, R 2013, ‘Teaching epidemiology in the digital age: Considerations for academicians and their students’, Annals of Epidemiology, vol. 23, no. 9, pp. 576–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.06.001

Coombe, C, Schulz, A, Guluma, L, Allen, A, Gray, C, Brakefield-Caldwell, W, Guzman, J, Lewis, T, Reyes, A, Rowe, Z, Pappas, L & Israel, B 2018, ‘Enhancing capacity of Community–Academic Partnerships to achieve health equity: Results from the CBPR Partnership Academy’, Health Promotion Practice. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839918818830

Corbie-Smith, G, Bryant, A, Walker, D, Blumenthal, C, Council, B, Courtney, D & Adimora, A 2015, ‘Building capacity in Community-Based Participatory Research Partnerships through a focus on process and multiculturalism’, Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 261–73. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2015.0038

Israel, B, Parker, E, Rowe, Z, Salvatore, A, Minkler, M, López, J, Butz, A, Mosley, A, Coates, L, Lambert, G, Potito, P, Brenner, B, Rivera, M, Romero, H, Thompson, B, Coronado, G & Halstead, S 2005, ‘Community-Based Participatory Research: Lessons learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research’, Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 113, no. 10, pp. 1463–71. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.7675

Israel, B, Schulz, A, Parker, E & Becker, A 1998, ‘Review of Community-Based Research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve Public Health’, Annual Review of Public Health, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 173–202. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173

Leider, J, Castrucci, B, Plepys, C, Blakely, C, Burke, E & Sprague, J 2015, ‘Characterizing the growth of the Undergraduate Public Health Major: U.S., 1992–2012’, Public Health Reports, vol. 130, no. 1, pp. 104–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491513000114

N.C. State Center for Health Statistics, 7 September 2019, https://schs.dph.ncdhhs.gov/

Nelson-Hurwitz, D & Tagorda, M 2015, ‘Developing an Undergraduate Applied Learning Experience’, Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 3. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2015.00002/full. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2015.00002

Parker, D, Dietz, N, Hooper, M, Byrne, M, Fernandez, C, Baker, E, Stevens, M, Messiah, A, Lee, D & Kobetz, E 2012, ‘Developing an Urban Community–Campus Partnership: Lessons learned in Infrastructure Development and Communication’, Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 435–41. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2012.0058

Piedmont Health Counts :: Demographics :: County :: Alamance n.d. http://www.piedmonthealthcounts.org/demographicdata

Riegelman, R & Albertine, S 2011, ‘Undergraduate Public Health at 4-Year Institutions: It’s here to stay’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 226–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.013

Selected Indicators for Alamance County, North Carolina, KIDS COUNT Data Center n.d. https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/customreports/4910/any

U.S. Census Bureau Quick Facts: Alamance County, North Carolina n.d. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/alamancecountynorthcarolina

Wallerstein, N & Duran, B 2006, ‘Using Community-Based Participatory Research to address health disparities’, Health Promotion Practice, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 312–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839906289376

Wang, C, Yi, W, Tao, Z & Carovano, K 1998, ‘Photovoice as a participatory health promotion strategy’, Health Promotion International, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/13.1.75

Yeatts, K 2014, ‘Active Learning by Design: An Undergraduate Introductory Public Health Course’, Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 2. www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00284/full. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00284