Cultural Studies Review, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2018

ISSN 1837-8692 | Published by UTS ePRESS | http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index

NEW WRITING

Live Free or Die Motionless: Walking the Migrant Path from Italy to France

Karina Horsti

University of Jyväskylä

Corresponding author: Karina Horsti, Keskussairaalantie 2, Building Opinkivi, University of Jyväskylä, FI-40014, karina.horsti@jyu.fi

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/csr.v24i2.5923

Article History: Received 27/02/2018; Revised 29/08/2018; Accepted31/08/2018; Published 28/11/2018

Citation: Horsti, K. 2018. Live free or die motionless:Walking the migrant path from Italy to France. Cultural Studies Review, 24:2, 56-66. https://doi.org/10.5130/csr.v24i2.5923

© 2018 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

A discarded men’s suit in the bush, with a toothbrush, a razor and a comb poking out of its pocket, is the first indication that the trail I am on is the sentiero della speranza, the Path of Hope. An elderly Italian woman had helped me to get off the bus at an undesignated stop when I asked the passengers where the path was. But after that I just relied on my instinct. There were no people to ask for more directions. The Path of Hope links the village of Grimaldi in the far northwest of Italy with Menton on the French side of the border. Some have walked this path to avoid border controls regulating travel by train or car between Ventimiglia on the Ligurian coast and Menton on the Côte d’Azur. Throughout the twentieth century, anti-fascist émigrés, Jewish refugees, and Italian migrants walked the sentiero towards a better life. They included Robert Baruch, a Jew from South Tyrol in Italy, who drew a map of his escape from persecution in 1939 and sent it back to his community in Merano so that others could follow him1. In the dark of night, the track across the mountains is perilous; those taking a wrong step might fall to their death like Italian baker named Mario Trambusti in 1962. And this is why the path also carries the name passo della morte, Pass of Death.

Today, most people cross from Italy to France by rail or road without noticing the presence of a nation-state border. As cars pass between two tunnels on the highway, only the flash of a simple sign informs drivers that they’ve crossed an internal European Union border. Official border controls were abolished in 1997 when Italy began implementing the Schengen Agreement. Currently, twenty-six European Union countries are part of the Schengen area and do not have internal border controls. Up on the mountain, an old fence is the only reminder that the border was once controlled. Or, this is how it appears to European Union citizens and, more importantly, white EU citizens. An Italian jogger running with his dog, whom I came across after I had found the men’s suit, assured me that I would have no problems hiking in the area; the border police would only be interested in the ‘clandestini’. For those who are non-citizens or appear to be ‘migrants’, this is a landscape where the border becomes visible and manifests its violence.

Image 2: View from the Italian side of the Path of Hope towards Menton, France. The fatal motorway cuts through the mountains. Photos by Karina Horsti

In the summer of 2015, the year of the European refugee reception crisis, internal European border controls, which had already seemed to belong to a distant past, were making a comeback. The Schengen Agreement allows temporary border controls in the case of, what the European Commission2 terms, ‘serious threats’. A woman who offered me a ride to the train station in Mentonwhen I asked for directions complained that the frequent identity checks were a nuisance because they slowed down traffic. But the French were merely inconvenienced and, anyway, they weren’t the targets. Those who were to be prevented from crossing the border, and subjected to racial profiling by the French border guards, were migrants from North and Sub-Saharan Africa. To cross the border, the non-citizens tried to look like they belong; they prepared for the journey by getting haircuts, buying new clothes, or carrying Le Monde. The police caught them anyway, put them in a van, and drove them back to Italy. In Ventimiglia, the Italian town closest to the border, migrants slept in the railway station. Others congregated in parks, waiting for an opportunity to move on or return back a temporary home in northern Europe. Many of the migrants had returned to Italy from countries such as Germany, because they needed to renew their Italian residence permits. Identity checks at the border didn’t really prohibit movement but punished and disciplined the mobility of certain people. They also made the crossing violent. In the tunnel of the motorway, below the Path of Hope, a 17-year old Eritrean girl died in October 2016 when she was hit by a car while walking to France.

Image 3: The ruins of Gase Gina have offered a shelter along the Path of Hope since 1944 when the French soldiers bombed the farmhouses.

*

I leave the men’s suit in the bushes and continue walking the path. It’s early May but for me, coming from Finland, the sun is warm. The smell of the pine trees wraps me into a feeling of safety, a familiarmemory of the Finnish forests. The path leads me to a complex of ruined houses, Case Gina. Later I hear from the local historian Enzo Barnabà that these ruins were a complex of farmhouses until 1944, when French soldiers bombed them believing that Germans were sheltered there3. It is cool inside the ruined buildings, the wind blows through broken windows, and entering each new room shakes me. The thought that no one would see if something bad happened to me doesn’t leave me. I try to walk carefully and quietly through the derelict rooms and piles of old clothes; shoes and the remains of food packages reveal that people have sought shelter here very recently. But I come across no one.

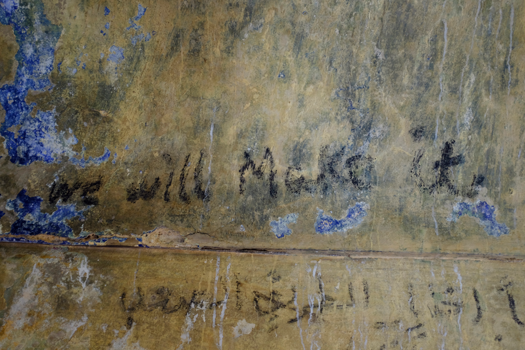

This abandoned place conveys a simultaneous sense of the past and of the future. Who were here before me and what happened to them? While the idea of not-being-seen makes me shiver in the ruins of Case Gina, others must have sought protection here. I wonder who hid from the gaze of the border guards in French helicopters that patrol the path from the air to monitor the movement of migrants. Scribbles and scratches on the walls convey the hopes and fears of those who have passed by this transitional shelter.

‘We will make it’

‘Death to the smuggler’ (in French)

‘Dangerous road’ (in Arabic)

‘Malta, Italia, France, Canada, Australia, Malaysia, Inshallah’ (in Arabic)

‘The sky is for everyone’ (in Arabic)

‘If you have to live, live free! Or else die motionless, like the trees, motionless’ (in Arabic)

Image 4: We will make it. Fresco of transcultural memory on the walls of Case Gina

The mix of languages and scripts in these ruins reveals the memories shared between those who traveled without documents. It creates a fresco of transnational memory. The graffiti reminds me of other similar places that I have heard about: migrants have scribbled their messages in prisons in Libya, warehouses where traffickers hide migrants, caves in the Sinai mountains, squats in Italy, holding cells in police stations, reception centers and camps across Europe. In all these transitory places, some more confined, and some more long-term than others, migrants have shared hopes, fears, frustrations and longings by writing on the walls. Inspired by those who went before them, they add their own graffiti. Connecting places and ideas they create memory that crosses temporal and spatial boundaries.

In the Case Gina, one person had thought of Mohammadia and Ain Kihal, two towns in Algeria. Another had hoped to reach Canada. Ahmed loved a woman named Alima. These graffiti reveal the recent history of mobility in this area. They point to the multiple directions from which people came and to which they were going. The graffiti also signify that this shelter is not a wasteland, contrary to the common understanding of abandoned places and ruined buildings4. The ruins of the Case Gina can be viewed as a site of alternative communication: encouragement and warning among those hiding from authorities. Even though invisibility is what people sought in this place, many desired to make their presence and journey known.

Image 5: Layers of histories and spatial links merge in the ruins of Case Gina, creating a site of multidirectional memory.

The significance of this place was amplified when the Case Gina provided a mise-en-scene in the award-winning 2014 Italian documentary Io sto con la sposa/On the Bride’s Side5. The film’s protagonists had first made an unauthorized entry into the Schengen area by crossing the Mediterranean from Libya to Italy in overcrowded boats. But Italy was not their destination: they wanted to go to Sweden. The film depicts Syrian and Palestinian asylum seekers on a clandestine journey from Milan to Stockholm. Thinking that the police would not check the papers of a wedding party, the protagonists masquerade as such, and successfully cross the Schengen area’s internal borders. The border crossings between Italy and France, France and Luxemburg, Luxemburg and Germany, Germany and Denmark, and Denmark and Sweden are barely visible to European citizens, but the film allows its audience to see a different emotional geography of Europe. The film reveals how borders that have disappeared for some can be an anxious experience for others. After each crossing there is a sense of relief.

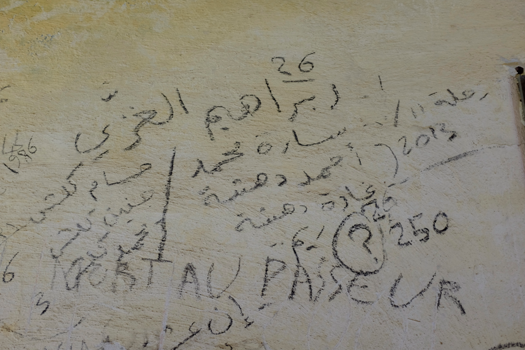

In order to cross their first Schengen border, the protagonists walk the Path of Hope, sentiero della speranza. Palestinian man Abdallah Sallam survived a shipwreck near the Mediterranean island of Lampedusa in 2013 and witnessed the deaths of some 250 people. In one scene, inside the ruins of the Case Gina, he carves the names of the people he met during the journey but who did not survive the Mediterranean crossing. By evoking memories of his fellow travelers who were lost at sea, those who could and should have been here at this border crossing with him, hoping for a future in Sweden, he brings different temporalities into the same scene. By writing their names in black coal on the wall, he identifies the lost migrants and recognizes that they could have been with him in the present.

Image 6: During the filming of Io sto con la sposa documentary, in the ruins of Case Gina, Palestinian Abdallah Sallam carved the names of people who died in the shipwreck he survived.

I think about the commemorative aspect of the scene and how it is particularly powerful when I stand in front of his graffiti in the ruined building. The scene in the film is so impressive because Sallam relates his memories of each person as he writes their names in Arabic.

Sara Mohammed was the sweetest girl I have ever known. I love her like she was my own. God bless her. Ahmed Danshe. Ghada was Ahmed’s sister. The most beautiful girl and boy. Hossam Kalash was a boy I stayed awake with talking the night before the ship sank. He was a friend, a brother to me although we had just met.

This scene of commemoration resists the idea that the more than 30, 000 known deaths in the past 20 years at Europe’s borders6 would be a normalized part of irregular migration. It does so by individualizing the dead by naming and by showing the relationality of the people: Ghada was Ahmed’s sister, Hossam was a friend, like a brother. The scene also invites the spectator into an intimate circle of collective listening and mourning. While Abdallah Sallam recites the names, the camera moves to his fellow travelers standing in the derelict room. Their participation in the ritual is silent and dignified. At the end of the scene, another protagonist in the film, Syrian activist Tasnim Fared hugs Abdallah Sallam and says, ‘You are here. We are here and we keep on going’.

This landscape of the sentiero della speranza and the ruins of Case Gina provide a powerful backdrop for mourning the dangerous border crossing at another location, at the Mediterranean Sea. By bringing these two crossings together in one scene through the performance of commemoration, the documentary film Io sto con la sposa creates a comparative memory of the two border zones and the associated violence. The border zones are not equal sites and the memories are not of equal events, but their co-presence opens up critical attention to the different kinds of borders in Europe, external borders and the internal Schengen borders.

Image 7: Discarded objects in Case Gina elicit imaginaries of individuality and intimacy. Did a child get better shoes and left these behind? Were the shoes left for someone who might need them?

While I saw the traces of former and present day bordering along the Path of Hope, the walking from one country to another also revealed that borders not only separate but also connect people. The place also has traces of local solidarity towards migrants. It was difficult to identify the unmarked beginning of the path in Grimaldi but the two-hours trek itself was easy. Local hikers and cultural activists had just cleared the path in 2015 when the alternative route began to be more important again.They wanted to make the crossing easier for the migrants who often walked at night. Moreover, it was difficult to spot the small opening in the old border fence in daylight. Italian artist Andrea d’Amore Espanso used fluorescent green to paint the word HOPE on a piece of metal above cut in the fence. This installation shines like an emergency exit in the dark, pointing towards the right direction. It transforms the meaning of the border from an exclusive wall of separation and selection into an open door that welcomes everyone who goes through it.

There is a network of locals in the mountain regions along the border who help migrants in multiple ways. New York Times7 termed the network as ‘The French Underground Railroad’ in reference to the safe houses and secret routes in the United States that helped the African American slaves to escape from the South to the North. People give food, clothes, rides and shelter. ‘We live in the mountains. Here we never see someone stuck by the road without getting help. There were three very young people walking on the road. They had to be helped because they were soaking wet,’ says one local of Breil-sur-Roya8. This is a common response from the locals on both sides of the border. The people refuse to witness the suffering of others and to look the other way. The most well-known of the ‘French Underground Railroad’ people is Cédric Herrou, a French farmer to whom the court ordered a four-month suspended sentence as a ‘warning’9; a decision that the Constitutional Council later ruled unconstitutional because the assistance was ‘a humanitarian and disinterested action’.10 Herrou became a media celebrity and many likened him to the French who protected Jews by hiding during the Second World War.11 He refuses to be termed as a smuggler, even a humanitarian one, because a smuggler deals with goods. Cédric Herrou meets each person as a human being:

These people are not cardboard boxes. These are people who have families waiting for them, who are in love with a man or a woman. They are parents who love their children, children who love their parents. They are children who cry that their parents are held in Italy or who died. They are people with desires and emotions, and a hope for the future.12

Moreover, the people in this border region also see the attempt to migrate not that different from their own past. Herrou walked into the courthouse in Nice through a mass of supporters who protested by shouting: ‘We are all children of immigrants! First! Second! Third generation!’

The memory of the past clandestine mobility and protection of vulnerable people in the region emerges also in Italy in connection to present day migration. The Path of Hope and the other routes that cross the border in the mountainous region were remembered by parliamentarians who spoke in favor of a law proposal for a national Memorial Day for ‘victims of immigration’ in the Chamber of Deputies in Rome on 13 and 15 April 2015.The national day itself is 3 October, which refers to a disaster near the island of Lampedusa in 2013, which caused the drowning of at least 368 refugees mainly from Eritrea. Luigi Famiglietti was one of those politicians who argued for a parallel between the suffering of the past and present migrants, reminding that Italians were once ‘illegals’ who suffered at the fatal border on their way to France: ‘Every night more than a hundred illegal Italian immigrants tried to cross the border in that area and there were a minimum of two deaths a month’, he said in the parliamentary debate13.

*

Walking the path from Grimaldi to Menton, thinking of the film Io sto con la sposa’s depiction of borders, watching the border games at the railway stations in Menton and Ventimiglia, reading the material traces along the Path of Hope and listening to the experiences of the locals and the migrants allowed me to imagine layers of different histories of illegalized mobility etched into the landscape. I wondered: How are these histories related? Do the different pasts compete with each other? Which of the people who either walked the path for a better life or who facilitated the crossing are remembered? In Grimaldi and Menton, locals talk about creating a memorial for people who have used the sentiero, but which border crosser would be remembered? Would the memorial be about an Italian who escaped fascist rule, a Jew who escaped persecution, an Italian labor migrant, or a more recent refugee from North Africa, Sub-Sahara, or another contemporary conflict zone?

Would it be possible to interconnect memories and movements, in much the same way in which Abdallah Sallam connected the different borders in the commemorative performance in the film Io sto con la sposa? According to the local historian Enzo Barnabà, the solidarity towards present-day migrants in Grimaldi is linked to a memory of Italians as migrants14. Once the Italians were the ones who were unwelcome, and this memory of the past prompts potential for solidarity towards the migrants in the present, he says. Similarly on the French side, parallels to the action and inaction towards the persecuted Jews constantly emerge as a justification for solidarity towards the present day border crossers.

In my view, the Path of Hope offers the possibility to go beyond competitive memory politics and see the interacting layers of histories and transnational memories as an opening to temporal and spatial solidarities. On the one hand, the past is actualized through the present migration and on the other hand, the past creates a framework to understand the present. The merge of past and present mobilities in this landscape offers an opportunity to imagine a broader vision of humanity and human rights. Therefore, sensitivity to learning from such sites as the sentiero della speraza and the ruins of Case Gina is crucial in the struggle to imagine a cosmopolitan vision of the landscape. These are memory sites that have critical potential to articulate alternative politics of mobility in the increasingly narrow mainstream political opinions in Europe.

This perspective is inspired by Michael Rothberg’s notion of multidirectional memory, which theorizes the interaction of different memories and suggests that memory is inherently created through cross-referencing and borrowing.15 Remembrance cuts across and binds together different spatial, temporal, and cultural sites in ways that can foster either exclusion or solidarity. The memories of different borders, diverse places and times that emerge and intersect at the sentiero della speranza reveal how memory travels with people, crosses boundaries and leaves traces. Path of Hope is a multidirectional memory site where one can combine different temporalities and spatial links and actualize the potential for seeing the issues of migration and mobility in contemporary Europe in a more sustainable light.

The multidirectional memory potential of the Path of Hope is linked to three interconnected frameworks. First, remembering labor migrants and those escaping fascism reminds Italians that they were once the rejected ones in Europe, opening a possibility of hospitality and solidarity towards the present migrants. Second, the Arabic script and the names of places in Algeria on the walls of Case Gina communicate multidirectional spatial and temporal connections that evoke transcultural memories of colonialism. The nation-state that so determinedly wishes to reject the mobility of some people – France – has a colonial past that is plainly evident in this landscape. The word algerien (‘Algerian’) on the wall at this specific site strongly points to colonial domination and French violence in the Algerian war. The mobility in this region is not arbitrary.

Third, the memory of Jewish escapees during the Holocaust opens another cosmopolitan horizon to understand the condition of contemporary refugees. The story of Baruch’s escape from the Austrian border area through the Path of Hope in 1939 reappears in the collective memory of the path among local people.16 Why is this particular story recalled? Some scholars, including Andreas Huyssen17 and Daniel Levy and Natan Szneider18 have argued that the Holocaust has become a site of cosmopolitan memory, a universalizing symbol of evil that is capable of creating transnational solidarity. To some extent, its accelerated remembrance in Europe and the United States since the 1980s has decontextualized the memory of the Holocaust in ways that now produce a vehicle for broader human rights claims. Actualized on the sentiero della speranza, the connection between Baruch’s escape of Fascism creates a sympathetic framework for publics beyond Italy to interpret the present day movement of migrants.

Nevertheless, as Klaus Neumann has argued, ‘a memory is never just there already––as if only temporarily in storage. It needs to be invoked, conjured, made’.19 The landscape of Path of Hope, the remains of taking shelter and the graffiti in Case Gina can be read as memories of bordering and crossing––but someone needs to invoke and make the memory, to remember. This is what I have tried to do in writing this essay and by walking the Path of Hope, talking to migrants and locals along the way, revisiting the photographs I took, watching the documentary film and reading about the place and its people. Such approach that avoids a linear narrative, brings multiple perspectives together, and listens to different voices from different temporalities simultaneously is a reflective and experimental mode of writing.20 To this end, I have also acknowledged the memory work of other mnemonic agents: Grimaldi historian Enzo Barnabà, the French activists, Italian parliamentarian Luigi Famiglietti, the journalists who write about the border violence, and the filmmakers and protagonists of Io sto con la sposa. And most importantly, I have listened to the migrants who by adding to the writings on the walls conjure memories of different border crossings, unequal relationships, and connections to places. By doing that, they both remember border-crossings and create a vernacular transnational memorial, a trace to be read by those who walk by.

In addition to the interconnected histories, my experience of the ruins of Case Gina has revealed relevant comparative imaginaries in the present. The marks and discarded objects in the ruins link memories of different places – including different border zones and their associated violence – in ways that allow us to critically examine borders as something performative: they are created and they have consequences. In a globalized world, borders have become increasingly dispersed and hidden from the eyes of the privileged citizens.

Acknowledgments:

The author would like to thank Enzo Barnabà for sharing his knowledge, and Klaus Neumann and the anonymous referee for thoughtful comments on this paper.

Notes

1. Robert Baruch’s map dating to 1939 is archived in the municipality of Bolzano, Italy and was published in Paolo Veziano, Ombre al confine: L’espatrio clandestine degli ebrei stranieri, Fusta editore, Saluzzo, 2014 and in San Remo News, (n.a.), ‘Ventimiglia: domenica 12 aprile grande ‘Picnic dell’Amicizia’ sul Sentiero della Speranza’, San Remo News, 8 February 2015.

2. European Commission, Europe without borders: the Schengen area. Brussels: European Commission.

3. Enzo Barnabà, phone interview with the author, 17 July 2015.

4. Tim Edensor, Industrial ruins. Space, aesthetics and materiality, Berg, Oxford: Berg, 2005, p.5.

5. Directed by Antonio Augugliaro, Gabriele Del Grande & Khaled Soliman Al Nassiry.

6. Several academic, activist, and intergovernmental project produce fatality metrics. Tamara Last and Thomas Spijkerboer, ‘Tracking deaths in the Mediterranean’, in Tara Brian and Frank Laczko (eds.), Fatal Journeys: Tracking lives lost during migration, International Organization for Migration, Geneva, 2014, pp. 85 – 107. Simon Robins, Iosif Kovras and Anna Vallianatou, ‘Addressing migrant bodies on Europe’s Southern frontier: An agenda for practice and research’, Working papers in conflict transformation and social justice, Centre for Applied Human Rights. University of York, York, 2014.Last, Tamara (2015, May 12) Deaths at the Borders: Database for the Southern EU, retrieved from http://www.borderdeaths.org/?page_id=425; The UNITED List of Deaths retrieved from http://unitedagainstrefugeedeaths.eu/about-the-campaign/about-the-united-list-of-deaths/; International Organization for Migration, Missing Migrants Project retrieved from https://missingmigrants.iom.int/.

7. Adam Nossiter, ‘An Underground Railroad in France, Moving African Migrants’, New York Times, 5 October 2016.

8. The Valley Rebels, documentary film, Guardian, 28 April 2017.

9. The Local, ‘French farmer gets suspended sentence for helping migrants enter France’, The Local, 8 August 2017.

10. Conseil Constitutionnel, Decision nr 2018-717/718 QPC M. Cédric H. et autre [Délit d’aide à l’entrée, à la circulation ou au séjour irréguliers d’un étranger], 6 July 2018. https://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/decision/2018/2018717_718QPC.htm

11. Angelique Chrisafis, ‘Farmer given suspended €3,000 fine for helping migrants enter France’, Guardian, 10 February 2017.

12. The Valley Rebels, documentary film, Guardian, 28 April 2017.

13. Camera dei deputati, Resoconto stenocrafico, 407, 13 April 2015.

14. Enzo Barnabà, ‘Giornata mondiale del rifugiato, il comment di Enzo Barnabà’, Infinito Edizioni, 2015.

15. Michael Rothberg, Multidirectional memory: remembering the Holocaust in the age of decolonization, Stanford University Press,Stanford, 2009.

16. Barnabà, ‘Giornata mondiale del rifugiato’.

17. Andreas Huyssen, ‘Present pasts: media, politics, amnesia’, Public Culture, vol. 12, no. 1: 2000, pp. 21 – 38.

18. Daniel Levy and Natan Szneider, ‘Memory unbound: The Holocaust and the formation of cosmopolitan memory’, European Journal of Social Theory, vol. 5, no. 1: 2001, pp. 87 – 106.

19. Klaus Neumann, Shifting memories: The Nazi past in the new Germany, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2000, p.7.

20. Cultural Studies Review and its precursor, UTS Review, have done much to push that particular mode of writing, often under the label “experimental history”. See, for example, Stephen Muecke, ‘Experimental History? The “Space” of History in Recent Histories of Kimberley Colonialism’, UTS Review, vol. 2, no. 1: 1996, pp. 1-11; Klaus Neumann, ‘But is it history?’, Cultural Studies Review, vol. 14, no. 1: 2008, pp. 19 – 32; Katrina Schlunke, ‘Captain Cook chased a chook’, Cultural Studies Review, vol. 14, no. 1: 2008, pp. 43 – 54; Stephen Muecke, ‘A touching and contagious Captain Cook: Thinking history through things’, Cultural Studies Review, vol. 14, no. 1: 2008, pp. 33 – 42.