Cultural Studies Review , Vol. 24, No. 2, 2018

ISSN 1837-8692 | Published by UTS ePRESS | http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Towards an Ethic of Reciprocity: The Messy Business of Co-creating Research with Voices from the Archive

Rebecca McLaughlan

The University of Melbourne

Corresponding author: Rebeca McLaughlan, University of Melbourne, MSD Building, Parkville , Victoria, 3010. rebecca.mclaughlan@unimelb.edu.au

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/csr.v24i2.5896

Article History: Received 01/02/2018; Revised 06/09/2018; Accepted 10/09/2018; Published 28/11/2018

Citation: McLaughlan R. 2018. Towards an Ethic of Reciprocity: The Messy Business of Co-creating Research with Voices from the Archive. Cultural Studies Review, 24:2, 39-55. https://doi.org/10.5130/csr.v24i2.5896

© 2018 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Abstract

Do contemporary practices of attribution go far enough in acknowledging the contribution that others make to our work, particularly when they speak from the archive? The autobiographical fiction Faces in the Water (1961) from acclaimed author Janet Frame (1924-2004) draws on her experiences of residing in various New Zealand mental hospitals between 1945 and 1953. It is a rare and comprehensive account of the patient experience of these institutions that provided a critical lens for my doctoral research. Perhaps more importantly, through this text Frame taught me how difficult histories should be written, about the ambiguities we must accept and the value adjustments to be made in order to make sense of confounding inhumanity. Nowhere within my dissertation is the depth of this contribution acknowledged; a position developed out of respect for her family’s active opposition to the ‘patronising’ and ‘pathologising discourse’ that continues to haunt contemporary receptions of Frame’s work. Within this paper I employ autoethnography to make explicit the process of working through a question that haunted me well beyond the completion of my doctoral research: whether contemporary practices of citation and acknowledgement are sufficient to value research contributions from beyond the grave. I will examine whether Frame’s contribution is commensurate with contemporary qualifications for co-authorship and the burdens of academic practice that act to suppress these conversations.

Keywords

Janet Frame, authorship, attribution, autoethnography, mental hospitals.

Introduction

Kim Roberts recently observed that architectural historians ‘attend more to the production’ than the ‘reception of spaces … iron[ing] out raw affects into coherent historic narratives … careful to anchor or even bury subjective experience in aggregated and concrete evidences.’ She advocated giving voice to the stories that ‘linger without expression, repressed and uncanny in our memories, field-notes and writings, despite being the silent, nagging fuel of our inquiries.’1 Haunting can strip back the burdens that academic convention layer upon historical research. In differentiating haunting from trauma, Avery Gordon suggests that haunting is accompanied by a ‘something-to-be-done’.2 Haunting does not constitute a simple to do list, of histories to be recovered, ordered and documented, but a pursuit characterised by intangibility. It rests on an intuitive sense that ‘something’ should be done but only through engagement, or perhaps completion, can we hope to identify what that something might have been. I understood that there was an issue outstanding with regard to my doctoral research, but it took three years to name the question that lingered long after the thesis had been homed within its library stack. What haunts me is guilt. Janet Frame, through the texts that she left behind - in particular Faces in the Water - provided the source material that made possible my doctoral research and although she was cited within my dissertation, this contained no formal acknowledgement of her significant contribution. Within this paper I employ autoethnography to examine and redress this oversight; to exhume the issues related to contemporary citation practices in respect of the archival voices that shape and make possible historical research.

In early 2010 I embarked upon a doctoral study of New Zealand’s abandoned mental hospital sites that, languishing in rural backwaters, discarded and dilapidated, struck me as an evocative metaphor for the patients they once housed (Figure 1). I was informed, upon first meeting my supervisors, that I could not begin this project without first reading Frame’s Faces in the Water. Frame, who died in 2004, is regarded as one of New Zealand’s ‘most distinguished’ literary figures.3 The author of thirteen novels (two published posthumously), numerous short stories and a three-part autobiography, Frame was the recipient of several literary prizes, an Order of New Zealand (1990), a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (1983) and two honorary doctorates of literature (University of Otago, 1978; University of Waikato, 1992). While Frame was a unique literary talent, there remains a tension between Frame the critically acclaimed author and Frame the mad former patient. Faces in the Water was positioned as fiction but drew heavily on the author’s experience within three New Zealand mental hospitals spanning the period 1945-1953. Published in 1961, Faces in the Water was written at the encouragement of a psychiatrist Dr Robert Hugh Cawley who recognised the trauma inflicted by institutionalisation and suggested Frame write for ‘cathartic closure.’4

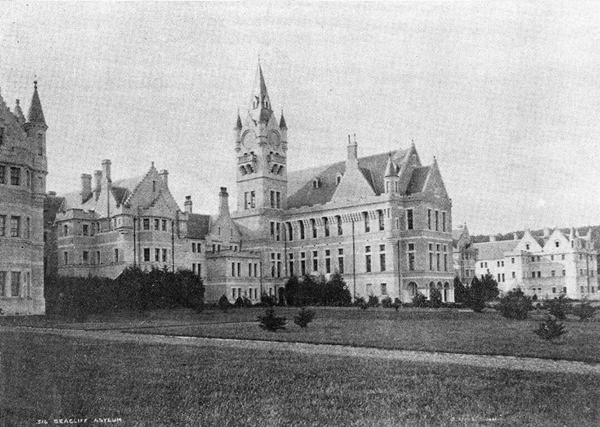

Sylvie Gambaudo has observed that ‘clarifying the relationship between fiction and fact in Frame’s work has preoccupied most of her readers and critics.’5 For me, this preoccupation resided in the silences that seemed to shift and fall between three texts: Faces in the Water (1961), An Angel at my Table (1984; the second book in Frame’s three-part autobiography) and the subsequent addition of Michael King’s biography Wrestling with the Angel (2000). The relationship of Frame’s life experiences to her fiction does not present a problem so much as the enduring inextricability of her ‘madness’ from her talent. Returning to New Zealand as an author of critical acclaim in 1963, Frame ‘discovered a prevalent belief that her work was the product of a ‘mad genius’.6 This trend has not abated. Reviewers of Frame’s posthumously published works seem unable to avoid the temptation of discussing her personal history in advance of reviewing the work in question.7 The Wikipedia entry for Frame, similarly, loses no time in discussing her hospitalisation, stating this within the first four lines before going on to provide a detailed account of the various psychiatrists Frame visited in London during her ‘most prolific’ writing period (1956-1963). A photograph of Seacliff Asylum accompanies this profile (Figure 2).8

Figure 1 The corridor of a patient villa at Seaview Asylum, Hokitika, New Zealand. Photograph by author, April 2010.

Frame’s niece and literary executor, Pamela Gordon, actively fights the omnipresence of the time Frame spent as a psychiatric patient in any discussion of her work. In an interview with the New Yorker, published the same year I commenced my doctoral research, Gordon stated: ‘my major goal has been to try to bring the focus back onto [Frame’s] work in the face of pressure to exploit her personal life.’9 In a more recent publication she has written: ‘An approach of biographical speculation towards Frame’s work has been doggedly influential – in New Zealand at least – and it has set the tone for a patronising attitude and a pathologising discourse.’10 As a historian who has tried to make sense of New Zealand’s mental hospitals - institutions that, at their peak, held more than nine thousand patients11 and whose archival records have been carefully sanitised - I understand the significant and enduring value of Faces in the Water. Without Frame’s novel I could never have grasped what lingered in the silence; to have read the way that architecture encodes behaviour when there was no one left to observe. I tried to express my gratefulness for its existence to Gordon, upon meeting her at a literary event in 2015, just weeks after handing in my thesis. She was not interested in hearing it.

More than two decades after its publication, Frame confirmed that Faces in the Water resided much closer to reality than she’d initially suggested.12 The veracity of Frame’s account is evident in the fact that it so closely echoes the observations made by Erving Goffman in Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates, published in the United States the same year. Goffman was a sociologist and spent twelve months as a passive observer at St Elizabeth’s Psychiatric Hospital in Washington, D.C. The resulting publication has been labelled ‘a devastating critique of the realities of mental hospital life’ and a clear illustration that ‘little that could be described as therapeutic was found in the asylum.’13 Goffman’s book revealed the detrimental effects to a patient’s self-esteem that resulted from the strict daily routines, the forced use of collective space and the social hierarchies that accompanied asylum life. Accounts by former staff of New Zealand’s mental hospitals confirm that Frame’s experience was by no means unusual.14 The Confidential Forum for Former In-patients of New Zealand’s Psychiatric Hospitals reported on the experiences of four hundred and ninety-three former patients and consolidated Frame’s personal experience as being more common than might otherwise be assumed.15

Figure 2 Seacliff Psychiatric Hospital, Dunedin, ca.1910, photographer unknown. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand,1/2-002563;F

I have empathy with Gordon’s desire to disassociate Frame’s work from her personal history. But the question must be asked, does this desire supersede the ethical responsibility to acknowledge the magnitude of Frame’s contribution to my own, and any subsequent, scholarship on New Zealand’s history of institutionalisation for mental illness? It should also be recognized that Frame’s work has performed as more than simply an archival account. It was published at a time when institutional care was still the norm for New Zealand’s mentally ill and Warwick Brunton has confirmed that Faces in the Water was thought to be so ‘perceptive’ regarding the patient experience that it was used for the purposes of training mental hospital staff for a number of years following its publication.16 This this raises broader questions about the ethics of curating the contributions of ourselves, or others, to history and to scholarship. What interests me here, however, is how I, as a researcher with a firm belief in reciprocity, failed to even consider a formal acknowledgment (beyond citation) of Frame’s essential contribution to my work? Within any field of research, accepted methods and ontological positions act to establish and ingrain disciplinary practices.17 The burdens of these practices will be examined to understand what acts to suppress a more serious acknowledgment of the contribution made to contemporary research by historical figures and whether, in adopting highly personal archival material, citation goes far enough in crediting the value of these contributions.

Frame as source material / Frame as lens / Frame as mentor / Frame as friend?

Figure 3 Building remnants at Seacliff Asylum, Truby King Reserve, Otago, New Zealand. Photograph by author, April 2010.

Christine Sutherland has written that historians ‘are strangers in the past: we have to find our way about, learn the language, understand the culture, and sometimes come to grips with a very different set of values.’18 My doctoral research attempted to read complex social and personal histories through an examination of buildings in varying states of decay and through a lens of heavily sanitised departmental records. Carolyn Steedman has observed that in ‘actual archives’ there isn’t ‘very much there’. Yet, she argues, we cannot be shocked by the ‘exclusions’ of the archive, for its very existence provides the ‘neatest demonstration of how state power has operated, through ledgers and lists and indictments, and through what is missing from them.’19 While Steedman seeks the ‘psychical phenomenology’ of the archive through the dust and faded ribbons that secure bundled papers and accompany the historian’s visit, Ann Cvetkovich calls for an extended archive, one that values and thus preserves the quotidian objects that accompany histories of trauma. For an archive to be useful, to have ‘affective power’, Cvetkovich suggests an archive must ‘preserve and produce not just knowledge but feeling’.20 The empty sites of New Zealand’s mental hospitals provided a distributed and ephemeral archive (Figure 3). As I wrote my dissertation, weatherboards rotted, and copper spouting disappeared in the night from Seaview Hospital; 650 kilometres north, bulldozers were rolled in at Lake Alice. This temporary, fragmented collection provided the affective richness missing from the drawings, invoices and file notes that accompanied the construction of these buildings. But it was Faces in the Water that connected me to the lived experience of these sites. Frame’s novel eroded the distance between myself and the thousands of lives my research brushed against. It made me aware that each and every number on the page of a government report was a person as real as those who sat beside me.

I searched tirelessly for Frame in the spaces where mould crept up ripped curtains as they danced across broken panes of glass, and in the wind-swept emptiness of endless corridors whose difference lay only in their geographical location. I embarked on a pilgrimage to reunite the architecture fragmented through Frame’s texts with the physical residue of these long-abandoned buildings. ‘Lawn Lodge’ was a pseudonym for a back-ward that Frame likened to ‘a house visited by the plague.’ A back-ward was a term used to describe the wards that accommodated the patients whom hospital staff deemed unlikely to recover. As doctors’ offices were generally located near the front entrance of a mental hospital site, back-wards were those located the farthest away. They were typically the most dilapidated. Frame wrote: ‘we could hear the water splashing in the puddles and gurgling in the spouting, but we could not see for the lower part of the windows was boarded up…’21 I became convinced this ward must have been sited at the Auckland Asylum, and obsessed with locating it amidst what is now a bustling university campus. Just as I diligently combed the razed site of the Seacliff Asylum for any remnant of the concrete steps Frame would traverse during her daily pilgrimage to and from the bathroom during the periods she was kept in seclusion:

I would return shivering from the cold wind that blew along the concrete stairway and through the wire-netting doors of the Brick Building to the doorless bathroom with its exposed, yellow stained old baths, I was ready to be locked in for the day.22

These elements were not relevant to the process of constructing an argument about the design and construction of these hospitals. My thesis required an account of architectural plans, building procurement processes, departmental relationships, and the resulting practices of inhabitation positioned against best-practice approaches to the treatment of mental illness. The relationship of Frame’s experience of a specific site to my research endeavour was peripheral at best. Yet I felt gripped by an inexplicable compulsion to find the fragments that Frame described. To stand on the ground where she had once stood. If I succeeded I shall never be cognisant of the fact (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Landscape remnants at Seacliff Asylum, Truby King Reserve, Otago, New Zealand. Photograph by author, April 2010.

Sutherland argues that, in our process of historical navigation, we must ‘enter as far as possible into the physical world of our subject’; to do that we seek shared experiences in the hopes these will ‘bring us closer to the person whose writings we study, informing and illuminating our research.’23 I was not studying Frame’s writing but it became the lens through which I engaged with these sites. Her narrative undid the process of sanitation the archival records had been subjected to. I was able to grasp the human struggles and tragedies that remained invisible between the neatly typed lines of departmental reports. I could read the empty sprawling spaces that stood before me with an intimate understanding of the routines of daily life formerly contained with their walls (Figure 5). It was Frame who granted this access.

Figure 5 A single bedroom retrofitted by hospital staff for patient seclusion, Lake Alice Hospital, Marton, New Zealand. Photograph by author, June 2010.

My research sought to contribute an architectural perspective to a history that deserved closer examination – even if only as some small tribute to the thousands of stories silenced by confinement. How much of Frame’s material to include became an ongoing negotiation. My earliest chapter drafts were littered with citations from Faces in the Water> and from Frame’s autobiography An Angel at My Table. But in the final days of editing I found myself stripping out the details from these citations, using only what was required. Only later would I appreciate that the logic underpinning this process was not situated within academic practice but in a mounting desire to protect Frame.

Within the final version of my thesis I included only four quotes from Frame: one was on the appearance of Seacliff, one discussed the challenges facing institutional psychiatrists the third was an account of receiving visitors and the fourth detailed bathing procedures.24 The latter was the only citation that dealt with Frame’s intimate experiences of hospital life:

…crowded into the tiny washroom to be dressed. There was little hope of washing, and as one entered the room one was bulldozed … by the smell of stale bodies. We stood there naked, packed tightly like cattle at the sale yards, and awaiting the random distribution of our clothes...25

Even this I became uncomfortable with and cast around for an alternative. A patient identified only as ‘Natasha, Patient at Cherry Farm Hospital, 1975’ similarly recalled: ‘You were herded into the bathroom naked and you had to have baths and showers with everybody. It was like a prison – no privacy… Patients were herded into the room like sheep.’26>I deliberated on this alternative. Typed it out and referenced it before coming back three days later and reinserting Frame’s words. My reticence in using this quote was a consequence of my knowledge of the wider text within which it appeared; specifically, the absence of basic human respect that permeated it.

In my original chapter draft, written early within my candidature, I had also included Frame’s recollections of toilet procedures, of which she gave two separate accounts.27 These citations have become more difficult for me to read as time has passed and the idea of citing them now is intolerable. I have seldom come across a handful of words - less than forty in both cases – that, despite repeated exposure, still cause me to wince at the inhumanity they convey. In the final version of my thesis, I shied away from these quotes, opting for the less disturbing citations provided by Natasha: ‘…you had to go through three locked doors to get to the toilet, and the nurse would come with you.’28 And from the report of the 2005 Confidential Forum for Former In-patients: ‘Many [patients] gave an account of a lack of privacy and routines being carried out in ways that they found degrading and humiliating. … the absence of doors on toilets and having to use toilets in front of staff ...’29 What I knew was that these accounts did not hold a candle to the intensely evocative nature of Frame’s passages or the depth of understanding they were able to provide. Frame could instantly erode the distance between the reader and this history; to make you feel that you could not be more horrified than if you were physically present in one of the situations she described, watching the inevitable consequence of a patient denied access to a toilet. So why could I not bring myself to use them?

Heidi McKee and James Porter have impressed the need to see historic figures within the immediate context of their life but also in the larger context of their community and culture.30 Francesca Moore goes further in pointing out that historical figures continue to play important roles within their communities long after they have died.31 I had not read Frame’s work prior to commencing my doctoral research but this did not prevent my appreciation that she was, and remains, one of New Zealand’s most valued and accomplished literary figures. She has, and will continue, to inspire generations of writers. I was acutely aware, in writing up my thesis, that any damage inflicted on Frame’s reputation may no longer hurt her personally but there remained the possibility of causing distress to her family and the literary community to whom she belongs and still contributes via the works she has left behind. I carefully weighted the benefits of citing each individual passage against the potential damage to Frame’s reputation. Frame offered the most useful and moving account that a historian could wish for in conveying the lived experience of New Zealand’s mental hospitals and she herself had put it in the public realm. These were not archival records of a private nature, yet, I wasn’t convinced that this was justification enough to cite Faces in the Water freely.

Steedman provides a discussion of the relationship between the archive, the novel and the letter that perhaps illuminates the source of this conflict. Where the novel is written for an ‘intended reader’, ‘the Historian who goes to the Archive … will always read that which was never intended for his or her eyes.’32 I cannot know the extent to which Frame’s early drafts of Faces in the Water were intended for an audience since, as a ritual of exorcism, the writing of the work itself seems the necessary act, not the sharing of it afterward. Citing Terry Eagleton, Steedman draws parallels between the archive and letters: ‘The letter is part of the body which is detachable: torn from the very depths of the subject.’33 This distinction begins to unravel my discomfort. The more of Frame’s story I came to understand, the more I read around Faces in the Water, the more I felt I had stumbled into an intensely private world where I should not have been. The final version of my thesis was sanitised of Frame’s most disturbing recollections. In the end, if I am honest, this was not borne of concern for the literary community to whom Frame belonged but a fear of exploiting Frame herself. Somewhere along the way I developed a desire to protect Frame; to mitigate the vulnerability that might arise from the repetition of these details of her life. But what made me think that Frame, a literary giant of world-renown, required my protection? Perhaps this was the wrong question altogether and, potentially, just as patronizing as the discourses that Gordon herself despises. Frame did not require my protection. She deserved my acknowledgement. She is still owed it. But there is nothing straight forward about what form this acknowledgement should take.

Ethical paradoxes and the quantification of research contribution

Acknowledging Frame’s contribution to my research is an act that further consolidates the ties between her personal history and the history of these institutions. It is an ethical paradox with which I have struggled. The position taken within my thesis was one of minimizing Frame’s connection. I empathised with Gordon’s position and felt a responsibility to respect and uphold her approach. However, the value of Faces in the Water as a significant piece of New Zealand’s history cannot be taken lightly. It is a work of paramount importance given the role it plays in standing-in for the stories of thousands of patients who never got to tell their own. Cheryl Glenn and Jessica Enoch have pointed out that when we engage with the written materials left to us, we are participating in an exchange - one that obliges us to listen to our research subjects, even when they speak from the archive.34 But what is the proper form or attribution of such a vital exchange; and how would Frame’s role fit within the accepted academic conventions of research production? This question cannot be answered until the magnitude of Frame’s contribution has been adequately weighted.

Through her texts, Frame contributed as least as much knowledge, practical advice, ethical guidance and emotional support as the two, highly skilled and dedicated supervisors who (living and breathing) guided me though the doctoral process. Frame supported me through the trauma of engaging with a history of devastating futility. If we seek to engage human subjects in the research we conduct, ethical safe guards ensure we account for the risks inherent to this research activity.35 But when we delve into the archive as researchers we seldom give consideration to the preservation of our own wellbeing. How heavily this material will weigh on us; how deeply this knowledge will become embedded in our psyche so that living without it is a memory barely able to be recalled. How does one mitigate such harm; by granting oneself permission to read acts of inhumanity purely as data or to willingly sustain the blows of each subsequent encounter? The determination not to lose my humanity, not to harden to the intolerable traumas faced by patients effected its own trauma. On the days that this material became too dark and overwhelming it was Frame who gave me the strength to persevere.

Susan Sontag, reflecting on her encounter with the photographs of Bergen-Belsen and Dachau, has written: ‘it seems plausible to me to divide my life into two parts, before I saw those photographs … and after.’36 This is how I feel about Faces in the Water. Accepting that my knowledge of Frame’s lived experience is limited at best, renegotiating my existence in the world in light of this knowledge was exhausting. This process of renegotiation parallels with Megan Boler’s ‘pedagogy of discomfort’ which seeks a transformation of a student’s world view, aiming to impart the courage to inhabit a more ambiguous sense of self and to activity resist comfortable binary positions such as right and wrong.37 Frame’s texts taught me this. These texts were not my first encounter with material that disrupted my world view but hers was the work that taught me how to conduct myself with compassion and integrity within a reality far more complex and confounding than I’d formerly appreciated.

At the time I completed my thesis I thought it was for the thousands of patients whose voices had been silenced by New Zealand’s history of institutionalisation for mental illness. It took me three years to realise that I had been writing for Frame. Measuring myself against her standards, striving for an account that was rigorous, respectful and balanced. It couldn’t lay blame unnecessarily. Not on the hospital staff, the architects or administrators who were all, in their own ways, caught within a complex and intractable system. Within these institutions patients were treated in ways that were inexcusable, but Frame remained respectful. She was never unrealistic about what individuals could achieve and acknowledged plainly the realities of these institutions, graciously expressing thanks for small kindnesses. The passage she wrote regarding her perception of institutional psychiatrists provides a humbling lesson that finding oneself in an incomprehensible situation is not an excuse for abandoning one’s integrity or compassion:

the doctor enquiring as if his life depended on it ... ‘Do you trust me, will you trust me’ ... when you knew privately, that he scarcely had time to trust himself in the confusion and tiredness that accompanied the day-and-night attempt to solve the human division sum that had been omitted from his medical training: if one thousand women depended on one-and-a-half doctors how much time must be devoted to each patient in one year …38

In her 1984 autobiography, An Angel at My Table, Frame lamented the degree of detail that she excluded from Faces in the Water (the ‘squalor and inhumanity were almost indescribable’) because she ‘did not want a record by a former patient to appear to be over-dramatic.’39Yet through Frame’s silences and suppressions I learned that sensationalism lends badly to the legibility and credibility of a text. Privileging the exceptional over the quotidian inhumanities of life within these institutions provides a literary sugar rush; it cannot sustain a reader over the duration. We know, from the government inquiries and the hundreds of claims lodged for compensation following deinstitutionalisation, that patients suffered physical and psychological abuse within New Zealand’s mental hospitals.40 Yet the restraint in Frame’s work suggested she understood that there was a very real danger in including too much of this detail. Birmingham has suggested that the skill of the historian is not in ‘see[ing] the dead’ but ‘our potential to help the dead … finish their stories.’41 Frame and I were both engaged in an educational exercise; we were both out to tell stories that needed to be heard and respecting the capacity of the audience to hear those stories is a skill she taught me.

Co-created research, co-authorship and an ethic of reciprocity

Was Frame’s contribution commensurate with contemporary qualifications for co-authorship and what are the ethics that would complicate taking such a position? This, of course, is an extreme question but I would argue that extremes are sometimes necessary to obtain a full understanding of the issues at play. How did Frame’s contribution go unrecognised at the time of submitting my doctoral thesis, by either myself or my supervisors (one of whom had been a close personal friend of Frame)? There would be no such oversight if Frame were living. What are the burdens of academia that act to suppress these conversations? There are broader implications for academic practice that these kinds of conversations cleave open. The degree to which questions of co-authorship simmers as a source of discontent makes clear that these are the conversations we shy away from, trusting instead in habits and conventions we are told are grounded in the fair attribution of research contribution.42 It is only when ethical considerations collide that we find ourselves questioning whether the fall-back options available to us are sufficient. Within our current research context, where transdisciplinary methods and research co-created with participants is on the rise, the attribution of authorship will become more complicated.43

In contemporary academic practice, claims to co-authorship are contingent upon ‘a significant intellectual or scholarly contribution’ that includes one or more of the following:

- conception and design of the research

- acquisition of research data where the acquisition has required significant intellectual judgement or input

- analysis and interpretation of research data

- writing up of the research or redrafting it so as to critically change or substantively advance the interpretation44

Within the disciplines of history and, in this particular case architectural history, much of the research process is conducted in relative isolation. The methods employed for research tend to be long established, requiring no specific design. The acquisition of data is predominantly archival, and generally conducted by the researcher, as is the analysis and write up of this type of research. For most doctoral students of history and its sub-fields, questions of authorship, if they arise at all, tend to occur with reference to co-authorship with supervisors. However, depending on the discipline, institution, nature the research project and the individuals involved, such questions may never arise. This was the case during my candidature.

Frame’s intellectual contribution was significant in shaping the conception and direction of my research. So many of the questions demanded from this architectural residue, and from the physical archive containing the traces of its construction, emanated from Frame’s texts. This calls into question how the ‘acquisition of research data’ is defined when historians draw from archival records that are autoethnographic in nature. That, as Adams, Jones and Ellis point out, foreground the personal experience to critique existing cultural practice.45 As Gambaudo has observed, Faces in the Water was no simple experiential account but one that created ‘a tension between realism and fiction’ because Frame ‘situat[ed] herself at once in and out of the asylum experience, at once the madwomen and the observer of the mad.’46 Employing the novel over the autobiographical format enabled Frame to ‘critique narratives of sanity/insanity’:

to successfully unpack the dynamics of social viability and the social significance, or more accurately insignificance, of marginal experience, something the autobiography does not do.47

To posthumously appoint a co-author, with no prior knowledge of, or agreement to be associated with, a research project would not be a respectful act. I propose, instead, that when we engage voices from the archive an ethic of reciprocity is required. This would honestly state the depth and significance of the knowledge we obtain from others, the way that this shapes our research, informs our practice and, by extension (and where appropriate) our way of existing in the world. An ethic of reciprocity would seek to respect the feelings and experiences of archival figures and to account for their values in so far as these can be understood by the researcher. To return to Glenn and Enoch’s point, that we need to listen to our research subjects,48 listening to Frame required that I hear not only her story but also her desires and values. Her position on the treatment of mental hospital patients, the respect that she showed to others (including hospital staff), and her commitment to storytelling of the highest standard; the care that must be directed to assembling words on a page. I cannot pretend to know whether my work would meet with Frame’s high expectations, but I was sincere in my efforts and perhaps this is the best we can aspire to.

Notwithstanding the veil of fiction under which Faces in the Water was placed into the world, Frame invited readers into her suffering, laying bare uncomfortably intimate experiences. The decision to incorporate such personal work in one’s research should be accompanied by an ethical stance of empathy and respect, not unlike an ethic of ‘friendship’ or ‘care’ that prioritises the wellbeing of those engaged in our research.49 In proposing a definition of care, Nel Noddings has written:

[We should] ideally, be able to present reasons for our action / in action which would persuade a reasonable, disinterested observer that we acted on behalf of the cared-for.50

Wolgemuth and Donohue have similarly suggested that where empathy is the critical stance of the researcher then ‘friendship is the overriding structure for that stance’:

researchers must concern themselves with the whole of participants’ lives, privileging participants’ feelings, experiences, and the needs of data and information gathering.51

In selecting the term ‘privilege’ over ‘balance’, Wolgemuth and Donohue suggest that this involves more than the process of ‘weighting’ benefits against risk – as researchers are so often asked to do within ethics applications. It goes beyond the simple ‘prevention of harm.’ Instead, as Costley and Gibbs point out, this approach asks the researcher to consider how this engagement, or association (in Frame’s case) with research and dissemination might result in positive benefits to a participant’s wellbeing.52

Embracing an ethic of reciprocity challenges the value hierarchy that seeks truth through objectivity. Indeed, it was the expectation of objectivity that precluded a discussion of properly acknowledging Frame’s contribution to my doctoral research. As junior academics, particularly in the field of architectural history, subjectivity is something we are conditioned against. It is to be acknowledged up front, but ever so briefly, and then promptly buried from view for the remainder of the thesis. During my second year of study I read Maria Tumarkin’s dissertation that dealt with public and private trauma in the context of Australia’s Port Arthur; both that which attached to the site following the shootings that took place in 1996 and her own in having to engage with this site for research purposes.53 Her work spoke to me and yet it made me so uncomfortable that I put it down after only three chapters. I was already conditioned to be sceptical of subjectivity, to view this as somehow synonymous with weakness in academic research. Frame’s lessons keep coming. She has helped me here to face my own fear of subjectivity; to have the courage to own it and to recognise out-loud the value of my own personal experience. In the context of my doctoral research Frame deserves to be thanked and properly credited for her essential contributions to the direction and quality of this work, for the tireless support she provided through the trauma of engaging with this difficult history, and for the researcher, teacher and human being I have become because of her influence. In putting this plainly on paper I feel at peace with my dissertation. Gordon’s elusive ‘something’ has been done.

Conclusion

Collaboratively produced research is always a messy business but when our collaborators speak from the archive this complexity is exacerbated by the risk of failing to distinguish between those voices whom we cite, straightforwardly as archival artefacts or passive subjects, and those who more intimately shape the work we produce. For the latter, contemporary practices of attribution and citation are insufficient to account for these contributions. An ethic of reciprocity is required; an approach that challenges current definitions of citation and acknowledgment to recognise when the contribution of historical figures is so critical that they should be regarded not as sources to cite but as co-creators of knowledge. An ethic of reciprocity should be honest and up front in making explicit the significance of these contributions. It demands that research be conducted from a position of empathy and respect, that equal consideration be directed toward the needs of archival figures and the needs of our research.

Acknowledgements

In the process of attending to the reviewers’ insightful recommendations regarding this paper, I stumbled upon the following quote from Frame herself: ‘I am not really a writer, I am just someone who is haunted, and I will write the hauntings down.’54 It has taken three years, and successive drafts of this piece of writing, for guilt to have finally revealed itself as the ‘nagging intangible.’ I owe gratitude to the people who encouraged me through the many drafts: Kim Roberts, Cristina Garduno-Freeman, Hannah Lewi, Jared Green, Amy Heffernan, Katti Williams, Gareth Wilson and Andrew Murray. Finally, to Robin Skinner, thank-you for introducing me (via Faces in the Water) to Janet Frame. How remarkable it would have been to have met her in person.

About the author

Rebecca McLaughlan is a Lecturer in Architectural Design at the Melbourne School of Design, University of Melbourne. Her research takes place at the intersection of architecture, medicine, media and pedagogy. Her favourite novel is Frame’s Towards Another Summer.

Bibliography

Adams, T.E., S. Holman Jones and C. Ellis, Autoethnography: Understanding Qualitative Research, Oxford University Press, New York, 2015.

Boler, M., Feeling Power, Taylor and Francis, London, 1999.

Bradfield, S., ‘Dead Poet Society: In the Memorial Room, by Janet Frame’, The New York Times, 22 November 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/24/books/review/in-the-memorial-room-by-janet-frame.html

Brunton, W., ‘A Choice of Difficulties: National Mental Health Policy in New Zealand, 1840 – 1947’, PhD Diss, University of Otago, 2001.

Cooke, R., ‘A Lost Weekend in the North’, The Guardian, 29 June 2008. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2008/jun/29/fiction.reviews

Costley, C., and P. Gibbs, ‘Researching Others: Care as an Ethic for Practitioner Researchers,’ Studies in Higher Education, vol. 31, no. 1, 2006, pp. 89-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500392375

Cvetkovich, A., ‘In the Archives of Lesbian Feelings: Documentary and Popular Culture.’ Camera Obscura, vol. 17, no. 1, 2002, pp. 110-147.https://muse.jhu.edu/article/7985

Eagleton, T., The Rape of Clarissa. Writing, Sexuality and Class Struggle in Samuel Richardson, Blackwell, Oxford, 1982.

Evans, P., ‘Frame, Janet Paterson - Establishing identity’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, 2010, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/6f1/frame-janet-paterson/page-3.

Frame, J., An Angel at My Table, Vintage, Auckland, 2000 (first published 1984).

Frame, J., Faces in the Water, Random House, Auckland, 2000 (first published 1961).

Gordon, A., Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2008.

Hagestadt, E., ‘Towards Another Summer, By Janet Frame’, Independent, 02 July 2009, http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/reviews/towards-another-summer-by-janet-frame-1728900.html

Harold, D., and Gordon, P. (eds), Janet Frame: In Her Own Words, Penguin Books, Auckland, 2011.

Hunt, A., The Lost Years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre, A. Hunt, Christchurch, 2000.

Gambaudo, S. ‘Melancholia in Janet Frame’s Faces in the Water’, Literature and Medicine vol. 30, no. 1, 2012, pp. 42-60. https://doi.org/10.1353/lm.2012.0008

Goodwin, C. Shadows and Silence, Steel Roberts, Wellington, 2004.

Kennedy, M. The Wrong Side of the Door, George G. Harrap & Co., London, 1963.

King, M. Wrestling with the Angel: A Life of Janet Frame, Viking/Penguin Books, Auckland, 2000.

Louw, D. A., and J. B. Fouche, ‘Authorship Credit in Supervisor-student Collaboration: Assessing the dilemma in Psychology’, South African Journal of Psychology vol. 29, no. 3, 1999, pp. 145-148, https://doi.org/10.1177/008124639902900308

McKee, H., and Porter, J., ‘The Ethics of Archival Research,’ College Composition and Communication, vol. 64, no. 1, 2012, pp. 59-81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23264917

McLaughlan, R.J., ‘One Dose of Architecture, Taken Daily: Building for Mental Health in New Zealand’, PhD dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington, 2014.

Moore, F., ‘Tales from the Archive: Methodological and Ethical Issues in Historical Geography Research’, Area vol. 42, no. 3, 2010, pp. 262-70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2009.00923.x.

New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs, Te Aiotanga: Report of the Confidential Forum for Former In-Patients of Psychiatric Hospitals, Government Printer, Wellington, 2007.

New Zealand Department of Statistics, New Zealand Official Yearbook 1949, Government Printer, Wellington, 1950.

Noddings, N., Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics & Moral Education, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1984.

Plunkett, F., ‘Angela will be livid: In the Memorial Room by Janet Frame’, Sydney Review of Books, 07 June 2013, https://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/angela-will-be-livid/

Priego, E. ‘Long author-lists on research papers are threatening the academic work system’, Independent, 27 May 2015, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/long-author-lists-on-research-papers-are-threatening-the-academic-work-system-10279748.html

Ramsay, A., Sharer, W., L’Eplattenier, B., and Mastrangelo, L. (eds), Working in the Archives: Practical Research Methods for Rhetoric and Composition, Southern Illinois University, Press, Carbondale, 2009.

Roberts, K., ‘The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Cenotaph and the Shadow Side of Spatial Research’ Fabrications, vol. 29, no. 1, 2019 (in press).

Robins, L.M., and Kanowski, P.J., ‘PhD by Publication: A Student’s Perspective’, Journal of Research Practice vol. 4, no. 2, 2008, http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/136/154

Savransky, M. and Rosengarten, M., ‘What is Nature Capable of? Evidence, Ontology and Speculative Medical Humanities’, Medical Humanities, vol. 42 no. 3, 2016, pp. 166–72. http://mh.bmj.com/content/42/3/166

Sontag, S., On Photography, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1977.

Steedman, C., ‘The Space of Memory: In an Archive’, History of the Human Sciences, vol. 11, no. 4, 1998, pp. 65-83. https://doi.org/10.1177/095269519801100405

Suibhne, S.M. ‘Erving Goffman’s Asylums Fifty Years On,’ British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 198, no. 1, 2011. pp. 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.077172

Tarnow, E., ‘Co-authorship in Physics,’ Science and Engineering Ethics, vol. 8, no. 2, 2002, pp. 175-190, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-002-0017-2

The National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council and the Australian Vice-Chancellors’ Committee, National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2014.

The New Yorker, ‘This Week in Fiction: Pamela Gordon on Janet Frame’, New Yorker, 29 March 2010, http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2010/03/this-week-in-fiction-pamela-gordon-on-janet-frame.html#ixzz0lUcZdRGfA

The Telegraph, ‘Jane Frame Obituary,’ The Telegraph, 30 January 2004,

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1452977/Janet-Frame.html

The University of Melbourne, Authorship Policy (MPF1181), http://policy.unimelb.edu.au/MPF1181

Williams, W.H. Out of Mind out of Sight: The Story of Porirua Hospital. Porirua Hospital, Wellington, 1987. Wolgemuth, J.R. and Donohue, R., ‘Toward an Inquiry of Discomfort: Guiding Transformation in “Emancipatory” Narrative Research’, Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 12, no. 5, 2006, pp. 1022-1039, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800406288629 Youtie, J. and Bozeman, B., ‘Social Dynamics of Research Collaboration: Norms, Practices, and Ethical Issues in Determining Co-authorship Rights’, Scientometrics vol. 101, no. 2, 2014, pp. 953-962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1391-7 1. Kim Roberts, ‘The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Cenotaph and the Shadow Side of Spatial Research’ Fabrications, vol. 29, no. 1, 2019 (in press). This work was originally presented at the Colloquium on Ficto-criticism, University of Queensland, 4-5 August 2016. 2. Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2008, p. xvi-xvii. 3. ‘Jane Frame Obituary,’ The Telegraph, 30 January 2004. 4. Sylvie Gambaudo, ‘Melancholia in Janet Frame’s Faces in the Water’, Literature and Medicine vol. 30, no. 1, 2012, pp. 42; Patrick Evans, ‘Frame, Janet Paterson - Establishing identity’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, 2010. 6. Pamela Gordon, ‘Truth is Indeed Stranger than Fiction: A Biographical Sketch’, in Faces in the Water, Random House, Auckland, 2000 (first published 1961), p. 18. 7. Rachel Cooke, ‘A Lost Weekend in the North,’ The Guardian, 29 June 2008; Emma Hagestadt, ‘Towards Another Summer, By Janet Frame’, Independent, 02 July 2009; Scott Bradfield, ‘Dead Poet Society: In the Memorial Room, by Janet Frame’, The New York Times, 22 November 2013; Felicity Plunkett, ‘Angela will be livid: In the Memorial Room by Janet Frame’, Sydney Review of Books, 07 June 2013. 8. Wikipedia Contributors, ‘Janet Frame’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Janet_Frame&oldid=758689382. 9. The New Yorker, ‘This Week in Fiction: Pamela Gordon on Janet Frame’, New Yorker, 29 March 2010. 10. Pamela Gordon, ‘Preface: Frame Unframed’, in Denis Harold and Pamela Gordon, (eds), Janet Frame: In Her Own Words, Penguin Books, Auckland, 2011, p. 5. 11. New Zealand Department of Statistics, New Zealand Official Yearbook 1949, Government Printer, Wellington, 1950. 12. Janet Frame, An Angel at My Table, Vintage, Auckland, 2000 (first published 1984), p. 99. 13. Seamus Mac Suibhne, ‘Erving Goffman’s Asylums Fifty Years On’, British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 198, no. 1, 2011, pp. 1-2. 14. Anne Hunt, The Lost Years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre, A. Hunt, Christchurch, 2000; Wendy Hunter Williams, Out of Mind out of Sight: The Story of Porirua Hospital. Porirua Hospital, Wellington, 1987; Marion Kennedy, The Wrong Side of the Door, George G. Harrap & Co., London, 1963. 15. New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs, Te Aiotanga: Report of the Confidential Forum for Former In-Patients of Psychiatric Hospitals, Government Printer, Wellington, 2007. Note: that while the earliest experiences recorded within this report dated from the 1940s, corresponding with Frame’s experience, most participants were resident during the period spanning 1970 to the closure of these institutions in the late 1990s. 16. Warwick Brunton, ‘A Choice of Difficulties: National Mental Health Policy in New Zealand, 1840 – 1947’, PhD Diss, University of Otago, 2001, p. 360. 17. Martin Savransky and Marsha Rosengarten, ‘What is Nature Capable of? Evidence, Ontology and Speculative Medical Humanities,’ Medical Humanities, vol. 42 no. 3, 2016, pp. 166. 18. Christine Mason Sutherland, ‘Getting to Know Them: Concerning Research into Four Early Women Writers’, in Alexis Ramsay, Wendy Sharer, Barbara L’Eplattenier, and Lisa Mastrangelo (eds), Working in the Archives: Practical Research Methods for Rhetoric and Composition, Southern Illinois University, Press, Carbondale, 2009, pp. 28. 19. Carolyn Steedman, ‘The Space of Memory: In an Archive’, History of the Human Sciences, vol. 11, no. 4, 1998, pp. 67. 20. Ann Cvetkovich, ‘In the Archives of Lesbian Feelings: Documentary and Popular Culture’, Camera Obscura, vol. 17, no. 1, 2002, pp.110. 21. Frame, Faces in the Water, pp. 104. 22. Frame, Faces in the Water, pp. 100. 24. Rebecca McLaughlan, ‘One Dose of Architecture, Taken Daily: Building for Mental Health in New Zealand’, PhD dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington, 2014. 25. Frame, Faces in the Water, pp. 104. 26. Claire Goodwin, Shadows and Silence, Steel Roberts, Wellington, 2004, pp. 16. 27. Frame, Faces in the Water, pp. 104, 155. 30. Heidi McKee and James Porter, ‘The Ethics of Archival Rese––arch,’ College Composition and Communication, vol. 64, no. 1, 2012, pp. 78. 31. Francesca Moore, ‘Tales from the Archive: Methodological and Ethical Issues in Historical Geography Research’, Area vol. 42, no. 3, 2010, pp. 268. 33. Steedman, pp. 79; Terry Eagleton, The Rape of Clarissa. Writing, Sexuality and Class Struggle in Samuel Richardson, Blackwell, Oxford, 1982, pp. 54. 34. Cheryl Glenn and Jessica Enoch, ‘Invigorating Historiographic Practices in Rhetoric and Composition Studies,’ in Ramsay, A., Sharer, W., L’Eplattenier, B., and Mastrangelo, L. (eds), Working in the Archives, pp. 11-27. 35. The National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council and the Australian Vice-Chancellors’ Committee, National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2014. 36. Susan Sontag, On Photography, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1977, pp. 20. 37. Megan Boler, Feeling Power, Taylor and Francis, London, 1999, pp. 175-202. 38. Frame, Faces in the Water, pp. 225. 39. Frame, An Angel at My Table, pp. 99. 40. Around four hundred and fifty former patients received ex-gratia payments from the New Zealand Government, two cases of compensation were settled in court. For an official report refer: http://www.justice.govt.nz/policy/constitutional-law-and-human-rights/human-rights/international-human-rights-instruments/international-human-rights-instruments-1/convention-against-torture/united-nations-convention-against-torture-and-other-cruel-inhuman-or-degrding-treatment-or-punishment-new-zealand-periodic-report-6/article-14/27-complaints-claims-and-compensation. 41. Elizabeth Birmingham, ‘ “I see Dead People”: Archive, Crypt, and an Argument for the Researcher’s Sixth Sense,’ in Ramsay, A., Sharer, W., L’Eplattenier, B., and Mastrangelo, L. (eds), Working in the Archives, pp. 144. 42. Eugen Tarnow, ‘Co-authorship in Physics,’ Science and Engineering Ethics vol. 8, no. 2, 2002, pp. 175-190; Louw, D. A., and J. B. Fouche, ‘Authorship Credit in Supervisor-student Collaboration: Assessing the dilemma in Psychology’, South African Journal of Psychology vol. 29, no. 3, 1999, pp. 145-148; Jan Youtie and Barry Bozeman, ‘Social Dynamics of Research Collaboration: Norms, Practices, and Ethical Issues in Determining Co-authorship Rights’, Scientometrics vol. 101, no. 2, 2014, pp. 953-962; Lisa M. Robins and Peter J. Kanowski, ‘PhD by Publication: A Student’s Perspective’, Journal of Research Practice vol. 4, no. 2, 2008. 43. The current debate regarding ‘hyperauthorship’ provides an interesting example of this, refer: Ernesto Priego, ‘Long author-lists on research papers are threatening the academic work system’, Independent, 27 May 2015. 44. The University of Melbourne, Authorship Policy (MPF1181). 45. Tony E. Adams, Stacy Holman Jones and Carolyn Ellis, Autoethnography: Understanding Qualitative Research, Oxford University Press, New York, 2015, p. 26. 48. Glenn and Enoch, pp. 11-27. 49. Jennifer R. Wolgemuth, and Richard Donohue, ‘Toward an Inquiry of Discomfort: Guiding Transformation in “Emancipatory” Narrative Research’, Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 12, no. 5, 2006, pp. 1033; Carol Costley and Paul Gibbs, ‘Researching Others: Care as an Ethic for Practitioner Researchers’, Studies in Higher Education, vol. 31, no. 1, 2006, pp.93. 50. Nel Noddings, Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics & Moral Education, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1984. 51. Wolgemuth and Donohue, pp. 1033. 52. Costley and Gibbs, pp. 93. 53. Maria Tumarkin, ‘Secret Life of Wounded Spaces: Traumascapes in Contemporary Australia’, PhD Diss. The University of Melbourne, 2002.Notes